95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci. , 12 August 2021

Sec. Comparative Governance

Volume 3 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2021.662245

This article is part of the Research Topic "Performing Control" of the Covid-19 Crisis View all 12 articles

This article analyses how specific nodal points of performative control developed and consequently structured the discourse on Aotearoa New Zealand’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. It identifies these points by adopting a rhetorical-performative approach to uncover three particular performances of control that articulated the pandemic in Aotearoa New Zealand, from the diagnosis of the first COVID-19 case in the country in February 2020 through to October 2020. This period of analysis covers the emergence, subsequent nationwide lockdown, elimination, and re-emergence of the virus. There are three distinct nodal points that unfold as key to the nation’s ability to control COVID-19: the hegemonic “us”; iwi regionalism; and the rhetoric of kindness. A mixed approach of content analysis of government data, Facebook data, and key imagery is employed to constitute these nodal points’ relevance and how they structured the performative control that threaded through the nation’s initial response as a whole. The article demonstrates how Aotearoa New Zealand, considered by popular assessment to have been successful in its response to COVID-19, managed to eliminate the virus twice in 2020, but not without aspects of the antagonisms that have beset other nations. These include the exacerbation of internal dichotomies and questions about the legality of Government mandates. As the country’s response to COVID-19 is traced, the employment of a rhetorical-performative framework to identify the key nodal points also highlights how the framework could be applied to Aotearoa New Zealand’s continuing response as the pandemic endures.

International assessments of Aotearoa New Zealand’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic have been of a job well done. However, there were frictions evident in New Zealand society as a result of its response. Discursively read, as is done here from a Laclaudian-Mouffean (1985; c.f. Howarth, 2018; Palonen, 2018) perspective, internal antagonisms led to hegemonic struggles that were prevalent throughout the course of 2020. Aotearoa New Zealand was not unique in its performances of control, and contestations of performativeness, in response to the pandemic. The rapid transmission of the virus meant that despite its geographical isolation and relatively low population density, the country had to quickly consider enforcing the same public restrictions as other nations in a bid to limit the virus’s potential spread in the community. It also meant that Aotearoa New Zealand was just as susceptible to the political nature of the virus that led to the stigmatization of others, particularly based on ethnicity, and the curbing in of previously exceptional nationalistic tropes (Roberto et al., 2020).

This article presents a rhetorical-performative analysis, based on Ernesto Laclau’s poststructuralist discourse theory and then developed by Emilia Palonen (2018), of Aotearoa New Zealand’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. This enables the use of nodal points, which are moments that can inhabit the center of a discourse and provide both meaning and nodal linkages (Laclau and Mouffe, 1985). Thus, this article identifies three key nodal points that articulated the logics of the pandemic in Aotearoa New Zealand via performative control, and structured the discourse of its response to COVID-19. By articulating the hegemonic “us”, iwi regionalism—in this case, those in Māori tribal areas asserting regional border enforcement—and the rhetoric of kindness as crucial nodal points, the article provides a unique viewpoint to Aotearoa New Zealand’s widely acclaimed COVID-19 response. Particularly the first nodal point highlights the argument Palonen has advanced that for Laclau and Mouffe, it is the “us” that is in itself a temporary performative articulation—here, countering COVID-19—and its temporary state is specifically of importance (Palonen, 2021).

Although there are studies that discuss aspects of Aotearoa New Zealand’s socio-political landscape via post-foundational and specifically Essex School—based frames of reference (Stuart, 2003; Phelan and Shearer, 2009; Tregidga et al., 2014; Salter, 2016; Horvath, 2018), there has not been the range of examination applied using such a framework as there are in particularly Europe and the Americas. In current Kiwi political science literature, wider aspects of the Essex School have successfully enhanced knowledge of polarization (Satherley et al., 2020); populism, or at least the lack thereof of a radical right (Donovan, 2020); and gender (Golder et al., 2019). Here, the utilization of a rhetorical-performative analysis through which to interrogate Aotearoa New Zealand’s COVID-19 response allows the identification of meaning-making and discourses that are unique to the country. Further, the conflict that exists within the Kiwi response, including the bringing of a court case questioning the legality of the lockdown and the subsequent judgment, is an affirmation that Aotearoa New Zealand’s version of democracy is robust and “inhabited by pluralism” (Mouffe, 2000, p. 34). Demonstrating that there is space for disagreement even in the pandemic period, it is in line with the radically democratic perspective to democracy that contests the role of consensus as a basis of democracy and highlights taking stands, and even disagreeing (Mouffe, 2005). The radical democratic perspective of Mouffe that positively endorses disagreement is a unique lens through which to view Aotearoa New Zealand’s version of democracy, especially considering the emphasis on consensus within the nation’s pandemic response. However, positively viewing the disagreements that do exist allows us to highlight crucial dimensions of the nation’s democracy that might otherwise be difficult to open up.

The literature on Aotearoa New Zealand’s COVID-19 response has emphasized the country’s initially successful approach that led to it declaring its elimination of the virus on 8 June 2020. The country has been highlighted as one from which lessons can be learnt, alongside similar relatively efficacious countries such as Taiwan, Iceland, and Singapore (Foudaa et al., 2020; Summers, et al., 2020). Others have highlighted Māori mobilization (Dutta et al., 2020; McMeeking and Savage, 2020), and particularly Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern’s effective crisis communication and leadership (McGuire et al., 2020; Wilson, 2020). The politicization of the virus via the heavily partisan nationalistic, diasporic, and prejudicial race-based discourses that framed some overseas responses to the virus (see, in particular, Linnamäki’s and Chiruta’s contributions to this Research Topic) are not as apparent in Aotearoa New Zealand. This inclusive hegemonic articulation (Palonen, 2021) has been one of the peculiarities of the nation’s response; however, battles of discursive togetherness are still in evidence. Based on a sustained study of online ethnography of Aotearoa New Zealand’s COVID-19 response and overlaid with a rhetorical-performative analysis, the key contribution of this article is to unveil and investigate the diverse moments of performative control that structured Aotearoa New Zealand’s pandemic discourse, and identify how they emerged.

The article begins by outlining its theoretical framework, operationalizing aspects founded in Laclau’s and Mouffe’s construction of discourse, concept of hegemony, and frontiers building into a rhetorical-performative analysis of the performative control of the COVID-19 crisis in Aotearoa New Zealand. The powerful argument of Laclaudian-Mouffean analysis is that any political community ought not to be taken for granted and always seeks articulation (Palonen, 2021). In a crisis situation, communities are performed through a rhetoric of unity, and sometimes difference, in order to perform said crisis, as is the ethos in this Research Topic. Highlighting Aotearoa New Zealand to investigate performances of control allows turning to community-forming practices and rhetoric, and this framework is contextualized in the Results section. After the outline, I continue by identifying key nodal points, in part via official Facebook images, that also work to perform meaning-making and help to articulate performative control (Palonen, 2018) in Aotearoa New Zealand’s experience of the pandemic. These nodal points highlight the control that must be performed in a crisis such as a pandemic, but in doing so I argue that these particular nodal points are a distinctively Kiwi response to the threat of COVID-19 that have served to reinforce the nation’s constructed identity. The article concludes with a short discussion and offers ideas for future research.

This research resulted from contextualizing Aotearoa New Zealand’s response via online ethnography (Hjorth, 2016) of majority Aotearoa New Zealand—based news websites. As a Kiwi living in Finland, which had its own relatively lauded path in responding to COVID-19 in 2020, the critical distance to my home country as a case study enabled a unique perspective that has made the nodal points identified particularly clear against a European context.

I concentrate the operationalization of a discursive framework onto the material used for this article, which comprises of publicly accessible mixed data, to articulate the discursive lens through which the key nodal points are identified. These include Facebook, which was a vital communication channel for the Government, especially in the first nationwide lockdown; government agency data and official websites; and national and international media analysis, for the time period 26 February 2020 – 7 October 2020. The material collected from this period includes images from public Facebook posts, domestic media articles, and the Ministry of Health’s detailed COVID-19 case details database. The start of this date selection marks the diagnosis of the first confirmed case of COVID-19 in Aotearoa New Zealand, which made it the 48th nation worldwide to have a confirmed case (Ministry of Health, 2020b). The end of the date selection is when the whole of the country returned, after an outbreak of community transmission, to Alert Level 1, the least serious level within the adopted alert level framework.

In order to analyze the data and understand the particularities and dominant Kiwi narratives of COVID-19 and the performance of control, I utilize a rhetorical-performative analysis based on postfoundational discourse theory (Palonen, 2018). This relies particularly on Laclau’s and Mouffe’s theory of discourse to conceptualize discourse, hegemony, and identity (Laclau and Mouffe, 1985). This approach is sensitive to transformations in the “discursive field”, composed of meanings that are unevenly laid out and crisscrossed with antagonism (Ibid., p. 105). This means that political forces as well as citizen groups always need to articulate meanings and fix their relations in the discursive field through nodal points—i.e., the privileged signs around which other signs are ordered (Jørgenson and Phillips, 2002). Although nodal points initially lack meaning in and of themselves, through articulation they are constructed as important discursive signs, even though it is not possible to permanently connect the meaning of any of the elements to a conclusive actuality (Jørgenson and Phillips, 2002, p. 28). The role of the analyst is to locate those nodal points that are central in the discursive field, shared by or competed over by several political forces that would enable them to enhance our knowledge of the logics of articulation in this case (Palonen, 2019). In this way, the three nodal points that are located are also subject to identity changes and could be otherwise identified depending on which discursive meanings they can connect with. Likewise, the notion of performative control can also identify differently relative to its ability to connect with discursive meanings. If to be performative only exists relative to its ability to be performed (Butler, 1988), then the performance of control can only siphon meaning via its relation to discursive meaning. As such, meaning-making is performed across multiple articulations, including the rhetoric and imagery concentrated on in this article (Palonen, 2018).

In order to fully understand the development of the discursive field in Aotearoa New Zealand during the COVID-19 pandemic and performances of control by key actors, I will next go through an overview of the pandemic in the country and Government responses to it. Then I will analyze in more detail how central nodal points were formed, and what their political roles were during the pandemic.

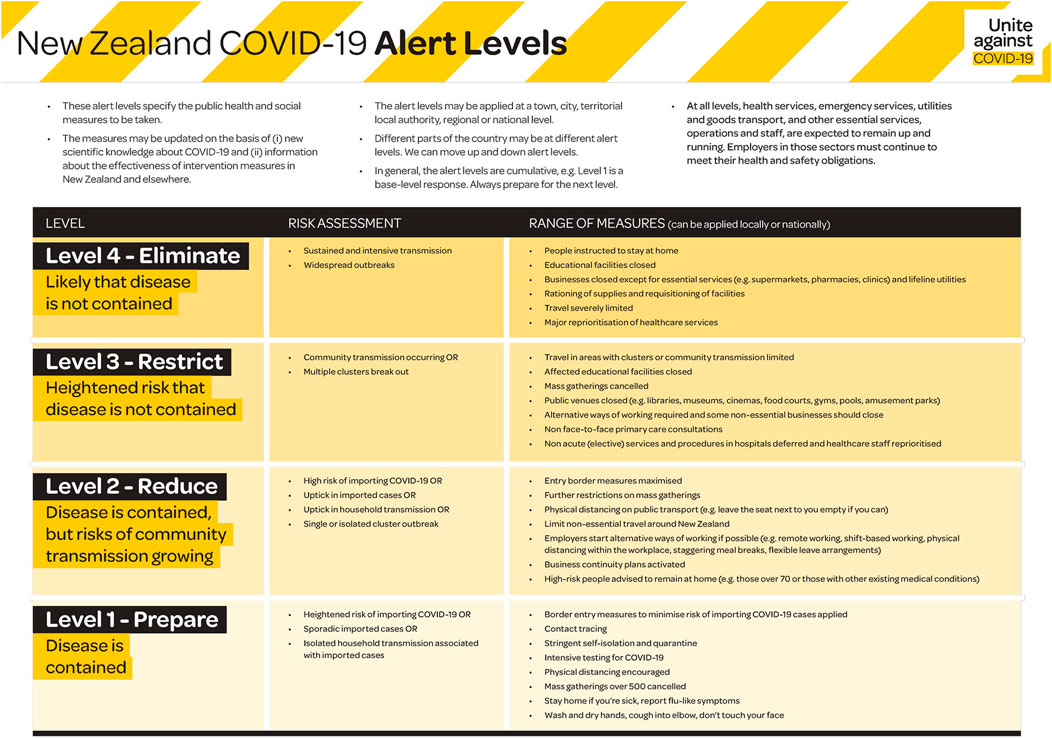

The control performed by the Government in response to the emerging threat of COVID-19 developed in a cautious manner that was benefitted by Aotearoa New Zealand’s geographic boundaries and isolation in the South Pacific. With 28 cases confirmed by 19 March 2020, all from overseas arrivals, the Prime Minister announced that the country’s borders would be closed to incoming arrivals, apart from citizens and permanent residents and their partners and/or children (Radio New Zealand 2020a). This was a historic move. The four-tier alert level system shown in Figure 1, similar to Singapore’s Disease Outbreak Response System Condition model, was announced on 21 March as the Government’s control framework based on the spread and severity of the virus, and the country was placed at Alert Level 2 (Abdullah and Kim, 2020). The immediate elevation of the country to Alert Level 2 indicated not only that the Government was not wary of performing control via immediately implementing an increased alert level, but also that the virus had already broken control of the barriers set up days and weeks earlier to prevent its spread.

FIGURE 1. New Zealand’s framework of COVID-19 alert levels. Source: New Zealand Government’s Unite against COVID-19 Facebook page, 21 March 2020.

With Aotearoa New Zealand’s first case of community transmission confirmed on 23 March and an increase of confirmed cases to 102, the country moved to Alert Level 3, with the Prime Minister stating that the country would move to Alert Level 4—i.e., a nationwide lockdown—at midnight on 25 March (Ardern, 2020a). It meant that all educational facilities and non-essential services were closed, and the idea of a personal household “bubble” within which people could interact entered the national vernacular.

An exceptional control lever was applied, with a State of National Emergency in force from 25 March until 13 May 2020, with each 7-day state extended seven times (New Zealand Government, 2020). The level of control that this enabled is a rare occurrence for the nation; it was the second-ever declared its history, the first being after the 2011 Christchurch earthquakes. The declaration of the State of National Emergency, in combination with the issuance of an Epidemic Notice the same day and subsequently a number of Orders under the Health Act, empowered the Government, the police, and other public servants with wide-ranging powers, the likes of which had not been seen for over 60 years (Science Media Centre, 2020).

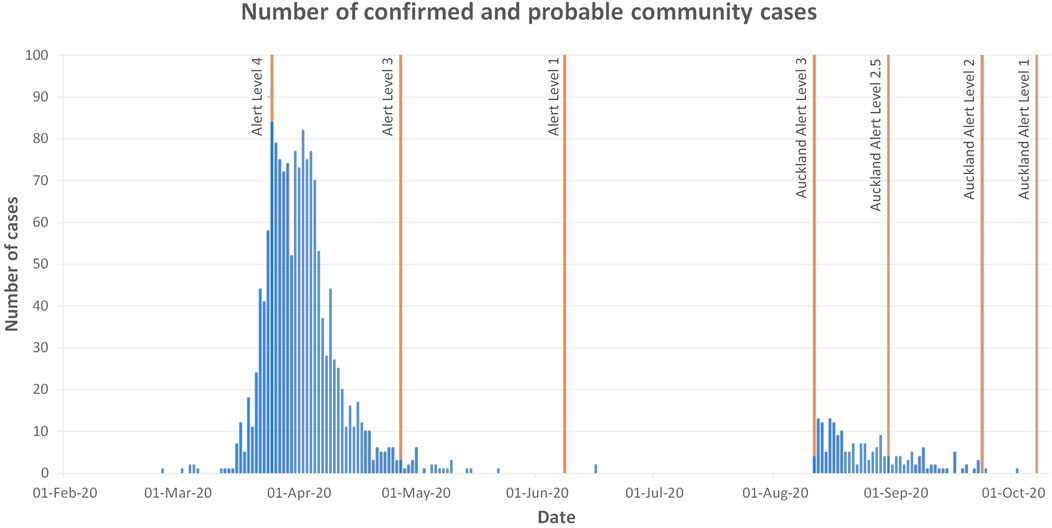

The nationwide lockdown did not immediately impact the virus’s spread. Similar to other affected countries, particularly in Europe, the transmission chains of the virus were spread throughout the country, but were particularly high in tourist areas, and across age groups where large private occasions—for example, weddings—took place (Robert, 2020). Aotearoa New Zealand had its first fatality caused by COVID-19 on 29 March, and by 2 April the number of new cases reached its daily peak of 82 new cases, with 899 total cases (Ministry of Health, 2021a). However, as Figure 2 demonstrates, although the effect of the nationwide lockdown did not occur straight away, its success could be seen in the relative brevity of Alert Level 4.

FIGURE 2. New Zealand’s confirmed and probable community cases of COVID-19 from 26 February 2020 to 7 October 2020 and corresponding alert levels. Before 17 June 2020, cases at the border were included in the total of the relevant district health board. Source: Data is from the New Zealand Ministry of Health, 31 January 2021.

With Parliament adjourned (due to the nationwide lockdown) on 25 March until 28 April, an important signifier of the bipartisan political response to COVID-19 was established: the Epidemic Response Committee, which existed until 26 May. The online-based committee of MPs was chaired by the then Leader of the Opposition, Simon Bridges, with its purpose to scrutinize both legislation in the absence of Parliament, and Government and official decisions related to the COVID-19 pandemic, given the range of powers and control enacted under the State of National Emergency. The organized and comparatively consensual national response demonstrated the political center that Aotearoa New Zealand still has today, different to most modern democracies that the country tends to compare itself to that nowadays tend to have a split center.

However, the control the committee could exercise was tested. First, its ability to summon witnesses was challenged when the Minister of Tourism, Kelvin Davis, cancelled a scheduled appearance before the committee, days after he had been “grilled” at the committee (Brunton, 2020). Instead, the Minister appeared on a Facebook Live event, giving credence to the notion of the Government seeking to highlight its own preferred avenues of communication, particularly Facebook (Coughlan, 2020). Here, the control lay with the Minister, who did not schedule a make-up appearance, instead of with the committee charged with parliamentary oversight.

The committee’s lack of control was emphasized by Government members again once Parliament resumed. Despite the committee still being active, the then Leader of the Opposition tweeted an email from a ministerial advisor to Ministers counseling them to decline invitations from the Epidemic Response Committee (Bridges, 2020a). The rational provided was that Parliament’s other select committees were functioning again and Ministers should prioritize them (Devlin, 2020); however, it also displays the lack of control of the committee overall. Despite the committee being set up as a parliamentary substitute, in reality the Government’s focus was on its own communication via press briefings and the Prime Minister’s Facebook interactions. Given the ability of Ministers to reject appearing before it, the Epidemic Response Committee could instead be seen as the Government performing the impression of bipartisanship, when in fact the control itself was concentrated, at least in terms of the public face of the pandemic, on the Prime Minister and the Director-General of Health, Ashley Bloomfield.

With varying levels of compliance regarding a requirement since 14 March for arrivals in the country to self-isolate, by 9 April the Government announced that all citizens and permanent residents travelling to Aotearoa New Zealand would have to enter 2 weeks of publicly-funded Managed Isolation Quarantine (MIQ) at hotels that were turned into guarded facilities, with returnees monitored and mostly confined to their rooms for the duration of their stay (Ministry of Business, Innovation, and Employment, 2020). With daily cases declining, on 27 April the country moved down to Alert Level 3; although the country did not have zero cases overall, the virus had been eliminated from a public health perspective, as any new cases could be contact-traced (Bloomfield, 2020). On 8 June, the country moved to Alert Level 1, with no active cases in the community and all constraints essentially removed, bar those at the border. Aotearoa New Zealand was officially free of COVID-19, with its last remaining confirmed case recovered and it having been 17 days since a case was diagnosed. However, on 11 August, following 102 days without any community transmission of COVID-19, four cases from within one family were confirmed (Ministry of Health, 2020a). This saw the Auckland region, where the cases were based, moved back to Alert Level 3, whilst the rest of the country moved up to Alert Level 2. At the time of writing, the source of the cluster, which led to 179 new cases from community transmission, has not been identified (Ministry of Health, 2021b).

Opposition MPs, particularly the leader of the right-wing ACT party, questioned the legality of the police attempting to restrict residents to their suburbs during Alert Level 4 (MacLennan, 2020). This questioning was borne out when the validity of the initial stages of Aotearoa New Zealand’s lockdown were challenged in the High Court by a former legislative drafter, who was concerned not about the necessity for a lockdown but about the legality of it. The court ruled in August 2020 in favor of one of the three causes of action that had been brought, stating that although the lockdown was required and reasonable, it was contrary to Aotearoa New Zealand’s Bill of Rights and not authorized under the law (Borrowdale v Director-General of Health, 2020). An order by the Director-General of Health, under section 70 of the Health Act, enforcing the lockdown restrictions was not made until 3 April, making the directives to stay home—which, in its evidence, the Government stated were intended to be informative and were merely guidance—unlawful for the 9 days prior (Ibid). Without having the legal strength behind the directives to stay at home, instead the control used by the Government was a reliance on fear of the virus to motivate people to limit their personal movements. Compliance with what were presented to the public as legal requirements instead relied on a collective will to fight the virus’s spread.

In response to the judgment, the Attorney-General ascertained that “In the end the measures taken by the government worked to eliminate COVID-19” (Parker, 2020). The discipline and adherence to the rule of law that was emphasized in the early days of the lockdown did not apply to the Government in what is a fragile stage in any democracy: a state of the exception. The public health emergency and the steps taken to eliminate the virus in Aotearoa New Zealand led to an emphasis of the uniqueness of the situation, with the Prime Minister stating that there is no rule book for a pandemic (Young, 2020). The antagonism that the court ruling discloses can be framed in anti-elitist terms: the Government, as “the elite”, utilized hegemonic decision making that was outside its legal remit to ensure that what it thought was best for “the people” was enacted by community consensus to follow the Government’s “strong signals, guidance and nudges” (Knight, 2020). The Government’s approach to “go hard and go early” (Ardern, 2020b) was initially vindicated with the elimination of community transmission of cases by the end of April 2020, but this does not repudiate the lack of legality in the first days of Alert Level 4. However, the conflict that exists with the bringing of the court case and the subsequent judgment is an affirmation that New Zealand’s version of democracy is robust and “inhabited by pluralism” (Mouffe, 2000, p. 34). Demonstrating there was space for disagreement even in the pandemic period, it is in line with the radically democratic perspective to democracy that contests the role of consensus as a basis of democracy and highlights taking stands, and even disagreeing (Mouffe, 2005).

With cases declining, Auckland moved to a modified “Alert Level 2.5” on 30 August and to Alert Level 2 on 23 September, with the remainder of the country moving to Alert Level 1 on 21 September. Auckland joined Alert Level 1 on 7 October (New Zealand Government 2021). The pandemic seemed to be over again. Next, I will turn to the particular nodal points that performed a significant role in the discursive field during the analyzed pandemic period.

COVID-19 has seen a rearticulation of Aotearoa New Zealand as a nation, perhaps as imposed by its geographic boundaries—being an isolated set of islands—as by any party-political speak since the start of the pandemic. The ease with which the country can physically bar any person or form of transport at its borders inherently feeds into an us vs. them dichotomy. Aotearoa New Zealand’s physical isolation has meant that such a dichotomy has always existed to a degree; however, its realization as nationalism tends to be inconspicuous at best. Since the signing of the divisive Treaty of Waitangi in 1840 until the latter quarter of the 20th century, the overriding tenets of Aotearoa New Zealand’s culture stemmed from the United Kingdom. Burgeoning multiculturalism and especially a growing appreciation and regard for the Māori culture has seen a unique character evolve, but these bonds are complex and problematic, and dominate late-night radio talkback.

This evolution has hastened in recent years by two tragedies that will continue to affect the long-term character of the nation: the Christchurch mosque terrorist attacks on 15 March 2019, and the Whakaari/White Island volcanic eruption on 9 December 2019. Both had already brought about versions of a “new normal” for Aotearoa New Zealand, such as more police bearing arms and increased unease about the relationship between the volatile nature of the country’s geography and its biggest export industry, which is tourism. The COVID-19 pandemic has brought about another perceptible shift in the nation’s consciousness. The ability to control Aotearoa New Zealand’s borders as part of its COVID-19 response has fed a “curbing in” of the country’s latent nationalism. Ethnonationalism became more pronounced. This was seemingly predicted in the early stages of the pandemic, with the Director-General of Health feeling compelled to emphasize the Kiwi citizenship of the first diagnosed cases (Stuff, 2020).

There is a complicated duality to the emergent state nationalism, or identification of the hegemonic “us”, in Aotearoa New Zealand during the pandemic that has also been witnessed worldwide. Its affective force encouraged compliance with Government mandates for the benefit of fellow Kiwis; however, it has also led to an othering of not only other countries but also those returning to Aotearoa New Zealand (Antonsich, 2020). This identification is not necessarily fixed; “the people” is not a demographic category, but the role of politics is to generate such a temporary “us” (Palonen, 2021). The majority of returnees are citizens or permanent residents, but there is a sense of exclusion as to their role in the task of preventing COVID-19’s spread. It is a duality that is reflected throughout the country’s COVID-19 experience, as it was both the Government’s comparatively swift and complete national lockdown as well as its geographical borders that formed its successful defensive structure against the virus.

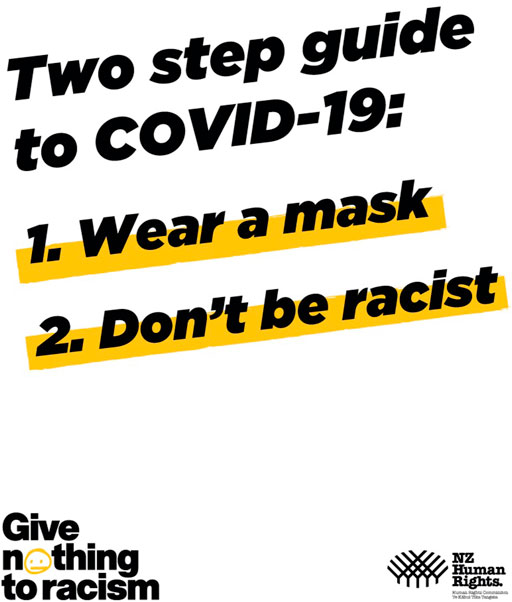

Such othering continued to spread internally in the nation. Reports of racist incidents against the Asian community related to COVID-19 encouraged the Human Rights Commission to launch its “Racism is No Joke” campaign in July 2020, extending its previous “Give Nothing to Racism” campaign (Human Rights Commission, 2020). Figure 3 from the Human Rights Commission’s Facebook page shows one of its campaign images, attempting to ensure people do not conflate the virus with racial linkages as to who has it or where it came from. Prejudice intensified following the cluster that emerged in South Auckland on 11 August 2020, which ended Aotearoa New Zealand’s 102-day COVID-19—free streak. However, the focus changed when the family at the center of the cluster was identified as Pasifika, in part because the area of South Auckland itself is stereotyped as low-income and predominantly made up of Māori and Pacific Islanders. A rumor was posted on Reddit as to how the virus had entered the community that, despite being deleted hours later, spread throughout social media (Farrier, 2020). The rumor led to a Facebook post on 15 August on a conspiracy theory page “Expose Hatred in NZ” that leant heavily into the stigmatization and prejudices that some within the nation’s hegemony negatively associate with Māori and Pacific Islanders, including of single motherhood, breaking the law, unemployment, and being familiar to government agencies (Ibid). Interim Minister of Health Chris Hipkins denounced the rumor as comprising “vile slurs” (Deguara, 2020). Stigmatization of those who were deemed based on ethnicity to be outside the hegemonic “us”—the 70 percent of Kiwis who identify as of European descent (Statistics New Zealand, 2020)—is part of what leads to the development of this nodal point as an important part of Aotearoa New Zealand’s COVID-19 response, especially as it feeds into the two other identified nodal points, through discrimination and a lack of kindness.

FIGURE 3. Give Nothing to Racism Campaign. Source: New Zealand Human Rights Commission Facebook page, 2 March 2020.

It was a signification of hegemony and of “othering” that are both underlying tensions in Aotearoa New Zealand at all times amongst socioeconomic and cultural subsets, but was particularly obvious with the cluster outbreak. By singling out a family as deliberately behaving against Aotearoa New Zealand’s best interests and by focusing on their socio-cultural background and where they lived, it embodied a lack of societal unity that was an antithesis of Aotearoa New Zealand’s COVID-19 strategy. It was exacerbated by the then Deputy Prime Minister—and leader of New Zealand First, the country’s closest example of a right-wing populist political party—Winston Peters claiming to Australian media days earlier that he had heard from a journalist that the cluster had originated via a quarantine breach (New Zealand Herald, 2020). Both Government Ministers and agencies refuted the rumor and repeated pleas for people to trust official sources regarding COVID-19. It was a rare moment in Aotearoa New Zealand’s COVID-19 experience where the control of discourse regarding the virus was lost by the authorities, especially as it was further exacerbated by the Prime Minister’s own deputy. It also displayed a level of distrust with the Government and the information being provided to the public.

Health authorities were compelled to clarify, for example, that at least the second case that was diagnosed in Aotearoa New Zealand involved specifically “a Kiwi family” after they faced sustained abuse on social media (Martin, 2020). The threat of moralism and stigmatization on those who have had the virus has been a continual undercurrent in Aotearoa New Zealand since the pandemic started. Initially there was an “othering” of non-Kiwis when the pandemic first began to threaten Aotearoa New Zealand’s borders; however, it was internalized and exacerbated with the South Auckland cluster. The discovery of the cluster led to the greater Auckland area moving to Alert Level 3, and the rest of the country to Alert Level 2, on 12 August until 30 August in an attempt to control the outbreak (Ministry of Health, 2020a). The exceptionalism of the Auckland region was not new—the common derogatory vernacular for an Aucklander throughout the rest of the country is JAFA, or Just Another Fucking Aucklander (Bardsley, 2014)—but the sociological and physical divide (with travel between Auckland and other regions severely restricted) was, and it led to both a forced and metaphorical regional curbing in by the rest of the country. The rhetoric of unity was somewhat splintered with the exceptionality of the Auckland region; however, as is detailed via the next nodal point, it was not for the first time during the nation’s lockdowns.

The hegemonic “us” that has been detailed stands out for Aotearoa New Zealand, as the country has not experienced the same contemporary swell in radical right-wing politics as the democracies it is often compared with. This is its importance as a nodal point that gave structure to the nation’s response, and it developed alongside the evolution of the virus in Aotearoa New Zealand, intensifying as case numbers intensified. It also splinters the egalitarian sociopolitical structure that the country prides itself in. The inherently exclusionary actions that led the nation’s response to the virus, such as the closing of borders, fed a narrative of stigmatization and rumor-mongering that picks up on Laclau’s and Mouffe’s logic of equivalence (Laclau and Mouffe, 1985), but the antagonism was fractured between the hegemonic “us” and those in the ethnic minority assumed to not be citizens, or the “others”.

Aotearoa New Zealand’s domestic politics are structured in an outwardly straightforward manner, with its three governmental tiers of Parliament, regional councils, and local councils. However, multiple tensions exist within each of these tiers, particularly around the incorporation of tikanga Māori (generally defined as Māori cultural practices) and specific Māori representation at all levels of government. The institutional antagonisms that exist cause Māori to be inherently apprehensive of most Government mandates, and any performativity of statehood by iwi (Māori tribes) tends to be at a local level, apart from when Treaty of Waitangi settlements are made. In pre-colonial times tribal boundaries were constantly disputed antagonistic frontiers, and even today they often overlap; regardless, they are superseded at a national level by designated Māori seats in Parliament, of which there are seven out of the usual 120 seats that constitute Parliament. The real political power for iwi comes from Treaty of Waitangi settlements—compensation for losses stemming from the Treaty—and the subsequent apologies and return of assets included with the settlements. However, this does not compensate for the worse health outcomes that Māori tend to experience, compared with Pākehā (non-Māori) (Graham and Masters-Awatere, 2020).

With the borders closed, the coronavirus narrative shifted inwards and highlighted already existing social and cultural divides. The day before the nationwide lockdown, iwi in some parts of the country began setting up roadblocks on main roads into their area, questioning those driving into the area as to their purpose for travel. This mobilization was motivated by reported hostile treatment in the state health sector, and was borne out with Māori 50 percent more likely to die from COVID-19 than Pākehā (Steyn, et al., 2020). Additionally, the roadblocks were focused in geographically isolated areas that had fewer public health services available.

In the Bay of Plenty, on the East Coast of the North Island, the iwi Te Whānau-ā-Apanui was the first to announce their intentions to block entry into their area to non-residents and non-essential workers, with community members manning the western and eastern borders into the area 24 h a day (Hurihanganui, 2020). In the Northland/Te Tai Tokerau area of the North Island, a roadblock was set up on the main state highway into the area. When asked as to the legality of the roadblocks, the Deputy Police Commissioner emphasized the importance of supporting the cultural response (Radio New Zealand, 2020b). The roadblocks can be seen as a microcosm of the wider national pandemic response; early on in the pandemic the shortage of ventilators countrywide was emphasized as a cause for the “go hard and go early” approach (Dutta et al., 2020).

Imagery around the roadblocks had stark contrasts. Photos from May 2020 from the public Facebook pages of now Māori Party members of Parliament Debbie Ngarewa-Packer and Rawiri Waititi show the roadblocks as running collegially with police present, inquiring as to travelers’ reasons for moving within regions during a period of heavy restrictions (during Alert Level 3). Conversely, the New Zealand First party’s Facebook page took a deliberately more divisive image of men physically blocking the road, no police presence, and the national Māori—or tino rangatiratanga; Māori sovereignty—flag displayed. The legality of the roadblocks were debated in the media, and images such as the New Zealand First one worked to emphasize already existing antagonisms. Māori manning the roadblocks were likened to “empowered mobs” and “vigilante thugs”, with a talkback radio host labelled the actions as “silly … bullshit … all about separatism.” (Jackson, 2020; Peacock, 2020). Checkpoints were instigated in other areas of the North Island during Alert Levels 3 and 4, although by the end of April they had reduced to single figures (Burrows, 2020). Anxiety about the virus, a desire to protect communities with predominantly Māori demographics, and a lack of trust regarding the ability or will of authorities to aid Māori, led to iwi exerting their own performance of control over the virus (Dutta et al., 2020).

The roadblocks not only constituted a performative practice of control by a vulnerable population in isolated areas, but also they were a symbol of meaning-making sovereignty for Māori. It was a representation of tino rangatiratanga by iwi, which is a regular cleavage in Aotearoa New Zealand’s domestic politics. This was emphasized in a meeting of the Epidemic Response Committee: when the Chair stated that the roadblocks were unlawful in every context, the Police Commissioner disputed that (Harris and Williams, 2020). The hegemonic rhetoric surrounding the checkpoints also reflected division, possibly for the purpose of preventing stigmatization. Both the Prime Minister and the Police Commissioner initially referred to the roadblocks as variations on “community-led checkpoints”, instead of iwi-led (Dutta et al., 2020), homogenizing the checkpoints and the iwi manning them. Regardless, the fact that the police framed their response as merely visitations to the roadblocks showed that much of the discursive power lay with iwi. It also feeds into the logic of who can define borders. Aotearoa New Zealand is not required to engage in space-claiming practices to constitute its borders; they are geographically set. Perhaps this makes the contestation of borders within the nation more antagonistic; however, many iwi boundaries predate colonial settlement. The split in the country’s collective unity that the roadblocks signified was a shift in the narrative, from blame on those bringing the virus into the country to targeting those who were attempting to reduce the potential spread of the virus within their own communities in Aotearoa New Zealand.

The two main mediums used for communication and engaging with the public by the Government, particularly during the nationwide lockdown, were televised press briefings and Facebook. There were near daily 1pm press conferences on weekdays over the course of the virus’s emergence in Aotearoa New Zealand and the subsequent lockdown, with the Prime Minister and the Director-General of Health updating the country on the latest COVD-19 figures and allowing time for questions from reporters. They became a fixture of lockdown when the majority of people were at home, and made a national celebrity out of Bloomfield. The continuity of having, for the most part, Ardern and Bloomfield present the Government’s communications increased the perception of consistent and stable control over the pandemic. A survey conducted by Massey University after the first nationwide lockdown had Ardern’s communication rated at 8.45 out of 10, and Bloomfield’s as 8.19 out of 10 (Thaker and Menon, 2020).

However, there was a missing link between the Prime Minister’s consistent appearances on Facebook and the willingness of other Ministers to speak, especially during the nationwide lockdown, with local media outlets reporting in May that they had been denied the ability to interview relevant Ministers, with only the top-ranking Ministers available to speak to the media (Manch, 2020). The Government’s belief in its level of control over its pandemic response was highlighted by an email from one of the Prime Minister’s advisors that was forwarded to unintended recipients in May 2020, in which colleagues were told “There’s no real need to defend. Because the public have confidence in what has been achieved and what the Govt is doing. Instead, we can dismiss,” (Manch, 2020). With rhetoric of any kind dismissed, instead reliance was on the performance of control having been accepted by the public.

The second main avenue of communication that the Prime Minister used was Facebook Live. This was not new, as Ardern often provided short updates or condensed versions of recently announced policies, along with the live streaming of press conferences and major parliamentary speeches, such as the Budget. Aotearoa New Zealand has a history of expecting its leaders—not only political, but across all spheres—to be unpretentious and casual no matter the context, to ensure that they are still one of “us” (Holmes et al., 2017). The use of Facebook Live during the pandemic exemplified the “all in this together” narrative with an intimate, spontaneous conversation of sorts with the Prime Minister, who interspersed repetition of pandemic-related announcements and key messages with answering viewer questions (Ardern, 2020a).

It also aided in bridging the traditional limitations female leaders face regarding the gendered divide between public vs. private, and politics vs. domestic (Johnson and Williams, 2020), as via the Facebook Lives Ardern delivered targeted messaging on the controls the Government was leveraging to minimize the risk of infection from her Wellington-based home, in a lounge chair and apologizing for her casual wear (Ardern, 2020c). What could be seen as a particular, domestic performativity of gender was counterbalanced with some of the Facebook Lives and of course press briefings being conducted in more formal business wear, maintaining the balance between care and authority that is not required of male political leaders. The gendered leadership style was emphasized by the media highlighting of countries led by women being considered more successful at managing the pandemic—commonly cited examples, along with Aotearoa New Zealand, are Denmark, Finland, Germany, Iceland, Norway, and Taiwan. The balance between politics and the domestic not only accentuated the “fictive solidity” of gender and leadership (Hey, 2006), but also the certain solidity of performative camaraderie and of ensuring that Kiwis viewed the Prime Minister—and, therefore, the Government and other pandemic decision-makers—as one of “us”. This “us” performativity and its consistent employment in Government rhetoric, most obviously with the “team of five million” refrain as seen in Figure 4, was crucial for aiding in public compliance with the lockdown restrictions, as it fostered a sense of collegiately amongst the nationwide community.

FIGURE 4. Messaging from the New Zealand Government. Source: Nelson City Council Facebook page, 25 March 2020; Unite against COVID-19 Facebook page, 14 May 2020 and 21 March 2020.

The use of Facebook as a main communication channel not only aided in the impression of genuineness but also aided in co-creating the crisis with the people of Aotearoa New Zealand, further providing credence to the togetherness of the lockdown (McGuire et al., 2020). Instead of being in contrast to the initial authoritative stance taken in the run-up to the implementation of the lockdown, this closeness and perceived transparency forged trust and the feeling of a common ground among the Kiwi public.

Figure 4 shows examples of the messaging used by the Government during at least the early stages of the pandemic. The usage of the “team of five million” as an inclusionary metaphor worked on several levels. First, its appeal for the nation to work together to eliminate the virus via empathetic consensus was in contrast to other nations launching their battles on the virus—for example, Emmanuel Macron declared that France was “at war” against the virus (Erlanger, 2020). This was further highlighted with the official New Zealand Government page for information on the pandemic called “Unite against COVID-19”. Second, “it fed into an “us” vs. “them” dichotomy and into Aotearoa New Zealand’s underdog persona, if we take “us” as the nation and “them” as other nations, or perhaps even Kiwis overseas.” Third, New Zealand’s “compassionate liberalism” (James and Valluvan, 2020, p. 1240) as a signifier helped feed into the “team of five million” metaphor. The discursive formation “of the metaphor” also effectively isolated those opposed to the nationwide lockdown or to the Government’s wider virus response as them not being part of the team.

The overarching kindness signifier was underlined with several key phrases that have been the foundational axioms underpinning Aotearoa New Zealand’s coronavirus approach. With the announcement of restrictions on 14 March, the Prime Minister emphasized the need for the country to “go hard, and go early” with its pandemic response (Ardern, 2020b). The shared language as a “team of five million,” and the cooperation and behaving for the greater good that they infer, aided the nationalism previously discussed at least during the nationwide lockdown. The discursive dominance of those terms were key in defining Aotearoa New Zealand’s defense strategy.

The collective rhetoric worked in ensuring that Kiwis were mostly compliant with the lockdown measures, emphasized and enforced by a neighborhood form of control: the police website set up for people to report suspected lockdown breaches during Alert Level 4 initially crashed, with over 9,000 reports from people “dobbing in” individuals and businesses for suspected lockdown breaches in its first 3 days (Roy, 2020). The irony of this is that, as was previously detailed, the time period when these reports were made was within the High Court’s ruling that the order to stay at home was unlawful. There is also an element of individual performative control visible, as it is an indication that those in lockdown—with the lack of control over, for example, their personal movements and who they could have personal contact with—sought to exert control via active surveillance over others by reporting them to the authorities.

The distinctive employment of kindness that is a hallmark of the Prime Minister’s leadership rhetoric can be traced back to her speech at the United Nations General Assembly in September 2018, when she emphasized that the “one concept that we are pursuing in New Zealand it is simple and it is this: kindness” (Ardern 2018). This was consolidated and extended as a form of crisis communication after the tragedies of March and December 2019, providing a benchmark that the country was already familiar with. It has become one of the prevailing hegemonic discourses in Aotearoa New Zealand. As the dominant discourse, although it may be difficult to argue that kindness is political, it could always have its hegemonic status challenged by a new, antagonistic discourse within both Aotearoa New Zealand’s politics and society. Kindness as an objective reality can always become the political again. The kindness discourse was not only from the Government; in line with Aotearoa New Zealand’s bipartisan approach to crises, the then Leader of the Opposition, Simon Bridges, tweeted at the start of the lockdown of the importance of staying at home, using the “We’re all in this together” refrain (Bridges, 2020b).

The meaning-making evident in the Prime Minister’s crisis communication was consistent throughout the first year of the pandemic, and that helped to ensure buy-in from the public when the country was in its national lockdown. Humans are inherently driven to both create and continue meaningful self-narratives, and in Aotearoa New Zealand the key phrases that emerged have fed its self-narrative regarding COVID-19 (Mackay and Bluck, 2010). Going back to the argument that the “people” are not taken for granted in politics, but that that articulation of the people is a key to performative politics (Palonen, 2021), we can also point, through the theory of hegemony of Laclau and Mouffe, to both inclusive and exclusive processes, universal claims and claims of particularity, which go hand in hand in politics (Laclau, 1992). The inclusive political rhetoric that evoked the importance of kindness emerges as a key nodal point because its meaning-making was a central factor in Kiwis complying with lockdown regulations and forging a community consensus. As was seen with the descriptor of iwi checkpoints as community checkpoints, the rhetorical focus was on having Aotearoa New Zealand concentrate on its supposed homogeneity as a “team of five million”.

This article has positioned key aspects of Aotearoa New Zealand’s COVID-19 response in a rhetorical/discursive-performative analysis framework. The multiple facets to any country’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic means there are multiple nodal points that could have been extrapolated. The three nodal points chosen help to explain the generalized success of Aotearoa New Zealand’s COVID-19 response in comparison with other nations, and how they bound together as an inclusive, if temporary, articulation that is both performative and hegemonic. However, it has also disclosed internal exceptionalisms evident in the nation’s response. The material shows that throughout the pandemic, the framing of the nation’s response as reliant on kindness and working together as a team has not been able to completely avoid the hegemonic divisiveness of not only other nations but also those within the country who were either singled out for blame, such as the South Auckland family, or singled out for attempting to protect their communities, as with the iwi roadblocks.

First, an emphasis on the hegemonic “us” was performed throughout the pandemic in 2020. It began with the rearticulation of nationalism in Aotearoa New Zealand due to the virus being brought in from overseas, but it devolved into race-based attacks and particularly the scapegoating of some minorities in the community. The country’s natural borders and the closure of travel to all but citizens and permanent residents performed control as a blunt instrument, organically feeding the emphasis on hegemony that occurred. However, ironically this insular focus helped aid the electoral dismissal of the Deputy Prime Minister Winston Peters, who had previously campaigned on such a nationalist angle. Second, the performative control shown by some iwi in setting up roadblocks to prevent the spread of the virus in vulnerable communities also displayed underlying antagonisms regarding the social and cultural divides with Māori. It constituted a performative practice of statehood that was a regional version of what the nation had enacted, but highlighted the deep-seated cleavage that exists over the tino rangatiratanga—Māori sovereignty—that is held by Māori. Third, the consistent communication delivery methods of the Prime Minister, the rhetoric of kindness, and the “team of five million” metaphor were central in forging control by consensual compliance. Despite the early days of the nationwide lockdown later being challenged in court, the performativity of willing everyone to be part of the “team of five million” saw wide compliance for the strict measures.

The kindness rhetoric was used as a mobilizing device and as a performative aspect of statehood that reinforced the need for consensus in order for the nationwide lockdown measures to work as intended. Whether this will be the case if the virus is to emerge again in the community is unknown. As the chains of equivalence and thus the nodal points of the discourse on Aotearoa New Zealand’s pandemic response transform as the pandemic endures, a rhetorical/discursive-performative analysis framework could be operationalized further to develop nodal points that are emerging at the time of writing. Complications such as a lack of PPE for staff within MIQ, intermittent travel corridors with Australia and the Pacific Islands, and vaccine delivery are proving to be challenging for the country’s continued management of COVID-19.

The Laclaudian-Mouffean approach enables us to see the performative political articulation, where the hegemonic “us”, iwi regionalism, and the rhetoric of kindness are the three key nodal points that have been identified as significant in structuring the discourse on how Aotearoa New Zealand responded to COVID-19 via performative control. The country has both structural and socio-political advantages that have aided in its, so far relatively successful, management of the crisis, but there has also been the re-emergence of domestic cultural, geographical, and social frontiers that will become more evident if the virus is to return to the community.

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/diseases-and-conditions/covid-19-novel-coronavirus/covid-19-data-and-statistics/covid-19-case-demographics (COVID-19 case details through 31 January 2021).

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

During the course of authoring this article, I was funded by the Academy of Finland via the WhiKnow project (project number 320275).

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

I would like to thank Emilia Palonen and the Helsinki Hub on Emotions, Populism, and Polarisation (HEPPsinki) research team for their support and feedback.

Abdullah, W. J., and Kim, S. (2020). Singapore's Responses to the COVID-19 Outbreak: A Critical Assessment. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 50, 770–776. doi:10.1177/0275074020942454

Antonsich, M. (2020). Did the COVID-19 Pandemic Revive Nationalism? Available at: https://search-proquest-com.libproxy.helsinki.fi/magazines/did-covid-19-pandemic-revive-nationalism/docview/2455027361/se-2?accountid=11365 (Accessed January 20, 2021).

Ardern, J. (2018). Kindness and Kaitiakitanga: Jacinda Ardern Addresses the UN. Available at: https://thespinoff.co.nz/politics/28-09-2018/kindness-and-kaitiakitanga-jacinda-ardern-addresses-the-un/ (Accessed December 10, 2020).

Ardern, J. (2020a). Evening Everyone. Thought I’d Jump Online and Answer a Few Questions as We All Prepare to Stay home for the Next Wee while. Join Me if You’d like! Available at: https://www.facebook.com/45300632440/videos/147109069954329 (Accessed December 10, 2020).

Ardern, J. (2020b). Major Steps Taken to Protect New Zealanders from COVID-19. Available at: https://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/major-steps-taken-protect-new-zealanders-covid-19 (Accessed December 1, 2020).

Ardern, J. (2020c). Prime Minister’s Remarks halfway through Alert Level 4 Lockdown. Available at: https://www.beehive.govt.nz/speech/prime-minister%E2%80%99s-remarks-halfway-through-alert-level-4-lockdown (Accessed December 1, 2020).

Bardsley, D. (2014). “Slang in Godzone (Aotearoa New Zealand),” in Global English Slang. Editor J Coleman (London: Routledge), 96–106.

Bridges, S. (@simonjbridges) (2020a). This Is Disgraceful. Proves the Government's Response Is to Dismiss. Available at: https://twitter.com/simonjbridges/status/1262875081585246209 (Accessed January 20, 2021).

Bridges, S. (@simonjbridges) (2020b). Like All the Other Challenges We’ve Faced as a Nation, We Will Get Through This One. Stay Safe, Stay Connected and Stay Home. We’re All in This Together. Available at: https://twitter.com/simonjbridges/status/1242693122066268160 (Accessed January 28, 2021).

Brunton, T. (2020). Tourism Minister under Fire for Not Acting Fast Enough. Available at: https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/political/416464/tourism-minister-under-fire-for-not-acting-fast-enough (Accessed December 10, 2020).

Burrows, M. (2020). 'That's a Disgrace': MPs, Police Commissioner in Fiery Clash over Community Roadblocks. Available at: https://www.msn.com/en-nz/news/national/thats-a-disgrace-mps-police-commissioner-in-fiery-clash-over-community-roadblocks/ar-BB13oPG3 (Accessed December 10, 2020).

Butler, J. (1988). Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory. Theatre J. 40 (4), 519–531. doi:10.2307/3207893

Coughlan, T. (2020). Kelvin Davis Cancels on Epidemic Response Committee After Treasury No-show. Available at: https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/politics/300016164/kelvin-davis-cancels-on-epidemic-response-committee-after-treasury-noshow (Accessed November 10, 2020).

Deguara, B. (2020). Coronavirus: Auckland Moves to Level 3, Rest of NZ to Level 2, as Four Covid-19 Cases Confirmed in Community. Available at: https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/health/coronavirus/122416730/coronavirus-auckland-moves-to-level-3-rest-of-nz-to-level-2-as-four-covid19-cases-confirmed-in-community (Accessed January 28, 2021).

Devlin, C. (2020). Coronavirus: Prime Minister Defends Letter Ordering Ministers and Officials Not to Appear before Covid Select Committee. Available at: https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/politics/121570573/coronavirus-prime-minister-defends-letter-ordering-ministers-and-officials-not-to-appear-before-covid-select-committee (Accessed 01 13, 2021).

Donovan, T. (2020). Misclassifying Parties as Radical Right/Right wing Populist: a Comparative Analysis of New Zealand First. Polit. Sci. 72 (1), 58–76. doi:10.1080/00323187.2020.1855992

Dutta, M. J., Elers, C., and Jayan, P. (2020). Culture-Centered Processes of Community Organizing in COVID-19 Response: Notes from Kerala and Aotearoa New Zealand. Front. Commun. 5 (62), 1–15. doi:10.3389/fcomm.2020.00062

Erlanger, S. (2020). Macron Declares France ‘at War’ with Virus, as E.U. Proposes 30-Day Travel Ban. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/16/world/europe/coronavirus-france-macron-travel-ban.html (Accessed December 10, 2020).

Farrier, D. (2020). Webworm Talks to the Man Who Started the COVID-19 Outbreak Rumour in New Zealand. Available at: https://www.webworm.co/p/webworm-talks-to-the-man-who-started (Accessed January 10, 2021).

Fouda, A., Mahmoudi, N., Moy, N., and Paolucci, F. (2020). The COVID-19 Pandemic in Greece, Iceland, New Zealand, and Singapore: Health Policies and Lessons Learned. Health Pol. Tech. 9 (4), 510–524. doi:10.1016/j.hlpt.2020.08.015

Golder, S. N., Crabtree, C., and Dhima, K. (2019). Legislative Representation and Gender (Bias). Polit. Sci. 71 (1), 1–16. doi:10.1080/00323187.2019.1632151

Graham, R., and Masters‐Awatere, B. (2020). Experiences of Māori of Aotearoa New Zealand's Public Health System: a Systematic Review of Two Decades of Published Qualitative Research. Aust. New Zealand J. Public Health 44, 193–200. doi:10.1111/1753-6405.12971

Harris, M., and Williams, D. V. (2020). Community Checkpoints Are an Important and Lawful Part of NZ’s Covid Response. Available at: https://thespinoff.co.nz/society/10-05-2020/community-checkpoints-an-important-and-lawful-part-of-nzs-covid-response/(Accessed November 05, 2020).

Hey, V. (2006). The Politics of Performative Resignification: Translating Judith Butler's Theoretical Discourse and its Potential for a Sociology of Education. Br. J. Sociol. Edu. 27 (4), 439–457. doi:10.1080/01425690600802956

Holmes, J., Marra, M., and Lazzaro-Salazar, M. (2017). Negotiating the Tall Poppy Syndrome in New Zealand Workplaces: Women Leaders Managing the challenge. Gend. Lang. 11 (1), 1–29. doi:10.1558/genl.31236

Horvath, G. (2018). “The Semiotics of Flags: The New Zealand Flag Debate Deconstructed,” in Language and Literature in a Glocal World. Editor S Mehta (Singapore: Springer), 115–126. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-8468-3_7

Howarth, D. (2018). Marx, Discourse Theory and Political Analysis: Negotiating an Ambiguous Legacy. Crit. Discourse Stud. 15 (4), 377–389.

Human Rights Commission (2020). Racism Is No Joke Campaign Launched to Fight Racism against Asian New Zealanders. Available at: https://www.hrc.co.nz/news/racism-no-joke-campaign-launched-fight-racism-against-asian-new-zealanders/ (Accessed December 10, 2020).

Hurihanganui, T. A. (2020). Covid-19: Te Whānau Ā Apanui Closes Tribal Boundaries. Available at: https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/covid-19/412295/covid-19-te-whanau-a-apanui-closes-tribal-boundaries (Accessed November 29, 2020).

Jackson, P. (2020). More Resistance to Iwi Checkpoints. Available at: https://www.nzherald.co.nz/northland-age/news/more-resistance-to-iwi-checkpoints/KJEEJQMS6VDOA2Y76F4RLKPPVU/ (Accessed November 29, 2020).

James, M., and Valluvan, S. (2020). Coronavirus Conjuncture: Nationalism and Pandemic States. Sociology 54 (6), 1238–1250. doi:10.1177/0038038520969114

Johnson, C., and Williams, B. (2020). Gender and Political Leadership in a Time of COVID. Pol. Gen. 16 (4), 943–950. doi:10.1017/s1743923x2000029x

Jørgenson, M., and Phillips, L. J. (2002). Discourse Analysis as Theory and Method. London: Sage. doi:10.4135/9781849208871

Knight, D. (2020). Lockdown Bubbles through Layers of Law, Discretion and Nudges – New Zealand. Available at: https://verfassungsblog.de/covid-19-in-new-zealand-lockdown-bubbles-through-layers-of-law-discretion-and-nudges/ (Accessed December 7, 2020).

Laclau, E., and Mouffe, C. (1985). Hegemony and Socialist Strategy: Towards a Radical Democratic Politics. London: Verso.

Laclau, E. (1992). Universalism, Particularism, and the Question of Identity. JSTOR 61, 83–90. doi:10.2307/778788

Mackay, M. M., and Bluck, S. (2010). Meaning-making in Memories: a Comparison of Memories of Death-Related and Low point Life Experiences. Death Stud. 34, 715–737. doi:10.1080/07481181003761708

MacLennan, C. (2020). ‘Flippant’ Bush Doing Himself No Favours. Available at: https://www.newsroom.co.nz/2020/04/02/1111992/flippant-bush-doing-himself-no-favours (Accessed December 15, 2020).

Manch, T. (2020). Coronvirus: Beehive Scrambled to Contain Email Telling Ministers to 'dismiss' Questions about Covid-19 Response. Available at: https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/health/coronavirus/121465406/coronvirus-beehive-scrambled-to-contain-email-telling-ministers-to-dismiss-questions-about-covid19-response (Accessed November 7, 2020).

Martin, H. (2020). Coronavirus: Kiwi Family in Isolation in Auckland 'battered' Online. Available at: https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/health/120023506/coronavirus-kiwi-family-in-isolation-in-auckland-battered-online (Accessed December 5, 2020).

McGuire, D., Cunningham, J. E. A., Reynolds, K., and Matthews-Smith, G. (2020). Beating the Virus: an Examination of the Crisis Communication Approach Taken by New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern during the Covid-19 Pandemic. Hum. Resource Dev. Int. 23 (4), 361–379. doi:10.1080/13678868.2020.1779543

McMeeking, S., and Savage, C. (2020). Maori Responses to Covid-19. Pol. Q. 16 (3). doi:10.26686/pq.v16i3.6553

Ministry of Business, Innovation, and Employment (2020). Briefing for Incoming Minister COVID-19 Response: Managed Isolation and Quarantine (MIQ). Available at: https://www.beehive.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2020-12/MIQ.pdf (Accessed March 9, 2021).

Ministry of Health (2020a). 4 Cases of COVID-19 with Unknown Source. Available at: https://www.health.govt.nz/news-media/media-releases/4-cases-covid-19-unknown-source (Accessed November 28, 2020).

Ministry of Health (2020b). Single Case of COVID-19 Confirmed in New Zealand. Available at: https://www.health.govt.nz/news-media/media-releases/single-case-covid-19-confirmed-new-zealand (Accessed November 28, 2020).

Ministry of Health (2021a). COVID-19: Case Demographics. Available at: https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/diseases-and-conditions/covid-19-novel-coronavirus/covid-19-data-and-statistics/covid-19-case-demographics (Accessed March 19, 2021).

Ministry of Health (2021b). COVID-19: Source of Cases. Available at https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/diseases-and-conditions/covid-19-novel-coronavirus/covid-19-data-and-statistics/covid-19-source-cases (Accessed January 29, 2021).

New Zealand Government (2020). History of the COVID-19 Alert System. Available at: https://covid19.govt.nz/alert-system/history-of-the-covid-19-alert-system/ (Accessed December 7, 2020).

New Zealand Government (2021). History of the COVID-19 Alert System. Available at: https://covid19.govt.nz/alert-levels-and-updates/history-of-the-covid-19-alert-system/. (Accessed March 19, 2021).

New Zealand Herald (2020). Winston Peters Claims Covid-19 Cluster Linked to Quarantine Breach. Available at: https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/winston-peters-claims-covid-19-cluster-linked-to-quarantine-breach/QCTYU55FJ6X3OJKKAUOEVE6RUM/ (Accessed December 5, 2020).

Palonen, E. (2021). Democracy vs. Demography: Rethinking Politics and the People as Debate. Thesis Eleven 164, 88–103. doi:10.1177/0725513620983686

Palonen, E. (2018). “Rhetorical-Performative Analysis of the Urban Symbolic Landscape: Populism in Action,” in Discourse, Culture and Organization: Inquiries into Relational Structures of Power. Editor T Marttila (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan US), 179–198. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-94123-3_8

Parker, D. (2020). Attorney-General Responds to Court Judgment on Legality of Health Orders. Available at: https://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/attorney-general-responds-court-judgment-legality-health-orders-0 (Accessed December 4, 2020).

Peacock, C. (2020). Radio ‘roadblock’ Interview sparks Racism Complaints. Available at: https://www.rnz.co.nz/national/programmes/mediawatch/audio/2018745746/radio-roadblock-interview-sparks-racism-complaints (Accessed December 05, 2020).

Phelan, S., and Shearer, F. (2009). The “Radical”, the “Activist” and the Hegemonic Newspaper Articulation of the Aotearoa New Zealand Foreshore and Seabed Conflict. Journalism Stud. 10 (2), 220–237. doi:10.1080/14616700802374183

Radio New Zealand (2020a). Coronavirus: Council, Police and Iwi Form 'partnership' after Plan to Close Tribal Borders. Available at: https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/te-manu-korihi/412398/coronavirus-council-police-and-iwi-form-partnership-after-plan-to-close-tribal-borders (Accessed November 29, 2020).

Radio New Zealand (2020b). Coronavirus: Covid-19 Developments in NZ and Around the World on 19 March. Available at: https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/national/412094/coronavirus-covid-19-developments-in-nz-and-around-the-world-on-19-march (Accessed March 9, 2021).

Robert, A. (2020). Lessons from New Zealand's COVID-19 Outbreak Response. The Lancet 5 (11), 569–570. doi:10.1016/s2468-2667(20)30237-1

Roberto, K. J., Johnson, A. F., and Rauhaus, B. M. (2020). Stigmatization and Prejudice during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Administrative Theor. Praxis 42 (3), 364–378. doi:10.1080/10841806.2020.1782128

Roy, E. (2020). New Zealand Site to Report Covid-19 Rule-Breakers Crashes amid Spike in Lockdown Anger. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/30/new-zealand-site-to-report-covid-19-rule-breakers-crashes-amid-spike-in-lockdown-anger (Accessed January 28, 2020).

Salter, L. (2016). Populism as a Fantasmatic Rupture in the post-political Order: Integrating Laclau with Glynos and Stavrakakis. Kōtuitui: New Zealand J. Soc. Sci. Online 11 (2), 116–132. doi:10.1080/1177083X.2015.1132749

Satherley, N., Greaves, L. M., Osborne, D., and Sibley, C. G. (2020). State of the Nation: Trends in New Zealand Voters' Polarisation from 2009-2018. Polit. Sci. 72 (1), 1–23. doi:10.1080/00323187.2020.1818587

Science Media Centre (2020). State of National Emergency Declared - Expert Reaction. Available at: https://www.sciencemediacentre.co.nz/2020/03/25/state-of-national-emergency-declared-expert-reaction/. (Accessed December 15, 2020).

Statistics New Zealand (2020). Ethnic Group Summaries Reveal New Zealand's Multicultural Make-Up. Available at: https://www.stats.govt.nz/news/ethnic-group-summaries-reveal-new-zealands-multicultural-make-up (Accessed December 9, 2020).

Steyn, N., Binny, R. N., Hannah, K., Hendy, S. C., James, A., Kukutai, T., et al. (2020). Estimated Inequities in COVID-19 Infection Fatality Rates by Ethnicity for Aotearoa New Zealand. N. Z. Med. J. 133 (1521), 28–39.

Stuart, I. (2003). The Construction of a National Maori Identity by Maori Media. Pac. Journalism Rev. 9 (1), 45–58. doi:10.24135/pjr.v9i1.756

Stuff (2020). Coronavirus: Third Confirmed Case of Coronavirus Appears to Have Spread within Family. Available at: https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/health/120025480/coronavirus-third-confirmed-case-for-new-zealand (Accessed January 10, 2021).

Summers, J., Cheng, H.-Y., Lin, H.-H., Barnard, L. T., Kvalsvig, A., Wilson, N., et al. (2020). Potential Lessons from the Taiwan and New Zealand Health Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Lancet Reg. Health - West. Pac. 4, 100044. doi:10.1016/j.lanwpc.2020.100044

Thaker, J., and Menon, V. (2020). Aotearoa-New Zealand Public Responses to COVID-19. Wellington: Massey University.

Tregidga, H., Milne, M., and Kearins, K. (2014). (Re)presenting ‘sustainable Organizations'. Account. Organizations Soc. 39 (6), 477–494. doi:10.1016/j.aos.2013.10.006

Wilson, S. (2020). Pandemic Leadership: Lessons from New Zealand's Approach to COVID-19. Leadership 16 (3), 279–293. doi:10.1177/1742715020929151

Young, A. (2020). Covid 19 Coronavirus: Jacinda Ardern Talks to Mike Hosking About David Clark and Ashley Bloomfield. Available at: https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/covid-19-coronavirus-jacinda-ardern-talks-to-mike-hosking-about-david-clark-and-ashley-bloomfield/227XYHOGQESHL7SNEQLFYTECKQ/ (Accessed December 5, 2020).

Keywords: COVID-19, Aotearoa New Zealand, performative control, rhetoric, discourse theory of laclau and mouffe

Citation: Gilray C (2021) Performative Control and Rhetoric in Aotearoa New Zealand’s Response to COVID-19. Front. Polit. Sci. 3:662245. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.662245

Received: 31 January 2021; Accepted: 05 July 2021;

Published: 12 August 2021.

Edited by:

Dolors Palau, University of Valencia, SpainReviewed by:

Catherine Jones, University of St Andrews, United KingdomCopyright © 2021 Gilray. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Claire Gilray, Y2xhaXJlLmdpbHJheUBoZWxzaW5raS5maQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.