94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Plant Sci. , 25 February 2025

Sec. Plant Breeding

Volume 16 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2025.1558293

The opening of cotton bolls is an important characteristic that influences the precocity of cotton. In the field, farmers often use chemical defoliants to induce cotton leaves to fall off earlier, thus accelerating the cracking of cotton bolls. However, the molecular mechanism of cotton boll cracking remains unclear. We identified ten AGAMOUS subfamily genes in upland cotton. Three pairs of Gossypium hirsutum AG subfamily genes (GhAGs) were amplified via tandem duplication. The promoters of the GhAGs contained a diverse array of cis-acting regulatory elements related to light responses, abiotic stress, phytohormones and plant growth and development. Transcriptomic analyses revealed that the expression levels of GhAG subfamily genes were lower in vegetative tissues than in flower and fruit reproductive organs. The qRT−PCR results for different tissues revealed that the GhSHP1 transcript level was highest in the cotton boll shell, and GhSHP1 was selected as the target gene after comprehensive analysis. We further investigated the functional role of GhSHP1 using virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS). Compared with those of the control plants, the flowering and boll cracking times of the GhSHP1-silenced plants were significantly delayed. Moreover, the results of paraffin sectioning at the back suture line of the cotton bolls revealed that the development of the dehiscence zone (DZ) occurred later in the GhSHP1-silenced plants than in the control plants. Furthermore, at the same developmental stage, the degree of lignification in the silenced plants was lower than that in the plants transformed with empty vector. The expression of several upland cotton genes homologous to key Arabidopsis pod cracking genes was significantly downregulated in the GhSHP1-silenced plants. These results revealed that GhSHP1 silencing delayed the flowering and cracking of cotton bolls and that the cracking of cotton bolls was delayed due to effects on DZ development. These findings are highly important for future studies of the molecular mechanism of cotton boll cracking and for breeding early-maturing and high-quality cotton varieties.

The fruits of many flowering plants (such as siliques, capsules, and pods) need to crack and release their seeds after maturity to support the reproduction of future generations. The cracking of the fruit after ripening is called pod shattering in soybeans, silique dehiscence in Brassica napus, and boll opening in upland cotton. Although seed dispersal through fruit cracking is an important method of plant reproduction, the application of this trait is completely different in different crop breeding methods. For crops such as soybeans and oilseed rape, the premature cracking of pods or siliques can easily lead to seed shattering, resulting in a significant reduction in crop yield. However, the cracking of cotton bolls is conducive to the release of cotton fibers, and early boll opening is one of the key target traits of cotton breeding for early maturity. Although many studies have explored the mechanism of silique and pod cracking (Liljegren et al., 2000), the mechanism of capsule cracking (such as in cotton bolls) has not been studied extensively.

The mechanism of silique dehiscence has been explored mainly in the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana. When the silique shell of A. thaliana is transected, three components can be observed in the silique shell: the valves, valve margins and replum (Dinneny and Yanofsky, 2005; Chen et al., 2024). Valves develop from the carpel, which consists of six layers of cells, including the outer epidermis, three layers of mesophyll tissue, endocarp layer b (enb) and endocarp layer a (ena) (degenerate during fruit ripening) (Dinneny and Yanofsky, 2005; Gu et al., 1998; Vivian-Smith et al., 2001). The area between the valve and the replum is called the valve margin and is composed of a lignified layer (LL) and a separation layer (SL). These two layers also form dehiscence zones (DZs) during silique cracking (Ferrándiz et al., 1999). A gene regulatory network involved in silique cracking initially forms (Ballester and Ferrándiz, 2017). Studies of this regulatory network revealed that the MADS-box (MCM1, AGAMOUS, DEFICIENS, SRF) transcription factors SHATTERPROOF1 (SHP1/AGL1) and SHATTERPROOF2 (SHP2/AGL5) (Liljegren et al., 2000) and the basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factors INDEHISCENT (IND) (Liljegren et al., 2004) and ALCATRAZ (ALC) (Rajani and Sundaresan, 2001) are associated with the development of the valve margin and regulate the development of the DZ, leading to silique cracking (Ferrándiz, 2002; Lewis et al., 2006). As part of this regulatory pathway, SHP1/2 positively regulate the downstream factors IND and ALC. Moreover, IND and ALC control valve margin development independently of each other. SHP1/2 and IND are essential for the development of both the lignified layer and the separation layer, whereas ALC is required for the formation of only the separation layer (Liljegren et al., 2000, 2004; Rajani and Sundaresan, 2001). The activities of valve margin identity genes are inhibited by FRUITFULL (FUL) in the valve (Ferrándiz et al., 2000; Gu et al., 1998) and the transcriptional regulatory factor REPLUMLESS (RPL), which is involved in the development of the replum (Ferrándiz et al., 2000; Roeder et al., 2003; Liljegren et al., 2004). In other words, SHP1/2, IND and ALC expression is limited to the valve margin through repression by FUL in the valve and by RPL in the replum. AP2 negatively regulates the expression of replum and valve margin identity genes to prevent excessive growth of replum and valve margins (Ripoll et al., 2011). NAC SECONDARY WALL THICKENING PROMOTING FACOTR1 (NST1), which is expressed in the enb layer and highly expressed in developing LL cells, modulates silique cracking by controlling cell wall thickening (Mitsuda and Ohme-Takagi, 2008; Zhong et al., 2010). ARABIDOPSIS DEHISCENCE ZONE POLYGALACTURONASE1 (ADPG1), which is expressed in the SL in DZs, encodes plant-specific endo-polygalacturonases (PGs) and promotes silique cracking by reducing cell adhesion (Ogawa et al., 2009; Roberts et al., 2002). In addition, some plant hormones, such as auxin, cytokinin and gibberellin, regulate the development of siliques, pods and capsules, and ethylene is a growth regulator that is commonly used to promote cotton boll cracking (Arnaud et al., 2010; Forlani et al., 2019; Larsson et al., 2014; Marsch-Martínez et al., 2012; Simonini et al., 2017; Zuñiga-Mayo et al., 2018).

As an important breeding trait for early maturity in upland cotton, early boll opening has long been a focus of breeders. Farmers use chemical defoliating agents in field plantings to induce cotton leaves to fall off early and accelerate cotton boll opening (Li et al., 2022). Moreover, although cotton bolls are a typical type of capsule, the mechanism by which they crack remains unclear. In this study, the AG subfamily genes of upland cotton were first identified; then, family analysis was performed using bioinformatics methods. The tissue-specific expression patterns of Gossypium hirsutum AG subfamily genes (GhAGs) were analyzed on the basis of transcriptome data from the upland cotton variety TM-1, and the tissue of Zhongmian113 was used as a template to analyze the expression patterns of GhAGs using qRT−PCR. To clarify the role of GhSHP1/AGL1 in upland cotton, we used virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) technology to reduce GhSHP1 transcript levels. Phenotypic changes paraffin sections of cotton boll shells at different developmental stages, and GhIND, GhFUL, GhALC, GhRPL and GhNST1 expression were observed and analyzed in the GhSHP1-silenced plants and controls. These findings increase our understanding of GhSHP1 and provide a theoretical basis for future research on the cracking mechanism of cotton bolls and for the cultivation of early-maturing and high-quality cotton varieties.

The AGAMOUS subfamily in the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana contains four genes: AGAMOUS (AG, AT4G18960) (Bowman et al., 1989; Yanofsky et al., 1990), SHATTERPROOF1 (SHP1/AGL1, AT3G58780), SHATTERPROOF2 (SHP2/AGL5, AT2G42830) (Liljegren et al., 2000; Ma et al., 1991) and SEEDSTICK (STK/AGL11, AT4G09960) (Pinyopich et al., 2003; Rounsley et al., 1995). The protein sequences of these four genes in A. thaliana were obtained from The Arabidopsis Information Resource website (TAIR, https://www.arabidopsis.org) as seed sequences. The AG subfamily protein sequences of 14 plant species (Supplementary Table S1) were obtained using BLAST searches and downloaded from the Phytozome website (https://phytozome-next.jgi.doe.gov/) and the Ensembl Plants website (https://plants.ensembl.org/index.html), with the expected value set to < e-50. The protein physicochemical properties of the GhAG subfamily genes were analyzed using the ExPASy website (https://www.ExPASy.org/). The subcellular localizations of GhAG subfamily genes were predicted using the WOLF PSORT website (https://wolfpsort.hgc.jp/).

We conducted multiple alignments of AG subfamily protein sequences from 15 plant species using the ClustalW tool, and a phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining (NJ) method with 1000 replications and the p distance method with pairwise deletions using MEGA 7.0 software (de Moura et al., 2017; Kumar et al., 2016). Visualization and beautification were then performed using the iTOL website (https://itol.embl.de/) (Letunic and Bork, 2019). The genomes and annotated files of Gossypium hirsutum, Gossypium raimondii and Gossypium arboretum are available on the Ensembl Plants website (https://plants.ensembl.org/index.html). Then, intraspecific collinearity analysis of upland cotton and interspecific collinearity analysis of the three Gossypium species were performed with TBtools (v.2.091) software, and the synonymous (Ks) and nonsynonymous (Ka) substitution rates of the upland cotton AG subfamily genes were calculated (Chen et al., 2020; Luo et al., 2024).

The sequences of the 2000-bp regions located upstream of the GhAG genes were obtained from CottonFGD (https://cottonfgd.net/) and utilized to identify cis-regulatory elements associated with GhAG genes through the PlantCARE program (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/). Excel software was employed to visualize the results derived from these predictions.

The expression patterns of AG subfamily genes in upland cotton were analyzed using RNA-seq data obtained from 13 distinct tissues of the upland cotton variety TM-1 (http://cotton.zju.edu.cn/). Gene expression levels were quantified based on fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped fragments (FPKM) values. Heatmaps depicting the expression patterns of GhAG subfamily genes were generated utilizing TBtools software.

Leaf rot soil and vermiculite were mixed 1:1 in a seedling cup and soaked until the surface was slightly wet. Intact seeds were selected and planted 1.5 cm below the soil. The artificial climate incubators were established with fixed conditions (16 h light/8 h darkness, 25°C, and 70% humidity) for growing the seedlings. The roots, stems, leaves, sepals, petals, ovaries, cotton shells and cotton fibers were sampled in the 1st, 4th to 5th and 11th to 17th weeks of cotton growth. Early opening bolls (Yuzhishi84-1) and late opening bolls (Ganmain12) varieties were planted, and cotton boll shell tissues from different development stages were collected. The samples were quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C for future use.

Total RNA was extracted utilizing an AFTSpin Complex Plant Fast RNA Extraction Kit (No. RK30122; ABclonal, China). The concentration, purity and integrity of the RNA were assessed using RNA electrophoresis and an ultramicro concentration detector. Reverse transcription was conducted utilizing a UnionScript First-Strand cDNA Synthesis Mix Kit (No. SR511; Genesand, China). Specific primers for five GhAGs were designed using Primer-BLAST (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/index.cgi) for qRT−PCR. The qRT−PCR assay was conducted utilizing BrightCycle Universal SYBR Green qPCR Mix with a UDG kit (No. RK21219; ABclonal, China) on a LightCycler® 96 Instrument (Roche, Switzerland). GhACTIN (Zhao et al., 2020) was utilized as an internal reference gene for qRT−PCR for normalization of transcript levels. The relative expression level of each gene was determined using the 2−ΔΔCT method. Three biological replicates were performed to ensure accuracy and reliability. Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS 27 software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). The least significant difference (LSD) test was employed to calculate P values to assess significance (Rao et al., 2013; Willems et al., 2008; Zhao et al., 2020).

GhSHP1 silencing was achieved with VIGS technology using a CLCrV carrier. The 463-bp target fragment of GhSHP1 was obtained using PCR amplification and integrated into the CLCrV vector. The recombinant plasmid was subsequently introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101. The transformed A. tumefaciens was then resuspended. After three hours in the dark, CLCrV: ChlI, the empty vector and CLCrV: GhSHP1 were mixed with the auxiliary bacteria at a ratio of 1:1. Finally, the mixed bacterial mixture was injected into the dorsal surface of the cotyledons of 7-day-old plants to produce GhSHP1-silenced cotton plants (CLCrV: GhSHP1), along with negative control (empty vector) and positive control (CLCrV: ChlI) plants. The plants were subjected to a 24-h incubation period in darkness prior to being cultured under standard conditions. When the leaves of the positive control plants were yellow, the target gene had been successfully silenced. The seedlings were subsequently transplanted into flowerpots for further cultivation. At 15 and 3 days postanthesis (DPA), the cotton boll shells were sampled as templates, and GhALC, GhFUL, GhIND, GhNST1 and GhRPL expression levels were detected using qRT−PCR.

Cotton boll shells were sampled at 0, 3, 5, 10 and 15 DPA and stored in FAA fixative. After the samples were fixed for more than 24 hours, they were dehydrated, dipped in wax, and embedded to generate paraffin sections (4 μm). The paraffin sections were subjected to staining with safranin O solution and plant solid green staining solution, followed by mounting in neutral balsam. The sections were observed using a Nikon Eclipse E100 microscope (Nikon, Japan), and images were acquired with a Nikon DS-U3 system.

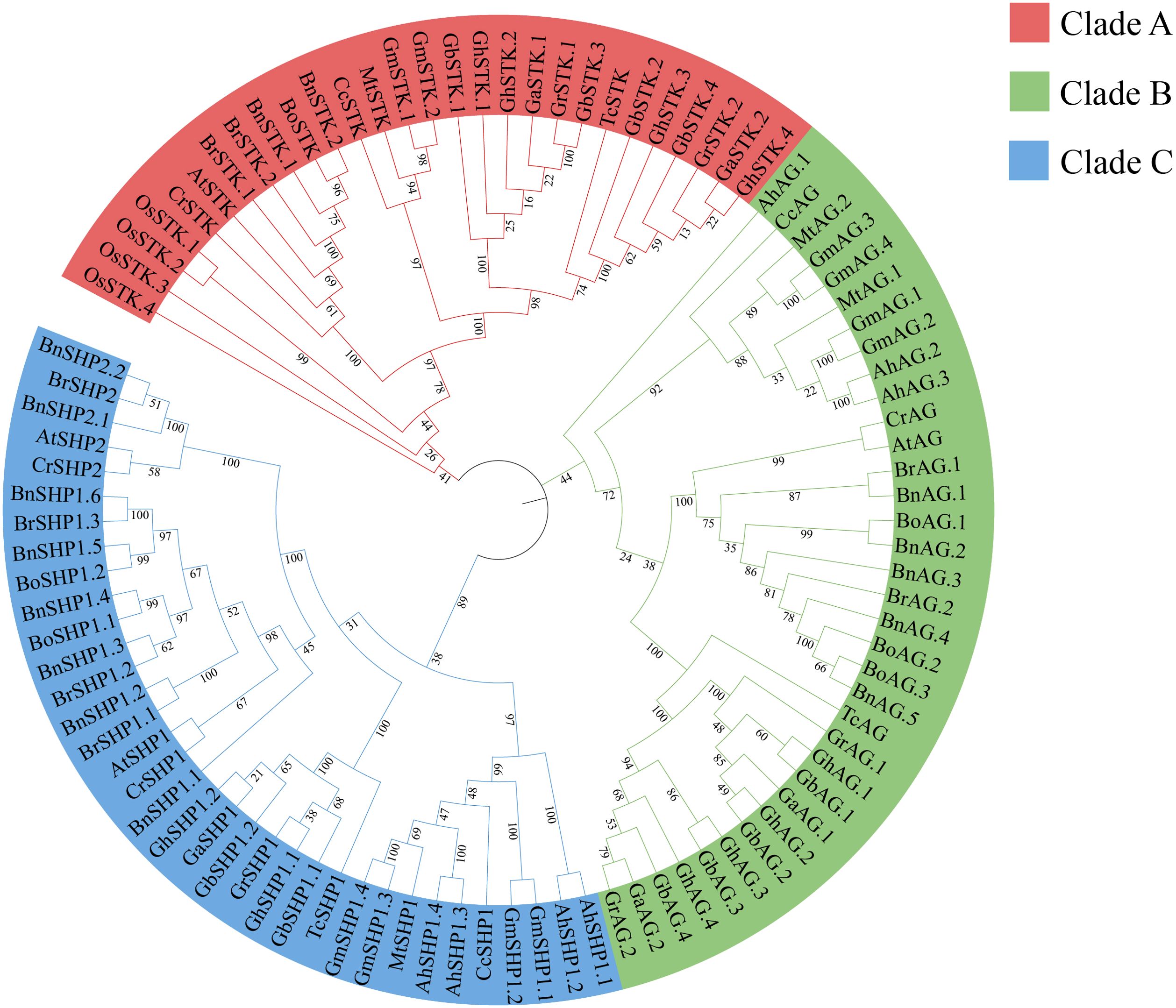

In this study, we identified ten AGAMOUS (AG) subfamily genes in upland cotton. On the basis of their homology with Arabidopsis thaliana AG subfamily genes in the phylogenetic tree, these genes were named GhAG.1, GhAG.2, GhAG.3, GhAG.4, GhSHP1.1, GhSHP1.2, GhSTK.1, GhSTK.2, GhSTK.3 and GhSTK.4 (Supplementary Table S1, Figure 1). The lengths and molecular weights of the ten GhAG proteins exhibited minimal variation, ranging from 223 to 246 amino acids (aa) and from 25.72 to 28.37 kDa, respectively. The isoelectric points of the ten GhAG proteins varied between 9.25 and 9.44, indicating that these proteins are alkaline. The instability index and average hydropathicity of the GhAG proteins varied from 48.47 to 62.44 and from -0.848 to -0.601, respectively. These results suggest that the GhAGs encode unstable hydrophilic proteins. Subcellular localization predictions suggested that these proteins were localized within the nucleus.

Figure 1. Evolutionary relationships of the AG subfamilies in 15 species. Gh, Gb, Gr, Ga, At, Bn, Br, Bo, Cr, Gm, Ah, Mt, Cc, Os and Tc represent Gossypium hirsutum, G. barbadense, G. raimondii, G. arboreum, Arabidopsis thaliana, Brassica napus, B. rapa ssp. pekinensis, B. oleracea capitata, Capsella rubella, Glycine max, Arachis hypogaea, Medicago truncatula, Cercis canadensis, Oryza sativa and Theobroma cacao, respectively.

To clarify the evolutionary relationships among the AG subfamily genes, a total of 98 AG subfamily genes (Supplementary Table S2) from 15 different species were employed to construct a phylogenetic tree. The phylogenetic tree was classified into three main branches (Figure 1). The numbers of genes contained in clades A (n= 28, 28.57%), B (n=35, 35.71%) and C (n=35, 35.71%) were similar. Among the ten GhAG genes, four, four and two GhAGs clustered with AtAG, AtSTK/AGL11, and AtSHP1/AGL1, respectively. However, no homologs of AtSHP2/AGL5 were found among the GhAGs, GbAGs, GaAGs or GrAGs. Among the other ten species, genes homologous to AtSHP2 were found in only three silique species (Bn, Br and Cr).

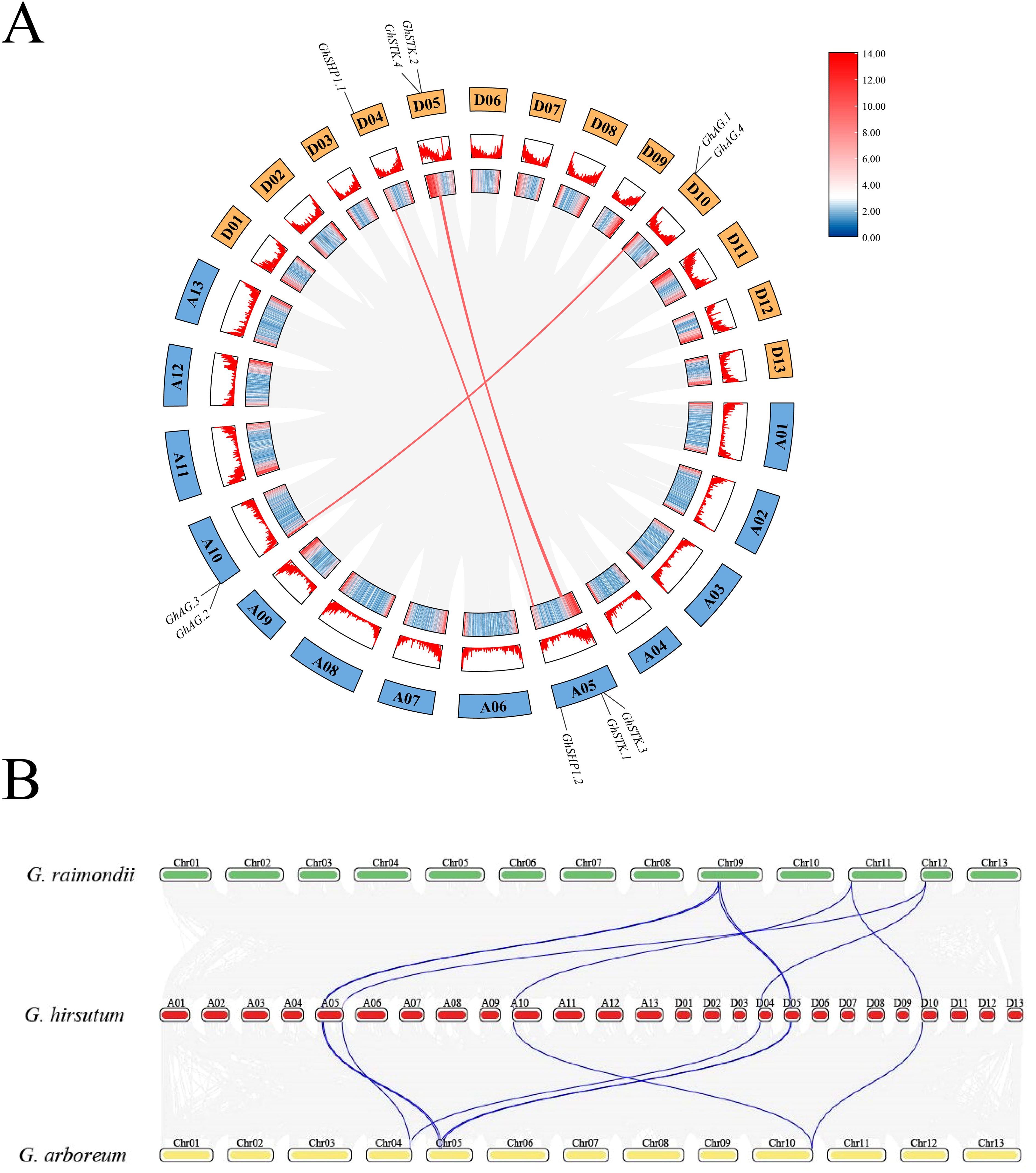

To investigate the expansion pattern of the AG subfamily in the three Gossypium species, collinearity analysis of the AG subfamily genes was performed. The results revealed four homologous duplicate gene pairs in upland cotton (Figure 2A), three of which were tandem duplications and one of which was a segmental duplication. The Ka: Ks ratios of the GhAG members were less than 0.30, suggesting that purifying selection has played a significant role in the evolutionary processes of genes within the GhAG subfamily (Supplementary Table S3). In addition, we found that most GhAG genes presented a collinear relationship with the GaAG and GrAG genes (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Intraspecific and interspecies replication analysis of AG subfamily genes. (A) Patterns of GhAG subfamily gene duplication in the genome of upland cotton. (B) Collinearity analysis of the three cotton species. G. raimondii is shown in green, G. hirsutum is shown in red, and G. arboreum is shown in yellow.

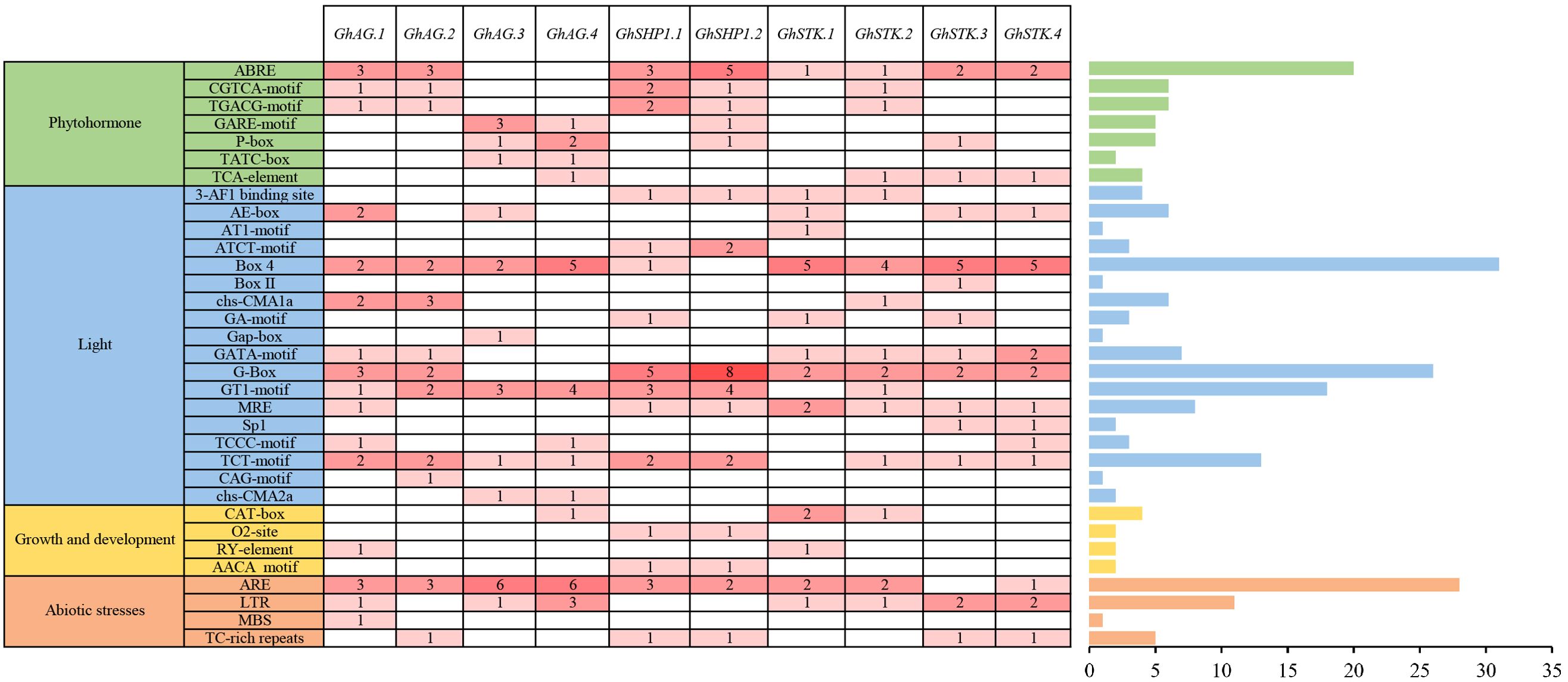

To predict the potential biological functions of the GhAG subfamily genes, we analyzed the cis-acting elements present in their promoters. The cis-acting elements associated with GhAGs can be classified into four primary categories: phytohormone-responsive elements, light-responsive elements, plant growth and development-responsive elements, and abiotic stress-responsive elements (Figure 3). Among these categories, light-responsive elements constituted the majority of the cis-regulatory components within the promoters of the GhAGs, whereas elements responsive to plant growth and development constituted the smallest proportion. Among the light-responsive elements, Box 4 (31) was the most common and was present in the promoters of almost all the GhAG genes. Furthermore, a total of 20 ABREs associated with the ABA hormone response and 28 ARE elements related to the abiotic stress response were identified in the promoters of the GhAGs. CAT-box elements accounted for the largest number of elements responsive to growth and development, with only four. These findings indicate that GhAGs not only play a significant role in plant hormone regulation but are also associated with the response to abiotic stress.

Figure 3. Cis-acting elements located within the promoter regions of GhAG genes. The Arabic numerals in the cells denote the quantity of cis-acting elements present.

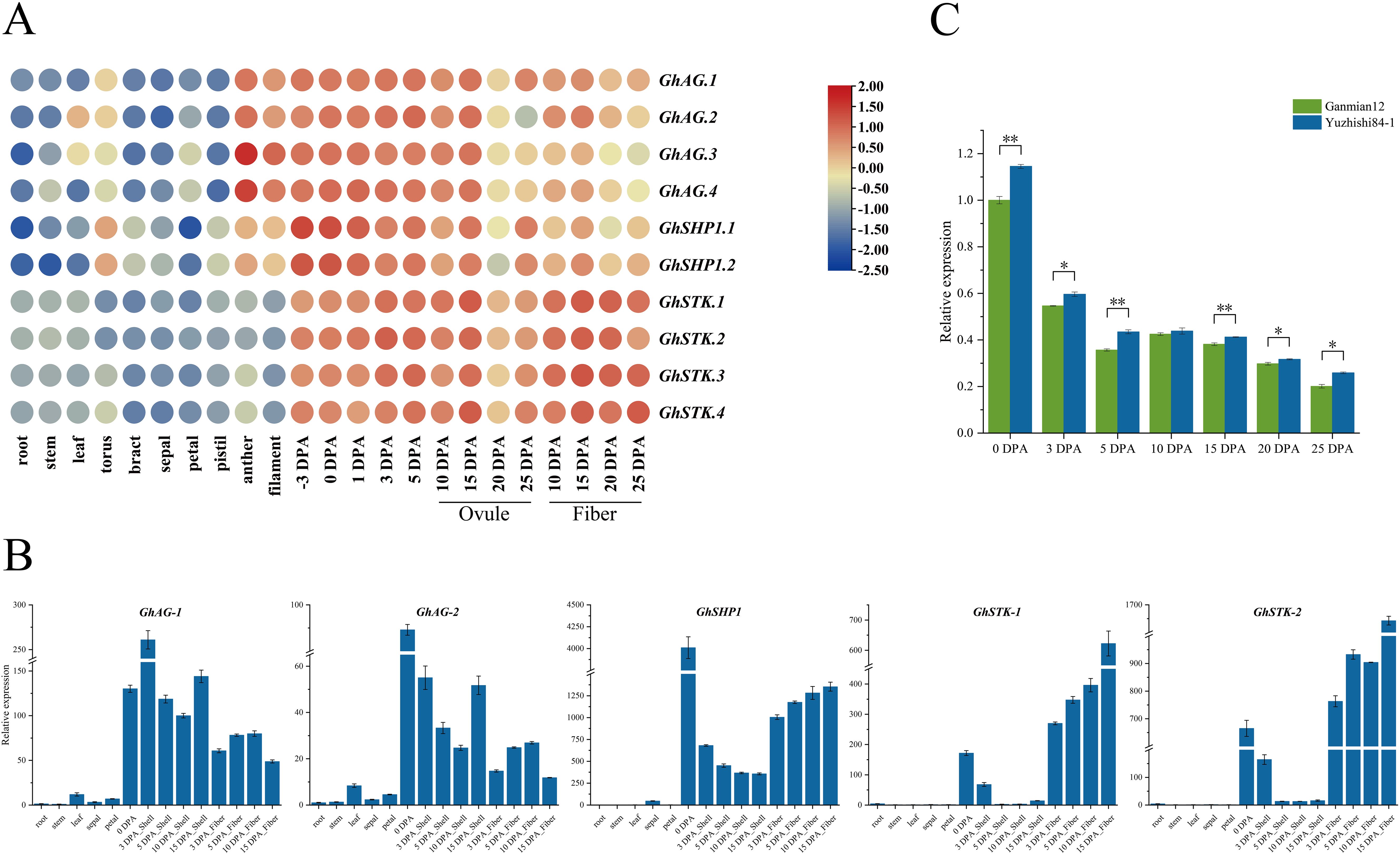

The expression patterns of genes are closely linked to their biological functions, which leads to contrasting features between species (Hu et al., 2019). To investigate the expression patterns of GhAG subfamily genes, we used FPKM values from transcriptome data to generate heatmaps to characterize gene expression levels across various tissues. The transcriptome data of different TM-1 tissues included data from root, stem, leaf, torus, bract, sepal, petal, pistil, anther, filament, ovule and cotton fiber tissues (Figure 4A). We found that GhAG subfamily genes presented relatively low expression levels in vegetative tissues, such as roots, stems and leaves, and presented three types of expression patterns in reproductive organs, such as flowers and fruits (Figure 4A). GhAG.1, GhAG.2, GhAG.3 and GhAG.4 expression was consistent with the type I pattern, and these genes were expressed mainly in the anthers and filaments and during the early stage of ovule and fiber development (-3 to 15 DPA). The GhSHP1.1 and GhSHP1.2 expression patterns were type II, with high expression occurring mainly during early ovule and fiber development (-3 to 15 DPA), especially three days before flowering and on the day of flowering. The GhSTK.1, GhSTK.2, GhSTK.3 and GhSTK.4 expression patterns were type III, with high expression mainly in ovules (15 DPA) and fibers during the late development period (15 to 25 DPA). It follows that GhAG subfamily genes are highly likely to affect floral organs as well as the development of later ovules and fibers.

Figure 4. Analysis of the expression patterns of GhAG subfamily genes across various tissues in upland cotton. (A) Expression patterns of GhAG subfamily genes in different tissues of TM-1. The color of the continuous gradation represents the expression level. Red represents high expression, and blue represents low expression. (B) Expression patterns of GhAG subfamily genes in different tissues of ZM113. (C) GhSHP1 expression in the cotton boll shell tissues of early and late opening boll varieties.

Given that the above transcriptome data did not include the expression of GhAG subfamily genes in cotton boll shells, we further identified the expression patterns of GhAGs across various tissues of ZM113 (roots, stems, leaves, sepals, petals, cotton boll shells and fibers) using qRT−PCR. The qRT−PCR primers were not effective in distinguishing between GhAG.1 and GhAG.2, GhAG.3 and GhAG.4, GhSHP1.1 and GhSHP1.2, GhSTK.1 and GhSTK.2, and GhSTK.3 and GhSTK.4. Therefore, we named the above gene pairs GhAG-1, GhAG-2, GhSHP1, GhSTK-2 and GhSTK-1 and detected their expression in different tissues of ZM113 (Figure 4B). We found that GhSHP1 was highly expressed in both cotton boll shell and fiber tissues during the later stage of growth and development and that GhSHP1 transcript levels were greater than that of GhAG-1, GhAG-2, GhSTK-1 and GhSTK-2 in cotton boll shells. After comprehensive analysis, GhSHP1 was selected as the target gene.

To further verify whether GhSHP1 affects cotton boll cracking, qRT−PCR was used to study the difference in GhSHP1 expression in the cotton boll shell tissues of early (Yuzhishi84-1) and late (Ganmian12) opening bolls varieties at different growth stages and during boll shell cracking (Figure 4C). The results revealed that GhSHP1 expression in the cotton boll shell of Yuzhishi84-1 was greater than that in the boll shell of Ganmian12. The difference is significant at 0, 3, 5, 15, 20 and 25 DPA. In summary, we hypothesized that GhSHP1 may play a regulatory role in the development of cotton boll shells.

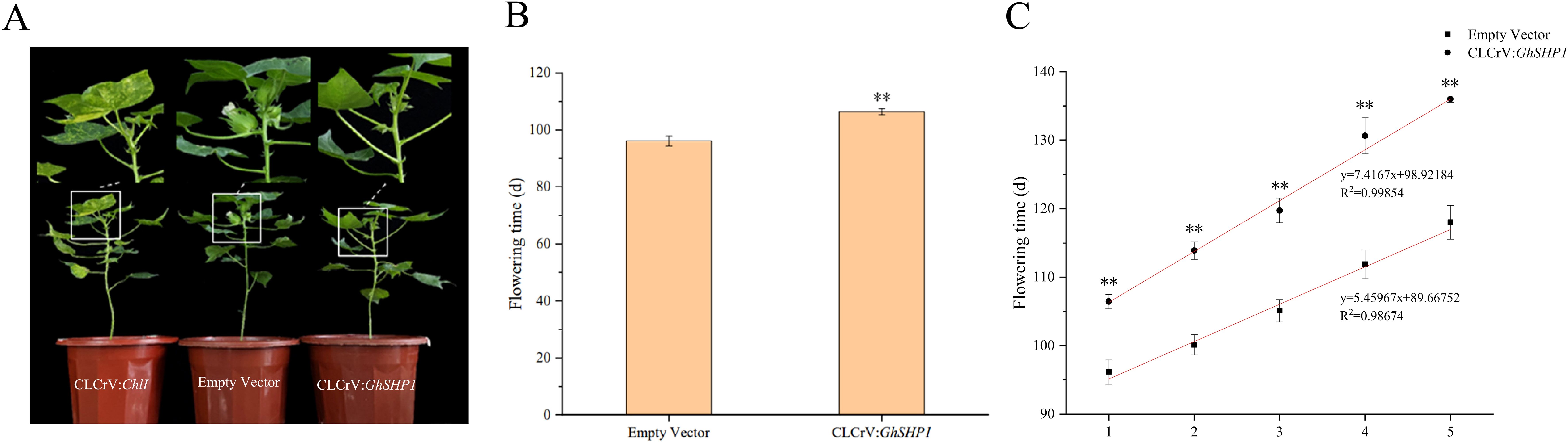

To assess the functions of GhSHP1, we employed VIGS technology to suppress its expression. Approximately 21 days after viral infection, the CLCrV: ChlI positive control plants were yellow, indicating that virus-induced silencing was successful in upland cotton plants (Figure 5A). The first flowering time, first five flowering times and cracking time of the silenced CLCrV: GhSHP1 plants and empty vector plants were analyzed statistically. We found that the flowering time of the CLCrV: GhSHP1 plants was approximately 10.3 days later than that of the empty vector plants (Figure 5B). The flowering times of the first five flowers were measured to analyze whether silencing the GhSHP1 gene affected the flowering concentration of upland cotton. The scatterplot of the flowering times of the first five flowers was analyzed using linear regression, and the results revealed that silencing GhSHP1 caused the flowering time of the upland cotton plants to be less concentrated (Figure 5C). These findings indicated that GhSHP1 gene silencing not only delayed the flowering time of upland cotton but also reduced the flowering concentration.

Figure 5. Phenotypic analysis of VIGS-treated upland cotton at the flowering stage. (A) Flowering phenotypes of plants treated with CLCrV: ChlI, empty vector, or CLCrV: GhSHP1. (B) Statistical analysis of the first flowering time of upland cotton. (C) Statistical analysis of the first five flowering times of upland cotton.

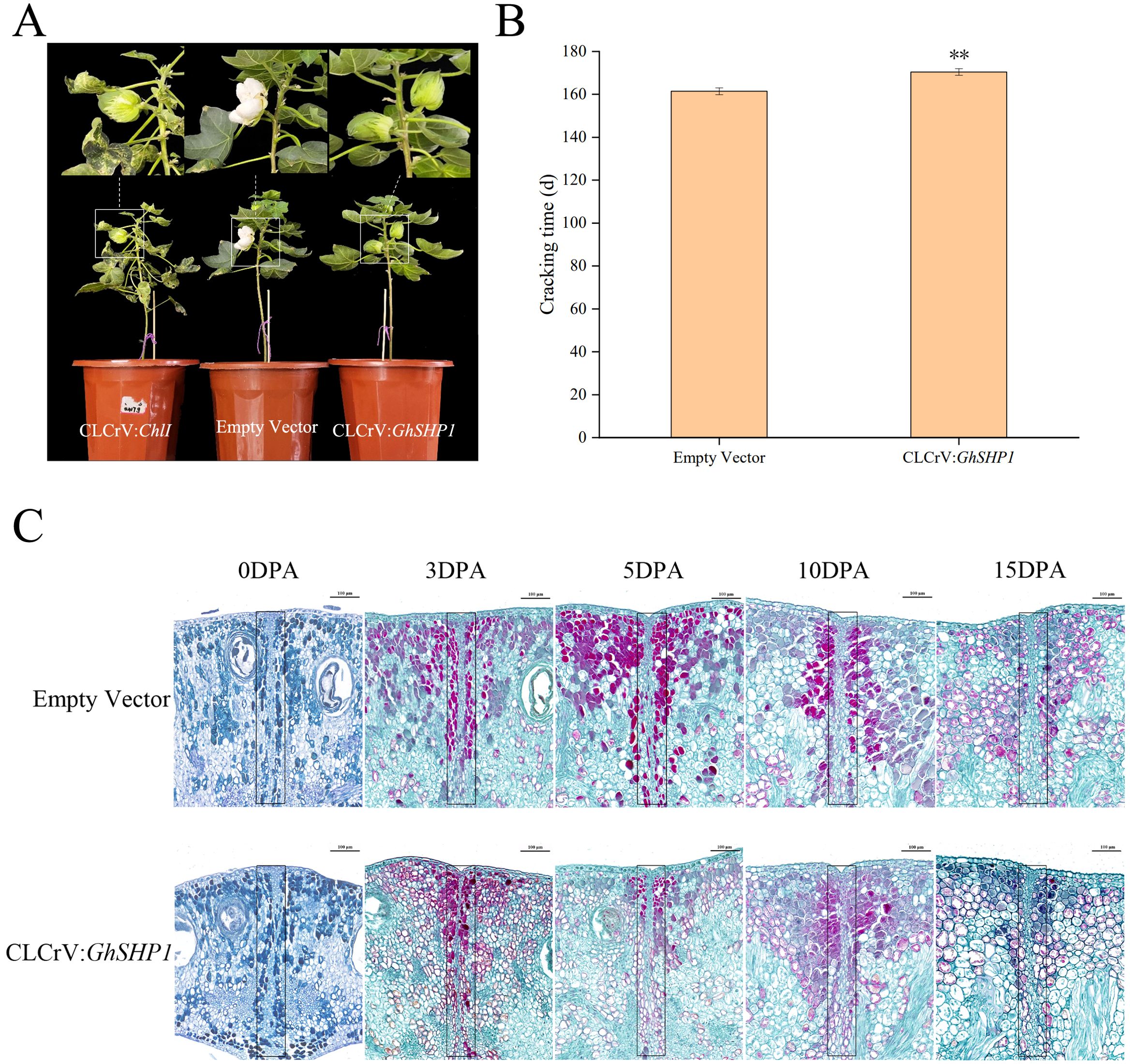

Further observations indicated that the boll opening time of the CLCrV: GhSHP1-silenced cotton plants was approximately 9.0 days longer than that of the empty vector control plants (Figures 6A, B). Paraffin sections of cotton bollback sutures collected at different time points were observed under a microscope. The factors influencing the cracking time of the cotton bolls were analyzed from a cytological point of view (Figure 6C). In this image, the red cells are lignified cells colored with safranin O. On the left and right are the valves, and in the middle of them are the valve margins and the dehiscence zone (DZ). The outermost rectangular layer of cells in the valve is the ectocarp, and the inside layer is the mesocarp. During the early stage of fruit development, the DZ between adjacent valves is composed of numerous small square cells closely arranged in a line. However, until 3 DPA, the formation of such compact small cells could not be clearly observed in the CLCrV: GhSHP1-silenced plants. By examining paraffin sections of cotton boll shells at 0, 3, 5, 10, and 15 DPA, we observed that the DZ cells in the CLCrV: GhSHP1-silenced plants were thinner than those in the empty vector plants. On the other hand, at 3 DPA, unique lignified cells were observed on the back sutures of the cotton boll in both the empty vector plants and the silenced plants. At 5, 10 and 15 DPA, the plants transformed with empty vector exhibited more lignified cells than did the silenced plants. Near the DZ is the valve margin, where the lignification of cells and the inner cell layer of the valve results in pod shattering (Giménez et al., 2010). As the fruit ripens and dries, the parenchyma cells of the cotton boll valve shrink, creating tension in the hard lignified area, which helps the DZ shatter (Liljegren et al., 2000). This could cause the bolls of the empty vector-transformed plants to crack earlier than those of the CLCrV: GhSHP1-silenced plants.

Figure 6. Phenotype and paraffin section analysis of upland cotton during the boll opening period. (A) Cotton boll cracking phenotypes of plants treated with CLCrV: ChlI, empty vector, or CLCrV: GhSHP1. (B) Statistical analysis of the boll cracking time of upland cotton. (C) Paraffin sections of cotton boll shell back sutures from empty vector-transformed plants and CLCrV: GhSHP1-silenced plants. The dehiscence zones are marked with a black frame. Scale bar = 100 μm.

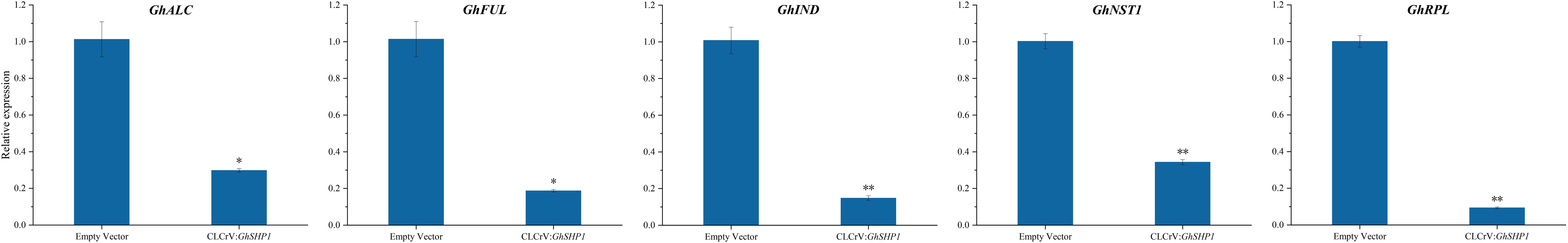

ALCATRAZ (ALC), FRUITFULL (FUL), INDEHISCENT (IND), NAC SECONDARY WALL THICKENING PROMOTING FACOTR1 (NST1) and REPLUMLESS (RPL) are key genes involved in regulating pod shattering in A. thaliana (Dong and Wang, 2015). GhALC, GhFUL, GhIND, GhNST1 and GhRPL expression characteristics were examined in both the CLCrV: GhSHP1-silenced plants and the control plants. The expression levels of these five genes in the control plants were markedly greater than those in the GhSHP1-silenced plants (Figure 7). These results indicated that GhSHP1 silencing strongly affected the expression of cracking-related genes, indicating that GhSHP1 could be an important gene in the cotton boll opening regulatory network.

Figure 7. Quantitative analysis of key genes associated with fruit shattering in both control plants and GhSHP1-silenced plants. Asterisks denote significant differences in the expression levels of related genes between silenced and control plants (*P<0.05, **P<0.01).

In plants, fruit cracking is affected by fruit size, shape, growth rate, water content, skin characteristics, internal fruit cracking-related gene expression and external factors such as temperature, light, and precipitation (Hu et al., 2024). These factors ultimately act on the outer peel, which is unable to withstand the expansion force from inside the peel and cracks (Correia et al., 2018; Khadivi-Khub, 2015; Li et al., 2021). The split fruit can also be subdivided into the following four fruit types: silique, legume, capsule, and follicle (Hernandez et al., 2023). The fruit of A. thaliana is a silique that develops from two symbiotic carpels, with a lateral membranous placenta and a replum that is generated at the ventral suture of the carpel to divide the ovary into two chambers. When the siliques are ripe, the peel cracks along both sides of the abdominal suture and falls off in two pieces. The fruit of soybean is the legume, and the pod is the fruit formed by the development of a single carpel. At maturity, it splits along the abdominal suture and the back suture simultaneously, and the peel splits into two pieces. The fruit of cotton is the capsule. The cotton boll develops from a compound pistil of a conjunctive carpellary and has an axial placenta. It is usually formed by the carpel, with three to five chambers. The fruit ripens and cracks in a way known as loculicidal dehiscence, along the sutures of the back. Follicles develop from a single carpellary pistil or from the apocarpous gynoecium. When ripe, the fruit will split along one side of the dorsal or abdominal suture.

Members of the MADS-box family are integral to various aspects of plant biology, including flower and seed development, the regulation of flowering time, fruit maturation processes, and responses to both abiotic and biotic stresses (Schilling et al., 2018). To date, genes belonging to this family have been reported in A. thaliana, rice, soybean, tomato and other plants. The target genes identified in this study are classified within the AGAMOUS subfamily of the MADS-box family, and bioinformatics analysis of the identified GhAGs was performed. Ten AG subfamily genes were identified in upland cotton. This result is consistent with a report from Ren et al (Ren et al., 2017). The greatest number of AGs was detected in Brassica napus (15) (Wu et al., 2018). This was followed by the tetraploid cotton G. hirsutum (10) and G. barbadense (10), as well as the legume crop Glycine max (10) (Nardeli et al., 2018; Shu et al., 2013). Furthermore, phylogenetic analyses revealed that AG subfamily genes have undergone a series of genome amplification events during the evolutionary transition of cotton from diploid to tetraploid forms. This process doubled the number of AG subfamily genes within the allotetraploid cotton species G. hirsutum and G. barbadense compared with G. raimondii and G. arboreum. AtSHP2 homologous genes were found only in Bn, Br and Cr but not in the other 11 species. This may be due to gene loss that occurred during the evolutionary process. In this study, four AG subfamily genes were identified in Oryza sativa, whereas five OsAGs were identified by Ren et al (Ren et al., 2017). This discrepancy may arise from the utilization of different reference genomes or from inconsistencies in the screening criteria employed. These findings suggested that the AG subfamily genes share a common origin and that different species evolved different numbers of AG subfamily genes during evolution.

Most AG subfamily genes in upland cotton presented one-to-one collinearity. A good collinearity relationship was noted with the other two cotton species. The Ka: Ks ratios for all the members of the GhAG subfamily were less than 1. Ka/Ks values can determine whether selection pressure is acting on the gene that encodes the protein. If Ka/Ks is > 1, it indicates a positive selection effect. If Ka/Ks = 1, this suggests neutral selection. If Ka/Ks is < 1, it is indicative of purifying selection. These findings indicate that purifying selection has played a significant role in the evolutionary development of GhAG subfamily genes. An examination of the cis-acting elements within promoters revealed that the majority of them were light-responsive elements, and all of them were located in the nucleus. Taken together with the results of the expression pattern analysis, these findings suggest that GhAGs are likely to play regulatory roles in plant growth and development by affecting flower organs and fruits. This is consistent with findings from prior research (Dreni et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2016, 2018; Lu et al., 2019; ÓMaoiléidigh et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2017).

To further investigate the effect of GhSHP1 on cotton boll cracking, we conducted a VIGS experiment. Compared with those of the control plants, the flowering and boll cracking times of the GhSHP1-silenced plants were delayed. Paraffin sections were prepared at the suture line on the posterior side of the cotton boll. The findings indicated that the development of the DZ in the silenced plants occurred later than that observed in the control plants during the same timeframe; furthermore, the extent of valve lignification was lower in the silenced plants than in the control plants. GhSHP1 may affect cotton boll cracking by regulating DZ development. Research has demonstrated that, in A. thaliana, AtSHP1/2 plays a role in promoting the differentiation of the DZ while simultaneously promoting the lignification of adjacent cells (Liljegren et al., 2000). In Brassica napus, BnSHP5-184 with five homologous mutants was obtained using the CRISPR-Cas9 system, and fewer lignification and separation layers were found in and around the valve. BnSHP1A09 may be a promising site for controlling the DZ lignin content (Zaman et al., 2021). In fleshy tomato fruits, the AtSHP1/2 homologous gene TOMATO AGAMOUS-LIKE1 (TAGL1) promotes fruit ripening (Itkin et al., 2009; Jeon et al., 2024; Vrebalov et al., 2009). TAGL1 overexpression in A. thaliana leads to a phenotype that closely resembles the phenotype observed with SHP1/2 overexpression. The functions of SHP in these species are similar, and there is no difference in function due to different fruit types. These findings suggest that the role of SHP1/2 genes in determining organ identity is fundamentally conserved (Pinyopich et al., 2003).

Fruit dehiscence is caused by a combination of many factors in the plant, which form a complex regulatory network. To further investigate the role of GhSHP1 in the regulatory network of cotton boll cracking, we selected five key genes in the tissue differentiation regulatory network required for A. thaliana pod fragmentation. In this study, qRT−PCR analysis revealed a significant decrease in the expression levels of the five genes in plants with silenced GhSHP1. Therefore, a positive regulatory relationship may exist between GhSHP1 and these five genes. In contrast, FUL exerts a negative regulatory effect on SHP1/2 within the regulatory network governing pod cracking in A. thaliana (Ferrándiz et al., 2000). In FUL1/2 RNAi-treated fruits, the expression of the tomato gene TAGL1 was upregulated in the peel, indicating a negative regulatory relationship between FUL1/2 and TAGL1 (Bemer et al., 2012). Moreover, for key genes in the A. thaliana pod-shattering regulatory pathway, we predicted the protein interaction network of upland cotton homologous genes (Supplementary Figure S1). These findings indicate that GhSHP1 expression may be directly correlated with GhIND and GhRPL expression. Therefore, GhSHP1 may have an indirect regulatory relationship with both GhFUL and GhALC. This may explain why the expression levels of these four genes differed significantly between the GhSHP1-silenced plants and the control plants.

In summary, we identified 10, 10, 5 and 5 AGAMOUS subfamily genes in G. hirsutum, G. barbadense, G. raimondii and G. arboreum, respectively. We conducted bioinformatic analyses of the GhAGs, including phylogenetic studies, collinearity assessments, repeated event evaluations, investigations of promoter cis-acting elements, and expression pattern analyses. The GhAG promoter sequences include numerous light-responsive elements as well as elements associated with plant hormones. Expression pattern analysis revealed that GhAGs may affect the development of flower organs, ovules, cotton boll shells and fibers during the later stages of growth and development. In addition, on the basis of the VIGS experiment results, we concluded that silencing the GhSHP1 gene led to delayed flowering and boll opening in upland cotton. The results of the paraffin section analysis indicate that GhSHP1 may affect the cracking time of cotton bolls by influencing the development of the DZ at the back suture line of the cotton boll shell. This study provides a reference for future studies of key genes affecting cotton boll cracking and for the molecular breeding of early-maturing cotton varieties.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

WX: Data curation, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. QM: Writing – review & editing, Validation. JJ: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Software. XZ: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. WY: Software, Writing – review & editing, Methodology. HH: Writing – review & editing, Software, Validation. CW: Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. GW: Funding acquisition, Resources, Writing – review & editing. JS: Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Resources, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32260478) and the Natural Science Foundation of the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (2023CB007-09). Natural Science Support Program Project of the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (2024DA017).

The author is especially thankful to Qifeng Ma, Institute of Cotton Research of CAAS, for the CLCrV vectors and Cotton Research Institute.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as potential conflicts of interest.

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2025.1558293/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Table 1 | Physicochemical properties of the AG subfamily members in upland cotton.

Supplementary Table 2 | Species information in phylogenetic evolutionary trees.

Supplementary Table 3 | Ka/Ks analysis of AG subfamily genes in upland cotton.

Supplementary Figure 1 | Interaction network between the GhSHP1 protein and key shatter-related proteins.

Arnaud, N., Girin, T., Sorefan, K., Fuentes, S., Wood, T. A., Lawrenson, T., et al. (2010). Gibberellins control fruit patterning in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genes. Dev. 24, 2127–2132. doi: 10.1101/gad.593410

Ballester, P., Ferrándiz, C. (2017). Shattering fruits: variations on a dehiscent theme. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 35, 68–75. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2016.11.008

Bemer, M., Karlova, R., Ballester, A. R., Tikunov, Y. M., Bovy, A. G., Wolters-Arts, M., et al. (2012). The tomato FRUITFULL homologs TDR4/FUL1 and MBP7/FUL2 regulate ethylene-independent aspects of fruit ripening. Plant Cell. 24, 4437–4451. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.103283

Bowman, J. L., Smyth, D. R., Meyerowitz, E. M. (1989). Genes directing flower development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 1, 37–52. doi: 10.1105/tpc.1.1.37

Chen, C., Chen, H., Zhang, Y., Thomas, H. R., Frank, M. H., He, Y., et al. (2020). TBtools: an integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol. Plant 13, 1194–1202. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2020.06.009

Chen, G., Wu, X., Zhu, Z., Li, T., Tang, G., Liu, L., et al. (2024). Bioinformatic and phenotypic analysis of atPCP-ba crucial for silique development in arabidopsis. Plants. 13, 2614–2614. doi: 10.3390/plants13182614

Correia, S., Schouten, R., Silva, A. P., Gonçalves, B. (2018). Sweet cherry fruit cracking mechanisms and prevention strategies: a review. Sci. Hortic. 240, 369–377. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2018.06.042

de Moura, S. M., Artico, S., Lima, C., Nardeli, S. M., Berbel, A., Oliveira-Neto, O. B., et al. (2017). Functional characterization of AGAMOUS-subfamily members from cotton during reproductive development and in response to plant hormones. Plant Reprod. 30, 19–39. doi: 10.1007/s00497-017-0297-y

Dinneny, J. R., Yanofsky, M. F. (2005). Drawing lines and borders: how the dehiscent fruit of Arabidopsis is patterned. Bioessays. 27, 42–49. doi: 10.1002/bies.20165

Dong, Y., Wang, Y. (2015). Seed shattering: from models to crops. Front. Plant Sci. 6. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00476

Dreni, L., Pilatone, A., Yun, D., Erreni, S., Pajoro, A., Caporali, E., et al. (2011). Functional analysis of all AGAMOUS subfamily members in rice reveals their roles in reproductive organ identity determination and meristem determinacy. Plant Cell. 23, 2850–2863. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.087007

Ferrándiz, C. (2002). Regulation of fruit dehiscence in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 53, 2031–2038. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erf082

Ferrándiz, C., Liljegren, S. J., Yanofsky, M. F. (2000). Negative regulation of the SHATTERPROOF genes by FRUITFULL during Arabidopsis fruit development. Science. 289, 436–438. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5478.436

Ferrándiz, C., Pelaz, S., Yanofsky, M. F. (1999). Control of carpel and fruit development in Arabidopsis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 68, 321–354. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.321

Forlani, S., Masiero, S., Mizzotti, C. (2019). Fruit ripening: the role of hormones, cell wall modifications, and their relationship with pathogens. J. Exp. Bot. 70, 2993–3006. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erz112

Giménez, E., Pineda, B., Capel, J., Antón, M. T., Atarés, A., Pérez-Martín, F., et al. (2010). Functional analysis of the Arlequin mutant corroborates the essential role of the ARLEQUIN/TAGL1 gene during reproductive development of tomato. PloS One 5, e14427. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014427

Gu, Q., Ferrándiz, C., Yanofsky, M. F., Martienssen, R. (1998). The FRUITFULL MADS-box gene mediates cell differentiation during Arabidopsis fruit development. Development. 125, 1509–1517. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.8.1509

Hernandez, J. O., Naeem, M., Zaman, W. (2023). How does changing environment influence plant seed movements as populations of dispersal vectors decline? Plants. 12, 1462. doi: 10.3390/plants12071462

Hu, Y., Chen, J., Fang, L., Zhang, Z., Ma, W., Niu, Y., et al. (2019). Gossypium barbadense and Gossypium hirsutum genomes provide insights into the origin and evolution of allotetraploid cotton. Nat. Genet. 51, 739–748. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0371-5

Hu, Y., Li, Y., Zhu, B., Huang, W., Chen, J., Wang, F., et al. (2024). Genome-wide identification of the expansin gene family in netted melon and their transcriptional responses to fruit peel cracking. Front. Plant Sci. 15. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2024.1332240

Itkin, M., Seybold, H., Breitel, D., Rogachev, I., Meir, S., Aharoni, A. (2009). TOMATO AGAMOUS-LIKE 1 is a component of the fruit ripening regulatory network. Plant J. 60, 1081–1095. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.04064.x

Jeon, C., Chung, M., Lee, J. M. (2024). Reassessing the contribution of TOMATO AGAMOUS-LIKE1 to fruit ripening by CRISPR/cas9 mutagenesis. Plant Cell Rep. 43, 41. doi: 10.1007/s00299-023-03105-7

Khadivi-Khub, A. (2015). Physiological and genetic factors influencing fruit cracking. Acta Physiol. Plant 37, 14. doi: 10.1007/s11738-014-1718-2

Kumar, S., Stecher, G., Tamura, K. (2016). MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33, 1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054

Larsson, E., Roberts, C. J., Claes, A. R., Franks, R. G., Sundberg, E. (2014). Polar auxin transport is essential for medial versus lateral tissue specification and vascular-mediated valve outgrowth in Arabidopsis gynoecia. Plant Physiol. 166, 1998–2012. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.245951

Letunic, I., Bork, P. (2019). Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v4: recent updates and new developments. Nucleic. Acids Res. 47, W256–W259. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz239

Lewis, M. W., Leslie, M. E., Liljegren, S. J. (2006). Plant separation: 50 ways to leave your mother. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 9, 59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2005.11.009

Li, H., Liu, G., Tian, H., Fu, D. (2021). Fruit cracking: a review. Sheng Wu Gong Cheng Xue Bao. 37, 2737–2752. doi: 10.13345/j.cjb.200553

Li, F., Wu, Q., Liao, B., Yu, K., Huo, Y., Meng, L., et al. (2022). Thidiazuron promotes leaf abscission by regulating the crosstalk complexities between ethylene, auxin, and cytokinin in cotton. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 (5), 71–85. doi: 10.3390/ijms23052696

Liljegren, S. J., Ditta, G. S., Eshed, Y., Savidge, B., Bowman, J. L., Yanofsky, M. F. (2000). SHATTERPROOF MADS-box genes control seed dispersal in Arabidopsis. Nature. 404, 766–770. doi: 10.1038/35008089

Liljegren, S. J., Roeder, A. H. K., Kempin, S. A., Gremski, K., Østergaard, L., Guimil, S., et al. (2004). Control of fruit patterning in Arabidopsis by INDEHISCENT. Cell. 116, 843–853. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00217-x

Liu, Z., Xiong, H., Li, L., Fei, Y. (2018). Functional conservation of an AGAMOUS orthologous gene controlling reproductive organ development in the gymnosperm species Taxus chinensis var. mairei. J. Plant Biol. 61, 50–59. doi: 10.1007/s12374-017-0154-4

Liu, Y., Zhang, D., Ping, J., Li, S., Chen, Z., Ma, J. (2016). Innovation of a regulatory mechanism modulating semi-determinate stem growth through artificial selection in soybean. PloS Genet. 12, e1005818. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005818

Lu, H., Klocko, A. L., Brunner, A. M., Ma, C., Magnuson, A. C., Howe, G. T., et al. (2019). RNA interference suppression of AGAMOUS and SEEDSTICK alters floral organ identity and impairs floral organ determinacy, ovule differentiation, and seed-hair development in Populus. New Phytol. 222, 923–937. doi: 10.1111/nph.15648

Luo, J., Li, M., Ju, J., Hai, H., Wei, W., Ling, P., et al. (2024). Genome-wide identification of the ghANN gene family and functional validation of ghANN11 and ghANN4 under abiotic stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25, 1877–1877. doi: 10.3390/ijms25031877

Ma, H., Yanofsky, M. F., Meyerowitz, E. M. (1991). AGL1-AGL6, an Arabidopsis gene family with similarity to floral homeotic and transcription factor genes. Genes. Dev. 5, 484–495. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.3.484

Marsch-Martínez, N., Ramos-Cruz, D., Irepan-Reyes-Olalde, J., Lozano-Sotomayor, P., Zúñiga-Mayo, V. M., de Folter, S. (2012). The role of cytokinin during Arabidopsis gynoecia and fruit morphogenesis and patterning. Plant J. 72, 222–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.05062.x

Mitsuda, N., Ohme-Takagi, M. (2008). NAC transcription factors NST1 and NST3 regulate pod shattering in a partially redundant manner by promoting secondary wall formation after the establishment of tissue identity. Plant J. 56, 768–778. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03633.x

Nardeli, S. M., Artico, S., Aoyagi, G. M., de Moura, S. M., Da Franca Silva, T., Grossi-de-Sa, M. F., et al. (2018). Genome-wide analysis of the MADS-box gene family in polyploid cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) and in its diploid parental species (Gossypium arboreum and Gossypium raimondii). Plant Physiol. Biochem. 127, 169–184. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2018.03.019

Ogawa, M., Kay, P., Wilson, S., Swain, S. M. (2009). ARABIDOPSIS DEHISCENCE ZONE POLYGALACTURONASE1 (ADPG1), ADPG2, and QUARTET2 are polygalacturonases required for cell separation during reproductive development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 21, 216–233. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.063768

ÓMaoiléidigh, D. S., Wuest, S. E., Rae, L., Raganelli, A., Ryan, P. T., Kwasniewska, K., et al. (2013). Control of reproductive floral organ identity specification in Arabidopsis by the c function regulator AGAMOUS. Plant Cell. 25, 2482–2503. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.113209

Pinyopich, A., Ditta, G. S., Savidge, B., Liljegren, S. J., Baumann, E., Wisman, E., et al. (2003). Assessing the redundancy of MADS-box genes during carpel and ovule development. Nature. 424, 85–88. doi: 10.1038/nature01741

Rajani, S., Sundaresan, V. (2001). The Arabidopsis myc/bHLH gene ALCATRAZ enables cell separation in fruit dehiscence. Curr. Biol. 11, 1914–1922. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00593-0

Rao, X., Huang, X., Zhou, Z., Lin, X. (2013). An improvement of the 2^ (-delta delta CT) method for quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction data analysis. Biostat Bioinforma Biomath. 3, 71–85. doi: 10.1016/S0920-5489(99)92176-1

Ren, Z., Yu, D., Yang, Z., Li, C., Qanmber, G., Li, Y., et al. (2017). Genome-wide identification of the MIKC-type MADS-box gene family in Gossypium hirsutum L. Unravels their roles in flowering. Front. Plant Sci. 8. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00384

Ripoll, J. J., Roeder, A. H. K., Ditta, G. S., Yanofsky, M. F. (2011). A novel role for the floral homeotic gene APETALA2 during Arabidopsis fruit development. Development. 138, 5167–5176. doi: 10.1242/dev.073031

Roberts, J. A., Elliott, K. A., Gonzalez-Carranza, Z. H. (2002). Abscission, dehiscence, and other cell separation processes. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 53, 131–158. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.53.092701.180236

Roeder, A. H. K., Ferrándiz, C., Yanofsky, M. F. (2003). The role of the REPLUMLESS homeodomain protein in patterning the Arabidopsis fruit. Curr. Biol. 13, 1630–1635. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.08.027

Rounsley, S. D., Ditta, G. S., Yanofsky, M. F. (1995). Diverse roles for MADS box genes in Arabidopsis development. Plant Cell. 7, 1259–1269. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.8.1259

Schilling, S., Pan, S., Kennedy, A., Melzer, R. (2018). MADS-box genes and crop domestication: the jack of all traits. J. Exp. Bot. 69, 1447–1469. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erx479

Shu, Y., Yu, D., Wang, D., Guo, D., Guo, C. (2013). Genome-wide survey and expression analysis of the MADS-box gene family in soybean. Mol. Biol. Rep. 40, 3901–3911. doi: 10.1007/s11033-012-2438-6

Simonini, S., Bencivenga, S., Trick, M., Østergaard, L. (2017). Auxin-induced modulation of ETTIN activity orchestrates gene expression in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 29, 1864–1882. doi: 10.1105/tpc.17.00389

Vivian-Smith, A., Luo, M., Chaudhury, A., Koltunow, A. (2001). Fruit development is actively restricted in the absence of fertilization in Arabidopsis. Development. 128, 2321–2331. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.12.2321

Vrebalov, J., Pan, I. L., Arroyo, A. J. M., McQuinn, R., Chung, M., Poole, M., et al. (2009). Fleshy fruit expansion and ripening are regulated by the tomato SHATTERPROOF gene TAGL1. Plant Cell. 21, 3041–3062. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.066936

Willems, E., Leyns, L., Vandesompele, J. (2008). Standardization of real-time PCR gene expression data from independent biological replicates. Anal. Biochem. 379, 127–129. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2008.04.036

Wu, Y., Ke, Y., Wen, J., Guo, P., Ran, F., Wang, M., et al. (2018). Evolution and expression analyses of the MADS-box gene family in Brassica napus. PloS One 13, e0200762. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0200762

Xu, W., Tao, J., Chen, M., Dreni, L., Luo, Z., Hu, Y., et al. (2017). Interactions between FLORAL ORGAN NUMBER4 and floral homeotic genes in regulating rice flower development. J. Exp. Bot. 68, 483–498. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw459

Yanofsky, M. F., Ma, H., Bowman, J. L., Drews, G. N., Feldmann, K. A., Meyerowitz, E. M. (1990). The protein encoded by the Arabidopsis homeotic gene agamous resembles transcription factors. Nature. 346, 35–39. doi: 10.1038/346035a0

Zaman, Q. U., Wen, C., Yuqin, S., Mengyu, H., Desheng, M., Jacqueline, B., et al. (2021). Characterization of SHATTERPROOF homoeologs and CRISPR-cas9-mediated genome editing enhances pod-shattering resistance in Brassica napus L. CRISPR J. 4, 360–370. doi: 10.1089/crispr.2020.0129

Zhao, L., Lü, Y., Chen, W., Yao, J., Li, Y., Li, Q., et al. (2020). Genome-wide identification and analyses of the AHL gene family in cotton (Gossypium). BMC Genomics 21, 69. doi: 10.1186/s12864-019-6406-6

Zhong, R., Lee, C., Ye, Z. (2010). Evolutionary conservation of the transcriptional network regulating secondary cell wall biosynthesis. Trends Plant Sci. 15, 625–632. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.08.007

Keywords: Gossypium hirsutum, cotton boll cracking, GhSHP1, virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS), paraffin section

Citation: Xu W, Ma Q, Ju J, Zhang X, Yuan W, Hai H, Wang C, Wang G and Su J (2025) Silencing of GhSHP1 hindered flowering and boll cracking in upland cotton. Front. Plant Sci. 16:1558293. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2025.1558293

Received: 10 January 2025; Accepted: 08 February 2025;

Published: 25 February 2025.

Edited by:

Qian-Hao Zhu, Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), AustraliaReviewed by:

Wei Chen, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CAAS), ChinaCopyright © 2025 Xu, Ma, Ju, Zhang, Yuan, Hai, Wang, Wang and Su. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Caixiang Wang, d2FuZ2NhaXhAZ3NhdS5lZHUuY24=; Gang Wang, d2c1NzkxQDE2My5jb20=; Junji Su, c3VqakBnc2F1LmVkdS5jbg==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.