- 1Department of Political Science, Amsterdam Institute for Social Science Research (AISSR), University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands

- 2Institute of Political Science, Friedrich-Alexander-University Erlangen-Nuremberg, Erlangen, Germany

Resettlement and humanitarian admission programs claim to target ‘particularly vulnerable’, or ‘the most vulnerable’ refugees. If the limited spots of such programs are indeed foreseen for particularly vulnerable groups and individuals, as resettlement actors claim, how is vulnerability defined in policies and put into practice at the frontline? Taking European states’ recent admission programs under the EU-Turkey statement as an example, and focusing on Germany as an admission country, this research note sheds light on this question. Drawing on document analysis, and original fieldwork insights, we show that on paper and in practice vulnerability as a policy category designates some social groups as per se more vulnerable than others, rather than accounting for contingent reasons of vulnerability. In policy documents, the operational definition of vulnerability and its relation to other criteria remain largely undefined. In selection practices, additional criteria curtail a purely vulnerability-based selection, exacerbate existing or create new vulnerabilities in their own right. We conclude that, in the absence of clear definitions, resettlement and humanitarian admission programs’ declared focus on the most vulnerable remains a discretionary promise, with limited possibilities of political and legal scrutiny.

Introduction

Resettlement and humanitarian admission programs claim to target ‘particularly vulnerable’, or ‘the most vulnerable’ refugees. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) defines resettlement as the ‘selection and transfer of refugees from a State in which they have sought protection to a third State that has agreed to admit them–as refugees–with permanent residence status’ (UNHCR, 2020). Humanitarian admission programs are similar to resettlement but only provide a temporary residence status as they are often established more ad hoc and in reaction to concrete crisis situations. In both programs, usually together with the UNHCR, admission states in the Global North select a given number of refugees from countries of refuge and grant them legal and safe access to their territories and membership. However, access to this form of protection is scarce: worldwide, “less than one percent of all refugees are resettled each year” (ibid.). If these limited spots are indeed foreseen for particularly vulnerable groups and individuals, as resettlement actors claim, how is vulnerability defined in policies and put into practice at the frontline? Taking the European Union’s (EU) refugee admission programs under the EU-Turkey statement as an example and focusing on Germany as an admission state, this brief research report sheds light on the question of how vulnerability is defined in policies and assessed at the frontline. Drawing on document analysis and original fieldwork insights, we ask: what does the concept of vulnerability denote in refugee admission policies and practices?

Vulnerability has become a “new keyword” (Cole, 2016: 262), especially in the context of humanitarianism and migration governance. Access to humanitarian assistance – in countries of refuge, en route to Europe, as well as to asylum in the EU - has become increasingly linked to vulnerability criteria (see Janmyr and Mourad, 2018; Pearce and Lee, 2018; Hruschka and Leboeuf, 2019). As Latsoudi (2018) poignantly puts it, in Europe’s refugee regime “[we] are not talking about the right to asylum anymore, we are talking about the right to vulnerability”. At the same time, vulnerability has come to mean various things, if anything at all. Scrutinizing its meaning in the context of refugee admission policies is therefore crucial to examine who gets access to this particular form of protection.

The EU-Turkey statement of March 2016 has redirected many European countries’ resettlement efforts towards Turkey and linked them to migration control policies. Germany was one of the main driving forces behind the statement (Bialasiewicz and Maessen, 2018) and has one of the highest admission quotas, making the country a powerful force within Europe’s resettlement landscape (Welfens, 2018). Focusing on admissions from Turkey, and on Germany as a central admission country, thus offers a timely context to generate insights on ‘resettlement made in Europe’ (Fratzke and Beirens, 2020), and the construction of vulnerability.

Our analysis of vulnerability, as defined in policy documents and enacted at the frontline, points to two central findings. First, in policy documents, vulnerability works mostly as a static criterion, which defines some social groups as per se more vulnerable than others, while its operational use and relation to other criteria remain overall undefined. Likewise, in frontline assessments, some groups are seen to be per se more vulnerable than others and additional security and integration-related criteria exacerbate existing vulnerabilities and create new ones.

The structure of this brief research report is as follows. To start with, we outline theoretical insights on vulnerability and distinct interpretations of vulnerability in today’s refugee regime. After a brief overview of our methods, we present our analysis in two steps. First, we discuss formal definitions of vulnerability in key policy documents of the EU-Turkey statement and its implementation by Germany. Second, we provide empirical examples of how vulnerability is assessed across various frontlines, specifically, we analyze vulnerability assessments of NGOs and Turkish state authorities, UNHCR’s pre-selection processes, and German state authorities’ final selection.

Who is Vulnerable?

Both in scholarly and policy circles, the concept of vulnerability has proliferated. In principle, anyone or anything can be vulnerable, be it places, individuals or societies (Levine, 2004: 396). But what exactly does it mean to be vulnerable?

Seeking to answer this question, two main approaches have emerged. The first one considers particular groups as per se more vulnerable than others (Pankhurst, 1984). With more emphasis on structural than on situational circumstances, the vulnerability label in this case gets attached to certain groups. For instance, most famously Enloe, 1993 has shown how ‘womenandchildren’ often count as per se vulnerable groups (1993). The second approach, inspired by feminist scholarship (see Fineman, 2008; Butler, 2009; Cohn, 2014; Mackenzie et al., 2014), argues that all humans can be vulnerable depending on situational factors and contexts that create vulnerability. In contrast to the first approach, the focus here lies more on contingent causes rather than on symptoms of vulnerability (Clark, 2007: 284). In this understanding, men, women, and children can all be vulnerable depending on the situations that render them vulnerable (Turner, 2016).

In policies and practice of humanitarianism and forced displacement, vulnerability often serves as a static label to categorize some groups or individuals as vulnerable to grant them certain procedures, entitlements, or protection. However, there is not one unified understanding of vulnerability applicable across all policy and geographical contexts, and its definition remains contested. For instance, in its landmark decision in M.S.S. vs. Belgium and Greece, the European Court of Human Rights declared all asylum seekers to be a “particularly underprivileged and vulnerable population group in need of special protection” (International Journal of Refugee Law, 2011). However, later decisions have overturned this per se recognition of all persons seeking protection as vulnerable, lending more support to a groups-based approach, as is the case in the Common European Asylum System (CEAS) (Hudson, 2018). The Reception Conditions Directive of the CEAS, for instance, defines vulnerable persons as “minors, unaccompanied minors, disabled people, elderly people, pregnant women, single parents with minor children, victims of human trafficking, persons with serious illnesses, persons with mental disorders and persons who have been subjected to torture, rape or other serious forms of psychological, physical or sexual violence, such as victims of female genital mutilation” (European Union, 2013b). In addition, the Asylum Procedures Directive considers “gender, sexual orientation and gender identity” as grounds for special procedural guarantees (European Union, 2013a).

In resettlement and other refugee admission policies, a key reference point to define ‘who is vulnerable’ are UNHCR’s ‘resettlement submission categories’, namely “women and girls at risk [emphasis added]; survivors of violence and/or torture; refugees with legal and/or physical protection needs; refugees with medical needs or disabilities; children and adolescents at risk [emphasis added]; family reunification and persons with a lack of foreseeable alternative durable solutions” (UNHCR, 2011: 243). While attaching the vulnerability label partly to certain social groups, UNHCR’s criteria and their envisaged enactment also require context-specific interpretation and prioritizing. However, the discretionary nature of refugee admission programs allows states, and to some extent the EU, to formulate additional criteria and leaves ample scope for translating these formal criteria into frontline practices. In the following, we therefore examine the notion of vulnerability in policies and practices under the EU-Turkey statement, and its implementation by Germany as an admission country.

Methods

The empirical insights presented in this brief research report are based on two larger research projects, one looking at the concept of vulnerability in EU Admission Policy, the other one examining categorization practices in Germany’s humanitarian admission programs from Turkey and Lebanon. We draw on a close read of relevant policy documents of the EU’s cooperation with Turkey, as well as the first author’s ethnographic fieldwork of Germany’s admissions from Turkey conducted between October 2017 and January 2019. The data presented in this research note draws on interviews with German, Brussels- and Turkey-based resettlement actors and on four days of observations at UNCHR Turkey’s resettlement unit in November 2018. These interviews and observations focused on understanding the everyday practices of different resettlement actors, including discretionary decision-making as to who counts as vulnerable and subsequently gets prioritized for admission to a third country, such as Germany. Taking inspiration from Critical-Frame-Analysis (Verloo, 2005), we have analyzed our data with a focus on the ‘multiple meanings’ of vulnerability: what does the term mean in a particular context, and in what context is it used by particular actors?

Defining Vulnerability in the Eu-Turkey Statement

In their statement of March 18, 2016, the EU and Turkey outlined their intended actions to address the ‘migration crisis’ and to “end the irregular migration from Turkey to the EU” (European Council, 2015). In contrast to its cooperation with other third countries, the EU merely issued a press release of the EU-Turkey statement which limited EU-internal deliberation and potential legal scrutiny.

The EU-Turkey statement is known for the “one-to-one” mechanism. In short, this mechanism stipulates that the EU will admit one vulnerable Syrian refugee from Turkey for every person returned from the Greek islands to Turkey. The asylum seekers who arrive on the Greek islands by irregular means are subjected to a fast-track procedure and returned to Turkey if their asylum claim is deemed to be unfounded or inadmissible based on the EU’s premise that Turkey is a ‘safe third country’ despite serious human rights concerns and post-deportation risks (see e.g., Liempt et al., 2017; Masouridou and Kyprioti, 2018). However, people who are classified as vulnerable according to Greek legislation are exempted from returns to Turkey, which impelled the EU to urge Greece to “minimize numbers of migrants identified as vulnerable” (Human Rights Watch, 2017).

Admissions from Turkey are realized by means of resettlement and humanitarian admission programs. The statement foresees a voluntary humanitarian admission scheme, once the “irregular crossing between Turkey and the EU are ending or at least have been significantly reduced” (European Council, 2016), which further solidifies Turkey’s role as a buffer state. This also permeates selection criteria for admissions. According to the statement, admissions from Turkey would be based on the “UN vulnerability criteria”, i.e., UNHCR’s resettlement criteria, and prioritize persons who did not attempt to enter the EU irregularly. Documents on the standard operating procedures further define selection criteria. Admissions should not only focus on UNHCR’s criteria but also focus on “members of the nuclear family of a person legally resident in a Participating State.” Families with “complex or unclear profiles” are not eligible, the latter referring to polygamous families and underaged spouses (ibid). EU policy documents also prescribe in rather broad terms whom to exclude, even when found to be vulnerable: polygamous and underaged family constellations, those who tried to enter irregularly, and those considered to pose a threat to public policy, internal security and public health (cf. Council of the European Union, 2016). Thus, not only vulnerability criteria but also admission states’ preferences define the formal boundaries for access, however, without explicating the relation between vulnerability and other criteria or their respective assessment.

In addition, every EU member state is free to define additional selection priorities in national admission policies. For instance, Germany’s policy orders for its admissions implementing the EU-Turkey statement specify that admissions should focus on “the protection of the unity of the family; family ties or other ties beneficial to integration; integration capacities (educational background, job experience, language skills, young age); level of protection need, especially for cases that have not yet been assessed by the UNHCR; if applicable, additional criteria that the EU agreed upon with Turkey” (Bundesministerium des Inneren, für Bau und Heimat, 2020). Severe medical cases are limited to three percent of the total quota and persons who committed serious crimes are excluded from admissions (ibid.). Germany’s formal selection criteria illustrate that vulnerability is only one of many criteria admission countries use to distribute the limited places, next to state security-, integration- and capacity-oriented criteria.

Because of the variety of criteria present across different policy documents, with vulnerability’s role being nuanced, the question arises as to how different actors prioritize and select refugees at the frontline. The next section addresses this question.

Assessing Vulnerability in Practice

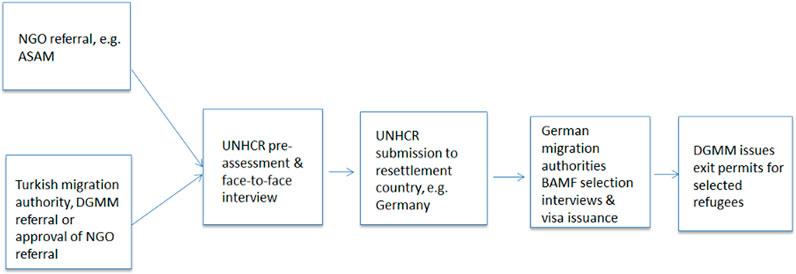

The way policies and operational documents define vulnerability is crucial for framing some groups as per se vulnerable and, thereby, as more in need of protection than others. However, it is only at the frontline of selection practices that policy categories shape refugees’ access to admission programs. In European states’ admissions from Turkey, the selection of refugees involves a number of different actors. Figure 1 serves as a simplified illustration of the selection process for Germany’s humanitarian admission program from Turkey, which largely resembles the process of other EU states.

FIGURE 1. Selection process for refugee admission programs from Turkey to Germany, based on fieldwork insights.

There are two main ways in which a case can be referred to UNHCR Turkey’s resettlement unit. Referrals of NGOs and UNHCR’s local offices must first be approved by the Turkish migration authority, Directorate General of Migration Management (DGMM), which also generates its own referrals for admissions to Europe. These DGMM-referred cases are further reviewed by UNHCR, who then proposes dossiers to admission states. The Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge, BAMF) conducts an in-person interview, followed by a security screening by German security authorities. To allow effective departure of those selected, the Turkish migration authority needs to issue exit permits for selected individuals. Vulnerability assessments matter throughout all phases of this process but not in a uniform way. Actors assess refugees’ vulnerabilities from different situated viewpoints and vulnerability criteria interact with a number of other considerations, as the following discussion of fieldwork insights illustrates.

Initial Referrals

In Turkey, similar to other countries of refuge, a variety of humanitarian actors register, administer and provide support to displaced populations. An integral part of their practice is the vulnerability or risk assessment, which takes stock of refugees’ legal, physical, economic and psychosocial needs and usually classifies cases as low, medium or high risk (Interview ASAM; Interview Red Crescent Turkey). As spots for admission are scarce, only cases that count as most at risk and whose needs cannot be addressed by available services in Turkey are, or should be, referred to UNHCR’s resettlement unit. Like in the broader context of humanitarian assistance and migration management, vulnerability criteria are grounded in and reproduce gendered assumptions of protection and risk (see e.g., UNHCR, 2009) (single) women and children, but also people with medical needs or disabilities and LGBTQI refugees count as those that are in need (Sözer, 2019), whereas (single) heterosexual men count as per se not vulnerable (Turner, 2019; Welfens and Bonjour, 2020).

The specificity of admissions from Turkey lies in Turkish state authority’s central role in initial referrals to UNHCR Turkey. DGMM both generates its own referrals and needs to approve all other referrals coming from NGOs or UNHCR local branches. In contrast to other admission programs where the involvement of countries of refuge is mostly limited to granting exit permits, Turkey claims a more active role in the process by de facto controlling who enters UNHCR’s resettlement process and who effectively leaves the country (İçduygu, 2015). At the protection desks of the Turkish migration authority, state officials assess vulnerability based on criteria such as medical needs, disability, women and children at risk (Interview DGMM). In practice, however, like in NGOs’ assessments, the focus lies mostly on women and children as the main vulnerable groups (see also Sözer, 2019).

Despite UNHCR’s efforts to harmonize the standards for resettlement submissions, inter alia with capacity building trainings (Fine, 2018), how exactly Turkish migration authorities decide who to refer for resettlement, remains opaque. For this reason, as well as to hold on to its authority as the ‘resettlement expert’ (Garnier, 2014), UNHCR reassess refugees’ vulnerability.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugee’s Assessment and Submission

The original task of UNHCR in countries of refuge is to identify and submit those cases that are most in need of admission to another state. In practice however, UNHCR’s resettlement unit has to take both Turkey’s and admission states’ additional policy priorities into account. The UNHCR internal process consists of three parts: the pre-assessment including an initial phone interview, an in-person interview, and the submission to admission countries (UNHCR, 2018). Assessing refugees’ vulnerability is an essential part in all of these three steps and yet only one of several aspects decisive for prioritizing a case for submission to a given program. For instance, in the initial phone interview UNHCR frontline worker reassess refugees’ vulnerabilities based on UNHCR’s resettlement handbook ‘resettlement submission categories’ (UNHCR, 2011) but also ask about refugees’ willingness to resettle, whether the complete nuclear family resides in Turkey, about family links outside of Turkey and documents such as identification documents, the military booklet or family booklets (Observations UNHCR Turkey).

Although always discretionary, the vulnerability assessments and classifications as low, medium or high follows UNHCR-wide standardized definitions and practices. As “women and girls at risk”, for instance, counts women and girls “who have protection problems particular to their gender, and lack effective protection normally provided by male family members. They may be: single heads of families, unaccompanied girls or women, or together with their male (or female) family members” (UNHCR, 2011: 263, emphasis in original). As in NGOs’ and Turkish state authorities’ referrals, vulnerability assessments rely to a large extent on gendered group-based assumptions of who is at risk and who is not (see also Welfens and Bonjour, 2020). In the subsequent in-person interview, UNHCR frontline interviewers and interpreters follow a detailed and routinized protocol of how to assess in more detail what exactly refugees’ past and present vulnerabilities consist of and what creates the need to be resettled to another country (see also Sandvik, 2005).

The main challenge in UNHCR practices is how to reconcile its mandated task to prioritize the ‘most vulnerable’ refugees while also addressing Turkey’s and admission countries’ additional priorities. For example, to make sure to not submit refugees Turkey prioritizes for citizenship - based on refugees’ economic potential -, UNHCR also inquires about refugees’ pending citizenship applications. In addition, DGMM’s gatekeeping power in the process forces UNHCR staff to ask for the authority’s approval for every change in the family composition, e.g., a marriage, newborn child, or death within the family (Observations UNHCR Turkey). Thereby, cases–even when already close to submission and deemed particularly vulnerable–can be put on hold or dropped completely. The emotional and practical uncertainties this creates for refugees exacerbates existing vulnerabilities and creates new ones in their own right.

To an even greater extent UNHCR needs to address and anticipate admission states’ selection priorities and practices, in particular the growing importance of security and integration-related criteria (Mourad and Kelsey, 2020). Among European admission countries, Germany has particularly stringent criteria, demanding identification documents, valid or expired, for all people above 15 years of age. In principle, refugees who lost their documents or turned 15 only after their arrival to Turkey can request or renew ID documents at the Syrian consulate in Istanbul. In practice, this option is not available to those who, financially, psychologically or physically, are unable to travel to Istanbul, pay the administrative fees and costs for brokers, or have fears of persecution upon direct encounter with Syrian state officials. Although UNHCR’s frontline staff are well aware that such requirements further marginalize those who are vulnerable, the fact that admission states have the final say in the process forces UNHCR to incorporate these aspects in its own assessment (Observations UNHCR Turkey).

Admission States’ Selection

Migration authorities of admission countries oversee the final selection. While all European admission countries claim to target particularly vulnerable refugees, their policies and practices also contain additional formal or informal selection criteria besides vulnerability, especially security and integration related selection criteria (Welfens and Pisarevskaya, 2020). Since all dossiers UNHCR submits to admission states count as ‘in need of resettlement’ because of their particular vulnerability, admission countries authorities mostly assess these additional criteria during their interviews. German migration authorities from the BAMF, for instance, go on regular field missions to Turkey to meet applicants in person (Interview BAMF). The rather strict document requirements and the medical cap of three percent for severely ill, create the paradoxical situation that UNHCR cannot submit more cases than the monthly quota of 500. Yet, while all admission candidates selected by UNHCR are deemed particularly vulnerable, not all of them will be admitted. There are three official reasons for rejecting a dossier: (1) security concerns; (2) serious concerns regarding integration; and (3) that refugees themselves resign (Observations UNHCR Turkey). While interviewers again inquire about admission candidates’ displacement experiences and situation in Turkey, at this step in the process, admission hinges on whether refugees are both at risk and not a risk for the admission country (Pallister-Wilkins, 2015). How exactly admission countries’ authorities assess the potential security threats refugees may pose and their ‘integration potential’ remains to a large extent opaque. The examples state or EU representatives give to illustrate the meaning of ‘integration potential’, or the supposed absence thereof, are questions on whether parents - and in particular, the father - would allow children to attend school or participate in mixed-gender swimming classes (Observations German Resettlement Expert Meeting 2018; see also Mourad and Kelsey, 2020). Other examples pertain to whether refugees are willing to be self-reliant or their reaction to same-sex couples kissing on the street (Interviews EU Commission; Interview EEAS/EASO). Yet, how exactly frontline workers decide in which cases integration potential counts as ‘too low’ for admission remains hidden from public scrutiny. As admission programs are humanitarian gestures and not grounded in human rights, admission countries have ample scope for discretionary decision-making.

Taken together, in putting admission policies into practice, different actors assess and reassess refugees’ vulnerabilities. Yet, the closer dossiers move towards the frontline of admission countries, the more additional criteria start to matter, partly creating and reinforcing refugees’ vulnerabilities. In the end, only those that admission states’ frontline officers find to be vulnerable and non-risky to the admission country will get access to the scarce spots for legal and safe access to protection in Europe.

Conclusion

This research report aimed to critically assess the meaning of vulnerability in policy and practice of refugee admissions under the EU-Turkey statement. Contrary to conceptualizations of vulnerability as universal to the human experience and created by dynamic circumstances, EU policies follow a static, group-based understanding of vulnerability. Rather than considering how interconnected threats and challenges can render persons vulnerable, vulnerability is attached to certain social groups. In addition, policy does not specify how vulnerability should be assessed in practice, or whether and how a focus on ‘particular vulnerable groups’ is monitored.

Similarly, frontline assessments regard some groups as per se more vulnerable than others while also allowing for discretionary decision-making. Yet, between Turkey’s and Germany’s more immigration-oriented considerations regarding refugees’ economic ‘worth’, security risks or cultural ‘fit’, vulnerability becomes only one of many criteria in determining access to admission programs. The proclaimed focus on vulnerability then obscures how other criteria trump vulnerability considerations or create vulnerabilities in their own right. In particular, the discretionary nature of admissions renders admission states’ practices and decision-making opaque, making the focus on vulnerability a political promise, which is difficult to scrutinize. In sum, ‘vulnerability’ in refugee admissions from Turkey remains a “buzzword” (Hruschka and Leboeuf, 2019) providing ample space for interpretation while falling short of verifying if and how those determined most in need – however defined – are taken care of.

Refugee admission programs are - in the most literal sense of the word – vital. They can save lives and offer those with pressing protection needs safe and legal access to places where these needs can be met. Yet, it is the restriction of refugees’ mobility and an increasingly exclusionary EU border regime that creates the need for such programs and the focus on vulnerability rather than human rights in the first place. This is not to discard vulnerability as a policy label altogether, but to call attention to the politics of its definition and enactment.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

Both authors listed have contributed substantially to this report and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Bialasiewicz, L., and Maessen, E. (2018). Scaling rights: the 'Turkey deal' and the divided geographies of European responsibility. Patterns Prejudice 52 (2–3), 210–230. doi:10.1080/0031322X.2018.1433009

Bundesministerium des Inneren, für Bau und Heimat (2020). Anordnung des Bundesministeriums Des Innern, für Bau und Heimat vom 13. Januar 2020 für die humanitäre Aufnahme gemäß § 23 Absatz 2 Aufenthaltsgesetz zur Aufnahme von Schutzbedürftigen aus der Türkei in Umsetzung der EU - Türkei Erklärung Vom 18. März 20. Berlin.

Clark, C. R. (2007). Understanding vulnerability: From categories to experiences of young Congolese people in Uganda. Child. Soc. 21, 284–296. doi:10.1111/j.1099-0860.2007.00100.x

Cohn, C. (2014). “Maternal thinking” and the concept of “vulnerability” in security paradigms, policies, and practices. J. Int. Polit. Theor. 10, 46–69. doi:10.1177/1755088213507186

Cole, A. (2016). All of us are vulnerable, but some are more vulnerable than others: the political ambiguity of vulnerability studies, an ambivalent critique. Crit. Horizons 17 (2), 260–277. doi:10.1080/14409917.2016.1153896

Council of the European Union (2016). Standard Operating Procedures implementing the mechanism for resettlement from Turkey to the EU as set out in the EU-Turkey Statement of 18 March 2016. Available at: https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-7462-2016-INIT/en/pdf (Accessed September 27, 2020).

Enloe, C. (1993). The morning after: Sexual politics at the end of the Cold War. Berkley: University of California Press.

European Council (2015). Justice and Home Affairs Council. Available at: http://europa.eu/!kX37JY (Accessed September 27, 2020).

European Council (2016). EU-Turkey statement, 18 March 2016. Available at: https://europa.eu/!Uk83Xp (Accessed September 27, 2020).

European Union (2013a). Directive 2013/32/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 June 2013 on common procedures for granting and withdrawing international protection. OJ L 180. Brussels: Official Journal of the European UnionAvailable at: http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2013/32/oj (Accessed September 27, 2020).

European Union (2013b). Directive 2013/33/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 June 2013 laying down standards for the reception of applicants for international protection. OJ L 180. Brussels: Official Journal of the European UnionAvailable at: http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2013/33/oj (Accessed September 27, 2020).

Fine, S. (2018). Borders and mobility in Turkey: Governing souls and states. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Fineman, M. (2008). The vulnerable subject: Anchoring equality in the human condition. Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/yjlf/vol20/iss1/2 (Accessed January 27, 2021).

Fratzke, S., and Beirens, H. (2020). The future of refugee resettlement: Made in Europe?. Available at: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/news/future-refugee-resettlement-made-in-europe (Accessed October 23, 2020).

Garnier, A. (2014). Migration management and humanitarian protection: the UNHCR’s ‘resettlement expansionism’ and its impact on policy-making in the EU and Australia. J. Ethnic Migration Stud. 40 (6), 942–959. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2013.855075

Hruschka, C., and Leboeuf, L. (2019). Vulnerability: a buzzword or a standard for migration governance?. Berlin: Max Planck Society / Population Europe.

Hudson, B. (2018). Migration in the mediterranean: exposing the limits of vulnerability at the European Court of human rights. Maritime Saf. Security L. J. 4, 26–46.

Human Rights Watch (2017). “EU/Greece: pressure to minimize numbers of migrants identified as ‘vulnerable’. Available at: https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/06/01/eu/greece-pressure-minimize-numbers-migrants-identified-vulnerable (Accessed September 27, 2020).

International Journal of Refugee Law (2011). M.S.S. V. Belgium and Greece European Court of human rights. Application No. 30696/09§251. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/anti-trafficking/legislation-and-case-law-case-law/case-mss-v-belgium-and-greece-application-no-3069609_en (Accessed September 27, 2020).

İçduygu, A. (2015). Syrian refugees in Turkey: The long road ahead. Washington; D. C.: Migration Policy Institute.

Janmyr, M., and Mourad, L. (2018). Categorising Syrians in Lebanon as, vulnerable. Available at: https://www.fmreview.org/syria2018/janmyr-mourad (Accessed September 27, 2020).

Latsoudi, E. (2018). Aegean laboratory - blueprint for the future European refugee policy?Refugee Protection in Europe. Phase-out Model or new beginning?, 18th Berlin conference on refugee protection. Available at: https://www.eaberlin.de/seminars/data/2018/pol/18-berliner-symposium-zum-fluechtlingsschutz/ (Accessed September 27, 2020).

Levine, C. (2004). The concept of vulnerability in disaster research. J. Traum. Stress 17 (5), 395–402. doi:10.1023/B:JOTS.0000048952.81894.f3

Liempt, I. v., Alpes, M. J., Hassan, S., Tunaboylu, S., Ulusoy, O., and Zoomers, A. (2017). Evidence-based assessment of migration deals: the case of the EU-Turkey Statement. Available at: https://migratiedeals.sites.uu.nl/wp-content/uploads/sites/273/2017/12/20171221-Final-Report-WOTRO.pdf (Accessed September 27, 2020).

Mackenzie, C., Rogers, W. A., and Dodds, S. (2014). Vulnerability: new essays in ethics and feminist philosophy. New York: Oxford University Press.

Masouridou, Y., and Kyprioti, E. (2018). The EU-Turkey statement and the Greek hotspots: a failed European pilot project in refugee policy. Available at: https://www.greens-efa.eu/en/article/press/new-study-shows-how-eu-turkey-deal-is-turning-refugees-into-detainees/ (Accessed September 27, 2020).

Mourad, L., and Norman, K. P. (2020). Transforming refugees into migrants: institutional change and the politics of international protection. Eur. J. Int. Relations 26 (3), 687–713. doi:10.1177/1354066119883688

Pallister-Wilkins, P. (2015). The humanitarian politics of European border policing: frontex and border police in evros. Int. Polit. Sociol. 9 (September), 53–69. doi:10.1111/ips.12076

Pankhurst, A. (1984). Vulnerable groups*. Disasters 8, 206–213. doi:10.1111/j.14677717.1984.tb00876.x10.1111/j.1467-7717.1984.tb00876.x |

Pearce, E., and Lee, B. (2018). From vulnerability to resilience: improving humanitarian response. Available at: https://www.fmreview.org/syria2018/pearce-lee (Accessed September 27, 2020).

Sandvik, K. B. (2005). “The physicality of legal consciousness: suffering and the production of credibility in refugee resettlement,” in Humanitarianism and suffering: The Mobilization of empathy. Editor D. Brown (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 223–244.

Sözer, H. (2019). Categories that blind us, categories that bind them: the deployment of vulnerability notion for Syrian refugees in Turkey. J. Refugee Stud. [Epub ahead of print]. doi:10.1093/jrs/fez020

Turner, L. (2016). Are Syrian men vulnerable too? Gendering the Syria refugee response. (U.N.H.C.R.)&text=Syrian%20men%20can%20be%20vulnerable%20too. Available at: https://www.mei.edu/publications/are-syrian-men-vulnerable-too-gendering-syria-refugee-response#:∼:text=Many%20humanitarian%20actors%20in%20the,Commissioner%20for%20Refugees'%20 (Accessed September 27, 2020).

Turner, L. (2019). The politics of labeling refugee men as ‘vulnerable’. Social Pol. Int. Stud. Gen. Stat. Soc. [Epub ahead of print]. doi:10.1093/sp/jxz033

UNHCR (2009). Guidance on the use of standardized specific needs codes. Available at: https://cms.emergency.unhcr.org/documents/11982/43248/Guidance+on+the+Use+of+Standardized+Specific+Needs+Codes+%28English%29/87b1febb-6331-4727-b196-d62d56a02adb (Accessed January 15, 2021).

UNHCR (2011). UNHCR Resettlement handbook. Available at: https://www.unhcr.org/46f7c0ee2.pdf (Accessed September 27, 2020).

UNHCR (2018). Resettlement in Turkey. Available at: https://www.unhcr.org/tr/wp-content/uploads/sites/14/2018/09/07.-UNHCR-Turkey-Resettlement-Fact-Sheet-August-2018.pdf (Accessed September 27, 2020).

UNHCR (2020). “Resettlement.” 2020. Available at: https://www.unhcr.org/resettlement.html (Accessed September 27, 2020).

Verloo, M. (2005). Mainstreaming gender equality in Europe. A critical frame analysis approach. Greek Rev. Soc. Res. 117, 11–34. doi:10.12681/grsr.9555

Welfens, N., and Bonjour, S. (2020). Families first? The mobilization of family norms in refugee resettlement. Int. Polit. Sociol. [Epub ahead of print]. doi:10.1093/ips/olaa022

Welfens, N., and Pisarevskaya, A. (2020). “The ‘others’ amongst ‘them’– selection categories in European resettlement and humanitarian admission programmes,” in European societies, Migration and the Law. The “others” amongst “Us”Moritz Jesse (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 81–104.

Welfens, N. (2018). Setting the trends for resettlement in Europe? Germany’s new avenues for refugee protection. Available at: https://rli.blogs.sas.ac.uk/2018/10/09/setting-the-trends-for-resettlement-in-europe-germanys-new-avenues-for-refugee-protection/ (Accessed October 23, 2020).

Keywords: vulnerability, resettlement, humanitarian admission program, EU-Turkey statement, Germany

Citation: Welfens N and Bekyol Y (2021) The Politics of Vulnerability in Refugee Admissions Under the EU-Turkey Statement. Front. Polit. Sci. 3:622921. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.622921

Received: 29 October 2020; Accepted: 09 February 2021;

Published: 08 April 2021.

Edited by:

Adele Garnier, Laval University, Quebec, CanadaReviewed by:

Nikolas Feith Tan, Danish Institute for Human Rights (DIHR), DenmarkMaja Janmyr, University of Oslo, Norway

Copyright © 2021 Welfens and Bekyol. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Natalie Welfens, bi5wLm0uci53ZWxmZW5zQHV2YS5ubA==

Natalie Welfens

Natalie Welfens Yasemin Bekyol

Yasemin Bekyol