- 1Department of Political Science, Susquehanna University, Selinsgrove, PA, United States

- 2Department of Politics and Government, Illinois State University, Normal, IL, United States

A growing body of research suggests a significant relationship between dark personality traits and political behavior. While the personality characteristics of Machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy (labeled the Dark Triad) are associated with a range of political attitudes, research has not tested the Dark Triad in combination with the emerging use of the comparable Light Triad of personality. This paper sets up an exploration of the competing influences of light and dark personality traits on political participation and ambition. Our analyses corroborate that Dark Triad traits are significantly related to ambition and political participation. Consistent with prior research, the dark personality traits remain predominant. However, there are significant effects for some Light Triad traits as well. Our findings have implications for a deeper understanding of the mix of personality traits that drive political behavior and expand upon the normative discussion of who is, in fact, political.

Introduction

The study of personality and politics spans decades from the Freudian approaches adapted to politics by Harold Lasswell (1948) to the modern exploration of the Big 5 and its political correlates Mondak (2010). While the Big 5 remains the dominant framework for understanding personality in politics, emergent research pushes beyond the broad traits and measurement of the Big 5 to explore the influence of more individualized personality types. The Dark Triad (consisting of Machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy) has proven especially fruitful in studies examining a variety of political attitudes and behaviors (Hodson, et al., 2009; Blais and Pruysers 2017; Peterson and Palmer 2019; Pruysers, et al., 2019; Chen, et al., 2020). Whether helping scholars unpack questions of the personality determinants of nascent ambition (Blais and Pruysers 2017; Peterson and Palmer 2019) or understand an individuals’ orientations toward politics more generally, dark personality traits lend significant explanatory power even when controlling for conventional explanations (Chen, et al., 2020). If we understand politics to be at times a dark place with competition and conflict endemic to the endeavor, it makes sense that some individuals would be drawn to politics while others might be repelled.

However, participation and ambition are driven by more than the aforementioned dark personality traits. A new paradigm dubbed the Light Triad taps positive personality traits nearly diametrically opposed to the Dark Triad. The Light Triad, a constellation of traits consisting of faith in humanity, Kantianism, and humanism, provides a framework of positive traits that also influence individual attitudes and behaviors (Kaufman, et al., 2019). However, compared to the numerous papers on the Dark Triad (Paulhus and Williams 2002; Chabrol, et al., 2009; Jones and Paulhus 2010; Rauthmann and Kolar 2012; Muris, et al., 2017), the Light Triad is new and relatively untested in the realm of political behavior (see Neumann, et al., 2020 for an observational application of the Light and Dark Triad to U.S. Senators).

The contrast and competition between light and dark traits provide an opportunity for political psychology to test the persistence of the Dark Triad in explaining political behavior against the positive influence of the Light Triad. While politics can be a dark place, do more positive personality traits concurrently drive people to engage with politics? Can the concept of the Light Triad provide leverage to better understand why people express the desire to run for office, and perhaps, provide a more normatively palatable distillation of ambition? Broadly, is there merit to using the previously untapped concept of the Light Triad to study political behavior? To test these questions, we conducted an online survey of 800 respondents using Amazon’s Mechanical Turk in the Fall of 2020.

We find, consistent with previous research, that individuals broadly higher in Dark Triad traits like Machiavellianism, psychopathy, and narcissism are likely to express greater nascent political ambition, as well as being more likely to engage in political participation. We also find significant effects for certain Light Triad traits, though these effects are less consistent and less impactful than dark traits. The results have implications for understanding the traits that drive people to politics and whether dark or light personality traits win out when studying political behavior.

Dark Traits, Personality, and Political Correlates

A sizable body of research in psychology explores the Dark Triad and its influence on attitudes and behaviors (Paulhus and Williams 2002; Vernon, et al., 2008; Jonason, et al., 2009; Jonason and Webster 2010; Jones and Paulhus 2010; Rauthmann and Kolar 2012). The Triad consists of Machiavellianism (the tendency to engage in manipulation of others for one’s own ends), narcissism (an inflated sense of self-worth), and psychopathy (lack of empathy or remorse for actions) (Paulhus and Williams 2002). In social life, these subclinical dark personality traits are associated with a host of negative behaviors and attitudes. Machiavellians exhibit highly selfish behavior, seeking to maximize the accomplishment of their own end goals at the expense of those around them as well as being comfortable using lies or deception to achieve goals (Jones and Paulhus 2009). Narcissism is a complicated collection of characteristics, including an exaggerated sense of self-worth and individual importance (Raskin and Terry 1988) and self-love (Vernon, et al., 2008). Finally, psychopathy consists of a number of antisocial behaviors, including low levels of empathy and higher levels of impulsiveness (Cleckley 1955; Bishop and Hare 2008).

Politics is social, yet also requires different interests, and perhaps even a different skillset than everyday life. The dimensions of politics that repel some people (conflict, strategizing, competition, and exposure to the public eye) are features that propel others into politics: from social behaviors like attending rallies to the costliest form of participation—running for office. When exploring ambition in particular, a healthy research agenda examines how gender influences nascent ambition and why women are less likely to be politically ambitious than men (Fox and Lawless 2011; Lawless and Fox 2015; Preece, et al., 2016; Schneider, et al., 2016; Crowder-Meyer 2018; Pruysers and Blais 2018). Other scholars investigate how variation in personality traits like the Big 5 and social background beyond gender affects nascent ambition (Allen and Cutts 2017; Blais and Pruysers 2017; Allen and Cutts 2018; Dynes, et al., 2019).

Ambitious, competitive, and dark personality traits in social life are also significant predictors of political ambition. Whether it is the desire to run or the belief that one is qualified for office, recent scholarship provides evidence that the Dark Triad is related to political ambition (Blais and Pruysers 2017; Peterson and Palmer 2019). Blais and Pruysers, 2017, in their initial study, find a significant role for Machiavellianism and narcissism in perceptions of one’s qualification for and future success in a political career. A follow-up by Peterson and Palmer (2019) expands upon this, demonstrating a role for Machiavellianism not only in the considerations of a political career, but also an interest in engaging in the acts required to run for office, while narcissism was connected most consistently to the desire to run for office.

While this research is still emerging, an initial consensus of such work is that individuals higher in the Dark Triad are more likely to view themselves and qualified to run and more likely to have thought about running for office (Blais and Pruysers 2017; Peterson and Palmer 2019). Furthermore, when exploring broader participation, Chen et al. (2020) find that narcissism and psychopathy have a direct influence on political participation, and notably, narcissism is related to higher political interest but lower political knowledge (Chen, et al., 2020).

The emerging conception of the Light Triad seeks to overtly rebalance the scholarly narrative and normative dialogue around personality by emphasizing the role of positive traits in psychology (Kaufman, et al., 2019). While the Light Triad is a new conception of positive traits, psychology has frequently explored prosocial traits like self-esteem, altruism, gratitude, intellectual humility, mindfulness, morality, among others (Kaufman et al., 2019, p. 2). The Light Triad is particularly appealing as a comparison in political behavior because it is designed to capture aspects of personality that represent the opposite side of the coin to the Dark Triad. The Light Triad consists of Kantianism, or the view that individuals have a distinct purpose, rather than merely a means to an end; humanism, or the belief in the worth of everyone, as opposed to emphasizing one’s own self-worth; and faith in humanity, or the idea that all persons are fundamentally good (Kaufman, et al., 2019). In building the Light Triad, Kaufman and coauthors used the following question as motivation: “what would an everyday loving and beneficent orientation toward others look like that is in direct contrast to the everyday antagonistic orientation of those scoring high on dark traits” (2). Thus, the purpose is to overtly juxtapose the Light Triad with the dominant research paradigm of the Dark Triad. Despite the interconnected origins of the concept, Kaufman and his colleagues (2019) find that the Light Triad is distinct from the Dark Triad both conceptually and empirically.

To our knowledge, no research in political psychology broaches the direct contrast between the Dark Triad and its emergent competitor despite the archetypal allure of a light vs. dark framework.1 Empirically, inclusion of the Light Triad provides the ability to test the extent that positive traits (rather than their negative counterparts) spur political engagement and political aspirations. Ultimately, scholarship shows that political ambition and participation are correlated with numerous aspects of an individual, including personality, demographics, social backgrounds (Fox and Lawless 2011; Schneider et al., 2016; Allen and Cutts 2017; Pruysers and Blais 2018; Dynes et al 2019). The following analysis further elaborates on the diversity of traits and motivations that connect individuals to politics by setting up a direct comparison between the Dark Triad and Light Triad.

Materials and Methods

Our test of the political effects of the Dark Triad vis a vis the Light Triad is based upon an online survey conducted via Amazon MTurk in the Fall of 2020. The sample consists of 804 participants who opted in from MTurk in exchange for cash payments. Overall, the sample was 74% white, 10% African American, 6% Hispanic, 7% Asian, and 2% other race. Politically, respondents were 56% Democrat (including leaners), 34% Republican (including leaners), and 9% identifying as independents. The survey contained an initial demographic battery, and the three key modules: the measurement of personality (the Dark and Light Triad), political ambition, and political participation.

Our measure of the Dark Triad uses the “dirty dozen” battery to capture the Dark Triad (see Supplementary Appendix for the full question wording of the battery) (Jonason and Webster 2010; Jonason and McCain 2012).2 The scales demonstrate strong reliability with the Machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy items scaling together with alpha values of 0.95, 0.93, and 0.91, respectively. Scholars debate whether the Dark Triad should be analyzed as a global dark trait (“unification perspective”) or as individual traits (“uniqueness perspective”) given the substantial correlation between Machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy (Muris, et al., 2017; Rauthmann and Kolar, 2012). Research in political behavior has opted to use the individual traits in model specification, and we follow this approach by including Machiavellinism, narcissism, and psychopathy in our models. However, we also estimate models using the overall Light and Dark Triads to test the influence of the respective global constructs on our dependent variables.To measure the Light Triad we use the battery designed by Kaufman et al. (2019), which parallels the dirty dozen Dark Triad battery by using 12 total items to capture faith in humanity, humanism, and Kantianism. Much like the Dark Triad, we find the Light Triad items are quite reliable, with Faith in Humanity scaling with an alpha of 0.88, Humanism with an alpha of 0.82, and Kantianism with an alpha of 0.77.

Our dependent variables are designed to capture two dimensions related to political engagement: political ambition and participation. First, we analyze the two standard measures of nascent ambition (asking respondents whether they have thought about running for political office and how qualified they feel they are to run for office). To capture participation, we ask respondents to respond to a broad battery of 14 items tapping political participation beyond voting, measured by the respondent’s frequency of engaging in each activity from never to more than five times. Each participation item is measured using a 4-point scale. Following the example of Chen et al. (2020), we separate the participation items into three categories of activity: Political, Social, and Charitable participation. Full question wording for the personality traits and participation items are in Supplementary Appendix A.

Our models also include a host of control variables both demographic and political that are associated with nascent ambition and participation in prior research. These control variables include: gender (coded as female “1” and male “0”), age in years (running from 18 to 70), education (less than high school to graduate/professional degree), income (measured in categories from less than $10K to more than $150K), strength of partisanship (running from leaners to strong partisans), and race (coded as nonwhite “1” and white “0”). All variables are rescaled to run from 0 to 1 for ease of comparability.

Results

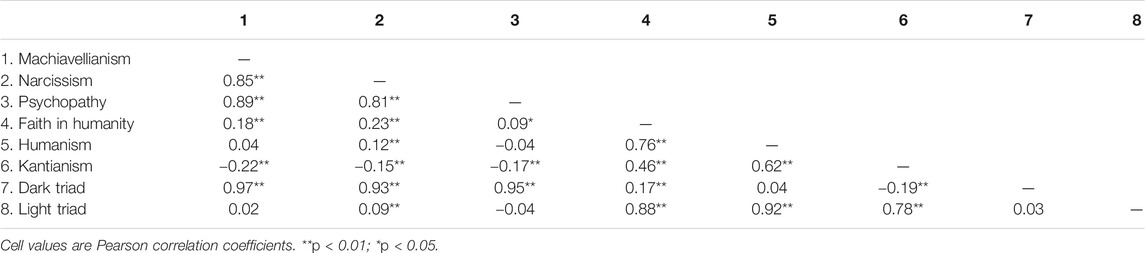

Broadly, given the nature of politics, we expect that Dark Triad traits will continue to be significant correlates of ambition and participation, even when introducing the Light Triad into the equation. On the light side, Faith in Humanity and Humanism might be significant in politics, but Kantianism with its focus on authenticity will likely not be a strong correlate to political action. The analysis proceeds by first presenting a correlation matrix of the Dark and Light Triad traits before moving to our multivariate analyses. The correlation matrix appears in Table 1 below.

Among the Triad traits, we see quite strong correlations between the Dark Triad traits, as Machiavellianism correlates with narcissism at 0.85 and Psychopathy at 0.89, and Narcissism with Psychopathy at 0.81. Correspondingly, the interrelationships among the Light Triad traits are not quite as pronounced, with Faith in Humanity correlating with Humanism at 0.76, but only 0.46 with Kantianism, and Humanism at 0.62 with Kantianism. More interestingly, the Dark and Light Triad items are essentially uncorrelated with one another, with the strongest of the correlations between any item 0.22, similar to patterns found in Kaufman et al. (2019).

The Triads and Political Ambition

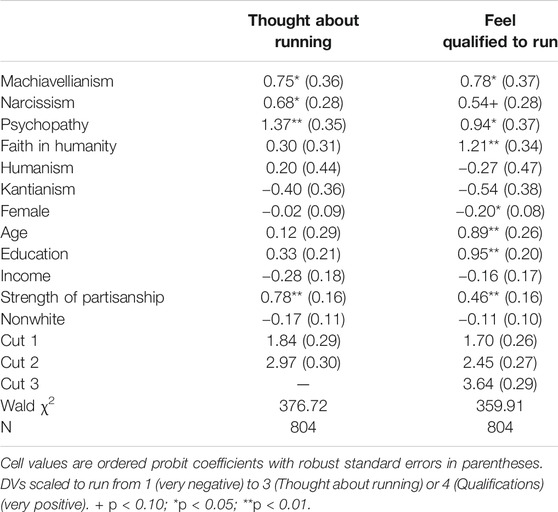

Our approach to testing the relationship between the Dark Triad, Light Triad, and nascent ambition uses two classic questions: has the respondent thought about running for office and how qualified do they see themselves to run for office. For each dependent variable in our analysis, we first include the individual Light and Dark Triad traits, as well as several demographic and political control variables. Further, we subsequently model the relationship using the global Dark and Light Triad. The findings from our ambition models are presented in Tables 2, 3, where the dependent variables are whether the respondent had thought about running for office and how qualified they felt to run for office.

Beginning with the Dark Triad, we seeeach of the traits are positive and statistically significant in both models, with the slight exception of Narcissism in the “qualified” model which is nearly significant at conventional levels (p = 0.053). The more an individual reports dark traits, the more likely they are to respond as having thought about running for office and feeling qualified. These robust effects are present, even while including the competing Light Triad traits and control variables. Similar to previous studies, the Dark Triad retains its substantial relationship to nascent ambition. On the other hand, only one Light Triad trait is significant; Faith in Humanity is positive and significant in the qualified to run model. Individuals who score higher in trusting other people and believing that people are largely good are more likely to view themselves to be qualified to run for office. In contrast, the other legs of the Light Triad (Kantianism and Humanism) fail to reach statistical significance in either model.

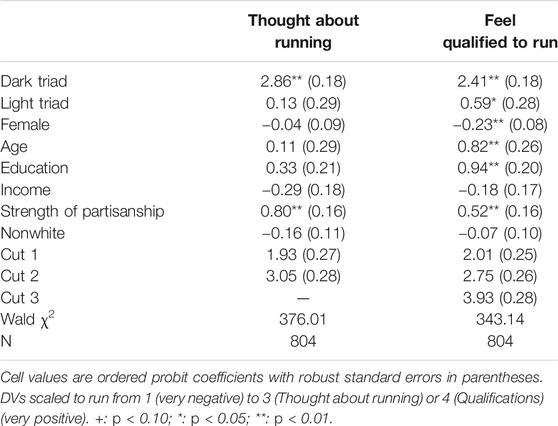

As we noted above, considering the Triad trats individually is not the only way to examine their predictive power, and in fact, scholars have analyzed the Dark Triad as a global trait rather than as its individual constituent parts. To explore whether the global traits have predictive power, we replace the individual traits with global constructs in the ambition models. The results are presented in Table 3.

Similarly to the models that disaggregated the Triad traits, we see that among the global traits, the Dark Triad predominates, with positive and significant effects for both ambition items, while the global Light Triad is significant only for respondents’ perceived qualification to run for office.

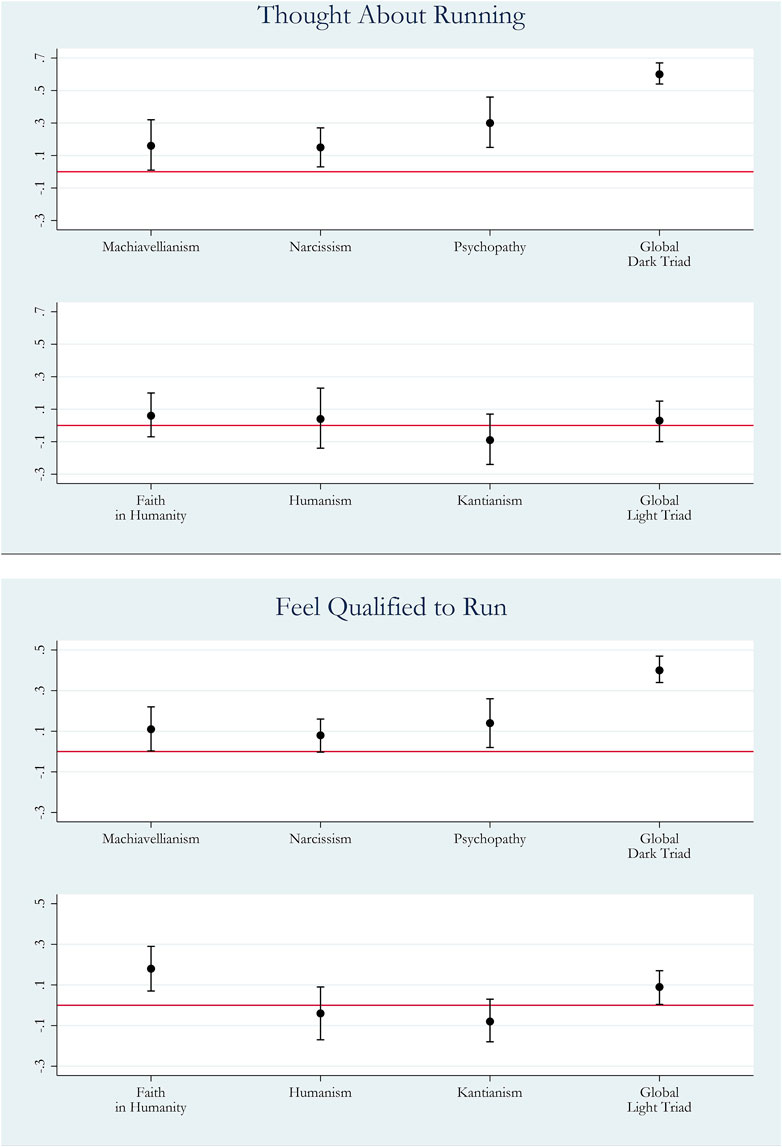

The consistency of the Dark Triad in predicting nascent political ambition at the expense of the Light Triad does not, however, address the question of the substantive impact of the individual and global traits. While the Dark Triad is a more likely predictor, which of the individual or global traits has the largest substantive effect in shaping ambition?

To illustrate the substantive effects of the Triad traits on the likelihood of expressing the highest level of ambition (having thought about running for office many times and feeling qualified/very qualified to run for office, respectively), we generate marginal effects for the highest category of each dependent variable, holding all other variables constant at their means. Due to the scaling of the Triad items, the point estimates represent the maximal shift in the variable (the difference of being at the top vs. the bottom of the scale), and are presented with 95% confidence intervals These effects appear in Figure 1.

In both panels of Figure 1, the story is quite clear, and reinforces the empirics from Tables 2, 3. Not only are the Dark Triad traits more consistent predictors of both components of political ambition, their substantive impact is larger as well. This is particularly clear when we consider the relative impact of the global traits—the global Dark Triad has an increase in the likelihood of having thought about running of approximately 0.6, while for the Light Triad the effect is indistinguishable from 0. While the effects for feeling qualified to run are more modest across the board, the Dark Triad’s effects are still substantively larger (a 0.4 point increase in the likelihood as compared to only a 0.1 increase).

The Triads and Political Participation

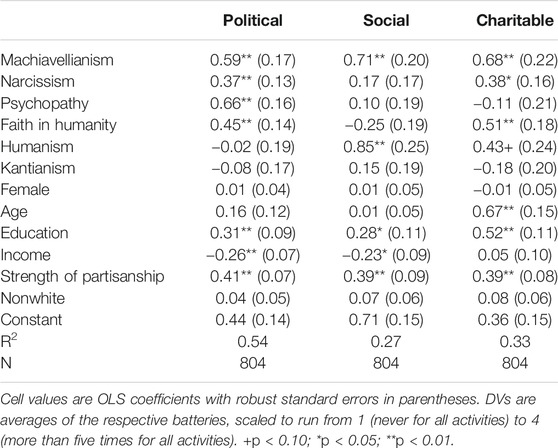

The final analyses focus on engaging in a series of participatory acts beyond the simple act of voting across three dimensions: political participation, social participation, and charitable participation. We utilize a 14-item participation battery, where each activity is measured on a 4-point scale describing frequency of engagement (1 = never, 4 = five or more times in the last 12 months). Following the example of Chen et al. (2020), we break the 14 items into three separate scales, following their categorization: political (six items, alpha reliability of 0.91), social (five items, alpha reliability of 0.83), and charitable participation (three items, alpha reliability of 0.75)3 (Chen, et al., 2020). These dimensions of behavior, while correlated, are theoretically distinct.4 We again focus on models including both Dark and Light Triad items for these three outcomes in Table 4 below.

Respondents scoring higher in Machiavellianism are positively inclined to participate across all dimensions of participation, be it political, social, or charitable. Among the remaining Dark Triad traits, we see that Narcissism is, positive and significant with respect to political participation as well as charitable participation, but not social participation. Also, perhaps most important to note, while psychopathy has a positive and significant effect with respect to political participation, it is unrelated to both social and charitable participation. While there may be a role for psychopathy in politics, these findings would suggest its plays less of a role social and charitable participation.

When examining the Light Triad traits, we see mixed results. Faith in Humanity is positive and significantly related elements of participation for political and charitable participation, but is unrelated to social participation. Humanism, while insignificant with respect to political participation, is positive and significant in the social participation model, and approaches conventional levels of significance in the charitable participation model (p = 0.07).The final of the traits, Kantianism, appears to be empirically unrelated to any form of participation, whether political, social, or charitable.

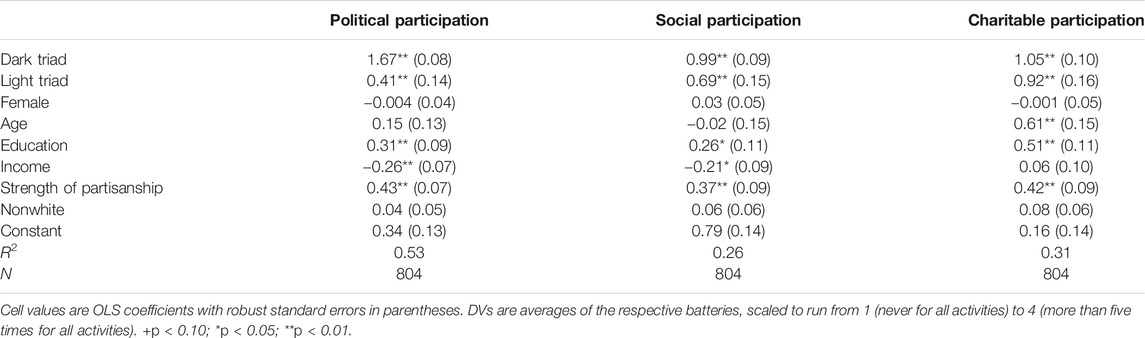

To further supplement these analyses, as we did with our examination of political ambition, we consider the effects of the global Triad traits on participation in Table 5.

Analyzing the global Triad traits with respect to participation provides a further bookend to the pattern we have observed throughout our analyses, albiet with more consistent effects for the Light Triad. Both global Triad measures are positive and significant for all forms of participation, political, social, and charitable. This lends credence to the usefulness of considering the overall Light Triad in participation. However, what becomes more interesting is the effect sizes of the global traits. Because these models are OLS and the Triad measures are comparably scaled, the coefficients are directly comparable. It is striking how the gap between Dark and Light Triad traits shrinks across forms of participation. From politics, where the effect of the Dark is more than four times as large as the Light, to social participation, where the difference is 0.3, to charitable participation, where the differences are negligible at best. This makes sense given the differing motivations at play between political participation and social or charitable participation. One clear take away from the analysis is that Dark Triad (overall or the constituent traits) is predominant in political participation, carrying substantially larger predicted effect than the Light Triad.

Discussion

Summary of Findings: In this paper, we have sought to not only replicate, but extend our understanding of the relationship between personality and political engagement. Utilizing survey data, we set the Dark and Light Triad against one another, examining the relationships between common components of political ambition and more extensive elements of sociopolitical participation. Building from models incorporating the Dark Triad of personality by including the newly developed counterpart the Light Triad, we find evidence that the Dark Triad is predominant in models of ambition and participation; Light traits are sporadic predictors of behavior compared to the dark traits. While the Dark Triad traits, namely Machiavellianism have the most consistent relationship to not only ambition, but also social participation outside the political realm, dark traits are not the only ones relevant for politics. We find meaningful effects for two of the Light Triad traits, Faith in Humanity and Humanism, in relation to political ambition and participation, respectively. Researchers have found leverage in political behavior by exploring dark traits. This focus is with good reason; dark traits are robust correlates of political ambition and participation even when controlling for the positive constellation of the Light Triad. While the Light Triad provides a normatively palatable approach to trait-based research, our analysis finds that the Dark Triad is the more substantial correlate of the domains of ambition and participation.

Limitations

Our findings are not without limitations. As with any personality research utilizing convenience samples, there is a concern that individuals of certain traits are attracted to opting in to surveys. While this is to some degree a valid concern, studies of online convenience sampling including MTurk has shown slight differences in traits such as extraversion as compared to more traditional representative samples (Goodman, et al., 2013), these differences are slight, and do not persist across all dimensions of personality (Holden, et al., 2013), nor do they prevent standard findings obtained from representative samples from being replicated using online convenience samples (Berinsky, et al., 2012). Another possible concern comes from brief measures to capture the Triad traits. While these batteries have been validated, albeit underutilized to date in the case of the Light Triad, there remains a question of whether a more detailed measure of these traits would tease out additional nuance in these relationships that our data cannot capture in its limited form.

Merits and Directions for Future Research: Constructing an empirical battle between light and dark traits necessitates an inevitable normative discussion on the motivations of political action. Do the robust effects of dark traits on ambition and participation paint a bleak picture for representation and political action? We are inclined to stress that many motivations (both dark and light and gray) likely orient individuals to politics. Not all politics is House of Cards. Personality is but one of many drivers of political participation, and there are positive motives that prime people to engage in politics. Our analysis incorporates the possibility that a “Lighter Side” of personality with positive motivations might drive people to engage in politics, but our most consistent Light Triad effects are shown in social and charitable participation. Especially when used as a global trait, the Light Triad does show signs that it could influence future research and potentially other domains of political behavior. Without further exploration and comparison of positive personality traits like honesty-humility, we are hesitant to eschew or embrace the Light Triad.

Furthermore, our paper does not broach the interplay between the Big 5 and the Light Triad. Kaufman and colleagues found significant correlation between the Light Triad and some of the Big 5 traits and in particular Agreeableness (Kaufman et al., 2019). While Big 5 traits are not inherently nor conceptually as valenced as the Light and Dark Triad, the prosocial and positive aspects like Openness to Experience, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness are related to political beahvior. In this way, lighter traits beyond the simply Light Triad can influence politics, implying that politics is not solely the realm of darkness.

Citizen engagement is a vital part of democratic governance, with citizen willingness to act on behalf of causes and policies important to them, and even to answer the call to run for office. This application of the Light Triad to political ambition and participation is only a first step, but our findings pitting the Dark and Light Triad traits against one other offer at least a modicum of hope that it is not only individuals with the dark traits who are drawn to politics. In our empirical analysis, the dark is certainly rising, but there is room for positive personality traits to influence political life. Further research will refine the role that personality plays in the question of who chooses to engage with politics.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Susquehanna University IRB. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

Funding for the research conducted was provided by a Susquehanna University mini-research grant.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2021.657750/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1Research in political science has included other positive traits, such as self-esteem (Sniderman 1975; Wolak and Stapleton 2020), as well as those utilizing the HEXACO model of personality which includes the trait of honesty-humility (Chirumbolo and Leone 2010).

2While used in many studies on the Dark Triad, the Dirty Dozen has been critiqued in psychology as a measure of dark traits. See Kajonius et al. (2016) for an empirical look at the strengths and limitations of the Dirty Dozen as a reduced-item measure of the Triad.

3Items are broken down by category along with full question wording in Supplementary Appendix A.

4We do not examine voting behavior in these analyses as 93% of the sample self-report voting on or before election day in the 2020 election.

References

Allen, P., and Cutts, D. (2018). An Analysis of Political Ambition in Britain. Polit. Q. 89, 73–81. doi:10.1111/1467-923x.12457

Allen, P., and Cutts, D. (2017). Aspirant Candidate Behaviour and Progressive Political Ambition. Research & Politics 4 (1). doi:10.1177/2053168017691444 January-March 2017.

Berinsky, A. J., Huber, G. A., and Lenz, G. S. (2012). Evaluating Online Labor Markets for Experimental Research: Amazon.Com's Mechanical Turk. Polit. Anal. 20, 351–368. doi:10.1093/pan/mpr057

Bishop, Daz., and Hare, Robert. D. (2008). A Multidimensional Scaling Analysis of the Hare Pcl-R: Unfolding the Structure of Psychopathy. Psychol. Crime L. 14, 117–132.

Blais, J., and Pruysers, S. (2017). The Power of the Dark Side: Personality, the Dark Triad, and Political Ambition. Personal. Individual Differences 113, 167–172. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2017.03.029

Chabrol, H., Van Leeuwen, N., Rodgers, R., and Séjourné, N. (2009). Contributions of Psychopathic, Narcissistic, Machiavellian, and Sadistic Personality Traits to Juvenile Delinquency. Personal. Individual Differences 47, 734–739. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2009.06.020

Chen, P., Scott, P., and Blais, J. (2020). The Dark Side of Politics: Participation and the Dark Triad. Political Studies. doi:10.1177/0032321720911566

Chirumbolo, A., and Leone., L. (2010). Personality and Politics: The Role of the Hexaco Model of Personality in Predicting Ideology and Voting. Personal. Individual Differences 49, 43–48. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2010.03.004

Cleckley, H. M. (1955). The Mask of Sanity: An Attempt to Clarify Some Issues about the So-Called Psychopathic Personality. 3rd ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby.

Crowder-Meyer, M. (2018). Baker, Bus Driver, Babysitter, Candidate? Revealing the Gendered Development of Political Ambition Among Ordinary Americans. Political Behav. 42 (2), 359–384. doi:10.1007/s11109-018-9498-9

Dynes, A. M., Hassell, H. J. G., and Miles, M. R. (2019). The Personality of the Politically Ambitious. Polit. Behav. 41, 309–336. doi:10.1007/s11109-018-9452-x

Fox, R. L., and Lawless, J. L. (2011). Gaining and Losing Interest in Running for Public Office: The Concept of Dynamic Political Ambition. J. Polit. 73, 443–462. doi:10.1017/s0022381611000120

Goodman, J. K., Cryder, C. E., and Cheema, A. (2013). Data Collection in a Flat World: The Strengths and Weaknesses of Mechanical Turk Samples. J. Behav. Dec. Making 26, 213–224. doi:10.1002/bdm.1753

Hodson, G., Hogg, S. M., and MacInnis, C. C. (2009). The Role of “dark Personalities” (Narcissism, Machiavellianism, Psychopathy), Big Five Personality Factors, and Ideology in Explaining Prejudice. J. Res. Personal. 43, 686–690. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2009.02.005

Holden, C. J., Dennie, T., and Hicks, A. D. (2013). Assessing the Reliability of the M5-120 on Amazon's Mechanical Turk. Comput. Hum. Behav. 29, 1749–1754. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2013.02.020

Jonason, P. K., Li, N. P., Webster, G. D., and Schmitt, D. P. (2009). The Dark Triad: Facilitating a Short‐term Mating Strategy in Men. Eur. J. Pers 23, 5–18. doi:10.1002/per.698

Jonason, P. K., and McCain, J. (2012). Using the Hexaco Model to Test the Validity of the Dirty Dozen Measure of the Dark Triad. Personal. Individual Differences 53, 935–938. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2012.07.010

Jonason, P. K., and Webster, G. D. (2010). The Dirty Dozen: A Concise Measure of the Dark Triad. Psychol. Assess. 22, 420–432. doi:10.1037/a0019265

Jones, D. N., and Paulhus, D. L. (2010). Different Provocations Trigger Aggression in Narcissists and Psychopaths. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 1, 12–18. doi:10.1177/1948550609347591

Jones, D. N., and Paulhus, D. L. (2009). Machiavellianism. in Individual Differences in Social Behavior. Editors Mark. R. Leary, and Rick. H. Hoyle (New York: Guilford), 93–108.

Kajonius, P. J., Persson, B. N., Rosenberg, P., and Garcia, D. (2016). The (Mis)Measurement of the Dark Triad Dirty Dozen: Exploitation at the Core of the Scale. PeerJ Life Environ. 4, e1748. doi:10.7717/peerj.1748

Kaufman, S. B., Bryce Yaden, D., Hyde, E., and Tsukayama, E. (2019). The Light vs. Dark Triad of Personality: Contrasting Two Very Different Profiles of Human Nature. Front. Psychol. 10, 1–26. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00467

Lawless, J. L., and Fox, R. L. (2015). Running from Office: Why Young Americans Are Turned off to Politics. New York: Oxford University Press.

Mondak, J. J. (2010). Personality and the Foundations of Political Behavior. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511761515

Muris, P., Merckelbach, H., Otgaar, H., and Meijer, E. (2017). The Malevolent Side of Human Nature. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 12, 183–204. doi:10.1177/1745691616666070

Neumann, C. S., Kaufman, S. B., Brinke, L. t., Yaden, D. B., Hyde, E., and Tsykayama, E. (2020). Light and Dark Trait Subtypes of Human Personality – a Multi-Study Person Centered Approach. Personal. Individual Differences 164, 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2020.110121

Paulhus, D. L., and Williams, K. M. (2002). The Dark Triad of Personality: Narcissism, Machiavellianism, and Psychopathy. J. Res. Personal. 36, 556–563. doi:10.1016/s0092-6566(02)00505-6

Peterson, R. D., and Palmer, C. L. (2019). The Dark Triad and Nascent Political Ambition. In Journal of Elections. Public Opinion, and Parties Online first. doi:10.1080/17457289.2019.1660354

Preece, J. R., Stoddard, O. B., and Fisher, R. (2016). Run, Jane, Run! Gendered Responses to Political Party Recruitment. Polit. Behav. 38, 561–577. doi:10.1007/s11109-015-9327-3

Pruysers, S., and Blais, J. (2018). A Little Encouragement Goes a (Not So) Long Way: An Experiment to Increase Political Ambition. J. Women, Polit. Pol. 39, 384–395. doi:10.1080/1554477x.2018.1475793

Pruysers, S., Blais, J., and Chen, P. G. (2019). Who Makes a Good Citizen? the Role of Personality. Personal. Individual Differences 146, 99–104. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2019.04.007

Raskin, R., and Terry, H. (1988). A Principal-Components Analysis of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory and Further Evidence of its Construct Validity. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 54, 890–902. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.5.890

Rauthmann, J. F., and Kolar, G. P. (2012). How “dark” Are the Dark Triad Traits? Examining the Perceived Darkness of Narcissism, Machiavellianism, and Psychopathy. Personal. Individual Differences 53, 884–889. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2012.06.020

Schneider, M. C., Holman, M. R., Diekman, A. B., and McAndrew, T. (2016). Power, Conflict, and Community: How Gendered Views of Political Power Influence Women's Political Ambition. Polit. Psychol. 37, 515–531. doi:10.1111/pops.12268

Sniderman, P. M. (1975). Personality and Political Behavior. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Vernon, P. A., Villani, V. C., Vickers, L. C., and Harris., J. A. (2008). A Behavioral Genetic Investigation of the Dark Triad and the Big 5. Personal. Individual Differences 44, 445–452. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2007.09.007

Keywords: political ambition, participation, personality, dark triad, light triad

Citation: Peterson RD and Palmer CL (2021) The Dark is Rising: Contrasting the Dark Triad and Light Triad on Measures of Political Ambition and Participation. Front. Polit. Sci. 3:657750. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.657750

Received: 23 January 2021; Accepted: 21 May 2021;

Published: 15 June 2021.

Edited by:

Scott Pruysers, Dalhousie University, CanadaReviewed by:

Scott Barry Kaufman, University of Pennsylvania, United StatesMike Medeiros, University of Amsterdam, Netherlands

Copyright © 2021 Peterson and Palmer. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Carl L. Palmer, Y2xwYWxtZUBpbHN0dS5lZHU=

Rolfe Daus Peterson1

Rolfe Daus Peterson1 Carl L. Palmer

Carl L. Palmer