94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci., 04 January 2022

Sec. Peace and Democracy

Volume 3 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2021.741956

This article is part of the Research TopicChallenges to Local Democracy: Democratization Efforts and Democratic Backsliding at the Sub-national LevelView all 6 articles

The reintegration of Central and Eastern European (CEE) economies into globalized capitalism resulted in increasing regional polarization and the emergence of internal peripheries. The crisis of the globalized capitalist economy in 2008 resulted in the further peripheralization of rural areas, and the related crisis of representative democracies triggered rural resentment against the existing order. Inhabitants of peripheralized areas have a feeling of abandonment and political discontent. The rise of right-wing populism may be understood as a revolt of people living in precarious conditions in peripheralized areas both in Hungary and Germany. Left-wing populism, which builds on equality and social justice and is based on radical democracy, has not been able so far to reach the precaritized inhabitants of peripheralized rural areas. Solidarity economy, which is a contemporary social movement, refers to a comprehensive program aimed at transforming the entire economy, and may have the potential to address the political discontent of people living in peripheralized rural areas. In spite of the rising support for right-wing populism, social and solidarity economy (SSE) initiatives are being carried out in rural peripheries. These initiatives are based on the principles of participatory and economic democracy. Spaces provided by SSE initiatives can become forums for deliberation and co-management to develop economic democracy and become seeds of a solidarity economy movement in CEE. Therefore, based on a critical realist ethnographic approach, this paper aims to answer the question of how SSE initiatives may address the everyday material challenges and political discontent of people living in peripheralized villages by studying two SSE initiatives being carried out in two contrasting cases of peripheralization. Studying SSE initiatives in relation to 1) the locality they are embedded in, 2) “subaltern” groups within the locality, and 3) participatory, economic and 4) representative democracy helps to better understand in what ways SSE initiatives can mobilize political discontent to strengthen the solidarity economy movement in CEE.

The post-socialist transformation, or the reintegration of Central and Eastern Europe into globalized capitalism (Hardy 2014; Themelis 2016) has resulted in a massive social and economic crisis (UNDP 2008; Leibert 2013) and an extremely polarized regional development where “rural peripheries” stagnate at a low level or fall even further behind “urban centers” (Smith and Timár 2010; Ehrlich et al., 2012; Lang 2012). A number of regions in the CEE countries, including East Germany, have been through a process of “peripheralization” (i.e. loss of social capital due to selective out-migration of the better-off population, economic decline, lack of local purchasing power, and a qualitative and quantitative shrinking in public services) (Ehrlich et al., 2012; PoSCoPP 2015). Peripheries are produced and reproduced through mechanisms of selective in- and out-migration, disconnection, dependence, stigmatization (Kühn and Weck 2013: 24), and social exclusion (Leibert and Golinski 2016). A person, a group, or an area might all be subjected to processes of peripheralization (Meyer and Miggelbrink 2013: 207).

The crisis of the globalized capitalist economy, which resulted in the peripheralization of rural areas and the related crisis of representative democracies, triggered rural resentment against the existing order. This resentment has manifested itself in rural support for right-wing populist parties and in grassroots nationalist movements (Mamonova et al., 2020) both in Hungary (Kovai 2018; Szombati 2018; Vigvári 2019) and in Germany (Lees 2018; Vorländer et al., 2018; Förtner et al., 2021; Schmalz et al., 2021). Left-wing populism (Goes and Bock 2017; Mouffe 2018; Förtner et al., 2021), which builds on “equality and social justice” (Mouffe, 2018: 47) and a radical democracy “in which differences are still active” but where people are united in their opposition against “forces or discourses that negate all of them” (38), has not been able so far to reach the precaritized inhabitants of peripheralized rural areas.

In an era of political discontent (Schmalz et al., 2021) the solidarity economy movement, which aims for the transformation of the economy (Coraggio et al., 2015; Gagyi 2020), may also have the momentum to mobilize the inhabitants of peripheralized areas, who have a deep-rooted feeling of being left behind and of sociocultural and material deprivation (Schmalz et al., 2021). In essence, solidarity economy refers to economic cooperation that is resilient to the compulsion of infinite accumulation, and that operates based on the principles of economic democracy and ecological sustainability (Gagyi 2020: 11). The term solidarity economy became used in South America in the 1980s (Razeto, 1984), and in Europe (Laville 2010) in theorizing the informal economy that emerged as a response to the crisis of the 1970s. Later on, it became globally known in the 1990s and 2000s due to the new international networks (RIPESS, EMES, CIRIEC) dealing with solidarity economy, and the alter-globalization movement. Solidarity economy is a framework through which already-existing initiatives—such as sustainable farming communities, community enterprises, cooperatives, nonprofit enterprises, social enterprises, foundations and publicly-owned nonprofit companies—can network and cooperate with each other (ibid.). As of today, international research networks dealing with democratic and sustainable economic models use the term “social and solidarity economy” (SSE), in which they distinguish the terms “social enterprise,” “cooperative,” and “social economy,” which refer to specific economic organizations, and the term “solidarity economy” referring to systemic transformation (RIPESS 2015 in Gagyi et al., 2020: 296). Despite the increasing support for right-wing populist parties and emergence of grassroots nationalist movements, participatory democratic SSE initiatives are also being carried out in rural areas undergoing peripheralization. Participatory democratic projects call for the deepening and radicalizing of democracy in response to the limits of liberal representative models as a privileged form of state-society relations (Dagnino 2011:126). Spaces provided by social and solidarity economy initiatives can become forums for deliberation and co-management aimed at developing economic democracy and becoming the seeds of a solidarity economy movement in CEE. Therefore, this paper asks the following question: How do SSE initiatives address the everyday material challenges and political discontent of people living in peripheralized villages?

To answer this question based on a critical realist (Bhaskar 1978, Bhaskar 1983, Bhaskar 1989a and Bhaskar 1989b, Gorski 2013) ethnography (Brewer 2000; Porter 2001), this paper introduces two social and solidarity economy initiatives being carried out in peripheralized areas of East Germany and Hungary. Both SSE initiatives have a participatory approach, but their local stakeholders are marginalized to a different extent. In the first case, a complex development program based on employment has been created for and by the Roma and non-Roma inhabitants of a Hungarian village undergoing advanced peripheralization (ghettoization). As the symmetric structures of reciprocity (Polanyi 1971a and Polanyi 1971b) in the community have already been destroyed through processes of peripheralization, the key initiator of the participatory democratic project is a representative of a local pro-Roma Foundation, and comes from outside of the village. In the second case, in a village undergoing moderate peripheralization in North-Eastern Germany, cheap land and the proximity of nature have provided an attractive environment for ecologically-minded people (both from eastern and western Germany) searching for a rural alternative for their urban lifestyles. The newcomers (“Zugezogene”) have created an alternative village school organized around the idea of environmental sustainability.

In order to explain how SSE initiatives emerging in differently peripheralized (moderate and advanced) areas may address the everyday material challenges and political discontent of people living in rural peripheries, the connection between peripheralization, political discontent and right-wing populism will first be outlined. Then the paper will seek to clarify the connection between peripheralization, political discontent, and social and solidarity economy. In the methodology section, the critical realist ethnography and the research methods—such as participant observation, interviews with the key actors of the initiatives, and documentary analysis—will be outlined. In the results section, 1) the relationship between SSE initiatives and peripheralization will be elaborated upon, 2) the perspective of the most marginalized will be brought in, and the relationship between SSE initiatives and 3) participatory and 4) representative democracy will be elaborated upon. The conclusion will explain how SSE initiatives may serve as seeds for a solidarity economy movement in CEE through addressing the everyday material challenges of people living in peripheralized areas.

The rise of the radical right both in eastern Germany and Hungary is connected to the political discontent of the inhabitants of peripheralized areas, who have a deep-rooted feeling of being left behind, and to sociocultural and material deprivation (Schmalz et al., 2021) in internal peripheries which are characterized by economic stagnation and selective outmigration. To better understand the emergence of internal peripheries, spatial researchers are turning to the concept of “peripheralization”. While “periphery” is a rather static notion, with the term “peripheralization” the dynamics behind processes in which “peripheries” are produced through various social relations can be understood (Lang 2012; Liebmann and Bernt 2013; Kühn 2014; Weck and Beißwenger 2014; PoSCoPP 2015). While researchers who focus on peripheries are interested in remote locations or spaces with sparse populations, with the notion of peripheralization the political, economic, social and communicative processes through which peripheries are made can be discerned (Lang 2012, 2015).

The post-socialist transformation of Central and Eastern European (CEE) economies implied their (re)integration into global capitalism (Hardy 2014; Themelis 2016) as “dependent market economies” (Nölke and Vliegenthart 2009) which are dominated by foreign direct investment and have only a limited degree of economic sovereignty (Smith and Timár 2010; Nagy et al., 2021). This development was accompanied by internal polarization, with some regions being transformed into important hubs of global capitalism and others losing economic relevance (Schmalz et al., 2021). Processes of peripheralization and regional polarization were amplified by the steady erosion of the European social model that was linked to the financial crisis in 2008. To reduce budget deficits, European countries, including Hungary and Germany, turned towards politically contested cuts (Lees 2018), and the state started to withdraw from the provision of welfare services. Europe had entered the age of “austerity,” “a form of voluntary deflation in which the economy adjusts through the reduction of wages, prices and public spending to restore competitiveness, which is (supposedly) best achieved by cutting the state’s budget, debts and deficits” (Blyth 2013: 2). The pain generated by these adjustments and the subsequent political upheaval led to the emergence of significant political challengers to the political elite and its crisis management strategy in some European polities including Hungary and Germany.

The radical right Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) party was founded in 2013 as a nationalist ordo-liberal party opposed to the Euro currency (Friedrich, 2017). The AfD performed strongly in the 2017 Federal election across Germany, but did particularly well in states of the former German Democratic Republic (East Germany, Lees 2018). The most important findings for explaining the higher AfD share of the votes in East Germany focus on the 1990s, with its policies of (often fraudulent) privatization, mass unemployment, and national and EU policies incapable of and/or unwilling to raise the economic standard of the east to that of western Germany (Falkner and Kahrs 2018: 39; Miggelbrink, 2020; Schmalz et al., 2021). This resulted in a specific East German identity based on social insecurity, feelings of being left behind, the consequences of a wide-ranging shift of social values, and the experience of having suffered the devaluation of past accomplishments (Begrich 2018: 41 in Förtner, Belina, Naumann 2021: 579). A city versus country pattern was also observed as playing a role in the support of right-wing populists in Germany. In one quantitative study, “ruralness” correlated positively with a higher number of votes for the AfD at the municipal scale in the East, but not in the West (Deppisch et al., 2019 in Förtner et al 2021: 579). A study showed that, instead of racism being the main explanation for the success of the AfD, insufficient public transportation and social infrastructures are the important reasons within small towns and villages for feeling disadvantaged in comparison to refugees, and for feeling neglected by politicians (Hillje 2018).

Similar to Germany, the support base of the radical right comes from structurally disadvantaged regions of Hungary, where the population has to face livelihood challenges and has a feeling of abandonment. In Hungary, both can be linked to the politics of “Europeanization”. The decline of agricultural prices and production in connection with the process of European integration (which forced Hungary to open its doors to import products) contributed to the emergence of anti-liberal sensibilities among independent agricultural producers who bore the brunt of “Europeanization” in rural areas (Szombati 2018: 3). The post-peasants’ growing intolerance of the surplus population, among which Roma are overrepresented, was enhanced by local authorities’ unwillingness to clamp down on petty forms of criminality and the left-liberal government’s efforts to emancipate Roma (qua ethnic group) under the banner of “Europeanization” and “integration politics” (Szombati 2018: 19). The ethnographic works of Szombati (2018) show how far-right activists and politicians crafted a strategy that allowed the previously marginal Jobbik Party to entrench itself as the voice of the “abandoned countryside” and to firmly place the “Gypsy issue” at the top of the political agenda, while the main right-wing Fidesz Party adopted elements of the new racist common sense to outmaneuver Jobbik (Szelényi 2018: XII). According to Szombati (2018: 19), popular racist sensibilities against Roma were absent outside peripheralized areas in Hungary, which offers a partial explanation for the emergence of popular anti-Roma racism in the Northeast. After its historic victory at the parliamentary elections in 2010, the right-wing Fidesz reorganized the state to the advantage of the bourgeoisie and (to a lesser extent) the lower middle class, to the detriment of the most vulnerable segments of society (Szombati 2018: 237). Fidesz, building on Orientalist logic and clichés (Szombati 2018: 236), capitalized on the European “refugee crisis” to instigate a moral panic against Hungary’s inundation by “uncivilized Muslim hordes” (see Thorleifsson 2017). Our prime minister echoed rightist politicians in Western Europe, and prompted the general public to recognize him (and the fence he built on Hungary’s southern border) as the savior of Christian Europe (see Brubaker 2017).

Both Fidesz, founded in 1988 and governing Hungary since 2010, and the AfD, which was founded in 2013 and entered the national parliament as a right-wing, populist and at least partially extreme nationalist party, build their political strategy on anti-politics. Anti-politics is both a mode of making political claims, and a political strategy that negates arguments, negotiations, and compromise, and starts instead with absolute, non-negotiable positions (Förtner et al 2021:577). This mode of thinking and arguing fits subjectivities produced under neoliberalism and makes them compatible with right-wing positions, which selectively challenge the progressive aspects of neoliberalism (ibid.).

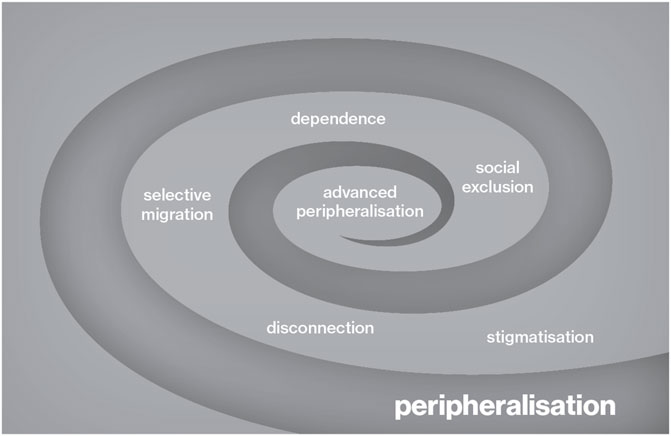

Peripheralization is a useful concept to better understand the emergence of internal peripheries as spaces of political discontent in which right-wing populist politics have been successful in mobilizing citizens. Based on a multi-dimensional approach to peripheralization (considering it a social, economic, political, and discursive process), peripheries are produced and reproduced through mechanisms of selective migration, disconnection, dependence, stigmatization (Kühn and Weck 2013: 24), and social exclusion (Leibert and Golinski 2016) (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. Mechanisms of peripheralization, Source: the author, based on Leibert and Golinski 2016, design: Tibor Szikora.

At a discoursive level, areas, groups, and people can be subjected to stigmatization (Meyer and Miggelbrink 2013: 207). In certain development discourses, through ignoring overlapping processes causing structural disadvantages (e.g. shrinking quantity and quality of locally-available public services, and economic restructuring), remote rural areas become stigmatized as “declining,” “backward,” “lagging-behind” or “non-innovative.” Koobak and Marling (2014) show that depicting peripheries as lagging behind and in need to catch up stems from a discursively hegemonized normative development concept that translates spatial into temporal differences. This developmentalism is deeply rooted in both capitalist and socialist modernity (Plüschke-Altof 2017: 63). Conceptualizations of development, desired policy outcomes, and funding priorities shape regional policies and investment decisions. As a result, stigmatized rural villages face further economic disinvestments, or investments exploiting local (natural) resources and the withdrawal of the state from public service provision.

Disconnection is another dimension of peripheralization. It can be understood as a progressive distancing of the peripheries from regulatory systems, like the state or the market, based on decisions made in the centers of economic and political power (Kühn and Weck 2013: 33). Disconnection has an economic and infrastructural dimension (Leibert and Golinski 2016: 261). Since in most depressed regions business density is particularly low, and only a few industries are present, finding jobs locally becomes increasingly challenging. Disconnection may happen through infrastructural marginalization too. In an effort to cut public spending, public authorities are less and less willing to provide non-cost-effective basic services (e.g. health care, and public transport) in rural regions, while private enterprises are not interested in filling the gap left by the receding state (Leibert 2013: 106–107; Naumann and Reichert-Schick 2013: 159).

The stigmatization and the material, everyday consequences of economic and infrastructural disconnection of a peripheral rural area can lead to individual decisions to leave. Out-migration is a selective process, as people who have the financial, human and social capital to do so will leave first. On an individual level, migration is considered as “the only way out from social and spatial marginality and the existing systems of dependencies” (Nagy et al., 2015, 149). “Those who stay behind, join the group of those who are marginalized in various social nexuses, and become dependent on local agents and institutional practices” (ibid.). Beyond selective out-migration, cheap housing in peripheralized areas resulted in the selective in-migration of poor families, among which Roma are overrepresented in Hungary (Lennert et al., 2014). As a result of selective migration, the concentration of immobile populations (the elderly, the less educated, and the long-term unemployed) can be observed in peripheral rural areas (Leibert 2013: 115).

Dependence is the political dimension of peripheralization, and refers to a spatially-organized inequality of power relations and access to material and symbolic goods (Fischer-Tahir and Naumann 2013: 18). The political relation between centers and peripheries at the regional level is marked by conflicts between the central and peripheral elites (ibid.: 375). “To have power is to exercise a measure of autonomy in decisions and to have the ability to carry out these decisions” (Friedmann 1973: 48). Marginalized communities receive limited authority, and they are hindered in developing their capabilities to participate in decision-making processes. Therefore, the concepts of autonomy and empowerment become important in discussing in what ways communities may counteract processes of peripheralization.

Peripheralized areas are also spaces of social exclusion. This term relates mainly to the protection of a certain group’s social status in a way that causes other groups to get into a deprived position (Szalai 2002). Intersectionality theory is a (critical) feminist approach rooted in black and feminist social movements (Carastathis 2014; de los Reyes and Mulinari 2020), which describes the various forms of inequalities through institutional and representational dynamics (Kóczé 2011: 2), and thus helps to better understand how certain factors—such as ethnicity, class, gender, or place of residence—influence marginality and social exclusion.

The five dimensions of peripheralization are interrelated, and they often accelerate each other’s effects, resulting in advanced peripheralization (Figure 1). In line with Wacquant’s theory of advanced marginality (Wacquant 1996, 2008), the concept of advanced peripheralization is used in this work to emphasize that peripheralization is relational, and other influences on it include national welfare policies, embeddedness into the globalized capitalist economy, and the history of ethnic-based oppression. Racialization, through which ethnic-based oppression happens, is the division of the world population into categories based on the color of their skin and their geographical origin (Petrovici et al., 2019: 5–6). It was the mechanism by which the naturalization of the inferiority of certain categories of people and contingencies of labor force was institutionalized (ibid.: 6). In the case of Central and Eastern Europe, as elsewhere, the occurrence of racialization is entangled with spatial marginalization and segregation in severely deprived areas. While in Hungary in the last three decades, as a result of socio-spatial polarization processes within rural spaces, economic decline and racialization-based ethnic exclusion produced contagious “ghettoes” (G. Fekete 2005; Smith and Timár 2010; Virág 2010), in the German context the phenomenon of a “rural ghetto” does not exist. Ethnic-based spatial segregation takes place in Germany characteristically with immigrant workers in cities (Glitz 2014). Advanced peripheralization as a political economy of space (Brewer 2000; 2009a and b in; Vincze 2019) has a role to play in the dynamics of capitalism, because it creates marginalized housing areas where racialized labor power is socially reproduced (Castells 1977 in Vincze 2019).

The reintegration of CEE economies into globalized capitalism resulted in increasing regional polarization, and the emergence of internal peripheries. Inhabitants of peripheralized areas have a feeling of abandonment and political discontent, which has been successfully mobilized by right-wing populist parties. Left-wing populism (Goes and Bock 2017; Mouffe 2018; Förtner, Belina, Naumann 2021), which builds on “equality and social justice” (Mouffe, 2018: 47) and a radical democracy “in which differences are still active” but where people are united in their opposition against “forces or discourses that negate all of them” (38), has not been able so far to address the precaritized inhabitants of rural peripheries.

On a policy level, social and solidarity economy, social innovation and social enterprises, are widely referred to in the European Union (Fougère et al., 2017) as having the potential to contribute to cohesion policy through counteracting processes of peripheralization, e.g. through providing jobs for the long-term unemployed (UNDP 2008; European Commission 2011; Schomaker 2016) or stepping in to the provision of public services (e.g. public transport, education, health care, and elderly care). The emergence of the social enterprise field in CEE (such as social cooperatives, and work-integration organizations) can be linked to EU policies and international donor programes rather than to national policy reform strategies (Leś and Kolin 2009; Srbijanko et al., 2016; Vidović and Rakin, 2017; Kiss and Mihály, 2020). In line with a neoliberal approach towards tackling socio-spatial inequalities, funding opportunities are widely available for setting up rural social enterprises in CEE, but this funding is only available on a project basis and expects rural social enterprises to increasingly be able to finance themselves from their market-based income, and to overcome their “dependency” on grants and subsidies (Fougère et al., 2017; Baturina et al., 2021). Both socio-spatial inequalities and expectations to tackle them are higher in CEE than in Western Europe (UNDP 2008: 31), while funding on a statutory basis is decreasingly available for rural social enterprises due to the austerity measures and the withdrawal of the welfare state (European Commission 2019). The faith that social enterprises may tackle the complex challenges of peripheralization through relying on their market-based resources (the “earned-income” school of thought, see Defourny and Nyssens 2010) supports the further withdrawal of the state from welfare service provision (Amin 2009).

Both academic literature and policy papers discussing social enterprises in CEE are embedded within the European integration narrative and thus have an economic coloniality (Lucas dos Santos and Banerjee 2019: 4). Development in this framework is understood as a universal and evolutionary process (Lucas dos Santos and Banerjee 2019: 4). It is argued within this narrative that the success of catching up depends on the cultural specificities of the semi-peripheral countries (Barna et al., 2018). Put differently, such a narrative is built on the symbolic supremacy—or cultural hegemony—of countries at the center of the global economy (the United States or those in Western Europe) and on the expectation that semi-peripheral countries (such as those in the CEE region) need, and are able to catch up with, countries at the center of the global economy (Barna et al., 2018). Catching up is interpreted as the achievement of a moral and aptitudinal similarity, while the lack of catching up as a moral and aptitudinal gap (Böröcz 2006). As a result, dependence on the center and symbolic subordination determine the epistemologies of social enterprise researchers in CEE. Embedded within the European integration narrative, CEE is portrayed as “underdeveloped” (UNDP 2008; Galera 2009), “backward”, and “lagging behind” compared to Western Europe, which is seen “progressive”. One of the first pieces of research about social enterprises in CEE was conducted by Western European social enterprise researchers (UNDP 2008). This research applied an “ideal-typical” definition of social enterprise that was a simplified version of that used in Western Europe. Based on this definition, it is not necessary for a CEE social enterprise to build its economic activity on market-based income, to have continuous economic activity, to take economic risks, to be set up by actors from the civil society, or to have participatory governance (UNDP 2008). If the social enterprise definition is an “ideal type” in Weber’s terms, i.e. “an abstract construction based on all major characteristics that may be found in social enterprises, although most social enterprises do not possess all these characteristics at the same time” (UNDP 2008: 32), why is this “ideal type” definition simplified when applied to Eastern Europe? It is necessary to develop a more questioning attitude towards constructions of socialist and post-socialist societies, while joining others in their efforts to dismantle imperialist and homogenizing understandings of “the west” and “the rest” (Hörschelmann and Stenning 2008: 349). Cold-war ideologies have positioned us strongly in both the former east and west (Verdery 1996; Hörschelmann, 2001 in Hörschelmann and Stenning 2008: 349), leading to taken-for-granted notions about the self and the other (Buchowski 2006 in Hörschelmann and Stenning 2008: 349) and to strong assumptions about the value and universality of concepts such as “democracy”, “the market” or “civil society” (see above; Hann 1998; P. Watson 2000 in Hörschelmann and Stenning 2008: 349). Civil society is not necessarily weak in CEE (Foa and Ekiert 2017), but the institutional environment may hinder a civil society organization’s advocacy (political) role (for Hungary see Kövér 2015). State-civil society relationships are characterized by clientelism rather than partnership in CEE (for Hungary see Kövér 2015). Similar to other regions on the semi-periphery of the global economy (for South America see Dagnino 2011, for Spain see Caro Maya, Werner Boada 2019), civil society organizations that do not question the establishment have better access to state funding in CEE. Social enterprise researchers need to be reflective about the legacies of cold war ideologies when studying social enterprises in CEE. The aim of this research is to present examples of rural social enterprises from the CEE region to show that participatory SSE initiatives are possible in our region, notwithstanding state-socialist oppression of civil society (Galera 2009: 254; UNDP 2008: 35), withdrawal of the state from funding civil society that questions the establishment (Kövér 2015), centralization of power and funding sources (Nagy et al., 2021; Pálné Kovács 2021), and the limited access of inhabitants of rural areas to processes of political decision making (Amin et al., 2002: 17).

Theories on social enterprises developed from the North-South Dialogue provide inspiration to better understand social and solidarity economy initiatives in Central and Eastern Europe (Coraggio et al., 2015; Hulgård et al., 2019). Solidarity economy refers not only to the multitude of economic organizations based on the principles of economic democracy, and social and environmental justice, but also to the wider economic cycle, which connects together solidarity enterprises operating in different areas of the economy (Gagyi et al., 2020, 296). Another feature of solidarity economy is that it refers not only to the development of a third, more ethical, economic sector complementing the functions of the market and the state, but also to a comprehensive program aimed at transforming the entire economy (ibid.). Solidarity economy is embedded in recent social movements which have been mobilized by the forthcoming climate catastrophe and the management of the global economic crisis, and which put increasing pressure on social reproduction (Gagyi 2020; de los Reyes and Mulinari 2020). A new consensus seems to be emerging among the progressive left (criticizing the operation of the global capitalist economy), green (criticizing the destruction of ecosystems), and feminist (that act against the exploitation of reproductive labor) social movements, which contrasts the vision of a democratic global economy that serves the sustainability of social and ecological systems with the limitless capitalist accumulation (economic growth) that results in climate catastrophe and the reproductive crisis (Gagyi 2020; de los Reyes and Mulinari 2020).

Social enterprises in a solidarity economy framework are based on the principle of economic democracy (Coraggio et al., 2015; Lucas dos Santos and Banerjee 2019). Economic democracy is a system of checks and balances on economic power, and support for the right of citizens to actively participate in and shape the economy regardless of their class, race/ethnicity, gender, etc. (Johanisova and Wolf 2012). Economic democracy does not exist in the absence of autonomy and the power of choices (Lucas dos Santos and Banerjee 2019: 8).

From a relational view (Mackenzie, 2010) autonomy—understood as both the capacity to lead a self-determining life, and the status of being recognized as an autonomous agent by others—is crucial for a flourishing life in contemporary liberal democratic societies (Mackenzie 2014a: 41; Veltman and Piper 2014). If autonomy is understood relationally (in contrast to its libertarian framing) then the apparent opposition between responding to vulnerability and promoting autonomy dissolves and, furthermore, duties of protection to mitigate vulnerability must be informed by the overall background aim of fostering autonomy whenever possible (Mackenzie 2014b: 41). Oppressive structures, such as capitalism, patriarchy and racism, influence the autonomy status and capacity of individuals. Intersectionality theorists argue that oppression is produced through the interaction of multiple, decentered, and co-constitutive axes. This controverts orthodox Marxist approaches, for instance, which claim that class has causal and explanatory priority to gender and race (Carasthatis 2014: 308). “Racial” oppression and “gender” oppression distort their simultaneous operation in the lives of people who experience both (Combahee River Collective 1977 in Carasthatis 2014: 305). Intersectional discrimination is named by activists as “double exclusion” (gendered, ethnicized) and is dominated by both Romani patriarchal and non-Romani political and economic regimes (Kóczé 2016: 51). Intersectionality theory advances an understanding of the situation of (Roma) women living under the conditions of (advanced) peripheralization. The relevance of intersectionality lies not only in analyzing the social divisions which make inequality possible, but also in its ability to politicize inequalities, which is its transformative and emancipatory character (de los Reyes and Mulinari 2020: 185). Political feminist practices are transforming intersectionality from an isolated academic and societal concept to an everyday practice of political coalitions and dialogues, and towards strategies to organize hope-creating spaces for resisting and living against and beyond the existing social order (Dinerstein, 2015 in de los Reyes and Mulinari 2020: 192).

The desire to democratize is expressed, in practice, through solidarity from the ground up, which maintains and legitimizes the purpose of social enterprises (Coraggio et al., 2015: 242). However, even if social enterprises are often set up to protect their stakeholders from the devastating effects of market society, they may in some cases promote domination (ibid.). All social enterprises organize forms of protection, but the social enterprise in a solidarity economy perspective additionally tries to bring together protection and emancipation. In other words, the solidarity perspective emphasizes the importance of emancipation and implementation of actions leading to protection and emancipation, rather than choosing between one or the other (Coraggio et al., 2015: 243). Enhancing the abilities of individuals and communities to live dignified lives is fundamentally connected with a critical reflection of the current societal order, recognizing structural barriers to equality and justice, and advocating changes not only in individuals and communities but also at a societal level (Ryynänen and Nivala 2017). A framing of empowerment that draws on the ideals of participatory democracy emphasizes the right of the structurally marginalized to participate in public spaces and political decision making, and the need to engage with them in new and different ways to encourage this (Málovics, Méreiné Berki and Mihály 2021). In such a view, public spaces can be seen as spaces in which conflict is both legitimized and managed (Dagnino 2011). Solidarity enterprises participate in the formulation of public issues according to a political approach that recognizes the role of public spaces in which citizens can express their concerns and ask their questions (Coraggio et al., 2015: 244). These public spaces are crucial for the revival of citizen involvement that representative democracy alone cannot ensure (ibid.).

Rising inequalities and the processes of peripheralization are leading to an increasing political discontent that right-wing populist parties could successfully mobilize. At the same time, participatory democratic social and solidarity economy initiatives are also emerging in Central and Eastern European rural peripheries. These initiatives may have the potential to counteract the rise of right-wing populism. Social and solidarity economy initiatives can serve as intermediate public spaces in which the voice of the marginalized can be heard and amplified. Only citizens whose autonomy status is recognized, and whose capacity is developed, can participate in political decision making. Through an in-depth study of internationally selected rural social enterprises, this research aims to better understand the potential social and solidarity economy initiatives have to empower their stakeholders. Autonomy and empowerment through an intersectional lens are key concepts in this endeavor. Shedding light on the empowerment capacity of rural social enterprises may enhance the understanding on how, and to what extent, rural social enterprises can mobilize people living in precarious conditions in peripheralized areas.

Spaces provided by social and solidarity economy initiatives can become forums for deliberation and co-management aimed at developing economic democracy and becoming the seeds of a solidarity economy movement in CEE. Therefore, this paper aims to answer the following question: How do SSE initiatives address the everyday material challenges and political discontent of people living in peripheralized villages?1 A critical realist2 (Bhaskar 1978, Bhaskar 1983; Brewer 2000; Gorski 2013) ethnography (Porter 2001) has the potential to produce knowledge that can contribute to transforming the precariousness of life that dominates the world we inhabit (de los Reyes and Mulinari 2020: 190) and help in better understanding how participation is reached, practiced, developed and increased in rural areas despite peripheralization and rising right-wing populism. This approach aims to fit today’s call for ethnography to be more directly relevant to policy and to improve the lives of those researched (Schneider 2002 Hörschelmann and Stenning 2008: 354). Acceptance of the reality of social structures (such as racism, patriarchy, and globalized capitalism) entails the rejection of methodological individualism as a sufficient mode of explanation. Similarly, methodological situationalism is seen as providing too weak a conception of structure (Porter 2001, 241). For this reason, within critical realism, ethnography is not a methodology, but a collection of methods. Ethnographic techniques of data collection can be used within the model of critical realism to investigate the nature of generative structures through examination of social phenomena (ibid.: 242). Intersectionality, which captures how oppressions are experienced simultaneously (Carasthatis 2014: 307), is used less as a research method and more as a heuristic to interpret the results of this research (Carasthatis 2014: 309). Feminist researchers have argued that, beyond seeking to level the playing field towards research participants through the application of empowering methods, bottom-up approaches, etc., strong reflexivity is needed that “requires the researcher to subject herself to the same level of scrutiny as she directs to her respondents” (McCorkell and Myers, 2003: 205 in Hörschelmann and Stenning 2008: 351). Giving up the myth of meritocracy (McIntosh 1992), and conducting self-reflection on white, male or any other privilege is of crucial importance in research and in any local development project (Oprea and Silverman 2019). Ethnography can also be useful to challenge the certainty with which transition theorists have applied western concepts to varied post-socialist contexts and with which they have assumed the possibility of a linear transgression from one clearly defined system to another (Hörschelmann and Stenning 2008: 356).

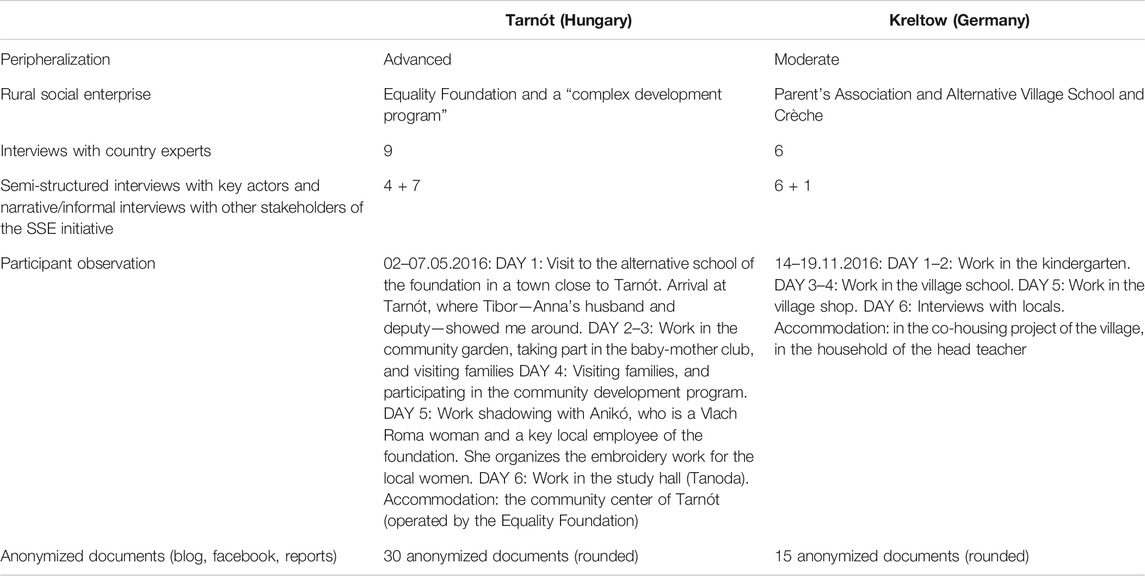

To better understand how SSE initiatives may address the everyday material challenges and political discontent of people living in peripheralized villages, SSE initiatives emerging in the context of moderate (from Germany) and advanced (from Hungary) peripheralization are compared (Table 1). Expert interviews have been conducted prior to selecting the rural social enterprises for the case studies to gain a better knowledge of the overall picture regarding peripheralization and social enterprises on a country level. The expert interviews were supplemented with focus group discussions: one in Germany and one in Hungary (Mihály 2021). The two case-study social enterprises aim explicitly to practice and develop participative decision making3. Even though the two initiatives are similar in terms of their participatory approach, their stakeholders are marginalized to a different extent. In the first case a complex development program has been developed for and by the Roma and non-Roma inhabitants of a Hungarian village undergoing advanced peripheralization. Considering that, through processes of peripheralization, the symmetric structures of reciprocity (Polanyi 1971b) have already been destroyed in the community, the key initiator of social and solidarity economy, who is a representative of a local foundation, comes from outside of the village. In the second case, cheap land and the proximity of nature in a village of a peripheralized region of northeastern Germany provided an attractive environment for ecologically-minded people searching for a rural alternative for their urban lifestyles. The newcomers (“Zugezogene”) have created an alternative village school organized around the idea of environmental sustainability (Table 1).

TABLE 1. Case studies: SSE initiatives in the context of moderate and advanced peripheralization Source: the author’s own illustration.

Data was collected through semi-structured interviews with country experts (15), the key actors of SSE initiatives (10), and other stakeholders of the rural social enterprises (such as Roma and non-Roma inhabitants of the village; Roma leaders; inhabitants using the services of the social and solidarity economy initiative, such as childcare, alternative school or baby-mother club facilities; and the employees or volunteers of the initiative), participant observation (a one-week-long stay and work on the spot), formal and informal interviews with the stakeholders of the case-study rural social enterprises and documentary analysis (e.g. blogs, facebook pages, and official founding documents). The documentary analysis was useful not only to gain initial knowledge before the key actor interviews, but also to acquire in-depth knowledge of financial and governance issues within the case-study social enterprises through triangulation with data from interviews and participant observation (Table 1). Qualitative data analysis software (ATLAS.ti 8) was used for the analysis of all transcripts, field notes and written documents of the case-study social and solidarity economy initiatives.

The one-week-long stay provided an opportunity to comprehend the unique perspective of the local stakeholders. Most of the key actors of the SSE initiatives were used to an interview situation. Working together with the other local stakeholders (e.g. the “beneficiaries” of social enterprises) helped me to make them comfortable with an informal interview situation and also helped to better understand their everyday experiences of (counteracting) peripheralization and the role of the SSE initiative in their life. From the perspective of empowerment, Romungro Roma are one of the most oppressed groups in the Hungarian case-study village. Even though I had informal talks with a Romungro Roma woman on the spot, I did not manage to visit a Romungro Roma family in their home. During my fieldwork it was possible though to visit five Vlach Roma households, one Romanian Hungarian household, and one Ethnic Hungarian household as well. I also managed to participate in two community building events, which were attended by Romungro Roma families too. In the German case-study village, I visited a co-housing project in which a few of the key stakeholders of the SSE initiative were living. I also spent a few days in the local kindergarten and school set up by the newcomers and visited the local shop and pub maintained by original inhabitants.

As an ethnic Hungarian, a Central and Eastern European, and a woman, I had different challenges and opportunities during my fieldwork. In the Hungarian case in which the Gypsy-Hungarian differentiation (see Kovai 2018) is implicitly aimed to be overcome locally (Mihály 2019), it was easier to engage in discussions both with Roma and non-Roma than in other Hungarian villages I had formerly visited. However, the fragmentation of the local Roma society limited the scope of this research. It was easier to build up a connection with the Vlach Roma families, as the local key stakeholder of the foundation is a Vlach Roma woman. It was more challenging to visit Romungro families. A longer stay would have helped, but in that case I would have been able to study fewer social enterprises. The experiences I had in Hungary regarding the state oppression of civil society during state socialism and its consequences for civic engagement helped me to relate more easily to my East German interview partners when they brought up the issues they faced in setting up their social enterprises. My interest in environmental movements helped me in connecting to most of the newcomers of the German case study. Being able to communicate in German was also beneficial in the field. My hosts and interview partners appreciated that I approached them in their native language. Being a woman helped me to connect to key actors, who were predominantly women both in the German and the Hungarian case-study villages. Participating in particular programs, such as a baby-mother club during my stay within the Hungarian case, clothing swap (“Kleidertausch”), or community sauna sessions for women within the German case were easier, or sometimes only possible, as a woman.

To better understand how SSE initiatives may serve as seeds for a solidarity economy movement in CEE through addressing the everyday material challenges of people living in peripheralized areas 1) the relationship between SSE initiatives and peripheralization will be elaborated upon (key actors, “beneficiaries”, Table 2), 2) the perspective of the “subaltern” (Table 2) will be brought in, and the relationship between SSE initiatives and 3) participatory, economic and 4) representative democracy will be elaborated upon.

TABLE 2. Case studies: SSE initiatives in the context of moderate and advanced peripheralization Source: the author.

Peripheralization manifests differently in each of the case-study villages, and this also leads to different individual (livelihood) and collective (organizational) strategies in counteracting processes of peripheralization. Two contrasting cases of peripheralization (moderate and advanced) have been compared to better understand the autonomy status and mobility strategies of the inhabitants of differently peripheralized villages and the contexts in which SSE initiatives emerge.

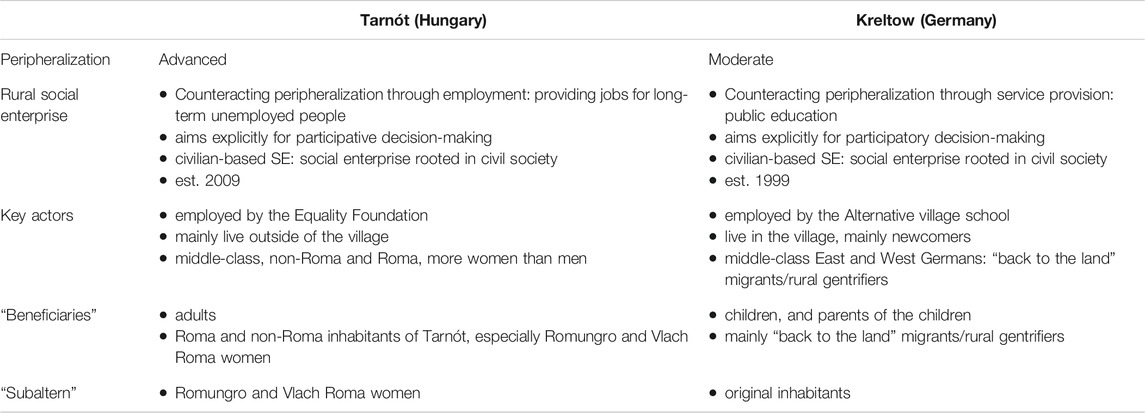

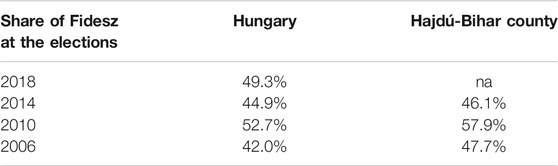

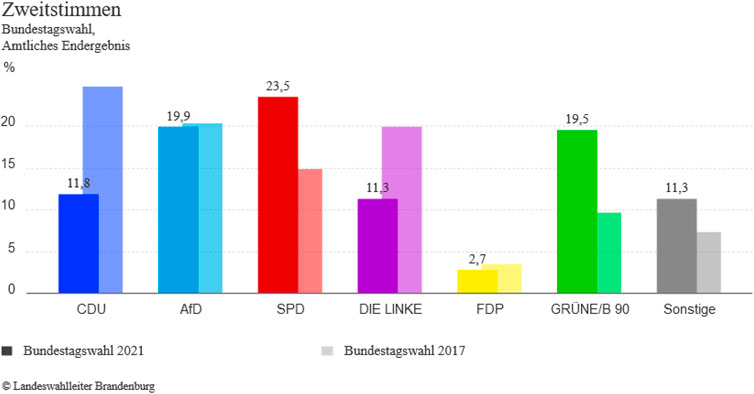

Uckermark, a historical region in northeastern Germany and a district in Brandenburg state, is one of the losers of post-socialist transformation in East Germany. Even though large farm enterprises continued to dominate the agricultural sector after reunification, the high degree of mechanization resulted in a significantly diminished workforce demand. As a result, the number of employees in agriculture decreased from 11,500 to 4,000 between 1991 and 2001 in Uckermark (Beetz et al., 2005: 300). Its economy is performing at a low level (Beetz et al., 2005), its inhabitants face one of the highest unemployment rates in Germany, and the purchasing power in the region is 30 percent below the German average (Beetz et al., 2008: 300). Livelihood challenges have resulted in a high level of selective out-migration. The region is one of Germany’s most heavily shrinking regions (Beetz et al., 2008: 298). The AfD was successful in mobilizing the voters of Uckermark. The share of AfD voters was higher in the Uckermark-Barnim region than at the federal (equal in 2017) and national levels (see Table 3).

TABLE 3. Share of AfD at the Federal election, source: the author, based on https://www.bundeswahlleiter.de (October 23, 2021).

Kreltow, my case-study village with around 300 inhabitants, is located in Uckermark. The reunification and the accompanying economic crisis were devastating for the village. Its largest employer during state socialism, an agricultural cooperative (LPG) employing 150 people (G1_D6), went bankrupt, and in the 1990s two privately-owned organic farms were founded from the LPG in which considerably fewer (18) people are employed (Interview_G1_I7).

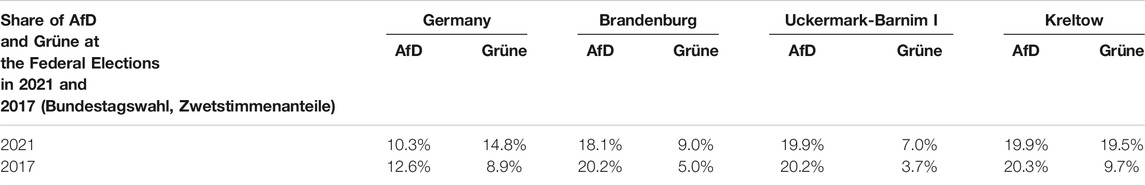

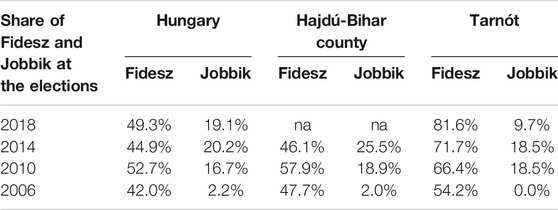

Tarnót (H2, altered name) is a small settlement with 300 inhabitants (47 percent fewer inhabitants compared to the number in 1970, HCSO 2011) in Southeastern Hungary, close to the Romanian border. The village is located in one of the 33 least privileged micro-regions of Hungary (Government Decree, 2007). This village has one of the highest deprivation indexes among all of the Hungarian settlements (Koós 2015), meaning that people living here have very limited access to public goods and little chance for social mobility. The main employer during socialism was an agricultural cooperative, which went bankrupt after the change of the regime. Fidesz was successful in mobilizing the inhabitants of Hajdú-Bihar county from Southeast Hungary for the elections. In 2006, 2010, and 2014 the support for Fidesz was higher regionally in Hajdú Bihar county than its support nationally (Table 4).

TABLE 4. Share of Fidesz at the national elections (list voting), source: the author, based on https://www.valasztas.hu/ (October 23, 2021).

Kreltow is a case of moderate peripheralization. The negative spiral of peripheralization could not only have been stopped, but could have been reversed. Despite the high unemployment rates, processes of selective out-migration could not only have been limited, but through the in-migration of mostly young, middle-class families with children, the process of shrinking could have been turned back (blog entry by the inhabitants of the Kreltow co-housing project, G1_D3, 2003). Shortly after the reunification of Germany an organic farm was set up in the village, which attracted “back to the land” migrants (Halfacree 2006). The newcomers came both from East (from East Berlin) and West Germany (e.g. from Baden-Württemberg), and mostly from urban areas, to start a more environmentally conscious life in the village. The cheap land prices and available space for experimentation were attractive to them.

They were not satisfied with the herbartian pedagogic methodology (hierarchic, frontal education, based on the pedagogy of punishment and reward) of the local school, which was rooted in the state-socialist German Democratic Republic, and therefore founded a Parents’ Association and an Alternative Village School and a Kindergarten in 1999 (G1_I4). In Germany, the constitutional law rules out a state monopoly on education. The right to establish privately-maintained schools, which are supported and supervised by the state, is expressly guaranteed by the Basic Law (Grundgesetz, 2018, Art. 7, Paragraph 4—R1) and, to some extent, by provisions in the constitutions of the individual Länder (Lohmar and Eckhardt 2014, 33). However, privately-maintained schools have to sustain their operation using less public support than state schools. The governmental support covers only 50–60 percent of the actual costs of German privately-maintained schools. Based on research in 2011, privately-maintained schools in Hessen face the most challenges. Here the gap between the real costs and the costs covered by the state was 5,200 EUR per student in 2007 (Cologne Institute for Economic Research 2011). This gap was the smallest in Brandenburg, with 1,800 EUR per student. Despite demonstrations, this gap grew in Brandenburg by 17,65 percent in 2012 (Strang 2011). This is the context in which the Parents’ Association (our case-study SSE initiative) maintains a Village School and a Kindergarten. The main aim of the alternative school is to contribute to the education of an environmentally more conscious generation through developing children’s and students’ creativity and critical thinking. The alternative village school attracted further newcomers to the village (G1_1, G1_I2, and G1_I7). In contrast to other settlements in the Uckermark region, the birth rate is high in the village. There is a village shop, two restaurants, a crèche, a school, six handicraft businesses, an organic farm, a psychosocial care facility, and other small businesses (G1_D3, 2003). The village is also rich in cultural and community activities. They have a regionally-known Carnival, a dance group, a fishing association, a harvest feast, a fire fighters’ association, literature evenings, theater projects, two rock bands, a drum group, and a sports festival (ibid., Field_notes_G1). As the organic farm and the alternative village school was successful in attracting people and funding for local development, the process of deperipheralization started. Reflecting on the ongoing processes of deperipheralization, one of the founders of the Alternative Village School even questioned whether their village is a good case study for peripheralization (Field_notes_G1). Kreltow and the SSE initiative that was set up in the village show how local agency may counteract certain aspects of peripheralization (e.g. access to quality education). Due to the alternative village school, the village became represented in the media as an idyllic rural place for raising children, with a good family life and neighborly relations, and became attractive to young upwardly mobile families with children. As a result, it became challenging to buy a house in the village (Interview_G1_1, G1_I2, and G1_I7). It would be interesting to elaborate further the way in which rural gentrifiers may create displacement pressures that impact on younger residents and potentially influence the supply of housing for subsequent waves of gentrification (on rural gentrification: Smith et al., 2019; Stockdale 2010).

Tarnót is a village undergoing advanced peripheralization, and is characterized by mobility flows opposite to the one in Kreltow. Due to selective out-migration, the village has already lost most of the inhabitants who had the capacity for a common interest representation. Roma are overrepresented in the village; 70 percent of the inhabitants of Tarnót declare themselves Roma (Equality Foundation 2016; H2_D9). Predominantly Romungro, and in a smaller proportion Vlach Roma people live in the village. Romungro Roma are indigenous inhabitants and Vlach Roma are newcomers, who moved to the village more than 10 years ago (Equality Foundation 2016; H2_D9). Middle-class, non-Roma families with children are completely missing from the village. Similar to other areas undergoing advanced peripheralization, as work in the formal economy is not available locally, the inhabitants of Tarnót are forced either to leave the village for work or to secure their livelihood (social reproduction) through informal economic activity (e.g. usury and sex work) (Equality Foundation 2016; H2_D9, 24, Field_notes_H2). This further increases their dependency and vulnerability. The Equality Foundation, which has run an Art School since 2000 for underprivileged, mainly Roma, pupils in the neighboring town, decided to introduce a long-term “Complex Development Program” in Tarnót in 2009. The Foundation purposefully selected Tarnót, a village undergoing advanced peripheralization, as an extension of their art-based education4 to show that, through a capability-based approach and community development, even the most marginalized villages can be developed. The Foundation offers full-time employment for the locals in their community garden and food-processing workshop and an opportunity to gain extra income through casual work (doing embroidery).

The long-term aim of the Foundation is to make their local stakeholders independent from them. The leader of the community garden5 believes that if more people from the younger generation started to work in the community garden, then this would help them to achieve this aim (H2_I3). However, attracting people from the younger generation is challenging (H2_I3), as in order to escape multiple dependencies the younger people who can leave the village do so. Even though the Foundation aims to reduce the dependency of the locals on them, their relationship with the locals is embedded in unequal power relations. People living under the conditions of advanced peripheralization are dependent on the development organization (Equality Foundation) for access to material goods (e.g. pharmaceuticals, and school supplies for their children) or in terms of mobility (leaving the village for day trips): “We talk about the equipment for starting the school as well [the Foundation donates a school starting package for the children from the village yearly], everybody asks whether exercise books and pencils are arriving with the donations. And they ask about something that we have not talked about for long time now, the day trip for adults. Because they understand, of course, that we take the children on trips. But they want to participate in such a trip as well. Because they cannot get anywhere from here either. We fix the time, talk about the place and the program. They are cheerful as the team meeting ends.” (Blog entry 2016, H2_D5) While counter-cultural migrants (“back to the land” migrants) were free to decide where to live, the inhabitants of Tarnót became locked into a marginalized rural area.

Class, ethnicity and place of residence influence the autonomy of the stakeholders of the SSE initiatives. Migration is an individual strategy to escape multiple dependencies in a village undergoing advanced peripheralization. In order to have access to paid work, a 43 year-old Vlach Roma man decided to move to Vienna for 5 months to earn income as a taxi driver. His experience reflects on how his autonomy status was neglected by his employers: “Lets tell the truth, migrant workers are very much exploited abroad. I used to work as a taxi driver for 22–24 h, I was so tired that I fell asleep at every red light. It was worth it, because I used to send 100,000 HUF (around 275 EUR) back home each week.” (Interview_H2_I4).

Sex work is a reality that the women and girls of Tarnót face. Some women and girls of Tarnót were trafficked to Germany and forced into sex work (Field_notes_H2). The Equality Foundation has so far framed sex work as the shortcoming of the socialization of local women: “The daughters of the women whose father sent them out every night to “go out and earn money” turn to prostitution as well.” (Blog entry 2017, H2_D24) Kóczé (2011, 83) calls for an intersectional approach to better understand the complex nature of violence against Roma women. “Since the early 1990s, women and girls have been trafficked from Central and Southeast European countries to work as forced prostitutes in the European Union. To treat this as merely a function of gender discrimination, while ignoring the ethnic, geopolitical, economic, and class dimensions of the problem would ultimately result in inconsistent analysis of its root causes and effects and would not yield appropriate measures.” At the least, identifying the countries of departure gives an indication of the degree of gender discrimination and the political and economic situation of the given country. Nevertheless, it is important to identify, for instance, why women from certain countries and from certain regions of their country make up the majority of forced sex workers in the EU countries (Kóczé 2011: 83).

In contrast to racialized and gendered lower and working-class Roma migrating to the city from rural ghettoes, the autonomy status of middle-class non-Roma counter-cultural migrants moving from cities to rural peripheries is acknowledged:

“personally I wanted to get out of Berlin to the countryside. And with the aim of moving out of Berlin, we bought a house with like-minded people, here in Kreltow [as part of a co-housing project] where Anette [the current principal of the alternative village school] now lives. And then there were people who were dissatisfied with the state schools here and wanted to start their own school. Then they persuaded me to become a teacher there at some point in the future. I also liked the idea (…) I did not like the system before, so I came up with the idea of doing something different. And then we needed an idea, some concept, with which we can run our own school (…)” (Interview_G1_I3).

Even if autonomy as a status was acknowledged for a white, middle-class man from East Berlin, autonomy as a capacity in advocating his rights as a citizen was missing for him as he was socialized in the state-socialist GDR: “Two women from West Germany were particularly important at the beginning. They had way more civic courage, with the Ministry (…). This for us East Germans (‘Ostler’) was incredible, they were different, that was good.” (Interview_G1_I3).

The social and solidarity economy initiatives are carried out in two contrasting cases of peripheralization. Kreltow, a village undergoing moderate peripheralization, attracted middle class “back to the land” migrants, who as a team had autonomy both as a status and as a capacity that helped them to realize their SSE initiative, through which they could deperipheralize their village. Tarnót, a village undergoing advanced peripheralization, functions as a “ghetto” in which marginalized Roma are locked in. Even when inhabitants of villages undergoing advanced peripheralization try to escape from the multiple dependencies, their autonomy status is neglected.

In the case of the Equality Foundation, Roma women can be considered as “subaltern”. The post-socialist transition or the “capitalist reintegration of Eastern Europe” has had devastating effects for the Roma, who, even before the transition, used to belong to the most vulnerable section of the working class in economic, cultural and political terms” (Themelis 2016, 7). There is a biopolitical border between the white and the racialized working class that prevents class solidarity among the subordinated precarious populations in Europe (Kóczé 2016: 46), and which manifests in Gypsy-Hungarian differentiation in village societies (Kovai 2018). Instead of promoting solidarity and defending the public institutions and demos, the system covertly promotes the racialization and collective scapegoating of Roma, which therefore polarizes revolt against neoliberal structural oppression (Kóczé 2016: 46). As a result, Roma men are subjected to an ethnic gap and Roma women are subjected to both an ethnic and a gender gap in education and in employment (Kertesi and Kézdi 2010; Cukrowska and Kóczé 2013). In the case of the Alternative Village School and Crèche, inhabitants living in the village prior to the reunification of Germany can be considered as “subaltern”, as they are the ones who have been most influenced by the post-socialist transformation and the related economic crisis (Hörschelmann 2001).

The relationship between the newcomers of Kreltow and the original inhabitants was highly conflicted in the 1990s (Interview_G1_I7, G1_6, G1_I1, and G1_I2). It was connected to the privatization of the former LPG and the devastating job losses that it generated within the local economy. The situation has eased, as the alternative village school developed economic connections to the village pub and the village shop, which are maintained by inhabitants who lived in the village prior to the reunification of Germany (Field notes_G1, Interview_G1_I1, G1_I2, and G1_I6). Food for the village school and crèche is sourced from the local village pub. The village shop was probably saved from closing down due to the cooperation between original inhabitants and newcomers, in which many newcomers connected to the alternative village school and crèche became engaged. Among the staff of the alternative village school and crèche, the ratio of newcomers is higher in the higher prestige positions (e.g. teachers and kindergarten teachers) and lower in the lower prestige positions (e.g. cleaning staff). The newcomers are overrepresented among the parents within the Parent’s Association and among the children benefitting from the alternative village school and crèche. A reason for this, beyond certain original inhabitants being skeptical about the education methodology within the school (Interview_G1_I6, G1_I1), might be that the school fees which the association uses to supplement the gap left by the reduced financing for the privately-maintained and state-sustained schools is not affordable to all the inhabitants in the village (Interview_G1_I7).

Without identifying themselves as a Roma feminist organization, the Equality Foundation has consciously focused on women in local development. “Through our family visits it became clear that we can build better with women (…) in Tarnót. They were more open, and we were able to build up a more intimate relationship with them. It also helped that they were happy to participate in craft activities. For this reason, we have been relying on them in regards to the development of the village.” (Equality Foundation 2016, 29, H2_D9) The reasoning behind their decision is connected to the role women play in the social reproduction of their households due to care work: “women can be better involved in the interests of their children, and [they] are expected to cope with the crises within the family, they are expected to provide food for the family, and ensure the everyday organizational part of family life.” (Equality Foundation 2016; H2_D9).

The Foundation became an ally of the local Roma women and mobilized its social capital to attract financial resources to channel them for local development projects. To tackle the complex challenges related to advanced peripheralization, the Equality Foundation introduced a targeted community development program (funded through the Norway Grants) in the village between 2014 and 20166, and selected 30 women as partners within the community development project: young, senior, newcomer, indigenous villagers, Romungro, Vlach Roma and non-Roma women. Based on the problem map, the Foundation has identified fields which connect to the local women the most, and, based on their collectively developed beliefs, hinder change the most. Together with the 30 women from relatively different social backgrounds, the Foundation formulated three modules of community development. The modules build on each other and go from the “easier” to the “more challenging”: 1) Household knowledge, 2) Conscious family planning and childcare, and 3) Development of skills, knowledge transfer and supportive cooperation in the field of domestic violence (Equality Foundation 2016, 33, H2_D9). While the module on “household knowledge” addressed the development of collective autonomy (see Asara et al., 2013) through bringing together the local women with different ethnic and socio-economic backgrounds, the module on family planning and domestic violence more closely addressed issues of individual autonomy. Addressing domestic violence proved to be the most challenging field: “The field in which we have not succeeded, so far as the problem is rooted more deeply than we thought, is strengthening women’s status in the family through the community. We do have to work on this in the future, because it is important for girls not to incorporate the behavioral pattern that accepts aggression, and boys should not incorporate the role of an aggressor.” (Equality Foundation 2016, 75–76, H2_D9).

To tackle the challenge of locally (non-)available jobs and the care work obligations of women that hinder their employment in the formal labor market, the Foundation trained the local women in a needlework technique. Through needlework (embroidering the drawings of their children), the women of Tarnót could get access to paid work and extra income (Interview_H2_I1, Field_notes_H2). As there is limited availability of paid work locally, in addition to the Roma women, non-Roma—mainly elderly and some middle aged women who live below the subsistence level—became interested in earning extra income as well. Working together has developed the relationship between Roma and non-Roma in the village (Equality Foundation 2016, 30, H2_D9).

Aggressive verbal communication and physical aggression characterizes the life of many families in Tarnót (Equality Foundation 2016; H2_D9) and beyond. Women become victims of domestic abuse: “Many times, we are aware of their domestic abuse, we often see how tensions of privation are lowered on them, and we also feel that in this case they are left to themselves.” (Equality Foundation 2016; H2_D9). The Foundation frames women’s inherited socialization as a key challenge: Those girls whose mother tolerated slaps in the face will endure domestic abuse without a word.” (Blog entry 2017, H2_D24) Outside of Tarnót, domestic abuse characterizes the everyday life of non-Roma women as well. The first book documenting the gender aspects of domestic abuse in Hungary and pointing to the shortcomings of the courts in dealing with the treatment of this form of violence against women was released in 1998 (Harangi 1998; Krizsán and Roggeband, 2018).

The Equality Foundation is more focused on addressing the everyday material challenges of the inhabitants of a village undergoing advanced peripheralization. In terms of economic democracy, shared ownership has not yet been realized as the foundation, in which local Roma are not represented, is the owner of the means of production. The Parents’ Association is less focused on addressing the everyday material challenges of people living in the village prior to the reunification of Germany. Their association is the owner of the village school and crèche, but among the members and in the school and crèche, the original inhabitants are underrepresented.

Both participatory democracy and economic democracy are necessary for solidarity enterprises to realize their emancipatory potential. Therefore, the internal governance and ownership of the two case-study SSE initiatives will be elaborated in this section.

The aim of the Equality Foundation is, despite the structural constraints, to enhance the capacities of the inhabitants of Tarnót to participate in decision-making processes and to advocate for their interests: “The main aim of the foundation is to empower a social group, which for generations has not been affected by the educational system or by work in the formal economy. The aim is to enable these people to organize themselves: to stand up for their life and for their community, to solve their own problems, to communicate with each other, to plan, to self-assess and to exploit opportunities.” (Blog entry 2016, H2_D5) Due to the structural constraints, they consider the capacity-development of the inhabitants of Tarnót a longer process, possibly taking 20 years. While the Foundation has a strong focus on the capacity development of the locals, institutional racism is only implicitly thematized (e.g. regarding educational segregation, blog entries by the founder of the Equality Foundation in 2010, 2011, and 2014, H2_D28, H2_D29, and H2_D30). While the Foundation has a philosophy of being in a partnership with their local stakeholders, who live under the circumstances of advanced peripheralization, blogposts exist, even in the field of educational segregation, in which their local stakeholders are infantilized: “they do not understand and cannot understand what is good for them and their children in the long run. They only have experience of living here [in the segregated area], where values and relationships are influenced by poverty (…)” (blog entry by the founder of the Equality Foundation). The costs of social reproduction are particularly high in Tarnót, consuming most of the time and energy of the locals. In the context of advanced peripheralization, the autonomy status of the inhabitants of Tarnót is not recognized by the decision-makers either as locals, particularly Roma women, have been excluded from decision-making processes.

One of the main platforms for involving the locals in the decision-making processes is the team meeting, which was introduced in 2013. Due to both public and private financial support, including international foundations (Non-profit report of the Foundation, 2015, 2016, see H2_D27), the Equality Foundation was able to employ seven people from the village who belong to the Romungro, Vlach Roma and non-Roma ethnic groups. Every official employee of the Equality Foundation, excluding those who work there as volunteers, may participate in the team meetings. These meetings differ from typical team meetings as not only work-related issues are discussed there (Field_notes_H2). These meetings are also used to improve the skills of the inhabitants of Tarnót for participation. Every participant needs to take notes about what happened in the previous week in his/her field. The founder of the foundation describes a team meeting in her blog:

“We had a team meeting today. Every Friday afternoon we sit down and talk about the previous week. This happens in a smooth and organized way. I look at them as they routinely take their little black hard-cover booklet and go through who did what, day by day. It is great to see the progress they have made in this field. Sometimes I ask for some more details or I compliment them on a successful area. They are proud and happy. So am I. Some read out aloud what they wrote. Some just check their notes and talk more freely about their past week. And there are some who read out to their child after every single working day what they did during the day, and now ask me to read aloud what they know anyway. No one giggles about it; we have talked about it before. And the rule is the rule. The booklet must be run, even for those who have challenges with writing. Based on their job description, this is an expectation towards them. In such cases I really felt it was worth it. I feel as they psychologically grow stronger and stronger. I feel how their job, the responsibility of their job develops them: in everything, in purposefulness, in communication or in cooperation. I feel how they function better and better as a community. The team meeting is no longer about picking at each other. In fact, they laugh together a lot now at good things. We plan the next week as well (…) decisions are made, the others’ suggestions or requests are discussed at these team meetings. Now they understand the system that we have built up together. They understand the essence of making decisions together. They understand the role of local staff, and they are beginning to understand advocacy.” (Blog entry 2016, H2_D5).

One of the limitations of this study is that the length of my field visit did not allow me to participate in a team meeting. However, during my field visit, I had a chance to talk about the team meetings with some local stakeholders of the Foundation. Rozi (altered name), a Romungro Roma stakeholder of the Foundation, appreciates that she can share her point of view in the team meeting. On the other hand, she refers to the founder of the foundation as the “boss” in one of our other conversations (Field_notes_H2). Rozi voluntarily offering herself in servitude resonates with Ferguson’s finding. Ferguson (2013) argues that for poor black South Africans offering themselves as servants is historically rooted (see how the Ngoni state functioned) and is a form of belonging to the society and is, nevertheless, better than being abandoned (Ferguson 2013: 232).

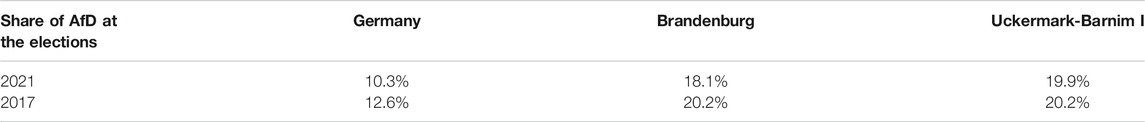

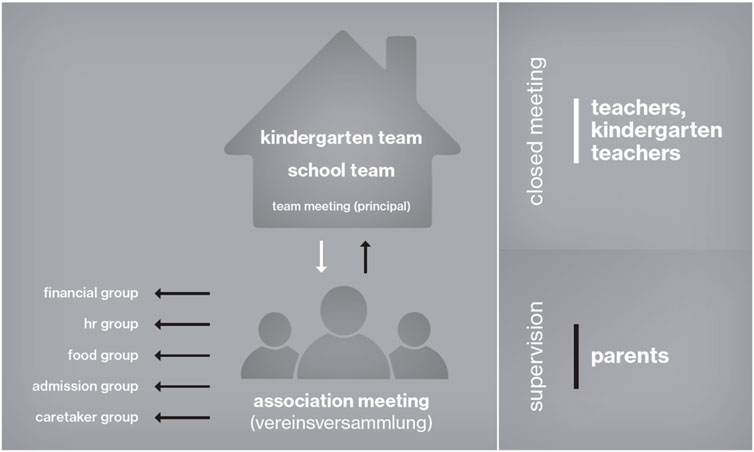

The Village School and Crèche are owned and sustained by the Parents’ Association. Every parent can become a member if they pay the membership fee, which was 6 EUR in 2016, and if they volunteer 30 h a year. Both criteria have been defined by the members of the Parents’ Association. The Parents’ Association has a sophisticated decision-making process, based on the principles of grassroots democracy7 (see Figure 2). Grassroots democracy is a tendency towards designing political processes where as much decision-making authority as practical is shifted to the organization’s lowest geographical or social level (Mihály 2018). Through school projects (e.g. the apple processing and selling cooperative) the children of the village school also learn by participating in grassroots democracy (Interview_G1_I3).

FIGURE 2. Decision-making within the Parents’ Association. Source: the author, based on the feedback of one of the main stakeholders of the village school. Designed by Tibor Szikora.

The decision-making body of the initiative is the association meeting (Vereinsversammlung). Here, everyone who is present and a member of the Parents’ Association has a vote. In addition to the “one member one vote” rule, decisions are based on consensus. All of the normal members have a quasi-veto right and the principal (Vorstand) has an official veto right. The Parents’ Association makes decisions together with the teachers and kindergarten teachers. Nearly all of the teachers are also members at the association (they often are, or were, parents too), so they participate in the decision-making on the association’s side too.