- 1Department of Political Science, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John’s, NL, Canada

- 2Department of Politics and Public Administration, Ryerson University, Toronto, ON, Canada

- 3Department of Political Science, Western University, London, ON, Canada

Since Angus Campbell and colleagues introduced the Levels of Conceptualization (LoC) framework as a measure of political sophistication, only a very small number of scholars have applied this approach to understanding how electors view political actors. In 2008, Michael Lewis-Beck and colleagues replicated this foundational study and found similar results using much more recent data on American national elections. In this brief research report, we replicate the work of Lewis-Beck and colleagues in the Canadian municipal context. Using survey data from the Canadian Municipal Election Study, we make use of open-ended responses about attitudes towards mayoral candidates to conduct a qualitative examination of the manner in which survey respondents from eight Canadian cities view mayoral candidates. Despite the relative dearth of ideological cues at the local level, we nevertheless find that a noteworthy portion of the electorate views candidates in ideological terms. Like previous work on the subject, we find that high levels of conceptualization are positively associated with turnout, education, political knowledge, and ‘political involvement’.

Introduction

The concept of ideology is central to our collective understanding of the political world. It has long been, and continues to be, a subject of intense study and debate among scholars (see Freeden and Stears 2013). The standard conceptualization of the left-right or liberal-conservative continuum is as a logical and convenient way to think about politics and elections. Indeed, ideological compatibility between voters and candidates is a well-known correlate of vote choice at multiple levels of government (Scotto et al., 2004; Sances, 2018). There is no doubting the relevance of the (albeit somewhat vague and occasionally contested) concept of ideology to our understanding of political attitudes and behaviours.

At the same time, we know that not everyone views politics through a primarily ideological lens. This much was observed in some of the earliest works in the field of voting behaviour. Campbell et al. (1960) introduced the Levels of Conceptualization (LoC) framework as a measure of political sophistication in American national elections. Within this framework, political sophistication is not centrally a question of the volume of political knowledge a citizen possesses, nor of the intellectual subtlety, or even accuracy, of the political ideas the citizen expresses (Lewis-Beck et al., 2008, p. 259). Rather, sophistication speaks principally to the degree of organization or structure that exists among the citizen’s political cognitions. From this view, the significance of ideology in citizens’ thinking about politics is that it implies the use of “high-order abstractions” (e.g., liberal, conservative, socialist, fascist) and the presence of a wide-ranging and integrated political belief system (Luskin, 1987).

The LoC approach, accordingly, classified electors on the basis of the types of factors—including ideological considerations and other abstract standards—that came to mind when survey respondents were asked what they liked and disliked about political parties and presidential candidates in open-ended questions. While some respondents did reference ideological considerations, others mentioned a host of different factors, such as the potential benefits (or harms) that groups within society might gain (or suffer) under alternative governments, or the previous performance of contenders for office (including changes in society that might be attributed to candidates or parties). Campbell et al. also found that many respondents did not make reference to any of the above considerations, perhaps mentioning only partisanship, the personal characteristics of candidates, or indicating they had no likes or dislikes at all. Such individuals were considered the least sophisticated, occupying the “lowest” LoC category. In summary, then, from highest to lowest, the LoC categories identified by Campbell et al. (1960) were: 1) Ideology (which, as we discuss below, was broken into two sub-categories), 2) Group Benefits, 3) Nature of the times, and 4) No issue content.

Because Campbell et al. (1960) understood the LoC to be an indicator of political sophistication, they also explored the correlates of the measure. In particular, they focused on two measures that ought to relate to political sophistication: education and political involvement. As expected, they found that placement in an LoC category, when the categories were ordered from least to most ideological, did correlate positively with the other measures.

A modest number of more recent studies on American national elections have conducted similar analyses (Field and Anderson 1969; Verba et al., 1978; Lewis-Beck et al., 2008), demonstrating clearly that electors can experience the same political environment, but focus on very dissimilar factors when thinking about political actors. Though some have disputed its value as a valid indicator of political sophistication (Smith 1980; Cassel 1984), the LoC framework can nevertheless provide invaluable insight into how electors view politics and politicians. A particularly noteworthy modernization of Campbell et al.’s work is Lewis-Beck et al. (2008). In The American Voter Revisited, the authors update and replicate much of the original analysis from The American Voter, including the LoC. In that work, the authors outline the logic of the LoC, describe its distribution within the population, and consider its relationship with a number of political attitudes and behaviours. Their findings largely mirror those of Campbell et al. from decades earlier.

There is, however, a noteworthy limitation in the relatively small existing literature on the LoC: it is overwhelmingly based upon American national elections. That the approach has been so rarely applied is understandable, given that the data collection involved is time- and labour-intensive. Relatedly, the measurement approach is qualitative in nature: whereas quantitative approaches dominate in the field of political behaviour, Campbell et al. used trained human coders’ qualitative assessments of electors’ responses to assign them to LoC categories. Nevertheless, there are valuable reasons to invest resources in the approach. At the most basic level, it is critical to establish LoC’s correlations with its presumed surrogates, such as education and political knowledge, in contexts beyond the United States and below the national level. These variables substitute for political sophistication in countless pieces of political behaviour research. The value of political knowledge measures, for instance, is partially premised on their assumed association with the organization of citizens’ political beliefs (cf., Barabas et al., 2014, p. 840). Yet, while the assumption that political sophistication and knowledge are closely entwined has travelled widely, direct evidence of the connection is mostly found in a handful of analyses of American samples. Thus, an examination, in a novel setting, of the correlations between LoC and its presumed correlates will help establish more broadly the construct validity of these correlates as measures of political sophistication. More generally, developing an understanding of the type of factors that voters focus on in a variety of contexts can have implications for the study of many important topics, including but not limited to vote choice and election outcomes, campaign strategies, (social) media use, and political heuristics.

This brief research report replicates the work of Lewis-Beck et al. (2008) in the Canadian municipal context, using data from the Canadian Municipal Election Study (CMES), a large-N survey of electors in eight major Canadian cities. While replication studies can be worthwhile for their own sake, the unique nature of Canadian local elections means that there is particular value in adapting this approach here. There are many ways in which these contests are different from national elections, but two features make the study of the LoC at the local government level in Canada especially worthwhile. First, local elections tend to be low information affairs; media and voters alike devote less time and energy to local contests than they do provincial and federal affairs (Lucas and McGregor 2021; McGregor et al., 2021). As a result, there tends to be significantly less information readily available for electors to collect and process when formulating opinions of candidates. Second, politics in most Canadian cities is non-partisan in nature. Where parties do exist, they tend to be either leader-centric or short-term in nature, and municipal parties do not match those that exist at other levels of government. The absence of a traditional partisan heuristic, coupled with a generally low-information environment, means that there is a scarcity of ideological cues for voters to pick up on.1 Understanding how the LoC framework applies in this context will therefore shed light on several aspects of local politics, non-partisan politics, and the Canadian political environment. In particular, in the LoC framework, ideological evaluations are considered to be the ‘highest’ level of conceptualization. The absence of ideological cues might conceivably have a significant effect upon the way local candidates are evaluated, and thus upon the distribution of the LoC in the population. At the same time, there is value in considering who, in the relative absence of such cues, is able to evaluate candidates in terms of ideology. With low information levels and a lack of partisan cues, discussing candidates in ideological terms is undoubtedly more challenging than in other settings. Put another way, Canadian local elections provide a unique context in which to evaluate the relationship between the LoC and the aforementioned correlates of sophistication.

After detailing our methodology for operationalizing the LoC, this replication study performs two tasks. First, it maps out the distribution of LoC among Canadian municipal electors. Second, we consider whether the LoC are related to the same politically relevant variables considered by Lewis-Beck et al.: turnout, education, knowledge, and involvement (all of which might reasonably be expected to be related to a measure of political sophistication). We find that voters are indeed relatively unlikely to refer to candidates in ideological terms in the local context. However, the relationships between the LoC and the other variables of interest hold in this new context.

Methods

In this replication study we use Lewis-Beck et al. (2008) work as a point of comparison, given it is much more recent than the original work on the subject. Using data from the 2000 and 2004 American national elections, the authors found that the smallest LoC group contained ideologues, at 19.9%. The “group benefits” category was the largest, at 28.2%, followed closely by the “nature of the times” category. The “no issue content” group made up the remaining 24.1% of respondents. Lewis-Beck and colleagues also found that respondents with higher levels of conceptualization were relatively more likely to vote, and that the LoC was positively correlated with education, political knowledge, and political involvement. Our goal here is to see how these findings compare to what we find in the Canadian municipal context.

Similar to Lewis-Beck et al., we make use of a set of open-ended qualitative questions from the Canadian Municipal Election Study. The large-N survey includes responses from electors in eight large Canadian municipalities (Vancouver, Calgary, Winnipeg, London, Mississauga, Toronto, Montreal and Quebec City). Two-wave surveys were fielded during the municipal elections in these cities in 2017 and 2018.2 The average number of respondents in each city was just over 1,800, for a total sample size of 14,438. Due to the time and resource intensive nature of our coding process, 500 cases were sampled randomly from each city for this study, for a total N of 4,000.

Respondents were asked if there was anything that they liked about the top two mayoral candidates in each city, and they were presented with an open-ended text box in which to type their answer (they could also reply that there was nothing that they liked). They were also asked if there was anything that they disliked, again with an open-ended box provided. These questions were intended to approximate the American National Election Study interview questions, although we recognize that online survey questions are quite different from the in-person interview responses that were utilized by Lewis-Beck and colleagues. While we concede that this has the potential to influence the estimated distribution of the LoC in our sample, we see little reason why this methodological difference would bias any observed relationships between the LoC and our other variables of interest.

To categorize responses according to the LoC framework we designed a coding protocol based upon discussions in Campbell et al. (1960) and Lewis-Beck et al. (2008)—see Supplementary Appendix S1 for the protocol provided to the coders.3 Consistent with past research, our LoC coding consists of four categories, with the highest level, ideology, being broken into sub-categories. We provide a brief description of each group here, as well as sample entries from actual respondents (all responses are from the Toronto study and refer to candidate Jennifer Keesmaat):

A1: Ideology: References to ideological concepts or a “broad abstract judgmental standard” (Lewis-Beck et al., 2008, p. 261) that are clearly connected to “issues”, whether policy controversies or performance considerations.

Example: [Like about Jennifer Keesmaat?] Her planning platform is progressive and would encourage modern transit and development befitting a world-class city.

A2: Near ideology: References to ideology or abstract standards that are not explicitly connected to issues.

Example: [Dislike about Keesmaat?] to far left [sic]

B: Group benefits: Associations between the candidates and perceived benefits (or costs) they are expected to deliver to (or impose upon) particular social groups.

Example: [Like about Keesmaat?] She is committed to LRTs instead of overly expensive and unnecessary short subway lines in the suburbs. She is committed to gender parity.

C: The Nature of the Times: Associations between the candidates and past performance, or expected future performance based on past experience, either generally or with respect to specific issues or issue themes.

Example: [Like about Keesmaat?] Decent city planner. Good housing plan.

D: No issue content: Valid responses that contain no identifiable issue or performance content.

Example: [Dislike about Keesmaat?] argumentative

To ensure comparability between cities, we consider two candidates from each municipality.4 We therefore evaluate data from four questions for each respondent: two “like” responses and two “dislike” responses. Trained coders assigned each open-ended response to one of the five LoC categories, using the aforementioned coding protocol. We then combined these results to assign an overall level of conceptualization to each case. Respondents were assigned to the “highest” level (where A1 > A2 > B > C > D) observed across their four responses. Three coders (each of whom coded roughly half of the responses) worked separately to place CMES respondents into the various levels of conceptualization. To test inter-coder reliability, two coders independently classified 160 of the same respondents. Their classifications agreed or were just one category apart in 95 percent of cases.5

The explanatory variables we employ are all fairly standard in the voting and political behaviour literature. Turnout is based upon a standard turnout recall question. Education is operationalized by comparing those with and without a university degree. Knowledge is based upon an index of political knowledge questions (respondents are categorized as being either above or below the median). The measure of involvement is based upon an index created from two questions, divided at the median value, following the procedure used by Lewis-Beck et al. The two questions probe how much attention a respondent paid to the mayoral election and how much of an impact respondents believe local politics has upon their lives. Note that the full text of all survey questions employed here can be found in Supplementary Appendix S2.

There are almost always limitations to replications, and while our measure of LoC is faithful to past usage, we note certain important differences between our approach and earlier work. First, as mentioned above, our data were collected online, whereas Lewis-Beck et al. used data from face-to-face surveys. Moreover, while the American National Election Study asks about both candidates and parties, we asked only about candidates. Our approach therefore might be described as what Monroe (1992) would call a “conceptual replication”, whereby we faithfully replicate some aspects of the original study but allow for some minor differences in procedures and the manner in which variables are operationalized.6

Results

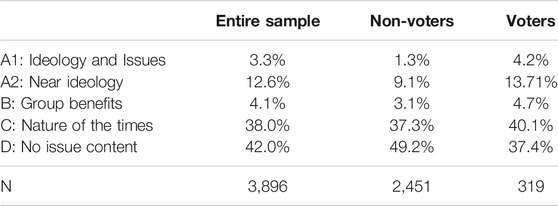

The first step in our replication is to describe the overall distribution of LoC in our sample, comparing the distributions of voters and non-voters. These results are shown in Table 1, where entries report column percentages.7

With respect to the overall distribution of LoC in the population, several noteworthy results emerge. First, we find a slightly smaller percentage of respondents in the ideological categories (15.9%) than in Lewis-Beck et al. (19.9%). If anything, it is perhaps a bit surprising that the drop is so modest, given the comparative lack of ideological cues in the local context. The second finding is that the “group benefits” category is considerably smaller here, at only 4.1%. Lewis-Beck’s analysis of ANES data found this to be the largest group, making up 28.2% of the population. Just as ideological cues are in short supply for municipal voters, so too may be cues about how various groups might fare under different leadership. Finally, we see that the “no issue content” category is the largest in the local setting. The relative size of this category seems a natural complement to the dearth of ideological and group-centered content, and likely reflects that municipal electors focus on candidates’ personalities and other non-political characteristics (Matthews et al, 2021).

As has been the case with existing work, we also find that turnout is positively associated with “higher” levels of conceptualization. Voters are more likely to be ideological thinkers (categories A1 and A2 are both larger compared to non-voters), and they are significantly less likely to fall into the “no issue content” category. A chi-square test reveals that the difference between these distributions is significant at p < 0.001.8 If the LoC is viewed as a measure of sophistication, then it would seem that voters are more sophisticated than their non-voting counterparts.

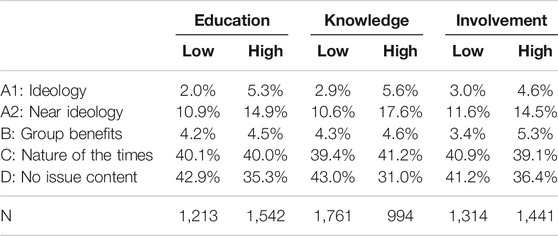

In the next stage of our replication, we consider the relationship between the LoC and education, knowledge and involvement (see Table 2). All explanatory variables are coded as dummies (0–1). The education variable compares those with a completed university degree to those without, while the median values are used as cutoffs for both knowledge and involvement. If our results replicate those of Lewis-Beck et al., we should find that higher levels of conceptualization are positively associated with all three factors.

The LoC are indeed positively correlated with all three measures in the table. Respondents with high levels of education, knowledge, and involvement are comparatively likely to view candidates in ideological terms, and unlikely to fall into the “no issue content” category. All differences are significant at p < 0.001.9 The effects observed for knowledge are perhaps somewhat stronger than for education and involvement, but we are hesitant to make too much of this difference without further study.

One final note is worthy of mention, given the nature of our data. There is some variation in turnout, education, knowledge and involvement by city. The patterns observed in Tables 1 and 2, however, continue to hold when fixed effects for city are added (refer to Supplementary Appendix S3 for details). We can state with great confidence, therefore, that the general findings of Lewis-Beck et al. have been replicated in a low-information, less partisan, local government setting in Canada.

Discussion

Replication studies are an important step in the scientific process for the sake of confirming findings, but also to see whether results from one context extend to another. In this brief research report, we have shown that the findings of Lewis-Beck et al. (2008) about the levels of conceptualization of voters, based upon American national elections, largely travel to the Canadian municipal context. Despite some modest differences in method (including survey mode and question content), we have demonstrated that the LoC framework can be adapted to this new, very different, environment. Further, our analysis validates, in a novel national and political context, key variables in political behaviour research—particularly, education, political knowledge and interest—as indicators of political sophistication.

More substantively, even in the absence of strong ideological cues (due to the less partisan and low-information nature of Canadian local elections), we see that a sizable portion of the electorate nonetheless views mayoral candidates in ideological terms. These findings confirm that, regardless of context, ideology is central to politics for a noteworthy segment of society.

Replication is just the first step in the application of this method to the study of local elections. Given that we know much less about how electors reason and act at this level of government than we do for federal and provincial elections, and due to the unique nature of local elections and politics, new methods of studying local electors are particularly valuable. The LoC framework is a powerful, yet largely overlooked, approach to studying how electors view politics and politicians, and can potentially be used to study a variety of questions that can add to our understanding of Canadian local elections, and indeed elections and voting more generally, in ways that standard quantitative methods of studying this field may not.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/HK9GJA.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ryerson University’s Ethics Review Board. The participants provided their informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2021.738569/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1Two cities in our sample do have parties, but even then, we expect party cues to play less of a role in both cities than they would in more established party settings. In Vancouver the mayoral election was won by an independent candidate, Kennedy Stewart. In Montreal, the incumbent mayor led an eponymous party, Equipe Denis Coderre, that was established to support his political agenda.

2Data were collected on our behalf by Forum Research Inc. Most respondents (roughly 75%) were recruited using random digit dialing and then sent invitations to complete the survey online while the rest are recruits from an existing panel. The first surveys were completed in roughly the month prior to election day, while the post-election surveys were fielded for about the same amount of time following the election. The return to sample rate in our sample is 70.9%.

3Portions of this and the next paragraph draw on (Matthews et al, 2021).

4In many cities, there were only two credible candidates, but in others, more than two candidates received noteworthy segments of the vote. In one city (Mississauga), only one mayoral candidate ever had a credible chance at victory. To ensure comparisons between cities are valid, however, we consider the top two candidates in all cities. The candidates considered in each city are: Kennedy Stewart and Ken Sim (Vancouver), Bill Smith and Naheed Nenshi (Calgary), Brian Bowman and Jenny Motkaluk (Winnipeg), Ed Holder and Paul Paolatto (London), Bonnie Crombie and Kevin Johnson (Mississauga), John Tory and Jennifer Keesmaat (Toronto), Valérie Plante and Denis Coderre (Montreal), and Régis Labeaume and Jean-Francois Gosselin (Quebec City).

5Assuming ordinal measurement, Krippendorff’s

6One other noteworthy difference between our approach and that of Lewis-Beck et al. is that ANES interviewees probe respondents several times for additional responses, whereas we provided respondents with only one chance to provide answers. This means that the textual material we are working with is comparatively limited. For further discussion of the significance of these methodological differences, see Matthews et al, (2021), pp. 13–14.

7The combined sample size for the analyses of voters and non-voters is smaller than the entire sample because turnout is measured in the post-election wave, which has a lower response rate than the pre-election wave.

8χ2 = 22.8

9χ2 values are 37.6 for education, 61.5 for knowledge and 20.3 for involvement.

References

Barabas, J., Jerit, J., Pollock, W., and Rainey, C. (2014). The Question(s) of Political Knowledge. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 108, 840–855.

Campbell, A., Converse, P., Miller, W. E., and Stokes, D. E. (1960). The American Voter. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Cassel, C. A. (1984). Issues in Measurement: The "Levels of Conceptualization" Index of Ideological Sophistication. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 28, 418–429. doi:10.2307/2110880

Field, J. O., and Anderson, R. E. (1969). Ideology in the Public's Conceptualization of the 1964 Election. Public Opin. Q. 33, 380–398. doi:10.1086/267721

Freeden, M., and Stears, M. (2013). The Oxford Handbook of Political Ideologies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lewis-Beck, M. S., Jacoby, W. G., Norpoth, H., and Weisberg, H. F. (2008). The American Voter Revisited. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press.

Lucas, J., and McGregor, R. M. (2021). “Introduction,” in Big City Elections in Canada. Editors Jack Lucas, and R. Michael McGregor (Toronto: University of Toronto Press).

Matthews, J. S., McGregor, R. M., and Stephenson, L. (2021). “Conceptualizing Municipal Elections: The Case of Toronto 2018.” Urban Affairs Review. (Pre-print version).

McGregor, R. M., Moore, A., and Stephenson, L. (2021). Electing A Mega-Mayor: Toronto 2014. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Sances, M. W. (2018). Ideology and Vote Choice in U.S. Mayoral Elections: Evidence from Facebook Surveys. Polit. Behav. 40, 737–762. doi:10.1007/s11109-017-9420-x

Scotto, T. J., Stephenson, L. B., and Kornberg, A. (2004). From a Two-Party-Plus to a One-Party-Plus? Ideology, Vote Choice, and Prospects for a Competitive Party System in Canada. Elect. Stud. 23, 463–483. doi:10.1016/s0261-3794(03)00054-4

Keywords: political behaviour, local elections, voter sophistication, Canada, qualitative research

Citation: Matthews JS, McGregor RM and Stephenson LB (2021) Levels of Conceptualization and Municipal Politics: Replication in a New Context. Front. Polit. Sci. 3:738569. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.738569

Received: 09 July 2021; Accepted: 06 September 2021;

Published: 22 September 2021.

Edited by:

Jorge M. Fernandes, University of Lisbon, PortugalReviewed by:

Diego Fossati, City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, SAR ChinaClara Volintiru, Bucharest Academy of Economic Studies, Romania

Copyright © 2021 Matthews, McGregor and Stephenson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: R. Michael McGregor, bW1jZ3JlZ29yQHJ5ZXJzb24uY2E=

J. Scott Matthews

J. Scott Matthews R. Michael McGregor

R. Michael McGregor Laura B. Stephenson

Laura B. Stephenson