- 1Department of Political Science, School of Social Sciences, University of Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany

- 2GESIS – Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences, Mannheim, Germany

Previous research underlines that a political system's adherence to principles of distributive and procedural justice stimulates citizens' political trust. Yet, most of what is known about the relationship between justice and political trust is derived from macro-level indicators of distributive and procedural justice, merely presuming that citizens connect a political system's adherence to justice principles to their trust in political authorities and institutions. Accordingly, we still lack a clear understanding of whether and how individual perceptions and evaluations of distributive and procedural justice influence citizens' political trust and how their impact might be conditioned by a political system's overall adherence to principles of justice. In addition, previous research has implicitly assumed that the link between justice principles and political trust operates identically for all major political authorities and institutions, disregarding the possibility that citizens evaluate representative and regulative authorities and institutions on the basis of different justice criteria. Against this background, the aims of the present study are (1) to investigate the impact of individual evaluations of distributive and procedural justice on citizens' political trust, (2) to analyze to what extent the effects of justice evaluations on political trust depend on political systems' overall adherence to principles of distributive and procedural justice, and (3) to assess whether and in which ways the influence of justice evaluations differs for trust in representative and regulative authorities and institutions. Our empirical analysis covering more than 30,000 respondents from 27 European countries based on data from the European Social Survey (ESS) and the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) project demonstrates that (1) more positive evaluations of distributive and procedural justice foster citizens' political trust, that (2) the impact of justice evaluations on political trust is amplified in political systems in which the overall adherence to justice principles is compromised, and that (3) different facets of distributive and procedural justice evaluations exert varying effects on citizens' trust in representative as compared to regulative authorities and institutions. These findings entail important implications with regard to the relation between justice and political trust and the general viability of modern democratic systems.

Introduction

Democracy is inextricably linked with principles of justice. In the long run, democratic systems will only thrive if they grant citizens equal access to the political process and provide societal outcomes that are considered just and fair by the citizenry. A failure to do so might compromise the legitimacy of a political system, with citizens feeling more dissatisfied with and detached from the political process, turning less trustful of politics, and being increasingly reluctant to voluntarily comply with the decisions of political authorities and institutions (Tyler, 2006; Anderson and Singer, 2008; Uslaner, 2011; Marien and Werner, 2019). For maintaining citizens' legitimacy beliefs and voluntary compliance—and to circumvent the more inefficient and costlier alternative of governing by coercion—adherence to basic principles of justice thus becomes imperative for any democratic system.

In line with these assertions, previous research highlights that violations of the basic principles relating to distributive and procedural justice exert a sizable detrimental effect on citizens' legitimacy beliefs, most notably their political trust. Theoretically, distortions of distributive and procedural justice have been argued to exist when societies exhibit high levels of income inequality or when practices of corruption, such as bribery or the abuse of public offices for private gains, are widespread (Anderson and Singer, 2008, 572–573; Uslaner, 2011; Hakhverdian and Mayne, 2012, 741). Empirically, a myriad of studies documents that citizens in countries plagued by rampant income inequality and corruption are less trustful of political authorities and institutions than their counterparts in more equal and cleaner countries (Anderson and Tverdova, 2003; Anderson and Singer, 2008; Krieckhaus et al., 2014; Zmerli and Castillo, 2015). These findings underline that a political system's adherence to principles of distributive and procedural justice matters for citizens' political trust and that violations thereof induce citizens to withhold their trust from political authorities and institutions.

In this study, we expand on the findings of previous research and examine in more detail to what extent and under what conditions distributive and procedural justice influence citizens' political trust. Our overarching aim is to establish a comprehensive picture of this relationship by simultaneously investigating the impact of individual-level perceptions and contextual-level indicators of distributive and procedural justice, as well as their interplay in bringing about citizens' political trust. In doing so, our study addresses three blind spots of previous research whose investigation promises to complement, enrich, and qualify the insights generated by research to date and thus to provide meaningful insights on the ways in which modern democracies can invigorate or undermine citizens' legitimacy beliefs.

First, we know surprisingly little on how individual perceptions and evaluations of distributive and procedural justice shape citizens' political trust. Most of what is known about the relationship between justice and political trust is derived from macro-level indicators capturing political systems' adherence to principles of justice, thus largely neglecting the role and relevance of individual justice evaluations (Citrin and Stoker, 2018, 60). However, if a political system's adherence to justice principles is supposed to affect citizens' political trust, it is through individual justice perceptions and evaluations, rendering an explicit analysis of said perceptions and evaluations indispensable. To date, only a few studies have investigated the impact of such evaluations on political trust. Yet, these studies have focused either on evaluations of distributive or procedural justice (cf. Linde, 2012; Loveless, 2013; Zmerli and Castillo, 2015; Marien and Werner, 2019), leaving the question on their relative weight in citizens' trust calculus unanswered. Therefore, the first goal of this study is to systematically investigate the impact of individual evaluations of both distributive and procedural justice on citizens' political trust.

Second, we know little about the context dependency of the relationship between justice evaluations and political trust across political systems that themselves differ in their actual adherence to principles of justice. Theoretically, living under unjust conditions may either amplify or attenuate the impact of individual justice evaluations on political trust (Goubin and Hooghe, 2020, 222–224). Empirically, Zmerli and Castillo (2015) show that individual justice evaluations are less influential for citizens' political trust in political systems that deviate more strongly from principles of distributive justice (see also Goubin and Hooghe, 2020), while other studies do not find such conditional effects across political systems (Loveless, 2013). However, these findings disregard evaluations of procedural justice and their possibly varying effects on political trust across political systems. Hence, the second goal of this study consists in analyzing the micro–macro conditionality pertaining to the impact of individual justice evaluations on political trust across political systems exhibiting a varying adherence to justice principles.

Third, we know little about how individual justice evaluations relate to citizens' trust in different authorities and institutions. Most existing studies rely on one-dimensional conceptions of political trust (Marien, 2017), implicitly assuming that the link between justice principles and political trust operates identically for all major political authorities and institutions of modern democracies. Yet, this assumption may be too simplified for the complexity of modern democratic systems in which different types of authorities and institutions—such as representative and regulative ones—are responsible for very different tasks and thus are likely to be evaluated on the basis of different justice criteria (Rothstein and Stolle, 2008; Schnaudt, 2019, 41–48). Accordingly, the third and last goal of this study is to assess whether and in which ways the influence of individual justice evaluations differs for trust in representative and regulative authorities and institutions.

The empirical analysis of this study is based on individual-level data from the ninth round of the European Social Survey (ESS) collected in 2018/19, combined with country-level data provided by the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) project (Coppedge et al., 2020). Overall, our combined data source allows for an encompassing empirical test of our theoretical propositions based on more than 30,000 respondents from a total of 27 European countries.

The remainder of this study is structured as follows. The Theory and Hypotheses section clarifies the conceptual underpinnings of justice and political trust, develops the main theoretical arguments, and specifies testable hypotheses on the impact of justice (evaluations) on citizens' political trust. The section on Data, Operationalization, and Methods discusses the data, operationalization, and methods applied in the empirical analysis. The Analysis section presents the main empirical findings. The concluding section summarizes the main insights generated by this study, discusses their broader implications, and outlines possible avenues for future research.

Theory and Hypotheses

Conceptual Framework

The main arguments presented in this study pertain to the question of whether and in which ways citizens' trust in political authorities and institutions responds to (evaluations of) general principles of justice. Before specifying the nature of this relationship in more detail, we clarify the conceptual foundations underlying the notions of political trust and justice (evaluations).

Political Trust: Concept and Dimensionality

The concept of political trust establishes one of the major building blocks within the broader scheme of political support (Easton, 1975). Located between citizens' endorsement of democratic principles on the one hand and evaluations of specific incumbents on the other, political trust is usually considered a mid-range indicator of political support directed at the core authorities and institutions of the political system (Norris, 1999). Political trust thus depicts a vertical relationship between citizens and those authorities and institutions that are responsible for the development and implementation of public policies and laws, such as political parties, the parliament, the government, public administrations, the courts, and the police, as well as individual officeholders within these institutions (Denters et al., 2007, 67; van der Meer and Zmerli, 2017).

Concerning its substance, political trust captures the extent to which political authorities and institutions—in both their code of conduct and their tangible actions—live up to citizens' expectations about legitimate and effective governance (Schnaudt, 2019, 37). Accordingly, political trust can be characterized as both relational and evaluative, conforming to more general understandings and formulae of trust in the form of “A trusts B to do X” (Hardin, 2000; van der Meer and Dekker, 2011, 96–97). In short, political trust “reflects evaluations of whether or not political authorities and institutions are performing in accordance with the normative expectations held by the public. Citizen expectations of how government should operate include, among other criteria, that it be fair, equitable, honest, efficient and responsive to society's needs” (Miller and Listhaug, 1990, 358).

An ongoing and still unresolved debate in the scholarly literature concerns the dimensionality of political trust (Fisher et al., 2010; Hooghe, 2011; Schnaudt, 2019). Two different perspectives can be distinguished that differ in their conclusions on whether or not citizens make a distinction between different (types of) political authorities and institutions when granting or withholding their political trust. The dominant, mostly empirically driven perspective suggests that citizens' trust in different authorities and institutions establishes a one-dimensional construct, rendering political trust a coherent and generalized attitude that is largely independent from the concrete authorities and institutions evaluated (Hooghe, 2011; Marien, 2011, 2017). The second perspective, usually relying on a mix of both theoretical arguments and empirical findings, contends that, when it comes to their political trust, citizens differentiate between representative and regulative types of authorities and institutions. According to this perspective, citizens distinguish between authorities and institutions that are responsible for the development of public policies and laws, such as politicians, political parties, and parliaments, and those that are concerned with the implementation and execution of public policies and laws, including civil servants, public administrations, the courts, and the police (Gabriel et al., 2002, 180–181; Denters et al., 2007; Schnaudt, 2013, 2019).

We take sides with the second perspective and rely on a two-dimensional conception of political trust differentiating between trust in representative and regulative authorities and institutions. From a theoretical perspective, previous studies have argued that representative and regulative authorities and institutions differ with regard to their respective functions and purpose, and therefore, citizens' expectations and evaluation criteria are likely to vary between both types of authorities and institutions (Seligman, 1997, 28–29; Sztompka, 1999, 55; Rothstein and Teorell, 2008, 175–177; Schnaudt, 2019, 45–46). In addition, there are empirical reasons that question the appropriateness and dominant use of one-dimensional conceptions in previous research. First, the empirical results on the one-dimensionality of political trust presented in previous studies oftentimes hint at deviations from a clear one-dimensional structure (Rohrschneider and Schmitt-Beck, 2002, 57, fn. 25; Zmerli, 2004, 233; Zmerli et al., 2007, 64, fn. 11). Second, one-dimensional scales of political trust usually account for only a small proportion of the variance in citizens' trust in regulative authorities and institutions (Marien, 2011, 18–20; Schnaudt, 2019, 47; Schnaudt, 2020a, 229–230). Hence, they leave it open to debate whether we can meaningfully speak of political trust as a one-dimensional construct if major regulative authorities and institutions of modern democracies are not part of it.

Overall, there are thus convincing theoretical and empirical arguments that render a distinction between these two types of political trust a promising avenue for generating new insights on the role and relevance of political trust in modern democracies. In the present study, relying on a two-dimensional conception of political trust allows us to empirically explore and detect possibly varying effects of (evaluations of) justice on citizens' trust in representative and regulative authorities and institutions.

Justice (Evaluations): Conceptual Models

Justice research distinguishes two broad conceptions according to which the allocation of resources and burdens in a society can be characterized as just and fair (Tyler and Lind, 1992, 121–123). Distributive justice pertains to the fair distribution of resources and opportunities within society. As such, it refers to the distribution of material goods, such as income or social benefits, as well as to questions about equality of opportunity with regard to individuals' long-term life chances, including access to education, the job market, or health care. When it comes to evaluations of distributive justice, individuals compare the actual allocation of resources and opportunities with an allocation they would perceive to be fair1. Based on the results of this comparison, they either evaluate a distribution as fair or identify an over- or under-compensation (Jasso et al., 2016).

Procedural justice takes a step back and focuses on the quality of the process by which a distributive decision is reached (Abdelzadeh et al., 2015, 255–257; Grimes, 2017, 257–259). Instrumental models of procedural justice define procedural or structural conditions of fair decision-making. One of the most fundamental conditions in these models is a person's control over the decision-making process or the actual decisions made (Thibaut and Walker, 1975). In addition, Leventhal (1980) proposes six justice rules for evaluating the fairness of allocation processes. An allocative procedure is fair if it is consistently applied across persons and over time, precludes bias or self-interest, and is based on accurate and comprehensive information. Furthermore, fair procedures should provide the opportunity to correct decisions, reflect the interests and values of all affected subgroups, and respect moral and ethical values. Relational models of procedural justice consider fair processes as a function of the quality of the relationship between individuals and authorities. Here, procedures are evaluated using three criteria: whether they convey a person's positive standing in a group, whether they treat a person politely and respectfully, and whether they imply neutrality, i.e., a lack of bias and discrimination against subgroups (Tyler and Lind, 1992). Individuals' evaluations of procedural justice ultimately reflect the extent to which they perceive political processes to correspond with the above criteria.

Next to the distinction between distributive and procedural justice as dominant types, the scope of justice conceptions is relevant. Here, the literature has distinguished between egocentric (self-regarding) and sociotropic (other-regarding) justice attitudes (Jasso, 1999; Kluegel and Mason, 2004). Both differ with regard to the main reference points of justice evaluations, with egocentric evaluations being directed toward the personal situation of an individual and sociotropic evaluations aimed at the society and societal conditions as a whole.

In summary, the present study relies on a multi-dimensional conceptualization of justice. At the country level, we distinguish between a political system's actual adherence to principles of distributive and procedural justice, such as providing citizens with equal access to basic resources and opportunities or avoiding corrupt practices as part of governing, respectively. At the individual level, we focus on citizens' perceptions and differentiate between egocentric and sociotropic evaluations of distributive and procedural justice.

Political Trust and Distributive and Procedural Justice

The explicit references to citizens' expectations about legitimate and efficient governance as well as to the evaluation criteria “fairness” and “equitability” in definitions of political trust evidently point to a relationship between matters of justice and citizens' trust in political authorities and institutions. With their decisions on and implementation of policies related to the economy and social welfare, political authorities and institutions do not only determine overall levels of distributive and procedural justice in a polity. Rather, they also directly influence what citizens may think about the realization of justice in their country (Zmerli and Castillo, 2015, 182). Therefore, it is not only plausible that citizens attribute responsibility to political authorities and institutions for matters related to justice (Zmerli and Castillo, 2015, 190; Goubin and Hooghe, 2020, 220) but also that their political trust is a function of both (1) their individual justice perceptions and evaluations as well as (2) their political system's actual adherence to principles of justice.

Political Trust and Individual-Level Justice Perceptions

Although matters of performance, process, and probity as core elements of “master P” feature center stage in most political explanations of political trust (Hetherington and Rudolph, 2015, 34–35; Citrin and Stoker, 2018, 58–60), perceptions and evaluations of distributive and procedural justice as important antecedents of political trust have so far only played a subordinate or implicit role in the scholarly debate. The underlying premise of explanations revolving around “master P” is that individuals' political trust responds to whether political authorities and institutions succeed or “fail to meet expected goals or follow prescribed norms” (Citrin and Stoker, 2018, 57). As such, evaluations of distributive and procedural justice can be generally classified into the same category as other evaluations pertaining to the performance of the political system, most notably evaluations of economic matters (Weatherford, 1984). What is more, evaluations of distributive and in particular procedural justice also bear an apparent relation to process and probity. Previous studies investigating the impact of process and probity focused on the role of procedures, scandals, and corruption in shaping political trust (Hibbing and Theiss-Morse, 2001; Bowler and Karp, 2004), all of which are phenomena that matter for and should be reflected in evaluations of distributive and procedural justice. However, as Citrin and Stoker (2018, 60) note, “since scholars have not [yet] introduced perceptions of process into the major national surveys, we know less about the topic than we should.” Accordingly, while individuals' perceptions of distributive and procedural justice are generally compatible with existing explanations of political trust highlighting performance, process, and probity, encompassing (cross-national) evidence on this relationship is still lacking to date.

What then is the mechanism linking individual justice perceptions to political trust? In this regard, the overarching premise is that citizens assess the extent to which political authorities and institutions live up to citizens' justice expectations and subsequently decide on whether or not these merit their trust. When it comes to evaluations of distributive justice, this implies that individuals compare the actual allocation of resources and opportunities in society with an allocation they personally would perceive to be fair (Jasso et al., 2016). For evaluations of procedural justice, the same holds true with regard to the actual quality and fairness of the political processes that lead to the allocation of resources and opportunities. Ultimately, citizens will grant or withhold their trust in political authorities and institutions depending on whether or not they perceive the actual resource allocation and quality of political processes to correspond with their personal expectations about distributive and procedural justice (Tyler et al., 1985, 702–703; Miller and Listhaug, 1999, 213–214). If expectations and perceptions align, citizens will extend their trust to political authorities and institutions; if perceptions fail to meet expectations, citizens will withhold their political trust (cf. Kimball and Patterson, 1997; Schnaudt, 2019, 118–121). A crucial precondition underlying this mechanism is that citizens attribute responsibility for the perceived realization of distributive and procedural justice in their country to the workings of political authorities and institutions (Zmerli and Castillo, 2015, 190; Goubin and Hooghe, 2020, 220).

In line with the preceding assertions, previous studies show that citizens with more positive evaluations of distributive justice exert higher levels of political trust (Loveless, 2013, 484; Zmerli and Castillo, 2015, 188) and that particularly sociotropic evaluations matter in this regard (Kluegel and Mason, 2004, 825). With regard to evaluations of procedural justice, previous empirical findings indicate that citizens are more likely to endorse political leaders and place greater trust in legal authorities or governmental institutions if they perceive the procedures used to allocate resources and burdens to be fair (Tyler et al., 1985, 1989; Linde, 2012; Marien and Werner, 2019). In her comprehensive review and discussion of existing studies investigating the impact of procedural justice evaluations on political trust, Grimes (2017, 261) thus reaches the conclusion that there is “a wealth of evidence that perceptions of procedural fairness in decision-making processes are linked to higher levels of political trust.”

An important caveat concerns the possibility of reversed causality. While there are convincing arguments to expect that political trust responds to justice evaluations, it is conceivable that citizens' trust in political authorities and institutions, at least to some extent, influences perceptions and evaluations of justice (Grimes, 2017, 261–262). While such concerns can hardly be tackled in cross-sectional studies, earlier research relying on panel data shows that the relationship either runs from justice evaluations to political trust or that there is a reciprocal relationship (Tyler et al., 1989; Grimes, 2006; Tyler, 2006). Most importantly, then, none of these earlier findings invalidates our presumed causal order running from justice evaluations to political trust.

While existing research thus confirms the relevance of individual justice perceptions as antecedents of political trust, previous studies have usually focused either on evaluations of distributive or procedural justice, leaving open the question about their relative importance in shaping political trust. What is more, many studies have been restricted to single countries, neglecting a more general cross-national perspective. While Zmerli and Castillo (2015) as well as Loveless (2013) and Kluegel and Mason (2004) have provided first evidence for a broader set of Latin American and post-communist countries, respectively, encompassing evidence for European countries spanning both distributive and procedural justice evaluations is missing. We attempt to fill this gap by examining the impact of different aspects of individual perceptions of justice, considering both individuals' evaluations of distributive decisions and the fairness of political processes across a broad range of European countries. To this end, we test the following hypothesis:

H1: The more positive citizens' evaluations of distributive and procedural justice, the higher their political trust.

Political Trust and Contextual-Level Justice

While citizens' individual perceptions and evaluations of distributive and procedural justice may be systematically related to their political trust, they do not necessarily have to reflect the actual realization of distributive and procedural justice in a given political system. To arrive at an encompassing picture on the relationship between justice and political trust, analyzing the impact of contextual-level distributive and procedural justice (next to individual-level perceptions thereof) thus seems indispensable. In the following, we argue that citizens will be more trustful in systems that adhere more strongly to principles of distributive and procedural justice.

With regard to distributive justice, political authorities and institutions influence the distribution and allocation of resources in society in manifold ways: “through spending on public services, public or subsidized jobs, by setting and enforcing wage standards, or through implementing wage policies and curbing rent-seeking practices” (Goubin and Hooghe, 2020, 220). With their policy decisions on economic matters and public welfare, political authorities and institutions exert a direct impact on citizens' daily lives, most notably by determining how much taxes citizens have to pay or which social benefits they are entitled to. In addition to this direct influence on the distribution of common resources, political authorities and institutions also determine the opportunity structure within society and, by implication, the actual realization of equality of opportunity. For example, the decisions taken by political authorities and institutions on the shape of the education system to a large extent determine the chances of citizens to acquire the education they aspire and, in the long run, to get the jobs they want. These arguments suggest that, depending on the exact content and shape of economic, welfare, or education policies developed and implemented by political authorities and institutions, these will have distinct implications for the allocation of resources and the realization of equality of opportunity within a given society. The actual distribution of resources and equality of opportunity, in turn, can be expected to influence citizens' political trust, with citizens living in systems that adhere more strongly to principles of distributive justice being more trustful.

Similar arguments can be advanced for the impact of procedural justice. In line with one of the distinctive features of procedural justice stating that individuals should exert control over decision-making processes or have the opportunity to influence decisions (Thibaut and Walker, 1975), here as well political authorities and institutions have the means to determine the extent to which citizens feel included in the political process. Specifically, by designing transparent decision-making processes, providing information and justification about decisions, and granting citizens the chance to participate in the political process, political authorities and institutions can actively adhere to principles of procedural justice (Tyler et al., 1989; Tyler, 2006; Rothstein and Teorell, 2008). Similarly, also in the implementation stage of political decisions, political authorities and institutions can abide to principles of procedural justice by treating everyone in the same, impartial way (Rothstein and Stolle, 2003, 2008; Linde, 2012). Depending on the extent to which political systems implement fair procedures, citizens can be expected to grant or withhold their political trust, with citizens living in systems that abide more strongly to principles of procedural justice exhibiting higher levels of political trust.

Previous studies analyzing the impact of contextual-level distributive and procedural justice on political trust and related attitudes have mostly focused on income inequality and corruption as respective indicators. While the empirical picture painted by these studies hints at a rather clear pattern with the level of a country's income inequality and corruption impacting negatively on citizens' trust in political authorities and institutions (Anderson and Tverdova, 2003; Anderson and Singer, 2008; Loveless, 2013; Zmerli and Castillo, 2015), a simultaneous assessment of both country-level distributive and procedural justice is outstanding. What is more, those studies focusing on income inequality have missed important facets of distributive justice that extend beyond the distribution of material goods, most notably facets related to the realization of equality of opportunity in a given country. In this study, we address these issues by simultaneously investigating the impact of a more comprehensive contextual-level indicator of distributive justice capturing the equal distribution of resources and opportunities as well as corruption (procedural justice) on political trust. The following hypothesis concerning the contextual-level impact of political systems' actual adherence to principles of distributive and procedural justice on political trust will be tested:

H2: The stronger a political system's adherence to principles of distributive and procedural justice, the higher citizens' political trust.

Political Trust and the Micro–Macro Conditionality of Justice (Perceptions)

So far, we have been mainly concerned with direct effects of distributive and procedural justice on trust in political authorities and institutions, including both individual- and contextual-level effects. Yet, to investigate in full detail in which ways distributive and procedural justice are connected to political trust, it is important to establish explicit links between individual-level perceptions and evaluations and the actual realization of distributive and procedural justice principles across political systems (Grimes, 2017, 262). In the following, we argue that citizens' individual justice evaluations interact with a political system's actual adherence to distributive and procedural justice in bringing about citizens' political trust (cf. Krieckhaus et al., 2014; Zmerli and Castillo, 2015; Goubin and Hooghe, 2020). Specifically, we contend that a political system's adherence to (or violation of) principles of distributive and procedural justice conditions the impact of individual justice evaluations on political trust. We distinguish two opposing kinds of such conditioning effects which themselves can be traced back to two different theoretical perspectives: a self-interest, utilitarian perspective and a system justification perspective (see also Goubin and Hooghe, 2020, 222–224). The main difference between both perspectives pertains to the question of whether or not citizens attribute responsibility for the state of justice in their country to political authorities and institutions.

From a self-interest, utilitarian perspective, it can be expected that citizens' evaluations of justice are more decisive in determining political trust in countries where the actual adherence to justice principles is compromised. The underlying argument is the following: Political systems that are hampered by a shortage of distributive and procedural justice are likely to exacerbate existing differences between the haves and have-nots, rendering citizens' evaluations of justice more salient and, consequently, more influential in their political trust calculus. The assumption here is that citizens link the actual levels of distributive and procedural justice in their country to the workings of political authorities and institutions. For political systems characterized by an unequal distribution of basic resources and opportunities or rampant corruption, this implies that those who evaluate the prevalent conditions as unfair (i.e., those likely to be disadvantaged by injustices) are particularly critical and distrustful of political authorities and institutions (cf. Hetherington and Rudolph, 2008). By contrast, those who perceive such conditions as fair (i.e., the likely beneficiaries of injustices) can be expected to be benevolent and trustful toward authorities and institutions (Krieckhaus et al., 2014; Goubin and Hooghe, 2020, 223). As an observable implication of these arguments, the difference in political trust levels between citizens with positive and those with negative justice evaluations should be more pronounced in political systems that deviate more strongly from principles of distributive and procedural justice (i.e., systems with a more unequal distribution of resources and higher levels of corruption). We refer to this as the amplification hypothesis.

H3a: The impact of citizens' justice evaluations on political trust is amplified in political systems that deviate more strongly from principles of distributive and procedural justice.

Following the system justification theory (Jost, 2019), individual evaluations of justice are expected to matter less for citizens' political trust in political systems where the actual realization of distributive and procedural justice is constrained. The underlying premise for this expectation is that all citizens exhibit a general preference for living in a just political system, irrespective of their socioeconomic status or social position (Jost et al., 2003). When actual conditions evidently deviate from this ideal, citizens engage in system justification, implying that they “develop coping strategies, either actively, or subconsciously, to deal with this situation. This especially occurs in situations where […] injustices are endemic and when citizens feel powerless to change the system” (Goubin and Hooghe, 2020, 223). Such coping strategies primarily aim to reduce citizens' cognitive dissonances (Jost, 2019) that result from living under unjust conditions, but wanting to live in a just and fair environment. One possible coping strategy consists in shifting the object of blame or responsibility attribution. For example, citizens may refer to principles of individual responsibility rather than blaming the political system and its authorities and institutions for their personal circumstances or the overall state of justice in their country (cf. Zmerli and Castillo, 2015, 190; Goubin and Hooghe, 2020, 244). With this decoupling of justice concerns from the workings of political authorities and institutions, also the general link between justice and political trust is weakened. As a consequence, citizens' evaluations of distributive and procedural justice can be expected to play a less decisive role in their political trust calculus (see also Goubin, 2020, 272). Following from the preceding discussion, the impact of justice evaluations on political trust should be weaker in systems that are hampered by low levels of actual distributive and procedural justice. We refer to this as the attenuation hypothesis.

H3b: The impact of citizens' justice evaluations on political trust is attenuated in political systems that deviate more strongly from principles of distributive and procedural justice.

Empirical evidence relating to the preceding discussion is restricted to studies using income inequality as a contextual indicator of distributive justice. Overall, the results of these studies point in the direction of the attenuation hypothesis, showing that the influence of citizens' socioeconomic status and evaluations of distributive (income) justice on political trust are weaker in countries with higher levels of income inequality (Krieckhaus et al., 2014; Zmerli and Castillo, 2015; Goubin and Hooghe, 2020). In this study, we provide a more encompassing test, focusing on the conditional interplay of individual citizens' evaluations of and political systems' actual levels of both distributive and procedural justice.

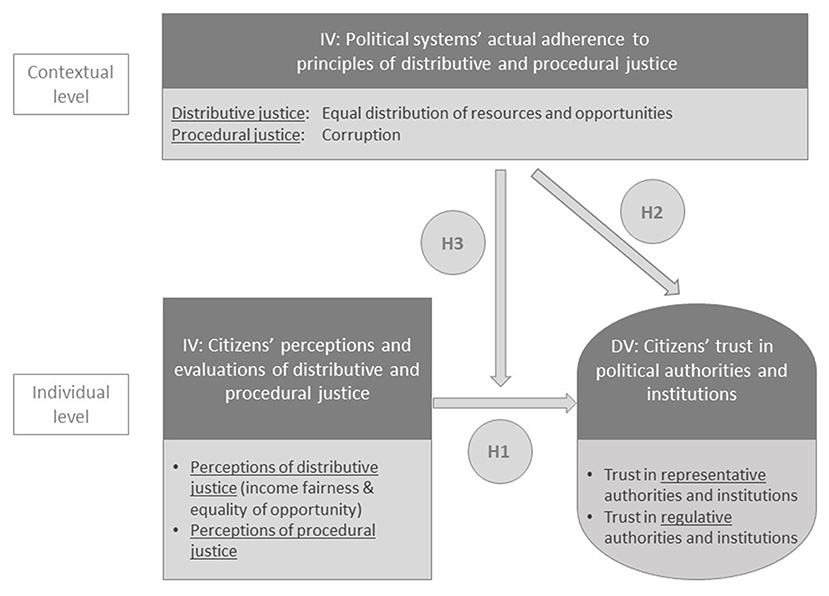

Figure 1 provides a summary of our research design and hypotheses under investigation. At the individual level, we expect citizens with more positive evaluations of distributive and procedural justice to be more trustful of political authorities and institutions (H1). Concerning contextual-level effects of distributive and procedural justice, we expect citizens to exhibit higher levels of political trust in political systems that allocate resources and opportunities equally and that rely on fair procedures in the political process (H2). Finally, we expect the impact of individual justice evaluations on citizens' political trust to vary across political systems with different levels of actual distributive and procedural justice (H3). According to the amplification hypothesis, justice evaluations will be more influential in systems that exhibit lower levels of actual distributive and procedural justice (H3a). Following the attenuation hypothesis, the effects of justice evaluations will be weaker in systems with lower levels of actual distributive and procedural justice (H3b).

Data, Operationalization, and Methods

Data

For the empirical test of our hypotheses, we require data covering both citizens' political trust and their justice evaluations at the individual level. The European Social Survey (ESS) contains a standard series of questions on political trust comprising representative and regulative authorities and institutions (for a general overview of the ESS, see Schnaudt et al., 2014). In addition, the ninth round of the ESS, 2018/19 implemented a specific thematic module on “Justice and fairness,” which provides a topical and comprehensive data basis for the research questions at hand (ESS, 2018). The special module offers detailed measurements on individuals' perceptions of distributive justice both in terms of income inequality and equal opportunities in education or employment. Furthermore, it includes individuals' evaluations of procedural justice in the political sphere. For testing our hypotheses involving contextual-level indicators of justice, we complement the ESS individual-level data with country-level data compiled by the V-Dem project providing information on the extent to which political systems themselves adhere to principles of distributive and procedural justice (Coppedge et al., 2020).

Political Trust

To measure our dependent variable political trust, the ESS provides several items asking respondents how much they personally trust five different political authorities and institutions of the national political system. Respondents can indicate their level of trust on an 11-point scale ranging from “0 no trust at all” to “10 complete trust.” The specific authorities and institutions covered are the following: politicians, political parties, the national parliament, courts, and the police. In line with our conceptual discussion on the distinction between representative and regulative authorities and institutions, we construct two additive indices. We operationalize trust in representative authorities and institutions with an index of respondents' trust in politicians, political parties, and the national parliament (Cronbach's alpha = 0.91). As the ESS provides only two items for measuring trust in regulative authorities and institutions, we create an index of trust in the courts and the police (Cronbach's alpha = 0.80)2. For both indices, we retain the original scale range from 0 to 10, with higher values representing higher levels of political trust. These two indices serve as dependent variables in our empirical analysis.

Evaluations of Justice

We employ a differentiated measurement approach to capture individual perceptions and evaluations of justice, aiming to distinguish between different facets of distributive and procedural justice as well as egocentric and sociotropic justice evaluations (Tyler and Lind, 1992; Jasso, 1999).

Evaluations of Distributive Justice

For measuring evaluations of distributive justice, we make use of several items referring to (1) income fairness and (2) equality of opportunity with regard to education and employment chances. Accordingly, our analysis contains a question on the fairness of respondent's own income: “Would you say your net pay/net income from pensions/net income from social benefits and/or grants is unfairly low, fair, or unfairly high?” as well as a question on the income fairness of one's general social group: “In general, do you think the pay/incomes from pensions of people who work/worked in the same occupation as you/incomes from social benefits of people receiving social benefits in [country] is unfairly low, fair, or unfairly high?.” Respondents could evaluate these questions using a nine-point scale, ranging from “−4 low, extremely unfair” over “0 fair” to “4 high, extremely unfair.” To account for the non-linearity in the measurement scale with more unfair evaluations at both extremes, we construct a categorical variable with three categories combining (1) answers on the negative side of the original scale (“unfairly low incomes” comprising values −4 to −1), (2) answers on the positive side of the original scale (“unfairly high incomes” comprising values 1 to 4), and (3) answers at the mid-point of the original scale (“fair incomes”).

For measuring egocentric evaluations of equality of opportunity with regard to education and the job market, we rely on the following two items: “Compared to other people in [country], I have had a fair chance of achieving the level of education I was seeking” and “… I would have a fair chance of getting the job I was seeking.” For sociotropic evaluations, we rely on the following two items: “Overall, everyone in [country] has a fair chance of achieving the level of education they seek” and “… has a fair chance of getting the jobs they seek.” For these four items, respondents could provide their answers using an 11-point scale ranging from “0 does not apply at all” to “10 applies completely.” Since the two respective items for egocentric and sociotropic evaluations of equality of opportunity are strongly correlated (r = 0.51 and 0.60, respectively), we combine them into two indices.

Evaluations of Procedural Justice

To operationalize evaluations of procedural justice, we rely on an index of five items capturing different criteria fundamental to a fair political process, including aspects of both instrumental and relational models of procedural justice. First, respondents are asked about the fairness of political procedures: “How much would you say that the political system in [country] ensures that everyone has a fair chance to participate in politics?” Furthermore, respondents are asked to assess the impartiality of political procedures by evaluating “How much the government in [country] takes into account all citizens' interest?” A third criteria concerns the question of having a voice in political procedures, which is measured by two items: “How much would you say the political system in [country] allows people like you to have a say in what the government does?” and “How much would you say that the political system in [country] allows people like you to have an influence on politics?” Fourth, the perception of transparency in political procedures is captured by asking respondents: “How much would you say that decisions in [country] politics are transparent, meaning that everyone can see how they were made?” Respondents could evaluate each of these questions using a five-point scale, ranging from “1 not at all” to “5 a great deal.” A factor analysis of the five items yields a clear one-dimensional solution. Based on these results, we construct an additive index of procedural justice (Cronbach's alpha = 0.84), with higher values indicating more positive evaluations of procedural justice. Given the question wording of the five items as well as the substantial correlations between them, a distinction between egocentric and sociotropic evaluations of procedural justice cannot be established3.

Contextual-Level Indicators of Justice

In addition to citizens' evaluations of justice, we rely on country-level indicators measuring a political system's actual adherence to principles of distributive and procedural justice. To capture adherence to distributive justice, we rely on a composite index measuring the equal distribution of resources in a country provided by the V-Dem project (Coppedge et al., 2020). The index combines information on the equal provision of and access to high-quality basic education and healthcare, the amount of public goods spending, and the universal provision of welfare services to all citizens. In comparison to previous studies that mostly relied on income inequality (Kluegel and Mason, 2004; Loveless, 2013; Zmerli and Castillo, 2015, 179), our study thus makes use of a more encompassing operationalization that extends beyond purely economic facets of distributive justice. For measuring a political system's actual adherence to procedural justice, our analysis relies on the level of corruption in order to capture deviations from fair and equal treatment and more general violations of the impartiality principle in a country (Rothstein and Teorell, 2008). Evidently, systemic corruption is likely to affect the distribution of resources and opportunities within society as well and thus could also be considered an indicator of distributive justice. Yet, corruption is tied to distributive justice via its deteriorating impact on the quality of procedures only. Corrupt practices such as bribery and embezzlement are the epitomes of bias and self-interest and the exact opposites of procedural ideals such as neutrality, impartiality, and respect for moral and ethical values. It is through such practices that unfair allocations of resources and opportunities might be incurred. Therefore, we treat corruption as a procedural feature that, by diminishing the quality of how distributive decisions are reached, may affect the fair allocation of resources and opportunities within society. Drawing again on the V-Dem project, we use as an indicator the political corruption index covering bribery, embezzlement, and theft in different branches of the political process, including executive, legislative, judicial, and public sector corruption (Coppedge et al., 2020)4. Both indices for distributive and procedural justice are based on country-expert codings referring to the year 2018 and range from 0 to 1, with higher values coded as representing more unequal resource distributions and higher levels of corruption, respectively5.

Control Variables

To reliably estimate the effects of justice (evaluations) on political trust, we include several control variables. At the individual level, respondents' socioeconomic status can be expected to influence both their justice evaluations and political trust (Goubin and Hooghe, 2020). Therefore, we include respondents' age, gender, education, subjective assessment of their household income, as well as satisfaction with the economy. Level of education is measured as the number of years completed in full-time education. Subjective income is measured with the question: “Which of the descriptions on this card comes closest to how you feel about your household's income nowadays?” Respondents could give their answer on a scale from “1 living comfortably on present income” to “4 finding it very difficult on present income.” Satisfaction with the economy is measured on an 11-point scale ranging from “0 extremely dissatisfied” to “10 extremely satisfied.” At the country-level, the overall macroeconomic performance of a country has been shown to be an important antecedent of individuals' political trust (van Erkel and van der Meer, 2016) and can be expected to influence a country's overall realization of distributive and procedural justice principles as well. Therefore, we control for real gross domestic product per capita (GDP per capita in 100k Euro) in 2018 (Eurostat, 2020).

Methods

We follow a factor-centric research design that aims to identify the specific impact of distributive and procedural justice rather than providing the most encompassing explanation of political trust possible (Gschwend and Schimmelfennig, 2007). Given the nested structure of our data combining information on both individuals and countries, our empirical analysis relies on hierarchical linear regression models. We rescale all continuous individual-level variables to range from 0 to 1. For the estimation of cross-level interactions, we group-mean center all individual-level variables and grand-mean center all country-level variables. Across all models presented, we rely on the identical number of cases to allow for straightforward comparisons across models and findings. Overall, our analysis includes 34,335 respondents from 27 European countries6.

Analysis

Our empirical analysis is structured along two consecutive steps. In the first step, we present the empirical findings pertaining to the direct effects of distributive and procedural justice on citizens' trust in representative and regulative authorities and institutions (H1 and H2). In the second step, we outline our findings on the conditional impact of justice evaluations on political trust as a function of political systems' actual adherence to justice principles (H3a/b).

Direct Effects of Distributive and Procedural Justice (Evaluations)

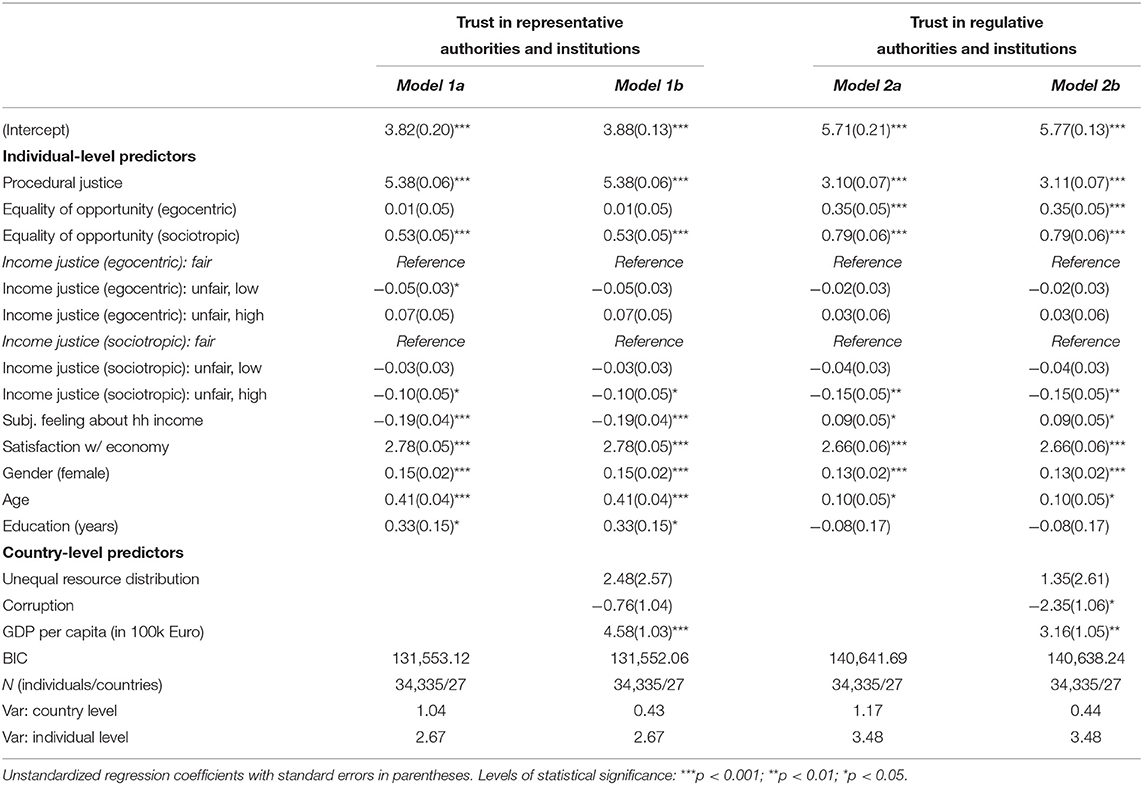

Table 1 summarizes the main findings pertaining to the impact of justice (evaluations) on citizens' trust in representative and regulative authorities and institutions. Models 1a and 1b present the results for trust in representative authorities and institutions and models 2a and 2b for trust in regulative authorities and institutions.

Models 1a and 2a assess the impact of citizens' evaluations of distributive and procedural justice (H1). As can be seen, more positive evaluations of procedural justice as well as more positive sociotropic evaluations of equality of opportunity are positively related to trust in both types of authorities and institutions. Egocentric evaluations of equality of opportunity are positively related to trust in regulative authorities and institutions only. For egocentric evaluations of income fairness, it is evident that those who consider their own incomes as unfairly low are less trustful of representative authorities and institutions, while those considering their incomes as unfairly high do not differ in their political trust from those who feel that their incomes are fair. In comparison, egocentric evaluations of income fairness are unrelated to trust in regulative authorities and institutions. Finally, for evaluations of sociotropic income fairness, a different picture emerges. Here, the results indicate that those who feel that the political system allows whole occupational status groups to be overcompensated with unfairly high incomes are less trustful than citizens who perceive the incomes of their own occupational group to be fair. This effect generalizes to both representative and regulative authorities and institutions. In contrast, those who feel that their occupational status group is undercompensated with unfairly low incomes do not differ in their political trust from those who consider such incomes as fair. Overall, the results presented in models 1a and 2a generally confirm that more positive evaluations of distributive and procedural justice go hand in hand with higher levels of political trust, thus lending support to H1.

At the same time, our results point to some important qualifications of this general relationship. First, the effects of procedural justice evaluations outweigh those of distributive justice. This holds true for both trust in representative and regulative authorities and institutions7. Second, sociotropic evaluations of justice appear to be more relevant for political trust than egocentric ones, exerting largely consistent effects on trust in representative and regulative types of authorities and institutions. Third, evaluations pertaining to equality of opportunity (both egocentric and sociotropic) play a relatively stronger role with regard to trust in regulative as compared to representative authorities and institutions. Fourth and last, egocentric evaluations related to the fairness of personal incomes are relevant for trust in representative authorities and institutions, while being largely detached from trust in regulative ones.

Turning to the results for models 1b and 2b, we have a closer look at the contextual effects of a political system's actual adherence to distributive and procedural justice on citizens' political trust (H2)8. As can be seen in model 1b, neither the distribution of basic resources and opportunities nor corruption as indicators of distributive and procedural justice exert a statistically significant effect on citizens' trust in representative authorities and institutions (while simultaneously controlling for individual evaluations of justice and macroeconomic performance, i.e., GDP per capita). To inspect these findings further, models 3–5 in the Supplementary Table 1 provide results for incremental regression models estimating the effects of resource distribution and corruption while not controlling for GDP per capita. The findings indicate that both an unequal resource distribution (model 3) and corruption (model 4) exert the expected negative effects on political trust, with the latter being more relevant than the former (model 5). Overall, the results presented in model 1b in Table 1 thus suggest that, ultimately, macroeconomic performance seems to matter more for trust in representative authorities and institutions than principles of both distributive and procedural justice. Therefore, with regard to trust in representative authorities and institutions, H2 has to be rejected.

Model 2b in Table 1 presents the corresponding findings for trust in regulative authorities and institutions. The main difference compared to the preceding results pertains to the statistically significant negative impact of country-level corruption that persists even after controlling for GDP per capita. This observation not only suggests that for trust in regulative authorities and institutions, a political system's actual adherence to procedural justice is more relevant than its adherence to distributive justice but also that the realization of principles of procedural justice in a given country matters beyond and independently of a country's macroeconomic performance9. Accordingly, with regard to trust in regulative authorities and institutions, H2 receives empirical support for the impact of a political system's procedural justice, while it has to be rejected for the impact of a system's distributive justice.

Conditional Effects of Distributive and Procedural Justice Evaluations

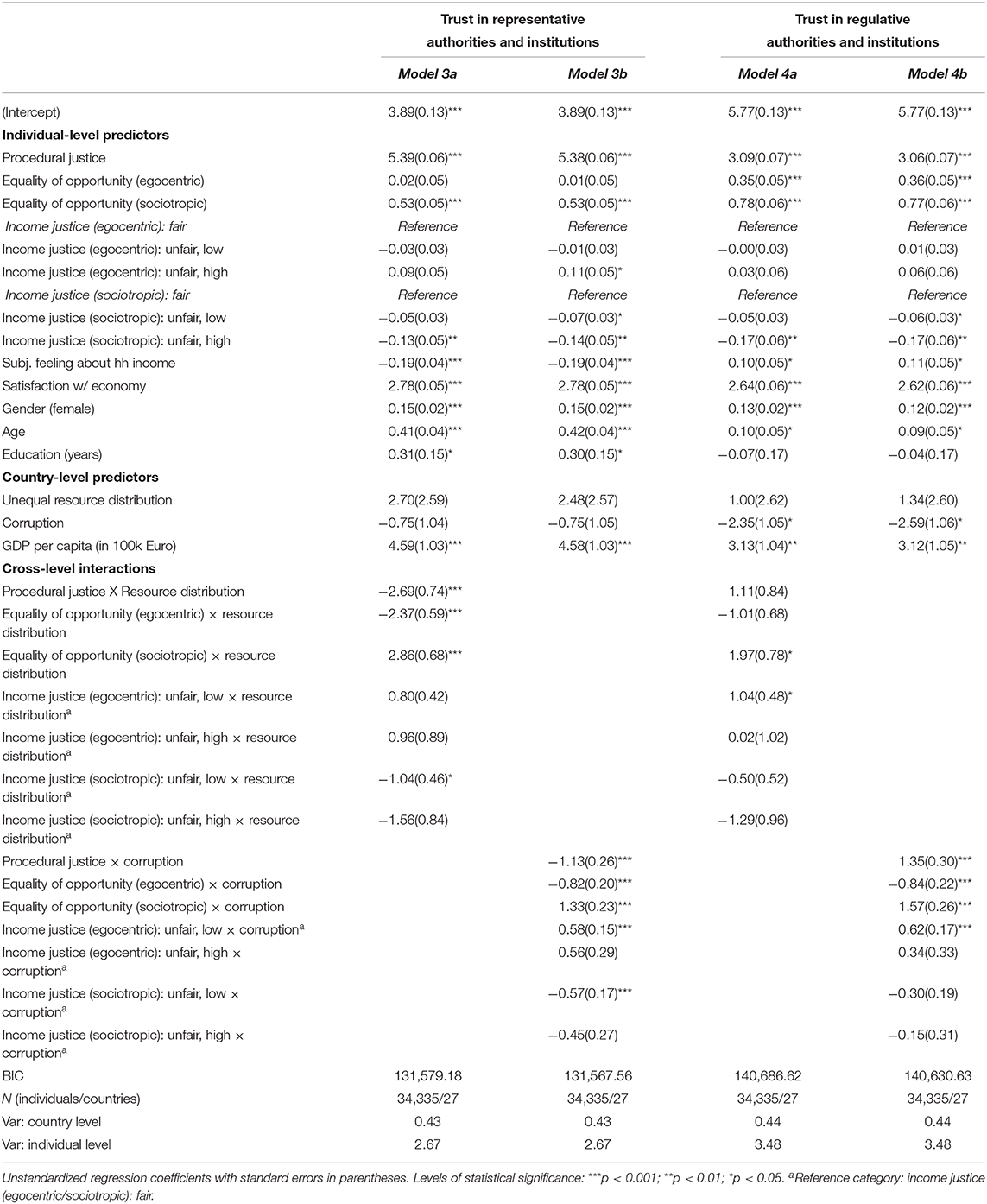

In the second step of our analysis, we turn to the investigation of the micro–macro conditionality of justice evaluations as stated in the amplification (H3a) and attenuation hypotheses (H3b). Given the relatively high number of 10 cross-level interactions to be estimated (five individual-level justice evaluations × two contextual-level justice indicators) with only 27 second-level units available, we opt for estimating separate models including (1) interactions between individual justice evaluations and country-level distributive justice (resource distribution) and (2) interactions between individual justice evaluations and country-level procedural justice (corruption)10.

Table 2 presents the results of our analysis. Models 3a and 3b pertain to trust in representative authorities and institutions, whereas models 4a and 4b refer to trust in regulative authorities and institutions as dependent variables.

At first glance, two general observations come to light. First, the direction and pattern of the interaction effects observed are almost identical for trust in representative and regulative authorities and institutions. Looking at the statistical significance of the interaction effects, however, it is evident that conditional effects of individual justice evaluations are overall more relevant with regard to trust in representative than in regulative authorities and institutions. Second, for each type of political trust, the pattern and direction of the interaction effects observed are identical for resource distribution and corruption as the two contextual-level moderating factors representing distributive and procedural justice, respectively. When also considering the statistical significance of the cross-level interactions, it is evident that conditional effects of individual justice evaluations are overall more prevalent with regard to corruption rather than resource distribution as moderating factors.

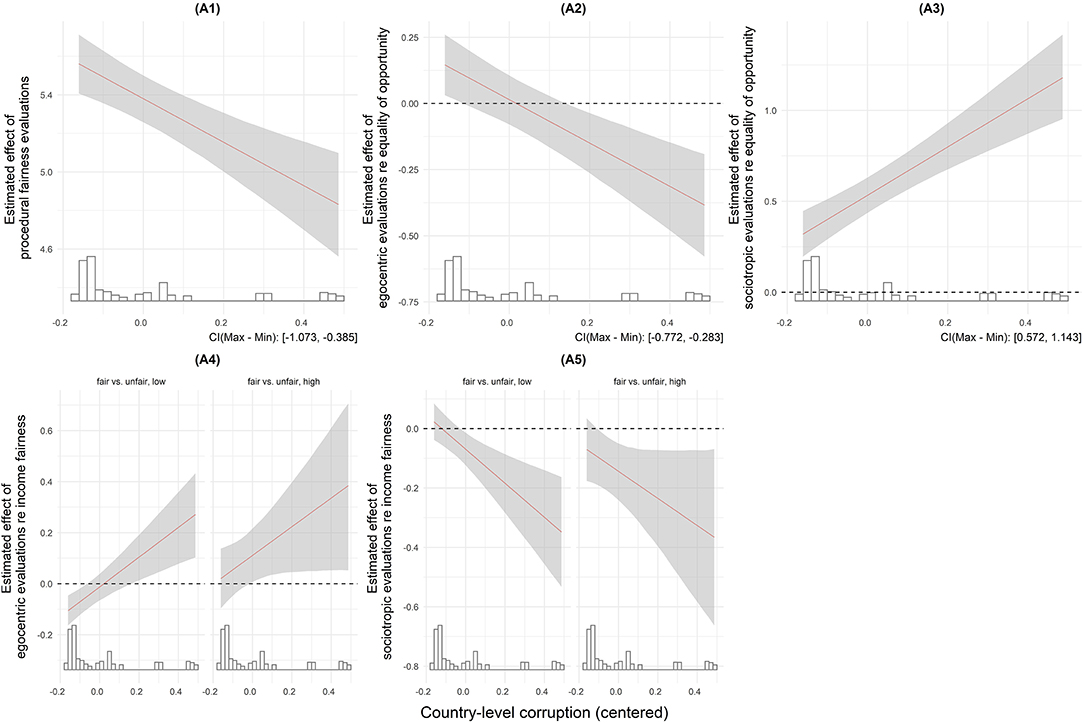

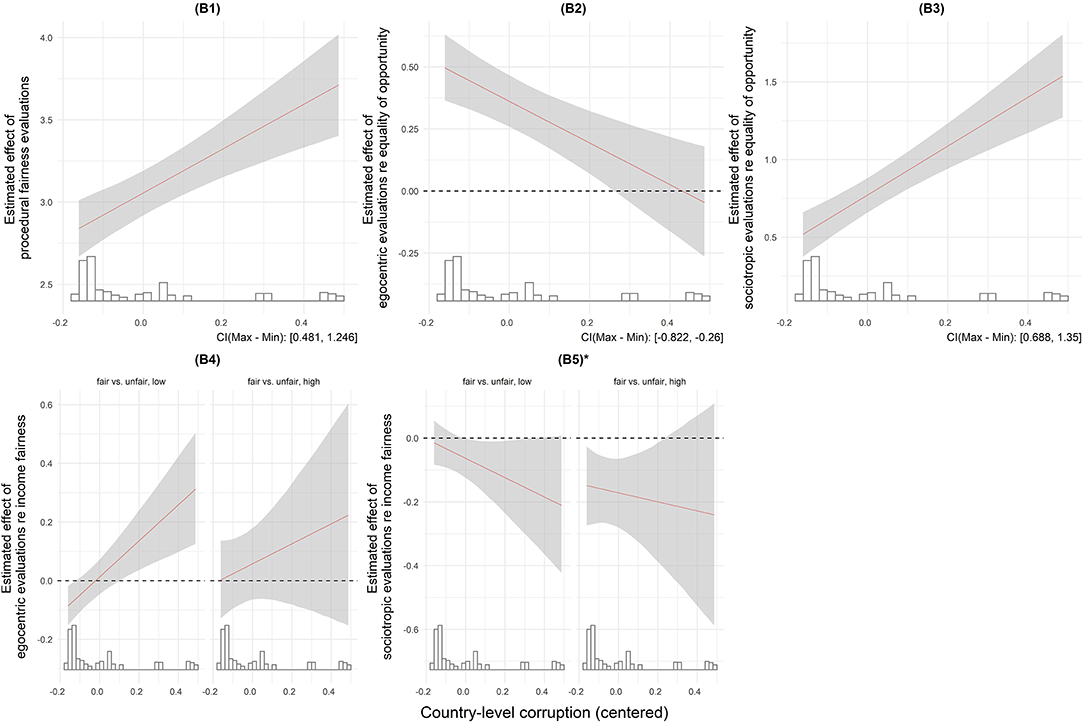

Given the identical pattern in the cross-level interactions observed for both country-level moderators, we restrict our more detailed assessment pertaining to the test of the amplification and attenuation hypotheses (H3a/b) to corruption only11. To provide a more intuitive discussion of our findings, Figure 2 displays the conditional effects observed for trust in representative authorities and institutions (model 3b in Table 2), while Figure 3 does the same for trust in regulative authorities and institutions (model 4b in Table 2). Overall, our findings provide empirical support for the amplification hypothesis (H3a), signaling that, with only few exceptions, individual justice evaluations exert a stronger impact on political trust in countries with higher levels of corruption.

Figure 2. Marginal effects of subjective evaluations of justice on trust in representative authorities and institutions, conditional on country-level corruption. All predictions based on model 3b in Table 2.

Figure 3. Marginal effects of subjective evaluations of justice on trust in regulative authorities and institutions, conditional on country-level corruption. All predictions based on model 4b in Table 2. Panels marked with an asterisk indicate statistically non-significant cross-level interactions.

Turning to our specific findings, Figure 2A1 shows that the impact of procedural justice evaluations on trust in representative authorities and institutions is less pronounced in countries with more rampant corruption. For trust in representative authorities and institutions, this is the only finding in line with the attenuation hypothesis (H3b), indicating that the differences in political trust levels between those with positive and those with negative evaluations of procedural justice are smaller in corrupt than in clean countries12. Looking at the conditional effects of egocentric evaluations related to equality of opportunity, in Figure 2A2, we observe a positive impact in clean countries and a relatively stronger negative impact in more corrupt countries. These findings imply two things: first, in clean countries, citizens with more positive evaluations are more trustful, whereas in corrupt countries, those with more positive evaluations are less trustful. Second, the differences in trust levels between those with positive and those with negative evaluations will be more pronounced in corrupt countries (see also panel A2 in Supplementary Figure 3), lending support to the amplification hypothesis (H3a). With regard to the conditional impact of sociotropic evaluations of equality of opportunity, Figure 2A3 certifies that these evaluations become increasingly relevant for political trust as we move from very clean to very corrupt countries. Accordingly, the differences in the levels of political trust between those with positive and those with negative justice evaluations are again more pronounced in more corrupt countries. For egocentric evaluations of income fairness, Figure 2A4 indicates that in clean countries, hardly any differences in political trust between those who consider their own income as fair and those who do not exist. However, such differences increase as we move from relatively cleaner to relatively more corrupt countries, with citizens judging their own incomes as fair in a corrupt environment showing the lowest levels of trust. Finally, Figure 2A5 indicates that sociotropic evaluations of income fairness are again more relevant in more corrupt countries, with the difference in political trust between those with positive and those with negative evaluations being more pronounced with increasing country-level corruption. Accordingly, those who consider the incomes of their occupation group to be unfair exhibit the lowest levels of political trust (see panel A5 in Supplementary Figure 3). In summary, for trust in representative authorities and institutions, the conditional effects observed for evaluations of procedural justice are in line with the attenuation hypothesis (H3b), while the conditional effects pertaining to egocentric and sociotropic evaluations regarding equality of opportunity and income fairness support the amplification hypothesis (H3a). Virtually identical findings are evident when considering a country's resource distribution as contextual-level moderator (see Supplementary Figure 1).

Figure 3 presents the corresponding findings for trust in regulative authorities and institutions. Compared to the findings presented in Figure 2, two major deviations appear. First, in Figure 3B1, the impact of procedural justice evaluations is more pronounced in countries with higher levels of corruption, lending support to the amplification hypothesis (H3a). Second, Figure 3B2 shows a decreasing impact of egocentric evaluations of equality of opportunity with increasing country-level corruption, supporting the attenuation hypothesis (H3b). For sociotropic evaluations of equality of opportunity (Figure 3B3), as well as egocentric and sociotropic evaluations of income fairness (Figure 3B4, B5), the conditional effects portrayed in Figure 3 match with the earlier findings for trust in representative authorities and institutions (see Figure 2) and thus support the amplification hypothesis (H3a). For sociotropic evaluations of income fairness (Figure 3B5), however, the conditional effects do not reach conventional levels of statistical significance. The same pattern of results, albeit not always statistically significant, is evident when analyzing a country's resource distribution as contextual-level moderator of individual justice evaluations (see Supplementary Figure 2).

In summary, then, the conditional effects of individual justice evaluations on political trust observed in our study largely correspond with the amplification hypothesis (H3a). Accordingly, the impact of citizens' justice evaluations on their political trust is generally more pronounced in political systems that are hampered by a shortage of actual distributive and procedural justice themselves.

In addition to this general conclusion, two more specific results warrant discussion. First, the conditional effects of procedural justice evaluations differ for trust in representative and regulative authorities and institutions. While their impact on trust in representative authorities and institutions is attenuated in systems with low procedural justice, it is amplified for trust in regulative authorities and institutions. This finding suggests that citizens connect the actual level of their political system's procedural justice more strongly to the workings of regulative than of representative authorities and institutions. Accordingly, our study points to the fact that citizens consider it the responsibility of regulative authorities and institutions, such as the courts and the police, to guarantee and uphold the fairness and integrity of political processes. Second, our analysis on the micro–macro conditionality of individual justice evaluations points to systematic differences concerning the effects of egocentric and sociotropic justice evaluations. For sociotropic evaluations, there is a generally positive effect on political trust that is more pronounced in countries with lower levels of actual distributive and procedural justice. For egocentric justice evaluations, this amplifying effect is not consistent in direction, revealing a puzzling pattern: in countries with an unequal resource distribution or high levels of corruption, those who consider their personal life chances and incomes as fair exhibit less trust in political authorities and institutions than those who perceive their personal circumstances as unfair. As there is no obvious (post-hoc) explanation for this finding and the overall effects of egocentric justice evaluations in comparison to sociotropic and procedural justice evaluations are rather small, the significance of these findings should not be overstated.

Conclusions

Adherence to the basic principles of distributive and procedural justice establishes an essential prerequisite for democratic legitimacy and thus the long-term viability of any democratic system. In this study, we contribute to the extant literature on the link between justice principles and citizens' legitimacy beliefs by analyzing the (conditional) effects of individual justice evaluations and contextual-level distributive and procedural justice on political trust. Our study demonstrates that citizens' evaluations of distributive and procedural justice constitute crucial determinants of trust in political authorities and institutions and that the impact of individual justice evaluations on political trust is particularly pronounced in political systems that suffer from low levels of actual distributive and procedural justice.

In comparison to previous research, our study offers three distinct contributions. First, we investigate the relevance of citizens' evaluations referring to both distributive and procedural justice, relying on nuanced operationalizations including citizens' egocentric and sociotropic justice evaluations. Second, we assess the micro–macro conditionality of distributive and procedural justice by analyzing in which ways the influence of individual justice evaluations on political trust varies across political systems with different levels of overall distributive and procedural justice. Third, we explore the effects of distributive and procedural justice on trust in representative and regulative authorities and institutions, allowing us to evaluate the respective relevance of justice concerns for trust in political authorities and institutions at both the input and output side of the political system.

More specifically, three main findings evolve from the three consecutive steps of our empirical analysis (see Figure 1). First, individual evaluations of distributive and procedural justice matter for citizens' political trust. In general, the effects of procedural justice evaluations are stronger than those of distributive justice. In addition, sociotropic justice considerations appear to outweigh egocentric concerns when it comes to trust in political authorities and institutions. These findings extend and qualify those of earlier albeit less encompassing studies investigating evaluations of distributive and procedural justice in isolation (Linde, 2012; Loveless, 2013; Zmerli and Castillo, 2015; Marien and Werner, 2019). Most importantly, they clarify that, when it comes to political trust, citizens put a premium on fair and transparent political procedures as well as a fair allocation of resources and opportunities for society as a whole, whereas the perceived fairness of their personal situation is of minor importance only. Second, country-level indicators of a political system's actual distributive and procedural justice exert inconsistent (direct) effects on citizens'political trust. For trust in representative authorities and institutions, a political system's actual levels of neither distributive nor procedural justice seem to be negligible when simultaneously accounting for macroeconomic performance. For regulative authorities and institutions, a political system's actual adherence to procedural justice matters for citizens' political trust even when taking its macroeconomic performance into account. With these findings, our study mirrors earlier research documenting mixed effects of procedural and economic performance on political trust (van der Meer, 2018). At the same time, however, it provides novel insights on the importance of distinguishing between different types of institutions with regard to political trust: citizens appear to attribute the realization of procedural justice predominantly to the workings of regulative rather than representative authorities and institutions. Third, our analysis highlights the micro–macro conditionality concerning the impact of individual justice evaluations on political trust. Specifically, our analysis provides evidence for the existence of amplification effects, signaling that the impact of individual justice evaluations on citizens' political trust is strongest in political systems in which the actual adherence to principles of distributive and procedural justice is severely compromised. This finding is at odds with earlier studies on income inequality showing that individual evaluations matter less (rather than more) in highly unequal countries (Zmerli and Castillo, 2015; Goubin and Hooghe, 2020). Our study thus points to the need of revisiting the meaning of income inequality in relation to more general matters of distributive justice, such as the equal distribution of basic resources and opportunities analyzed here.

Evidently, our findings come with important implications concerning the general viability of modern democratic systems. First of all, the fact that citizens' evaluations of both distributive and procedural justice are systematically related to their political trust suggests that citizens attribute responsibility for adhering or violating basic principles of justice to political authorities and institutions. Accordingly, with their concrete decisions on how the political system looks like and the way it is supposed to function, political authorities and institutions themselves can shape the extent to which they are perceived as legitimate by the citizenry. This conclusion can be further qualified when considering the conditional effects of individual justice evaluations found across political systems that exhibit a varying adherence to distributive and procedural justice. In political systems in which political authorities and institutions abide by general principles of distributive and procedural justice, differences in political trust between those who consider their own or the societal conditions as fair and those who do not are rather small. In other words, living in an overall just and fair political system renders the relevance of individual justice evaluations for political trust a matter of degree rather than substance. At the same time, the observation that justice evaluations matter most in political systems that abide the least by principles of justice implies that citizens with fair and unfair justice evaluations differ markedly in their political trust, with one group very content and the other very discontent with the workings of political authorities and institutions. In such conditions, political authorities and institutions (and specific incumbents who themselves may benefit from such conditions) may see little incentive to change the status quo and thus to provide all citizens with more equal access to basic resources and opportunities or to curb corrupt practices, as they draw their legitimacy from those citizens who perceive the current conditions as fair. Accordingly, improving the long-term democratic prospects of those systems that are characterized by an unequal access to basic resources and opportunities or that are hampered by rampant corruption may prove to be more difficult than desired from a democratic perspective (cf. Anderson and Tverdova, 2003, 105).

These considerations raise further questions on the relationship between justice evaluations and political trust that have not been addressed in the present study. The most obvious one pertains to why citizens may perceive and evaluate matters of distributive and procedural justice as fair even in those systems that exhibit severe distortions of justice. Investigating in more detail what considerations lie behind citizens' justice evaluations may help us to clarify the underlying mechanisms of the justice–trust nexus. Accordingly, a systematic incorporation of those justice principles that may inform citizens' evaluations, such as merit, equality, or need, in future analyses seems a promising avenue to further advance our understanding of the relationship between justice conceptions and political trust and thus the general preconditions of democratic governance.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/download.html?file=ESS9e03&y=2018 (ESS) and https://www.v-dem.net/en/data/archive/previous-data/v-dem-dataset/ (V-Dem).

Author Contributions

CS developed the research idea and led the development of the manuscript, performed all statistical analyses and created tables and figures, wrote most sections of the manuscript, and edited and prepared the manuscript for submission. CS and EH prepared the data analysis. CH wrote some subsections of the manuscript. All authors developed theory and hypotheses, revised and finalized the article, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The publication of this article was funded by the Baden-Württemberg Ministry of Science, Research and the Arts and by the University of Mannheim.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2021.642232/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^Individuals' images or normative ideals of how the allocation of resources and opportunities in society should look like are themselves derived from overarching justice principles, such as merit, equality, or need (Törnblom and Foa, 1983; Törnblom and Kazemi, 2012). In this study, what matters is whether or not citizens consider the distribution of resources and opportunities as fair, rather than the specific reasons for why they might do so.

2. ^With only five items, an informative structural analysis on the two-dimensionality of political trust is hard to obtain. Nevertheless, when specifying an exploratory factor analysis with two factors to be extracted, the empirical results largely confirm the distinction between trust in representative and regulative authorities and institutions (see also Schnaudt, 2019, 56–61; Schnaudt, 2020b).

3. ^While the different individual-level measures capturing evaluations of distributive and procedural justice are analytically distinct, they are empirically correlated. The correlations range from 0.2 (evaluations of procedural justice and evaluations of income fairness) to 0.5 (egocentric and sociotropic evaluations of income fairness). None of our regression models is hampered by multicollinearity problems, all VIFs range between 1 and 2.8.

4. ^The results presented in this study are not sensitive to the specific corruption indicator used. Using sub-indices provided by V-Dem or corruption indicators by the World Bank or Transparency International leads to the same conclusions.

5. ^Empirically, actual levels of distributive and procedural justice go hand in hand, with both indices being positively correlated at r = 0.7 in our sample of European countries (N = 27). See also footnote 3.

6. ^For a complete list of countries included, see https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/data/country_index.html (accessed December 10, 2020).

7. ^Supplementary Tables 1, 2 provide the results of additional models, incrementally including evaluations of distributive and procedural justice as antecedents of political trust. These models show that evaluations of procedural justice exhibit a stronger explanatory power than evaluations of distributive justice, as indicated by the size of the individual-level variance components.