94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci., 22 July 2021

Sec. Elections and Representation

Volume 3 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2021.630001

This article is part of the Research TopicVoting from AbroadView all 8 articles

Marjukka Weide1,2*

Marjukka Weide1,2*Electoral rights belong to the core of citizenship in democratic nation-states. Voting, then, represents an actualization of the relationship between the citizen and the political community. For citizens living outside the country in which they are eligible to vote, voting signifies a rare institutional connection to the country of origin. The aim of this article is to explore the introduction of the postal vote, a new form of voting for external voters at Finnish elections, from the grassroots perspective. The study focuses on how a central policy concern, safeguarding ballot secrecy, was resolved in the policy implementation by the witness requirement, and how the individual voters subsequently applied it. According to the voters’ accounts of the act of voting, the adopted method for underlining the importance of ballot secrecy in the Finnish overseas postal voting system, for many voters, makes little sense. While they effectively practice ballot secrecy, many fail to demonstrate this to the witnesses they were supposed to convince. Conversely, for these voters, the witness requirement merely works to break the secondary secrecy of elections, namely the secrecy of their participation itself. The empirical material for the article comprises policy documents and thematic text material (interviews, written responses) from 31 Finnish citizens living outside Finland. The article contributes to the scholarly debates on voting as a social, institutional and material practice. It further provides policy-relevant knowledge about grassroots implementation to various electoral administrations many of which, at the time of writing, face pressure to reform their repertoire of voting methods to function better in exceptional circumstances, such as a pandemic.

Finland adopted overseas postal voting in 2017, with the aim of enhancing the access to the ballot for its electorate abroad, counting 250,000 or 5.6% of all eligible voters in the 2019 parliamentary elections (Oikeusministeriö, 2020a). This was no on-the-spur-of-the-moment, but was the result of a 15-year process of lobbying and preparation. The reform was first considered undesirable chiefly because it would remove voting from the control of public officials, thus potentially undercutting the quality and trustworthiness of the entire Finnish electoral system (Oikeusministeriö, 2010). When adopted, the reform represented an inescapable tradeoff between compromised secrecy and citizens’ access to the ballot; the legislators now regarded the benefits of access to be more significant than the potential risks (Hallituksen Esitys Eduskunnalle Laiksi Vaalilain Muuttamisesta, 2017). This article explores how the Finnish citizens abroad made sense of their newly established postal voting option at the 2019 Finnish parliamentary and/or 2019 European elections, organized only six weeks apart in the spring/early summer. As the concern for ballot secrecy, a key hurdle for the adoption of the reform, was resolved by installing a witness requirement for postal voting, the study focuses on how Finnish overseas voters practice the casting of the ballot when independently responsible for their voting for the first time.1 With electoral administrations in various countries currently facing pressure to improve their voter facilitation methods to ensure high quality of elections even in times of crisis, studies on the implementation of different solutions hold special policy relevance. The witness requirement is a feature not frequently found in other postal voting systems within the EU countries (Faulí et al., 2018, 49–50), which makes the case especially interesting.

The approach applied in this study belongs to the family of interpretive policy analysis (Wagenaar, 2011; Schwartz-Shea and Yanow, 2012). Secondly, I position the study within an understanding of institutions that views them as (constituted by) practices (Bevir and Rhodes, 2010). Elections, in this view, come into being through various practices and acts of campaigning, establishing the electoral registers, voting, counting votes, calculating seats, announcing results, and later, destroying ballots. All of these are regulated by laws and lower-level statutes. The success of elections as a reliable, orderly and reputable mechanism to reproduce the core institutions of representative democracy, nonetheless, also depends on the voters’ practice of shared social norms. This aspect of the voter’s own role, as compared to the electoral officials, is accentuated in remote voting (Faulí et al., 2018).

Examining implementation at the grassroots level has long been at the heart of interpretive policy work. From Lipsky’s street-level bureaucrats (Lipsky, 1980) to bevir and Rhodes’ stateless state (Bevir and Rhodes, 2010), case studies employing ethnographic and other qualitative methods established themselves within political science. It is within this tradition that I present the study of postal voting in Finnish elections, as a critical case (Flyvbjerg, 2001, 78–79) illustrating how a specific mechanism put in place by the policymakers is not always followed by even the most motivated policy targets, the principle behind the mechanism nonetheless staying fairly intact.

The theoretical background of the study is laid out in the next two sections. Drawing especially on Stephen Coleman’s work (Coleman, 2013), I present voting as an activity situated in specific locations and social contexts. This approach contrasts with abstract notions of elections as a democratic mechanism or voting as an aggregation of opinions. Next, I present the concept of ballot secrecy. It is at the crossroads of these two themes that the empirical case plays out. In the section following Empirical Material and Analysis, I contextualize the case through an analysis of the process leading to the form of postal voting to be adopted. The section Postal Voting Accounts, then, contrasts the participants’ accounts of voting with the ideal of implementation established by a ministry instruction. The concluding section discusses the meaning of these findings for the voters and the postal voting procedures.

In this study, voting is approached as an act of citizenship by which individuals connect with their political community through a set of micro level tasks performed in due time and manner (Coleman, 2013, 11–12). For eligible voters living outside their country of citizenship, this opportunity of connection is bound to appear to be a complex offering. According to survey research, feelings of inadequacy in political knowledge for making an informed voting decision are common, and long distances to polling stations frequently hinder the opportunity to vote (Peltoniemi, 2018, 119). At the same time, voting means a way of maintaining a connection to the (imagined) nation (Ibid., 170). The symbolic contact to the state may be underlined by the electoral venue, as many of the overseas polling stations are established at Finnish embassies.

In their book How voters feel (2013), helping to bring the affective turn to political science (see also Kantola and Lombardo, 2017, 43–47), Stephen Coleman outlines an approach to voting that recognizes its performativity. Firstly, Coleman (2013, 18) points to the aspect of discursivity—“the power of utterances to make things happen”. Secondly, the idea of performativity arises from an acknowledgment that the relationship between structure and agency always remains unstable. Those eligible to vote exercise a degree of creativity and negotiate their positions in relation to the frameworks given. The frameworks, nonetheless, are inevitably there: while the act of voting expresses free, individual choice, it is according to minutiae of the common rules that the choice is supposed to be enacted (Ibid. 15–17).

Some common rules of desirable polling station behavior relate to the right movement in the voting space (e.g., queuing). Many of them pertain to respecting ballot secrecy, e.g., the avoidance of speaking about electoral choices. In fact, it seems that speaking as little as possible at all is a widespread social norm (Coleman, 2013, 3). Further, some rules regulate material issues, like not showing one’s marked ballot. The ballots, the booths, and the ballot boxes are standardized and recognizable as authoritative (Hollweg, 2015, 186–187). With a reference to Donna Haraway (2000), Brenda Hollweg (2014, 158–159) writes about subjectivity coming into being in material–semiotic interactions. Making sense of what takes place in voting thus calls for attention to the micro level questions of what, where and how (see Davies, 2010).

Beyond the role that social connectedness plays in mobilizing voters (Reilly, 2017), the very exercise of franchise has an inevitable social aspect. Not needing to participate in the election day performance, experienced as awkward due to the familiarity of the other voters or the volunteering election organizers, has even been reported a reason to prefer advance voting (Pesonen et al., 1993, 94). With postal voting, the social setting of voting becomes customizable by the voter but in the Finnish case, it is not eliminated due to the witness requirement. As the requirement exists not to confirm identity as such (see Faulí et al., 2018, 48–50) but to guarantee the keeping of ballot secrecy, the requirement thus constitutes secrecy as performative.

Ballot secrecy became a standard feature of quality general elections after World War II (Przeworski, 2015); in the words of Jørn Elklit and Michael Maley (2019, 61), an “almost universally enshrined (…) component of the free and fair elections that laws and constitutions promise”. Yet, as Elklit and Maley demonstrate, ballot secrecy remains a multidimensional concept and its practice at the various stages of the electoral process is by no means a given, even in countries regarded as being high-level democracies. Openness of voting continues to be studied as a not-so-distant historical fact (Teorell et al., 2017). Concerning both general elections and other voting situations, it attracts the attention of both empirical political scientists (e.g., Esaiasson et al., 2019) and political theorists (e.g., Engelen and Nys, 2013; Vandamme, 2018) for potential contemporary applications. This article, nonetheless, recognizes the principle of secrecy as a point of departure. This is a matter of accepting the empirical, contextual setting of the case in a political system that is based on the secrecy principle. The criticism that I make against the way of organizing secrecy in the Finnish postal voting case invites us to rethink the interpretations and practices of secrecy, as well as the communication about it, in a situation in which the state does not control the act of voting by itself. In other words, the critique does not pertain to secrecy as a general principle.

In deciphering the concept of ballot secrecy, Elklit and Maley (2019) took Stein Rokkan’s definition as their starting point. There, the practice of secrecy operates to isolate the voter both from their peers (though the inability to prove the quality of one’s vote afterward) and from those in more powerful positions than themselves (through being able to keep voting decisions private) (Rokkan, 1961, 143). However, Elklit and Maley (2019) add that keeping secret the sheer fact of participation in elections has later established itself as a dimension of the concept. The purpose of ballot secrecy has thus been viewed as three-fold: to guard the privacy of political opinion, to inhibit coercion of voters, and to impede the buying of votes (Elklit and Maley, 2019, see also; Manin, 2015). While the first purpose is most important for the individual voter, the two others relate to a communal interest within the polity to protect electoral fairness and integrity (Elklit and Maley, 2019, 67–68). Exceptional arrangements that compromise the “gold standard” secrecy of polling stations that enable assisted voting and remote voting have been accepted. Within both these categories, a variety of practices aimed at balancing between the facilitation and secrecy have been developed (Ibid. 70–72).

While the concept of “secret ballot” refers to much more than the ballot paper itself, secrecy of the elections has everything to do with practical and material arrangements. One of the main criticisms by Elklit and Maley (2019) of the Swedish general elections concerns how the ballot papers are placed in the electoral space. Secrecy at the polling station emerges in a complex interplay of artifacts and people, both voters and election organizers, moving in the space in an orchestrated fashion, performing specific, barely noticeable acts of writing and delivering the ballot (see Coleman, 2013, 16). This brings us back to considering the act of voting as embedded in its physical and social context. With postal voting, the formal conditions for secret voting change, and so do the physical and social contexts in which voting, and thus the officially expected secrecy, unfolds. This moment of a “rupture” in the system offers an excellent point to examine voting “as a performative act (…) to access the gap that exists between institutional norms and everyday experiences” (Coleman, 2013, 18).

The empirical material for this study comprises policy documents, interviews and written responses, thus building on the notion of “data triangulation” (Flick, 2018). All the policy and legal documents analyzed here (26 texts and an online film) are public; most of them are available online. Their analysis serves the purpose of contextualization of the case. The selection of the documents was based primarily on the their weight in the political process and include preparatory papers and reports from the process leading to amending the Elections Act in 2017. The instructional film on postal voting represents an operationalization of the framework adopted for the new participation method. The policy sources have been referenced similarly to the literature and are included in the list of references.

The interviews with and written responses from Finnish eligible voters living abroad were collected by the author within the Facilitating Electoral Participation from Abroad (FACE) project in July–October 2020 and April 2021 (Weide et al., 2021). For this article, 20 interviews (marked with I and a number) and 11 written responses (marked with W and a number) were used.2 The interviewees and respondents were recruited primarily by contacting respondents from the FACE survey3 who had submitted their e-mail address for this purpose, but there was also an open call in the Finland Bridge magazine and the newsletter of the Finland Society in May 2020. The interviews were conducted over computer (Zoom, Skype) or regular mobile phone connection and took an average of 30 min each. The interviews were analyzed in a transcribed form with the Atlas. ti software. A clear majority of the participants were working-age, female Finnish citizens living in Europe who were born in Finland. This said, some male Finns, pensioners and young adults, as well as individuals living outside Europe also took part. The sample is thus not representative of the Finnish overseas electorate as such but should be approached as an activist segment of a kind, the experiences of which constitute a critical case that can enable policy learning. Excerpts from the empirical material presented here were translated from Finnish into English by the author, unless otherwise indicated.

The empirical material for this study that was composed with individual participants is bound to reflect the general phenomenon of a “self-selection bias” (see Warren, 2012). What is more, a semi-structured research interview requires strong commitment from the participant due to factors such as the need to be available at a fixed time, the duration of the interview, and the non-anonymity vis-à-vis the researcher conducting the interview. This affects the composition of the group of interviewees and thus the conclusions to be drawn.

While some interviewees opted in due to their good will for social scientific research, most participants were motivated by the theme of the interview (voting and postal voting at Finnish elections). They “had something to say” and perhaps had even been looking for a channel through which to make their views heard. Most interviewees had taken part in the FACE survey the year before and submitted their e-mail address for being contacted again in the case of a follow-up. In other words, most participants had been “tried” thrice: first they had chosen to say yes to the survey, then allowed themselves to be contacted again, and finally they had said yes to being interviewed. Written responses represented a slightly “lower-investment” alternative, rarely producing more than a page of text in total.

Why does it make sense to study the most engaged voters? For a comprehensive evaluation, it would be beneficial to be able to reach out to the least engaged, as they are likely to have the most negative perceptions and experience and a vast range of issues to be accounted for in improving the system. However, they would often be the hardest-to-find eligible voters, as their contact details in the official Finnish registers do not exist or have expired. What can be pursued is a critical case study that helps to reveal which issues are likely to be widely experienced negatively and/or practiced differently from the model. The logic is: we can expect these participants to represent what the overseas postal voting can be at its best, according to the Finnish framework. If those most motivated to participate have difficulties with something, or apply instructions divergently, there is good reason to believe that the less motivated would also face these issues (and more) (see Flyvbjerg, 2001, 78–79).4

What is more, there might be little sense in interviewing eligible voters positioning themselves indifferently toward the topics; the very idea of personal interviewing is to provide rich, detailed and in-depth information (Morris, 2015, 62–64). As the interviews were conducted a year or more after the elections, those not paying much attention would also have been less likely to recall their actions. The factual accuracy of the interviewees’ accounts plays a smaller role in this study than their perceptions of what took place, as the latter will inform their future action; yet it can be difficult to produce a meaningful narrative if the event has passed almost unnoticed.

The qualitative material collection within the FACE project was initiated out of the need to gain insight into and validate some of the observations based on a prior survey. The survey had probed into the respondents’ postal voting perceptions and/or experience by statements and by open-ended questions that teased out comments on the topic. Apart from the unawareness of the postal voting option as such, the two most prominent themes appearing in the written comments were 1) timing and postal services and 2) the witness criterion (Wass et al., 2021 this special issue). Also, the survey results (Ibid.) suggested that the witness criterion was assessed more negatively than other elements of the system that were in the control of the state organizing the elections.

The interview guide and the set of inspirational questions sent to those participating in the written response pertained to the participant’s previous voting experiences at the Finnish elections (if any) and their postal voting experience.5 The participants were invited to describe these experiences freely, and follow-up questions to both practical issues, opinions and feelings related were made when needed. As to postal voting, the interviewees and respondents were prompted to describe the process step-by-step; follow-up questions were posed regarding the postal services and organizing the witnessing if the interviewee did not comment on these spontaneously.

The analysis proceeded in three steps: a contextual step at the legislative level, an intermediate step at the implementation level, and an application step at the grassroots level. First, I read texts originating from the legislative process instituting postal voting. I focused on tracking what was said about ballot secrecy, including how it was argued that the witness requirement could alleviate the threats that postal voting was seen as posing to ballot secrecy. The next step was to scrutinize how the legal framework adopted was translated into a practical guide to the voter by the electoral authorities. Here, I applied three analytical lenses based on the theoretical approach, observing which 1) material or physical, 2) legal or institutional, and 3) social aspects were presented in the postal voting guide film6 and how. Through these, I established an “official choreography of postal voting”. Finally, I applied these lenses to the interview and written response material, categorizing the participants’ accounts of the moment of voting into those conforming to the official choreography and those creating their own arrangements.

Incorporating overseas postal voting into the Finnish electoral system (Laki Vaalilain Muuttamisesta, 2017) was preceded by a lobbying and preparation process of more than 15 years. Below, I set the reform in a broader context of the public promotion of democratic participation. The aim of this contextual analysis is to shed light on the expectations behind the reform and the public anxieties related to it, also helping to understand the Finnish “lag” in adopting overseas postal voting compared to other EU countries.

The initiative for overseas postal voting came from the Finnish Expatriate Parliament (FEP) that argued this would enhance the access to ballots abroad, and thus increase inclusion and equality (Paasio and Nordqvist, 2008; Strandberg and Castrén, 2017). The FEP is a nongovernmental collaboration organ for Finnish expatriate and cultural associations and communities, founded in 1997. While the Finnish diaspora has been all but invisible in Finnish society, some of the political objectives of their interest organ have been realized along the way, including the introduction of dual citizenship in 2003 (Fagerlund and Brander, 2013, 1–2). Postal voting, in contrast, took such an extensive period to get through that, in the meanwhile, the infrastructure it relies on—the public mail services worldwide—have gone into decline (see Decker, 2016). In making sense of the process below, the underlying question is why, despite a favorable trend in facilitation of political inclusion, did it take such a long time to adopt postal voting.

The concept of “policy for democracy” was established during the first decade of the 2000s in the Finnish central administration—in line with the general rise of participatory policies, also dubbed “the participatory turn” (Saurugger, 2010). The Finnish policy for democracy, nonetheless, covers the developing of both the electoral/representative structures and the enabling of other forms of participation. One of the issues addressed by the policy has been the decline of turnout rates (Valtioneuvoston demokratiaverkosto 2019, 10–11), as the Finns have been consistently outperformed by their Nordic peers (Bäck and Christensen 2020, 449). Also, the participation of less engaging groups, such as young people, has received special attention within the policy (see Ministeriöiden demokratiaverkosto et al., 2010). Finns abroad, in a sense, can be positioned at the crossroads of these two policy issues of general turnouts and less engaging groups: The size of the overseas electorate is large enough (fluctuating between 4.9 and 7.1% of the total electorate in 1983–2019) to have a negative impact on the total turnout with their meager participation.7

The national level flagship of policy for democracy, the Democracy and Elections unit at the Ministry of Justice, has launched several participatory online channels. The prospects of online voting, in contrast, have proven difficult. A pilot trial of electronic voting at polling stations during the 2008 municipal elections led to a retake due to inadequacies in the software and the user instructions (Oikeusministeriö, 2008). Later, the continuing political interest in online voting led to two commissions on the issue (2013–2015, 2017) (Oikeusministeriö, 2020b), but the commission reports have made cautious conclusions, the most recent one assessing the risks more significant than the benefits (Oikeusministeriö, 2017). The 2008 major setback in reforming the voting system may have influenced the central administration’s approach to developing new voter facilitation methods in general, and it thus partly helps to contextualize the lag in adopting postal voting.

The FEP had been making resolutions to call for postal voting since 2000. It had been suggested in various other democracy themed reports from 2005 onwards that a specific report should be compiled about the prospect of enhancing voting from abroad, including postal voting (Kansanvalta 2007 -toimikunta, 2005, 59–61; Salminen and Wilhelsson, 2013, 53; Valtioneuvosto, 2014, 30–31; see also; Työministeriö, 2006). A summary of comments on the issue from various actors implied that there had already been a positive approach to postal voting from abroad in 2006 (cf. postal voting for domestic use) (Oikeusministeriö, 2006, 14–15).

In 2010, the Ministry of Justice issued a round of comments on a postal voting memorandum it had completed two years earlier. The comment summary (Oikeusministeriö, 2010) reveals that political parties were divided. Importantly, the two big parties of the coalition government (The Center Party and the National Coalition) took “a reserved” position. The National Coalition expressed hopes for online voting, but otherwise those skeptical about the prospective postal voting reform voiced concerns about removing the presence of electoral authorities, guarding the freedom and secrecy of the elections. This was especially clear in the expert comment by Lauri Tarasti, the “father of Elections Act” (Junkkari, 2017), who remarked: “Our system is no opinion poll where a certain margin of error is accepted.” (Tarasti, 2017, 4).

According to the Head of Elections at the Ministry of Justice, the government parties failed to reach a mutual understanding on the issue during the subsequent 2011–2015 electoral cycle.8 It was only after the 2015 parliamentary elections that the lobbying efforts by the Finland Society bore fruit, and the Minister of Labor and Justice reopened the preparation (Ibid.). When the Government Bill on the issue (Hallituksen Esitys Eduskunnalle Laiksi Vaalilain Muuttamisesta, 2017 ) was given to Parliament, it proceeded swiftly and was adopted at the end of the year.

In the brief plenary debates about the Government Bill, there was little disagreement about it (Eduskunta, 2017a; Eduskunta, 2017b). Nonetheless, several MPs expressed their concern about the ballot secrecy after the reform or underlined its importance. This was also the most frequently noted single issue among the comments on the draft bill (Oikeusministeriö, 2016), and it was especially emphasized in most of the reports given to the Constitutional Law Committee (Hidén, 2017; Jääskeläinen, 2017; Mäenpää, 2017; Tarasti, 2017). The smooth parliamentary process implies that the facilitation of access to participation and equality perspectives were now perceived as being more important than the potential ballot secrecy risks.

The Swedish system of overseas postal voting (Solevid, 2016) was initially considered as a model for Finland in the mid-2000’s discussion (Oikeusministeriö, 2006, 14), and it was along those lines that postal voting was adopted in 2017. A noteworthy common element in the Swedish and Finnish systems, setting them apart from most other postal voting systems (Faulí et al., 2018), is that they require the voter to recruit two witnesses. The use of two witnesses was to serve as a proxy for the election officials guarding the secrecy of the ballot (Hallituksen Esitys Eduskunnalle Laiksi Vaalilain Muuttamisesta, 2017, 18).

During the process that led to the adoption of postal voting, a few alternative settings related to the scope of the reform were discussed, but in the end, they were not implemented (Oikeusministeriö, 2010; Hidén, 2017; Tarasti, 2017, 5). However, none of those other dimensions was salient in the discussion the way ballot secrecy was. In this section, I focus on how the new practices of ballot secrecy were discussed in the government bill and by experts heard by the Constitutional Law Committee, and how they were later introduced for the postal voters to follow.

The government bill (Hallituksen Esitys Eduskunnalle Laiksi Vaalilain Muuttamisesta, 2017) proposed that as postal voting would remove voting from the supervision of electoral officials and place the sole responsibility for preserving ballot secrecy on the voters themselves, the voter would be obliged:

1) to secure ballot secrecy independently,

2) to affirm in the ballot cover letter that they had done so, and

3) to invite two witnesses who would confirm by their signatures and details that no infringement of electoral freedom or secrecy had taken place.

The bill conceded that the electoral committees receiving the postal votes would not have the opportunity to check the authenticity of the signatures. Nonetheless, it was contended that the central electoral committees would be better equipped this way to evaluate whether voting had proceeded lawfully, than from the voter’s affirmation alone (Ibid., 18). As one of the experts heard by the committee put it: this requirement “nevertheless emphasizes the responsibilities of the voter to them” (Tarasti, 2017, 4; see also Mäenpää, 2017, 2).

The Constitutional Law Committee further discussed the matter of sanctioning of the breaking of ballot secrecy. It was established that violations, if detected, could be prosecuted within the existing legal framework, under the classifications of false evidence to authorities, coercion or forgery (Jääskeläinen, 2017). Nonetheless, it was also concluded that criminal cases would be difficult to pursue (Ibid.). The provisions adopted on postal voting in the Elections Act (Vaalilaki, 1998, 5a) do not explicitly deal with breaches of ballot secrecy.

Once the bill was passed and took effect, instructions on the new form of voting were formulated and published by the Ministry of Justice on their elections website (www.vaalit.fi), including an instructional film on YouTube that demonstrates how the postal vote is to be conducted (Oikeusministeriö, 2019). Below, I analyze the film through the lenses of the material/physical, legal/institutional and social, arriving at an interpretation of an “official choreography” that fixes the normative ideal of the do-it-yourself-voting.

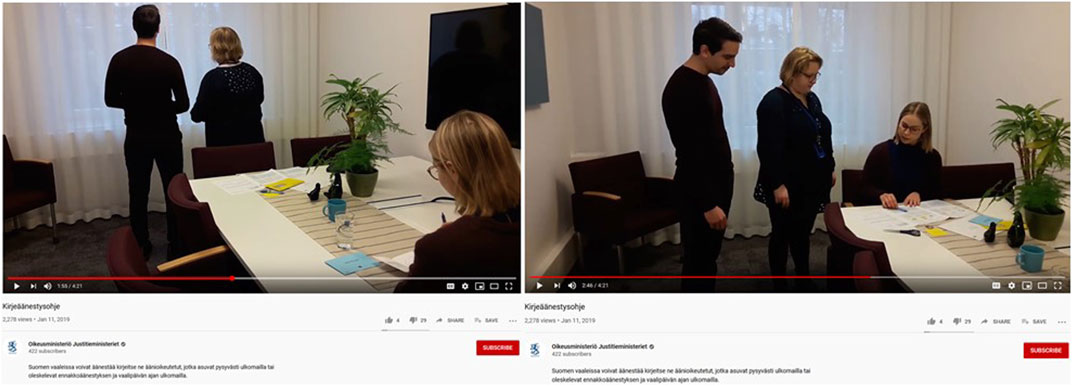

The postal voting instruction film starts with a presentation about the preparatory steps of postal voting (eligibility, timing) using text slides, animation and filmed material without actors. The voter/actor then appears, sitting with their back to the camera, opening the large white envelope containing the postal voting material. The voter takes out the instruction and cover letter papers, the empty ballot—a folded white card—the turquoize ballot envelope and the voting letter envelope, colored yellow on the front. The voter is also shown scrolling through internet pages, searching for information about the candidates.

Next, two witnesses have entered the room and stand with their backs to the voter who then marks the ballot (see Figure 1). The narrator explains the voter’s individual responsibility for ensuring the secrecy of the ballot. The voter slips the ballot into the turquoize envelope, dips their finger into a glass of water to moisten the envelope glue, and seals the envelope, running their hand on the flap to ensure that the glue sticks.

FIGURE 1. Screenshots from the postal voting instruction film (duration 4:21). Source: the Finnish Ministry of Justice.

In the final scene, we see the voter first fill in their own details in the cover letter. They then explain to the witnesses, now standing sideways to the camera, what they are expected to write in the letter, and the witnesses are consecutively shown filling their part. The voter meticulously folds the letter and places the ballot in the fold, then slides them into the yellow-fronted envelope and closes it. The film ends with an animation that repeats the steps of postal voting.

Focusing on the material and physical aspects of the film, all the phases of postal voting that are presented by actors take place in a single space—a meeting room set as a home by adding a few decorative elements. What happens before and after, requiring moving elsewhere, is presented in other ways. It is thus implied that the actual postal voting starts with the opening of one envelope and ends with closing another. The film is cut so that the viewer is shown little movement by people other than the movement of arms and hands. This way, voting is constructed as a static event, rather like a craft activity: with the camera zooming in, the voter uses a letter opener and scissors, they fold and glue, they write. They readjust the cover letter inside the yellow cover envelope to make the address show better out of the designated transparent plastic window in the envelope.

The attention to the crafts makes sense from the perspective that even a relatively small slip can ruin the vote: leave the ballot envelope open and the ballot will be canceled.9; shove in the cover letter the wrong way around and the envelope will have no visible address on it. Furthermore, the validity of the postal vote is assessed through the correctness of the way the ballot and the cover letter are filled in (Vaalilaki, 1998, § 63, 66 g, Jääskeläinen, 2017, 2). As Finland boasts having “the best elections in the world” (Leino-Sandberg et al., 2020, 384), one can also sense the expectations about the postal voters to excel in handling the detail.

The institutional and legal rules are most importantly conveyed by the narrator’s voice on the film, combined with text on the screen, walking the viewer through the practical steps of postal voting. Looking specifically at what the film says about ballot secrecy and the witness requirement, we first find the witnesses mentioned in the “before voting” checklist, on which the last point states: “you have invited two witnesses to be there”. In the section of the film in which voting is enacted, the text “take care of ballot secrecy” appears in two places, and the narrator’s voice instructs: “Fill in the ballot so that no one sees what you write on it.” The narrator also reminds the voter that it is their responsibility to have two witnesses present when the postal vote is conducted. After explaining the voter’s part of the cover letter form, the narrator says: “Both witnesses must (…) sign the attestation stating that you have voted in such a manner that election secrecy has been preserved and electoral freedom respected while voting.” Further, the personal details which need to accompany the signature are described.

The electoral authority’s perspective characterizes the film: for the authorities, what matters in the end is that the cover letter is completed in a manner that does not hint at any irregularities. It is said in the film that the witnesses need to be present at the time of voting, and that they need to attest by their signatures that the voting has taken place appropriately in relation to ballot secrecy and electoral freedom. How they can and should assess this is left unexplained. In fact, the witnesses themselves are not addressed directly at all, as the film only instructs the voter, and it is implied as the voter’s responsibility to take care of the communication with the witnesses. The government bill (Hallituksen Esitys Eduskunnalle Laiksi Vaalilain Muuttamisesta, 2017, 24) delineated the responsibilities between the voter and the witnesses in the following manner: “It is not the duty of the witnesses to take care of the realization of the said principles (ballot secrecy and electoral freedom) but only to witness that the voter has taken care of them.” At the level of choosing a suitable place for voting where it is possible to mark the ballot undisturbed, this division of labor makes sense. However, in order to be able to assert by their signature that specific principles have been practiced, the witness should make an assessment of it as the act of voting unfolds.

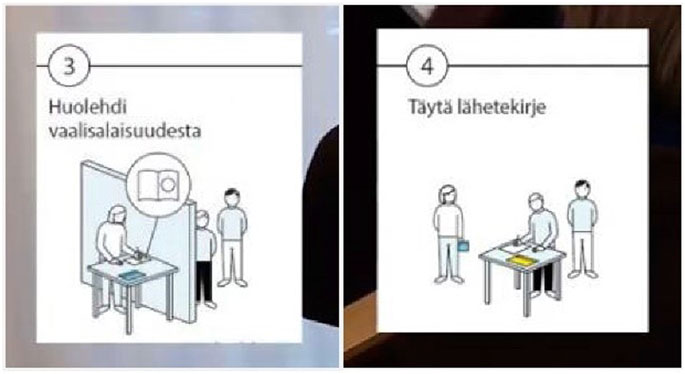

From the perspective of the witness, then, what one can observe in the film are the visual cues as to what participation is expected of them. The clearest example is set by the witnesses that the viewer encounters turning their backs when the voter sets out to mark the ballot. Next, we see them standing close to the seated voter showing the cover letter to the witnesses, who subsequently sign it. Interestingly, the image instruction appearing on the screen (Figure 2) places the witnesses behind a wall, possibly indicating another room for the time when the ballot is being marked. Either way, ballot secrecy and electoral freedom seem to be simultaneously emphasized by the prominence of the witnesses in the film and taken for granted by the implicitness of what the witnesses are expected to observe. It remains unclear if the witnesses are supposed to check that the ballot is unmarked at the beginning of the event (for if it is not, they cannot really know under what kind of conditions it has been marked). The voter on the film shows the empty ballot to the camera but it is as though this sequence takes place before the entry of the witnesses.

FIGURE 2. Image instructions on the postal voting instruction film. Source: the Finnish Ministry of Justice.

Lastly, scrutinizing the instruction film through the lens of social interaction, the communication between the voter and the witnesses seems formal. Yet the voter and the witnesses are bound to know each other at some level, since a voter would hardly invite strangers to volunteer for this purpose. Indeed, the voter is advised to prepare for their postal vote by inviting two witnesses, indicating that voting will take place at a locality of their choosing, possibly in their home. The witnesses in the film meet the voter in a space in which only the three of them are present. Although we can see that the actors in the room speak to each other on a couple of occasions during the film, their voices are muted, which underlines the impression of silence. We see the voter explaining about the cover letter form and the witnesses nod. The witnesses remain standing as they fill their slots and while the voter completes packing the cover envelope. It is almost as though the witnesses serve the voter; it is they who turn their backs (instead of the voter turning or covering the ballot while writing on it).

To summarize: applying the lenses of the physical/material, the institutional/legal, and the social, an idealized choreography of postal voting appears where the voting takes place in a closed (rather than open) space with only the voter and the two witnesses present. The procedure is well-prepared by making the necessary tools available beforehand, conducted solemnly and meticulously, without much unnecessary talk or movement. The witnesses turn away and turn back, staying observant at the side until the pieces have been put together and the second envelope sealed. The instructor’s voice guides the voter about ballot secrecy but does not address the witnesses directly, leaving them without detailed criteria for evaluating the realization of the aspects of voting they attested about. In the next section, this ideal model is contrasted with the interviewees’ and the respondents’ accounts of real-life voting situations.

The overseas postal voting option was welcomed by most respondents and interviewees reached by the FACE research project. Yet, they highlighted many inconveniences and limitations. Out of twenty-four written comments submitted through the survey on the specific topic of the witness requirement, fifteen stated that the respondent had abstained from voting because of it (Wass et al., 2021 in this special issue). Judging by the number of successful postal votes (6,183), many were able to solve the issue one way or the other. The variety of practical arrangements found in the interview and written response material is presented in Figure 3. A minority of the research participants (7) had conducted their voting by applying what I call the official choreography. Instead, most interviewees (18) had separated the practice of ballot secrecy from the formal requirement of witness signatures.10 While the postal voting instructions had not been followed to detail in these cases, none of the interviews or responses implied that ballot secrecy had been breached by photographing the marked ballot, showing it to family members, or other ways. My reading of these accounts is that ballot secrecy, for these voters, rather intuitively meant keeping the moment of marking the ballot strictly private. Such view is exemplified by the end of quotation from interview four in the section below in which the interviewee expresses how they appreciate being able to mark the ballot in peace and unrestricted by polling station opening times.

In the following sections, I first discuss the interview material in relation to the official voting choreography. Then, I zoom on the material, institutional and social dimensions related to the witness requirement as expressed in the participants’ accounts. The subsequent section reflects on the participants’ explicit views on the witness requirement and ballot secrecy.

I have above placed the voting accounts on a continuum between the ideal choreography and voter-led arrangements in voting according to the degree of liberties taken in relation to the norm. While few participants had conducted their voting according to all the steps and turns in the official instructions, some variations were minor. At the other end, we find one participant signing the witness slots by themselves.

The research participants who conducted their vote along the lines of the official choreography had either invited witnesses to their home, visited someone to vote, or voted at their workplace. Ballots were marked on kitchen tables and office coffee rooms. For some, voting this way was a quick moment during other activities—others served coffee, took time to chat or even celebrate the event. In one of the most detailed accounts describing a “by the book” situation, an interviewee recalls (author’s emphases):

I12: And then of course you needed two witnesses, so I decided to vote at work. So my profession is (AN ACADEMIC PROFESSION) (…) so it was quite fun because they (colleagues), it was interesting for them to follow and see how this looks and how this works, is this a good thing for democracy (…)

MW: So the moment itself when you gave your vote, noting the number in the paper, did you also do it right there, were the witnesses present in that moment?

I12: Yes they were. I did turn, I stepped aside a bit and wrote. But it wasn’t like my, I mean, there is no way they would know what I voted for.

In this coffee room voting situation, then, the interviewee happily compromised the secondary secrecy of the vote, letting more than two curious colleagues become aware about the fact of their electoral participation, to follow and discuss the event. Despite the open character of their voting space, they secured the primary secrecy of their actual voting decision and the marking of the ballot. Thus, the main deviation from the idealized choreography in this example relates to the extended audience and possible coffee room buzz by the colleagues.

In contrast, a typical voter-based arrangement would involve marking the ballot alone at home or a private office, and then taking the cover letter along to friends or colleagues. A variation would entail the voter signing the cover letter (not the ballot paper) in the presence of the two witnesses. At the low-key end of the spectrum, the voter would fill in the cover letter when it suited, and would ask for the signatures and details from each of the witnesses separately in other instances. In the latter case, the cover letter seemed to represent a mere bureaucratic certification, not a proof of worthiness or integrity of the vote. In the excerpt below (emphasis by author), the voter recognizes not having paid much attention to informing the witnesses. The view was common that the witnesses were acting in good faith based on a solid trust in the voter rather than on the basis of a comprehensive understanding of the Finnish postal voting procedure; also, voters who reported making some effort to explain the system could express mild skepticism about the level of awareness of the witnesses.

I4: Myself, I fixed two colleagues for it. They didn’t really have a clue about what they were signing, practically. (…) So officially speaking, probably it was done wrong (…). A few local Finns organized it so that, because before the pandemic the Finns used to go for drinks once a month, they brought the papers there (…) and we then signed them for each other.

MW: Did the voting then also really happen there, or was the ballot marked separately so that they only had the witness papers at the pub?

I4: (…) (POOR CONNECTION) No-one’s interested in what the others vote for.

MW: Sure, but I’m like thinking about these steps, that the voting itself (…) has then happened in one place at one time, and then the witnessing at another place and time?

I4: Yeah.

MW: And this is what you did with you colleagues, too, or?

I4: Yeah.

MW: (…) You had to organize it all by yourself. How did that feel?

I4: It was all right. Better that way, actually, because then you can do it whenever and in peace, even in the middle of the night.

When assessing the physical and material aspects of the 31 postal voting accounts in the material used in this study against the official choreography of voting, the most striking difference is the aspect of mobility/immobility. Focusing on the act of voting, the instructional film is characterized by a nearly static atmosphere. In reality, many voters, even those applying the instructions conscientiously, carried the postal voting package from home to an external voting place, and those not voting in the presence of the witnesses could take the papers back and forth between the home and the individual meetings with the witnesses. The material realities of voting are less tidy than the model, and the postal voting form, in a way, underlines the materiality of voting. In a FAQ page provided by the Ministry, the role of the ballot envelope is explained almost lyrically: “In postal voting, the turquoize ballot envelope functions as the ballot box that, when sealed, keeps the ballot secret.” (Oikeusministeriö, 2020c). However, the ballot box metaphor does not consider the vulnerability related to the mundane transitions of the envelope that, in contrast to the ideal model, characterize the journey of many postal ballots. In other words, strongly focusing on the moment of the marking of the ballot as the Achilles’ heel of ballot secrecy may slightly divert attention from other relevant parts of the process.

As mentioned above in the context of the excerpt from Interview 4, the most common institutional/legal comments were the remarks that the witnesses did not quite understand in detail what they were attesting. This was not presented as a problem, rather a mere observation, a feature of the system, as in the quotation from the response 12 below. Sometimes, a slightly apologetic tone was discernible, as the voter would know it to be their responsibility to inform the witnesses. For accounts that reported, for instance, “I voted alone at home” (e.g., W2, I32), it was clear that although the voter had informed the witnesses, the idea of their oversight of the actual moment of marking the ballot paper had either not been communicated, or it was simply ignored in practice.

I live in a small town where no other Finns live. I thus asked my local friend and my husband’s sister to witness. None of them completely understood what they were signing, of course, as their English skills are not perfect, but they were all for it in any case (W12).

Judging from the interviews and written responses, it is likely that many witnesses considered their role to confirm that the voter had signed the cover letter and sealed their ballot envelope into the postal cover envelope. While this function of certification of identity (see Faulí et al., 2018, 49–50) is an essential part of the integrity of elections, it is not linked to the purposes of ballot secrecy, i.e., protecting voters from coercion and unintentional publicity of political opinion, and the system from vote-buying (see Elklit and Maley, 2019). Nothing about the cover letter procedure, as such, helps to establish those objectives. Yet, administratively speaking, it is indeed the appropriately filled cover letter that (partially) constitutes the validity of the vote according to the Elections Act (Vaalilaki, 1998, § 66 g). This highlights the discursive aspect of postal voting: a valid vote is made by proper words on the cover letter.

How the proper words are made to appear on the cover letter is a social process. None of the participants reported using notary or other paid legal services to witness but relied on their social networks. The voters navigated with two principles in choosing whom to invite: Who would trust them enough to sign this new kind of a document? And how could it be done with the least possible trouble to any of the parties? Those recruited for voting in homes were typically friends, neighbors, and/or relatives of one’s local spouse; voting at workplaces was motivated by the easy access to witnesses.

Some participants expressed awareness that they were asking for a favor and taking someone else’s time. Those who could at least partly rely on other Finns seemed to have had a more relaxed approach and could even celebrate their voting, such as by taking a photo of their voting letters at the mouth of the letterbox to be shared on social media. Also, office work environments with close collegial relations seem to facilitate finding witnesses. In addition to the differences in the reliability of postal services, access to potentially willing witnesses creates differences in how feasible a form of participation postal voting represents. This access may thus depend on a range of factors such as the length of stay in the area, stage in life or age, profession or type of work. Moreover, administrative cultures vary between countries so that people are faced with signing as a witness more frequently in some places than others. The social aspect of having to ask for a favor when the volunteer’s personal details are used should not be underestimated as an element characterizing and conditioning this form of voting.

I have never thought that the presence of an electoral official would protect my ballot secrecy (W10).

In the preparatory and legislative material, removing the act of voting from the reach of official oversight was presented as a foundational change only acceptable for an even higher principle of citizen equality. Installing the witness procedure into the postal voting rules appeared a possibility to downplay the radical difference between the forms of voting and maintain legitimacy: the voter would still not conduct the vote completely unguarded. While the witness procedure may have helped to maintain the legitimacy of the electoral system in the eyes of the electoral authorities and politicians, it is less clear how the relationship between the witness requirement, ballot secrecy and system legitimacy appears from a postal voter’s perspective. As Coleman, (2013, 192) points out: “Democratic legitimacy depends on a combination of manifest procedural fairness and deep subjective attachment.” Below, I discuss the participants’ accounts of the procedural fairness of the witness requirement and their relation to the electoral system in general. The variation in this respect was considerable—from the interviewee in the first quote below (I17) who appreciates the witness requirement despite its cumbersomeness; to the interviewee in the second quote (I29) who thinks it their personal responsibility to critique the system by refusing to ask anyone to witness.

I17: (…) That can be cumbersome again. But I think it’s required. I think those are the parts that are very, very essential to the transparency of the process and the honorability of the process. I think there are some pieces that you have to put layers on (…) So I like the extra layers.11

MW: In that situation when you were voting in the presence of those imaginary witnesses (WITH A LAUGH) (…) Did you think about it then that you are maintaining ballot secrecy?

I29: Well, I was mostly thinking that I felt vicarious embarrassment for the organization that created those paper slips and system. I thought about how estranged they are from life. I would like to emphasize that (DUE TO PROFESSIONAL AND EDUCATIONAL BACKGROUND) I am surely capable of a good moral reflection, and as I said at the beginning—a poor system won’t develop without a few ploys being used. So it was my responsibility, too.

I presented this study as a critical case, as the participants represented some of the most motivated to share their experience, most motivated to vote, and/or to contribute to social scientific research, thus an elite or an activist segment of a kind. If these participants were practicing ballot secrecy in ways different from the instruction and official choreography, it would be reasonable to expect the same to apply to those less motivated. Thus, the low share among the participants of those applying the official choreography in their postal voting implies that “voter-led arrangements” may well be widespread in the postal voting Finnish overseas electorate. If this should be the case, what does it imply for the state of ballot secrecy among overseas voters?

For the generations of postal voters who had previously voted by traditional means in the Finnish elections or were otherwise socialized into valuing highly the secrecy of elections, the small variations in where, when and with whom the marking of the ballot occurred, did not seem to matter much in terms of keeping their ballot secret. An analogous cultural code of conduct between a visit to a Finnish polling station and the moment of postal voting is reflected in a written response by a voter who had organized to vote with a friend:

We discussed the candidates before the day of voting but on the (self-selected) day of elections we no longer touched upon that. Ballot secrecy was kept the same way as any official polling station (W26).

Those applying “voter-led arrangements” seemed to judge the moment of voting so private that it was best conducted somewhere alone, whether in one’s home or private office. Although this understanding of voting as a private matter should not be taken for granted, as it develops socially and discursively as any other social norm or practice (Bertrand et al., 2006), the interviews and written responses did not give reason to believe that non-compliance with the rule of the presence of witnesses, as such, would imply non-compliance with ballot secrecy in terms of unintended disclosure of political opinion, voter coercion or vote-buying.

As concern was raised during the legal preparation of postal voting about the potential threat of coercion, the interviewees were also probed about this issue, asking how severe a problem they would consider it among the Finns abroad. Most responded with hesitation and difficulty to assess the issue. The most common assessment was that the direct pressure would be marginal; a few participants acknowledged the potential specifically as an issue of (physical or mental) violence in family relations and dependency on caregivers. The reasons given for the assumed marginality of the problem related to the participants’ understandings of Finns abroad as stereotypically “independent people”, “gender equal/civilized” or “married to foreigners not interested in Finnish politics”. It was more common to acknowledge that people influence one another’s electoral choices in a range of ways irrespective of the method of casting the ballot. Paraphrasing an interviewee, the logic here was that whether one’s partner is standing at one’s side nagging or whether they are in one’s head nagging, would not make much difference. In sensitive issues such as electoral coercion, it is difficult to judge what these elite or activist participants’ views reflect in a broader perspective.

The participants complaining about the witness requirement (see also Wass et al., 2021 in this special issue) focused mainly on how it burdens them practically and socially in terms for needing to ask for a favor, and they have difficulty seeing what value it adds to the process. From the perspective of ballot secrecy, however, it could also be highlighted how this practice designed to maintain the primary ballot secrecy, i.e., the immediate or mediated (e.g., photo) non-disclosure of the marked ballot, contradicts the secondary type of ballot secrecy, i.e., keeping the fact of participation/non-participation unknown to others (see Elklit and Maley, 2019, 64–65). The witness requirement obliges the voter to disclose their participation—and this disclosure is bound to have a socially different meaning from what takes place at a polling station where the voter and the election authorities do not know each other, or are at least separated from their daily roles by the official setting. The performance of voting, usually of a public and collective, even anonymous character, here becomes a performance for selected audiences that can consist of the two witnesses only or a larger pool of people:

Me and my work mate agreed on a date when we both took the postal voting form to the office. We asked (…) colleagues to witness (…). Frankly, I think we made quite a spectacle out of our voting, surely no-one in our landscape office was left unaware that we were voting at the Finnish parliamentary elections (W10).

The participants in this study did not report the disclosure as a negative experience—after all, they were mostly very proud about voting and happy to share information about Finland with their local friends. Other eligible voters might not feel equally enthusiastic, and we need to ask whether it is reasonable to compromise the secondary aspect of ballot secrecy to maintain a primary ballot secrecy procedure that many voters seem not to associate with keeping secrecy.

In this article, I approached overseas postal voting at the Finnish 2019 elections as a novel situation for the electorate in which they make sense of, interpret and apply the official rules and guidelines in their varying situations and contexts. I analyzed the written and oral accounts of postal voters from the perspectives of the physical/material, the institutional/legal, and the social, contrasting them with an analysis of an authoritative model. The focus of the analysis was on the witness requirement, adopted to ensure ballot secrecy and electoral freedom in the absence of the official oversight.

I found that a minority of the research participants had organized their postal voting exactly the way envisioned by the authorities, but exercised creativity (see Coleman, 2013, 15–18) that often meant marking the ballot elsewhere than under the witnesses’ nose. Despite this, the idea of ballot secrecy itself was not questioned or challenged by these participants. The empirical material did not imply that the participants would not have kept their ballot secret. As the participants represent highly motivated voters, keen to perform as good citizens, this finding does not necessarily mean that no problems of ballot secrecy exist in postal voting by Finns abroad. What it does suggest, as a critical case study (Flyvbjerg, 2001, 78–79) is that the witness requirement is not working in the way intended in securing the ballot, or in emphasizing its importance to the voters. Rather, it puts the overseas postal voters in a situation in which the secrecy of the fact of their participation is inevitably compromised among people they know.

With the purposes of primary ballot secrecy relating to guarding the privacy of political opinion, to protection from coercion and to prevention of vote-buying (Elklit and Maley, 2019), it is also relevant to ask if the self-organized voting situations would be secured this way if the witnesses were always present when the ballot was being marked. Several participants expressed some form of skepticism as to how aware the witnesses really were about what they were confirming by their signature and details in the cover letter. Would they have recognized a breach of ballot secrecy if they had witnessed one? One of the key factors in this respect is that the vote is not documented, and thus cannot be proved afterward. In the age of people routinely visually reporting their doings on social media, photographing the ballot represents the most likely liability in this regard. With the witnesses often representing the voter’s close friends, colleagues or relatives, one can question their willingness to interfere with taking a picture of the ballot. Instructions that are more direct and practical addressing what the witnesses are expected to observe and guard against might be useful. Instructions could also be developed both in terms of languages and modes of communication available. As to coercion, an interviewee pointed out that if one family member is in a position to coerce another, they are also likely to be able to organize the witnesses to be on their side.

Yet, removing the requirement through new legislation might not cause an immediate deterioration of the level of ballot secrecy overseas, but communicating about ballot secrecy would be the more important the longer the time since the introduction of the postal voting option. Based on this empirical material, it is not possible to conclude why ballot secrecy seemed intuitive and unquestioned for the participants. Currently, many voters still associate voting in Finnish elections with a polling station and a voting booth and may therefore comply with the ethos of secrecy, consciously or unconsciously. It remains an open question what will happen when more postal voters lack this cognitive scheme.

Variation in the degree of robustness of the postal connection between the voter's country of residence and Finland implies a structural inequality in the postal voting system. The findings from this study give reason to ask whether the current rules of conducting the postal vote also impose inequality between the voters with large networks of friends, colleagues and extended family and those with few relations characterized by trust. Those with access to networks have better opportunities for fulfilling the witness requirement with ease than those with few contacts. While one’s networks may grow with the years spent in the country of residence, the correlation between time and the likelihood of participating in Finnish elections is negative (Peltoniemi, 2018). In contrast, eligible voters who recently left Finland would be in a good position to participate in Finnish elections e.g., from the perspectives of party-political knowledge but might not feel confident enough in their social relations to cast a postal vote. This issue calls for further scrutiny.

The postal voting reform that was underway for several years deserves continued attention in order for it to be developed so that it guarantees both a high quality of elections at the state level and a meaningful voting procedure at the level of an individual voter. Experiences from the implementation of this reform may also serve to improve the electoral systems in Finland and elsewhere to meet the new exigencies related to health crises.

The anonymized empirical material generated for this study will be archived in the Finnish Social Science Data Archive after the end of the project in 2021. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to https://www.fsd.tuni.fi/en/.

Ethical approval was not provided for this study on human participants because it was not required by the University of Helsinki Ethical Review Board in Humanities and Social and Behavioral Sciences. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

The author was responsible for collecting the empirical material, analyzing it and writing the manuscript.

The research for this study was conducted within the project Facilitating Electoral Participation from Abroad (FACE), funded by the Finnish Cultural Foundation, project number 4706258.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author would like to thank her senior FACE teammates Hanna Wass, Johanna Peltoniemi and Miroslav Nemčok for their invaluable support, Kanerva Kuokkanen for the methodological discussions, and the two Frontiers reviewers for their detailed and constructive comments.

1Some participants live in countries in which postal voting is frequently used at various levels of the public administration. However, each postal voting system has its own rules and procedures, and due to the relatively uncommon witness requirement, it is likely that for many Finnish voters abroad, this particular procedure was new.

2The total number of interviews conducted was 32 and the number of written responses received 25. Here, input only from participants with personal experience of postal voting were included.

3The FACE survey (n = 2,100) invited a disproportionate stratified random sample of 10,000 Finnish citizens, registered as Finnish or Swedish speakers, entitled to vote at the 2019 parliamentary elections, to participate in May–September 2019 (Peltoniemi et al., 2019). The sample focused on the 17 largest Finnish diasporas. It was also possible to sign up for the survey without being invited, and approximately 40 individuals did so. The survey served as a basis of interviewee recruitment and, to some extent, the formulation of the interview guide.

4For instance, an interviewee had missed the prohibition of using one’s spouse as a witness. Giving the interviewer to believe their socio-economic and professional status to be relatively high, this interviewee was also politically active. They had close ties to Finland and no difficulties in reading the Finnish language instructions.

5The questions can be obtained from the author by request. The interview guide and the set of inspirational questions further contained questions not discussed here, related to the voter’s assessment of the trustworthiness of the system, and to the mundane vs. festive character of voting.

6Based on the view counter on the website on which the film can be watched (2,289 by 3 November 2020) and the number of valid postal votes cast at the 2019 parliamentary elections (6,183), I do not assume that the postal voters would have watched the instruction film. Among the ways of informing the voters about the new voting method, the film represents a holistic interpretation of the desired way for postal voting to proceed. In addition to direct links to the Elections Act, the film also contains elements that reflect common understandings of how voting should take place.

7The non-resident citizens’ turnout levels, remaining between 5.6 and 6.7% in the 1980s and 1990s, then to raise from 8.8% (2003) to 12.6% (2019) have had an effect in the total turnout between −2.9 and −5.3 percentage points in 1983–2019 (Tilastokeskus 2020).

8Personal Communication from Arto Jääskeläinen to Marjukka Weide. E-mail from address YXJ0by5qLmphYXNrZWxhaW5lbkBvbS5maQ== to bWFyanVra2Eud2VpZGVAaGVsc2lua2kuZmk=, 12.10.2020 9.25. VS: Kirjeäänestämisen valmistelu.

9The section 66 g, subsection 2 of the Elections Act (Vaalilaki, 1998) stipulates that a ballot from a ballot envelope that arrives open must not be counted. This provision was applied in practice at the 2019 elections (Jääskeläinen 2020).

10It is not clear from six written responses how exactly the voting had taken place.

11This quotation has not been translated as the interview was conducted in English.

Bäck, M., and Christensen, H. S. (2020). “Minkälaisia Poliittisia Osallistujia Suomalaiset Ovat Kansainvälisessä Vertailussa?” in Politiikan Ilmastonmuutos. Eduskuntavaalitutkimus 2019. Editors S. Borg, E. Kestilä-Kekkonen, and H. Wass, (Helsinki: Oikeusministeriö), 439–460.

Bertrand, R., Briquet, J.-L., and Pels, P. (2006). “Introduction. Towards a Historical Ethnography of Voting,” in Cultures of Voting. The Hidden History of the Secret Ballot. Editors R. Bertrand, J.-L. Briquet, and P. Pels, (London: Hurst), 1–15.

Bevir, M., and Rhodes, R. A. W. (2010). The State as Cultural Practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199580750.001.0001

Coleman, S. (2013). How Voters Feel. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9781139035354

Davies, B. (2010). Ludgate Hill Polling Station. Available at: https://issuu.com/bryandavies/docs/davies_bryan_polingstation (Accessed November 3, 2020).

Decker, C. (2016). Regulating Networks in Decline. J. Regul. Econ. 49 (3), 344–370. doi:10.1007/s11149-016-9300-z

Eduskunta (2017a). 5. Hallituksen esitys eduskunnalle laiksi vaalilain muuttamisesta. Täysistunto. PTK 94/2017 vp. 27.9.2017 klo 14.00—19.02. Helsinki: Eduskunta.

Eduskunta (2017b). 4. Hallituksen esitys eduskunnalle laiksi vaalilain muuttamisesta. Täysistunto. PTK 119/2017 vp. 16.11.2017 klo 15.59—18.49. Helsinki: Eduskunta.

Elklit, J., and Maley, M. (2019). Why Ballot Secrecy Still Matters. J. Democracy 30 (3), 61–75. doi:10.1353/jod.2019.0042

Engelen, B., and Nys, T. R. V. (2013). Against the Secret Ballot: Toward a New Proposal for Open Voting. Acta Polit. 48 (4), 490–507. doi:10.1057/ap.2013.10

Esaiasson, P., Persson, M., Gilljam, M., and Lindholm, T. (2019). Reconsidering the Role of Procedures for Decision Acceptance. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 49 (1), 291–314. doi:10.1017/s0007123416000508

Fagerlund, J., and Brander, S. (2013). Report on Finland. Revised and updated January 2013. Eudo Citizenship Observatory. San Domenico di Fiesole: European University Institute.

Faulí, C., Stewart, K., Porcu, F., Taylor, J., Theben, A., Baruch, B., et al. (2018). Study on the Benefits and Drawbacks of Remote Voting. Brussels: European Commission. Directorate-General for Justice and Consumers.

Flick, U. (2018). “Triangulation in Data Collection,” in The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Collection. Editor U. Flick (London: SAGE), 527–544. doi:10.4135/9781526416070.n34

Flyvbjerg, B. (2001). Making Social Science Matter: Why Social Inquiry Fails and How it Can Succeed Again. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511810503

Hallituksen Esitys Eduskunnalle Laiksi Vaalilain Muuttamisesta (2017). HE 101/2017 vp. Available at: https://www.eduskunta.fi/FI/vaski/KasittelytiedotValtiopaivaasia/Sivut/HE_101+2017.aspx (Accessed July 15, 2021).

Haraway, D. (2000). Birth of the Kennel: Cyborgs, Dogs and Companion Species. (Online lecture) Available at: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL1D9615FA85ED8B19 (Accessed November 15, 2020).

Hidén, M. (2017). HE 101/17 Vp laiksi vaalilain muuttamisesta. Perustuslakivaliokunta. 7.11.2017 kello 10.00.

Hollweg, B. (2014). How Voting Happens: Video-Essayistic Practice as Object-Oriented Fabulation. J. Media Pract. 15 (3), 157–175. doi:10.1080/14682753.2014.1000039

Hollweg, B. (2015). Political Sensibilities, Affect, and the Performative Space of Voting. Contemp. Theatre Rev. 25 (2), 177–189. doi:10.1080/10486801.2015.1020712

Jääskeläinen, A. (2017). Lausunto 7.11.2017. Perustuslakivaliokunnalle. Viite: hallituksen esitys laiksi vaalilain muuttamisesta (HE 101/2017vp.).

Junkkari, M. (2017). Vaalilain isä Lauri Tarasti tyrmää hallituksen kaavailut nettiäänestyksestä: Se tuhoaisi vaalisalaisuuden. Hs.fi, 8.4.2017. Helsinki: Helsingin SanomatAvailable at: https://www.hs.fi/politiikka/art-2000005161603.html. (Accessed November 15, 2020).

Kansanvalta 2007 -toimikunta (2005). Edustuksellinen demokratia. Kansanvalta 2007 -toimikunnan Mietintö. Helsinki: Oikeusministeriö.

Laki Vaalilain Muuttamisesta (2017). 939/2017 vp. Available at: https://finlex.fi/fi/laki/alkup/2017/20170939 (Accessed July 15, 2021).

Leino-Sandberg, P., Limnéll, J., and Wass, H. (2020). “Politiikan Ilmastonmuutos”. in Eduskuntavaalitutkimus 2019. Editors S. Borg, E. Kestilä-Kekkonen, and H. Wass, (Helsinki: Oikeusministeriö), 381–393.

Lipsky, M. (1980). Street-level Bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Services. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Mäenpää, O. (2017). Perustuslakivaliokunnalle. 7.11.2017. (HE101/2017 vp). Hallituksen esitys laiksi vaalilain muuttamisesta.

Manin, B. (2015). “Why Open Voting in General Elections Is Undesirable,” in Secrecy and Publicity in Votes and Debates. Editor J. Elster (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 209–214.

Ministeriöiden demokratiaverkosto, Aalto-Matturi, S., and Wilhelmsson, N. (2010). Demokratiapoliitikan suuntaviivat. Helsinki: Oikeusministeriö.

Morris, A. (2015). A Practical Introduction to In-Depth Interviewing. London: SAGE Publications. doi:10.4135/9781473921344 Ltd.

Oikeusministeriö (2006). Edustuksellinen demokratia. Lausuntotiivistelmä Kansanvalta 2007 -toimikunnan mietinnöstä. Helsinki: Oikeusministeriö.

Oikeusministeriö (2008). Sähköisen äänestyksen pilottihanke vuoden 2008 Kunnallisvaaleissa. Kokemuksia ja opittuja asioita. Muistio 30.9.2009. Helsinki: Oikeusministeriö.

Oikeusministeriö (2010). Lausuntoyhteenveto: Ulkosuomalaisten krjeäänestys. Muistio. 31.3.2010. Helsinki: Oikeusministeriö.

Oikeusministeriö (2016). Luonnos hallituksen esitykseksi vaalilain muuttamisesta (Kirjeäänestys). Helsinki: Oikeusministeriö.

Oikeusministeriö (2017). Nettiäänestyksen edellytykset Suomessa nettiäänestystyöryhmän loppuraportti. Helsinki: Oikeusministeriö.

Oikeusministeriö (2019). Kirjeäänestysohje. Helsinki: Oikeusministeriö Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dWJ4Z6Bhvvo&t=5s (Accessed November 3, 2020).

Oikeusministeriö (2020a). Eduskuntavaalit 2019/Äänioikeutetut/Koko Maa. Helsinki: Oikeusministeriö Available at: https://tulospalvelu.vaalit.fi/EKV-2019/fi/aoik_kokomaa.html (Accessed November 3, 2020).

Oikeusministeriö (2020b). Sähköinen Äänestäminen. Helsinki: OikeusministeriöAvailable at: https://vaalit.fi/sahkoinen-aanestaminen (Accessed November 3, 2020).

Oikeusministeriö (2020c). Usein kysytyt kysymykset. Helsinki: OikeusministeriöAvailable at: https://vaalit.fi/useinkysytytkysymyksetkirje (Accessed November 3, 2020).

Paasio, P., and Nordqvist, T. (2008). Kannanotto kirjeäänestysmuistioon 18.4.2008. Oikeusministeriölle. Helsinki: Ulkosuomalaisparlamentti.

Peltoniemi, J., Wass, H., and Weide, M. (2019). Facilitating Electoral Participation from Abroad (FACE) Survey Data, Helsinki: University of Helsinki.

Peltoniemi, J. (2018). On the Borderlines of Voting: Finnish Emigrants ́transnational Identities and Political Participation. Tampere: Tampere University Press.

Pesonen, P., Borg, S., and Sänkiaho, R. (1993). Vaalikansan äänivalta. Tutkimus eduskuntavaaleista ja valitsijakunnasta Suomen poliittisessa järjestelmässä. Porvoo: WSOY.

Przeworski, A. (2015). “Suffrage and Voting Secrecy in General Elections,” in Secrecy and Publicity in Votes and Debates. Editor J. Elster (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 97–107.

Reilly, J. L. (2017). Social Connectedness and Political Behavior. Res. Polit. 4, 205316801771917. doi:10.1177/2053168017719173

Rokkan, S. (1961). Mass Suffrage, Secret Voting and Political Participation. Arch. Europ. Sociol. 2 (1), 132–152. doi:10.1017/s0003975600000333

Salminen, O., and Wilhelsson, N. (2013). Valtioneuvoston demokratiapolitiikka 2002–2013. Katsaus ministeriöiden demokratiapolitiikan toteutuksiin. Helsinki: Oikeusministeriö.

Saurugger, S. (2010). The Social Construction of the Participatory Turn: The Emergence of a Norm in the European Union. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 49 (4), 471–495. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.2009.01905.x

Schwartz-Shea, P., and Yanow, D. (2012). Interpretive Research Design. Concepts and Processes. New York: Routledge.

Strandberg, T., and Castrén, S. (2017). Ulkosuomalaisparlamentin ja Suomi-Seura Ry:n lausunto eduskunnan perustuslakivaliokunnalle. Aihe: HE 101/2017 Vp, Hallituksen esitys eduskunnalle laiksi vaalilain muuttamisesta (kirjeäänestys). Helsinki: Ulkosuomalaisparlamentti ja Suomi-Seura ry.

Tarasti, L. (2017). Lausunto hallituksen esityksestä 101/2017 Vp vaalilain muuttamisesta (kirjeäänestys) 18.10.2017.

Teorell, J., Ziblatt, D., and Lehoucq, F. (2017). An Introduction to Special Issue. Comp. Polit. Stud. 50 (5), 531–554. doi:10.1177/0010414016641977

Tilastokeskus (2020). Tilastokeskuksen PxWeb-Tietokannat. Eduskuntavaalit 1983-2019, Äänestystiedot. Helsinki: Tilastokeskus.

Työministeriö (2006). Hallituksen ulkosuomalaispoliittinen ohjelma 2006-2011. Helsinki: Työministeriö.

Vaalilaki (1998). 2.10.1998/714. Available at: https://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/ajantasa/1998/19980714#O1L5a (Accessed July 15, 2021).

Valtioneuvosto (2014). VNS 3/2014 vp. Avoin ja yhdenvertainen osallistuminen. Valtioneuvoston demokratiapoliittinen selonteko 2014. Helsinki: Valtioneuvosto.

Valtioneuvoston demokratiaverkosto (2019). Demokratiapoliittisen toimintaohjelman loppuraportti. Helsinki: Oikeusministeriö.

Vandamme, P.-E. (2018). Voting Secrecy and the Right to Justification. Constellations 25 (3), 388–405. doi:10.1111/1467-8675.12278

Wagenaar, H. (2011). Meaning in Action: Interpretation and Dialogue in Policy Analysis. Armonk (N.Y.): M.E. Sharpe.