- Institute of Political Research, National Centre for Social Research, Athens, Greece

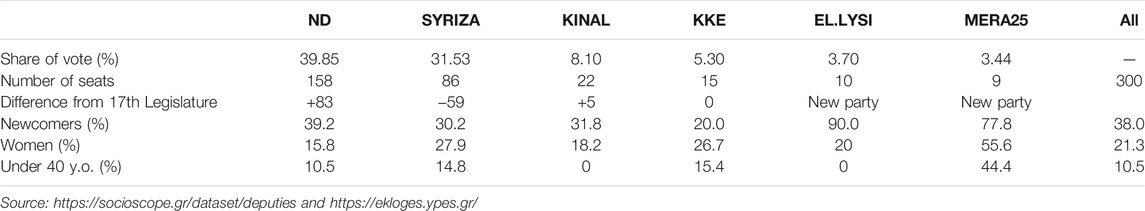

The July 2019 national elections in Greece marked the return in power of the conservative party of ND, one of the two pillars of the traditional Greek bipartisanism. Turnover in these elections nearly reached 40%; more than two thirds of the current Parliament MPs were first elected during the crisis, since old parliamentarians slowly give away their seats to newcomers. The aim of this paper is twofold: 1) explore candidate selection mechanisms of old and new parties in Greece inquiring what -if any- has changed in these mechanisms after the Great Recession and whether they adopt IPD in a wider extent; and 2) investigate the sociodemographic profile of newcomers vis-à-vis older Parliamentarians in order to check if the outcome of the elections has changed in terms of a more socially diverse profile. Given that the issue of candidate selection (and election) is mostly based on unwritten rules, our findings will rely on written party rules (such as party manifestos), on original sociodemographic data and on personal interviews. We tentatively suggest that not much has changed in the candidate selection mechanisms in Greece. ND made limited use of its open registry of candidates, whilst SYRIZA applied the same rules as in previous elections. We conclude that, the crisis in Greece offered the opportunity structures for the mass renewal of its parliamentary elite and for a somewhat more socially diverse pool of successful candidates, but its effect quickly disappeared since new MPs resemble more independent political entrepreneurs and have less social and political ties.

Introduction

Trust in political parties is declining steadily across Europe for the past 2 decades, whilst latest figures reveal an even bleaker picture (Standard Eurobarometer, 2021). Greece scores extremely low in all measures on trust in political parties during the last decade; the Great Recession, and its much-discussed impact on Greek economy, society, and the political system (Bosco and Verney, 2016; Morlino and Raniolo, 2017; Katsikas et al., 2018) has left its mark on all attitudes regarding political institutions such as parties and the Parliament. Many works investigate this strained relationship between parties and voters (Teperoglou and Tsatsanis, 2014; Verney, 2014; Tsatsanis, 2018). The global financial and economic crisis had an clear impact on the legitimacy of political elites (Vogel et al., 2019). The way political actors chose to respond to the challenging of their position was not uniform; in some cases, they opted for an increase in political professionalization, to secure their positions from challengers; in other cases, they opened the access though more inclusive recruitment methods (ibid p. 12–16). In the latter case, the “failure of mainstream parties” and the crisis of legitimacy that they faced (Ignazi 2021) was addressed through calls for more representative and responsive models of party organization, with Intra-Party Democracy (IPD) becoming the new focus of analysis.

The purpose of this article is to analyze the candidate selection mechanisms adopted in Greece by mainstream and challenger parties before the July 07, 2019 elections, in order to assess their impact on MPs’ socio-demographic profiles. First, we review main developments in the literature on IPD and candidate selection under the light of the Greek case; then we move on to a short presentation of the background to the elections and the 2019 electoral results. We then proceed to our main section, where we present our data on the selection process and analyze the profile of successful candidates elected in Parliament.

The article addresses two questions: 1) did the Great Recession resulted in more IPD in old and new parties, and following from that, 2) are political parties today more socially diverse than they were a decade ago?

This paper aims to bring together analysis on party changes regarding candidate and leader selection and the impact these changes might have on the socio-demographic profile of MPs, by focusing on two parties, one mainstream (ND) and one challenger (SYRIZA) both during and after the Great Recession. The parties of ND and SYRIZA are the main foci of analysis, because their presence both during and after the crisis, and their share of seats in Parliament, enables past comparisons. Data on MPs socio-political profile come from the Socioscope Database,1 that collects and codes information on all elected MPs in Greece.2 Additional information on the candidate selection process for ND and SYRIZA was collected from three semi-structured personal interviews that were conducted; one with a high-ranking ND party official and two with experienced SYRIZA MPs.

Our findings will provide insight on the organizational developments of a relatively new party system that is usually overlooked when analyzing party developments and party innovation. In addition, the issue of personalization and professionalization will be addressed as potential explanation in an open-list electoral system.

Developments in Candidate and Leader Selection

The recruitment and selection of political elites are critical functions of democracy since who gets elected and how reveals organizational and ideological configurations that can shape the outcome. Although the question of “how parties organize” (Katz and Mair, 1994) has always been central to the study of parties and elections, in the last decade there is a growing body of work regarding changes in party organization (Gauja, 2017; Scarrow et al., 2017; Borz and Janda, 2020) and in parties’ selection mechanisms (Sandri and Seddone, 2015; Seddone and Sandri, 2021). The Great Recession and the call for more democracy and accountability by the old political elites brought many changes in both established and new parties in their organizational profile and candidate selection methods (Cordero and Coller, 2018; Coller et al., 2018; Alexandre-Coller et al., 2020) since major political crisis and the threat they present to democratic legitimacy mobilize parties and provide the opportunity for change (Detterbeck 2018).

Many such initiatives are analyzed under the framework of Intra-Party Democracy (IPD) a term that, although may mean different things to different parties (Cross and Pillet, 2015, p. 2), has been conceptually clarified (Poguntke et al., 2016, p. 11) and broken down into three basic elements: 1) changes in the way parties select their leaders and candidates; 2) changes in the way parties take their decisions on ideological issues and draft their programs; and 3) changes in the ways parties organize internally their various bodies. In this section we will address the first of these elements.

As past literature suggests (Gallagher and Marsh, 1988) elements of IPD in leader and candidate selection have been around for decades; nevertheless, changes adopted by parties, especially new challenger parties (Hobolt and Tilley, 2016) that emerged during the Great Recession revived the discussion. New parties such as Podemos in Spain, Five Star Movement in Italy, or La République En Marche in France, share some or all the characteristics of the new challenger parties, which evolve around participatory democracy, technological innovations, and new methods of deliberation (Ignazi, 2021), identifying those parties sometimes as movement parties (Della Porta et al., 2017) and others as digital parties (Gerbaudo, 2021). Many of these measures have been adopted by mainstream parties as well in an effort to respond to citizens’ alienation from politics and growing distrust and reconnect with society (Coller and Cordero, 2018; Cordero et al., 2018).

Parties adopt IPD to respond to the legitimacy crisis (Seddone and Sandri, 2021, p. 205), with (some kind of) primaries for the appointment of leaders and candidates being the most common option. Hazan and Rahat (2010) have provided an analytical framework that analyzes candidate selection mechanism, claiming that the outcome of the selection may be more or less representative, depending on the method of selection. According to their typology, the fewer that select the candidates, the more exclusive is the process, and the more central the territorial level where this selection takes place, the more centralized the process. Yet, there is no clear consensus on the effect of more inclusive measures on candidate’s sociodemographic profiles since literature has offered mixed evidence. Sandri and Sendone (2021) suggest that IPD does not seem to trigger a clear rejuvenation of the political elites, although MPs chosen by more inclusive methods tend to be more diverse regarding gender and age (ibid, p. 210); other evidence (Perez- Nievas et al., 2021) suggests that more inclusive methods may help certain social groups (young people) but hinder others (women). Even if there is no clear pattern, primaries or more inclusive methods tend to enable candidates with no previous political experience to enter politics and boost their careers by gaining visibility, which as Seddone and Sandri argue “in times of personalization of politics represents an essential resource” (ibid, p. 211) although this may depend on how strong the leader of their party is (Marino et al., 2021). Therefore, the tendency for “primarization” of politics (Alexande-Collier et al., 2020) may facilitate the “de-professionalization” (ibid) of parliamentary elites. On the other hand, the opening of candidate and leader selection towards more inclusive mechanism facilitates personalization since candidates compete through personal campaigns (Rahat and Kenig, 2018, p. 149–150). Personalization and professionalization are therefore often regarded as negative side-effects of IPD since in many cases such measures give more impact to the leader and to individual candidates and change the balance of power inside the party.

Regardless of the effect of such initiative, the drivers for change can be external to the party or internal. Harmel and Janda (1994) argue that parties change only when there is a powerful external shock related to their primary goal. If a party’s primary goal is electoral success, then loss of power is the driver for change. Internal factors for change can be leadership changes (Harmel and Janda, 1994, p. 264–265). Sandri et al. (2015, p. 186–188) distinguish between different systems where change takes place: the political, the party and the intra-party. Reaction to party disaffection takes place at the system level; reaction to electoral defeat or the contagion effect when other parties adopt such measures take place at the party level, whilst reaction of party elites or party members take place at the intra-party level. The age and governmental experience of the party are also factors related to party change: Challenger parties respond with direct democracy and innovations whilst they are characterized by a different relation with society; mainstream parties respond by giving more say to ordinary members at the expense of the party base (Ignazi 2020).

Based on the above, we identify three possible explanatory factors as drivers for change regarding candidate selection mechanisms and candidates’ profiles in Greece.

(1) In terms of party age, we expect challenger parties to differentiate from mainstream parties in their candidate selection mechanism and the profile of their MPs, therefore we expect SYRIZA to have more open candidate selection mechanisms and a less traditional sociodemographic profile of its MPs.

(2) In terms of the drivers for change, we expect parties that have experienced electoral defeat to be more likely to re-organize and adopt new methods of candidate selection in order to re-gain their electoral appeal. In the Greek case we would therefore expect ND to adopt new methods after its electoral defeat since for ND, as an office maximizer party, loss of power seems to be the driver for change, that can initiate an internal change (leader change) which will then lead to party change.

(3) Regarding the personalization/professionalization argument, we would expect both parties to gradually select candidates without prior political experience, more professional characteristics, and less ties with the party.

The Political Events Prior to the July 2019 Elections and the Electoral Outcome

The year 2019 was nothing short of elections. For the first time in Greece four elections were conducted at the same year, in a period of less than 2 months: the triple elections of the 26th of May 2019 (European Elections, Regional and Municipal Elections, all held on the same day) and snap National elections shortly after, on July 7. The outcome of the July elections, the first to be conducted in the “post-memoranda” era, since Greece had officially exited the bailout programs in August 2018, was a clear victory for Conservative ND, and Kyriakos Mitsotakis, whom for the first time run elections as its leader. ND gained 39.85 percent of the vote and 158 seats in Parliament, compared to the 28.09 percent and 75 seats of the previous Parliament, and formed a single-party government, after nearly a decade of coalition governments.

Although coalition governments were the exception rather than the rule in Greece, they had come to become a recurring theme in the post-crisis party system. Party fragmentation and electoral dealignment resulted in a fluid political system with the rising of new parties and the electoral revival of former marginal ones (Tsatsanis and Teperoglou, 2019, p. 231). SYRIZA, the party in office since 2015, mostly anticipated its defeat, after its poor electoral result in the preceding European and regional/municipal elections, that caused Alexis Tsipras to call for snap elections. Its share of vote dropped from 35.44 to 31.53 percent, winning 86 seats instead of 145. SYRIZA’s coalition partner, ANEL, did not run in the 2019 National Elections after the party’s disappointing electoral results in the European Elections a few weeks earlier.3 The fallout between Alexis Tsipras and ANEL’s leader Panos Kammenos over the signing of the Prespa Agreement in June 2018, resulted in a major shift in the political agenda and political discourse. The Prespa Agreement, settling a long dispute between Greece and North Macedonia over its name, shifted the agenda from economic issues to issues of national identity and foreign policy (Skoulariki, 2021). Panos Kamnenos left the coalition government after the Agreement’s ramification in January 2019, but some former ANEL MPs who became independent, backed the government, and voted for it, together with some MPs from POTAMI (Rori, 2020, p. 1027). The “Macedonian” issue permitted SYRIZA to appeal to another audience, this time not against Troika and the bailout agreements, but on an issue closer to the liberal centre. It therefore re-shuffled the party system bringing it closer to the traditional left/right divide (Tsatsanis and Teperoglou, 2019); some parties that had emerged during the crisis disappeared (Potami, Anel) others emerged on the new Nationalist front (Elliniki Lisi) or the radical left camp (MeRa25) whilst others that had splintered from SYRIZA during the crisis -belonging to the “memorandum” camp- went back (DIMAR).

Data and Research Design

Data on MPs come from the Members of the Greek Parliament (1989–2019) Database. The DB is a census of the entire population of Greek MPs and has information on all MPs that occupied a parliamentary seat -even for a single day- at the Greek Parliament, in the fourteen national elections held between 1989 (the 5th Parliamentary Term) and 2019 (the 18th Parliamentary Term). Currently the DB contains 1474 unique cases and 4367 entries. Biographical information were collected from sources such as the yearbooks published by the Hellenic Parliament, data from the Parliaments’ website and party and personal websites of the candidates and were then coded into variables, divided into two main groups: 1) the socio-demographic variables, which are fixed entries of the database, since the information about the same person does not change over time (e.g., gender, year of birth, place of birth, education), and 2) social and political experience variables which may take different values for the same person in another parliamentary term (e.g., the same person in a parliamentary term gets elected with party x and in another with party y). The selection of the variables that were included in the database followed the guidelines adopted by other similar works (Coller et al., 2014), such as information from official sources and the ability to retrieve information from an adequate number of CVs.

The three semi-structured personal interviews were conducted face-to-face in June and July 2021, two in the office of the subjects and one in an open space, in Athens. All were conducted in Greek, recorded, and then transcribed in a word processing software. All excerpts that are used in the article were translated in English by the author. Since the country was in lockdown until mid-May 2021, contact attempts were made at the beginning of June. After an initial search to identify those holding key positions in the candidate selection process prior to the July 2019 elections, five SYRIZA MPs and Party officials and six ND MPs and Party officials were selected. They were contacted via e-mail where the aim of the interview was explicitly stated, together with information on the protection of the interviewees’ data. Although the aim was to conduct face-to-face interviews, alternative modes (such as video interviews) were offered. Out of those contacted from SYRIZA, two current MPs accepted. The first interview was conducted on June 24, 2021 and lasted 25 min. The second interview was conducted on June 29, 2021 and lasted 34 min. Out of those contacted from ND only one senior party official accepted. The interview was conducted on July 16, 2021 and lasted 54 min. All those interviewed received before the interview a list of questions and signed an agreement. The final number of interviews is much lower than initially designed, probably due to time constrains of the individuals that were contacted or hesitation to participate. However, those that accepted had positions close to Kyriakos Mitsotakis and Alexis Tsipras and were well informed on the subject. It is accepted nevertheless that the number of interviews is low and that some aspects of the informal processes of candidate selection are not adequately highlighted.

Although the article uses a mixed methods research design, making use of both quantitative and qualitative data, the interview findings are expected to supplement the quantitative data that come from the socioscope dataset. Therefore, there use is complementary (Greene et al., 1989) to the main research question, which is that of the sociodemographic composition of ND and SYRIZA MPs elected in Parliament after the July 7, 2019 General Elections. The focus is on ND and SYRIZA since their current parliamentary groups are the only to satisfy the conditions of a continuous presence in Parliament both during and after the crisis, and an adequate number of MPs in numerical terms that will enable groupings and comparisons with the past.

Party Organization and Candidate Selection Process in Greece After the Great Recession

The Great Recession and its impact on the Greek party system attracted a wave of attention with a wealth of scholarly work, either on the electoral success of challenger SYRIZA, the rise of neo-Nazi Golden Dawn or the downfall and electoral decline of PASOK (for an overview see Tsirbas, 2020). Following SYRIZA’s rise to power after the January 2015 elections, the focus shifted on the two main political actors of the new two-partyism in Greece (Tsatsanis et al., 2020), conservative New Democracy (ND) and radical left SYRIZA. In recent years, a growing wealth of data on MPs’ descriptive and substantive representation has further expanded our knowledge of parliamentary elites in Greece. There is now evidence both regarding the differences in the profile of MPs before and after the Great Recession (Teperoglou et al., 2020) and the different political generations of MPs in recent Parliaments (Kakepaki, 2018; Kountouri, 2018; Koltsida, 2019). Evidence regarding changes in MPs profile are mixed: in some cases, they appear to be the product of slow change rather than the outcome of the crisis per se, however MPs from challenger parties had some characteristics that differentiated them from the old parliamentary elite.

In contrast to research on parties and elections, and more recently on candidates and MPs’ profiles, candidate selection mechanisms remain largely unexplored; interestingly, the only work available devoted to a single party, is work on PASOK, a party that electorally collapsed during the great recession. Research on the participatory attempt in PASOK’s party organs from 2004–2009 (Eleftheriou and Tassis, 2019) stresses that wider candidate selectorates were used only in less electorally important constituencies, whilst the impact of IPD in political careers shows that the party’s participatory experiment did not significantly change the profile of successful candidates (Kosmopoulos, 2021). Other work has highlighted that up until 2015 candidate selection mechanisms of ND and SYRIZA diverged and converged gradually once SYRIZA acquired government experience and opted for a more central and exclusive method of selection (Kakepaki, 2018, p. 106).

In the following section we will outline the main developments on candidate selection mechanisms of the two major parties (ND and SYRIZA) before the July 2019 national elections. ND is the most stable pillar of the Greek bipartism and the only party of the Third Hellenic Republic that always occupies either the governmental or the Opposition benches. Most work on NDs organizational profile stresses the importance of leadership changes (Alexakis, 2020), the use of party organization almost exclusively for electioneering purposes (Vernardakis, 2011) and the importance of prominent party cadres and family networks in party life (Pappas, 1998). Although these were often regarded as obstacles to the rebranding of the party, ND seems to be able to reinvent itself after long electoral defeats (Pappas and Dinas, 2006). Past work on ND suggests that over the years the strength of its parliamentary group and mass organization have weakened at the expense of the party leader and the professional cadres (ibid, p. 485). These observations highlight the fact that ND under a new leadership almost always tries to “re-invent” itself, therefore the emphasis on professionalization and innovation that accompanied Kyriakos Mitsotakis’ election could serve as explanatory factors for any innovative measures, together with the party’s positive electoral prospects.

The relationship of NDs candidates with society, either through a previous election to any position in local government or through a mandate in a trade union or professional organization is an important factor and is linked to the election to Parliament. Another aspect that has been particularly stressed is that of family tradition, as the existence of a family relationship seems to constitute a strong personal capital that facilitates (re)election in Parliament (Karoulas, 2019). Even today, the model of the parliamentary representative of ND comes closer to an archetypal image of a middle-aged male, coming from the liberal professions, with previous political expertise in other elected positions. However, changes in the MPs profiles highlight some new trends, such as the weakening of party ties. (Kakepaki, 2019).

In line with the trend towards more inclusive methods in leadership selection (Cross and Pilet, 2015) ND has adopted since 2012 a semi-open method of leader election, where all party members vote for the election of the party leader. Kyriakos Mitsotakis was elected leader of ND after a two-round election in December 2015 and January 2016. All those registered to vote in National Elections could participate in the leadership election, provided they registered, even on the day of the election, as party members. In the first round 404.0784 votes were cast and in the second 334.752.5 Bearing in mind that in the preceding elections of September 2015, ND had gained 1.526.400 votes, the ratio of voters in leadership selection/voters in national election is high; however, it is acknowledged that K. Mitsotakis mobilized for his election voters that did not necessarily come from ND’s traditional pool of voters (Rori, 2020, p. 1034). “It seems that Mitsotakis’ [election] creates a new compatibility for ND, which is why he can talk to people who also have very different political starting points, not just those people that were not involved in politics” (ND Interview 1).

After his election, Kyriakos Mitsotakis proceeded to the re-organization of the party at the 10th Party Congress that took place a few weeks after. Many changes were adopted in the party statute, related to its organizational structure, finances, and candidate selection process (Pappas, 2020, p. 65). New Secretaries were appointed, whilst the party was equipped with new faces belonging to a personal circle of trusted colleagues. Regarding candidate selection, although the process has always been centralized (Kakepaki et al., 2018) with the new party statute, it became officially centered around the leader. In article 30 of the ND Statute the candidate selection process is described as follows “The President of the Party draws up the ballot papers for the National and European Elections. To select candidates, he/she implements an evaluation system, establishes a Registry of Parliamentary Candidates and may consult the members of the Party” (New Democracy, 2018).

The Executives Registry (Mitroo Stelexon) was adopted as one major innovation in the recruitment process, not only for parliamentary candidates, but for selecting staff for the party machine. This registry, established long before the elections, served as an ongoing “open call” for aspirant candidates or party executives and was very much a personal project of Kyriakos Mitsotakis: “it was an open call that in fact bypassed the traditional structures of the party, it was a personal open call made by the president towards the society as a response to the very large stream of support that the president of ND had. While he was not supported by traditional party officials, he was eventually elected by the people who came to vote through the open election process […]. from then onwards there were many people who were interested in helping this project of Kyriakos Mitsotakis and he responded to this, to the will of the people, by making this open invitation, and the response was beyond all expectations” (ND Interview 1). The whole process had clear similarities with the recruitment process by HR departments where aspirant candidates passed interviews to assess their eligibility, whilst the entire process was supervised by the CEO of a large corporation.

Responsible for the ballot structure were a short group of senior party officials and people working close with Kyriakos Mitsotakis. They provided to him a long list of party candidates, built around 1) incumbent MPs, 2) new entries from the Registry and 3) aspirant candidates that had followed more traditional channels of communication (i.e., the party). Kyriakos Mitsotakis had the final say, although it is generally accepted that incumbent MPs may have a say on the ballot of their constituency. The open lists under a personal preference vote on the one hand helps them create an individual electoral base that will secure their re-election, on the other hand cannot secure their re-election if there is strong intra-party competition in their constituency. Therefore, most of the times, ballots are structured around incumbents, and depending on the number of seats in each constituency, make sure not to endanger their re-election with too many ‘strong’ candidates. This time, the fact that ND was expecting to increase its share of seats made things easier both for old and new candidates.

In the end, apart from the institutional provisions (gender quotas) NDs ballots were built around the above, whilst attributes that weighted in favour of prospective candidates were their professional characteristics and overall performance: “traditionally the area of the self-employed, the private sector, the market, so to speak, are over-represented, without of course meaning that there are no representatives from the public sector, the university community and so on. But, [these are] the priorities, the main priority that we wanted to express, […] ND wanted to express the transition from the sham, from the madness that had gripped the world in previous years, because of the memoranda and the economic crisis, [and move to] an era of moderation, focusing on the result, without passions, divisions, and divisive dilemmas, […] so this should be expressed by the candidates, because the local communities, at least in parties like New Democracy, […] they receive, they understand the political messages that the party transmits mainly through the persons who ultimately make up the ballots. New Democracy was, and remains, an “MP-centric”, party i.e. its MPs play a very important role in shaping its image and its operation.” (ND Interview 1). Different ideological streams were also taken under consideration, although these are more often referred to as traditions within the party, with family tradition being one of them. Larger or smaller political dynasties are considered ‘brand names’ that it would be foolish not to take advantage of, especially in a system of personal preference vote where the inclusion in the party lists of recognizable names can attract more votes.

In sum, ND’s candidate selection process pretty much followed past knowledge as described in previous research (Kakepaki, 2018). The Registry was the only innovation; however, it did not result in more IPD since its main function was to bypass party structures, especially party bureaucracy at the middle level, whilst its actual impact on candidate election is unclear.6 Leadership change was the main force behind these changes, whilst ballots were structured with the aim to offer clear alternatives to SYRIZA in terms of the profile of those that filled them up.

SYRIZA on the other hand seemed rather more skeptical to organizational changes. If leadership change is a force for change, then, the fact that Alexis Tsipras headed the party since 2012, meant that there was no “new leader effect.” The small radical-left party that rose to power in 2015 after the collapse of the old party system, failed to capitalize on its electoral rise in organizational terms (Eleftheriou, 2019, p. 162), whilst the party was pretty much neglected during the same time with no effort for any enlargement that would provide a pool of people capable to fulfil certain positions of power (SYRIZA, 2020). SYRIZA traditionally lacked a systematic recruitment strategy and preferred a loose approach based on its relationships with social movements and public figures of the Left, such as intellectuals, University Professors etc. This approach was pretty much reflected on the ballot structure: “there was no [recruitment strategy] within the 5 years that we were in government; the party had been neglected, we had all moved into governmental roles etc. And it was also not easy to join a party that was implementing a memorandum […], before 2019 our whole effort was directed at […] the State Ballot [Epikrateias] to include 4-5 people of wider prestige and from then on to have some decent people, women, men, young people, some people from the Environmental movement” (SYRIZA, Interview 1). The candidate selection process, as described in the party’s statute that has not changed since 2013 (SYRIZA, 2013), follows a bottom-up approach, where the local and regional party branches compile a long-list of candidates that is later approved by the Central Committee. After SYRIZA’s rise to power in 2015 the process became more centralized and exclusive, with a small informal committee of senior party members overseeing the process, to ensure a more unified and less prone to political differentiation parliamentary group (Kakepaki, 2018, p. 102–106). Prior to the July 2019 elections, the process remained unchanged: a small informal committee received the lists of the regional party offices and streamlined the results. Again, in contrast to ND, since SYRIZA was expecting to reduce its share of seats, the committee had a rather “easy” task: position most incumbent MPs in the ballots, include candidates that originated from its former or new allies and ty to secure election for several prominent figures that had served in government during the previous period as non-elected members of the cabinet. These criteria did not leave much room for maneuver and certainly did not need much scouting for new faces: “the formation of the ballot papers was a rather easy process, there was not much participation from non-party members, because they understood that they would take someone else’s place, […] incumbent MPs mostly were included, those Ministers who were not MPs [were included], the majority of the Ministers who were not MPs were included, [people from] the enlargement were included, and what was actually left as candidacies from below were supplementary, complementary” (SYRIZA, interview 2).

After the collapse of the coalition government at the beginning of 2019, SYRIZA embarked on a mission that has come to be known, as “enlargement.” This term reflects the effort to attract other forces of the left and center-left around SYRIZA in one unified front against ND. Although this strategy was fully adopted after the elections,7 SYRIZA’s ballots reflected to a large extent this attempt. Out of the eight non-SYRIZA MPs that voted for the ramification of the Prespes Agreement, four were included in the party lists either for the European or the National elections of the same year.8

“Then [in July 2019] had entered the ballot papers and people who were not part of our tradition, for example they were the ones coming from Kammenos, when the party of Kammenos was dissolved, many ANEL cadres that were MPs, Ministers, etc. were left behind. […] They were coming from a completely different route. Perhaps they were honored by the voters for having stayed here during a critical moment, these things can play a role, it’s not that they brought [voters]from the Right [that voted for them], it would be hard to see it that way.” (SYRIZA interview 1).

In the end, the fact that when snap elections were called for the 7th of July, SYRIZA could hardly expect to win the elections, rather facilitated the process of candidate selection. Most incumbent MPs were included ex officcio in the electoral lists.9 Since incumbency gives a clear advantage for re-election, and an electoral defeat would result in a considerable shrinking of SYRIZA’s parliamentary group, that meant a clear advantage for the incumbents and less safe seats for the newcomers. As Table 1 shows, SYRIZA elected 86 MPs, losing 59 seats from the previous term. Out of the 86 MPs, 60 were returning MPs, with the remaining 26 being elected in Parliament for the first time. Nearly the opposite occurred for ND. Although again, returning MPs occupied ex officcio positions in the lists,10 the party increased its share of seats, from 74 to 158, therefore opening the window of opportunity, not just for returning MPs, but for a whole new cohort of candidates.

SYRIZA therefore did not introduce any changes in its candidate selection process, nor did it initiate any changes in the party structure. The only reform during his governance regarding the ballot structure was a change in the legislation on gender quotas: a new law (L 4604/2019) was adopted a few months earlier that increased gender quotas in the ballots from 30 to 40%. In addition, the obligation of the parties to reach the 40% threshold in their ballots was not statewide, as before, but separately in each constituency. Finally, an older development in party centralization/decentralization that had some impact on the ballot structure was the adoption (in 2014) of open lists and personal preference voting in European Elections (Kakepaki and Karayiannis, 2021). Although not directly related with developments regarding national elections, in a handful of cases non-elected candidates with a “good” personal track record in the preceding European elections of May 2019 secured a seat in the electoral lists of the upcoming national elections, opening their way to Parliament. Therefore, the answer to our first question, which is whether the Great Recession resulted in more PD inside parties in Greece, is a clear no. The only party to adopt such measures pre-crisis (PASOK) electorally collapsed therefore reducing any possible contagion effect.

The Profile of Old and New MPs

The 18th Legislature was full of new faces. One hundred and fourteen new MPs out of 300 entered the Parliament House for the first time. More than half came from ND (62) with the remaining twenty-six belonging to SYRIZA and the rest coming from the other four parties that gained seats in Parliament. The only legislative reform regarding ballot structure, the increase of gender quotas in the ballots from 30 to 40% generated meagre results. The share of women in Parliament in Greece remained low (21.3%), marginally increasing from 2015; the fact that most newcomers came from ND, a party that traditionally scores low in gender terms, highlighted further this imbalance (Table 2), whilst the fact that gender quotas are applied only at the ballot, but may be overturned by the personal preference voting system, makes this reform quite inadequate.

The age distribution reflected past trends, with SYRIZA having more MPs over the age of sixty compared to ND, whilst overall ND MPs have a lower mean age (52.2) than SYRIZA MPs (54.9). The educational profile of all MPs remained high, even more so in ND where nearly nine out of ten of its MPs have a higher education. In terms of their professional characteristics, NDs MPs mostly came from the private sector and the liberal professions. SYRIZA kept its rather more diverse social profile, with a slightly more socially representative sample of MPs. These came not only from liberal and medical profession and the academia but also from clerical and middle level occupational positions. Regarding their social and political profile, ND and SYRIZA MPs vary significantly in two aspects: 22.8% of ND MPs were active in the party’s student branch (DAP, Dimokratiki Ananeotiki Protoporia). DAP, founded in 1975 is a strong and active student’s organization, that during the last decades scores high in all elections in Greek Universities with many prominent ND MPs having served in the student’s branch during their university years. SYRIZA on the contrary, historically has a very low presence in Greek Universities since an official student’s branch with liaisons with the party only appeared in 2015. SYRIZAs much discussed relationship with social movements (Della Porta et al., 2017) remains as a reference in the CVs for several of its MPs, who refer to their participation in a variety of actions. Such references are almost absent from NDs MPs. Finally, traditional paths to election, such as the party, trade unions and local government, remain significant for both parties, with ND having a stronger presence in local government, and SYRIZA in trade unions.

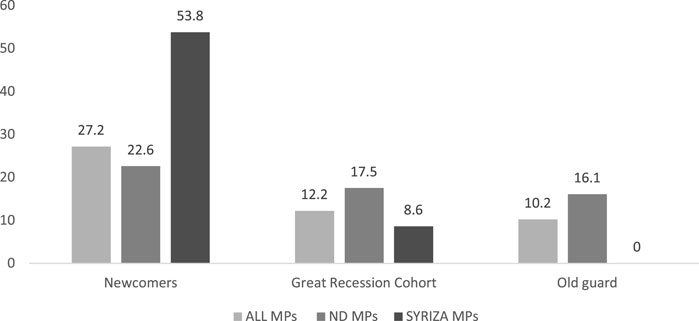

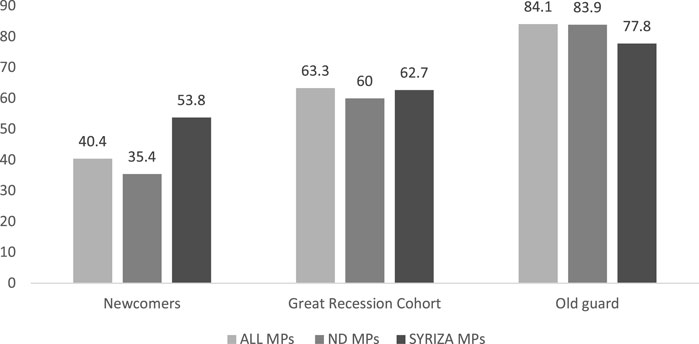

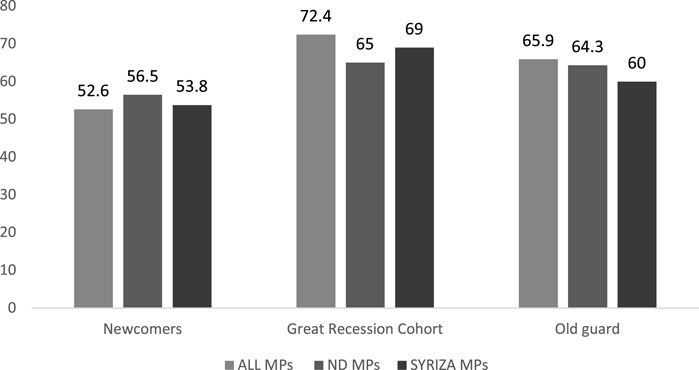

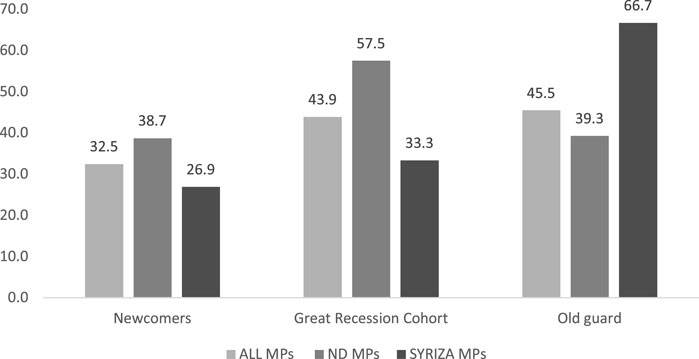

Figures 1–4 break down these trends by cohort in order to fully assess them. Al MPs were divided in three groups based on the time they entered Parliament for the first time. The first group, named “newcomers” includes those that were elected for the first time in 2019. The second group, the “Great Recession” cohort, includes all those MPs that entered Parliament from 2012 until 2015, in the time of the collapse of the old party system. The remaining group includes the ‘Old Guard’ of long-standing MPs that entered Parliament before 2009. If the Great Recession was indeed a force for change, then we expect the newest cohort to be significantly different from the old guard and closer to the Great Recession cohort.

FIGURE 1. Political Expertise* of 18th Legislature MPs by cohort. Source: Socioscope Database (own elaboration). *Defined as posts in political positions at the Executive or Legislative before entering Parliament for the first time (Ministers, general secretaries, political staff in Parliament, political advisers).

FIGURE 2. Party Expertise of 18th Legislature MPs by cohort. Source: Socioscope Database (own elaboration).

FIGURE 3. Ties with Civil Society* of 18th Legislature MPs by cohort. Source: Socioscope Database (own elaboration). *Defined as participation in various cultural, local, sports, professional associations etc.

FIGURE 4. Post in Local Government of 18th Legislature MPs by cohort. Source: Socioscope Database (own elaboration).

Several differences between cohorts and between parties stand out. Firstly, political expertise rises in younger cohorts of MPs, especially amongst those elected with SYRIZA (Figure 1). This trend highlights the fact that politics is more and more regarded as a profession, with previous experience in political positions (in Ministerial positions, as political advisers, or Parliamentary staff) becoming more and more relevant for election. In the case of SYRIZA, it confirms the fact that the few new parliamentary seats were by and large occupied by figures that had served in the Alexis Tsipras cabinets as extra-Parliamentary Ministers since 53.8% of the party’s newly elected MPs had served in such positions. It is reasonable to assume that the ministerial status and the visibility that it secures offers a clear advantage in intra-party competition in the lists.

On the contrary, party expertise, defined as an elected position in the party (Figure 2) sharply declines in the post-recession cohort across all party lines. Although this is something to be expected, given that party positions are often occupied by more experienced Parliamentarians, however it appears that service through the party is becoming less and less relevant for election, especially for ND. Ties with civil society, as expressed through membership in various organizations, are still very relevant but are also on decline (Figure 3). The trend shows that for newcomers, participation in such organizations has dropped, whereas the highest numbers recorder were during the Great Recession. This showcases that during the crisis in Greece there was a window of opportunity for representatives to form stronger ties with civil society, especially for SYRIZA, since 69% of its MPs exhibited such ties, opposed to 53.8% of the newcomers. Finally, ties with the constituency as expressed through previous election in local government have significantly declined (Figure 4) since 32.5% of newcomers have served in local government, compared to 43.9% percent of the Great Recession cohort and 45.5% of the Old Guard. The decline is sharp both for ND and SYRIZA.

Overall, newcomer MPs are more politically experienced (especially from SYRIZA) and at the same time have less ties with the party and with civil society whilst have served less in local government. Social groups such as women and younger people are still underrepresented, whilst the professional and educational capital of MPs remains high. Therefore, the second question that this paper addresses, which is whether parliamentary representatives have become more socially diverse after the Great Recession, is answered with a contingent no. Although the results are mixed, successful candidates resemble more and more “independent” political entrepreneurs with a personal political capital that is not coming from the mass organizations of the past (parties, trade unions) or rely on their professional political experience that makes them suitable for the job.

Conclusion

More than a decade has passed since Greece signed the first MoU in 2010, initiating a long cycle of protest, with the electoral collapse of old actors and the rise of new ones. New faces with barely any experience entered Parliament, whilst veteran Parliamentarians failed to re-elect and disappeared from the political arena. At the same time, citizen’s cynicism and distrust towards politicians prevailed with symptoms such as lower turnout in elections and the vote for parties with a clear aversion for democratic politics. If the answer for such phenomena calls for more democracy, then political actors in Greece did not seem to listen. Mainstream parties, in this case ND, adopted the open method of leader selection, but at the same time made the candidate selection process even more centered around the leader, confirming the argument that an open leader selection bypasses the party and moves towards the personalization and presidentialization of the political system. The party’s sweeping victory resulted in the elections of many new faces; however, the candidate selection mechanisms did not offer anything close to IPD whilst the registry of Executives that partially supplied candidates may in fact have resulted in the diminishing role of middle level elites in the decision-making process, as suggested in the literature (Ignazi, 2020).

Challenger SYRIZA did not in effect contest the candidate selection process, but, especially after its governing experience, highlighted even more the profile of candidates with political experience and expertise, trying therefore to shake off any previous accusations regarding political amateurism. The result of these decisions in the profile of successful candidates is evident. Their social ties are diminished, indicating a weakening connection with social movements, whilst emphasis is now on political competences. What SYRIZA learned from its governing experience was that modern policymaking calls for experts’ knowledge and technocratic skills, therefore those who enter Parliament must possess those skills at the expense of sociodemographic diversity. In the end, we can argue that in SYRIZA there is a dualism between its declared political and ideological profile in the one hand, and its candidate selections mechanism on the other. Although the party emphasized ties with social movements and mass politics—which for a brief time during the crisis were reflected on its candidates’ profiles—its candidate selection process favored professional political skills, moving the party closer to the cartel model (Katz and Mair, 1995). We suggest that this may be the result of an ongoing battle regarding SYRIZA’s primary goal. Although for SYRIZA, the rise to power in 2015 was an external shock that clearly altered the party’s primary goal from policy/ideology to office/vote, the party’s goals are still conflicting. New Democracy appears more consistent with its own ideological profile that is both centered around the party leader and favors the individual attributes of its candidates.

Therefore, the crisis in Greece offered the opportunity structures for the mass renewal of its parliamentary elite and for a somewhat more socially diverse pool of successful candidates, but its effect quickly disappeared. More research is needed to understand the dynamics between candidate selection, internal party structure, and candidates’ social and political profile. If new MPs resemble more independent political entrepreneurs and have less social and political ties, then we must also examine other aspects of the election process; the impact of old and new media in shaping their profile and influencing voters is still an open question, as is “celebrity culture and celebrity candidates” (Arter, 2014) which in an open-list proportional representation system may be gradually replacing traditional routes to the Parliament.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://socioscope.gr/dataset/deputies.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee (REC -EKKE). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1https://socioscope.gr/dataset/deputies. This article was submitted to Elections and Representation, a section of the journal Frontiers in Political Science.

2For the coding process, see here: https://socioscope.gr/content/codebooks/Vouleutes_codebook_FINAL_GR.pdf

3In the European election ANEL got 0.80 percent of the vote, a stark decline from its electoral result in the previous European elections in 2014 (3.46%) and the 4.09% of the last national elections in September 2015.

4https://nd.gr/deltia-tipou/dilosi-toy-proedreyontos-tis-kefe-tis-nd-k-ioanni-tragaki-gia-ta-telika-apotelesmata

5https://nd.gr/deltia-tipou/dilosi-toy-proedreyontos-tis-kefe-tis-neas-dimokratias-k-ioanni-tragaki-4

6There is no official announcement regarding which specific ND candidates included in the lists came from the Registry. In the official presentation of the party lists, prior to the elections, a press release mentioned that 43 out of 419 candidates came from the Registry. How many of them were successful remains unclear, since only 3 out of the 62 newly elected ND MPs state in their CVs the fact that they were scouted from the party’s Registry.

7https://www.syriza.gr/article/id/85255/Al.-Tsipras:-Istoriko-bhma-h-dieyrynsh-toy-SYRIZA.html

8Thanassis Papahristopoulos and Elena Kountoura from ANEL and Spyros Danelis and Thanassis Theoharopoulos from Potami.

9According to personal calculations, out of the 145 MPs elected in the previous parliament, only 11 were not included in the electoral lists, in most cases because they no longer wished to run in the elections.

10The vast majority of the 75 ND MPs of the previous Parliament were included in the lists since only six were left out. Out of those not included in the lists, four had been elected in other positions in the preceding European (Evangelos Meimarakis and Anna-Michel Asimakopoulou) and Regional/Municipal elections (Kostas Koukodimos and Giorgos Kasapidis). From the remaining two, one had publicly disagreed with ND, was expelled from the parliamentary group in 2017 and moved to SYRIZA, whilst the other had passed away during the previous term. Of those included in the lists only five were not re-elected.

References

Alexandre-Collier, A., Goujon, A., and Gourgues, G. (Editors) (2020). Innovations, Reinvented Politics and Representative Democracy. 1st ed. (London and New York, NY: Routledge). doi:10.4324/9780429026300

Alexakis, E. (2020). “The Conservatives,” in The Oxford Handbook of Modern Green Politics. Editors K. Featherstone,, and D. A. Sotiropoulos (Oxford University Press), 256–268. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198825104.013.16

Arter, D. (2014). Clowns, 'Alluring Ducks' and 'Miss Finland 2009': the Value of 'Celebrity Candidates' in an Open-List Pr Voting System. Representation 504, 453–470. doi:10.1080/00344893.2014.982693

Borz, G., and Janda, K. (2020). Contemporary Trends in Party Organization: Revisiting Intra-party Democracy. Party Polit. 26 (1), 3–8. doi:10.1177/1354068818754605

Bosco, A., and Verney, S. (2016). From Electoral Epidemic to Government Epidemic: The Next Level of the Crisis in Southern Europe. South Eur. Soc. Polit. 21 (4), 383–406. doi:10.1080/13608746.2017.1303866

Coller, X., Santana, A., and Jaime, A. M. (2014). Problemas y soluciones para la construcción de bases de datos de políticos. Revista Española de Ciencia Política 34, 169–198.

Coller, X., Cordero, G., and Jaime Castillo, A. (Editors) (2018). The Selection of Politicians in Times of Crisis. London and New York: Routledge.

Cordero, G., and Coller, X. (2018). Democratizing Candidate Selection. New Methods, Old Receipts? Palgrave Macmillan.

Cordero, G., Coller, X., and Jaime-Castillo, A. M. (2018). “The Effects of the Great Recession on Candidate Selection in America and Europe,” in The Selection of Politicians in Times of Crisis. Editors X. Coller, G. Cordero, and A. M. Jaime-Castillo (Cham: Routledge), 262–277. doi:10.4324/9781315179575-16

Cross, W., and Pillet, J. B. (2015). The Politics of Party Leadership. A Cross-National Perspective. Oxford University Press.

Della Porta, D., Fernández, J., Kouki, H., and Mosca, L. (2017). Movement Parties against Austerity. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Detterbeck, K. (2018). “Political Crisis and its Effect on Candidate Selection,” in The Selection of Politicians in Times of Crisis. Editors X. Coller, G. Cordero, and A. M. Jaime-Castillo (London and New York, NY: Routledge), 19–30. doi:10.4324/9781315179575-2

Eleftheriou, K. P. (2019). “Syriza from Opposition to Government. Organizational Strategy in the Shadow of Synaspismos,” in Syriza: A Party on the Move. From Protest to Governance. Editor Y. Balampanidis (Themelio, 143–173.

Eleftheriou, K. P., and Tassis, C. (2019). “Intraparty Policy and PASOK’s Strategy: PASOK’s ‘Participatory’ Attempt (2004-2009),” in PASOK 1974 – 2018. Political Organization, Ideological Shifts, Governmental Policies. Editors V. Assimakopoulos, and C. Tassis (Athens: Gutenberg), 467–524.

Gauja, A. (2017). Party Reform: The Causes, Challenges, and Consequences of Organizational Change. Oxford University Press.

Gerbaudo, P. (2021). Are Digital Parties More Democratic Than Traditional Parties? Evaluating Podemos and Movimento 5 Stelle's Online Decision-Making Platforms. Party Polit. 27 (4), 730–742. doi:10.1177/1354068819884878

Greene, J. C., Caracelli, V. J., and Graham, W. F. (1989). Toward a Conceptual Framework for Mixed-Method Evaluation Designs. Educ. Eval. Pol. Anal. 11 (3), 255–274. doi:10.3102/01623737011003255

Harmel, R., and Janda, K. (1994). An Integrated Theory of Party Goals and Party Change. J. Theor. Polit. 6 (3), 259–287. doi:10.1177/0951692894006003001

Hazan, R. Y., and Rahat, G. (2010). Democracy within Parties: Candidate Selection Methods and Their Political Consequences. Oxford University Press.

Hobolt, S. B., and Tilley, J. (2016). Fleeing the centre: the Rise of Challenger Parties in the Aftermath of the Euro Crisis. West Eur. Polit. 39, 971–991. doi:10.1080/01402382.2016.1181871

Ignazi, P. (2021). The Failure of Mainstream Parties and the Impact of New Challenger Parties in France, Italy and Spain. Riv. Ital. Sci. Polit. 51 (1), 100–116. doi:10.1017/ipo.2020.26

Ignazi, P. (2020). The Four Knights of Intra-party Democracy: A rescue for Party Delegitimation. Party Polit. 26 (1), 9–20. doi:10.1177/1354068818754599

Kakepaki, M. (2019). “Between the Party and the Market: The New Democracy Parliamentary Group before and after the 7th of July 2019 Elections,” in The Political Portrait Of Greece. Issues And Challenges [The Political Portrait of Greece. Risks and Challenges]. Editor C. Varouxi (IEEE).

Kakepaki, M., and Karayiannis, Y. (2021). Ticket to Brussels. One-Way or Return? Profiles and Typology of Greek MEPs, 1981-2019. Greek Rev. Soc. Res. 157, 157–181. doi:10.12681/grsr.27621

Kakepaki, M., Kountouri, F., Verzichelli, L., and Coller, X. (2018). “The Sociopolitical Profile of Parliamentary Representatives in Greece, Italy and Spain before and after the “Eurocrisis”: A Comparative Empirical Assessment,” in Democratizing Candidate Selection: New Methods, Od Receipts Editors G. Cordero, and X. Coller (Springer International Publishing), 175–200.

Kakepaki, M. (2018). “New Actors, Old Practices?: Candidate Selection and Recruitment Patterns in Greece,” in The Selection of Politicians in Times of Crisis. Editors X. Coller, G. Cordero, and A. Jaime –Castillo (London and New York, NY: Routledge), 98–114.

Karoulas, G. (2019). “Political Tradition and Political Parties in the Third Greek Republic: Emerging, Reproduction and Evolution of Nepotism in the Period 1989-2012,” in From Metapolitefsi To Crisis: Aspects And Prospects Of the Third Greek Republic. Hellenic Political Science Association. Editors J. Y. KaragiannisKarayiannis, and K. Kanellopoulos, 46–70.

Katsikas, D., Sotiropoulos, D. A., and Zafeiropoulou, M. (Editors) (2018). Socio-economic Fragmentation and Exclusion in Greece under the Crisis (Palgrave Macmillan).

Katz, R. S., and Mair, P. (Editors) (1994). How Parties Organize: Change and Adaptation in Party Organizations in Western Democracies (London: SAGE Publications Ltd). doi:10.4135/9781446250570

Katz, R. S., and Mair, P. (1995). Changing Models of Party Organization and Party Democracy: The Emergence of the Cartel Party. Party Polit. 1 (1), 5–28. doi:10.1177/1354068895001001001

Koltsida, D. (2019). “The Multiple Facets of Left’s “First Time”: SYRIZA’s Political Personnel (2012 -2018),” in SYRIZA. A Party on the Move. From Protest to Governance. Editor Y. Balampanidis (Themelio, 174–201.

Kosmopoulos, D. (2021). “Impact of Intra-party Democracy on Patterns of Political Career within the Pan-Hellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK) in Greece, 2004–2009,” in New Paths for Selecting Political Elites. Investigating the Impact of Inclusive Candidate and Party Leader Selection Methods. Editors G. Sandri, and A. Seddone (London and New York, NY: Routledge), 101–117.

Kountouri, F. (2018). Patterns of Renewal and Continuity in Parliamentary Elites. The Greek MPs from 1996 to 2015. J. Legislative Stud. 24 (4), 568–586.

Marino, B., Martocchia Diodati, N., and Verzichelli, L. (2021). “Candidate Selection, Personalization of Politics, and Political Careers Insights from Italy (2006–2016),” in New Paths for Selecting Political Elites. Investigating the Impact of Inclusive Candidate and Party Leader Selection Methods. Editors G. Sandri, and A. Seddone (London and New York, NY: Routledge), 82–105.

Morlino, L., and Raniolo, F. (2017). The Impact of the Economic Crisis on South European Democracies. Palgrave Macmillan.

New Democracy (2018). Statute of New Democracy. Available at: https://nd.gr/katastatiko.

Pappas, T., and Dinas, E. (2006). From Opposition to Power: Greek Conservatism Reinvented. South Eur. Soc. Polit. 11 (3-4), 477–495.

Pappas, T. S. (2020). The Pushback against Populism: The Rise and Fall of Greece's New Illiberalism. J. Democracy 31 (2), 54–68. doi:10.1353/jod.2020.0036

Perez-Nievas, S., Parades, M., Cordero, G., and Coller, X. (2021). “Democratic, yet Representative? Selecting MPs in a Multilevel Polity,” in Politicians in Hard Times. Editors X. Coller, and L. Sanchez-Ferrez (Palgrave-Macmillan), 109–129.

Poguntke, T., Scarrow, S. E., Webb, P. D., Allern, E. H., Aylott, N., van Biezen, I., et al. (2016). Party Rules, Party Resources and the Politics of Parliamentary Democracies: How Parties Organize in the 21st century. Party Polit. 22 (6), 661–678. doi:10.1177/1354068816662493

Rahat, G., and Kenig, O. (2018). From Party Politics to Personalized Politics? Party Change and Political Personalization in Democracies. ECPR Oxford University Press.

Rori, L. (2020). The 2019 Greek parliamentary election: retour à la normale. West Eur. Polit. 43 (4), 1023–1037. doi:10.1080/01402382.2019.1696608

Sandri, G., and Seddone, A. (2015). Party Primaries in Comparative Perspective. 1st ed. London and New York, NY: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315599595

Sandri, G., and Seddone, A. (Editors) (2021). “New Paths for Selecting Political Elites,” Investigating the Impact of Inclusive Candidate and Party Leader Selection Methods (London and New York, NY: Routledge).

Sandri, G., Seddone, A., and Venturino, F. (Editors) (2015). Party Primaries in Comparative Perspective Surrey and Burlington: Ashgate.

Scarrow, S. E., Webb, P. D., and Poguntke, T. (Editors) (2017). Organizing Political Parties. Representation, Participation, and Power (Oxford University Press).

Seddone, A., and Sandri, G. (2021). “Political Elites and Party Primaries,” in New Paths for Selecting Political Elites. Investigating the Impact of Inclusive Candidate and Party Leader Selection Methods. Editors G. Sandri, and A. Seddone (London and New York, NY: Routledge), 228–243.

Skoulariki, A. (2021). Political Polarisation in Greece: The Prespa Agreement, Left/right Antagonism and the Nationalism/populist Nexus. South Eur. Soc. Polit. doi:10.1080/13608746.2020.1932020

Standard Eurobarometer, (2021). Public Opinion in the European Union. Availableat: https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2532.

SYRIZA (2020). An Account 2012-2019. Available at: https://www.syriza.gr/article/id/94170/Apologismos-SYRIZA-2012-2019.html.

SYRIZA (2013). Statute of SYRIZA. Available at: https://www.syriza.gr/page/katastatiko.html.

Teperoglou, E., Andreadis, I., and Chadjipadelis, T. (2020). “The Study of Political Representation in Greece: Towards New Patterns Following the Economic Crisis” in Political Representation in Southern Europe and Latin America: Before and after the Great Recession and the Commodity Crisis. Editors A. Freire, M. Barragán, X. Coller, M. Lisi, and E. Tsatsanis (London and New York, NY: Routledge), 34–49.

Teperoglou, E., and Tsatsanis, E. (2014). Dealignment, De-legitimation and the Implosion of the Two-Party System in Greece: The Earthquake Election of 6 May 2012. J. Elections, Public Opin. Parties 24 (2), 222–242.

Tsatsanis, E., and Teperoglou, E. (2019). “Greece’s Coalition Governments. Power Sharing in a Majoritarian Democracy,” in Coalition Government as a Reflection of a Nation’s Politics and Society. A Comparative Study of Parliamentary Parties and Cabinets in 12 Countries. Editor M. Evans (London and New York, NY: Routledge), 224–243.

Tsatsanis, E., Teperoglou, E., and Seriatos, A. (2020). Two-partyism Reloaded: Polarisation, Negative Partisanship, and the Return of the Left-Right Divide in the Greek Elections of 2019. South European Society and Politics. doi:10.1080/13608746.2020.1855798

Tsatsanis, E. (2018). “The swift Unravelling: Party System Change and Deinstitutionalization in Greece during the Crisis,” in Party System Change, the European Crisis and the State of Democracy. Editor M. Lisi (London: Routledge), 115–136.

Tsirbas, Y. (2020). “The Party System,” in The Oxford Handbook of Modern Greek Politics. Editors K. Featherstone, and D. A. Sotiropoulos (Oxford University Press), 219–238.

Vernardakis, C. (2011). Political Parties, Elections and Party System: Transformations of Political Representation 1990-2010. Sakkoulas.

Verney, S. (2014). ‘Broken and Can't BeFixed’: The Impact of the Economic Crisis on the Greek Party System., The Int. Spectator 49 (1), 18–35. doi:10.1080/03932729.2014.877222

Keywords: candidate selection, Greece, elite renewal, members of parliament, intra-party democracy

Citation: Kakepaki M (2022) Changes in Candidate Selection and the Sociodemographic Profile of Greek MPs. Evidence From the 2019 General Elections. Front. Polit. Sci. 3:777298. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.777298

Received: 15 September 2021; Accepted: 21 December 2021;

Published: 15 February 2022.

Edited by:

Guillermo Cordero, Autonomous University of Madrid, SpainReviewed by:

Sorina Soare, University of Florence, ItalyStefano Rombi, Università degli Studi di Cagliari, Italy

Copyright © 2022 Kakepaki. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Manina Kakepaki, bWtha2VwYWtpQGVra2UuZ3I=

Manina Kakepaki

Manina Kakepaki