- Faculty of Philosophy III, Martin Luther University of Halle-Wittenberg, Halle, Germany

The study analyzes the beginning of the Albanian student movement of December 1990 from a historical–sociological and comparative perspective. This historical interpretation of various sources (newspaper articles, activists’ memoirs, interviews, and archival documents) draws its theoretical arguments from social movement studies, student activism, and the sociology of higher education. The study offers a complex explanation of the role of the movement during the country’s democratic transition by also looking at similar cases. Considerations of the broader international and local implications, the role of the university, the academic staff, and the student organization all are accounted for. After tracing the repertoires of strategies and content of the movement to the Albanian Cultural Revolution of the 1960s, the study argues that student activism benefitted from the structural opportunities provided by changes introduced in higher education during the historical sequence of late Socialism.

1 Introduction

In 2018, a small student demonstration evolved into a massive protest that threatened the survival of the recently elected government. The movement had been fomented since 2014 when a group of students and professors rose against the new law on higher education.1 The December 2018 protest was reminiscent of the December 1990 student revolution that overthrew the totalitarian regime that had ruled the country since 1945. The circumstances were remarkably similar. The main locus of both protests was the University of Tirana, the outbursts were driven by economic grievances, and students demanded a change in political leadership.

The protesters of 2018 acknowledged the legacy of December 1990. However, a large banner displayed on the façade of the Polytechnical University of Tirana alluded to the corruption of the 1990s movement2. By referring to a popular conspiracy theory3, the banner also articulated the general mistrust of the country’s political elite, while the same fear of cooptation drove the protesting students of December 2018 to reject any logistic support offered by the largest opposition parties. The most persistent and articulated was the left-wing student and professor activists, Levizja per Universitetin4 (The Movement for the University, backed by Organizata Politike, see Qorri 2018; Erebara 2018). After 2 months, the student movement subsided and succumbed to the usual patron clientelist mechanisms of Albanian politics.5

The rejection to cooperate with the opposition was a strategic choice that could be explained by previous contentious events, transnational borrowing, and the political context of the Albanian political system. First, activists feared the appropriation of their cause by politicians, who they thought were seeking to exploit the momentum as they had previously done since 1992. Their reluctance to ally with the political opposition, the allegations of government cooptation, and rejection of any political pact6 that would dictate the outcome might have originated from the normative and rather utopian perception borrowed from the democratization movement that assumes a clear distinction between civil and political society7. Second, the obvious unwillingness to enter a sort of “ignominious alliance” with the political class reflected the student activists’ sentiments towards political compromise. Third, by rejecting the support of the political elite in 2018, activists sought to construct a distinct narrative for their movement, in contrast to the dominant discourse surrounding the legacy of the December 1990 movement, especially for the legitimacy of the country’s post-communist intellectual and political elite. The activists also questioned the idea that the legacy of the previous successful democratization movement carried the same mobilizing potential for future protests. Similar to the Chilean student movement of 2011 (see Bellei et al., 2014, p. 436; Brooks 2016, p. 5), the movement signals both a generational change and a crisis of political legitimacy. 8

The above discussion on the most recent student movement illustrates the importance of historical thinking for the activists. In their analysis of the legacy and the strategic choices of the December 1990 movement, Albanian researchers also show similar patterns of understanding (Halili 2016; Rama 2020a). Although they agree that the student movement was pivotal in the country’s transition to democracy in 1991, they claim that the movement was tainted by the alleged involvement of regime collaborators. Based on the memories of activists, who regard the beginnings of the movement as unsullied,9 these accounts are imbued with various instances of ethical historicism. They do not take into account the structural settings.

On the other hand, comparative macro-structural studies on democratic transitions assume that the political elite controlled the regime change in Albania from its outset (Merkel 1999), or in alliance with the activists (Rossi and Della Porta, 2017). This view diminishes the role of the December 1990 movement. Moreover, comparative analyses (e.g., Della Porta 2014; Rossi and Della Porta, 2015) are framed in what Mark et al. (2019, p. 6) label historical frameworks of Western-led globalization, which are teleological and rely “implicitly on frameworks derived from a very Western-centric version of global history.”

To account for both the structural settings and the global historical perspective, this study attempts to present a more complex historical narrative of the Albanian student movement of December 1990. The study aims to explain the occurrence of the key event of the movement at the State University of Tirana. It examines the role of the university environment on the movement and the possible structural changes in that environment that affected the movement’s strategic choices and its repertoire of contention. While higher education and the university are perceived as global institutions, the comparisons of similar cases, like those of Czechoslovakia and China, provide for a comparative outlook.

The three overlapping themes of inquiry in this case study are student activism (e.g., Altbach 2007), social movement research (e.g., Rossi 2015), and sociology of higher education (e.g., Meyer et al., 2007). The empirical and theoretical arguments deployed here examine the impact of the university on the emergence of the movement and the movement’s strategic actions. The narrative explanation comprises both contentious and non-contentious events at macro-structural, institutional, and interactional levels. The movement is traced back to the critical juncture of the Albanian Culture Revolution of the 1960s and the structural changes of the university environment that occurred during the historical sequence of late socialism in the 1980s. Historical research methods are applied for the collection, assessment, interpretation, and presentation of evidence.

The next section presents a qualitative systematic literature review. The third section delineates the analytical framework and the research design, followed by the case study in Section 4 and discussions in Section 5.

2 Literature Review

2.1 The Historical Context From a Comparative Perspective

From 1945 to 1991, Albania was ruled by the Party of Labor of Albania (PPSH), and its charismatic and authoritarian leaders, Enver Hoxha (1945–1985) and Ramiz Alia (1985–1991). In the theoretical regime typology of Merkel (1999, p. 51), the regime was classified as a communist-totalitarian regime. Similar to the Soviet Union during Stalin (Jowitt, 1983, p. 278), Albania was a party state governed by a “charismatic political, social, and economic organization undergoing routinization in a neotraditional direction.” The patrimonial Albanian state adapted the previous social order and consisted of informal patronage networks (Hensell 2004; Meksi 2016), combining elements from the Weberian charismatic authority model. In part, the legitimacy of the ruling PPSH was derived from the charisma of its authoritarian ruler Hoxha. The country’s alliances with Yugoslavia (1945–1947), the Soviet Union (1948–1961), and China (1961–1978) during the Cold War guaranteed that the political system performed and ensured the survival of the regime (Biberaj 1986; Grothusen 1993).

By the end of the 1980s, economic stagnation and major geopolitical shifts in Eastern Europe—i.e., the contagious Third Wave of Democratization (Merkel 1999; Leeson and Dean 2009)—disoriented the political leadership, encouraged reformists, and enabled policy entrepreneurs who accelerated the collapse of the regime in 1991. The leadership sought a peaceful and controlled transition from fear of a violent outcome, like in Romania, and initiated political changes. Unsatisfied with the pace, individuals tried to organize massive protests in January 1990 and small outbursts occurred in several districts. The involvement of foreign actors (Alia 2010; Abrahams 2015) further animated the reformists within the elite and dissidents to take subversive actions. The pressure grew as thousands stormed Western embassies in July 1990 seeking political asylum. A group of intellectuals met with the president in August 1990. Rumors circulated that a student movement was expected in September after the summer break. Weeks before the student movement, the regime indicated its willingness to grant political concessions by initiating constitutional amendments10. These critical events11 boosted the student’s confidence and professors at the University of Tirana in December 1990 to mobilize and buck any threat of violence.

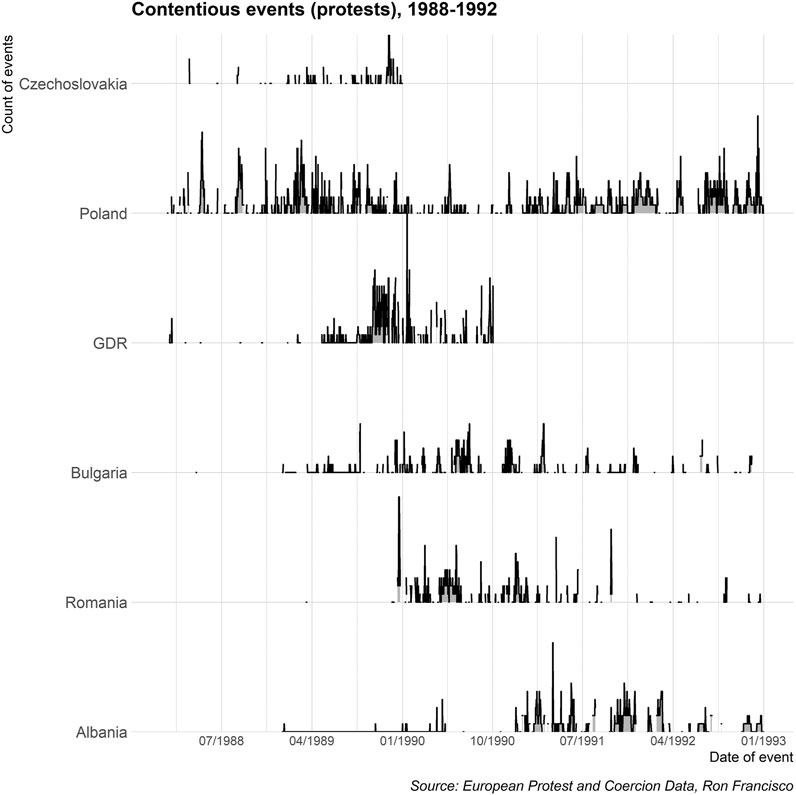

Comparatively, Albania, Romania, and Bulgaria are clustered in the same group regarding the type of regime change (Merkel 1999, p. 135), patterns of protest cycles, and social composition. The system transformation is classified as democratization controlled and guided from above (see Schmidt-Neke 1993, p. 80; Merkel 1999, p. 135; Della Porta, 2014), while mass mobilization occurred later than in Poland, the German Democratic Republic, and Czechoslovakia (see Figure 1). Assuming a strong association between democratic transition and the existence of civil society, Chiodi (2012) and Della Porta (2014) attribute the lag to the missing civil society.

FIGURE 1. Visualization of protest cycles 1988–1989 in Eastern Europe showing the lag and the low intensity of protests in Romania and Albania before 1990, in comparison to other countries.

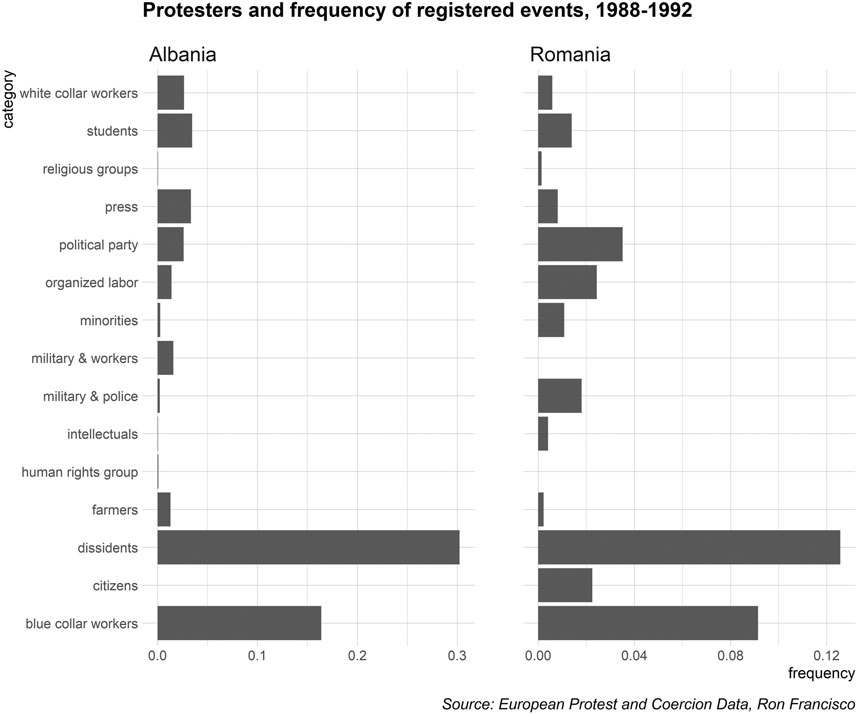

Considering the social composition of the movement, the major groups were the students and the intellectuals. These groups fall under the category of urban middle classes, who together with industrial workers are assumed conducive to democratization because of their motivation and capacities (Dahlum et al., 2019). Because students demanded deep structural changes that aimed at replacing the totalitarian regime, rather than moderate political interventions or cultural changes, the December 1990 movement is classified as a structural revolutionary movement (typology of Gill and DeFronzo 2009). From 1988 to 1992, besides Albania and Czechoslovakia, the NAVCO dataset on non-violent campaigns identifies six other similar but non-European movements originating from students (Chenoweth and Orion, 2019, data processed by; Dahlum et al., 2019). Contentious events in the same period in Albania and Romania were dominated by blue-collar workers and dissidents (see Figure 2).

FIGURE 2. Frequency of registered actions and their agents from 1988 to 1992, showing the similarities between Albania and Romania12.

Other comparable cases are the University of Pristina in Former-Yugoslavia 1981 (see Halili 2020; Hetemi 2020) and the Velvet Revolution in Czechoslovakia (see Wheaton and Kavan 2018). For example, the December 8, 1990 student protest in Albania resembled the Black Friday of the Velvet Revolution (violent suppression of a student demonstration, establishment of a civic forum, etc.). Della Porta et al. (2018) labels both contentious events as eventful protests; events that mobilized a considerable number of people and resources and affected the strategic choices of the involved parties. Conspiracies of equivalent scenarios about the role of the Soviet Union and compromise exist in Tirana, Pristina, and Prague.

The significance of the December 1990 movement cannot be inferred from the above macro-structural and comparative perspectives. These approaches cannot be used to explain singular cases (see Kitschelt 2003, p. 53). They cannot explain why the regime yielded to the demands of one group at a crucial moment and a university environment. Zooming in on the institutional and interactional level from a historical perspective helps to identify the movement as a key moment of a historical constellation (Kitschelt 2003, p. 54)—a culmination of a historical alliance of the students and the intelligentsia.

2.2 On the Albanian Student Movement

Numerous accounts have been presented by former student activists (Krasniqi 1998; Shehu and Haxhia 2016; Rama 2020b), researchers (Halili 2016; 2020), and scholar-activists (Rama 2006; Rama 2020a). Until recently, Albanian researchers and activists have been occupied with what organizational research labels as legacy or legitimacy narratives (Landau et al., 2014). These narratives highlight the impact of the student movement on the regime transition and acknowledge it as a source of political legitimacy13. A regime of memory around the movement has been constructed to produce and nurture subjectivities, legitimize political aspirations, and justify entitlements.

International scholars (Vickers and Pettifer 1997) and journalists (Abrahams 2015; Biberaj 2019) have embedded their narratives in the transition paradigm14 (Carothers, 2002). The movement is teleologically conceptualized as the starting point of the democratization period and as a socialization instance for the creation of the present elite. Chiodi (2012), whose working paper for the Center on Social Movement Studies on Albanian civil society is the basis for the case analysis presented by Della Porta (2014, p. 237), is set in the same democratization and transition paradigm. The literature on student activism has largely ignored the case (Karklins and Petersen 1993; Altbach 2007; Luescher-Mamashela 2015).

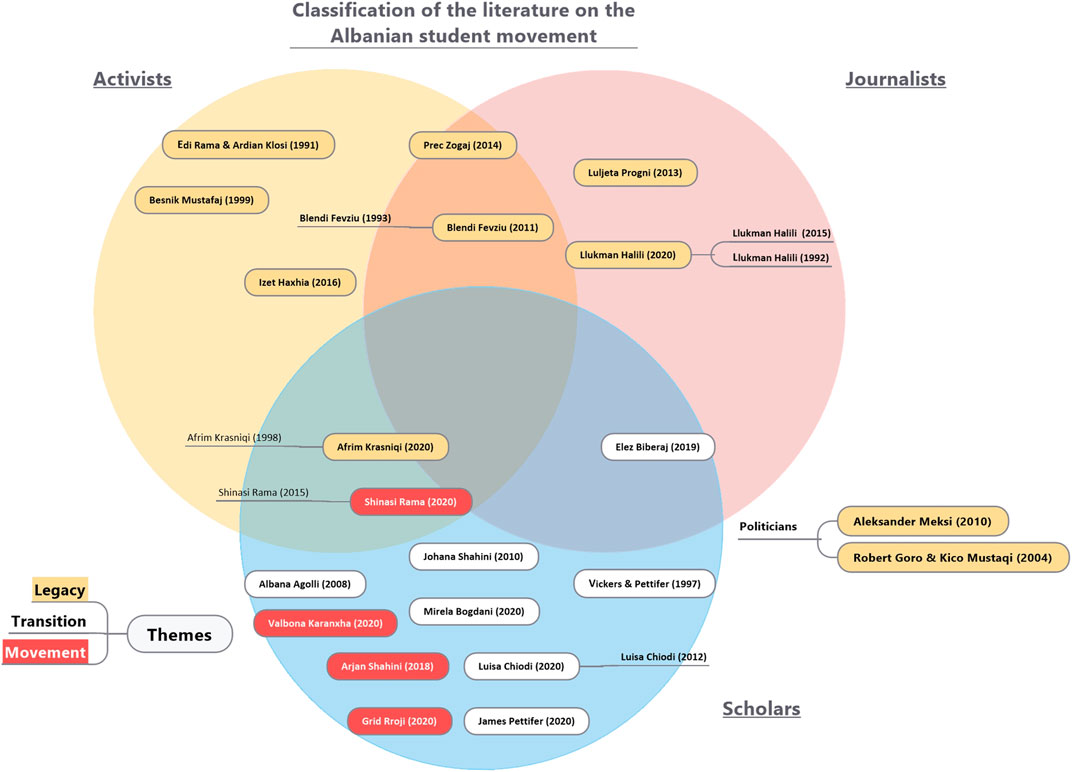

Figure 3 classifies the literature according to the main themes and the role of the narrator. The three most prevalent themes in the literature concern the legacy (14 sources) and the transition or democratization paradigm (11). Most narrators are researchers (14 sources) and journalists (5), and the rest are activists, politicians, or a combination. Research reports and memoirs make the bulk of the documents produced on the events, and only one is a collection of documents15.

FIGURE 3. Classification of literature on Albanian Student Movement (themes and role of the narrator).

Few studies examine the internal dynamics of the movement from the perspective of the social movement or organizational theory. Such are the theory-driven micro-historical studies on the organizational environment (Shahini 2020), the internal dynamics of the movement (Rama 2020a; Rroji 2020), and the role of leadership (Karanxha 2020). Rroji (2020) investigates the role of nationalism as a source of mobilization and identity formation for the Albanian student movement16. Rama (2020a, 2020b). emphasizes the role of the students as the main social force behind the movement and provides a comprehensive review, although entrapped in the same legacy narrative.

To conclude, institutional explanations and the historical perspective on the repertoire of strategies are lacking. Most of the sources are based on the oral accounts of activists in different roles throughout their careers. Both the legacy and the transition literature are embedded in consequentialist, teleological, or normative explanatory frameworks.

3 Theory Frame and Research Design

The analytical device guiding the narration is a focused theory frame (Rueschemeyer 2009). The frame allows the flexible use of weak concepts and assumptions from historical sociology that have been adapted to the historical narration and understanding of this event. The focus is on the institutional and interactional level of analysis. The analytical concepts were drawn from the research streams of student activism and social movement studies. The historical inquiry concentrates on the impact of the university environment on the movement and the possible structural changes in that environment that affected the movement’s strategic choices.

Although the analysis goes beyond macrostructural explanations, like the democratization movement in Eastern Europe, the economic difficulties, the guided transition, etc., it takes them as assumptions (e.g., the Third Wave of democratization and controlled transition). To examine the immediate circumstances of the movement, such as the role of the university environment and the structural changes, the analysis transitions to the institutional level and interactional level. The propositions are inferred from the scholarship on student activism. The focus is on the strategic choices of activists. The analytical framework exploits Rossi’s (2015) concepts of repertoire of strategies and stock of legacies.

At the institutional level, research on student activism in the West indicates that a university environment is conducive to student movements (Altbach 1964; Brown 1967; Keniston 1967; Cornell 1968; Sasajima et al., 1968; Scott and El-Assal 1969; Meyer and Rubinson 1972; Pugh et al., 1972; Altbach 2007; Luescher-Mamashela 2015). Universities are usually located in urban and cultural centers. Students at large-size universities are more likely to find like-minded peers to join a group, and the collective experience of student life strengthens the loyalty toward the group. Universities attract an academically oriented student body that is perceptive to its intellectual environment, in which the academic staff plays a significant role (Altbach 1964; Pugh et al., 1972; Altbach 2007). Faculty members may resist the regime’s interventions (Connelly 2000; Tsvetkova 2013) or encourage dissent both through their teaching and research activities (Altbach 2007, p. 330). Young academics are expected to be more tolerant and supportive of student activism than older, conservative faculty members (Pugh et al., 1972). Furthermore, the curriculum of the academic program, e.g., social sciences, is more likely to radicalize students as they become aware of social problems (Altbach 1964; Keniston 1967; Altbach 2007). The environment and the educational values it transmits encourage independent thinking among students who then may question the established social and political institutions (Altbach 2007, p. 330). Universities are more liberal towards students’ personal and political lives. Institutional legacy and images of previous engagement in political activism may contribute to future activism. Finally, formal student organizations are not expected to engage with the movement, especially when political activities antagonize authorities (Luescher-Mamashela 2015, p. 35). These aspects of the university environment at the institutional level (e.g., size, diversity of the student body, the education and intellectual environment, the organizational culture, and the role of university authorities) are understood as explanatory variables for student activism. They interact with the changes in the organizational structure of the university and those at the macro-level.

The structural changes that occurred at the beginning of the 1980s in higher education are conceived of as a consequence of changes in political opportunity structures17. At the macrostructural level, political opportunity “encompasses the relative openness of the system, the formal and informal set of power relations among potential allies, and the degree of state repression” (Travaglino 2014, p. 4). Changes in the opportunities and threats on those that challenge the system affect the character of the contention, the strategies, or the activities of the movements (Tilly and Tarrow 2015, p. 59). These changes occur when (1) power is dispersed, (2) the system welcomes newcomers, (3) political alignments and constellations are unstable, (4) influential allies or those who support the challengers are available, and (5) the regime tries to repress or facilitate dissent. Changes at the macrostructural level spilled over to higher education institutions, student activism, and the power relations between university authorities, faculty, official student organizations, and student activists. The economic stagnation and the increasing confusion of the regime stimulated dissidence and intensified activism.

At the interactional level, the collective action and the strategic choices of the movement are traced back to past events of student activism (Rossi 2015; Della Porta et al., 2018). Charles Tilly’s concept of the repertoire of contention (contentious public events, e.g., roadblocks, marches, and protests) is supplemented here by Rossi’s (2015, p. 21) repertoire of strategies, which broadens the analysis to include both contentious and non-contentious events. Repertoire strategies are a “historically constrained set of available options for non-teleological strategic action in public, semi public, or private arenas” (Rossi 2015, p. 22). The strategies entail a series of tactical decisions of the movement in response to short-term political changes and are strongly linked with the repertoire of contention. For instance, the alliance with one ideologically affiliated group affects the choice of the repertoire of contention. Relevant here is the multi-sectoral strategy. This represents the idea that “to achieve the desired political goals, it is crucial to join efforts with diverse segments of society and/or political groupings” (Rossi 2015, p. 25). Furthermore, the selection and perception of the actor on the feasibility and availability of strategies are constrained by what Rossi (2015) labels stock of legacies: “the concatenation of past struggles” as they are perceived, experienced, and internalized by the actors. A similar approach is proposed by Della Porta et al. (2018) to examine the legacy of previous movements and the impact of critical junctures in history regarding regime transitions.

The concepts listed above are integrated into the frame of the historical sociology of event analysis (Abbott, 1992; Mahoney 2000). Its basic premise is that social reality is a “matter of particular social actors, in particular social places, at particular social times” that “happens in sequences of actions located within constraining or enabling structures” (Abbott, 1992, p. 428). This frame focuses on structural changes. It assumes that historical sequences events are path-dependent (Sewell 1990, p. 24) when “contingent events set into motion institutional patterns or event chains that have deterministic properties” (Mahoney 2000, p. 507).

The study identifies the structural changes at the institutional level (e.g., higher education and university), the small changes, and intervening steps (Mahoney 2000, p. 530) that amounted to the main outcome event, the movement. The movement is causally linked with the contingent event of the Albanian cultural revolution (henceforth, cultural revolution), the historical sequence of late Socialism, and the consequential structural changes that occurred in the university environment. First, the analysis assumes that the geopolitical events confused the leadership (Tarrow 1991, p. 16 labels it a period of political disorder) and created a cleavage between the PPSH and the intellectual elite, between faculty members, the party organization, and its youth organization. These cleavages were exploited by activists. Second, the cultural revolution is the initial event, the unpredictable turning point, which as shown later in the analysis, triggered a different chain of events. The historical sequence of late Socialism (Idrizi 2018) represents the sufficient and necessary conditions for the transformation of power relations within the elite, which caused the reversal of the early events of the cultural revolution.

This is a single case study (see also Bosi and Reiter 2014 on the methodology) and narrative explanation, which is based on archival documents and oral accounts. The oral accounts were extracted from a published corpus of unstructured interviews conducted by Progni 2013, interviews printed in the media or broadcasted on television, and published memoirs (Krasniqi 1998; Alia 2010; Rama 2012; Zogaj 2014). Other primary sources were collected from the Albanian State Archive18, the funds of the Ministry of Education and Culture, the administrative district of Tirana, the Ministry of Internal Affairs (declassified reports of the secret police, Directorate I), and transcripts in published works (e.g., Meksi 2010). Data collection and analysis tools consist of archival research, qualitative and quantitative corpus text analysis, and descriptive time series analysis.

4 Narrative Explanation

This section presents the events and examines the conditions, the repertoires of contention, and the strategies of the movement.

4.1 The Events

4.1.1 December 1990

On December 4th, frequent power shortages and poor living conditions drove about 300 students living on the campus of the University of Tirana to the street. Accustomed to government-scripted marches (manifestations) against the war in Vietnam or similar sanctioned gatherings, the protest surprised regime defenders. On December 6th, student representatives of the communist youth organization at the Faculty of Engineering posted a big-character poster criticizing the old guard of the Party’s Politburo (the old jackets) and the living conditions at the student quartier (Krasniqi 1998). They demanded an audience with the prime minister. On December 8th, after an unsatisfactory meeting with Prime Minister Carcani A, students at the Higher Institute of Arts organized a music event to commemorate the death of John Lennon. Under the influence of two popular professors, Rama E and Imami A, the meeting turned into a political gathering (Klosi and Rama 1991). At midnight of the 9th, aware of the political nature of their demand, students launched a demonstration. A steering committee and a group of representatives were elected to negotiate with the government and demanded an audience with President Alia R, also the PPSH leader. The audience did not clear the confusion (Alia 2010).

Another meeting with Alia on December 11th followed where students were more vocal but still hesitant (e.g., the discussion stuck on the issue of whether freedom of association was stipulated in the constitution). The activists seemed unprepared to lead a political movement. On the same day, two university professors, Berisha S and Pashko G joined the movement. Once they were involved, the demands were crystallized, despite creating factions in the movement (Rama 2006). Within 4 days, students and professors helped raise a popular revolt, which at first was met with violence. The regime withdrew once more students joined the movement. Some 6,000 students signed a petition demanding political pluralism and freedom of association19. Two student associations sprung out of the movement and competed for leadership. The recently founded Democratic Party of Albania, led by Berisha, succeeded in controlling the movement and represented both students and professors20. After the first democratic elections and due to continuing strikes, the university was temporarily shut down in March 1991.

4.1.2 The Albanian Cultural Revolution

The cultural revolution, the revolutionization movement, was a top-down initiated and controlled adaption of the Chinese Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution. From the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s, it mobilized the youth and the education system (Pano 1974; Marku 2017a). Differing in degree, the movement resembles the Romanian “cultural mini-revolution” of 1971 (see here Stanciu 2013, p. 1065). Both cases of policy transfer were largely influenced by China; the Romanian case also by the Soviet Union and Poland.

In Albania, the revolutionary agenda targeted the bureaucracy, the religion, and sought to curtail foreign influences by attacking the Catholic church and the legacy of the Sovietization period (1948–1961). It restricted access to Western culture and alienated the Western-educated intelligentsia, including those educated in the Soviet Union. For example, the number of outgoing students declined from nearly 1,000 students in 1961 before the Soviet-Albanian split, to less than five in 1968. At the dawn of the Chinese Cultural Revolution, the numbers increased, although mostly with China (at a total of about 290 students till 1978, Jiafu 2012), as four to five students annually were sent to France, Romania, and Italy. After losing its initial impetus because of the campaignist style (see Van Atta 1989) of similar half-hearted government reforms, the cultural revolution was actively challenged by members of the intellectual elite. Contrary to the Soviet model they had adopted enthusiastically (Mëhilli 2018), they resented the Chinese modernization model (Marku 2017b) that was euphemistically labeled the revolutionization movement.

A short relaxation period ensued by the beginning of the 1970s (Pano 1974, p. 55) to gain the support of the youth (Alia 2010), which reformists counting on the Chinese support sought to exploit. An inter-elite conflict ensued that generated a new wave of repression and purges lasting from 1973 to 197521. Similar conflicts involving the cultural intelligentsia, the managerial, and the revolutionary elites, were observed in Eastern Europe (Bakeret al., 2007). In Albania, the conflict was also perturbed by the decline in China’s financial commitments after its rapprochement with the United States. As in East Germany (Miethe 2006) and Czechoslovakia (Wheaton and Kavan 2018), the regime became disappointed with its youth and the Communist cultural intelligentsia.

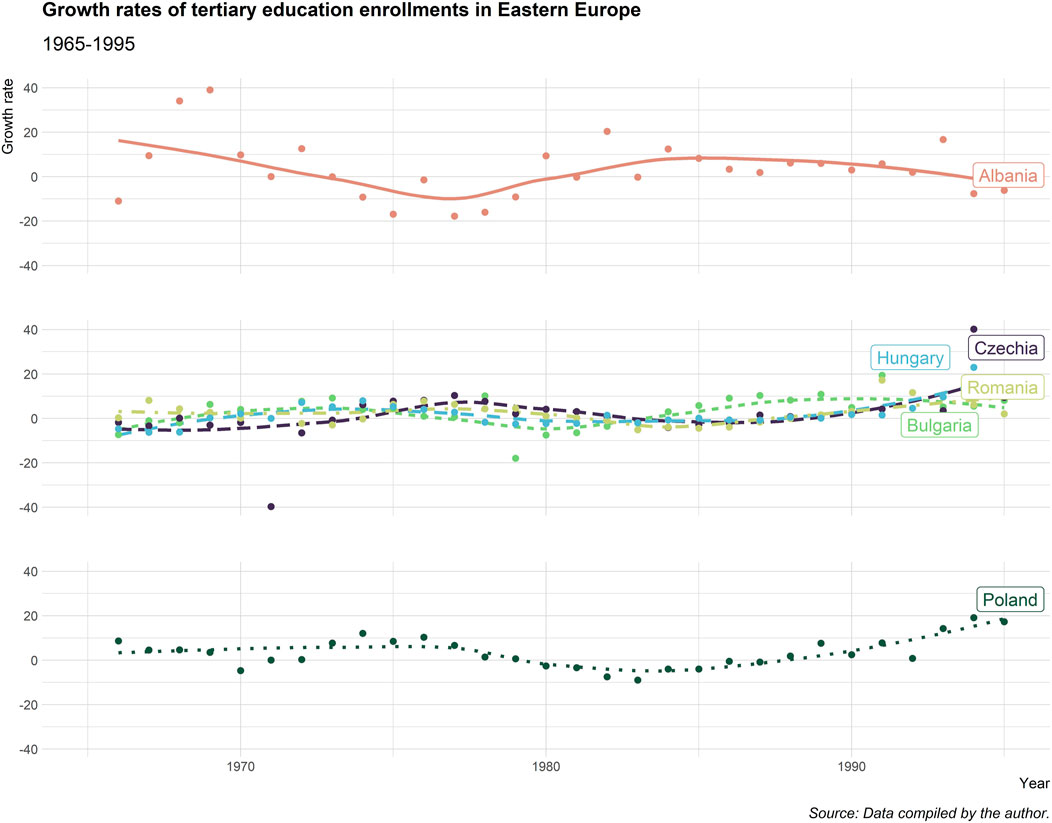

The anti-Soviet agenda of the cultural revolution affected the curriculum, textbooks, personnel, and student life, but did not target the rigid hierarchical management system of the Soviet higher education model22 adapted in 1947 with the help of Yugoslavia, and later the Soviet Union (Kambo 2014). The interventions strengthened the role of the party through its parallel structures; the professional bodies (Bashkimet Profesionale) and student organizations. In the course of the revolutionization, several academic programs were vocationalized (e.g., pharmacy), the nationalistic and indoctrinary components23 of the curriculum grew up to 50% in some subjects, and the number of translated textbooks was reduced.24 About 10%–15% of the academic personnel were purged, relocated, or rotated (i.e., sent to work in farms or industrial sites), and student life became increasingly disciplined. Although similar to other Eastern European countries (Cornell 1968), access to higher education had been restricted, and based on political and social merit, the admission criteria became much more exclusory. Like other Eastern European countries (Reisz and Stock 2006, see Figure 4), Albanian higher education was contracted due to the same inter-elite conflict (Bakeret al., 2007). In the mid-1970s, the staff was reduced by 15%, and enrollments dropped by 25.5% (e.g., from about 28,600 in 1973 to 21,200 in 1976).

FIGURE 4. Growth rates of tertiary education enrollments in Eastern Europe, 1965–1995.25.

4.2 Institutional Level

The repertoire of strategies and contention was influenced by the participation of students, professors, party members, and administrators in past struggles that had occurred at the State University of Tirana. Established in 1957 in Tirana with the help of the Soviet Union, the important political institution may be classified as a state-building university (Ordorika and Pusser 2007). After the break with the Soviet (1961) and during the Sino-Albanian alliance (1962–1978), the university was and remains the largest and the most important institution for the education and employment of the country’s political and cultural elite. Its nation-building role was expanded once the regime drifted toward nationalism in the 1970s (Tönnes, 1980). The institution hosted a vast patronage network of personnel with links to the country’s political leadership. The high degree of professionalization in the course of scientization (Drori et al., 2003) and the patronage networks had made it de facto independent from direct government control. Moreover, the university remained at its core a World Institution: claiming “an intimate tie to a universal and global or cosmopolitan knowledge system” (Meyer et al., 2007, p. 195). Acknowledging the indispensable role of the university in its modernization plans (on the scientific-technical revolution see Hoppe 1993), the regime tried to exert its influence through the party and its youth organization. Since the cultural revolution, they had played a greater role in academic and administrative affairs.

4.2.1 Structural Changes During Late Socialism

By the end of the 1970s, with the beginning of the historical sequence of late Socialism, the regime and the intelligentsia began to reverse the effects of the cultural revolution. The suicide of the former Prime Minister Shehu M in 1981, the policy entrepreneur behind the transfer of the cultural revolution and the main representative of the revolutionary elite, accelerated the process. A period of relaxation began (Idrizi 2018) and the sporadic waves of the anti-intellectual campaigns abated. For example, the number of imprisoned university graduates was reduced by half (from about 700 in 1976–1980 to about 350 in 1981–1985)26.

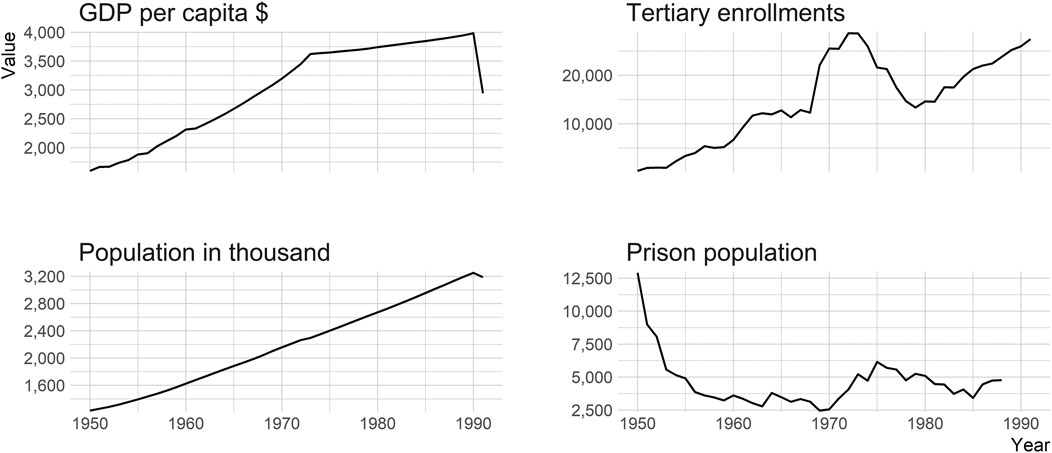

The expansion of higher education rebounded (see Figure 4 and Figure 5). By 1990, there were about 26,000 students, approaching the highest record in enrollments since 1973 (28,000). The number of academic personnel also rose after a sharp decline in 1976, from about 1,000 to almost 1,800 in 1991.28 The University of Tirana enrolled circa 13,500 students and was close to reaching its second-highest point in history (about 14,000 students in 1974). As the economy was stagnating (Pashko 1991, see Figure 5: GDP per capita), experts warned about the expansion29. However, the lack of infrastructure and financial resources did not convince the government to contain the growth. Increased demand and lack of employment prospects drove enrollment beyond government projections30 Moreover, hooliganism and similar manifestations of disruptive behavior overwhelmed the management31. The penal doctrine treated such conduct as hostile, but legal and policing practices suggest that by the end of the 1980s, deviation and criminality among the working-class youth was tolerated as legal repression subsided, mostly due to efforts to restore socialist legality (Shahini 2021).

FIGURE 5. Time series of the GDP, higher education enrollment, population, and prison population 1950–1991.27.

Less restrictive admission policies brought about changes in the student body, which previously reflected the radical affirmative action favoring the working class, and the better-educated students from the South or Tirana. For example, the proportion of new enrollments from white-collar families grew from 35% in 1977, to almost 60% in 1987 and 67% in 198832. Instead of favoring the working class, the admission criteria in the 1980s were aligned with the regional development strategy, aiming to increase access for students from Northern Albania33. The propaganda discourse on the class struggle diminished and admission restrictions were relaxed for those categorized as politically and ideologically unfit; usually, they were assigned to engineering or agriculture courses. For instance, one student activist at the Agricultural University of Tirana, Zaloshnja E, managed to gain admission after several rejections34. Clientelist transactions circumvented admission criteria, despite poor academic skills or flaws in political merit35.

Elements of the curriculum that had been introduced during the cultural revolution were reversed. The 1-year compulsory internship in production before admission to the university was canceled in 1981. The length of study in some programs was extended, reversing the previous interventions, which prioritized technical and short-time education. By early 1990, the required course of Marxism-Leninism was canceled, the curriculum load in military training was reduced, and several directives pushed for the borrowing of modern didactical approaches36. For example, the XI Party Congress had declared “a direct and total war against mechanical and passive learning” (Korrespondenti Studenti, 1988, p. 1).

The constitution of the academic personnel also changed. The percentage of lecturers younger than 40 years was more than 50%, that of 30 years old grew from 15% in 1979 to 22% in 1984, while the percentage of white-collar workers increased slightly, reaching almost 50% (Misja et al., 1986, p. 129). By the end of the 1980s, as a professor recalls, the elections in the professional bodies of the faculty brought new people in, not necessarily regime loyalists, although the party structures within the university remained intact (Progni 2013, p. 344). A new generation of personnel replaced the old Soviet-trained specialists silenced by the cultural revolution as the number of postgraduates and doctoral degree holders increased. Until 1991, almost 70% of academic titles and nearly 76% of postgraduate theses were conferred from 1981 to 1991. 37 A form of group consciousness emerged among the new members, who then managed to organize into an independent association during the movement (Meksi 2010)38. As members of the socialist intelligentsia, they had the same academic background from the University of Tirana, followed the party norms and the institution’s governing principles of the cultural revolution, and were deemed regime loyal (Lleshi and Starova 2017). Comparative accounts conceptualize the socialist intelligentsia on the verge of regime transition as transitional elite (see Mark et al., 2019). By 1983, as there was a more positive attitude toward the socialist intelligentsia, the regime lowered its guard and the state security unit responsible for the surveillance of the intelligentsia ceased to exist, making it difficult for the security operatives to monitor members of the intelligentsia or coerce collaboration39.

Furthermore, the relative opening of the country’s borders enabled selected faculty members to study abroad and foment links to the international epistemic networks. In the 1980s, the relationship with the West started to improve and exchanges in the education sector were intensified. This, according to the then Minister of Education, Mrs. Cami T, was recommended by Hoxha E, who had summoned her in private40. The cooperation agreements with France and Italy were expanded and the university benefitted from the technical assistance of international organizations to train its staff (e.g., the 1983 program for the transfer of information technology, UNDP/UNESCO ALB/81/001.) Consequently, by 1985 in France, there were 53 Albanian undergraduate and postgraduate students41; 10 years ago, from 1971 to 1974, there had been about 20. There were plans to send as many postgraduates as possible to the Federal Republic of Germany and France, and more were trained by incoming international experts42. Monitoring students abroad became almost impossible (Kellici, 2020). When the number of postgraduates in France increased to 110 in 1990, the Albanian Embassy in France struggled to guarantee their full cooperation43. Students trying to defect also signaled systemic changes at home.

4.2.2 The Impact on the Movement

The structural changes mentioned had a positive impact on the movement. First, the generational change of the academic personnel and their experience abroad created a critical mass of academic staff that pushed for changes, especially concerning foreign relations and the alliance with the West.

Second, the expansion of higher education brought together many dissatisfied and like-minded students and created social problems that the regime and university authorities were unable to handle. A critical mass of students with the same background and from the same region formed networks of trust, which were essential to the movement. The collective life at the dormitories, the military training, and the long trips home deepened friendships and strengthened network ties among students. Close ties affect recruitment and generate the necessary social capital to support activism, especially as activists appeal to a shared identity (Crossley 2008). Students from the towns of Shkodra and Tropoja, who harbored stronger resentment against the regime (Rama 2006), increased in number due to the affirmative action for Northern Albania (e.g., activists such as Rama Sh, Hajdari A, and Haxhia I, were from the region). They were joined by a few students from former dissident families, who had been rehabilitated. Furthermore, these students were enrolled in engineering disciplines44 since they were high achieving but politically unfit. This explains the difference with Western student activism, where students enrolled in social sciences and humanities have been active (Altbach 1964; Keniston 1967).

Third, as the student quarter grew beyond its capacities45, the living conditions worsened, as did the morale of the administration. For example, only one-third of students used the cafeteria, while in 1981 there were more than two-thirds.46 As students prepared their meals in the dorm, the power grid was steadily overloaded causing frequent power shortages, which was the triggering event of the student movement on December 8th. Due to the conditions, trust in the authorities eroded and their disciplinary capacities were diminished. For instance, when the administration of the student quarter tried to discourage student activists by imposing a curfew, they were met with resistance (Krasniqi 1998). As cases of disruptive behavior at the compound increased, management and police forces had trouble differentiating political dissidence from social deviance. For example, when intelligence services reported on two key female activists, they were categorized as psychologically unstable or morally depraved47.

4.3 Interactional Level

The repertoire of contention and strategies of the movement is traced to the cultural revolution lasting from the late 1960s to the mid-1970s; the critical juncture that influenced the subsequent events leading to the choice of the repertoire of strategies and contention of the December 1990 movement.

4.3.1 Repertoires of Contention: The Ghosts of Tsinghua

The initial contentious events betray the legacy of the cultural revolution. The repertoire consisted of (1) the involvement of the formal student organization and their request for an audience with the highest government authority, (2) the use of big-character posters (Albanian: flete-rrufe [striking leaflet]; Chinese: dazibao), and (3) characterization of the political elite as the old guard, signaling their antagonism and framing the problem as a generational issue. Anti-government demonstrations or protests after December 8th were new actions in the repertoire of claim-making performance. Activists recall knowing only about anti-imperialist or anti-capitalist protests (Cipi 2020). The repertoire was expanded after January 1991 (e.g., hunger strikes, sit-ins, and petitions).

First, voicing demands through the student organization was an affirmation of the emancipatory role of the party’s youth organization. The repertoire of claim-making performances used by the organization also suggests that student activists resorted to the available actions that were sanctioned by the regime and recognized as legitimate instruments for the expression of grievances. The political role of the youth organization had been asserted during the critical juncture of the Albanian culture revolution in the 1960s (Paja 2018). Its official organ (The Voice of Youth) and the University of Tirana had been involved in the regime’s anti-religion and anti-intellectual campaigns. From a comparative perspective, the role of the University of Tirana at this point resembled the Tsinghua University in Beijing (see Pan 2006), although the campaigns were less chaotic and strictly controlled by the Albanian Party of Labor (Marku 2017a). The request for an audience with the highest authority, an officially sanctioned form of complaint, indicated the importance of patronage links and the close relationship between the youth organization and the head of state. These audiences were a reminiscence of meetings with former leader Hoxha E, where he spoke at length with minimum interaction. As per tradition, Alia also spoke most of the time in the meeting (about 50% of the interventions, and 58% of the total 15,000 tokens)48.

Second, the big-character poster campaigns were initially organized by the youth organization in coordination with the party during the anti-bureaucracy, anti-intellectual, and anti-Soviet campaigns of the cultural revolution (see Vehbiu 2016). For example, at the university, the posters had targeted members of the old intelligentsia, e.g., the linguist Cabej (2018), and Soviet-trained professors (e.g., Karajani M, or the former university rector Kellici Z)49 who had fallen out of favor during the implementation of the regime’s anti-Soviet agenda.

Third, the reference to the old guard is related to the party’s authorized conflict and acknowledged contradiction between the progressists and the conservatives within the elite during the cultural revolution. The divisive discourse was borrowed from the Chinese cultural revolution, known as the fight against the four olds: ideas, culture, customs, and habits (Jian et al., 2014). The student activist, who drafted the big-character poster, used similar terms to describe his view of PPSH (conservatives) and its leader, Alia R, whom the intelligentsia thought of as belonging to the progressists (Majko P interviewed by Xhevdet, 2014). The big-character poster invoking the old jacket who signified the old guard was fashionably challenged by the reformist elite who paraded in new white Burberry-style trench coats, as Progni (2013) titled her book, though there have been speculations that link the scenario and the wardrobe to the cloakrooms of Western secret services (e.g., Abrahams 2015).50

Finally, it is unclear whether democratization became what Tarrow (1991, p. 15) labels a master frame for the articulation of discontent during the revolts of the 1990s in Eastern Europe. For example, Rroji (2020) suggests that the Albanian student movement was framed and rooted in the nationalist discourse, while protesters chanted pro-European slogans, expressing their discontent for the previous isolation period during and after the Sino-Albanian alliance. In his audience with the activists, President Alia referred to democratization frequently (12 times), but the activists echoed it only once. Although the official framing of the term is again traced back to the cultural revolution, it appears that the slogans of the cultural revolution, e.g., democratization51 (associated with the keyword signifying the Chinese cultural revolution, revolutionization) were revived in the regime’s sanctioned discourse of the late 1980s. In the 1970s, democratization had merely implied support for PPSH through the mobilization of the masses and their organizations (popular democracy and proletarian democracy), although members of the intelligentsia had unsuccessfully sought to manipulate the discourse for greater concessions. However, since 1989, the student journal, Gazeta Studenti, first published at the beginning of the cultural revolution in 1967, retook the slogan and issued a series of editorials on democratization, meaning greater participation of students in the governing bodies of the university, while according to Alia (2010, p. 324), the process had started in 1986. Whether the regime resorted to the same discourse because of international pressure, or because there was a limited choice in the local repertoire of claim-making performance, or because the regime wanted to reassure its clients that it was orchestrating the events behind the scenes, is disputable. Nevertheless, lacking a reference model since the break of the Sino-Albanian alliance in 1978, democratization became a floating signifier.

4.3.2 Repertoire of Strategies: The Disciples

Since the beginning, students ignored the formal student organizations and sought to cooperate with their professors and members of the intelligentsia. At first, they were rebuffed. Either they feared repercussions because the scripted-like actions of the formal student organization did not convey any trust, or they were skeptical of the political awareness of the students. Although some faculty members had silently52 supported the students, intellectuals like Berisha S had demanded reforms and perceived the movement as a decisive device to induce regime change (Berisha 2010). Nevertheless, the alliance between students and faculty members remained single-sectoral in the initial stage; efforts to mobilize workers started after the meeting with Alia53. By comparison, in Czechoslovakia, students coalesced with dissidents and due to the legacy of the Prague Spring 1968 riots, the coalition was multi-sectoral (Wheaton and Kavan 2018, p. 29).

This choice of strategy may be interpreted as a tactical move if speculated that the alliance was imposed by progressists to guide or capture the movement in the grand scheme of regime transition from above. Another interpretation is that intelligentsia intended to seize the leadership and take ownership of the movement (Karanxha 2020; Rama 2020a). These consequentialist interpretations are grounded on an implausible historical sequence about the origin of the movement. The sequence of events indicates the presence of faculty members since the beginning. For example, in August 1990, faculty members (Berisha S and Pashko G) had been in an audience with Alia discussing political pluralism, and others had joined the movement since its inception (e.g., Imami A and Rama E on December 7), while the audience with the president (on December 9) was attended by both students and academic representatives, who perceived the movement as led by intellectuals54. Rumors reported by intelligence services warned that people were expecting a large student protest in September 19, 9055 once the students returned from the summer break, right after Alia’s audience with the intellectuals. The movement did not materialize until 3 months later. Furthermore, two politically ambitious faculty members were positioned earlier on as interlocutors (Berisha 2010). Hence, an alternative explanation considers contingency and attributes agency to both groups. Students and academics jointly took leadership of the movement and developed a spontaneous political agenda that went beyond the projected scenarios.

Whatever the explanation, the alliance was based on the historical premise that, as members of the intelligentsia, faculty members and students enjoyed the confidence of regime reformists. Professors acted as mediators between the regime and the educated strata of the population. Students, who embodied the socialist engineering project of the new socialist man, took advantage of their reputation, high social status as offspring of the administrative elite, and the guarantees of the political elite to gain the support of the population. Other alliances were not feasible at the beginning, e.g., workers or the army were perceived as belonging to the conservatives, as had been the case during the cultural revolution; this was the reference historical moment of the previous inter-elite conflict. Independently of their position in the interaction with the movement, whether as interlocutor, facilitator, or obstructor, the roles were historically determined.

4.4 The Interlocutors

The two main interlocutors turned political entrepreneurs in their own right were Berisha S and Pashko G. As loyal members of the party’s intelligentsia and respected experts, they mediated between students and the regime. Professor Berisha’s case manifests the classic principal-agent problem in agent theory (see Eisenhardt 1989, p. 59), whereby his principals (members of PPSH and President Alia) and he as an agent had conflicting goals and risk preferences. Although it appears that he was a trusted mediator for the regime, as one of his close associates recalls (Shehu and Haxhia 2016), the parties were serving different clients with different expectations about the pace and the quality of the planned changes, not excluding the involvement of foreign actors and Berisha’s self-serving attitude. Berisha used his position and the information asymmetry he gained to confuse the political leadership while undermining the effectiveness of the regime’s interventions and trying to shape students’ demands. The principal-agent theory is a rational explanation of the role Berisha played in the movement, but interpretations vary from a regime pawn to a malleable adversary, or a hero by chance (Halili, 2020). Nevertheless, the engagement of these two university professors resulted in the establishment of the first opposition party, which then sought to control the student movement (Rama 2020a).

The strategy of the reformists and the intelligentsia concerning the role of the interlocutor emulated the play of a similar set of mediators during the contingent event of the cultural revolution. At the beginning of the 1970s, when the regime relaxed repression to gain the support of the youth, it was the university rector Mero A who mediated between the authoritarian ruler, Hoxha, and the country’s youth. Mero had been the head of the national youth organization during the anti-religious campaign and was responsible for youth mobilization. Acting as a policy entrepreneur, Mero, a PPSH cadet like Berisha S, had misinterpreted or tried to manipulate the political agenda (see the interview in Veliu 2005). Circumstantial evidence suggests that Mero belonged to a group of intellectuals who had approved of Hoxha’s decision to part from the Soviet sphere of influence. They sought to manipulate the leader into moving from the communist block altogether while seeking to ally with him against Shehu M, the most conservative member of the revolutionary elite56. A protégé of Hoxha and another party leader57, Mero, exemplified the new generation of the intelligentsia that had earned the trust of the party and was possibly groomed as a future leader58. Addressing the country’s youth in 1970 through Mero, the authoritarian leader was probably misquoted or misapprehended, which led to the misconception of the informal directives as a move toward liberalization (see interviews of Lubonja F in Fevziu 2008; Mero in Veliu 2005). The rector, whose fate resembles that of Chi Qun (Tsinghua University) during the Chinese cultural revolution, was demoted and expelled from PPSH during the purges.

In analogy to the December 1990 movement, as an interlocutor, Berisha carried some of the virtues Mero A was known for (i.e., intelligence, reliability, and assiduousness). Although Berisha’s relationship with Alia, besides his regional affiliation, remains unclear, their association may be explained by the country’s paternalistic mechanisms and Alia’s reliance on the technocrats (Alia 2010, p. 319). The most enthusiastic activists were from the North, as were President Alia and Berisha, a fact that induced trust among the two and that Alia (2010, p. 360) was keen to bring in conversation (Fevziu 2011, p. 53). Mero was from the South (Gjirokastra, the same town as his patron Hoxha E). In alliance with Alia, Berisha successfully saw confusion amidst the political leadership, while helping activists to articulate their demands in political terms. Just like Mero A in the 1970s with Hoxha E, Berisha tended to modify the content of the messages and overstep the authority delegated by the principal parties, President Alia primarily.

President Alia, the successor of the authoritarian ruler Hoxha since 1985, was perceived by both students and the intelligentsia as a reformist. A former education minister in the 1950s, he had been heavily involved in education policy and propaganda matters. His closest associates were Hoxha’s wife, another important player in the party’s education and propaganda sector, and a group of experts educated in the Soviet Union (e.g., Beqja H and Lazri S). According to Beqja (2016) and archival evidence,59 Alia had played a moderating role during the cultural revolution, especially concerning the university, where his wife was teaching. Alia (2010, p. 258) was against radical solutions advocated by the other two influential leaders, H Kapo and M Shehu. The latter had been the policy entrepreneur behind the agenda of transferring the Chinese cultural revolution to the Albanian education system60 and was hostile to Alia (Alia, 2010, p. 265). Alia’s attitude and interventions to mitigate the effects of the cultural revolution and his commitment to the country’s socialist scientific-technical revolution might have contributed to his reputation as a progressist. During the audience, activists sought to leverage these sentiments by calling Alia a “pioneer of democracy,” which he was quick to reject as flattery (Meksi 2010, p. 63). Professors who had stood behind the scenes in the initial stage of the movement dared to join after Alia confirmed his reformist position.

4.5 Facilitators and Obstructors

Faculty members mobilized and radicalized students by helping them frame their demands and instilling a sense of political competence and efficacy. Framing provides the “action-oriented set of beliefs and meanings that inspire and legitimate the activities and campaigns of a social movement organization” (Benford and Snow 2000, p. 614), while engaging students politically meant influencing their political awareness and how they were defined symbolically and structurally in the political system (see Meyer and Rubinson 1972).

Both parties confirm that students were initially politically aloof (Progni 2013, pp. 351). Some were defensive of the regime when provoked (Selami E in Progni 2013, p. 355). Lecturers had to be explicit in their dissent, and inventive in how they approached students. For example, a professor at the Institute of Arts was direct at encouraging students to reject the establishment (Progni 2013, p. 300), while at the Institute of Agriculture, where students were more apathetic and confused, faculty members carefully stepped forward and helped them align their demands with those of the students at the University of Tirana (Progni 2013, p. 394). Some used their established rapports to mobilize students and influence their personalities, whereby the most influential were those who lived at the campus with their families (Progni 2013, p. 196) and who had studied abroad. Western university graduates were more open and supportive (e.g., Ruli G, Pashko G, Selami E, Berisha S, Ceka N, and Klosi A). For example, a student, Shano D (Progni 2013, p. 239), recalls that Pashko G, one of the young faculty leaders of the movement, was “like their spiritual leader” and he would take his students for “peripatetic strolls” in the park (referring to Aristoteles), where he discussed the recent turmoil in Eastern Europe and the country’s economy. Another student, Care E, remembers that when the overall atmosphere in December 1990 was confusing, internationally experienced professors were forthcoming to discuss current issues in their teaching sessions (Progni 2013, p. 218). As their primary allies, professors helped students with their political orientation and injected them with a sense of achievement to contribute to the political transformation of the country.

Nevertheless, initially, not all university personnel were supportive, if not actively sabotaging the movement. While some rejected the invitation to lead the students in their second day of revolts, others demanded that students abandon the strike and return to the lecture halls or degraded them in faculty meetings (Progni 2013, p. 196–218; Krasniqi 1998). For example, members of the Faculty of Philosophy and Sociology and the Faculty of Political Sciences and Law, affiliated with PPSH and its ruling elite, were the most unsupportive61.

Activists refused to cooperate with the formal student organization because of its political role and the informal and formal links with the ruling elite, although the triggering event of the movement was the big-character poster of the youth organization at the Faculty of Mechanical Engineering and Textile. For example, students regarded the content of the big-character poster as apolitical and were suspicious of the involvement of Majko P, the secretary of the youth organization; he was a relative of the head secretary at the faculty (Cara E in Progni 2013, p. 293). Student and youth organizations (Bashkimi i Rinise se Punes se Shqiperise, BRPSH) whose members were compelled to monitor and discipline student behavior were perceived as the long arm of PPSH. They organized cultural and political events, oversaw students’ academic progress and their participation in research groups and associations, intervened in academic activities, and monitored lectures, and Krasniqi (1998) maintains that they even influenced academic assessments. However, according to the correspondents of the student gazette, the activities were formal, monotonous, colorless (Barjaba 1988, p. 2), and barely attracted any attention (Baze, 1988). Though they represented students’ interests (Korrespondenti Studentit 1988, p. 2), activists ignored them. When President Alia recommended the activists to cooperate with the youth organization, Hajdari A, one of the leaders, replied that the organization was “a conveyer belt,” implying that it was controlled remotely (Meksi 2010, p. 56). The head of the communist youth organization, Bashkurti L, was booed when he tried to talk them out of the protests (Krasniqi 1998, p. 43). An activist alleges that the same official even offered rewards (money and traveling) to some of their leaders, but students did not yield (Fevziu 2011, p. 200). Bashkurti denies the allegation and refused to comment62.

Otherwise, members of the student council at the student quartier tried to hamper activists (Krasniqi 1998). The biweekly student newspaper of the youth organization at the University of Tirana and the gazette of the youth organization ignored the movement. The latter resumed publication later in December 1990. It condemned “the acts of vandalism, banditry, and terrorism of the dark forces”63 and announced that the youth organization (BRPSH) was running in the coming elections as a political organization. To conclude, student activists and policy entrepreneurs exploited the opportunity to create alternative organizations because formal student organizations lacked legitimacy. Both student and faculty activists established formal organizations: the Commission of the Student Movement and the Autonomous Democratic Organization of Students and Young Intellectuals64.

The third possible ally in the matrix is the secret police. Its role fits in the narrative of the transition from above, especially considering the role of President Alia as a progressist. Whether the vector of the movement was manipulated accordingly remains inconclusive. The documentary evidence at this point is scarce and the narrative builds on the premise that either the alleged conspirators were informants, or they were controlled by PPSH, which also operated as an intelligence service. Besides one confirmed case, allegations of student and faculty activists cooperating with the secret service as informants or agent provocateurs are based on rumors. Data to this point are still elusive. For instance, there are unsubstantiated claims that two leading student activists were informants65. The truth is muddled by the political motives of the accusers and the erroneous conspirative assumption that by deploying a set of tactics one may achieve a predictable outcome. Nevertheless, even if the two leading activists were planted, then they exceeded their mandate or were converted to the movement and became double agents (on the term see Marx 1974, p. 416).

5 Discussions

The study explained the choice of strategies and actions of activists at the beginning of the Albanian student movement on the verge of the system transformation in 1990. The choice was constrained by past struggles and experiences within the structural settings of the university. The experiences were traced back to two turning points in the history of the regime, the cultural revolution of the 1960s and the structural changes that occurred in the country’s higher education during the historical sequence of late Socialism in the 1980s. First, the study showed the importance of institutional factors, the university environment, which was perceived here as a national and global institution (Meyer et al., 2007), and a place of contention between the intelligentsia and the Party of Labor of Albania. Second, it described how the role of the university on student activism differed between these two events due to the structural differences at all analytical levels.

The arguments of student activism, social movement studies, and the sociology of higher education were drawn to provide a narrative explanation of the December 1990 movement that is embedded in a broader historical context than previous research (Halili, 2016; Rama 2020a; Rroji 2020; della Porta 2015). The analysis presented a complex explanation that is time–space specific and non-teleological (see Rossi 2015). It first indicates the benefits of including institutional explanations and non-contentious events in the analysis of pro-democracy social movements and instances of regime change. Secondly, going beyond the legitimacy narrative and the transition paradigm discussed in the systematic literature review on the Albanian pro-democracy movement, the analysis serves as a proof of concept for the treatment of other similar cases.

This contextual and historical sensitive narration on Albania’s democratic transition adds more puzzle pieces and layers to the parsimonious and generic explanation provided at the macrostructural level. The assemblage fits in the larger picture presented by two major theses on the regime transition in Albania, the controlled democratization from above and the cooperation of regime reformists with activists. From a comparative perspective, the case confirms the effects of similar structural constraints across the same type of communist regimes in Eastern Europe (Kitschelt 2003), both on regime change and the strategies of social movements. Future research may attach the case to Mark et al. (2019) global history research agenda of Eastern Europe (e.g., looking at the role of the “transitional elite”, understood as part of the global networks and international institutions.)

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the author, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

AS contributed to the design and implementation of the research, to the analysis of the results, and to the writing of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Prof. Dr. Sonja Grimm and two reviewers for their helpful comments on the first drafts.

Footnotes

1Law no. 80/2015, on 22.7.2015, “On higher education and research at the higher education institutions in the Republic of Albania.”

2The banner, prepared by students of the Faculty of Economy, stated “LONG LIVE THE FREE YOUTH—THE END OF KATOVICA. - WE DECIDE TODAY.” Jani Marka, activist, Personal Communication. July 1, 2019.

3Katovica, Poland, is where allegedly leaders of Eastern European communist governments agreed to temporarily hand over their power after appointing puppets in key positions.

4Albanian alphabet characters ç and ë are simplified in this paper to c and e.

5Rather than increasing funding, reducing tuition fees, and improving the quality of teaching, the government introduced populist initiatives (e.g., a more generous scholarship program), threatened the academic staff with selective ethical persecution (e.g., by reviewing the process of academic promotion for possible corruption and plagiarism), and subjugated the management.

6The government’s programmatic slogan to respond to the protest was the Pact for the University (Pakti per Universitetin); a similar policy proposal to the German Hochschulpakt 2020.

7It could not be defined as a separate sphere neither during the one-party state that controlled social activities through mass mobilization (women’s organization, youth organization, professional organizations, etc.), nor in a capitalist society (see Kocka, 2004).

8The protests resembled those of Chile 2011. The left-wing student organization attacked the reform agenda as neoliberal and borrowed from the Chilean higher education reform.

9See Halili (2020), quoting a student activist: “I say with conviction that the 1990 student revolution is the most massive, the purest, the least flawed, the most sincere, and the most successful movement in all the history of Albania.”

10Kuvendi Popullor [Parliament.] Decree No. 196 (13 November, 1990) [For the establishment of the special commission for the amendment of the Constitution of the People’s Socialist Republic of Albania].

11A group of intellectuals close to the Party of Labor of Albania published open letters discussing the role of the intellectuals (e.g., Sali Berisha, Ylli Popa); the National Theater performed a critical piece from Budina E, with a screenplay from the well-known writer Kadare I, who then defected to France, etc.

12To simplify the visualization, some of the categories from the original dataset have been collapsed into larger categories.

13The organizational myth of the Democratic Party of Albania resides on the legacy of the student movement.

14The normative analysis views the democratic transition as transitioning through a sequence of stages from opening, breakthrough, and to the triumph of the demographic forces during the consolidation and the functioning of democratic institutions.

15Out of 29 works identified here, about 11 were memoires by activists and politicians.

16Hetemi’s (2020) argument on the student movement in Kosovo runs similar to Rroji (2020) regarding the role of ethnicity. Hetemi examines the interventions of the Albanian government as an opportunistic political entrepreneur in the Kosovar movement. On the tide of nationalism and nationalist mobilization engulfing the Eastern European countries, see Beissinger (2002).

17Two main theoretical perspectives explain the emergence and the development of social movement according to Travaglino (2014, p. 4): (1) Resource Mobilization approach, which focuses on the micro-structural processes and the social movement organizations; and (2) the Political Opportunities approach, which stresses the importance of opportunities provided by the political context.

18Archival documents are cited as: AQSH (Arkivi Qendror Shtetror/Central State Archive), F. 511 (e.g., Ministry of Education and Culture), V (Year), D (Folder), Fl (Page number) [Document title]. Missing information is n.a.

19See the original document: “Requests presented by students in the great rally at the Student Quartier”, December 10, 1990 in (Meksi, 2010, p. 11).

20Of the about 350 initial members of the Democratic Party of Albania, 40% were students, 8% were university professors, and the rest were other white-collar workers.

21The head of the State Planning Commission and the minister of industry were accused of economic sabotage and sentenced to death. Former ministers of foreign trade, education, and the head of the public television were imprisoned. The ministers of agriculture, education, and the rector of the State University of Tirana were dismissed and demoted.

22The characteristics were “[a] rigid hierarchical nature, integration into a unique regulatory system shaped by the parallel structures of the party-state, an urge toward extreme centralization, a sharp distinction between research and teaching, and interpenetration of political and professional cultures” (David-Fox and Péteri, 2006, p. 5).

23Designed in 1968, the policy agenda borrowed from the Chinese education model a modified version of the early Stalinist radical model (Hayhoe 2004). The reform was signed into law in 1969. It required “the organic unity of learning, manufacturing activity, and physical, and military education” [Law No. 4624, 24 December 1969 (On the New Education System)].

24For example, it is estimated that the portion of translated university textbooks to the total produced declined from 30% during 1960–1970 to less than 10% in 1970–1980. Data scraped from the online database of the National Library of Albania, site: https://www.bksh.al (September 2019).

25Data compiled from UNESCO - Institute for Statistics (2021) database and archival research.

26AQSH, F.14-APOU, V.1989, D.9, Fl.19 [Higher Court to Central Committee of the Party, 22 February, 1989].

27Sources: (1) GDP per capita, Maddison Project Database (2020); (2) Tertiary enrollments, archival sources from the Ministry of Education and Culture (1950–1991); (3) Population, Maddison Project Database (2020); (4) Prison population, see AQSH, F.14-APOU, V.1989, D.9, Fl.19. Document title: Gjykata e Larte derguar Komitetit Qendror te PPSH, dt. 22.02.1989 [Higher Court to Central Committee of the Party, 22.02.1989]. Data have been disaggregated with R package, tempdisagg (Sax and Steiner, 2013).

28AQSH, F.511, D.152, V.1990. Fl. n.a. [Study of Ministry of Education for the structure and organization of education in the Socialist Republic of Albania: Prepared for international organizations, 9 September, 1990].

29AQSH. F.511, D.101, V.1986. Fl. n.a. [Fifth year plan on the development of higher education 1986–1990, 16 December, 1983].

30From the projected 20,600 for 1990, enrollments had already jumped to 25,200 by 1988. AQSH, F.495, D.246, V.1988. Fl.n.a. [Statistical register processed by SPC apparatus on student enrollment in kindergarten, 8-year schools of primary and upper secondary, and higher education for the academic year 1988–1989, December 1988].

31Reports on unruly conduct at the compound became more frequent by the late 1980s. For instance, in 1989, such case involved a relatively large number of male and female students. MPB (Ministria e Puneve te Brendshme/Ministry of Internal Affairs), F.4, D.256, V.1989. Fl.2 [On an event at the student quartier. 21 March, 1989].

32The peasantry is not included in the later official statistics. In 1977, there were 30% from blue-collar families, 35% white-collar, 22% peasantry, and 12% a mix of blue- and white-collar. In 1988, there were 23% blue-collar, 67% white-collar, and 10% mix. Data are compiled from different sources.

33Since the mid-1970s, there is an increasing concern about the unequal development of the regions, an interest one may also attribute to the patronage network of Ramiz Alia who was from the North (Shkodra). See, for instance, a report on the special quota granted to students from Northern Albania: AQSH, F.511, V.1989, D.88, Fl.1 [Ministry of Education and Culture to Central Committee of PPSH, 26 October, 1989].

34Such decision engendered conflicts among different administrative bodies. In this particular case, the highest local party organizations approved of his admission in 1981, while the lowest local administrative unit rejected; the district executive committee gave the final approval. AQSH. Arkiva Shteterore Vendore - Tirane [Local State Archive of Tirana., ASHV-Tirane] Komiteti Ekzekutiv i Keshillit Popullor i Lagjes Nr. 1 - Tirane, V.1981, D.76, Fl. 9 [Meeting Protocol, 27 June, 1981].

35For example, in 1987, the admission quota for the district of Tirana changed several times and at least five students had personal recommendations from members of the Politburo. AQSH. ASHV-Tirane. Komiteti Ekzekutiv i Keshillit Populor te Rrethit Tirane. V.1987. D. 2. Fl. n.a. [Report on the distribution of study places of higher education. 4 August, 1987].

36AQSH, F.511, V.1990, D.83, Fl.n.a. [Embassy Paris to Ministry of Education. On the moral-political state and educating efforts with students and postgraduates in France.” On 12 March, 1990].

37Among other sources (see Tarifa 1992), the theses dataset was scraped from the online database of the National Library of Albania.

38Organizata e intelektualeve te rinj.

39Luan Pobrati. Former intelligence officer of the Ministry of Interior. November-October 2017, Personal Communication.

40T. Cami, Personal Communication, July 13, 2016.

41AQSH, F.511, V.1985, D.161, Fl.n.a. [Embassy Paris to Tirana, Ministry of Foreign Affairs: Report on the system and accommodation of students and postgraduates for the academic year 1985–1986. On 16 December, 1985].

42AQSH, F.511, V.1990, D.141, Fl.n.a. [Council of Ministers to Ministry of Education. Decree: For long-term post-graduate studies, and qualification and experience gathering abroad for the year 1990. On 4 August, 1989].

43AQSH, F.511, V.1990, D.83, Fl.n.a. [Embassy Paris to Ministry of Education. On the moral-political state and educating efforts with students and postgraduates in France. On 12 March, 1990].

44MPB, F.4, D.651, V.1990, Fl. 8–10. [On some other details on the students’ rally, 11 December 1990]. The majority of the 700 student strikers that demanded the removal of the name of Enver Hoxha from the University of Tirana in 1991 were enrolled in sciences.