- UCD Centre for Humanitarian Action, University College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland

The localisation agenda has found a new impetus following the COVID 19 pandemic. International NGOs increasingly accept the inevitability of localisation and few would argue against its conceptual benefits. However, the challenge to operationalise localisation exposes fundamental differences in the INGO community. While all humanitarian INGOs share a common set of humanitarian principles, these principles sit alongside other principles and values that shape the fundamental strategic management processes of these organisations. This study of Irish humanitarian NGOs shows that organisations are at different stages in fully institutionalising localisation. Most of these organisations depend on a common resource pool that in turn has considerable influence over the speed of localisation. The big messages emanating from this study are that localisation is not without risk which needs to be shared by all stakeholders and many organisations will need to augment their strategic management processes to fully embrace localisation.

Introduction

While generally credited as an outcome of the 2016 World Humanitarian Summit (WHS), it could be argued that the conceptual basis for the localisation agenda is rooted in the humanitarian principles and most codes and standards that serve to guide humanitarian action (Barbelet, 2018). The contemporary international humanitarian system, generally associated with the adoption of UN resolution 46/182 by the UN General Assembly, has consistently valued local engagement. This is evidenced across the full range of humanitarian stakeholder’s initiatives such as: the Code of Conduct of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement and NGOs (1994); the Principles of Good Humanitarian Donorship (2003); the Principles of Partnership (2007); the Transformative Agenda (2010); and the Core Humanitarian Standard (Roepstorff, 2019).

The consultative process that preceded the WHS provided an unprecedented opportunity for the international humanitarian community to reflect on global humanitarian action. This global consultative process included eight regional consultations held in 2014 and 2015; constituent consultations with youth, women, private sector, disabilities representative; and online submissions accepted between May 2014 and July 2015. The synthesis report of this extensive consultation suggests:

“One call has arisen more than any other in the World Humanitarian Summit consultations: recognise that affected people are the central actors in their own survival and recovery and put them at the heart of humanitarian action. This requires a fundamental change in the humanitarian enterprise, from one driven by the impulses of charity to one driven by the imperative of solidarity” (World Humanitarian Summit Secretariat, 2015).

The World Humanitarian Summit secretariat proceeded to provide five major areas of action to shape a changed direction in future humanitarian action, namely: dignity; safety; resilience; partnership; and finance. According to Stephen O’ Brien the Emergency Relief Coordinator at the time of the WHS, the consultations called for a paradigm shift away from a top-down, supply driven system towards a model that meaningfully engages with the people it intends to serve, and empowers them to have a great voice and choice (ibid).

In essence, this proposed paradigm shift is at the heart of the “localisation agenda”. It has exercised the entire humanitarian community over the past years, (re)energised existing “localising initiatives” as well as prompting a raft of new initiatives, including:

• The UN’s New Way of Working (2017);

• A multitude of NGO initiatives such as Principles of Partnership (2007), the Charter for Change (2015), Pathway to Localisation (2019), the Start Network’s Framework for Localisation (2017);

• It has captured donor attention primarily through the Grand Bargain (2016); and

• It has generated much rich debate in academia, humanitarian networks and think tanks.

However, despite the wealth of literature, reforms and consultations, the transformations envisaged have been slow to materialise.

This study sets out to determine the challenges for the Irish INGO community to operationalise localisation. It was initiated by UCD’s Centre for Humanitarian Action to inform an education module at the master’s level and provide existing and would-be humanitarian professionals with the competences to contribute to the localisation agenda. Based on the premise that most humanitarian stakeholders acknowledge the need for further localisation, the study sought to ascertain “How Irish International NGOs are embracing the Localisation Agenda?” More specifically it sought to answer the following questions:

• How is the concept “localisation” understood?

• What characteristics dominate Irish humanitarian INGO community and its understanding of localisation?

• What are the real and perceived challenges to support locally led humanitarian action?

• How will COVID 19 impact the localisation agenda?

Research Design

The data was collected during the COVID 19 pandemic lockdown - May 15th to June 19th, 2020. It was prompted by the growth in literature, policies and localisation initiatives that emerged in the global lockdown. Frustrated with the challenge to find an agreed definition of “localisation”, the research turned to analyse the localisation concept informed a methodology linked with both the business and nursing sciences (Nuopponen, 2010). Nuopponen (2010) explains how a purpose of concept analysis in the business discipline is to interpret meanings and definitions of concepts presented in written, textual form considering a theoretical perspective. She draws on the work of Nasi (1980), who suggests that concept analysis combines elements of analytical and synthetic reasoning to give meaning to a concept within a discipline. This involves four interwoven phases: creating a knowledge foundation from gathering information from other disciplines in related concepts; external analysis–distinguishing the concept from superordinate concepts and related concepts within the discipline; internal analysis–analysis of different views of the concept within the discipline; and lastly, forming conclusions by providing solution alternatives, reasoning, and motivations for the new concept.

This study analyses literature from a range of aid stakeholders (governmental, non-governmental and academia) on localisation to inform the research process with Irish humanitarian NGOs. Thirteen NGOs that are full members of the DOCHAS1 Humanitarian Action Working Group (HAWG) and that have an overseas presence were invited to participate. Key informants from these NGOs were selected based on their roles and experience with localisation. Mostly senior management within the organisations, such as executive directors and heads of programmes were to take part in an online survey questionnaire. Twelve out of a possible thirteen NGOs (92%) responded. Table 1 presents the response rate and the position of the respondent within the participating NGOs. The results of the survey were shared with all participants and respondents were afforded the opportunity to seek clarifications and address any irregularities in the draft report.

Understanding Localisation

There are many and varied attempts to define localisation in the literature, including: “a process of recognising, respecting and strengthening the leadership by local authorities and the capacity of local civil society in humanitarian action, in order to better address the needs of affected populations and to prepare national actors for future humanitarian responses” (Roepstorff, 2019, p. 2); “a collective process by the different stakeholders of the humanitarian system (donors, United Nations agencies, NGOs) which aim to return local actors (local authorities or civil society) to the centre of the response with greater, more central role” (Geoffroy and Grunewald, 2017, p. 11, p. 11); and even the much cited slogan from the UN Secretary General advocating for humanitarian action to be “as local as possible, as international as necessary” (UN OCHA, 2016).

Barbelet (2018) questions the use of the term localisation on the basis that it reinforces the central position held by the international humanitarian system. While there is no consensus on a definition of localisation, the literature indicates certain similarities across existing definitions that suggest a need to respect, recognise, rebalance, recalibrate, reinforce, or return some type of ownership or place to local and national actors. Barbelet (2018) proceeds to offer alternative terms such as “local humanitarian action”, “locally-led humanitarian action” and “local humanitarian leadership”. In essence, one might be excused for understanding the localisation challenge is to seek complementarity between two systems: the international humanitarian system; and that of the affected populations at all societal levels national and local.

Barakat et al (2020) positions localisation relative to superordinate concepts in aid discourse when they analyse localisation across the triple nexus–humanitarian, development, and peace. They suggest that the conceptual origins of localisation are more easily associated with the superordinate concept “resilience”, which predated the WHS and, they like Chandler (2014) called for working with and upon the capacities, capabilities, processes, and practices already “to hand” rather than the external provision of policies or programmes. This thinking is mirrored in Hilhorst et al. (2019) views that governance structures of INGOs accord central importance or power to international humanitarian agencies at headquarter level although it is now being paralleled by “resilience humanitarianism” that focuses, among other things, on including national actors in humanitarian governance. Ontologically, resilience thinking suggests a shift from (neo)liberal thinking governed by interventionist regulatory cause-effect policies and practices to an ontology of emergent complexity that respects that life is complex, relational, embedded, and contextual (Chandler 2014). This shift in thinking invariably requires a respect for national disparities in their understanding of “local” and the societal political, economic, social and cultural institutions in disaster affected countries. Barbelet (2018) identifies many of the potential advantages and capacities that local actors bring to the humanitarian effort, including: understanding the local context, gaining acceptance by local communities, better value for money/cheaper, more willing and able to access remote and often dangerous areas, more accountable to local populations, and open to adaptable and flexible programming. On the flip side, her research suggests that the international community have perceived advantages of being more professional and less political than local actors.

An internal analysis of the localisation concept and/or its associated attributes shows many similarities. Donor governments that are signatories to the Grand Bargain typified the localisation agenda as increased local funding; strengthening local capacities, enhanced local coordination, and strengthened local partnerships. The START Network, a consortium of INGOs from the global North, added to these four attributes and included: enhanced local visibility and communication of local voices together with strengthened participation. The Charter4Change, a global network of INGOs from both the global North and South, identified eight attributes of localisation. These eight attributes mirror Grand Bargain’s four attributes but emphasise: increased level of funding to national and local actors and a call for transparency in resources transfers, that capacity strengthening include robust organisational support and a commitment to ensure that all efforts are made to prevent activities that may undermine the capacities of national and local organisations; that future partnership arrangements be governed by the principles of partnership and in so doing address subcontracting traditions; and the coming together of the international and national/local should be evidenced in dealing with donors, the public and all other communication channels.

Academia has also contributed to localisation attributes. Roepstorff (2019) combines elements of the Grand Bargain, START Network and the C4C to suggest that key components of localisation include: partnerships, local funding, capacity strengthening, coordination, recruitment and visibility. University College Dublin’s Centre for Humanitarian Action has identified capacity strengthening, engagement (participation and partnership), accountability and transparency, trust building, and empowerment/agency as core attributes of the evolving localisation concept. However, as academia comes to grips with some normative understanding of what localisation should exemplify, the literature is increasingly looking to impediments that are at best slowing progress or at worst preventing its realisation. Van Brabant et al (2017) demonstrates the core problems with the current international humanitarian system and posits two extreme interpretations of localisation depending on the emphasis of the core problem. The first, a decentralisation interpretation relates to those organisations that view “centralisation” as the core problem. It proposes the decentralisation of strategic, operational and financial operations in a bid to enhance cost effectiveness and shift power from the headquarters to national or even local organisations. The second interpretation relates to the perceived “domineering” traditions of the international community and calls for a transformational interpretation that will result in stronger national capacity and leadership. In such a scenario, strategic, operational and financial decisions are made by national actors (governmental and non-governmental) with the risk of emphasis on the political economy over the humanitarian economy. Most academic humanitarian literature warn of the excesses of such a “localisation” given its potential to undermine principled humanitarian action and suggest the need for complementarity between the international and local or what Barakat and Milton (2020) suggests as multi-scalar response.

The extent and rate at which any humanitarian organisations localise their operations are influenced by many factors and few more so than donor requirements. While the Grand Bargain is central to the localisation agenda, many of the signatories continue to require levels of oversight and accountability to eliminate risk of fraud or mismanagement that virtually disallows anything other than domination by international actors. In many cases donor governments, that are also signatories to the Grand Bargain, are bound by legislation to only work through humanitarian organisations that are registered in that country or “connected” with a registered organisation. Other obstacles include the counter-terror legislation, which creates significant accountability issues for international organisations and renders it impossible to engage directly with local aid providers from societies where there are known terrorist groups. Lastly, there is a perceived notion that the public may want to see its contribution to humanitarian aid channelled through national organisations and/or organisations registered nationally.

Localisation for Irish Humanitarian INGOs

Irish humanitarian INGOs are a heterogenous grouping that differ considerably in terms of organisational mandate; organisational structure and global reach; scale of operations; sources of funding; as well as perspective on localisation. All Irish humanitarian INGOs, except for Médecins San Frontiers, are classified as dual mandated organisations i.e., having both development and humanitarian briefs. Half of the INGOs have their headquarters in Ireland and the remaining INGOs have headquarters in the United Kingdom, South Africa, Kenya and Switzerland.

While all Irish humanitarian INGOs subscribe to the humanitarian principles, these principles sit alongside other values and principles that give each INGO its unique identity in Ireland. At the risk of over-simplifying the disparities in the Irish humanitarian community and building on Stoddard’s classification of humanitarian INGOs–Dunantist, Wilsonian and Religious - it is fair to say that those INGOs with headquarters in Ireland have strong roots in the missionary traditions of the Catholic Church. The origins of Trocaire, Concern Worldwide, Vita, and Misean Cara can be traced back to the Catholic missions and while Trocaire and Misean Cara retain strong religious affiliations, Concern Worldwide and Vita have become largely secularised with Concern Worldwide adopting Dunantist traditions and Vita assuming more developmental traditions in a limited geographic space linked with the Horn of Africa. While the origins of GOAL and Self Help Africa have limited direct link with the missions, their origins have undoubted been impacted by religious charitable influences in Ireland with GOAL focusing on humanitarian action and reaching out to a broad constituency through sports personalities while Self Help Africa has its origins in rural society with a definite developmental bias.

Ireland’s close relationship with the United Kingdom and in particular Northern Ireland provided the opportunity for both Christian Aid and Oxfam to expand to the Republic of Ireland. Christian Aid has retained is strong ties with Christian traditions while Oxfam Ireland is part of the bigger Oxfam confederation with a global reach in both humanitarian and development contexts. In the 1990s, following Irelands economic fortunes, largely associated with the Celtic Tiger era, large INGOs increasingly located in Ireland, including: Plan International Ireland, World Vision Ireland, Action Aid and Médecins Sans Frontiers. All these organisations have the support of larger parent organisations and, while incorporated in Ireland, they are bound by the governance and management policies, values, and protocols of their parent organisations.

A cursory analysis of organisational value systems can provide a rationale for Irish humanitarian INGO’s disparate perspectives on localisation. A review of the strategic plans from two organisations, one faith-based with undoubted religious affiliations and the other that aligns with a Dunantist perspective results in the following varied value systems. The faith-based organisation values: solidarity with the most vulnerable, courage, participation, perseverance, and accountability. The organisation with Dunantist association values: access to the most vulnerable, equality, efficacy, courage, committed, and innovation. While both organisations acknowledge the importance of localisation in their future strategies, the faith-based organisation is eminently more committed to localisation in its policies, practices and future funding streams. The organisation with Dunantist tendencies is more tempered in its approach to localisation on the premise that not all humanitarian contexts lend themselves to fully align with local/national stakeholders.

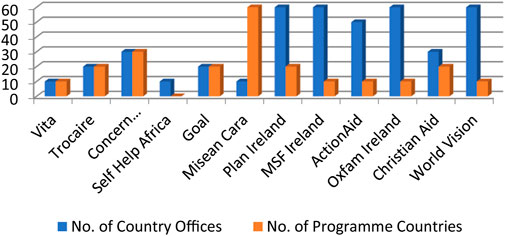

Figure 1 presents the global reach of Irish Humanitarian INGOs. With the notable exception of Misean Cara2, Irish INGOs operate in a limited number of countries globally. The tradition has been for those INGOs that are members of a larger NGO family to focus programmes in areas where Ireland has a strong aid tradition.

The Irish Humanitarian INGO sector is a significant employer in Ireland with five out of the twelve organisations (42%) indicating they employ more than 60 staff. Concern Worldwide, Trocaire and GOAL are the largest employers followed by Oxfam, Self Help Africa and Christian Aid. The remaining INGOs have between ten and thirty employees working in Ireland.

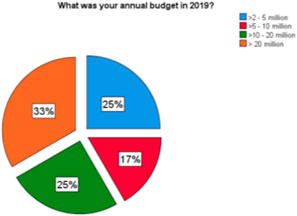

There is an equally huge variation in the annual budgets of Irish INGOs as presented in Figure 2. One-third of the respondents reported that they managed budgets in excess of €20 million in 2019 with one of these organisations approaching an annual budget of almost €200 million. At the other extreme, three organisations managed budget of less than €5 million. Two organisations reported budgets of €5–€10 million and the remaining three organisations indicated they managed budgets of €10–€20 million.

Government funding is the main source of funding for nine of the organisations studied with one organisation indicating that 100% of its funding comes from government sources. At the other extreme, two organisations indicated they received no funding from government sources in 2019. A further analysis shows: five organisations received more than two-thirds (67%) of their 2019 annual funding from government sources; three organisations received between one-third and two-thirds (33–67%) of their funding from government sources; and the remaining three organisations indicated that less than one-third of their funding came from governments.

Investigating other sources of funding, the study asked respondents how much of their private funding comes from 1) individual charitable donations and 2) companies or corporations. Ten out of the eleven respondents indicated that private funding was “a main sources of funding” in 2019. Most of these organisations proceeded to explain that it is required to “match” government funding while with one organisation indicated that it relied totally on private funding. A further analysis of the private funding to Irish aid organisations suggests that more than half (6) of the organisations indicated that less than 33% of their funding comes from individual charitable donations. One organisation relied totally on individual charitable donations in 2019.

Global Localisation Effort Among Irish INGOs

A third of Irish INGOs have a policy on localisation. These organisations have diverse definitions of localisation as presented below:

• “Aid localisation is a collective process involving different stakeholders that aims to return local actors, whether civil society organisations or local public institutions, to the centre of the humanitarian system with a greater role in humanitarian response”.

• “The term localisation, as used in the humanitarian sector, refers to the process of better engaging local and national actors in all phases of humanitarian action, including greater support for locally-led action”.

• “Shifting power to local women’s organisations”.

• “A transformational process to recognise, respect, and invest in local and national humanitarian and leadership capacities to better meet the needs of crisis-affected communities”.

In recognising that the absence of a policy cannot assume a lack of commitment to localisation, respondents were asked to share their organisation’s understanding of localisation. Seven responses were provided as documented below:

• “Country offices must have a local national as country director and country offices have high levels of autonomy”.

• “Increased engagement of local and national NGOs in design and delivery of programmes; Increased funding-potentially direct funding from donors. Increased engagement/visibility in co-ordination mechanisms”.

• “Operational decision-making and resources are located as close as possible to the communities or populations we seek to assist”.

• “… our decision-making with regard to how our funding is spent is based on the principle of subsidiarity”.

• “Working through local partners e.g., government, civil society, academia, etc”.

• “We are developing a partnership strategy which will align with the organisation’s ambition for partnership, as articulated in organisation’s strategic plan”; and

• “Local and national humanitarian actors are increasingly empowered to take a greater role in the leadership, coordination and delivery of humanitarian preparedness and response in their countries”.

Three out of the twelve participating organisations indicated that they are signatories to the Charter for Change3 (C4C).

Attributes of Localisation in Irish NGO’s Understanding of the Concept

The respondents ranked eight attributes of localisation that were sourced from literature. They were also given the choice to add additional attributes particular to their own organisation. The results allow a comparison of the relative importance of the attributes, but no quantification can be ascribed to these findings. The findings suggest the following ranking:

1. Building local trust;

2. Local leadership;

3. Local participation;

4. Partnership with local organisations;

5. Local capacity strengthening;

6. Locally managed funding;

7. Coordination and complementarity with local organisations; and

8. Strengthening local policy, influence, and visibility.

Other attributes of importance cited by participating organisations, included: Community acceptance; Resilience; Subsidiarity; and Transparency/Accountability.

Drawing on recent literature, the respondents were asked to indicate their level of agreement or disagreement with several statements relating to the potential value and need for localisation.

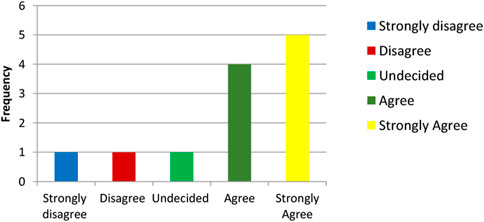

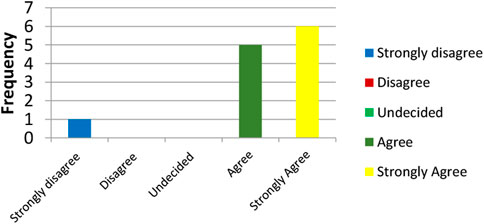

Strategic Decision-Making Needs to be Brought Closer to the Crisis Zone (n = 12)

Most Irish INGOs are committed to the “governance” ideals of localisation with nine out of the twelve respondents agreeing with the statement that strategic decision-making needs to be brought closer to the crisis zone as presented in Figure 3.

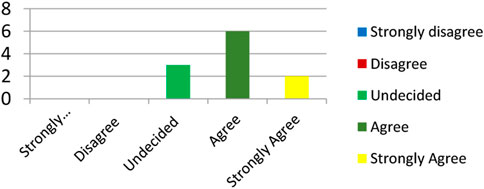

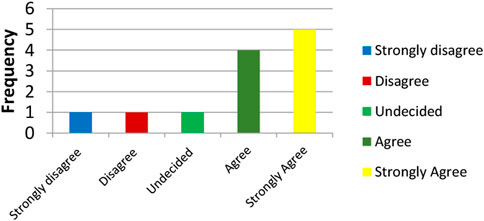

To Capitalise on Cheaper Local Resources and Reduce the Role of “Fund-Intermediaries”, Localisation Increases Cost-Effectiveness (n = 12)

While seven out of the twelve Irish NGOs agree with the notion that localisation will potentially result in efficiencies in the longer-term, the responses on the cost-effectiveness of localisation in humanitarian response are more nuanced as presented in Figure 4.

FIGURE 4. To capitalise on cheaper local resources and reduce the role of “fund-intermediaries”, localisation increases cost effectiveness.

International Actors Should Invest in the Capacities and Preparedness of Populations-at-Risk and of Local Responders Together with Strengthening their Institutional Sustainability (n = 12)

The significant majority of Irish NGOs (11 out of 12) agree or strongly agree with the statement that international actors should invest in the capacities of local responders together with strengthening their institutional sustainability as presented in Figure 5.

FIGURE 5. International actors should invest in the capacities and preparedness of populations at risk and of local responders together with strengthening their institutional sustainability.

International Agencies Should Provide National Actors with More Direct and Better-Quality Financing, and to Create Incentives for Collaborative Action (n = 12)

Irish INGOs are committed to changes in funding aligned with the localisation concept. A majority (9 out of 12) of Irish NGOs agree with the statement that international agencies should provide national actors with more direct and better-quality financing and to create incentives for collaborative action as presented in Figure 6.

FIGURE 6. International agencies should provide national actors with more direct and better quality financing, and to create incentives for collaborative action.

Localisation will Enhance Access to Local Organisations/Vulnerable Communities (n = 11)

Irish humanitarian INGOs are more cautious to the notion that localisation will potentially enhance access to local vulnerable populations. Figure 7 below indicates that 8 out of 11 respondents (73%) agreed with the statement that localisation will lead to enhanced access of international NGOs to local organisations and vulnerable communities.

Governing and Managing the Localisation of Humanitarian Action

All Irish humanitarian INGOs have strategic management plans to guide organisational operations. Most of the respondents actively engaged (10 of the respondents) in the development of the strategic management plans for their respective organisation. The nature of this engagement varied from: led the process developing the plan (2); member of the team responsible for developing the strategic plan (6); and led the development of components of the plan (2). Respondents were asked to indicate the level of country/programme official’s engagement in formulating strategic plans for their organisations. Eight of the twelve respondents indicated the active involvement of country programme officials using a range of methodologies, as presented below:

• A survey was administered to all programme offices by an independent agency to feed into the strategic plan;

• The Global federation employed surveys and questionnaires in consultations with country programmes;

• International federation involved a lot of consultation with country offices;

• Facilitated strategic planning meetings during a 6-month period with participants (project teams, member organisations, staff, board, etc.) across 10 countries;

• Country and regional level consultations with partners as well as entities with whom we have no formal partnership agreements. Final iterations of the plan were the product of global workshops of diverse stakeholders including “unusual suspects”;

• Engagement with country offices and key partners;

• In-country discussions by senior teams which also involved engaging with local partners; and

• A programme evaluation conducted with partners and communities. Country teams also consulted with partners on the direction of programming.

The vast majority of Irish humanitarian INGOs suggest that no significant change is required in core elements of their organisations to operationalise localisation. Invariably, the respondents view the localisation agenda as consistent with the related concept “partnership”, which is well embedded in most organisations. Despite the radical change that the literature suggests will ensue from the localisation agenda, there was limited adjustments or transformations in the strategic management process by Irish INGOs to operationalise localisation since the 2016 WHS (n = 11). Irish INGOs acknowledge increasing “external” influences/incentives/pressure to support the localisation agenda. Most organisations recognise a certain inevitability to localise and acknowledge that the Grand Bargain, Irish Aid’s support to the localisation agenda and the more recent INGO initiative like the C4C, the START Network and Pathways to Partnership will impact their organisation’s position on localisation. However, while the localisation concept is reaching increasing acceptance, organisations are less clear on the practical steps to be taken to operationalise localisation.

Respondents were asked if their organisation has the required “internal capacity” to fully support the localisation policy or understanding of localisation (n = 12). Only one of the organisations has a dedicated localisation focal point, and this position is in the parent organisation. Most organisations are in the process of strengthening their partnership systems or supporting local organisations to access funding directly and to engage in the UN cluster system. Five organisations indicated areas that need to be strengthened to realise the organisations policies and strategies on localisation, namely:

• Greater attention and resources need to be given to the “cost” of localisation and the operations/activities required to shift power to the national/local.

• There is a culture shift required to transform attitudes and behaviours both internally and externally.

• Donors should provide further funding and appropriately design programmes to build the capacity of local actors in areas like Governance, Accountability, Compliance, Safeguarding, etc. It will be challenging for agencies to fully realise the ambitions of the grand bargain and meet donor contract conditions on all these governance requirements.

• A policy on localisation, and an agreed definition of what this concept means, for example, limits the extent to which we can hold ourselves to account. Additional resources are required to put in place improved structures and processes to enable this; and

• More knowledge and capacity in relation to what the role of an INGO is vis-à-vis localisation and truly supporting local partners.

In short, approximately half of the organisations acknowledge a need for significant adjustments in the very foundational aspects of the strategic management process to progress localisation. Primary among these are: finding shared principles and values, and agreeing joint policies between INGOs and their national/local partners. Given the recent history of Irish INGOs to professionalise by way of strengthened policies on issues such as accountability (anti-fraud), safeguarding etc., it is understandable that organisations might suggest a need for capacity building in new partnership agreements. The literature, on the other hand, suggests a need for capacity strengthening on the part of all partners to achieve complementarity in the localisation agenda. All this thinking points to the need for greater attention and resources in the short-term.

Respondents were asked if the culture of their organisation needs to change considering their existing and/or emerging localisation policy or understanding to localisation (n = 12). Four out of the twelve NGOs signalled the need for some cultural change/adaptation, as indicated below:

• Traditionally the organisation has worked as a direct implementer and supporting local authorities and the move to working with local CSOs is still a process to work through;

• Move from being a Eurocentric international organisation to become a global organisation through greater diversity and inclusion to enhance localisation;

• We risk being instruments or extensions of simplistic, risk averse and led donor approaches to localisation which does not meaningfully transform power relation. There is a sweet spot to be found to being a channel for donor funds and respecting local capacities, prioritisation, and ways of working; and

• Our organisation is in the process of institutionalising new ways of works to enhance its engagement with partners.

Localisation at the Programme/Country Level

Nine respondents indicated that localisation is part of their programming. Respondents cited a range of steps they were taking to ensure that localisation was taking place in their programmes, including:

• Adopting steps consistent with “Partnership in Practice” - these are at different stages across different countries.

• Mainly by strengthening initial needs assessment - identifying needs with communities, identifying priorities with communities, delivering programmes in consultation with local communities, post distribution monitoring, agreeing with the different layers of government and relevant ministries.

• Pushing our country offices, especially in our Irish Aid framework agreements, to deliver less directly themselves. To look to working through and with more local partners such as the CSOs rather than the local government.

• Greater equality between international and national staff measured in terms of numbers of staff and positions held. Improved engagement of civil society, not just national NGOs, in the aid process to include communities, families and affected persons.

• We train, fund, and ensure that local women’s organisations lead on all our humanitarian response work (and development work). We support research and capacity building to ensure that local women can have a seat in global decision-making spaces such as UN, ECOSOC, etc. We provide a secretariat for the Feminist Humanitarian Network (70% of which is local organisations) and actively support them to build a profile, raising funds and advocating for women’s leadership.

• Our decision-making about how our funding is spent is based on the principle of subsidiarity, and as such is in line with the principle of localisation.

• Challenging our theories of change. This will involve monitoring flow of funds to local partners, investing in capacity of local partners, undertaking periodic global partnership surveys including their perspectives on our ways of working and role as partners. Ultimately there is a requirement to step back and give visibility to our partners in public spaces while transforming our country programmes to national legal entities.

• Devolving as many of our functions as possible to local staff and institutions. Keen to shift the authority and capacity away from Europe.

• In-country teams and Programme Design Teams are always looking for opportunities to partner to maximise quality of outcomes, nationally and internationally and will continue to pursue this commitment to working in partnership.

• Working primarily through local and national partners throughout the project cycle; providing more than 25% of humanitarian funding to local and national responders.

• Our operating model is to work with local communities–we do however need to consider how we work more with local NGOs/CBOs.

It is clear from the data that Irish humanitarian INGOs are engaging in a significant range of activities to operationalise localisation albeit with varying understanding of what localisation entails. While it has been evidenced in previous sections that limited adaptations or adjustments have been made to the “foundational” components of organisations (vision, mission, principles and values, policies) to steer localisation, one might hope that operational experiences will inform future policy.

The Real and Perceived Challenges to Support Locally Led Humanitarian Action

The literature frequently credits the 2016 World Humanitarian Summit with the drive to localise humanitarian action, while recognising that calls for greater local engagement are in train for decades. Given the tremendous buy-in in recent years, respondents were asked to proffer views on the emerging benefits, weaknesses, opportunities, and possible threat posed by the drive to localise humanitarian action.

The Potential Benefits to Localising the Humanitarian Effort

Irish Humanitarian INGOs are unanimous in respecting the potential to work “with” local responders. These organisations are acutely aware and respect the need for contextually appropriate and culturally sensitive humanitarian interventions. They stress the value of local engagement to enhance the efficiency, effectiveness, and connectedness/sustainability of humanitarian action. The potential benefits of localisation were not questioned. Their responses concur largely with Barbelet (2018) potential advantages to maximise national and local engagement.

The Challenges Associated with Localising the Humanitarian Effort

However, the study respondents identified a huge list of challenges to operationalise localisation. Principal among these challenges was the “risk” associated with sharing power with local partners. Respondents were keen to stress the demands of donors on issues of compliance, reporting mechanisms and the frequently compromised position that local organisations can be exposed to in the principled delivery of humanitarian aid. While the potential for localisation might not be questioned, the risks and responsibilities need to be shared. The international humanitarian community has established principles, codes, and standards that, while endorsed globally in the 2016 WHS, create de facto barriers for partnerships with local actors.

The move to localisation of humanitarian action will require a new type of “trust”. The very notion of putting affected people at the centre of the humanitarian effort will require a new way of looking at the “problem”. Disaster affected peoples need to be recognised as actors in their own survival and recovery as opposed to victims in need of assistance. The all too often focus on the “needs” of disaster affected populations should be expanded to include “needs and capacities” in a bid to exploit the potential complementarity of humanitarian stakeholders working towards a common goal.

While the international humanitarian community has established strong accountability mechanisms to ensure responsibility and transparency in its humanitarian interventions, this accountability needs to be expanded to broader global society. The “domineering traditions” of international humanitarian donors that Van Brabant and Patel (2017) refers will need to provide space for national and local voices.

The key challenges as identified by the respondent, not in any order of priority, include:

• Accepting “risk” in shared governance, financial control, compliance procedures and principled delivery of humanitarian action.

• Sharing control with national and local actors by providing unrestricted funding to allow local actors to develop their institutional capacities.

• Introduce mechanisms to address the power imbalances between international and local actors.

• Providing platforms to give space for national and local voices–especially in conflict contexts.

• Value complementarity and its potential over competition.

• Embrace local socio-political dynamics and exercise appropriate risk-taking while ensuring the “do no harm” principle is respected.

• Respecting that all actors are bound by the humanitarian principles.

• Balance a meaningful transformation of power relations with expediency to provide lifesaving assistance to those most in need.

• Respect alternatives to the global north’s constructs of “organisations” and preferred ways of working; and

• A move towards new ways of funding that supports shared operations.

Opportunities to Enhance Localisation

Covid 19 has given the localisation agenda a new impetus. It has shone a light on the importance of local actors and accelerated the painfully slow process to localise humanitarian response. All evidence would suggest that, given the advanced stages of the localisation debate, humanitarian INGOs are seeking out innovative ways to partner with local organisations rather than resorting to some sort of remote management. Whether forced by necessity or opportunism, Irish INGOs reported an accelerated sharing of power to national and local staff. Justification for this shift in power is increasingly levelled in criticisms of the “colonial nature” of the larger aid enterprise and the lack of respect for the capacities of local actors.

The COVID 19 pandemic has provided the opportunity/space for the international humanitarian community to take stock and reflect on existing power imbalances. Less than a generation ago, the European Commission’s directorate general for humanitarian aid considered humanitarian assistance as something only relevant to “third countries”. In the past 20 years it has expanded its remit to include “civil protection” and following the growing realisation of global climatic fragilities and the migration crises over the past years, the reality and relevance of humanitarian need is global. The exposure of the global north to humanitarian crises has also prompted an expansion in the very definition of humanitarian aid and associated discourse. Terms like assistance were replaced with action and the scope of the humanitarian endeavour expanded from one solely concerned with reacting to crises and disasters to preparedness/prevention, support during crises and recovery from crises. There is an inevitability about crises and disasters, however there is also a realisation that the impact of any crisis or disaster is often a function of governance and management. The COVID 19 pandemic has amplified this message as national authorities adopted disparate strategies in their bid to manage the pandemic. The jury is out on the efficacy of national systems to manage the COVID 19 pandemic, however the limitations of the international community has become increasingly apparent and the importance of national and local institutions to protect and assist their own populations in times of crises.

The key opportunities identified by the respondents, not in any order of priority, include:

• Greater allocations of funds reserved for local actors together with a strengthened mandate in decision making in UN programmes.

• More attention given to national legislation and robust approval procedures by relevant ministries.

• Locally led interventions with strong partnership components will strengthen acceptance and legitimacy of humanitarian interventions.

• A critical reflection and resultant transformation of power will enhance legitimacy and extend reach to those difficult to access.

• The Covid-19 pandemic will accelerate the transfer of power to local actors and provide greater visibility to local capabilities. It will go some ways to increase awareness/sensitivity and address related tensions kinked with traditional colonial tendencies and ways of working.

• It represents a more sustainable and long-term solution that taps into desire for communities to assist their own people.

• It will encourage donors to make direct funding (more) available and accessible to local and national actors through: Country-Based Pooled Funds (CBPFs); Humanitarian pooled funds; multi-year funding which should include some funds for institutional development. Ideal supports and tangible assets will be allocated to support project implementation and institutional sustainability.

• International actors and local/national partners can collaborate jointly throughout the programme cycle (including design, planning, proposal development, MEAL), and with crisis-affected people to share decision-making while taking on complementary roles and responsibilities. International actors and local/national actors can assess capacity strengthening needs for each other and develop action plans for jointly addressing these needs.

Finally, Respondents Identified the Main Threats to Enhancing Localisation at the Programme Level?

The International Humanitarian Community has grown organically frequently shaped by the geopolitics of the time. The contemporary International Humanitarian System is a much more recent phenomenon with its origin in UN general assembly resolution 46/182. The system like qualities of the diverse humanitarian stakeholder mix has consistently advanced in a bid to make principled humanitarian assistance available to disaster affected populations. The localisation agenda is just one of the many adaptations/transformations advised to put affected populations at the centre of the humanitarian effort and respect, recognise, rebalance, recalibrate, reinforce, or return some type of ownership or place to local and national actors (Barbelet, 2018). However, one should not underestimate the scale of this challenge and there are fears that a transformational approach to address what Van Brabant and Patel (2017) refers to as the domineering tendencies of International Humanitarian System will weaken the humanitarian economy in favour of national and local political systems.

The key threats identified by the respondents, not in any order of priority, include:

• Too much funding sent directly to local partners too quickly resulting in poor management and donors retracting their localisation ambitions. Funding transferred directly without adequate overheads with the result that “risk” is transferred to local players. “Partner” organisations need to build and invest in long term relationships. Existing funding mechanisms rarely provide the required funding to support capacity strengthening and generally adopt an accompaniment role deemed necessary to localise humanitarian action.

• Local organisations are challenged to comply with donor requirements and are required to assume unreasonable levels of “risk” to deliver principled humanitarian action.

• Great advances have been made in areas such as: safe-guarding beneficiaries and staff codes of conduct, financial management and dealing with misappropriation, and systems that challenges abuse of power. These standards are universal, and they cannot be let slip in the move to a more localised humanitarian action.

• There is a need to prevent a reinforcing of the patriarchal systems that are already in place. Colonial masters were frequently replaced by regimes that did little to protect the vulnerable in society. Not all local organisations are perfect, there will be mistakes (as with INGOs).

• Increased funding to local organisation will inevitably lead to competition for control and use of aid. As with the past experiences in the international community, there will be some level of corruption that undermines support for aid. Forced or instrumentalised approaches to localisation have limited impact and are unsustainable in the longer term. A managed approach will acknowledge the need for investment in capacity building, systems, and procedures best suited to supporting the localisation agenda.

• INGOs maybe unwilling to change practices. Donors have more control over INGOs/international staff and are perceived as a better bet to secure their resources and deliver results. The (potentially) slow pace of response may bring the desire for external support and implementation.

• Lack of clarity on defining localisation, the implications of poorly managed funding and ambiguity around definitions of local actors - governments, NGOs, private sector–all militate against the localisation agenda. These coupled with compliance requirements of international donors and asymmetries between international and local partners will combine to complicate efforts to meet standards expected by international donors. Limited guiding principles on localisation (especially in conflict settings) and the real or perceived threats linked to fraud, corruption and wrong doings renders staff on-the-ground less likely to take the risks with partners organisations that lack an acknowledged/recognised governance infrastructure that can be held to account.

• Lack of a common definition. Localisation remains a nebulous and ambiguous concept that makes it difficult to hold stakeholders to account. International actors treat local/national actors as sub-contractors with limited roles in project design or management. Local and national actors lack adequate representation and active participation of humanitarian coordination mechanisms and there is no clear plan for transitioning to local leadership.

• Despite the obvious funding and competition anomalies, there is a big fear that the localisation agenda will expose local/national capacity differences. Stronger local humanitarian organisations are “ripe” for partnerships with very willing international organisations. The weaker local organisations, that in many cases have greater potential to gain access to those most in need, could easily be lost to the localisation process.

Conclusion

In returning to the study question - How Irish International NGOs are embracing the Localisation Agenda? –there is a genuine commitment on the part of Irish humanitarian INGOs to embrace the localisation agenda. This commitment is firmly grounded in recognised potential strengths of an aid programme that is contextually appropriate and culturally sensitive, and owned by national and local stakeholders. The majority of Irish humanitarian INGOs are largely dependent on government funding and their modus operandi are significantly influenced by associated rules and regulations. Governance and management mechanisms have evolved to support rigorous accountability, compliance and regulatory functions while remaining true to the humanitarian principles and in particular humanitarian independence. This disparate grouping has sought to deliver principled humanitarian action while remaining true to their traditional values whether this is aligned with Dunantist, Wilsonian or Faith-based traditions. These value systems obviously influence the potential for INGOs to either establish organisations in disaster affected countries or develop partnerships with existing stakeholders.

While cognisant of the value of local ownership, Irish INGOs have developed systems to engage local actors from minimalist consultations through to elaborate partnerships. A stated key attribute governing the nature of the engagement is the level of trust and the real or perceive capacity of local actors to lead humanitarian interventions. All evidence would suggest that this trust is strongest among organisations that share values and policies in addition to humanitarian principle, which are common for all stakeholders. Alignment of existing values with localisation values such as respect for local capacity, acknowledgement of local ownership, together with a shift in worldview to the proposed emergent complexity at the local level will require changes in the domineering tendencies of the international stakeholders. While donors, and to a lesser extent humanitarian INGOs, will be slow to accept a rowing back on real or perceived advances to professionalise humanitarian action, national and local organisations will be required to go some way to earn and maintain the trust of their international partners. In the same vein, policies on issues such as gender issues, safeguarding, anti-fraud, complaints mechanism etc., if aligned with local complexity, will form part of developing these envisaged trusted relationship.

There is overwhelming agreement with the potential advantages to bring decision making closer to the local, to provide more direct funding to the local level and to seek out complementarity in the aid effort that capitalises on stakeholders existing and potential capacities. However, there is less agreement on the notion that localisation is more cost effective and some organisations would posit that efficiencies will only be realised in the longer term and there is a cost associated with localisation. There is good reason to suggest that governments and other stakeholders from disaster affected countries, that were vocal in their calls for localisation at the 2016 WHS, will have a significant role in supporting and regulating the NGOs and CSOs in their respective jurisdictions. Given the predictions of increased humanitarian need, improved contextually appropriate government policies on registration and regulation, will significantly enhance the confidence of donors to directly fund local third sector organisations. International humanitarian INGOs have made tremendous strides to “professionalise” in a bid to earn and maintain trust with donors, both public and private. Much learning can be gleaned from national NGO umbrella organisations, such as DOCHAS, that have supported their constituency to build their governance, management and administrative structures and processes to reduce “risk” and provide supports on soft regulation.

The jury is out on the notion that localisation will improve access to those hard to reach with many organisations believing that, unless managed carefully, the localisation agenda will do little more than preserve the status quo and further marginalise those worst impacted by disasters The localisation agenda, while lacking a common definition, promises greater local ownership, respect for local capacities and a heightened level of complementarity in the aid effort. The required trusted relations needs to extend beyond just the most vulnerable to include other national and local stakeholders.

All evidence from this study suggests that Irish humanitarian INGOs are convinced in the potential for the localisation agenda. The potential strengths are unanimously accepted, however, the challenges are many and varied. Most of the challenges are directly or indirectly related to the relationship that has evolved between Irish humanitarian INGOs and donor agencies, especially the Irish Government. Irish humanitarian INGOs have established trusted governance, financial accountability and compliance systems aligned with donor requirements and accept ways of working. The shared ownership envisaged by the localisation agenda and the strengthened partnerships with a range of local stakeholders will inevitably result in less control in what is perceived as the domineering international community. The transition to this new way of working will bring risk. While all efforts need to be made to reduce this risk it needs to be shared by all stakeholders in a bid to realise the potential of the localisation agenda.

Author Contributions

PG - responsible for the conceptual design, literature review, methodology, analysis and writing. CO-B - supported the literature review, the design of questionnaire and data collection and data presentation.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1DOCHAS is the Irish association of Irish Non-Governmental Development Associations (www.dochas.ie/).

2Misean Cara, while relatively limited in size of operations, has a significant global reach given its modus operandum as an Irish faith-based missionary movement

3Charter for Change is a global effort for INGOS to “practically implement changes to the way the Humanitarian System operates to enable more locally-led response”.

References

Barakat, S., and Milton, S. (2020). Localisation across the Humanitarian-Development-Peace Nexus. J. Peacebuilding Dev. 15, 147–163. doi:10.1177/1542316620922805

Barbelet, V. (2018). As Local as Possible as International and Necessary: Understanding Capacity and Complementarity in Humanitarian Action. London: HPG Working Group, ODI.

Geoffroy, V., and Grunewald, F. (2017). More Than the Money: Localisation in Practice. Retrieved 02 30, 2021, from Trocaire: https://www.trocaire.org/sites/default/files/resources/policy/more-than-the-money-localisation-in-practice.pdf.

Hilhorst, D., Desportes, I., and de Milliano, C. W. J. (2019). Humanitarian Governance and Resilience Building: Ethiopia in Comparative Perspective. Disasters 43 Suppl 2, S109–S131. doi:10.1111/disa.12332

Nuopponen, A. (2010).Methods of Concept Analysis – a Comparative Study. LSP Prof. Commun. Knowledge Manag. Cogn. 1, 1. Available at: http://lsp.cbs.dk.

Roepstorff, K. (2019). A Call for Critical Reflection on the Localisation Agenda in Humanitarian Action, 41, 284–301. doi:10.1080/01436597.2019.1644160A Call for Critical Reflection on the Localisation Agenda in Humanitarian ActionThird World Q.

Van Brabant, K., and Patel, S. (2017). Understanding the Localisation Debate. Retrieved from Global Mentroing Initiative: http://a4ep.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/GMI-UNDERSTANDING-THE-LOCALISATION-DEBATE.pdf.

Keywords: Localisation, Trust, Risk, Compliance, Humanitarian

Citation: Gibbons P and Otieku-Boadu C (2021) The Question is not “If to Localise?” but Rather “How to Localise?”: Perspectives from Irish Humanitarian INGOs. Front. Polit. Sci. 3:744559. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.744559

Received: 20 July 2021; Accepted: 13 September 2021;

Published: 30 September 2021.

Edited by:

Kilian Spandler, University of Gothenburg, SwedenReviewed by:

Thomas Peak, University of Cambridge, United KingdomDaniela Irrera, University of Catania, Italy

Copyright © 2021 Gibbons and Otieku-Boadu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Pat Gibbons, cC5naWJib25zQHVjZC5pZQ==

Pat Gibbons

Pat Gibbons Cyril Otieku-Boadu

Cyril Otieku-Boadu