- Department for Political Science, Friedrich Schiller University Jena, Jena, Germany

The article investigates how the opportunity structure and contextual factors influence the selectorates’ strategies in the process of candidate selection. The article argues that these strategies are an under-researched but important explanatory and dynamic link between the parties’ goals and context factors of candidate selection on the one side and the adopted selection criteria and the outcome of candidate selection on the other side. Based on a mixed-methods design, the study scrutinizes the selectorates’ strategies at district selections in Germany’s mixed-member electoral system. The analysis reveals that the local selectorates adopt the traditional inward oriented selection criteria to find the best candidate for the local party branch if the district seat is safe for the party. If, however, the seat is not safe, the selectorates prioritize the electoral goal over the local party organizational goal and strategically adapt the selection criteria to the opportunity structure. By considering both local inter-party competition and regional intra-party competition, they either take up a local voters’ perspective or anticipate the selection criteria of the state party lists in order to increase the chances for a seat in parliament. Thus, due to the mixed-member electoral system, the prevalence of dual candidacies, and decentralized candidate selection methods, intra-party selection in German districts is a two-level game.

1 Introduction

Candidate selection as the “secret garden of politics” (Gallagher and Marsh, 1988) is a topic that continues to inspire scholars and the scientific debate (e.g., Norris and Lovenduski, 1995; Hazan and Rahat, 2010). By referring to the supply and demand model of recruitment (Norris Lovenduski, 1995; Norris, 1997), the literature on demand-side factors has focused on the gatekeepers and their selection criteria (Norris, 1997). In particular, there has been broad research on the democratization of parties’ internal structures and their impact on the processes and outcomes of candidate selection. Another crucial aspect in this debate is the question how the political parties react and change their candidate selection in the light of the social and political challenges, i.e., the personalization of politics, the increase of populist and other types of challenger parties, disenchantment, and increased volatility (Kriesi et al., 2008; Coller et al., 2018; Cross et al., 2018; Dalton, 2018; Pedersen and Rahat, 2021).

However, despite the intensive research on the demand-side factors of recruitment, only little attention has been paid to the selectorates’ strategies in the process of candidate selection (Adams and Merrill, 2008; Crisp et al., 2013). This is surprising since the parties’ strategies are highly relevant as an important explanatory and dynamic link between the parties’ goals and context factors of candidate selection on the one side and the adopted selection criteria and the outcome of candidate selection on the other side. In a nutshell, it is argued that the parties’ selectorates are regularly forced to set priorities between the—often—competing goals of party loyalty and electability in the process of candidate selection (Ascencio and Kerevel, 2020). This is likely to result in a strategy which is adopted by the selectorate in order to achieve the prioritized goal(s). This suggests that the selectorate nominates under certain conditions candidates for strategic considerations, e.g., electoral goals. By that, the strategies are likely to influence the hierarchy of the selection criteria, the outcome of the candidate selection process, the campaign behavior and the behavior of MPs (e.g., Preece, 2014; Papp and Zorigt, 2016; Ascencio and Kerevel, 2020; Zittel and Nyhuis, 2021).

It is assumed that the specific strategy the selectorate applies is centrally influenced by the opportunity structure and the context factors of the specific selection process (Schlesinger, 1966; Norris and Lovenduski, 1993). However, there is a lack of studies scrutinizing how these factors shape the strategies of the selectorates and whether the political parties react to the social and political challenges by adapting their strategies. Therefore, this article raises the central research question: How do the opportunity structure and contextual factors influence the selectorates’ strategies in the process of candidate selection? It is expected that the electoral system, the party system, and the competitive context as well as the candidate selection methods are central contextual factors.

To answer the research question, the study focuses on the district selections in Germany’s mixed-member electoral system. Germany provides an interesting case since intra-party candidate selection is highly decentralized and still highly relevant for the representation in parliament due to the electoral system and the high number of safe district seats and safe spots on the party lists (Manow, 2015; Davidson-Schmich, 2016). It also allows to scrutinize the impact of the mixed member electoral system and the prevalence of dual candidacies on the parties’ strategies in district selections (Schüttemeyer and Sturm, 2005; Reiser, 2014a; Ceyhan, 2018). The analysis builds on a quantitative analysis of all district nominations for the Federal Elections 2009 and includes next to a content analysis of documents and participant observation in particular qualitative face-to-face interviews with 148 local party officials and (successful and unsuccessful) intra-party candidates, and 35 journalists to reconstruct the selection processes in 32 districts. This research design allows to analyze the informal strategies and thus to go beyond the secret garden of politics.

2 Theoretical Framework: Party Strategies in Intra-Party Candidate Selection

There has been a growing interest in the processes and outcome of intra-party candidate selection in the last years. One important framework to analyze candidate selection is the supply and demand model of recruitment (Norris and Lovenduski, 1995; Weßels, 1997). According to this model, the outcome of the intra-party selection process can be understood as an interactive process between the supply of aspirants aiming to run for office, and the demands of the gatekeepers who select the candidates. Norris and Lovenduski (1995) stress that the interactions and dynamics between the supply and the demand side are embedded and influenced by the wider framework of the structure of opportunities. This includes the political system with its legal regulations, the party system, the electoral system, as well as the broader recruitment process with its party rules and procedures.

With regard to the demand side, research has focused on the one hand on the composition of the selectorates, i.e., the formal and informal committees which select the candidates. Based on the criteria of inclusiveness and decentralization, studies have revealed a process of democratization of the selectorates which also influences the outcome of candidate selection processes (Adams and Merrill, 2008; Hazan and Rahat, 2010). On the other hand, there has been research on the selection criteria of these party selectorates. Selection criteria are those characteristics of prospective candidates which are seen as appropriate by the party selectorates in the process of candidate selection (Hazan and Rahat 2010). While these criteria vary, for instance, between political systems, electoral systems (Norris, 1997), parties (e.g., Reiser, 2014b; Cordes and Hellmann, 2020), and selection methods (e.g., Weßels, 1997; Schindler, 2020), research has also revealed certain commonalities. Several studies show that the most important criteria in electoral districts are incumbency, long-term party service, experience in local offices, qualifications, and localness of the aspirants (e.g., Herzog, 1975; Klingemann and Wessels, 2001; Siavelis, 2002; Crisp et al., 2013; Ohmura et al., 2018; Berz and Jankowski, 2022).

However, so far, the literature has failed to address the question why particular selection criteria are applied by the selectorates in the first place. It is argued in this article that there are underlying strategic considerations of the parties’ selectorates which lead to a different prioritization and hierarchy of the selection criteria and thus to a different outcome of the candidate selection process. And indeed, it has been argued that there are two main goals which are relevant for the strategic considerations in the process of candidate selection: party-related organizational goals and electoral goals (Best and Cotta, 2000; Adams and Merrill, 2008; Dodeigne and Meulewaeter, 2014; Ascencio and Kerevel, 2020): From the perspective of the party organization, a candidate should be loyal to the party and should fit in with the ideological and policy-related objectives of the party (Andeweg and Thomassen, 2011). Hence, with regard to the organizational goal, party membership, a long-term service in local and party offices, and intra-party visibility are likely to be the most important selection criteria because they serve as cues for party loyalty. With regard to electoral goals, a candidate should be able to appeal to and mobilize voters and win office (Downs, 1957). From this outward perspective, voter oriented criteria such as personal vote-earning attributes (PVEA) are thus assumed to be crucial. These are characteristics of candidates which increase their reputation in the local context and may help them to develop political support beyond the party loyal voters, such as electoral appeal, public awareness, and name recognition (Carey and Shugart, 1995; Shugart et al., 2005; Tavits, 2009; Crisp et al., 2013)1.

While an ideal candidate would combine a high level of electability with party loyalty, it can be assumed that in most cases there is a “loyalty-electability trade-off” (Ascencio and Kerevel, 2020). As a consequence, the selectorate is forced to balance these competing goals and has to set priorities (Best and Cotta, 2000). The main argument is that this results in a strategy which is adopted by the selectorate in order to achieve the prioritized goal(s). This suggests that the selectorate nominates under certain conditions candidates for strategic considerations, e.g., electoral goals, and therefore adjust the selection criteria. The specific strategy the selectorate applies, I argue, is—at least partially—shaped by the conditions and context factors of the specific selection process. This refers in particular to the opportunity structure—i.e., the electoral and the party system—and the selection process (Schlesinger, 1966; Norris and Lovenduski, 1993). As such, the strategies of the parties’ selectorate are an important explanatory link between the context factors of candidate selection on the one side and the adopted selection criteria and the outcome of candidate selection on the other side.

The parties’ strategies are thus highly relevant since they are likely to result in a varying prioritization and hierarchy of the selection criteria, in different outcomes of the candidate selection processes, and subsequently in a different composition of the parliament. There is evidence that they also influence the behavior of MPs (e.g., Preece, 2014; Ascencio and Kerevel, 2020). But despite this high relevance, there is only little research on the strategies of the selectorates during the process of candidate selection. In particular, there is a lack of studies scrutinizing how the conditions and context factors shape the strategies of the selectorates. Therefore, this article wants to explore the impact of the contextual factors on the strategies of the parties’ selectorates by focusing on district selections in mixed-member electoral systems.

2.1 Mixed Member Electoral Systems

Mixed member electoral systems are an interesting case to study the strategies of the selectorates. In recent years, numerous studies have analysed the impact of the electoral system on intra-party selection processes (e.g., Hazan and Rahat, 2010; Norris and Lovenduski, 1995). This research has shown that the selection criteria and outcomes of selection processes differ between majoritarian and proportional electoral systems (e.g., Hazan and Voerman, 2006; Ceyhan 2018) which suggests that—despite a lack of empirical studies—also the strategies of selectorates vary. In mixed member electoral systems, there are two distinct routes to parliament: One part of the MPs is elected in single-member constituencies, and the other part of the MPs is elected from party lists (Shugart and Wattenberg, 2004). According to the “best of two world”-literature, one would expect that the strategies of the selectorates in the electoral districts would resemble those in “pure” majoritarian systems (e.g., Stratmann and Baur, 2002; Zittel and Gschwend, 2008). In contrast, others have argued that the two tiers are de facto not independent of one another since there are “contaminations” (Ferrara et al., 2005; Crisp, 2007). One source of contamination between the two groups of MPs is seen in the selection criteria for the intra-party candidate selection processes, i.e., constituency service duties for re-selection on the PR list-tier (Reiser, 2013; Hennl, 2014; Ceyhan, 2018). Double candidacies are seen as a second source of contamination. Typically, mixed member systems allow candidates to run in both tiers simultaneously (Borchert and Reiser, 2010; Papp, 2019; Ceyhan, 2018). Due to these interaction effects between the two tiers, one might expect that the strategies of the selectorate in the electoral districts might also be influenced by candidate selection for the list tier.

2.2 Party System and Competitive Context

Second, it can be assumed that the strategies are influenced by the party system and the competitive context. Carty (1980): 564 stresses that intra- and inter-party competition “are as inseparable as they are interactive” (see also Key, 1956; Selb and Lutz, 2014). From the perspective of the specific party, three different contexts of inter-party competition can be distinguished in electoral districts: safe, contested, and hopeless districts. In a safe district, based on previous electoral results and polls, the party can expect to re-win the district. In a contested electoral district, the candidate of the party has a realistic chance to win the district, but there is at least one other party who also has realistic chances to win the seat. In contrast, in hopeless districts, there is no realistic chance for a candidate of the specific party to win the district (Manow, 2015; Thomas and Bodet, 2012). It is assumed that these conditions shape the strategic considerations of the selectorate (Gallagher, 1998). For instance, Best and Cotta (2000: 12) argue that in a situation when a party has “a significant part of the electoral support market, campaign qualities of contenders will be of less importance than their expected loyalty or their ideological fit.” Thus, the selectors are expected to adopt an inward-looking strategy. In contrast, in competitive districts, it seems plausible that the selectorates strategically nominate candidates who are highly electable in order to increase the chances to win the district (Ascencio and Kerevel, 2020).

2.3 Intra-Party Selection Process

How candidate selection methods influence the outcome of candidate selection has been widely discussed in the academic debate in recent years (e.g., Bille, 2001; Cross, 2008; Hazan and Rahat, 2010; Coller et al., 2018). Analytically, most scholars refer based on the concept of Hazan and Rahat (2010) to decentralization and inclusiveness of the selectorate as the two central dimensions of candidate selection.

Decentralization refers to the geographical level at which candidate selection takes place, hence, at the local, regional, or national level. Hazan and Rahat (2010: 58) have argued that centralized nomination committees tend to select candidates who follow the party line, while candidates which are selected in a constituency “will respond to the demands of their local base.” This points to different strategies and reference points of the party selectorates at different geographical levels (see also Siavelis and Morgenstern, 2008; Shomer, 2017; Berz and Jankowski, 2022). And indeed, in line with the literature on multi-level parties (e.g., Detterbeck, 2012), it seems to be an oversimplification to assume that the strategies of local party selectorates and national party selectorates are congruent. For instance, a local selectorate striving for the organizational goal of party loyalty is likely to relate this in particular to the local party branch, while a centralized selectorate might understand it rather as loyalty to the national party leader or the faction in the parliament. Therefore, it is plausible that dependent on the degree of centralization, there are different, territorial-related strategies, and there might be a trade-off between local, regional, and national interests.

Inclusiveness refers to the composition of the selectorate. According to Hazan and Rahat (2010), the level of inclusiveness ranges from all voters as the most inclusive selectorate to the party leader as the most exclusive selectorate. Research has shown mixed results regarding the impact of the level of inclusiveness on the degree of representation (Ashe et al., 2010; Spies and Kaiser, 2014) and on the behavior of the MPs (Cordero and Coller, 2015). This link suggests that the inclusiveness of the selectorate has an impact on the strategies adopted by this body. It seems plausible that more inclusive selectorates—such as member committees—tend to be more oriented towards intra-party related goals such as loyalty and are less likely to adjust the selection criteria strategically, for instance, to electoral consideration. In contrast, it can be assumed that more exclusive selectorates—such as delegates and party elites—tend to be more aware of the loyalty-electability trade-off and more open to strategic considerations.

3 The Case of Germany

Germany provides an interesting case to study the strategies of the party selectorates in electoral districts in a mixed-member electoral system: In Germany’s mixed-member electoral system (Klingemann and Wessels 2001; Manow 2015), half of the 598 members of parliament (MPs) are elected in single-member constituencies according to the first-past-post-system, while the other half are elected on closed state party lists (proportional representation, or PR, system).

However, the formally equal access to the parliament differs profoundly by party and region which is likely to influence selectorates’ strategies: The smaller parties traditionally only win seats via the state party lists. Exceptions are the Left Party in East German districts and the Green party in one electoral district in Berlin. However, at the Federal Elections 2017, the new right-wing party AfD was able to win three districts seats, and at the Federal Elections 2021, the AfD and the Green party have been able to win 16 districts each. With regard to the large parties—Social Democracts (SPD), Christian Democrats (CDU), and its Bavarian sister party Christian Social Union (CSU)—the strength of the parties in each state (Bräuninger et al., 2020) influences whether the party wins predominantly constituency seats or list seats. In some states, parties win predominantly constituency seats (for instance, CSU in Bavaria) and only few or no mandates on the list; in other states, it is vice versa. Although the share of safe districts has decreased in the last decades due to the changes in the party system2, dealignment, and increased volatility (Kriesi et al., 2008; Dalton, 2018), the majority of the districts (56.2%) has been categorized as safe for one party in the last elections (Davidson-Schmich 2016: 141; see also; Manow, 2015; Weßels, 2016).

Hence, formally, there are two independent forms of candidacy. Candidates may, however, run under both formulas simultaneously. Since the early years of the Federal Republic, the two formally independent forms of candidacy became more and more interlinked (Kaack, 1969; Borchert and Reiser, 2010; Manow, 2015). Today, double candidacies are prevalent: After the Federal Elections of 2009, 86% of the MPs had been double-candidates, meaning that they ran both in the district and on the state party list. Only 2% of the MPs had been pure list candidates (Borchert and Reiser, 2010; see also Baumann et al., 2017). There are, of course, also pure party list candidates and pure district candidates—but they are predominantly running on unwinnable spots on the party lists and in unwinnable districts. In addition, there are clear indications for interaction effects between the two tiers since a district candidacy is de facto a precondition for a good or promising spot on the state party list (Schüttemeyer and Sturm, 2005; Reiser, 2014a; Ceyhan, 2018; Zeuner, 1970). This points to strong contaminations between the two formally independent tiers which is likely to influence the selectorates’ strategies in the electoral districts.

Candidate selection in Germany is characterized by strong legal regulation and by a high degree of decentralization: While list candidates are selected by party conventions of the state party branch, candidates for the single-member constituencies are nominated by party conventions at the district level. While the Federal or state party executive have formally the right to veto the nominated candidate, this is hardly ever used (Detterbeck, 2016; Reiser, 2018). The inclusiveness of the selectorate continues to be on a rather low level: Currently, about 70% of the district candidates are nominated by delegate conventions and only 30% by member selectorates (see Supplementary Table S2; see also Schindler, 2020). It is important to note that electoral districts and party branches are often not congruent: In only 32% of the cases, only one county party branch is responsible for the nomination. In the clear majority of the electoral districts, members or delegates of two to four county party branches constitute the selectorate and jointly nominate the candidate (see Supplementary Table S3) which might influence the strategic considerations.

4 Research Strategy and Empirical Basis

Candidate selection has been characterized as the “secret garden” (Gallagher and Marsh 1988) of politics. This is in particular true for the informal strategies of the party selectorates. Therefore, the study relies on a mixed-methods design. The core of the study is the reconstruction of the selection processes in 32 electoral districts for the Federal Elections 2009.

The analysis focuses on the four parties Social Democrats (SPD), Christian Democrats (CDU), and their Bavarian sister party Christian Socialist Union (CSU) and the Left party in East Germany and Berlin since these parties had the chance to win an electoral district3. The population for the sample are thus 661 district selection processes (see Supplementary Table S1). For each party, there has been a stratified random sample (Behnke et al., 2006) based on two criteria: 1) Candidate selection with or without incumbent; 2) Degree of intra-party competition at the nomination conference. A disproportionate stratified sampling was used in order to allow to identify specific strategic considerations for different types of intra-party selection processes. Overall, the sample allows to explore differences in the degree of intra-party competition, party differences, and specifics of intra-party competition with and without incumbencies. With the exception of one type (incumbent, no competition), for each type, a random sample has been conducted. A descriptive analysis shows that the sample includes seven intra-party competitions with incumbents (21.9%) and 25 intra-party competition without incumbent (78.1%). There is also variance regarding the chances to win a mandate in the district or via the party list (see Supplementary Table S3), the number of county party branches who are jointly responsible to nominate the district candidate (Supplementary Table S4), the candidate selection method (Supplementary Table S5), as well as regional variance (see for details Reiser, 2014b).

The reconstruction of the 32 nomination processes is based on semi-structured face-to-face interviews with 148 local party officials and (successful and unsuccessful) intra-party candidates. Additionally, interviews with 35 local journalists in the 32 districts have been conducted in order to be able to include an outside perspective. In addition, qualitative content analyses of the newspaper articles related to the nomination processes and the press releases of the local parties and candidates have been conducted. Furthermore, in 30 of the 32 intra-party competition, the local party leaders (i.e., protocols of the committee meetings of the local party branches and the nomination conferences) and applicants (e.g., CVs, official application, manuscript for speech at the nomination conference, advertising material for intra-party electoral campaign) provided further documents. Based on a qualitative content analysis of these different sources and of a reconstruction of the different selection processes, the strategies of the selectorates have been inductively developed. This multi-method research design allows an analysis of the strategies of the selectorates in the process of candidate selection.

The analysis of the strategies of the selectorate in this article focuses exclusively on vacant candidacies of the party in the specific district. The main reason is that there is hardly intra-party competition if the incumbent runs again for candidacy (see Table 1) and that in these cases incumbency is the most important selection criterion (see also Reiser, 2014b; Weßels, 2016; Baumann et al., 2017).

5 Empirical Findings: Strategies of the Party Selectorate in Vacant Districts

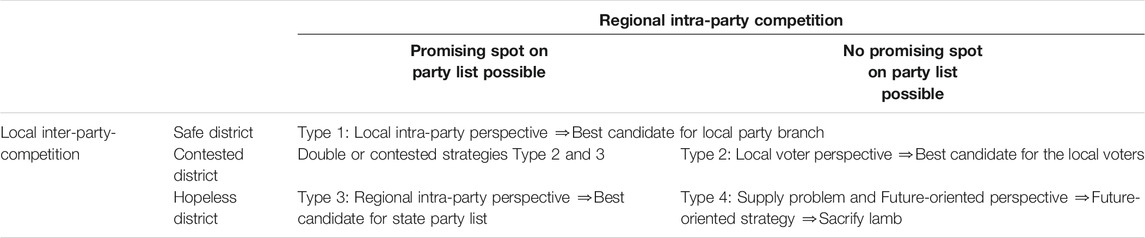

The analysis reveals that the parties’ selectorates adopt four main strategies in vacant districts. These strategies vary systematically dependent on the specific opportunity structure:

Strategy 1 is adopted in safe districts for the specific party. In these districts, the local party leaders and the selectorate expect the party to win the district mandate:

“Since 1949, the CDU has always won this district seat. If you become candidate, you made it de facto to the Bundestag. A disappointing electoral result for the party here is 48%—and that is of course enough to win the district seat” (I45).

In view of this situation, the interviewed party actors regularly referred to the saying that the party could “nominate a broomstick” and would still win the district seat. This statement clearly reflects that the profile and electability of a candidate is seen as “completely irrelevant” (I56; see also I2, 13, 29, 57) for the candidate selection process:

“There is always an opinion within the party and one outside the party. You can be everybody’s darling in the party, and at the same time the voters might be not appealed by this candidate. But it is irrelevant here. We don’t pay attention to this” (I113).

Thus, the local party leaders look for “a candidate who is highly accepted within the party” and “who suits the selectorate in this district.” Thus, they take up a local intra-party perspective which distinguishes strategy 1 from the other three strategies. This strategy is also reflected in the selection criteria. The most important selection criterion is the affiliation of the candidate to the specific county party branch. As explained (see Section 3 and Supplementary Table S4), in two thirds of the electoral districts, two to four county party branches are jointly deciding upon the district candidate. Since all party branches strive to nominate a candidate of their own branch, this criterion tops all other criteria as the following quote shows exemplarily:

“There has been a female aspirant who unluckily lives in the city [thus, in the other county party branch, M.R.]. She has exactly the profile we have been looking for: a young woman, long term active in the party and successful in her job. In addition, she delivered an excellent speech at the nomination conference. However, our rural party branch has the majority of the delegates and that’s why we voted for our aspirant—despite the fact that our aspirant was significantly weaker in all aspects.”

Intra-party awareness, intra-party networks, and the current engagement in the party and local offices are seen as relevant since they reflect intra-party engagement, knowledge of local issues, and party loyalty. As regards the social profile age (not too young and not too old; 40–45 years), gender (with clear party differences) and occupation (someone who has proved him and herself in their job but have enough time for the electoral campaign and the political career) have been regarded as important. In contrast, policy positions, competencies, an appeal to the voters, and public awareness have not been perceived as important. Thus, the local party selectorate clearly prioritizes territorial local representation over all other types of representation and looks for a candidate who is loyal to the local party.

Strategy 2 is adopted in districts which are contested between at least two parties. This means that there is a chance for the specific party to win the district seat but there is at least one other party who also has the chance:

“It has been a close race between the three parties [CDU, SPD and Left] (…). In Brandenburg, the state party list is hardly relevant for us [SPD]. Therefore, we had to win the race in the district” (I79).

Under this condition, the strategy of the selectorate shifts from the intra-party orientation and party loyalty to the voters’ perspective and the electability of the candidate. Therefore, one central reference point for the candidate selection is the profile of the main competitor in the district race:

“Hence, our guiding question during the whole selection process was: What is going on in the other party? Who is going to be their candidate? And what could be the best counter profile to attract votes?” (I52).

For instance, in a district with an older male incumbent of the SPD, the CDU nominated a young female candidate with only little political experience to have a “candidate who has not this typical profile of a politician and who is not using their typical clichés” (I31). This example also reveals that central selection criteria such as experience in local and party offices are secondary under this conditions: The young female candidate won against three intra-party aspirants who all had a long-term party engagement, a better intra-party awareness, and a better intra-party network but had a profile too similar to the main competitor.

In addition, vote earning attributes are stressed as decisive for the intra-party competition, such as popularity, visibility, sympathy, and success in earlier electoral campaigns, e.g., a high number of preference votes in previous local elections. In addition, moderate policy positions are seen as central in order to attract as many voters as possible:

“You must not nominate a person who is polarizing. In order to win the district, we need to win votes in the red-green city but also in the black urban hinterland.”

Thus, candidate qualities that extend beyond party loyalty and can attract new voters are seen as relevant. Other criteria such as the affiliation to the county party branch, intra-party loyalty, and engagement in local and party offices are still perceived as highly relevant by the selectorate. But because of the competitive context in the district, the party selectorates prioritize strategical electability over intra-party related factors in order to increase the chances to win the district mandate.

Strategy 3 is adopted by the parties’ selectorates in those nomination processes in which there are no or very little chances for the party to win the district. But at the same time, there is—as a result of the prevalent form of double candidacies (see section 3)—a chance for a promising spot on the party list.

“It was clear that we cannot win the district seat. Therefore, our view was on the state party list (…). Accordingly, the strategy for the intra-party process has been: Who can get a safe spot on the list? This question cannot be answered globally. One has to investigate who will be nominated by the other districts, who also needs to get a safe spot on the party list etc. The result of this exploration defines the profile we are looking for” (I2).

Thus, the perspective of the local selectorate shifts strategically from the local district to the regional intra-party competition for the state party lists. The state party lists are regularly constructed on the basis of quota and proportional rules, i.e., for incumbency, region, gender, age, or interest groups (see Reiser, 2014a; Ceyhan, 2018; Höhne, 2017). The strategy is that a district candidate who meets specific selection criteria for the state party lists has better chances for a safe spot on the state party list and by that guarantees the representation of the district in the Bundestag. Therefore, the local party branches anticipate strategically the selection criteria for the state party list already during nomination process at the district level.

“We knew that the three incumbents who re-run will be given priority on the state party list—these have been two men and one women. Therefore, we knew that the best spot we can get is the second spot for a female candidate of our region. This spot, spot X on the state party list, can be regarded as safe while the third spot for a male candidate from our region is hopeless. That’s why we knew from the beginning that a female candidate will win the intra-party competition in our district. This has been clear to all party members since there has been no single male aspirant—it has been a competition of female candidates” (I100).

This example clearly shows that the anticipated criterion for the state party list is getting the primary selection criterion in the district. The other central selection criteria continue to be relevant if there are more aspirants who fulfil this criterion. Thus, the selectorate does take up a regional intra-party perspective and strategically anticipates the regional selection criteria in order to meet the electoral goal.

A fourth type of strategic considerations is found in districts where there is no chance to win a mandate, neither directly nor via the list. In these cases, the perspective shifts from the demand side regularly to the supply side of candidate selection. The interviewed party elites state that there are no or hardly aspirants who are willing to campaign and invest time and money under these conditions. As a response to this, two different strategies have been adopted in the investigated districts:

The future-oriented strategy aims at developing someone for future candidacies and elections. Thus, the current candidacy has the goal to increase the electoral chances for upcoming elections, either by increasing public awareness in the local district or by improving the chances for a winnable spot on the state party list for upcoming elections:

“It is clear that the district is unwinnable for our party. And it was also clear that we would not get a promising spot on the party list. We assume that it will be a long walk and we expect to have a chance in 8 years to get a good spot on the party list” (I24).

While this kind of “development-candidacy” is often adopted as an individual strategy by aspirants, it is rare as a strategy of the parties’ selectorate. The main reason is according to the party elites that it requires a long-term commitment for one candidate which is hardly in the interest of the majority of the party actors.

Therefore, the dominant “strategy” in these hopeless districts is short-term and has the main goal to find a sacrificial lamb (Thomas and Bodet, 2012), hence someone who is willing to run despite the fact that he or she has no chance to win. Accordingly, aspirants in these hopeless districts are nominated even though they often do not fulfil the basic selection criteria of the selectorate, e.g., long-term party engagement.

So, overall, the analysis reveals that the strategies of the selectorate differ systematically along the two central dimensions of inter- and intra-competition on two different levels: 1) local inter-party competition, and 2) regional intra-party competition.

1) The first dimension is the inter-party competition in the electoral district since the strategies differ between safe, contested, and hopeless districts for the specific party.

2) The second dimension is the regional intra-party competition: Due to the prevalent form of double candidacies in the German mixed member electoral system, the district party can also get a representative of the district in the German Bundestag by winning a mandate via the state party list. Therefore, the regional intra-party competition for safe or at least promising spots on the state party list is the second relevant dimension for intra-party candidate selection in the electoral district.

These two dimensions generate four ideal types of strategies (see Table 1). They can be explained by the opportunity structure of the German mixed member electoral system which is characterized by the prevalence of dual candidacy and the decentralization of candidate selection.

The analysis clearly reveals that the local selectorate in the German districts strives to achieve both goals: to have an MP of the local party branch (office-seeking) who is loyal to the local party (organizational goal). If the office seems to be secured (in particular in safe districts), the selectorate looks for the “best candidate for the local party,” thus striving for a candidate who is loyal to the local party. This local and purely intra-party perspective is reflected in the most important selection criteria. However, if the district is not safe for the specific party, the selectorate strategically adapts the selection criteria to the specific opportunity structure: If the district is contested, the electability of the candidate becomes priority over party loyalty. Thus, the selectorate strives primarily for the best candidate for the local voters instead of the best candidate for the local party which leads to a higher personalization and an increased role of voter earning attributes in the selection process. If there are, however, chances for a safe or promising spot on the state party list, the strategy focuses on the regional intra-party competition. Therefore, the selectorate anticipates the selection criteria for the selection process of the state party lists in order to increase the chances for a mandate of the local party branch. Thus, the study reveals that due to the mixed-member electoral system and the prevalence of dual candidacies, intra-party competition in the districts is a two-level game.

Additionally, two significant qualifications have to been made with regard to the strategies of the selectorates:

First, the strategy itself is sometimes contested within the selectorate. This is in particular true for those cases in which the local and regional competitive context is ambiguous and the evaluation how to maximize the chances to win a mandate varies within the selectorate. For instance, in cases where there is both a minor chance to win the district and a minor chance to get a promising spot on the party list, the strategy itself is part of the intra-party competition and selection process.

Second, the role of the local party elites differs systematically dependent on the inclusiveness of the selectorate: Delegates—which usually have party and/or local offices—are likely to be aware of the loyalty-electability trade-off and are willing to act strategically in order to increase the chances to win a mandate. In contrast, the rank-and-file party members are usually taking up an organizational perspective and thus prioritize party loyalty over electability—independently of the intra- and inter-party competitive context. Therefore, the party elites argued in the interviews that they “need” to take up a more active role in the selection process in order to convince the ordinary members of a strategic adaption of the selection criteria and thus to enforce the decision. This points to a trade-off between open and democratic selection processes and the adaption of strategies.

Interestingly, the analysis does not reveal significant differences in the influencing factors on the strategies between the political parties. Of course, the share of the specific strategies varies due to the different party strengths and thus the different competitive context: Since the CDU and the CSU have the highest share of safe districts, strategy 1 was prevalent for these parties. In contrast, the Left party hardly has safe districts why type 1 was hardly applicable. However, if one controls for these factors, the parties’ selectorates react in the same manner to the loyalty-electability trade-off during candidate selection by strategically adapting the selection criteria.

Conclusion

The main aim of this article has been to explain the strategies of the parties’ selectorates in the process of candidate selection. At the outset, the article argues that research on intra-party candidate selection has hardly taken into account these strategies as an important element of the demand side of the recruitment processes. Since the selectorate is regularly forced to balance the competing goals of loyalty and electability in the process of candidate selection, the selectorate—dependent on the opportunity structure—nominates candidates for strategic considerations, and therefore strategically adjust the selection criteria and outcome of selection criteria. As such, the strategies of the parties’ selectorate are an important explanatory link between the goals and context factors of candidate selection on the one side and the adopted selection criteria and the outcome of candidate selection on the other side.

To increase our knowledge on these strategies, the article has analyzed the local selectorates’ strategies in district selections in Germany’s mixed-member electoral system. The analysis reveals that the selectorates strive to achieve both goals: to get an MP of the district who is loyal to the local party. If the seat is safe, the selectorates adopt the traditional inward oriented selection criteria. However, if the seat is not safe, they prioritize the electoral goal over the local party organizational goal and strategically adapt the selection criteria to the opportunity structure. By considering both local inter-party competition and regional intra-party competition, they either take up a local voters’ perspective or anticipate the selection criteria of the state party lists. The strategies are also influenced by the intra-party selection methods: Since candidate selection is highly decentralized, the local party selectorates clearly prioritize territorial local representation over all other types of representation. The default setting of the local selectorate is to look for a candidate who is loyal to the local party and not necessarily to the national and/or regional party. This local focus is, however, strategically adapted by a regional perspective if the selectorate anticipates selection criteria for the state party list. Thus, the study reveals that due to the mixed-member electoral system and the prevalence of dual candidacies, intra-party competition in German districts is a two-level game. Overall, the findings of the study contribute to the existing literature in three ways: First, it contributes to the literature on contamination effects in mixed-member electoral systems (Ferrara and Erik, 2005; Crisp, 2007; Papp, 2019). The study clearly confirms that the two tiers of the election systems and the two formally independent forms of nominations are de facto not independent from each other in the German mixed member electoral system. By revealing the ‘anticipation strategy’ at the district level it furthermore reveals a so far overlooked form of contamination. In addition, the inductively derived strategies of the local selectorates provide new insights into the logics of these contamination effects.

Second, the results also add knowledge to the literature on the effect of decentralized candidate selection methods on descriptive representation. In line with previous research, the analysis shows that in safe districts the party selectorates clearly prioritize territorial local representation over social representation (Hazan and Rahat, 2010; Childs and Cowley, 2011). This results for instance in low shares of women being nominated and elected in these safe districts (see Reiser, 2014b; Davidson-Schmich, 2016; Bieber, 2021). However, the analysis has also revealed that in nomination processes in which there are no or very little chances for the party to win the district, the local party branches anticipate during the nomination process at the district level strategically the logic of ticket-balancing and the selection criteria for the state party list (Reiser, 2014a). Thus, in these cases, gender quota and other informal rules for social representation outplay local territorial representation.

Third, the findings contribute to the existing literature on the personalization of politics (Pedersen and Rahat, 2021). The analysis has shed light on the dynamics of strategic considerations of the party selectorates with regard to the “loyalty-electability trade-off” (Ascencio and Kerevel, 2020) during candidate selection. The results of this study suggest that party loyalty – although it is the highest preference for the local selectorates – is getting less relevant as selection criteria for candidate selection due to new competitors, increased volatility and the subsequent decrease of safe districts. Instead, as part of the vote-seeking strategy of the local parties' selectorates in competitive districts, it is very likely that the candidates and their vote-earning characteristics are getting increasingly more important during candidate selection. Further research might focus on the impact of the specific strategies of the selectorates and the outcome of candidate selection as and important explanatory factor for the campaign behavior of the candidates, their legislative behavior (Papp and Zorigt, 2016; Zittel and Nyhuis, 2021) and the impact on political parties.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2021.780235/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1Certain criteria can be regarded as relevant for both goals. For instance, engagement in local offices is perceived important with regard to organizational goals, but also from an electability strategy since it can also increase public awareness (Put et al., 2021).

2The German party system has long been characterized by a high stability and continuity (Poguntke, 2015). After unification, the party system had developed in a stable five-party system with the Social Democratic Party (SPD), the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and the Christian Social Union (CSU), the Liberal Democratic Party (FDP), the Green Party, and the Left Party. At the Federal Elections 2017, the new right-wing populist party Alternative for Germany (AfD) entered the Bundestag for the first time.

3At the Federal Elections 2009, six parties won mandates: Social Democrats (SPD), Christian Democrats (CDU) and their Bavarian sister party Christian Socialist Union (CSU), Green Party, Left Party, and Free Democratic Party (FDP).

References

Adams, J., and Merrill, S. (2008). Candidate and Party Strategies in Two-Stage Elections Beginning with a Primary. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 52 (2), 344–359. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2008.00316.x

Andeweg, R. B., and Thomassen, J. (2011). Pathways to Party Unity: Sanctions, Loyalty, Homogeneity and Division of Labour in the Dutch Parliament. Party Polit. 17 (5), 655–672. doi:10.1177/1354068810377188

Ascencio, S. J., and Kerevel, Y. P. (2020). Party Strategy, Candidate Selection, and Legislative Behavior in Mexico. Legislative Stud. Q. 46, 713–743. doi:10.1111/lsq.12300

Ashe, J., Campbell, R., Childs, S., and Evans, E. (2010). 'Stand by Your Man': Women's Political Recruitment at the 2010 UK General Election. Br. Polit. 5 (4), 455–480. doi:10.1057/bp.2010.17

Baumann, M., Debus, M., and Klingelhöfer, T. (2017). Keeping One's Seat: The Competitiveness of MP Renomination in Mixed-Member Electoral Systems. J. Polit. 79 (3), 979–994. doi:10.1086/690945

Behnke, Joachim., Baur, Nina., and Behnke, Nathalie. (2006). Empirische Methoden der Politikwissenschaft. North Rhine-Westphalia: Paderborn.

Best, Heinrich., and Cotta, Maurizio. (2000). “Elite Transformation and Modes of Representation since the Mid-nineteenth Century: Some Theoretical Considerations,” in Parliamentary Representatives in Europe 1848–2000: Legislative Recruitment and Careers in Eleven European Countries. Editors Heinrich Best, and Maurizio Cotta (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Berz, J., and Jankowski, M. (2022). Local preferences in candidate selection. Evidence from a conjoint experiment among party leaders in Germany. Party Pol. Advance Online Publication. doi:10.1177/13540688211041770

Bieber, I. (2021). Noch immer nicht angekommen? – Strukturelle Geschlechterungleichheit im Deutschen Bundestag. Polit Vierteljahresschrift. doi:10.1007/s11615-021-00360-9

Bille, L. (2001). Democratizing a Democratic Procedure: Myth or Reality? Party Polit. 7 (3), 363–380. doi:10.1177/1354068801007003006

Borchert, J., and Reiser, M. (2010). Friends as Foes: The Two-Level Game of Intra-Party Competition in Germany. Mimeo: University of Frankfurt.

Bräuninger, Thomas., Debus, Marc., Müller, Jochen., and Stecker, Christian. (2020). Parteienwettbewerb in Den Deutschen Bundesländern. Wiesbaden: Springer.

Carey, J. M., and Shugart, M. S. (1995). Incentives to Cultivate a Personal Vote: A Rank Ordering of Electoral Formulas. Elect. Stud. 14 (4), 417–439. doi:10.1016/0261-3794(94)00035-2

Carty, R. K. (1980). Politicians and Electoral Laws: An Anthropology of Party Competition in Ireland. Polit. Stud. 28 (4), 550–566. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.1980.tb01258.x

Ceyhan, S. (2018). Who Runs at the Top of Party Lists? Determinants of Parties' List Ranking in the 2013 German Bundestag Election. German Polit. 27 (1), 66–88. doi:10.1080/09644008.2017.1320391

Childs, S., and Cowley, P. (2011). The Politics of Local Presence: Is there a Case for Descriptive Representation? Pol. Stud. 59 (1), 1–19. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.2010.00846.x

Cordero, G., and Coller, X. (2015). Cohesion and Candidate Selection in Parliamentary Groups. Parliamentary Aff. 68 (3), 592–615. doi:10.1093/pa/gsu008

Cordes, M., and Hellmann, D. (2020). Wer ist der ideale Kandidat? Auswahlkriterien bei der Kandidatenaufstellung zum Deutschen Bundestag. ZParl 51 (1), 68–83. doi:10.5771/0340-1758-2020-1-68

Crisp, B. F. (2007). Incentives in Mixed-Member Electoral Systems. Comp. Polit. Stud. 40 (12), 1460–1485. doi:10.1177/0010414007301703

Crisp, B. F., Olivella, S., Malecki, M., and Sher, M. (2013). Vote-earning Strategies in Flexible List Systems: Seats at the price of unity. Elect. Stud. 32 (4), 658–669. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2013.02.007

Cross, W. (2008). Democratic Norms and Party Candidate Selection. Party Polit. 14, 596–619. doi:10.1177/1354068808093392

Cross, W. P., Katz, R. S., and Pruysers, S. (2018). The Personalization of Democratic Politics and the Challenge for Political Parties. Rowmann & Littlefield: ECPR Press.

Dalton, Russel. J. (2018). Political Realignment: Economics, Culture and Electoral Change. Oxford: OxfordUnivercity.

Davidson-Schmich, Louise. (2016). Gender Quotas and Democratic Participation: Recruiting Candidates for Elective Offices in Germany. Ann Arbor, MI: New Comparative Politics.

Detterbeck, K. (2016). Candidate Selection in Germany. Am. Behav. Scientist 60 (7), 837–852. doi:10.1177/0002764216632822

Dodeigne, J., and Meuleweater, C. (2014). Popular Candidates and/or Party Soldiers? Vote-Seeking and Policy-Seeking Parties' Strategies in Party Candidate Selection at the 2014 Belgian Regional and Federal Elections. MIMEO.

Ferrara, Ederico., and Erik, S. (2005). “Herron and Misa Nishikawa,” in Mixed Electoral Systems. Contamination and its Consequences (Basingstoke: Springer).

Gallagher, Michael. (1988). “Conclusion,” in Candidate Selection in Comparative Perspective. Editors Michael Gallagher, and Michael Marsh (Bristol: The Secret Garden of Politics), 236–283.

Gallagher, Michael., and Marsh, Michael. (1998). Candidate Selection in Comparative Perspective. Bristol: The Secret Garden of Politics, 236–283.

Hazan, Reuven. Y., and Rahat, Gideon. (2010). Democracy within Parties: Candidate Selection Methods and Their Political Consequences. Oxford.

Hazan, R. Y., and Voerman, G. (2006). Electoral Systems and Candidate Selection. Acta Polit. 41 (2), 146–162. doi:10.1057/palgrave.ap.5500153

Hennl, A. (2014). Intra-party Dynamics in Mixed-Member Electoral Systems: How Strategies of Candidate Selection Impact Parliamentary Behaviour. J. Theor. Polit. 26 (1), 93–116. doi:10.1177/0951629813489547

Herzog, Dietrich. (1975). Politische Karrieren: Selektion und Professionalisierung politischer Führungsgruppen. Opladen: Springer.

Höhne, Benjamin. (2017). Wie stellen Parteien ihre Parlamentsbewerber auf? Parteien, Parteiensysteme und politische Orientierungen. Editor Koschmieder Carsten (Wiesbaden), 227–253.

Kaack, Heino. (1969). Wahlkreisgeographie und Kandidatenauslese. Regionale Stimmenverteilung, Chancen der Kandidaten und Ausleseverfahren. Bonn: dargestellt am Beispiel der Bundestagswahl 1965.

Klingemann, Hans-Dieter., and Wessels, Bernhard. (2001). “The Political Consequences of Germany’s Mixed-Member System: Personalization at the Grass Roots,” in Mixed-Member Electoral Systems: The Best of BothWorlds. Editors Matthew. Shugart, and Martin. P. Wattenberg (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 279–297.

Kriesi, Hanspeter., Grande, Edgar., Lachat, Romain., Martin, Dolezal., , , Bornschier, Simon., and Frey, Timotheos. (2008). West European Politics in the Age of Globalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Manow, Philip. (2015). Mixed Rules, Mixed Strategies – Parties and Candidates in Germany’s Electoral System. Essex: ECPR Press.

Norris, Pippa. (1997). “Introduction: Theories of Recruitment,” in Passages to Power. Legislative Recruitment in Advanced Democracies. Editor Pippa Norris (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 1–14.

Norris, Pippa., and Lovenduski, Joni. (1995). Political Recruitment. Gender, Race and Class in the British Parliament. Cambridge: University Press.

Norris, P., and Lovenduski, J. (1993). 'If Only More Candidates Came Forward': Supply-Side Explanations of Candidate Selection in Britain. Br. J. Polit. Sci 23, 373–408. doi:10.1017/s0007123400006657

Ohmura, T., Bailer, S., Meiβner, P., and Selb, P. (2018). Party Animals, Career Changers and Other Pathways into Parliament. West Eur. Polit. 41 (1), 169–195. doi:10.1080/01402382.2017.1323485

Papp, Z. (2019). Same Species, Different Breed: The Conditional Effect of Legislator Activities in Parliament on Re-selection in a Mixed-Member Electoral System. Parliamentary Aff. 72, 59–75. doi:10.1093/pa/gsx049

Papp, Z., and Zorigt, B. (2016). Party-Directed Personalisation: The Role of Candidate Selection in Campaign Personalisation in Hungary. East European Pol. 32 (4), 466–486. doi:10.1080/21599165.2016.1215303

Pedersen, H. H., and Rahat, G. (2021). Introduction: Political Personalization and Personalized Politics Within and Beyond the Behavioural Arena. Party Pol. 27 (2), 211–221. doi:10.1177/1354068819855712

Poguntke, T. (2015). "The German Party System After the 2013 Election: An Island Of Stability in a European Sea of Change?", in Anti-Party Parties in Germany And Italy. Protest Movements and Parliamentary Democracy. Editors A. de Petris, and T. Poguntke. Rome: LUISS University Press, 235–253.

Preece, J. R. (2014). How the Party Can Win in Personal Vote Systems: The "Selectoral Connection" and Legislative Voting in Lithuania. Legislative Stud. Q. 39, 147–167. doi:10.1111/lsq.12040

Put, G.-J., Muyters, G., and Maddens, B. (2021). The Effect of Candidate Electoral Experience on Ballot Placement in List Proportional Representation Systems. West Eur. Polit. 44 (4), 969–990. doi:10.1080/01402382.2020.1768664

Reiser, M. (2013). "Ausmaß und Formen des innerparteilichen Wettbewerbs auf der Wahlkreisebene: Nominierung der Direktkandidaten für die Bundestagswahl 2009", in Faas, Thorsten/Arzheimer, Kai/Roßteutscher, Sigrid/Weßels, Bernhard (Hrsg.): Koalitionen, Kandidaten, Kommunikation. Analysen zur Bundestagswahl 2009. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 129–148.

Reiser, M. (2014a). "The Universe of Group Representation in Germany: Analyzing Formal and Informal Party Rules and Quotas in the Process of Candidate Selection", in Int. Pol. Sci. Rev. 35 (1), 56–66. doi:10.1177/0192512113507732

Reiser, M. (2014b). Innerparteilicher Wettbewerb bei der Kandidatenaufstellung: Ausmaß – Organisation – Selektionskriterien. University of Frankfurt: MIMEO.

Reiser, M. (2018). "Contagion Effects by the AfD? Candidate Selection in Germany", in Coller, Xavier/Codero, Guillermo/Jaime-Castillo, Antonio M. (Hrsg.): The Selection of Politicians in Times of Crisis. New York, London: Routledge, 81–97.

Schindler, Danny. (2020). More Free-Floating, Less Outward-Looking. How More Inclusive Candidate Selection Procedures (Could) Matter. Party Polit.

Schlesinger, Joseph. A. (1966). Ambition and Politics: Political Careers in the United States. Chicago: Rand McNally.

Schüttemeyer, Suzanne. S., and Sturm, Roland. (2005). Der Kandidat – das (fast) unbekannte Wesen: Befunde und Überlegungen zur Aufstellung der Bewerber zum Deutschen Bundestag. Z. für Parlamentsfragen 36, 539–553. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24236416.

Selb, Peter., and Lutz, Georg. (2014). Lone Fighters: Intraparty Competition, Interparty Competition, and Candidates' Vote Seeking Efforts in Open-Ballot PR Elections. Elect. Stud. 39, 329–337. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2014.04.009

Shomer, Y. (2017). The Conditional Effect of Electoral Systems and Intraparty Candidate Selection Processes on Parties' Behavior. Legislative Stud. Q. 42, 63–96. doi:10.1111/lsq.12141

Shugart, Matthew. S., and Wattenberg, Martin. P. (2004). Mixed Member Electoral Systems: The Best of Both Worlds? Oxford: Oxford Univercity.

Shugart, M. S., Valdini, M. E., and Suominen, K. (2005). Looking for Locals: Voter Information Demands and Personal Vote-Earning Attributes of Legislators under Proportional Representation. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 49 (2), 437–449. doi:10.1111/j.0092-5853.2005.00133.x

Siavelis, P. M., and Morgenstern, S. (2008). Candidate Recruitment and Selection in Latin America: A Framework for Analysis. Lat. Am. Polit. Soc. 50 (4), 27–58. doi:10.1111/j.1548-2456.2008.00029.x

Siavelis, P. (2002). The Hidden Logic of Candidate Selection for Chilean Parliamentary Elections. Comp. Polit. 34, 419–438. doi:10.2307/4146946

Spies, D. C., and Kaiser, A. (2014). Does the Mode of Candidate Selection Affect the Representativeness of Parties? Party Polit. 20 (4), 576–590. doi:10.1177/1354068811436066

Stratmann, T., and Baur, M. (2002). Plurality Rule, Proportional Representation, and the German Bundestag: How Incentives to Pork-Barrel Differ across Electoral Systems. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 46, 506–514. doi:10.2307/3088395

Tavits, M. (2009). The Making of Mavericks. Comp. Polit. Stud. 42 (6), 793–815. doi:10.1177/0010414008329900

Thomas, M., and Bodet, M. (2012). Sacrificial Lambs, Women Candidates, and District Competitiveness in Canada. Elect. Stud. 32, 153–166. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2012.12.0010

Weßels, B. (1997). “Germany,” in Passages to Power: Legislative Recruitment in Advanced Democracies. Editor P. Norris (Cambridge: Cambridge Univercity), 76–97.

Weßels, Bernhard. (2016). “Wahlkreiskandidaten und politischer Wettbewerb,” in Wahlen und Wähler: Analysen aus Anlass der Bundestagswahl 2013. Editors Harald Schoen, and Bernhard Weßels. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, 181–204.

Xavier Coller, Guillermo Codero, M Antonio, and J Castillo (2018) (Editors) The Selection of Politicians in Times of Crisis (London,UK: Routledge).

Zittel, T., and Gschwend, T. (2008). Individualised Constituency Campaigns in Mixed-Member Electoral Systems: Candidates in the 2005 German Elections. West Eur. Polit. 31 (5), 978–1003. doi:10.1080/01402380802234656

Keywords: candidate selection, intra-party selection, mixed member electoral system, Germany, selection criteria

Citation: Reiser M (2022) Strategies of the Party Selectorate: The Two-Level Game in District Selections in Germany’s Mixed Member Electoral System. Front. Polit. Sci. 3:780235. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.780235

Received: 20 September 2021; Accepted: 09 November 2021;

Published: 11 March 2022.

Edited by:

Guillermo Cordero, Autonomous University of Madrid, SpainReviewed by:

Jeremy Dodeigne, University of Namur, BelgiumAntonio M. Jaime-Castillo, National University of Distance Education (UNED), Spain

Copyright © 2022 Reiser. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Marion Reiser, bWFyaW9uLnJlaXNlckB1bmktamVuYS5kZQ==

Marion Reiser

Marion Reiser