- MZES University of Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany

Research indicates that ideological congruence between citizens and political parties increases the likelihood of turning out to vote. But does this relationship also hold in times of economic crisis? In this study, I investigate whether economic conditions moderate the effect of voter–party representation on turnout. I argue that ideological congruence has significant effects on electoral participation during “normal” times, but these are even more relevant when citizens face economic hardship. Thus, in times of crisis, citizens are more likely to vote if they have a party that represents their position. I empirically test this argument by analyzing large-scale cross-national survey data from the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (CSES). Findings bear important implications for the relationship between economic conditions and the functioning of modern democracies.

Introduction

One of the most intriguing questions in political science research is what makes citizens vote. Several scholars have dedicated their endeavors to study what drives citizens to participate in elections even when this action is very unlikely to be pivotal for the electoral results. At the same time, understanding citizens’ decision to vote transcends the mere academic interest because participation is one of the necessary conditions of democracies (Smets and van Ham 2013). By voting, citizens prevent democratic institutions to be monopolized by the most privileged individuals (Parvin 2018) and incentivize the adoption of policies addressed to reduce inequalities as representatives would seek to achieve the political aims of their electorate (Plotke 1997). Thus, high electoral participation is often seen as a symptom of a healthy democracy.

While understanding what makes citizens more or less likely to vote has been widely studied by political scientists, it is still a controversial topic because experts do not agree on what factors drive turnout (Blais 2006; Smets and van Ham 2013; Cancela and Geys 2016; Frank and Martínezi Coma 2021). Scholars have offered different sets of explanations of what makes voters more likely to vote, but while some have just focused on the individual characteristics that make citizens more willing to vote (Smets and van Ham 2013), others have paid attention to the institutional settings in order to assess the differences in voter turnout (Frank and Martínezi Coma 2021). Thus, experts have often offered answers of why people participate in elections that are limited to either micro- or macrolevel factors. Consequently, most explanations of citizens’ turnout assume that individual characteristics affect electoral participation irrespective of the context, while others suggest that the effect of institutional settings in turnout is the same for all individuals (Anduiza, 2002).

Nevertheless, there are studies that indicate the necessity to approach electoral participation by analyzing the interaction between the characteristics of voters and contextual factors (Anduiza, 2002; Blais 2006; Franklin 2004). In this respect, recent trends point toward broadening of the approach of the analysis of what moves citizens’ decision to participate or to abstain, and, as Schmitt et al. (2021) indicate, micro and macro perspectives can be complimentary, and the impact of individual factors on turnout might be context dependent.

In this study, I focus on the impact of the economic context on the relationship between turnout and congruence understood as the inverse of the ideological distance. Hence, the higher the congruence between a citizen and a political party, the lesser the ideological distance between them. Ideological congruence between a voter and a party has been proven to be a predictor of citizens’ turnout because if they perceive their political stances are represented by a political party—that is, if citizens understand that there are parties close to their ideological position—they are less likely to abstain in an election (Lefkofridi et al., 2014; Schäfer and Debus 2018; Navarrete 2020).

Is the relationship between congruence and electoral participation moderated by macroeconomic conditions? Is individual turnout equally affected by economic adversity irrespective of the electoral menu? In this respect, the contradictory studies analyzing the impact of the economy on turnout (Blais 2006; Passarelli and Tuorto 2014; Weschle 2014) would be better assessed when also considering microlevel factors that make some citizens’ behavior more or less likely to be affected by contextual changes. If the pursuit of policy representation is relevant to mobilize voters, it is worth considering that in a context of economic turbulences, citizens would more easily acquire information about what policies represent each party as there would be more information available (Marinova and Anduiza 2020), and, consequently, voters have a better understanding of the electoral menu and have more resources to make their choice, which leads to a higher likelihood of turnout (Smets and van Ham 2013; Çakır 2021; Park 2021). Similarly, when the national economy is bad, citizens might have more incentives to have their interests represented in the national parliament because they have more to lose, and, in such a context, having a congruent option in the choice set would increase the utility that they gain from voting even more. Hence, in a context of economic turmoil, citizens would be more willing to participate if there is a political option that is ideologically aligned with them.

On the contrary, some authors argue that economic adversity contributes to citizens’ withdrawal from politics because they have concerns that make them focus on their bread-and-butter problems and alter their social relationships, increasing the costs of being politically active and diluting the motivation to punish or reward the actions and policies of political parties (Rosenstone 1982). For all this, in such a scenario, it is likely that congruence between an individual and different parties competing in an election will be less effective in mobilizing citizens to the polls.

This research work discusses the extent to which changes in the gross domestic product (GDP) and in the level of unemployment impact on the prominence of congruence as a predictor of electoral participation and answers the question of whether citizens are equally likely to vote when there is at least one party representing their policy preferences in a context of economic distress than in a more prosperous scenario. Results suggest that the likelihood of turning out to vote is more affected by ideological congruence when unemployment increases.

The analysis discussed here reconciles different approaches to the study of electoral participation because it includes micro- and macrolevel factors that contribute to explain why citizens vote. Moreover, this research work shows how the likelihood of voting is conditioned by both the congruence with the electoral menu and the economic context that can be seen as a starting point to disentangle the ambiguity of empirical results linking economic results and turnout. If the mobilizing effect of congruence between a voter and a party is affected by macroeconomic conditions, the decision to vote in an election is not equally affected by the economic context. Voters’ reaction to economic changes is also affected by the choice set they have in a given election, and this evidence contributes to understand the contradictory findings in research assessing the impact of economic indicators on electoral participation.

The article proceeds as follows. In the next section, I present the main argument and discuss the possible causal mechanisms and theoretical expectations. Then I introduce the data and methods. Results and main findings are discussed in the fourth section. At Last, I comment the main conclusions and limitations of this research.

The Argument

There is abundant research on how the state of the economy determines electoral results as voters reward or punish the government depending on the economic performance (Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier 2000). However, most of the “economic voting” literature focuses on vote choice and analyses on how the economic situation affects turnout are more scarce (Önnudóttir et al., 2021, 133; Weschle 2014, 39). Furthermore, scholarship disagrees about the relationship between electoral participation and the economic situation and there is strong evidence supporting contradicting hypotheses. This way, some authors have emphasized that in a context of economic distress, citizens are more motivated to punish the action of political parties and, hence, are more willing to participate when they can blame the government for the economic situation (Arceneaux 2003; Burden and Amber, 2014). Similarly, economic adversity would make citizens more active politically as they would have more incentives to have their interests represented in their parliament (Passarelli and Tuorto 2014).

Other authors deny the mobilizing effects of a worsening of the economy and support the so-called withdrawal hypothesis, according to which the likelihood of voting decreases when citizens face economic difficulties (Rosenstone 1982; Park 2021). In such a context and according to this approach, citizens would be more worried about their personal well-being, and they are more likely to become indifferent to politics and voting has a lower utility to them.

The controversy about the actual effect of the economy on turnout has reached the point at which some authors state that “there is no clear relationship between the economic conjuncture and turnout” (Blais 2006, 117 also cited in Weschle 2014, 41). Nevertheless, the apparent inconsistent findings might be the result of a limited approach that includes only aggregate-level data.

Recent research works including micro- and macrolevel predictors of votes conclude that a worsening of the economic conditions is associated with higher turnout (Önnudóttir et al., 2021). However, this seems to contradict the evidence for some countries after the crisis of 2008. As an example, electoral participation decreased more in the Southern European countries that were also more harshly hit by the crisis (Bosco and Verney 2012). In this respect, scholars have offered different explanations of why citizens abstain instead of voting for an alternative. Kriesi (2012) proposes that abstention is one of the options of protest for discontented voters who perceive that no existing party would do it better and, because citizens are “represented through and by parties” (Sartori 1968, 471), they would choose to exit as a protest against the lack of representation. This argumentation implies that the extent to which citizens see their policy preferences represented by political parties is a relevant predictor of turnout and, consequently, party supply matters not only to explain whom citizens vote but also whether they do it or not. Then, the impact of the national economy on turnout depends also on the political alternatives (Anderson 2000; Weschle 2014). This way, when economic indicators worsen, some voters would be more persuaded to vote while others would be more willing to abstain depending on the available options in the electoral menu. This could explain why competing claims about the role of the economy in electoral participation have found supporting evidence. These contradicting arguments are not necessarily mutually exclusive because some voters could be moved to vote when the economic performance is bad, while others might be dissuaded from participating in the elections (Weschle 2014, 41). In this respect, Weschle (2014, 48) found out that “different people can react differently to the same economic conditions” and that some will change their vote choice and others will change their turnout behavior depending on whether they find alternative parties to vote for or not. Thus, it is worth considering that the extent to which citizens see their policy preferences represented in the electoral menu is an important factor of turnout that would matter more or less depending on contextual factors such as a situation of economic turmoil.

For decades, scholars have used the spatial theory of party competition to explain citizens’ electoral choices. Since Downs’ (1957) seminal work, experts of electoral behavior have paid attention to ideological distances to explain how voters decide between several options. Concerning turnout, Adams et al. (2006) conclude that abstention is largely policy-based because citizens who perceive all parties to be too distant to their ideology or who see parties as too similar are less likely to cast a vote. Their research focused on the United States and they analyzed a system in which citizens choose between two options, but research on multiparty systems has also emphasized that lack of congruence with the electoral menu is associated with abstention (Lefkofridi et al., 2014; Schäfer and Debus 2018; Navarrete 2020). If parties are close to one’s position in the ideological scale, citizens perceive the pursuit of policy representation as an incentive that reduces the costs of voting. If parties are too distant from a voter’s position, they might perceive that they get little benefit from voting.

The mobilizing effect of congruence between an individual and a party indicates that the pursuit of policy representation is relevant to motivate voters’ participation, but this relationship between congruence and turnout is conditioned by the context. Congruence mobilize voters in proportional systems but not in disproportional ones (Lefkofridi et al., 2014). Also, the degree of self-rule of a region moderates the effect of party–voter congruence on turnout because the likelihood of voting in regional elections when there is a congruent option increases the more welfare competences the region has (Navarrete 2020). This evidence suggests again that changes in macrolevel factors do not necessarily have the same impact on all individuals and party–voter congruence matters more in some contexts.

In times of economic crisis, citizens become more attentive and informed and are more willing to respond to the bad situation (Burden and Amber, 2014). Also, economic hardship boosts information, and citizens learn more about parties’ policy positions (Marinova and Anduiza 2020). In such a context, in which citizens are more concerned about the situation, turnout is a powerful mechanism to express support or dislike toward the policies implemented by the government. Therefore, with better informed citizens with more incentives to pursuit policy representation, the theoretical expectation is that congruence between individuals and the political parties competing in an election matters more as a predictor of turnout than when the state of the economy is not bad. Furthermore, those who cannot find any political option in the choice set that is ideologically close to them would be more likely to be indifferent to politics and would find an even lower utility in voting. Therefore, I hypothesized that the economic context moderates the impact of congruence on electoral participation. Thus, citizens who perceive that there is at least one party close to their position will be more likely to vote while those who perceive all parties to be distant in the ideological scale will have higher likelihood of abstaining and these differences will be more evident in a plummeting economy than in a prosperous economy.

It could also be the opposite. Citizens weigh more economic adversity than prosperity and respond more to negative news and perceptions (Burden and Amber, 2014). Thus, the motivation to vote is higher in a context of economic distress than in a context of economic prosperity, and the desire to punish the action of certain parties might be higher than the incentives citizens have to see their policy preferences represented in the parliament. It could also happen that the bad economic performance would make some citizens disappointed with their ideologically closest party what would make them choose other options or opt for abstention. Then, it can also be hypothesized that when the economy is bad, there is no mobilizing effect of congruence and its association with turnout is not relevant in times of economic turmoil.

Data and Methods

Because the main aim of this research is to gauge the extent to which the effect of ideological congruence between individuals and parties on electoral participation is moderated by the economic situation, both micro- and macrolevel factors are considered as predictors of individual turnout. For this reason, I rely on data from the first four modules of the CSES which provide survey data on citizens’ sociodemographics, political behavior, and preferences together with a set of macrolevel variables on economic performance. These data allow assessments on how citizens are more prone to participate in elections in which the political parties are closer to their ideological positions and depending on the economic context.

This research is innovative in combining individual and contextual variables to explain turnout. The dependent variable is dichotomous and takes value 1 when the respondent voted and 0 otherwise. At the micro-level, the main explanatory variable is the ideological congruence between the individual and the parties’ supply. This measure is calculated following the formulation used by Lefkofridi et al. (2014, 296) according to which ideological congruence is the absolute distance in the left–right scale between an individual and their perceived ideologically closest party, all this multiplied by −1 for a better interpretation of the results because the higher the number, the higher the congruence. Thus, this variable takes values between −10, that indicates that the respondent perceives the party supply as completely distant to their ideology, and 0 that it is the value this variable takes when there is at least one party in the political menu that, based on respondents’ perceptions, locates on the respondent’s position on the ideological scale.1

The main hypothesis to be tested here deals with the mediating effect of economic downturns on the relationship between ideological congruence with the electoral supply and individual electoral participation. Thus, the main challenge is to determine how the economic situation can be measured with objective economic indicators. Following the literature on the impact of economic conditions on vote, GDP growth, and unemployment are relevant determinants of electoral turnout as they are often seen as the result of the government policies (see Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier, 2000). This way I use the macro variable collected in the CSES data on gross domestic product (GDP) growth of the country as reported by the World Bank and calculated the difference in the GDP in the year of the election compared to the previous year to estimate whether there was an increase or a decrease of the GDP. Thus, if the change in the GDP takes negative values, it means that the GDP declined. Similarly, I also use the macrolevel variables included in the CSES data to calculate the difference in the level of unemployment in the year of the election with respect to the previous year. Therefore, when the variable of change in unemployment takes positive values it means that the unemployment rate in the country increased in the year of the election.

The economy affects electoral behavior only when citizens perceive the economic changes. A minimal fall in the GDP of a country might not be understood as a symptom of economic crisis. Similarly, the increase in unemployment in the year of the elections might have not been noted by citizens if the employment rate fell significantly right after the elections. Furthermore, there are severe differences regarding the magnitude that make citizens feel that they are in a period of economic turmoil as there are countries in which small increases in the unemployment rate are not seen as a big problem because the structure of their job market makes them more vulnerable to small fluctuations and only big changes or the prolongation in time of the situation have a significant impact on citizens’ economic perceptions. For this reason, I wanted to include subjective evaluations of the economy but questions on these matters were not systematically included in all the four modules of the CSES. As a solution I use two dummies, one for GDP and one for unemployment, that take value 1 when the situation has worsened during at least two consecutive years. The motivation is that small changes in the economy might take time to affect citizens’ general perceptions, but if there has been at least 2 years in which the economic indicators have worsened, citizens will be mostly aware of a nonoptimal situation for the national economy.

As controls at the microlevel I included variables that proved to be relevant in explaining individual turnout such as age, gender, education, and ideological extremism (Lefkofridi et al., 2014; Navarrete 2020)2. Ideological extremism is computed as a dummy that takes value 0 when the individual declares a moderate left–right position and 1 when the respondent’s ideological stance is at the extreme of the ideological scale, that is, when an individual locates herself/himself in positions 0–2 or 8–10 in the left–right scale. This variable is also interacted with congruence because there is evidence that citizens with extreme ideology are even more likely to vote when there is at least one party that is close to their ideological position (Lefkofridi et al., 2014). Because a worsening of the economy can drive some individuals to ideological radicalization, I included the interaction between ideological extremism and congruence in order to be sure that the results are not masked by a radicalization of the society.

At the macrolevel, there is evidence that drivers of individual turnout differ between new and consolidated democracies (Karp and Banducci 2007; Gallego et al., 2012; Smets and van Ham 2013). Hence, I included a dummy variables that takes value 1 when the election was held in a new democracy and 0 for consolidated regimes. To identify new and consolidated democracies, I follow the study by Gallego et al. (2012), in which they consider new democracies those cases in which nine or fewer democratic elections have taken place. This way, there are countries in the sample whose first elections are coded with value 1 while the country is considered a consolidated democracy in the most recent electoral processes.

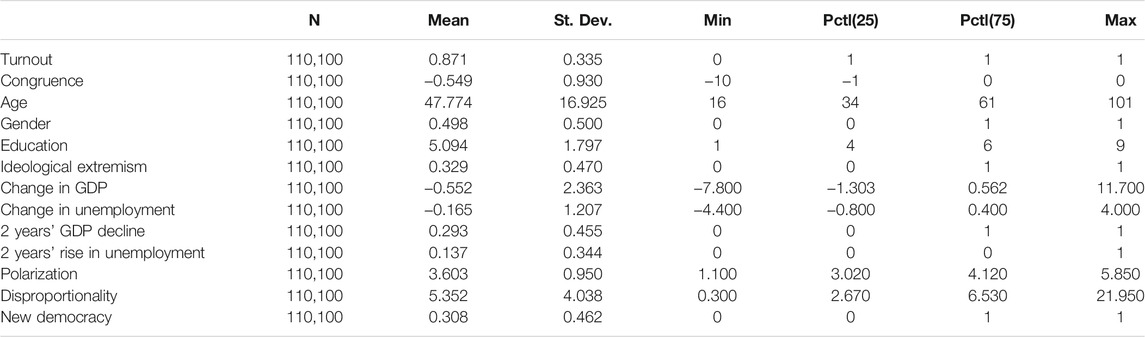

I also included as control variables two relevant institutional factors: polarization and disproportionality of the electoral system. High party system polarization increases what is at stake for voters (Çakır 2021, 6), it is associated with higher turnout rates (Dassonneville and Çakır 2021), and ideological proximity is a better predictor of vote choice the higher the ideological disagreement between parties (Lupu 2015; Navarrete 2021). Thus, I included as a control variable the measures of party system polarization calculated by Dalton (2018) for the first four modules of the CSES3. Regarding the disproportionality of the electoral system, I already mentioned that Lefkofridi et al. (2014) showed that the effect of congruence on turnout was conditioned by this factor, and then I included measures of the disproportionality of the electoral system and used data from the election indices elaborated by Gallagher (2019). More details on the selected variables can be found below in Table 1.

Countries with compulsory voting were not included in the analysis because this is such a powerful incentive for electoral participation that voter’s characteristics are less relevant to explain turnout than in countries in which abstaining do not carry sanctions (Blais 2007; Frank and Martínezi Coma 2021; Lachat and Teperoglou 2021). Similarly, I only included in the analysis countries that at the time of the election have a score higher than 3 on the Freedom House democracy ratings. Considering this and after the selection of variables, the final dataset contains post-electoral studies from 33 countries and 86 elections ranging from 1996 to 2017.4

Taking into account the dichotomous-dependent variable and the individual and contextual predictors, I run logistic multilevel regression models with varying intercepts at two levels, with the grouping levels being the country and the election year (Gelman and Hill 2006). I run different models in which I subsequently include the interactions of the variables on the economic conditions with congruence, combining one variable of GDP and one variable of unemployment to avoid problems of multicollinearity. Therefore, I do not include in a same model the two variables of GDP and the two variables of unemployment. Results are discussed in the next section.

Results

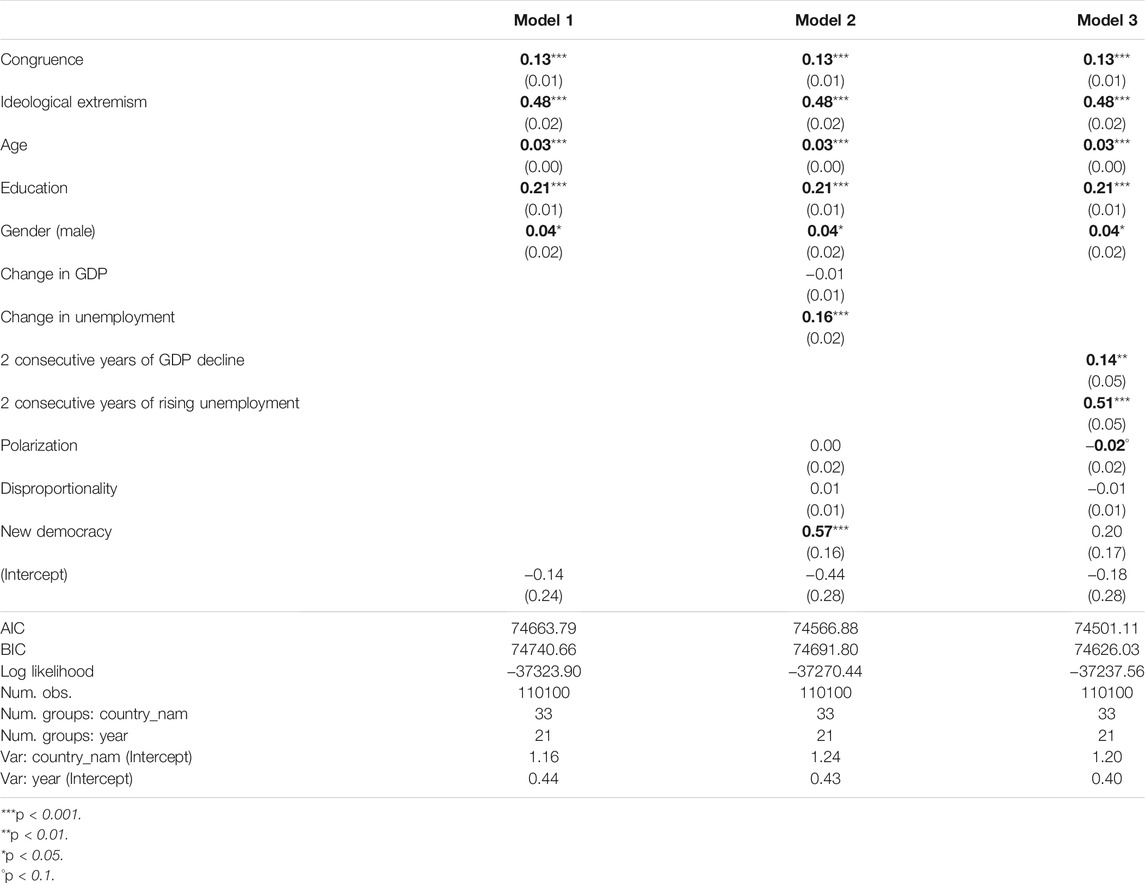

The aim of this research was to assess the extent to which economic context is likely to affect the impact of ideological congruence between an individual and the different political parties competing in an election on the decision of voting or abstaining. There are two competing theoretical expectations: on the one hand, it can be expected that economic downturns make ideological congruence more prominent as a determinant of individual turnout but, on the other, it can also be hypothesized that the relevance of congruence as a predictor of electoral participation decreases in case of economic turmoil. In testing these hypotheses, the first step is to estimate the effect of the selected variables in electoral participation without the interaction terms. Thus, I first run three models (see Table 2) that set up the baseline models that are consistent with previous literature and allow a straightforward interpretation of the first results. At the microlevel, control variables indicate that older and better educated citizens are more likely to vote as well as those with extreme ideology. Concerning the main independent variable, citizens are more likely to participate in elections the closer the political parties are to their ideological position (Lefkofridi et al., 2014; Schäfer and Debus 2018; Navarrete 2020) as a higher congruence between the individual and the ideologically closest party has a significant positive effect in all three models. This indicates that this effect is constant even after considering contextual factors.

With respect to the contextual variables included in models 2 and 3 in Table 2, in general, the probability of voting increases the harder the economic conditions, but this is not the case when just the GDP of that year is affected. As shown in model 2 in Table 2, GDP growth does not affect turnout: however, when there are at least two consecutive years of decline of the GDP, citizens are more likely to vote (see model 3 in Table 2). This is because citizens might need more time to perceive the impact of growth in the economy as the social consequences of changes in the GDP take more time to materialize and citizens are mostly uninformed about macroeconomics (Marinova and Anduiza 2020). On its side, changes in the unemployment rate do have an effect on the decision to vote, which confirm previous literature that pointed to individuals being more aware of the state of the economy when it affects unemployment rates (Marinova and Anduiza 2020).

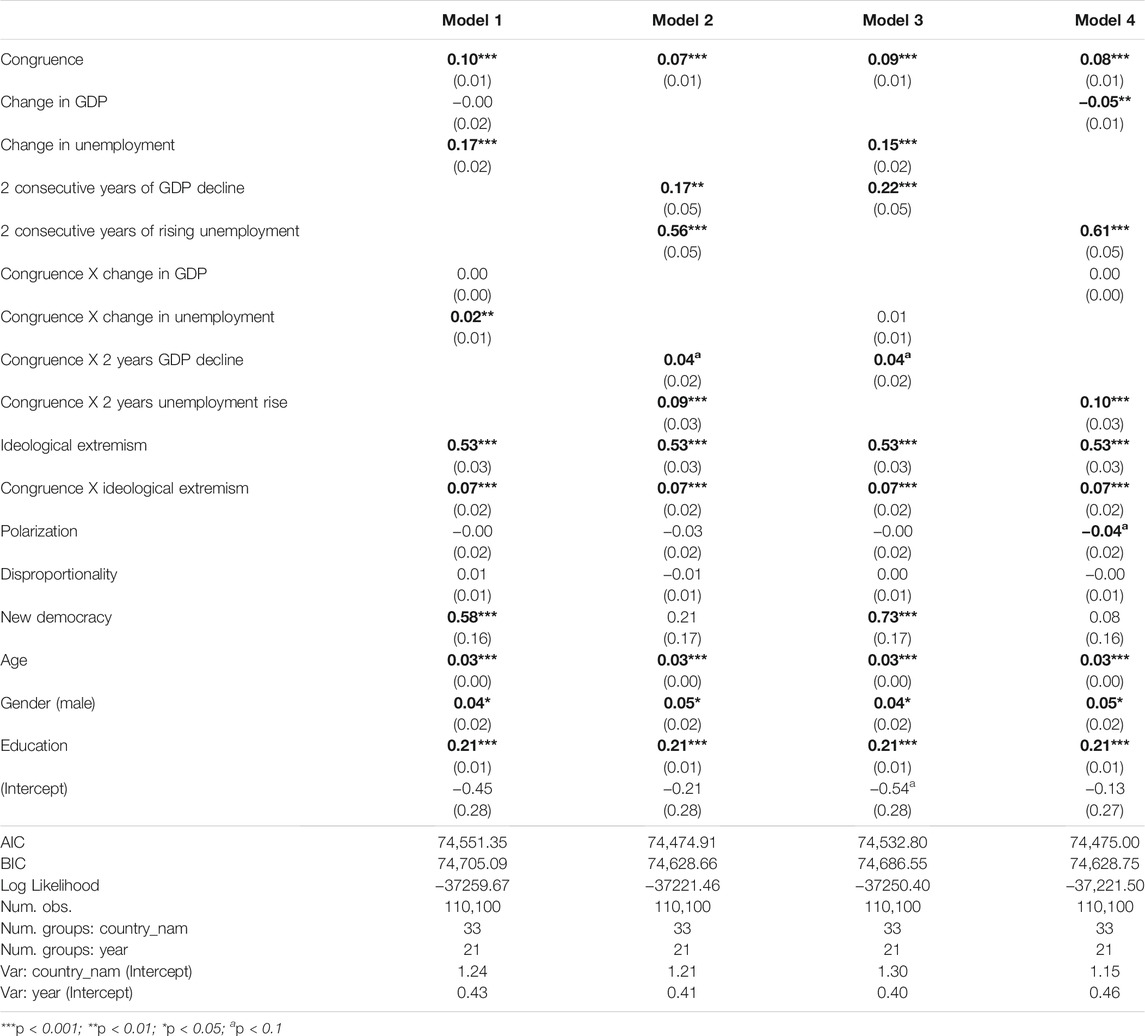

In order to capture the effect of the two selected symptoms of economic crisis—these are, evolution of the GDP and increase of the unemployment rate—I run four different multilevel logistic regression models combining the variables of GDP growth and unemployment and their interaction with congruence. Thus, this analysis is not restricted to just one feature of economic performance and allows a more complete interpretation of how economic crisis affects citizen’s behavior.

Results shown in Table 3 support the theoretical expectation of congruence being more prominent in a scenario of economic adversity. When there is an increase of the level of unemployment, citizens are more likely to participate in elections no matter the evolution of the GDP. As shown in all the models, both the increase of the unemployment rate and having at least two consecutive years of rising unemployment move citizens to vote. Growth, however, is less relevant as a predictor of turnout because changes in the GDP did not reach statistical significance in model 1 in Table 3, and it has a modest significant effect in model 4 in Table 3 when the variable of 2 years of increase of the unemployment rate is included. In models 2 and 3 in Table 3, it can be seen that having at least two consecutive years of GDP decline when considering changes in the unemployment rate does indeed make citizens more likely to vote, suggesting that individuals need more time to perceive the consequences of a decline of the GDP.

The interaction terms also offer interesting insights as the effect of congruence between the voter and the electoral menu on turnout is mostly affected by the unemployment rate and not so much by the GDP. To be more precise, in a context in which the unemployment rate increases or in context in which there were at least 2 years of consecutive rise of unemployment, congruence matters more as a predictor of citizens’ decision of voting. In models 1, 2 and 4 in Table 3, the interaction of the variables of unemployment with congruence shows statistically significant coefficients, indicating a positive impact on turnout. Nevertheless, it has to be highlighted that the values of these variables are limited, meaning that it is actually very unlikely to have huge increases in the unemployment in just 1 year and the significance of these results might be taken with a grain of salt.

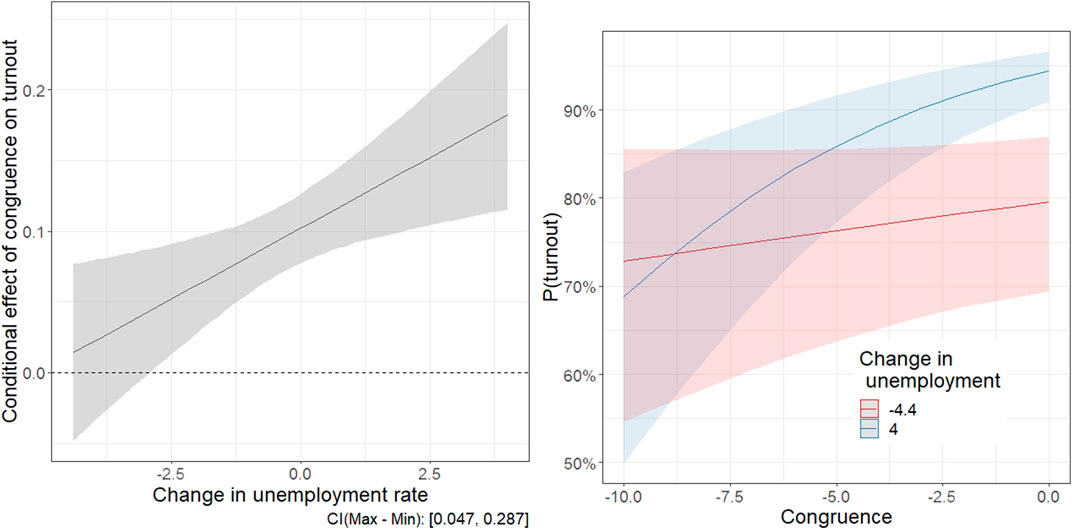

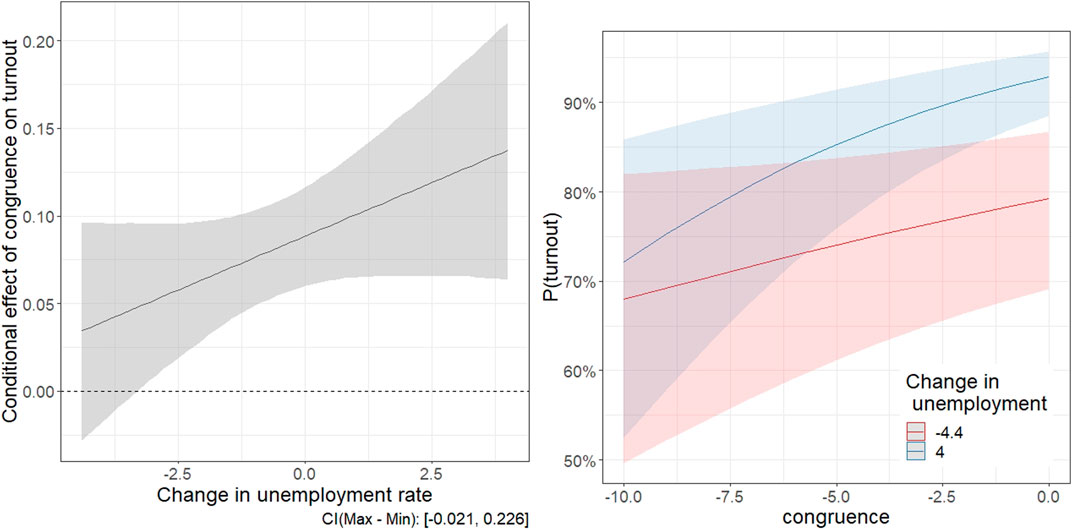

A graphical representation of these results provides a better understanding of the actual effect of the level of unemployment and congruence on electoral participation because the coefficients are significant but not of a large magnitude. Figures 1, 2 (plotted on the basis of models 1 and 3 in Table 3 respectively) show the conditional effects (left panel) and the predicted probabilities of voting (right panel) based on congruence and on the changes in the unemployment rate. It can be seen in both figures that in a context in which the unemployment rate decreases more than 3 points, the effect of congruence on turnout is not significant. This means that, in a context of accelerated job creation, congruence does not work well as a predictor of electoral participation. However, the effect of ideological proximity between parties and the voter is positive the more the economy worsens. Attending to the predicted probabilities (right panel of Figures 1, 2), when the level of unemployment decreases—that is, when the employment rate increases—the slope is almost horizontal, indicating that in a context of job creation, ideological congruence between the voter and parties matter less to the decision of participating.

FIGURE 1. Conditional effects of congruence on turnout and predicted probabilities of turnout based on congruence and moderated by change in the unemployment rate (model 1 in Table 3). Note: 95% confidence intervals.

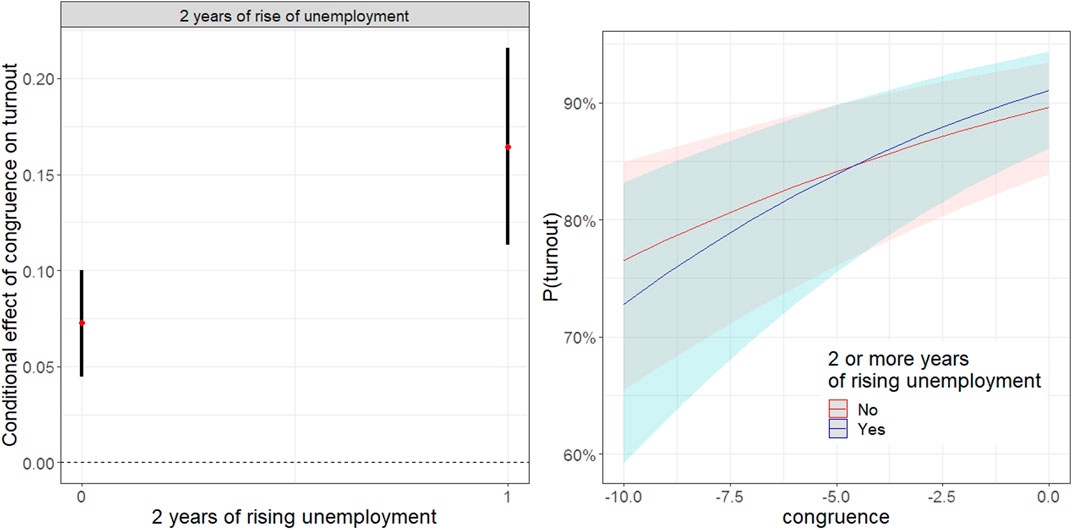

FIGURE 2. Conditional effects of congruence on turnout and predicted probabilities of turnout based on congruence and moderated by change in the unemployment rate (model 3 in Table 3). Note: 95% confidence intervals.

On the contrary, when unemployment increases, the slope is steeper and changes more as a function of congruence, which suggests that in a context of rising unemployment, citizens’ decision to vote depends more on congruence. Attending to the confidence intervals, it has to be noted that the probabilities of turning out in an election are not significantly different when the distance between the voter and the parties in the electoral menu is small, so these results must be cautiously interpreted because it is shown that only a high level of job destruction and an almost total congruence make the predicted probabilities of voting significantly higher than in a booming job market. Together with this, predicted probabilities in Figures 1 and 2 were plotted with estimations for extreme values of changes in unemployment, that is, I took the highest rise (Iceland 2009) and decline (Estonia 2011) in the unemployment rate in 1 year so, despite highest values would make the differences more evident, it is very unlikely that a normal economy, even an economy in crisis, could increase or reduce its unemployment rate in more than 4 points in just 1 year. This implies that less dramatic changes in the level of employment of a country will only modestly moderate the effect of congruence on the probability of turning out, owing to a ceiling effect.

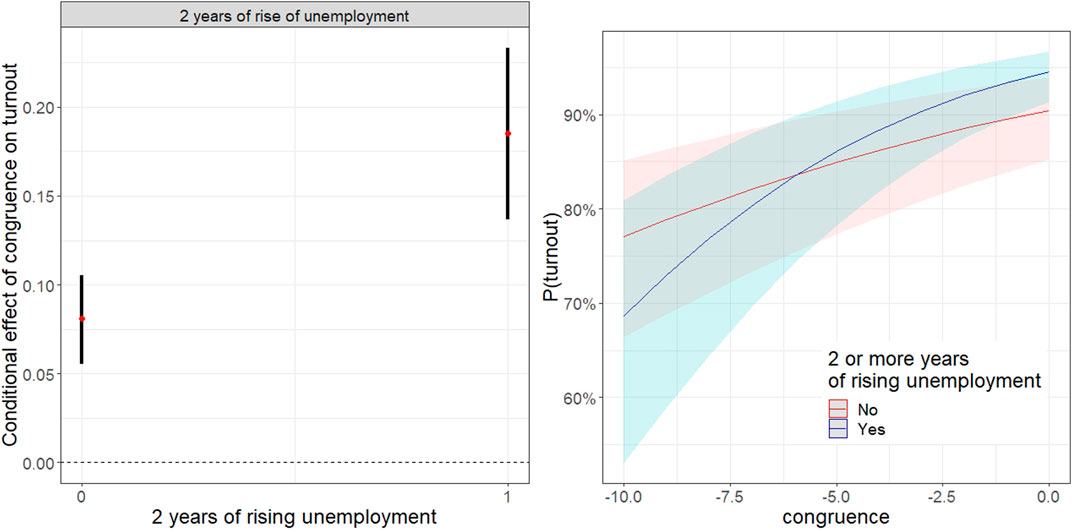

Regarding the effect of having at least 2 years of rising unemployment, conditional effects of congruence on turnout clearly indicate that they are moderated by—therefore conditional on—the situation of the labor market (see left panel of Figures 3, 4). However, the predicted probabilities plotted in Figures 3, 4 show overlapping confidence intervals that prevent the rejection of the hypotheses that motivated this research. The slope for the curves representing a context of 2 years of destruction of employment are indeed steeper but there are not actual differences between the two scenarios as individuals with the same congruence are equally likely to vote in both contexts.

FIGURE 3. Conditional effects of congruence on turnout and predicted probabilities of turnout based on congruence and moderated by at least 2 years of rising unemployment (model 2 in Table 3). Note: 95% confidence intervals.

FIGURE 4. Conditional effects of congruence on turnout and predicted probabilities of turnout based on congruence and moderated by at least 2 years of rising unemployment (model 4 in Table 3). Note: 95% confidence intervals.

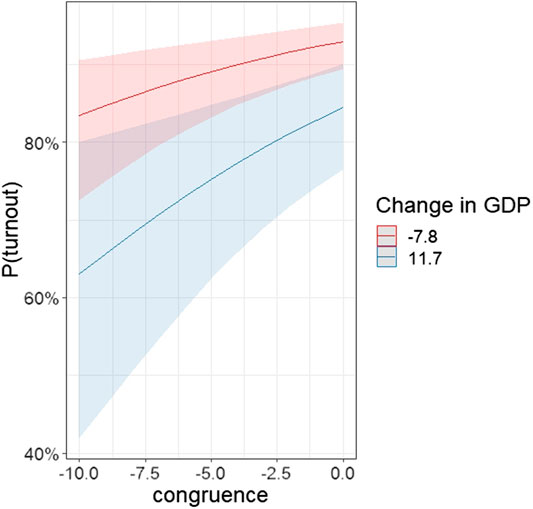

In the light of these graphs, there is empirical evidence to reject the hypothesis of a decreasing effect of congruence as a predictor of electoral participation in a context of economic distress. However, it can be argued that the initial expectation according to which congruence matters more for turnout in a context of economic difficulties is not sufficiently supported. Following Brambor et al. (2006) and Schäfer and Debus (2018), substantive effects of interaction terms require the calculation of other estimates, such as marginal effects of predicted probabilities, and the mere interpretation of the significance of the coefficients is problematic so I also calculate the predicted probabilities of turning out in an election depending on the ideological congruence and on the basis of changes of the GDP. As shown in Figure 5, in which predictions are calculated with 90 percent confidence intervals, the slope is not significantly different and the probability of voting can be the same no matter the economic context because there is an overlap between the two confidence intervals.

FIGURE 5. Predicted probabilities of turnout based on congruence moderated by change in GDP (model 4 in Table 3). Note: 90% confidence intervals.

As a robustness check I also run the multilevel logistic models using a broader time perspective and use the changes in the GDP and in the unemployment rate in the last 2 years as independent variables. The interaction between congruence and the economic variables remain statistically significant (see Table A2 in the Supplementary Appendix). These effects also remain with minor changes in analyses including the interaction of congruence with the institutional control variables of party system polarization and disproportionality of the electoral system (see Table A3 in the Supplementary Appendix), which indicates that the moderating effect of the economy on the relationship between congruence and turnout is consistent despite its effects are not always of large magnitude.

Attending to the evidence discussed here, we need a fine-grained analysis that could contribute in better gauging the actual impact of economic conditions on the relationship between electoral participation and congruence between citizens and parties. Results indicate that a worsening of the state of the economy prior to an election does make citizens more willing to vote based on their policy preferences. However, the moderating effect of economic growth and the level of unemployment are so modest that context seems to matter only in extreme situations.

All in all, this research should be considered as a starting point in broadening the scope of studies of electoral participation as it has shown that there is an interplay between micro- and macrolevel factors that affect citizens’ political behavior. It should also serve to remark the importance of using meaningful estimates for the interpretation of interaction terms (Brambor et al., 2006) because the assessment of substantial actual effects require a more refined analysis than just a discussion on the statistical significance of the interaction terms.

Conclusion

Following the economic crisis that started in 2008, several scholars turned their attention to the political consequences of citizens’ discontent. While most of the debate focused on explaining why in such a context of economic uncertainty voters opted for challenger parties, research on the effects of the economic recession on the individual predictors of the decision of voting or abstaining is yet scarce. This article contributes to the literature on electoral participation by analyzing the impact of economic recession on ideological congruence as a predictor of individual turnout.

While recent research has shown that citizens are more likely to vote in an election the more they perceive their policy preferences represented in the electoral menu (Lefkofridi et al., 2014; Schäfer and Debus 2018; Navarrete 2020), whether the economic context can affect the relationship between congruence and individual turnout was yet underexplored. In this research, I have presented complex analyses including micro- and macrolevel variables that point to a moderating effect of unemployment and GDP growth on the impact of congruence between an individual and the parties competing in an election on turnout. In short, economic turmoil with severe effects on unemployment and on GDP growth make ideological distance between citizens and parties more relevant to the decision of voting. Consequently, citizens in a context of economic prosperity better opt for abstaining even when there is a political option that represents their policy stances and are more likely to vote if there is a dramatic worsening of the state of the economy. This might provide an explanation for the support for challenger parties as it is likely that part of their success in the years following the economic crisis is due to the opportunity of mobilizing voters that would have abstained in a less turbulent economic context.

Another contribution of this investigation is that it provides another perspective to the disparity of results assessing the relationship between the economy and electoral participation. Considering the electoral menu and whether citizens see their policy preferences represented by any of the parties competing in an election is relevant in an economy under distress and including this finding in future research about the role of the economy in turnout could lead to less contradicting results.

Better measures of economic performance will contribute to more refine assessments of how the state of the economy affects individual predictors of vote. Further analysis should include more individual variables as the economic context has different impact on different groups and those suffering the economic consequences of the crisis would respond differently than those less personally affected. In this research, I present a broad perspective by including as many elections and countries as possible in order to compare different periods beyond the global economic crisis of the first decade of this century. In doing so, I could not use some individual predictors that would have certainly enriched this analysis due to problems of data availability. Further research might test the hypotheses discussed here in more specific contexts, with less cases but with more information about how those more vulnerable to economic shocks decide whether or not to participate in an election. In any case, this is a point of departure for future studies that should take into account that individual characteristics are relevant to explain the decision to vote or to abstain and that, contradicting Franklin et al. (2004) views of which accounts for turnout in elections, scholars should pay attention to how people approach elections as much as to how elections appear to people.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: The Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (https://www.cses.org). CSES MODULE 1 FULL RELEASE (dataset). December 15, 2015 version. doi:10.7804/cses.module1.2015-12-15; The Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (https://www.cses.org). CSES MODULE 2 FULL RELEASE (dataset). December 15, 2015 version. doi:10.7804/cses.module2.2015-12-15; The Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (https://www.cses.org). CSES MODULE 3 FULL RELEASE (dataset). December 15, 2015 version. doi:10.7804/cses.module3.2015-12-15; The Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (https://www.cses.org). CSES MODULE 4 FULL RELEASE (dataset and documentation). May 29, 2018 version. doi:10.7804/cses.module4.2018-05-29.

Author Contributions

RN conceptualized the research, conducted the analysis, and drafted and reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

The publication of this article was funded by the Ministry of Science, Research and Arts of Baden-Württemberg and the University of Mannheim.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The handling editor declared a past co‐authorship with the author.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Constantin Schäfer for his initial insights and feedback. I also thank the participants of the Conference on “Elections, Parties, and Public Opinion in a Volatile World: A Comparative Perspective” that took place on November 10, 2017 in Mannheim for their useful comments.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2021.719180/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1Individuals who did not locate any party on the ideological scale were not included in the main analyses. These individuals who, according to Navarrete (2020), can be considered as “completely alienated from or indifferent to the electoral menu” were given the highest score of incongruence and were included in replication analyses. These robustness checks did not show significant differences.

2Other variables related to individual characteristics were not included in the analysis because they are not available in all the modules of the CSES. As an example, questions on household income were only included in the module 2 of the CSES.

3The values of polarization indicate the spread of parties along the left–right scale following the formula presented in Dalton (2008). To know more details, see the codebook of the data on polarization in the documentation of the dataset retrieved from https://cses.org/data-download/download-data-documentation/party-system-polarization-index-for-cses-modules-1-4/ (Dalton, 2018).

4Check Table A1 in the Supplementary Appendix to see the details of the countries, years, and the number of cases included in the analysis.

References

Adams, J., Dow, J., and Merrill, S. (2006). The Political Consequences of Alienation-Based and Indifference-Based Voter Abstention: Applications to Presidential Elections. Polit. Behav. 28 (1), 65–86. doi:10.1007/s11109-005-9002-1

Anderson, C. J. (2000). “Economic Voting and Political Context: A Comparative Perspective,” in Electoral Studies. doi:10.1016/s0261-3794(99)00045-1

Anduiza, E. (2002). Individual Characteristics, Institutional Incentives and Electoral Abstention in Western Europe. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 41, 643–673. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.00025

Arceneaux, K. (2003). The Conditional Impact of Blame Attribution on the Relationship between Economic Adversity and Turnout. Polit. Res. Q. 56 (1). doi:10.2307/3219885

Blais, A. (2007). “Turnout in Elections,” in The Oxford Handbook of Political Behaviour. Editors J-D Russell, and H-D Klingemann (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 621–635. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199270125.003.0033

Blais, A. (2006). What Affects Voter Turnout?. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 9, 111–125. doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.9.070204.105121

Bosco, A., and Verney, S. (2012). Electoral Epidemic: The Political Cost of Economic Crisis in Southern Europe, 2010-11. South Eur. Soc. Polit. 17, 129–154. doi:10.1080/13608746.2012.747272

Brambor, T., Clark, W. R., and Golder, M. (2006). Understanding Interaction Models: Improving Empirical Analyses. Polit. Anal. 14 (1), 63–82. doi:10.1093/pan/mpi014

Burden, B. C., and Amber, W. (2014). Economic Discontent as a Mobilizer: Unemployment and Voter Turnout. J. Polit. 76 (4). doi:10.1017/s0022381614000437

Cancela, J., and Geys, B. (2016). Explaining Voter Turnout: A Meta-Analysis of National and Subnational Elections. Elect. Stud. 42, 264–275. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2016.03.005

Dalton, R. J. (2008). The Quantity and the Quality of Party Systems. Comp. Polit. Stud. 41 (7), 899–920. doi:10.1177/0010414008315860

Dassonneville, R., and Çakır, S. (2021). “Party System Polarization and Electoral Behavior,” in Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.1979

Frank, R. W., and Martínezi Coma, F. (2021). Correlates of Voter Turnout. Political Behavior. doi:10.1007/s11109-021-09720-y

Franklin, M. N., van der Eijk, C., Evans, D., Fotos, M., de Mino, W. H., Marsh, M., et al. (2004). Voter Turnout and the Dynamics of Electoral Competition in Established Democracies since 1945. New York: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511616884

Franklin, M. (2004). Voter Turnout and the Dynamics of Electoral Competition in Established Democracies since 1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gallego, A., Rico, G., and Anduiza, E. (2012). Disproportionality and Voter Turnout in New and Old Democracies. Elect. Stud. 31 (1), 159–169. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2011.10.004

Gallagher, M. (2019). Election indices dataset. http://www.tcd.ie/Political_Science/people/michael_gallagher/ElSystems/index.php

Gelman, A., and Hill, J. (2006). Cambridge Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel/Hierarchical Models.

Karp, J. A., and Banducci, S. A. (2007). Party Mobilization and Political Participation in New and Old Democracies. Party Polit. 13 (2), 217–234. doi:10.1177/1354068807073874

Kriesi, H. (2012). The Political Consequences of the Financial and Economic Crisis in Europe: Electoral Punishment and Popular Protest. Swiss Polit. Sci. Rev. 18 (4), 518–522. doi:10.1111/spsr.12006

Lachat, R., and Teperoglou, E. (2021). “Institutional and Party Systems Effects,” in Consequences of Context. How the Social, Political and Economic Environment Affects Voting. Editors H Schmitt, P Segatti, and C van der Eijk (London & New York: ECPR Press), 89–109.

Lefkofridi, Z., Giger, N., and Gallego, A. (2014). Electoral Participation in Pursuit of Policy Representation: Ideological Congruence and Voter Turnout. J. Elections, Public Opin. Parties 24 (3), 291–311. doi:10.1080/17457289.2013.846347

Lewis-Beck, M. S., and Stegmaier., M. (2000). Economic Determinants of Electoral Outcomes. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 3 (1), 183–219. doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.3.1.183

Lupu, N. (2015). Party Polarization and Mass Partisanship: A Comparative Perspective. Polit. Behav. 37, 331–356. doi:10.1007/s11109-014-9279-z

Marinova, D. M., and Anduiza, E. (2020). When Bad News Is Good News: Information Acquisition in Times of Economic Crisis. Polit. Behav. 42, 465–486. doi:10.1007/s11109-018-9503-3

Navarrete, R. M. (2021). Go the Distance: Left-Right Orientations, Partisanship and the Vote. Eur. Polit. Soc. 22 (3), 451–469. doi:10.1080/23745118.2020.1801191

Navarrete, R. M. (2020). Ideological Proximity and Voter Turnout in Multi-Level Systems: Evidence from Spain. J. Elections, Public Opin. Parties 30 (3), 297–316. doi:10.1080/17457289.2020.1727485

Önnudóttir, S., Eva, H., and Magalhães, P. C. (2021). “The State of the Economy before the Election,” in Consequences of Context. How the Social, Political and Economic Environment Affects Voting. Editors H Schmitt, P Segatti, and C van der Eijk (London & New York: ECPR Press), 133–150.

Parvin, P. (2018). Democracy without Participation: A New Politics for a Disengaged Era. Res. Publica 24, 31–52. doi:10.1007/s11158-017-9382-1

Passarelli, G., and Tuorto, D. (2014). Not with My Vote: Turnout and the Economic Crisis in Italy. Contemp. Ital. Polit. 6 (2). doi:10.1080/23248823.2014.924232

Plotke, D. (1997). Representation Is Democracy. Constellations 4 (1), 19–34. doi:10.1111/1467-8675.00033

Rosenstone, S. J. (1982). Economic Adversity and Voter Turnout. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 26 (1), 1. doi:10.2307/2110837

Sartori, G. (1968). “Representational Systems.,” in International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, 470–475.

Schäfer, C., and Debus, M. (2018). No Participation without Representation. J. Eur. Public Pol. 25 (12), 1835–1854. doi:10.1080/13501763.2017.1363806

Schmitt, H., Segatti, P., and van der Eijk, C. (2021). “The Point of Departure: Microlevel Models of Electoral Behaviour,” in Consequences of Context. How the Social, Political and Economic Environment Affects Voting. Editors H Schmitt, P Segatti, and C van der Eijk (London & New York: ECPR Press), 45–59.

Smets, K., and van Ham, C. (2013). The Embarrassment of Riches? A Meta-Analysis of Individual-Level Research on Voter Turnout. Elect. Stud. 32 (2), 344–359. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2012.12.006

Keywords: electoral participation, economic crisis, congruence, representation, ideological proximity, turnout, economic vote

Citation: Navarrete RM (2021) From Economic Crisis to a Crisis of Representation? The Relationship Among Economic Conditions, Ideological Congruence, and Electoral Participation. Front. Polit. Sci. 3:719180. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.719180

Received: 02 June 2021; Accepted: 17 August 2021;

Published: 25 October 2021.

Edited by:

Ignacio Jurado, Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, SpainReviewed by:

Guillermo Cordero, Autonomous University of Madrid, SpainGuadalupe Martínez Fuentes, Universidad de Granada, Spain

Piotr Zagórski, University of Social Sciences and Humanities, Poland

Copyright © 2021 Navarrete. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rosa M. Navarrete, rosa.navarrete@mzes.uni-mannheim.de

Rosa M. Navarrete

Rosa M. Navarrete