95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci. , 06 August 2021

Sec. Political Participation

Volume 3 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2021.692396

This article is part of the Research Topic Voting from Abroad View all 8 articles

The COVID-19 pandemic has made it clear that the traditional “booth, ballot, and pen” model of voting, based on a specific location and physical presence, may not be feasible during a health crisis. This situation has highlighted the need to assess whether existing national electoral legislation includes enough instruments to ensure citizens’ safety during voting procedures, even under the conditions of a global pandemic. Such instruments, often grouped under the umbrella of voter facilitation or convenience voting, range from voting in advance and various forms of absentee voting (postal, online, and proxy voting) to assisted voting and voting at home and in hospitals and other healthcare institutions. While most democracies have implemented at least some form of voter facilitation, substantial cross-country differences still exist. In the push to develop pandemic-sustainable elections in different institutional and political contexts, variation in voter facilitation makes it possible to learn from country-specific experiences. As accessibility and inclusiveness are critical components of elections for ensuring political legitimacy and accountability these lessons are of utmost importance.

In this study, we focus on Finland, where the Parliament decided in March 2021 to postpone for two months the municipal elections that were originally scheduled to be held on April 18. Although the decision was mostly justified by the sudden and dramatic daily increase in new COVID-19 infections, the inability to guarantee the opportunity to vote for those in quarantine was included among the likely risks. The failure to organize health-safe voting procedures to accommodate the original schedule emphasizes a certain paradox in the Finnish electoral legislation: caution in introducing new facilitation instruments has led to lower levels of preparedness and flexibility in crisis situations. Although a forerunner in implementing extensive advance voting opportunities, Finland has only recently introduced postal voting, which is restricted to voters living abroad. Hence, we ask: what can be learned from this form of convenience voting if expanded to all voters to enhance the sustainability of elections?

Our analyses are based on a survey conducted among non-resident voters (n = 2,100) after the 2019 parliamentary elections in which postal voting from abroad was allowed for the first time. Our results show that whereas trust in the integrity of postal voting is quite high, various efforts needed from individual voters substantially increase the costs of postal voting. Postal operations also raise concerns. Furthermore, voters felt that requiring two witnesses made postal voting cumbersome, an issue that needs to be resolved, particularly if applying postal voting in the context of a pandemic. The Finnish case constitutes a concrete example of a situation in which voter facilitation targeted to a particular segment of society may become a testbed for electoral engineering that will improve voting opportunities for everyone.

The COVID-19 pandemic has tested the sustainability of liberal democracy and its core institutions. As legitimacy and accountability are particularly important during a crisis when many ordinary channels for civic participation are temporarily limited by emergency conditions, the role of elections becomes essential. At the same time, the global pandemic has made it increasingly difficult to run safe elections by relying on the traditional “booth, ballot, and pen” model, which emphasizes location and physical presence. Since the outbreak of the virus, at least 78 countries postponed national or subnational elections scheduled between February 21, 2020 and March 14, 2021 (International IDEA, 2021). Turnout has not declined worldwide in elections held according to their original schedule, but preliminary findings point toward an association between the severity of the health situation (the number of infections and deaths) and a lower participation rate (Santana et al., 2020).

The challenges posed by on-site voting highlights the need for alternative ways to cast a ballot (Fernandez Gibaja, 2020; Gronke et al., 2020). Theoretically, pandemic sustainability should be higher in countries that have introduced a wide range of voter facilitation instruments. These instruments, often grouped under the umbrella of convenience voting, range from voting in advance and various forms of absentee voting (postal, online, and proxy voting) to assisted voting and voting at home and in hospitals and other healthcare institutions. While most democracies have implemented at least some form of voter facilitation, substantial cross-country differences exist (see e.g., Wass et al., 2017). Depending on their electoral legislation, countries had various toolkits of voter facilitation instruments at their disposal in the beginning of the pandemic. Such variations in the convenience voting repertoire, as well as institutional opportunities or constraints for introducing new electoral legislation in response to the pandemic, may help us to understand the emerging dilemma: why have some countries been able to run elections safely, simultaneously ensuring inclusiveness and accessibility, while others have suffered from a dramatic drop in turnout or have had to postpone elections altogether? Country-specific experiences provide invaluable lessons on developing pandemic-sustainable elections in different institutional and political contexts.

In this study, we focus on Finland, which is among the few European countries that recently opted not to run municipal elections on their originally scheduled date of April 18, 2021. In early March, the committee of party secretaries recommended to postpone the elections to June 13 and extend the period for advance voting from seven to fourteen days. The government made a proposition to Parliament accordingly, approved in late March. While the need to postpone the elections was mostly justified by the sudden and dramatic daily increase in new infections, the inability to guarantee those in quarantine the opportunity to vote was identified as one of the problems with the voting process (Oikeusministeriö, 2021). This shortcoming reflects a relatively modest use of voter facilitation instruments. A forerunner in implementing extensive advance voting opportunities, Finland has only recently introduced postal voting to elections, which is restricted to voters living abroad. In fall 2020, the parliamentary committee preparing electoral reforms and the Ministry of Justice, which is the national electoral authority, ruled against expanding postal voting to include domestic voters for the pandemic toolkit of Finnish elections (Oikeusministeriö, 2021). Instead, they chose more technical solutions, such as outdoor and drive-in voting. The failure to organize health-safe elections to accommodate the original schedule emphasizes a paradox in the Finnish electoral legislation: caution in introducing new facilitation instruments has led to lower levels of preparedness and flexibility in crisis situations.

The decision to postpone elections, supported by all parliamentary parties except the Finns Party, made it clear that a wider electoral reform is warranted to improve the sustainability of elections in future crizes, including pandemics. In its report on postponing the elections, the Constitutional Committee urged the government to explore options for applying postal voting in corresponding situations in the future (Valiokunnan mietintö, 2021). For that purpose, experiences from the 2019 parliamentary elections offer particularly useful insights: what works, what should be developed further, and what requires re-evaluation. We explored these issues using a survey conducted among non-resident voters (n = 2,100) after the 2019 parliamentary elections in which postal voting from abroad was enabled for the first time. Our results show that whereas trust in the integrity of postal voting is quite high, various efforts needed from individual voters substantially increased the costs of postal voting. Postal operations also raised concerns. Furthermore, voters felt that requiring two witnesses made postal voting cumbersome, an issue that needs to be resolved, particularly if applying postal voting in the context of a pandemic. The Finnish case constitutes a concrete example of a situation in which voter facilitation targeted to a particular segment of society may become a testbed for electoral engineering (see Norris, 2004) that will improve voting opportunities for everyone.

Voter facilitation is an important component in institutional-level voting arrangements that can either enhance or hinder participation (Wass et al., 2017, 506). Any election reform or amendment to electoral legislation, such as introducing a new form of convenience voting, usually entails a complex policy process like the one described in Figure 1 (see James and Garnett, 2020, 121–122). The process may start with some actors pointing out a particular state of affairs, for instance, low turnout among young people or non-resident citizens. Whether that is perceived as a grievance or otherwise undesired outcome reflects broader values, such as equality and inclusion, and those values often form a key justification for pursuing legal reforms. Politicians, the government, key ministries, or the electoral authorities themselves can act to initiate the process, but the initiative can also come from other actors, such as special interest groups or non-government organizations (NGOs).

If the initiative is taken up by other strategically important actors and progresses to the stage of legislative preparation, a wide range of policy considerations and assessments will also be involved. How might the reform affect the activities of both voters and parties? Does it disproportionately favor some parties at the expense of others? What effect does this have on the political status quo? Not only are questions like this difficult to assess, but the answers to them can vary considerably, depending on the perspective of each actor. Electoral reforms are usually prepared in a committee composed of party secretaries to ensure their legitimacy and to give the reforms a realistic chance of being accepted in Parliament. At the same time, the inclusion of key stakeholders (e.g., parties, experts, special interest groups, civil society representatives) makes the negotiations cumbersome, as consideration of the common good at the level of political systems intervenes with party-specific tactical calculations. It may also be the case that several features of the system are being reformed simultaneously and their potential interactions become difficult to estimate.

When the reform is finally implemented, its empirically perceived effects are weighed against both the original objective and stakeholders’ expectations and preferences. The results, in turn, influence the prospects of any subsequent reform projects. Impact assessment is often hampered by the lack of a genuine benchmark, making it difficult to distinguish direct consequences of a reform from indirect consequences or synergies with other factors. This can be seen in contradictory empirical findings. For instance, postal voting has proven to be either a nearly ineffective instrument in terms of turnout (see e.g., Giammo and Brox, 2010; Gronke and Miller, 2012) or a truly significant enabler (see e.g., Luechinger et al., 2007; Battiston and Mascitelli, 2008; Hodler et al., 2015).

Undesired indirect effects have been common when convenience voting has been introduced to overcome barriers to voting. This reflects the inherent paradox of facilitation. If a given facilitation instrument is targeted to all potential voters, it typically does not lead to an evenly distributed boost in participation but, instead, intensifies the socioeconomic bias in turnout by mobilizing those groups that were more active originally (for a summary, see Galicki, 2017; Wass et al., 2017). In such cases, an increase in disparities in participation between different groups in society can either be an unforeseen or an anticipated (but accepted as a risk) indirect consequence of the reform, leading to a trade-off between turnout and equality. The other option is to introduce instruments that are, by definition, targeted to marginalized groups or otherwise identified specific segments of the electorate, such as voters residing abroad, elderly voters, or voters with disabilities (see e.g. Tokaji and Colker, 2007). However, that leads to a different type of trade-off in which participation among certain groups is facilitated at the expense of equal voting opportunities (cf. Wass et al., 2017).

Such complexities may help to understand why introducing new forms of voter facilitation is often a long and multifaceted process in which the original aims can be difficult to trace afterward. This also highlights the importance of a comprehensive assessment of the outcomes of reforms instead of focusing on a sole indicator, such as turnout (see James and Garnett, 2020, 124). In order to illustrate the process, the next section examines a Finnish case in which the expansion of convenience voting has developed gradually over the past 50 years.

Postal voting is one way to organize elections so that voting can occur outside the actual election day. In Finland, postal voting has been framed as a novel variant of advance voting available only to a specific group of voters. Hence, to trace its path into electoral legislation and the related policy process, we first need to explore the legislative history of advance voting.

When the Finnish electoral system was first crafted in the beginning of the 1900s, it included one form of convenience voting for parliamentary elections: voting based on a register extract. Citizens could vote outside their own electoral district if they had ordered an extract from the register that proved them eligible (Tarasti, 1987, 28). This rather cumbersome procedure provided flexibility in terms of location but not timing—all ballots had to be cast on the (then two) election days. It was not until the 1950s that advance voting was introduced in the Finnish electoral system as a concession to ease access to the polls for voters in exceptional situations (see Tarasti and Jääskeläinen, 2014, 50; HE 48/1955, 6).

Over the years, advance voting developed in a more inclusive and mainstreamed direction. When the 1969 Parliamentary Elections Act extended advance voting from the embassy-based overseas polling stations and ships under the Finnish flag to include voters staying within the borders of Finland, the voting register extract requirement was finally dropped (see Tarasti and Jääskeläinen, 2014, 47). However, advance voters were obliged to report a reason for being “likely to be prevented” from voting in their own electoral district on the actual election days (which included two at that point) by noting the reason in the cover letter for their advance vote (Laki kansanedustajain vaaleista, 1969, §63). No formal evaluation was conducted concerning the acceptability of the reasons; the obligation only underlined the exception character of advance voting. The primary target group for this exception was voters who were being treated in specific institutions (hospitals, nursing homes), but travel and difficult traffic conditions were also considered as legitimate hindrances potentially preventing voters from reaching the polls on election days (Hallituksen esitys Eduskunnalle valtiollisia vaaleja koskevan lainsäädännön uudistamisesta, 1969). Advance voting was framed as a technical improvement that helped the country’s voting system to keep up with the quality of the electoral systems of the other Nordic countries that formed Finland’s most important reference group in this regard. The government bill concluded that advance voting would significantly facilitate citizens’ participation in elections, improve the reliability of the electoral system, and speed up the vote counting process, hence, advancing the announcement of election results (ibid).

During the 1970s and 1980s, advance voting was extended to include new types of institutions, such as psychiatric hospitals, prisons, residential homes, and finally, the homes of the disabled and chronically ill (Tarasti and Jääskeläinen, 2014, 48–49). Overall, the electoral administration was consistently developed in the direction of making voting easier–with the exception of abolishing the second election day in the 1991 parliamentary elections (Pesonen et al., 1993, 15). In 1985, the requirement to report the reason for being prevented from voting on election day was dissolved (Laki kansanedustajain vaaleista annetun lain muuttamisesta, 1985). The principle of the primacy of election day, however, did not disappear until the 1998 Elections Act, which stipulated that: “(t)he elections are conducted by advance voting and voting on the election day” (Vaalilaki, 1998, §4). This relaxed approach has been reflected in the voters’ behavior. Already at the 1991 parliamentary elections, more than 40 percent of the voters used advance voting (Pesonen et al., 1993). With only a slight drop at the turn of the 2000s, the popularity of advance voting has consistently increased since the 2007 parliamentary elections (Wass and Borg, 2012, 103).

As this short summary demonstrates, introducing new forms of convenience voting is a gradual and fairly conservative process. Not all changes have been adopted effortlessly, nor have the amendments always been generous in extending newly established rights. For instance, the registered family caregiver for the home voter was initially not given permission to vote when the electoral committee visits (§46). Also, voting in institutions continues to be restricted to patients/residents/inmates, while excluding the staff (Vaalilaki, 1998, §46). Still, these past amendments help to make sense of the lengthy political process preceding the adoption of postal voting in 2017.

Although postal voting is available for all eligible voters in many countries, Finland limits postal voting to only non-resident citizens and those temporarily staying abroad during the elections. Hence, it is clearly the type of facilitation instrument that is targeted to a specifically defined segment of the population rather than to the electorate as a whole. This restriction becomes understandable when looking at the history of the reform. Unlike in the case of advance voting, the initiative to incorporate postal voting into the electoral system was not taken by political parties or electoral authorities but by two NGOs: the Finland Society and the Finnish Expatriate Parliament (FEP). The FEP called for the introduction of postal voting in each of its sessions from the year 2000 onwards (FEP Resolutions, 2015; 2012; 2010; 2007; 2005; 2002; 2000). According to the resolutions, postal voting enhances non-resident Finns’ political rights and social connectedness to Finland.

Improving voting opportunities for Finns living abroad was highlighted in the government policy programs for non-resident Finns for 2006–2011 and 2012–2016, in which the introduction of postal voting was presented as a possible way to increase the overseas voting turnout. In 2017, a change to the Election Act that included the adoption of postal voting was enacted (Hallituksen esitys eduskunnalle laiksi vaalilain muuttamisesta, 2017), and was enforced in 2018 (Laki vaalilain muuttamisesta, 2017). For advocacy groups, particularly the Finland Society and the FEP, this marked a substantial victory in a long battle. Although postal voting can be perceived as the last step in a long continuum of expanding voter facilitation, at the same time, it constitutes a completely new way of voting for Finnish elections: requirements are omitted related to specific sites and the presence of an electoral authority.

The Election Act (Vaalilaki, 1998, §66) postulates that eligible Finnish citizens who do not have a domicile in Finland or who will be abroad throughout the advance voting period and on election day are entitled to vote by mail. To do so, they must order the required documents from the subscription service of the Ministry of Justice and deliver their ballot, at their own expense, to the Central Electoral Commission of the correct municipality no later than two days before the election. Furthermore, two adults must be present at the voting situation as witnesses and must confirm their presence with their signatures and contact information, which must be submitted along with the sealed ballot. In essence, much responsibility rests on the individual voter instead of on the electoral authority in postal voting, which is one of the main reasons why its implementation faced so many obstacles over the past few decades and why decision makers have been hesitant to expand it to include all voters (cf. Oikeusministeriö, 2021).

Indeed, the main concern regarding postal voting has been maintaining the secrecy of the vote. It is because of the potential implications for electoral secrecy that postal voting has been considered a significant systemic change by the electoral authority. A Finnish Constitutional Law Committee report (Valiokunnan mietintö, 2017) noted that electoral secrecy is important as a right of the voter, but it also serves the interest of the state, as it helps to guarantee that elections express the rights and independent will of the people. In fact, the electoral act includes multiple measures to ensure the preservation of electoral secrecy, and the responsibility for the act’s practical implementation lies with the electoral authority. However, when voting by mail, the electoral authority is not present at the vote and, thus, cannot monitor it. Postal voting potentially poses various risks to election secrecy, such as the voter being pressured, the ballot being shown to another person, or someone other than the voter marking the ballot. The demand for two witnesses is an attempt to minimize these risks and to somewhat substitute for the oversight of the electoral authority (Valiokunnan mietintö, 2017).

The secrecy of the vote continued to be the main concern when the possibility of extending the right to vote by mail was discussed prior to the Finnish elections that took place during the pandemic. According to the Ministry of Justice (Oikeusministeriö, 2021) memorandum on the issue of postponing the municipal elections from April to June 2021, extending postal voting to voters living in Finland in a pandemic situation would not solve the problems related to the COVID-19 pandemic. First, the presence of two witnesses would be difficult under the conditions of the pandemic, and second, voting without witnesses would pose a risk to election freedom and election security. In addition to remarks regarding the postal service, it was further observed that postal voting abroad already constitutes an exception to the general rule of voting under the supervision of election authorities. A large-scale extension of the exception would, according to the memorandum, lead to a fundamental change in the Finnish electoral system.

What the memorandum (Oikeusministeriö, 2021) does not discuss is the fact that another, less essential part of the Finnish municipal decision-making structure has been making use of postal voting since 1990 (Laki neuvoa-antavissa kunnallisissa kansanäänestyksissä noudatettavasta menettelystä, 1990). For advisory referendums, often 80–90 percent of the votes are cast by mail, while only a fraction of voters go to the polls on the actual day of the referendum vote (Oikeusministeriö, 2019). To date, 63 municipal advisory referendum votes have been conducted, chiefly regarding municipal mergers (ibid.). With the referendum defined as only a consultation device, supervising electoral secrecy on these votes has been deemed less important than easy access to participation. In fact, the postal voting procedure for the municipal referendum does not even require witnesses (Laki neuvoa-antavissa kunnallisissa kansanäänestyksissä noudatettavasta menettelystä, 1990, §10). The existing literature on the Finnish municipal referendum (e.g., Büchi 2011; Jäske 2017) has not scrutinized the aspect of ballot secrecy, despite the fact that qualitative case studies on municipal referendums can help to gain insight into the practice of voting without oversight.

After postal voting finally became part of Finnish electoral legislation, the 2019 parliamentary elections provided the first opportunity to test postal voting in practice. Who chose the postal voting option and why? Did voters find the procedure convenient or cumbersome? What worked and what did not? To study voters’ perceptions and experiences, we used a survey conducted by the project “Facilitating Voting from Abroad (FACE).” Especially designed to study political engagement among non-residents, the questionnaire covered issues like political trust, satisfaction with democracy, geographical identity, membership in various groups, and issue saliency, as well as views on policies concerning non-residents and experiences with postal voting.

Data collection began soon after the 2019 parliamentary elections held in April and lasted from May 23 to September 30, 2019. The incoming Finnish government presented its program only 10 days after we dispatched the first invitation letters (see Arter, 2020). Hence, this gives little reason to worry that the Finnish politics would have any strong influence over respondents’ answers in the survey during the duration of data collection.

To conduct the survey, we requested a disproportionate stratified random sample of 10,000 adult Finnish citizens eligible to vote, registered as Finnish or Swedish speakers, from the Population Register Centre of Finland. The sample is random in a sense that these 10,000 adult citizens were selected randomly from the database of all non-resident citizens registered in the population register. In addition, the sample is stratified since we set quotas for a maximum number of expatriate citizens living in the 17 largest Finnish diasporas (i.e., 1,500 from Sweden, 500 from all other countries such as the United States, German, United Kingdom, etc.). Without these quotas, there would be a risk of the sample being overpopulated with residents in Sweden, and potentially the United States, Germany, the United Kingdom, and Canada, which are the countries with largest Finnish diasporas. Finally, the sample is disproportionate because these quotas do not reflect the proportion of Finns living in these countries.

These 10,000 Finns residing abroad were then invited to take a place in the FACE survey held online. Nevertheless, the invitation was paper-based and delivered to their physical addresses included in the Finnish Population Register. Each paper invitation included a unique six-digit code which enabled us to confirm that the responses are legitimate. Overview of the Finnish diasporas and their representation in the survey are presented in Supplementary Table S1 and Supplementary Figure S1 in the supplementary material.

As a mobilization attempt, the research project and data collection were promoted by the non-resident Finns’ organization Finland Society’s members’ magazine Finland Bridge, and reminders were sent through various “Finns abroad” Facebook groups urging those invited to participate. Approximately 40 participants outside of the original sample also signed up for the survey, corresponding to two percent of the respondents.

In total, 2,100 individuals responded to the survey with an effective response rate of 20 percent. Although the response rate may seem rather low in comparison to similar surveys collected among resident citizens, it is largely in line with other surveys collected among citizens abroad. In two previous larger data sets collected from non-resident citizens, the response rate varied between 20 and 30 percent (Solevid 2016; Peltoniemi, 2018a, 2018b). One reason for the relatively low response rate relates to expired address information in the Population Register Centre of Finland. However, the magnitude of this problem is difficult to accurately assess as the letters are not returned to the sender. According to an estimate by the Population Register Centre of Finland, the information for approximately one third of the addresses may have been invalid.

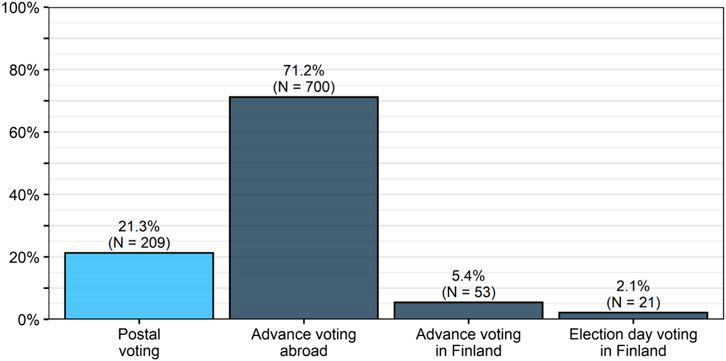

Our empirical section consists of two parts. First, we examine the propensity of postal voting using logistic regression (0 = voted using some other method, 1 = voted by mail). Out of the 983 respondents who reported that they voted in the 2019 elections either abroad or in Finland, 209 (21.3%) voted via post (see Figure 2). As the primary motivation for this study is to learn lessons for postal voting if applied to all voters, we focus on voters’ views regarding postal voting and use their sociodemographic and socioeconomic characteristics only as controls. Hence, the results tell more about the procedural aspects than about the actual correlates of postal voting among non-residents, which have been studied elsewhere (Peltoniemi et al., 2020; Nemčok and Peltoniemi, 2021). Due to the missing control covariates, the total number of observations available for the regression analysis is 678.

FIGURE 2. Adoption of various voting methods in the 2019 parliamentary elections among Finnish citizens residing abroad (and participating in the FACE survey).

For this part of the empirical analysis, we used a battery of questions that covered various aspects of postal voting experience, ranging from signing up and ordering the required materials to sending the ballot. These eleven survey items were combined into four factors 1) Sign-up and preparatory requirements, 2) Voting procedural requirement, 3) Trust in reliability of postal services, and 4) Trust in voting integrity, all ranging from 0 (low demands or low trust) to 1 (high demands or high trust). Overview of the questions included in each factor is presented in Supplementary Table S2 (for overview of the responses, see Supplementary Figure S2).

The questions included in each factor yielded sufficiently high measurement invariance (i.e., Cronbach’s alpha) 0.79, 0.74, 0.71, and 0.79, respectively. The additional principal component analysis based on all eleven questions confirmed that optimal number of principal components is four (see four eigenvalues larger than one in Supplementary Table S3 in the supplementary material). Supplementary Figure S4 in the supplementary material showcases how these individual survey items contribute to the quality of representation on each dimension. At the same time, the questions grouped under the same factor reveal consistent correlations, as presented in the variable correlation plot in Supplementary Figure S3 in the supplementary material. Yet, the resulting four factors are not highly correlated (r ranging between −0.28 and 0.26, see Table 1), thus they can be included in the same model without multicollinearity issues. Therefore, all these results suggest that the four main factors have sufficiently high construct validity, and their use imposes no concerns for the validity of findings reached in this part of our empirical examination.

In addition to these four main factors, our control variables included gender, age, education, subjective relative social status, political interest, sense of civic duty to vote, and self-rated health. We also included a self-perceived distance to the nearest polling station, identified as a relevant covariate associated with voters’ decision to cast their ballot via post (see Peltoniemi, 2018b; Nemčok and Peltoniemi, 2021).

In the second part of the analysis, we looked at respondents’ perceptions and practical experiences with postal voting. Here, we drew from responses to the following three questions: 1) “What was, or which were, the most important reason(s) why you decided not to vote (in the 2019 Finnish parliamentary elections)?” (an open-ended question); 2) “In your opinion, which would be the most effective means for increasing turnout in Finland’s elections among emigrants?” (entries for the option “other” at the end of a multiple-choice item); and 3) “How well do you consider Finnish emigrants’ issues have been taken care of in Finland?” (entries for the option “other” at the end of a multiple-choice item).

Altogether, 1,014 respondents entered a response to one or more of these questions. Entries related to postal voting, 145 in total, were identified by the searches “postal,” “kirje (letter in Finnish),” “posti,” “brev (letter in Swedish),” and “post” in Atlas.ti. Approximately five percent of these entries were generally positive comments, for instance, expressing appreciation for the opportunity for postal voting. Most of the entries, however, addressed different problems that the respondents had either experienced themselves, heard of, or otherwise perceived. They help in understanding why only approximately half of the postal voting packages ordered were successfully returned (Suomi-Seura, 2019). The entries were coded into different theme categories, so one entry could be included in one or more categories (see Supplementary Table S4).

As postal voting was possible for the first time in the 2019 elections, many expectations and much interest were placed on the election results. Turnout among non-resident Finns has traditionally been remarkably low, fluctuating between five to ten percent during the past few decades. In fact, in 2019, the participation rate of 12.6 percent broke the record. Among all voters, 14 percent decided to test postal voting. When comparing the official figures derived from the voter register to our sample, two observations stand out. First, reported turnout was four times higher. Although over-reporting is a common feature in surveys (e.g., Dahlgaard et al., 2019; Lahtinen et al., 2019), it was particularly pronounced in our sample. This is most likely due to two interrelated reasons. First, those who received the questionnaire have been active in updating their address information with Finnish administrators, which is a clear indication of their mental connection and sense of belonging with their country of emigration. Second, the decision to respond to the questionnaire shows a high level of interest in Finnish politics, which usually manifests itself at the level of action. In a similar but milder fashion, the proportion of postal voters was higher than the actual share among non-resident Finns.

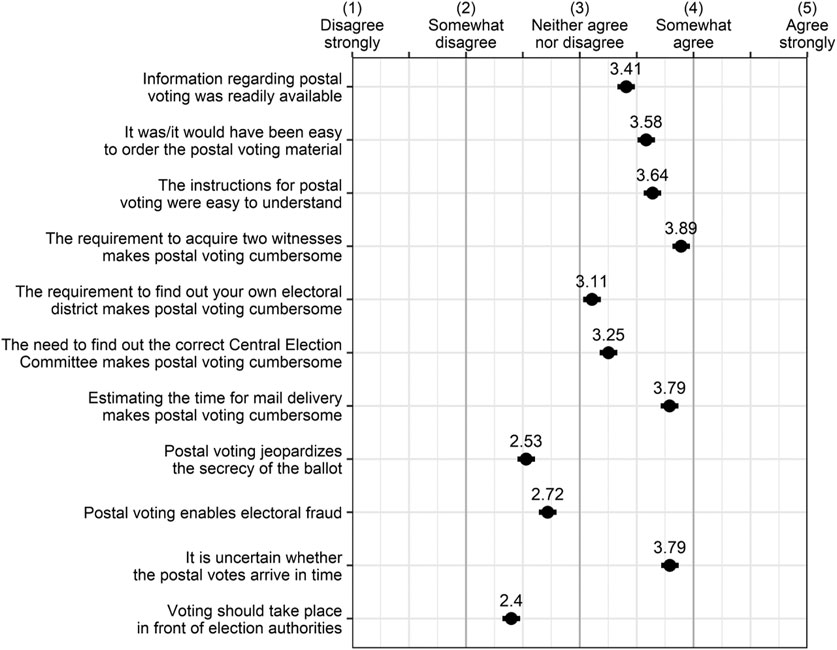

Figure 3 shows respondents’ average views on 11 statements about postal voting that were posed in the survey before the question asking whether they had voted in the election. For some statements, opinions were evenly distributed (average is around 3, i.e., “neither agree, nor disagree”), while for others, the opinion is skewed toward one side—either agreed or disagreed. Several interesting observations stand out when distribution of individual responses is examined (see Supplementary Figure S2). First, the overall level of trust in postal voting seems high: less than a quarter of respondents indicated that it jeopardizes the secrecy of ballots or enables electoral fraud. Even fewer (20%) noted that they are convinced that voting should take place only in front of electoral authorities. Less than 10 percent agreed that mailing their votes makes the act of voting seem utterly ordinary (9%). Second, respondents reported distinct hurdles and grievances that relate to postal processes. Many seemed to worry about estimating the time for mail delivery relative to receiving the required materials for postal voting (67%), mailing the actual ballot (63%), and arrival of their ballot, specifically, two days before election day (68%). Third, the requirement to acquire two witnesses was perceived as a bureaucratic obstacle: 71 percent felt that it made postal voting cumbersome. Finally, respondents seemed quite satisfied with the availability and accessibility of information.

FIGURE 3. Average of the responses to the individual survey items measuring various attributes among participants. Lines depict 95% confidence intervals.

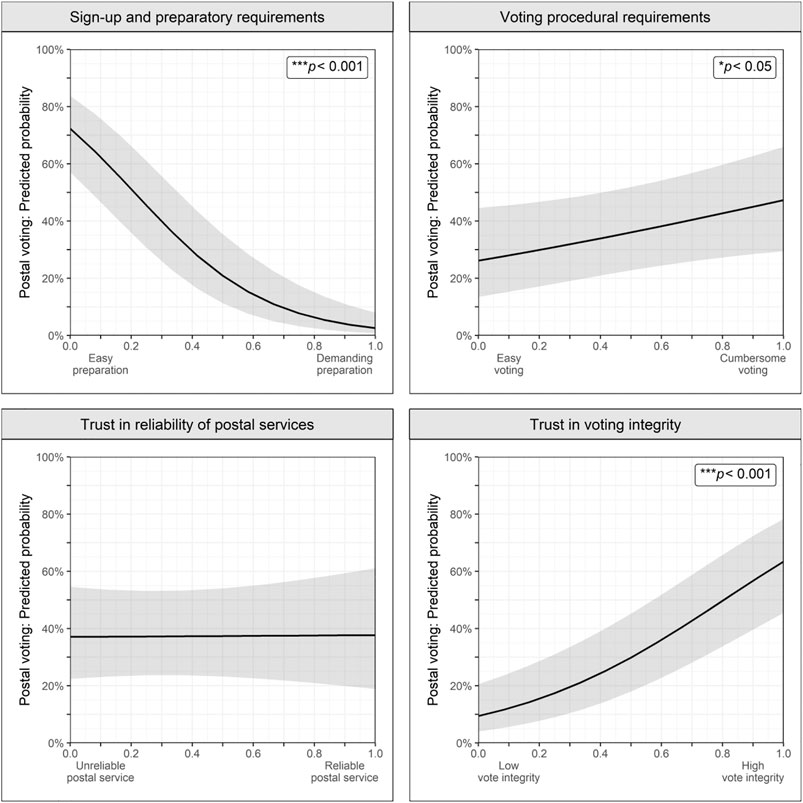

As outlined in the methodological section, we grouped the survey questions into four internally consistent blocks: 1) Sign-up and preparatory requirements, 2) Voting procedural requirements, 3) Trust in reliability of postal services, and 4) Trust in voting integrity (see Supplementary Table S2 in the supplementary material). The regression results shown in Table 2 suggest that all blocks except perceived reliability of postal services had a statistically significant association with the propensity to vote by mail. As can be expected, those who felt that preparatory tasks required a lot of effort from an individual voter were considerably less likely to cast their vote by mail (see marginal effects in Figure 4). However, the opposite holds true when looking at the procedural requirements for the act of voting itself: finding them cumbersome, in fact, increased the likelihood of voting. This seemingly counterintuitive result probably stems from reverse causality: only those who actually voted via mail were aware of all the practical obstacles along the way. Furthermore, as these questions were asked in retrospect, respondents may have also wanted to send a signal to the election administration. The association between trust in the integrity of postal voting and the decision to do so in practice was strong and ran in the expected direction.

FIGURE 4. Predicted probability for postal voting. The marginal effects of perceptions of postal voting procedures. Notes: Estimates are based on model 2 in Table 1. Labels in the upper right of each panel signify statistical significance of the variables: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Here, we focus on two frequently mentioned themes that appeared in the written survey entries on postal voting as points requiring the attention of those who implement policy: timing and witness issues (for the thematic coding frequencies, see Supplementary Table S4). Examples from the survey responses are presented in italics.

“The postal voting papers should have been ordered who knows how long in advance. This was the main reason for not voting. I was also not informed about the possibility of postal voting in any way. I just happened to see it in a Facebook group (…). It’s great that such an opportunity now exists, but there is quite a lot of room for improvement in its implementation.”

Slightly over a third of the 145 responses analyzed here indicated that the respondent was unaware of the possibility of postal voting or that this information had reached them too late. In terms of communication about elections, non-resident Finnish citizens form an especially hard-to-reach group: their physical addresses in the Finnish registers may be outdated, they may not subscribe to any official electronic services in Finland, or they may not follow the Finnish media frequently enough to catch all the important news. The availability of information and its timing are part of this challenge for both the authorities and the political parties. When the main public campaigning phase is just beginning in Finland, the potential overseas postal voters living farthest away should already have ordered the postal voting package, as the mail can take a month or longer to travel to the United States and Australia, for example. The Ministry of Justice service for ordering materials opened three months in advance of election day.

The mail service, in general, was mentioned in many written responses. Some responses indicated that the postal voting material they had ordered arrived too late. It seems that the phenomenon of only a little more than half of the postal voting packages ordered being returned can be partially explained by situations in which the recipients estimated that their ballots would not make it back to Finland on time, so they did not vote. It was also possible to reorder the package, which some may have done if their initial order failed to arrive in time, thereby boosting the number of orders in relation to the actual number of eligible voters behind the orders. Figures for late postal votes were only available from three municipalities in the metropolitan area, but they indicate that the problem was not insignificant: these three municipalities received 830 timely and 77 late postal votes.1

In the survey, 71 percent of the respondents (n = 1,262) strongly or somewhat agreed with the statement “The obligation to obtain two witnesses makes postal voting cumbersome.” The witness practice was commented on in 24 responses, including some outright critical comments (see below). Fifteen explicitly stated that they had abstained due to the witness requirement:

“Requiring two witnesses is ridiculous, as it is completely impossible to control the validity of the signatures or even the identities of the witnesses. A typical product of Finnish bureaucracy, whose existence nobody can reasonably justify.”

“It’s no democracy that I would have to hang out in Finnish circles to get two witnesses for the postal vote. If the instructions were also in English, I would have had two witnesses and voted.”

One reason for the difficulty in obtaining witnesses was the language of the postal voting package: most of the text was only available in Finnish or Swedish. The benefits of multilingual information also applies to the domestic electorate. The other point raised in the respondent excerpt cited refers to the reliance on other people to conduct one’s individual postal vote, which the witness requirement imposes. In the pre-COVID-19 experience of the Finns abroad, this primarily involved having close enough contacts and being willing to ask two of them to serve as witnesses. As such, some considered this limiting and/or unpleasant.

The government bill to amend the Electoral Act (HE, 2017) justifies the witness requirement by the opportunity it provides to the Central Municipal Election Boards to assess “the lawfulness of the postal voting that had taken place (…) to a higher degree than by the voter’s own affirmation alone.” The bill, nonetheless, also concludes that “the Central Municipal Election Board would not (…) be able to assess the authenticity of the signatures as such, but would only inspect that the cover letter contains the signatures of two witnesses.” In this situation, the witness requirement may seem a pure formality from the voter’s point of view and may even tempt some voters to conduct electoral fraud in the form of forged signatures. As the significance of the requirement may not appear obvious to the voters, it should be carefully and explicitly communicated.

Adaptation to the global pandemic has caused a rapid and dramatic shift in organizing elections (James, 2021). Different forms of convenience voting have quickly become the center of attention as democracies all over the world have struggled to find innovative ways to ensure safe voting practices under crisis conditions (see e.g., Fernandez Gibaja, 2020; Gronke et al., 2020). These have included practical measures (use of hand sanitizer, masks, disposable pens, temperature checks) and operational arrangements (increased number of polling stations, extended voting hours, drive-in voting), as well as amendments to electoral legislation. The most recent example of the latter occurred in the Netherlands, which enacted specific COVID-19 electoral law, including expansion of proxy voting to three persons and expansion of postal voting from emigrants to voters above 70 years of age and extending election day to three days. Furthermore, most countries have provided specific voting opportunities for ill and/or quarantined persons, including home and institutionalized-based voting and particular safety measures in polling stations. Only a small number of countries restricted persons with COVID-19 from voting (Asplund et al., 2020).

As each country has its own electoral legislation, including both opportunities and constraints for introducing new facilitation instruments, few one-size-fits-all solutions are available. However, inspection of country-specific conditions offers valuable insights for a joint endeavor to improve the pandemic-sustainability of elections: while observations are not generalizable as such, lessons learned from one context can substantially help electoral engineering in others. In this study, we took a closer look at Finland, which simultaneously stands out as a benchmark case relative to advance voting and as a cautionary example with its recent and relatively restricted framework for postal voting. Drawing from a survey conducted after the 2019 parliamentary elections among non-resident Finns, the only group that is allowed to vote by mail, we focused on voters’ perceptions. Such an inquiry has relevance, as the decision to postpone the 2021 municipal elections opened a window of opportunity to develop postal voting and potentially expand it to the entire electorate to better cope with similar situations in the future.

Our results show that the overall level of trust in the integrity of postal voting is strong. This is an important observation, as a lot is at stake: recent cross-national evidence suggests that violations of electoral integrity, including fairness of electoral officers and fair counting of the votes, decrease voters’ overall satisfaction with democracy as a political system (Norris, 2019). As can be expected, higher trust is associated with a higher propensity to vote by mail. This is in line with previous findings by Nemčok and Peltoniemi (2021), who noticed that trust acts as a moderator between distance to the polling station and an emigrant voter’s probability of postal voting. The most noteworthy obstacles to postal voting related to bureaucratic burden include the requirement to have two witnesses, on one hand, and concerns related to the security of mail on the other. These observations came up also in the qualitative part of the analysis and clearly constitute areas in need of improvement.

There are three main lessons learned from the use of postal voting abroad if applied to domestic context in general or in crisis situations. First, the role of postal services is pivotal. With the overall demand for delivery of letters declining, postal services and their public regulation remain under severe pressure (Decker, 2016). In the case of voting from abroad, the challenges are accentuated, and relate to the voters’ sense of uncertainty of (timely) delivery, multiple timing issues, as well as the difficulty of reaching the policy goal of equality of eligible voters in different parts of the world. In a domestic setting, the postage of the voting letter can be prepaid, but the question remains whether the state should offer a costly tracked delivery, enhancing the voters’ sense of trust in the service.

Second, the requirement of having two witnesses needs to be reconsidered. In a pandemic situation, the witness requirement may impose a health risk to those involved, which weighs against the suitability of postal voting to facilitate elections in a pandemic (Krimmer et al., 2021). In the case of Finns living abroad, decision makers deemed it reasonable that the voter involve two adults not from their immediate family to enable participation in postal voting. The questions of responsibility and assistance also arise when we reflect on the potential of postal voting under pandemic conditions. The memorandum on postponing the 2021 Finnish municipal elections (Oikeusministeriö, 2021, 11) suggests that, in addition to the main concern for ballot secrecy, the logistics of moving the ballot letter from one place to another would render postal voting ineffective or infeasible for those quarantined or isolated. This is because those under quarantine or isolation should not leave their place of confinement to access the mailbox. Furthermore, those obliged to confinement immediately before election day would not be able to organize the postal vote due to the time required for the postal voting package to be ordered, sent, and returned.

Here, in contrast to the Finns abroad case, a point of departure is that the voting method needs to be manageable by the voter alone, which is also the case when faced with the exceptional situation of an individual who is quarantined or in isolation and may rely on others for their subsistence. The electoral logistics could be aided if the voter were allowed to use personal assistance, for instance, for fetching a postal voting package from a polling station and delivering it back to the station or to the closest mailbox. Also, last minute postal votes could be saved if postal votes were valid when mailed no later than election day. Confirming the election results somewhat later than under regular conditions would simply count as one of the many inconveniences we need to bear during a health crisis.

With the current witness requirement forming a barrier for the safe use of postal voting in the context of a pandemic, alternatives should be given due attention. At least two approaches can be pursued: 1) organizing the oversight without physical presence, or 2) suspending the requirement temporarily. First, the event of marking the ballot can take place in a video conference between the voter and the witnesses, just as other meetings have been held virtually during the pandemic. In such a setting, the witnesses could either be trained and authorized by the electoral committees as electoral assistants, or they could be private citizens who have not gone through an authorization procedure, as is the case with Finnish overseas postal voting.

Authorized electoral assistants could virtually visit postal voters according to bookings, similar to the way traditional home voting is conducted. This variant of video oversight would demand a considerable number of volunteers. The documentation, on the other hand, would be less problematic, as the witnesses could simply keep a log in an internal secured system on whose postal votes they confirmed as lawfully cast. Allowing private individuals to organize their online voting meetings without any preauthorization of witnesses would burden the electoral committees less but would necessitate an online system using strong authentication for recording the witness affirmations, replacing the ink-on-paper signatures. This alternative would be equally as vulnerable as the paper version to witnesses “just signing” to help a friend without actually witnessing the marking of the ballot.

The second approach, a temporary suspension of the witness requirement, offers the simplest solution to the problem. This solution was applied in the United States during the pandemic, with some courts weighing cases in favor of voting rights (Hasen, 2020). More research is needed to scrutinize which practices, if any, make it possible to maintain lawfulness and a high level of electoral integrity in settings in which postal voting takes place without witnesses. To what extent the witness requirement works to guarantee the lawfulness of the postal vote should also be further investigated (see Weide, 2021).

Third, if postal voting will be applied in the domestic context, both the information and timing issues would be less pressing but still important to consider. In the case of the municipal advisory referendum, the postal voting material is automatically sent to eligible participants (Laki neuvoa-antavissa kunnallisissa kansanäänestyksissä noudatettavasta menettelystä, 1990, §9) in the same way that the notification card of eligibility to vote is for elections. Automatic subscription of the postal voting material may be especially convenient in the case of pandemic conditions when the need for physical distancing or isolation may occur on short notice. The risk of ballots being received and used by anyone other than those intended, despite the address register being more accurate than it is for citizens abroad, would have to be weighed against the value of securing an option for participation.

What can be as expected in terms of policy process now that the issue of postal voting extension is on the agenda? The problem as such has already been clearly identified: while the electoral administrators in the municipalities could have been able to organize health-safe municipal elections in the original schedule, voting itself might not have been safe or even possible for everyone entitled vote. This is a clear indicator of deficits in the existing electoral legislation to which domestic postal voting can provide at least a partial solution. Hence, the window of opportunity to proceed with the reform has opened with a widespread consensus of its necessity. In this endeavor, experiences from postal voting in the 2019 elections constitute a valuable reservoir for knowledge-based decision-making. However, it is important to note that if the possibility of postal voting will be extended to all eligible voters, some of the associations we discovered among non-resident voters might not apply. This emphasizes the need to study carefully the implications of this possible electoral reform. Furthermore, also context matters citizens might evaluate postal voting differently during a pandemic than in normal conditions when voting in person is perfectly safe. During a pandemic, citizens might be willing to condone certain complexities of the postal voting system, since the most important point is guaranteeing voters’ safety, even if this comes at the expense of some extra effort.

The most likely next step is that the Ministry of Justice will commission an overall assessment of the pros and cons of different models, as the Constitutional Committee recommended in their statement (Valiokunnan mietintö, 2021). One option would be to allow postal voting for everyone like in Australia, Germany, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and some states in the United States (where five states run all-mail elections). Another option is to allow it for specific groups of voters, which was the case in the Netherlands in spring 2021. These models will be deliberated by a parliamentary committee formed by party secretaries, civil servants and academics. If it will end up recommending some form of extended postal voting and the government decides to make a proposition to the Finnish parliament accordingly, it will be thoroughly discussed in the Constitutional Committee. The Constitutional Committee will hear experts, who will consider the proposition vis-à-vis basic rights guaranteed in the constitution, and possibly different stakeholders. Although the process is formally as complex as always, it might proceed more fluently than usually. The pressure to make elections work even in crisis is high, particularly with the dense electoral cycle for the upcoming years.

The data sets generated for this study will be available in the Finnish Social Science Data Archive after the ongoing research project “Facilitating Electoral Participation from Abroad” (FACE) is completed in 2021. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to https://www.fsd.tuni.fi/en/.

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

The article has been written as part of the research project “Facilitating Electoral Participation from Abroad (FACE)”, funded by the Finnish Cultural Foundation (project number 4706258); the research project “Tackling the Biases and Bubbles in Participation (BIBU)”, funded by the Strategic Research Council (SRC) at the Academy of Finland (project number 312710), and the research project “Politiskt beteende i den finlandssvenska diasporan”, funded by the Society of Swedish Literature in Finland.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The authors would like to thank JS and DM for their valuable comments.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2021.692396/full#supplementary-material

1The information was gained in personal e-mail communication between one of the authors (Weide) and Arto Jääskeläinen, the head of elections, Ministry of Justice.

Arter, D. (2020). When a Pariah Party Exploits its Demonised Status: the 2019 Finnish General Election. West Eur. Polit. 43 (1), 260–273. doi:10.1080/01402382.2019.1635799

Asplund, E., Stevense, B., James, T., and Clark, A. (2020). Elections Need to Be Accessible for the Ill during COVID-19 to Avoid Disenfranchisement. Int. IDEA Commentary. Available at: https://www.idea.int/news-media/news/elections-need-be-accessible-ill-during-covid-19-avoid-disenfranchisement (Accessed March 18, 2021).

Battiston, S., and Mascitelli, B. (2008). The Challenges to Democracy and Citizenship Surrounding the Vote to Italians Overseas. Mod. Italy 13 (3), 261–280. doi:10.1080/13532940802069572

Büchi, R. (2011). “Local Popular Votes in Finland - Procedures and Experiences,” in Local Direct Democracy in Europe. Editor T. Schiller (Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften), 202–225. doi:10.1007/978-3-531-92898-2_12

Dahlgaard, J. O., Hansen, J. H., Hansen, K. M., and Bhatti, Y. (2019). Bias in Self-Reported Voting and How it Distorts Turnout Models: Disentangling Nonresponse Bias and Overreporting Among Danish Voters. Polit. Anal. 27 (4), 590–598. doi:10.1017/pan.2019.9

Decker, C. (2016). Regulating Networks in Decline. J. Regul. Econ. 49 (3), 344–370. doi:10.1007/s11149-016-9300-z

FEP Resolutions (2007). Päätöslauselmat 2007. 50/2007. Available at: https://suomi-seura.fi/usp-paatoslauselmat-istunto-2007/ (Accessed March 24, 2021).

FEP Resolutions (2005). Päätöslauselmat kokonaan 2005. 64/2005. Available at: https://suomi-seura.fi/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/p%C3%A4%C3%A4t%C3%B6slauselmat-kokonaan-2005.pdf (Accessed March 24, 2021).

FEP Resolutions (2015). Ulkosuomalaisparlamentin kahdeksannen istunnon 22.–23.5.2015 päätöslauselmat. 2/2015. Available at: https://suomi-seura.fi/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Paatoslauselmat_2015.pdf (Accessed March 24, 2021).

FEP Resolutions (2010). Ulkosuomalaisparlamentin kuudennen varsinaisen istunnon 24.–25.5.2010 päätelauselmat. 3/2010. Available at: https://suomi-seura.fi/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Paatoslauselmat2010.pdf (Accessed March 24, 2021).

FEP Resolutions (2012). Ulkosuomalaisparlamentin seitsemännen varsinaisen istunnon 26.–27.10.2012 päätöslauselmat. Available at: https://suomi-seura.fi/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/lauselmat-2012-SU-netti.pdf (Accessed March 24, 2021).

Fernandez Gibaja, A. (2020). Transforming Political Parties in the Middle of a Pandemic: The Moment for Online Voting? Available at: https://www.idea.int/news-media/news/transforming-political-parties-middle-pandemic-moment-online-voting (Accessed March 24, 2021).

Galicki, C. (2017). Convenience Voting and Voter Mobilisation: Applying a Continuum Model. Representation 53 (3–4), 247–261. doi:10.1080/00344893.2018.1438307

Giammo, J. D., and Brox, B. J. (2010). Reducing the Costs of Participation. Polit. Res. Q. 63 (2), 295–303. doi:10.1177/1065912908327605

Gronke, P., Manson, P., Lee, J., and Foot, C. (2020). How Elections under COVID-19 May Change the Political Engagement of Older Voters. Public Pol. Aging Rep. 30 (4), 147–153. doi:10.1093/ppar/praa030

Gronke, P., and Miller, P. (2012). Voting by Mail and Turnout in Oregon. Am. Polit. Res. 40 (6), 976–997. doi:10.1177/1532673X12457809

Hallituksen esitys eduskunnalle laiksi vaalilain muuttamisesta (2017). HE 101/2017 vp. Available at: https://www.eduskunta.fi/FI/vaski/HallituksenEsitys/Documents/HE_101+2017.pdf.

Hallituksen esitys Eduskunnalle valtiollisia vaaleja koskevan lainsäädännön uudistamisesta (1969). HE 24/1969 vp.

Hasen, R. L. (2020). Three Pathologies of American Voting Rights Illuminated by the COVID-19 Pandemic, and How to Treat and Cure Them. Election L. J. Rules, Polit. Pol. 19 (3), 263–288. doi:10.1089/elj.2020.0646

Hodler, R., Luechinger, S., and Stutzer, A. (2015). The Effects of Voting Costs on the Democratic Process and Public Finances. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Pol. 7 (1), 141–171. doi:10.1257/pol.20120383

International IDEA (2021). Global Overview of COVID-19 Impact on Elections. Available at: https://www.idea.int/news-media/multimedia-reports/global-overview-covid-19-impact-elections (Accessed March 24, 2021).

James, T. S. (2021). New development: Running elections during a pandemic. Public Money Manag. 41 (1), 65–68. doi:10.1080/09540962.2020.1783084

James, T. S., and Garnett, H. A. (2020). Introduction: The Case for Inclusive Voting Practices. Pol. Stud. 41 (2–3), 113–130. doi:10.1080/01442872.2019.1694657

Jäske, M. (2017). ‘Soft’ Forms of Direct Democracy: Explaining the Occurrence of Referendum Motions and Advisory Referendums in Finnish Local Government. Swiss Polit. Sci. Rev. 23 (1), 50–76. doi:10.1111/spsr.12238

Krimmer, R., Duenas-Cid, D., and Krivonosova, I. (2021). Debate: Safeguarding Democracy during Pandemics. Social Distancing, Postal, or Internet Voting-The Good, the Bad or the Ugly? Public Money Manage. 41 (1), 8–10. doi:10.1080/09540962.2020.1766222

Lahtinen, H., Martikainen, P., Mattila, M., Wass, H., and Rapeli, L. (2019). Do surveys Overestimate or Underestimate Socioeconomic Differences in Voter Turnout? Evidence from Administrative Registers. Public Opin. Q. 83 (2), 363–385. doi:10.1093/poq/nfz022

Luechinger, S., Rosinger, M., and Stutzer, A. (2007). The Impact of Postal Voting on Participation: Evidence for Switzerland. Swiss Polit. Sci. Rev. 13 (2), 167–202. doi:10.1002/j.1662-6370.2007.tb00075.x

Laki kansanedustajain vaaleista (1969). 391/1969. Available at: https://finlex.fi/fi/laki/alkup/1969/19690391 (Accessed March 24, 2021).

Laki kansanedustajain vaaleista annetun lain muuttamisesta (1985). 370/1985. Available at: https://finlex.fi/fi/laki/alkup/1985/19850370 (Accessed March 24, 2021).

Laki neuvoa-antavissa kunnallisissa kansanäänestyksissä noudatettavasta menettelystä (1990). 656/1990. Available at: https://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/alkup/1990/19900656 (Accessed March 16, 2021).

Laki vaalilain muuttamisesta (2010). 431/2010. Available at: https://finlex.fi/fi/laki/alkup/2010/20100431 (Accessed March 24, 2021).

Laki vaalilain muuttamisesta (2017). 939/2017. Available at: https://finlex.fi/fi/laki/alkup/2017/20170939 (Accessed March 24, 2021).

Nemčok, M., and Peltoniemi, J. (2021). Distance and Trust: Examination of the Two Opposing Factors Impacting Adoption of Postal Voting Among Citizens Living Abroad. Polit. Behav. doi:10.1007/s11109-021-09709-7

Norris, P. (2019). Do perceptions of Electoral Malpractice Undermine Democratic Satisfaction? the US in Comparative Perspective. Int. Polit. Sci. Rev. 40 (1), 5–22. doi:10.1177/0192512118806783

Norris, P. (2004). Electoral Engineering: Voting Rules and Political Behavior. New York: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511790980

Oikeusministeriö (2019). Kunnalliset kansanäänestykset (14.10.2019). Available at: https://vaalit.fi/kunnallinen-kansanaanestys (Accessed March 24, 2021).

Oikeusministeriö (2021). Muistio kuntavaalien järjestämisestä Covid-19 pandemian aikana 6.3.2021. Available at: https://valtioneuvosto.fi/-/1410853/kuntavaalit-siirtyvat-kesakuulle (Accessed March 24, 2021).

Peltoniemi, J. (2018a). Transnational Political Engagement and emigrant Voting. J. Contemp. Eur. Stud. 26 (4), 392–410. doi:10.1080/14782804.2018.1515727

Peltoniemi, J. (2018b). On the Borderlines of Voting: Finnish Emigrants’ Transnational Identities and Political Participation. Acta Universitatis Tamperensis 2403. Tampere: University of Tampere.

Peltoniemi, J., Wass, H., and Weide, M. (2020). “Kotini on vaalikoppini. Joustavien äänestysmuotojen merkitys yhdenvertaiselle poliittiselle osallistumiselle,” in Politiikan ilmastonmuutos. Vaalitutkimus 2019. Editors S. Borg, E. Kestilä-Kekkonen, and H. Wass (Helsinki: Oikeusministeriö), 334–363.

Pesonen, P., Sänkiaho, R., and Borg, S. (1993). Vaalikansan äänivalta. Tutkimus eduskuntavaaleista ja valitsijakunnasta Suomen poliittisessa järjestelmässä. Helsinki: WSOY.

Santana, A., Rama, J., and Bértoa, F. C. (2020). The Coronavirus Pandemic and Voter Turnout: Addressing the Impact of Covid-19 on Electoral Participation. Online working paper. doi:10.31235/osf.io/3d4ny

Suomi-Seura (2019). Ulkosuomalaisten ensimmäiset kirjeäänestysvaalit: äänestysaktiivisuus nousi ennätyskorkealle. Tiedote 16.4.2019, 13:30. Available at: https://www.epressi.com/tiedotteet/ulkomaat/ulkosuomalaisten-ensimmaiset-kirjeaanestysvaalit-aanestysaktiivisuus-nousi-ennatyskorkealle.html (Accessed 3 22, 2021).

Tarasti, L. (1987). “Äänioikeuden ja sen käytön muutoksista,” in Kansanedustajain vaalit Riksdagsmannavalet 1987 (Helsinki: Statistics Finland), 18–32.

Tokaji, D. P., and Colker, R. (2007). Absentee Voting by People with Disabilities: Promoting Access and Integrity. McGeorge L. Rev. 38, 1015–1064.

Vaalilaki (1998). 714/1998. Available at: https://finlex.fi/fi/laki/alkup/1998/19980714 (Accessed March 18, 2021).

Valiokunnan mietintö (2017). Valiokunnan mietintö PeVM 3/2017 vp - HE 101/2017 vp. Available at: https://www.eduskunta.fi/FI/vaski/Mietinto/Sivut/PeVM_3+2017.aspx (Accessed March 24, 2021).

Valiokunnan mietintö (2021). Valiokunnan mietintö PeVM 4/2021 vp - HE 33/2021 vp. https://www.eduskunta.fi/FI/vaski/Mietinto/Sivut/PeVM_4+2021.aspx (Accessed June 24, 2021).

Wass, H., and Borg, S. (2012). “Äänestäminen, liikkuvuus ja puolueiden erot,” in Muutosvaalit 2011. Editor S. Borg (Helsinki: oikeusministeriö), 97–115.

Wass, H., Mattila, M., Rapeli, L., and Söderlund, P. (2017). Voting while Ailing? the Effect of Voter Facilitation Instruments on Health-Related Differences in Turnout. J. Elections, Public Opin. Parties 27 (4), 503–522. doi:10.1080/17457289.2017.1280500

Keywords: pandemic elections, postponing elections, electoral reform, voter facilitation, convenience voting, postal voting, external voters, non-resident citizens

Citation: Wass H, Peltoniemi J, Weide M and Nemčok M (2021) Signed, Sealed, and Delivered with Trust: Non-Resident Citizens’ Experiences of Newly Adopted Postal Voting. Front. Polit. Sci. 3:692396. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.692396

Received: 08 April 2021; Accepted: 30 June 2021;

Published: 06 August 2021.

Edited by:

Peter Loewen, University of Toronto, CanadaReviewed by:

Jill Sheppard, Australian National University, AustraliaCopyright © 2021 Wass, Peltoniemi, Weide and Nemčok. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hanna Wass, aGFubmEud2Fzc0BoZWxzaW5raS5maQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.