95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci. , 22 November 2021

Sec. Comparative Governance

Volume 3 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2021.734093

This article is part of the Research Topic "Performing Control" of the Covid-19 Crisis View all 12 articles

This article studies how a technocratic populist can visually perform the authenticity and connection to ‘the low’ that is key to a populist performance while also maintaining the performance of expertise that is central to technocratic populist success. It relies on the case study of Czech prime minister Andrej Babiš and uses Facebook data from his profile in March and September–October 2020, the two peak moments of the crisis in the first and second waves of the COVID-19 pandemic. After offering a timeline of the Czech COVID-19 epidemic in 2020, it applies a dramaturgical analysis to four representative photos from Babiš’ Facebook page. It finds that Babiš was able to simultaneously articulate both expertise and authenticity, thereby both creating a connection to ‘the people’ while also articulating himself as an expert capable of handling the pandemic. He articulated expertise through a technocratic bodily performance, presenting himself as a cosmopolitan leader with international symbols of power like neutral-colored suits and elegant surroundings. At the same time, he also articulated himself as an authentic politician by showing his Facebook followers backstage imagery like a disorganized table and by showing himself as a busy man and an exceptionally hard worker. By illuminating the visual performance of technocratic populism, it offers insight into how technocratic populists constitute the expertise that their success rests on and that can also pose a threat to democratic societies, especially in a time of crisis.

Recent years have witnessed a rise in studies focusing on technocratic populism as a distinct variant of populism (e.g., de la Torre 2013; Buštíková and Guasti, 2019; Castaldo & Verzichelli 2020; Perottino & Guasti 2020; Snegovaya 2020). Guasti and Buštíková (2020, 468), define technocratic (sometimes referred to as managerial (Havlík 2019) or centrist (Havlík & Voda 2018)) populism as an “output-oriented populism that directly links voters to leaders via expertise,” wherein leaders present themselves as experts and present a “direct, personalized link” to their people, crossing over traditional left-right divides. Understanding populism as a “mode of articulation” (Laclau 2005) that creates an antagonistic frontier between “the people” and “the Other,” technocratic populists present themselves as representative of the ordinary people, pitted against the elite political establishment as the Other. It emerges as a response to perceived bad governance (Buštíková and Baboš, 2020); technocratic populists often position themselves as anti-corruption fighters, such as Igor Matovič in Slovakia, or leaders from business who can translate their experience into good governance, such as Andrej Babiš in the Czech Republic. Similarly, entrepreneurial populism (Heinisch & Saxonberg 2017) appears when success in business forms the basis of a leader’s claim to power. Entrepreneurial populist parties are socially moderate and centered around a highly trusted leader with a background in business, who claims that he will run the country like a business; Heinisch & Saxonberg (2017) note that this type describes Babiš particularly well.

In considering populism through Laclau’s lens as a mode of articulation, this study views populism as a performative act (Moffitt 2016; Palonen 2018) and a process of political meaning making (Laclau & Mouffe 1985). “The people” and “the Other” do not exist before they are articulated, and thus constituted, in opposition to one another. These meaning making processes take place not only through spoken or written language, but also through rhetorical, stylistic, or visual articulations or actions, which are constitutive because of their performative character (Palonen 2019). In other words, it views populism as form rather than content (Laclau 2005; Palonen 2021); both “the people” and “the Other” are empty of meaning until a political actor constitutes them. In a technocratic populist movement, then, ‘the people’ would generally be constituted expansively rather than exclusively in a national or ethnic sense, and “the Other” is more likely to appear as the political elite behind the perceived bad governance. The technocratic populist claims to represent the people in the “empty space of power” (Palonen 2021) by articulating himself as an expert who can more effectively work on their behalf.

The core logic of technocratic populism thus lacks the strong nativism and nationalism that characterizes the more frequently occurring right-wing populist movements, although technocratic populist movements can and sometimes do incorporate nativist and nationalist elements in their discursive frameworks; Babiš, for example, articulated immigrants as part of the constituent Other in his pre-2021 parliamentary election campaign messaging (Andrej Babiš, 2020e, September 23, 2021). Technocratic populism has anti-democratic potential in that it aims to quash debate in the name of prioritizing expertise (Buštíková and Guasti, 2019; Havlík 2019; Guasti 2020b). It delegitimizes political opponents and leads to apathy among potential voters (Buštíková and Guasti, 2019). Amidst the growing awareness of technocratic populism as a potential cause of democratic backsliding, the COVID-19 pandemic offered an unprecedented opportunity for it to shine. Even beyond previous findings that crises both provide an opening for and often are an inherent element of populist politics (Moffitt 2015; Moffitt 2016; Brubaker 2017; Stavrakakis et al., 2018), technocratic populism and its politicization of expertise hold a unique appeal in a crisis demanding expertise in public health (or at least the appearance of it) above all else (Guasti & Buštíková 2020). At the same time, people are open to losing civil liberties if a trusted expert made the decision to take them away (Arceneaux et al., 2020). This allowed technocratic populists in the Czech Republic and Slovakia to follow a similar playbook in their handling of the crisis. In addition to bypassing previously established and institutionalized methods of responding to the crisis and going about policy making in an erratic way, responsive to public demands—both features of general populist crisis responses—technocratic populists additionally politicized and thereby weaponized medical expertise to gain legitimacy (Buštíková and Baboš, 2020). In the Czech Republic, this playbook worked well during the first wave, but then fell apart in the second wave when Babiš’ responsiveness to public demands of openness pushed him to delay the government’s response to the increasing case numbers in the late summer and early fall.

Populist politicians, however, do not simply appeal to their potential electorate through policy proposals and decisions, technocratic or otherwise. They make affective connections with supporters through their physical performances; what they do with their bodies and the way that they behave is just as important as what they say (Casullo 2020a: 29). Elements like a populist politician’s clothes, hairstyle, posture, and hand gestures, in addition to their words and diction, all come together as part of a populist political style, which attempts to appeal “the people” against “the elite” and often relies on “bad manners” (Moffitt 2016: 44) or “flaunting of the ‘low’” (Ostiguy 2017), that is, abnormal political behavior, in order to do so. These physical and linguistic discursive articulations are performative, producing the effects that they name (Butler 1993). Social identities are formed, according to Butler, 1988 (529), through the “stylized repetition of acts through time,” acts which obtain meaning through their relative position in a discourse. The meaning granted to any individual performative action is also unfixed, but it is based on the meaning acquired by previous iterations of the same or similar actions (Peck, et al., 2009). To claim the mantle of control that technocratic populists claim their level of expertise must grant them, then, they must perform this quality of expertise through recognizable articulations that constitute it. When these articulations take place on social media, as is the focus of this study, it is worth remembering that they are usually the work of a professional PR team crafting the populist politician’s ultimate performance, a fact widely known and publicized in Babiš’ case (e.g., Ryšavá & Dolejší 2018); however, these curated social media performances still contribute to the overall bodily performances of populist leaders.

Casullo (2020a, 30) describes these articulations as the technocratic bodily performance, which “erases the marks of subjectivity and … is as impersonal as possible.” It relies on “proper” clothes from the professional world, such as neutral colors, business suits, and simple hair styles. It rejects anything ostentatious and limits the use of status symbols, thereby allowing the politician him or herself to appear transparent, a carrier of expertise rather than a flawed human. The elements here are cosmopolitan rather than connected to a certain national or ethnic identity; they are international symbols of expertise and leadership that cross the lines of business and politics.

It is important to study these bodily performances because the populist leader embodies the whole movement and thus also “the people” (Casullo 2020b), becoming an empty signifier that represents all the movement’s demands. However, the technocratic bodily performance might seem incompatible with the functions that a populist leader’s body performs. According to Casullo (2018, 2020b), the populist leader’s body has three functions: there is always something that connects him to the “lower” traits of the people; he always has something that differentiates him from his followers; and he always displays a symbol of power. Symbols of power are easy to find in a technocratic populist’s bodily performance, perhaps a business suit or the elite surroundings where the leader is photographed. The same goes for elements that differentiate the leader from his followers: while for Hugo Chavez this was an expensive watch that went along with his more common dress (Salojärvi 2020), the technocratic populist might employ any number of subtly placed designer items—a watch, glasses, electronic tools, etc.—that contribute to the performance of expertise.

The connection to the “lower” traits of the people—in other words, the “bad manners” that make up part of Moffitt (2016) conception of the populist political style—must look different for technocratic populists than they do for politicians whose main source of appeal was not expertise, however. Examples of this type of link to the people, such as Donald Trump’s “inappropriate” rhetoric or Timo Soini’s football scarfs (Salojärvi 2020), could harm the image of expertise. At first glance, technocratic populists maintaining expertise as a key part of their appeal appear more closely connected to Ostiguy (2017) conception of the “high,” rather than the transgressive “low.” This marks an important distinction between technocratic populists and many other populist leaders, but an expansive view of “the low” reveals angles that connect it to a technocratic performance. The “low” marks a politician as “one of ours” (Ostiguy 2017: 6) in the eyes of a voter; in a political-cultural sense, it appears as personalistic and strong leadership (Ostiguy 2017: 9–10) or even “ballsyness,” (Ostiguy 2017:10), the propensity to take action rather than merely talk about it. Articulations that fit into these categories within “the low” may still not appear to be transgressive or “bad manners,” which points to a limitation in the approach to populism as a political style. However, the “low” element of the populist leader’s body could also take the form of a performance of political authenticity, which entails four main dimensions of a politician’s performance: consistency, intimacy, ordinariness, and immediacy (Luebke 2020). Populist politicians often show their “authentic” natures in so-called backstage imagery (Salojärvi 2020), which often presents them as something other than an ideal, manicured politician. They often blur the lines between front stage and backstage, relying on backstage imagery (Timo Soini’s greasy hair, for example) even in official photographs. This produces an effect of transparency and authenticity, which helps to connect the populist leader to “the people.”

With the different technocratic populist embodiment of “the people,” however, the backstage imagery that constitutes political authenticity must take a different form, producing the effect of expertise rather than a connection to the people through the low. Just as the technocratic bodily performance relies on internationally recognizable symbols of power and expertise, the technocratic performance of authenticity might rely on recognizable visual elements signifying hard work, exhaustion, or access to high places—that is, the backstage and usually unseen elements that come together in the end to produce the front stage expertise and power that the technocratic populist uses to work for the people (see Table 1). Through this performance of authenticity, technocratic populists can both appear cosmopolitan and “high” while still connecting to the personalistic “low” as they show the backstage process that goes into creating the “high.” Rather than transgressing by breaking the rules, a technocratic populist does so by “authentically” revealing the underside—the hard work, the time spent, the messy office spaces—of what goes into following them.

This paper builds on Buštíková and Baboš (2020) study of the policy decisions that technocratic populists made during the COVID-19 crisis, turning instead to how they perform the expertise that technocratic populists claim to have. Relying on a broad conception of the populist leader’s bodily performance to include not only his costume and physical presence but also his props, staging, and backdrop, this paper will consider how a technocratic populist visually performs technocratic expertise and thereby embodies the people through visual backstage imagery in a crisis situation, using the case study of Czech prime minister Andrej Babiš. It finds that while Babiš maintained the technocratic bodily performance that is not typical to populist leaders, he also deployed non-bodily backstage imagery in order to forge a link with the people.

The first section of the results gives a timeline of the COVID-19 pandemic in the Czech Republic during the time of study, between March 2020 and October 2021. I began by observing the progression of the pandemic virtually, following Babiš and numerous other politicians and journalists on Facebook and Twitter and visiting Czech-based media sites in Czech and English on a weekly basis throughout the first 7 months of the pandemic (March–October 2020). The media organizations included Seznam zprávy, Český rozhlas, Respekt, Hospodařské noviny, Radio Prague International, Expats.cz, and Prague Morning, among others. Based on this observation, I determined the turning points around which I structured this study and gathered the Facebook data that I analyze below. The observation revealed three concrete phases of the early pandemic in the Czech Republic regarding the level of control that the government was trying to impose over the country: the initial onset and subsequent restrictions, the near-return to pre-pandemic life over the summer, and the second period of crisis in the fall after case numbers started to rise over the summer. This corresponds to three turning points: the beginning of the first wave, the loosening of control, and the beginning of the second wave. As the aim of this study is to explore the performance of a technocratic populist in crisis, I gathered data focused around the two turning points that launched the crisis periods, i.e. the moments when the government declared a state of emergency to mark the beginning of the first and second waves. While the second wave had already begun in epidemiological terms well before the government declared the state of emergency, the tone of the government messaging noticeably shifted at that point.

The data analyzed in this article consists of all of the photographic posts on Andrej Babiš Facebook page from two time periods: March 1–31 2020, and September 11–October 10, 2020. In addition to being the most used social media network in the Czech Republic (Macková et al., 2017), Facebook is also the platform that Babiš uses most comprehensively to communicate with his supporters. While he has nearly double the amount of followers on Twitter (445,100 on Twitter vs. 271,721 on Facebook, as of February 2021), his Twitter feed consists almost entirely of retweets and receives very little engagement. On Facebook, however, his posts regularly receive thousands of reactions and hundreds of comments, and he occasionally breaks news exclusively on his Facebook profile. While Babiš has a PR team dedicated to crafting his image on Facebook, the posts still go out under his name and in his voice on his public page, so this study considers him as the ‘owner’ of the posts; as such, the curated posts are also articulations that constitute Babiš’ performance as a technocratic leader, even if someone else chose and posted them. Facebook posts thus provide suitable data to analyze Babiš’ performances as a leader. Both of these periods encompass the time both immediately before and immediately after the onset of the crises brought on by the first and second waves, respectively. According to the timeline laid out below, this paper defines the onset of crisis in the first wave as March 12, when Babiš’ government first declared a state of emergency. It considers the onset of crisis for the second wave to be September 21, when then-Health minister Adam Vojtěch suddenly resigned. The two sets of data thus encompass a comparable amount of time both before and after the beginning of the crisis period.

In order to concentrate on Babiš’ own visual performance during crisis, the data set includes only posts that contain at least one new photo posted to Babiš’ timeline. That is, it includes posts with one photo or a photo album, but it does not include photographic posts shared from other Facebook profiles or pages, and it also does not include a large photo album posted to Babiš’ profile in early October that only included photos which had previously appeared on his timeline during the year prior to the actual post. It also excludes posts that contained exclusively text, videos, infographics, and other non-photographic visuals. In total, it consists of 134 posts, 62 from March and 72 from September and October.

In order to account for the character of the data set as a whole, this study first employed a loose content analysis (Rose 2001) using a coding scheme developed through the process of analyzing the March data and then applied to the September/October data. I developed the coding scheme by creating a category for each of several elements from each photo: the main explicit or implicit themes in the photo; the location where the photo was taken, if it was either visibly clear or clear through a location tag; whether Babiš was alone in the photo, and if not, who else was in the photo with him; and what key props (Goffman 1959; Salojärvi 2020), if any, were present in the photo. As new themes, locations, people, and props appeared, I created new categories for each and then did a second round of coding on the March data using the full coding scheme. I then used the same coding scheme for the September-October data, only adding categories that were unique to that data set (e.g., locations in Brussels or various EU and other foreign officials). To select the representative photos, I counted which of each element—themes, locations, people, and props—appeared most frequently in each of the data sets and then found the two photos from each set that featured all of, or the greatest number of, the most frequently appearing elements.

To these photos I then applied dramaturgical analysis (Goffman 1959; Salojärvi 2020) adjusted for analysis of visual material on social media (Hendriks et al., 2016). The dramaturgical approach views political activity on social media as a performance through which actors construct their desired political selves (Marichal 2013), thus accounting for the planned, curated nature of a politician’s social media feed. It views the social media data as essentially theatrical, asking the same questions about it as one would about a play in a theatre: who are the characters? What is the plot? What is the setting, and what props are used? How does the audience receive it? This approach blends particularly well with the performative approach to populism, because it analyzes the data through a performative lens, breaking down the material into its constituent elements and asking how they come together in the final performance, i.e., each of the Facebook posts analyzed. Each of these elements, after all, constitutes its own small part of the populist movement as a whole, and an in-depth dramaturgical analysis breaks down each post, or performance, to reveal the individual elements and explore how they come together. Thus, a qualitative analysis of a limited number of representative posts reveals valuable insights about the often-overlooked details that make up a technocratic populist performance that a broader empirical quantitative analysis would overlook.

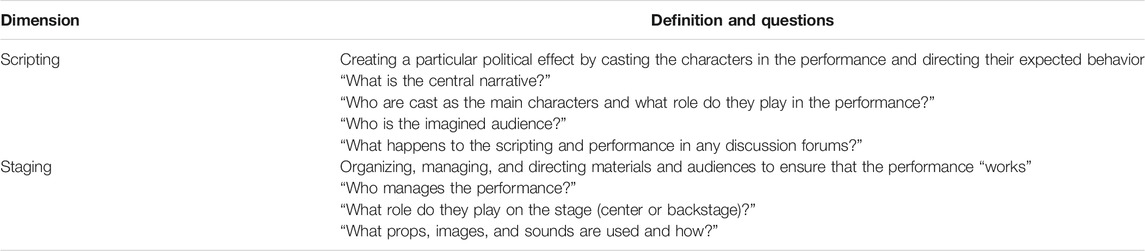

Hendriks, et al.'s analytical framework for dramaturgical analysis of social media material consists of two dimensions (scripting and staging), with a series of questions for each (see Table 2, below). This includes a question on audience reception, which I modified to fit this data set: “How do Facebook commenters respond to the scripting and staging of the post?” I used this as a starting point for my analysis of the Facebook comments. As this was only a small part of the dramaturgical analysis, I did not independently code the comments, but instead I looked at the first 20 “recommended comments” that Facebook offered for each post to gauge how and whether they reflected the scripting and staging of the post as explored through the other questions. I then added the question of whether the photo shows the front stage or the backstage of politics (Salojärvi 2020), as an additional method of gauging the authenticity that it can constitute. Based on the dramaturgical analysis of the representative photos from Babiš’ Facebook feed, I will then discuss how he performed both authenticity and expertise during the COVID-19 crisis. I analyze authenticity using Luebke's definition of political authenticity as consistency, intimacy, ordinariness, and immediacy combined with Salojärvi's conception of ‘backstage imagery’ as a conveyor of authenticity. I rely on Casullo (2020a: 30) description of the technocratic bodily performance as the framework through which I understand expertise.

TABLE 2. Questions for dramaturgical analysis (Hendriks, et al., 2016).

When the Czech Republic began imposing broad restrictive measures across the country in response to COVID-19, it was among the first wave of European countries to do so (Due to the spread of the coronavirus the government has declared a state of emergency and on March 12, 2020 further tightened preventive measures, 2020). By March 10, there was already evidence of community spread in numerous Czech regions, and on March 11, the day before WHO declared COVID-19 to be a true pandemic, the Czech government closed all schools except kindergartens. From that point forward, the Babiš and his government charged ahead with a series of restrictions that, at the time, largely went unchallenged. They imposed a state of emergency on March 12, claiming the additional powers that went along with it. The government approved a nationwide quarantine, which began on March 16, and the Czech Republic became one of the first European countries to close its borders the same day. On March 18th, they imposed the first face covering regulation in the EU, which set off loud criticism as the supply of masks and other PPE could come nowhere close to meeting the demand. Private citizens thus began making masks and giving them to each other in a notable show of nationwide solidarity.

This initial imposition of control relied on expert technocratic advice (Guasti 2020a), but concerns soon emerged about the transparency of the government’s response and the chaos and poor communication that characterized it. The unity granted by the opposition in the beginning of the pandemic collapsed when the government tried to push through legislation that would have benefitted Babiš by giving the government power to bypass parliament even after the end of the emergency powers declaration (Vláda má nápad, jak uhájit zákazy. Nový zákon dá pravomoc ministerstvu, 2020), which the opposition blocked by threatening to take away their support for the emergency powers declaration. The government then faced a further loss of control when the Prague Municipal Court ruled several measures to be illegal, including limits to the freedom of movement and travel abroad and the closures of large stores. Guasti (2020a) writes that this pushback from the opposition, guided by additional democratic safeguards like investigative journalism and healthy civil society, protected Czech democracy when the pandemic threatened it. By the time that the government’s temporary grip on power began to slip, the country had already succeeded in bending the curve of the pandemic.

During this period, the key nodal point to emerge were the facemasks. The Czech Republic was the first country in Europe to mandate broad mask usage (B. 2020), a move which received acclaim in the international press. While recommendations regarding facemask usage from WHO and numerous other countries were still ambivalent, the Czech Republic mandated that no one could leave home without a face covering, be it a surgical mask or a repurposed scarf (Willoughby 2020). A YouTube video sharing the Czech experience with masks in English went viral enough that then-Health minister Adam Vojtěch added a statement to it, recommending that his colleagues in other countries institute a similar mandate. Babiš also “claimed” the video, congratulating its creators and sharing it twice on his Facebook—once through a Washington Post link, in a post where he also wrote (in Czech) that he sent it to the European leaders and President Trump (Babiš, 2020e), and once with a direct link to the video with a caption in English, exceptionally, urging people to join the Czech Republic in wearing masks (Babiš, 2020d).

While the government celebrated its success in limiting the spread of the virus and largely attributed it to the masks, others noted that the government had mandated mask use at a moment when there was a severe shortage of medical supplies. In lieu of government support in acquiring masks and despite well-publicized attempts to get them from abroad, it was actually a grassroots effort that spread masks throughout the populace (Lokšová & Hoření, 2020) with hundreds of people banding together in a united effort to sew each other masks. During this time, Babiš celebrated the unity of the Czech people in a time of crisis on his social media pages while mostly ignoring the critics saying that his government had not done enough. From the mask mandate forward in the initial crisis period, Babiš wore a mask in all photos or videos posted to his Facebook. The masks were either surgical or fabric, with the fabric ones often displaying either a Czech flag or at least the colors of the flag. When he did respond to criticism about the mask mandate coinciding with an overall lack of PPE in the country, he excused the government’s action by claiming that the situation was the same in countries across the world and highlighting a particularly bad situation in Slovakia (Babiš, 2020b).

Through social media, Babiš presented himself as a prime minister for all, employing a civic conception of the Czech nation and using the flag as a rallying point both on Facebook and in Prague; every time he announced that a COVID patient had been cured, he represented this as a victory for the nation. While he still received criticism from opponents, for example about the unavailability of masks or his attempt to push through legislation that would benefit from him, there was little debate about whether the country had mounted a successful COVID response. Babiš celebrated the country’s victory, ignoring the discussion over whether the credit should have gone to himself and his government or the grassroots movements of people banding together.

Just as it had imposed restrictions earlier than many other countries, the Czech Republic also began to loosen these restrictions earlier. It had become clear that the country’s effort to track and trace cases of the virus were succeeding, despite the appearance of hotspots. The emergency powers declaration ended in May, and the government lifted many regulations even earlier than initially planned, once it began appearing as though the loosening of restrictions was not causing an uptick in viral spread. By late May and throughout June, the daily number of new cases was in the dozens. People flocked to expanded outdoor dining and drinking spaces, and later indoor spaces as well. A sense of success reigned; not only had the country stopped an epidemic in its tracks, but the opposition and civil society had also prevented executive overreach from Babiš (Guasti 2020a). The international press held the Czech Republic up as a positive example of having successfully handled the pandemic. Babiš stopped appearing exclusively in masks and moved on to publicly focusing on other public health issues, specifically the fight against cancer (Bartoníček et al., 2021). When the opposition demanded a concrete plan for a potential second wave of COVID-19, Babiš responded by saying that “We shouldn’t scare people about a second wave; we’re prepared for it” (Bartoníček et al., 2021).

Throughout the summer, various outbreaks of the virus kept cropping up, for example in the Karviná mine in Silesia in May and June (McEnchroe, 2020) and in a Prague nightclub in July (Nováková, 2020). The country’s collective embrace of the renewed openness remained through the beginning of September, then, as case numbers began to tick back up. On August 31, Babiš took part in a panel discussion with the other Višegrad Four leaders in Slovenia at Lake Bled, where he referred to the group’s success in confronting the virus as a past event that they had already completed, referring to the V4’s “results” rather than recognizing it has an ongoing struggle (STA - Slovenska tiskovna agencija, 2020).

Case numbers started rising rapidly in the first third of September, when daily infections rose first over 1,000 and then over 3,000 for the first time on Sept 18 (Czech Republic Exceeds 3,000 Daily COVID-19 Cases for First Time, 2020). The government reimposed mask mandates in most indoor public spaces, but the mandates included many exceptions and changed frequently, and there were no attempts to limit people’s activities. Amidst rising discontent in the public and the media, Health Minister and ANO member of parliament Adam Vojtěch suddenly resigned on September 21 (‚Chci dát prostor pro řešení epidemie. ‘Ministr Vojtěch rezignoval na funkci ministra zdravotnictví, 2020), saying that he was proud of his and his team’s work during the first wave; in a separate statement on Facebook, Babiš also congratulated him for managing the first wave “unbelievably” (Babiš, 2020f) while neglecting to mention anything about the second wave. Given the concentration of power in ANO around Babiš alone, many media reactions to this claimed that Vojtěch was, in effect, taking the fall for Babiš’ inaction in confronting the second wave. Roman Prymula, an epidemiologist who had become a highly trusted apolitical public figure during the first wave, became the new Health Minister.

The country re-entered a state of emergency on Oct 5 (Today Starts the State of Emergency. What You Need to Know, 2020), but government restrictions remained inconsistent and confusing, which resulted in much criticism. When cases continued to rise, the government began increasing restrictions, culminating on Oct 21, when they reimposed the strictest lockdown since the spring, and Babiš gave a press conference apologizing for his government’s handling of the pandemic since May (Smith-Spark & Kottasová, 2020). On October 22, however, a major Czech tabloid captured photos of Prymula, among others, without a mask on, coming out of a Prague restaurant when restaurants were supposed to be closed (Právě on vyhlašuje nejpřísnější opatření: Pod rouškou tmy si Prymula bez roušky vyrazil do restaurace, 2020). Prymula resisted even Babiš’ calls for him to resign (Prymula byl v restauraci s Faltýnkem a bez roušky, 2020), claiming that he had not done anything wrong and that the media had overblown the situation (EuroZprávy.cz, 2020). On October 27, however, Babiš named pediatrician Jan Blatný as the new Health Minister, and he officially took over on Oct. 29.

After that, the government remained a constant object of criticism and mistrust, and the Ministry of Health fell to ridicule, as Blatný’s eventual replacement, Petr Arenberger, lasted less than 2 months before resigning, only to be replaced by Adam Vojtěch in May 2021. The epidemic remained out of control for months after Prymula’s resignation. From the beginning of November 2020 until the spring of 2021, the country went into and out of strict lockdown measures, and Babiš and his government received criticism for confusing guidelines and for not being willing to fully shut down activity. The series of lockdowns, fluctuating between looser and stricter, did not soon result in an improved epidemic situation overall. In early 2021, the Czech Republic was among the worst in Europe in terms of cases per 100,000 inhabitants (as of Jan 13, 1119/100,000) and deaths per 100,000 inhabitants (as of Jan 13, 15.58/100,000).

While the health system has so far been able to maintain the capacity to treat all COVID patients, there were concerns about the number of front-line health care professionals catching COVID. A further problem is the rise of disinformation, resistance to mask wearing, and conspiracy theories regarding the vaccine. The government received media criticism for failing to adequately communicate with the public early about the vaccine, which may have been one cause of the vaccine hesitancy now circulating online (Kabrhelová 2021). Overall, Babiš has ended up in a very unpopular position due to his government’s handling of the pandemic and to the perception—which he promotes—that he is ultimately in control. While he and his government received praise after handling the first wave, and his ANO party received its highest level of support in 6 years, 2020 ended with support for Babis and ANO slipping in favor of the opposition parties (Vachtl 2020), with the parliamentary elections coming up in October 2021.

The rest of the data and analysis will focus on the key inflection points gathered from this timeline: the initial imposition of control in March at the beginning of the first wave and then the attempted reimposition of control in September/October at the beginning of the second wave. These were the moments during which the situation was most in flux and therefore direction and expertise from the prime minister would have been the most in-demand. They were also the points at which the pandemic was the main, if not the only, focus of the news, and therefore also of Babiš’ Facebook feed.

Table 3 shows the key results of the content analysis, which I will divide into the March and the September/October data sets.

In the March data, five themes turned up significantly more than any others. Eight posts (12.9%) offered a calming message, for example a photo taken at a warehouse full of food on March 13, when the trend of panic buying was spreading across the globe. Nine posts (14.5%) included a press conference. Nine posts (14.5%) emphasized Babiš’ long working hours, either through explicit mention or through the time when they were posted. 10 posts (16.1%) centered non-pandemic related themes, but the last of these was posted on March 11—1 day prior to the crisis onset. The most prominent theme among those categorized was foreign partnership, with 11 posts (17.7%) featuring this theme. Within this category, four foreign partners came up: the European Union (four posts, 6.4%), China (three posts, 4.8%), Russia (two posts, 3.2%), and the Višegrad 4 (two posts, 3.2%).

The location category was less varied. 23 posts—over a third, or 37.1%, of the whole March set—were taken at Strakovka, the Office of Government, where Babiš’ main office is located. These included, for example, photos taken in Babiš’ office and photos taken at the main press conference area. The only other prominent location category was airports, with eight posts (12.9%); these posts documented the cases in which the Czech Republic received medical material from abroad (namely from Russia and China). Finally, there were four photos (6.4%) each at a warehouse, at Prague Castle, and overlooking Prague.

In the category of people in the photos, 19 photos (30.1%) featured Babiš alone. In the photos either of Babiš with other people or other people without Babiš, the group of people most frequently present were non-recognizable figures who appeared to be aides or people who Babiš was meeting with; 15 photos (24.1%) included this category of people. Another seven photos (11.2%) included blue-collar workers, for example airport or warehouse workers. The only public figure who showed up frequently was Karel Havlíček, the Minister of the Economy, who appeared in seven photos (11.2%). President Miloš Zeman and Health Minister Adam Vojtěch appeared in four photos (6.4%) each.

The props coding category was varied, including both Babiš’ clothing and the items that surrounded him in the photos. By far the most frequently occurring prop was a particular outfit: a full suit, including a tie, which showed up in 28 photos (45.1%). The second most common prop was a surgical mask, which appeared in 13 photos (21.0%), although in total some type of mask (whether a surgical mask, cloth mask, or respirator) appeared in 22 photos (35.4%). There were three other prominent props: Babiš desk, always strewn with papers, appeared in nine photos (14.5%); he was wearing a suit with no tie in eight photos (12.9%); and a video conferencing screen appeared in eight photos (12.9%). Based on this analysis, a representative post from the March data set would be taken at Strakovka (the Czech Office of Government) with Babiš alone, wearing a suit and possibly also a mask, and the post would thematize either a foreign partnership, emphasis on Babiš’ long working hours, or a press conference.

The data from Babiš’ Facebook in September and October showed much less variation. Thematically, the posts were much less defined than the March data. Many posts simply involved Babiš in his office during normal working hours, which often did not specify what he was working on or even emphasize long working hours, a pronounced theme in the March data. The most pronounced themes in this data set were explicitly non-virus business (10 posts, 13.9%), foreign partnerships (9 posts, 12.5%), and the EU (7 posts, 9.7%). This, however, left the majority of posts uncategorized according to the framework developed during the initial analysis of the March data.

Similar locations to those in March showed up in the September and October data, however. There were 14 posts (19.4%)) at an airport, although in this dataset they portrayed Babiš himself in transit rather than him meeting shipments of medical material on the tarmac. A further 18 posts (25.0%) came from when he was in Brussels for EU meetings. However, by far the most frequently occurring location was Strakovka, with 24 posts (33.3%), including 18 posts (25.0%) within that category of photos specifically from Babiš’ office.

There was also very little variation in terms of who turned up in the photos. Babiš was pictured alone in 28 posts (38.9%), by far the most prevalent category. There were 14 posts (19.4%) featuring unnamed or unrecognizable officials or coworkers, most of them appearing alongside Babiš. There were another six posts (8.3%) featuring military officials. The only recognizable public figure who appeared in more than one post was Roman Prymula, who was named the health minister on Sept. 21, but he was only pictured four times (5.5%) in this dataset.

The props category, however, presented a larger collection of prominent objects than any of the previous categories in this dataset. The object that turned up the most was Babiš’ fancy suit, which appeared in 43 posts (59.7% of the total posts). The second most frequently occurring item was a respirator, which was present in 37 photos (51.3% of the total posts). Babiš’ desk strewn with papers and his glasses both appeared in 20 posts (27.8% of the posts), and immediately following those was the video conferencing screen, in 19 photos (26.4% of all posts). From this analysis, a representative post from the Sept-Oct data would be uncategorized by theme and would feature Babiš alone in Strakovka, wearing a fancy suit. There would also be a respirator in the photo and it could contain some combination of the following props: the desk covered in papers, Babiš’ glasses, and the video-conferencing screen. Based on the qualitative content analysis of the full dataset, the next section will now report the results of the dramaturgical analysis of four representative photos, two from each period. The overall results of the dramaturgical analysis can be found in the following Table 4.

This post (Figure 1) is representative of the March dataset in that the location is Stromovka (evident both from the location tag and the photo in the background to Babiš’ left), Babiš is pictured alone, he is wearing a full suit and a surgical mask, and it was taken during a press conference. Given that the date is March 17, less than 1 week after he declared the state of emergency, there is no need to specify the theme of the press conference. Beginning with Hendricks et al.'s rubric, we turn first to the scripting of the post. The main and only visible character in the post is Babiš himself, and the central narrative is that Babiš is informing the public about the government’s discussion on the COVID-19 crisis. Due to the photo angle, it is conceivable that Babiš is the only government official taking part in this press conference, which gives him a leading role in both combatting the crisis (because he was at the meeting) and informing the public about the crisis (because he is the one speaking about it). The imagined audience is twofold: because it was posted to Facebook, the audience is Babiš’ followers on Facebook; however, the media professionals present at or otherwise watching the press conference are the implied audience to the scene portrayed in the photo. Turning to the staging of the post, the manager can be seen as either the photographer, whose perspective is the same as the audience at the press conference, or as Babiš, who takes ownership of the post as a whole by putting it up through is Facebook account; this result is the same for each of the representative photos. Babiš in effect controls the choice of photo and the choice of what information goes into the caption, because both go out in his name, regardless of whether he has a social media team actually making those decisions. In this sense, Babiš is both the central character of the post and its manager. Many of the props in this post all point to a position of leadership: the full suit and tie, the uniform of power both in government and in the private sector; the press conference podium, which confirms that the person in the photo is trusted enough to speak to the public; and the flags behind Babiš, which sediment him in a position of government power rather than simply managerial power. The position of the flags mean that Babiš is visually backed by both the Czech Republic and the EU.

FIGURE 1. Representative photo #1. Caption: “Presser after a meeting of the government.” (Babiš, 2020a, March 17, 2020).

The one additional notable prop is the surgical mask, which communicates the crisis and which was, in effect, the main symbol of the Czech first wave. At the point when Babiš put up this post, masks were required anywhere outside of the home for the country’s entire population, but at the same time, there was also a shortage of PPE that was affecting both health care workers and the rest of the population alike; this resulted in the grassroots movement of people sewing masks for each other. Delving into the comments on the post, it immediately becomes evident that this issue of mask availability took much of the focus away from the central narrative of Babiš in control. While some of his apparent supporters left positive comments thanking him, for example, for his work as prime minister and for leading by example, the majority of the “most relevant” comments that Facebook displays are from people criticizing Babiš for giving himself access to surgical mask after having made the mistake of not being able to provide them for the rest of the country. Both sides of this, however, do grant Babiš control over the situation. From his supporters, Babiš receives full credit for leading the country in crisis; from his detractors, he receives full blame for not ensuring an adequate supply of masks. Moving outwards to the question of front stage vs. backstage, this photo represents the front stage of politics. There is nothing intimate or revealing about a photo from a press conference; in fact, this photo could have appeared just as easily in the mainstream media, representatives of which were surely present when it was taken. Rather than constituting authenticity, photos such as this one contribute to the constitution of Babiš, previously the CEO in charge of a company, as Babiš, now the government official in charge of a country.

The next representative photo (Figure 2) comes from Babiš’ office on March 26, 2020. Beginning with the scripting, the central narrative is about Babiš engaging in the regional Višegrad 4 (V4) partnership. The photo leaves out two of the V4 partners—Hungary and Poland—and thus leaves Babiš, the main character, alone with Igor Matovič, the then-prime minister of Slovakia, as the supporting character. Slovakia, having once belonged to the same country as the Czech Republic, is still regarded as a “brother nation” of sorts, far more so than Hungary or Poland. The imagined audience is solely on Facebook; the empty table and empty space surrounding Babiš implies that no one is in the meeting besides him and the other country leaders. While the audience does not learn anything about the content of the meeting, the framing of the photo suggests that the audience on Facebook is getting a behind the scenes look. In terms of staging, the photographer is backstage—literally behind Babiš—even Babiš himself is not centered in the photo. Instead, he is across from Matovič, and while Matovič is farther away from the audience’s perspective, the angle of the shot puts his face in the picture instead of Babiš’. The audience reaction in the comment section, then, is quite mixed on this photo, with very few of the top comments referring to the meeting. While some commentors congratulate Babiš on an unspecified job well done, others criticize him on various fronts: for wearing a mask while alone in a room, for ignoring “Greece and the new wave of migration,” for not having a plan to address the crisis.

FIGURE 2. Representative photo #2. Caption: “V4 meeting” (Babiš, 2020b, March 26, 2020).

Two props show up in both photos: the full suit and the surgical mask. Babiš’ surroundings are a key difference, however. The trappings of government still appear in the photo: the Slovak and EU flags in the video, and the Czech coat of arms and portrait of Czech president Miloš Zeman on the wall. The photo does not come from a public space, though, but rather from Babiš’ office in Strakovka, which would not necessarily be recognizable to viewers if the post did not include a location tag (although regular followers of his account would most likely find it familiar, because it shows up in so many of his posts). Looking around the office, though, it contains symbols of power that would be applicable in both the government and corporate realm, like Babiš’ suit, the polished wood table with matching chairs, the chandelier, and the video conferencing screen. The less formal elements of the scene, then, are the papers in front of Babiš on the table and his hunched posture. These less formal elements in particular place this photo in the backstage category. Babiš gives an “authentic” look backstage through the framing of the photo, which does not appear to be posed, and which visually centers the work in front of Babiš (the papers and the conversation with Matovič) rather than himself. It shows Babiš ignoring the publicity while visibly focusing on the work—even his line of sight appears to be directed at his papers.

The first photo (Figure 3) from the September-October dataset takes us back to the same location: Andrej Babiš’ office in Strakovka. Babiš is once again the central character, as the photo offers a clear view of neither the names nor faces of the people on the video conferencing screen. The imagined audience is once again Babiš’ Facebook followers, although in this case the possibility remains that he is not alone in the office. There are at least two potential central narratives here. For those who know that the Change for the Better group aims to work towards “a restart of the Czech economy,” then the narrative lies in Babiš working with an external group to better the Czech Republic economically speaking. Those who do not recognize the group, though, will still grasp a generally positive narrative of Babiš working with an external group to help the country somehow. As was the case with the previous photos, the scripting and the narrative do not form the basis of the discussion in the comment section, which instead consists of a mix of his supporters defending him and pledging their support and his detractors offering unrelated criticism. In this case, though, several of the top comments included plays on the name of the external group, like “A change for the better will happen when you resign. Don’t draw it out!.”

FIGURE 3. Representative photo #3. Caption: “Videocall with the Change for the Better group” (Babiš, 2020c October 14a 2020).

In this photo, the government-related props are almost entirely absent, leaving instead the image of a busy and important person. Props like the papers on the table, the video conference (which takes up a significant portion of the space available in the photo), the tablet computer on the table, and the tea pot and water jugs together all create the impression that the meeting is a long and important one, requiring preparation work (the papers) and not allowing time for breaks (the drinks). The crisis is also present in the photo, though, through the respirator that Babiš is wearing and what appears to be hand sanitizer or another sanitizing spray on the table. This is another backstage photo, giving followers a glimpse into a private meeting between Babiš and the Change for the Better group. Through a photo like this, followers can see his modus operandi at work in, for example, the fact that he prepares for a virtual meeting with physical papers and still uses a tablet. Even this backstage shot, however, still displays a sense of grandeur through the chandelier overhead.

This photo (Figure 4) contains many clear visual similarities with the previous one, which was taken on the same day. Instead of external cooperation, this narrative is of intragovernmental cooperation between the national and regional levels. While the central narrative of the previous photo left the crisis out, viewers would most likely understand it to be implied here; Babiš posted this photo the day after announcing a new, restrictive set of regulations, at a time when cases were rapidly rising. Babiš is once again the main character, with the blurred pictures of the governors in the background as the supporting characters. He plays a leading role, both visually and through his position, which is literally above the governor level. As this is another backstage photo, Babiš’ followers on Facebook are the audience again. Babiš and the photographer manage the photo again, and again Babiš is in a central position, although he is giving attention to the meeting at hand rather than the photo. In the comment section, where the usual mix of his supporters and detractors turn up, various threads of the central narrative do appear repeatedly. Some congratulate him on his handling of the pandemic, others criticize it; some point out ANO was not able to win many of the regional governorships; still others make specious claims about the pandemic and how the new restrictions are unnecessary, because, for example, “it’s just another flu.”

FIGURE 4. Representative photo #4. Caption: “Videocall with the regional governors right now” (Babiš, 2020d, October 14b 2020).

Because this is also a post involving the regional governors, then, Babiš can be seen as the manager on multiple levels, as it is expected that he would be running the meeting in addition to running his Facebook page. The props are very similar to the previous photo, constituting Babiš as a busy man hard at work; this photo additionally shows a pen and a pair of glasses, both tools indicating focus. The crisis is also present again in the props, with the respirator and sanitizer. The visual governmental props are also absent from this photo, but the caption makes it clear that the post focuses on government business. Finally, this photo is also similar to the previous one in that it gives a backstage view of running the state like a firm. Again, followers can see an “authentic” look at how Babiš works with some of his most important governing partners, a glimpse into a meeting that may have been reported on later but which was evidently not open to the public, if it took place in Babiš’ office. While the photo still displays symbols of wealth and power, like the designer glasses and the video conference screen, there are also displays of Babiš’ personal imperfections—again, the glasses.

Each of the representative photos includes several of the visual elements of the technocratic bodily performance. Babiš is wearing a suit in every photo, and all of them are the same neutral, dark grey color. There is no obvious change in his hair, which is just a simple, short cut. In addition to wearing the business suit as a uniform of power and expertise, the pictures also show Babiš in settings that communicate a similar message: the press conference and his elegantly appointed office. The designer glasses are a present, yet subtle, status symbol connected to Babiš’ bodily performance; they are also a display of a personal imperfection. Babiš’ technocratic performance in this set of representative photos, then, is nearly exactly as expected.

We now turn to how, as a technocratic populist, Babiš visually performs authenticity as an embodiment of the people within this technocratic bodily performance. Three of the four representative photos did fit the hypothesis that this authenticity would be based on backstage visuals showing Babiš as a hard worker. The first photo, which shows Babiš at a press conference, is strictly a front stage image; nothing about it fits the criteria of authenticity, besides the fact that it helps to build up the quality of consistency when viewed along with the rest of the visual posts that show how Babiš spent the entire working day. The other three photos, however, show Babiš in backstage settings in terms of both the content of the image and the staging. All three of them show him in exactly the same place: in his office, at a big table covered with papers, having a virtual meeting on the big screen. They also all show him at non-frontal angles, with the photographer positioned either behind or to the side of him, and in none of these cases is he actually looking at the camera. This creates the impression that the audience is getting special access to the backstage side of expertise, or the work that goes on behind the scenes in order for the expertise to come about. This, we are led to believe, is what it looks like and what actually goes into running the state as a firm.

The three backstage photos also come together to constitute Babiš as a rather disorganized person, who works from papers strewn across a table even during a video call. His desk is always shown as a busy, full space, creating the impression of ongoing work that requires a great deal of information and access for it to happen. Rather than maintaining a bodily ‘backstage’ performance of an unkempt or ethnically particular populist leader, Babiš’ disorganization bleeds into his working style, which he makes visible through these photos. While there were photos in the dataset that showed him wearing less formal attire, for example a shirt without a jacket or a sweater, the full suit appeared in far more of the photos. By combining the technocratic bodily performance with the images of disorganized work, Babiš was able to both create a veneer of transparency and authenticity linking him to the people while also not dropping the technocratic performance nor the appearance of expertise.

This performance of the hard worker did not, however, include posts showing Babiš working exceptionally long hours. This would be very easy to achieve on Facebook, simply by posting photos of Babiš working late in the evening or on weekends. While there were posts in the dataset that did thematize long working hours, though, none of these representative photos did so. On the contrary, they were all posted on weekdays during normal daytime hours, and they all show Babiš working with other people during the working day rather than on his own at times when other people would not be expected to be working.

The representative photos did show Babiš surrounded by a series of status symbols, however. They reveal that Babiš has access to technology that many people working from home would never be able to own—the combination of the big screen and the tablet, not to mention the formal office surroundings, such as the furniture and the chandelier. While there is nothing physically on Babiš’ body that differentiates him from his followers as Chavez’s Rolex did for him (Salojärvi 2020), the location and surroundings of Babiš’ body in these representative images serve the same function without interfering with the performance of technocracy. He occupies an elite space while still keeping a distance between his physical body and that space. The technology used in a work environment also contributes to the performance of the hard-working technocrat, particularly in the context of the COVID crisis. By holding these meetings virtually and posting photos of them, Babiš was in effect posting reminders both of the ongoing crisis and the fact that he was working to address it; the same can be said for the masks, respirators, and hand sanitizer that appear in the photos as well. While the specific content of the press conference and each of these meetings remains unsaid, the presence of the pandemic-safe elements like the virtual meeting and the face coverings leave open the possibility—and indeed suggestion—that the pandemic is in fact the topic of discussion.

In this paper, I analyzed Andrej Babiš’ visual performance of technocratic populist expertise during the COVID-19 crisis in order to explore how a technocratic bodily performance could be combined with backstage imagery (Salojärvi 2020) in order to maintain a link to “the people” in a uniquely technocratic populist way. It found that Babiš did align himself with Casullo (2020a) conception of a technocratic bodily performance in terms of the cosmopolitan symbols of power and expertise, business suits, neutral colors, simple hairstyle, and lack of status symbols actually connected to his body, but that these elements leave out the potential visual articulations appearing in his surroundings. Understanding a performance of expertise to include not only the actor’s body, but also their actions, requires a broader look at what appears around them, and this study found that the backstage elements of Babiš’ performance did appear around him rather than connected to him. Whereas departing from Casullo’s technocratic bodily performance could have inhibited the performance of expertise that made technocratic populists so appealing early in the COVID-19 crisis (Guasti & Buštíková 2020), including backstage imagery as Babiš’ surroundings positioned him as both a technocratic expert and an exceptionally hard worker (see Table 5).

This study found that the main backstage imagery appearing in Babiš’ visual performance included behind-the-scenes locations, disorganized working spaces, and non-bodily status symbols. The behind-the-scenes backdrop of his office contributed to the performance of transparency and authenticity that is so important for populist leaders (Salojärvi 2020); the photos visually removed the barriers between Babiš’ private working space and the public, offering the perception of access and availability. This can be seen as analogous to other populist leaders such as Chavez bringing their bodies—and thus their populist movements, which they embody—into large groups of “the people,” (Casullo 2018) but in the reverse. Rather than going out to meet his supporters, Babiš brings “the people” into the seat of power along with him by so frequently publishing pictures of himself there. The disorganized nature of Babiš work, then, serves a similar function as Timo Soini’s greasy hair or football scarves, as an example of “bad manners” (Moffitt 2016) linking him to “the low.” Instead of impinging on his impeccable performance of technocratic expertise, however, a disorganized workspace full of papers and drinks is a recognizable signifier of hard and prolonged work. It assures followers that Babiš’ is exercising his expertise and treating the situation with an adequate level of urgency, while at the same time we can regard his technocratic bodily performance as assurance that he has the situation under control. Without the signifiers of active work, the performance of expertise alone might not actually contribute to the perception that Babiš was engaged in solving the problem. At the same time, the disorganization also lends Babiš some relatability and ordinariness, one of the elements that contributes to political authenticity (Luebke, 2020).

Babiš’ photos also included articulations of the ever-present crisis, another key element of the populist style (Moffitt 2016), in the form of the masks, respirators, hand sanitizer, and to some extent even video conference screen. This remained the case even when it was not strictly necessary, as several Facebook commentators noted regarding his use of a respirator while he was alone in his office. However, in three of the four photos, the crisis was only present, rather than centered; the photos articulated crisis amidst expertise, rather than vice versa. Once again, this contributed to the melding of a technocratic performance with a populist performance. This particular crisis, however, provided the additional opportunity for crisis to become an element of Babiš’ bodily performance, as the most visible signifiers of the crisis were the masks and respirators that Babiš was wearing. In this way he was able to perform the crisis, while at the same time performing, and placing himself in the middle of, its remedy. This could also have contributed to the technocratic populist appeal during the pandemic (Guasti & Buštíková 2020), and this finding also opens the door for further research to explore how technocratic populists articulate crisis in the absence of a genuine public health crisis.

Notably, the technocratic populist actions during a crisis that Buštíková and Baboš (2020) found of bypassing established an institutionalized methods of crisis response, erratic policy making, and politicizing and weaponizing medical expertise were not at all evident from Babiš’ visual performance. This highlights the importance of research that views politics through a performative lens, as it offers another explanation of how a technocratic populist might be able to step into the empty space of power in order to take those actions. His visual performance does, however, exemplify another result of technocratic populism: the sidelining of the opposition and thus the degradation of democracy at the hands of technocratic expertise (Havlík 2019; Guasti 2020a; Guasti & Buštíková 2020). Babiš was physically alone in all of the photos, and the other participants in the virtual meetings came from either outside of government or outside of the Czech Republic. The photos thus articulated him as the sole individual responsible for the Czech COVID-19 response and the only person capable of crafting it. Strategically, this may not have been the best choice, as Babiš’ poll numbers never fully recovered to their highs from before pandemic, and the center-right SPOLU coalition ended up narrowly beating ANO in the fall 2021 parliamentary elections. There are manifold reasons for this defeat at the polls, likely including Babiš’ appearance in the Pandora papers, which were published a week before the election, and the resulting fallout, which has included multiple investigations into his finances and transactions (Alecci 2021). While time and further research will be necessary to explore this potential connection, performing full responsibility for a crisis response so widely perceived (and experienced) as a failure could have contributed to ending Babiš’ tenure as prime minister.

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

IH is the sole author of this article.

During the writing process the author was funded was funded by a Kone Foundation project, Now-Time, Us Space: Hegemonic Mobilisations in Central and Eastern Europe (nr: 201904639).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

I would like to thank Virpi Salojärvi for her guidance and patience while I wrote this article; Emilia Palonen for her continued mentorship and support; and the HEPPsinki Research Hub for their astute comments and camaraderie.

Alecci, S. 2021. Czech Prime Minister’s Party Narrowly Loses Re-election Days after Pandora Papers Revelations in surprise Outcome—ICIJ. ICIJ. Available at: https://www.icij.org/investigations/pandora-papers/czech-prime-ministers-party-narrowly-loses-re-election-days-after-pandora-papers-revelations-in-surprise-outcome/(Accessed 2021, October 9)

Andrej, Babiš. 2021. Chaty a Chalupy Migrantům? Nikdy! [Text post]. Facebook. Available at: https://m.facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=2352758151527482&id=214827221987263&m_entstream_source=permalink. (Accessed 2021, September 23)

Andrej, Babiš. 2020e. Gratuluju Autorům Toho Skvělého Videa, Co Jsme Všichni Viděli a Co Jsem Poslal Většině Premiérů a Prezidentů Evropy a Prezidentu [Shared Link]. Facebook. Available at: https://www.facebook.com/AndrejBabis/posts/1835399013263401. (Accessed 2020, March 29)

Andrej, Babiš. 2020c Jednání V4 [Shared Photo]. Facebook. Available at: https://www.facebook.com/AndrejBabis/posts/1832688423534460.(Accessed 2020, March 26).

Andrej, Babiš. 2020f. Moc Děkuju Adam Vojtěch Za Práci, Kterou Na Zdravotnictví Vykonal. Je to Slušný, Poctivý a Velmi Pracovitý Člověk. Jsem Přesvědčen [Text post]. Facebook. Available at: https://www.facebook.com/AndrejBabis/posts/2016430318493602. (Accessed 2020 September 21)

Andrej, Babiš. 2020a. Tiskovka Po Jednání Vlády [Shared Photo]. Facebook. Available at: https://www.facebook.com/AndrejBabis/posts/1822742997862336. (Accessed 2020, March 17)

Andrej, Babiš. 2020h. Videocall S Hejtmany Právě Teď. [Shared Photo]. Facebook. Available at: https://www.facebook.com/AndrejBabis/posts/2041254036011230. (Accessed 2020 October 14b)

Andrej, Babiš. 2020g Videocall Se Sdružením Změna K Lepšímu. [Shared Photo]. Facebook. Available at: https://www.facebook.com/AndrejBabis/posts/2041475335989100. (Accessed 2020 October 14a).

Andrej, Babiš. 2020b Vláda Je Prý Neschopná, Čtu Tady Na Facebooku. Nezajistila Roušky. Tak Se Koukněme, Jak Je to Jinde. Naprosto Totožná Situace [Shared Link]. Facebook. Available at: https://www.facebook.com/AndrejBabis/posts/1824178701052099.Accessed 2020, March 19).

Andrej, Babiš. 2020d. Watch This Video. Czechs Are Sewing Their Own Masks to Fight COVID-19. Everyone in the World Should Follow Our Example [Shared Link]. Facebook. Available at: https://www.facebook.com/AndrejBabis/posts/1834387463364556. (Accessed 2020, March 28)

Arceneaux, K., Bakker, B. N., Hobolt, S., and De Vries, C. E. (2020, October 5). Is COVID-19 a Threat to Liberal Democracy. doi:10.31234/osf.io/8e4pa

Bartoníček, R., Valášek, L., Chripák, D., Švec, P., and Klézl, T. 2021. Anatomie Selhání: Váhání a Zmatek. Proč Je Česko Po Roce Pandemie V Nejtěžší Krizi. Aktuálně.Cz. Available at: https://zpravy.aktualne.cz/domaci/casova-osa-covid/r∼fd4c3f7e0ec511eb9d470cc47ab5f122 (Accessed 2021 March 1).

Buštíková, L., and Baboš, P. (2020). Best in Covid: Populists in the Time of Pandemic. PaG 8 (4), 496–508. Scopus. doi:10.17645/PAG.V8I4.3424

Buštíková, L., and Guasti, P. (2019). The State as a Firm: Understanding the Autocratic Roots of Technocratic Populism. East Eur. Polit. Societies 33 (2), 302–330. doi:10.1177/0888325418791723

Butler, J. (1988). Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory. Theatre J. 40 (4), 519–531. (Dec.1988)The Johns Hopkins University Press. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3207893. doi:10.2307/3207893

Castaldo, A., and Verzichelli, L. (2020). Technocratic Populism in Italy after Berlusconi: The Trendsetter and His Disciples. PaG 8 (4), 485–495. doi:10.17645/pag.v8i4.3348

Casullo, M. E. (2020b). “Populism as Synecdochal Representation: Understanding the Transgressive Bodily Performance of South American Presidents,” in Populism in Global Perspective (London: Routledge).

Casullo, M. E. (2020a). The Body Speaks before it Even Talks: Deliberation, Populism and Bodily Representation. J. Deliberative Democracy 16 (1). Article 1. doi:10.16997/jdd.380

Casullo, M. E. (20182018). The Populist Body in the Age of Social Media: A Comparative Study of Populist and Non-populist Representation, 257. Brisbane: International Political Science Association Conference.

de la Torre, C. (2013). Technocratic Populism in Ecuador. J. Democracy 24 (3), 33–46. doi:10.1353/jod.2013.0047

EuroZprávy.cz. 2020. Schůzka V Restauraci: Prymula Má Právní Analýzu Svého Chování, Připouští Jen Politickou Chybu. EuroZprávy.Cz. Available at: https://eurozpravy.cz/domaci/zdravotnictvi/schuzka-v-restauraci-prymula-ma-pravni-analyzu-sveho-chovani-pripousti-jen-politickou-chybu.55122bfb/(Accessed 2020, October 27)

Goffman, E. (1959). The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group.

Government of the Czech Republic Due to the Spread of the Coronavirus the Government Has Declared a State of Emergency and on 12 March 2020 Further Tightened Preventive Measures. (2020)March 12). [Press release]. Accessed June 29, 2021, Available at: https://www.vlada.cz/en/media-centrum/aktualne/due-to-the-spread-of-the-coronavirus-the-government-has-declared-a-state-of-emergency-and-on-12-march-2020-further-tightened-preventive-measures-180278/

Guasti, P., and Buštíková, L. (2020). A Marriage of Convenience: Responsive Populists and Responsible Experts. PaG 8 (4), 468–472. doi:10.17645/pag.v8i4.3876

Guasti, P. (2020b). Populism in Power and Democracy: Democratic Decay and Resilience in the Czech Republic (2013-2020). PaG 8 (4), 473–484. doi:10.17645/pag.v8i4.3420

Guasti, P. (2020a). The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Central and Eastern Europe. Democratic Theor. 7 (2), 47–60. doi:10.3167/dt.2020.070207

Havlík, V. (2019). Technocratic Populism and Political Illiberalism in Central Europe. Probl. Post-Communism 66 (6), 369–384. doi:10.1080/10758216.2019.1580590

Havlík, V., and Voda, P. (2018). Cleavages, Protest or Voting for Hope? the Rise of Centrist Populist Parties in the Czech Republic. Swiss Polit. Sci. Rev. 24 (2), 161–186. doi:10.1111/spsr.12299

Heinisch, R., and Saxonberg, S. (2017). “Chapter 12: Entrepreneurial Populism and the Radical Centre: Examples from Austria and the Czech,” in Political Populism: A Handbook. Editors R. C. Heinisch, C. Holtz-Bacha, and O. Mazzoleni. 1st ed. (Baden-Baden: Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co. KG), 209–226. doi:10.5771/9783845271491-209

Hendriks, C. M., Duus, S., and Ercan, S. A. (2016). Performing Politics on Social media: The Dramaturgy of an Environmental Controversy on Facebook. Environ. Polit. 25 (6), 1102–1125. doi:10.1080/09644016.2016.1196967

iROZHLAS 2020 Chci Dát Prostor Pro Řešení epidemie.‘ Ministr Vojtěch Rezignoval Na Funkci Ministra Zdravotnictví. iROZHLAS. Available at: https://www.irozhlas.cz/zpravy-domov/adam-vojtech-koronavirus-cesko-druha-vlna-koronaviru-mimoradna-opatreni-rousky_2009210808_dok. (Accessed 2020, September 21)

Kabrhelová, L. 2021 Je to Těžší Než Jen Zveřejnit Video Premiéra, Říká O Krizové Komunikaci Vlády Expertka Na Marketing. iROZHLAS. Available at: https://www.irozhlas.cz/zpravy-domov/podcast-vinohradska-12-denisa-hejlova-komunikace-vlada-andrej-babis_2102030600_mpa (Accessed 2021, February 3)

Laclau, E., and Mouffe, C. (1985). Hegemony and Socialist Strategy: Towards a Radical Democratic Politics. London: Verso.

Lokšová, T., and Hoření, K. 2020 Galanterie Jako Součást Kritické Infrastruktury Státu. A2larm. Available at: https://a2larm.cz/2020/03/galanterie-jako-soucast-kriticke-infrastruktury-statu/Accessed 2020, March 24).

Luebke, S. M. (2020). Political Authenticity: Conceptualization of a Popular Term. The Int. J. Press/Politics 26, 635–653. doi:10.1177/1940161220948013

Macková, A., Štětka, V., Zápotocký, J., and Hladík, R. (2017). “Who Is Afraid of the Platforms?: Adoption of and Strategies for Use of Social media by Politicians in the Czech Republic,” in Social Media and Politics in Central and Eastern Europe (London: Routledge).

Marichal, J. (2013). Political Facebook Groups: Micro-activism and the Digital Front Stage. Fm 18. doi:10.5210/fm.v18i12.4653

McEnchroe, T. 2020. “There Is No Reason to Panic”—Says Health Minister about Karviná COVID-19 Outbreak. Radio Prague International. Available at: https://english.radio.cz/there-no-reason-panic-says-health-minister-about-karvina-covid-19-outbreak-8685668. (Accessed 2020, July 7)

Moffitt, B. (2015). How to Perform Crisis: A Model for Understanding the Key Role of Crisis in Contemporary Populism. Gov. Oppos. 50 (2), 189–217. doi:10.1017/gov.2014.13

Moffitt, B. (2016). The Global Rise of Populism: Performance, Political Style, and Representation. Stanford University Press. Available at: http://www.sup.org/books/title/?id=25175

Nováková, B. 2020 Vědci Popsali, Jak Se Covid-19 Z Jedné Akce Roznesl Mezi Až 20 000 Lidí—Seznam Zprávy. Seznam Zprávy. Available at: https://www.seznamzpravy.cz/clanek/anatomie-jednoho-ohniska-geneticka-data-koronaviru-ukazuji-jak-se-siri-117332 (Accessed 2020, August 26).

OECD (2020). “Czech Republic,” in OECD Tourism Trends and Policies 2020 (Paris: OECD Publishing). doi:10.1787/6b47b985-en

Ostiguy, P. (2017). “Populism,” in The Oxford Handbook of Populism. Editors C. R. Kaltwasser, P. Taggart, P. O. Espejo, and P. Ostiguy (Oxford University Press), 1. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198803560.013.3

Palonen, E. (2021). Democracy vs. Demography: Rethinking Politics and the People as Debate. Thesis Eleven, 072551362098368. doi:10.1177/0725513620983686

Palonen, E. (2018). Performing the Nation: the Janus-Faced Populist Foundations of Illiberalism in Hungary. J. Contemp. Eur. Stud. 26 (3), 308–321. doi:10.1080/14782804.2018.1498776

Palonen, E. (2019). “Rhetorical-Performative Analysis of the Urban Symbolic Landscape: Populism in Action,” in Discourse, Culture and Organization: Inquiries into Relational Structures of Power. Editor T. Marttila (Springer International Publishing), 179–198. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-94123-3_8

Peck, E., Freeman, T., Six, P., and Dickinson, H. (2009). Performing Leadership: Towards a New Research Agenda in Leadership Studies. Leadership 5 (1), 25–40. doi:10.1177/1742715008098308

Perottino, M., and Guasti, P. (2020). Technocratic Populism à la Française? The Roots and Mechanisms of Emmanuel Macron's Success. PaG 8 (4), 545–555. doi:10.17645/pag.v8i4.3412

Prague Morning 2020a. Could Czech’s Measure to Fight Coronavirus Save Thousands of Lives. Available at: https://praguemorning.cz/could-czechs-measure-to-fight-coronavirus-save-thousands-of-lives-2/. (Accessed 2020, April 4).

Prague Morning. 2020b. Czech Republic Exceeds 3,000 Daily COVID-19 Cases for First Time. Available at: https://praguemorning.cz/czech-republic-exceeds-3000-daily-covid-19-cases-for-first-time/. (Accessed 2020, September 18)

Právě on vyhlašuje nejpřísnější opatření: Pod rouškou tmy si Prymula bez roušky vyrazil Do restaurace! 2020. Blesk.cz. Available at: https://www.blesk.cz/clanek/zpravy-koronavirus/659071/prave-on-vyhlasuje-nejprisnejsi-opatreni-pod-rouskou-tmy-si-prymula-bez-rousky-vyrazil-do-restaurace.html (Accessed 2020, October 23)

Protiepidemický systém ČR. (2021). onemocneni-aktualne.mzcr.cz. Accessed June 28, 2021 Available at: https://onemocneni-aktualne.mzcr.cz/pes.