- 1Department of History & Politics, University of New Brunswick, Saint John, NB, Canada

- 2Q-Step Centre, Department of Politics, University of Exeter, Exeter, United Kingdom

Our study concerns the factors leading to the electoral success and failure of LGBTQ candidates in the context of the changing nature of prejudices. We hypothesize that more positive views toward “respectability candidates,” as captured by familial status, has replaced explicit prejudice toward out LGBTQ candidates in societies where acceptance of sexual minorities in general has grown. In a survey experiment conducted with a sample of Canadian voters, one of the first countries to legalize marriage equality, we find suggestions that voters are more likely to reward lesbian and gay candidates who adopt heteronormative relationships (married with children vs. single) than those who do not. These patterns become more evident when we explore causal heterogeneity with controls for individual-level characteristics and attitudes that typically predict support toward lesbian and gay candidates. Here we find these predictors rewarded single lesbian and gay candidates, whereas lesbian and gay candidates with families were simply more supported across the board.

Introduction

Recent elections around the world have seen a growing number of openly LGBTQ people elected to political office. Attempts to record this increase suggest that between 1976 and the end of 2020 there have been 78 LGBTQ individuals elected to national upper houses and 359 elected to lower houses.1 This is up from 18 upper house members and 95 lower house members identified as of November 2013 (Reynolds, 2013). These numbers are noteworthy given the fact that it has only been in the past few decades that politicians have felt comfortable enough to run as openly out candidates.

Rates of success differ from one country to another and from one form of electoral system to another. Countries using first past the post systems like the United Kingdom witnessed LGBTQ Members of Parliament holding 8% (52 out of 650) of the seats in the House of Commons after the 2019 election. The 2020 United States election resulted in nine LGBTQ members of Congress, an increase of two from 2018 (Moreau, 2020).2 In its 2019 federal election, Canada elected six out Members of Parliament (1.8%). New Zealand, which uses a mixed member proportional system had 12 LGBTQ MPs (representing 10% of the House) elected in their 2020 election (RNZ News, 2020) while in 2017, 11 gay and four lesbian politicians (2.1%) held seats in the German Bundestag. In Finland, which employs a proportional representation system only two gay men and no out lesbians (1%) were elected in the 200 seat legislature in 2019 (Juvonen, 2020). The number of transgender candidates who have been elected is even smaller (Casey and Reynolds, 2017).

While overall, these numbers remain small, and they often reflect different cultural and institutional contexts that may make it easier or more challenging for candidates to win elections, there is nonetheless clear evidence that voters are increasingly willing to vote for openly LGBTQ candidates, particularly in Western democracies. However, this support is not universal and varies across different segments of the population and different types of politicians. For example, in a recent comparative study of the United States, United Kingdom and New Zealand, Magani and Reynolds (2020) found that lesbian and gay candidates both receive greater support than that given to transgender candidates. They also found that white candidates fare better than minority candidates, and that those with past political experience where supported to higher degrees than those who were less experienced (see also Haider-Markel et al., 2017).

Less well understood, and what our work explores, is whether the growing support for LGBTQ candidates reflects overall social change and broadening acceptance of sexual minorities or whether this support is awarded to those individuals who, other than through their sexual orientations conform to socially accepted lifestyles and political norms. In other words, is this support universal, or does it obscure new forms of prejudices that individuals have become more likely to admit. Is it a reflection of respectability politics, which rewards members of the LGBTQ community whose behaviors mirror heterosexual norms and penalizes those whose behaviors are non-conforming in terms of lifestyle and family background?

In this article, we investigate whether citizens adjust their vote intention as a function of three experimentally manipulated characteristics: candidate gender, candidate sexual orientation, and candidate familial status.3. A candidate’s gender is implied by using male or female pronouns and first names in news stories about their candidacies. Similarly, their sexual orientation is implied by referencing a male or female partner in these stories while familial status is implied by referring to the partner as either a spouse with whom they share children or an ex-boyfriend or girlfriend.4. Using a survey experiment conducted in September 2018 of a nationally representative sample of Canadian respondents, we first present evidence that implied sexual orientation alone does not correspond to systematic changes in terms of vote intention, nor does it when considered along with candidate gender. Differences do appear though in combination with familial status. Lesbian or gay candidates who are married with children received a boost in vote intention that is comparable to straight single candidates who are childless. Single childless lesbian and gay candidates do not. Next, we proceed to explore causal heterogeneity by age, gender, education, sexual orientation, and religiosity, attitudes to sexual minorities, gender-role traditionalism and ideology. We find greater heterogeneity when it comes to responses to single childless lesbian or gay candidates, and less heterogeneity when it comes to those who are married with children who were supported more across the board. We conclude by drawing implications to the respectability and symbolic representation literature.

Theory

Sexual Minorities, Familial Status, and the Vote Choice

As the majority of out LGBTQ candidates have only run for elected office in recent decades, the academic literature examining voters’ willingness to vote for them is more limited than that for other identities such as gender or race/ethnic status (Visalvanich, 2017; Schwarz et al., 2020). What research is available suggests that despite significant change in levels of acceptance of lesbians and gays in North American society5 electoral support for LGBTQ candidates is still relatively low. In the United States for example, a 1978 Gallup survey indicated that only 26 percent of American respondents agreed that they would vote for a well-qualified presidential candidate who was lesbian or gay. By 2015, this same question resulted in 74 percent of the electorate saying they would do so (Saad, 2015). This still left 25 percent who would not.

However, there are vestiges of opposition among segments of the electorate in many countries. In a 2017 study, Haider-Markel and his colleagues (2017) found that strong opposition remains among some American voters toward lesbian or gay congressional candidates, and that this opposition appeared across all levels of office (Haider-Markel and Bright, 2014, 256). More recent work by Magani and Reynolds (2020) based on a conjoint experiment demonstrates that voters in the Unites States, United Kingdom and New Zealand continue to punish candidates who are LGBTQ. Penalties are the highest in the United States and lowest in New Zealand and are even more significant for transgender candidates than they are for lesbians and gays (p. 1). They find that the degree to which voters punish LGBTQ candidates is affected by a candidate’s sex with voters more likely to penalize gay men than lesbians. Intersectionality also plays a role in that American LGBTQ candidates who are also black face a greater penalty when compared to whites although other racialized and ethnic minorities faced no additional prejudice. Finally, there was less of a bias toward candidates who had previous elected experience; a finding that appeared at all levels of public office. The Magani and Reynolds article is interesting in that it adds to the lack of consensus as to whether voters are more biased toward lesbian candidates than gay male candidates. While some earlier work has argued that this is indeed the fact (Golebiowska and Thomsen, 1999; Bailey and Nawara, 2017) other researchers have found the sex of a LGBTQ candidate had little impact on voters’ willingness to support them (Haider-Markel, 2010, p. 40–41).

One aspect of a LGBTQ candidate’s profile that past studies have not explored is their familial status. In part, this may be because countries such as the United States, where much of this research has been conducted, have only recently legalized same sex marriage and permitted LGBTQ individuals to legally adopt children. For example, marriage equality was only legalized in the United States in 2015 and it was in 2017 that adoption by same-sex couples became legal across all states. While in the United Kingdom, adoption has been possible since 2002, equal marriage was only legislated in 2013 and came into force in 2014. However, as more LGBTQ individuals are marrying and having or adopting children before they run for office, this is an aspect of their profile that deserves more attention.

The lack of attention to familial status of LGBTQ candidates is particularly notable as recent studies have found that across “surveys of voters and public officials, respondents consistently prefer both male and female candidates who are married with children compared to those who are not” (Teele et al., 2017, p. 526). Telle and her colleagues have demonstrated the impact that familial status can have on candidates finding that married men with children are likely to receive 6.5 percentage points more support than single men, while married women with children are likely to receive 3.3 percentage points more support than single women. Similar results are found in other parts of the world (Clayton et al., 2017; Schwindt-Bayer, 2010).

This raises the question of what impact a candidates’ familial status has on voters’ assessments of LGBTQ politicians. As more and more LGBTQ politicians take advantage of new opportunities to marry and have or adopt children, this question becomes more pressing when considering voters’ willingness to support this under-represented segment of society. Furthermore, single LGBTQ politicians vs. those with families may present conflicting degrees of support or opposition among different segments of the population depending upon voters’ feelings about sexual minorities, the question of marriage equality or adoption and how this might disrupt or reinforce heteronormative institutions such as marriage that underpin western societies.

For example, because of the vociferous debates around same sex marriage or the rights of LGBTQ individuals to adopt children in many countries, particularly among more conservative religious groups, the fact that a gay individual is married with children might signal that they are challenging social norms. The support for lesbians and gays has increased dramatically over recent decades, however, there are still large portions of the population who are uncomfortable with public displays of affection between LGBTQ people which are legitimized by the institution of marriage. Thus, LGBTQ candidates who are openly gay and married may draw public reprobation for creating a situation of discomfort among those segments of the public who are less supportive of lesbians and gays in the first place. In particular, religious and social conservatives may worry that lesbians and gays who are married with children will undermine the role that marriage plays in reinforcing patriarchal and heteronormative relations reflected in the idea of a “nuclear family” based on an enduring, monogamous relationship designed to support the raising of children.

Alternatively, the literature on respectability politics suggests that by participating in the heteronormative institution of marriage a lesbian or gay candidate may send the message to the public that they are no different from heterosexual couples (Valverde, 2006) and are therefore not as disruptive for social norms. Candidates who are married with children conform to a form of “respectability politics” that require LGBTQ individuals to fit into existing dominant frameworks, while those who are not, or whose lifestyles run counter to dominant social norms can be viewed as “unrespectable.” Those who are single may evoke stereotypes of the promiscuous and sexually available homosexual who may challenge moral standings and politicize gay culture (Duggan, 2003). In doing so they may threaten dominant heteronormative assumptions and institutions and evoke sentiments of fear, disgust or threat. On the other hand, lesbians and gay men who marry and enter into long-term monogamous relationships established around nuclear families that included children present less of a threat. They are “good gay citizens” whose lives could mirror those of their heterosexual colleagues in all ways except for the fact that their spouses share the same genitalia. As Bernstein and Taylor (2013) have argued same-sex marriage distinguishes between “good gays,” (i.e., those who fit within traditional heteronormative frameworks) and “bad gays” (i.e., those who prefer alternative systems) (13). This might be reinforced by media representations that continue to position LGBTQ candidates along a “good, respectable lesbian/gay” vs. “bad, not–respectable lesbian/gay” continuum (Lalancette and Tremblay, 2019).

It should be noted however, that there have long been tensions within the LGBTQ community about the focus on marriage rights and other rights and equality based issues. Many have felt that by emphasizing lifestyles that mirror patriarchal heterosexual norms, rights campaign for equal marriage or adoption continues to problematize LGBTQ individuals whose lives do not conform. Rather than broadening acceptance of LGBTQ individuals in all their diversity, many view same-sex marriage as “an institution of normalization in which the married are rendered “normal,” healthy and moral, and the unmarried “abnormal, unhealthy and deviant” (Green, 2013, 379). Such a focus may lead to increased support for only those meet certain standards of respectability, leaving those who do not, facing suspicion and disapproval.

These considerations lead us to formulate our central hypothesis linking responses to sexual minority candidates with their familial status:

H1: Citizens’ support for lesbian and gay candidates is conditional on “respectability politics” as captured by familial status, with greater support being awarded to candidates with nuclear families who may be seen to conform more to heteronormative ideals of appropriate lifestyle.

Heterogeneous Responses to LGBTQ Candidates

Much of the work on voter bias toward LGBTQ politicians finds that voters’ responses are conditioned by their own social demographic and belief structures (Haider-Markel and Bright, 2014, 257; Bailey and Nawara, 2017; Magni and Reynolds forthcoming). Those segments of the electorate who are least likely to support LGBTQ candidates tend to be older, straight, male and those with lower levels of education. Several studies have shown that age is highly correlated with attitudes toward sexual minorities; support for them is consistently higher among younger individuals than it is among older generations and levels of support appear to increase with each generation (Herek, 2002; Brewer, 2003a, Brewer, 2003b; Egan and Sherrill, 2005; Haider-Markel and Joslyn, 2008). Women are generally more accepting of sexual minorities than men (Herek, 2002; Hinrichs and Rosenberg, 2002; Hicks and Lee, 2006; Smith, 2011), more likely than men to support LGBTQ politicians (Golebiowska, 2001; Haider-Markel and Joslyn, 2008; Doan and Haider-Markel, 2010; Heider-Markel et al., 2017; Everitt and Raney, 2019), and to stereotype them positively. Explanations for these findings rely on studies which show that straight men are more likely to embrace negative stereotypical beliefs about gays (Herek, 2002) and feel threatened by other men who violate heterosexual norms (Kite and Whitley, 1996). Lesbians pose less of a threat.

Similarly, greater support for LGBTQ politicians is found among individuals with higher levels of education as education is often correlated with more open-minded views about sexuality and social norms (Smith, 2011). Candidate—voter affinity may also result in greater support for lesbian or gay candidate by respondents who are themselves sexual minorities. There is significant evidence that affinity voting occurs among women (Goodyear-Grant, 2010; Goodyear-Grant and Crosskil, 2011; Goodyear-Grant and Tolley, 2017), ethno-cultural groups (Bird, 2009; Bird, 2011; Bird et al., 2011; Besco, 2015; Bird et al., 2016; Besco, 2019), and Indigenous populations (Dabin et al., 2019) and it makes sense that it occurs among the LGBTQ population.

Among the attitudinal factors that tend to condition support for LGBTQ politicians are religious beliefs, attitudes toward traditional gender roles and social norms, ideological positioning and general sympathy toward sexual minorities. Those who hold strong religious beliefs typically show the lowest levels of support for lesbians and gays and sexual minority candidates (Haider-Markel and Joslyn, 2008). In a similar vein, individuals who hold more traditional views of women’s roles in society are also less likely to support the candidates when informed that they are lesbian or gay (Hicks and Lee, 2006). Those who believe that women are better suited to the home than to the public sphere are also likely to be accepting of social changes that have accompanied the expansion of the rights of social minorities including the right to be married, or run for political office. Likewise, ideological positioning helps to predict voter opinion on social and political issues and has been found to be correlated with willingness to vote for politicians who are sexual minorities. American research indicates that those who are more conservative, falling on the right of the political spectrum are more likely than those who identify as liberals or position themselves on the left to be prejudiced toward lesbian or gay candidates (Bailey and Nawara, 2017; Haider-Markel and Bright date, 257; Haider-Markel and Joslyn, 2008; Herek, 2002; Magni and Reynolds forthcoming).

In addition, liking or disliking a particular group is also likely to affect willingness to support members of that group who are seeking elected office. Those voters who feel more positive toward LGBTQ individuals are more likely to support them as political candidates while those who hold more negative views are less likely to do so.

Partisanship can also play an important role in structuring support for LGBTQ politicians particularly in the United States, partisanship. However, the impact of these variables differs from one electoral context to another. For example, Magni and Reynolds (forthcoming) found that partisanship played far less of a role in the United Kingdom and in New Zealand than it did in the United States.

Based on the extant literature on heterogeneity and support for LGBTQ politicians overall, we expect that a range of demographic and attitudinal characteristics will condition the joint effect of sexual orientation and familial status as well.

H2: We expect that even when interacted with familial status there will be lower levels of support for sexual minority candidates among men, rather than women; older, rather than younger voters; as well as voters who are less religious or hold less traditional attitudes to gender roles, and finally, those on the right on the political ideology spectrum.

H2a: We expect that although individuals who are strongly religious or hold socially conservative views may be less support of lesbians and gay politicians, because of respectability politics they will be most critical of those who are single and less critical of those who are in established nuclear families.

H3: We also expect affinity voting based on sexual orientation thus sexual minority respondents would support sexual minority candidates more than straight candidates.

H3a: However, due to divisions within the LGBTQ community we do not expect this relationship to be conditional on candidate familial status.

The Canadian Context

Given recent contentious and partisan debates surrounding same sex marriage and adoption by LGBTQ individuals in a country such as the United States, we would argue that it is not a good case for examining the relationship between lesbian and gay candidate support and familial status. The impact of a candidate being part of a traditional family structure is likely to get lost in calcified partisan or religious positions around the legitimacy of policies such as equal marriage or adoption, rather than present information that might inform voters about their life styles and choices. Instead, it would be better to examine mediating effect of this demographic variable in a country such as Canada which legalized same sex union, first in the province of Ontario in 2003 and then in the rest of the country in 2005. Recent public opinion polls show that while there were divided responses to this legislation at the time it was enacted, there is now high levels of support and acceptance. In 2017 a CROP poll found 74% of Canadians agreed with the statement that it was “great that in Canada, two people of the same sex can get married” while only 26% disagreed. Thus, prejudice toward lesbian or gay politicians is less likely to be tied to voter opposition toward same sex marriage and more to assessments of candidates’ appropriateness as politicians.

Canada also has a strong level of public support for LGBTQ politicians. This can be seen in a 2012 Environics Americas Barometer survey where they were asked to use a scale of 1–10 (where one is strong disapproval and 10 is strong approval) to rate their approval or disapproval for the idea that homosexuals should be “permitted to run for public office.” In this study 67% of Canadian respondents indicated strong approval (scores of 8–10), 27% demonstrated neutral opinions (scores of 4–7) and only 6% showed strong disapproval with scores of 1–3 (Environics, 2012). A similar study among Americans revealed disapproval rates of 32% (Everitt and Tremblay, 2020).

The actual number of LGBTQ politicians sitting in the Canadian House of Commons is not large (as of February 2021 there are six representing 2% of the MPs and an additional 26 individuals holding office at the provincial level). However, the country has experience with high profile lesbian and gay politicians sitting in federal and provincial cabinets since the early 2000 s and holding the position of provincial premier since 2013 (Everitt and Lewis, 2020). Furthermore, a recent study has found that more than two thirds of the Canadian LGBTQ politicians holding federal or provincial office between 2017 and 2020 were either married or in a long-term common-law relationship (Tremblay, 2019).

This makes the idea of a married LGBTQ politician less shocking in Canada than elsewhere. Furthermore, lesbian and gay candidates have run for all parties in recent elections and national parties, including the Conservative Party of Canada have queer caucuses (Everitt, 2015). This means that the situation as presented in the experimental study is actually very realistic and unlikely to raise questions in respondents’ minds.

Finally, the fact that partisanship plays a weaker role in structuring attitudes toward lesbian and gay candidate choices in Canada than it does elsewhere provides some assurance that the impact off familial status is not being driven by party positions on lesbians and gays, but rather on underlying voter predispositions.

Methodology

Data

We recruited participants for an online survey studying “the impact of news coverage on voters’ assessments of politicians” via a Quest Mindshare panel of Canadians.6 We introduced quotas so that the final sample is representative of the Canadian population’s on age (over 18 years old), gender, and location. All surveys were completed between 25 September and September 27, 2018. Of the 1,014 surveys submitted, we have missing data on the dependent variable in this study, vote intention, thus we are only able to analyze 888 complete responses. We show the distribution of respondent demographics in the full as well as subsamples in Supplementary MaterialsIntroduction Sample characteristics. Responses were missing at random across treatment groups, a distribution we show in Supplementary MaterialsTheory Treatment details.

Treatments

We designed this as a repeated measures within-subject study, taking a first or baseline measure of vote intention following limited information—a preliminary news story—, and then a second measure following additional information in a second news story treatment manipulating our key variables of interest.7 As we were specifically interested in how a candidate’s identity (sex, sexual orientation or familial status) affected voters’ assessments of them, we deliberately limited information such as partisanship or policy positions that might confound these evaluations. While this may limit the external validity of our study, by emphasizing these social demographic identities it does allow us to isolate their impact in a way that non-experimental studies do not.

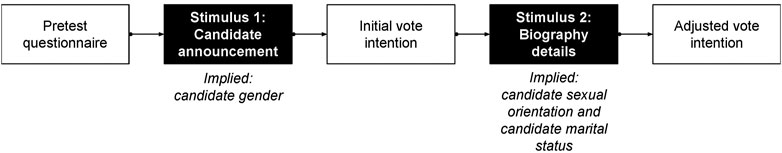

We show an overview of our process in Figure 1. First, participants were given a 350 word article announcing the intentions of a local individual to run for the nomination of a political party (not specified). In this stimulus, we manipulated candidate gender: half of the respondents received an article about a male candidate named David Kenney, while the second half about a female candidate named Donna Kenney. Other than the first name of the candidate and the pronouns of “he” and “she”, respectively, the two articles were identical. The chosen names are not notably racialized and the candidates were running in a city that has relatively low levels of immigrants or racialized minorities thereby reducing the chance that responses might be affected by racial biases.

With this procedure, we followed the standard practice of setting up factorial experiments and keeping the number of manipulated characteristics to the minimum. We chose to imply gender with first names, which also means that we do not investigate responses to explicitly transgender or nonbinary candidates. While we are concerned about the electoral performance of LGBTQ candidates broadly, we chose to focus on cisgender male and female candidates so that we could obtain a factorial design cross-tabulated with implied sexual orientation, as described below, with partners’ first names. The advantage of our approach is that we did not need to label candidates’ sexual orientation but left it to the survey respondents to infer sexual orientation, which would have been more difficult with transgender or nonbinary candidates without giving additional information. A more inclusive range of options on gender should be presented in future work, for example in a conjoint experimental design rather than vignettes.

Second, following a set of questions (see Measures), participants received a second news story, which included further information about the candidates in the form of a biography. In this stimulus, we manipulated two characteristics: candidate sexual orientation, and candidate familial status. These texts contained a reference to a partner named either “Denis” or “Denise,” which implies candidate sexual orientation, depending on candidate gender revealed earlier. These partners were also referred to either as a “wife/husband and partner of 18 years” or “a former boyfriend/girlfriend,” to reinforce the candidate sexual orientation and to further imply marital status with references to their own children or the children of their former partner to reinforce their role as a parent. While it is difficult to introduce the distinction between a candidate involved in a current traditional stable relationship with children and one who has been in and out of relationships without having some differences in the text, we endeavored to use a similar storyline for both treatments with only slight variations (three sentences comprised of about 40 words) distinguishing them. We show complete stimulus wording and randomization checks in Supplementary MaterialsTheory Treatment details.

Measures

In this study, our dependent variable is the change in vote intention, with vote intention taken as repeated measures: The first vote intention measure is taken immediately after the delivery of the first experimental stimulus, in which the running candidate’s gender was implied. The second vote intention measure is taken after the delivery of the second experimental stimulus, in which we further implied sexual orientation and familial status. Both measured willingness to vote for the candidate on a ten-point ordinal scale. We expect some participants may be inclined to adjust their responses toward consistency with their first expression of vote intention. We will draw the implications of this in Discussion.

Prior to treatment delivery, we asked a standard battery of demographic questions, as detailed in Appendix A. In this analysis, we focus on those demographics that are typically correlated with support for LGBTQ candidates including: respondent age, gender, education, and sexual orientation. As regularly acknowledged in the literature, younger respondents who have grown up in a world that is more accepting of sexual diversity are more likely to support LGBTQ candidates than their elders. Women are less than men to be prejudiced toward lesbian and gays, and those with higher levels of education are often more liberal and accepting in their views. Sexual minority voters are more likely than straight voters to identify with and support sexual minority candidates. In addition, we asked attitudinal questions pertaining to respondent’s religiosity on a four-point ordinal scale ranging from “religion not important at all” to “very important,” respondent’s agreement with the statement “Society would be better off if more women stayed home with their children” measured on a five-point ordinal scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree,” respondent’s attitude to lesbians and gays on a ten-point scale with higher values indicating more favorable opinions, and respondent’s political ideology either “left,” “center,” or “right.” 8 These questions all serve to test relationships found in the literature between religiousity, traditional social norms, attitudes toward lesbian and gays and left right placement and willingness to support lesbian and gay candidates. The premise is that those who are more religious, more conservative, more traditional in their views and less favorable to sexual minorities are less likely to be willing to support them. We use these variables to explore causal heterogeneity.

It should be noted that we have chosen to not include measures for partisanship since, as stated above, partisanship does not play the same role in Canadian politics with regard to support or opposition to lesbians and gays as it does elsewhere. Partisanship is important to vote choice, but as we did not identify the party that the candidates were running for in our stimuli, it is not likely to have an effect in our results. Instead, we measure voters’ ideological positioning on a left-right scale. While there is evidence that social conservatives are more likely to align with the Conservative Party of Canada than other parties, they only make up a small portion of the party’s supporters (Gidengil et al., 2012). As recent work demonstrates, fiscal conservatives are not necessarily social conservatives and levels of what might typically be referred to as moral traditionalism are low even among conservatives and Conservative party supporters who would usually identify as being right wing (Belanger and Stephenson, 2017).

Analysis and Causal Heterogeneity

For simplicity, we first report ANOVA models using the change between the two vote intention measures as dependent variable, to understand the effect of the three randomized candidate characteristics: candidate gender, candidate sexual orientation, and candidate familial status (“main effects”). Higher order interactions will imply a joint effect across these three. We note that candidate gender can only be interpreted as a moderator of sexual orientation or familial status effects on the second vote intention measure but not as a main effect as candidate gender was held constant across the two stimuli.

We then expand on this by investigating response heterogeneity to understand whether our treatments of sexual orientation and familial status elicit different responses from electors from different social demographic backgrounds and holding different attitudinal positions. Our approach to treatment effect heterogeneity follows that described in Imai and Ratkovic (2013) imposing LASSO constraints to shrink some coefficients to zero thus better separating systematic effects from random variation.9 We are thus reporting more conservative estimates than simpler linear models would give us. In addition, the method is optimized to explore a large number of pre-treatment variables, particularly relevant in our case. In line with the recommended practice, we standardized all variables so that they are rescaled and expressed in standard deviation units, with 0 as their mean (p. 449).

Results

Descriptive Results

In the first baseline treatment, the only difference between candidates was that one was identified as a man and the other as a woman. Participant responses based on the short text stimulus appear insensitive to candidate gender as both groups produced an average likelihood to support of 5.95, t (911.75) = 0.06, p = 0.95. As our real interest is what happens to a candidate’s support once voters are cued to their sexual orientation and familial status, our dependent variable is the difference between vote intentions across the repeated measures.

Across the first and second measures of vote intention, respondents tended adjust their vote intention very minimally. On average their support declined by M = 0.29 point, which is less than an eighth of a standard deviation, SD = 2.39. In the sections below, we investigate effects on the within-subject change across the two dependent measures by sexual orientation and familial status, and benchmark both Average Treatment Effects and Conditional Average Treatment Effects to the reference group of straight single candidates. We provide further descriptive statistics in the Appendices A and B.

Main Effects

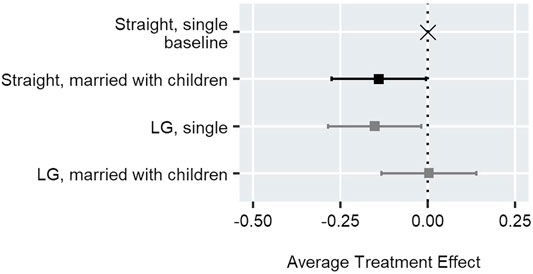

A two-way ANOVA by candidate sexual orientation and candidate relationship status suggests that citizens’ response to sexual minority candidates is linked to perceptions about respectability and norm conforming behavior, with a few caveats as we explain below. We do not find evidence of an effect associated with sexual orientation on its own, F (1,884) = 0.01, p = 0.91, meaning that respondents did not tend to change their vote intention once they learned that the candidate was lesbian or gay. There is also no effect associated with familial status on its own, F (1, 884) = 0.01, p = 0.92. There is, however, a significant interaction between sexual orientation and relationship status, F (1, 884) = 4.86, p = 0.02.

We investigated these relationship further in a linear regression framework–first for straight candidates and then for lesbian and gay candidates. We find that the marginal effect of familial status when candidate sexual orientation is held at baseline (i.e., straight candidates) is not significant, β = −0.15, p = 0.11 whereas the interaction effect of familial status with sexual orientation (i.e., lesbian and gay candidates who are married with children) is β = 0.29, p = 0.03. We thus cannot rule out null effects on straight candidates. When we rerun the analysis with the single lesbian or gay candidates as a baseline we find the same structure with the identical (this time negative) interaction effect and a similar (positive) main effect of familial status on lesbian and gay candidates, β = 0.14, p = 0.13. Thus, while in the case of lesbian and gay candidates the estimated differences were in the predicted directions, we do not have enough evidence to support our overall H1 expectations that candidates with nuclear families would be supported. This suggests that there is clearly the need for a more detailed examination of the interaction between sexual orientation and familial status. These patterns become clear in Figure 2 below where we show the Average Treatment Effects benchmarked to straight and single candidates in Figure 2 below.

FIGURE 2. Average Treatment Effects and 95% CI per group on the change in vote intention after revealing candidates’ sexual orientation (Straight, Gay or Lesbian) and familial status (single or married with children), expressed in standard deviation units (reported in Descriptive results), benchmarked to support for straight single candidates. N = 888.

While we note that the effect on straight candidates is in contrast to previous findings that suggest that voters tend to prefer candidates who are married over those who are single (Teele et al., 2017) it may be that in Canada marriage plays less of a role in evaluations of candidates than elsewhere. This is not something that has been academically tested to date and should perhaps be explored more carefully. We would also note that in this study, marital status is presented as an element of respectability politics,—although there is little reason to anticipate that straight candidates with families would be affected by this framing as they do not need to conform to the same norms of respectability that lesbian or gay candidates may need to meet. In addition, we speculate that a study that is powered to explore this particular treatment by presenting the full sample information about straight candidates only, would detect response heterogeneity depending on candidate gender and respondent characteristics.

Candidate gender was known to respondents before candidate sexual orientation and relationship status were revealed and, as noted above, had no demonstrable impact on respondents’ willingness to support a candidate. We thus investigated the moderating impact of candidate gender on the change in vote intention. Once again, in these ANOVA models, we failed to detect a significant interaction between candidate gender and candidate relationship status, F (1, 884) = 0.17, p = 0.68, between candidate gender and candidate sexual orientation, F (1, 884) = 0.02, p = 0.89, or a higher-order interaction across candidate gender, candidate sexual orientation, and candidate relationship status, F (1, 884) = 0.01, p = 0.94. In other words, the variations that we find in respondents’ levels of support for the married with children or single lesbian and gay candidates are not the result of the candidates’ gender. Instead, they are the result of the familial status itself.

Heterogeneity

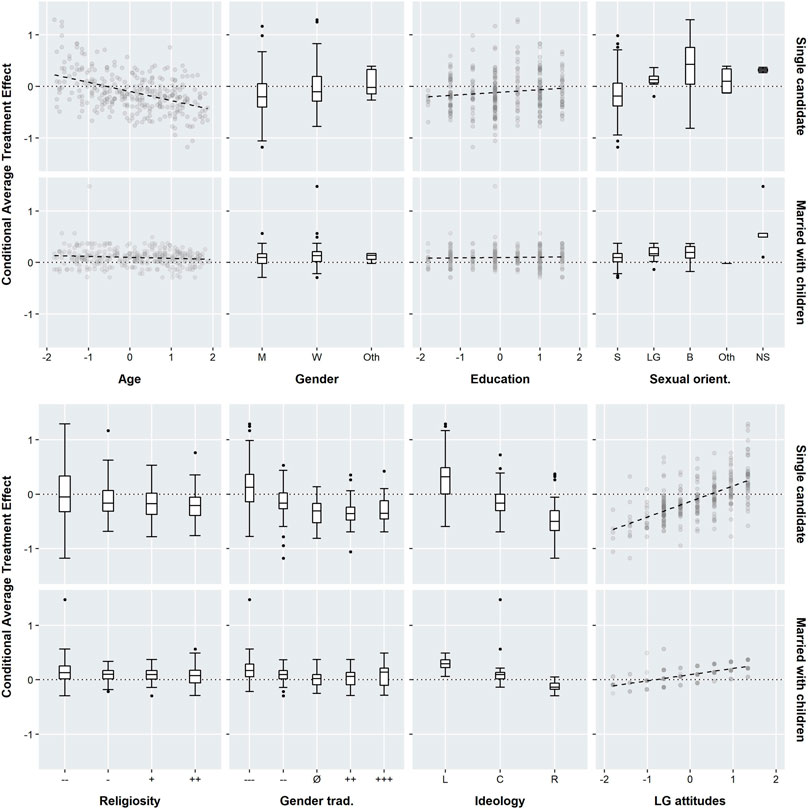

We then turn to exploring how respondent-varying characteristics moderate the impact of the treatment, namely how respondents with particular demographic and attitudinal characteristics changed their vote intention once they learned that their candidate was lesbian or gay, broken down by candidate relationship status. Figure 3 below shows an overview of Conditional Average Treatment Effects (CATE) in terms of voting for lesbian or gay candidates, conditional on the values of seven predictors, estimated in separate models for single and married with children candidates.

FIGURE 3. Conditional Average Treatment Effects (medians, IQR, and outliers) by candidate relationship status (rows) and pre-treatment covariates (columns) following Imai and Ratkovic (2013) as described in Analysis and causal heterogeneity. Dependent variable is post-treatment change in vote intention; treatment is exposure to gay or lesbian candidate. Continuous predictors standardized (scaled and centered, see Analysis and causal heterogeneity).

Our results, only partially supported our H2 in that familial status would not eliminate the impact that voters’ social demographic and attitudinal backgrounds would have on variations in responses to lesbian and gay candidates as we did find substantial heterogeneity in responses to lesbian or gay candidates when they were described as single. For example, at the higher end of the age range the conditional treatment effect turns negative for single candidates implying older respondents rejected them. Similar patterns appeared for the other variables under consideration. However, it was only under this treatment that voters respond in way that might have been predicted from the literature on attitudes toward LGBTQ candidates, with those who are older, male, straight, with lower levels of education, stronger religious, traditionalist and conservative views less likely to support these candidates than other sub groups of the population. In other words, individual-level characteristics and attitudes to sexual minorities moderate whether respondents supported or rejected a lesbian or gay single candidate.

By contrast, we find little variation in respondents’ likelihood of voting for a lesbian or gay candidate presented as married with children. In other words, characteristics we would normally expect to have a polarizing impact on support for lesbian and gay candidates mattered less when the candidates were respectably part of a nuclear family, and as a result, generally more supported. It is only when it comes to attitudes to sexual minorities and ideology that there is some heterogeneity in responses for these candidates. Voters’ levels of religiousity and their attitudes toward traditional gender roles have little impact on support for lesbians and gays who conform to heteronormative familial standards. Thus, our H2a is only partly confirmed by these results.

On the other hand, expectations based on H3 and affinity support among sexual minority respondents and lesbian and gay candidates did prove true. We can confirm little to no difference in support lesbian and gay identifying voters gave to either single or married lesbian and gay candidates. Despite the debate among the LGBTQ population about the impact that equal marriage might have on reinforcing heteronormative standards on the queer community, affinity support was strong for both the lesbian and gay single and married with children candidates, supporting H3a. We do, however note, that respondents unable to identify with either of these sexual minority categories, gave no support to lesbian and gay candidates. It is important to note that in terms of gender also respondents not identifying with the binary male or female categories were not more clearly supportive of lesbian and gay candidates, regardless of familial status.

Discussion

In the Canadian context, we find that citizens’ vote choice tends not to be influenced by candidate sexual orientation, at least when it comes to perceived cisgender lesbian or gay candidates. While these findings contradict other research on electoral support for sexual minorities it may be explained by our focus on the Canadian case in which general attitudes toward LGBTQ individuals tend to be higher than in countries such as the US and where debates around issues such as same sex marriage were addressed over a decade ago. Furthermore, lesbian and gay candidates have been openly running for office federally and provincially for over 3 decades and winning their seats for over two (Everitt and Camp, 2014). This suggests that candidate sexual orientation may not be an issue other countries in the world as it becomes clear that society has not been dramatically changed by their openness about their sexuality and the public becomes more familiar with and less threatened by them as candidates.

However, a lack of prejudice at the aggregate level may mask important underlying biases that persist toward sexual minorities based on other aspects of their lives that may continue to challenge dominant heterosexual social norms. Thus, we hypothesized, that in a country with over a decade-long experience with equal marriage, respectability politics and norm conforming behavior captured by familial status may continue to be influential in how citizens respond to sexual minority candidates. In participating in traditional heteronormative relationships, married sexual minority candidates with children behave like the majority of straight candidates and may pose less of a challenge to social institutions. This may account for why such a large number of out LGBTQ politicians in Canada are married or are in long-term common-law relationships (Tremblay forthcoming). On the other hand, single minority candidates may be perceived as less respectable and more disruptive and threatening to social norms and thus and receive lower levels of support.

We confirm that this effect is strongly suggestive in our study where lesbian and gay candidates who were part of a nuclear family appeared to receive electoral support comparable to that of straight single candidates, while single lesbian and gay candidates were penalized. These patterns become even clearer when we control for a range of factors typically linked to support for LGBTQ candidates. These interaction effects are consistent with our theoretical framework on respectability politics helping lesbian and gay candidates to achieve more support. The fact that similar effects are not true for straight candidates who were described as married with children is interesting, but does not weaken this argument, as straight candidates are not confronted by the same pressures to conform to “respectable” lifestyles that confront sexual minorities.

We also note that we displayed treatment stimulus in-between repeated measures of vote intention, potentially subject to consistency bias with respondents unlikely to change their initial vote intention, we still detected a small but significant pattern. We speculate this mechanism may be amplified outside of the experimental setting where such concern about consistency when learning about candidate sexual orientation does not apply. In addition, we show that the boost in support for “respectable” candidates is present across the board for respondents with a range of characteristics including those with less favorable attitudes to LGBTQ people in society. By contrast, responses to single lesbian or gay candidates are subject to a large degree of heterogeneity, where particularly older respondents with more traditional views on gender roles and/or right-wing ideology tended to withdraw support. In terms of affinity voting, we highlight that while lesbian and gay respondents tended to support lesbian and gay candidates regardless of familial status, respondents who identified with other sexual minority categories had a wider range of negative or positive responses.

We would conclude with one last observation about the heterogeneity that is revealed in examining the impact of familial status on voter support for lesbian and gay candidates. While not the main focus of our study, there is a wider difference of views on the single candidates than on those who were married with children. Our models tend to be more precise when it comes to lesbian and gay candidates who were married with children where the estimates have, generally speaking, a narrower range than in the model looking at single candidates–this is consistent with our interpretation so far that candidates with nuclear families were more supported. In other words, voters assessing the “respectable” candidates were fairly similar in their views, producing a narrower range of predictions by our model, whereas views appear much more conflicting in their responses about the single and less “respectable” candidates. We would refrain from more formal comparisons of the uncertainty of these predictions as originating from different models that converged separately, but it is intriguing and something that should be explored in more detail in future, potentially conjoint experiments. What is clear however from this study is that more research is needed into voter attitudes toward sexual minority candidates with diverse background and experiences to better understand the performance of the increasing number of LGBTQ candidates in many national elections.

Data Availability Statement

Data statement: Replication data and script are available on figshare, DOI: 10.6084/m9.figshare.14790915.v1.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Research Ethics Board at the University of New Brunswick (Saint John). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

The collection of data for this study and the open access publication fees were supported by internal university funding made available to JE by the University of New Brunswick. She also received a UNB Harrison McCain Foundation Visitorship Award enabling her to spend a month as a visiting fellow at the Q-Step Center at the University of Exeter. LH’s work was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council (ES/T015675/1, ES/V006320/1), part of United Kingdom Research and Innovation.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2021.662095/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

2This number includes seven members of the House of Representatives and two members of the Senate. At the state-level more than 240 LGBTQ candidates were on the general election ballot with more than half of them winning their election including Sarah McBride of Delaware who became the first transgender person to win a state Senate election (Moreau, 2020).

3We do not examine vote intentions to bisexual or transgender candidates because the treatment makes this difficult to assess. However, we would note that resent research suggest that in the case of trans candidates voters continue to hold strong negative biases (Jones, Brewer, Young, Lambe, and Hoffman. 2018; Jones and Brewer 2019).

4While creating a measure of familial status that includes both marriage and children may raise questions about the impact of these individual factors, it creates a strong test of “lesbian and gay respectability” by emphasizing relationship conformity and stability as compared to candidates who are single and who have been involved in more unstable and temporary relationships.

5https://news.gallup.com/poll/1651/gay-lesbian-rights.aspx

6Quest Mindshare is a Canadian research company specializing in providing online panels and web based survey support. The survey and all data was hosted on a server at the University of New Brunswick and Quest Mindshare shared a link to it to their pool of panelists.

7To ensure that the textual stimuli were realistic we wrote them with the assistance of a colleague who teaches university-level journalism. They were then reviewed by another colleague who worked for several years as a newspaper reporter covering local politics.

8While there is debate about the usefulness of the left-right spectrum due to concerns about whether people really understand these concepts (Converse, 1964; Conover and Feldman, 1984), this measure is commonly used in Canadian Election Surveys and has been demonstrated to be correlated with Conservative Party support in Canada (Belanger and Stephenson 2017).

9Implemented in Egami, Ratkovic and Imai (2012) in R.

References

Bailey, M., and Nawara, S. (2017). “Gay and Lesbian Candidates, Group Stereotypes, and the News Media,” in LGBTQ Politics: A Critical Reader. Editors M. Brettschneider, S. Burges, and C. Keating (New York: New York University Press), 334–349.

Bélanger, É., and Stephenson, L. B. (2017). “3. The Conservative Turn Among the Canadian Electorate,” in The Blueprint: Conservative Parties and Their Impact on Canadian Politics. Editors J. P Lewis, and J. Everitt (Vancouver: UBC Press), 46–77. doi:10.3138/9781487514020-003

Besco, R. (2019). Identities and Interests: Race, Ethnicity and Affinity Voting. Vancouver: UBC Press.

Besco, R. (2015). Rainbow Coalitions or Inter-minority Conflict? Racial Affinity and Diverse Minority Voters. Can. J. Pol. Sci. 48 (2), 305–328. doi:10.1017/S0008423915000396

Bird, K., Jackson, S. D., McGregor, R. M., Moore, A. A., and Stephenson, L. B. (2016). Sex (And Ethnicity) in the City: Affinity Voting in the 2014 Toronto Mayoral Election. Can. J. Pol. Sci. 49 (2), 359–383. doi:10.1017/s0008423916000536

Bird, K. (2009). “Running Visible Minority Candidates in Canada: The Effects of Voter and Candidate Ethnicity and Gender on Vote Choice,” in Democracy and Diversity Workshop Kingston, ON.

Bird, K. (2011). “The Local Diversity Gap: Assessing the Scope and Causes of Visible Minority Under-representation,” in Municipal Elections. The Political Immigrant: A Comparative Portrait Workshop (Montreal: Concordia University).

Brewer, P. R. (2003a). The Shifting Foundations of Public Opinion about Gay Rights. J. Polit. 65 (4), 1208–1220. doi:10.1111/1468-2508.t01-1-00133

Brewer, P. R. (2003b). Values, Political Knowledge, and Public Opinion about Gay Rights. Public Opin. Q. 67 (2), 173–201. doi:10.1086/374397

Casey, L. S., and Reynolds, A. (2017). “Standing Out: Transgender and Gender Variant Candidates and Elected Officials Around the World,” in LGBT Representation and Rights Research Initiative (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina).

Conover, P. J., and Feldman, S. (1984). Group Identification, Values, and the Nature of Political Beliefs. Am. Polit. Q. 12, 151–175. doi:10.1177/1532673X8401200202

Converse, P. E. (1964). “The Nature of Belief System in Mass Public,” in Ideology and Discontent. Editor D. Apter (New York: Free Press), 206–261.

Dabin, S., Daoust, J. F., and Papillon, M. (2019). Indigenous Peoples and Affinity Voting in Canada. Can. J. Pol. Sci. 52 (1), 39–53. doi:10.1017/s0008423918000574

Doan, A., and Haider-Markel, D. (2010). The Role of Intersectional Stereotypes on Evaluations of Gay and Lesbian Political Candidates. Polit. Gend. 6 (1), 63–91. doi:10.1017/s1743923x09990511

Duggan, L. (2003). The Twilight of Equality? Neoliberalism, Cultural Politics, and the Attack on Democracy. Boston: Beacon Press.

Egan, P. J., and Sherrill, K. (2005). Neither an In-Law Nor an Outlaw Be: Trends in Americans’Attitudes toward Gay People. Public Opinion ProsAvailable at https://nyuscholars.nyu.edu/en/publications/neither-an-in-law-nor-an-outlaw-be-trends-in-americans-attitudes (Accessed 16 June, 2021).

Environics, (2012). AmericasBarometer, Final Report. Toronto: The Environics Institute. Available at: https://www.environicsinstitute.org/docs/default-source/project-documents/americasbarometer-2012/final-report.pdf?sfvrsn=65954dab_2 (Accessed May 28, 2021).

Everitt, J., and Camp, M. (2014). In versus Out: LGBT Politicians in Canada. J. Can. Stud. 48 (1), 226–251. doi:10.3138/jcs.48.1.226

Everitt, J., and Lewis, J. P. (2020). “Executives in Canada: Adding Gender and Sexuality to Their Representational Mandate,” in Palgrave Handbook of Gender, Sexuality and Politics in Canada. Editors M. Tremblay, and J. Everitt (New York: Palgrave McMillian Press), 187–206. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-49240-3_10

Everitt, J. (2015). “LGBT Activism in the 2015 Federal Election,” in Canadian Election Analysis 2015: Communication, Strategy, and Canadian Democracy. Editors A. Marland, and T. Giasson (Vancouver: Samara/UBC Press). http://www.ubcpress.ca/.

Everitt, J., and Raney, T. (2019). “Winning as a Woman/Winning as a Lesbian: Kathleen Wynne and the 2014 Ontario Election,” in LGBT People and Electoral Politics in Canada. Editor M. Tremblay (Vancouver: UBC Press), 80–101.

Everitt, J., and Tremblay, M. (2020). LGBT Candidates and Elected Officials in North America. Online: Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics Oxford University Press.

Gidengil, E., Nevitte, N., Blais, A., Everitt, J., and Fournier, P. (2012). Dominance and Decline: Making Sense of Recent Canadian Elections. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Golebiowska, E. A., and Thomsen, C. J. (1999). “Group Stereotypes and Evaluations of Individuals: The Case of Gay and Lesbian Political Candidates,” in Gays and Lesbians in the Democratic Process: Public Policy, Public Opinion, and Political Representation. Editors E. D. B. Riggle, and B. L. Tadlock (New York: Columbia University Press), 192–219.

Golebiowska, E. (2001). Stereotypes and Political Evaluation. Am. Polit. Res. 29 (6), 537–538. doi:10.1177/1532673x01029006001

Goodyear-Grant, E., and Croskill, J. (2011). Gender Affinity Effects in Vote Choice in Westminster Systems: Assessing ‘flexible’ Voters in Canada. Polit. Gend. 7 (2), 223–250. doi:10.1017/s1743923x11000079

Goodyear-Grant, E., and Tolley, E. (2017). Voting for One’s Own: Racial Group Identification and Candidate Preferences. Polit. Groups Identities 7 (1), 131–147. doi:10.1080/21565503.2017.1338970

Goodyear-Grant, E. (2010). “Who Votes for Women Candidates and Why?,” in Voting Behaviour in Canada. Editors C. Anderson, and L. Stephenson (Vancouver: UBC Press), 43–64.

Green, A. I. (2013). “Debating Same-Sex Marriage,” in Debating Same-Sex Marriage within the Lesbian and Gay Movement. Editors M. Bernstein, and V. V. Taylor (Minneapolis: U of Minnesota Press), 375–406.

Haider-Markel, D., Miller, P., Flores, A., Lewis, D. C., Tadlock, B., and Taylor, J. (2017). Bringing “T” to the Table: Understanding Individual Support of Transgender Candidates for Public Office. Polit. Groups, Identities 5 (3), 399–417. doi:10.1080/21565503.2016.1272472

Haider-Markel, D. P., and Bright, C. L. M. (2014). “Lesbian Candidates and Officeholders,” in Women and Elective Office: Past, Present, and Future. Editors S. Thomas, and C. Wilcox. 3rd. ed. (New York: Oxford University Press), 253–272. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199328734.003.0015

Haider-Markel, D. P., and Joslyn, M. R. (2008). Beliefs about the Origins of Homosexuality and Support for Gay Rights: An Empirical Test of Attribution Theory. Public Opin. Q. 72 (2), 291–310. doi:10.1093/poq/nfn015

Haider-Markel, D. P. (2010). Out and Running: Gay and Lesbian Candidates, Elections, and Policy Representation. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press. doi:10.5749/minnesota/9780816681716.003.0012

Herek, G. M. (2002). Gender Gaps in Public Opinion about Lesbians and Gay Men. Public Opin. Q. 66 (1), 40–66. doi:10.1086/338409

Hicks, G. R., and Lee, T.-T. (2006). Public Attitudes toward Gays and Lesbians. J. Homosexuality 51 (2), 57–77. doi:10.1300/j082v51n02_04

Hinrichs, D. W., and Rosenberg, P. J. (2002). Attitudes toward Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Persons Among Heterosexual liberal Arts College Students. J. Homosexuality 43 (1), 61–84. doi:10.1300/j082v43n01_04

Imai, K., and Ratkovic, M. (2013). Estimating Treatment Effect Heterogeneity in Randomized Program Evaluation. Ann. Appl. Stat. 7 (1), 443–470. doi:10.1214/12-aoas593

Jones, P. E., and Brewer, P. R. (2019). Gender Identity as a Political Cue: Voter Responses to Transgender Candidates. J. Polit. 81 (2), 697–701. doi:10.1086/701835

Jones, P. E., Brewer, P. R., Young, D. G., Lambe, J. L., and Hoffman, L. H. (2018). Explaining Public Opinion toward Transgender People, Rights, and Candidates. Public Opin. Q. 82 (2), 252–278. doi:10.1093/poq/nfy009

Juvonen, T. (2020). Out Lesbian and Gay Politicians in a Multiparty System. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.1182

K. Bird, T. Saalfeld, and A. M. Wüst (Editors) (2011). The Political Representation of Immigrants and Minorities: Voters Parties and Parliaments in Liberal Democracies. New York: Routledge.

Kite, M. E., and Whitley, B. E. (1996). Sex Differences in Attitudes toward Homosexual Persons, Behaviors, and Civil Rights a Meta-Analysis. Pers Soc. Psychol. Bull. 22 (4), 336–353. doi:10.1177/0146167296224002

Lalancette, M., and Tremblay, M. (2019). “Media Framing of Lesbian and Gay Politicians,” in LGBT People and Electoral Politics in Canada. Editor M. Tremblay (Vancouver: UBC Press), 102–123.

Magni, G., and Reynolds, A. (2020). Voter Preferences and the Political Underrepresentation of Minority Groups: Lesbian, Gay, and Transgender Candidates in Advanced Democracies. J. Polit. doi:10.1086/712142

M. Bernstein, and V. Taylor (Editors) (2013). The Marrying Kind? Debating Same-Sex Marriage within the Lesbian and Gay Movement. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota Press.

Moreau, J. (2020). A Win for All of Us': Over 220 LGBTQ Candidates Celebrate Election Victories. ABC News https://www.nbcnews.com/feature/nbc-out/win-all-us-over-220-lgbtq-candidates-celebrate-election-victories-n1247551. (Accessed May 28, 2021)

Reynolds, A. (2013). Out in Office: LGBT Legislators and LGBT Rights Around the World “LGBT” Representation and Rights. Initiative at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. https://victoryinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/OutOfficialsINTL-Impact-UNC-ilovepdf-compressed.pdf. (Accessed May 28, 2021)

RNZ News (2020). New Zealand's New LGBTQ MPs Make Parliament Most Rainbow in World. https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/political/428800/new-zealand-s-new-lgbtq-mps-make-parliament-most-rainbow-in-world. (Accessed May 28, 2021).

Saad, L. (2015). Support for Nontraditional Candidates Varies by Religion. Gallup. June 24. http://www.gallup.com/poll/183791/support-nontraditional-candidatesvaries-religion.aspx. (Accessed May 28, 2021).

Schwarz, S., Hunt, W., and Coppock, A. (2020). What Have We Learned about Gender from Candidate Choice Experiments? A Meta-Analysis of 30 Factorial Survey Experiments. A Meta-analysis of 67 Factorial Survey Experiments. doi:10.7910/DVN/R27ULT

Schwindt-Bayer, L. A. (2010). Political Power and Women’s Representation in Latin America. New York: Oxford University Press.

Smith, T. W. (2011). Cross-national Differences in Attitudes towards Homosexuality. Charles R. Williams Institute on Sexual Orientation Law. University of California. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/81m7x7kb. (Accessed May 28, 2021).

Teele, D., Kalla, J., and Rosenbluth, F. M. (2017). The Ties that Double Bind: Social Roles and Women's Underrepresentation in Politics. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 11 (3), 525–541. doi:10.1017/S0003055418000217

Tremblay, M. (2019). (forthcoming) LGBQ Legislators in Canada: Out to Represent. Switzerland: Palgrave MacMillan.

Valverde, M. (2006). A New Entity in the History of Sexuality: The Respectable Same-Sex Couple. Feminist Stud. 32, 1155–1163. doi:10.2307/20459076

Keywords: LGBTQ candidates, survey experiment, affinity voting, familial status, causal heterogeneity

Citation: Everitt J and Horvath L (2021) Public Attitudes and Private Prejudices: Assessing Voters’ Willingness to Vote for Out Lesbian and Gay Candidates. Front. Polit. Sci. 3:662095. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.662095

Received: 31 January 2021; Accepted: 10 June 2021;

Published: 28 June 2021.

Edited by:

Ignacio Lago, Pompeu Fabra University, SpainReviewed by:

Bram Wauters, Ghent University, BelgiumScott Matthews, Memorial University of Newfoundland, Canada

Copyright © 2021 Everitt and Horvath. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Joanna Everitt, amV2ZXJpdHRAdW5iLmNh

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Joanna Everitt

Joanna Everitt Laszlo Horvath

Laszlo Horvath