95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

HYPOTHESIS AND THEORY article

Front. Polit. Sci. , 12 November 2020

Sec. Elections and Representation

Volume 2 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2020.584439

This article is part of the Research Topic Improving, Bypassing or Overcoming Representation? View all 11 articles

In response to the alleged legitimacy crisis, representative democracies have in recent years witnessed increased demands for democratic innovations aimed at giving citizens a more direct say in decision-making. Such initiatives, however, often rock the foundations of the model of representative democracy which assumes a more indirect link between citizens and political decisions, and which puts political power more firmly in the hands of elected representatives. In this paper, we study how these elected members of parliament (MPs)–who are key actors in representative democracy, yet potentially see their role reduced in deliberative or participatory models of democracy–think about democratic innovations. We study to what extent and why they support two common types of democratic innovations, namely referendums and deliberative events. While it is generally assumed that MPs' positions toward these initiatives are driven by their ideological predispositions, we propose and test a comprehensive framework which considers the role played by 3 “I's”: ideas, interests and institutions. Using original data from the PARTIREP MP survey, this paper maps variations in MPs' preferences for democratic innovations across 15 European countries, and shows that these variations can be explained by differences in MPs' ideological (left/right) views, legitimacy perceptions and role conceptions, their strategic position in government or opposition, and their electoral incentives. The 3I framework predicts MPs' support for both types of innovations, but more strongly so for referendums than for deliberative events.

The proliferation of democratic innovations in Western democracies has both complemented and challenged the predominantly representative nature of Western politics (Geißel and Joas, 2013; Grönlund et al., 2014). These democratic innovations aim to reinvigorate representative democracy by increasing and deepening citizen participation in the decision-making process, and by attempting to establish a more direct link between citizens and political outcomes (Smith, 2009). This logic of direct citizen participation in politics seems at odds with the prevailing representative logic of contemporary democracies, which assumes a more indirect link between citizens and political decisions, and which puts political power firmly in the hands of elected representatives. The latter, however, remain the ultimate gatekeepers and power brokers of modern politics and could therefore be reluctant to shift power from parliament to the people (Núñez et al., 2016), often resulting in democratic innovations' limited macro-level political impact (Goodin and Dryzek, 2006; Newton and Geißel, 2012; Bua, 2017; Font et al., 2018; Pogrebinschi and Ryan, 2018). The success and impact of democratic innovations thus depend in no small measure on whether these elected representatives are willing to relinquish some of their power to “ordinary” citizens. Understanding members of parliaments' positions toward democratic innovations is therefore essential to understanding their adoption and uptake.

Despite representatives' central role in adopting democratic innovations, remarkably little is known about their views and preferences on these innovations. In order to gain a better understanding of this, we study in this article how elected members of parliament (MPs) in 15 European democracies think about democratic innovations. Our central question is: To what extent and why do MPs support democratic innovations? Our focus in this article is on two of the most common types of democratic innovations, namely referendums and deliberative events (Smith, 2009).

To explain MPs' positions toward democratic innovations, we borrow a comprehensive framework from the policy sciences which focuses on ideas, interests, and institutions (Hall, 1997; Palier and Surel, 2005). This framework allows us to grasp why MPs are more or less likely to adopt democratic innovations by assessing the relative weight of each of the three I's. Additionally, this framework allows us not only to test the effect of several independent variables on a dependent variable, but also to more carefully theorize the relation between these independent variables (Hall, 1997; Palier and Surel, 2005). By proposing this 3I-framework, we move beyond the current state of the art, and complement previous studies on this topic which have conducted in-depth studies of one or two of these explanations separately or which have emphasized the role of “ideas” over “interests” and “institutions” (Bowler et al., 2006; Núñez et al., 2016).

Based on the 3I-framework, we hypothesize that MPs' support for democratic innovations will depend on: (1) their ideological considerations (left-right self-identification and party ideology), their legitimacy perceptions, and their representative role orientations (trustee vs. delegate roles), (2) their strategic interests (opposition vs. government dynamics, and perceived chances of re-election) and (3) the incentives offered by the broader institutional context (consensus vs. majoritarian institutions). These hypotheses will be tested using original survey data on individual MPs' democratic preferences, gathered by the comparative PARTIREP survey between 2008 and 2014 in 15 European countries. The study was conducted in 15 state-wide and 58 meso-level legislatures, which generates sufficient contextual variation to test the impact of the different variables in one model. The PARTIREP survey was kept constant across the 15 countries, which means that we can analyze information on the positions of more than 2.000 MPs using the exact same survey questions.

In doing so, this paper breaks new ground in two ways. On the one hand, we connect the explanatory framework from the policy sciences (the 3I framework) to the literature on democratic innovations. Usually, the literatures on public policy and on democratic innovations develop largely in isolation, but here we aim to explicitly link insights from the policy sciences to preferences on democratic reform. On the other hand, our focus on individual MPs in comparative perspective is also novel. Previous studies about democratic process preferences focus on individual citizens [see e.g., Gherghina and Geißel (2020); Ferrín and Kriesi (2016)], on parties (Núñez et al., 2016), or on MPs in single countries (Jacquet et al., 2020). We offer another level of analysis by explaining MPs preferences in a cross-national comparative perspective.

In the remainder of this paper, we first discuss the complex relation between democratic innovations and elected representatives. Next, we propose the main hypotheses guiding our model of ideas, interests and institutions. Afterwards, we outline our methodology and the operationalization of the variables. Finally, we report and discuss the results of our analysis, and draw more general conclusions.

The relationship between representative democracy and democratic innovations is complex. On the one hand, democratic innovations challenge the legitimacy and power of elected representatives. Because they give ordinary citizens a more direct say in political decision-making, they shake the foundations of the model of representative democracy which envisions a more indirect political role for citizens. On the other hand, democratic innovations also crucially depend on elected MPs (and other actors in the representative system) for their political uptake and their institutionalization within the political system. The origins of this difficult relationship can be traced back to the alleged crisis of representative democracy (Dalton and Weldon, 2005; Poguntke et al., 2016). Recent studies have reported a widespread dissatisfaction with the institution of representative democracy in advanced industrial democracies (Ferrín and Kriesi, 2016). Among the indicators of this critical stance are: declining party memberships (Van Haute et al., 2018), weaker party identification (Dalton, 2014), lower trust in parties (Dalton, 2004) and the rise of populist parties (Mudde, 2007; Kriesi and Pappas, 2015). This crisis proved to be fertile ground for a plethora of democratic innovations, ranging from participatory budgeting over deliberative mini-publics to direct legislation (Smith, 2009; Newton and Geißel, 2012; Elstub and Escobar, 2019). What unites all these innovations is their attempt to cure the ails of democracy with more democracy, in which “more democracy” stands for a more direct and participatory bond between citizen and government. This trend toward direct participation constitutes a paradigm shift with the indirect and representative logic in which MPs operate (Mudde, 2007; Kriesi and Pappas, 2015).

At first sight, elected representatives and democratic innovations do stand in a contentious relationship toward one another. Despite theoretical arguments made in defense of the normative value and deliberative potential of parliaments and parties (White and Ypi, 2011; Wolkenstein, 2016), the very foundations of democratic innovation are inevitably in conflict with the logic of representation and the role played by elected MPs in the democratic system. After all, one predominant rationale behind the recourse to democratic innovations is to free politics from the shackles of partisanship and to see what happens when ordinary citizens discuss and decide on political issues, unharmed by partisan considerations or the weight of the next election (Fishkin, 2018).

Besides these normative arguments, empirical research suggests that there is a correlation between citizens' dissatisfaction with “politics as usual” and their support for democratic innovations (Ferrín and Kriesi, 2016). Dalton (2004), finds an association between a preference for direct democracy and dissatisfaction with the current system. His results seem to be confirmed by the finding that participating in referendums in Switzerland leads to a lower probability of participating in demonstrations, which suggests that democratic innovations can ease political dissatisfaction (Fatke and Freitag, 2013). Similarly, Neblo et al. (2010) find that especially those citizens that are dissatisfied with partisan politics are keener on participating in deliberative forums. Other studies show that trust in political parties is correlated with satisfaction with the functioning of MPs and representative democracy (Miller and Listhaug, 1990; Dalton and Weldon, 2005). Democratic innovations are thus most supported among those that are unhappy with the functioning and legitimacy of elected representatives.

Nevertheless, this does not depict the complete picture. Democratic innovations do not only challenge representatives, they also paradoxically depend on them in two ways. First, representatives shape the public discourse about democratic innovations and their legitimacy. They have a prominent voice in the public debate, and their megaphone can considerably influence the discussion about democratic innovations. One illustration thereof is the G1000 citizen assembly in Belgium which several political parties discredited as an anti-representative, anti-political, and partisan enterprise. This framing delegitimized the citizen assembly and its results, while at the same time raising the threshold for future mini-publics (Caluwaerts and Reuchamps, 2015). In addition, research has shown that political elites play a key role in the structuring of public discourse about direct legislation. After all, referendums are not conducted in an aggregative vacuum and are preceded by a public debate in which the legitimacy of the procedure itself is often called into question (Budge, 2001).

Second, representatives of government parties are important actors in the political uptake of democratic innovations. Democratic innovations rarely have a direct impact, especially when they are not supported by the major institutions of representative democracy (Goodin and Dryzek, 2006). This lack of uptake is especially strong when representatives are uninvolved in the design of these innovations (Caluwaerts and Reuchamps, 2016). However, when representatives are too engaged in designing and organizing democratic innovations, some authors fear that they might instrumentalize them for their own interest (Klijn and Koppenjan, 2002). Representatives' skepticism about democratic innovations thus seems to correlate with the amount of influence they can exert on them. This is of crucial importance, as ultimately MPs will decide on the uptake of democratic innovations.

If democratic innovations are indeed intended to be workable institutional vehicles of participatory and deliberative aspirations, then we should take great interest in understanding the position of representatives toward democratic innovations. Previous studies have argued that a variety of factors can shape political actors' stance on this issue. These factors are often summarized as being linked to three “I's”: ideas, interests and institutions (Palier and Surel, 2005). The notion of “ideas” assumes that political actors' democratic process preferences will reflect their broader opinions, perceptions, viewpoints, and ideological considerations on the issue at stake. In this sense, MPs will only support democratic innovations if their general worldviews and political opinions are in line with the principles and values underpinning democratic reform. The notion of “interests” assumes that MPs' support for democratic innovations will depend on their own strategic calculations. If the rise of democratic innovations indeed causes a shift in power from the representative to the citizen, from the parliament to the people, then MPs will primarily support innovations if they have something to gain from it (or at least: if they do not expect to lose too much from it). The notion of “institutions” finally assumes that the institutional context in which MPs operate will convey certain norms about what constitutes “proper” behavior and what makes a democracy. These institutional rules and norms will in turn also shape MPs' viewpoints on democratic innovations.

The next sections discuss different explanations linked to the three “I's” in more detail and will also formulate several hypotheses which will be tested empirically in the remainder of the paper.

In a very general manner, the ideas underlying direct and deliberative democracy are grounded in a positive view on humankind and its potential for self-development. Supporters of participatory democracy reject the idea that citizens are mainly incompetent and incapable to govern themselves and society, and value principles such as self-determination, independence, and individual autonomy. They consider that democracy can empower citizens as autonomous, free, and capable individuals (Floridia, 2017). Perhaps unsurprisingly then, democratic innovations seem to have found a natural ally in left-wing ideologies. Several empirical studies have confirmed this assumption. Donovan and Karp (2006) showed for New Zealand, Norway, and Sweden a positive relation between left-wing attitudes and support for direct democracy. Only in Switzerland, there was a positive relation with right-wing attitudes. Hibbing and Theiss-Morse (2002) show a positive correlation between right-wing attitudes and a lower willingness to participate in politics in the United States. Results from Finland also confirm on the one hand the relationship between respondents with left-wing ideological affiliations and direct democracy, and on the other right-wing attitudes with support for stealth democracy (Bengtsson and Mattila, 2009). The same can be expected for support toward deliberative democracy. In a comment on the state of the field, Ryfe (2010, p. 1) observes that “anyone who circulates among deliberative practitioners knows that, ideologically, they tend to have a liberal progressive bent.”

This progressive bent can also be expected among representatives (whose views are ideally also congruent with their constituents). In general, one's position on the left-right dimension may affect one's position toward democratic reform. On the one hand, left-wing MPs are expected to be more positive toward democratic reform that contributes to an inclusive and egalitarian society. On the other hand, right-wing MPs, especially those who support a more conservative notion of maintaining the current institutional arrangements and social order will most likely oppose democratic reform of any kind (Bowler et al., 2002; Bol, 2016; Núñez et al., 2016). Hence, we assume that:

H1: Self-identified left-wing representatives are more supportive of democratic innovations compared to self-identified right-wing representatives

However, a simple left-right distinction might be insufficient to understand the possible effects of ideology. Post-materialist ideas and values might be equally important. MPs with underlying post-materialist values emphasize political self-expression and direct action (Bowler et al., 2006). Post-materialist attitudes are associated with left-wing ideological orientations in general, however, this is mostly embedded within green parties. As challenger parties (Doherty, 2005; Richardson and Rootes, 2006; Frankland et al., 2008), they are prominent supporters of democratic reform. One of their key distinctive features is their belief in grassroots democracy and aim to reinvigorate democracy by increasing referendums, public access to policymakers and decentralizing representative decision-making (Doherty, 2005). Hence, we expect that:

H2: Green representatives are more supportive of democratic innovations than other representatives

Radical right parties are also challengers of representative democracy; yet, differently so than green parties. The key ideological features of this party family–nativism, authoritarianism, and populism (Mudde, 2007)–clash with the ideological biases found in deliberative processes, i.e., liberalism, cosmopolitanism and social justice for all (Gastil et al., 2010). Hence, the proposed way to take back control from the elite to the people is not through deliberative fora, but rather through the introduction of plebiscitary democracy and referendums in specific. Such reforms are better suited to echo the preferences of the people without the elite intermingling (Mudde, 2007; Jacobs, 2018). We therefore expect radical right MPs to support referendums, but to oppose deliberative democratic innovations:

H3: Radical right representatives support referendums but oppose deliberative events

Ideational factors can also incentivize MPs to support democratic innovations in another way. Referendums and mini-publics are often presented as a cure for the malaise of representative democracy (Newton and Geißel, 2012). As such, support for these innovations might depend on MPs perceptions of that malaise, and of the extent to which referendums and mini-publics can close the gap between citizens and politicians. MPs might thus support democratic innovations for principled, ideological reasons, but also out of pragmatic perceptions of the severity of the democratic disconnect.

H4: MPs who perceive a large legitimacy gap will be more supportive of democratic innovations

Finally, and in addition to MPs' ideological considerations and their perceptions of the legitimacy gap, we also assume that representatives' role orientations will shape their views on democratic reforms. Thompson (2019) suggests that how MPs conceive and understand their role as representatives explains to what extent they will support citizens' input and democratic innovations. A classical and useful distinction can be drawn between “trustee” and “delegate” roles (Pitkin, 1967). Proponents of the trustee model argue that representatives should represent the common good through their own judgement, while advocates of the delegate model defend the idea that representatives should stay as close to their constituents' preferences as possible. Given that delegates' representational work strongly depends on their constituents' inputs, we can expect that the delegate model fits better with democratic innovations which empower citizens than the trustee model.

H5: Representatives who act as “delegates” are more supportive of democratic innovations compared to representatives acting as “trustees”

A second set of explanations relates to representatives' strategic interest. Deliberative events and referendums can be binding to various degrees but in general they imply a shift of power from the professional politician to the “lay” citizen (Vandamme et al., 2018). This shift in power is most likely to be supported by those who derive a strategic advantage from it (Bowler et al., 2006). We test two strategic considerations for MPs' views on democratic innovations, namely whether they belong to a government party or an opposition party, and their expectations for the next elections.

On the one hand, we expect that belonging to an opposition party positively affects representatives' support for democratic innovations. Representatives in the majority are more likely to support current electoral arrangements and resist institutional change (Boix, 1999; Pilet and Bol, 2011; Núñez et al., 2016). There are three main reasons for this: representatives' assessment of existing institutional arrangements, their evaluation of new avenues to influence governance, and their (un)willingness to take risks.

First, when representatives are confronted with institutional or democratic reform, they will first assess how advantageous the existing arrangements are to them. MPs belonging to the majority will resist change to democratic rules when these rules are beneficial to them. MPs in opposition, on the other hand will find themselves excluded from power and will try to weaken MPs in governing parties through changing the institutional status quo. They will support democratic innovations to distinguish themselves from the majority (Pilet and Bol, 2011).

A second reason is that democratic innovations provide additional avenues for political actors to influence the political system. Democratic innovations have a centrifugal effect on power and provide an opportunity for political forces outside of the governing elite to influence the political agenda Democratic innovations therefore not only restrain the power of ruling parties, they also provide an opportunity for opposition parties to exert influence (Leduc, 2003; Rahat, 2009; Altman, 2010). In this sense, they have the potential to be an important tool of what Rosanvallon and Goldhammer (2008) have famously called counter-democracy. Referendums and deliberative events can thus be strategically used to push an agenda that is not supported by those in power.

Finally, risk aversion plays an important role. Representatives belonging to government parties will tend to support the status quo, even if the new reform could potentially increase their gains (MacKuen et al., 1992; Pilet and Bol, 2011). In other words, the potential advantages of democratic reforms do not outweigh the actual advantages of the current institutional setting. After all, members of government parties attained power in the current institutional setting and are therefore less keen on changing it. In contrast, dissatisfied MPs in the opposition will be more willing to take risks since they hope that referendums and deliberative events will overcome the status quo and bypass governing elites. Hence, we assume that:

H6: Representatives of opposition parties are more supportive of democratic innovations than representatives of ruling parties

On the other hand, we also assume that representatives' expectations for the upcoming elections will shape their support for democratic innovations. When representatives feel electorally vulnerable and are unsure about their chances to win at the next elections, they will focus on limiting their electoral losses. To do so, they will likely take up and support proposals that are popular among public opinion. We assume that the support for democratic innovations was strong at the time of our survey. European countries were hit by the (aftermath of) economic crisis, which also affected democratic legitimacy. Citizens who became more dissatisfied with democracy (Armingeon and Guthmann, 2014; Cordero and Simón, 2016) are likely to decrease support for traditional politics and increase their support for new forms of citizen-based democracy (Neblo et al., 2010; Jäske, 2017; Bedock and Pilet, 2020). We can therefore expect that MPs anticipating an electoral defeat are more likely to support democratic innovations as it might enable them to gain electoral support (Bowler et al., 2007; Bengtsson and Mattila, 2009; Webb, 2013). From a strategic point of view, representatives will support democratic innovations when they fear not getting re-elected. We assume that:

H7: Representatives Who are unsure about their Re-election or fear electoral defeat are more supportive of democratic innovations

Institutions constitute a final determinant of representatives' support for democratic innovations. Scholars have argued that the institutional set-up of a country incentivizes certain kinds of politics over others (Hall, 1997; Palier and Surel, 2005). The extent to which power is shared in a democracy is widely acknowledged as a crucial institutional determinant (Vatter, 2000; Jäske, 2017). Of crucial importance in this regard is Lijphart's (1984) seminal distinction between majoritarian and consensus democracies. Its executive party dimension draws our focus to multi-party coalitions, decentralized government, and proportional electoral systems in the case of consensus democracies. In contrast, majoritarian democracies are characterized by a dominant executive, two-party systems, and majoritarian electoral systems.

We expect that MPs functioning in consensus democracies will welcome democratic innovations more than those functioning under majoritarian institutions. After all, both consensus democracies and democratic innovations are built on the principle of power sharing. The deliberative principles of inclusion, dialogue, and reason-giving seem to fit particularly well with the power sharing and cooperative mentality in consensus democracies (Steiner, 2009; Lijphart, 2019). Moreover, Lijphart (1984) argued that there is a strong link between cultural attitudes and structural institutions. The more proportional a system is, the more it forces political actors to come to a consensus. This creates a culture that resounds with the redistributive logic of democratic innovations and might foster a deliberative mindset among its representatives (Vatter and Bernauer, 2009).

There is some empirical support for the theoretical assumption that deliberation might thrive in consensus democracies. Steiner et al. (2004), for instance, find that discussions within parliaments in consensus democracies are more deliberative than these in majoritarian parliaments. Others show that consensus institutions advance deliberation in representative institutions (Bächtiger et al., 2005). Even though previous research on the occurrence of democratic innovations finds no clear link between the institutional system and the presence of democratic innovations in a country (Hendriks and Michels, 2011; Geißel and Michels, 2018), our aim is slightly different. We are interested in studying whether institutional incentives impact MPs' support of democratic innovations, which is different from their presence in specific democracies.

The literature dealing with institutional effects on referendums is nuanced, but suggests that much depends on who initiates the referendum and whether it is binding or not (Qvortrup, 2005; Setälä, 2006). While referendums, just like other innovations, disperse power from the executive elite to the people, this dynamic is much more outspoken in the case of bottom-up referendums than in the case of government-initiated referendums (Vatter, 2000; Vatter and Bernauer, 2009). Power sharing and a participatory culture lead to more bottom-up referendums. Additionally, the aggregative logic of referendums, as contrasted to the “talk” logic of deliberative events is arguably more in line with majoritarian systems (Geißel and Michels, 2018). Nevertheless, we will assume that generally speaking the power-sharing properties of a referendum will be more determinant than its aggregative logic, regardless of the referendum's initiator. We formulate the following hypothesis:

H8: Representatives in consensus democracies will be more supportive of democratic innovations than representatives in majoritarian systems

In order to answer the research questions and test the hypotheses, we use original data from the PARTIREP comparative MP survey (Deschouwer and Depauw, 2014; Deschouwer et al., 2014) in 15 European countries: Austria, Belgium, Germany, France, Hungary, Ireland, Israel, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Spain, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. The countries were selected to represent a wide institutional variation in terms of electoral systems (proportional representation, majority/plurality, and mixed-member systems), party systems (parliaments with strong and weak left-wing parties), and state structure (unitary and federal systems). The survey targeted members of all 15 state-wide parliaments as well as members of (a selection of) 58 regional assemblies in each of these countries. The selection of regions also reflected a careful balance of central and peripheral regions, regions with weak, and strong identities and regions with a strong left-wing or right-wing party presence.

The survey was organized by a team of international scholars from the 15 countries. All members of the selected parliaments were invited to complete a questionnaire online. The questionnaire was kept constant across the different languages. MPs who had not completed the survey after the initial invitation were re-contacted at least twice, except for those who had explicitly stated that they refused to participate in the project. In cases where response rates were disappointing, additional strategies were adopted to increase the response rate, such as the use of telephone reminders or face-to-face interviews. The use of a variety of methods depended on the international partners' estimation of “best practices” in the past. On average, one in four MPs responded to the survey. Supplementary Table A1 gives an overview of the response rates per country. There are no significant differences in response rates between men and women. Because some leftist parties were slightly over-represented in the dataset, we apply a weighting by parliamentary party group to correct for party differences. The MPs furthermore belong to a variety of party families, including socialist/social democratic, Christian democratic, liberal, conservative, regionalist, green, radical right, communist, agrarian, religious and single issue parties.

Our paper compares MPs' support for democratic innovations. In order to measure MPs' positions, we rely on the following survey question: “In recent years, different views on voters' distrust of politicians and political parties have inspired widely diverging suggestions for reform. Of each of the following directions that reform could take, could you indicate how desirable you consider them?”:

1. To increase the number of referendums

2. To increase the number of deliberative events, where groups of ordinary citizens debate and decide on particular issues.

The first item measures innovations through direct democracy whereas the second item measures innovations through deliberative democracy. We do consider direct democracy to be a democratic innovation, even though it has a long history in some countries (e.g., United States or Switzerland). However, we follow Smith's (2009, p. 111) argument that the referendum is an innovation because “in the institutional architecture of advanced industrial democracies, it tends to be used sparingly […] For most [governments], direct legislation is a relatively untried and untested form of governance.”

For each item, MPs had to indicate on a 4-point scale whether they considered those “not at all desirable,” “not very desirable,” “fairly desirable,” “very desirable.” MPs were asked to assess the desirability of each reform separately and were not asked to weigh one reform against another, or to consider potential trade-offs between different types of reforms. Because the survey question asked respondents to indicate the desirability of an increase in democratic innovations, their answers are possibly driven by the current situation in their country. In this view, Switzerland presents itself as a different case compared to the countries in the dataset, because of its frequent application of direct-democratic procedures on all levels of the Swiss federal state (Stojanović, 2006). We therefore conduct robustness checks (see below) in which we run models with and without Switzerland to test whether results are not driven by this particular country.

In order to explain varying levels of support for democratic innovations, we examine the impact of several independent variables, linked to the 3 Is. In order to measure MPs' ideas, we use three variables: MPs' left-right ideology, their party family and their role conceptions. MPs' left-right ideology is included in the PARTIREP survey as follows: “In politics, people sometimes talk of left and right. Using the following scale, where 0 means left and 10 means right where would you place our own views?.” This is a useful variable because it allows us to capture MPs' individual positioning (rather than that of their party). The downside is that this variable does not allows us to distinguish between different dimensions of “left” and “right.” We therefore use “party family” as a second proxy, given that we can expect that MPs take ideological cues from their party affiliations (Kam, 2009). Parties are categorized as belonging to one of the following eight party families: socialist/social democratic, Christian democratic, liberal, conservative, green/ecologist, radical right/anti-immigrant parties, regionalist/ethnic, and “other” parties. The “other parties” category puts together smaller party families in the survey, including communist, agrarian, religious, and single-issue parties. The socialist/social democratic family is the largest category and serves as the reference category. The international experts involved in the organization of the survey were in charge of the categorization of parties according to party family. Because MPs' left-right ideology correlates too strongly with party family (Pearson r = 0.524) we do not include these two variables in the same models, but run different models including each variable separately.

In order to measure MPs' perceptions of the legitimacy gap, we rely on the following survey question: “Most politicians are out of touch with people's concerns.” The answers were measured on a 5-point scale, ranging from “strongly disagree” (score 1) to “strongly agree” (score 5).

MPs' role conceptions are measured through the following survey question: “How should, in your opinion, a Member of Parliament vote if his/her own opinion on an issue does not correspond with the opinion of his/her voters? (1) The MP should vote according to his/her own opinion, (2) The MP should vote according to the opinion of his/her voters.” The first answer serves as a proxy for MPs' “trustee” role, the second answer serves as a proxy for the “delegate” role.

The three variables linked to MPs' ideas are all attitudinal variables, as is the dependent variable. Although this potentially creates endogeneity problems, we believe such problems are limited in our study. First, the dependent variables do not correlate strongly with the independent variables to begin with. The strongest correlation is found between “left-right ideology” and “support for deliberative events” (Pearson r = −0.275*). Second, the explanatory attitude “left-right ideology” in particular is of a different nature than the explained attitude “support for democratic innovations.” The first corresponds with MPs' deep-seated values, whereas the second refers to MPs' specific process preferences.

In order to measure MPs' interest-based considerations, we use two variables. The first is a dummy variable “majority/opposition status,” which distinguishes between MPs belonging to parties in government (score 0) or in opposition (score 1). The variable “electoral vulnerability” measures MPs' perceived re-election chances. The survey question asked: “If you were to decide to stand at the next general/regional elections, how confident do you feel you would be re-elected?.” The answer categories were: (1) I would surely be elected, (2) I would probably be elected, (3) It could go either way. This question was not included in Norway and the Netherlands because of the nearness of elections in those two countries (Deschouwer et al., 2014). For this reason, the variable will be included in a separate model, so that information from Norway and the Netherlands is not lost in the other models.

Finally, we measure the effect of “democratic institutions” through MPs' incentives generated by the electoral system. Even though we would have liked to have included all ten variables distinguishing consensus and majoritarian democracies, we were unable to find reliable data for the period 2008–2014. Moreover, even though the Comparative Political Data Set, 1960–2017 (Armingeon et al., 2019) does offer reliable composite variables for consensus and majoritarian democracies, they were not available for all countries in the PARTIREP dataset. We are aware that the electoral system is a mere proxy for type of democracy (consensus vs. majoritarian), but it is the one that best captures the power-sharing dimension of consensus democracies, that is central to our hypotheses (Lijphart, 2012). We use a dummy distinguishing between non-PR (majority/plurality, score 0) and PR electoral formula (score 1). The electoral system variable is measured at the parliament level, not the country level. This means that different parliaments in one country can receive a different score. This is the case in multi-level countries (e.g., in the United Kingdom and France, regional elections operate under different electoral formulas than federal elections). In mixed member systems (such as Germany and Hungary) the PARTIREP survey attributes different scores to MPs elected under different tiers.

Supplementary Table A2 gives an overview of the descriptives of the main dependent and independent variables.

In order to test the relative strength of ideas, interests and institutions in explaining support for democratic innovations, we ran a multivariate Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) including several control variables. At the individual level, we control for MPs' sex (male vs. female), age (in years), seniority (in years) and education (university vs. non-university education). At the parliament level, we control for type of parliament (regional vs. federal/national). Because individual MPs are nested in the parliamentary party group and in parliaments, the data are potentially hierarchically clustered. Ideally, we would have performed a multilevel analysis to account for the hierarchical clustering of the data but this was not possible due to the small number of cases at the highest level. We therefore include country fixed effects in the different models of the regression analyses. This is appropriate because none of the independent or control variables is measured at the country level.

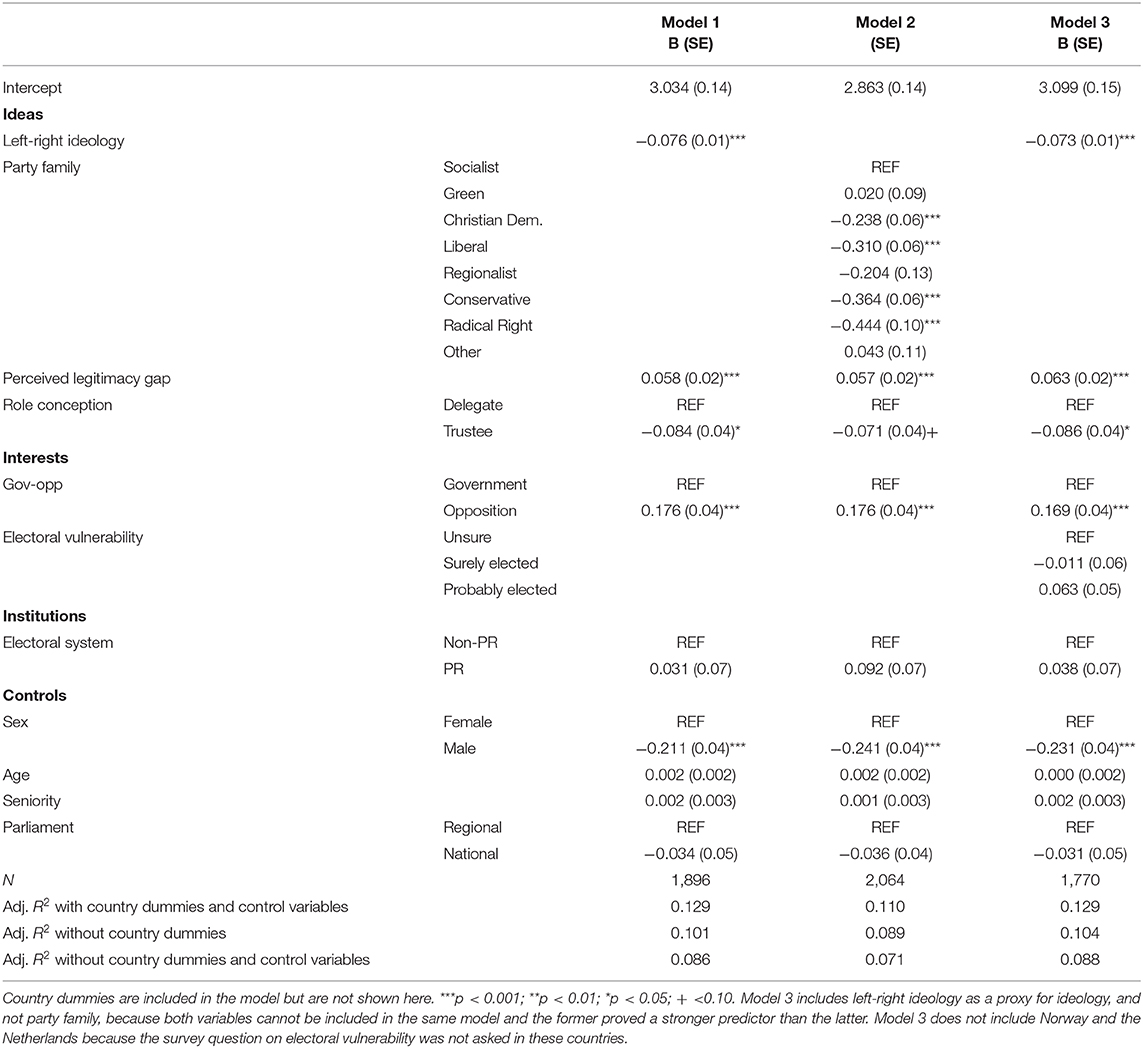

The results of the multivariate ANCOVA are reported in Table 1 (estimating support for referendums) and 2 (estimating support for deliberative events). Each Table includes three different models allowing us to assess the effect of different independent variables. The first two models include data from all 15 countries, and hence do not include the independent variable “electoral vulnerability” as data were unavailable for Norway and the Netherlands. The first model includes MPs' “left-right ideology” but excludes “party family” because of the relatively strong correlation between the two variables (cfr. supra). The second model includes “party family” but excludes “left-right ideology.” The effects of “electoral vulnerability” are tested in the third model. All models include control variables and country fixed effects.

From Table 1 it is clear that most of the independent variables have a significant and strong effect on MPs' support for referendums. When it comes to MPs' ideological considerations, “party family” in model 2 has a much stronger effect than “left-right ideology” in model 1. Changing only this variable, the explanatory power (R2) of the model increases from 20.1% in model 1 to 25.9% in model 2. Support for referendums indeed does not follow a simple left-right continuum, which encourages us to reject hypothesis H1. Whereas, center or right-wing parties like Christian democratic parties and liberal parties are more skeptical of referendums compared to socialist parties, more support is found among regionalist, radical right and even conservative parties. This provisionally confirms our hypothesis H3 that radical right parties might favor referendums as a way of giving voice to the people. The same argument might also extend to regionalist parties, who might support referendums as a means to advocate the right to regional self-determination. The effect for conservative parties is also positive, but the significant effect disappears after we exclude Switzerland in the robustness checks (cfr infra). This suggests that this effect was mostly driven by the Swiss case [see also: Donovan and Karp (2006) for similar findings on Switzerland], and that conservative parties outside of Switzerland are not necessarily more supportive of direct democracy. Finally, green parties are not more likely to support referendums than socialist parties, which rejects hypothesis H2.

In addition to ideology, the variables measuring MPs' “perceptions of the legitimacy gap” and “role conceptions” also present significant effects in all models. The directions of the effects are in line with our hypotheses. In line with H4 we find that MPs who more strongly agree that politicians are out of touch with people's concerns are more likely to support referendums. In line with H5, MPs who more strongly adhere to the “trustee” model—supporting the idea that representatives should prioritize their own personal opinions about the common good over those of their voters—are less in favor of referendums than MPs who consider themselves “delegates.”

Turning to the interest-based explanations, the results show that “government-oppositio” dynamics are a strong predictor of support for referendums. In line with our hypothesis H6, we find that support is much higher among those in the opposition than among members of government parties. This suggests that empowering citizens through referendums can act as a way for opposition members to side-line their political rivals in office. We tested separately whether this effect was moderated by the electoral system (not shown here), but this was not the case. In line with H7, MPs who are very sure of their re-election offer less support for referendums compared to MPs who are unsure about their chances to get re-elected. The former might have more to lose, or less to win, with the adoption of democratic innovations.

Finally, the variable electoral formula generates a significant effect. MPs operating under PR rules are more supportive of referendums than MPs operating under non-PR rules. This is in line with hypothesis H8 that power-sharing institutions, such as the electoral system, offer incentives to MPs and convey norms about the acceptability and desirability of democratic innovations. PR systems, arguably because they are more often adopted in countries where political institutions are designed to foster consensus and the inclusion of broader segments in society, encourage MPs to support initiatives that aim to directly involve citizens in decision-making.

The explanatory power of the different models in Table 1 is quite high, with R2 ranging between 20.1 and 26.4% for the full models, and between 11.7 and 15.9% for the models without country dummies and control variables. The control variables hardly increase the explanatory power of the models at all. After comparing the different effect sizes of the independent variables, we find that the idea-based and interest-based variables generate the strongest effects. The highest partial eta-squared in model 3 are found for party family (η 2= 0.078), the perceived legitimacy gap (η2 = 0.034) and opposition status (η2 = 0.017). Additional tests for diagnosing collinearity, performed on model 3 (as this was the model with the highest number of independent variables), revealed no problems with multicollinearity. The highest VIF score (VIF electoral system = 1.830) remains below value 10, and the lowest Tolerance rate (Tolerance electoral system = 0.546) remains much higher than 0.1 (Meyers et al., 2016).

When we compare the results in Table 2 to Table 1, it first of all becomes clear that the overall explanatory power of the models is lower in Table 2. The effects of the independent variables are somewhat weaker, indicating that the independent variables do a better job in estimating MPs' support for referendums than their support for deliberative events. One reason might be that deliberative events were less common than referendums in Europe at the time when the survey was conducted (OECD, 2020). Their unfamiliarity with deliberative models of democracy might have tempered MPs' support for deliberative events.

Table 2. General linear model estimating MPs' support for deliberative events (with country fixed effects).

When we test the idea-based hypotheses for MPs' support for deliberative events, the results are slightly different from what we found for referendums. MPs' self-placement on a left-right scale has a significant effect, in line with H1, with support decreasing when MPs position themselves more the right. This is mirrored in model 2 where the effect of party family is tested. Compared to socialist parties, green parties are equally likely to support deliberative events, but other party families (including Christian democratic, liberal, conservative and radical right parties) are less likely to find deliberative events desirable. The effect for regionalist parties is not significant. Together, these findings indicate that MPs' support for deliberative events is much more structured along a traditional and unidimensional left-right scale. Radical right parties, despite their stronger support for referendums, offer the lowest approval of deliberative events, which confirms H3. Additionally, MPs' perceptions of the legitimacy gap and their role orientations also play a role. The effects in Table 2 run parallel to the those in Table 1 but the effects are overall weaker. In line with H4, MPs who believe more strongly that politicians are out of touch with citizens find deliberative events more desirable. Trustees are also less likely to lend support to deliberative events than delegates, which confirms H5 that delegates, whose work is more directly linked to their constituents, would be more supportive of democratic innovations.

Regarding the interest-based explanations, we find that the “government-opposition” variable is the strongest predictor of support for deliberative democracy. In particular, we find–confirming hypothesis H6–that MPs from opposition parties are more supportive of deliberative innovations than those of parties in government. This again lends support to the assumption that those in power (and hence, those benefitting from the status quo) are less willing to share power with ordinary citizens and change the status quo. Regarding the variable “electoral vulnerability,” we hypothesized based on the classical electoral cycle that MPs would want to give voters what they wanted if they are unsure about their re-election prospects (H7). However, we find no support for this.

Finally, turning to the impact of the electoral system, the models reveal no significant differences between PR and non-PR systems, rejecting H8. To the extent that PR rules convey norms about inclusion, we find that they do not stretch to shape MPs' support for deliberative events. MPs operating under PR rules are equally likely to find deliberative events desirable compared to MPs in non-PR systems. Given the more limited power of the electoral system (and electoral vulnerability) in Table 2 compared to Table 1, we conclude that support for deliberative events is not driven by MPs' electoral incentives.

When we compare the different effect sizes of the independent variables, the idea-based and interest-based variables again appear to generate the strongest effects. This holds in particular for the variables “left-right ideology” (partial η2 = 0.050), “government-opposition” (partial η2 = 0.009) and “perceived gap” (partial η2 = 0.008). Collinearity diagnostics for the final model in Table 2 again did not reveal any problems with multicollinearity. The highest VIF score (VIF electoral system = 1.842) remains below value 10, and the lowest Tolerance rate (Tolerance electoral system = 0.543) remains higher than 0.1 (Meyers et al., 2016).

In order to strengthen the analyses, we conducted two additional robustness checks which are reported in the online Supplemental Materials file. The first check tests whether the results remain the same if we remove Switzerland from the analysis. Indeed, Switzerland presents itself as a slightly different case compared to the other countries in the dataset, because of its application of direct-democratic procedures (Stojanović, 2006). We therefore ran the models once more without Switzerland to test whether results were not driven by this particular country. The results are presented in Supplementary Table A3. Overall, the results remain largely the same compared to the results in Tables 1, 2, with the exception of the variable “party family” in the model estimating MPs' support for referendums. Radical right parties and regionalist parties continue to be more supportive of referendums than socialist parties if we remove Switzerland from the equation, but the significant effect for conservative parties disappears [see also: Donovan and Karp (2006)].

As a second robustness check, we also recoded the continuous dependent variable in Tables 1, 2 into a binary variable estimating MPs support (=1) compared to non-support (=0) for democratic innovations. Score 1 means that MPs find the proposed democratic innovations “fairly desirable” or “very desirable,” score 0 indicates that MPs find these “not at all desirable” or “not very desirable.” The results are reported in Supplementary Table A4. The results again confirm the initial results discussed in Tables 1, 2.

In response to the alleged legitimacy crisis, modern democracies have increasingly started to adopt democratic innovations as a way of reconnecting with citizens. These innovations aim to give “lay” citizens a more direct say in democratic decision-making, and therefore contrast with the indirect nature of representative democracy. In this paper, we asked whether and why elected representatives–as the ultimate political power brokers–support democratic innovations which both challenge and complement representative democracy. We hypothesized that 3Is–ideas, interests and institutions–account for MPs' positions toward democratic innovations. The findings of this paper paint a nuanced picture with several key findings.

First of all, we found that ideas are powerful indicators of support for democratic innovations. Ideological self-identification is significantly related to support for deliberative events and party family is significantly related to support for referendums. In particular, we found that left-wing parties (socialist and green parties) were most supportive of democratic innovations. However, we did not find any significant difference between green parties and other left-wing parties as expected in our second hypothesis. As expected, conservative, liberal and Christian democratic parties were less supportive of democratic innovations. Radical right parties were strongly against deliberation but strongly in favor of referendums, which proved in line with our expectations. Moreover, we found that MPs' own legitimacy perceptions are related to their support for democratic innovations. MPs who more believe that politicians are out of touch with citizens consider the adoption of more referendums and deliberative events desirable. This indeed suggests that MPs consider democratic innovations to be a cure to the malaise of representative democracy and a way or restoring legitimate processes of democratic linkage. In addition, representatives who consider themselves as “delegates” are more supportive of both referendums and deliberative events compared to representatives acting as “trustees.” This confirms our hypothesis that “trustees” are less supportive of citizen-empowering democratic innovations than “delegates.” This might be explained by the idea that trustees prefer to represent the people in an indirect way through their own deliberations in parliament, rather than by trusting citizens to directly make collective decisions amongst themselves (Pitkin, 1967).

Secondly, the strong effect of ideas does not mean that we should discount MPs' strategic interest, on the contrary. Representatives who are unsure about their re-election or fear electoral defeat, are more supportive of referendums, although not of deliberative events. Moreover, we found strong support for the expectation that MPs in majority parties are less supportive of referendums and deliberative events than members of opposition parties. Hence, our study shows that democratic innovations provide an opportunity to opposition members to side-line the majority (Goodwin and Milazzo, 2015). The findings furthermore suggest that representatives in opposition parties are more willing to employ democratic innovations as a powerful tool of “counter-democracy;” as a check on majority rule and to countervail the concentration of power (Rosanvallon and Goldhammer, 2008).

Thirdly, our analysis showed that institutions matter as well. MPs functioning under a system of proportional representation, i.e., MPs in consensus democracies, are more likely to support referendums but not deliberative events. The finding that there is an effect for referendums but not for deliberative events, could be explained by the fact that the rise of deliberative democratic innovations is a recent development and therefore not yet fully engrained in a specific institutional culture.

A final, transversal finding is that, while the 3I-framework predicts MPs' positions toward democratic innovations quite well, the 3Is generate slightly differential effects on support for referendums and deliberative events. Support for referendums is mainly affected by ideology, representative role orientations, government-opposition dynamics, electoral vulnerability, and the electoral system. Support for deliberative events is strongly determined by representatives' ideas as well, but the electoral system and electoral vulnerability, in contrast, do not significantly affect MPs' position toward deliberative events.

Despite these interesting findings, we should be aware of the limitations of our results. First of all, we took a rather static perspective in which we study whether MPs at one point in time support different democratic innovations. However, as a recent OECD (2020) report has shown, experience with democratic innovations has significantly increased in the last couple of years and an increasing number of innovations have been institutionalized. Even though our hypotheses were framed in a static manner, future research should take a more dynamic approach assuming that MPs views can change with growing experience. E.g., if conservative politicians experience that the recommendations of mini-publics are generally not that outlandish and revolutionary, they might become more inclined to support them over time. A more dynamic approach outlining changes in MPs positions over time might paint a more accurate picture. Moreover, despite the enduring tensions between representative democracy and democratic innovations, as the examples of institutionalization show, MPs are in some cases willing to adopt far-reaching reforms, which could fundamentally undermine their own power basis. Further research should examine these specific cases in more detail to see which set of ideas, interests and institutions led to their adoption.

A second limitation, is that the MP survey was administered from 2008 to 2012, whereas deliberative mini-publics as a democratic tool only gained recognition through several experiments organized during or after this period. The respondents' knowledge of the pros and cons of deliberative events might not have been fully crystallized, which accounts for the relatively low explained variance. Future research might contribute to this study by not only analyzing support for democratic innovations, but also MPs' knowledge about democratic innovations.

Thirdly, we were limited by the formulation of the questions in the survey, which did not allow us to distinguish between binding and advisory innovations. Previous research (e.g., Caluwaerts et al., 2020; Jacquet et al., 2020) found that the binding nature of the innovation matters greatly, with support for binding referendums or mini-publics being lower than for advisory ones. However, the formulation of the items in the questionnaire remains vague on this issue, in the sense that it is not clear whether the referendums or mini-publics needed to be binding or advisory. Future research should definitely distinguish between these modalities.

A final limitation consists of the fact that our operationalization of the institutional factors was fairly limited. The lack of readily available institutional variables for the period and the set of countries under investigation, means that we had to rely solely on the electoral system as a proxy. Even though our institutional hypotheses were largely confirmed, future research should include more institutional variation to map how democratic innovations interact with a country's institutional infrastructure.

Despite these limitations, our study shows that the support for democratic innovations can be explained by the 3I-framework. Democratic innovations have been increasingly stirring public opinion and will remain at the forefront of ideational, strategic and institutional struggles in years to come.

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. The PARTIREP MP Survey research team is owner of the data. The data are not stored in any online repository, but can be accessed upon request to a3Jpcy5kZXNjaG91d2VyQHZ1Yi5iZQ==.

JM and NJ focussed on the theoretical part of the paper. SE and DC focussed on the empirical analysis. All authors revised and finalized the paper together.

The data used in this publication were collected by the PARTIREP MP Survey research team. The PARTIREP project was funded by the Belgian Federal Science Policy (BELSPO—Grant No. P6/37). Neither the contributors to the data collection nor the sponsors of the project bear any responsibility for the analyses conducted or the interpretation of the results published here.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors would like to thank the PARTIREP MP Survey research team and all persons who have contributed to the data collection. They also wish to thank Julien Vrydagh for his contributions to, and Camille Bedock, Pierre-Etienne Vandamme and the reviewers for their comments on, earlier drafts of this paper.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2020.584439/full#supplementary-material

Armingeon, K., and Guthmann, K. (2014). Democracy in crisis? The declining support for national democracy in European countries, 2007–2011. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 53, 423–442. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12046

Armingeon, K., Wenger, V., Wiedemeier, F., Isler, C., Knöpfel, L., Weisstanner, D., et al. (2019). Comparative Political Data Set 1960-2017. Zurich: Institute of Political Science, University of Zurich.

Bächtiger, A., Spörndli, M., Steenbergen, M. R., and Steiner, J. (2005). The deliberative dimensions of legislatures. Acta Polit. 40, 225–238. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.ap.5500103

Bedock, C., and Pilet, J.-B. (2020). Enraged, engaged, or both? A study of the determinants of support for consultative vs. binding mini-publics. Representation. doi: 10.1080/00344893.2020.1778511. [Epub ahead of print].

Bengtsson, Å., and Mattila, M. (2009). Direct democracy and its critics: support for direct democracy and ‘stealth’ democracy in Finland. West Eur. Polit. 32, 1031–1048. doi: 10.1080/01402380903065256

Boix, C. (1999). Setting the rules of the game: the choice of electoral systems in advanced democracies. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 93, 609–624. doi: 10.2307/2585577

Bol, D. (2016). Electoral reform, values and party self-interest. Party Polit. 22, 93–104. doi: 10.1177/1354068813511590

Bowler, S., Donovan, T., and Karp, J. A. (2002). When might institutions change? Elite support for direct democracy in three nations. Polit. Res. Q 55, 731–754. doi: 10.1177/106591290205500401

Bowler, S., Donovan, T., and Karp, J. A. (2006). Why politicians like electoral institutions: self-interest, values, or ideology? J. Polit. 68, 434–446. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2508.2006.00418.x

Bowler, S., Donovan, T., and Karp, J. A. (2007). Enraged or engaged? Preferences for direct citizen participation in affluent democracies. Polit. Res. Q 60, 351–362. doi: 10.1177/1065912907304108

Bua, A. (2017). Scale and policy impact in participatory deliberative democracy: lessons from a multi-level process. Public Admin. 95, 160–177. doi: 10.1111/padm.12297

Budge, I. (2001). “Political parties in direct democracy,” in Referendum Democracy: Citizens, Elites and Deliberation in Referendum Campaigns, eds. M. Mendelsohn and A. Parkin (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan), 67–87.

Caluwaerts, D., Kern, A., Reuchamps, M., and Valcke, T. (2020). Between party democracy and citizen democracy: explaining attitudes of flemish local chairs towards democratic innovation. Polit. Low Countries 2, 192–213. doi: 10.5553/PLC/258999292020002002005

Caluwaerts, D., and Reuchamps, M. (2015). Strengthening democracy through bottom-up deliberation: an assessment of the internal legitimacy of the G1000 project. Acta Polit. 50, 151–170. doi: 10.1057/ap.2014.2

Caluwaerts, D., and Reuchamps, M. (2016). Generating democratic legitimacy through deliberative innovations: the role of embeddedness and disruptiveness. Representation 52, 13–27. doi: 10.1080/00344893.2016.1244111

Cordero, G., and Simón, P. (2016). Economic crisis and support for democracy in Europe. West Eur. Polit. 39, 305–325. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2015.1075767

Dalton, R. J. (2014). Interpreting partisan dealignment in Germany. German Polit. 23, 134–144. doi: 10.1080/09644008.2013.853040

Dalton, R. J., and Weldon, S. A. (2005). Public images of political parties: a necessary evil? West Eur. Polit. 28, 931–951. doi: 10.1080/01402380500310527

Deschouwer, K., and Depauw, S. (2014). Representing the People: a Survey Among Members of Statewide and Substate Parliaments. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Deschouwer, K., Depauw, S., and André, A. (2014). “Representing the people in parliaments,” in Representing the People. A Survey Among Members of Statewide and Substate Parliaments, eds. K. Deschouwer and S. Depauw (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 1–18.

Donovan, T., and Karp, J. A. (2006). Popular support for direct democracy. Party Polit. 12, 671–688. doi: 10.1177/1354068806066793

Elstub, S., and Escobar, O. (2019). Handbook of Democratic Innovation and Governance. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Fatke, M., and Freitag, M. (2013). Direct democracy: protest catalyst or protest alternative? Polit. Behav. 35, 237–260. doi: 10.1007/s11109-012-9194-0

Ferrín, M., and Kriesi, H. (2016). How Europeans View and Evaluate Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fishkin, J. S. (2018). Democracy When the People Are Thinking P: Revitalizing Our Politics Through Public Deliberation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Floridia, A. (2017). From Participation to Deliberation: A Critical Genealogy of Deliberative Democracy. Colchester: Ecpr Press.

Font, J., Smith, G., Galais, C., and Alarcon, P. (2018). Cherry-picking participation: explaining the fate of proposals from participatory processes. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 57, 615–636. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12248

Frankland, E. G., Lucardie, P., and Rihoux, B. (2008). Green Parties in Transition: The End of Grass-Roots Democracy? Surrey: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.

Gastil, J., Bacci, C., and Dollinger, M. (2010). Is deliberation neutral? patterns of attitude change during'the deliberative polls™'. J. Public Deliber. 6:3. doi: 10.16997/jdd.107

Geißel, B., and Joas, M. (2013). Participatory Democratic Innovations in Europe: Improving the Quality of Democracy? Berlin: Barbara Budrich.

Geißel, B., and Michels, A. (2018). Participatory developments in majoritarian and consensus democracies. Representation 54, 129–146. doi: 10.1080/00344893.2018.1495663

Gherghina, S., and Geißel, B. (2020). Support for direct and deliberative models of democracy in the UK: understanding the difference. Polit. Res. Exchange 2:1809474. doi: 10.1080/2474736X.2020.1809474

Goodin, R. E., and Dryzek, J. S. (2006). Deliberative impacts: the macro-political uptake of mini-publics. Polit. Soc. 34, 219–244. doi: 10.1177/0032329206288152

Goodwin, M., and Milazzo, C. (2015). UKIP: Inside the Campaign to Redraw the Map of British Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Grönlund, K., Bächtiger, A., and Setälä, M. (2014). Deliberative Mini-Publics: Involving Citizens in the Democratic Process. Colchester: ECPR Press.

Hall, P. A. (1997). “The role of interests, institutions, and ideas in the comparative political economy of the industrialized nations,” in Comparative Politics: Rationality, Culture, and Structure, eds. M. I. Lichbach and A. S. Zuckerman (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 174–207.

Hendriks, F., and Michels, A. (2011). Democracy transformed? Reforms in Britain and the Netherlands (1990–2010). Int J Public Admin. 34, 307–317. doi: 10.1080/01900692.2011.557815

Hibbing, J. R., and Theiss-Morse, E. (2002). Stealth Democracy: Americans' Beliefs About How Government Should Work. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Jacobs, K. (2018). Referendums in times of discontent. Acta Polit. 53, 489–495. doi: 10.1057/s41269-018-0116-y

Jacquet, V., Niessen, C., and Reuchamps, M. (2020). Sortition, its advocates and its critics: an empirical analysis of citizens' and MPs' support for random selection as a democratic reform proposal. Int. Polit. Sci. Rev. doi: 10.1177/0192512120949958. [Epub ahead of print].

Jäske, M. (2017). ‘Soft'forms of direct democracy: explaining the occurrence of referendum motions and advisory referendums in finnish local government. Swiss Polit. Sci. Rev. 23, 50–76. doi: 10.1111/spsr.12238

Kam, C. J. (2009). Party Discipline and Parliamentary Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Klijn, E.-H., and Koppenjan, J. F. (2002). “Rediscovering the citizen: new roles for politicians in interactive policy making,” in Public Participation and Innovations in Community Governance, ed. M. Peter (London: Routledge), 141–163.

Kriesi, H., and Pappas, T. S. (2015). “Populism in Europe during crisis: an introduction,” in Populism in the Shadow of the Great Recession, eds. H. Kriesi and T. S. Pappas (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 1–19.

Leduc, L. (2003). The Politics of Direct Democracy Referendums in Global Perspective. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.

Lijphart, A. (1984). Democracies: Patterns of Majoritarian and Consensus Government in Twenty-One Countries. Yale: Yale University Press.

Lijphart, A. (2012). Patterns of Democracy: Government Forms and Performance in Thirty-Six Countries. Yale: Yale University Press.

Lijphart, A. (2019). Deliberation and consociation: joint pathways to peace in divided societies. J. Deliber. Democr. 15, 1–2. doi: 10.16997/jdd.348

MacKuen, M. B., Erikson, R. S., and Stimson, J. A. (1992). Peasants or bankers? The American electorate and the U.S. economy. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 86, 597–611. doi: 10.2307/1964124

Meyers, L. S., Gamst, G., and Guarino, A. J. (2016). Applied Multivariate Research: Design and Interpretation. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Miller, A. H., and Listhaug, O. (1990). Political parties and confidence in government: a comparison of Norway, Sweden and the United States. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 20:2. doi: 10.1017/S0007123400005883

Neblo, M. A., Esterling, K. M., Kennedy, R. P., Lazer, D. M. J., and Sokhey, A. E. (2010). Who wants to deliberate—and why? Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 104, 566–583. doi: 10.1017/S0003055410000298

Newton, K., and Geißel, B. (2012). Evaluating Democratic Innovations: Curing the Democratic Malaise? New York: Routledge.

Núñez, L., Close, C., and Bedock, C. (2016). Changing democracy? Why inertia is winning over innovation. Representation 52, 341–357. doi: 10.1080/00344893.2017.1317656

OECD (2020). Innovative Citizen Participation and New Democratic Institutions: Catching the Deliberative Wave. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Palier, B., and Surel, Y. (2005). Les ≪trois I≫ et l'analyse de l'État en action. Revue Française Sci. Polit. 55, 7–32. doi: 10.3917/rfsp.551.0007

Pilet, J.-B., and Bol, D. (2011). Party preferences and electoral reform: how time in government affects the likelihood of supporting electoral change. West Eur. Polit. 34, 568–586. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2011.555984

Pogrebinschi, T., and Ryan, M. (2018). Moving beyond input legitimacy: when do democratic innovations affect policy making? Eur. J. Polit. Res. 57, 135–152. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12219

Poguntke, T., Scarrow, S. E., Webb, P. D., Allern, E. H., Aylott, N., Van Biezen, I., et al. (2016). Party rules, party resources and the politics of parliamentary democracies: how parties organize in the 21st century. Party Polit. 22, 661–678. doi: 10.1177/1354068816662493

Qvortrup, M. (2005). A Comparative Study of Referendums: Government by the People. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Rahat, G. (2009). “Elite motivations for initiating referendums: avoidance, addition and contradiction,” in Referendums and Representative Democracy: Responsiveness, Accountability and Deliberation, eds. M. Setälä and T. Schiller (London: Routledge), 98–116.

Richardson, D., and Rootes, C. (2006). The Green Challenge: The Development of Green Parties in Europe. New York, NY: Routledge.

Rosanvallon, P., and Goldhammer, A. (2008). Counter-Democracy: Politics in an Age of Distrust. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ryfe, D. M. (2010). Comment: a step forward on a vital issue. J. Public Deliber. 6:2. doi: 10.16997/jdd.106

Setälä, M. (2006). On the problems of responsibility and accountability in referendums. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 45, 699–721. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2006.00630.x

Smith, G. (2009). Democratic Innovations: Designing Institutions for Citizen Participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Steiner, J. (2009). “In search of the consociational “spirit of accommodation”,” in Consociational Theory: McGarry and O'Leary and the Northern Ireland Conflict, ed. R. Taylor (New York: Routledge), 196–205.

Steiner, J., Bächtiger, A., Spörndli, M., and Steenbergen, M. R. (2004). Deliberative Politics in Action: Analyzing Parliamentary Discourse. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Stojanović, N. (2006). Do multicultural democracies really require PR? Counterevidence from Switzerland. Swiss Polit. Sci. Rev. 12, 131–157. doi: 10.1002/j.1662-6370.2006.tb00063.x

Thompson, N. (2019). “The role of elected representatives in democratic innovations,” in Handbook of Democratic Innovation and Governance, eds. S. Elstub and O. Escobar (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing).

Van Haute, E., Paulis, E., and Sierens, V. (2018). Assessing party membership figures: the MAPP dataset. Eur. Polit. Sci. 17, 366–377. doi: 10.1057/s41304-016-0098-z

Vandamme, P.-É., Jacquet, V., Niessen, C., Pitseys, J., and Reuchamps, M. (2018). Intercameral relations in a bicameral elected and sortition legislature. Polit. Soc. 46, 381–400. doi: 10.1177/0032329218789890

Vatter, A. (2000). Consensus and direct democracy: conceptual and empirical linkages. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 38, 171–192. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.00531

Vatter, A., and Bernauer, J. (2009). The missing dimension of democracy: institutional patterns in 25 EU member states between 1997 and 2006. Eur. Union Polit. 10, 335–359. doi: 10.1177/1465116509337828

Webb, P. (2013). Who is willing to participate? Dissatisfied democrats, stealth democrats and populists in the United Kingdom. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 52, 747–772. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12021

White, J., and Ypi, L. (2011). On partisan political justification. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 105, 381–396. doi: 10.1017/S0003055411000074

Keywords: democratic innovations, members of parliament, citizen participartion, direct democracy, deliberative democracy, comparative survey research

Citation: Junius N, Matthieu J, Caluwaerts D and Erzeel S (2020) Is It Interests, Ideas or Institutions? Explaining Elected Representatives' Positions Toward Democratic Innovations in 15 European Countries. Front. Polit. Sci. 2:584439. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2020.584439

Received: 17 July 2020; Accepted: 14 October 2020;

Published: 12 November 2020.

Edited by:

Jean-Benoit Pilet, Université libre de Bruxelles, BelgiumReviewed by:

Wouter Van Der Brug, University of Amsterdam, NetherlandsCopyright © 2020 Junius, Matthieu, Caluwaerts and Erzeel. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nino Junius, Tmluby5KdW5pdXNAdnViLmJl

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.