- The Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter School for Peace and Conflict Resolution, George Mason University, Arlington, VA, United States

Over the past couple of decades, “new” state actors, such as Brazil, China, Russia, India, Turkey, and countries of the Arab Gulf, have been playing an increasingly prominent role in assistance provision to conflict-affected states. Skeptical of the liberal peace-building model, they have emphasized supporting economic development and avoided promoting political reforms, viewing them as too interventionist in domestic affairs of conflict-affected states. Rather, they have emphasized solidarity, cooperation, mutual support, and respect for state sovereignty; and they are committed to non-intervention norms. However, the foreign policies of “new” state actors have been far from static. This article argues that these norms mask more complex relationships between “new” state actors and conflict-affected states. Historically, the “new” actors have tended to adhere less to non-intervention norms in their immediate neighborhood. Now, as they become more deeply engaged with countries emerging out of violent conflict, have come to aspire playing more prominent global roles, and the competition among them has risen, their adherence to principles of non-interference is under strain and policies regarding issues of peace and security are shifting.

Introduction

In the last two decades, the international donor landscape has witnessed significant evolution. In particular, new actors such as China, Brazil, India, Russia, Turkey, and South Africa, among others, have expanded their relationships with conflict-affected states, increasing their investments and trade relationships while also becoming significant providers of humanitarian and development assistance. At the same time, these new actors have also been playing an increasingly important role in UN peacekeeping operations, the UN Peacebuilding Commission, and various South-South collaborations. Of course, some new donors have provided assistance for decades. However, the scope and breadth of their engagements is now much more significant than in previous decades.

Although often grouped together, these new actors are a diverse group in terms of the size of their economies, types of regime, global reach of their policies, and their global political ambitions. They include economic powerhouses such as China, relatively poor states like South Africa, regional powers such as India, democracies like Brazil, autocratic states like Russia, and countries of the Arab Gulf. Despite their many differences, these new actors, or new donors as they will be referred in this article, also share similarities on how they conceptualize their relationships with conflict-affected and fragile states that differ in significant ways from how Western donors frame the assistance. In particular, new donors rhetorically emphasize the importance of non-intervention and non-conditionality of aid, viewing them as violating state sovereignty. Consequently, they frame their relationships with conflict-affected states in terms of South-South collaborations and partnerships and as mutually beneficial and reciprocal. These differences between Western and new donors are a reflection of their different histories and experiences with their own development trajectories. Significantly, most new donors have experienced hegemonic power and colonial domination and, therefore, try to avoid replicating such hierarchical relationships in their collaborations with conflict-affected states. At the same time, many new donors have been, in the past or continue to be, conflict-affected states themselves. These experiences with their own conflicts also shape how they conceptualize relationships with states affected by violence. They consequently offer models for improving stability and building peace in conflict-affected states that often remain distinct from those of Western donors.

This study argues, however, that how new donors interact with conflict-affected states is much more complex than these rhetorical framings suggest. Historically, new donors have been much more willing to engage in interventionist policies when interacting with conflict-affected states in their immediate geographic neighborhood than with those that are less proximate. More importantly, as these new actors have become more deeply engaged in supporting countries emerging out of violent conflict and as they have come to aspire playing more prominent global roles, their adherence to principles of non-interference has become, in many cases, more difficult to sustain. Likewise, maintaining these principles has been harder when new donors find their national, investment, and commercial and security interests directly affected by a violent conflict. As a consequence, a number of new donors have increasingly taken on more prominent roles in mediating conflicts, expanding their engagement in peacekeeping operations, and moving away from categorical opposition to the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) principles, and, in particular, Pillar Three1, while remaining concerned about its implications for state sovereignty. In other words, the very expansion of their engagements with conflict-affected states has been shifting their policies vis-à-vis these states. Their growing global aspirations as well as the intensifying competition among some new donors have also pushed them to play an increasingly active role within the United Nations and in regional organizations on issues of promoting stabilization and peace-building in conflict-affected states.

This article is organized as follows. First, how the landscape of donors to conflict-affected states has been shifting over the past couple of decades has been discussed. Next, how Western and new donors have conceptualized their engagements with conflict-affected and fragile states would be briefly explored. In the following section, how geographic proximity has shaped the adherence of new donors to non-interventionist policies has been explored. The next two sections will examine how the expansion of economic interests and, in particular, investments and growing political ambitions have generated tensions for new donors regarding non-intervention norms. Later, the article will focus on how these dynamics have changed the nature of the engagements of Brazil, China, and India in conflict-affected while also more briefly discussing the shifting policies of Turkey and Russia.

Shifting Donor Landscape and Conflict-Affected States

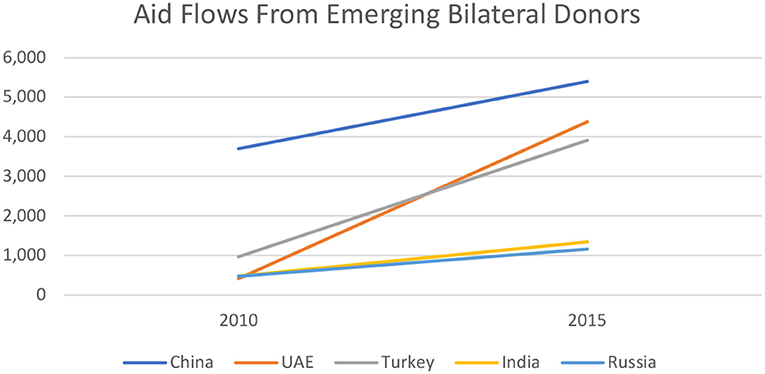

Although Western donors still account for the bulk of development assistance, the contributions of new donors have nearly doubled since 2012 (Devex, 2017). Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the expectation was that they would account for about 20% of global development assistance by the end of 2020. The pandemic may further accelerate these trends as a number of new donors may expand their assistance, seeing the public health and economic crisis as an opportunity to demonstrate their increasingly important global roles (Devex, 2018, 2020; Figure 1).

Figure 1. Aid flows from emerging bilateral donors, 2010−2015 (in billions of US dollars). Data from Devex (2018).

In addition to the expansion of their bilateral and multilateral assistance to conflict-affected states, new donors have also established a number of partnerships and institutions outside of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) frameworks to facilitate collaborations and as alternative sources of financing for the Global South states. In 2004, for example, India, Brazil, and South Africa (IBSA) established the IBSA Dialogue Forum and the IBSA Facility for Poverty and Hunger Alleviation to strengthen South-South cooperation, promote socioeconomic development, and more effectively combat poverty. In 2009, Brazil, Russia, India, and China (BRIC) formed the BRIC Forum as an economic and geopolitical alliance, with South Africa joining in 2010. Since then, the Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa (BRICS) Forum has held 12 summits, the latest in a virtual format in November 2020. More recently, with the establishment of the New Development Bank (NDB) in 2014 and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) in 2016, new donors have also focused on providing alternative sources of development and infrastructure financing to those available through Western-dominated financial institutions. The NDB is operated by BRICS and is set up to foster greater financial and development cooperation between the five nations. The AIIB, on the other hand, is a multilateral development bank whose mission is to finance sustainable infrastructure.

The increasing prominence of new donors came at a time when the international community and Western donors, in particular, became increasingly concerned with conflict-affected and fragile states. In the early 1990's, the end of the Cold War and a spike in the number of violent civil wars made the U.N. both more willing and able to expand the peace-keeping, peace-enforcing, and peace-building activities of the organization, and “member states endorsed a radical expansion in the scope of collective intervention” (Doyle, 2001, p. 529). At the same time, the international community increasingly came to view security and development as inter-related and mutually reinforcing. Thus, “poverty, inequality, and disease” were pointed to “causes of violent conflict, civil war, and state failure” (United Nations Development United Programme, 2000). The 9/11 attacks and US-led global war on terror solidified the dominant discourse of conflict-affected and fragile states spreading “the virus of disorder” globally (Turner and Pugh, 2006).

Western donors designed interventions in conflict-affected and fragile states around a number of principles that came to be known as the liberal peace-building model, which emphasized the importance of market economies and democratic forms of governance as essential to long-term stability and peaceful conflict resolution. Liberal peace-building interventions, thus, focused on supporting the development of accountable and transparent governance institutions and expanding participatory political processes, instituting the rule of law, and promoting the development of market mechanisms and the private sector in addition to security sector reforms. Between 2000 and 2015, official development assistance to conflict-affected and fragile states increased by around 140% in real terms (United Nations/World Bank, 2018, p. 1). Yet, despite billions of dollars of assistance, interventions have generally had very mixed results (OECD, 2020; Word Bank, 2020). As a consequence of these lackluster results, the policies designed to “fix” these states have been criticized as conceptually muddled, ineffective, prioritizing institutional interests of donor agencies rather than those of aid recipients, simply reinforcing global power hierarchies; neglecting local voices, perspectives, expertise, and ownership; and thus all too often resulting in interventions that were not context-appropriate, irrelevant, and lacking legitimacy and sustainability. Thus, these interventions, critics charged, often aggravated rather than alleviated the very conflicts and state fragility they were meant to address (Patrick, 2011; Mac Ginty and Richmond, 2013; Autesserre, 2014, 2021; Luckham, 2017; Woodward, 2017; Firchow, 2018). As Paris (2004, p. ix) underscored, “the process of political and economic liberalization is inherently tumultuous. It can exacerbate social tensions and undermine prospects for stable peace in fragile conditions that typically exist in countries emerging from a civil war.” Critics of the liberal peace-building model have also argued that these initiatives were based on assumptions about the processes of political and economic change drawing on Western experiences without considering how these dynamics may differ in other regions (Suhrke, 2007; Commission on State Fragility, Growth, and Development, 2018). New donors are also critical of the liberal peace-building model and the framing of states affected by violence as fragile.

There is expanding literature that has focused on the growing role of new donors in the provision of humanitarian and development assistance (Amar, 2012; Mawdsley, 2012; de Coning and Pradash, 2016; Mthembu, 2018; Purushothaman, 2021). On the other hand, while there is a growing body of scholarship that focuses on interventions of an individual new donor whose findings this article draws on, there are fewer studies that systematically compare how different new donors conceptualize peace-building and reconstruction interventions in conflict-affected states (de Carvalho and de Coning, 2013; de Coning and Pradash, 2016; Call and de Coning, 2017; Paczyńska, 2019; Ghimire, 2020). These studies find that new donors conceptualize peace-building and reconstruction in ways that differ from Western donors. However, as the study argues, these conceptualizations are not static but rather dynamic and evolving.

In contrast to Western donors, new donors, despite significant differences in their approaches to engaging with conflict-affected states, positioned themselves as alternatives to the liberal peace-building model. Most considered the liberal peace-building model as too intrusive in the domestic politics of recipient states and too focused on imposing political frameworks that were not context-appropriate. For instance, India and Turkey argued that locally rooted, indigenous, and inclusive political institutions were essential to ensuring sustainable peace and that the liberal peace-building model failed to do so when it imposed political frameworks developed elsewhere (Aneja, 2019; Tank, 2019). Others like China and Brazil, for example, were critical of the liberal peace-building approaches because they proved to be ineffective in addressing the root causes of conflict and supporting long-term stability. Sustainable peace, in their view, required tackling poverty and ensuring economic development. In contrast to the Western donor approaches, new donors also framed these engagements in non-hierarchical terms, avoided utilizing the fragile state label, and prioritized solidarity and South-South collaboration, non-interferences, and non-conditionality of aid. Framing their engagements as eschewing interference in domestic politics of conflict-affected states and respecting their sovereignty, new donors placed emphasis on providing demand-driven assistance that reflected the priorities of the recipient governments rather than externally developed programs and policies. However, as argued in this article, these rhetorical framings mask more complex rationales for assistance provision and the dynamic nature of the policies of new donors. In particular, the commitment of new donors to non-interference has always been a bit more strained than the rhetoric suggested. We see this tension in very different ways in which new donors have long engaged with states in their geographic proximity as opposed to those further away. These strains have become even more acute as new donor investments have expanded and, for some new donors, as their global ambitions rose. These shifts have generated pressures to re-evaluate their stance on non-interference and become increasingly involved in conflict mediation, peacekeeping, and peace-building activities.

Distinct Histories and New Donor Policies

Many of the principles shared by new donors in recent times can be traced back to the 1955 Bandung conference and the beginning of the Non-Aligned Movement (Kragland, 2019). This is when conference participants developed 10 principles that were to guide the relationships between the states of what is now often referred to as the Global South. These principles included respect for state sovereignty and territorial integrity, equality of all nations, and non-intervention and non-interference in the internal affairs of other nations2.

The distinct ways in which new donors frame their engagements with conflict-affected states have been shaped by their histories and positions within the global political economy. Especially important have been the legacies of external interventions, colonialism, and hegemonic power domination. New donors, thus, work to avoid replicating similar hierarchical relationships and to develop collaborative and cooperative engagements with conflict-affected states. At the same time, their own experiences with internal, often violent, conflict have driven their commitment to non-interference in domestic affairs of other states and respect for state sovereignty. For instance, South Africa experienced apartheid; Russia fought a war in Chechnya; India has dealt with violent confrontations in Kashmir and Gujarat; and Turkey has engaged in decades-long conflict with its Kurdish population. More recently, China has repressed its Uyghur Muslim minority and the pro-democracy movement in Hong Kong. Many are also located in neighborhoods where other states are grappling with violent conflict. For Russia, Caucasus and Central Asia have been a concern; India has worried about a potential spillover of violence from civil wars in Afghanistan, Nepal, and Sri Lanka; South Africa faced spillover from political crises in Zimbabwe; and the war in Syria raised Turkey's fears about its own as well as regional stability. Many are, thus, apprehensive that policies such as the R2P might be used as justifications for interfering in their domestic affairs, infringing on their sovereignty, or even promoting regime change, concerns that were only heightened by the application of R2P in Libya but not Syria (Li, 2019). These experiences, in turn, impact how new donors approach other conflict-affected states and, in particular, their wariness of interventionist policies that are at the core of the liberal peace-building model.

Experiences with external domination and internal violent conflict have also shaped how new donors conceptualize the relationship between security and development. In particular, most, although not all, new donors have historically focused on establishing economic relationships with conflict-affected states while avoiding political interventions. They largely avoid using the term fragile state as they view it as an example of an externally imposed definition of what a legitimate state looks like. Furthermore, they see the fragility frame as making poverty a security rather than a developmental challenge and placing the blame for threats to global peace and security on states of the Global South rather than the states of the Global North who, they argue, have historically perpetuated the most violence (Paczyńska, 2016, 2019). Thus, much of the assistance they offer includes direct investment, trade deals, and infrastructure development since they view poverty and economic underdevelopment as the root cause of instability and conflict and that, without sustainable development, long-term peace is impossible. This understanding of the relationship between development and conflict lies at the heart of their critique of the liberal peace-building model, which they believe has failed to effectively tackle the issue of sustainable development3. At the same time, although many have also provided peacekeeping troops to UN missions, they have tended to be less willing to embrace more far-reaching peace-building endeavors, viewing them as too interventionist in domestic affairs of conflict-affected states. As we will see in the section that follows, however, these policies of limited support for expansive peace-building missions and policies of non-interference have proven to be more malleable than this rhetoric suggests.

New Donors and Geographic Proximity

Where rhetorical framings and policy diverge in significant ways is in how new donors engage with conflict-affected states in their geographic neighborhoods and those that are more distant. In the former, security concerns tend to dominate; in the latter, commercial interests usually take priority, although these dynamics have been shifting over time, a point this study will return to in the concluding section. In particular, their commitment to non-intervention in affairs of other states has been more tenuous when responding to violent conflicts in areas they consider their spheres of influence. Here, concerns of violent conflict spilling across national boundaries and potentially affecting the internal stability of new donors mean that many have long been willing to pursue policies that indicate their commitment to non-intervention policies may be more situational than the public rhetoric suggests.

India has long seen South Asia as its sphere of influence and where it has sought to intervene in conflicts in neighboring states, in particular, in Sri Lanka, Nepal, and Afghanistan. Here, as Aneja argues, “India's commitment to principles of sovereign equality and noninterference in the region has been highly selective” (Aneja, 2019, p. 57). In other words, when the security interests of India are under threat in its immediate region, it is willing to exert political pressure and intervene, including with military force, into the internal affairs of other states.

In 1971, for example, India sent troops to East Pakistan during the Bangladesh Liberation War following increasing violence of the Pakistan army against the Bengali population, framing the action as humanitarian intervention (Bass, 2015)4. In 1987, it intervened militarily in the civil war in Sri Lanka between the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) and the Sri Lankan government, sending the Indian Peace Keeping Force following the signing of the Indo-Sri Lankan Accord. Although it was intended as a peacekeeping operation, the Indian forces engaged the LTTE militarily before finally fully withdrawing in 1990. In 1988, Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi sent 1,600 troops to the Maldives to stop an attempted coup. India has also sidestepped non-intervention principles through non-military interventions. In 2015, for instance, India wanted to see Nepal revise its newly adopted constitution that aimed to bring the civil war in the country to an end. New Delhi felt that some aspects of the document risked continued instability in the country. When diplomatic pressure did not lead to desired changes, India implemented an economic blockade on Nepal to force through constitutional revisions. At the same time, as competition for influence in the region with China has intensified, India has also sometimes circumvented non-intervention principles when, for instance, it decided to provide military equipment to the Sri Lankan government during the 2009–2011 civil war.

India sees its security and economic development prospects as closely tied to establishing stable, friendly states in the region. Most recently, these priorities were articulated during the United Progressive Alliance government (2004–2011) as well as its successor Bharatiya Janata Party led by Narendra Modias neighborhood first policies. Assistance to Afghanistan reflects these concerns and priorities and has focused on linking security and economic development as the most effective way of curtailing the rise of regional extremist ideologies and establishing a stable Afghanistan. These policies stood in stark contrast to the relationship of India with conflict-affected states in Africa where interest in securing access to raw materials and export markets dominates and where India had framed its engagements in terms of the South-South cooperation (Paczyńska, 2019, p. 12). In these more geographically distant regions, however, as this article will examine in the next section, as India's investments in conflict-affected states have expanded, the pressure to loosen commitments to non-intervention principles have also grown.

We see similar dynamics in the policies of Turkey toward conflict-affected states. Since the coming to power in 2003 of the Justice and Development Party (AKP), Turkey abandoned its earlier support to the liberal peace-building model. Instead, Ankara began framing its relationships with conflict-affected states as humanitarian diplomacy based on Islamic principles, which it has presented as an alternative to what it views as failed Western interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq. Rather than trying to rebuild states that are affected by violent conflict to look like the donor state, humanitarian diplomacy focuses on supporting indigenous institutions that can ensure sustainable economic development and efficient governance. Turkey has applied this approach in its relationship with Somalia, where it has focused on facilitating reconstruction of state infrastructure, promoting economic development, and supporting strengthening of local governance mechanisms, while facilitating peace and reconciliation processes. However, Turkey's commitment to this approach and to non-intervention principles came under strain with the eruption in 2011 of Arab uprisings when Ankara became increasingly concerned about the impact of the uprisings on the Kurdish autonomy movement and saw its security interests threatened as protests in neighboring Syria morphed into a civil war. Faced with these security challenges in its immediate geographic neighborhood, Turkey abandoned its adherence to non-intervention and non-interference principles and began to openly support armed Sunni groups who were fighting to overthrow the Bashar al-Assad regime (Tank, 2019).

Like Turkey, Qatar also moved away from its previous focus on conflict mediation to a more interventionist approach in the wake of the Arab uprisings and began to explicitly offer support to rebels in Libya and Syria. In the latter, it funneled $3 billion between 2011 and 2014 to opposition forces. It also provided financial support to Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood and President Mohamed Morsi during his tenure in office (Barakat and Milton, 2019).

Russia has also approached its near-abroad differently than more distant parts of the globe. In its immediate geographic neighborhood, and in particular, in Caucasus and Central Asia, Russia has long seen itself as a hegemonic power, and its focus is on ensuring stability both through development assistance and prioritizing by addressing violence, since Russia views the potential of conflicts spilling across borders as a direct threat to its own security. The policies of Russia aim at reintegrating former Soviet Republics through security and economic ties and reducing the influence of other global powers, and development assistance is, therefore, seen as a mechanism for “maintaining general geopolitical influence in the region” (Sergeev et al., 2013, p. 55). In addition to the creation of the Commonwealth of Independent States Free Trade Area (CISFTA), Russia has also signed a collective air defense system in the Caucasus and in Central Asia. It has also signed a lease agreement with Tajikistan on the 201st Motorized Rifle Division military base that is in effect until 2042, and Moscow successfully pressured Kyrgyzstan in 2014 to terminate the US Manas Air Force base (Zürcher, 2019). Moscow has also been willing to intervene militarily when it felt that its strategic interests in the near abroad were threatened. In 1992, Moscow sent its 14th Army when secessionist conflict in Moldova escalated. In 2008, Russia backed the breakaway self-proclaimed republics of South Ossetia and Abkhazia in Georgia. In 2014, its forces invaded the Crimea region of Ukraine, and in 2020, Russia sent peacekeepers to Nagorno-Karabakh following the renewed conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan in the province. The 2014 Concept statement underscores the link between Russian development assistance and its national interests especially in the near abroad. It argues that “active and targeted policy in the field of international development assistance, which serves the national interests of the country, contributes to stabilization of the socioeconomic and political situation in partner states (…) and facilitates the elimination of existing and potential hotbeds of tension and conflict, especially in the regions neighboring the Russian Federation” (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, 2014).

In contrast, the more recent Russian involvement in Latin America is focused primarily on commercial relationships, arms exports, and diplomatic outreach. Here, it has sought to develop partnerships with countries interested in establishing institutions not dominated by the United States and has forged a close collaboration with Brazil through the BRICS group (Gurganus, 2018) and offered support to the Maduro regime in Venezuela (Herbst and Marczak, 2019). Similarly, Moscow's engagements with African states are driven by a different set of interests and while Moscow has been the largest weapons supplier to the continent, concerns about Russia security here are supplanted by interest in expanding economic relationships, including trade and investments, building political alliances in the wake of the 2014 expulsion of Russia from the G-8 and sanctions imposed by the West following the invasion of Ukraine, especially with those states, such as Zimbabwe, that have been sanctioned by the West, and as a strategy to increase its global stature at the expense of Washington (Paczyńska, 2020). However, as Russia's footprint in Africa expanded along with its global ambitions and the growing competition with other new donors, its engagements with conflict-affected states on the continent have also become more interventionist. In Central African Republic, for instance, Russian diplomats and a Russian security firm, the Wagner Group, have been active in supporting the government and have facilitated negotiating ceasefire agreements with rebels (Lewis, 2020). Moscow has also been increasingly deploying a strategy that mixes security cooperation and electoral support for embattled regimes, including Angola, DRC, and Mozambique, in return for access to mineral resources and diplomatic support in international fora such as the UN (Stronski, 2019).

Expanding Investments, Shifting Security Interests

In addition to the differences in how new donors approach engagements with conflict-affected states in their immediate neighborhoods vs. those that are further away, their policies have also been shifting in response to realities on the ground in conflict-affected states where they have a presence.

One of the consequences of the expanding footprint of new donor in conflict-affected and fragile states is that maintaining political neutrality and remaining on the sidelines can be challenging, especially when violent conflict erupts. In these contexts, it has often become more difficult for new donors to maintain their adherence to non-interference policies. Although each has responded differently, these tensions have been especially visible in the experiences of India and China, which have the largest financial investments in conflict-affected states. Both countries have therefore been adjusting their policies to these new realities, although they have done so differently with China becoming directly and openly engaged with mediating conflicts and supporting regional peace-building efforts, while India has mediated conflicts only rarely and mostly in an ad-hoc manner and informally. However, New Delhi is increasingly including issues of peace and security in its South–South collaborations. Both have also been shifting their engagements with UN peacekeeping missions, including participating in more robust operations involving direct combat. As the article will discuss in the section that follows, the shifts in both countries approach to peacekeeping and peace-building are also shaped by their expanding global ambitions as well as the growing competition between them.

Over the past 15 years, Chinese assistance has grown significantly with the country disbursing about $350 billion between 2000 and 2014 in various forms of financing, including official development aid as well as other financial flows. Most of its development and welfare assistance is concentrated in Africa, while its commercial financial flows are more geographically disbursed (AIDData,)5. In 2018, the China International Development Cooperation Agency was created. By March 2020 it had signed agreements with 29 countries. Most are conflict-affected states that rank high on the various fragile states lists6. In 2013, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a massive infrastructure development and investment project, began, and by 2020, it stretched from East Asia to Europe, Middle East, and Africa with over 60 countries which account for two-thirds of the global population either signing onto the initiative or indicating plans to do so. Many of these states, such as Afghanistan, DRC, Cote d'Ivoire, Ethiopia, Iraq, Liberia, Myanmar, and Nepal, among others, are conflict-affected and fragile states. China has already disbursed $200 billion in low-interest loans for the initiative by 2020. By some estimates, the total investment in the initiative may be close to $1.3 trillion by 2027 (Chatzky and McBride, 2020). The BRI has been one of the key vehicles through which China has sought to increase its political and economic influence as its global aspirations rose. Recent survey results indicate that the Chinese development assistance is viewed positively by a majority of Africans (Lekorwe et al., 2016) and Middle Easterners (Robbins, 2021). As these investments have expanded, the number of Chinese businesses and migrant workers living abroad have also increased. In Africa, for instance, there are now more than 10,000 Chinese businesses and over 1,000,000 workers. Ensuring their security from crime, civil unrest and terrorism have become a growing concern to Beijing (Alden and Jiang, 2019, p. 653). These concerns have been amplified in states affected by violent conflict. Consequently, as Alden and Jiang point out, “China has recently been compelled to involve itself in conflict areas outside its borders in ways that some—even some Chinese—see as counter to its policy of non-interference” (Alden and Jiang, 2019, p. 653).

Historically, China refrained from conducting international mediation, believing that maintaining neutrality was most conducive to achieving its national interests while maintaining its policy of non-intervention (Chaziza, 2018). However, as multiple violent conflicts have increasingly threatened its interests, China has sought to shift its policies while seeking to maintain its non-intervention preferences. These tensions between normative commitments and policy choices have been most visible in South Asia, Africa, and the Middle East where China has significant investments and along the BRI locations and especially in those contexts where its nationals and financial interests are directly affected by violent conflict. There has been a notable uptick of Chinese conflict mediation activity since 2013, the same year that the BRI was launched (Legarda, 2018). In the Middle East, which has become a key source of oil imports, the interests of China in regional stability that would ensure secure access to energy resources has also pushed Beijing to become more involved in conflict mediation in the region, including efforts to reduce tensions in the Persian Gulf and the Straits of Hormuz (Balasubramanian, 2020). The expansion of Chinese trade and investments beyond the oil sector in finance, services, and renewables further fuels the interest of Beijing in ensuring regional stability (Kuo, 2020). Furthermore, as the global reach of China has expanded, the Chinese public has become more aware and concerned about the impact of conflict on its nationals, thus raising pressure on the Chinese government to be more proactive in conflict prevention. The Chinese government has been increasingly relying on special representatives to address escalating conflicts. In 2017 alone, Beijing was involved in mediating nine conflicts in contrast to only three in 2012 (Legarda, 2018). Unlike in the past when its few mediation efforts were done quietly, for instance in Zimbabwe and Nepal, now the Chinese government publicizes its efforts in preventing, managing, and resolving conflicts through official government statements and media coverage.

For instance, China played a central role in persuading the government in Khartoum to accept a joint United Nations–African Union (UN–AU) peacekeeping force in Darfur. It has also engaged in dialogue on the Iranian nuclear issue, mediation of the Yemen and Syrian civil wars, the Israeli-Palestine conflict, contributed to South Sudan domestic reconciliation process, supported the Afghanistan political transition, and has been engaged in inter-ethnic reconciliation efforts in Myanmar and mediation of the Myanmar-Bangladesh conflict regarding the future of the Rohingya people (Legarda, 2018). In Libya, Sudan, and South Sudan where China had large investments in the petroleum industry, it played an important role in mediating conflicts when violence escalated and threatened both its investments and nationals working in these three countries. Additionally, in South Sudan when it relapsed into civil war in 2014, China sent in peacekeeping troops to protect the assets and personnel of the Chinese National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) (Bodetti, 2019). The involvement of China in conflict mediation in the Middle East and Africa has been made easier by its lack of colonial baggage that colors the relationships off these states of these regions with other global powers (Chaziza, 2018). In the Middle East, it has also focused on strengthening both multilateral and bilateral cooperation with regional actors and other global powers as a way to more effectively manage conflicts.

As its involvement in conflict mediation has grown, states affected by violence have been increasingly looking to China to play a stabilizing role. Thus, the combined dynamics of the concern of China about protecting its investments and interests, its global aspirations, and the interests of states affected by violence are further increasing the shift in the Chinese foreign policy toward more interventionist policies than was the case in the past even as it maintains non-interference rhetorical framings (Chaziza, 2018).

As its conflict mediation has expanded, China has sought to walk a fine line in developing more interventionist policies while continuing to frame its engagement in terms of non-interference. It does so by limiting the stated objectives of the mediation itself and by always consulting sovereign governments involved in the mediation efforts, in what has been dubbed by some scholars as “consultative intervention.” As Li points out, “the logic is that if the host government is receptive and welcoming [to the mediation] it no longer constitutes interference” (Li, 2019), thus allowing China to significantly shift its policies without appearing to abandon its fundamental principles. China also engages in what Hirono (2019, p. 615), for example, has dubbed “incentivized mediation,” in which Beijing uses its economic power to “provide incentives or leverage for warring factions to come to the negotiating table, but which also lets the warring factions formulate their own roadmap to peace talks.”

At the same time, China's growing interest in ensuring stability in Africa was reflected in the convening of the 2012 Forum on Africa–China Cooperation (FOCAC) meeting. Since then, Beijing has expanded its security and multilateral peace-building cooperation on the continent. It has signed onto the Initiative on China–Africa Cooperative Partnership for Peace and Security (ICACPPS) that aims to bolster local capacities, and it has expanded its support to the African Union (AU), Africa Standby Force, the Africa Capacity for Intermediate Response to Crises, and the Africa Peace and Security Architecture (Alden and Zheng, 2019). At the same time, Beijing also expanded its contributions to peacekeeping operations, which, since 2013, have included combat troops, which were deployed to Mali and South Sudan (Alden and Jiang, 2019).

Although much smaller than that of China nonetheless, the development assistance of India has also increased significantly in the past couple of decades rising four-fold and reached $1.6 billion in 2017 (Aneja, 2019). An area where the engagement of India has expanded rapidly has been in Africa. By 2020, it had completed 194 development projects in 37 countries on the continent and was working on completing an additional 77 projects worth $11.6 billion. Its trade and investment also expanded significantly over the past two decades (Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, 2020c). By 2020, India accounted for $62.6 billion or 6.4% of the total trade of Africa, making it the third largest trading partner after China and the US (Kurzydlowski, 2020). India has also become the fifth largest investor on the continent, with more than $50 billion in investments with most concentrated in oil and gas, mining, and banking and textiles. In conflict-affected states, most of these investments are in the natural resources sector. These expanding relationships were reaffirmed at the fourth India-Africa Forum Summit held virtually due to the COVID-19 pandemic in September 2020 (Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, 2020a).

India has long been committed to policies of non-interference, non-intervention, and respect for state sovereignty and has therefore framed its relationships with conflict-affected states in collaborative and non-hierarchical terms. These policy framings have also meant that in Africa, India has generally tended to “work around rather than directly engaging with sources of political fragility” (Aneja, 2017). However, like China where its investments have come under threat from violent conflicts, its commitment to these principles has come under strain, and New Delhi has been increasingly promoting a holistic approach to state stability as a prerequisite to sustainable economic growth and security. Overall, however, India has responded differently than China to these challenges. While it has been engaged in conflict mediation in its immediate geographic neighborhood and has often pursued policies that strain its non-interventionist principles, as discussed in the previous section, in other regions where violence has threatened its investments and nationals and challenged its security interests, it has been more reluctant to engage directly in conflict resolution. The shifting policies of India in Africa are reflected more in the increased focus on security and peace in its engagements with regional organizations and bilateral relationships while its conflict mediation efforts tend to be informal and ad-hoc. Nonetheless, on occasion as in the case of the Sudan–South Sudan conflict, where India had over $ 2 billion invested in the gas and oil sector, India has engaged in mediation. Here, in response to the recurring civil war following the independence of South Sudan, New Delhi was also willing to increase its contributions to the UN Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) and its troops here were willing to engage in robust peacekeeping given the high levels of violence and resulting threats to the civilian population (Mohan, 2016; United Nations, 2016).

As their economic and commercial relationships expanded, India followed the footsteps of China in expanding its collaboration with African states on issues of peace and security. This new focus on security and conflict resolution was reflected in the discussions at the India-Africa Forum Summits, with the first one held in New Delhi in 2008. In 2011, at the second summit in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, two documents, the Addis Ababa Declaration and the Africa–India Framework for Enhanced Cooperation, were adopted and set the terms “for the establishment of a long-term and mutually beneficial partnership encompassing diverse fields” Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies Analysis, 2011b). Against this backdrop of deepening relationship between India and Africa, the first India-Africa Strategic Dialogue conference was held in 2011, focusing on issues of peace-building, conflict resolution, and reconstruction as processes that would facilitate long-term stability and ensure civil wars would not reignite. Thus, while India continued to stress that all UN peacekeeping mandates required the consent of the host states, nonetheless, it called for sustained peacekeeping efforts that ensured peace-building based on “pardon and integration” and attention to the unique features of each conflict context to ensure a successful mission (Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies Analysis, 2011a). Later, strategic dialogues also focused on issues of terrorism, extremism, and maritime security. Thanks to this long-term partnership, thousands of African military personnel have been trained in India (Aneja, 2019, p. 60).

With growing competition with China and new global aspirations of the Modi government, which came to power in 2014, India further expanded its diplomatic, military, and security and peace engagements. In March 2018, India established 18 new diplomatic missions on the continent. By 2020, the number of diplomatic missions rose to 38. The collaboration deepened further when in February 2020 India and 50 African states signed the Lucknow Declaration, “which appreciated that India and Africa were a significant part of the Indo-Pacific continuum and that the AU Vision for peace and security in Africa coincided with the vision of India of SAGAR (Security and Growth for All in the Region)” in addition to emphasizing the continued close investment and financial and trading relationships (Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, 2020b). The signatories also pledged to continue collaborating on peace and security issues, including conflict prevention, resolution, management, and peace-building, enhancing the “role of women in peacekeeping” and fighting terrorism, and urging the UN to adopt the Comprehensive Convention on Terrorism (Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, 2020b). Furthermore, the declaration pledged that there would be improved “exchange of experts and expertise, training programs and capacity building, enhanced support toward peacekeeping and post conflict reconstruction in Africa” and improved various defense joint ventures (Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, 2020b).

Similar dynamics are at play in South Asia. As discussed in the previous section, historically India has been much more willing to intervene in its immediate geographic neighborhood to ensure that violent conflicts do not spill across borders affecting the internal of India. As its investments in the region grew and competition with China intensified, India has become more active in maintaining regional peace and security and its “rising activism has resulted in India taking the lead in crisis response as regional ‘leading power’ and ‘first responder’ to natural and manmade disasters, including the Nepal earthquake and the Myanmar refugee crisis” (Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, 2020b). India has also become more directly involved in supporting peace-building initiatives, such as the 2018 peace negotiations in Myanmar. Also shifting is the willingness of India to support pro-democracy initiatives. While initially India sided with China and Russia in opposing western attempts at democracy promotion as a way of resolving conflicts, for instance, voting against imposing sanctions on Myanmar in 2007 in support of its pro-democracy movement, as its regional competition with China increased and its concerns about the destabilizing potential of the BRI rose, this reluctance has declined. It is now much more frequently emphasizing democracy and good governance in forging cooperative partnerships with other states in the region (Xavier, 2018).

Global Aspirations

A number of the new donors, and in particular China, India, and Brazil, have increasingly aspired to playing more prominent global roles. With these shifting aspirations, their policies toward conflict-affected states have evolved as well, putting strains on their commitment to non-intervention norms. At the same time, as their global prominence grew, they also faced growing pressure from Western donors and especially the United States to contribute more to U.N. peacekeeping initiatives, although Western donors remained concerned about the nature of Russian and Chinese bilateral assistance to conflict-affected states. These two dynamics have combined to create more tensions between the rhetorical commitment to non-intervention policies which the new donors have increasingly pursued.

In addition to the growing concern of China about protecting its investments and nationals, the intensifying conflict mediation efforts by Beijing are also motivated by the growing aspirations of China to be seen as a responsible global power. During the Trump presidency, in particular, President Xi has sought to position China as a constructive actor on the global stage in line with the long-term objective of Xi of turning China into a global power by 2049 (Legarda, 2018). As a consequence of these growing global ambitions, Chinese diplomats are involved in more mediation and regional negotiation efforts than in previous decades (Chaziza, 2018). In the Middle East, China uses mediation not only to promote its own economic, political, and security interests but also to cultivate its image as a responsible global power and enhance its international prestige and to enhance its influence as the regional balance of power shifts (Chaziza, 2018; Li, 2019).

As tensions between China and the United States increased, the Middle East has also become a region where China can challenge Washington as an increasingly important economic partner and one that, unlike the United States, has working relationships will all the major states in the region, including Iran, Israel, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey. These good relationships have allowed Beijing to become an active mediator, positioning itself as a regional peace-broker, including in Syria and Yemeni civil wars and the Sudanese crisis. However, since Beijing tries to mediate these conflicts without becoming embroiled militarily, its approach, as one observer noted, “seems to be more focused on solutions that can contain tensions and bring about negative peace rather than long-term, futuristic, and sustainable solutions” (Balasubramanian, 2020). At the same time, these good relationships and mediation diplomacy have also meant that these regional powers have not criticized the repression of China of political opposition in Hong Kong and its Uyghur minority.

China, in addition to becoming more involved in conflict mediation, also begun reevaluating its opposition to the R2P principle and in particular Pillar Three, which discusses the obligation of the international community to take action if a state does not fulfill its obligations to protect its population. Although the views of China and Western donors on the application of R2P continue to diverge, there is also a clear convergence under way with China endorsing its application in a number of cases. However, this endorsement generally focuses on Pillars One and Two, which focus on state responsibility to protect its population from mass atrocities and the responsibility of the international community to encourage and assist states in doing so (Fung, 2016). At the same time, the interest of China in playing a more prominent global role has translated into greater engagement in peacekeeping operations since 2000. In 2004, China became the largest UNSC permanent member troop contributor to the peacekeeping missions of the UN. Although, initially, it contributed primarily to police, engineering, and hospital units, in 2015, it began also fielding combat troops in South Sudan and Mali and has established a logistics base in Djibouti “in part to support” its peacekeeping troops stationed in Africa (Gowan, 2020). In 2015, President Xi Jinping expanded the commitment of China to peace and security with the pledge of $1 billion to UN programs supporting initiatives in this area, and Beijing has become increasingly engaged with debates at the UN headquarters regarding peacekeeping policy (Alden and Zheng, 2019). Here, it has focused on how best to ensure the safety of peacekeepers and trying to limit the number of human rights officials assigned to the missions. Yet, despite its concerns with what it views as overly interventionist aspects of peacekeeping missions, it has nonetheless been signing onto UNSC mandates that include “expansive language on the responsibility of UN forces to protect civilians, advance human rights, and relate priorities” (Gowan, 2020). By 2020, China had 2,534 Chinese nationals at UN missions in South Sudan, Sudan, Mali, and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). This tension underscores the challenge of combining growing global ambitions with non-interventionist principles.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, China intensified its efforts to position itself as a responsible global power, providing assistance through multilateral and bilateral channels to help fight the pandemic and distributing medical supplies, medical teams, and vaccines. At the UN, Chinese representatives linked the fight against the pandemic to long-term peace-building approaches that should be “development-focused and socially inclusive” and emphasized the need for solidarity, collaboration, and multilateralism (United Nations, 2020). The extraordinary China-Africa Summit of Solidarity in the Face of COVID-19 held in June 2020 also underscored the link between the ongoing public health crisis and peace (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People's Republic of China, 2020).

Despite long being one of the largest contributors to the UN peacekeeping forces, India has been quite skeptical about the effectiveness of external interventions in conflict-affected states, concerned that such interventions often exacerbate the very problems they are designed to solve (Aneja, 2019) and saw the primary responsibility for building sustainable peace as ultimately resting with conflict-affected states themselves with the international community playing only a supportive role. However, as its global ambitions grew, India, like China, has shifted its approach to issues of peace and security, upped its contributions to the UN Democracy Fund, became an active member of the UN Peacebuilding Commission, and recognized the R2P principle in 2009, all with an eye toward bolstering its great power aspirations (Chandy, 2012). Although India has a much smaller global footprint than China and remains much more reluctant to engage in public mediation diplomacy and continues to be more preoccupied with its immense domestic challenges, its key role as a contributor of troops to UN peacekeeping missions is seen by New Delhi as a way to make a strong case for its inclusion as a permanent member of the UNSC (Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies Analysis, 2011a). As it has sought to attain great power status, India has also continued to frame its engagements with the Global South in terms of solidarity, non-interference, and respect for state sovereignty and to present itself as “an alternative power” that values morality and non-coercion (Pu, 2017). Despite these norms in practice while participating in the many UN peacekeeping operations over the years, the military contingents of India have sometimes undertaken “robust” operations, sometimes engaging in direct combat (Mukherjee, 2015; Pu, 2017). The new, more expansive engagement with peace and security challenges has also meant that the policies of India have placed new strains on non-intervention norms.

As in the case of India and China, as Brazil's global ambitions shifted, its commitment to non-intervention policies also came under strain. Historically, the foreign engagements of Brazil reflected the values of its 1988 constitution, which stated that these must be “guided by the principles of non-interference, equity among states, the peaceful resolution of conflicts” and a commitment to human rights (Esteves, 2019). As the interventions in conflict-affected states of the UN became more extensive during the 1990's, Brazil continued its adherence to these values, frequently voicing concerns about unilateral military interventions. For these reasons, despite supporting peacebuilding initiatives of the UN, Brasilia opposed the increasingly frequent peace enforcement missions. These views were also reflected in the opposition of Brazil to the Agenda for Peace put forward by UN Secretary General Boutros Boutros-Ghali in 1992, which it viewed as a “reinterpretation of the Security Council's mandate toward a more militarized direction” (Esteves, 2019), making it easier for the UN to contemplate more coercive interventions in the future. Brazil was also concerned that the Agenda may encourage major global powers to rely on military force rather than on negotiations and diplomacy to address conflict and security challenges. It was particularly concerned that the international community, with the adoption of this new framework, might be moving away from requiring the consent of states before peacekeeping troops could be deployed on their territory, something that Brazil saw as essential to respecting norms of state sovereignty.

However, by the early 2000's, the aspirations of Brazil to playing a more prominent global role began shifting during the administration of President Lula. As Harig and Kenkel (2017, p. 626) point out, the goal of this shift in policies was to cement “the role of country as a relevant participant in global governance. The prime goal of this increased activism in international affairs was ultimately the permanent membership of Brazil in the UNSC”. However, as its priorities evolved, Brasilia began grappling with tensions between its new foreign policy objectives and aspirations to be seen as a “responsible” global power and its commitment to non-interventionist norms. In Latin America, this shift was reflected in more active engagement with conflict-affected countries in its immediate neighborhood, and in particular, Bolivia, Colombia, and Venezuela. At the global level, it came in the form of reduced opposition to the Agenda for Peace and the R2P doctrine and, in particular, Pillar Three. Here, both the Lula and the Rousseff governments (2003–2011 and 2011–2016) sought to shape norms underpinning the international order and in particular pushed for fairer treatment of all states while mostly supporting liberal norms. Although in the end, Brazil dropped the initiative, in 2011 it sought to modify the norms underpinning R2P by promoting an alternative “responsibility while protecting,” which called for “strict political and chronological sequencing of R2P's three pillars and making a conceptual distinction between collective responsibility and collective security” (Kenkel, 2016). This initiative emerged in response to the NATO intervention in Libya enabled by UNSC Resolution 1973. Many new donors, including Brazil, were deeply suspicious of the motives behind the action of the West. Thus, Brazil was forced to deal with tensions between its principle of non-intervention and its commitment to working through multilateral institutions on peace promotion and its increasing acceptance of R2P. Brasilia sought to resolve these tensions by accepting the norms underpinning R2P, mass atrocity prevention and human right protection, while criticizing the selective implementation of the norm by the international community (Harig and Kenkel, 2017, p. 631).

At the same time, Brazil sought to develop alternative new international fora, such as the BRICS collaboration, IBSA Dialogue Forum, and the G-10, where it could play a prominent role and increasingly become an international norm-setter. It also expanded its role in such organizations as the Union of South American States and the Community of Portuguese Language Countries and worked to play a more central role in a variety of multilateral organizations. At the UN, Brazil was a key actor in setting up the Peacebuilding Architecture, including the Peacebuilding Commission, chairing the country security configuration of the Commission for Guinea-Bissau in 2007. All these efforts were done with an eye toward “boosting its bid for a permanent seat on the UNSC” (Call and Abdenur, 2017).

As it shifted its global ambitions, Brazil also faced tensions regarding how to engage in UN peacekeeping missions as they become more expansive in the 1990's raising concerns about their increasingly coercive nature. Despite these concerns, Brazil took the lead of the UN Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH) in 2004. While deploying its military, which often engaged in coercive action, Brazil sought to resolve the tension between its non-intervention principles and its leadership of the Haiti mission by emphasizing the humanitarian and development aspects of the mission. Nonetheless, the leadership of Brasilia of the MINUSTAH represented a significant change in its foreign policies and strained its commitment to non-interventionist norms. Since 2011, Brazil has also taken on an important role in the UN Interim Force in Lebanon (UNFIL) to project an image of peace provider in a conflict-affected region and as “part of a broader policy project of Brazilian influence and presence (…) projecting an image of a responsible power capable of having a positive influence in maintaining international peace and security” (Silva et al., 2017).

Conclusion

The past couple of decades have seen the emergence of new donors who framed their assistance to conflict-affected states very differently than Western donors have done. In particular, because of their own experiences with hegemonic and colonial domination and violent conflict, these new donors have emphasized South–South collaboration, reciprocity, and solidarity, and non-intervention norms in their engagements with conflict-affected states. However, as this article has argued, the non-intervention norm has always been applied more selectively than the public rhetoric has suggested, with new donors historically willing to pursue interventionist policies in states that are geographically proximate and where their security interests are at stake. Furthermore, as the economic footprint of new donor has expanded with investments and nationals more frequently located in states affected by violent conflict, as their global ambitions have risen and finally as the competition among the new donors has intensified, these non-intervention norms have come under new strains. China has expanded its involvement in conflict mediation efforts. Both China and India have developed new agreements with African states that focus on addressing issues of peace and security. Finally, Brazil, China, and India have played increasingly important roles in UN peacekeeping and peace-building policies and operations. Since its 2014 invasion of Crimea, Russia has also expanded its military and political engagements with conflict-affected states in Africa. It has sought to influence elections, negotiated to establish military bases, and its semi-private military groups moved in to shore up some conflict-affected states, such as the Central African Republic, as it seeks new diplomatic allies and to more effectively compete with India and China on the continent. The COVID-19 pandemic has further solidified these trends, with new donors looking to demonstrate their ability to play more prominent global roles by increasing their assistance to countries affected by the dual public health and economic crisis.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

United State Institute of Peace, grant number USIP-108-13F.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

1. ^(accessed 12 March, 2021).

2. ^For all the principles see, for example, Final Communique of the Asian-African Conference of Bandung (1955).

3. ^Although new donors frame their assistance as promoting sustainable development, whether their policies actually contribute to achieving it has come under scrutiny. In particular, the long-term consequences of growing levels of debts to China have raised concerns. See for example, Hurley et al. (2018) and Chakrabarty (2020). These concerns have been questioned by other scholars. See, for example, Bräutigam (2020).

4. ^Bass cites Indian scholar Pratap Bhanu Mehta who argued that this intervention has been “regarded as one of the world's most successful cases of humanitarian intervention against genocide. Indeed, India in effect applied what we would now call the “responsibility to protect” (R2P) principle, and applied it well.” (p. 229) However, at the time, India found little support for its action within the international community, including at the United Nations.

5. ^AIDData. See also, Kitano and Miyabayash (2020).

6. ^There are a number of different fragile state lists that use somewhat different methodologies, including annual rankings developed by the OECD and the Fund for Peace. In the 2020 OECD States of Fragility Report for instance, more than half of states in Africa were classified as fragile.

References

AIDData. China's Global Development Footprint (2014). Available online at: https://www.aiddata.org/china-official-finance?ref=china.aiddata.org (accessed December 28, 2020).

Alden, C., and Jiang, L. (2019). Brave New World: dept, industrialization and security in China-Africa relations. Int. Affairs 95, 641–657. doi: 10.1093/ia/iiz083

Alden, C., and Zheng, Y. (2019). “China: international developmentalism and global security,” in The New Politics of Aid: Emerging Donors and Conflict-Affected States, ed A. Paczyńska (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers), 25–52.

Amar, P. (2012). Global South to the Rescue: Emerging Humanitarian Superpowers and Globalizing Rescue Industries. London: Routledge.

Aneja, U. (2017). India's Response to State Fragility in Africa. New Delhi: Observer Research Foundation.

Aneja, U. (2019). “India: between principles and pragmatism,” in The New Politics of Aid: Emerging Donors and Conflict-Affected States, ed A. Paczyńska (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers), 53–70.

Autesserre, S. (2014). Peaceland: Conflict Resolution and the Everyday Politics of Intervention. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press). doi: 10.1017/CBO9781107280366

Autesserre, S. (2021). The Frontlines of Peace: An Insider's Guide to Changing the World. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Balasubramanian, P. (2020). China's Approach to Mediating Middle Eastern Conflicts. The Diplomat. Available online at: https://thediplomat.com/2020/10/chinas-approach-to-mediating-middle-eastern-conflicts (accessed January 5, 2021).

Barakat, S., and Milton, S. (2019). “Qatar: conflict mediation and regional objectives,” in The New Politics of Aid: Emerging Donors and Conflict-Affected States, ed A. Paczyńska (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers), 141–160.

Bass, G. J. (2015). The Indian way of humanitarian intervention. Yale J. Int. Law 40, 228–294. Available online at: https://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/yjil/vol40/iss2/2 (accessed March 12, 2021).

Bodetti, A. (2019). How China Came to Dominate South Sudan Oil. The Diplomat. Available online at: https://thediplomat.com/2019/02/how-china-came-to-dominate-south-sudans-oil/ (accessed January 5, 2021).

Bräutigam, D. (2020). A critical look at Chinese “Debt-Trap Diplomacy”: the rise of a meme. Area Dev. Policy 5, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/23792949.2019.1689828

Call, C. T., and Abdenur, A. E. (2017). Brazil's Approach to Peacebuilding. Geopolitics and Global Issue Paper 5. Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution.

Call, C. T., and de Coning, C. (2017). Rising Powers and Peacebuilding: Breaking the Mold? London: Palgrave Macmillan. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-60621-7

Chakrabarty, M. (2020). Will China Create Another Debt Crisis? New Delphi, India: Observer Research Foundation. Available online at: https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/will-china-create-another-african-debt-crisis/ (accessed March 12, 2021).

Chandy, L. (2012). New in Town: A Look at the Role of Emerging Donors in an Evolving Aid System. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Chatzky, A., and McBride, J. (2020). China's Massive Belt and Road Initiative. Washington, DC: Council on Foreign Relations. Available online at: https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/chinas-massive-belt-and-road-initiative (accessed January 3, 2021).

Chaziza, M. (2018). China's Approach to Mediation in the Middle East: Between Conflict Resolution and Conflict Management. Washington, DC: Middle East Institute. Available online at: https://www.mei.edu/publications/chinas-approach-mediation-middle-east-between-conflict-resolution-and-conflict (accessed December 22, 2020).

Commission on State Fragility, Growth, and Development. (2018). Escaping the Fragility Trap. London: International Growth Centre. Available online at: https://www.theigc.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Escaping-the-fragility-trap_Oct-2020.pdf (accessed March 11, 2021).

de Carvalho, B., and de Coning, C. (2013). Rising Powers and the Future of Peacebuilding. NOREF Report. Oslo: Norwegian Peacebuilding Resource Centre.

de Coning, C., and Pradash, C. (2016). Peace Capacities Network Synthesis Report: Rising Powers and Peace Operations. Oslo: Norwegian Institute for International Affairs.

Devex (2017). Emerging Donors. Devex Reports. Available online at: https://pages_devexx.com/rs/devex/images/Devex_Reports_Emerging_Donors.pdf?alild=1803737004 (accessed September 15, 2020).

Devex (2020). Funding the Response to COVID-19: Analysis of Funding Opportunities. Available online at: https://public.tableau.com/profile/devexdevdata#!/vizhome/COVIDFundingvisualisation/COVID-19funding (accessed January 5, 2021).

Doyle, M. W. (2001). “War making and peace making: the United Nations' post-cold war record,” in Turbulent Peace: The Challenge of Managing International Conflict, ed C. A. Crocker, F. O. Hampson, and P. Aall (Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace Press), 529–560.

Esteves, P. (2019). “Brazil: the nexus between security and development,” in The New Politics of Aid: Emerging Donors and Conflict-Affected States, ed A. Paczyńska (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers), 89–104.

Final Communique of the Asian-African Conference of Bandung (1955). Final Communique of the Asian-African Conference of Bandung. Available online at: http://franke.uchicaco.edu/Final_Communique_Bandung_1955.pdf (accessed November 11, 2020).

Firchow, P. (2018). Reclaiming Everyday Peace: Local Voices in Measurement and Evaluation After War. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/9781108236140

Fung, C. J. (2016). China and the Responsibility to Protect: From Opposition to Advocacy. Peacebrief. Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace, 205, 1–5.

Ghimire, S. (2020). The Politics of Peacebuilding: Emerging Actors in Security Sector Reform in Conflict-Affected States. London: Routledge.

Gowan, R. (2020). China's Pragmatic Approach to UN Peacekeeping. Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution. Available online at: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/chinas-pragmatic-approach-to-un-peacekeeping/ (accessed December 22, 2020).

Gurganus, J. (2018). Russia: Playing a Geopolitical Game in Latin America. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Available online at: https://carnegieendowment.org/2018/05/03/russia-playing-geopolitical-game-in-latin-america-pub-76228 (accessed December 22, 2020).

Harig, C., and Kenkel, K. M. (2017). Are rising powers consistent or ambiguous foreign policy actors? Brazil, humanitarian intervention and the ‘graduation dilemma. Int. Affairs 93, 635–641. doi: 10.1093/ia/iix051

Herbst, J. E., and Marczak, J. (2019). Russian Intervention in Venezuela: What's at Stake? Washington, DC: Atlantic Council. Available online at: https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/report/russias-intervention-in-venezuela-whats-at-stake/ (accessed March 12, 2021).

Hirono, M. (2019). China's conflict mediation and the durability of the principle of non-interference: the case of post-2014 Afghanistan. China Quarterly 239, 614–634. doi: 10.1017/S0305741018001753

Hurley, J., Morris, S., and Portelance, G. (2018). Examining the Debt Implications of the Belt and Road Initiative from a Policy Perspective. SGD Policy Paper 121. Washington, DC: Center for Global Development. Available online at: https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/examining-debt-implications-belt-and-road-initiative-policy-perspective.pdf (accessed December 12, 2020).

Kenkel, K. M. (2016). Brazil and the Responsibility While Protecting Initiative. Oxford Research Group: Breaking the Cycle of Violence. Available online at: https://www.oxfordresearchgroup.org.uk/blog/brazil-and-the-responsibility-while-protecting-initiative (accessed January 4, 2021).

Kitano, N., and Miyabayash, Y. (2020). Estimating China's Foreign Aid: 2019–2020 Preliminary Figures. Tokyo: JICA Ogata Sadako Research Institute for Peace and Development. Available online at: https://www.jica.go.jp/jica-ri/publication/other/l75nbg000019o0pq-att/Estimating_Chinas_Foreign_Aid_2019-2020.pdf (accessed March 11, 2021).

Kuo, M. A. (2020). China and the Middle East: Conflict and Cooperation. The Diplomat. Available online at: https://thediplomat.com/2020/12/china-and-the-middle-east-conflict-and-cooperation (accessed January 5, 2021).

Kurzydlowski, C. (2020). What Can India Offer Africa? The Diplomat. Available online at: https://thediplomat.com/2020/06/what-can-india-offer-africa/ (accessed January 5, 2021).

Legarda, H. (2018). China as a Conflict Mediator: Maintaining Stability Along the Belt and Road. Berlin: Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS). Available online at: https://merics.org/en/short-analysis/china-conflict-mediator (accessed December 22, 2020).

Lekorwe, M., Chingwete, A., Okuru, M., and Samson, R. (2016). China's growing presence in Africa wins largely positive popular reviews. Afrobarometer Round Dispatch 122, 1–31. Available online at: https://afrobarometer.org/sites/default/files/publications/Dispatches/ab_r6_dispatchno122_perceptions_of_china_in_africa1.pdf (accessed March 12, 2021).

Lewis, D. G. (2020). Russia as Peacebuilder? Russia's Coercive Mediation Strategy. Garmisch-Partenkirchen: The George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies. Available online at: https://www.marshallcenter.org/en/publications/security-insights/russia-peacebuilder-russias-coercive-mediation-strategy-0 (accessed March 12, 2021).

Li, J. (2019). Conflict Mediation with Chinese Characteristics: How China Justifies Its Non-Interference Policy. Washington, DC: Stimson Center. Available online at: https://www.stimson.org/2019/conflict-mediation-chinese-characteristics-how-china-justifies-its-non-interference-policy/ (accessed December 22, 2020).

Luckham, R. (2017). Whose violence, whose security? can violence reduction and security work for poor, excluded and vulnerable people? Peacebuilding 5, 99–117. doi: 10.1080/21647259.2016.1277009

Mac Ginty, R., and Richmond, O.P. (2013). The local turn in peacebuilding: a critical agenda for peace. Third World Quarterly 34, 763–783. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2013.800750

Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analysis (2011a). India-Africa Strategic Dialogue Event Report. Available online at: https://idsa.in/event/IndiaAfricaStrategicDialogue_report (accessed January 5, 2021).

Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analysis (2011b). Second India-Africa Strategic Dialogue Concept Note. Available online at: https://idsa.in/event/SecondIndiaAfricaStrategicDialogue_conceptnote (accessed January 5, 2021).

Mawdsley, E. (2012). From Recipients to Donors: Emerging Powers and the Changing Development Landscape. London: Zed Books. doi: 10.5040/9781350220270

Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India (2020a). MOS Speaks on the India-Africa Forum Summit-IV at the 15th CII-EXIM Bank Digital Conclave on India Africa Project Partnership. Available online at: https://www.mea.gov.in/press-releases.htm?dtl/33056/MOS_speaks_on_the_IndiaAfrica_Forum_SummitIV_at_the_15th_CIIEXIM_Bank_Digital_Conclave_on_India_Africa_Project_Partnership (accessed January 5, 2021).

Ministry of External Affairs Government of India (2020b). Lucknow Declaration: 1st India Africa Defence Ministers Conclave, 2020. Available online at: https://mea.gov.in/bilateral-documents.htm?dtl/32378 (accessed January 5, 2021).

Ministry of External Affairs Government of India. (2020c). Speech by MOS at the 15th. CII-EXIM Bank India-Africa Project Partnership. Available online at: https://www.mea.gov.in/Speeches-Statements.htm?dtl/33052/ (accessed January 5, 2021).

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People's Republic of China (2020). Joint Statement of the Extraordinary China-Africa Summit On Solidarity Against COVID-19. Available online at: https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/zxxx_662805/t1789596.shtml (accessed January 5, 2021).

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation (2014). Concept of the Russian Federation's State Policy in the Area of International Development Assistance. https://www.mid.ru/en/foreign_policy/official_documents/-/asset_publisher/CptICkB6BZ29/content/id/64542 (accessed 21 December 2020).

Mohan, G. (2016). Modernizing India's Approach to Peacekeeping: The Case of South Sudan. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Available online at: https://www.gppi.net/2016/10/04/modernizing-indias-approach-to-peacekeeping-the-case-of-south-sudan (accessed January 5, 2021).

Mthembu, P. (2018). China and India's Development Cooperation in Africa: The Rise of Southern Powers. London: Palgrave MacMillan. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-69502-0

Mukherjee, A. (2015). At the Crossroads: India and the Future of UN Peacekeeping in Africa. Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution. Available online at: https://www.brookings.edu/research/at-the-crossroads-india-and-the-future-of-un-peacekeeping-in-africa/ (accessed November 15, 2020).

Paczyńska, A. (2016). “Emerging and traditional donors and conflict-affected states: the new politics of reconstruction, in Changing Landscape of Assistance to Conflict- Affected States: Emerging and Traditional Donors and Opportunities for Collaboration, ed A. Paczyńska (Washington, DC: The Stimson Center), 1–13.

Paczyńska, A. (2019). The New Politics of Aid: Emerging Donors and Conflict-Affected States. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.