94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Plant Sci., 12 February 2025

Sec. Plant Abiotic Stress

Volume 16 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2025.1557412

Leaf nitrogen allocation plays a crucial role in determining both photosynthetic function and structural development of plants. However, the effects of drought, salt stress, and their combination on leaf nitrogen allocation, and how these affect mesophyll conductance (gm) and photosynthesis, remain poorly understood. In this study, we first investigated variations in photosynthetic characteristics and leaf nitrogen allocation, and analyzed the relationship between gm and leaf nitrogen allocation ratios in Ginkgo biloba under drought, salt and combined drought-salt stress. The results showed that all stress treatments significantly reduced the photosynthesis in G. biloba, with the combined drought-salt stress having the most significant inhibitory effect on the plant’s physiological characteristics. Under combined drought-salt stress, the limitation of photosynthesis due to gm (MCL) was significantly greater than under individual drought or salt stress. In contrast, the limitation due to stomatal conductance (SL) was similar to that observed under drought but higher than under salt stress. No significant differences in biochemical limitations (BL) were found across all stress treatments. Further research suggests that the increase in MCL under combined drought-stress treatment may be linked to a greater allocation of leaf nitrogen to non-photosynthetic apparatus (e.g., cell structure) and a smaller allocation to photosynthetic enzymes (i.e., ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase, Rubisco). This is supported by the positive correlation between gm and the proportion of nitrogen allocated to the carboxylation system (Pr), as well as the negative correlation with the non-photosynthetic nitrogen ratio (Pnp). These findings help to advance our understanding of the mechanisms of photosynthesis and plant adaptability under combined drought-salt stress.

Drought and salt stress are major abiotic factors limiting plant growth (Wang et al., 2003). With global climate change, the impact of these stresses is becoming increasingly severe in arid and semi-arid regions (Hussain et al., 2019). Plant photosynthesis is a physiological process highly sensitive to drought and salt stress (Chaves et al., 2009; Alam et al., 2021). Therefore, understanding the limiting factors and regulatory mechanisms of photosynthesis under drought and salt stress is crucial for mitigating their impact on agricultural and forestry productivity (Chaves et al., 2011).

Drought stress limits photosynthesis by restricting CO2 diffusion from the atmosphere to the carboxylation sites within chloroplasts (Chaves et al., 2002; Flexas et al., 2002). Stomatal closure is the first response to drought (Nadal and Flexas, 2018), typically accompanied by a reduction in stomatal conductance (gs). Meanwhile, mesophyll conductance (gm) is significantly reduced due to increased cell wall thickness (Tcw) and the inhibition of aquaporins (AQPs) and carbonic anhydrase (CA) activity (Miyazawa and Terashima, 2001; Terashima et al., 2005). Similar to drought stress, salt stress reduces gm by altering osmotic pressure and causing ion toxicity, which leads to leaf dehydration and subsequent changes in leaf anatomical structure (Tosens et al., 2012; Zait et al., 2019). Studies have shown that salt stress increases Tcw and the distance between chloroplasts and the cell wall, while reducing chloroplast density and the chloroplast surface area exposed to intercellular air space (Sc/S), thereby leading to a decrease in gm (Tosens et al., 2012; Scoffoni and Sack, 2017; Oi et al., 2020; Melo et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2021). Flexas et al. (2004) concluded that salt and drought stress primarily impact CO2 diffusion in the leaves by reducing gs and gm, rather than affecting the biochemical capacity to assimilate CO2, at mild to moderately severe stress levels. Although the combined effects of drought and salt stress are widely recognized as a major limiting factor, research on this topic remains relatively scarce (Stavridou et al., 2019). Previous studies have shown that drought can exacerbate the negative impacts of salt stress by interfering with photosynthesis and nutrient absorption, thereby further inhibiting plant growth (Alvarez and Sánchez-Blanco, 2015; Alam et al., 2021). However, the physiological responses of leaves under combined drought-salt stress and their impact on plant photosynthetic capacity have not been thoroughly investigated.

Nitrogen is an essential nutrient for plant growth and a key factor in determining photosynthesis. Plants allocate a significant portion of leaf nitrogen to the key photosynthetic enzyme (i.e., ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase - Rubisco), creating a strong link between nitrogen and photosynthetic function (Takashima et al., 2004; Damour et al., 2008; Zhong et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2022). However, leaf nitrogen is not only utilized for photosynthesis apparatus, but is also allocated to non-photosynthetic apparatus to regulate physiological traits such as Tcw (Onoda et al., 2017). Numerous studies have demonstrated that nitrogen content per area (Na) significantly influences the gm by altering the expression of AQPs (Xiong and Flexas, 2018), the permeability of biological membranes (Flexas et al., 2006), the Tcw, and the chloroplast surface area exposed to intercellular air space (Sc/S) (Evans et al., 2009; Terashima et al., 2011; Tholen and Zhu, 2011). However, the effects of leaf nitrogen allocation on changes in gm under combined drought-salt stress remain insufficiently understood.

Ginkgo biloba, a renowned “living fossil” and valuable relict species, is widely distributed across the globe and is known for its remarkable ecological resilience and adaptability to diverse environmental conditions (Zhao et al., 2010, 2019). Meanwhile, Wang et al. (2020) have demonstrated that G. biloba contains a wealth of resistance genes, which play a critical role in coping with abiotic stresses such as drought and salt. Therefore, investigating the physiological responses of G. biloba to stressful environments can provide new perspectives and insights for forestry breeding and the study of plant adaptation mechanisms. While research has been conducted on plant responses to environmental stresses, how leaf nitrogen allocation affects gm and, consequently, photosynthesis remains unclear under combined drought-salt stress. This study uses G. biloba as experimental material and aims to 1) investigate the variations in photosynthetic traits and leaf nitrogen allocation in G. biloba under combined drought-salt stress; 2) explore whether leaf nitrogen allocation affects gm under combined drought-salt stress.

The experiment was conducted from June to August 2024 at the Xiashu Forestry Station of Nanjing Forestry University in Jurong City, Jiangsu Province (119°12′E, 32°07′N). This site is characterized by a subtropical monsoon climate, with abundant rainfall and ample sunlight. The average monthly environmental temperature was 28°C, and the average monthly precipitation was 139.4 mm. The 3-year-old G. biloba seedlings with relatively uniform plant heights were planted in 12 L flowerpots, with one plant per pot. The average height of the plants is approximately 1 meter, and the base diameter is about 1.2 centimeters. The nutrient soil was mixed with organic cultivation matrix (mixed fertilizer: perlite = 80%: 20%; organic matter content ≥ 35%; pH 5.5-7.0) and loess at a ratio of 4:1. G. biloba seedlings were placed in a rain-shielded greenhouse for growth, where the light level was approximately half of the natural light.

Stress treatments were applied once the sixth leaf of all plants had fully expanded. The experimental design included a control group (CK, 30% soil absolute water content - AWC + 0 mmol/L NaCl) and three treatment groups: drought treatment (D, 10% AWC + 0 mmol/L NaCl), salt treatment (S, 30% AWC + 150 mmol/L NaCl), and combined drought-salt treatment (SD, 10% AWC + 150 mmol/L NaCl). Each treatment consisted of 9-12 plants.

For the salt treatments, we began initiating the plants with NaCl solutions in early June. To avoid salt shock, NaCl concentrations of 50, 100, and 150 mmol/L were applied stepwise for three consecutive days, followed by 150 mmol/L NaCl every seven days for a total of three applications until the drought treatment began.

For the water control, all plants were initially irrigated daily to water saturation (30% AWC). To maintain a consistent AWC, all the plants were weighed and irrigated every evening. The total weight (the sum of water weight, pot weight, and dry nutrient soil weight) that needs to be maintained every day was calculated using the following equation:

The combined weight of the pot and dry nutrient soil was 3.5 kg, while the dry nutrient soil alone weighted 3.3 kg per pot. Note that we have omitted the weight of the plant seedlings here, as it is difficult to measure unless using destructive methods. For the drought and combined drought-salt treatments, irrigation was stopped once RWC reached the desired levels on the 18th day for the drought treatment and on the 25th day for the combined drought-salt treatment.

After 49 days of drought stress treatments, measurements were taken from the sixth mature leaf from the top of each plant (Figure 1A; Supplementary Figure S2).

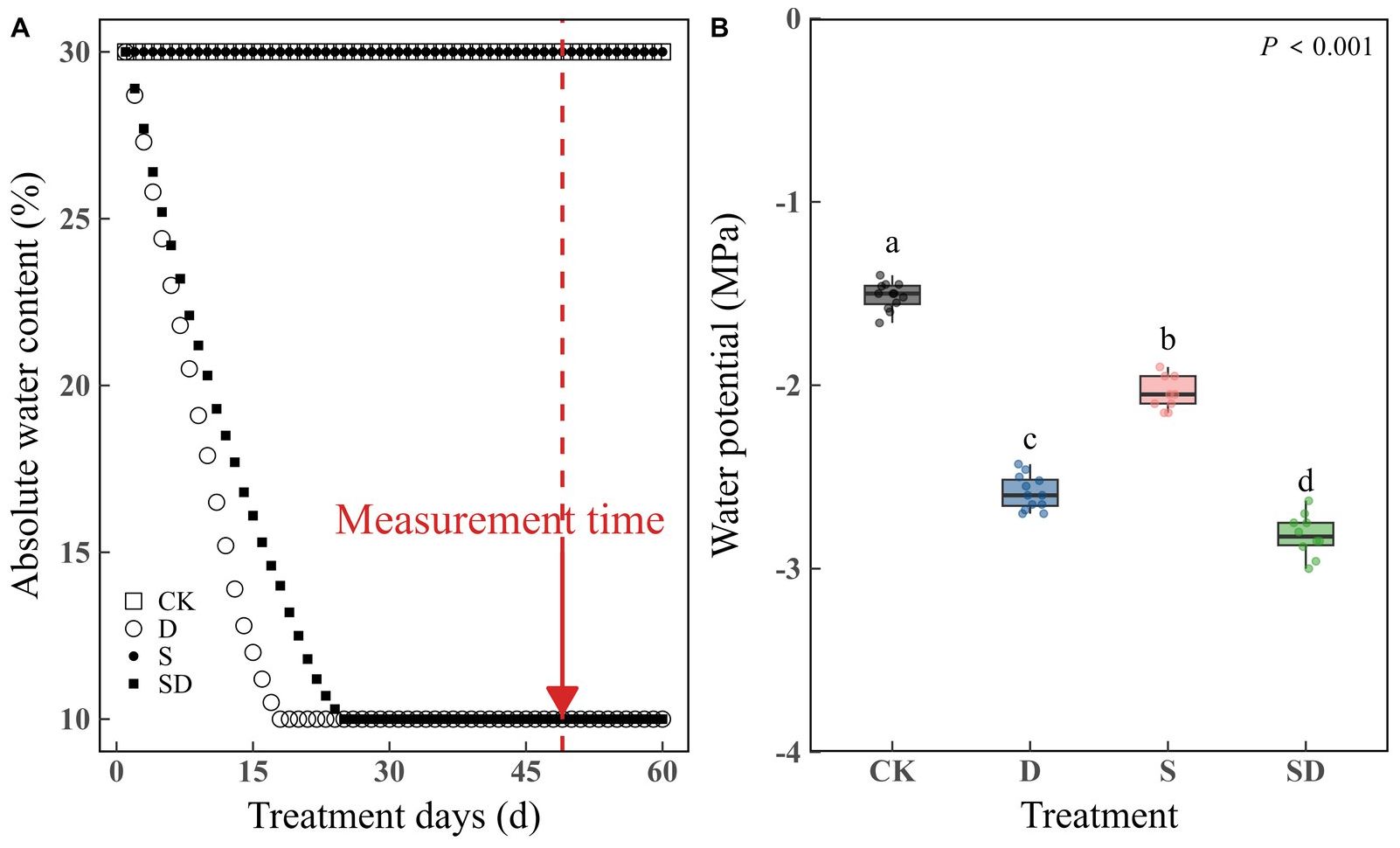

Figure 1. Measurement of changes in absolute soil water content and leaf water potential (Ψw) for different stress treatments. (A) Differences in absolute soil water content over time for different stress treatments. (B) Measurement of changes in Ψw of different stress treatments. According to Duncan’s multiple range test, different letters indicate significant differences between stress treatments (P < 0.001). Each stress treatment group contained 9 to 12 samples (9≤n ≤ 12).

Leaf gas exchange and chlorophyll fluorescence parameters were collected simultaneously using a Li-6800 (LI-COR, USA) equipped with a multiphase flash fluorescence leaf chamber (LI-COR, 6800-01A, 6 cm²) during sunny days. The parameters of the leaf chamber were set as follows: red/blue light ratio of 9:1, leaf temperature maintained at 30°C, relative humidity at 50%, the vapor pressure deficit (VPD) between 2.10 and 2.3 kPa, and an air flow rate set to 500 μmol s-1. Initially, photosynthesis was induced using a photosynthetically active radiation intensity (PPFD) of 1500 μmol m-2 s-1 and the ambient CO2 concentration (Ca) of 400 μmol mol-1. After reaching a steady state in approximately 20 minutes, the CO2 and light response curves were measured using an automatically monitored program. The CO2 response curve was measured at 13 Ca values, where Ca was stepped down from 400 μmol mol-1 to 50 μmol mol-1, then increased back to 400 μmol mol-1, and stepped up to 1500 μmol mol-1, with each step lasting 120-240 seconds. Light response curves were collected on the same leaves, with PPFD gradually decreased from 1800 μmol m-2 s-1 to 0 μmol m-2 s-1 over 12 different PPFD levels. Each step lasted 120-180 seconds, and Ca was held constant at 400 μmol mol-1. The gas exchange parameters (i.e., An, intercellular CO2 concentration-Ci, stomatal conductance to water vapor-gsw) and chlorophyll fluorescence parameters [i.e., steady-state chlorophyll fluorescence (Fs) and maximum chlorophyll fluorescence (Fm’)] under light conditions were obtained from the CO2 and light response curves. Note that stomatal conductance to CO2 (gs) was used in this study, and it can be calculated from gsw (gs = gsw/1.6). Additionally, the dark respiration rate (Rn), the mimimum and maxmium chlorophyll fluorescence (Fo and Fm) were measured on the same leaves under fully dark-adapted conditions. The maximum quantum yield of photosystem II (Fv/Fm) was calculated with Fo and Fm (Fv/Fm = ). The measured light response curves were fit using the “photosynthesis” package in R to extract the net photosynthesis under saturating light (Asat).

The value of gm was estimated using the variable J approach based on Harley et al. (1992), as follows:

where Rd is half of the measured dark respiration rate (Rn, Rd = Rn/2) (Villar et al., 1995; Piel et al., 2002; Niinemets et al., 2005), and Γ * represents the CO2 compensation point without mitochondrial respiration. According to Bernacchi et al. (2002), the value of Γ * at 30°C was determined and used in the calculation of gm:

where TL is leaf temperature (°C).

The actual photochemical efficiency of PS II (ΦPSII) was calculated according to Genty et al. (1989):

The electron transfer rate (Ja) was determined as:

where α represents the leaf absorptance, β indicates the partitioning of absorbed quanta between PS I and II. As reported by Wang et al. (2018a), no significant difference was observed in the α × β values of Oryza sativa leaves between the control group and the salt stress treatment group. Therefore, consistent values of α = 0.84 and β = 0.5 were applied to all treatments (Li et al., 2021).

The gm, maximum carboxylate rate (Vcmax), and maximum electron rate (Jmax) were estimated according to the An-Cc curve fitting method proposed by Sharkey (2016). The variable J and the An-Cc curve-fitting methods were applied to the same dataset for estimating gm. The results from the two methods were highly consistent (R2 = 0.94, P < 0.001; Supplementary Figure S1). Therefore, only the gm values estimated by the Harley et al. (1992) method are discussed in this study.

According to Grassi and Magnani (2005), we analyzed the quantitative limitations of An by stomatal conductance (SL), mesophyll conductance (MCL) and biochemistry (BL) in G. biloba. The relative change of light saturation assimilation can be expressed by the parallel relative changes of gs (gsw/1.6), gm and Vcmax, and the calculation formula is as follows:

where gtot represents the total conductance of CO2 from leaf surfaces to sites of carboxylation (1/gtot = 1/gs + 1/gm); ls, lm and lb are the corresponding relative limitation (ls+lm+lb=1); ∂An/∂Cc represents the slope of the An-Cc curve within the range of 50-100 μmol mol -1 (Tomás et al., 2013).

where , and are the reference values of stomatal, mesophyll conductance and maximum carboxylation rate, respectively, and were set to the maximum values observed in the control group (Flexas et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2018b).

The leaves were placed in a 95% ethanol solution at room temperature in the dark for 48 hours until the leaves turned white. The absorbance of the extract was measured at 665 nm, 649 nm, and 470 nm using a 722 spectrophotometer. The chlorophyll content per unit area was calculated according to Arnon’s modified formula (Zhi and Xia, 2023).

A perforator with an inner diameter of 16 mm was used to obtain 10 leaf discs while avoiding the leaf veins in the leaf blade. The discs were placed in a kraft paper bag, dried at 65°C for 72 hours, and then weighed using an electronic balance. Leaf dry mass per area (LMA) was calculated by dividing leaf dry mass by leaf area, where the leaf area refers to the total area of these 10 discs, and the leaf dry mass represents the total dry mass of the same 10 discs after drying.

The leaves were removed from the petiole and dried in an oven at 65°C until constant weight, subsequently ground and passed through a 100-mesh screen. 5 mg of leaf powder was weighed for each sample and its total nitrogen content was determined using an elemental analyzer (Eurovector EA3100, Italy) following standard operating procedures.

Leaf water potential was measured before dawn using a Model 615 Pressure Chamber Instrument (PMS, USA). Mature leaves from the same leaf position on each plant were selected, and placed in the pressure chamber and pressurization was applied through a compressed nitrogen cylinder until the first drop of sap exudation was observed at the petiole outside the pressure chamber, and then the data were recorded.

Leaf nitrogen allocation consists of the photosynthetic nitrogen ratio (Pp) and the non-photosynthetic nitrogen ratio (Pnp), with Pp comprising three main components: the proportion of nitrogen allocation to light-harvesting system (PL), bioenergetics (Pb) and carboxylation system (Pr). PL (nitrogen content in light-harvesting chlorophyll-protein complex), Pb (total nitrogen content of cytochrome f, ferredoxin NADP reductase, and coupling factors), and Pr (nitrogen content of Rubisco) are calculated using the estimation method proposed by Niinemets and Tenhunen (1997) as follows:

where Chlt represents total leaf chlorophyll content, Nm is nitrogen content per mass. CB refers the chlorophyll binding ratio in the photosystem, which governs the efficiency of nitrogen input into the thylakoid to participate in light harvesting and was estimated as the weighted average of chlorophyll binding to PSI, PSII and LHCII. Jmc denotes the maximum electron transfer per unit of cyt f (182.3 mol electron (mol cyt f)-1), Vcr is the specific activity of Rubisco (32.76 μmol CO2 (g Rubisco)-1s-1), 6.25 (g Rubisco (g nitrogen in Rubisco)-1) is the conversion factor from nitrogen content to protein content, 8.06 (μmol cyt f (g nitrogen in bioenergetics)-1) is the conversion factor between cyt f and nitrogen in bioenergetics.

Microsoft Excel 2019 and R software (version 4.2.2, ggplot2) were used for data collection, analysis, and drawing. One-way ANOVA was performed using the R package “agricolae” to compare mean differences between treatments, with Duncan’s test applied at a significance level of P < 0.05. Linear regression models for physiological traits across different treatments were fitted using the R package “ggpmisc”.

The changes in ARC with time under different treatments are shown in Figure 1A. The ARC was maintained at 30% in the control and salt stress treatments. Under both drought and combined drought-salt stress, we maintained the soil absolute water content at 10%. However, plants under drought stress reached the expected level more quickly than those under combined drought-salt stress. Leaf water potential (Ψw) reflected the water status under each treatment (Figure 1B). As expected, Ψw was highest in the control, lowest under combined drought-salt stress, and higher in the salt stress treatment compared to drought stress. The change trends in Fv/Fm closely align with those of Ψw, suggesting that our water treatment effectively achieved the desired effects (Supplementary Figure S3; Figure 1B).

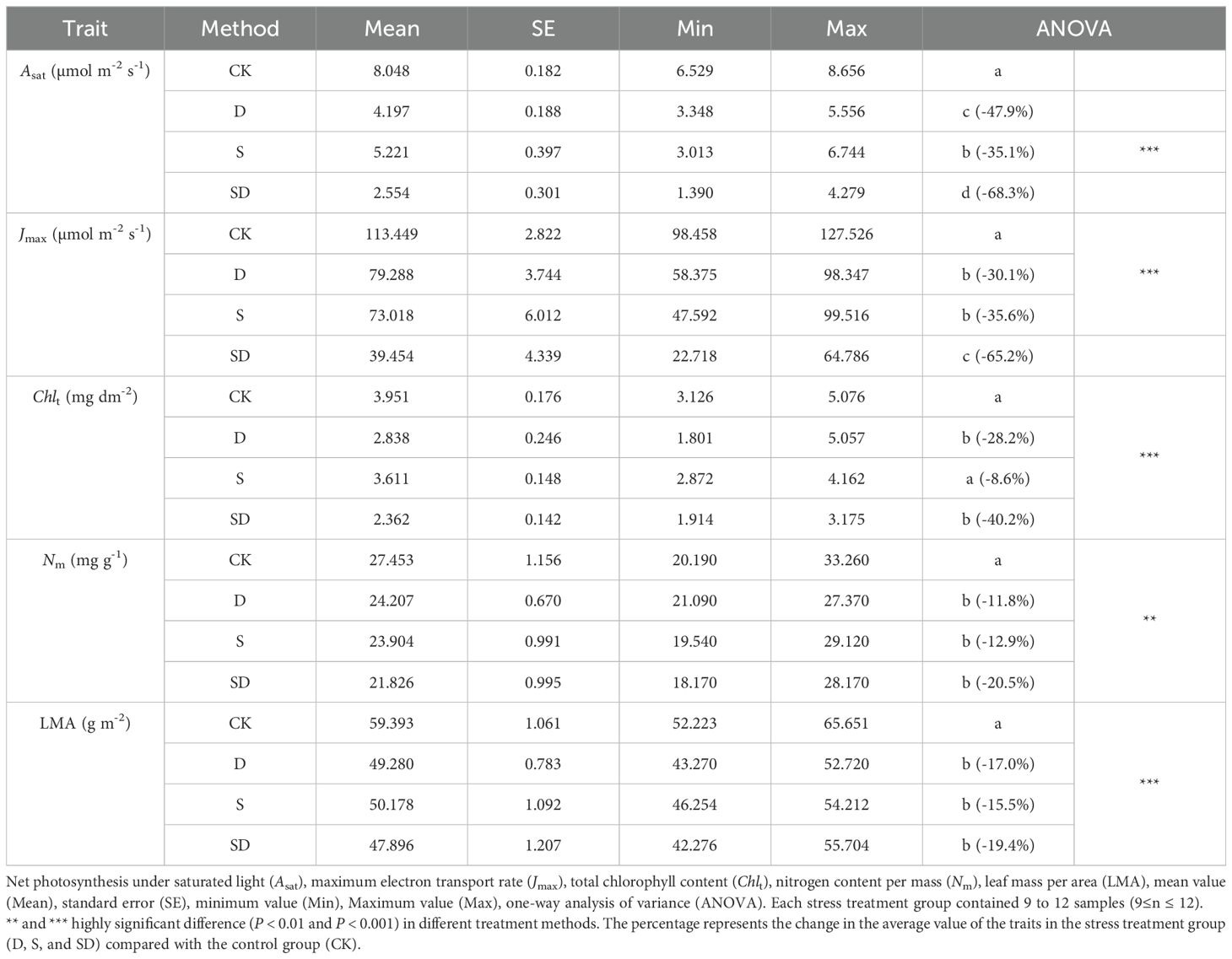

Most physiological traits showed significant differences among treatments (Table 1; Supplementary Table S1; Figure 2). An and gs were significantly reduced in all stress treatments compared to control, with decreases of 54.9% and 64.0% under drought stress, 39.1% and 40.5% under salt stress, and 80.5% and 81.7% under combined drought-salt stress (Table 1; Figures 2A, E). For Vcmax, Jmax, and gm, no significant differences were observed between drought and salt stress treatments. Compared to the control, these values decreased by 47.0%, 30.1% and 49.2% under drought stress, 43.1%, 35.6% and 41.6% under salt stress, and 78.6%, 65.2% and 83.3% under combined drought-salt stress (Table 1; Supplementary Table S1; Figures 2B, D). Notably, since both Vcmax and Jmax represent photosynthetic capacity and are linearly correlated (Walker et al., 2014), we primarily focused on the analysis of Vcmax in this study. Both drought and combined drought-salt stress significantly reduced Chlt, with no significant effect under salt stress (Table 1). Nm and LMA were significantly lower in all stress treatments compared to the control, but there were no differences among the stress treatments (Table 1). Compared to the control, Asat decreased significantly in drought, salt and combined drought-salt stress by 47.9%, 35.1% and 68.3%, respectively (Figure 2F; Table 1).

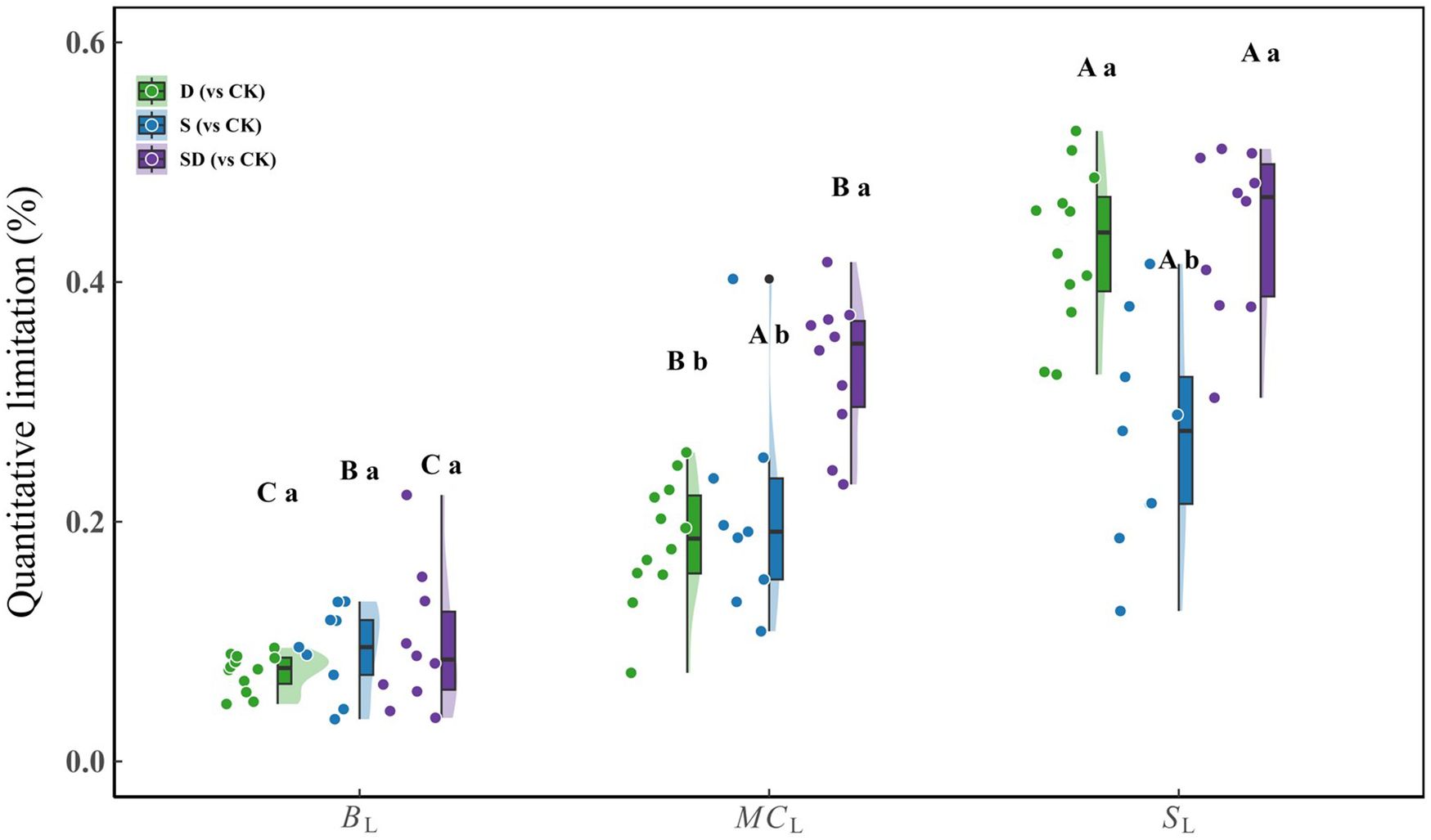

Table 1. Changes in physiological traits of G. biloba under drought, salt stress and combined drought-salt stress treatments.

Figure 2. Response of photosynthetic characteristics of G. biloba to different stress treatments. (A) Net photosynthesis (An); (B) Mesophyll conductance (gm); (C) CO2 response curve; (D) Maximum carboxylate rate (Vcmax); (E) Stomatal conductance (gs); (F) Light response curve. According to Duncan’s multiple range test, different letters indicate significant differences between stress treatments (P < 0.001). Each stress treatment group contained 9 to 12 samples (9≤n ≤ 12).

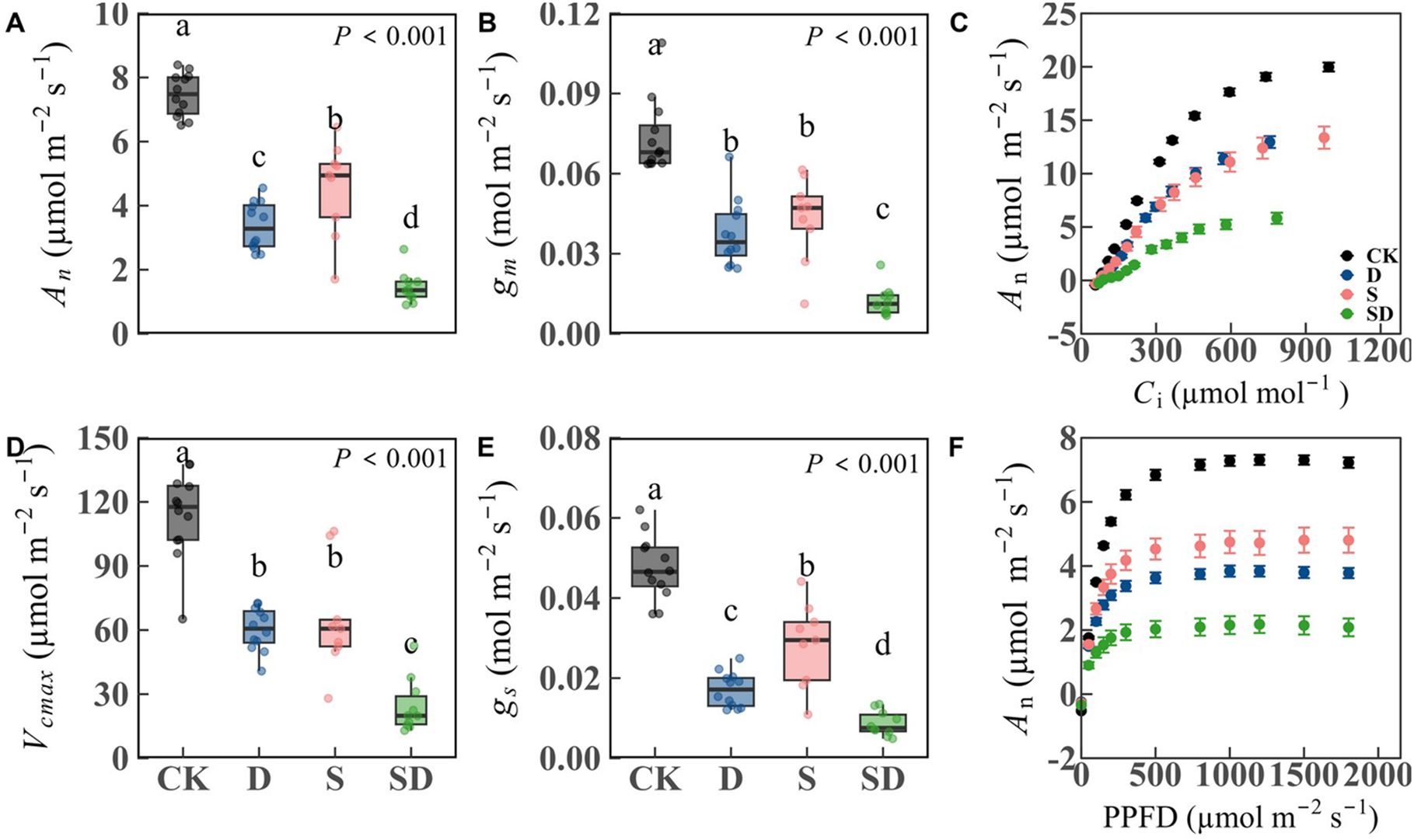

Quantitative limitation analysis of photosynthesis under different stress conditions revealed significant differences in the weights of each limiting factor (Figure 3). There were significant differences among BL, MCL, and SL under stress treatments, with BL being the lowest, MCL intermediate, and SL the highest. Under combined drought-salt stress, MCL was significantly greater than under individual drought or salt stress. In contrast, SL was similar to that observed under drought but higher than under salt stress. No significant differences in BL were found across all stress treatments.

Figure 3. Quantitative limitation analysis of photosynthesis in G. biloba leaves under drought, salt, and combined drought-salt stress treatments (compared with the control group). Duncan’s test was used for multiple comparison analysis of statistical significance, with capital letters (A, B, C) representing significant differences among the three limiting factors (SL, MCL, BL) within the same treatment group; lowercase letters (a, b, c) indicate significant differences for the same limiting factor across different treatment groups (D, S, SD). Each stress treatment group contained 9 to 12 samples (9≤n ≤ 12).

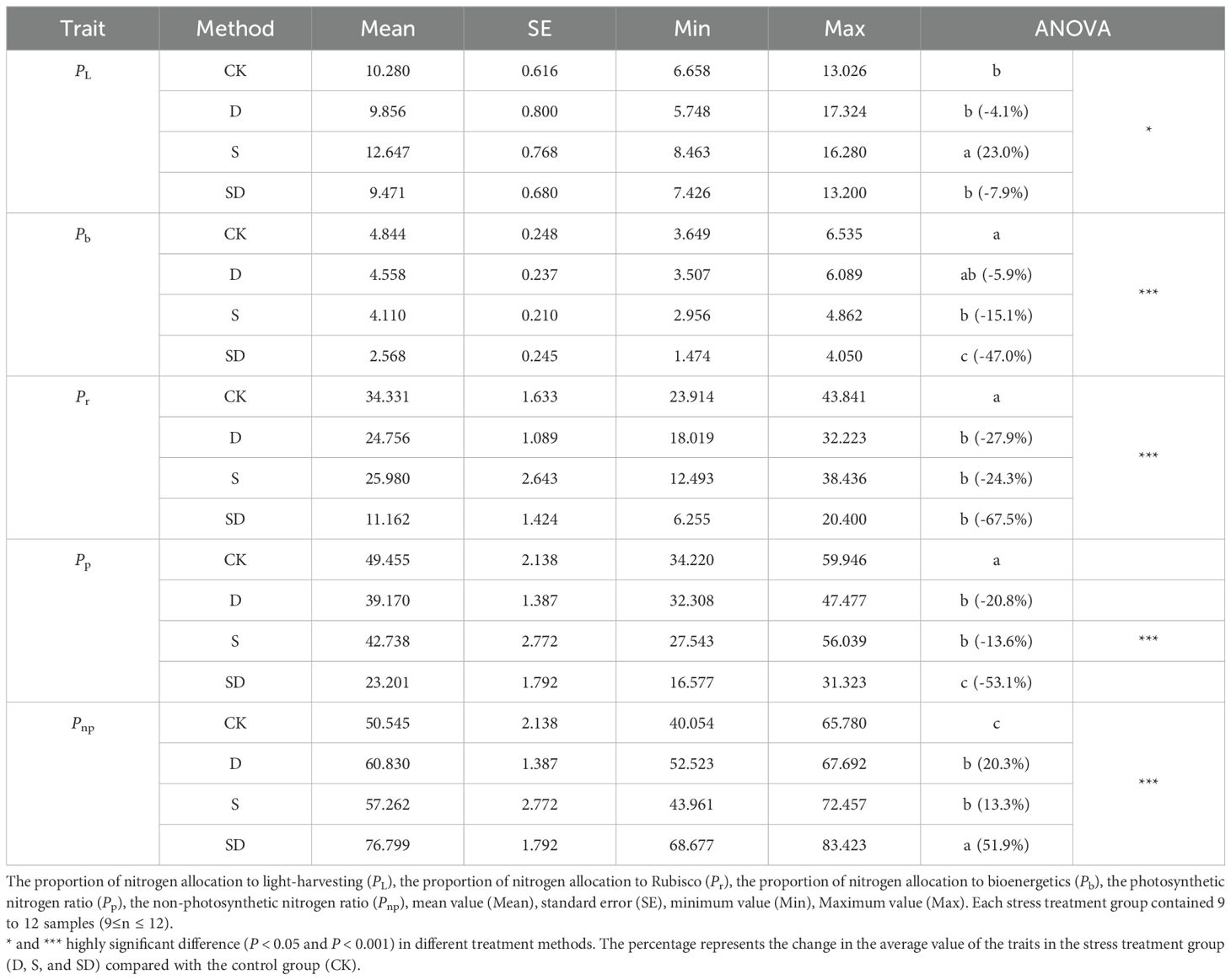

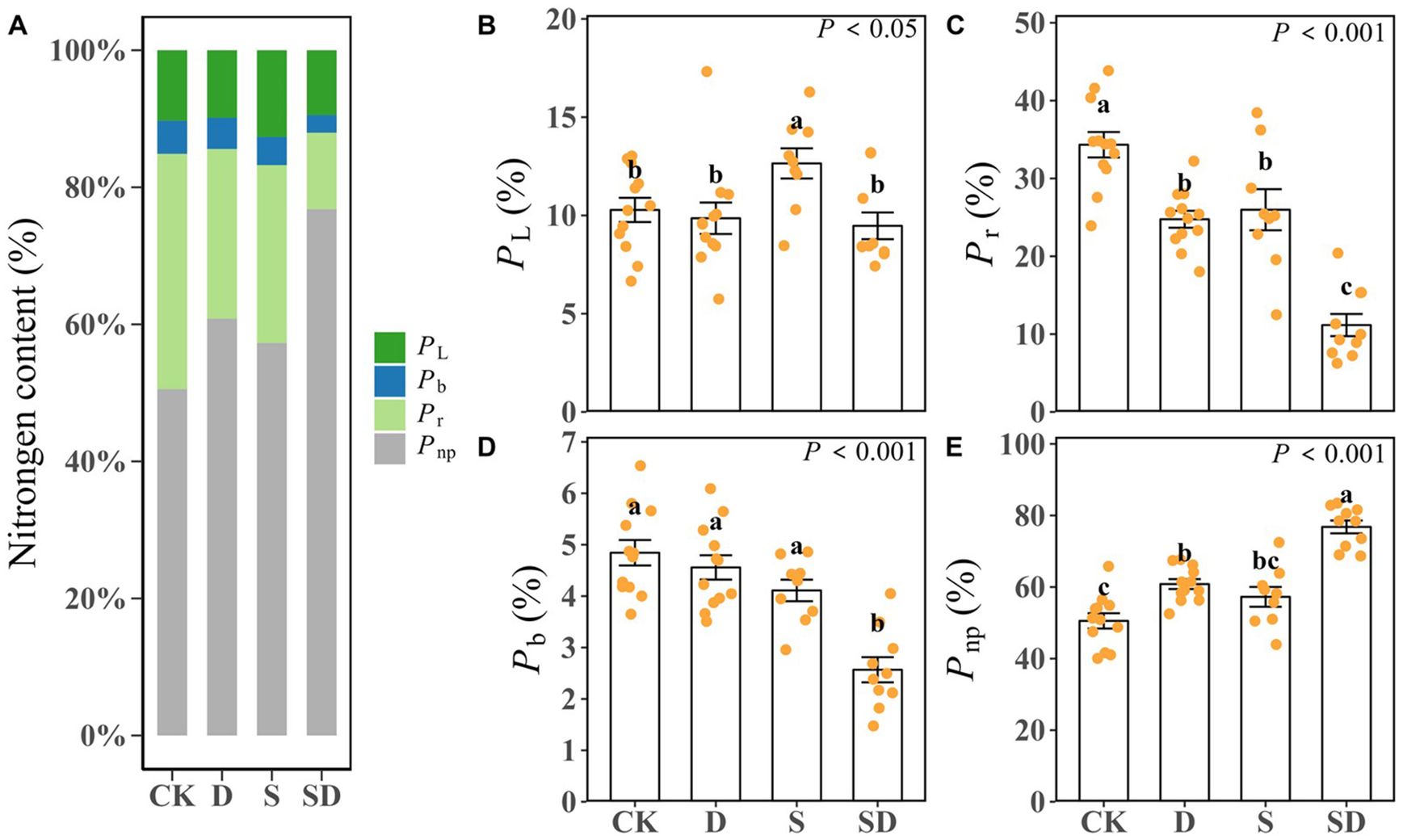

Leaf nitrogen allocation ratios showed significant differences across the different treatments (Table 2; Figure 4). In comparison to the control, PL was significantly increased by 23% under salt stress, yet it decreased by 4.1% and 7.9% under drought and combined drought-salt stress respectively (Table 2; Figure 4B). Drought, salt, and combined drought-salt stress led to significant reductions in Pb by 5.9%, 15.1%, and 47.0%, and there was no significant difference between drought and salt stress (Table 2; Figure 4D). Pr was significantly decreased under drought, salt and combined drought-salt stress by 27.9%, 24.3% and 67.5% respectively (Table 2; Figure 4C). In contrast, Pnp was increased by 20.3%, 13.3% and 51.9% under drought, salt and combined drought-salt stress, respectively (Table 2; Figure 4E). Overall, the proportion of Pnp was similar to that of Pp under all stress treatments. Pr accounted for the largest proportion of Pp, followed by PL, and Pb had the smallest proportion (Table 2; Figure 4).

Table 2. Changes in nitrogen distribution ratio in G. biloba leaves under different stress treatments.

Figure 4. (A) Stacked histograms showing differences in leaf nitrogen allocation among different stress treatments. The proportion of nitrogen allocation to light-harvesting (PL), the proportion of nitrogen allocation to Rubisco (Pr), the proportion of nitrogen allocation to bioenergetics (Pb), the non-photosynthetic nitrogen ratio (Pnp). The (B–E) bar graph showed the differences of PL, Pr, Pb and Pnp among different stress treatments. Each stress treatment group contained 9 to 12 samples (9≤n ≤ 12). According to Duncan’s multiple range test, different letters indicate significant differences between stress treatments (P < 0.05 or P < 0.001).

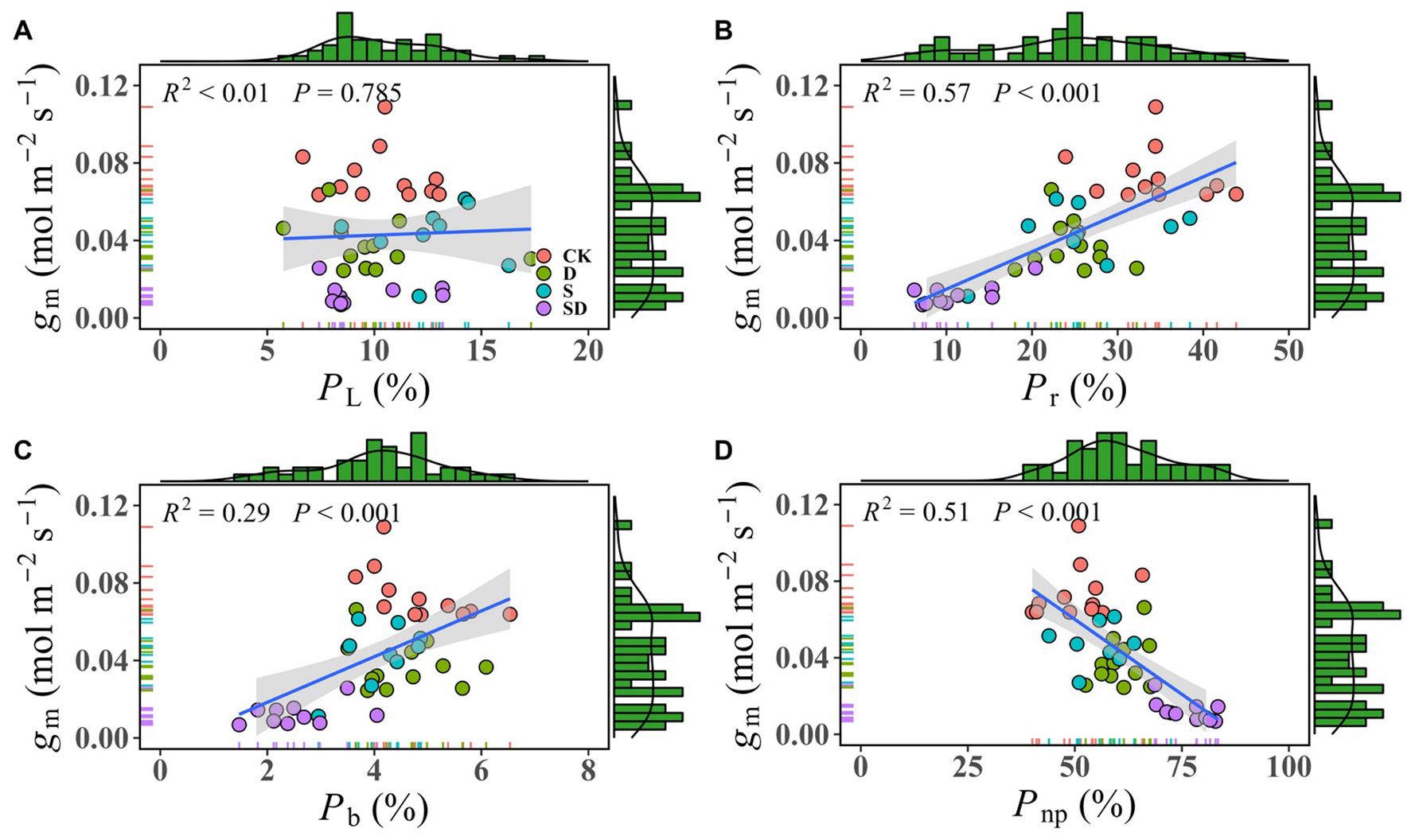

We analyzed the correlation between gm and leaf nitrogen distribution ratio by pooling all data together (Figure 5). The results showed that there was no significant relationship between gm and with PL (R² < 0.01, P = 0.785; Figure 5A). The lack of correlation between gm and PL likely arises because PL is primarily influenced by Chlt, while gm is more sensitive to leaf anatomical structure and biochemical factors. This is evidenced by the inconsistent trends in changes observed for Chlt (Table 1) and gm (Figure 2) under different treatments. gm exhibited a close positive correlation with both Pr (R² = 0.57, P < 0.001; Figure 5B) and Pb (R² = 0.29, P < 0.001; Figure 5C), while showed a negative correlation with Pnp (R² = 0.51, P < 0.001; Figure 5D).

Figure 5. The linear correlation between gm and leaf nitrogen allocation ratio. (A) The correlation between gm and the proportion of nitrogen allocated to light-harvesting components (PL); (B) The correlation between gm and the proportion of nitrogen allocated to Rubisco (Pr); (C) The correlation between gm and the proportion of nitrogen allocated to bioenergetics (Pb); (D) The correlation between gm and the non-photosynthetic nitrogen allocation ratio (Pnp). The marginal histograms show the frequency distribution of each variable (gm, PL, Pb, PL, and Pnp). Each data point represents individual samples from one of four stress treatment groups: control (CK), drought (D), salt (S), and combined drought-salt (SD) stress, and each stress treatment contained 9 to 12 samples (9≤n ≤ 12).

To investigate the role of gm in limiting photosynthesis and its relationship with nitrogen allocation under combined drought-salt stress in G. biloba, we measured gas exchange and nitrogen allocation under drought, salt, and combined drought-salt treatments. The results of this study showed that gm is considered a key factor limiting photosynthesis, especially under combined drought-salt stress. In addition, under these stress conditions, the allocation of nitrogen to photosynthetic components and non-photosynthetic apparatus plays a key regulatory role in gm, as evidenced by the significant correlations between Pr and Pnp and gm.

Compared to the control, all three treatments resulted in significant reductions in gs, gm, and Vcmax, leading to a substantial decrease in photosynthesis (Figure 2). This reduction can be attributed to stomatal closure, which limits CO2 entry, and impaired mesophyll cell structure, which increases diffusion resistance. Additionally, the decrease in Vcmax is linked to the inhibition of Rubisco activity and reduced nitrogen allocation to photosynthetic components. These findings are consistent with previous studies (Grassi and Magnani, 2005; Flexas et al., 2009; Limousin et al., 2010; Flexas, 2016; Zait et al., 2019). Further analysis revealed that the degree of decline in gs, gm, and Vcmax varied across the stress treatments. For instance, under drought conditions, gs was significantly lower than that under salt stress, while no significant differences were observed in gm and Vcmax. This discrepancy may be attributed to the higher leaf water potential under salt stress compared to drought stress, suggesting that water potential has a more pronounced effect on stomata than on mesophyll and biochemical processes. Previous studies have also shown that stomata are the primary responders to water stress (Cornic, 2000; Chaves et al., 2002; Flexas and Medrano, 2002). When comparing single stress treatments to the combined drought-salt stress, the latter resulted in the most significant reductions in gs, gm, and Vcmax, leading to the lowest photosynthetic rate. From the quantitative limitation analysis (Figure 3), we found that the combined drought-salt stress significantly increased MCL relative to the individual drought or salt stress, while the SL under combined drought-salt stress was similar to that observed under drought but higher than under salt stress. This suggests that compared to a single stress, MCL is the dominant factor causing the significant decrease in photosynthesis under combined drought-salt stress. Under such conditions, merely regulating gs is inadequate to alleviate the stress, prompting plants to adapt by modifying leaf structure. These structural changes can notably affect gm, leading to a considerable decrease in photosynthesis. As noted by Galmés et al. (2007), MCL becomes a key limiting factor for photosynthesis under extreme stress conditions.

Leaf nitrogen allocation is closely related to the plant photosynthetic function (Takashima et al., 2004; Evans and Clarke, 2019), with a trade-off existing between allocation to anatomical structures and photosynthetic processes (Onoda et al., 2017). In this study, we investigated whether the substantial decrease in gm under combined drought-salt stress is associated with changes in nitrogen allocation. The results showed that, under both single drought and salt stress, the proportion of nitrogen allocation to bioenergetics (i.e., Pb) and light-harvesting (i.e., PL) remained largely unchanged compared to the control, except for an increase in PL under salt stress. However, the proportion of nitrogen allocation to Rubisco (i.e., Pr) significantly decreased, leading to a reduced energy demand. As a result, to maintain a balance between energy production and consumption, excess energy produced during the light reaction phase might be dissipated via cyclic electron flow (Yamori and Shikanai, 2016; Pinnola and Bassi, 2018). This is supported by studies showing a significant increase in cyclic electron flow under drought and salt stress (Zivcak et al., 2013; Neto et al., 2017; He et al., 2021). Meanwhile, the reduced nitrogen allocation to Rubisco also resulted in a decreased need for CO2, which was reflected in lower gs and gm. In parallel, excess nitrogen was redirected towards structural components (e.g., cell wall, non-photosynthetic proteins and cell membranes) (Evans and Clarke, 2019). Previous research has confirmed a close relationship between gm and Tcw (Terashima et al., 2011; Tomás et al., 2013; Roig-Oliver et al., 2020). The increased Tcw, resulting from the redistribution of nitrogen, further contributed to the reduction in gm under drought and salt stress. Furthermore, when compared to individual stress treatments, the combined drought-salt stress led to a further significant reduction in nitrogen allocation for both energy production and Rubisco synthesis, while nitrogen allocation for non-photosynthetic functions significantly increased. This shift resulted in a further decline in the plant’s demand for CO2. The correlations between Pr, Pnp, and gm reinforce the idea that nitrogen allocation plays a crucial role in regulating gm.

Plants typically balance photosynthetic function and leaf structure construction to adapt to changes in the external environment and optimize resource utilization (Liakoura et al., 2009; Gonzalez-Paleo and Ravetta, 2018).The allocation of leaf nitrogen between photosynthetic and non-photosynthetic apparatus reflects a plant’s strategy for coordinating growth demands with environmental adaptability (Yao et al., 2018; Zhong et al., 2019). In G. biloba, the nitrogen allocation strategy may serve as a crucial adaptive mechanism for regulating resource distribution and enhancing survival, particularly under combined drought-salt stress. The increased allocation of nitrogen to the cell wall could play a key role in maintaining cellular function and structural integrity by enhancing the rigidity and stability of the cell wall (Feng et al., 2009), which in turn improves resistance to osmotic stress (Ridenour et al., 2008; Durand et al., 2011; Onoda et al., 2017).

In this study, we adopted two methods to calculate gm to improve reliability. However, we recognize that gm calculations are affected by factors like photorespiration and the stability of Ci, emphasizing the need for a more comprehensive model for estimating gm (Flexas et al., 2007; Tholen et al., 2012). Additionally, we discussed the potential impact of increased Tcw on gm, although we acknowledge the absence of direct experimental data linking changes in Tcw to gm. However, previous research has suggested that the increased Tcw are closely associated with changes in Pnp and reduced Pr (Feng et al., 2009). An increase in Tcw can limit gm by restricting CO2 movement through the leaf tissue (Evans et al., 1994, 2009; Tosens et al., 2012; Tomás et al., 2013; Onoda et al., 2017). To gain a deeper understanding of the relationship between leaf structure and nitrogen allocation in photosynthetic tissues, further research on leaf anatomical adaptations and their effects on gas exchange is needed. Such studies would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms underlying leaf nitrogen allocation and its impact on photosynthetic efficiency, particularly under stress conditions.

In summary, this study demonstrated that drought and salt stress significantly inhibited the photosynthesis in G. biloba by decreasing gs, gm, and Vcmax, with the most pronounced negative effects observed under combined drought-salt stress. gm was identified as a key factor limiting photosynthesis, especially under the combined drought-salt stress. Additionally, the allocation of nitrogen towards photosynthetic components (e.g., light-harvesting pigments, bioenergetic systems, and Rubisco) and non-photosynthetic apparatus (including cell wall, non-photosynthetic proteins and cell membranes) played a crucial regulatory role in gm under these stress conditions, as evidenced by the significant correlation between Pr and Pnp with gm.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

LL: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KZ: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. XY: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. XS: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. PD: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. YZ: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. FC: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. JH: Data curation, Investigation, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by the Key Research and Development Program of Jiangsu Province (Grant No. BE2021367), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32401559), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (Grant No. BK20240669), and the scientific research foundation for advanced talents from Nanjing Forestry University.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be constructed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2025.1557412/full#supplementary-material

Alam, H., Khattak, J. Z. K., Ksiksi, T. S., Saleem, M. H., Fahad, S., Sohail, H., et al. (2021). Negative impact of long-term exposure of salinity and drought stress on native Tetraena mandavillei L. Physiol. Plant 172, 1336–1351. doi: 10.1111/ppl.13273

Alvarez, S., Sánchez-Blanco, M. J. (2015). Comparison of individual and combined effects of salinity and deficit irrigation on physiological, nutritional and ornamental aspects of tolerance in Callistemon laevis plants. J. Plant Physiol. 185, 65–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2015.07.009

Bernacchi, C. J., Portis, A. R., Nakano, H., Von Caemmerer, S., Long, S. P. (2002). Temperature response of mesophyll conductance. Implications for the determination of Rubisco enzyme kinetics and for limitations to photosynthesis in vivo. Plant Physiol. 130, 1992–1998. doi: 10.1104/pp.008250

Chaves, M. M., Costa, J. M. F., Saibo, N. J. M. (2011). Recent advances in photosynthesis under drought and salinity. Adv. Bot. Res. 57, 49–104. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-387692-8.00003-5

Chaves, M. M., Flexas, J., Pinheiro, C. (2009). Photosynthesis under drought and salt stress: regulation mechanisms from whole plant to cell. Ann. Bot. 103, 551–560. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcn125

Chaves, M. M., Pereira, J. S., Maroco, J., Rodrigues, M. L., Ricardo, C. P., Osório, M. L., et al. (2002). How plants cope with water stress in the field. Photosynthesis and growth. Ann. Bot. 89, 907–916. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcf105

Cornic, G. (2000). Drought stress inhibits photosynthesis by decreasing stomatal aperture – not by affecting ATP synthesis. Trends Plant Sci. 5, 187–188. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(00)01625-3

Damour, G., Vandame, M., Urban, L. (2008). Long-term drought modifies the fundamental relationships between light exposure, leaf nitrogen content and photosynthetic capacity in leaves of the lychee tree (Litchi chinensis). J. Plant Physiol. 165, 1370–1378. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2007.10.014

Durand, T. C., Sergeant, K., Renaut, J., Planchon, S., Hoffmann, L., Carpin, S., et al. (2011). Poplar under drought: Comparison of leaf and cambial proteomic responses. J. Proteomics 74, 1396–1410. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2011.03.013

Evans, J. R., Caemmerer, S. V., Setchell, B. A., Hudson, G. S. (1994). The relationship between CO2 transfer conductance and leaf anatomy in transgenic tobacco with a reduced content of rubisco. Aust. J. Plant Physiol. 21, 475–495. doi: 10.1071/PP9940475

Evans, J. R., Clarke, V. C. (2019). The nitrogen cost of photosynthesis. J. Exp. Bot. 70 1, 7–15. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ery366

Evans, J. R., Kaldenhoff, R., Genty, B., Terashima, I. (2009). Resistances along the CO2 diffusion pathway inside leaves. J. Exp. Bot. 60, 2235–2248. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp117

Feng, Y. L., Lei, Y. B., Wang, R. F., Callaway, R. M., Valiente-Banuet, A., Inderjit, et al. (2009). Evolutionary tradeoffs for nitrogen allocation to photosynthesis versus cell walls in an invasive plant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 1853–1856. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808434106

Flexas, J. (2016). Genetic improvement of leaf photosynthesis and intrinsic water use efficiency in C3 plants: Why so much little success? Plant Sci. 251, 155–161. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2016.05.002

Flexas, J., Barón, M., Bota, J., Ducruet, J. M., Gallé, A., Galmés, J., et al. (2009). Photosynthesis limitations during water stress acclimation and recovery in the drought-adapted Vitis hybrid Richter-110 (V-berlandierix V-rupestris). J. Exp. Bot. 60, 2361–2377. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp069

Flexas, J., Bota, J., Escalona, J. M., Sampol, B., Medrano, H. (2002). Effects of drought on photosynthesis in grapevines under field conditions: an evaluation of stomatal and mesophyll limitations. Funct. Plant Biol. 29, 461–471. doi: 10.1071/pp01119

Flexas, J., Bota, J., Loreto, F., Cornic, G., Sharkey, T. D. (2004). Diffusive and metabolic limitations to photosynthesis under drought and salinity in C3 plants. Plant Biol. 6, 269–279. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-820867

Flexas, J., Medrano, H. (2002). Drought-inhibition of photosynthesis in C3 plants: Stomatal and non-stomatal limitations revisited. Ann. Bot. 89, 183–189. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcf027

Flexas, J., Ortuño, M. F., Ribas-Carbo, M., Diaz-Espejo, A., Flórez-Sarasa, I. D., Medrano, H. (2007). Mesophyll conductance to CO2 in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 175, 501–511. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02111.x

Flexas, J., Ribas-Carbó, M., Hanson, D. T., Bota, J., Otto, B., Cifre, J., et al. (2006). Tobacco aquaporin NtAQP1 is involved in mesophyll conductance to CO2in vivo. Plant J. 48, 427–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02879.x

Galmés, J., Medrano, H., Flexas, J. (2007). Photosynthetic limitations in response to water stress and recovery in Mediterranean plants with different growth forms. New Phytol. 175, 81–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02087.x

Genty, B., Briantais, J. M., Baker, N. R. (1989). The relationship between the quantum yield of photosynthetic electron transport and quenching of chlorophyll fluorescence. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 990, 87–92. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4165(89)80016-9

Gonzalez-Paleo, L., Ravetta, D. A. (2018). Relationship between photosynthetic rate, water use and leaf structure in desert annual and perennial forbs differing in their growth. Photosynthetica 56, 1177–1187. doi: 10.1007/s11099-018-0810-z

Grassi, G., Magnani, F. (2005). Stomatal, mesophyll conductance and biochemical limitations to photosynthesis as affected by drought and leaf ontogeny in ash and oak trees. Plant Cell Environ. 28, 834–849. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2005.01333.x

Harley, P. C., Loreto, F., Di Marco, G., Sharkey, T. D. (1992). Theoretical considerations when estimating the mesophyll conductance to CO2 flux by analysis of the response of photosynthesis to CO2. Plant Physiol. 98, 1429–1436. doi: 10.1104/pp.98.4.1429

He, W. J., Yan, K., Zhang, Y., Bian, L. X., Mei, H. M., Han, G. X. (2021). Contrasting photosynthesis, photoinhibition and oxidative damage in honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica Thunb.) under iso-osmotic salt and drought stresses. Environ. Exp. Bot. 182, 104313. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2020.104313

Hussain, S., Shaukat, M., Ashraf, M., Zhu, C. Q., Jin, Q.-Y., Zhang, J. (2019). Salinity stress in arid and semi-arid climates: effects and management in field crops. Climate Change Agric. 13, 201–226. doi: 10.5772/intechopen.87982

Li, S., Liu, J. M., Liu, H., Qiu, R. J., Gao, Y., Duan, A. W. (2021). Role of hydraulic signal and ABA in decrease of leaf stomatal and mesophyll conductance in soil drought-stressed tomato. Front. Plant Sci. 12. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.653186

Liakoura, V., Fotelli, M. N., Rennenberg, H., Karabourniotis, G. (2009). Should structure-function relations be considered separately for homobaric vs. heterobaric leaves? Am. J. Bot. 96, 612–619. doi: 10.3732/ajb.0800166

Limousin, J.-M., Misson, L., Lavoir, A.-V., Martin, N., Rambal, S. (2010). Do photosynthetic limitations of evergreen Quercus ilex leaves change with long-term increased drought severity? Plant Cell Environ. 33 5, 863–875. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.02112.X

Liu, M., Liu, X. C., Du, X. H., Korpelainen, H., Niinemets, Ü., Li, C. Y. (2021). Anatomical variation of mesophyll conductance due to salt stress in Populus cathayana females and males growing under different inorganic nitrogen sources. Tree Physiol. 41, 1462–1478. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpab017

Liu, M., Liu, X. C., Zhao, Y., Korpelainen, H., Li, C. Y. (2022). Sex-specific nitrogen allocation tradeoffs in the leaves of Populus cathayana cuttings under salt and drought stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 172, 101–110. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2022.01.009

Melo, A. S., Yule, T. S., Barros, V. A., Rivas, R., Santos, M. G. (2021). C3-species Calotropis procera increase specific leaf area and decrease stomatal pore size, alleviating gas exchange under drought and salinity. Acta Physiol. Plant 43, 1–11. doi: 10.1007/s11738-021-03312-3

Miyazawa, S. I., Terashima, I. (2001). Slow development of leaf photosynthesis in an evergreen broad-leaved tree, Castanopsis sieboldii: relationships between leaf anatomical characteristics and photosynthetic rate. Plant Cell Environ. 24, 279–291. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3040.2001.00682.x

Nadal, M., Flexas, J. (2018). “Mesophyll conductance to CO2 diffusion: effects of drought and opportunities for improvement,” in Water Scarcity and Sustainable Agriculture in Semiarid Environment. Eds. García-Tejero, I. F., Durán-Zuazo, V. H. (Elsevier, Academic Press, London), 403–438.

Neto, M. C. L., Cerqueira, J. V. A., Da Cunha, J. R., Ribeiro, R. V., Silveira, J. (2017). Cyclic electron flow, NPQ and photorespiration are crucial for the establishment of young plants of Ricinus communis and Jatropha curcas exposed to drought. Plant Biol. 19, 650–659. doi: 10.1111/plb.12573

Niinemets, Ü., Cescatti, A., Rodeghiero, M., Tosens, T. (2005). Leaf internal diffusion conductance limits photosynthesis more strongly in older leaves of Mediterranean evergreen broad-leaved species. Plant Cell Environ. 28, 1552–1566. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2005.01392.x

Niinemets, Ü., Tenhunen, J. (1997). A model separating leaf structural and physiological effects on carbon gain along light gradients for the shade-tolerant species Acer saccharum. Plant Cell Environ. 20, 845–866. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3040.1997.d01-133.x

Oi, T., Enomoto, S., Nakao, T., Arai, S., Yamane, K., Taniguchi, M. (2020). Three-dimensional ultrastructural change of chloroplasts in rice mesophyll cells responding to salt stress. Ann. Bot. 125, 833–840. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcz192

Onoda, Y., Wright, I. J., Evans, J. R., Hikosaka, K., Kitajima, K., Niinemets, Ü., et al. (2017). Physiological and structural tradeoffs underlying the leaf economics spectrum. New Phytol. 214, 1447–1463. doi: 10.1111/nph.14496

Piel, C., Frak, E., Le Roux, X., Genty, B. (2002). Effect of local irradiance on CO2 transfer conductance of mesophyll in walnut. J. Exp. Bot. 53, 2423–2430. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erf095

Pinnola, A., Bassi, R. (2018). Molecular mechanisms involved in plant photoprotection. Biochem. Soc Trans. 46, 467–482. doi: 10.1042/bst20170307

Ridenour, W. M., Vivanco, J. M., Feng, Y. L., Horiuchi, J., Callaway, R. M. (2008). No evidence for trade-offs: Centaurea plants from America are better competitors and defenders. Ecol. Monogr. 78, 369–386. doi: 10.1890/06-1926.1

Roig-Oliver, M., Bresta, P., Nadal, M., Liakopoulos, G., Nikolopoulos, D., Karabourniotis, G., et al. (2020). Cell wall composition and thickness affect mesophyll conductance to CO2 diffusion in Helianthus annuus under water deprivation. J. Exp. Bot. 71, 7198–7209. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eraa413

Scoffoni, C., Sack, L. (2017). The causes and consequences of leaf hydraulic decline with dehydration. J. Exp. Bot. 68, 4479–4496. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erx252

Sharkey, T. D. (2016). What gas exchange data can tell us about photosynthesis. Plant Cell Environ. 39, 1161–1163. doi: 10.1111/pce.12641

Stavridou, E., Webster, R. J., Robson, P. R. H. (2019). Novel Miscanthus genotypes selected for different drought tolerance phenotypes show enhanced tolerance across combinations of salinity and drought treatments. Ann. Bot. 124, 653–674. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcz009

Takashima, T., Hikosaka, K., Hirose, T. (2004). Photosynthesis or persistence: nitrogen allocation in leaves of evergreen and deciduous Quercus species. Plant Cell Environ. 27, 1047–1054. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2004.01209.x

Terashima, I., Araya, T., Miyazawa, S., Sone, K., Yano, S. (2005). Construction and maintenance of the optimal photosynthetic systems of the leaf, herbaceous plant and tree: an eco-developmental treatise. Ann. Bot. 95, 507–519. doi: 10.1093/aob/mci049

Terashima, I., Hanba, Y. T., Tholen, D., Niinemets, Ü. (2011). Leaf functional anatomy in relation to photosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 155, 108–116. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.165472

Tholen, D., Ethier, G., Genty, B., Pepin, S., Zhu, X. G. (2012). Variable mesophyll conductance revisited: theoretical background and experimental implications. Plant Cell Environ. 35, 2087–2103. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2012.02538.x

Tholen, D., Zhu, X. G. (2011). The mechanistic basis of internal conductance: A theoretical analysis of mesophyll cell photosynthesis and CO2 diffusion. Plant Physiol. 156, 90–105. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.172346

Tomás, M., Flexas, J., Copolovici, L., Galmés, J., Hallik, L., Medrano, H., et al. (2013). Importance of leaf anatomy in determining mesophyll diffusion conductance to CO2 across species: quantitative limitations and scaling up by models. J. Exp. Bot. 64, 2269–2281. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert086

Tosens, T., Niinemets, Ü., Vislap, V., Eichelmann, H., Díez, P. C. (2012). Developmental changes in mesophyll diffusion conductance and photosynthetic capacity under different light and water availabilities in Populus tremula: how structure constrains function. Plant Cell Environ. 35, 839–856. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2011.02457.x

Villar, R., Held, A. A., Merino, J. (1995). Dark leaf respiration in light and darkness of an evergreen and a deciduous plant species. Plant Physiol. 107, 421–427. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.2.421

Walker, A. P., Beckerman, A. P., Gu, L. H., Kattge, J., Cernusak, L. A., Domingues, T. F., et al. (2014). The relationship of leaf photosynthetic traits - Vcmax and Jmax - to leaf nitrogen, leaf phosphorus, and specific leaf area: a meta-analysis and modeling study. Ecol. Evol. 4, 3218–3235. doi: 10.1002/ece3.1173

Wang, L., Cui, J. W., Jin, B., Zhao, J. G., Xu, H. M., Lu, Z. G., et al. (2020). Multifeature analyses of vascular cambial cells reveal longevity mechanisms in old Ginkgo biloba trees. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117, 2201–2210. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1916548117

Wang, W. X., Vinocur, B., Altman, A. (2003). Plant responses to drought, salinity and extreme temperatures: towards genetic engineering for stress tolerance. Planta 218, 1–14. doi: 10.1007/s00425-003-1105-5

Wang, X. X., Du, T. T., Huang, J. L., Peng, S. B., Xiong, D. L. (2018b). Leaf hydraulic vulnerability triggers the decline in stomatal and mesophyll conductance during drought in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 69, 4033–4045. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ery188

Wang, X. X., Wang, W. C., Huang, J. L., Peng, S. B., Xiong, D. L. (2018a). Diffusional conductance to CO2 is the key limitation to photosynthesis in salt-stressed leaves of rice (Oryza sativa). Physiol. Plant 163, 45–58. doi: 10.1111/ppl.12653

Xiong, D. L., Flexas, J. (2018). Leaf economics spectrum in rice: leaf anatomical, biochemical, and physiological trait trade-offs. J. Exp. Bot. 69, 5599–5609. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ery322

Yamori, W., Shikanai, T. (2016). Physiological functions of cyclic electron transport around photosystem I in sustaining photosynthesis and plant growth. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 67, 81–106. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-043015-112002

Yao, H., Zhang, Y., Yi, X., Zhang, X., Fan, D., Chow, W. S., et al. (2018). Diaheliotropic leaf movement enhances leaf photosynthetic capacity and photosynthetic light and nitrogen use efficiency via optimising nitrogen partitioning among photosynthetic components in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.). Plant Biol. 20, 213–222. doi: 10.1111/plb.12678

Zait, Y., Shtein, I., Schwartz, A. (2019). Long-term acclimation to drought, salinity and temperature in the thermophilic tree Ziziphus spina-christi: revealing different tradeoffs between mesophyll and stomatal conductance. Tree Physiol. 39, 701–716, 4201. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpy133

Zhao, Y. P., Fan, G. Y., Yin, P. P., Sun, S., Li, N., Hong, X. N., et al. (2019). Resequencing 545 ginkgo genomes across the world reveals the evolutionary history of the living fossil. Nat. Commun. 10, 4201. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12133-5

Zhao, Y. P., Paule, J., Fu, C. X., Koch, M. A. (2010). Out of China: Distribution history of Ginkgo biloba L. Taxon 59, 495–504. doi: 10.1002/tax.592014

Zhi, H., Xia, Q. (2023). Study on the effect of different proportions of organic solvents on extracting pigments from formaldehyde removal plant leaves. Anhui Agric. Sci. 51, 1–4,10. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.0517-6611.2023.16.001

Zhong, C., Jian, S. F., Huang, J., Jin, Q. Y., Cao, X. C. (2019). Trade-off of within-leaf nitrogen allocation between photosynthetic nitrogen-use efficiency and water deficit stress acclimation in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Physiol. Biochem. 135, 41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2018.11.021

Keywords: combined drought-salt stress, drought stress, leaf nitrogen allocation ratio, mesophyll conductance, photosynthesis, salt stress

Citation: Li L, Zhou K, Yang X, Su X, Ding P, Zhu Y, Cao F and Han J (2025) Leaf nitrogen allocation to non-photosynthetic apparatus reduces mesophyll conductance under combined drought-salt stress in Ginkgo biloba. Front. Plant Sci. 16:1557412. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2025.1557412

Received: 08 January 2025; Accepted: 22 January 2025;

Published: 12 February 2025.

Edited by:

Majid Sharifi-Rad, Zabol University, IranReviewed by:

Shubin Zhang, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), ChinaCopyright © 2025 Li, Zhou, Yang, Su, Ding, Zhu, Cao and Han. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jimei Han, amltYXloYW5AbmpmdS5lZHUuY24=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.