- 1Study Area Politics and Governance, School of Governance, Law and Society, Tallinn University, Tallinn, Estonia

- 2Study Area Politics and Governance, Study Area of International Relations and Future Studies, School of Governance, Law and Society, Tallinn University, Tallinn, Estonia

Crises can function as catalysts for policy change, but change depends on multiple factors such as the actual content of the event, the agenda-setting power of the advocates of change, and their abilities to foster advocacy coalitions and break up policy monopolies. The COVID-19 crisis is an event that halted virtually all movement, including labor migration across the world, thus having great potential to act as a major focusing event. This article will look into the possibilities of this crisis to induce permanent labor migration policy change based on the case of Estonia. The article thus contributes to the literature on migration policy change from the Central and East European perspective.

Introduction

In the spring of 2020, most human mobility came to a halt, as states issued travel bans, entered state-of-emergencies or even full lockdowns due to the spread of the COVID-19 virus. These restrictions had a dramatic effect on labor migrants across the world (ILO, 2020). While the crisis prompted some countries to give easier labor market access to immigrants with skills needed for essential jobs, or even temporarily regularize irregular labor migrants, more countries decided to “pull up the drawbridge” and create new restrictions for labor immigration due to the negative economic effects of the lockdowns (Abella, 2020). The crisis is expected to have long-lasting effects on labor migration (Papademetriou and Hooper, 2020), thus making the COVID-19 pandemic a potential focusing event.

Focusing events are situations, which make policy-makers aware of a pre-existing problem (Atkinson, 2019) or help to set an agenda for the public opinion (Baumgartner and Jones, 2009) and thus, can contribute to policy change. In order to open a window for policy change, a focusing event needs to have a big effect, e.g., in terms of the number of people affected, the geographic extent of harm caused or be reoccurring, thus accumulating attention (Kingdon, 2003; Birkland, 2006; O'Donovan, 2017). Others have noted that focusing events ought to be attractive to the media and able to dissolve policy monopolies (Baumgartner and Jones, 2009).

Focusing events are often associated with migration policy change. For instance, the Great Depression of 1929, the Oil Crisis of 1973, the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the financial crisis of 2008 and many others are often seen as pathbreaking events followed by restrictions to labor immigration (see e.g., Koser, 2010). While the COVID-19 crisis differs from the above mentioned in many respects, there are at least two similarities which can be conducive to focusing events: the magnitude of the crisis and high probability of long-term effects. However, each crisis may have particular effects in different regions, and the question remains, how is this event utilized by political actors.

This paper outlines the pandemic-induced labor migration policy process in Estonia, a case interesting for two reasons. First, Estonia is a late liberalizer regarding labor migration policy. As in many Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries, the significance of immigrant labor force has increased only rather recently, and this labor migration policy context has not been investigated thoroughly yet. Secondly, the case of Estonia demonstrates a scenario much anticipated across Europe, where anti-immigrant parties get in charge of immigration policy. Since April 2019, the anti-immigrant Conservative People's Party of Estonia (EKRE) has been a junior partner in a conservative governing coalition. While EKRE had not been able to achieve substantial change in immigration policy in their first year in government, the COVID-19 pandemic was an opportunity to set the agenda for more restrictive labor migration policy.

Estonian Migration and Policy Context

Like most CEE nations (see e.g., Black et al., 2010), Estonia has been primarily a sending country in the global labor migration scene (Jakobson, 2020).

However, the resulting structural labor force shortages as well as the economic growth of the past years have increased the attractiveness of immigrant labor. Poland, Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovakia, Slovenia and Estonia have already become net-immigration countries, hosting notable numbers of labor migrants (see e.g., KCMD, 2020).

Estonia's immigration history has been somewhat traumatic—the Soviet time state-led immigration campaigns from other parts of the Soviet Union led newly independent Estonia to introduce an annual immigration quota of 0.1% of the resident population, i.e., 1,314 permits in 2020. However, its labor migration policy has become increasingly flexible and pragmatic over the more recent years. Although the number of residence permits for remunerated activities is still guarded by the quota and a wage criterion to avoid the usage of low skilled immigrant labor (foreign workers have to be paid at least the national average salary), numerous exceptions have been made to the quota to foster labor immigration with higher added value—e.g., start-up entrepreneurs, IT specialists, engineers, researchers, and highly skilled specialists who earn at least double the average salary, are exempt from the quota (Aliens' Act1 §115).

Since the quota ceased to meet the demand for labor force around 2016, temporary access to Estonian labor market was simplified by offering immigration counseling to migrants and host institutions and enabling third country nationals to work while holding a visa or being in Estonia based on a visa free regime, provided that they register their short-term employment with the Police and Border Guard Board (PBGB) and that they are paid at least the national average salary (1,404 euros per month in the first quarter of 2020—Statistics Estonia, 2020a). Since 2018, third country nationals can work in Estonia for up to 1 year in a 1.5-year time frame, when holding a D-visa (Aliens' Act1 §106, §60).

From 2017 onwards, when Estonia transposed the EU directive on seasonal migration (EC 2014/36/EU2), labor migrants can also come to Estonia as seasonal workers to work in select sectors (agriculture, forestry, fishing, food and non-alcoholic beverage production, hospitality and catering; Government Decree, 2017). While there is only a minimum salary threshold for seasonal workers, their employers have more obligations (e.g., providing housing, being obliged to pay the salary even if the contract is terminated prematurely) and the period of stay is also shorter (9 months during 1 year).

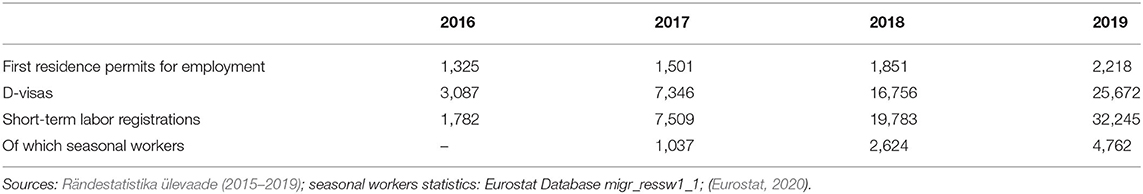

The reforms have resulted in a considerable increase of labor immigration, and most notably, of short-term labor mobility (see Table 1). The influence of the immigration quota on the number of first residence permits for remunerated activities is still evident, although the number of permits issued is almost double the size of the quota, meaning that the number of permits based on the exceptions is nearing the number of permits issued under the quota.

The liberalizations have been accompanied by reforms ensuring the reinforcement of migration management rules, e.g., correct registration of short-term labor migrants, ensuring that the salary requirement is met and taxes are paid from the labor migrants' salaries by increasing fines and other sanctions on employers evading these requirements. The first package of amendments was ratified in 2018, along with extending the duration of the D-visa and new exceptions to the immigration quota (Draft Law 6173).

While several preceding ministers of the interior overseeing immigration policy making had aimed both to reassure the relatively immigration-wary public and satisfy the advocacy coalition of employers, EKRE changed track. After becoming minister of the interior, the then chairman of the party Mart Helme likened immigrant labor to slave labor that is endangering Estonia as a nation state, attacked employers using migrant labor and declared that migrant workforce should be substituted by activating those permanent residents who are inactive in the labor market and bring Estonian labor migrants back from Finland (ERR, 2019a). Two months later he dismissed the immigration regulation working group, a body of public officials of related ministries, stakeholders and experts which had been tasked with proposing ideas for immigration regulation reforms (Ministry of the Interior, 2019), a step resembling what Baumgartner and Jones (2009) have termed breaking a policy monopoly. However, the minister did not attempt to establish an alternative policy monopoly in the form of an alternative working group, and most of Helme's attempts to change immigration legislation were blocked by other cabinet ministers (Delfi, 2019; ERR, 2019b). Eventually, Helme succeeded in making some amendments to migration regulation, which extended the enforcement regulations of 2018 also to rental labor from companies registered in other EU member states (Draft Law 1454), but did not impose any new restrictions.

Migration Policy Response to Covid-19

Estonia declared an emergency situation on March 12, 2020. Swiftly after that came the decisions to halt the issuing of visas to third country nationals, reintroduce border controls, close the border to everyone except Estonian citizens, permanent residents, the transporters of essential goods, repairers of essential equipment and those providing essential services (Government Decree, 2020). Subsequently, international air and sea travel largely stopped.

Those third country nationals who were already in Estonia could apply to extend their visa or residence permit until 31 August, 2020. In case they became unemployed or their period of short-term employment (365 days in the past 455 days) was exhausted, their visa was terminated prematurely [Aliens Act1 §52 (1)9], but they could remain in the country until 31 August, 2020. The amendments were made in order to avoid having to deal with a considerable number of irregularly staying immigrants later (Government Hearing Minutes, 2020).

While the European Commission had encouraged member states to treat seasonal workers as essential workers who should be allowed to travel (EC, 2020), Estonia kept its borders closed to them. EKRE ministers tried to reframe the ensuing debate by claiming that entrepreneurship models depending on cheap migrant labor are outdated and that employment of Estonians and returnees from Finland needed to be prioritized (Äripäev, 2020).

As the farming season was starting, the agricultural entrepreneurs became the most vocal critics of the restrictions. While labor migrants who were already in Estonia were allowed to find work or keep working in agriculture even if their visa had expired (EMN, 2020), this was not sufficient, as only few seasonal workers had arrived by March and many farmers had already prearranged contracts with their farm hands in Ukraine. The farmers claimed to be short of at least 2,000 seasonal workers. The unemployment level in Estonia did not increase notably, rising from 4.4% in the fourth quarter of 2019 to 7.1% in the second quarter of 2020 (Statistics Estonia, 2020b), and the farmers were skeptical of whether the recently unemployed would be willing to work in agriculture before fall (EPKK, 2020a). The demand for Estonian laborers in Finland even increased in some sectors, as e.g., many schools underwent renovations during the distance learning period, thus increasing demand for workers in the construction sector there and disincentivizing returning to Estonia (Helsingin Sanomat, 2020).

The farmers accused politicians of endangering the sustainability of domestic agriculture and brought the example from Finland where seasonal workers were allowed into the country despite travel restrictions as essential workers (EPKK, 2020b).

The COVID crisis did not bring consensus to the governing coalition over migration policy. Although Mart Helme came to the cabinet with ambitious plans for immigration restrictions, the cabinet was reluctant to approve them. While the Centre Party and Isamaa have rather been proponents of conservative migration policy, allowing EKRE to pursue with the reform would have brought political gains to EKRE exclusively, who is perceived as the issue owner by the society. By curbing EKRE's enthusiasm, the other two coalition partners could also make some political gains vis à vis the employers' and universities' advocacy coalitions EKRE refused to work with. Also, extensive restrictions on migration might have a negative effect on the already ailing economy. The short-term labor migrants have already become a notable group of tax payers and an indispensable labor force (ERR, 2019c) for many sectors, e.g., construction or farming, where the labor force demand was not affected by the COVID-19 crisis.

The government agreed to some enhanced regulations on study, family and labor migration, e.g., the obligation of the sponsor (e.g., the employer) to guarantee testing, transportation and a 14-day period of self-isolation of newly arrived immigrants before they can assume work, but also new restrictions on seasonal migration, i.e., a salary requirement for seasonal workers and the reduction of the time limit of seasonal work from 9 to 6 months per year (Postimees, 2020; Draft Law 617). However, there was one additional restriction not communicated by the government which had entered the draft law, namely, a restriction to third country nationals to work in most sectors based on a C-visa or visa-free stay (Draft Law 617). Thus, EKRE managed to take some additional steps toward restricting short-term labor migration to Estonia.

Discussion

The Estonian case demonstrates that while the COVID-19 crisis notably obstructed labor migration in 2020, its long-term impact is diminished by the fact that the crisis did not affect all sectors alike. Sectors where migrant labor is typical in Eastern Europe, e.g., construction, industry or farming, were not negatively affected. It might be speculated that some immigrant labor intensive sectors may even grow due increased emphasis on self-sustainability brought into focus by the pandemic, e.g., food security or independence from global production chains. However, the temporary restrictions still enabled EKRE to campaign for policy change and thus use the COVID-19 crisis as a focusing event.

Previous research has shown that often, political considerations have a bigger impact on immigration reforms as compared to the events themselves (Gsir et al., 2016). Similar conclusions can be drawn from the Estonian case: the nature of the COVID-19 crisis offers no direct reason for why restrictions were imposed on seasonal migration in particular. Political considerations are also reflected in the critical role other governing coalition partners played in hampering EKRE's ambitions in migration policy reform. The example also demonstrated that policy monopolies cannot be broken without proposing an alternative solution—during the crisis, the interest groups that previously voiced their interests in the working group, now did the same via the media, effectively challenging EKRE's attempts to reframe the debate. Yet, EKRE seems to have discovered the failing forward tactics for policy change (Scipioni, 2018), i.e., moving forward through incomplete agreements, creating conditions for the emergence of new crises, and via these reaching new concessions on their journey toward a more restrictive labor immigration policy.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: the Statistics Estonia online repository http://andmebaas.stat.ee/?lang=et; and the Eurostat Database https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database.

Author Contributions

M-LJ wrote most subchapters and edited the main body of the article. LK wrote the first version of the migration policy response chapter, contributed to the discussion, and copyedited the article. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research has been supported by the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under Grant Agreement No. 857366.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

1. ^RT I 2010, 3, 4; …; RT I, 10.07.2020, 4. 253 https://www.riigiteataja.ee/en/eli/521072020002/consolide (accessed August 14, 2020).

2. ^Directive 2014/36/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 February 2014 on the conditions of entry and stay of third-country nationals for the purpose of employment as seasonal workers. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/ALL/?uri=celex%3A32014L0036 (accessed August 15, 2020).

3. ^https://www.riigikogu.ee/tegevus/eelnoud/eelnou/9b435cf2-3c6d-44e9-85b1-6ef0dd90e67a/V%C3%A4lismaalaste%20seaduse%20muutmise%20ja%20sellega%20seonduvalt%20teiste%20seaduste%20muutmise%20seadus.

4. ^https://www.riigikogu.ee/tegevus/eelnoud/eelnou/7c3765b5-b4be-4fab-a037-1711e4603961/V%C3%A4lismaalaste%20seaduse%20tulumaksuseaduse%20ja%20maksukorralduse%20seaduse%20muutmise%20seadus%20(Eestis%20t%C3%B6%C3%B6tamise%20reeglite%20v%C3%A4%C3%A4rkasutuse%20v%C3%A4hendamine).

References

Abella, M.I. (2020). Commentary: labour migration policy dilemmas in the wake of COVID-19. Int. Migr. 58, 255–258. doi: 10.1111/imig.12746

Äripäev (2020). Helme välistööjõust: see pidu lõpeb ära. Available online at: https://www.aripaev.ee/uudised/2020/05/16/helme-valistoojoust-see-pidu-lopeb-ara (accessed August 15, 2020).

Atkinson, C.L. (2019). “Focus event and public policy,” in Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance, ed A. Farazmand (Cham: Springer), 1–5. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-31816-5_274-1

Baumgartner, F. R., and Jones, B. D. (2009). Agendas and Instability in American Politics. 2nd Edn. Chicago, IL; London: The University of Chicago Press. doi: 10.7208/chicago/9780226039534.001.0001

Birkland, T. A. (2006). Lessons of Disaster: Policy Change after Catastrophic Events. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

Black, R., Pantîru, C., Okólski, M., and Engbersen, G. (2010). A Continent Moving West? EU Enlargement and Labour Migration from Central and Eastern Europe. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. doi: 10.5117/9789089641564

Delfi (2019). Mart Helme algatatud välismaalaste seaduse eelnõu tabalised Tanel Kiige teravad kriitikanooled. Avaialble online at: https://www.delfi.ee/news/paevauudised/eesti/mart-helme-algatatud-valismaalaste-seaduse-eelnou-tabasid-tanel-kiige-teravad-kriitikanooled?id=87075139 (accessed August 10, 2020).

EC (2020) Communication from the Commission Guidelines Concerning the Exercise of the Free Movement of Workers During COVID-19 Outbreak 2020/C 102 I/03. Available online at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52020XC0330(03) (accessed August 15 2020).

EMN (2020). Working Document to Support the EMN Inform. Available online at: https://www.emn.ee/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/emn-inform-covid19-residence-permits-en.pdf (accessed August 15, 2020).

EPKK (2020a). Pöördumine. Available online at: http://epkk.ee/poordumine-valismaa-pollutoolised-tuleb-ka-eriolukorra-ajal-eestisse-lubada/ (accessed August 15, 2020).

EPKK (2020b). Avalik kiri maaeluministrile. Available online at: http://epkk.ee/pollumehed-maaeluminister-arvo-aller-tulge-kohe-tagasi/ (accessed August 15, 2020).

ERR (2019a). Mart Helme: Majandus peab olema tark, mitte orjatööjõul põhinev. Available online at: https://www.err.ee/928411/mart-helme-majandus-peab-olema-tark-mitte-orjatoojoul-pohinev (accessed April 09, 2019).

ERR (2019b). Keskerakondlastest ministrid ei kooskõlastanud Helme sisserände eelnõu. Available online at: https://www.err.ee/989466/keskerakondlastest-ministrid-ei-kooskolastanud-helme-sisserande-eelnou (accessed August 15, 2020).

ERR (2019c). Tööandjad on sunnitud üha enam välistööjõudu palkama. Available online at: https://www.err.ee/951262/tooandjad-on-sunnitud-uha-enam-valistoojoudu-palkama (accessed November 3, 2020).

Eurostat (2020). First Permits by Reason, Length of Validity and Citizenship (migr_resfirst). Available online at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database (accessed August 15, 2020).

Government Decree (2017). Hooajatööle esitatavad nõuded ja hooajast sõltuvate tegevusalade loetelu. Available online at: https://www.riigiteataja.ee/akt/117012017013 (accessed August 15, 2020).

Government Decree (2020). March 15 no 78. Temporary Restriction on Crossing the State Border Due to the Spread of the Coronavirus Causing the COVID-19 Disease. Available online at: https://www.riigiteataja.ee/en/eli/517032020004/consolide (accessed August 14, 2020).

Government Hearing Minutes (2020). Available online at: https://www.valitsus.ee/et/uudised/valitsuse-2420-istungi-kommenteeritud-paevakord (accessed August 10, 2020).

Gsir, S., Lafleur, J.-M., and Stanek, M. (2016). Migration policy reforms in the context of economic and political crises: the case of Belgium. J. Ethnic Migr. Stud. 42, 1651–1669. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2016.1162352

Helsingin Sanomat (2020). Matkustusrajoitukset iskevät vuokratyöntekijöihin rakennuksilla ja tehtaissa – “Virolaisia on vedottu pysymään Suomessa” Available online at: https://www.hs.fi/koti/art-2000006443915.html (accessed August 15, 2020).

ILO (2020). Policy Brief. Protecting Migrant Workers During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Geneva: ILO. Available online at: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_protect/—protrav/—migrant/documents/publication/wcms_743268.pdf (accessed August 15, 2020).

Jakobson, M.-L. (2020). Immigration to and Emigration from Estonia. Available online at: https://www.bpb.de/gesellschaft/migration/laenderprofile/308819/estonia (accessed November 2, 2020).

KCMD (2020). Immigration by Residence, Emigration by Residence. Dynamic Data Hub. Available online at: https://bluehub.jrc.ec.europa.eu/migration/app/ (accessed October 20, 2020).

Koser, K. (2010). The impact of the global financial crisis on international migration. Whitehead J. Diplomacy Int. Relat. 11, 13–20. Available online at: http://blogs.shu.edu/wp-content/blogs.dir/23/files/2012/05/04-Koser_Layout-11.pdf

Ministry of the Interior (2019). Sisserände Töörühm Lõpetab Tegevuse. Available onlne at: https://www.siseministeerium.ee/et/uudised/sisserande-tooruhm-lopetab-tegevuse (accessed November 25, 2020).

O'Donovan K. (2017) An assessment of aggregate focusing events, disaster experience, and policy change. Risk Hazards Crisis Public Policy 8, 201–219. doi: 10.1002/rhc3.12116.

Papademetriou, D.G., and Hooper, K. (2020). Commentary: how is COVID-19 reshaping labour migration? Int. Migr. 58, 259–262. doi: 10.1111/imig.12748

Postimees (2020). Intervjuu: EKRE esitas valitsuse plaaniga nõustumiseks oma tingimuse. Available online at: https://www.postimees.ee/7011378/ekre-esitas-valitsuse-plaaniga-noustumiseks-oma-tingimuse?fbclid=IwAR2YmVt1dhyl0FM1gN9ijpvoUeRb_36Kk7lsVmKXrPgzQgRoOVyDeyrJfTk (accessed November 2, 2020).

Rändestatistika ülevaade (2015–2019). Available online at: https://issuu.com/siseministeerium/docs/randestatistika_2015-2019_est (accessed August 13, 2020).

Scipioni, M. (2018) Failing forward in EU migration policy? EU integration after the 2015 asylum and migration crisis. J. Eur. Public Policy 25, 1357–1375. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2017.1325920.

Statistics Estonia (2020a). Keskmine brutokuupalk. Available online at: https://www.stat.ee/et/avasta-statistikat/valdkonnad/tooelu/palk-ja-toojoukulu/keskmine-brutokuupalk (accessed August 14, 2020)

Statistics Estonia (2020b). Töötuse määr. Available online at: https://www.stat.ee/et/avasta-statistikat/valdkonnad/tooelu/tooturg/tootuse-maar (accessed November 2, 2020).

Keywords: labor migration, migration policy, immigration, Estonia, COVID, politics of migration, focusing events, policy change

Citation: Jakobson M-L and Kalev L (2020) COVID-19 Crisis and Labor Migration Policy: A Perspective From Estonia. Front. Polit. Sci. 2:595407. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2020.595407

Received: 16 August 2020; Accepted: 16 November 2020;

Published: 10 December 2020.

Edited by:

Iris Goldner Lang, University of Zagreb, CroatiaReviewed by:

Michal Natorski, Maastricht University, NetherlandsKonrad Pȩdziwiatr, Kraków University of Economics, Poland

Copyright © 2020 Jakobson and Kalev. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mari-Liis Jakobson, bWFyaS1saWlzLmpha29ic29uQHRsdS5lZQ==

Mari-Liis Jakobson

Mari-Liis Jakobson Leif Kalev2

Leif Kalev2