94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci., 17 June 2021

Sec. Elections and Representation

Volume 3 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2021.663858

This article is part of the Research TopicPolitical Psychology: The Role of Personality in PoliticsView all 9 articles

Political tolerance is a core democratic value, yet a long-standing research agenda suggests that citizens are unwilling to put this value into practice when confronted by groups that they dislike. One of the most disliked groups, especially in recent times, are those promoting racist ideologies. Racist speech poses a challenge to the ideal of political tolerance because it challenges another core tenet of democratic politics – the value of equality. How do citizens deal with threats to equality when making decisions about what speech they believe should be allowed in their communities? In this article, we contribute to the rich literature on political tolerance, but focus on empathy as a key, and understudied, personality trait that should be central to how – and when – citizens reject certain types of speech. Empathy as a cognitive trait relates to one’s capacity to accurately perceive the feeling state of another person. Some people are more prone to worry and care about the feelings of other people, and such empathetic people should be most likely to reject speech that causes harm. Using a comparative online survey in Canada (n = 1,555) and the United States (n = 1627) conducted in 2017, we examine whether empathetic personalities - as measured by a modified version of the Toronto Empathy Scale - predict the tolerance of political activities by “least-liked” as well as prejudicially motivated groups. Using both a standard least-liked political tolerance battery, as well as a vignette experiment that manipulates group type, we test whether higher levels of trait empathy negatively correlate with tolerance of racist speech. Our findings show that empathy powerfully moderates the ways in which citizens react to different forms of objectionable speech.

Rights of free speech and assembly are central tenets of democratic politics, intended to ensure that a diversity of opinions is possible within democratic debate. Public opinion researchers starting with Stouffer (1955) foundational work have focused on the willingness of citizens to uphold these principles. While citizens within democracies tend to largely support such democratic ideals, a half a century of empirical work suggests that when confronted with a specific group with whom they disagree, support for the value of free speech plummets.

One of the reasons that citizens have a hard time with political tolerance, or “putting up with” speech they disagree with, is because a myriad of other considerations emerge when faced with a particularly objectionable group promoting obnoxious ideas. Will the speech promote actual violence? Does it erode other core democratic values like social tolerance and equality? Does it do real harm to other citizens? These considerations are at the core of two related literatures. Among political tolerance researchers, assessments of threat are central to understanding when citizens oppose speech. Relatedly, there is also a rich literature on the consequences of hate speech from both critical race scholars and legal scholars studying hate speech laws and court cases. Both these literatures suggest that some forms of speech do real and lasting harm, either because they directly promote violence or because they make it difficult for marginalized communities to live free of discrimination and on equal footing with their compatriots.

While we know a lot about the individual predictors of political (in)tolerance, much less work focuses on how individual dispositions may affect what types of speech are found objectionable. In this article, we focus specifically on explicitly racist groups and how they activate considerations of harm toward ethnic and racial minorities. We argue that those who have more empathetic personalities will be particularly sensitive to this type of harm and, in turn, be more likely to restrict speech by groups that promote social intolerance. To explore this question, we draw on a custom-designed online survey that was conducted in Canada (n = 1,555) and the United States (n = 1,627) in 2017. Using both a standard least-liked political tolerance battery, as well as a vignette experiment that manipulates group type, we test whether higher levels of trait empathy negatively correlate with the tolerance for racist speech. Our findings show that empathy powerfully moderates the ways in which citizens react to different forms of objectionable speech.

There is, of course, a rich literature on political tolerance attitudes dating back to the mid-twentieth century, including Stouffer’s (1955) classic studies on political tolerance [See Sullivan and Transue (1999) for review]. We know from past research that political elites, the more politically engaged (e.g., Stouffer 1955; Sullivan et al., 1982; Hinckley 2010) and the more educated (Bobo and Licari, 1989) consistently show higher levels of political tolerance. Other important predictors of intolerance include living in more rural or more Southern location in the United States., religious affiliation and religiosity, and being a woman (Stouffer 1955; Sullivan et al., 1982; Wilson, 1991; Marcus et al., 1995; Golebiowska, 1996; Cowan and Mettrick, 2002; Cowan and Khatchadourian, 2003)1. Yet, we know relatively little about the sources of support for hate speech restrictions, and whether support is 1) simply an expression of political intolerance (and thus explained by the traditional correlates of intolerance) or 2) has unique predictors that can distinguish between those who favor hate speech restrictions because they are willing to restrict all speech they do not like, vs. those who see a specific, democratic rationale for restricting speech such as hate speech.

Social tolerance, or openness to diversity, has been argued to be directly related to political tolerance. Stenner (2005) provides a compelling account that those prone to social tolerance also tend to be more politically tolerant. Yet at the same time, we know that appeals to social equality can make politically tolerant responses more difficult (Sniderman et al., 1996; Gibson, 1998; Gross and Kinder, 1998; Druckman, 2001; Cowan et al., 2002; Dow and Lendler, 2002). Experimental survey research in the United States tends to support the view that social tolerance concerns make political tolerance judgments more difficult. For example, several studies have shown that when people are primed about equality issues before being asked to make a tolerance judgment for racist groups, they are more likely to deny such groups civil liberties (Druckman, 2001; Cowan et al., 2002). Similarly, Harell (2010a) argues that legal norms restricting hate speech mean that citizens can – and do – distinguish between speech that is within the boundaries of democratic debate and that which is not. This suggests that when issues of racial equality are raised, people are more willing to curb the civil liberties of socially intolerant groups.

There are a small number of research articles that specifically consider the correlates of attitudes toward hate speech (Cowan and Mettrick, 2002; Cowan and Khatchadourian, 2003; Lambe, 2004). In addition, Wilson (1994) documented increased aggregate levels of tolerance for left-wing groups while right-wing groups did not see a parallel increase in the United States. Chong (2006) takes this analysis one step further, positing a distinction for attitudes toward exclusionary speech in his analysis of hate speech and the university experience. His analysis documents the trend among younger, more educated individuals to be less tolerant of hate speech than prior research would suggest, which he argues reflects a changing norm environment on university campuses.

If certain types of speech, especially speech that denigrates the inclusion of particular groups within society, are increasingly seen as outside the acceptable bounds of a free and democratic society, then what are the individual level dispositions that make people likely to see the specific harm caused by exclusionary discourses? Harell (2010b) shows that among young people, those who have more socially diverse friendship network are least tolerant of racist speech. One of the reasons, she argues, is that those in more socially diverse networks feel a connection to those who are targeted by such speech. Even when such speech does not attack an individual directly, the incentive to think about the potential harm of such speech for others should play an important role in one’s decision.

Both socially and in politics, the ability to empathize, to identify with the feelings of others, is recognized as an important behavioral catalyst (Griffin, et al., 1993; Gross, 2008; Andreoni et al., 2017). Campaigns for charitable donations attempt to induce generosity through empathic appeals based on individual need, suffering, or shared identity. In politics, interest groups often use empathetic frames such as support for the “hard-working” or “disadvantaged” to generate support for policies or reforms, and citizens in turn view the poor as more deserving of support when the poverty is viewed as outside of their control (Feldman and Zaller, 1992; Applebaum, 2001; Limbeck and Bullock, 2009). These frames are likely to be most successful among those who are prone to caring about others. For example, Feldman et al. (2020) find that people who are more empathetic tend to endorse more support for an individual welfare recipient and for government welfare policies except when it conflicts with a strong belief in individualism.

In functional terms, empathy is an adaptive characteristic designed to effectively communicate messages and to elicit social support or compliance (Redmond, 1989; Spreng et al., 2009). The ability to empathize requires that the receiver of the message can identify and relate to the experience, reasoning, and emotional state of the sender (Baron-Cohen and Wheelwright, 2004; Decety and Jackon, 2004; Zaki and Oschner, 2012; Zaki, 2014). Empathy is a complex and contingent process that is highly dependent on individual, environmental, and social factors; nonetheless, consistencies across these factors support an argument that empathy plays a meaningful role in the evaluation of social and political groups (Redmon, 1989; Decety, 2011; Zaki and Oschner, 2012).

For example, research shows that individuals high on trait empathy are disinclined to tolerate political groups perpetuating racist or discriminatory messages (Witenberg, 2007). Relatedly, Cowan and Khatchadourian (2003) find that empathetic personality is positively correlated with perceived harm of hate speech while analytic thinking is correlated with greater tolerance for groups whose message is associated with hate. Butrus and Witenberg (2013) investigate the personality traits predicting the tolerance of prejudicial attitudes toward different ethnic groups, and they find that empathetic concern is negatively correlated with intolerant speech and actions but not intolerant beliefs. Relatedly, Batson and colleagues (2002) find that inducing empathy toward a stigmatized group can lead to support for action to help them.

Nonetheless, an open question remains about when empathy occurs toward others who may be ethnically or racially different from oneself. This is because studies in political science and psychology consistently show that people are much more likely to empathize with members of their in-group than their out-group (Xu et al., 2009; Arceneaux, 2017) and that this tendency is intensified during social competition (Bruneau et al., 2017; Cikara, 2015; Hein et al., 2010; Cikara et al., 2011; Hackel et al., 2017)2. Empathy is also affected by perceptions and appraisals of an unknown other’s social proximity to oneself (Xu et al., 2009; Krienen et al., 2010). Finally, while studies show that social distance often inhibits the ability to empathize with others (Weisz and Zaki, 2018, p. 68), social proximity and shared experiences can induce empathy. For example, Sirin et al. (2016) found that Blacks and Latinos were more likely to recognize and support each other’s claims because of shared experiences of discrimination.

In the context of a civil liberties controversy, we suspect that those high on empathy will be more hostile to groups associated with racist speech and be more likely to empathize with the targets of such speech. This is, in part, because people are less likely to empathize with individuals or groups associated with negative affect (stress, fear, pain) (Redmond, 1989; Zaki, 2014) and because negative emotions are related to political intolerance (Halperin et al., 2014). Lab studies show that negative associations with groups’ actions or expressions result in counter-mimicry and the generation of opposing emotional responses, fear in response to out-group anger and aversion in response to out-group fear (van der Schalk et al., 2011). For example, Arceneaux finds that inducing anxiety in participants reduces their willingness to assist members of a socio-political outgroups in need of public assistance (Arceneaux, 2017). By contrast, those high on empathy will be open to appeals made by groups expressing that they themselves are the target of harmful speech or activity. Generalized to the study of political tolerance, we hypothesize that individuals higher on trait empathy should be less tolerant toward actions by political groups that are strongly associated with affective emotions – fear, threat, violence – and more tolerant of groups expressing that they themselves are targets of threats and violence. Neo-Nazis, White Supremacists and other groups whose motivation is exclusion and who are often associated with histories of racial violence will be viewed as threatening. The Black Lives Matter movement, on the other hand, which calls for racial justice and inclusion, will be viewed as relatively less threatening.

In sum, we are interested in testing the relationship between empathy and political intolerance of different types of speech. We do this by relying on a survey experiment about three political groups holding a political march in one’s community. The three groups manipulated were 1) White Supremacists, 2) their least-liked political group or 3) Black Lives Matter activists. We predict that for groups associated with prejudice and violence toward minorities, empathy will be negatively correlated with tolerance for their political march. Specifically, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 1: In comparison to Black Lives Matter, higher levels of empathy will be negatively correlated with the tolerance for a political march by White Supremacist or least-liked groups.

Hypothesis 2: In comparison to Black Lives Matter, higher levels of empathy will be positively corrected with the expectation of harm to others following the political march by White Supremacist or least-liked groups.

The data for this paper were collected from an online survey conducted in the United States (n= 1,646) and Canada (n = 1,627). The study was in the field between January 6 and February 7, 2017. Importantly, the data were collected before significant shifts in public opinion occurred regarding the groups evaluated by participants in our study. Public opinion in the US regarding the Black Lives Matter movement was mixed in early 2017, and high-profile protests by White supremacists in the US had not yet occurred. A number of polls suggest that public support for Black Lives Matter in the US did increase but well after our study was in the field3.

In Canada, the questionnaire was available in both English and French. Qualtrics, an online survey research firm, administered the data collection. Respondents were selected from among those who had registered to participate in online surveys through several different organizations. The sample providers offered various incentives to participate (equivalent to $1 US). The average time to complete the survey was 22 min. During data collection responses were not forced. In our analyses we drop all participants with missing observations on our dependent or independent variables, leaving a final sample of (n = 1,627) in the United States and (n = 1,555) in Canada.

A quota system based on age, gender, and education was used to screen potential respondents, which resulted in samples that reflect these measured population parameters in each country. In addition, a language quota was applied in Canada. The final US sample, after excluding missing data, was 51% female, 75% white, a median age of “30–39”, and 39% had a post-secondary education. The Canadian sample was 51% female, 81% white, median age of “40–49”, and 55% had a post-secondary education. Mean ideological score on a 7-point Likert scale is 4.34 in the US and 4.06 in Canada. Among Canadians in the sample, about 65% reported English as their primary language, 30% selected French, and 5% indicated “other”4. The samples were reasonable representative of the geographic diversity of each country. In the US, the sample matches the regional distribution of the country (18% Northeast, 22% Midwest, 37% South, 23% West). In Canada, the sample over-represented Quebec (32%), and slightly under-represented the Western provinces (25%) and Ontario (24%). The representation in the Eastern provinces (8%) and the North (less than 1%) were similar to their population. The data were not weighted after cases with missing data were dropped as there was no relationship between missing items and any of the quota variables.

The survey was designed to explore the relationship between individual predispositions and support for civil rights and included both a traditional least-liked group battery as well as an experimental vignette about the rights of groups to protest.

Least-liked Group: Respondents were asked to evaluate on a (0–10) dislike-like scale six groups: 1) neo-Nazis; 2) Christian fundamentalists; 3) extreme-right activists; 4) radical Muslims; 5) gay rights activists; and 6) feminists. Respondents also indicated the group, from among the six, that they liked the least. These six groups were selected to provide variation on left – right ideological association, as well as variation on racial, religious, and social group affiliation5. The group selected as least-liked among the list is used subsequently in the experimental vignette.

Experimental Vignette: Participants completed a thought experiment involving a fictional protest group looking to conduct a march in the participant’s community. We utilize this approach as several studies in the political tolerance literature (e.g., Gibson 1998) have shown it useful for varying elements of context within a survey experiment6. The full text of the vignette was:

Imagine a group of (least-liked group, Black Lives Matters activists, White Supremacists) are organizing a march in your community. The group expects (a handful, a thousand) protesters to travel to your area to attend. In the past, groups like this (have been accused of violent confrontations with bystanders, have been accused of shouting ugly words at bystanders, held peaceful marches in communities like this).

We randomly assigned participants into different treatments in which we manipulated the protest group’s characteristics on three dimensions. First, we randomly assigned the type of group: the indicated least-liked group from a prior question in the survey, and two groups with race-based political claims, one linked to equality claims for Blacks and one linked to social intolerance and racism. In addition to the group type, we varied two potential measures of threat, the size of the gathering (a small vs. a large gathering) and level of past violence by similar groups (peaceful, verbal aggression, and physical aggression).

After reading the condition, participants were asked on a four-point scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree “Should this group be allowed to hold the march?” Higher levels of agreement indicate more political tolerance for the group, our main dependent variable in the analysis.

Participants were also asked to indicate “What is the likelihood that the march will result in” the following five outcomes: 1) more support for the group’s beliefs; 2) hurt feelings in the community; 3) property damage; 4) violence; 5) more discrimination. Each of these items is assessed on a 5-point scale from very unlikely to very likely. Using four of these five items we construct a scale that measures individuals’ expectation of potential harm following the political march. To construct this scale, all five items are included in an exploratory factor analysis with an oblimin rotation. Four of the five items (hurt feelings, property damage, violence, more discrimination) show strong single factor loadings of greater than 0.70; these four items are retained and combined to form a single scale (0–16). The results of the factor analysis are listed in the online supplementary materials (pg. 14–15 in the Online Supplementary Material).

Empathy as a Trait: Our main independent variable of interest was asked prior to the experimental vignette and captures people who are prone to caring about the feelings of other people. We refer to this as having a more empathetic personality, which is measured using a subset of four questions regarding emotional empathy from the Toronto Empathy Questionnaire such as “I enjoy making other people feel better” and disagreeing with statements such as “I am not interested in how other people feel” (Spreng et al., 2009). These four questions form a scale from 0 to 12. However, to compensate for less than five percent of responses in the first five categories, corresponding to very low empathy, we collapse the bottom five categories to create a new scale which runs from 1 to 7.

It is important to note that the emotion of empathy was often treated similarly to psychological characteristics like personality. Beginning in the 1960s, a number of scales were developed which scored individuals as high or low on “trait” empathy. Since the development of the Toronto Empathy Questionnaire (TEQ) in 2009, research in psychology has distinguished between empathy as a trait-based disposition and empathy as an experience or emotional state. According to recent definitions, empathy itself is an emotional experience which is best understood in terms of “when and how not either or” (Zaki and Ochsner, 2012). Consequently, scales like the TEQ do not directly measure empathy, but instead capture important dispositional tendencies or subprocesses which influence the likelihood of empathetic experience such as cognitive reflection, perspective taking, or sympathy. As a result, we use the terminology of empathetic personality to indicate that we are measuring a dispositional tendency to feel empathy toward others, but not the emotion of empathy itself. In particular, the items we use from the TEQ are designed to measure the dispositional tendency to experience emotional empathy, and not cognitive perspective taking.

Analysis: Results of the experiment are analyzed using an Ordered Logistic Regression with robust confidence intervals where 1) political tolerance of the march and 2) the harm scale are the dependent variables for H1 and H2 respectively. We utilize ordered logistic regression because our main dependent variable has only four categories and these categories do not form a true continuous scale. For the sake of simplicity, and because the results do not change when using ordinary least squares regression, we also use ordered logistic regression to analyze the harm scale. In addition, we provide in the appendix additional models without the interaction term, as well as a model that includes additional interaction terms between Empathy and the other two treatments variables: size and level of harm of each protest group. These additional interactions control for the sensitivity of empathetic processes to threat. The inclusion of these additional control interactions does not mediate the significance of results reported in the main text. All models also include demographic controls for age, education, race, gender, and ideology (see coding in the Online Supplemental Materials). Ideology is included as a control variable as previous research shows that a conservative ideological orientation may correlate with lower levels of empathetic behavior as well as greater tolerance for right-wing political groups (i.e., neo-Nazi’s and White Supremacists) in the United States (Sullivan et al., 1982; Sidanus et al., 2013; Feldman et al., 2015; Hasson et al., 2018) and in Canada (e.g., Loewen et al., 2019). Finally, the statistical results are reported independently for each country.hl.

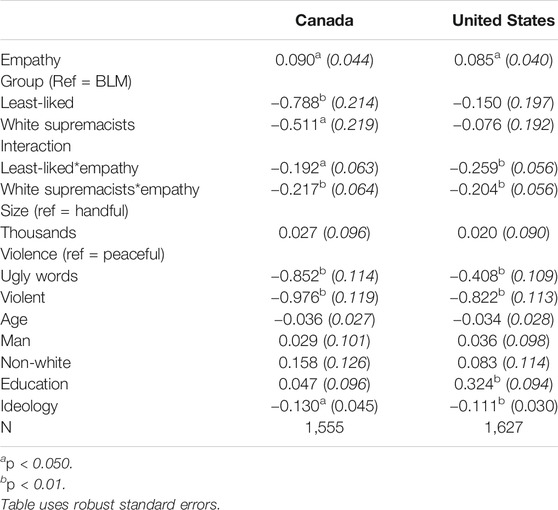

Table 1 presents the core test of hypothesis 1, which includes the interaction between empathetic personality and group type on support for a public march. We analyze the Canadian and US samples separately. As expected, the interaction between group type and empathetic personality is negative for White Supremacists compared to Black Lives Matter (BLM) activists. We find a similar effect for the least-liked group. In addition, we find no direct effect of protest size, but respondents did react to the level of violence treatment. When presented with both groups with histories of verbal and physical violence, the tolerance of the march is lower. These effects are very similar in both Canada and the US.

TABLE 1. Predicting effect of group type and empathy on support for political march (ordered logistic regression).

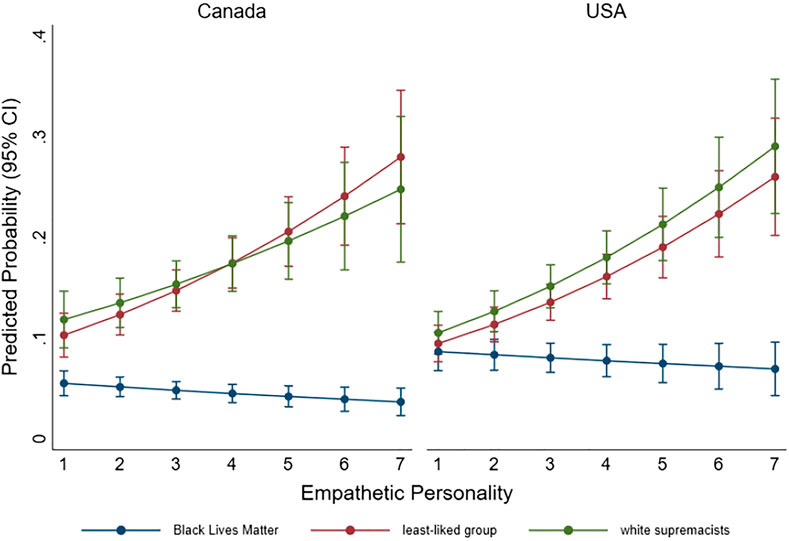

Figure 1 illustrates the impact of group type based on empathy. We show the predicted probability of opposing or supporting the march based on levels of empathy and group type. For instance, the left-most panel makes clear that empathy was related to less opposition to BLM protestors (indicated by the downward slope of the estimation), whereas for both White Supremacists and the respondent’s least-liked group the slope is positive, indicating greater opposition.

FIGURE 1. Effect of Empathetic Personality on Support for March by Group Note: The figure displays the predicted probability of each level of agreement or disagreement in response to the statement, “This group should be allowed to hold a march,” and uses robust standard errors with 95% CI based on models in Table 1.

Interestingly, those lowest on empathy make no real distinction when presented with different types of groups in Canada and the US, but we see an important divergence at the upper end of the empathy scale. While the patterns are similar in the two countries, it is also worth noting that overall levels of opposition are higher in Canada than in the US for two of the three group types (White Supremacists and least-liked group), which may well reflect differences in traditions toward free speech, with racist speech explicitly protected by the First Amendment in the US, whereas Canada has traditionally balanced free speech rights against other values.

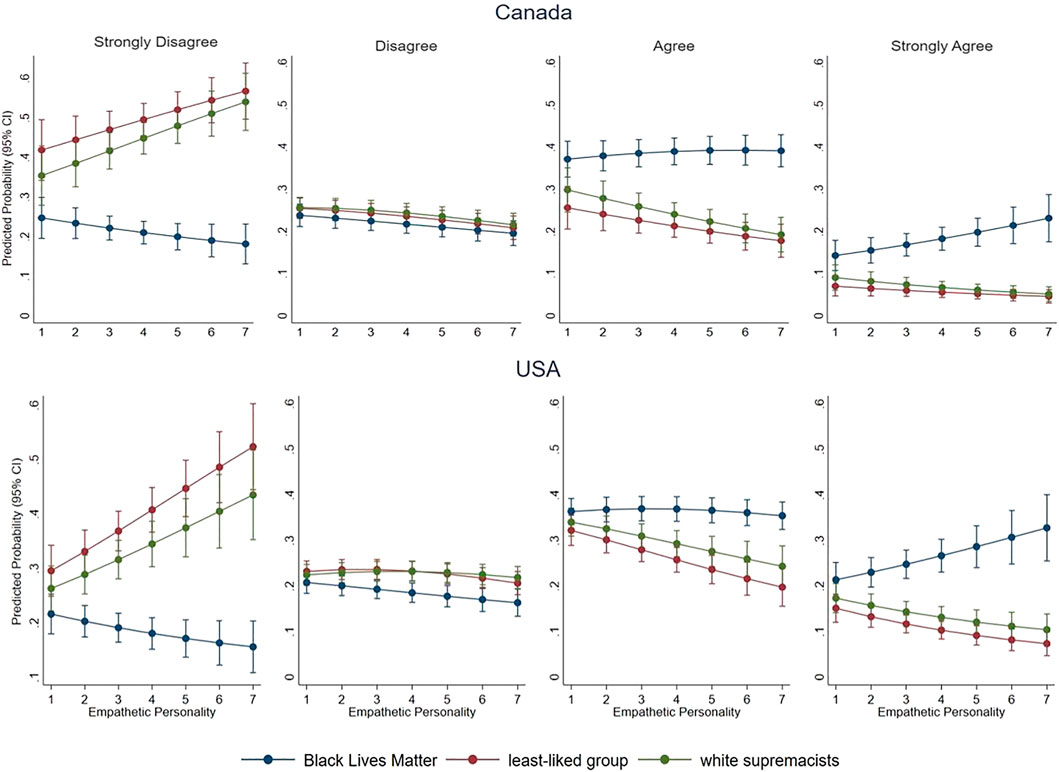

The key hypothesis, then, is supported: individuals with a more empathetic personality, a disposition toward empathizing with the feelings of others, have less tolerance toward political groups engaged in exclusionary and potentially harmful speech. Yet, this also raises an additional question. Why does empathy reduce tolerance for least-liked groups? The answer in part is drawn from the group that was most commonly selected. In total, 40% of Canadians and 44% of Americans selected neo-Nazis as their least-liked group. The second most selected group was radical Muslims, and together these two groups are selected by the vast majority of respondents in each sample (81.89% of participants identify one of these two groups as their least-liked).

In Figure 2, we drop all respondents in the least-liked treatment who selected a group other than these two (n = 72: Canada; n = 111: US), and we estimate separate effects for each group (Full models are available in the supplemental materials.) The group type variable thus becomes a four-category discrete variable: 1) BLM, 2) Radical Muslims, 3) neo-Nazi’s, 4) White Supremacists. Neo-Nazis and White Supremacists are expected to function similarly, both representing exclusionary groups with explicit racist connotations.

FIGURE 2. Effect of Empathetic Personality on Opposing March by Group, four categories Note: Panel 2 displays the predicted probability of selecting “Strongly disagree” and uses robust standard errors with 95% confidence intervals. Responses “Moderately disagree, Moderately agree, Strongly agree” are omitted. Full models available in Tables 3 and 4 of the Online Supplemental Materials.

While not definitive, teasing out the least-liked group provides additional support for our argument that empathy interacts specifically with exclusionary groups associated with harmful speech. The interaction for neo-Nazis is significant, and Figure 2 illustrates that the increase in the predicted probability of opposing a march by this group as empathy goes from the lowest to highest level. In both the US and Canada, the interaction term is significant and similar to the White Supremacist treatment. Radical Muslims, in contrast, are clearly not tolerated, with relatively high levels of predicted opposition in both countries. In Canada, the interaction between empathetic personality and seeing Radical Muslims (vs. BLM) in the vignette was just above conventional levels of statistical significance. In the US, though, the interaction is statistically significant. This suggests that empathy is linked to viewing the speech of radical Muslims as similarly harmful to that of neo-Nazis and White Supremacists within the American public.

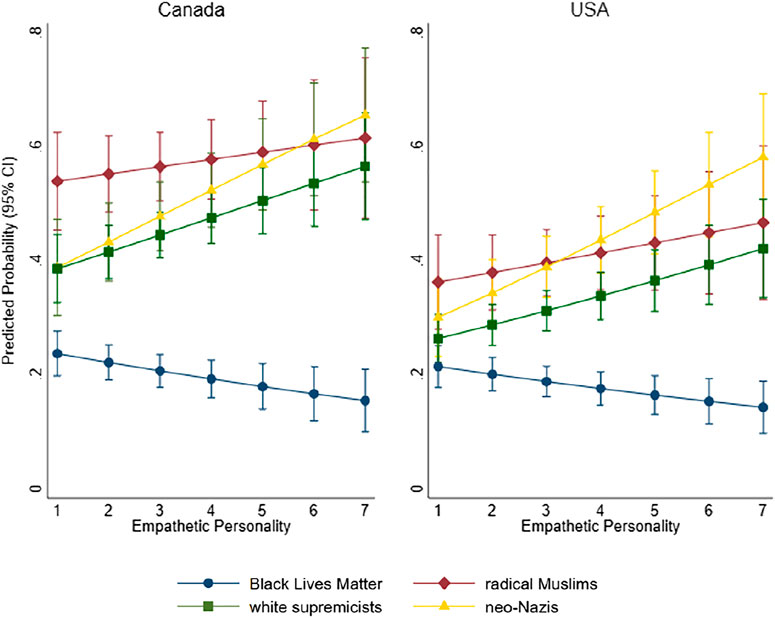

We take this to indicate that empathetic people are particularly likely to oppose groups expected to engage in harmful speech in line with hypothesis 1. Do people predisposed toward empathy perceive more potential for harm from such groups? Our second hypothesis is that higher levels of empathy will also be related to perceptions of the potential harm caused by exclusionary speech, which we are able to measure with our four-item harm index that was asked post treatment. An exploratory factor analysis was performed to combine these items. In general, respondents were more concerned about harm when confronted with both White Supremacists and their least-liked group. In Canada and the US, the mean scores on the harm index for Black Lives Matter was 8.76 (SD = 3.92) and 9.89 (SD = 4.21) as compared to the least-liked group 11.36 (SD = 3.47) and 11.32 (SD = 3.39), and White Supremacists 11.41 (SD = 3.58) and 11.35 (SD = 3.47).

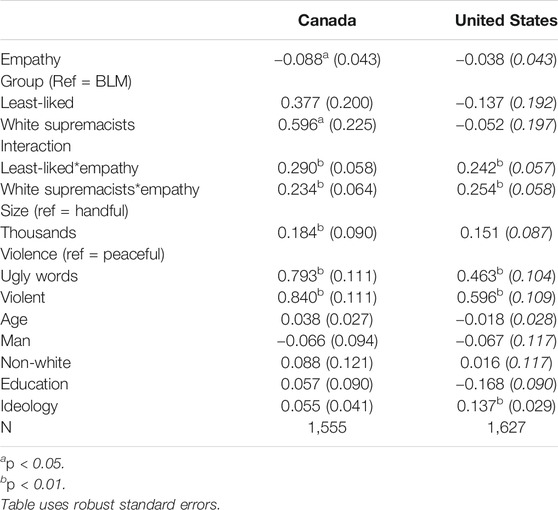

Our interest is in whether these effects are moderated by a tendency toward empathy. Table 2 provides the base model to test the moderating impact of empathy on harm perception based on the type of group involved in the protest activity. Like our findings for hypothesis 1, empathy drives up perceptions of harm when confronted with White Supremacists or a least-liked group compared to BLM.

TABLE 2. Predicting effect of group type and empathy on perception of harm (ordered logistic regression).

We illustrate these effects in Figure 3. These results are not meaningfully different from the result of the individual scale items and reach significance at or above the 95% confidence level. Each individual item in the four-item harm scale is analyzed separately and presented in the supplementary materials (see Online Supplemental Materials Tables 7–14).

FIGURE 3. Effect of Empathetic Personality on Expectation of Harm Resulting from a Political March Note: Figure displays the predicted probability of selecting “Very likely” for each of the four items measuring harm perception and uses robust standard errors with 95% confidence intervals. Full models available in Tables 5, 6 in the Online Supplemental Materials.

In this paper, we examined the relationship between empathetic personality and tolerance for political activities by exclusionary political groups. Consistent with our hypotheses, we find that higher levels of empathetic personality are negatively correlated with tolerance toward these groups. Importantly, this occurred to a similar degree in both Canada and the US, which have different legal approaches to balancing liberty and equality. On this basis, we conclude that group-based objections to political activity designed to promote violence and hatred are distinct from other considerations that limit political tolerance. This finding is consistent with previous research which finds that individuals with empathetic dispositions are more likely to oppose extending freedom of speech to attitudes or actions which discriminate based on ethnicity, gender, or sexual orientation (Battson et al., 2002; Cowan and Khatchadourian, 2003; Witenberg, 2007; Butrus and Witenberg, 2013).

This research also extends the literature on political tolerance attitudes. While prior research has shown the importance of group threat in making tolerance judgments [e.g., Petersen et al. (2010)], far less is known about the origins of threat perceptions. Our study demonstrates that those high in empathy are especially likely to perceive the public activity of racist groups as harmful to others because of their association with violence and discrimination. Empathy was also associated with lower perceived threat when evaluating a group advocating for racial justice and inclusion. We suggest this occurs because of an emotional reaction that is distinct from the cognitive concerns typically examined in studies on threat or attitude change [e.g., Gibson (1998)]. Future research could attempt to further distinguish between the affective dimensions of empathetic responses and more typically measured threat perceptions such as group size and potential for influence.

More broadly, our findings point to the importance of empathy in the formation of political attitudes. Despite the limited and contingent nature of empathetic responses [e.g., Sirin et al. (2016); Arceneaux (2017)], we found that dispositional empathy shaped reactions to a (hypothetical) civil liberties controversy involving groups seeking to limit or expand social tolerance. In diverse democracies, in which racial, ethnic or other minorities are ascribed outsider status by exclusionary political movements, empathy may play an increasingly central role in the dynamics of public opinion. Additional research should examine the contexts in which empathy across group boundaries occurs and impacts other political attitudes, such as toward policing, language rights and religious freedoms.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Comité d’approbation éthique, Université du Québec à Montréal. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

AH and RH contributed to the conception of the design of the study and collected the data. JM performed the statistical analyses. AH and JM wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

The data was collected with a grant awarded to AH from the Fonds de recherche du Québec - Société et Culture (#192786), in addition to support from the Université du Québec through their strategic research chair program. JM was supported during the writing of this article from grants awarded to AH from the Fonds de recherche du Québec - Société et Culture (#196408) and the Canadian Social Science and Humanities Research Council (#435-2019-0989).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2021.663858/full#supplementary-material

1Other work e.g., Sheffer (2020) has used an intergroup approach in the Canadian political context.

2One exception to this trend is a study on immigration and humanitarian concern by Newman et al. (2015) who finds a positive correlation between empathy and out-group support (support for immigration) when the issue is framed as a humanitarian concern.

3For instance, see https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/07/08/how-americans-view-the-black-lives-matter-movement/and https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/06/10/upshot/black-lives-matter-attitudes.html. The authors thank an anonymous reviewer for this suggestion.

4According to the 2011 Canadian census, about 21% of Canadians have a maternal language other than English or French but note that 6% speak a language other than English or French as their primary home language. Statistics Canada, downloaded Mar. 24, 2017, http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census>recensement/2011/as>sa/98>314>x/98>314>x2011001>eng.cfm.

5Respondents were then asked to indicate if each of the six groups should be allowed to 1) talk on television about their views and 2) hold a peaceful march in your neighborhood. We reserved these items for a separate analysis.

6See also Forward et al. (1976) as providing justification for the “role-enactment” approach as opposed to using deception in experimental research.

Andreoni, J., Rao, J. M., and Trachtman, H. (2017). Avoiding the Ask: A Field experiment on Altruism, Empathy, and Charitable Giving. J. Polit. Economy 125 (3), 625–653. doi:10.1086/691703

Applebaum, L. D. (2001). The Influence of Perceived Deservingness on Policy Decisions Regarding Aid to the Poor. Polit. Psychol. 22 (3), 419–442. doi:10.1111/0162-895x.00248

Arceneaux, K. (2017). Anxiety Reduces Empathy toward Outgroup Members but Not Ingroup Members. J. Exp. Polit. Sci. 4 (1), 68–80. doi:10.1017/xps.2017.12

Baron-Cohen, S., and Wheelwright, S. (2004). The Empathy Quotient: an Investigation of Adults with Asperger Syndrome or High Functioning Autism, and normal Sex Differences. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 34 (2), 163–175. doi:10.1023/b:jadd.0000022607.19833.00

Batson, C. D., Chang, J., Orr, R., and Rowland, J. (2002). Empathy, Attitudes, and Action: Can Feeling for a Member of a Stigmatized Group Motivate One to Help the Group?. Pers Soc. Psychol. Bull. 28 (12), 1656–1666. doi:10.1177/014616702237647

Bobo, L., and Licari, F. C. (1989). Education and Political Tolerance: Testing the Effects of Cognitive Sophistication and Target Group Affect. Public Opin. Q. 53 (3), 285–308. doi:10.1086/269154

Bruneau Emile, G., Cikara, M., and Saxe, R. (2017). Parochial Empathy Predicts Reduced Altruism and the Endorsement of Passive Harm. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 8 (8), 934–942.

Butrus, N., and Witenberg, R. T. (2013). Some Personality Predictors of Tolerance to Human Diversity: The Roles of Openness, Agreeableness, and Empathy. Aust. Psychol. 48 (4), 290–298. doi:10.1111/j.1742-9544.2012.00081.x

Chong, D. (2006). Free Speech and Multiculturalism in and Out of the Academy. Polit. Psychol. 27 (1), 29–54. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9221.2006.00448.x

Cikara, M., Botvinick, M. M., and Fiske, S. T. (2011). Us versus Them. Psychol. Sci. 22 (3), 306–313. doi:10.1177/0956797610397667

Cikara, M. (2015). Intergroup Schadenfreude: Motivating Participation in Collective Violence. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 3, 12–17. doi:10.1016/j.cobeha.2014.12.007

Cowan, G., and Khatchadourian, D. (2003). Empathy, Ways of Knowing, and Interdependence as Mediators of Gender Differences in Attitudes toward Hate Speech and Freedom of Speech. Psychol. Women Q. 27, 300–308. doi:10.1111/1471-6402.00110

Cowan, G., and Mettrick, J. (2002). The Effects of Target Variables and Settting on Perceptions of Hate Speech1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 32 (2), 277–299. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2002.tb00213.x

Cowan, G., Resendez, M., Marshall, E., and Quist, R. (2002). Hate Speech and Constitutional Protection: Priming Values of Equality and Freedom. J. Soc. Isssues 58 (2), 247–263. doi:10.1111/1540-4560.00259

Decety, J., and Jackson, P. L. (2004). The Functional Architecture of Human Empathy. Behav. Cogn. Neurosci. Rev. 3 (2), 71–100. doi:10.1177/1534582304267187

Decety, J. (2011). The Neuroevolution of Empathy. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 1231 (1), 35–45. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06027.x

Dow, E., and Lendler, M. (2002). Civil Liberties and the Moderate Thought Police. Apsc 35, 549–553. doi:10.1017/s1049096502000823

Druckman, J. N. (2001). On the Limits of Framing Effects: Who Can Frame?. J. Polit. 63 (4), 1041–1066. doi:10.1111/0022-3816.00100

Feldman, S., Huddy, L., Wronski, J., and Lown, P. (2020). The Interplay of Empathy and Individualism in Support for Social Welfare Policies. Polit. Psychol. 41 (2), 343–362. doi:10.1111/pops.12620

Feldman, S., and Zaller, J. (1992). The Political Culture of Ambivalence: Ideological Responses to the Welfare State. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 36 (1), 268–307. doi:10.2307/2111433

FeldmanHall, O., Dalgleish, T., Evans, D., and Mobbs, D. (2015). Empathic Concern Drives Costly Altruism. Neuroimage 105, 347–356. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.10.043

Forward, J., Canter, R., and Kirsch, N. (1976). Role-enactment and Deception Methodologies? Alternative Paradigms?. Am. Psychol. 31 (8), 595–604. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.31.8.595

Gibson, J. L. (1998). A Sober Second Thought: An experiment in Persuading Russians to Tolerate. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 42 (3), 819–850. doi:10.2307/2991731

Golebiowska, E. A. (1996). The "Pictures in Our Heads" and Individual-Targeted Tolerance. J. Polit. 58 (4), 1010–1034. doi:10.2307/2960147

Griffin, M., Babin, B. J., Attaway, J. S., and Darden, W. R. (1993). Hey You, Can Ya Spare Some Change? The Case of Empathy and Personal Distress as Reactions to Charitable Appeals. Adv. Consumer Res. 20, 508–514.

Gross, K. A., and Kinder, D. R. (1998). A Collision of Principles? Free Expression, Racial Equality and the Prohibition of Racist Speech. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 28 (3), 445–471. doi:10.1017/s0007123498000349

Gross, K. (2008). Framing Persuasive Appeals: Episodic and Thematic Framing, Emotional Response, and Policy Opinion. Polit. Psychol. 29 (2), 169–192. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9221.2008.00622.x

Hackel, L. M., Zaki, J., and Van Bavel, J. J. (2017). Social Identity Shapes Social Valuation: Evidence from Prosocial Behavior and Vicarious Reward. Soc. Cogn. affective Neurosci. 12 (8), 1219–1228. doi:10.1093/scan/nsx045

Halperin, E., Pliskin, R., Saguy, T., Liberman, V., and Gross, J. J. (2014). Emotion Regulation and the Cultivation of Political Tolerance. J. Conflict Resolution 58 (6), 1110–1138. doi:10.1177/0022002713492636

Harell, A. (2010b). Political Tolerance, Racist Speech and the Influence of Peer Networks. Soc. Sci. Q. 91 (2), 723–739. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6237.2010.00716.x

Harell, A. (2010a). The Limits of Tolerance in Diverse Societies: Hate Speech and Political Tolerance Norms Among Youth. Can. J. Polit. Sci. 43 (3), 407–432. doi:10.1017/s0008423910000107

Hasson, Y., Tamir, M., Brahms, K. S., Cohrs, J. C., and Halperin, E. (2018). Are Liberals and Conservatives Equally Motivated to Feel Empathy toward Others? Pers Soc. Psychol. Bull. 44 (10), 1449–1459. doi:10.1177/0146167218769867

Hein, G., Silani, G., Preuschoff, K., Batson, C. D., and Singer, T. (2010). Neural Responses to Ingroup and Outgroup Members' Suffering Predict Individual Differences in Costly Helping. Neuron 68 (1), 149–160. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.003

Hinckley, R. A. (2010). Personality and Political Tolerance: The Limits of Democratic Learning in Postcommunist Europe. Comp. Polit. Stud. 43 (2), 188–207. doi:10.1177/0010414009349327

Krienen, F. M., Tu, P.-C., and Buckner, R. L. (2010). Clan Mentality: Evidence that the Medial Prefrontal Cortex Responds to Close Others. J. Neurosci. 30, 13906–13915. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.2180-10.2010

Lambe, J. L. (2004). Who Wants to Censor Pornography and Hate Speech?. Mass Commun. Soc. 7 (3), 279–299. doi:10.1207/s15327825mcs0703_2

Limbert, W. M., and Bullock, H. E. (2009). Framing U.S. Redistributive Policies: Tough Love for Poor Women and Tax Cuts for Seniors. Analyses Soc. Issues Public Pol. 9 (1), 57–83. doi:10.1111/j.1530-2415.2009.01189.x

Loewen, P., Cochrane, C., and Arsenault, G. (2019). Empathy and Political Preferences. Retrieved from https://www.princeton.edu/csdp/events/Loewen03162017/Empathy-and-Political-Preferences-Jan-2017.pdf

Marcus, G. E., Sullivan, J. L., Theiss-Morse, E., and Wood, S. (1995). With Malice toward Some: How People Make Civil Liberties Judgments, Cambridge Studies in Political Psychology and Public Opinion. Cambridge; New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Newman, B. J., Hartman, T. K., Lown, P. L., and Feldman, S. (2015). Easing the Heavy Hand: Humanitarian Concern, Empathy, and Opinion on Immigration. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 45 (3), 583–607. doi:10.1017/s0007123413000410

Petersen, M., Slothuus, R., Stubager, R., and Togeby, L. (2010). Freedom for All? the Strength and Limits of Political Tolerance. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 41, 581–597. doi:10.1017/s0007123410000451

Redmond, M. V. (1989). The Functions of Empathy (Decentering) in Human Relations. Hum. relations 42 (7), 593–605. doi:10.1177/001872678904200703

Sheffer, L. (2020). Partisan In-Group Bias before and after Elections. Elect. Stud. 67, 102191. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2020.102191

Sidanius, J., Kteily, N., Sheehy-Skeffington, J., Ho, A. K., Sibley, C., and Duriez, B. (2013). You're Inferior and Not worth Our Concern: The Interface between Empathy and Social Dominance Orientation. J. Pers 81 (3), 313–323. doi:10.1111/jopy.12008

Sirin, C. V., Valentino, N. A., and Villalobos, J. D. (2016). Group Empathy Theory: The Effect of Group Empathy on US Intergroup Attitudes and Behavior in the Context of Immigration Threats. J. Polit. 78 (3), 893–908. doi:10.1086/685735

Sniderman, P. M., Fletcher, J. F., Russell, P. H., and Tetlock, P. (1996). The Clash of Rights: Liberty, Equality, and Legitimacy in Pluralist Democracy. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Spreng*, R. N., McKinnon*, M. C., Mar, R. A., and Levine, B. (2009). The Toronto Empathy Questionnaire: Scale Development and Initial Validation of a Factor-Analytic Solution to Multiple Empathy Measures. J. Personal. Assess. 91 (1), 62–71. doi:10.1080/00223890802484381

Stouffer, S. A. (1955). Communism, Conformity, and Civil Liberties: A Cross-Section of the Nation Speaks its Mind. New York: Doubleday.

Sullivan, J. L., and Transue, J. E. (1999). The Psychological Underpinnings of Democracy: A Selective Review of Research on Political Tolerance, Interpersonal Trust, and Social Capital. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 50 (1), 625–650. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.50.1.625

Sullivan, J., Piereson, J., and Marcus, G. (1982). Political Tolerance and American Democracy. Chicago: University of Chicago.

Van Der Schalk, J., Fischer, A., Doosje, B., Wigboldus, D., Hawk, S., Rotteveel, M., et al. (2011). Convergent and Divergent Responses to Emotional Displays of Ingroup and Outgroup. Emotion 11 (2), 286–298. doi:10.1037/a0022582

Weisz, E., and Zaki, J. (2018). Motivated Empathy: a Social Neuroscience Perspective. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 24, 67–71. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.05.005

Wilson, T. C. (1994). Trends in Tolerance toward Rightist and Leftist Groups, 1976-1988: Effects of Attitude Change and Cohort Succession. Public Opin. Q. 58 (4), 539–556. doi:10.1086/269446

Wilson, T. C. (1991). Urbanism, Migration, and Tolerance: A Reassessment. Am. Sociological Rev. 56, 117–123. doi:10.2307/2095677

Witenberg, R. T. (2007). The Moral Dimension of Children's and Adolescents' Conceptualisation of Tolerance to Human Diversity. J. Moral Edu. 36 (4), 433–451. doi:10.1080/03057240701688002

Xu, X., Zuo, X., Wang, X., and Han, S. (2009). Do You Feel My Pain? Racial Group Membership Modulates Empathic Neural Responses. J. Neurosci. 29, 8525–8529. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.2418-09.2009

Zaki, J. (2014). Empathy: A Motivated Account. Psychol. Bull. 140 (6), 1608–1647. doi:10.1037/a0037679

Keywords: political tolerance, empathy, hate speech, racist speech, public opinion, Canada, United States, political intolerance

Citation: Harell A, Hinckley R and Mansell J (2021) Valuing Liberty or Equality? Empathetic Personality and Political Intolerance of Harmful Speech. Front. Polit. Sci. 3:663858. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.663858

Received: 03 February 2021; Accepted: 31 May 2021;

Published: 17 June 2021.

Edited by:

Scott Pruysers, Dalhousie University, CanadaReviewed by:

Jean-François Daoust, University of Edinburgh, United KingdomCopyright © 2021 Harell, Hinckley and Mansell. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Allison Harell, aGFyZWxsLmFsbGlzb25AdXFhbS5jYQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.