94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci., 07 June 2021

Sec. Comparative Governance

Volume 3 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2021.663874

This article is part of the Research Topic"Performing Control" of the Covid-19 CrisisView all 12 articles

This article investigates the narratives employed by the Romanian media in covering the development of COVID-19 in Roma communities in Romania. This paper aims to contribute to academic literature on Romani studies, particularly in Central and Eastern Europe, by adopting as its case study the town of Ţăndărei, a small town in the south of Romania, which in early 2020 was widely reported by Romanian media during both the pre- and post-quarantine period. The contributions rest on anchoring the study in post-foundational theory and media studies to understand the performativity of Roma identity and the discursive-performative practices of control employed by the Romania media in the first half of 2020. Aroused by the influx of ethnic Romani returning from Western Europe, the Romanian mainstream media expanded its coverage through sensationalist narratives and depictions of lawlessness and criminality. These branded the ethnic minority as a scapegoat for the spreading of the virus. Relying on critical social theory, this study attempts to understand how Roma have been portrayed during the Coronavirus crisis. Simultaneously, this paper resonates with current Roma theories about media discourses maintaining and reinforcing a sense of marginality for Roma communities. To understand the dynamics of Romanian media discourses, this study employs NVivo software tools and language-in-use discourse analysis to examine the headlines and sub headlines of approximately 300 articles that have covered COVID-19 developments in Roma communities between February and July 2020. The findings from the study indicate that the media first focused on exploiting the sensationalism of the episodes involving Roma. Second, the media employed a logic of polarization to assist the authorities in retaking control of the pandemic and health crisis from Romania. The impact of the current study underlines the need to pay close attention to the dynamics of crises when activating historical patterns of stigma vis-à-vis Roma communities in Eastern Europe.

Among the plethora of problems caused by the COVID-19 infection, the ethnic component of many societies was affected by a sharp rise in xenophobic and discriminatory discourses (Karalis Noel. 2020; Woods et al., 2020). The magnitude of COVID-19 generated fertile ground for discourses infused with xenophobic and racialized elements that affected marginalized groups (Devakumar et al., 2020). Attempts to control the virus in isolated communities created a stream of social stigmas and prejudices against minorities (Roberto et al., 2020). As the virus spread into most societies, the quest to apportion blame, amongst the uncertainty caused by the novel Coronavirus, was fostered by the media’s coverage and social media’s interpretation of the phenomenon. Studies indicate that the social and cultural elements of one’s society have shaped and sharpened xenophobic and racist views during COVID-19, especially in the case of minorities (Perry et al., 2020; Elias et al., 2021). Elsewhere, academics have noted the role of some mainstream media as discriminatory catalysts. The media’s disproportionate coverage of minorities have exacerbated social stigma, xenophobia and discrimination during COVID-19 (Matache and Bhabha, 2020).

In Romania for instance, where approximately 2 million Romani live according to the Council of Europe (2015), accounts of the media’s disproportionate reporting vis-à-vis minorities were framed on defining the ethnic component as a community transmission vector (Costache, 2020; Plainer, 2020). As the events began to unfold, the Roma people were fashioned as vectors of transmission (Creţan and Light, 2020). Several causes led the Roma to be cast as transmission vectors – ranging from the diaspora’s inflow and the preserved social constructs of the Roma’s ethnicity – and these underlined the foundations of these discourses in Romanian society. In addition, incidents from the border with Hungary involving Romani people moved the diaspora’s guilt to a niche discourse aimed at the Roma. As time passed, the Romanian people, like the rest of the world, began to cope with the psychological impact of COVID-19 and stigmatization (c.f. Javed et al., 2020). Inside the country, other incidents involving the Roma communities during lockdown caught the media’s attention and, implicitly, generated racist attitudes and hate speech on social media (Costache, 2020). Subsequently, two narratives began taking form: are the Roma people a transmission vector given their precarious condition in society? And how will the Roma communities cope with the new restrictions imposed by the authorities? Primarily abetted by the media’s disproportionate coverage of Roma-related incidents, the discourse reconstructed the ethnicity’s premises by casting the Romani people as those who were rebuking the Government’s measures to control the pandemic. To echo Judith Butler’s work (1988), Roma identity was not only performed; it also was performative.

The purpose of this article is to investigate the dynamics of the Romanian media in performing control through discursive-performative repertoires in the case of Romani communities during the early months of COVID-19 in Romania. The aim of the paper is to understand how the image of Romani people and communities were fashioned by the media’s language in times of crisis. Herein, I wish to make two contributions to the field of Romani Studies. First, I include a disciplined interpretative case, i.e., the town of Ţăndărei – a southern town in Romania, which was at the core of reporting in the first half of 2020. At this juncture, I seek to bring social theory and media studies together with academic literature on Romani studies to understand the performativity of Roma identity through absence, as a result of implicit understandings employed by the media. To do so, I have developed a theoretical approach based on the works of Butler (1988), Bell (1999), Butler (2007) on performativity. Then, I intersect Laclau’s and Mouffe’s (2001) understanding of discourse with Brubaker’s theory of ethnicity (2004) as a liaison between the agency of discourse and the agents, i.e., the mainstream media and Roma. And finally, I have added notions of media stereotyping and the profiling of minorities (Ross, 2019; Ross et al., 2020) to understand their dynamics in times of crisis. Within this framework, I look at how linguistic and syntactic structures perform the identity of Roma in times of crisis through absence and oversimplify the characterization of the Romani people as vectors of virus transmission.

Second, I look to contribute to Romani academic literature by applying the notions of post-foundational theory, i.e., antagonistic logic and hegemonic articulation. With these lenses, I provide a deeper understanding of how the Roma minority’s identity is performed when portrayed in antagonistic contexts, opposite law enforcement, and as representative of the dominant majority. Research needs to explain how the mélange between linguistic markers and the identification of certain territorial spaces determines isolated communities, albeit lacking any ethnic denomination and slur in the press, to be recognized immediately as “unlawful Roma.” Also, research needs to explain why the antagonism between specific ethnic communities and law enforcement in specific areas determines the identity of Roma as being “violent.” Are historically embedded stereotypes so engraved that these markers determine the identity of Roma if provided any contexts? Besides wishing to contribute to existing Romani academic literature, I also look to connect the present study with already existing academic literature. For instance, it was noted that the distrustful attitude of Roma toward institutions is a result of the latter’s enforcement of stereotypes and that the language the media often uses to describe Roma people tends to criminalize them. Also, Roma communities are often associated in the media with marginality.

The structure of this paper is as follows: The next section develops the conceptual framework of the study. The former revolves around the assortment of post-foundational theory, media studies and Romani studies. In Method and Material, I explain the methodological framework, the methods of data generation and analysis, and the limitations of the study. Results highlights the results facilitated by the methodological framework of the study. Using the NVivo software tool on the data collected for this study, the language-in-use discourse analysis provides two findings. Discussions positions the results within existing Romani academic literature. Lastly, in Conclusion, I present the conclusions of the study and underline new pathways of research.

This study is a good example of how the discursive-performative makeup of Roma’s ethnicity takes place in times of crisis and is utilized to perform control of COVID-19 and abet the legitimacy of the authorities. This study contributes to Romani studies, particularly in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE). Since the fall of Communism, this region has constituted a fertile ground for stereotyping and discriminating against Roma (c.f. Ringold, 2000; Cooper, 2001; Tamás, 2013). Academic literature proves that the Roma are the most socially unaccepted, denigrated and discriminated ethnic minority in CEE (Pogány, 2006; Tileagă, 2006). Due to their distinctiveness, Roma are oftentimes “portrayed as beggars, criminals, profiteers, and lazy, being a target of marginalization and social exclusion, as well as perpetual discriminatory and violent practices on an interpersonal, institutional, and national level” (Sam Nariman et al., 2020, p. 1). Studies have shown that anti-Roma attitudes are expressions of dominant social norms in Eastern Europe (Kende et al., 2017). Empirical research indicates that Roma awareness varies across countries like Romania, Slovakia, and Hungary, from a threat to national security, to sympathy, and empathy (Sam Nariman et al., 2020). Since the fall of Communism, many of these impressions have been shaped by public institutions and the media.

Research has revealed that the media is prone to articulating ethnic opinions and stereotypes if the reporting circumstances facilitate this sort of discourse (Sedláková, 2006; van Dijk, 2012). Schneeweis (2012, p. 675) argues that the Roma are often represented under two stereotypes. One provides a romanticized version of Romani music and folklore, whereas the most common classifies the Roma as “poor, dirty, unhealthy, genetically inclined to commit crime, irresponsible, promiscuous, and, above all, the racially inferior and unwanted other.” Such narrative structures are common in the media and other institutions (Csepeli and Simon, 2004). Thus, it is by no coincidence that societies manifest strong antagonism and antipathy toward the Roma through an array of xenophobic and negative attitudes (Schneeweis, 2012). For instance, Erjavec (2001) showed how Slovenian media legitimized and naturalized discrimination against the Roma through syntactic structures. Elsewhere, Weinerová (2014) showed how the Czech media stereotyped the Roma culture, and implicitly the Romani people. Yuval-Davis et al. (2017) show that media discourses on Roma in three countries including Hungary are shaped by the label of “otherness.” Research argues that these sorts of conditions are the product of power relations between in-groups and out-groups (Elias and Scotson, 1994). The migration issues of Romani communities often determine the Roma as an “out-group” or the “other” (Uzunova, 2010). Davis (2019) consider that the migration issue is usually connected to the Roma’s sense of belonging. This is elaborated below. That is why the combination between stereotypical frameworks and attached identity markers is a strong incentive in harboring negative attitudes toward the Roma (Bilewicz et al., 2017; Hadarics and Kende, 2019). After all, during these processes, facilitated by institutional settings, the in-groups can preserve their dominance and assert their power to the detriment of the Roma.

Such processes backfire. Recent studies that have examined these dynamics in CEE have shown that Roma are distrustful of legal institutions because these bodies have supported historical patterns of stigma and have a strong internalization of racial stigma (Creţan et al., 2020). The same patterns are signaled by Duminică (2020). Other studies have indicated how transnational workers and Roma from Eastern Europe are subjected to racism and labeled under stereotypical frameworks as “criminals” (Humphris, 2018). Because these dynamics between institutions and the Roma facilitate disbelief and skepticism, scholars have pointed out the need for Roma communities to cultivate empowerment. In their study, Málovics et al. (2019) argue that the Roma need to be better represented both in the public and private spheres, in both state and private institutions. Such policymaking would raise awareness both outside and within the Roma community, mitigate the prevalence of the usage of stereotypes, and increase the representation of the Roma in both the public and private sectors. Despite successful examples of policy interventions that have mitigated Roma’s marginality (Berki et al., 2017), new policy interventions are needed to adjust the welfare of marginalized Roma people in CEE. Also, policy interventions are needed to modify the inequalities and poverty that prevail among Roma communities from CEE. Matache and Bhabja argue that the Roma need “humane and protective measures that ought to recognize Roma’s structural inequalities and which must be tailored to Roma’s racialized vulnerability – access to water, community facilities, health care assistance, direct cash payments, and income supplements to counterbalance inevitable drop offs in daily wage labor.” (2020, p. 380) Others suggest that despite the frail political and socio-economic progress attained by the Roma through policymaking, their relationships with the non-Roma majorities are still governed by disproportionate power structures (Thornton, 2014). Some agree that these power structures were fostered in CEE during Communism and have continued under the guise of social norms since the transition to democracy (Guy, 2001). Two dynamics have resulted thereafter. On the one hand, these have fragmented the trust of Roma in institutions and have propelled their marginalization, while also downgrading their contributions to societies and casting doubts vis-à-vis their belongingness. On the other hand, the enclosed reactions of the Roma have consolidated and maintained the stereotypes of the majority ethnic groups.

Returning to the variable of belongingness, scholars argue that this may heighten the friction between the Roma and the majority ethnic groups (Rachel, 2019, pp. 12–13). The rift between the majority ethnic groups and the Roma is, perhaps, founded on the understanding of the former vis-à-vis notion of “nation”; and that of seeing the Roma through the lenses of “ethnicity.” This conceptual distinction enlarges the social divide between the majority ethnic group and the ethnic minority, thereby creating fertile ground for misrepresentations, stereotypes, and anti-Roma attitudes. Designating the Roma under the migratory and nomadic classifications, unlike indigenous, scholars observed that stereotypical frameworks are built on the premises of one belonging to one’s nation (Brubaker, 1996; Harff and Gurr, 2004). Historically, the issue of Roma belongingness constituted fuel for far-right movements, which often target the Roma (Creţan and O’Brien, 2019).

In the realm of ethnic studies, the boundaries between the majority and minority have always been determined by the social constructs of discourse (Hartsock, 1987; Verkuyten, 2005). To this discussion, Bourdieu (1992) added that language provides the means for one group to maintain power over another. Take, for instance, the cases of Romania’s largest ethnic groups. The identity of ethnic Hungarians from Romania is constructed through the repetition of specific scripts, a series of political acts that reinforce the idea of “otherness” (Culic, 2006). In the Roma’s case, the identity has been constructed by repeating a language that re-counts how marginalized the community is in Romanian society. This enforced the notion of “othering” (Creţan and Powell, 2018; Creţan and O’Brien, 2019). The process of “othering” a minority is not new in political science. Laclaudian discourse theorizes the construction of social meaning through the logic of polarization that ultimately is constituting the “other” (2001, pp. 94–95). In the asymmetric relationship between the majority and minority, the process of “othering” is maintained through a set of sedimented practices that define the hegemonic articulation of the majority across time and concerning other minorities. Studies revealed that it is quite common for the majority to employ different sorts of “othering” or “otherness” vis-à-vis various minorities (c.f. Palonen, 2018; Goździak, 2019; De Cesari and Kaya, 2020). Not only does the nature of polarizing discourses constitute the contingency of “othering” a minority, it also attaches the geographical space that “the others” inhabit (Creţan and Powell, 2018). From the performativity side, Bell (1999, p. 3) adds that “ethnic affiliation can be performed to a lesser extent depending on the context within which ‘the Roma’ finds him or herself.” In both contexts, the existence of a dominated group is outlined when being differentiated from the majority through the representation of stereotypes. While these sorts of scripts rearticulate the majority’s hegemony, the identity of the minority is effectively distorted and reduced to a malign “other.” By reducing the Roma to marginalized communities, grounded by an archaic system of rules and often in conflict with the authorities, their identity is ultimately demarcated. Thus, Roma’s essence is assembled from the set of sedimented practices and stereotypes cultivated and preserved, in time, by a society ingrained in its hegemonic discourse.

The role of performativity in constructing ethnic identity has previously been researched (c.f.; Lahiri, 2003; Shimakawa, 2004; Sullivan, 2012; Clammer, 2015). In Romania, performativity – with respect to ethnic studies – has been constructed through the reproduction of discourses that include stereotypical or nationalist repertoires that, on the one hand, define the premises of power relations between the majority and minorities, while, on the other hand, constituting the sedimented practices that subvert the nature of discourses. Herein, discourse is understood through the post-foundational lenses. Building on Laclau’s (2001) work, this study understands discourse as the process with which meaning is determined by repeating its subjects’ social circumstances. Such practices constitute “through a stylized repetition of acts” (Butler, 1988, p. 519) the discursive identity of Roma as an ethnicity. The latter, Brubaker (2004, p. 11) theorizes as an entity that engulfs “practical categories, cultural idioms, cognitive schemas, discursive frames, organizational routines, institutional forms, political projects.” Indeed Brubaker (2017), Brubaker (2020) agrees with the premises of Laclaudian discourse, i.e., built as a set of articulated signs, which give meaning to a social field represented in a binary worldview. Thus, the interrelation between Laclaudian discourse and Brubaker’s take on ethnicity defines the social construct whereby the subject is identified. It also outlines the subject’s distinct categories, which act as signifiers when recognizing and distinguishing the nature of the minority, say, from that of a majority.

However, there are other ways in which a group can be recognized via discourse, either via verbal elements or nonverbal elements related to the use of language (Kittleson and Southerland, 2004). Schröter and Taylor (2017) have theorized that individuals or groups can be performed through absence. Ward and Winstanley (2003) revealed that the representation of minorities is dependent on both the presence and absence of terms. From this perspective, Sullivan (2012, p. 436) asserts that “individualized ethnicity is shaped by discourse.” Concerning discourses, one can recognize the context of Roma not by necessarily naming them directly but by layering the social context in which they reside, their customs and societal organization, the specific actions they do, and by underlining the stereotypical characteristic of the community as opposed to the majority or authorities. All these are sedimented practices that have stood the test of time.

In the context of media, the stigmatization of minorities results from “distorted narratives” (Ross, 2019) that reduce the identity of the minorities to misrepresentations. In the eyes of Bell (1999, p. 2), “one needs to question how identities continue to be produced, embodied and performed, effectively, passionately and with social and political consequence.” In this study’s case, the stereotypical identity of Roma has only been reported by the media after the incidents appeared in Roma localities, as actions that disregarded the authorities’ measures. By casting the Roma’s stereotypical identity (see Creţan and Light, 2020, p. 8) alongside the law enforcement’s symbolic attributes, the media’s coverage attempted to control the COVID-19 narratives.

This article adopts as its case study the town of Ţăndărei, which was widely covered by the media during its pre- and post-lockdown stages. In analyzing the media’s coverage of Roma during COVID-19, Matache and Bhaha (2020, p. 380) argue that “media outlets have been broadcasting similar narratives blaming Roma, especially those recently returning from other countries, for spreading COVID-19. The Romanian media is one of the worst examples.” In focusing on the events happening within Romania, Plainer (2020, p. 9) adds that “in the case of Ţăndărei the media representation of the events could also have been a trigger for stereotyping and labeling.” Structurally, the Romanian media system belongs to a Polarized Pluralist Model (c.f. Hallin and Mancini, 2004). The polarized model incorporates the relative control of media by political parties, extended clientelism, late democratization and the weaker development of rational authorities.

Some consider the Romanian mainstream media to lack independence, which could affect the standards of everyday reporting (Negrea-Busuioc et al., 2019). One could argue that the context of the Romanian media is a largely revenue-driven milieu centered on creating strategies that connect audiences and viewership with bombastic headlines and clickbaits. For example, three outlets, i.e., Romania TV, Antena 3 and Kanal D, which were also selected for this research, make a living, according to Watchdogs, out of clickbaits (Paginademedia.ro, 2020b), sensationalist headlines and misrepresentation against the Roma (Paginademedia.ro, 2020a). Despite fines from the National Audiovisual Council (CNA) for their reporting, these broadcasters, i.e., Romania TV, are revenue driven and sensation-prone media outlets. Previous studies have documented the usage of misrepresentation by the Romanian media in the case of migrants, Muslims and Romani people. For example, examples of stigmatization in the Romanian media have been studied previously during the migrant crisis (Marinescu and Balica, 2018). Other documented misrepresentations of Muslims and Islamophobia have included exaggerated coverage (Pop, 2016). In the area of Romani studies, Alina Vamanu and Iulian Vamanu indicated the degree of pejorative representations of the Roma in the Romanian mainstream media after 2007 (2013). They showed that the Romanian media constructs a binary strategy under the cover of sensationalist headlines that promotes discrimination, which accentuates Roma’s societal marginality and sharpens the divide between the majority ethnic groups and Romani communities.

In the wake of the events from Ţăndărei and other communities, a survey was conducted by the Romanian Institute for Evaluation and Strategy (IRES)1. Although the survey does not apply to the entire population, it stressed some interesting findings that are related to the present study. First, 52% of the population who participated in the survey read or heard about Roma during the state of emergency, 83% of them received this information from television, and 7% from social platforms. The proportion of negative news about Roma was almost double compared to positive news: 41% negative news versus 28% positive news. Building on the negative coverage of Roma underlined by the IRES research and on the comparative studies of Erjavec et al. (2000) about Slovenian media and Sedláková (2006) on Czech media, I hypothesize that the media normally does not cover Roma-related topics, nor does it employ stereotypes unless Roma’s actions generate instability, create conflict, or are a threat to the homeland majority. Erjavec et al. contend that media coverage rests on “using special techniques, like stereotypes and generalization to concentrate particular ‘negative traits’ of the Roma” (2000, p. 7).

With these in mind, this study asks how the language employed by the Romanian media to describe the events revolving around Roma communities undertook discursive-performative practices of control during COVID-19 and eventually performed the identity of Roma? How were the usage of crisis and Roma-related stereotypes used in the media reportages to reinstate the control of the dominant society?

This study used primary data from the main Romanian broadcasters grounded on their audience-based ratings from early 2020 during the pandemic (see Paginademedia.ro, 2021). Also, online news portals were used as primary data. Aside from this, eleven Military Ordinances are analyzed and connected with the process employed by the media thereafter. The data from media consisted of five national broadcasters: ProTV (15), Antena 1, and Antena 3 (all part of the Intact Media Group) (22), Kanal D (8), Digi24 (15), and Romania TV (34), and six online news portals Libertatea.ro (56), Adevarul.ro (46), Evenimentul Zilei.ro (29), Hotnews.ro (19), Mediafax.ro (31), and G4Media.ro (14). Furthermore, this research added other articles from other online news portals that were widely accessed according to the Google Search Interest index. The latter showed which pieces of news were the most accessed and read during February–July 2020. Likewise, by looking at the Google index, one can reveal what syntactic constructions determined the readership/viewership to enquire about specific pieces of news. In total, this study collected 291 specific examples. The timeline for data collection is February–July 2020. The latter encompassed the response of the Romanian health care system when facing Covid-19 cases domestically, the return of diaspora, government responses, the first municipal lockdowns, the introduction of the state of emergency, the International Romani Day (8 April), the Orthodox Easter (12 April), and the end of the state of emergency.

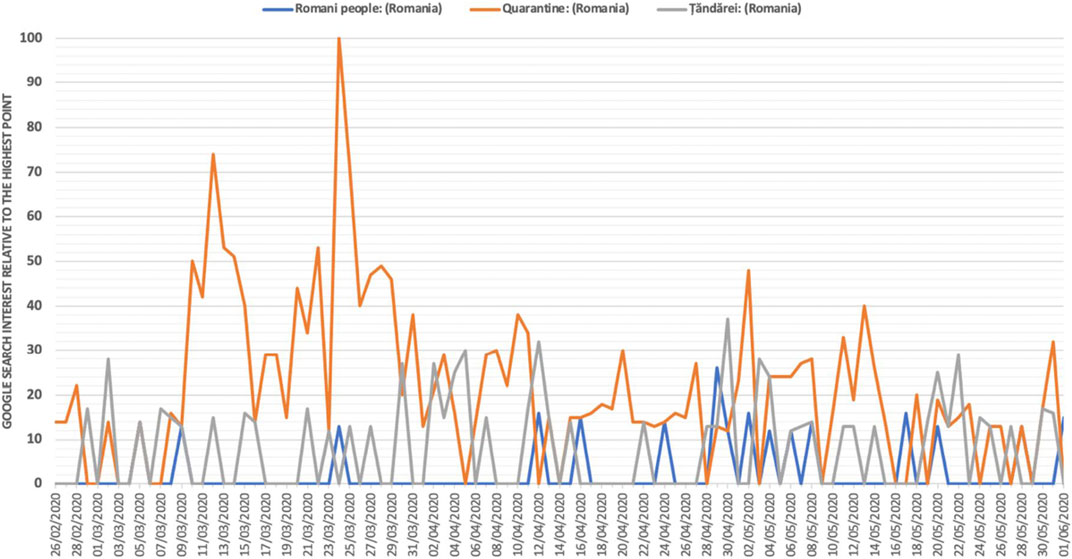

The association between the spikes in COVID-19 cases between 23 March and 16 May and the measures adopted by the authorities augmented the notoriety of the Roma in the media. Following the national lockdown, the increased COVID-19 cases were associated with the events unfolding in some Roma localities. The number of infections grew exponentially compared with the rest of the country. These surges brought the Roma into the spotlight. As the media began to cover all Roma-related incidents, the demand from the public increased. Between March and May, Google queries about “Roma,” “Ţăndărei,” and “Coronavirus” news increased (see Figure 1). The articles were selected based on Google’s Search Interest index. Additionally, the data-search included the words “Roma,” “quarantine,” and “Ţăndărei.” Largely, this study focused on the case study of this article, e.g., Ţăndărei,. Between February and July 2020, a noticeable increase of Roma-related content, particularly from Ţăndărei, was registered by the above-mentioned repository.

FIGURE 1. The Romani people, quarantine, Ţăndărei topics looked by Romanians on Google between 26th February and 1 June Romania. The search results indicates that the series Romani people are marked with blue, while the search results marked with orange indicates the series quarantine. The series Țăndărei is marked with gray. The value 100 represents the peak of popularity, the value 50 represents that the topic is half as popular, while 0 indicates that there is not enough data. The Panel 2 was created using data from the Google trends website.

For analysis, this study considered analyzing the headlines and subtitles of the pieces. Two factors justify the choice of titles and subtitles selection. On the one hand, the editorials of journals are known to employ hyperbolic language to foster news consumption as part of a media logic (Blom and Hansen, 2015; Ross, 2019). On the other hand, the behavior of news consumers is shaped by a headline’s effectiveness, and they likely take the information from it at face value, without reading the rest of the content (Kuiken et al., 2017; Science Post, 2018). The Romanian NVivo language package was installed to help with the transcription of the corpus of text. The results were then translated into English by the author of the study. The whole corpus of the 291 articles amassed 17,330 words.

After it was compiled, the NVivo software was used to determine the word frequency and the cluster analysis of the nodes “Roma”, “Ţăndărei”, “Coronavirus”, and “police.” Because the nodes are grounded on attribute and contextual values, one can visualize the prominent themes from the dataset by observing the relations between the main nodes and their contextual connectors. To make this more visible, I set the difference between the nodes “Ţăndărei,” “Coronavirus” and “Roma”, “police” in pairs demarcated by the colors red and blue. In this manner, one can see how the architecture of syntaxes is likely to connect the main nodes with connectors. To make this evident, I have also added a temporal element to the analysis to separate the shift in language reporting, in the likeness of Military Ordinance No. 7. The latter reflected the governmental decision to quarantine Ţăndărei and the most likely event that changed the premises of media coverage, i.e., from hidden to an overt ethnic coverage of COVID-19 events. Eventually, these theses can help during the second stage of this study’s methodological process, i.e., language-in-use discourse analysis. Additionally, several parameters were added to make the analysis effective: 1) stemmed words for the main nodes “Roma”, “Ţăndărei”, “Coronavirus”, and “police”; 2) the display of words was set to 50; and 3) their minimum length was set to four. The text was also manually cleaned. The interjections, conjunctions, or prepositions (e.g., “in”, “from”, etc.) were removed. Second, based on the software results, this study employs a language-in-use discourse analysis of the data to “discover the micro dimensions of language, grammatical structures and how these features interplay within a social context” (Salkind, 2010). This discourse analysis aims to show that the results determined by the NVivo software constituted a vocabulary. Then, the analysis of grammatical structures from the 291 articles is brought into dialogue with the theory of performativity (Laclau, 2001) to explain how the performative control and hegemonic articulation are operationalized in the study. These are understood as follows: hegemonic articulation is the agency with which media underscored that the state’s power is totally and evenly dispersed within the boundaries of marginalized communities. Performative control reflects the ability of the media to convey and regulate the stereotypical identity of Roma (e.g., violence, lawlessness, etc.) in grammatical structures.

The limitations of the study are presented based on the framework advanced by Price and Murnan (2004). Thus, this study’s limitations rests on its small sample (n = 291) i.e., newspaper and media items. Although the sample encapsulates the pieces published by the largest broadcasters and major news portals from Romania from February to June 2020, the results of the study could have been richer if pieces from some local newspaper outlets were considered for analysis. However, the inclusion of such local outlets was disregarded on the basis of reachability, time-taking strategies to connect the readership to reporting, and capacity to inform the readership and viewership. Take for instance the Observatorul, Observatorul de Prahova (2020), with the title “You, lazy people who didn’t pay taxes and came back to steal and kill us! How long will we have to endure your thick-skin, quarantine, hospitalization, behavior?” (2020). Indeed, the content of this piece depicted hate speech, stereotyping frameworks and could have influenced the analysis somewhat. However, the reachability of local newspapers is limited to their regions, regardless of social media dissipation. In contrast, the reach of the selected broadcasters and online portals is national, consistent, and subject to a far-reaching audience. When considering the exclusion of local reporting, the arguments of van Dijk (2000, p. 34) were considered. Van Dijk contends that media’s reporting, in the case of minorities, rests on well-crafted strategies, it adopts specific roles during reporting, and it reproduces prejudices and stereotypes of ethnic minorities “between the lines.” Also, the media strategies of reporting minority-related topics are consistent and employed during longer periods of time; and these are replicated across all media. So, while opinion pieces from local newspapers could add more details to the analysis, their reporting does not fall under what Richardson argues as “a product of a complex process of a systematic sorting and selecting of events and topics according to a socially constructed set of categories” (2006, p. 77). Instead, the national media is part of such processes. They retain coverage consistency and can inform viewership/audience more widely.

During the early months in Romania, the control of COVID-19 was performed by the Government and by the media. On the one hand, the Government assessed the situation generated by the growing cases of infections and decreed Military Ordinances to control the transmission rate. The language used by the Government was formal, albeit with some differentiations related to localities predominantly inhabited by Roma people. Although the official vocabulary used by the Government did not stress the ethnicity of Roma, the language of the Military Ordinances stressed the names of the geographical spaces predominantly inhabited by Roma, thus performing an “ethnic affiliation to space” (Bell, 1999, p. 3) to which Roma are linked. One such case is the Military Ordinance No. 7, which instituted total lockdown in Ţăndărei. As media already focused on the ethnic component that determined the increase of COVID-19 cases in Ţăndărei (Stefanescu, 2020), the language of the Military Ordinance No.7 formalized the identity of whom is to blame for this crisis, albeit the lack of ethnic denomination. On the other hand, the media broadcasted the Government’s safety measures and covered the incidents whenever the Military Ordinances were disregarded. These situations outlined the seriousness of the COVID-19 crisis, thereby enlisting a sense for hyperbolic coverage. Also, any contempt or nonconformity from the Roma generated a public and governmental uproar, which in turn, reinforced the stereotypical identity of the ethnicity.

The media used two kinds of language scripts. First, the media employed a hyperbolic choice of words when reporting events happening in Roma communities. It did so by linking the increased number of infections and local quarantine with the Roma ethnicity in several cases. Second, the media employed a repetitive script infused with stereotypes that outlined the “logic of antagonism” (Laclau, 2001) between the Roma and law enforcement. While the language used by the Government when performing control of COVID-19 was formal, one can argue that by emphasizing the localities’ names predominantly inhabited by Roma, without naming them, the officials drove the attention of the media to continue the story by attaching a “symbolic and ethnic affiliation” (Sullivan, 2012, p. 434) between the space and the people. The gravity from some localities inhabited by Roma, both determined by increased infection cases and conflicts between Roma and police, forced the authorities to introduce lockdowns. These polarizing situations incentivized the media to report on the stories through stereotypical characterizations, resulting from an “unconscious bias or newsroom pressures” (Ross, 2019, p. 401). Next, this study outlines the Government’s discursive-performative practices through the use of Military Ordinances and normative acts. This paper highlights how the media moved from its logic of a revenue-aimed strategy to employing a polarization logic.

The discursive-performative practices of the Government employed a “hegemonic articulation” (c.f. Laclau, 2001). Their role cemented the Government’s “condition as a particular social force (which) assume(d) the representation of a totality” (Laclau, 2001, p. 10).

On March 17, the Ministry of Internal Affairs issued its first Military Ordinance2 to tackle the virus’s spread. The implication of the military terms created anxiety, as the new procedures were not explained to the public. On March 21, the second Military Ordinance was issued3. This legislation instituted curfews from 10 pm to 6 am, banned groups larger than three people on the streets, and all shopping centers closed, except for supermarkets. On March 22, the officials reported the first three casualties, as the number of cases grew from 66 cases on March 21 to 143. Consequently, on March 24, the Ministry of Internal Affairs issued the third Military Ordinance, which instituted a national lockdown, ordered the military to support police’s efforts, and restricted outside movement, except for work activities4. On March 28, Romania reported 308 new infections. And in response to the rise of cases, the Ministry of Internal Affairs issued a fourth Military Ordinance, which granted law enforcement the power to impose fines and sanctions5.

The Military Ordinance no. 5, adopted by the Romanian Government, banned all international travel6. Toward the end of March, the Romanian hospitals, ill-equipped and mismanaged, started to report rapid new cases among its healthcare workers and patients, “resulting in hospitals and even entire cities being quarantined” (Dascalu, 2020, p. 3). The first example to be quarantined by Military Ordinance No. 6 was the Suceava county hospital, which experienced many infections amongst its staff and patients7. Shortly thereafter, the entire municipal area of Suceava county was placed under total quarantine. The events happening in Suceava began being repeated in other regions of the country. Concomitantly, at the western borders, Romanian expats were waiting to enter the country in long queues mainly because of the tense political relationship between Hungary and Romania (Creţan and Light, 2020, p. 6). In response, the Romanian authorities issued several statements urging the diaspora not to come home, overburden the healthcare system, and jeopardize their families’ safety. By the end of March, almost 950,500 people arrived in Romania before Easter, mostly from Spain and Italy. Less than 3.29% of the people who arrived were tested at the borders (Pora, 2020).

The Border police’s errors, coupled with the disregard of some people for the Government’s measures, generated local transmission hubs. Inside the country, the media began reporting about localities that were considered for quarantine. As Romania entered its last two weeks before Easter, the restrictive climate was disregarded by many people who participated in large social gatherings at religious events (Dascalu, 2020). Specifically, social gatherings from Roma localities increased community transmission, pressing the officials to issue new measures (Mateescu, 2020). At this point, the discursive-performative practices of control moved from national to local level. Its incentive was the manner the locals from Ţăndărei concentrated its dominance despite the restrictive measures. Hence, the authorities discourse framed, based on hegemonic articulation, the means to reorganize power relations by decentralizing the relative dominance of the locals from Ţăndărei via “new formation of power” (Laclau, 2001, p. 16).

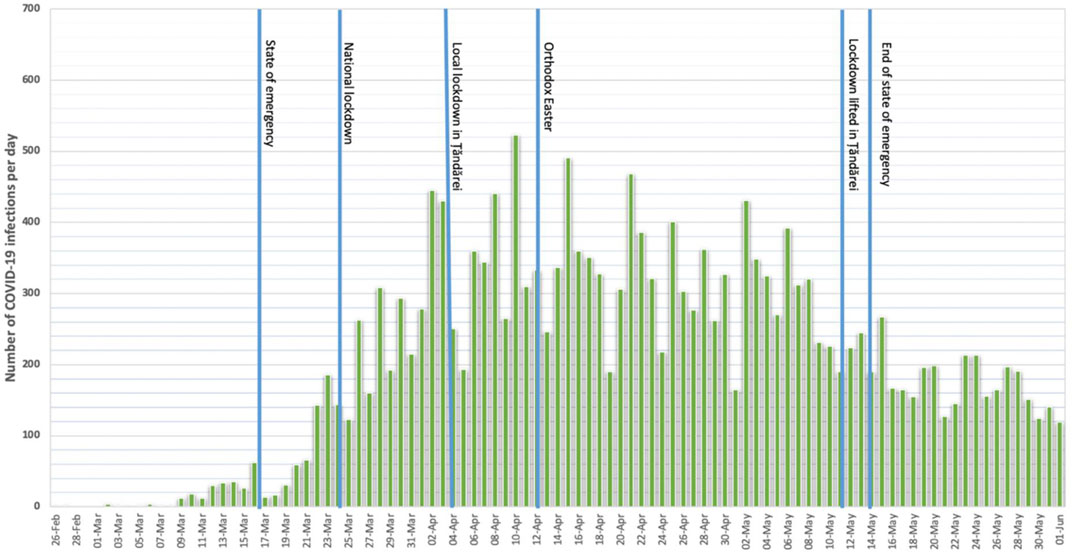

Hence, by 3 April, Romania recorded 430 new infection cases. Such record numbers prompted the Ministry of Internal Affairs to issue its seventh Military Ordinance on 4 April8, which extended the national lockdown and imposed a local quarantine in the town of Ţăndărei which (see Figure 2). The new discursive-performative practices of control indicated the “discursive location” (Laclau, 2001, p. 93) where hegemonic articulation was needed to retake control. Ţăndărei became a transmission hub after the arrival of its large diaspora disregarded the restrictive measures. Although the quarantine usually would take 14 days, the officials kept the town of Ţăndărei in total lockdown for forty-two days due to events happening in the community. The social reality composed of social interaction between authorities, media, and the people from Ţăndărei, consolidated the locality “as a symbolic social sign” (Butler, 1988, p. 519) in the discursive-performative practices of control. In the end, it took Military Ordinance no. 11 on 11 May to lift the lockdown in Ţăndărei. Three more military ordinances are issued during this time, mainly to provide new guidelines for food provisions. On May 14, two days after Easter was celebrated in Romania, the officials issued Military Ordinance no. 12, which ended the nationwide state.

FIGURE 2. shows the number of daily COVID-19 infections in Romania between 27th February and 1st June 2020 with green, while the governmental actions connected to the lockdown of Ţăndărei are highlighted with blue. Panel 2 was created with data provided by the Romanian Ministry of Internal Affairs.

Nonetheless, the events that both proceeded and continued throughout the lockdown from Ţăndărei became the main headline in Romania, implicitly raising the media’s interest in the Roma events. Three factors generated intense media scrutiny during the Ţăndărei lockdown. First, Ţăndărei has a large ethnic Romani diaspora dispersed across Europe. Some of Ţăndărei’s Roma were previously involved in human trafficking – stories that scandalized Romanian society before COVID-19 emerged (Sandu, 2019). Second, the incoming of Ţăndărei’s diaspora posed both a logistic and security problem for the Romanian police. The latter supplemented their forces, first to quell emerging conflicts between rival Roma factions and then to enforce control toward the Roma, who disregarded the restrictions. Third, the subsequent confrontations between the police forces and ethnic Romani during the lockdown accentuated the socio-cultural debate about Romani’s status in Romania. Stimulated by the Government’s actions in Ţăndărei and other localities, the media joined the efforts to recentralize control. Hereafter, the study presents the results of the software analysis. The NVivo results are separated into two sections: the frequency distribution of the TreeMap and the subsequent cluster analysis. Both tools are considered during the language-in-used discourse analysis.

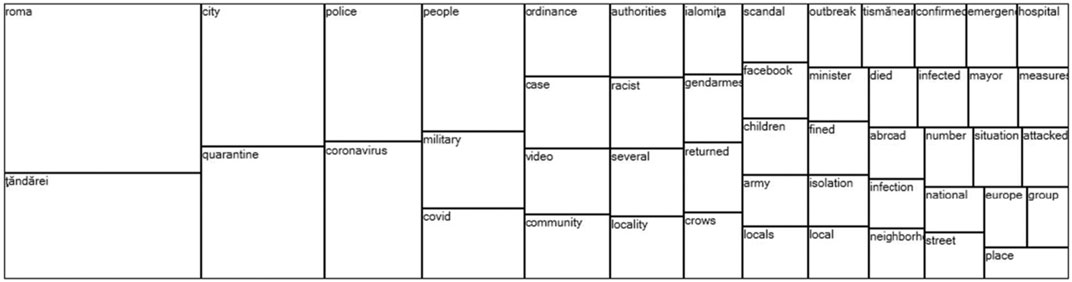

This analysis showed what words are predominantly used by the Romanian media to describe Roma-related events and to capture the readership/viewership’s attention. The analysis revealed that the media concentrated its coverage on the Roma and Ţăndărei. This fact is shown by the results of the frequency distribution of the TreeMap (Figure 3). The latter revealed 232 mentions of “Roma” with a weighted percentage of 2.47%, and 147 mentions for “Ţăndărei” with a weighted percentage of 1.57% in all 291 titles and subtitles, respectively. Moreover, the analysis shows that the usage of words like “quarantine” (143), “city” (125), “police” (94), and “Coronavirus” (93) were the most encountered. On the one hand, the representation of larger boxes suggests the presence of the aforementioned words in the structure of the titles, as these offered direct and informative content to their viewers.

FIGURE 3. Reveals the Tree Map result. From the left to the right, the size of the boxes determines for frequency of the coding references and the contextual themes of the dataset. The main boxes are “roma” and “Ţăndărei.” Each are followed by smaller connector that define the theme associated by the media. Figure 3 was obtained with data (n = 291) gathered by this study.

On the other hand, at the lower level, the analysis showed the presence of words such as “infected” (44), “scandal” (43), “gendarmes” (40), “returning” (38), “fines” (32), and “attacks” (29) with a similar number of coding references that might imply their usage in the subtitle of the articles. Journalistic practices attribute the presence of subtitles whenever the readers are looking to find an experience that gives substance to the main headline. Both the high percentage and lower percentage of the coding references from the dataset suggested two prominent themes. First, the media outlets provide direct and informative content in their headlines by associating the protagonists of their stories, i.e., Roma and the police forces from Ţăndărei, to capture the attention of readers or viewers through clickbait titles. Second, the content underlined in the headers is substantiated with additional information that Offered the readers and viewers an experience, which mostly Conveyed a negative setting. In the dataset’s case, NVivo found that the titles are composed of pejorative-aimed words such as “scandal”, “attacks”, and “fines”, and are closely connected with words such as “police” and “gendarmes.” These repetitive interconnections were perhaps used to sensationalize the content and arouse the attention of news consumers. This finding confirmed the IRES survey results, which asserted that half of Romanians knew Roma-related incidents during the COVID-19 crisis because of the negative coverage received during the pandemic.

Although the public’s perception vis-à-vis the Roma minority was negative beforehand, the negative contexts indicated by the findings could indicate the media capabilities to refresh the viewers’ reality via stereotypical representations. Likewise, this finding might indicate the viewers’ and readers’ lenience in accepting negative perceptions when being flooded with hyperbolic content that strengthened their stereotypes, especially if a powerful, informative mechanism commonly conveys the image of minorities. According to the IRES survey, the public perception apropos Roma is fragmented. This study finds that the vocabulary used in the all-encompassing media coverage, coupled with the pandemic setting, did not aggravate society’s perception of the Roma. Rather, the media portrayed Roma-related incidents in its broad coverage and thereby relocated the Roma image from a marginalized entity into the national spotlight. To echo Bell’s words (1999, p. 3), “identity is the effect of performance.” This mediatic process revitalized dormant stereotypes against the Roma by “enacting cultural conventions” (Butler, 1988, p. 525). The results show that although not present in the major coding references, some contain a small number of references that insinuate the blaming context attributed to Roma in the pieces’ subtitles. For example, repeated references like “infected” (44), “situation” (36) “isolation” (33) “leave” (30) “outbreak” (30), and “measures” (25) are in close proximity with nodes that have similar values, including “military” (54), “ordinance” (48), “gendarmes” (40), and “fines” (32). Notice that for each of the repeated words that denoted negative contexts or crises, other words denote safety and control. In the academic literature of performativity, “social action requires a performance which is repeated” (Butler, 1988, p. 526). So, while the media acknowledged and repeated the words that concocted the meaning of the crisis, they also performed control of COVID-19 by equally repeating words that balanced the crisis’s gravity with words that denoted management and organization.

Stylistically, the visualization of the coding references from the Treemap might indicate the construction of the blame narrative via the close association between the nodes representing “Roma”, “Ţăndărei”, “coronavirus”, and “police”. To relativize this finding, this study presents a cluster analysis to reveal the manner the general scripts amalgamate. In the following, the cluster analysis determined that the media’s language during the crisis used two scripts. First, the press reported the misdeeds and the increase of COVID-19 cases amongst Roma hyperbolically. Second, responding to local incidents, the media outlined the antagonism between Roma and law enforcement in violent settings, for one thing, and how authorities reclaimed control on the other side.

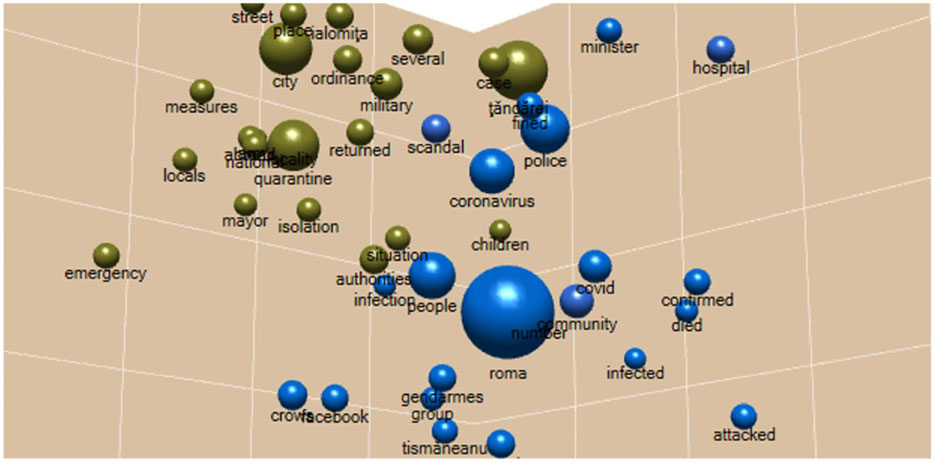

This analysis showed the architecture of media’s language used to describe the Roma-related events during COVID-19. The cluster analysis yielded two overall scripts connected with the main nodes “Ţăndărei”, “quarantine”, “Roma”, and “police” (see Figure 4). The analysis showed that the architecture of the first script is likely determined by connectors like “military”, “measures”, “isolation”, which are more likely to be positioned in syntactical constructions alongside the main codes’ “quarantine” and “Ţăndărei.” The analysis revealed that the shift between the two scripts is determined by the temporal element of Military Ordinance No.7, which instituted total quarantine in Ţăndărei and changed the architecture of the second script. The first script, marked with green, conveyed the contexts in which authorities adopted several measures to control the virus’s community transmission in localities predominantly inhabited by the Roma. This chronology of this script is determined by the arrival in the country of the diaspora and the evolution of COVID-19 in several localities inhabited by the Roma. This script’s main nodes are “Ţăndărei” and “quarantine.” Their contextual connectors designated the space and reaffirmed through a “symbolic identification” (Sullivan, 2012), without naming the Roma, the people for which the restrictive measures are adopted. Hence, in this script, the media performed the identity of the Roma through absence (Schröter and Taylor, 2017), as the ethnicity is being conveyed by both in the presence of connectors such as “Ţăndărei”, “returned”, “quarantine”, “military”, measures”, and “isolation” and in the absence of words such as “Roma.”

FIGURE 4. Reveals the cluster analysis of the nodes Roma, Țăndărei, quarantine, police from the corpus of text of the 291 articles collected for this research. The NVivo software differentiated the context of the four nodes into two colors. First, Roma and the police along with their contextual connectors are marked with blue. Second, Ţăndărei and quarantine along with their contextual connectors are marked with green. Panel 1 was obtained with the data (n = 291) gathered by this study.

Conversely, the discursive-performative practices of control, embodied by the second script, are marked with blue. The architecture of this script conveyed the period reported by the media after the Military Ordinance No.7 was adopted and the confrontations between the Roma and law enforcement started. This event changed the syntactical format of the media, which abetted by the certification of the government, begun performing control. The control practices are determined by the main nodes “Roma” and “police.” This script conveyed Roma’s identity in opposition to that of the police. These forces’ dichotomy outlined the “logic of polarization” (Laclau, 2001) between the “police” and “Roma.” Also, the connectors of the main nodes highlight how the Roma’s identity is performed. On the one hand, the Roma’s identity is performed by “a reenactment and reexperiencing of a set of meanings already established” (Butler, 1988, p. 526). The meanings are conveyed by the connection between “Roma” “police”, and “gendarmes.” This interrelation might indicate the stereotypical representation of the Roma identity in Romanian culture through the lenses of “othering.” By positioning alongside the signs of control, the identity of Roma is reduced to stereotypical frameworks. The repetition of stereotypes, along with the antagonism between law enforcement and Roma, constructed the identity of Roma and performed a discursive control of Roma during the pandemic. It did so by placing Roma opposite the police enforcements, at a time of crisis, when the ethnicity’s actions were estimated to jeopardize the quarantine efforts.

Comparatively, the first script determined by the nodes “Ţăndărei” and “quarantine” differed from the second script that is constructed by the nodes “Roma” and “police.” The language of the first script underscored a positive context, whereby for each action, there is a counteraction that keeps a contextual balance. For instance, the connectors “several”, “locals”, “returned”, “case”, and “infected” are balanced by the media in the contextual framework with connectors like “isolation”, “quarantine”, “ordinance”, “emergency”, and “measures”. These contextual connectors might indicate the meaning of seizing control of the space through a “hegemonic articulation” (Laclau, 2001). In this script, the media’s coverage focused on conveying a sense of control over the area that bears “cultural meanings” (Butler, 1988) for the Roma. Reporting the sense of control of the space (i.e., locality of Ţăndărei) and then continuing to the individuality of the people inhabiting the space might indicate the process adopted by the media when performing control of COVID-19.

Oppositely, the language of the second script determined by the nodes “Roma” and “police” conveyed a negative framework. Herein, the presence of negative connectors is not counterbalanced by an almost equal number of connectors that indicate “social actions” (Butler, 1988). Instead, the presence of negative connectors constructed Roma’s identity as a “group.” The latter were “fined,” they are who “attacked,” they are who produced “scandal.” In contrast, the values of “police” and “gendarmes” are determined by the social paradigm attributed by the media, i.e., exercising control. Also, this script, unlike the first one, defined not only the identity of Roma but also connected the identity of Roma to the consequences generated by the COVID-19 “community”, “infection”, “infected”, “confirmed”, and “died.” Unlike script one, where the focus is on the agency and space, in script two, the media focused on the agents and performing control via polarization. Also, unlike script one, where the agency is represented with an equal number of causes and reactions, in script two, “police” and “gendarmes” are likely represented as balancing and sufficient forces that recentralized control of COVID-19.

Furthermore, the cluster analysis revealed that contextually, connectors and nodes from both scripts are interlinked. For example, the nodes “Ţăndărei” and “police” are intertwined, despite belonging to different clusters. However, it is their connectors that provided background to the interrelation between the two nodes. So, the connectors “case” and “fined” established a contextual relationship between the two nodes, as in the first stages of the COVID-19 lockdowns from Ţa conte, the increased number of “cases” forced the authorities to consider lockdown and eventually “fine” people who disregarded the measures. Next, this study investigates through a language-in-use discourse analysis the two scripts determined by the cluster analysis.

The languages of the two scripts are different, as both scripts developed differently in time. One script performed control of the space, while the other recentralized power from the Roma. Depending on how the situations developed in Ţăndărei, the language of media changed from descriptive and informative content to a blaming content. The media coverage is influenced by the manner the authorities enforced order, by how they lost it temporarily, or when they reinforced it via an augmented force. For instance, the semantics of script one is grounded in the media’s logic (Ross, 2019). This means that the media linked hyperboles and negative coverage to generate interest from their audiences and stimulate revenue.

However, as the authorities’ efforts were disregarded and the number of cases increased, the media changed its semantics in script number two. Therein, the media’s discursive-performative practices of control changed. It did so through a language that underscored the antagonism between the Roma and the police. Taking a cue from the post-foundational studies, the media’s language in the second script constituted the “other” as opposed to the “self” (Laclau, 2001). Reechoing a language that harnessed the fear of Roma, the media controlled how the identity of the Roma is performed via sedimented practices. This discursive-performative practice validated the future more aggressive actions of the police as necessary steps in recentralizing control.

In the search for broader audiences, both visual and written media expanded their coverage during the health crisis by adopting a media logic. The latter focused on the creations of hyperbolic titles to sensationalize the news and, thus, to increase revenues.

Emphasis on the Roma was reported shortly after accounts of the Roma’s misdeeds shifted the narratives. For instance, Romania TV, the third-largest broadcaster, reported the following accounts. “The Roma from Suceava returned from Italy and lied at customs that they were coming from Germany.” “I liken the quarantine period to prison” (Romania TV, 2020a). In other instances, the media highlighted individual cases of Roma stranded at the border due to a lagging Border police system. Romania’s biggest media outlet emphasized the “Border scandal with several Roma families” (ProTV, 2020). As the border police updated their sorting system, the media’s attention shifted domestically toward localities like Ţăndărei, which reported the return of hundreds of people that overburdened the officials’ capabilities. Apart from some irregularities, the incentives that grasped media’s coverage were the religious rituals, like burial processions, which, according to the Military Ordinance no. 6, restricted the partaking of a large number of people. Few religious gatherings in some Roma communities were presented in a bombastic manner by the media “Unbelievable! Hundreds of people at a funeral in Baia Mare. All restrictions violated!” (Evenimentul Zilei, 2020c). Other impromptu events that had religious connotations, in which Roma were the protagonists, were sensationalized in the headlines “IMAGE OF THE DAY: Dozens of Roma prayed to God, on their knees, on the street, to get rid of the Coronavirus. The police fined them” (Romania TV, 2020b). Despite sensationalizing the event, the headline employed a discursive-performative practice of control by aligning a content that may imply the milieu of Roma and their reduced identity in the Romanian society. Although similar events happened in areas inhabited by the ethnic majority, the media’s attention focused on the topics that highlighted Roma-related events.

The Military Ordinances affected the Roma communities, as their freedom of movement was restricted. Studies suggest that the movement constraints affected Roma’s socioeconomic position (Creţan and Light, 2020). While human-rights groups pleaded with the Government to assist these vulnerable groups, Roma-related coverage increased. The socioeconomic factors involving Roma communities were next covered under a language deliberately exaggerated, which combined hyperboles and Roma-related stereotypes like “Hallucinatory situation. The Roma are asking for help: We have no more money because we cannot steal” (Evenimentul Zilei, 2020a). In early April, the Roma community leaders warned that the situation would only worsen for their peers in Romania. The lockdown and the military ordinances affected the livelihoods of the Roma. Consequently, jobs like metal scrapping were not possible anymore.

The Government’s measures were accepted with difficulty in the Roma communities, as these mitigated the financial means of Roma to make ends meat (Plainer, 2020, p. 7). Decades of mistrust in state’s authorities and marginalization, coupled with Roma’s archaic community systems, made communication difficult with the local officials, who reported new numbers of infections and deaths in the Roma communities. Consequently, the intervention of police forces in Roma communities was underlined under a hyperbolic language that emphasized the gravity of COVID-19 infections and a high number of deaths. Bombastic headlines from the written media moved from providing direct and concise information to creating larger-than-life emotions and impressions for its readers: “COVID-19. The time bomb from Ţăndărei” (Recorder, 2020). In other cases, intentional hyperboles like “carnage” were used in headlines to describe power-relations in Roma communities. One title claimed, “Carnage between the underworld from Sighet. Protection money is also paid during a pandemic” (Evenimentul Zilei, 2020b), while another underlined “the carnage from Bolintin Vale” (Evenimentul Zilei, 2020d). The use of hyperboles and the stereotypes associated with the Roma communities conveyed an intentional negative exaggeration.

As the events unfolding in Ţăndărei forced the authorities to supplement their forces on the ground, the media “reinforced the production of stereotypes” (Ross et al., 2020, p. 75). Roma’s stigmatization was observed under two recurring themes: the promotion of violence within the Roma communities and antagonism toward the authorities. Academic literature on the media and stereotypes argues that ethnic groups are typically marginalized during crises that generally depict them narratively in stereotypical roles and as the problematic other (c.f. Ross, 2019). The additional measures adopted by the Government in Roma-inhabited localities, highly mediatized by the media, strengthened the social stigmatization and moved the “othering” from a dormant to a proactive position. The images constructed in the headlines and subtitles moved the minority to an even more marginalized role. The forms of articulation employed by the media during this logic, coupled with specific structural moments, gradually modified Roma’s identity.

First, the stereotypical representation was reinforced by emphasizing violence between the community members. The fifth-largest broadcaster, Romania TV, highlighted several times during its daily reporting the violence and tribalism of Roma communities. For instance, one consistent coverage underlined that “Video – Fighting between Roma clans from Vlaşca, Ialomiţa county” (2020d). Other broadcasters followed suit. Written media reported similar incidents in consecutive editorials. While underlining the inter-community violence, the latter stressed the clannish characteristics of Roma in negative settings. For example, the daily Libertatea depicted a scandal between Roma families by stressing the elements of difficulty and law enforcement “Scandal stopped with difficulty by the police between two Roma families from Ploieşti. Nine people were detained” (2020). Again, the discursive-performative practices of control combined inter-group violence with hegemonic articulation that determined the “identity of social agents” (Laclau, 2001, p. 77).

Another example in which the clannish element is highlighted is a piece from the daily Evenimentul Zilei (2020e) which reported an incident between rival families as follows: “Disclosures. The clan war in Baia Mare was confused with a robbery” (2020e). Notice that the author kept, under a headline meant to grasp the reader’s attention, Roma’s stereotypical characteristics perpetuated in the oral tradition of the Romanian society, i.e., “robbery.” The academic literature on stereotypes also corroborates this assertion (c.f. Creţan and Powell, 2018). Another daily, Adevarul.ro, reported a case from a Roma neighborhood in Săcele, Braşov county. The event was widely mediatized by most of the outlets due to its violent content and background story that focused on the tribalistic elements of Roma communities. The headline from Adevarul.ro was selected as the title with the most negative rhetorical elements associated with Roma. Adevarul.ro presented the incident as follows: “VIDEO UPDATE Scenes of rare violence in a neighborhood in Sacele. Dozens of thugs quarreled with pitchforks, axes, and clubs in front of police” (2020a). In this headline, the rhetorical power is centered on the emphasis of “rare violence.” Then the dominant tone is set on defining the space the marginalized group from Săcele inhabited. The headline continued by designating the perpetrators with additional rhetorical elements that consolidated the violence’s negative framework: “pitchforks”, “axes”, and “clubs.” The rhetorical component of “police” acts as the measurement tool of the “violence” committed by the Roma, besides the unlawfulness of the incident. By focusing on the rhetorical power of “violence,” alongside “police,” the media “criminalized the language” (Ross, 2019, p. 400), describing the Roma as “thugs”. Likewise, the emphasis on the inter-community incidents, behaviors, and attitudes may have underlined the tribal aspect of Roma’s structural and societal organization. The result of this rhetorical exercise was “othering” the image of the Roma.

Second, the opposition toward the authorities emerged as the most encountered in the data analysis. Espoused by both written and TV media, the “logic of antagonism” (Laclau, 2001) was depicted as a clash between two forces – an act that “depicted negatively as the problematic other” (Ross, 2019, p. 397), the Roma. The use of strong language and the over-dramatization of facts simplified the contrast between the protagonists of the storytelling. On the one hand, law enforcements were victimized. On the other hand, the Roma people were portrayed stereotypically as the aggressors, who were unwilling to comply with the rules. For instance, the second-largest broadcaster over-dramatized the context of violence by associating it with the symbolism of a religious event “The peace of Easter is disturbed by the most violent street conflicts in recent years” (Antena 1, 2020b). Hence, the symbolism of the Orthodox Easter is conveyed under the noun “peace.” Consequently, the natural condition of Easter was disturbed by the street conflicts, whose unparallel violence is showcased as a series of events that disturbed the symbolism of the religious rite. Herein, the emphasis on Easter is important. As the academic literature on media and stereotypes suggests (Ross, 2019, p. 397), such categorization indirectly described the people disturbing the usual peace of the feast “as violent and ‘less’ than dominant groups”, i.e., loutish, uncultivated, etc.

Elsewhere, the accent fell on the damages caused by the riots of Roma. Thus, one daily reported an incident in Galati as “Scandal erupted, and cars were destroyed in a Roma community in Galati. Special forces intervened to resolve the conflict” (Mediafax.ro, 2020c). The intentional depiction of Roma as rioters reinforced the “othering” image in the public’s eyes, as Roma’s activities are attached to the value of destroyed goods. The discursive-performative practice of control is defined by the adjective “special” and the noun “forces.” Other dailies focused on the severity resulted from the conflicts with the police. Its processes included associating the sensationalism and violence from the events with the performance of control enforced by police. As to illustrate an example, one daily showcased the events as acts of revolt, “The Roma went on the attack. A gendarme was injured, and a car was vandalized” (Evenimentul Zilei, 2020b). The antagonistic nature of this journalistic account stressed the resulting processes of their mutiny by associating the violence exhorted on the gendarmes and the property of the law enforcements.

Other accounts stressed the gravity of Roma’s actions. Namely, one daily reported not only the violence resulting from the conflicts with the Roma but gave accounts of the disorder regarding both the local deputies and police forces – “Gendarmes attacked by Roma in Brasov. “They will destroy the mayor’s office. We risk being attacked on the highway” (Evenimentul Zilei, 2020c). In other instances, the media sensationalized the nature of the incidents by revealing to their audiences the shocking factor that exposed the violence from the Roma communities “Images captured during the Teliu scandal. One of the attackers arrested. The teenager, who beat a gendarme with a club, fled” (Mediafax.ro, 2020a). Elsewhere, the media’s headlines galvanized the public perception with a new account that underlined the results of violence in Roma communities “UPDATE video. Four people detained after the violence in Codlea/A gendarme and several policemen injured after being attacked by Roma with shovels” (Mediafax.ro, 2020b).

As the coverage continued depicting the antagonism between the Roma and police, by defining Roma’s identity through stereotypes, the media ultimately changed their narratives. At this stage, the logic of polarization adopted by the press moved from “narrowly stereotyped roles” (Ross, 2019, p. 397) to discursive-performative practices of control. Through their focus on the antagonism between the two protagonists, the media incentivized the police to reinstate a sense of order in the community and legitimize the police’s aggressive further acts. In other words, the stereotypical depiction of the Roma as violent and rioters created a fragmented society. This, in turn, acted as a prerequisite for a hegemonic articulation. To echo Laclau’s words (2001, p. 13), “hegemony will emerge precisely in a context dominated by the experience of fragmentation and by the indeterminacy of the articulations between different struggles and subject positions.” Take, for example, the case of DIGI24 (see Supplementary Image S1). This broadcaster covered the developments from Ţandarei with a title that said: “Ţăndărei is empty. The army has its eyes on the locals.” In another example, the third most-watched broadcaster presented the events from Ţăndărei in the following manner: “VIDEO | Ţăndărei, a militarized city. The risks of becoming the next red dot on the pandemic map” (Kanal D, 2020). Elsewhere, Romania TV covered the events unfolding in Ţăndărei with the following headline “The army intervenes in Ţăndărei where hundreds of Roma returning from abroad are not respecting the isolation” (Romania TV, 2020c). Other outlets reacted more decisively “Armed soldiers patrol the Roma neighborhoods of Ţăndărei. No one leaves, no one enters” (Aktual24.com, 2020). In the end, the media settled the discourse on the idea that control was reinstated to the detriment conferred by the image of the Roma people.

This study has surprisingly found that the media’s language vis-à-vis the Roma may be associated with a predisposition of the wider society to associate and understand criminality and lawlessness to be a Roma problem. Similarly, Erjavec (2001, p. 718) and (Sedláková, 2006) found that news report schema from Slovenia and Czechia centered on presenting the Roma through stereotypical frameworks. It was discovered in the analysis, that the written media covered more thoroughly the events than visual media. Some broadcasters like Romania TV used a more overt ethnic description of the COVID-19 events from Ţăndărei unlike other broadcasters. The written press made use more often of hyperboles to describe the events. Like in the study of Erjavec et al. (2000, p. 7), it was discovered in the present study that Roma-related coverages are highlighted if their actions affect the ethnic majority’s dominance. That is why, the hypothesis of this study is confirmed by the analysis and interpretation adopted in the current paper. The events from Ţăndărei, for instance, were underscored in the media because the historical lawlessness of Roma from that space was associated with their unwillingness to obey governmental decrees during COVID-19, thereby posing a threat for the dominant majority.

Another finding suggested that Roma’s social actions are reported through the use of a criminalizing language. This is confirmed by Romani studies literature who noticed the usage of a criminalized language (Thornton, 2014) to describe the Romani individuals, or when the issues of Roma criminality are attached as community values (Creţan and O’brien, 2019). This combination can shape collective identities and “distort the picture that audiences see of different groups” (Ross, 2019, p. 398). Representing vulnerable groups such as Roma with epithets that constructed violent contexts and unlawfulness inevitably positioned the Roma below the dominant majority. Such narrow and oversimplified characterizations can only radicalize even further the minority already ousted at the periphery of a society (c.f. Creţan and Powell, 2018). Similar to other studies that underlined patterns of stereotypes (Schneeweis, 2012; Creţan and Light, 2020), the current study showed that the Roma communities were characterized during the COVID-19 as violent, backward, promiscuous, and especially irresponsible. This may suggest that engraved and historical patterns of Roma stigmatization and anti-Roma narratives are dormant frameworks that are refreshed during crises. Comparative research (Creţan et al., 2020), who analyzed cases in Hungary, agree that the stigmatization of Roma has deep historical roots, which may affect policy advanced to mitigate the Roma stigmatization and advance empowerment (Berki et al., 2017).

Another unexpected finding that puzzled the researcher of this study was how the media’s discursive-performative practices of control apparently provided legitimacy for further assertive and disproportionate actions against the Roma communities (c.f. Matache and Bhabha, 2020). This study interpreted this unexpected finding as an opportunity for the authorities who wielded power to reinstate their “hegemonic articulation” (Laclau, 2001, p. 112) during a time of crisis on all social agents and not to lose political and civil credibility. Erjavec (2001, p. 718) found that media’s coverage of a scandal involving Roma in Slovenia was written to “offer the readers the representation that the majority population is defending itself from the minority Roma (thereby) it needed to maintain its dominance.” During the crisis from Ţăndărei, at the Roma’s expense, the authorities provided testimony of their strength, which, in turn, revalidated their credentials to continue performing control of COVID-19 elsewhere. However, such measures would be insufficient in the dynamics of performing control if it would not be for the media to acknowledge the “hegemonic articulation of power” (Laclau, 2001, p. 105) as opposed to the mechanism the “othering” “reinforced through the production of the stereotypes” (Ross et al., 2020). Oversimplifying Roma’s identity through stereotypes is no longer a self-sufficient incentive to enforce control. As studies showed previously (Creţan et al., 2020; Creţan and O’brien, 2019), the combination between stereotypes and a criminalized language that describes the Roma established the premises of justification in front of the dominant majority. Thus, by coupling the reproduction of stereotypes with the arbitrary categorization of crimes and violence as innate ethnic components, it justified the discursive-performative practices of control.

As shown in the material, the case of ţăndărei and other localities inhabited by Roma represented cases in which control was exercised by the media and performed by law enforcement. The developments from certain localities determined the balance between the two entities. Control of the pandemic remained mostly centralized throughout the pandemic, with the Government emitting Military Ordinances to control community transmission. The essence of the ordinances determined the identity of the people who augmented the crisis by connecting the space’s representation with their ethnicity. The same pattern is noticed in the Romani studies by the work of Creţan and Powell (2018). Without so many words, the focus of the Military Ordinances determined the people’s identity by naming the area but identifying the individuals through absence (c.f. Schröter and Taylor, 2017). Even so, the “social constructs” (Verkuyten, 2005) underlined in the media eventually constructed the people’s ethnicity. For instance, hitherto to Military Ordinance No. 7, which instituted total quarantine in Ţăndărei, the media already reported the increased rate of infection from Ţăndărei; and who was to blame for this cause (Adevarul.ro, 2020b; Recorder, 2020). Hence, the language of Military Ordinance No. 7, which focused on the space Ţăndărei, performed the identity of Roma through absence, as the context was already established by the media previously. By the time, the government acknowledged the situation, the media already highlighted who is threatening the ethnic majority.