94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Plant Sci., 29 January 2025

Sec. Plant Physiology

Volume 15 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2024.1474431

This article is part of the Research TopicRegeneration of Plant Organs in Vitro and Its Mechanistic BasisView all 5 articles

Based on the totipotency and pluripotency of cells, plants are endowed with strong regenerative abilities. Light is a critical environmental factor influencing plant growth and development, playing an important role in plant regeneration. In this article, we provide a detailed summary of recent advances in understanding the effects of light on plant regeneration, with a focus on the fundamental processes and mechanisms involved in de novo shoot regeneration, somatic embryogenesis, and adventitious root formation. We focus on summarizing the effects of light intensity, light spectra, and photoperiod on these regeneration processes. Additionally, we propose the molecular mechanisms and regulatory networks underlying light-mediated plant regeneration. This article aims to deepen our understanding of the role of light in plant regeneration and to pave the way for future research on light-regulated regenerative processes in plants.

Plants possess various mechanisms to adapt to their external environment, with regeneration being one of their most critical survival strategies. The totipotency of plant cells—a foundational principle in plant biology—was first discovered in 1958 when Steward and colleagues successfully regenerated entire plants from a single cell derived from the phloem tissue of Daucus carota L (Steward et al., 1958; Reinert, 1958). Plant regeneration is a process based on cellular totipotency, which enables plants to repair themselves and re-differentiate lost cells or form new organs near sites of injury. Plant regeneration is typically classified into three main processes: organogenesis, somatic embryogenesis, and tissue repair. First, in a medium supplemented with plant growth regulators, isolated plant tissues can undergo dedifferentiation to form callus, which then differentiates into complete plants. This process is referred to as de novo organogenesis. The ratio of auxin to cytokinin is a critical factor in determining the process of de novo organogenesis. When isolated plant tissues are in a higher ratio of cytokinin to auxin, adventitious shoots are regenerated near the wounds. Callus formation occurs under higher concentrations of auxin, while adventitious root (AR) is induced under lower concentrations of auxin (Skoog and Miller, 1957; Zhai and Xu, 2021). Different from plant organogenesis, somatic plant cells can also be induced to form somatic embryos under the influence of plant growth regulators or stress. These somatic embryos can further develop into complete plants. This process, known as somatic embryogenesis, is characterized by a high reproduction rate and good stability. As the mechanisms of plant regeneration have been increasingly elucidated, numerous plant regeneration systems have been established (Hua et al., 2013; Ikeda-Iwai et al., 2003; Gao et al., 2020; Tiidema and Truve, 2004). In addition, plants possess the ability to repair damaged tissues, restoring them to their original state, for example, the regeneration of new root tips following root tip excision and the healing of wounds during grafting (Feldman, 1976; Sena et al., 2009). Recent studies on plant regeneration, both mechanistic and applied, have been rapidly increasing. Emerging technologies have greatly advanced plant regeneration processes. With the continuous progress in plant genetic transformation and the development of technologies such as CRISPR-Cas9, it has become easier to conduct in-depth analyses of plant regeneration mechanisms and to apply plant regeneration technologies more widely (Lin et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2024).

Light is a key environmental factor that influences plant growth and development, playing a role in processes such as seed germination, leaf development, circadian rhythms, and shade avoidance responses (Shah et al., 2021, 2024; Yan et al., 2024). Plants possess a variety of photoreceptors to detect light of different wavelengths. Phytochromes (PHYs: PHYA–PHYE) are sensitive to red and far-red light within the wavelength range of 600–760 nm. Cryptochromes (CRYs: CRY1, CRY2, and CRY-DASH), phototropins (PHOTs: PHOT1 and PHOT2), and zeitlupe (ZTL) primarily perceive ultraviolet light (320–400 nm) and blue light (400–500 nm) (Franklin and Quail, 2010; Christie, 2007; Pudasaini and Zoltowski, 2013; Kami et al., 2010). Photoreceptors transmit light signals to downstream regulatory factors, such as PHYTOCHROME-INTERACTING FACTORS (PIFs), ELONGATED HYOCOTYL 5 (HY5), and CONSTITUTIVE PHOTOMORPHOGENIC 1 (COP1) (Bhatnagar et al., 2020; Xu, 2020). These conserved light-responsive signaling factors then regulate downstream genes and proteins involved in plant regeneration. For example, HY5 inhibits the adventitious shoot regeneration by regulating the cytokinin-responsive factor ARABIDOPSIS RESPONSE REGULATOR 12 (ARR12) and WUSCHEL (WUS), both of which are involved in the adventitious shoot regeneration of Arabidopsis (Dai et al., 2022). PHYB and PHYE promote somatic embryogenesis by regulating auxin synthesis genes, such as AMIDASE 1 (AMI1), and jasmonic acid (JA)-responsive genes, such as DE-ETIOLATED-2 (DET2) (Chan and Stasolla, 2023; Mira et al., 2023). Under dark conditions, PIFs directly bind to the promoters of LATERAL ORGAN BOUNDARIES DOMAIN 16/29 (LBD16/29), which are involved in AR formation, thereby regulating the development of hypocotyl adventitious root (HAR) in Arabidopsis (Li et al., 2022b).

The effects of light on plant regeneration are broad. Light intensity, light spectra, and photoperiod are three attributes of light, all of which have complex and diverse effects on plant regeneration. Here, we discuss the effects of light on de novo shoot organogenesis, somatic embryogenesis, and AR regeneration. We summarize the molecular mechanisms and regulatory networks of light-regulated de novo shoot organogenesis, somatic embryogenesis, and AR regeneration, which provided important references for understanding and deeper investigation of light-influenced plant regeneration.

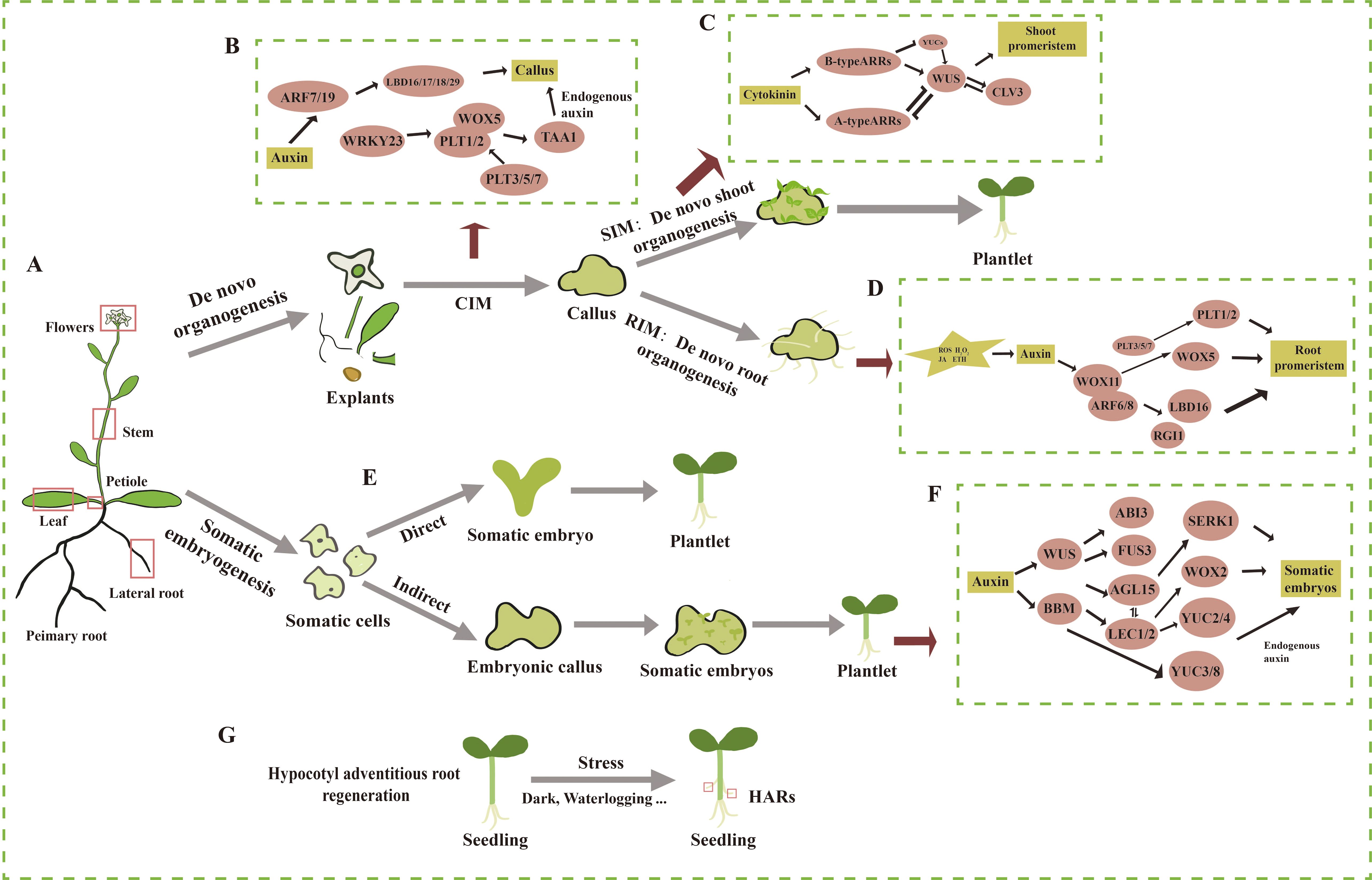

Shoot organogenesis can also occur directly, bypassing the callus stage (Liu J. et al., 2022). In fact, even lateral root meristems can differentiate directly into shoot meristems without the formation of callus (Rosspopoff et al., 2017). This section focuses on the process of de novo shoot regeneration, which involves two key steps (Figure 1). First, isolated plant organs or tissues are placed on callus induction medium (CIM), which induces callus formation (Figure 1B). Callus typically originates from vascular cells or xylem pole pericycle cells. In response to auxin in the CIM, these cells undergo cell division, leading to the development of callus with characteristics of lateral root meristems (Atta et al., 2009; Sugimoto et al., 2010). At this stage, marker genes for root meristems, such as AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR 7/19 (ARF7/19), are expressed, which in turn induce the expression of four downstream transcription factors LBD16/17/18/29 (Fan et al., 2012). These LBDs regulate callus formation through the modulation of cell wall modification, cell cycle, and cell division (Berckmans et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2018a, b). After callus formation, it must acquire pluripotency to proceed to the next stage of differentiation. PLETHORA (PLTs), a family of transcription factors involved in stem cell maintenance, play a key role in this process (Sang et al., 2018). WRKY23, located downstream of ARF7/19, indirectly activates the transcription of WUSCHEL-RELATED HOMEOBOX 5 (WOX5) and PLT1/2 by upregulating PLT3 and PLT7, thereby promoting the acquisition of pluripotency in the callus. In plt3/5/7 mutants, the expression of PLT1 and PLT2 is downregulated, resulting in the loss of pluripotency. Furthermore, the removal of bHLH041, induced by LBD16, alleviates its transcriptional repression of PLT1, PLT2, and WOX5 (Xu et al., 2023; Kareem et al., 2015). Additionally, WOX5 and PLT1/2 interact to regulate the downstream expression of the auxin biosynthesis gene TRYPTOPHAN AMINOTRANSFERASE OF ARABIDOPSIS 1 (TAA1), thereby promoting the synthesis of endogenous auxin in plants (Zhai and Xu, 2021).

Figure 1. Overview of the processes and regulatory mechanisms of de novo shoot organogenesis, de novo root organogenesis, somatic embryogenesis, and hypocotyl adventitious root regeneration in the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana. (A) Schematic of an Arabidopsis plant where primary and lateral organs are shown. (B) The process and molecular mechanisms of dedifferentiation of explants in vitro on callus induction medium (CIM) to form pluripotent callus. (C) The process and molecular mechanisms of pluripotent callus regenerating adventitious shoots on shoot induction medium (SIM). (D) The process and molecular mechanisms of pluripotent callus regenerating adventitious roots on root induction medium (RIM). (E) The process of direct somatic embryogenesis. (F) The process and molecular mechanisms of indirect somatic embryogenesis. (G) The process of hypocotyl adventitious root (HAR) formation. The straight arrow represents activation, the connection of the blunt end represents suppression, and parallel lines indicate interactions.

Second, pluripotent callus undergoes continuous cell division and differentiation in the presence of cytokinin and auxin after being transferred to shoot induction medium (SIM) (Figure 1C) (Duclercq et al., 2011). Within 2–3 days of transfer to SIM, WUS is strongly expressed and plays a key role in the reconstitution of the early stem cell center, marking its formation (Zhang et al., 2017) (Figure 1). Cytokinin induces the expression of WUS, with ARR12 directly binding to the WUS promoter to enhance its expression (Zhang et al., 2017). In turn, WUS inhibits auxin signals and type A ARRs to facilitate de novo shoot organogenesis (Buechel et al., 2010; Negin et al., 2017). The expression of WUS is restricted to the base of the stem cell center, while PIN-FORMED1 (PIN1) and CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON2 (CUC2) are expressed in the apical region, forming a protruding structure. WUS interacts with CLAVATA3 (CLV3) in a negative feedback loop, maintaining stem cell homeostasis while marking the zones of shoot initiation (Brand et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2017). As WUS expression shifts upward, CUC2 is expressed in the peripheral region of the stem cell center (Kareem et al., 2016), while PIN1 is expressed in the outer cells of the meristem. At this point, a shoot apical meristem is established, which then differentiates into organs.

Epigenetic regulation has also been shown to play a role in regulating de novo shoot organogenesis. For instance, explants from the hypomethylated fwa-1 mutant, which exhibits an elevated expression of FLOWERING WAGENINGEN (FWA), displayed reduced shoot regeneration compared to the wild type (Dai et al., 2021). Further experiments demonstrated that FWA inhibited adventitious shoot regeneration by binding to the promoter of WOX9. During shoot induction, histone deacetylase 19 (HDA19) suppressed the expression of CUC2 by acetylating histones at the CUC2 locus, thereby inhibiting adventitious shoot regeneration (Temman et al., 2023).

Light intensity is a critical factor influencing de novo shoot organogenesis (Table 1). Plants can be categorized as either light-sensitive or light-demanding, depending on the light intensity required for successful regeneration (Rikiishi et al., 2015). It is generally believed that lower light intensities favor callus and adventitious shoot formation in light-sensitive plants. For example, Chen and co-workers found that low light intensity helps maintain the normal physiological state of callus induced from isolated leaves and stem segments of Actinidia arguta, preserving its green color and compact structure (Chen et al., 2019). However, as light intensity increased, the callus of A. arguta and Haworthia became browner, and the proliferation rate gradually decreased. Additionally, low light intensity was found to promote an increase in callus biomass (Sui et al., 2021). Lower light intensity also facilitates adventitious shoot formation in light-sensitive plants. Nameth and co-workers demonstrated that low-intensity light enhanced the regeneration of adventitious shoots from cotyledon explants of two Arabidopsis genotypes, ‘Ler’ and ‘DijG’. The efficiency of regeneration increased as light intensity decreased. This effect was attributed to the higher production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the depletion of the photoprotective pigment zeaxanthin at higher light intensities, leading to severe photo-oxidative damage (Nameth et al., 2013). A similar increase in adventitious shoot regeneration was observed in Parthenium argentatum when light intensity was reduced from 48 to 12 μmol·m−2·s−1, resulting in a twofold increase in both the number of explants producing shoots and the total number of shoots (Dong et al., 2006). The beneficial effect of low light intensity on adventitious shoot regeneration has also been observed in other species, including apple and Phoenix dactylifera L (Dobránszki and Teixeira Da Silva, 2011; Meziani et al., 2015).

In contrast to light-sensitive plants, light-promoted plants require high-intensity light for callus and adventitious shoot formation. For example, the rate of callus induction in Nicotiana tabacum L. was higher under a high light intensity of 3,000 lux (approximately 55.56 μmol·m−2·s−1) compared to dark conditions. Callus developed in the dark appeared watery and glossy silver in color, with fewer embryogenic potential (Siddique and Islam, 2018). Similarly, more calli were induced from hypocotyls of Linum usitatissimum L. at 150 μmol·m−2·s−1 compared to 75 μmol·m−2·s−1 (Caillot et al., 2009). This increase in callus formation was attributed to the higher sucrose utilization by the explants under high light intensity (Farhadi et al., 2017). Additionally, explants of Cucumis melo L. and Brassica oleracea var. botrytis L. produced a greater number of adventitious shoots under high light intensity (Kumar et al., 1993; Leshem et al., 1995). In summary, light intensity influences the dedifferentiation process of explants by affecting the state and browning degree of the callus, and it also impacts the differentiation process of adventitious shoots by modulating sucrose utilization in the explants.

Blue, red, far-red, and mixed light wavelengths are extensively utilized in plant regeneration studies (Table 1). The explants of plant species complete their regeneration process by responding to different photoreceptors under various light spectra. Studies have shown that blue, red, or a combination of red and blue light can significantly promote the regeneration of adventitious shoots. For example, callus of Cnidium officinale Makino grown under blue light exhibited a compact texture and showed shoot regeneration after sub-culturing, while friable and watery non-regenerative callus was observed under dark or red light (Adil et al., 2019). Blue light has also been shown to enhance the antioxidant activity in the callus of Operculina turpethum L. and Eutrema salsugineum. In O. turpethum L., the levels of total phenols and flavonoids increased, and in E. salsugineum, the activities of key antioxidant enzymes, such as catalase (CAT) and peroxidase (POD), were higher in callus grown under blue light compared to that cultivated under white light (Biswal et al., 2022; Pashkovskiy et al., 2018). Additionally, blue light promoted biomass accumulation in the callus of O. turpethum L. and Cistanche deserticola (Ouyang et al., 2003). A similar effect was observed in the regeneration of Arachis hypogaea, where leaf explants formed only callus that could not differentiate under white light but formed adventitious shoots under blue light (Assou et al., 2023). Red light promoted callus biomass accumulation in Rhodiola imbricata and Hordeum vulgare L (Kapoor et al., 2018; Rikiishi et al., 2008). Active phytochromes under red light stimulated the synthesis and activity of growth-related enzymes, which also promoted the formation of shoot meristems in the callus of Begonia × erythrophylla. Each explant produced more than 25 shoots (Burritt and Leung, 2003). Hypocotyl explants of Solanum lycopersicum L. exhibited higher regeneration efficiency under red light, with adventitious shoot regeneration rates significantly lower in the phyb mutant compared to white light conditions (Lercari and Bertram, 2004). Shoot tips of Swertia chirata showed the highest chlorophyll, carotenoid, and polyphenol contents as well as the greatest efficiency of adventitious shoot regeneration under mixed red and blue light (Dutta Gupta and Karmakar, 2017). Mixed red and blue light also increased the adventitious shoot regeneration rate in Rubus fruticosus L. and Rubus idaeus L. by promoting cell division, maintaining the redox state (Hassanpour, 2022), and regulating the cell cycle (Kwon et al., 2015; Loshyna et al., 2022). Additionally, white or yellow light facilitated adventitious shoot regeneration in Populus alba × Populus berolinensis, whereas green light inhibited this process of P. alba × P. berolinensis (Wang et al., 2008).

In conclusion, light spectra significantly influence callus growth, proliferation, and antioxidant activity by modulating the activity of photosensitive pigments, which in turn upregulate genes encoding growth-related enzymes. The application of appropriate light spectra enhances cell viability and regulates the cell cycle, thereby ensuring that the callus remains capable of both proliferation and differentiation. Moreover, light spectra play a crucial role in the regeneration of adventitious shoots by affecting photosynthesis and promoting the formation of shoot meristems. Understanding the molecular mechanisms through which light spectra regulate these processes is essential for comprehending the role of light in plant regeneration.

The 16/8-h light/dark photoperiod is crucial for plant growth and development, and different photoperiods have distinct effects on adventitious shoot regeneration (Table 1). In some plant species, de novo shoot organogenesis is promoted in darkness. For example, in Arabidopsis, darkness treatment led to the regeneration of more adventitious shoots from excised explants compared to the 16/8-h photoperiod (Nameth et al., 2013). The inhibitory effect of light at culture initiation on the adventitious shoot regeneration was alleviated by the addition of N-1-naphthylphthalamic acid (NPA), an auxin polar transport inhibitor. Ethylene synthesis was also regulated by light, with ethylene levels increasing under darkness. The addition of the ethylene precursor, 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC), further promoted adventitious shoot formation under darkness (Nameth et al., 2013). The above suggests that light photoperiod regulates adventitious shoot regeneration by influencing auxin polar transport and ethylene levels. Wei and co-workers demonstrated that genes involved in the synthesis and signaling of auxin, cytokinin, and ethylene were differentially expressed in darkness during the culture initiation. Additionally, key factors directly involved in adventitious shoot regeneration, such as LBD16, PLT3, WOX5, WUS, and SHOOT MERISTEMLESS (STM), were highly expressed under darkness in Arabidopsis (Wei et al., 2020). In Erigeron breviscapus, darkness for 15 days resulted in a significant increase in adventitious shoots number, with a regeneration efficiency of 82.6% (Xing et al., 2008). Woody plants, which typically have longer cultivation periods, are prone to producing phenolic compounds and oxidative enzymes during regeneration. However, after 20 days of darkness, the shoot regeneration rate in Citrus reticulata Blanco reached 100%, with an average of 13.2 shoots regenerated per explant. Under a 16/8-h photoperiod, the regeneration rate was only 72.5%, with an average of 7.8 shoots regenerated per explant (Zeng et al., 2009). Similarly, darkness also promoted the regeneration of adventitious shoots in Malus × domestica Borkh and Prunus persica L (Caboni et al., 2000; Gentile et al., 2002).

Photoperiods with extended light durations have also been shown to promote adventitious shoot regeneration in some plant species. In the S. lycopersicum cultivar Micro-Tom, no significant difference in regeneration was observed between tomato leaf explants pre-cultured under darkness for 8 days and those under 16/8-h photoperiod (Song et al., 2023). However, under a 16/8-h photoperiod, numerous light-regulated chlorenchyma cells containing chloroplast-like structures appeared near the sites of adventitious shoot primordium formation. When the photosynthesis inhibitor 3-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)-1,1-dimethylurea (DCMU) was applied to inhibit photosynthesis in these cells, the number of adventitious shoots regenerated from the leaves decreased. This indicates that these cells provide essential energy for the formation of adventitious shoot primordia and highlights the role of photosynthesis in adventitious shoot formation. Additionally, the highest expression levels of regeneration-related genes, such as PLT3 and STM, are observed under a 16/8-h photoperiod (Song et al., 2023). In Oryza sativa L., during the regeneration of adventitious shoots from pluripotent callus, the number of adventitious shoots increased progressively with longer light durations and reached its maximum under a 16/8-h photoperiod (Liu et al., 2001). In summary, photoperiod affects plant regeneration by influencing the synthesis and transport of various hormones, photosynthesis, the synthesis of phenolic compounds, and cell fate transition during adventitious shoot regeneration.

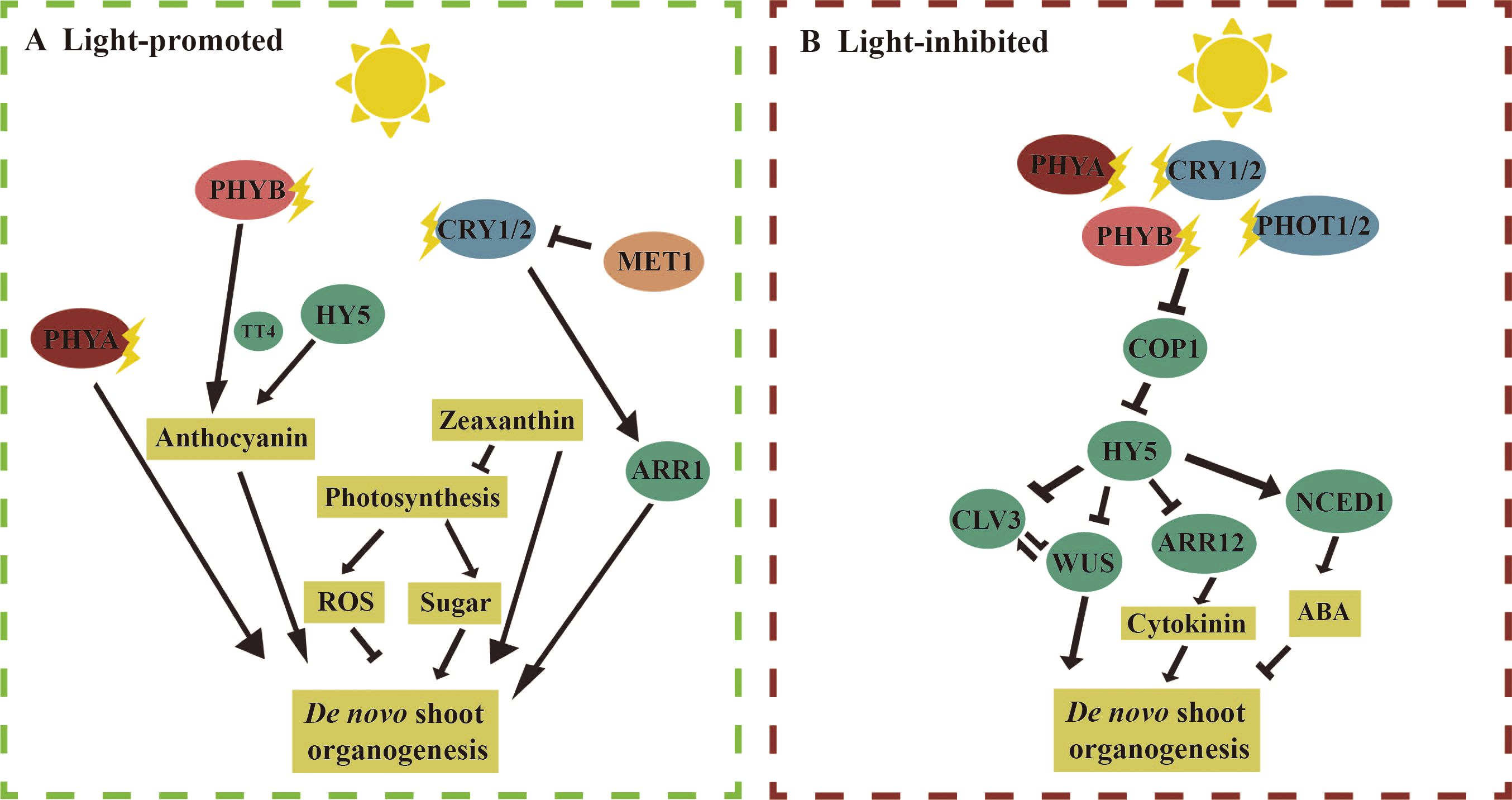

Light regulates de novo shoot organogenesis through a complex network that involves both positive and negative regulatory pathways. Multiple regulatory pathways can exist for the same light-responsive factors, acting through both positive and negative mechanisms. Here, we first review the molecular mechanisms associated with light-promoted adventitious shoot regeneration (Figure 2A). Phytochromes PHYA, PHYB, and CRY1 are the primary receptors that sense light signals and directly regulate downstream factors involved in adventitious shoot regeneration. In Arabidopsis ‘Ler’ and tomato, the ability to regenerate adventitious shoots was significantly impaired in the phyA mutant (Lercari and Bertram, 2004; Nameth et al., 2013; Saitou et al., 1999). Both PHYB and HY5 directly regulated the anthocyanin synthase gene TT4, promoting adventitious shoot regeneration. It was found that the regeneration rate of adventitious shoots was significantly lower in hy5 and tt4 mutants compared to the wild type, and anthocyanins were absent in phyB mutants (Nameth et al., 2013). The cry1 mutant in Arabidopsis showed a reduced ability to regenerate adventitious shoots compared to the wild type. CRY1 in Arabidopsis promoted adventitious shoot regeneration by enhancing the expression of the cytokinin response factor ARR1. In the cry1 mutant, both adventitious shoot regeneration and the expression of ARR1 were significantly reduced (Shim et al., 2021). Additionally, immature embryos of the bare cultivar ‘LN’ exhibited higher auxin content under a 16/8-h photoperiod, suggesting that light may influence adventitious shoot regeneration by regulating auxin levels (Rikiishi et al., 2015). Light also indirectly affected adventitious shoot regeneration in Arabidopsis and tomato by modulating photosynthesis, ROS, and photoprotective zeaxanthin. For example, the photosynthesis inhibitor DCMU significantly reduced the rate of callus regeneration. Furthermore, reduced levels of photoprotective zeaxanthin were observed in non-photochemical quenching 1 (npq1) mutants, which caused a significant reduction in adventitious shoot regeneration from cotyledons both in light and darkness (Nameth et al., 2013; Song et al., 2023). These pathways and the key factors involved in these processes remain to be further explored. Additionally, epigenetic regulation plays a role in light-induced adventitious shoot regeneration. For example, the DNA methyltransferase MET1 inhibited the expression of the CRY1 by methylating the DNA at the CRY1 locus, thereby reducing adventitious shoot regeneration in Arabidopsis. In contrast, the met1 mutant displayed enhanced adventitious shoot regeneration (Shim et al., 2021).

Figure 2. Molecular mechanism of light regulation of de novo shoot organogenesis. [(A), left] Light promotes de novo shoot organogenesis: in Arabidopsis, under light conditions, compared to the wild type, the phytochrome A (phyA) mutant produced fewer adventitious shoots from cotyledon explants. Phytochrome B (PHYB) and ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL 5 (HY5) receive light signals and promote anthocyanin synthesis by regulating the expression of the anthocyanin synthase gene TRANSPARENT TESTA 4 (TT4), which in turn promotes de novo shoot regeneration. CRY1/2 enhances the Arabidopsis response factor 1 (ARR1) to promote adventitious shoot regeneration. Additionally, in both tomato and Arabidopsis, light may promote the synthesis of zeaxanthin, reactive oxygen species (ROS), and sugar to support adventitious shoot regeneration. [(B), right] Light inhibits de novo shoot organogenesis: PHYA/B and CRY1/2 regulate light signaling under blue and red light by inhibiting CONSTITUTIVE PHOTOMORPHOGENIC 1 (COP1) activity and stabilizing HY5. During adventitious shoot regeneration in Arabidopsis root explants, HY5 can directly bind to the promoters of WUSCHEL (WUS) and CLAVATA3 (CLV3) to suppress their expression. HY5 can also inhibit the expression of Arabidopsis response factor 12 (ARR12) by binding to its promoter, further suppressing WUS expression. In barley, it is found that abscisic acid (ABA) inhibits adventitious shoot regeneration, and under light conditions, the expression level of the gene 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase 1 (NCED1), which encodes ABA synthase, increases. The straight arrow represents activation, the connection of the blunt end represents suppression, and parallel lines indicate interactions.

Next, we discuss the mechanisms involved in the inhibition of adventitious shoot regeneration by light (Figure 2B). In Arabidopsis ‘col’, it was observed that phyA mutant explants produced more adventitious shoots compared to the wild type, while the numbers of adventitious shoots were drastically reduced in phyB and cry1/cry2. These results suggest that PHYA inhibits adventitious shoot regeneration, whereas PHYB and CRY1/2 promote adventitious shoot regeneration. Previous studies have shown that PHYA/B and CRY1/2 inhibited COP1 activity and stabilized HY5 under blue and red light, respectively (Lu et al., 2015; Zuo et al., 2011). In the hy5-215 mutant, the number of adventitious shoots regenerated from the roots was significantly higher than in the wild type (Dai et al., 2022). Given that the phenotypes of cry1/cry2 and phyB mutants were opposite to those of hy5-215, these findings suggest that CRY1/2 and PHYB regulate adventitious shoot regeneration through multiple pathways, with the facilitative pathway dominating, further highlighting the complexity of light regulation in this process. In darkness, COP1 binds to HY5 to suppress its activity, while HY5 mediates light signaling under light (Xu, 2020). In Arabidopsis, the rate of adventitious shoot regeneration was significantly lower in the cop1 mutant and higher in the hy5 mutant compared with the wild type. HY5 is directly bound to the promoters of WUS and CLV3 to inhibit their expression, thereby suppressing adventitious shoot regeneration (Dai et al., 2022). Additionally, HY5 is also bound to the promoter of ARR12 to inhibit its expression, while ARR12 directly promotes WUS expression. Therefore, HY5 inhibits adventitious shoot regeneration through multiple pathways by downregulating downstream WUS expression. In the immature embryos of the barley ‘K3’, the expression of 9-CIS-EPOXYCAROTENOID DIOXYGENASE 1 (NCED1), an enzyme involved in abscisic acid (ABA) biosynthesis, was downregulated under darkness, leading to reduced ABA synthesis. Exogenous ABA, in turn, inhibited the regeneration of callus and adventitious shoots. This suggests that light also influences adventitious shoot regeneration by regulating both auxin and abscisic acid biosynthesis (Rikiishi et al., 2015).

Somatic embryogenesis can be classified as either direct (Figure 1E) or indirect, depending on whether embryonic callus is formed. Indirect somatic embryogenesis is the predominant form and involves three main stages (Figure 1F). First, somatic cells dedifferentiate to form callus; then, the callus acquires pluripotency and is capable of further differentiation; finally, the embryonic callus regenerates somatic embryos (Halperin, 1966; Raghavan, 2004). Indirect somatic embryogenesis has a higher propagation coefficient and is more effective for the conservation of valuable germplasm resources (Yang and Zhang, 2010). Numerous factors affect somatic embryogenesis, with explant type, the developmental stage of the mother plant, and auxin being among the most important factors (Wang et al., 2020). For example, the addition of 2,4-D promoted somatic embryogenesis in Arabidopsis by inhibiting the exocytosis of endogenous auxin (Karami et al., 2023). Auxin, in turn, further promoted somatic embryogenesis by activating the expression of cellular totipotency factors (Braybrook et al., 2006). In addition, various abiotic stresses also play a role in inducing somatic embryogenesis. For instance, desiccation treatment with PEG in the medium promoted somatic embryogenesis in Picea asperata and Cunninghamia lanceolata (Jing et al., 2017; Zhou et al., 2017). The addition of sucrose to the culture medium, as well as exposure to low or high temperatures and heavy metals treatment, has also been shown to be useful for the induction of somatic embryogenesis (Gao et al., 2022; Miroshnichenko et al., 2013; Fehér, 2015).

Somatic embryogenesis is regulated by several key transcription factors (Figure 1F), including WUS, BABY BOOM (BBM), LEAFY COTYLEDON 1/2 (LEC1/2), ABSCISIC ACID INSENSITIVE 3 (ABI3), and FUSCA 3 (FUS3) and AGAMOUS-LIKE 15 (AGL15), whose roles are conserved across plants (Figure 1). Most of these factors were induced by auxin (Horstman et al., 2017) and, in turn, promoted the synthesis of endogenous auxin. For example, BBM directly upregulated the expression of the auxin synthesis gene YUCCA 3/8 (YUC3/8) in Arabidopsis (Li et al., 2022a), and LEC2 activated the expression of YUC2 and YUC4 to promote auxin synthesis (Stone et al., 2008). Additionally, there is mutual regulation among these key factors. BBM transcriptionally regulated LEC1 and LEC2, as well as the two other LAFL genes, FUS3 and ABI3 (Horstman et al., 2017). WOX2 was strongly expressed during somatic embryogenesis in Arabidopsis overexpressing LEC2, compared to the wild type. CHIP-seq data showed that LEC2 is directly bound to the promoter of WOX2, promoting its expression (Wang et al., 2020). The expression of LEC2 and ABI3 was increased in 35Spro: AGL15 seeds (Braybrook et al., 2006; Zheng et al., 2009). AGL15 also activated the expression of SOMATIC EMBRYOGENESIS RECEPTOR-LIKE KINASE1 (SERK1) (Kwaaitaal and De Vries, 2007). Moreover, both AGL15 and FUS3 regulated the expression of Gibberellin 2-oxidase 6 (GA2ox6) to regulate gibberellin content in Arabidopsis and Glycine, thereby influencing somatic embryogenesis (Wang et al., 2004; Zheng et al., 2016). Epigenetic regulation also plays a role in somatic embryogenesis. For example, trichostatin A (TSA), an inhibitor of histone deacetylase (HDA), induced somatic embryogenesis in cotyledon explants of Arabidopsis in the absence of exogenous auxin, while significantly reducing HDA activity (Wójcikowska et al., 2018). The DNA methylation inhibitor 5-azacytidine (5-Aza-C) inhibited the formation of embryonic cell clusters in epidermal carrot cells and downregulated the expression of LEC1 during somatic embryogenesis in carrot (Yamamoto et al., 2005).

Light intensity significantly affects somatic embryogenesis (Table 2). In Aralia elata Miq., the induction rate of somatic embryos reached 88.89% under 2,000 lux (37.04 μmol·m−2·s−1). As the light intensity increased, the induction rate decreased, indicating that an optimal light intensity is beneficial for somatic embryo formation (Cheng et al., 2021b). Light promoted somatic embryogenesis from spinach root sections (Milojević et al., 2012). The number of SEs increased significantly with light intensity from 0 to 100 μmol·m−2·s−1 and then decreased at 150 μmol·m−2·s−1, and the regeneration of SEs started 4 weeks earlier in explants cultured at 100 μmol·m−2·s−1 than at 150 μmol·m−2·s−1 or in the dark (Milojević et al., 2012). More studies have focused on the effects of light spectra and photoperiod. Red light, in particular, promoted somatic embryogenesis in various plant species. Under red light, the embryonic callus of Rosa chinensis Jacq. produced more somatic embryos (Chen et al., 2014). This was because the callus under red light turned reddish-brown and retained its ability to continuously generate embryos, while the callus under white light hardened and lost its embryogenic potential during subculture. Red light enhances cytokinin levels, maintaining hormone balance and promoting somatic embryo induction. Under red light, the somatic embryo induction rate of Dactylorhiza umberosa protocorm explants reached 95%, with 25 primary embryos formed (Naderi Boldaji et al., 2023). Among all spectra, the explant seeds of Ajuga bracteosa under red light exhibited the highest DPPH-radical scavenging activity, reaching 92.86% (Rukh et al., 2019). Under red light, auxin production increased and redox balance was maintained in the shoots of Begonia × tuberhybrida Voss and the hypocotyls of Gossypium hirsutum L., which supported the preservation of embryonic callus and promoted somatic embryo formation (Van The Vinh et al., 2023; Yu et al., 2019). Similarly, leaf explants of Chrysanthemum showed higher somatic embryo induction rates under red light (Hesami et al., 2019).

In addition to red light, it has been observed that the combination of red light with other wavelengths also promotes somatic embryogenesis. Under mixed red and blue light, root explants of Peucedanum japonicum Thunb. produced the highest number of somatic embryos, with a better effect than red or blue light alone (Chen et al., 2016a). In Panax vietnamensis Ha et Grushv, the highest rate of somatic seedling formation from embryonic callus was achieved under a combination of 60% red and 40% blue light (Nhut et al., 2015). Furthermore, the combination of red and far-red light induced the highest number of somatic embryos in Doritaenopsis inflorescence explants while maintaining a low level of endoreduplication (Park et al., 2010). In addition, under red and blue light, an average of 58 somatic embryos were produced per callus, significantly higher than the 23 embryos generated under fluorescent light (Heringer et al., 2017). Proteomic analysis of callus treated with different light spectra revealed a 23-fold increase in the expression of the methyltransferase PROBABLE METHYLTRANSFERASE 19-LIKE (pmt19-like). These results suggest that protein methylation also plays a role in the response to mixed light spectra.

Blue, green, far-red, and white light also influence somatic embryogenesis in plant species. In A. bracteosa, leaf explants were unable to produce somatic embryos under blue light, likely due to an increase in phenolic compounds that inhibited the differentiation of embryonic callus into somatic embryos (Rukh et al., 2019). Blue light promoted the maturation of somatic embryogenesis in radiata pine, and the plant height of somatic embryo plants was significantly increased after blue light treatment (Castander-Olarieta et al., 2023). Both green and far-red light inhibited the formation of embryonic callus in Dianthus caryophyllus (Aalifar et al., 2019). The embryonic callus of Abies nordmanniana produced the highest number of somatic embryos under white light compared to blue and far-red light (Nawrot-Chorabik, 2016). Proteomic analysis revealed increased abundance of proteins associated with energy production, such as ALCOHOL DEHYDROGENASE 1 (ADH1), GLYCERALDEHYDE-3-PHOSPHATE DEHYDROGENASE (GAPDH), and TRIOSE PHOSPHATE ISOMERASE (TPI), as well as proteins related to the cell wall, including PEPTIDOGLYCAN (PG) and GERMIN-LIKE PROTEINS (GLPs) (Almeida et al., 2019). White light promoted somatic embryogenesis in Carica papaya L. by affecting processes such as energy production and cell wall synthesis (Almeida et al., 2019). In summary, light spectra affect the efficiency of somatic embryogenesis in plants primarily by modulating hormone levels, redox balance, phenolic production, and cell division.

Photoperiod influences the induction of somatic embryogenesis (Table 2). Many plant explants regenerate more somatic embryos in darkness. Leaves of Rhynchostylis gigantea incubated in darkness for 3 weeks produced more somatic embryos compared to those cultivated under a 16/8-h photoperiod, with induction rates of 93.8% and 77.1%, respectively (Rianawati et al., 2023). Leaf explants of Lycium barbarum L. were more easily induced to form embryonic callus and somatic embryos when cultured in darkness for 5 weeks (Khatri and Joshee, 2024). In Campanula punctata Lam. var. rubriflora, somatic embryos were successfully regenerated from leaf and petiole explants under both darkness for 2 weeks and a 16/8-h photoperiod, with higher efficiency observed in darkness (Sivanesan et al., 2011). Similarly, different photoperiodic treatments, ranging from 24-h light to 24-h darkness, were tested for somatic embryo induction in the embryonic callus of Fragaria sp. The results showed that 24-h darkness was the optimal photoperiod for somatic embryo induction, while exposure to more than 6 h of light per day reduced somatic embryo induction in strawberries (Biswas et al., 2007). A higher number of somatic embryos was also observed under an initial 24-h dark treatment compared to the 16/8-h photoperiod in Eucalyptus globulus and Epipactis veratrifolia (Moradi et al., 2017; Pinto et al., 2008).

Explants of some plant species produce more somatic embryos under photoperiods with longer light durations. For example, the somatic embryo induction rate of Ginkgo biloba was higher under a 14/10-h photoperiod (light/dark) than in darkness, and gibberellic acid (GA3) levels were elevated. RNA-seq data revealed that genes related to photosynthesis and carbon fixation, such as Psb A and Psb C, were significantly upregulated under a 14/10-h photoperiod (Chen et al., 2023). Similarly, under a 16/8-h photoperiod, the somatic embryogenesis induction efficiency of Olea europaea L. seeds reached 45%, which was higher than the 35% observed in darkness. Furthermore, the regeneration rate of adventitious shoots from somatic embryos was only 5% in darkness, significantly lower than the 45% observed under the 16/8-h photoperiod (Mazri et al., 2020). A similar pattern was found in the somatic embryogenesis of Spinacia oleracea L. Genes related to the synthesis of GA3, such as GA20-ox1 and GA3-ox1, were highly expressed under 16/8-h photoperiod, indicating that light regulated somatic embryogenesis by modulating the level of GA3 (Zdravković-Korać et al., 2023). Immature syncytial explants of Pistacia vera L. showed browning and produced fewer somatic embryos when cultured in darkness compared to 16/8-h photoperiod (Ghadirzadeh-Khorzoghi et al., 2019). Additionally, more somatic embryos were induced in Cinnamomum camphora L. and Cyathea delgadii Sternb. at 16/8-h photoperiod compared to darkness (Mikuła et al., 2015; Shi et al., 2009). In summary, photoperiod regulates somatic embryogenesis in plant species by influencing the callus state, photosynthesis, carbon fixation, and gibberellin synthesis.

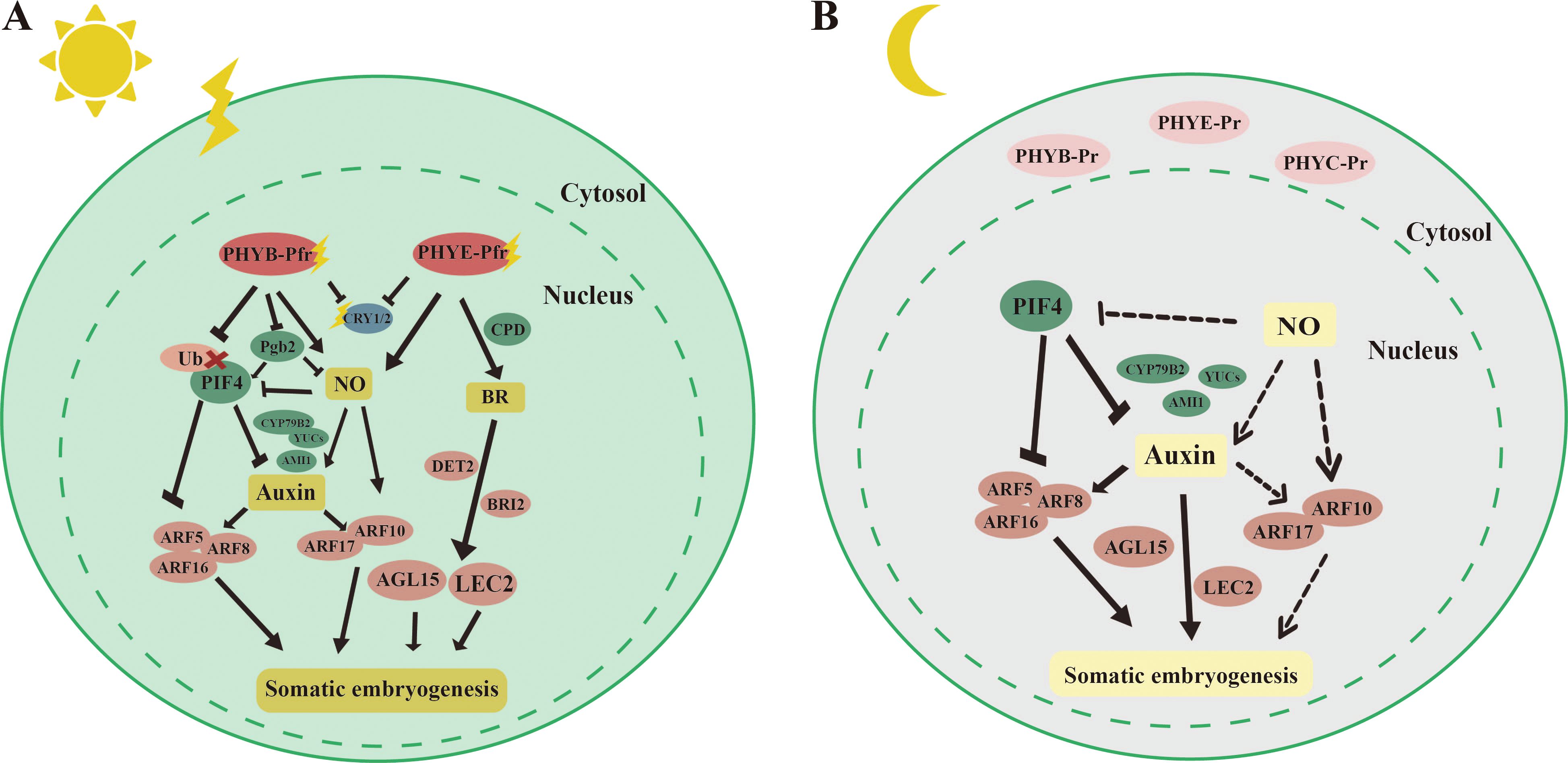

We focus on the molecular mechanisms by which light promotes somatic embryogenesis in plant species (Figure 3). In Arabidopsis, immature zygotic embryos produced more embryonic callus and somatic embryos when exposed to light. Under light, both PHYB and PHYE may inhibit CRY1/2-mediated blue light signaling (Chan and Stasolla, 2023). Mutants of phyB and phyE exhibited significantly lower somatic embryogenesis efficiency compared to the wild type, while phyC mutants showed higher levels of somatic embryogenesis. These results suggest that PHYB and PHYE promote somatic embryogenesis, whereas PHYC inhibits this process (Chan and Stasolla, 2023), highlighting the complexity of light signaling in regulating somatic embryo formation. Under light (Figure 3A), PHYB targeted PIF4 for degradation, alleviating the inhibitory effect of PIF4 on auxin synthesis and signaling (Mira et al., 2023). PHYB and PHYE translocated to the cell nucleus, where they activated the production of downstream nitric oxide (NO), a small gaseous molecule known to be involved in light signaling in C. melo L (Melo et al., 2016). The accumulation of NO increased the auxin maxima at the origin of callus formation in Arabidopsis. This effect was mediated by NO upregulating the expression of auxin synthesis genes such as YUCs and AMI1, as well as the transcription factors ARF10 and ARF17 (Elhiti et al., 2013). Endogenous auxin directly regulated BBM and LEC1/2 to promote somatic embryogenesis (Weijers and Wagner, 2016). The addition of NO was found to elevate the expression of AGL15, although the exact mechanism by which NO regulated AGL15 remained unclear (Chan and Stasolla, 2023). Moreover, PHYE promoted somatic embryogenesis by increasing the content of brassinosteroids (BRs). It achieved this by activating CONSTITUTIVE PHOTOMORPHOGENESIS AND DWARF 3 (CPD3), a gene involved in BR synthesis. BRs, in turn, promoted somatic embryogenesis by enhancing the transcription of downstream genes AGL15 and LEC2. Furthermore, the number of somatic embryos was reduced in det2 and bri2 mutants, key factors in the BR signaling pathway (Chan and Stasolla, 2023). Furthermore, under dark conditions (Figure 3B), the phytochromes PHYB, PHYE, and PHYC remained inactive in the cytoplasm, resulting in low levels of NO in the nucleus, which weakened the promotive effect of NO on somatic embryogenesis. In this context, PIF4, which was active in the nucleus, played a key role in regulating somatic embryogenesis (Cheng et al., 2021a). In pif4 mutants, genes involved in auxin biosynthesis, such as AMI1, YUCs, and Cytochrome P450 (CYP79B2), as well as transcription factors related to auxin signaling, including ARF5/8/16, were upregulated (Mira et al., 2023). Consequently, PIF4 inhibits somatic embryogenesis by repressing both auxin synthesis and signaling pathways.

Figure 3. Molecular mechanisms by which light promotes somatic embryogenesis. [(A), left] Phytochrome Interacting Factor 4 (PIF4) can inhibit somatic embryogenesis by suppressing the expression of auxin synthesis genes Cytochrome P450, family 79, subfamily B, polypeptide 2 (CYP79B2), YUCCAs (YUCs), and AMI1, as well as auxin response factors ARF5, ARF8, and ARF12. Under light, PHYA can target PIF4 for degradation. PHYB and PHYE can activate downstream NO, which in turn upregulates the expression of auxin synthesis genes YUCs and AMI1, as well as auxin response factors ARF10/17, to promote somatic embryogenesis. PHYE can also promote the accumulation of brassinosteroids (BRs) by activating the expression of the BR synthesis gene CONSTITUTIVE PHOTOMORPHOGENESIS AND DWARF 3 (CPD3). BRs, in turn, promote somatic embryogenesis by activating the expression of downstream AGAMOUS-LIKE 15 (AGL15) and LEAFY COTYLEDON 2 (LEC2). [(B), right] Under dark conditions, phytochromes PHYB, PHYE, and PHYC exist in an inactive form in the cytoplasm, while PIF4 is expressed in the nucleus. The level of NO in the nucleus is low. PIF4 can inhibit somatic embryogenesis by suppressing the expression of auxin synthesis genes CYP79B2, YUCs, and AMI1, as well as auxin response factors AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR 5 (ARF5), ARF8, and ARF12. The straight arrow represents activation, the connection of the blunt end represents suppression, parallel lines indicate interactions, and dashed lines indicate non-functionality under certain conditions.

There are several ways to regenerate AR, with this discussion focusing on AR regenerated from cuttings, de novo root organogenesis, and HAR. Plant cuttings involve inserting isolated plant leaves or stem segments into soil, sand, or water, allowing them to root and form a complete plant. De novo root organogenesis refers to the regeneration of AR from callus tissue formed at a damaged site of an isolated explant (Figure 1D). HARs, however, are induced from the hypocotyls of plants under various stress conditions (Figure 1G). A classic model for studying de novo root organogenesis is the formation of AR from isolated Arabidopsis leaves on a medium without added plant growth regulators (Verstraeten et al., 2013). This process is generally divided into three stages: first, isolated explants, such as leaves and sense wound signals; second, specific cells in the explant respond to these signals by synthesizing auxin and transporting it to stem cells (e.g., the formation layer near the wound); and finally, ARs are induced from these stem cells in the presence of auxin (Xu, 2018). HARs are also produced during plant growth and development in response to environmental stresses. For example, under flooding stress, HAR in Cucumis sativus L. improved gas exchange and nutrient uptake, compensating for the loss of primary roots (Pan et al., 2024). When seeds of Arabidopsis were incubated in the dark for 3 days and then transferred to blue light, the hypocotyls induced HAR (Zeng et al., 2022).

During de novo root organogenesis, isolated explants receive transient wound signals mediated by H2O2, ROS, JA, and ethylene (Figure 1D) (Liu W. et al., 2022; Yuan et al., 2024). These signals triggered auxin synthesis and accumulation at specific sites in Arabidopsis, with auxin then transported to the vicinity of the wound (Zhang et al., 2019). Auxin gradually accumulated in the stem cells of the vascular cambium, preparing for subsequent AR regeneration. At the wound site, auxin activated the expression of WOX11, which signified a shift in cell fate and marked the initiation of root primordium formation (Liu et al., 2014). WOX11 formed a complex with ARF6/8, which in turn activated the expression of downstream genes such as LBD16 and RGF1INSENSITIVE 1 (RGI1) (Hu and Xu, 2016; Zhang et al., 2023). Simultaneously, WOX11, along with PLT3/5/7, activated the expression of WOX5. PLT3/5/7 also promoted the expression of PLT1/2, which facilitated cell division and the formation of the root meristem (Liu J. et al., 2022; Xu, 2018). The formation of HAR also requires auxin involvement. ARF7/19, which were implicated in lateral root (LR) formation, were similarly involved in HAR formation (Lee et al., 2019). Additionally, ARF6/8/17 and the auxin signaling components TIR1/AFB2 (AUXIN-SIGNALING F-BOX 2) were key regulators in HAR formation (Gutierrez et al., 2012, 2009; Lakehal et al., 2019; Sorin et al., 2005).

Light intensity plays a significant role in de novo root organogenesis (Table 3). Studies have shown that in Arabidopsis, during AR regeneration from cotyledons, increasing light intensity significantly reduced AR formation efficiency (Blair Nameth et al., 2018). Under higher light intensity, the levels of ROS increased, while the content of the photoprotective pigment zeaxanthin decreased in the explants. This imbalance led to photo-oxidative damage, which further impaired AR regeneration. In Prunus serotina, AR regeneration from axillary buds was studied under five light-intensity gradients ranging from 0 to 833 μmol·m−2·s−1. Results indicated a negative correlation between light intensity and AR formation, with the highest number of ARs observed at light intensities of 0 and 70 μmol·m−2·s−1 (Fuernkranz et al., 1990). Similarly, cuttings of Pisum sativum formed more ARs under 16 W·m−2 (31.37 μmol·m−2·s−1) than under 38 W·m−2 (74.51 μmol·m−2·s−1) (Hansen, 1975). Overall, higher light intensity inhibited de novo root organogenesis by disrupting the redox balance in the explants, leading to photo-oxidative damage. In contrast, light enhanced HAR formation in Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn. (Cheng et al., 2020). HARs in seedlings were induced by light, with faster formation observed as light intensity increased. RNA-seq analysis revealed that genes related to auxin (IAA) synthesis and carbohydrate metabolism were highly expressed under high light intensity, suggesting that light promotes HAR formation by influencing both auxin synthesis and photosynthesis (Cheng et al., 2020).

Light spectra significantly influence AR regeneration (Table 3). Studies have shown that mixed light promotes AR regeneration. For example, compared to red or blue light, Prunus avium L. × Prunus cerasus L. cuttings regenerated more ARs and produced longer roots under mixed red and blue light, indicating a synergistic effect between the two photoreceptors (Iacona and Muleo, 2010). Similarly, mixed red and blue light enhanced AR formation in Gerbera jamesonii (Lim et al., 2023). Explants under this light combination exhibited the highest photosynthetic rate, internal CO2 concentration, and stomatal conductance, which in turn promoted AR regeneration by improving photosynthetic efficiency and respiration. The addition of violet and green light to red and blue light also promoted AR regeneration in C. lanceolata cuttings (Xu et al., 2020). Under this mixed light, explants showed the highest levels of chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and total chlorophyll, along with improved maximum quantum yield of PSII (Fv/Fm), photochemical quenching coefficient (qp), and relative electron transport rate in PSII (ETRII). Stepwise regression analysis revealed significant correlations between Fv/Fm, qp, ETRII, and AR formation. Furthermore, the addition of NPA reduced AR formation in Chrysanthemum cuttings (Christiaens et al., 2019), but lower ratios of red to far-red light partially rescued this inhibitory effect, suggesting that a mix of red and far-red light promotes AR regeneration by influencing auxin polar transport.

Red and blue light have significant effects on AR formation. Red light promoted AR regeneration in Camellia gymnogyna Chang cuttings (Fu et al., 2023). RNA-seq data revealed that genes highly expressed under red light were enriched in pathways related to auxin and hormone responses, indicating that red light regulates AR regeneration through complex hormonal interactions. In contrast, the exogenous application of JA inhibited AR regeneration in Picea abies (Alallaq et al., 2020). Red light facilitated AR formation by reducing JA accumulation in P. abies cuttings. Additionally, red light affected cell number and size, promoting AR regeneration in isolated hypocotyls of Phaseolus vulgaris L (Fletcher et al., 1965). In Camellia sinensis L. cuttings, blue light increased both the number and length of ARs (Shen et al., 2022). RNA-seq analysis showed that genes related to auxins, such as YUCs, ARFs, AUX1, PIN1, and PIN3, were highly expressed under blue light, suggesting that blue light regulates AR regeneration through auxin synthesis and signaling (Shen et al., 2022). The levels of ABA and trans-zeatin (tZ) were also higher under blue light, indicating that multiple hormones are involved in blue light-mediated AR formation in C. sinensis L. Chrysanthemum cuttings showed the highest number of ARs under blue light compared to white and red light, with LBD1 being significantly more highly expressed under blue light (Gil et al., 2020). Furthermore, blue light facilitated the formation of HARs in Arabidopsis. The photoreceptors CRY1/2 and PHOT1/2 were involved in this process, and mutants of cry1, cry2, phot1, and phot2 exhibited fewer ARs than the wild type (Zeng et al., 2022).

Red and blue light can also inhibit AR formation in some plant species. For example, blue light inhibited AR formation in isolated hypocotyls of P. vulgaris (Fletcher et al., 1965). Red light inhibited AR regeneration in Camellia cuttings, with low expression of PILS7, PIN3, and PIN4 under red light (Shen et al., 2022). Other light wavelengths also affected AR regeneration in plant species. For example, far-red light stimulated the synthesis of auxin and carbohydrates, thereby facilitating AR regeneration in Cannabis sativa L. (Sae-Tang et al., 2024). In Citrullus lanatus, far-red light significantly upregulated auxin-related genes such as IAA11, IAA17, and SAUR20, resulting in the highest number of ARs (Wu et al., 2023). Yellow light increased the number of ARs in P. serotina (Fuernkranz et al., 1990). In summary, light spectra affect AR regeneration primarily by influencing photosynthetic and respiratory efficiency, auxin synthesis and transport, and hormone cross-talk in plant species.

Photoperiod plays an important role in AR regeneration (Table 3). Some plant species tend to produce more ARs under short-day photoperiods. In Arabidopsis, a photoperiodic gradient ranging from 24 hours of light to 24 hours of darkness was tested for HAR regeneration (Li et al., 2021). The results showed that HARs were formed in seedlings grown in darkness for more than 4 days, suggesting that light is not essential for HAR formation. Moreover, seedlings grown in darkness for 4 to 6 days produced more HARs than those grown for longer periods. This observation leads to the hypothesis that light promotes HAR formation by increasing carbon assimilates produced through photosynthesis. In grapevine (Vitis sp.) petiole cuttings, darkness treatment achieved a 100% rooting rate after 20 days, compared to just 10% in the control group under a 16/8-h photoperiod (Yuan et al., 2024). RNA-seq analysis revealed high expression of genes involved in cell division, such as EXPs, CYCDs, and XTHs, as well as auxin influx-related genes like PIN1, PIN3, and PIN5 (Yuan et al., 2024). In Petunia × hybrida, cuttings produced more ARs and had a shorter rooting cycle (from 16 days to 9 days) after 7 days of darkness treatment. Dark treatment resulted in significantly lower levels of soluble sugars and starch in the leaves compared to the 16/8-h photoperiod, suggesting that darkness has promoted carbohydrate allocation to the stem base, providing energy for root development (Klopotek et al., 2010). Darkness also promoted AR regeneration of cuttings compared to a 16/8-h photoperiod in E. globulus and D. caryophyllus (Agulló-Antón et al., 2011; Fett-Neto et al., 2001).

Additionally, some plant species are better suited to produce ARs under long-day photoperiods. For example, cuttings of Corylus avellana L. produced more ARs under a 16/8-h photoperiod. During rooting, leaf photosynthesis provides carbohydrates necessary for AR formation (Tombesi et al., 2015). In C. lanceolata, three photoperiods—8/16 h (light/dark), 16/8 h (light/dark), and 24 h of light—were tested for AR regeneration (Xu et al., 2020). The results showed that explants produce the highest number of ARs at a 16/8-h photoperiod and the longest roots, along with the highest chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and total chlorophyll content. In Betula pendula, stem segments under a 16/8-h photoperiod reached 100% rooting compared to 75% in darkness (Wynne and McDonald, 2002). Similarly, under a 16/8-h photoperiod, hypocotyl explants of L. usitatissimum L. produced more ARs (Siegień et al., 2013). Overall, photoperiod affects the AR formation of plant species primarily by influencing photosynthesis, carbohydrate partitioning, cell division, and auxin transport.

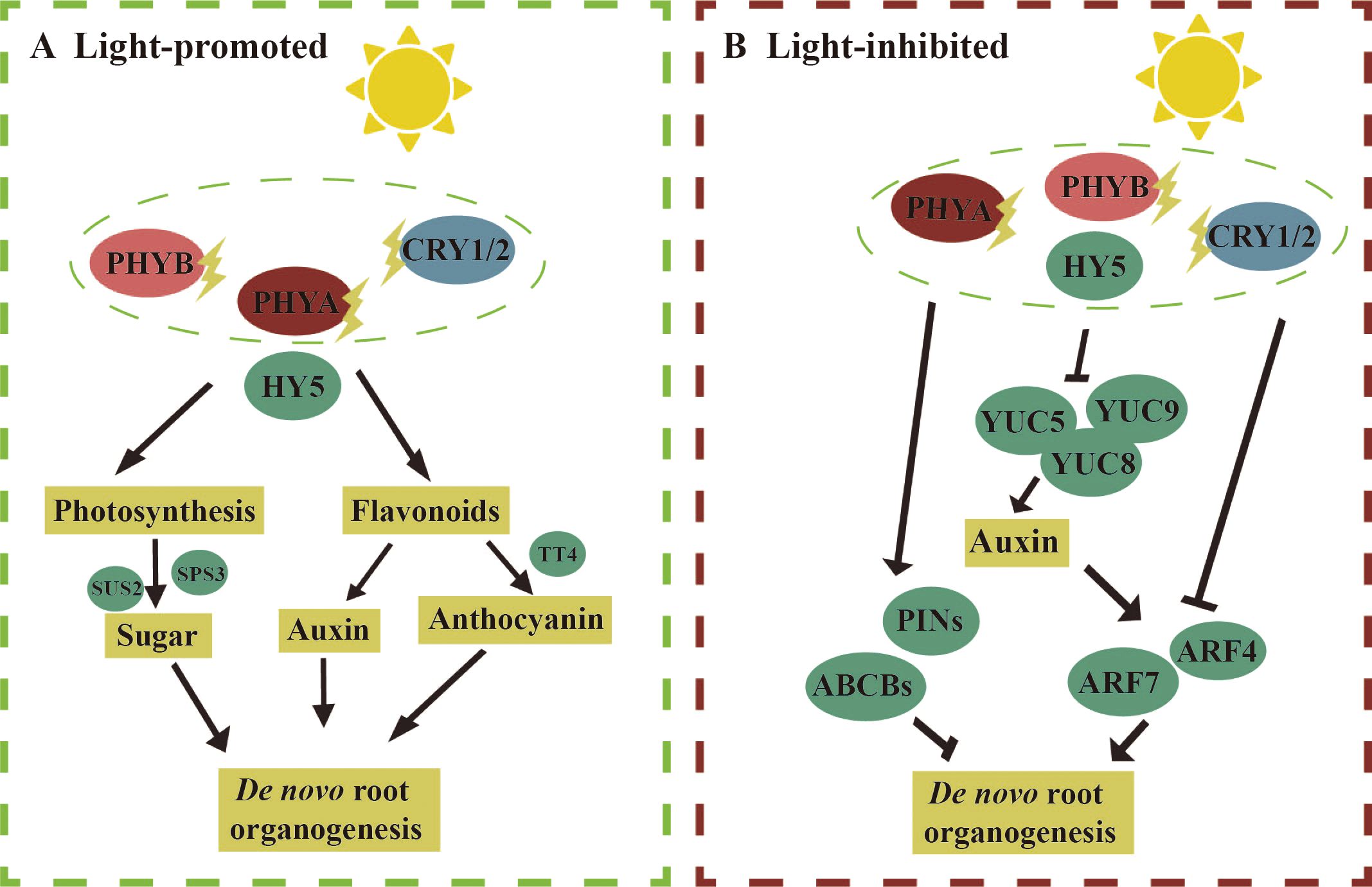

The pathways through which light regulates the regeneration of AR are complex. Here, we first discuss the molecular mechanisms by which light promotes and inhibits de novo root organogenesis (Figure 4). We then summarize the potential molecular mechanisms by which light inhibits HAR (Figure 5). To date, fewer studies have focused on the molecular mechanisms by which light promotes de novo root organogenesis. Light may contribute to AR formation through the synthesis of compounds such as sucrose, anthocyanins, and flavonoids (Figure 4A). Studies have shown that sucrose concentrations ranging from 0.5% to 2.0% were the most effective in inducing adventitious root formation in Arabidopsis seedlings (Takahashi et al., 2003). In grapevine (Vitis sp.) petiole cuttings, ARs were produced more effectively under a 16/8-h photoperiod than in darkness. Under this photoperiod, the expression of genes involved in sucrose synthesis, including SUCROSE SYNTHASE 2 (SUS2) and SUCROSE PHOSPHATE SYNTHASE 3 (SPS3), was elevated, suggesting that photosynthesis promotes AR regeneration in grapevine (Yuan et al., 2024). Light also promotes AR regeneration by regulating anthocyanin content. In Arabidopsis, the cotyledons produced more anthocyanin under light, and the regeneration efficiency of AR was significantly lower in tt4 mutants (which have reduced anthocyanin levels) compared to the wild type (Nameth et al., 2018). Furthermore, flavonoids, which may be involved in auxin transport, have been implicated in AR formation in Arabidopsis (Sukumar, 2010). Under a 16/8-h photoperiod, genes involved in flavonoid synthesis, such as CHALCONE SYNTHASE (CHS) and FLAVANONE 3-HYDROXYLASE (F3H), were upregulated in grapevine (Yuan et al., 2024). However, the precise mechanisms by which these metabolites influence de novo root organogenesis remain to be explored in greater detail.

Figure 4. Molecular mechanism of light regulation of de novo root organogenesis. (A, left) Light promotes de novo root organogenesis: under light conditions, the expression levels of genes involved in sucrose synthesis, such as Sucralose Synthase 2 (SUS2) and Sucralose Phosphate Synthase 3 (SPS3), are elevated in grapevine petioles, leading to an increase in adventitious root regeneration. In Arabidopsis, the regeneration of adventitious roots is reduced in the tt4 mutant, which is deficient in anthocyanin synthesis, under light conditions. Flavonoids synthesized under light may regulate adventitious root de novo regeneration by modulating auxin transport. (B, right) Light inhibits de novo root organogenesis: under light conditions, the addition of NPA can promote de novo root regeneration, suggesting that light may inhibit adventitious root formation by regulating auxin transport proteins such as PIN-FORMED (PIN) and ATP-Binding Cassette B (ABCBs). The expression levels of auxin synthesis genes YUC5/8/9 are reduced under light, and the expression of ARF4/7, involved in auxin signal transduction, is also lowered, indicating that light inhibits de novo root regeneration by regulating both auxin synthesis and signaling. The straight arrow represents activation, the connection of the blunt end represents suppression, and parallel lines indicate interactions.

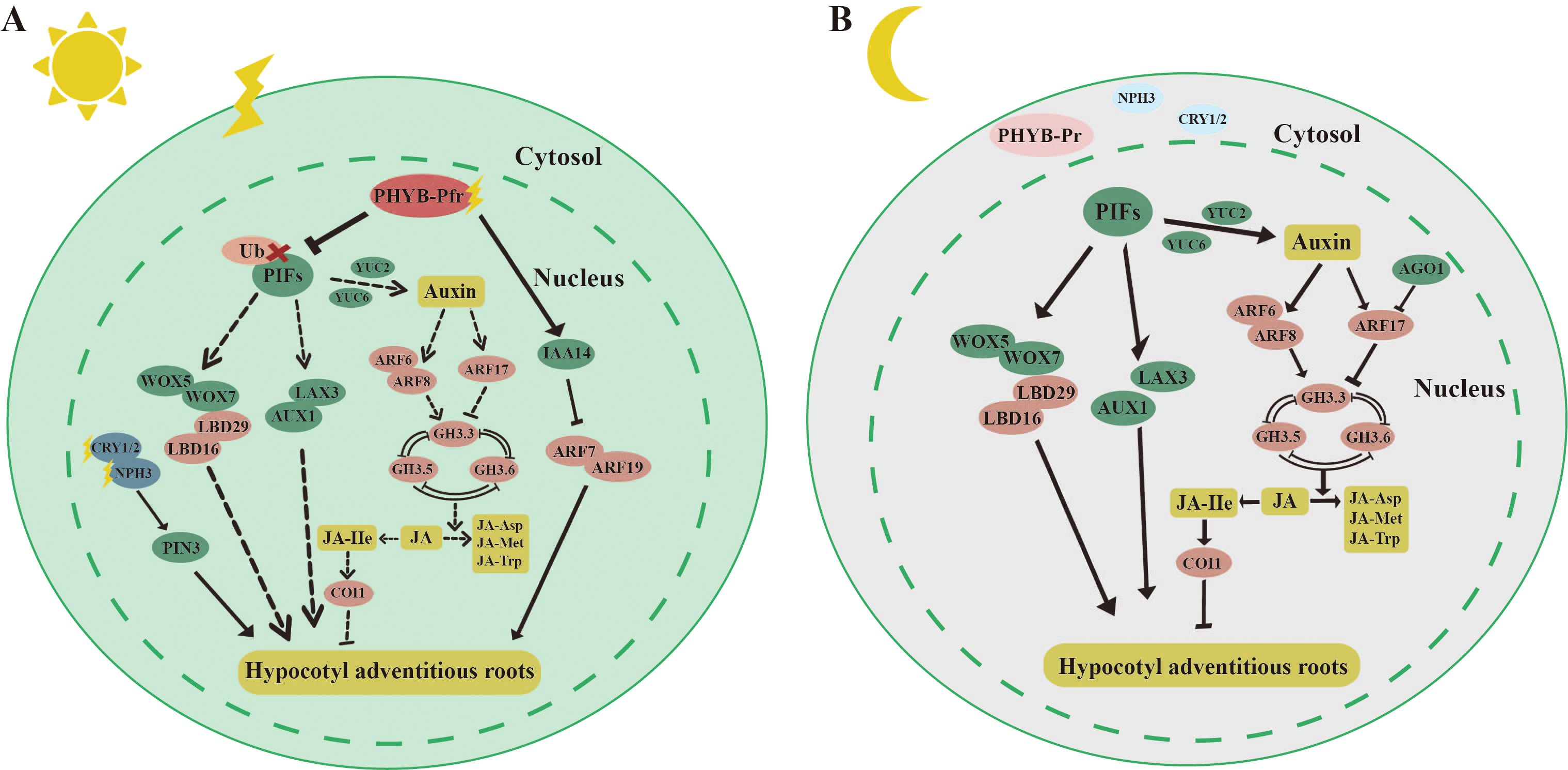

Figure 5. Molecular mechanisms by which light inhibits hypocotyl adventitious root (HAR). (A) light Under light, PHYB can target and degrade PIF4, thereby inhibiting PIF4’s suppressive effect on HAR formation. PHYB can also stabilize INDOLE-3-ACETIC ACID 14 (IAA14) through protein interactions, which lowers the expression of AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR 7/19 (ARF7/19) and subsequently inhibits HAR formation. Blue light receptors CRY1/2, PHOTOTROPIN 1/2 (PHOT1/2), and NON-PHOTOTROPIC HYPOCOTYL 3 (NPH3) also promote the formation of Arabidopsis HARs by enhancing the expression of the auxin transport protein PIN3. (B) Under dark, PHYB-Pr exists in the inactive form in the cytoplasm, and PIFs can directly regulate key transcription factors such as LATERAL ORGAN BOUNDARY DOMAIN 16/29 (LBD16/29) and USCHEL-RELATED HOMEOBOX (WOX5/7), thereby promoting HAR formation. PIFs can also directly bind to the promoters of genes involved in auxin synthesis, such as YUC2/6, to promote HAR formation by synthesizing more auxin. Auxin response factors ARF6 and ARF8 can respectively upregulate and downregulate the expression of GRETCHEN HAGEN 3.3 (GH3.3), GH3.5, and GH3.6 to promote HAR formation. GH3.3, GH3.5, and GH3.6 reduce the active form of jasmonic acid-lle (JA-lle) by promoting the conversion of jasmonic acid (JA) to JA-Met and JA-Asp, thereby reducing the inhibitory effect of JA on HAR through CORONATINE-INSENSITIVE 1 (COI1) regulation. The straight arrow represents activation, the connection of the blunt end represents suppression, parallel lines indicate interactions, and dashed lines indicate non-functionality under certain conditions.

Next, we discuss the molecular mechanisms by which light inhibits de novo root organogenesis (Figure 4B). Under light, photoreceptors perceive light signals through photosensitive pigments such as PHYA, CRY1/2, and PHOT1/2 (Yun et al., 2023). In Arabidopsis, the phyA mutant exhibited higher efficiency of de novo root organogenesis compared to the wild type (Blair Nameth et al., 2018). After filtering blue light using acetate filters, cotyledon explants of Arabidopsis produced more ARs, suggesting that blue light may inhibit AR formation. Photoreceptors subsequently transmit these signals to downstream light-responsive factors, including COP1 and HY5, which regulate auxin pathways and thereby influence de novo root organogenesis. The addition of NPA under light enhanced AR regeneration, suggesting that light inhibits AR formation by modulating auxin transport (Blair Nameth et al., 2018). In particular, the efflux of auxin inhibited AR regeneration. Furthermore, the expression of YUC5/8/9, enzymes involved in auxin synthesis, was higher in leaf explants in darkness compared to a 16/8-h photoperiod (Chen et al., 2016b). A reduction in the expression of ARF4/7, which acted upstream of LBD16 and promoted AR formation in peach, was also observed during de novo root organogenesis in grapevine petioles in response to light exposure (Yuan et al., 2024). These findings suggest that light inhibits de novo root organogenesis by regulating auxin synthesis, transport, and signaling. The specific roles of these key factors require further investigation.

Light has also been shown to inhibit the formation of HAR (Figure 5). Under light, the active form of PHYB-Pfr interacted with PIFs in the cell nucleus, leading to the phosphorylation of PIF proteins (Bauer et al., 2004) (Figure 5A). This interaction inhibited the promotion of HAR by PIFs (Li et al., 2022b). The mechanisms underlying HAR and LR formation were similar. In the case of LR, IAA14 and ARF7/19 played key roles. ARF7/19 positively regulated LR formation, whereas IAA14 inhibited this process by suppressing the expression of ARF7/19 (Goh et al., 2012). PHYB stabilized IAA14 through protein interactions, thereby inhibiting HAR formation by decreasing the transcriptional activity of ARF7/19 (Li et al., 2021). Additionally, blue light receptors, including CRY1/2, PHOT1/2, and NON-PHOTOTROPIC HYPOCOTYL 3 (NPH3), were involved in regulating HAR under light. NPH3 likely further regulated HAR formation in Arabidopsis by modulating auxin transport through the PIN3 protein (Zeng et al., 2022; Zhai et al., 2021). Under dark, PHYB-Pr existed in the cell cytoplasm, and the localization of PIFs in the nucleus directly regulated auxin synthesis and transport (Figure 5B). PIFs bound to the promoters of the auxin transporters AUXIN 1 (AUX1) and LIKE-AUX 3 (LAX3), thereby promoting the inward flow of auxin and enhancing HAR regeneration. Furthermore, PIFs directly regulated key transcription factors such as LBD16/29 and WOX5/7, which were involved in the direct promotion of HAR formation (Li et al., 2022b). PIFs are also bound to the promoters of YUC2/6, genes involved in auxin synthesis, to increase auxin production, thereby further promoting HAR formation. However, PIFs did not regulate the YUC5/8/9, which were highly expressed in the dark, suggesting the involvement of other light signaling factors that mediate auxin synthesis through activation of YUC5/8/9. Auxin may also indirectly regulate HAR formation by modulating JA signaling. Three auxin early response genes, GRETCHEN HAGEN 3.3 (GH3.3), GH3.5, and GH3.6, were positively and redundantly involved in HAR regeneration (Gutierrez et al., 2012). Three proteins interacted with each other (Sorin et al., 2006). The active form of jasmonic acid, jasmonic acid isoleucine (JA-Ile), inhibited HAR formation via the CORONATINE-INSENSITIVE 1 (COI1) signaling pathway (Gutierrez et al., 2012). GH3.3, GH3.5, and GH3.6 reduced JA-Ile levels by promoting the binding of JAs to amino acids such as JA-Met and JA-Asp. ARF6/8/17, located upstream of GH3.3, GH3.5, and GH3.6, regulated their expression, with ARF6/8 positively and ARF17 negatively regulating GH3 gene expression (Gutierrez et al., 2012). Auxin upregulated the expression of GH3.3, GH3.5, and GH3.6 by activating ARF6/8, thereby promoting HAR regeneration through the degradation of JA (Gutierrez et al., 2012). Moreover, ARGONAUTE 1 (AGO1) suppressed the expression of ARF17 (Sorin et al., 2005).

Plant cell totipotency is considered one of the 25 most important scientific challenges (Kennedy, 2005), as it enables plant species to undergo tissue repair and organ regeneration in response to injury or stress. In addition to its critical role in maintaining normal physiological functions, plant regeneration forms the basis for the asexual propagation of superior varieties and underpins various biotechnological applications, including genetic transformation and CRISPR-Cas9 (Valencia-Lozano et al., 2024; Deltcheva et al.,2011). Therefore, understanding the factors that influence plant regeneration is essential. Key factors such as the type of explants, culture medium, plant growth regulators, and light conditions all impact the efficiency of plant regeneration (Long et al., 2022). Among these, light conditions have been shown to significantly influence regeneration outcomes. By optimizing light conditions, plant regeneration efficiency can be enhanced. This paper reviews the effects of light intensity, light spectra, and photoperiod on de novo shoot organogenesis, somatic embryogenesis, AR formation, and related molecular mechanisms and regulatory networks. These insights contribute to a deeper understanding of the role of light in plant regeneration.

Although significant progress has been made in studying the effects of light on plant regeneration, research has mainly focused on a limited number of plant species. Due to species-specific variations, different species or even different genotypes within the same species can exhibit vastly different responses to light signals. The complex regulation of plant regeneration by light may reflect the evolutionary adaptations of plants, from bryophytes to xerophytes. As a result, the mechanisms underlying light-induced plant regeneration have become increasingly diverse, enabling plants to successfully regenerate even in complex environments. To gain a more comprehensive understanding of how light influences plant regeneration, it is essential to explore the responses of various plant species to light signals. This approach can provide valuable insights and specific references for studying light-regulated regeneration in non-model plants.

Understanding the molecular mechanisms through which light influences plant regeneration is crucial for optimizing the application of light signaling. Currently, most studies on light-induced plant regeneration focus on the model plant Arabidopsis. Based on the extensive use of Arabidopsis mutants and in-depth studies of light signaling factors, the key light signaling factors involved in regulating plant regeneration have been largely identified. However, through which target genes or transcription factors do light-responsive factors regulate plant regeneration? Which regulatory pathways are involved, and do they interact with each other? Are post-transcriptional regulation and epigenetic modifications involved in light-regulated plant regeneration? The molecular mechanisms of light-regulated regeneration in Arabidopsis may be conserved in other species, but differences likely exist. These questions warrant further investigation. Additionally, the mechanisms by which light regulates regeneration in woody plants may differ from those in the herbaceous model Arabidopsis. Therefore, it is also crucial to explore the regulatory mechanisms of light in the regeneration of woody plants.

With the rapid advancement of biotechnology, techniques such as CRISPR-Cas9, single-cell multi-omics, spatial genomics, and other technologies have been increasingly applied in plant research. CRISPR-Cas9, in particular, allows for precise gene knockout, insertion, mutation, and modification, making it a powerful tool for improving plant traits and investigating the roles of key factors in light-regulated plant regeneration. Plant regeneration is a complex biological process involving cell and tissue fate transitions, as well as regulation at multiple genetic levels. The emergence of single-cell genomics, genomic data of individual cells, delineation of cellular taxa based on clustering of cells, proposed temporal analysis, and cell trajectory analysis allows us to recognize cell fate transitions during plant regeneration at the cellular level and to gain a deeper understanding of the process of plant regeneration. Additionally, spatial histology, based on tissue sectioning, allows for the observation of individual cell positions and functional states within tissues at a spatial level. For instance, in the regeneration of de novo shoot organogenesis, tissue-level changes, as well as associated mRNA and protein alterations throughout the stages—from explant to callus formation to adventitious shoot development—can be captured. These emerging technologies hold great potential for enhancing our understanding of how light influences plant regeneration and will likely play a pivotal role in future research in this area.

JH: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YaL: Writing – review & editing. YZ: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. YS: Writing – review & editing. YuL: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. ZP: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the STI 2030‐Major Projects (2023ZD04056), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2023M740277), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32171769).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Aalifar, M., Arab, M., Aliniaeifard, S., Dianati, S., Zare Mehrjerdi, M., Limpens, E., et al. (2019). Embryogenesis efficiency and genetic stability of Dianthus caryophyllus embryos in response to different light spectra and plant growth regulators. Plant Cell Tiss Organ Cult. 139, 479–492. doi: 10.1007/s11240-019-01684-6

Adil, M., Ren, X., Jeong, B. R. (2019). Light elicited growth, antioxidant enzymes activities and production of medicinal compounds in callus culture of Cnidium officinale Makino. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B. 196, 111509. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2019.05.006

Agulló-Antón, M.Á., Sánchez-Bravo, J., Acosta, M., Druege, U. (2011). Auxins or Sugars: what makes the difference in the adventitious rooting of stored carnation cuttings? J. Plant Growth Regul. 30, 100–113. doi: 10.1007/s00344-010-9174-8

Alallaq, S., Ranjan, A., Brunoni, F., Novák, O., Lakehal, A., Bellini, C. (2020). Red light controls adventitious root regeneration by modulating hormone homeostasis in Picea abies Seedlings. Front. Plant Sci. 11. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.586140

Almeida, F. A., Vale, E. M., Reis, R. S., Santa-Catarina, C., Silveira, V. (2019). LED lamps enhance somatic embryo maturation in association with the differential accumulation of proteins in the Carica papaya L. ‘Golden’ embryogenic callus. Plant Physiol. Bioch. 143, 109–118. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2019.08.029

Assou, J., Bethge, H., Wamhoff, D., Winkelmann, T. (2023). Effect of cytokinins and light quality on adventitious shoot regeneration from leaflet explants of peanut (Arachis hypogaea). J. Hortic. Sci. Biotech. 98, 508–525. doi: 10.1080/14620316.2022.2160382

Atta, R., Laurens, L., Boucheron-Dubuisson, E., Guivarc’h, A., Carnero, E., Giraudat-Pautot, V., et al. (2009). Pluripotency of Arabidopsis xylem pericycle underlies shoot regeneration from root and hypocotyl explants grown in vitro. Plant J. 57, 626–644. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03715.x

Bakhshaie, M., Babalar, M., Mirmasoumi, M., Khalighi, A. (2010). Effects of light, sucrose, and cytokinins on somatic embryogenesis in Lilium ledebourii (Baker) Bioss. via transverse thin cell-layer cultures of bulblet microscales. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotech. 85, 491–496. doi: 10.1080/14620316.2010.11512703

Baque, M., Hahn, E.-J., Paek, K.-Y. (2010). Induction mechanism of adventitious root from leaf explants of Morinda citrifolia as affected by auxin and light quality. In Vitro Cell.Dev.Biol.-Plant 46, 71–80. doi: 10.1007/s11627-009-9261-3

Bauer, D., Viczián, A., Kircher, S., Nobis, T., Nitschke, R., Kunkel, T., et al. (2004). Constitutive photomorphogenesis 1 and multiple photoreceptors control degradation of phytochrome interacting factor 3, a transcription factor required for light signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 16, 1433–1445. doi: 10.1105/tpc.021568

Belić, M., Zdravković-Korać, S., Janošević, D., Savić, J., Todorović, S., Banjac, N., et al. (2020). Gibberellins and light synergistically promote somatic embryogenesis from the in vitro apical root sections of spinach. Plant Cell Tiss Organ Cult. 142, 537–548. doi: 10.1007/s11240-020-01878-3

Berckmans, B., Vassileva, V., Schmid, S. P. C., Maes, S., Parizot, B., Naramoto, S., et al. (2011). Auxin-dependent cell cycle reactivation through transcriptional regulation of Arabidopsis E2Fa by lateral organ boundary proteins. Plant Cell. 23, 3671–3683. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.088377

Bhatnagar, A., Singh, S., Khurana, J. P., Burman, N. (2020). HY5-COP1: the central module of light signaling pathway. J. Plant Biochem. Biotechnol. 29, 590–610. doi: 10.1007/s13562-020-00623-3

Biswal, B., Jena, B., Giri, A. K., Acharya, L. (2022). Monochromatic light elicited biomass accumulation, antioxidant activity, and secondary metabolite production in callus culture of Operculina turpethum (L.). Plant Cell Tiss Organ Cult. 149, 123–134. doi: 10.1007/s11240-022-02274-9

Biswas, M. K., Islam, R., Hossain, M. (2007). Somatic embryogenesis in strawberry (Fragaria sp.) through callus culture. Plant Cell Tiss Organ Cult. 90, 49–54. doi: 10.1007/s11240-007-9247-y

Blair Nameth, M., Goron, T. L., Dinka, S. J., Morris, A. D., English, J., Lewis, D., et al. (2018). The initial hours of post-excision light are critical for adventitious root regeneration from Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. cotyledon explants. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol.-Plant 54, 273–290. doi: 10.1007/s11627-017-9880-z

Brand, U., Grünewald, M., Hobe, M., Simon, R. (2002). Regulation of CLV3 expression by two homeobox genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 129, 565–575. doi: 10.1104/pp.001867

Braybrook, S. A., Stone, S. L., Park, S., Bui, A. Q., Le, B. H., Fischer, R. L., et al. (2006). Genes directly regulated by LEAFY COTYLEDON 2 provide insight in-to the control of embryo maturation and somatic embryogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 3468–3473. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511331103

Buechel, S., Leibfried, A., To, J. P. C., Zhao, Z., Andersen, S. U., Kieber, J. J., et al. (2010). Role of A-type ARABIDOPSIS RESPONSE REGULATORS in meri-stem maintenance and regeneration. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 89, 279–284. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2009.11.016

Burritt, D. J., Leung, D. W. M. (2003). Adventitious shoot regeneration from Begonia × erythrophylla petiole sections is developmentally sensitive to light quality. Physiologia Plantarum. 118, 289–296. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3054.2003.00083.x

Caboni, E., Lauri, P., D’Angeli, S. (2000). In vitro plant regeneration from callus of shoot apices in apple shoot culture. Plant Cell Rep. 19, 755–760. doi: 10.1007/s002999900189

Caillot, S., Rosiau, E., Laplace, C., Thomasset, B. (2009). Influence of light intensity and selection scheme on regeneration time of transgenic flax plants. Plant Cell Rep. 28, 359–371. doi: 10.1007/s00299-008-0638-2

Castander-Olarieta, A., Montalbán, I. A., Moncaleán, P. (2023). Multi-strategy ap-proach towards optimization of maturation and germination in radiata pine so-matic embryogenesis. Plant Cell Tiss Organ Cult. 153, 173–190. doi: 10.1007/s11240-023-02457-y

Chan, A., Stasolla, C. (2023). Light induction of somatic embryogenesis in Arabidopsis is regulated by PHYTOCHROME E. Plant Physiol. Biotech. 195, 163–169. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2023.01.007

Chen, C.-C., Agrawal, D. C., Lee, M.-R., Lee, R.-J., Kuo, C.-L., Wu, C.-R., et al. (2016a). Influence of LED light spectra on in vitro somatic embryogenesis and LC–MS analysis of chloro-genic acid and rutin in Peucedanum japonicum Thunb.: a medicinal herb. Bot. Stud. 57, 9. doi: 10.1186/s40529-016-0124-z

Chen, J.-R., Wu, L., Hu, B.-W., Yi, X., Liu, R., Deng, Z.-N., et al. (2014). The Influence of plant growth regulators and light quality on somatic embryogenesis in China Rose (Rosa chinensis Jacq.). J. Plant Growth Regul. 33, 295–304. doi: 10.1007/s00344-013-9371-3

Chen, L., Tong, J., Xiao, L., Ruan, Y., Liu, J., Zeng, M., et al. (2016b). YUCCA -mediated auxin biogenesis is required for cell fate transition occurring during de novo root organogenesis in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 67, 4273–4284. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw213

Chen, Y., Hu, Y., Wang, R., Feng, K., Di, J., Feng, T., et al. (2023). Transcriptome and physiological analysis highlight the hormone, phenylpropanoid, and photosynthesis effects on early somatic embryogenesis in Ginkgo biloba. Ind. Crop Prod. 203, 117176. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2023.117176

Chen, Y.-M., Huang, J.-Z., Hou, T.-W., Pan, I.-C. (2019). Effects of light intensity and plant growth regulators on callus proliferation and shoot regeneration in the ornamental succulent Haworthia. Bot. Stud. 60, 10. doi: 10.1186/s40529-019-0257-y