95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci. , 12 October 2021

Sec. Comparative Governance

Volume 3 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2021.689614

This article is part of the Research Topic "Performing Control" of the Covid-19 Crisis View all 12 articles

This article discusses discursive transformations in the performance of the government and the “hashtag landscape,” studying Twitter discussions and the female-led government of one of the youngest Prime Ministers in the world, Sanna Marin of Finland. Among the countries in Europe, Finland has been, in the period of analysis of March 2020 to January 2021, one of the least affected countries by the COVID-19 pandemic. Our datasets from both Twitter discussions and the government’s press conferences in 2020 reveal which were the emerging topics of the pandemic year in Finland and how they were discussed. We observe a move from consensual governmental political control to control in the hands of the authorities and ministers responsible, performing a different basis for the pandemic. On the “hashtag landscape,” facemasks continually emerge as an object of debate, and they also become a point of trust and distrust that the government cannot ignore. In terms of comparative governance, this article also notes how the emergency powers legislation shifted control to the government from regional authorities and municipalities in spring 2020, and by that autumn, those powers were returned to regional and local bodies. We recognize several themes that were contested and the discursive field’s transformations and interplay with the authorities.

This article investigates the performance of control in press conferences and in Twitter discussions related to COVID-19, in a country that survived the pandemic well in 2020. The female-led government of the young social democratic Prime Minister Sanna Marin was faced with a historic challenge merely months after its appointment in 2019 (Palonen 2020) but also online harassment (Van Sant et al., 2021). Control in pandemic politics is a paradox. It is impossible to be in control of a border-crossing, air-transmitting virus. Similarly, it is impossible to be in control of politics in a democracy. Political communication and commentary on Twitter are constitutively performative acts. The government and authorities appear as if they were in control and convincing the people of their pandemic measures relying on expert advice and leadership. In their seminal work on government communication, Sanders and Canel (2013, 331) wrote “window-dressing exercises to give the appearance of open government communication,” which we find crucial when considering the performativity control. From a post-foundational perspective, we do not take leadership for granted, but the task of politics is to fill the ultimately empty space of power (Laclau 2014; see Palonen 2021).

The numbers of COVID-19 cases in Finland in 2020 were contained: the state of emergency, social distancing, and other lockdown acts resulted in fewer hospitalized cases caused by other respiratory infections and shrunk the RSV and influenza seasons (Kuitunen et al., 2020). To discuss ethical approaches by different governments, Häyry (2021, 43) identified four main approaches for dealing with the pandemic. The first, containing and mitigating the disease, chosen in many countries, would “flatten the curve,” to enable healthcare systems to be better prepared to provide effective care. In spring 2020, the virus was spreading in the Helsinki metropolitan region, and foreign travel was restricted. In an exceptionally warm year, many from south Finland had planned to travel north to enjoy the record amounts of snow or to go to their vacation homes, but the government decided to use emergency powers legislation to ensure containment of the virus in the region. It ordered a lockdown and regional closure of the metropolitan Uusimaa region, with police and the Finnish Defense Forces in place to restrict unnecessary border-crossing from 18 March to 14 April, covering the Easter holiday break (Willberg et al., 2021). In contrast, in Sweden, and especially those from the capital Stockholm region, people traveled to the Alps for their winter holidays: the virus was already rampant in Sweden when the state epidemiologist opted for the second “herd immunity” approach. In May, Finland, like Germany and others, adopted the third approach, “a test, track, isolate, and treat model to manage and control the pandemic” (Häyry 2021, 46; emphasis original), to keep down virus reproduction (RE) through measures that minimize infection rates and identify spread, loosening some, and imposing other lockdown measures. Sometimes suppression, the fourth approach, was also mentioned in Finland. Singling out “control” is important for our argument and research question of how the government performed pandemic control and how was it received and contested. Häyry (2021, 43–44) points out that the government managed to express its recommendations in such a way that they were interpreted as legislation by citizens. For us, this points to performative control.

The Nordic expectation of openness also has demanded transparency of governance, but in practice, the demand for transparency is meant only superficially (Erkkilä 2012). Government communication includes ceremonial elements, and it is disconnected from the policy itself (Vesa 2015). Finns generally trust their authorities and argue Kääriäinen, Isotalus and Thomassen (2016). The question of speaking the truth or lying emerges as pivotal in the Finnish “mask gate” debate of autumn 2020, when the issue of masks, as it was argued in the spring by the government, was negated. Considering healthcare crisis leadership from an ethical communication point of view, Häyry (2021, 47) argued that the Swedish government, in its outspoken heard immunity policy, was more truthful than the Finnish one but that historical circumstances in Sweden allowed for that better than in Finland and other countries where legitimacy for the situation was sought differently. The government and the health authorities articulated or performed their statehood (Palonen 2018; Vulović, 2020) and their control of the virus. When discussing March 2020, Moisio (2020, 600) captures the turn to the nation states and highlights minuscule resistance in Finland, citizens complying with the requirements of a newly performed bordered history-aware state entity.

The existing literature notes the pandemic’s effects on democracy in Finland. The pandemic brought centrism to the policy process of network governance in Finland (Neuvonen 2020). Another approach stressed co-creating and sharing ideas, including new forms of knowledge production in the “post-liberal” Finnish case, “with a readiness to share its sovereignty in decision-making with experts and activate participation of healthcare workers, parents, teachers, local authorities, and, finally, children themselves” (Makarychev and Romatshko (2021, 80, 73). Indeed, the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare (THL), the main body advising the pandemic strategy in Finland, gathered 116 social media posts prior to the first press conference on 27 February, “to analyze risk perceptions and trust towards public authorities in the context of coronavirus disease,” recognized five central types of risk perceptions, and proposed answers to them: catastrophic potential, probability of death, reasons of exposure, belief of controllability, and trust in authorities (Lohiniva et al., 2020). This legitimized our research design: the communicating authorities that we studied also followed Twitter discussions.

Twitter enabled the Finnish close-knit virtual elites to perform their “politics of presence,” Ruoho and Kuusipalo (2019, 81) argue that “the myth of the mediated center seems to persuade politicians and journalists from all levels of society to join a special kind of Twitter network dominated by the “inner circle” of top-level political and media elites.” The interplay between the elected officials and the expert organizations and authorities is also visible in our data. We study the authorities and the debating “hashtag publics” (Rambukkana 2015), the co-occurrence and ministerial presence of government press conferences, and social media discussions, through interpretative analysis of the themes of communication and contestation. Existing research explores forms of government criticism or interaction on COVID-19 on Twitter (between two approaches in Finland: Väliverronen et al., 2020; overall topic modelling analysis of Spring 2020; Agarwal et al., 2020 and Doogan et al., 2020). Existing research has also demonstrated that female politicians, including the Finnish Prime Minister, face harassment online, as NATO Strategic Communications Centre for Excellence’s study unveils (Van Sant et al., 2021). Our data, as well, unveil critical points to assess also of gender and misogyny as constitutive antagonism in Twitter discussions.

We agree with Lindgren (2020) that data science requires some anarchism and that open-ended discourse theory fits with cracking large datasets. We were forced to be creative, mapping the pandemic’s transformation through a longitudinal analysis. Our period of investigation, 11 January 2020 to 11 January 2021, stretches from before the virus officially arrived in Finland to the first sets of vaccinations.

Recognizing the constitutive power of rhetoric in articulation (Laclau 2014), we merged two types of performative data. Government by appearing in press conferences takes the space of representation becoming the faces of control and the social media response performs citizenship, sometimes critical of the authorities, contesting their role and policies as the non-homogeneous hashtag public. Developing on Laclau and Mouffe’s (1985) Essex School of post-structuralist discourse theory, for us meanings are relational and transform the discursive field, where structures of meaning are contingent and antagonist rather than smooth. Research offers snapshots of this transforming discursive field, which is difficult to capture. Our interpretive, non-essentialist, post-foundational approach focuses on relationality, drawing on large social media datasets. Therefore, our methodological key research question is as follows: how can we study the contingent structures of the uneven, contested discursive field and see how control is performed and contested through interventions during the pandemic?

Our methodological solution was to combine topic instrumentalism with rhetoric-performative interpretive analysis (Palonen 2019; Pääkkönen and Ylikoski 2020). More sophisticated analytical tools have been called for Laclaudian discourse theory (Marttila 2019), and we enhance post-Laclaudian approaches with an interpretive take on LDA topic modelling also going beyond a search of “nodal points” (Isoaho et al. 2019), to addressing temporal transformation through “floating signifiers.” This resulted in a novel way of analyzing two diverse types of data, present in our rich section on analysis and in the multiple annexes, which we present in depth. We hope it adds to other strategies of studying hegemony discursively through topic modelling (Jacobs and Tschötschel 2019).

Borrowing from both Rambukkana’s “hashtag publics” and from the discursive field of Laclau and Mouffe (1985), we developed the term “hashtag landscape” for Twitter discussions as traced by hashtags and keywords. Rambukkana’s notion focuses on contingent community-building and eventness, which we consider important in this process. COVID-19 was an event that became a “social imaginary,” a constant reference point, while at the same time debate over policy continued. When the hashtags are universalized and hence stopped being meaningful or used as a hashtag, the keyword and replacement hashtags offered a snapshot of the discursive field in the social media. Our term “hashtag landscape” captures how, just as the discursive field, the social media landscape is crisscrossed with antagonisms. It allows us to go beyond observing meanings produced by accounts or actants (which drawing on Latourian network theory Rambukkana considers hashtags), still retrievable within the gathered data. The transformation of the debates can be investigated on an aggregated and thematic level, beyond studying key individuals, politicians, or agencies in detail. Hashtag landscape would capture shifts, ruptures, and social imaginaries on the discursive field.

Controlling the pandemic caused by COVID-19 has little to do directly with the performance of control through the presence and absence of ministers or Twitter discussions. However, from our perspective, uncovering the interaction between shifts in being the faces of authority or embodying the place of power in press conferences, on the one hand, and debating this in the public forum, on the other hand, are significant in exploring contemporary mediated governance. Uncovering shifts in policy themes and debates, ministerial relationships, and who appears to be in control gives input to research network governance. Mapping debates and criticism in contemporary debates on Twitter highlights the rhetorical and performative side of politics (Laclau 2014; Moffitt 2016). Our further research contribution highlights the online presence of politicians and administrators and their political communication in hybrid media environments. Our reading of the authorities’ political communication and public social media discussion enhances the study of not only the pandemic in Finland but also contemporary politics that relies on constitutive public performativity (Palonen 2021).

Three different Twitter datasets with an analysis of the Finnish government’s videoed press conferences serve as samples of contemporary public discussions (Twitter) and government communication (press conferences). We interpret them through discourse analysis and making use of machine learning. Topic modelling is a useful tool for interpretive analysis: the first layer of interpretation is done by the machine, which then proposes sets of related terms in the data to the researcher to analyze and interpret further. Following discourse theory, these data samples enable discursive structures to be found (Lindgren 2020). Our data-driven research relies on readings of both sets of materials qualitatively and is assisted by machine-learning, but the existing literature already presents a central problematization: the role of the government in COVID-19 communication. The analysis reveals the key points for each period and follows their transformation through press conferences and peaking topics’ tweets.

The government’s pandemic communication concentrated on regular press conferences that aimed to address citizens’ concerns and communicate government actions and later health information on the pandemic. They were widely followed via both the online service of national broadcaster YLE and YouTube, and the pandemic increased TV watching by 21 percent in MarchApril 2020. News and related program watching on TV doubled with the government’s press conferences on 25 March and 4 May, and the news on 12, 16, and 30 March and 4 April were among the 20 most popular programs in 2020 (Finnpanel 2021). For our analysis, we followed who was present, what was talked about, and the visual illustrations that highlighted the mood and transformation of events, including the use of facemasks from only 8 October. Full-scale visual analysis falls out of the scope of our study. Our data reveal that Twitter discussion topics often peaked synchronously with the government’s press conferences. In the timeframe of our analysis (Table 1), the first period saw the transformation of COVID-19 as a Finnish issue in the government’s daily press conferences from 16 March 2020. The second period covers the first wave of COVID-19 in Finland, as pandemic restrictions were underway and control of the situation was established, including the closure of the Uusimaa region, and confirmed COVID-19 cases declined from over 600 per week to 200 per week. In June, cases reduced to circa 50 per week. The relaxing of regulations was an issue in June in press conferences, which we also included in this analysis, and travel restrictions and the EU package were discussed in July. Our third period starts at the return to work from school summer holidays and again at the end of the festive season in January. This period also witnessed the beginning of vaccinations and the start of the discussion on their availability.

The first two sets were gathered by web search on Mecodify with specific hashtags and keywords (see Annex 12). In early spring 2020, hashtags were used in discussions to signal addressing the pandemic as an issue, and we chose to focus on tweets signaling contribution to general discussions and even generating “hashtag publics” (Bruns and Burgess 2015; Rathnayake and Suthers 2018). In the second period, hashtag use was declining (see Annex 13). It signaled the hegemonic presence of the pandemic in Twitter users’ lives; using the hashtag would single out a contribution to public debate, but in the all-pervasive pandemic condition, using a hashtag would not make sense. The volumes of the first two gathered datasets had fewer tweets than they would have had with keywords, which we applied for the third set for the above-mentioned reason (McKelvey, DiGarzia and Rojas 2014). The urgency of the pandemic faded as the country survived the first wave and attention turned to the government’s pandemic choices.

To analyze the large Twitter datasets, we apply computational topic modelling, a computational method used to identify a pre-determined number (k-number) of topics or clusters in textual big data. We use the common topic modelling method Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) (Blei et al., 2003). LDA topic modelling arranges words to a predefined number of topics via the co-occurrence of the words in the data. It assumes that each data unit, here a tweet, is a mixture of topics, and the algorithm calculates a probability for each tweet and each topic. Previous research (Wilkerson and Casas, 2017) of topic modelling has shown the instability of the results and of reliably validating the results (e.g., Grimmer and Stewart, 2013). To counter this instability, we validate the topic modelling results using the actual tweets. Our approach corresponds to the topic of instrumentalism, where “modelling is not taken to measure theoretical constructs but instead to provide information about word patterns, which can be usefully employed to guide subsequent interpretation of the primary text materials” (Pääkkönen and Ylikoski, 2019).

We conducted two topic modelling analyses for each of the three sets. The first analysis was a “small-k” analysis with an arbitrary six-topic model, to get an overview of the contents of each dataset. The second analysis was a detailed “large-k” analysis, where the number of topics for each set was based on an estimated optimal number. Next, we established topic timelines which were calculated by counting tweets per day for each topic. For the “small-k” overview model, we did the timelines for all six topics per dataset. For the “large-k” detailed modelling, we did timelines for the 20 most occurring topics. We examined the topics of both the “small-k” and “large-k” analysis of each three datasets and the set of 100 most probable tweets related to each topic. Based on this, we formed a general interpretation of each topic/tweet, and then, we selected the topics/tweets that were related to the performance of control for closer investigation. More details of the topic modelling can be found in Annex 11.

From the perspective of post-structuralist or post-foundational discourse theory, a form of interpretive political science (Bevir 2010), topic modelling offered us a machine-learning perspective to transforming for structures of the discursive field. Instead of discussing Twitter handles here, we operate on an aggregate level, enabled by our take on the continuously transforming “hashtag landscape.” Contingency, flows, and contestation are crucial to our approach: while research on topic modelling typically lists keywords for the whole period, we also provide a timeline of activity for each topic and compare the transforming salience (peaks highlighted here) of a particular topic. Besides discussing first six topics on a more macro level, in more detailed and qualitative analysis, we go through a larger set of topics and topic-associated tweets. For us listing topics is not enough: scratching the surface unveils that each topic can include several even seemingly contradictory themes to interpret. Qualitative analysis allows us to investigate individual tweets at key moments for understanding what the topics are about. The contents of the topics can be diverse, and, besides recognizing the intensity of tweeting within topics, discursive reading of topic modelling also includes analysis of the tweets across time within the topic (see, e.g., Figure 1). As the timeline for each of the period, we pursue thematic macro-level analysis with ministers as key signifiers. This resulted in a lengthy analysis, but for this experimental study, we thought of writing it out.

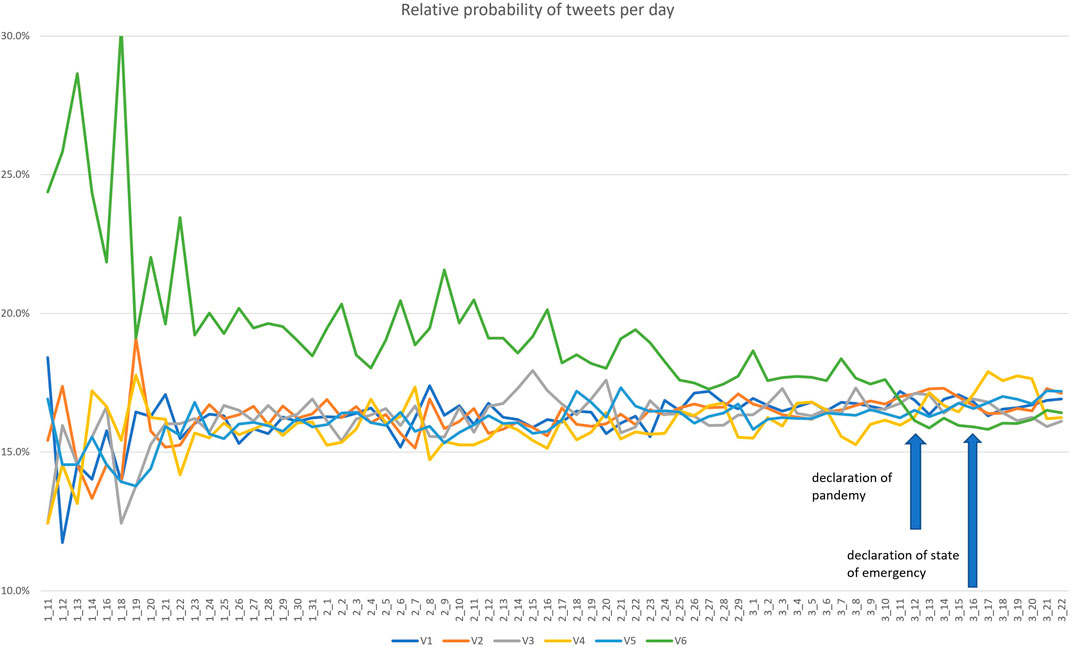

FIGURE 1. The first period’s overview of the topics: the average relative probability of tweets per day in the 6-day model. Note, there were only one to two tweets per day before 20 January 2020.

Dividing the period into three periods, we were able to see the particularities of these historical moments and track some returning debates. We are interested in the contents of those discussions, their spikes, and their relative strength within the periods. In the first period, each of the press conferences was led by PM Marin, starting from 27 February. In the second period, there were different sets of responsible ministers involved, but most press conferences were led by ministers—by elected officials rather than bureaucrats—in the period from 20 March to 27 May. During summer (June and July), six of the seven press conferences were led by ministers: out of those, only two took place in July; one of them was led by PM Sanna Marin on the EU package. We left this out of the study as the pandemic was not much debated at that time, but it started again in August and with vaccinations starting after Christmas. The third period saw increased criticism of the government and responses that seemingly satisfied the hashtag publics.

The first period covers the turning of COVID-19 from an international into a Finnish topic. The first dataset spans from 11 January to 22 March 2020, thus covering the beginning of COVID-19 in Finland. COVID-19 became highly debated through the hashtags we followed for this period, particularly with and after the declaration of the pandemic. The buzz on Finnish Twitter started at the declaration of the pandemic on 11 March (see Annex 13 for tweets per day in the first period).

Of the six macro topics (see Annex 2 for topics and Annex 5 for individual figures, and Figure 2), topic on the government, the PM, and on people following government instructions (T1) includes both criticism towards the government and the selected corona strategy, and tweets supporting the government and its corona strategy. Topic two gathers sentence structures, but the tweets and discussions related to T2 share their experiences and feelings related to the pandemic. Topic on schools, travels, and quarantine (T3) also includes cancellations of travel arrangements and restrictions to public amenities. Topic on working and entrepreneurship as well as guidelines, public communication, and information (T4) unveil information related to COVID-19 to entrepreneurs, entrepreneur interest group requests of support towards government, and press releases of employer and employee unions about the pandemic and work. Topic on the politics of the COVID-19 crisis, sustainability, government, and state of the exception (T5) includes tweets about general discussion related to the crisis, politics, state of emergency, and the economy. Topic on the situation and spread of COVID-19 in China, Italy, and Finland (T6, see Figure 3) demonstrates the transformation of foreign epidemy into a pandemic and domestic issue.

We observed a transformation between the strengths of the different topics, and, as Figure 3 demonstrates, how and when the pandemic and the Finnish state of emergency were declared; other topics overtook the relative importance of the international spreading of the virus (T6). To explore in more depth through multiple topics and matching the dates of the governmental press conferences on COVID-19, we worked on a larger list of topics (175 for the same period, Figure 2).

We grouped these 20 topics into five groups according to the tweets that they refer to. The first group is a general discussion related to COVID-19, which includes mainly private persons discussing different aspects of COVID-19 (G1); second is related to organizations and discussions about organizational announcements (G2); third is related to government and official announcements about the COVID-19 situation, and discussions about these announcements (G3); fourth is about news about COVID-19, and the discussion related to the news (G4); fifth is related to both critical and supportive discussions about the government and official response to the COVID-19 situation (G5) (see Annex 8 for details). Topic peaks and government press conferences are shown in Table 2.

To reflect on the discursive transformation within a topic that gathers similar types of tweets, we chose the topic on closures (G3: T47), where the emergence of the phenomenon was discussed in China first, then in Italy, and finally, in Finland (Figure 3). It couples with our earlier analysis of how it was felt increasingly as a European and potentially Finnish issue and then as a Finnish issue. As with the six-topic model, the trend emerging on 24 February is that the international topic was overtaken by domestic issues this week with the declaration of the pandemic.

The few tweets in the first phase in this period, 11 January to 24 February, focus on the pandemic in other countries (see Figure 3). Notably, the recorded numbers of cases of COVID-19 were very few in Finland. The first case was diagnosed in the north of the country, Lapland, on 29 January. By the week including 27 February, it reached 7 cases, and the week after 34 cases. Furthermore, people were tested only if a link to COVID-19 was found; by 17 February, one could be tested only with respiratory infection symptoms and a link to China (THL 2020a). By 25 February, the list of countries to test for COVID-19 predeparture was extended to Iran, South Korea, and parts of Italy (THL 2020b). Tweet activity demonstrated pressure on the government to communicate although numbers in the native tweet hashtags we gathered were still low.

The major Twitter discussions relating to COVID-19 in Finland began on 24 to 27 February, before the government’s first COVID-19 press conference on 27 February (Figure 2). None of the topics that already existed or appeared between 24 and 27 February disappeared before the end of our study period. After 24 to 27 February, COVID-19 became something felt also in Finland. Tweets related to all groups peaked on 27 February, the day of the first government press conference. Of these, T146 relates to direct and often critical references towards the government or official tweets discussing or questioning the government and officials’ preparedness to deal with the then upcoming pandemic.

The government press conference on COVID-19 on 27 February was defined by increased Twitter discussions. While cases were not emerging due to the restricted testing, the worsening of the situation globally paved the way for the 27 February conference, on the topic of the status of COVID-19 and related preparations in Finland. Four of the five government parties were represented, with Prime Minister Sanna Marin (Social Democratic Party, SDP), responsible Minister Anna-Kaisa Pekonen (Left Alliance), and Ministers Krista Kiuru (SDP) and Katri Kulmuni (Centre). Marin stated that there was no epidemic in Finland. Pekonen stressed the responsibility of her ministery: they would be active and vigilant, and Finland had good preparedness. She argued that the masks in the country’s stockpiles, discovered to be beyond their expiry date, could be used.

From 11 March to 16 March, extremely high activity was recorded in Twitter related to COVID-19. The landslide in Twitter commentary happened with the declaration of the pandemic on 11 March, with cases of COVID-19 going from 61 that day to beyond 100 the next. All discussions in all groups peaked on the pandemic declaration and press conference day of 12 March (see Table 2). The government decided on the pandemic measures proposed to the parliament to decide on. All three G5 topics peaked on 12 March: in T146 and T152, tweets criticized the government for not enacting strict COVID-19 restrictions, a lack of leadership from the government, and the government not taking the COVID-19 situation seriously enough. The more radical tweets claimed that the seemingly inactive government would “have blood in their hands.” The THL was also criticized for being incompetent and for giving the government false advice to act upon. In T118, tweets also praised the President of Finland Sauli Niinistö’s (National Coalition) speech on the same day. On Thursday, 12 March, the second government press conference about the COVID-19 situation was held to outline recommendations to limit the spread of COVID-19 in Finland, including recommendations to limit attendance of public events, additional budgetary means, recommendations to workplaces, and preparations in social and healthcare. The government parties had met on the matter and invited all parliamentary parties to discuss options, which included school closures. The PM opened the discussion, and Pekonen took responsibility again, with Kiuru’s and Kulmuni’s support. With or without the press conference, the declaration of the pandemic was a tone changer: it would be affecting ever more people.

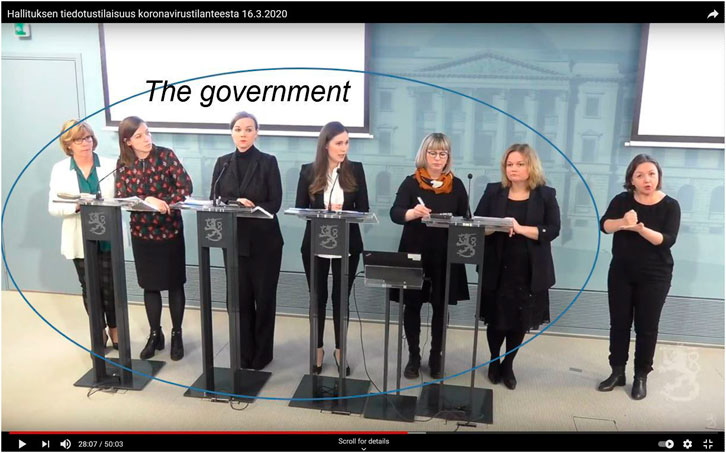

The Twitter discussions seemed to retreat on most topics after their zenith for the weekend 13 to 15 March (Figure 2) but peaked again on 16 March, when the government announced in a press conference to state in cooperation with the President that the country was in a state of emergency. The momentous press conference urged citizens that “every Finn can make a difference” maintaining distances and staying at home and declared preparedness to adapt crisis legislation. Several measures were to be taken, and those over 70 were declared as a vulnerable group. Interestingly, it was phrased that other age groups could take on this virus, but there was a need to protect elderly people. The emergency measures included distance work, travel restrictions, and closure of museums and theatres. Teaching would be moved online, but schools and day-care facilities would serve onsite children on the lower grades of key workers and those not in distance work. The female-led government was present, apart from the Greens, including Minister of Justice and party leader Anna-Maja Hendriksson (Swedish People’s Party) and the Minister of Education and party leader Li Andersson (Left Alliance) (see Figure 4). They emphasized that the recommendation to distance work did not imply an end to transportable work or teaching. Finland, as a hi-tech country, had good telecommunications across the country: many schools provided tools for distance learning, and workplaces already had portable phones and laptops.

FIGURE 4. In the picture from 16 March, the Finnish Ministers and party leaders, apart from Minister of Interior, Maria Ohisalo (Green League). The sign language interpreter is in the picture. (Modified video screenshot.)

Unsurprisingly, several topic discussions peaked on 16 March (see Table 2). In the critical and supportive discussions about the government and official response to the COVID-19 situation (G5), the tweets related to the topic T146 are quite critical of the government in the early part of the day. The government was criticized for being too inactive and not showing leadership and was said to be incompetent. The tone of tweets in T146 changed after the press conference. Most of them supported the government’s decisive action and the leadership shown by the government, PM Marin, and the President. Similar reactions appeared in T152 and T118. Some tweeters criticized the government’s perceived herd immunity strategy. Comments could be dismissive of the government, echoing misogynist rhetoric, and supportive of President’s leadership.

The last phase of the first period spanning from 17 March to 22 March was defined by slightly receding Twitter discussions. The government was holding daily press conferences to introduce measures on COVID-19 control and to remind the population of their civic responsibility. On 17 March, six ministers from all parties but the Centre addressed in the press conference border control, 14-day quarantines, and limiting meetings to 10 people. The PM was joined by the Green party leader, Minister of the Interior Maria Ohisalo; Minister of Foreign Affairs Pekka Haavisto (Greens); Minister of Transport Timo Harakka (SDP); and Ministers Hendriksson and Pekonen. Co-occurring with the 17 March press conference, there were some organizational and governmental announcement peaks (Table 2). After peaking on 16 March, the critical and supportive discussions (G5) declined, but the critique towards the government and THL persisted. In the “hashtag landscape,” the government received criticism for being indecisive and lacking leadership and the THL for being incompetent. Some tweets praised the President for clear leadership in a situation where government appeared chaotic. Few tweeters voiced doubts over the need for a state of emergency and its violation of individuals’ rights.

On 18 March, the PM was joined by Minister Andersson and Minister of Culture, Science and Sports Hanna Kosonen (Centre). The day-care facilities would remain open, but it was recommended that children of those who could stay at home would remain at home. Children under 10 yr of age of critical workers would be able to stay in school. On the same day, general discussion of some G1-3 topics peaked. On 19 March, practicalities of the pandemic, details of the virus, hygienic practices, and details of reaching help and healthcare capacity were discussed in the conference, under the leadership of the PM, and Ministers Kulmuni and Pekonen. Notably, the Director of Infectious Diseases, Professor Mika Salminen of THL, joined the event for an epidemiological overview, which then became a regular feature of the press conferences. On the same day, other topics (G1-4), but not the critical and supportive topics, peaked.

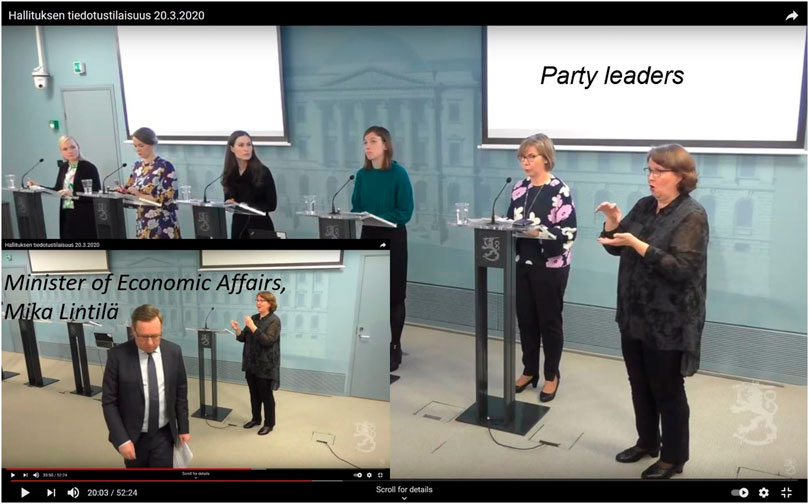

The first of four all-government parties’ press conferences ended the week on 20 March and delivered a unified message to citizens, following a narrative structure where each minister’s delivery followed from the previous minister’s last point, presenting a unified message. The press conference dealt with the economy and the amending budget, with provisions for diverse groups. Leaders of each of the government parties divided the task of explaining the measures, often focusing on issues related to their core voters. In addition to the PM, present were Kulmuni, Hendriksson, Andersson, and Ohisalo (Figure 5). Mika Lintilä, the Minister of Economic Affairs, presented the substance. We chose two screenshots to present the event, where G1-2 and G4 topics peaked.

FIGURE 5. Juxtaposition: After party leaders, Maria Ohisalo (Green League), Katri Kulmuni (Centre), Sanna Marin (SDP), Li Andersson (Left Alliance), and Anna-Maja Hendriksson (Swedish People’s Party) stressed the case, Minister Mika Lintilä (Centre) went to substance. The sign language interpreters are in the picture (modified video screenshot).

From 27 February to 20 March, period one, the conferences were all-female panels, and the PM started each of the press conferences followed by responsible ministers. Figure 5 shows what a female-led government looked like on 20 March and how Lintilä, as Minister responsible, presented on his own. Compared with the first photos on 16 March, when the phenomenon was hitting Finland and responsible ministers crammed into the view (Figure 5), by the formal address on 20 March, safety distances were in use. The topic was indeed survival of the industry and the additional budgets, demonstrating being in control of the livelihoods of the citizens in several categories. The next period would witness firmer actions, with the government taking measures to control the epidemiological situation.

The second period saw some momentous government decisions on restrictions and then the lifting of restrictions, heavily tweeted about. The second dataset spans from 21 March to 26 May 2020. The government claimed political responsibility for the pandemic measures, and authority over the President’s advice, but increasingly, it gave space to experts and the administration. As Figure 1 shows, the discussion was thriving on Twitter in the beginning and quieting down by the end of our second period although there were some relevant press conferences on masks after 26 May. In the six-topic model, news and discussions related to the COVID-19 situation (T1, focused on the situation in Finland, including the number of infected people and deaths, but also mentioning other countries) seemed to prevail its relevance. Government’s COVID-19 strategy and its implications for politics and the economy (T2, included tweets either critical towards or supportive of the government) peaked in key moments. General discussions about COVID-19 (T3, referred to discussions about the COVID-19 situation and how to deal with it, but also religious content and beliefs) were the least visible. General discussions about the COVID-19 situation and how it affected the everyday lives of people (T4, on stress, quarantines, and comments on other people’s behavior) were particularly high in the beginning. Information and support on COVID-19 offered to entrepreneurs and small-to-medium companies, or support reception, hardships, and challenges to companies (T5) were particularly relevant during and right after the Uusimaa closure. Discussion on schools and children, including general discussion about the COVID-19 situation and dealt with the opening of schools, May Day celebrations, and spring (T6) peaked on when school openings were announced. Six-topic model of the second period is shown in Figure 6 (see Annex 3 for topics and Annex 6 for individual figures).

Figure 7 (also see Annex 13) is based on our detailed topic modelling analysis with 200 topics in this period, where we show the distribution of the 20 most prominent topics per day and government press conferences. Peaks co-occur with press conferences and drop in weekends.

We divided the topics into five loose groups according to the themes of the topics, which are listed matching topic peaks with press conferences (see Table 3). The topic T26/G6 is considered here a technical topic and not included in our analysis (see Annex 9 for details). As seen in Figure 7, the general trend is that the discussions related to COVID-19 decreased during the second period. In late March, the most prominent topics had over 300 tweets per day, but during April, only one topic amounted to more than 200 tweets per day, except for 29 April. After 4 May, when the government declared it was re-opening society, the discussion frequency decreased. Considering the co-occurrence of the press conferences, and particularly G2 and G3 topics, we would argue that the press conferences were a significant part of the discussions of the pandemic in Finland in the hashtag landscapes.

At the beginning of this period, the government held press conferences daily. On 25 March, the PM and ministers from all-government parties—apart from the Left Alliance, whose leader had already been on stage on 23 March—announced 118 measures that would be taken to the parliament for decision-making. They grounded these on the capacity of health services: at that stage, every third person who had to be hospitalized would also be taken to intensive care. The measures included closure of the Uusimaa region, including the Helsinki metropolitan area, where it was hoped that the coronavirus could be contained. On 25 March, PM Marin and several ministers announced measures that would be taken to the parliament, as the government worried that the virus would spread to the rest of the country from the Uusimaa region. The announcement to restrict travel to and from the Uusimaa region co-occurred with a major spike in topic T109 related to the Uusimaa closure. The tweets of topic T109 on 25 March were mostly from private persons discussing distinct aspects of the planned Uusimaa closure. T109 peaked next on 28 March, which was the day when the closure was enforced. Both the announcement of the planned closure on 25 March and the enforcement of the closure on 28 March witnessed major related discussions in T109, more prominently after the announcement than after the actual closure. On 25 March, both G5 topics T52 and T99 peaked, with criticism on the role and actions of THL. Many tweets criticized THL for being too lenient about the pandemic, and stricter control mechanisms were needed. This criticism extended from THL to the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health (STM), Minister Pekonen, and the government. The government was also criticized for mishandling testing and for not securing incoming passengers’ safe entry through the Helsinki airport. Later, this same topic included tweets on facemasks.

In March, many of the topics peaked, coinciding with press conferences (Figure 7 and Table 3). We specify the peaks of different topics that coincide with conferences: 24 and 25 March were peak days of the week between 23 and 27 March, when daily press conferences were organized to prepare for the pandemic responses. On 30 March, when the second female-led government press conference was held on the extension of the measures until 13 May, 10 topics peaked. Restaurants would be closed for everything but take out. Schools would have distance learning from the fourth grade on and for most 1–3 grades, with a recommendation to also keep children at home from day-care facilities. The Uusimaa region’s closure for other than necessary travel would last until 19 April, including over the Easter holiday break. On 30 March, there was also a peak in G5 topics T52 and T99 criticizing the government for insufficient testing capacity, stating that the aim of the COVID-19 strategy should be to suppress the epidemy and to question THL’s non-recommendations on mask usage. The tweets referred to the letter sent by the President on 30 March to the government, where he suggested forming a specialist leadership group (“koronanyrkki”/“Corona fist”) to deal with Finland’s pandemic governance and criticized the government for turning the President’s suggestion down.

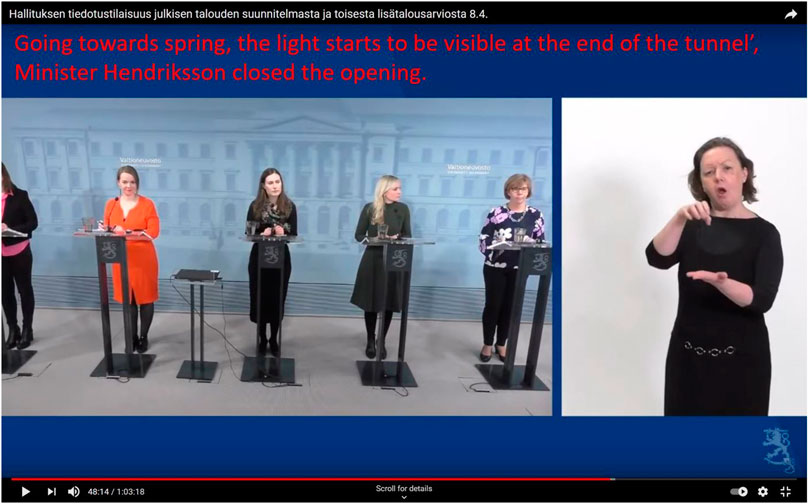

The week of 30 March to 3 April, press conferences took place daily again. On 8 April, Twitter lit up, when the third all-female government press conference addressed the worry of economic recession (see Figure 8). On several occasions, particularly at the government press conference on 8 April, where all parties were present, emphasis was on not repeating the mistakes of the economic recession of the 1990s in Finland, when the fall of the Soviet Union led to the undoing of favorable trade links with the Eastern neighbor. The signifier economic downturn represented a generational trauma: waves of bankruptcies and worsening municipal economies deeply affected families and schools when the millennial party leaders were growing up. In 2020, cheap loans were available, and the Eurozone was seen as sustaining the Finnish economy, and the Minister of Finance Kulmuni argued: “The municipalities are among the state’s most important partners in helping businesses and families.” Although Finland never entered a full lockdown in 2020, the government acknowledged that it suffered from the closures of particularly the service industry, and culture and arts, and sought to remedy them. The second press conference held on 8 April included only officials from responsible ministries and agencies (STM, NESA, TEM, and UM) to give answers to questions about protection equipment. This press conference co-occurred with a major spike in tweets related to topic T173 on insufficient preparation on protective equipment, or “maskigate” (“mask gate”). Interestingly, T173 peaks on 9 April, a day after a press conference responded to questions concerning the actions of the National Emergency Supply Agency (NESA), but this, in fact, may have strengthened the theme.

FIGURE 8. The five-party all-female leaders’ government on 8 April: Ministers and party leaders Andersson (Left Alliance), Kulmuni (Centre), Marin (SDP), Ohisalo (Green League), and Hendriksson (Swedish People’s Party) struggle to fit the same main picture, and now the sign language interpreter is in a separate picture (modified video screenshot).

The epidemiologic situation improved, and a week later, on 15 April, the Uusimaa region’s travel restriction was lifted. The virus had already spread beyond the Uusimaa borders, but the measures had lessened its movement, and from a constitutional perspective, the government could not maintain such restrictions on citizens’ liberties. The travel restriction zone had been controlled by the police with the help of the Finnish armed forces in multiple shifts, and it was also quite expensive, so lifting it would enable the police to have more resources to address domestic violence, which had been on the increase, as Minister Ohisalo stated on 15 April. The Uusimaa closure T109 peaked. On 16 April, the economy was discussed, and on 17 April, the President and CSOs appeared at Marin’s press conference on societal resilience, including representatives from CSOs such as the Finnish Red Cross and Mieli Mental Health Association. In the last week of April, there were a few topics peaking, with government press conferences on 22 and 24 April. On 22 April, Marin declared a new strategy for controlling the spread of the virus, with enhanced management of the pandemic, and stated that while public events would remain banned until the end of July, the reopening of schools would be announced before the end of the month. On 24 April, the Marin government organized a conference for children receiving a lot of positive attention in T91 and worldwide in the press. Children asked questions about the epidemic situation, including when they could go to school, and the vaccination would be ready (see Figure 9).

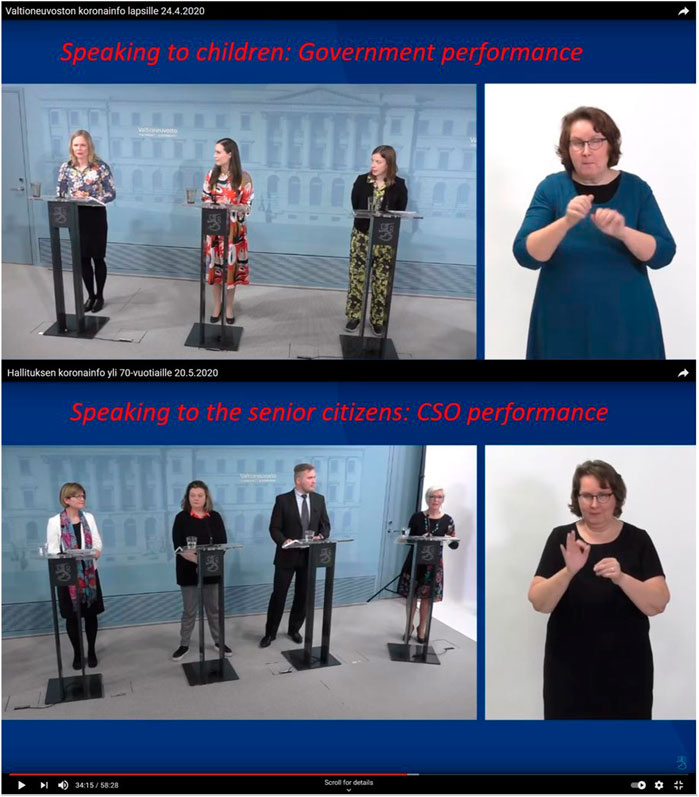

FIGURE 9. Juxtaposition: The government’s COVID-19 conference for children on 24 April included Minister Kosonen, PM Marin, and Minister Andersson. On 20 May, the conference was set for over-70-yr-old citizens. Päivi Topo, Ikäinstituutti (Age Institute), Sari Aalto-Matturi, Mieli ry; Panu Könönen, Suomen Latu (the Outdoor Association of Finland), and Pirjo Nuotio as moderator. Minister Kiuru was also present on the left outside the panel pictures, usually present as a separate speaker. The sign-language interpreter is in a separate picture (modified video screenshot).

On 29 April, PM Marin and Minister of Education Li Andersson declared that schools would re-open on 13 May. It was the most active day in April tweets. Both G5 topics T52 and T99 peaked: tweets criticized the government and THL for a perceived change in pandemic strategy, where suppressing the epidemy was no longer the target. Critical tweets claimed that the government’s indecisive actions implied a herd immunity approach, which would increase casualties. Some tweets criticized schools re-opening; others called for mandatory mask wearing. A few days later, trade unions declared their concern about safety regarding reopening. Figure 7 shows a clear spike in the discussions related to this topic prior to 1 May and in mid-May.

From 4 May, the government started planning to lift restrictions, and the last press conference with all-government party leaders declared a new strategy of testing and tracing. Responding to public debates, they promised a study of the usefulness of masks. Criticism on the lack of a recommendation regarding mask use started peaking T52 already on 4–6 May and, around school openings, on 15 May. At the end of the period, an administration-led press conference launched a study that said there is no evidence of mask use protecting the user. On 15 May, they still recommended that elderly people avoid contact, and on 20 May, the government had a conference for over-70-year-old citizens, with a retired TV anchor as the moderator. Tweets in our topics do not pay much attention to the elderly, with some mentions in T185 on health service access peaking on 6 April. The conference addressed the generational worry of not having seen grandchildren and the assertive nature of government recommendations (Häyry 2021).

Looser measures were followed by some other tougher lines, after expert meetings recommended tougher lines. One such example was whether Finns should stay in their cottages during the crisis: on 23 March, Pekka Timonen from the Ministry of Education and Culture (OKM) argued that Finns were better off at their cottages. But the government soon sided with suggesting staying at home, and PM Marin urged even after the lockdown on 15 April that it was “no time for going to the cottage.” Something particular to this government was that it sought to convey empathy and attention to special groups that suffered from the situation, bringing citizens, CSOs, and experts on the stage. The performance of control was no longer as tangible in the 30 March or 8 April events, and five-party all-female conferences were no longer apparent: potentially because social distances were kept, and the sign language interpreter was embedded in the video on parallel in a separate picture (see Figure 8).

Our third period spans from 1 August 2020 to 10 January 2021 (see Annex 13 for the number of tweets per day). Given the discussion above on the overall declining COVID-19 hashtag use, we also took keywords in this set (see Annex 12). Twitter activity regarding COVID-19 fluctuated a bit, with more activity in August, early October, and from late November, but it dropped before Christmas. Weekly fluctuations refer to weekends. Tweets related to all six topics seem to stay on similar levels during most of the period, with on mask use (T5, featuring tweets about experiences with masks, encouragement, and instructions) peaking in mid-August and early October. Topic on COVID-19 vaccines (T2) overtook others from early December steadily increasing towards the end of the period, just as knowledge of vaccinations increased. Discussions on the COVID-19 crisis and politics and the economy (T6, about the financial consequences of COVID-19 for individuals, entrepreneurs, and companies, and discussions on the Finnish economy and increasing debt) fluctuated, with an increased share in early September and then late October. General COVID-19 discussions grouped fear and anxiety even in religious tone and vocabulary (T1), short responses to large chains of Twitter discussions (T4), or COVID-19 cases and authorities (T3). Figure 10 shows our six-topic model from this dataset (see Annex 4 for topics and Annex 7 for individual figures).

The detailed topic modelling analysis was done with a 100-topic model (see Annex 12 for differences between datasets). The 20 most prominent topics and the government press conferences are shown in Figure 11. The description of the topics is in Annex 10.

For period three, we divided the topics into four loose groups according to the themes of the topics (see Table 4), including peaks with press conferences. The general discussions category in the third dataset contains more topics than in the two datasets of topic model analysis from spring. Therefore, the general discussions category is divided into two sub-categories: discussions about masks, tests, vaccinations, and general discussions (see Annex 10 for details). Topic frequency (Figure 11) shows slightly less-pronounced monthly and weekly fluctuations, as in Figure 10. Press conferences included scenarios on 10 December and vaccination availability on 17 December, and on 22 December it was promised that vaccinations would be offered to everyone. The European Union vaccination strategy was discussed, and the first vaccinations were given on 27 December. Twitter discussions emerged prior to the 29 December and 5 January press conferences (Figure 10).

August showed a slightly declining trend on overall tweets. The first government press conference was held on 6 August, which also showed a total of 10 topic peaks co-occurring with the press conference. The G4 and G1 topics co-occurred with this press conference (Table 4) on T81 about general mask usage. Some tweets referred to the press conference and asked why the mask recommendation was not announced already. Peaking G3 topics included some critical tweets towards the government (T57 and T29), deeming the government indecisive and not taking the required action fast enough regarding the pandemic in Finland. In addition, some tweets claim that the government was using the pandemic to transform the European Union into a federal state via the COVID-19 recovery pact.

On 12 August, the government’s perceived inaction was persistently criticized. Some tweets commented on the apparent intragovernmental disagreement between Ministers Kiuru and Lintilä regarding forced quarantine measures at the borders of Finland. On the evening of 12 August, PM Marin attended the main TV discussion program A-Studio (YLE 2020), leading to both praise and criticism on Twitter. The next day she held a press conference that included a recommendation to wear masks on public transport. Mask-related T6 and T81 peaked also on 6 August. T81 was about officials and organizations announcing the mask recommendation, and tweets related to T6 were about people tweeting about their experiences wearing masks, people reporting whether they have seen other people wearing masks in public transport and in public spaces and discussing mask recommendations. The tone of the tweets related to both topics was supportive, but there were some tweets where THL instructions were criticized. Overall, tweets supported the government’s mask recommendations.

Travel was the topic of the next press conference, but the end of August also demonstrated how the opposition woke up to contest governmental control. The 26 August press conference was an interior ministry press conference about COVID-19 security at the borders of Finland, co-occurring with eight topic peaks. These included G3 topics T29, with critique towards government and local authorities about insufficient COVID-19 testing, and an absence of mandatory testing at the borders of Finland and at Helsinki-Vantaa airport. T57 was, however, non-related to the topic of the press conference. After long months of consensus, the opposition woke up. On 26 August, the Finns Party leader Jussi Halla-Aho outlined the main targets of the party for the upcoming 2021 spring municipal elections, with one of the main themes being the economy. In many tweets related to T29, the critique is about how the government used the COVID-19 situation as an excuse to mishandle the economy. In addition, on 26 August, there were some tweets attacking the National Coalition party based on Coalition party leader Petteri Orpo’s opinion that he was concerned about the rise of nationalism. The political consensus of the pandemic spring was gone, and the opposition had room to maneuver.

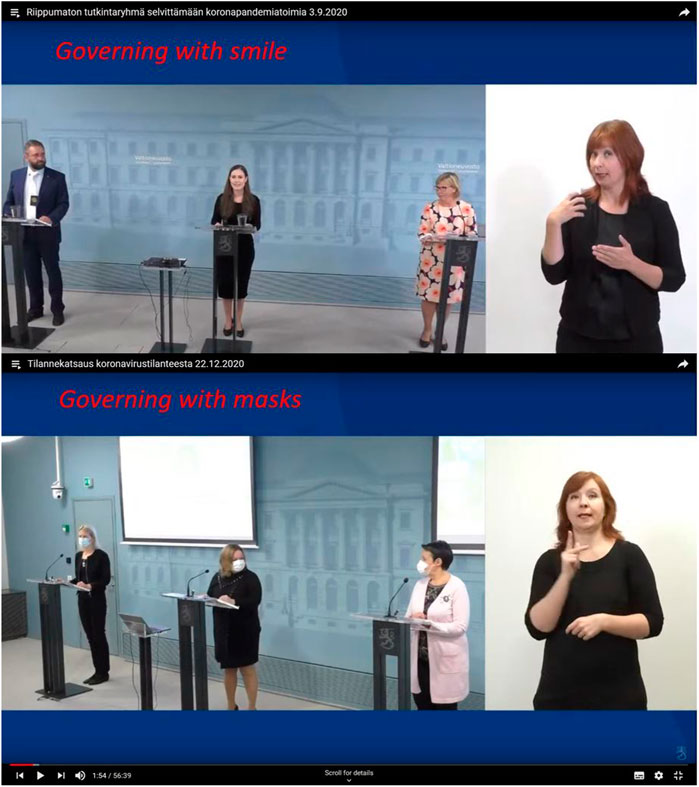

Activity related to COVID-19 on Finnish Twitter seemed to recede in early- to mid-September. Government press conferences were held on 3, 9, and 17 September. On 3 September, the PM and Minister of Justice Anna-Maja Hendriksson (RKP) launched the Safety Investigation Authority’s independent investigation to measures taken during the COVID-19 pandemic: no villains would be sought but the first investigation phase would build the sequence of events from January to July (SAI 2020; see Figure 12).

FIGURE 12. Juxtaposition: Mood change that also indicates how late mask wearing started in Finland. A rare appearance of the PM in Autumn 2020 press conferences to stress the importance of opening an investigation to crisis control of the pandemic on 3 September: Veli-Pekka Nurmi, director, SAI; PM Marin, and Minister Hendriksson. On 22 December, STM and THL host an information session on COVID-19: Marjo-Riitta Helle, Finnish Medicines Agency, Fimea; Minister Kiuru; and ministry’s most senior public official Kirsi Varhila. The sign language interpreter is in a separate picture (Modified video screenshot).

In September, it becomes obvious to the authorities that some measures ought to be used: from 17 September, a regional facemask recommendation was taken, and on 24 September, Puumalainen (THL) stated that “I think new measures ought to be adopted.” On 24 September, the press conference declared that updated mask recommendations would include interior public spaces, coinciding with a major peak in mask-related topics T6 and T81. Tweets in T81 addressed organizations announcing their own mask recommendations related to the official announcement and individual Twitter users sharing and discussing the updated recommendations. Tweets in T6 discussed updated recommendations, tweeting their experiences with masks, and reporting how other people were using masks. Overall, the tone of the tweets in both topics was supportive of mask usage, but some tweets criticized THL’s perceived change of stance on facemasks, questioning why the institute now recommended a mask, even though in spring no recommendation was given. Some tweets criticized that the recommendation was not strong enough and that a mandatory mask requirement should be enforced. In the G3 topic T29 peaking on 22 and 25 September, tweets criticized both the government and THL for lacking a mandatory mask requirement and the government for being too slow to act.

From the end of September to mid-October, discussions related to COVID-19 increased, with mask topic T6 as one of the more pronounced discussion subjects in this period. Both mask topics T6 and T81 significantly increased from 6 October to 9 October, with T6 peaking on 9 October and T81 on 8 October. The government press conference on 7 October was about local authorities and new restrictions of restaurant opening hours and alcohol sales. Kiuru appeared to talk about regional authorities’ role and introduced some regulations on restaurant openings. From 8 October, the presenters wore masks: Salminen (THL) stressed how the COVID-19 infection situation was worsening in Europe and in Finland. T6 tweets on 6–9 October debated masks and their protection, usage, and user experiences. T81 tweets questioned the government’s mask recommendations and requested a mandatory mask-wearing policy. With the frequency of both T6 and T81 tweets increasing already from 6 October, it seemed that the government press conferences were not the driver for increased Twitter discussions. Especially on 8 October, T81 tweets also questioned the government and officials’ mask stance in spring 2020, with some being extremely critical towards the government and even claiming that the government lied about the mask situation. Critical tweets referred to April’s mask and protective equipment supply problems. In G3 topics T29 and T57, the government was attached for not recommending the use of facemasks in the spring. As a reaction to the public discussion, including accusations of lying, Minister Kiuru’s press conference on 14 October addressed the mask situation in spring arguing that expert knowledge did not support mask usage and comprehensive guidance could not be issued. T81 peaked on 12 and 15 October, and receded after 16 October, signifying an end to the “mask gate” discussion. We argue that the press conference on 14 October positively contributed to closing the discussion about the mask situation in the previous spring: an expression of control by the government reaction to the public discussion. Overall, 6 October was one of the most active Twitter days in the autumn period with the mask-related tweets in topics T6, T81, and T57. The “mask gate” was one of the main points of contestation in the autumn-period hashtag landscape against the government.

After late October, Twitter discussions related to COVID-19 receded, but there was an increase again in Twitter discussions from mid-November onwards. The first government press conference of the month was held on 12 October, and the next government press conference was held on 19 October, with five topics peaking the same day. The mask topic T6 started to increase after 17 November, reaching its peak on 25 November. It included discussions and arguments as to how much masks help, the experiences of people using masks, and people reporting how much other people are using masks. G3 topic T29 peaked on 24 November: government was criticized for not enacting strict COVID-19 restrictions and for lack of leadership. Some accused Kiuru of making confusing statements. Tweets blamed the government for using the possibility of a state of emergency as a threat. PM Marin appeared with Kiuru, for first time since early September, at the 26 November press conference addressing the rapidly increasing number of cases. She urged people to act more responsibly. Topic T7 on COVID-19 tests peaked, and the government was criticized for not showing proper leadership and for issuing confusing communication in relation to COVID-19 measures (T57). This suggests that the government reacted both to increase in COVID-19 infections and to increase public discussion about the rising infections.

During December and early January, discussions receded from late November levels but remained active besides the Christmas period from 23 to 27 December. T31 and T90 related to vaccinations started to peak. Only 3 and 22 December press conferences were held with ministers. The message from Kiuru was stern: cases were increasing, and contacts should be reduced. On 22 December, she promised that there would be vaccinations “to all who want them.” Vaccinations started in Finland on 27 December. The first press conference in 2021 on 5 January covered COVID-19 vaccinations and the vaccination strategy. Already on 4 January, discussions related to government response in topic T29 peaked, with doubts about the government vaccination strategy, as the government was accused of being too slow or even delaying vaccinations.

We chronologically generated and investigated data on press conferences for who was there and what was said, leaving other features of the press conferences outside this study. The timing of press conferences offered chronology to the study. We periodized our research into three segments and generated both a wider perspective with five to six topics, and a more refined analysis with multiple topics. Here, we studied the topic peaks and qualitatively analyzed tweets in those moments, investigating transformations in the “hashtag landscape” capturing the discursive field, crisscrossed with antagonism but also public building performing control, and contestation through Twitter.

In the first period, the Marin government performed collective responsibility for COVID-19 measures by presenting a unanimous voice and staging ministerial presence through press conferences. Space was given to ministers responsible for different policy areas, and most ministers were involved in the pandemic situation. In the Twitter data, we can recognize criticism towards the government and the expert body THL. The second period saw a fragmentation of the faces of control in press conferences from a presence of multiple ministers to experts for epidemiological and technically defined topics such as masks. There were also fourth sector actors and citizens. Economic resilience, rather than restrictions, featured as the main topic of the first all-female government’s press conference on 20 March. The PM also started the second such event on 30 March with thanks to individuals and businesses. At the next conference, on 8 April, she argued that in the middle of a crisis, it was important to help individuals and businesses to survive. The tweets contested leadership, siding with the presidential suggestion of the “covid fist,” criticizing Uusimaa closure, finally re-opening of schools, and lax approach to facemasks.

The government communicated the graveness of the situation via several ministers, which also unveiled cross-sector effects and attempts to solve it in the spring and summer. This showed the strength of the government and legitimated the use of the emergency powers legislation in government control. In the performative sense, the appearance of several ministers in the press conferences, and even the info session for children on 24 April, demonstrated the government’s control of the issue. The conferences always started with ministers’ speeches and the political control of the situation, followed by the health authorities’ overview of the situation and questions from the audience of media onsite or over video or phone link—or selected children, in the case of the children’s info session (Figure 9). At other times, they included the senior citizens and CSOs. The autumn showed COVID-19 had become business as usual and governance of the crisis normalized. Financial consequences were discussed in August, and some of the measures of the government were criticized publicly; particularly, the opposition parties took this opportunity.

In the last period, the ministers did not perform pandemic control together, with PM Marin appearing on stage three times. The strongest presence of multiple ministers was on 3 September, when in two distinct conferences on the same day Kiuru presented the plan to regulate the COVID-19 situation, and then the PM and Hendriksson presented the SAI investigation. After 3 September, if any of the ministers attended the press conference, it was Kiuru and the health authorities that handled the performance of control in the ongoing COVID-19 situation. This all suggests that if the second wave pandemic strategy of the government were to fail, Kiuru (SDP) would be responsible. Indeed, in normal conditions in Finland, the control is on the regional authorities to regulate the health districts and municipalities based on the advice and recommendations of the health authorities, THL and STM. This model was explicated on 28 August in the health authorities’ press conference and by Kiuru on 7 October and 26 November. After delegation, however, regaining hold of the performance of control is difficult.

Our aim was to test and launch a novel way to study social media and politics through mixed methods and mixed data. We developed an interpretive topic instrumentalist and rhetoric-performative approach to the hashtag landscape, captured in a snapshot with keywords and ever-developing hashtags, using diverse data in tandem. We used topic modelling as the first reading of the large dataset and as a tool to analyze deeper discursive shifts. Instead of looking for strict causality, we investigated patterns and co-occurrence (Glynos and Howarth 2007), and instead of treating the probability of topics and terms as absolute measures of reality, we used it to better understand and interpret discursive shifts and antagonisms. This machine-learning approach suited our non-essentialist data-driven approach, where rich data would also offer different emphasis and readings. We wanted to make transparent how to read Twitter data discursively, longitudinally, and as a discursive field rather than a set of predefined actors.

By matching the topics with periodization marked by the press conferences as tuned into temporal pointers, any country or crisis case could be studied, offering tools of non-essentialist, post-structuralist approaches to comparative politics, political communication, and governance even comparatively. Looking closer at topic timelines and the actual tweets in different moments, we could see shifts in the contents of the topics as new meanings emerged in the vocabulary that the LDA topic modelling provided. With the attention that relationality in discourse analysis stresses, we were able to interpret discursive shifts and emphasis in the hashtag landscape. Contextualizing through an alternative dataset, here the press conferences, was useful for interpretation. In turn, the juxtaposition with the hashtag landscape offered a new perspective to the official communication.

In the Finnish case, existing literature’s comments of complying citizens’ minuscule resistance at the face of re-territorialization (Moisio 2020), and argument on the style of COVID-19 communication as a moral coercion of the public opinion (Häyry 2021 43-44), would in the light of our data apply to some degree. The case of COVID-19 and the discussion on ethics of both policies and communication continue and fall beyond the scope of this article. We could, however, observe points of contestation. A crisis imaginary with economic decay was a powerful nodal point in press conferences in the spring and the hashtag landscape also in the autumn. Issue of mask use dominated our data in the hashtag landscape. Adopting different policies, multi-level governance, and the precise question emerging in the tweets of whether the government had been lying in the spring about masks point to the pertinence of ethical debates in pandemic politics.

Our approach to “hashtag landscape” captures discursive shifts, transformations, nodal points, and imaginaries within the discursive field. Regarding discussions related to masks, in spring, discussions masks were related to specific events like emergency supply problems or the opening of schools, or general critique towards the government. In autumn, the mask discussion was a topic of its own on Twitter, as people tweeted about their everyday experiences wearing masks and reported whether other people were wearing masks. Still, masks remained a controversial topic during the autumn, when tweets criticized and blamed the government for lying about the mask recommendations.

Regarding the critique, a consistent theme was the perceived lack of action by the government. In both spring and autumn, the government was criticized for not taking decisive action on the COVID-19 situation. In addition, critics claimed the government was not showing leadership. The government’s lack of leadership was expressed as “hiding behind the health authorities” (or scientific knowledge) and was contrasted with the leadership shown by President Niinistö. Another consistent point of critique was towards THL and Salmela, on incompetence. The emergency supply mask crisis, or “mask gate,” was one of the more salient issues that the government was criticized for in spring and briefly in the autumn period. The government got criticism for the (lacking) COVID-19 checks at Helsinki-Vantaa airport in the spring and the European Union recovery package in the autumn.

Discussing governance, a central shift in the communication, was from an affective all-government performance to the institutionalization of pandemic governance into an administrative matter dealt with by mask-wearing bureaucrats and on occasion the minister responsible, Kiuru. This changed the mood of who was performing control and how, as well as what control is about. The government’s current struggles in spring 2021 to convince people to reduce contacts, wear masks, and contain virus variants derives from the transformation within the performative process of control. The paradox of controlling the uncontrollable or appearing in control of the fully uncontrollable also unveils the uneven, heterogeneous, and antagonistic discursive field captured through our methodological approach.

Our analysis of themes and criticism shows that at least some government press conferences ended even satisfied discussions on contested themes. In the autumn, the government left the floor of COVID-19 control to the experts and administration. The absence of the full government in the autumn press conferences meant that a collective responsibility for COVID-19 measures was not similarly performed and control claimed. The appearances of Kiuru and on occasion PM Marin provided a weak, temporary symbol of control compared to the spring 2020, when the all-female government made a powerful performative claim on controlling the pandemic. In the hashtag landscape’s critical voices that on occasion included misogynistic attitudes and science-skepticism, the Marin government’s youthful, multivocal presence in its female-led press conferences was contrasted with one strong (male) President’s aura of control in crisis, indicating that the presidentialist undercurrent in the Finnish population (Paloheimo et al., 2016) still exists.

In spring 2020, the performance of control was palpable as the faces of the crisis and key nodal points in the hashtag landscape became ministers and the national authority. The emergency powers legislation shifted control to the government from regional authorities and municipalities in spring 2020, and by autumn, those powers were returned to the regional and local bodies. This meant that control was also decentralized, and the second wave took speed while contestation emerged on both the economy and the masks, until vaccinations became the dominant issue around Christmas. The unveiled administrative-discursive shift and performative absence of the government in the autumn could partly explain developments in spring and summer 2021. The performance of control and contestation between distinct levels of governance, persistent with the extension of the pandemic, would merit further investigation.

A detailed analysis of 2021 was out of scope of this dense study, yet we could have used the same method of matching government press conferences with the hashtag landscape. Potentially, similar developments as in 2020 could have been uncovered. The absence of the central performative control by the Marin government was however notable: issues were delegated to Kiuru, and the regions and the delegated performative control would be difficult to regain without a stress on a crisis, which in turn could have backfired the government’s own policy. The discussion on COVID-19 persists in new virus variants and issues of vaccinations. In the theme of vaccination, the Astra Zeneca skepticism would have emerged in spring 2020. By August 2021, the delta-variant wave hit Finland, whose vaccination coverage was 66 percent for first dose and 35 percent for second dose (THL 2021). The nodal points of the discursive field we found, from reluctance to mask wearing, economic insecurity, Marin and Kiuru’s policy (too strict for some, too loose for others), travel restrictions, school closures, to vaccinations, would re-emerge in the hashtag landscape. New themes and explanans could also emerge crunching the big data piñata of 2021. Furthermore, it would be useful to engage with the questions of which kinds of discursive developments and entanglements appear in the hashtag landscape. Further research could include zooming to the account level within the same machine-read data.

With this article, we highlight the importance of the study of social media in political analysis. It is a pertinent part of investigating discursive and hegemonic confrontations on the wider, contingent discursive field. To hold governmental power at the face of a pandemic or crisis requires constitutive performance. In social media, captured through the hashtag landscape, this performance is contested and ratified by emerging hashtag publics. Through our novel research method of interpretive topic modelling and discourse theory, exploring a social media and government interaction, we hope to have demonstrated both the contingent nature of control and articulations of power at the crux of contemporary politics.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation. The videos used as data are available from the Finnish Government's YouTube channel: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rSt7xZBp-uM&list=PLbR0oH-F5gDWj9Z6AuIi3wi4bcN3tiZL4.

Both authors have equally contributed to the study. Datasets 1 and 2 were gathered by EP on the Mecodify tool on the University of Helsinki server, and Ass. Prof. Walid Al-Saqaf provided dataset 3 through a request on the latest version of the Mecodify software he has developed (https://github.com/wsaqaf/mecodify). The topic modelling was done by JK. Interpretation was by both authors.

This article has received funding from Academy of Finland grant 320275 for the Media and Society program project Whirl of Knowledge: Cultural Populism and Polarisation in European Politics and Societies.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2021.689614/full#supplementary-material

Agarwal, A., Salehundam, P., Padhee, S., Romine, W. L., and Banerjee, T. (2020). Leveraging Natural Language Processing to Mine Issues on Twitter during the COVID-19 Pandemic. arXiv [Preprint]. Available at: https://arxiv.org/abs/2011.00377 (Accessed September 30, 2021).

Blei, D. M., Ng, A. Y., and Jordan, M. I. (2003). Latent Dirichlet Allocation. J. Machine Learn. Res. 2 (4–5), 993–1022.

Doogan, C., Buntine, W., Linger, H., and Brunt, S. (2020). Public Perceptions and Attitudes Toward COVID-19 Nonpharmaceutical Interventions Across Six Countries: A Topic Modeling Analysis of Twitter Data. J. Med. Internet Res. 22 (9), e21419. doi:10.2196/21419

Erkkilä, T. (2012). Government Transparency: Impacts and Unintended Consequences. London: Palgrave Macmillan.