- Faculty of Political Science, University of Iceland, Reykjavík, Iceland

The sudden rise and subsequent radicalization of the “Alternative for Germany” (AfD) has been one of the politically most important consequences of the Eurozone debt crisis in Germany, both in relation to domestic politics and in the broader context of European-level right-wing populism. While initially founded as a single-issue party in opposition to Angela Merkel's claim that there was no alternative to saving the common currency, the party quickly turned increasingly right-wing populist and xenophobic, not least in the wake of the 2015–2016 “refugee crisis.” This article traces the causal mechanism underlying the rise and subsequent radicalization of the Alternative for Germany, spelling out the respective importance, but also the drawbacks, of the twin windows of opportunity presented by the Eurozone debt crisis and the refugee crisis. In addition, the paper draws particular attention to the ways in which the public claims-making of its key figures reflects the party's overall development, i.e., from a soft Euroskeptic party aiming to dissolve the Eurozone to a conventional populist radical right party. Key figures highlighting this development include Bernd Lucke, Frauke Petry, and Alexander Gauland, but certainly also extreme voices such as Björn Höcke.

Introduction

The sudden rise and radicalization of the Alternative for Germany (AfD) has been one of the politically most significant consequences of the Eurozone debt crisis in Germany, both in terms of an increasing contentiousness of European integration, but also in terms of its impact on domestic politics more broadly. In this article, the party's development is analyzed from the vantage point of theories of Euroskepticism, emphasizing the seminal distinction between hard and soft Euroskepticism (Kopecký and Mudde, 2002; Taggart and Szczerbiak, 2004), but also highlighting the importance of the discursive dimension of Euroskepticism (De Wilde and Trenz, 2012). Under the leadership of Bernd Lucke, the AfD initially started out as a soft Euroskeptic party critical of the common currency and Angela Merkel's oft-quoted claim that there was “no alternative” to the Euro. At least since the onset of the “refugee crisis” in 2015–2016, the party has however undergone a quick, profound and arguably still ongoing process of radicalization that has seen it transform into a party along the lines of an “orthodox European right-wing populist party” (Lees, 2018) that has shifted its thematic scope mainly to issues of immigration and multiculturalism. Most recently, the party has also articulated a resentment toward measures adopted by the German and state-level governments to slow down the spread of the novel Corona virus.

The aim in this article is to trace the causal mechanism that can explain the party's sudden rise and radicalization. Causal mechanisms are understood in this context as entailing both “entities” and “activities” (Beach and Brun Pedersen, 2013), meaning that political outcomes have to be explained by considering the actions performed by political actors at specific junctures and interpreting how those actions have resulted in specific outcomes. In the context of the AfD's development, special emphasis is placed here on the twin windows of opportunity presented by the Eurozone debt crisis and the refugee crisis and how the actions taken by key figures within the AfD have contributed to the development of the party. While the former explains the emergence of the party as a soft Euroskeptic force critical of Angela Merkel's approach to the Eurozone debt crisis, the latter can be used to understand the subsequent radicalization of the party. To some extent, this radicalization is the outcome of early leaderships' attempts to appeal to voters on the far right of the political spectrum. As such, this process was arguably not triggered, but certainly catalyzed by the onset of the refugee crisis. The party's radicalization can only be fully understood by considering its public claims making, including—but not limited to—the discursive dimension of the party's Euroskepticism. The empirical analysis therefore investigates the public claims-making of key figures in the party, including Bernd Lucke, Frauke Petry and Alexander Gauland, but also more extreme voices such as Björn Höcke.

The article is organized as follows: following this brief introduction, the section The Emergence of the Alternative for Germany presents a literature overview on the AfD's development since its inception in 2012–2013. In the section Twin Windows of Opportunity: The Eurozone Debt Crisis and the Refugee Crisis, these findings are used to develop a causal mechanism that spells out the respective importance of the twin windows of opportunity presented by the Eurozone debt crisis and the refugee crisis. The section From Lucke to Höcke: The AfD's Development as Reflected in Public Claims-Making then presents the findings of the empirical analysis, tracing the party's development by highlighting how the claims-making of key figures within the party shifted from matters related to European integration to issues connected to immigration and multiculturalism. The article ends with a concluding discussion.

The Emergence of the Alternative for Germany

Even though some perceived the Alternative for Germany as a populist and/or radical right party already at the outset, it is now widely accepted that the party did not start out as such. Instead, the AfD's emergence can be explained as a direct response to Chancellor Angela Merkel's approach to the Eurozone debt crisis, specifically the so-called bailout packages offered to Greece from the spring of 2010 onwards. From this perspective, the party's ideological roots stem from ordoliberal critiques of the Maastricht Treaty, which were reflected in a sense of emergency over European bailouts and the ECB's monetary policy more broadly (Grimm, 2015). Unsurprisingly, the party's name is therefore a direct reference to Chancellor Angela Merkel's oft-quoted claim that there is “no alternative” to the common currency. Given not only the focus of the party's critique on this particular aspect of European integration, but also the profile of the party's founder Bernd Lucke and the party's initial supporters, the AfD was initially described as a “professors' party” (e.g., Lewandowsky, 2015; Bergmann et al., 2017).

Viewed from the vantage point of theories of Euroskepticism, most observers therefore categorize the AfD, in this initial phase of its existence, as a soft Euroskeptic party. This categorization is based on the terminology introduced by early theorists of Europskepticism, such as Kopecký and Mudde (2002) and Taggart and Szczerbiak (2004), who proposed a fundamental distinction between hard and soft (party-based) Euroskepticism. For Taggart and Szczerbiak, hard Euroskepticism entailed an outright rejection of European integration, whereas soft Euroskepticism entailed a more qualified rejection of certain aspects of European integration. By comparison, Kopecký and Mudde proposed to differentiate between diffuse support for the idea of European integration as such, and specific support for the European Union in its existing form, and thus identified four distinct forms of support for European integration (or lack thereof). Despite the critical position taken on the common currency, the early AfD's position neither challenged the existence of the European Union nor the idea of European integration as such, but rather challenged the feasibility of a common currency, all the more so in light of the problems of the common currency that became apparent in the wake of the Eurozone debt crisis.

It is also clear that despite its socially conservative positions—which had been there from the beginning (Arzheimer, 2015)—as well as the party's development and “ideological reorientation” from 2015 onwards (Goerres et al., 2018), the early AfD cannot be characterized as a right-wing populist party. In fact, despite certain references to stricter immigration laws (Arzheimer, 2015; Jankowski et al., 2017), the first party manifesto included references to the need to attract large numbers of skilled immigrants (Rensmann, 2018, p. 49; Arzheimer and Berning, 2019, p. 2). Similarly, an analysis of AfD candidates in the 2013 federal elections (the first federal elections that the party ran in) has shown that AfD candidates were more market-liberal, but no more authoritarian than their counterparts in the Christian Democratic Union (Jankowski et al., 2017). These observations lead numerous observers of the party's development to the conclusion that in this initial phase of its existence, the AfD was a soft Euroskeptic party, but not yet populist or radically right (Jankowski et al., 2017; Patton, 2017; Arzheimer and Berning, 2019).

Nevertheless, the literature on the emergence and development of the AfD certainly also points to the fact that despite the party's initially heavy emphasis on its critique of the common currency, it clearly also exploited its appeal with voters on the far right of the political spectrum, and it did so already under the leadership of Bernd Lucke and well before the “ideological reorientation” that was to take place from 2015 onwards. As pointed out by Schmitt-Beck (2017), only a minority of AfD voters in the federal elections were “instrumental issue voters” who voted for the AfD because of its position on the Euro crisis. By contrast, the majority were in fact “late supporters,” whose decision to vote for the AfD was made close to election day and based on xenophobic motives (Schmitt-Beck, 2017). The exploitation of such sentiments is also emphasized in David Patton's analysis of the AfD's radicalization. Patton emphasizes the role of radicals within the party in offering what appears to be a promising way forward, based on social movement activity (Patton, 2017)1. In this context, the relevance of the emergence of PEGIDA from 2014 onwards as well as various election successes at the state level in East Germany cannot be underestimated, as discussed further in the section Twin Windows of Opportunity: The Eurozone Debt Crisis and the Refugee Crisis below.

The subsequent radicalization of the party from 2015 onwards can therefore be described as sudden, but it did not by any means come out of the blue. The declining relevance of the party's initial core issue, i.e., its critique of the common currency (Schmitt-Beck, 2017), certainly plays a role here, but it is only part of the explanation for the party's radicalization. More importantly, the sudden radicalization reminds observers that virtually from the outset, the party had been characterized by a deep ideological divide between the market-oriented moderates (who founded the party) on the one hand, and radical national populists on the other hand, that resulted in a split in the party in July 2015 (Decker, 2016) and ultimately prompted the party's “ideological reorientation” from mid-2015 onwards (Goerres et al., 2018). According to Niedermayer (quoted in Jankowski et al., 2017), this ideological divide also has a regional dimension, as the ordoliberal and soft Euroskeptic wing (around party founder Bernd Lucke) had a mainly West German profile, whereas the national conservative wing (around Frauke Petry) had a mainly East German profile. This also underlines the relevance of socio-economic aspects in explaining the success of the party in the five East German states: the AfD is particularly successful in economically weak regions with high unemployment (Bergmann et al., 2017).

A key moment in the radicalization of the party—and one that highlights the ideological conflict in the party—came at the party congress in Essen in July 2015. In the context of this convention, Bernd Lucke published his “Weckruf” (or “wake-up call”) in order to gather the ordoliberal wing and thwart a nationalist-conservative take-over of the party. However, this move is seen only to have accelerated the party's breakup and resulted in Lucke's resignation at the party congress (Jankowski et al., 2017, p. 707).

Clearly, the party's radicalization also gained momentum with the beginning of the 2015–2016 refugee crisis. The issue of Angela Merkel's alleged “open-door policy” consequently became an increasingly salient topic in public debate (Conrad and Aðalsteinsdóttir, 2017), with xenophobic motives becoming more central for AfD voters (Schmitt-Beck, 2017). The contribution of PEGIDA to the radicalization of the AfD cannot be underestimated in this context, either. Some observers have pointed out that the AfD and PEGIDA are in fact two sides of the same coin (Grabow, 2016), while others point to the relevance of social movement activity as an important driver of the party's radicalization, especially in East Germany (Patton, 2017).

The party's radicalization from 2015 onwards reflects all of these developments: the declining salience of the Eurozone debt crisis and European bailouts, the increasing salience of issues of migration and xenophobia in the wake of the refugee crisis and the accompanying rise of PEGIDA, all of which can be seen as testimony to increasing concerns about the future of Germany's social and economic institutions among AfD supporters (Bergmann et al., 2017). But the party's radicalization is also driven by “successively more hard line party leaderships” (Lees, 2018). As mentioned above, the moderate and soft Euroskeptic Bernd Lucke lost the struggle for power at the party congress in July 2015. But even his successor Frauke Petry lost the struggle for power within 2 years over the question of how the party should deal with an even more extreme voice, namely that of Björn Höcke (see below in the section From Lucke to Höcke: The AfD's Development as Reflected in Public Claims-Making).

To sum up this discussion on the emergence and development of the AfD, we can conclude that despite its initial emphasis on an (ordoliberal) critique of the EU's monetary union, already the early AfD also appealed to voters on the far right of the political spectrum, in particular in the former East German states. This appeal was already indicative of a deep divide that was at the same time regional (East vs. West) and ideological (market-oriented moderates vs. national conservative), and that ultimately resulted in a de facto split in the party. After the departure of the market-oriented moderate wing in 2015, the AfD can now be described as a common populist radical right party (Arzheimer and Berning, 2019), its support depending on “the same set of socio-economic, attitudinal and contextual factors” that have proven important for populist radical right parties elsewhere (Goerres et al., 2018; cf. Olsen, 2018; Hansen and Olsen, 2019).

Twin Windows of Opportunity: the Eurozone Debt Crisis and the Refugee Crisis

Having established the state of the art in the literature on the emergence and development of the AfD—from a moderate, soft Euroskeptic single-issue party to a common populist radical right party—, it is now time to develop a causal mechanism capable of explaining how this development could take place. This is done with the help of a process-tracing design that views causal mechanisms not simply as events leading to one another, but rather focuses on the actions of specific actors/entities at critical junctures that generate the circumstances which, in turn, constitute the conditions for the next step in the analyzed causal chain (cf. Beach and Brun Pedersen, 2013).

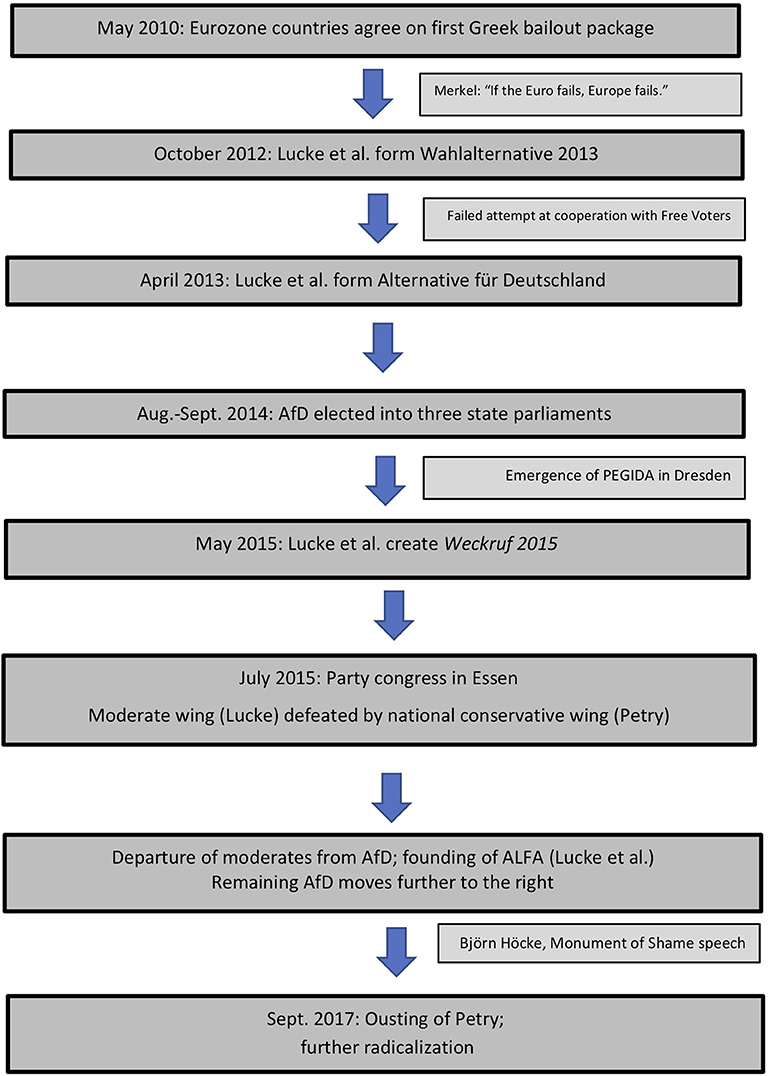

In the following discussion, the focus is primarily on the events that have contributed directly to the emergence, rise and development of the AfD from the Eurozone debt crisis onwards. One could of course argue that the root of the AfD is a deep-seated skepticism about the common currency that had been lingering since the negotiations on the Maastricht Treaty. On the other hand, the immediate cause of the founding of Bernd Lucke's (and others') Electoral Alternative 2013 and, subsequently, the AfD, was public discontent about the handling of the Eurozone debt crisis and, in particular, the so-called Greek bailout packages. Consequently, the Eurozone debt crisis and the Greek bailout packages can very well be seen as the starting point of the causal mechanism that triggered the emergence and rise of the AfD, but that subsequently also led to the successive radicalization of the party. In developing the causal mechanism, emphasis is placed on the interplay between two major European crises—the Eurozone debt crisis and the refugee crisis—that have fundamentally shaped the trajectory of the AfD since its founding in 2012–2013. The causal mechanism consists of eight parts and is described in detail below (see also Figure 1 for an illustration). It should be noted that the eight parts are all integral parts of the causal mechanism in the sense that they collectively shaped the development of the party. If any of them had played out differently, the party's development may very well have proceeded on a different trajectory, as explained in the discussion below. Therefore, the eight steps in the causal mechanism constitute an integrated whole rather than eight separate phases in the AfD's development. The eight parts are the following: (1) the adoption of the first Greek “bailout package” in May 2010, (2) the founding of the “Electoral Alternative 2013” in October 2012, (3) the founding of the AfD in April 2013, (4) the AfD's success in three successive state elections in East German states in August and September 2014, (5) the founding of “Weckruf 2015” in May 2015, (6) the de facto break-up of the AfD in the wake of the Essen national congress in July 2015, (7) the further shift toward issues of migration in the context of the refugee crisis; and (8) the ousting of Frauke Petry in the context of the federal elections in 2017.

Figure 1. Causal Mechanism: The AfD's emergence and transformation from a soft Euroskeptic into a populist right radical party (PRRP).

Before introducing the causal mechanism, it is important to draw attention to a number of points that are not directly connected to the causal mechanism, but that nonetheless provide important contextual information. As discussed above, the immediate impetus for the founding of the AfD was widespread discontent about the handling of the Eurozone debt crisis in the context of the “Greek bailout packages.” The latter were perceived by some voices in German public debate as too lenient, in particular with regard to what was construed as the Maastricht Treaty's “no bailout clause.” Angela Merkel's oft-cited speech in the Bundestag on May 19, 2010 plays a key role in this regard. Merkel argued that “if the Euro fails, Europe fails,” adding that the “rescue measures” for Greece were “alternativlos,” i.e., “without any alternative.” As a point of reference for the name of the Electoral Alternative as well as for the Alternative for Germany, this formulation has been exploited time and again to highlight the presumed failures of the Merkel government.

Regarding the gradual transformation of the AfD into a populist radical right party, it also has to be mentioned that this process occurred in a highly specific political and societal climate, especially in at least parts of the five East German states. Concerns about an increasing “Islamization” of Germany had emerged even before the beginning of the refugee crisis in the late summer of 2015, resulting in the founding of the PEGIDA movement and the initiation of its (still ongoing) weekly “evening strolls” in Dresden as early as October 2014. At their peak, these “evening strolls” attracted well over 20,000 marchers. While not part of the causal mechanism in the sense of exerting any direct causal force, this development is clearly important contextual information that helps to understand (a) the young AfD's electoral successes at the state level (see below) as well as (b) the causal force that these electoral successes have exerted in terms of increasing the salience of issues connected to immigration and multiculturalism and deepening the ideological divide between moderates and national conservatives within the party. Of course, the sudden emergence and striking popularity of the PEGIDA marches also has to be seen as a consequence of socio-economic developments since German reunification, in particular in the five East German states.

This contextual information is also instrumental in understanding the last part of the causal mechanism, namely the ousting of Frauke Petry in the wake of the 2017 federal elections. As part of the AfD's national conservative wing, Petry had played a central role in the ousting of Bernd Lucke and the departure of the moderate wing in July 2015, and became one of two party chairs on the same occasion. To the surprise of many, Petry announced on the day after the 2017 federal elections that she would not be part of the AfD in the newly elected Bundestag, left the party shortly after and founded the Blue Party (Siri, 2018). Petry left the AfD largely as a consequence of the party's continuing move toward the far right, underlined in particular by her unsuccessful attempt to have Björn Höcke removed from the party. Höcke is the head of the AfD in the state of Thuringia and is widely perceived as one of the most extreme voices at the top level of the AfD, as expressed for instance by remarks about Germany's politics of remembrance and the Holocaust memorial in Berlin (see below in the section From Lucke to Höcke: The AfD's Development as Reflected in Public Claims-Making). The fact that Höcke is still a highly influential party member while both Lucke and Petry are gone is certainly strong testimony to the ongoing transformation of a party that once started out as a soft Euroskeptic party with an explicit commitment to the idea of European integration.

It should also be mentioned that already prior to the state-level elections in the East German states of Saxony, Thuringia and Brandenburg, the AfD had enjoyed considerable success at the federal elections in September 2013 as well as at the European Parliament elections in May 2014. At the former, the party—though only having been founded a few months before, only barely missed the 5% threshold that would have allowed it to enter into the Bundestag; at the latter, on the other hand, the party won seven out of the 96 German seats.

With this in mind, the causal mechanism explaining the emergence, rise, and transformation of the AfD begins with the Eurozone countries' agreement on a first Greek “bailout package,” worth €110 billion, on May 2, 2010. In Germany, this decision was perceived by numerous conservative and liberal politicians alike as a violation of the Maastricht Treaty's “no bailout clause,” and was arguably the most salient issue of public debate in Germany in the spring of 2010. In particular, the role of the German government was criticized domestically for not adequately taking the national interest into account, as argued by Alexander Gauland upon the founding of the “Electoral Alternative 2013” in October 2012 (Die Welt, 2012). The founding of the Electoral Alternative by Bernd Lucke, Alexander Gauland, Konrad Adam, and Gerd Robanus, in October 2012, therefore has to be seen as a direct consequence of the contestation surrounding the first bailout package—without this contestation, the Electoral Alternative would not have been founded, and without the Electoral Alternative, there would have been no basis for a party such as the Alternative for Germany. In this context, Alexander Gauland—previously a member of Angela Merkel's Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and even a former state secretary in Walter Wallmann's government in the state of Hesse, and at the time of writing honorary chairman of the AfD at the federal level—claimed that there was (at the time) no political force in Germany capable of changing Germany's policy in the Eurozone crisis, which was considered to be wrong by “at least a large minority, if not even a majority” of Germans (Die Welt, 2012).

The Electoral Alternative was explicitly not created as a party, but merely as an association. Instead of aiming to run in the Federal Elections in 2013 itself, it rather sought cooperation with existing parties ahead of the elections. At this time, the Electoral Alternative saw the party of “Free Voters” as a natural cooperation partner and even entered the state elections in Lower Saxony in January 2013 within this constellation (with Bernd Lucke as one of the lead candidates). However, the cooperation was terminated soon after the elections, due not least to the Electoral Alternative's harder stance on the common currency, with the aim of returning to the German Mark. Given the short-lived nature of the attempted cooperation with the Free Voters, one can conclude that the founding of the Alternative for Germany in April 2013 was in fact a direct result of the creation of the Electoral Alternative, and as such an indispensable part of the causal mechanism identified here.

As the next part of the causal mechanism, the founding of the AfD in April 2013 is important in that it created an organizational infrastructure that allowed the new party to participate in the federal elections in September 2013 and in the European Parliament elections in May 2014. From the perspective of the party's transformation away from its character as a single-issue, soft Euroskeptic party, it is also relevant that the founding of the AfD at the federal level more or less coincided with the creation of state-level branches2 that managed to get elected into the state legislatures of three East German states (Saxony, Thuringia and Brandenburg) in August and September 2014. They did so after having campaigned largely on issues connected to immigration and multiculturalism. These electoral successes at the state level evidently challenged Bernd Lucke's moderate position and strengthened key figures on the national-conservative wing, most notably Frauke Petry, Alexander Gauland, and Björn Höcke (Patton, 2017, p. 172). They are therefore also an integral part of the causal mechanism: without them, there would have been at best very little reason for the party to pursue a thematic shift from the common currency to issues of immigration and multiculturalism. In this regard, it should be noted that more radical voices had certainly been around in the party from the outset; but it was the electoral successes at the state level that allowed them to become more dominant in the party as a whole.

This beginning ideological and thematic reorientation, occurring as it did in an environment marked by the PEGIDA marches, set in motion processes that resulted in the eventual de facto break-up of the AfD. Again, these processes gained momentum due to the state-level electoral successes in 2014, which are therefore an integral part of the causal mechanism. They are also the direct cause of the next part of the causal mechanism in that they prompted the founding of Bernd Lucke's “wake-up call 2015” (“Weckruf 2015”) in May 2015. This association was created in response to the increasing salience of immigration and multiculturalism within the party, as part of an effort to gather moderate forces in the party, thwart a nationalist takeover and re-emphasize the party's foundational issues ahead of the party convention in Essen in July 2015. Ironically, however, it resulted in deepening existing divisions between moderates and nationalist-conservatives and culminated in Lucke's defeat in the election for party chair in July 2015 and in the breakaway of Lucke and his followers—including five of seven MEPs—to start a new party (the “Allianz für Fortschritt und Aufbruch”). Even though Lucke and his followers intended to achieve the opposite, the creation of wake-up call thus played a decisive role in the radicalization of the party—a pattern that repeats itself 2 years later when Frauke Petry—who was an instrumental part of the national conservative wing (see below)—leaves the party to start the “Blue Party.”

Although there is obviously no causal link between this split in the AfD and the onset of the refugee crisis in the late summer of 2015, the latter—in combination with the above-mentioned state-level electoral successes and the emergence of PEGIDA—clearly provided a second window of opportunity and a strong incentive for the AfD to shift its focus even further to the issue of immigration. Connected to this, there is a clear link between Merkel's decision—in coordination with her Austrian counterpart—not to close the German border to refugees arriving from Hungary via Austria, and the AfD and PEGIDA's rhetoric exploitation of Merkel's oft-quoted statement (from August 2015) that “we will manage this!” (“Wir schaffen das!”).

Without claiming that the transformation of the AfD is necessarily complete or concluded, the causal mechanism identified here ends with the ousting of Frauke Petry from the party immediately after the 2017 federal elections. Even though Petry, as a key figure within the party's national conservative wing, played a central role in the ousting of her moderate predecessor Bernd Lucke, her departure from the party can nonetheless be viewed as a direct consequence of the radicalization of the party—and specifically the powerful position of Björn Höcke, the chairman of the state-level branch in Thuringia. In a speech delivered to the party's youth organization Junge Alternative in Dresden in January 2017, Höcke had caused outrage by calling for a U-turn in Germany's culture of memory, specifically by questioning the Holocaust memorial in Berlin and referring to it as a monument of shame or disgrace (see From Lucke to Höcke: The AfD's Development as Reflected in Public Claims-Making section). In the aftermath, Petry called for the expulsion of Höcke from the party, but Höcke was supported by Alexander Gauland and Jörg Meuthen, before a party arbitration court ultimately ruled—already after Petry's departure—that Höcke could remain a member of the party.

In sum, we thus see a causal mechanism that has transformed the AfD from a soft Euroskeptic, though vehemently anti-common currency party into a party that not only tolerates, but whose leaders back extreme voices such that of Björn Höcke. In this regard, it is very clear that the ideological struggle that had existed since the beginning—has been won by the far right.

From Lucke to Höcke: the AfD's Development as Reflected in Public Claims-Making

The ambition in this final part of the article is to trace how the AfD's transformation from Bernd Lucke's soft Euroskeptic into a populist radical right party is reflected in the public claims-making of some of its key proponents. In our analysis, these key figures include Bernd Lucke, Alexander Gauland, Frauke Petry, and Björn Höcke. The AfD's rhetoric—even as employed by more moderate voices such as Bernd Lucke—has been highly confrontational toward the established mainstream parties and highlighted the party's self-perception as the only real alternative for voters who want to see a change in politics. Still, it is striking to see the close connection between the party's overall development and an increasing frequency of ever more offensive remarks and actions downplaying the crimes committed under National Socialism and/or criticizing Germany's “culture of contrition” (Langenbacher, 2010). Similarly, the move to the radical right is also reflected in offensive statements and presumably planned provocations about immigrants and refugees that cater to the part of the electorate that the AfD currently appears to be aiming for, as demonstrated below.

The Initial Phase: Bernd Lucke's Soft Euroskepticism: for Europe, but Against EMU

In the party's foundational phase under the leadership of Bernd Lucke, the AfD was a soft Euroskeptic party in the conventional theoretical sense of the term, i.e., it expressed a clear and unequivocal support for the idea and ideals of European integration, while being unrelenting in its critique of the common currency. To use Kopecký and Mudde's terminology, this mix of a diffuse support for European integration with an at least partial lack of specific support for the idea of economic and monetary union is clearly expressed already in Bernd Lucke's speech at the founding party congress in Berlin in May 2013 (Lucke, 2013).

Here, but also in various other speeches and public appearances in the mass media (e.g. Deutsche Welle, 2017a), Lucke confirmed the AfD's commitment to the idea of European integration, claiming that “we all want European integration, and we all want the internal market” and that the “[preservation of] the project of European unification in the tradition of Adenauer, Schmidt, Genscher and Kohl [was] one of the key ambitions of the AfD” (Lucke, 2013, p. 2). It is actually precisely for this reason that the common currency is rejected. For Lucke, it represents an “historic mistake” (Lucke, 2013, p. 8) that constitutes an existential threat to the idea of European unification in that it allegedly pits the nations of Europe against one another and reinforces their mutual resentment. Notably, the speech refers to Angela Merkel's oft-cited claim that efforts to save the Euro were “without any alternative” and that “if the Euro fails, Europe fails” (see also the section Twin Windows of Opportunity: The Eurozone Debt Crisis and the Refugee Crisis above), to which Lucke responds that “nothing on Earth is without any alternatives,” adding that if the common currency were to fail, it would not be Europe that fails, but instead the German government as well as the other mainstream parties in a Bundestag that merely rubberstamps rescue packages presented as being without any alternatives (Lucke, 2013, p. 9).

The Intermediate Phase: Increasingly Xenophonic Provocations

The party's increasing move to the far right in the second phase, lasting from the de facto split in the wake of the 2015 party congress and Frauke Petry's departure in September 2017, has already been discussed. The increasing emphasis on issues connected to immigration and multiculturalism in this phase is clearly reflected in a hardening rhetoric that many observers interpret as calculated provocations (e.g., Ruhose, 2018). A number of examples involving both Frauke Petry and Alexander Gauland stand out in this regard and will be reviewed here.

In January 2016, at the peak of the refugee crisis and shortly after the New Year's Eve incidents in Cologne and other German cities, Petry was interviewed by the newspaper Mannheimer Morgen and asked specifically about her claim that “law and order have to be reinstated at the German border” (Mannheimer Morgen, 2016, author's translation). When pressed to explain precisely how German border police was supposed to stop illegal border crossings, Petry stated that they have to “prevent illegal border crossings, and even use firearms, if necessary. That is what the law says” (Mannheimer Morgen, 2016; cf. Deutsche Welle, 2016a). In the aftermath, Petry and the AfD claimed that the newspaper had put words in her mouth, but the newspaper's editor insists that Petry had offered to give the interview herself, and that she had read and authorized every sentence prior to the interview's publication (Meedia, 2016).

Similarly provocative remarks were made by Alexander Gauland. Given that Gauland had been a founding member both of the Electoral Alternative in 2012 and of the Alternative for Germany in 2013, one might assume that he would be among the party's more moderate voices. However, the development of his rhetoric has very much been in line with the overall development of the party. In May 2016, Gauland sparked controversy when remarks became public that he had made in the context of a confidential background talk with journalists of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung. In these remarks, Gauland spoke about Jerôme Boateng, a professional football player and member of Germany's 2014 World Cup winning national team, who is born and raised in Berlin, but whose father is Ghanaian. Gauland claimed that although Germans liked Boateng as a football player, they would not like living next door to him (Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 2016). Gauland later claimed not to have talked about Boateng at all, before conceding that was not fully aware of who Boateng was due to a lack of interest in football. However, only a few days later, Gauland sparked even further controversy when stating that with a view to the players' ethnic origins, the German national team had not been German “in the classical sense” for a long time (Deutsche Welle, 2016b). But these remarks, which are presumably calculated provocations aimed at a specific group of potential AfD voters, are at best one step in the gradual radicalization of the AfD's public claims-making.

Gauland also sparked outrage after a speech at a campaign rally in the Thuringian district of Eichsfeld in August 2017. On this occasion, Gauland addressed remarks made by the German government's commissioner for integration, Aydan Özuguz. Özuguz, who is of Turkish descent, had claimed in an interview that “beyond the German language, a specifically German culture is simply not identifiable.” Referring to these remarks, Gauland encouraged his audience to “invite her to the Eichsfeld and tell her what specifically German culture is. After that, she will never come back and we will—thank God!—be able to dispose of her in Anatolia” (Der Tagesspiegel, 2017b; author's translation; cf. Deutsche Welle, 2017c). In the same speech, Gauland claimed that “they want to take this Germany away from us. And, dear friends, this is almost—in the past, you would have called it an invasion—like a creeping land grab. And we have to resist this creeping land grab together” (Der Tagesspiegel, 2017b; author's translation). When confronted with the statement shortly after, Gauland said he had no recollection of using the term “dispose of,” but confirmed his view that someone who makes statements of the kind of Özuguz's “should go back to Anatolia” (Der Tagesspiegel, 2017b; author's translation).

Somewhat ironically, this phase in the party's development also witnesses a controversy that ultimately brings about the demise of Frauke Petry and foreshadows the subsequent further radicalization of the party. Downplaying the crimes of National Socialism is clearly not acceptable in German political discourse, but the Thuringian AfD leader Björn Höcke did so in a speech that can only be considered a planned provocation, both in terms of content and timing. Speaking to the AfD's youth organization in January 2017, Höcke urged “a 180-degree-turn in our politics of remembrance” and “a living culture of remembrance that first and foremost exposes us to the great achievements of past generations,” arguing that “instead of exposing the coming generation to the great benefactors, the famous philosophers, musicians, the brilliant discoverers and inventors that we have so many of […], German history is being made appalling and ridiculous.” The culmination of these remarks was however the formulation, referring to the Holocaust memorial in Berlin, that “we Germans […] are the only people in the world that has planted a monument of shame in the heart of its capital” (Der Tagesspiegel, 2017a author's translation). Not only the content, but also the timing of the remarks— 3 days before the 75th anniversary of the Wannsee conference, at which the Nazis decided on the “final solution”—were supposedly designed to cause maximum offense (Deutsche Welle, 2017b).

With a view to the radicalization of the party, this provocation is particularly relevant because it caused Frauke Petry to strive for having Höcke removed from the party. Although the party leadership collectively decided to open proceedings to this end, Alexander Gauland and Jörg Meuthen notably voted against this decision (Der Spiegel, 2017).

The Last Phase: A Monument of Shame and Bird Shit in German History

In the last phase, following Frauke Petry's ousting in 2017 (who was considered too moderate by then), the party takes an even more decisive move to the (radical) right. What would have been unthinkable when the party was founded in 2013, namely to call for a German exit from the European Union (or “Dexit,” as the party calls it), is now explicitly mentioned in the party's platform for the 2019 elections to the European Parliament, albeit only as a measure of last resort and without specifying a time frame (although the latter was in fact discussed in the drafting of the party platform).

This phase also witnesses the continuation of key figures downplaying the relevance of the crimes of national socialism. At the congress of the AfD's youth organization in Seebach, Thuringia, in June 2018, Gauland said the following words, which are even documented on the website of the AfD's group in the Bundestag (Alternative für Deutschland, 2018; author's translation; see also Deutsche Welle, 2018):

“We have a glorious history that has lasted longer than twelve years. And only if we accept this history, we can have the power to shape the future. Yes, we accept our responsibility for the twelve years. But, dear friends, Hitler and the Nazis are merely bird shit in our one-thousand-year history” (emphasis added).

In sum, we can therefore see how the discourse of the Alternative for Germany has changed over the course of its existence. After starting out as a party that emphasized the importance of European integration and actually claimed to want to preserve the European idea from the “historic mistake” of a common currency, the party has ousted several leaderships and replaced them with more and more radical successors. This has resulted not merely in an increasingly xenophobic tone. With a view to the interpretation of the crimes of National Socialism, it has also begun to erode the foundations of acceptable political speech.

Conclusions

This article has demonstrated that the emergence, rise and gradual radicalization of the Alternative for Germany has by no means been a matter of coincidence, but that it has been the outcome of a causal mechanism that started with the Eurozone debt crisis and the agreement on the first Greek bailout package in the spring of 2010. As such, the AfD's development—from a soft Euroskeptic party into a populist radical right party—was by no means a matter of necessity, but rather the result of specific choices made by specific actors at critical junctures in the party's development from 2012 onwards. The process-tracing part of the study has revealed that despite the ordoliberal ideological orientation that characterized both the Electoral Alternative 2013 and the early Alternative for Germany (under the leadership of Bernd Lucke), the party was quickly marked by a deep divide that was on the surface ideological (between ordoliberal moderates and national conservatives), but that also revealed a clear East-West dimension. This divide clearly ran deeper than the idea of a strategic attempt to broaden the electoral appeal of the “professor's party” to (far-)right voters would suggest. The impetus to move in that direction came from within the party, but also has explanations on the demand side of the party spectrum. Therefore, it is more accurate to emphasize that the party's transformation was due to the fact that the party began to live a life of its own—not merely in the wake of the state elections in Brandenburg, Saxony and Thuringia in the late summer of 2014, but also in the context of a societal climate increasingly skeptical of Angela Merkel's approach to the refugee crisis, which also found expression in the sudden rise of PEGIDA. In explaining this societal climate, it is almost tautological to point to the underlying effect of social and economic development in the five East German states since reunification. Against this backdrop, the move to the far right is better framed as a case of loss of control over the party by its original leadership. In this sense, Lucke's attempt to gather his supporters in advance of the Essen party congress in 2015 catalyzed rather than prevented the break-up of the party, and thus contributed significantly to its ideological reorientation and radicalization.

As the last part of the article demonstrates, this development is also reflected well in the public statements made by key figures in the party. Whereas Lucke's original criticism of the common currency was directed largely toward the established mainstream parties in the Bundestag, the selected claims made by Petry, Gauland, and Höcke are best described as planned provocations catering to a very specific target audience. To some extent, this amounts to vaguely disguised racism (as in the case of Gauland), but it has now even reached the level of downplaying the relevance of the crimes of National Socialism in what appears to be perceived as the bigger picture of German history. Given the fertile ground upon which this seems to fall, the twin windows of opportunity mentioned in this article (i.e., the Eurozone debt crisis and the refugee crisis) are obviously a double-edged sword: the former has allowed for the emergence of a new party critical of EMU and the German government's policies to rescue the common currency. The latter, on the other hand, has clearly resulted in the party more or less completely compromising its initial ambitions and completing its transformation into a populist radical right party.

Author Contributions

MC wrote the entire article and did all the research.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

1. ^Patton's analysis compares the radicalization of the AfD to the development of the National Democratic Party (NPD) in the 1960s, the Greens in the 1990s, the Party of Democratic Socialism (PDS) in the early 2000s and the Left Party in the period between 2007 and 2011, and identifies social movement activity as one of four key drivers of radicalization.

2. ^The state-level branches in Saxony, Thuringia, and Brandenburg were all created in April 2013.

References

Alternative für Deutschland (2018). Wortlaut der umstrittenen Passage der Rede von Alexander Gauland. Available online at: https://www.afdbundestag.de/wortlaut-der-umstrittenen-passage-der-rede-von-alexander-gauland/ (accessed August 31, 2019).

Arzheimer, K. (2015). The AfD: finally a successful right-wing populist eurosceptic party for Germany? West Eur. Polit. 38, 535–556. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2015.1004230

Arzheimer, K., and Berning, C. C. (2019). How the Alternative for Germany (AfD) and their voters veered to the radical right. Elect. Stud. 60, 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2019.04.004

Beach, D., and Brun Pedersen, R. (2013). Process-Tracing Methods. Foundations and Guidelines. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press. doi: 10.3998/mpub.2556282

Bergmann, K., Diermeier, M., and Niehues, J. (2017). Die AfD: Eine Partei der sich ausgeliefert fühlenden Durchschnittsverdiener? ZParl Zeitschrift für Parlamentsfragen 48, 57–75. doi: 10.5771/0340-1758-2017-1-57

Conrad, M., and Aðalsteinsdóttir, H. (2017). Understanding Germany's short-lived ‘Culture of Welcome’: images of refugees in three leading German Quality Newspapers. Ger. Polit. Soc. 35, 1–21. doi: 10.3167/gps.2017.350401

De Wilde, P., and Trenz, H.-J. (2012). Denouncing European integration: Euroskepticism as polity contestation. Eur. J. Soc. Theory 15, 537–554. doi: 10.1177/1368431011432968

Decker, F. (2016). The Alternative for Germany: factors behind its emergence and profile of a new right-wing populist party. Ger. Polit. Soc. 34, 1–16. doi: 10.3167/gps.2016.340201

Der Spiegel (2017). Höcke entschuldigt sich auf AfD-Parteitag. Available online at: https://www.spiegel.de/politik/deutschland/bjoern-hoecke-vor-der-afd-entschuldigung-fuer-dresden-rede-a-1135230.html (accessed August 31, 2019).

Der Tagesspiegel (2017a). Gemütszustand eines total besiegten Volkes. Available online at: https://www.tagesspiegel.de/politik/hoecke-rede-im-wortlaut-gemuetszustand-eines-total-besiegten-volkes/19273518-all.html (accessed August 31, 2019).

Der Tagesspiegel (2017b). Gauland will Integrationsbeauftragte Özuguz, in Anatolien entsorgen. Available online at: https://www.tagesspiegel.de/politik/afd-spitzenkandidat-gauland-will-integrationsbeauftragte-oezoguz-in-anatolien-entsorgen/20244934.html (accessed August 10, 2020).

Deutsche Welle (2016a). German Right-Leaning AfD Leader Calls for Police Right to Shoot at Refugees. Available online at: https://www.dw.com/en/german-right-leaning-afd-leader-calls-for-police-right-to-shoot-at-refugees/a-19013137 (accessed August 31, 2019).

Deutsche Welle (2016b). AfD Politician Says Germany's Football Team Isn't German. Available online at: https://www.dw.com/en/afd-politician-says-germanys-football-team-isnt-german/a-19305613 (accessed August 31, 2019).

Deutsche Welle (2017a). Bernd Lucke: ‘Es ist falsch, die AfD zu dämonisieren. Available online at: https://www.dw.com/de/bernd-lucke-es-ist-falsch-die-afd-zu-dämonisieren/a-39214346 (accessed August 31, 2019).

Deutsche Welle (2017b). Local AfD Leader's Holocaust Remarks Prompt Outrage. Available online at: https://www.dw.com/en/local-afd-leaders-holocaust-remarks-prompt-outrage/a-37173729 (accessed August 31, 2019).

Deutsche Welle (2017c). AfD's Alexander Gauland Slammed Over 'Racist' Remark Aimed at Minister. Available online at: https://www.dw.com/en/afds-alexander-gauland-slammed-over-racist-remark-aimed-at-minister/a-40277497 (accessed August 30, 2019).

Deutsche Welle (2018). AfD's Gauland Plays Down Nazi Era as A 'Bird Shit' in German History. Available online at: https://www.dw.com/en/afds-gauland-plays-down-nazi-era-as-a-bird-shit-in-german-history/a-44055213 (accessed August 30, 2019).

Die Welt (2012). Enttäuschte CDU-Politiker Gründen Wahlalternative. Available online at: https://www.welt.de/politik/deutschland/article109606449/Enttaeuschte-CDU-Politiker-gruenden-Wahlalternative.html

Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (2016). Gauland Beleidigt Boateng. Available online at: https://www.faz.net/aktuell/politik/inland/afd-vize-gauland-beleidigt-jerome-boateng-14257743.html (accessed August 31, 2019).

Goerres, A., Spies, D. C., and Kumlin, S. (2018). The electoral supporter base of the Alternative for Germany. Swiss Polit. Sci. Rev. 24, 246–269. doi: 10.1111/spsr.12306

Grabow, K. (2016). PEGIDA and the alternative für Deutschland: two sides of the same coin? Eur. View 15, 173–181. doi: 10.1007/s12290-016-0419-1

Grimm, R. (2015). The rise of the German Eurosceptic party Alternative für Deutschland, between ordoliberal critique and popular anxiety. Int. Polit. Sci. Rev. 36, 264–278. doi: 10.1177/0192512115575384

Hansen, M. A., and Olsen, J. (2019). Flesh of the same flesh: a study of voters for the Alternative for Germany (AfD) in the 2017 Federal Election. Ger. Polit. 28, 1–19. doi: 10.1080/09644008.2018.1509312

Jankowski, M., Schneider, S., and Tepe, M. (2017). Ideological alternative? Analyzing Alternative für Deutschland candidates' ideal points via black box scaling. Party Polit. 23, 704–716. doi: 10.1177/1354068815625230

Kopecký, P., and Mudde, C. (2002). The two sides of Euroskepticism. Party Positions on European Integration in East Central Europe. Eur. Union Polit. 3, 297–326. doi: 10.1177/1465116502003003002

Langenbacher, E. (2010). Still the unmasterable past? The impact of history and memory in the Federal Republic of Germany. Ger. Polit. 19, 24–40. doi: 10.1080/09644001003588473

Lees, C. (2018). The ‘Alternative for Germany’: the rise of right-wing populism at the heart of Europe. Politics 38, 295–310. doi: 10.1177/0263395718777718

Lewandowsky, M. (2015). Eine rechtspopulistische Protestpartei? Die AfD in der öffentlichen und politikwissenschaftlichen Debatte. ZPol Zeitschrift für Politikwissenschaft 25, 119–134. doi: 10.5771/1430-6387-2015-1-119

Lucke, B. (2013). Speech Delivered at the Founding Congress of the Alternative for Germany in Berlin. Available online at: https://deutsche-wirtschafts-nachrichten.de/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/Rede-Bernd-Lucke.pdf (accessed August 31, 2019).

Mannheimer Morgen (2016). Sie können es nicht lassen! Available online at: https://www.morgenweb.de/mannheimer-morgen_artikel,-politik-sie-koennen-es-nicht-lassen-_arid,751556.html (accessed August 31, 2019).

Meedia (2016). Frauke Petry vs. Mannheimer Morgen: Schusswaffen-Interview wird zum Fall für den Presserat. Available online at: https://meedia.de/2016/02/08/frauke-petry-vs-mannheimer-morgen-schusswaffen-interview-wird-zum-fall-fuer-den-presserat/ (accessed August 31, 2019).

Olsen, J. (2018). The left party and the AfD: populist competitors in Eastern Germany. Ger. Polit. Soc. 36, 70–83. doi: 10.3167/gps.2018.360104

Patton, D. F. (2017). The alternative for Germany's radicalization in historical-comparative perspective. J. Contemp. Central East. Eur. 25, 163–180. doi: 10.1080/25739638.2017.1399512

Rensmann, L. (2018). Radical right-wing populists in parliament: examining the ‘alternative for Germany’ in European context. Ger Politics Soc. 36, 41–73. doi: 10.3167/gps.2018.360303

Ruhose, F. (2018). Die AfD im Deutschen Bundestag. Wiesbaden: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3-658-23361-7

Schmitt-Beck, R. (2017). The ‘Alternative für Deutschland in the Electorate’: between single-issue and right-wing populist party. Ger. Polit. 26, 124–148. doi: 10.1080/09644008.2016.1184650

Siri, J. (2018). The alternative for Germany after the 2017 election. Ger. Polit. 27, 141–145. doi: 10.1080/09644008.2018.1445724

Keywords: Euroskepticism, Germany, Alternative for Germany (AfD), process tracing, causal mechanism, populist radical right parties, European Union—EU

Citation: Conrad M (2020) From the Eurozone Debt Crisis to the Alternative for Germany. Front. Polit. Sci. 2:4. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2020.00004

Received: 06 March 2020; Accepted: 16 July 2020;

Published: 27 August 2020.

Edited by:

Sevasti Chatzopoulou, Roskilde University, DenmarkReviewed by:

Andrea M. Fumagalli, University of Pavia, ItalyDavid F. Patton, Connecticut College, United States

Copyright © 2020 Conrad. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Maximilian Conrad, bWNAaGkuaXM=

Maximilian Conrad

Maximilian Conrad