94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Plant Sci., 28 May 2024

Sec. Plant Bioinformatics

Volume 15 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2024.1403220

This article is part of the Research TopicMulti-Omics, Genetic Evolution and Crop DomesticationView all 17 articles

Zhen Wang1

Zhen Wang1 Panpan Wang1

Panpan Wang1 Huiyan Cao1

Huiyan Cao1 Meiqi Liu1

Meiqi Liu1 Lingyang Kong1

Lingyang Kong1 Honggang Wang2

Honggang Wang2 Weichao Ren1*

Weichao Ren1* Qifeng Fu3*

Qifeng Fu3* Wei Ma1,3*

Wei Ma1,3*The Basic Leucine Zipper (bZIP) transcription factors (TFs) family is among of the largest and most diverse gene families found in plant species, and members of the bZIP TFs family perform important functions in plant developmental processes and stress response. To date, bZIP genes in Platycodon grandiflorus have not been characterized. In this work, a number of 47 PgbZIP genes were identified from the genome of P. grandiflorus, divided into 11 subfamilies. The distribution of these PgbZIP genes on the chromosome and gene replication events were analyzed. The motif, gene structure, cis-elements, and collinearity relationships of the PgbZIP genes were simultaneously analyzed. In addition, gene expression pattern analysis identified ten candidate genes involved in the developmental process of different tissue parts of P. grandiflorus. Among them, Four genes (PgbZIP5, PgbZIP21, PgbZIP25 and PgbZIP28) responded to drought and salt stress, which may have potential biological roles in P. grandiflorus development under salt and drought stress. Four hub genes (PgbZIP13, PgbZIP30, PgbZIP32 and PgbZIP45) mined in correlation network analysis, suggesting that these PgbZIP genes may form a regulatory network with other transcription factors to participate in regulating the growth and development of P. grandiflorus. This study provides new insights regarding the understanding of the comprehensive characterization of the PgbZIP TFs for further exploration of the functions of growth and developmental regulation in P. grandiflorus and the mechanisms for coping with abiotic stress response.

Platycodon grandiflorus (Jacq.) A. DC. is a perennial herbal in the Platycodon genus of the Campanulaceae family (Ma et al., 2016). Mainly from the northeastern, northern, central and eastern provinces of China, it is also found in the Russian Far East and the Korean Peninsula (Zhang et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2015). P. grandiflors has high medicinal and edible value, and is a homologous category of medicine and food. At the same time, it also has high ornamental value (Ji et al., 2020). P. grandiflorus is rich in natural chemical products. In the past many years, at least 100 compounds have been isolated, including steroidal saponins, sterols, flavonoids and phenolic acids. Modern pharmacological studies have shown that the pharmacological components of P. grandiflorus are triterpenoid saponins, and Platycodon D possesses several medicinal activities such as anti-obesity, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antitumor and immune regulatory activities (Zhang et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022). The growth and development of P. grandiflorus is a delicate process, and the study of molecular mechanisms of resistance to abiotic stress is an important production guide in the face of increasingly challenging natural environments. Transcription factors (TFs) are key regulatory proteins with DNA binding domains that can inhibit or activate gene expression (Tian et al., 2023). The YABBY (Kong et al., 2023), WRKY (Jing et al., 2022) and Trihelix (Liu et al., 2023) TF families have been proven to play a role in the response of P. grandiflorus to abiotic stress. However, this is only a drop in the ocean of a complex transcriptional regulatory network.

The Basic Leucine Zipper (bZIP) TFs are among of the most widely families of TFs in eukaryotes (Zhao et al., 2016b). The plant bZIP protein has two highly conserved domains composed of 60–80 amino acids: the basic region and leucine zipper region (Nijhawan et al., 2008). bZIP transcription factors mainly regulate tissue and organ development in plants, including seed germination and maturation, embryonic development, flowering, and light morphogenesis (Gangappa and Botto, 2016). Earlier research has indicated that the bZIP gene family ABF1 gene in Arabidopsis thaliana regulate seed dormancy and germination, affecting winter A. thaliana growth (Sharma et al., 2011). Litchi chinensis LcbZIP1, LcbZIP4, LcbZIP7, LcbZIP21 and LcbZIP28 may be involved in the regulation of senescence during postharvest storage of fruit (Hou et al., 2022). Meanwhile, the bZIP family also performs essential functions in responding to abiotic stress and regulating secondary metabolites. Overexpression of Capsicum annuum CabZIP25 in A. thaliana can improve tolerance to salt stress (Gai et al., 2020). Similarly, TabZIP15 can also improve salt tolerance in Triticum aestivum (Bi et al., 2021). Overexpression of Phyllostachys edulis PhebZIP47 in A. thaliana and Oryza sativa can increase the drought resistance of plants at the adult stages (Lan et al., 2023). In transgenic Artemisia annua overexpressing AabZIP9, the biosynthetic accumulation of artemisinin, dihydroartemisinic acid, and artemisinic acid was significantly increased (Shen et al., 2019). Reports on bZIP genes have now been carried out in a wide variety plants, However, it is unclear whether bZIP genes are participating in the growth process of P. grandiflorus and their role in responding to abiotic stress. At present, the chromosome-scale genome of P. grandiflorus has been released (Lee et al., 2023). Therefore, explore the possible role of bZIP TFs in the growth, development, and abiotic stress of P. grandiflorus on the basis of genome-wide and transcriptome data is of great significance.

In this study, we carried out a genome-wide identification and characterization of the bZIP gene family of P. grandiflorus and comprehensively analyzed the physicochemical properties, phylogeny, synteny relationship, gene structure and cis-elements. In addition, by mine the expression patterns of PgbZIP genes in eight tissues and constructing correlation networks, it was determined that they may interact with different genes and participate in multiple biological processes together. More importantly, the expression of PgbZIP genes during abiotic stress was analyzed by RT-qPCR, which indicated that some PgbZIP genes were responsive to salt and drought stress. The present study was conducted to provide a reference for the screening of bZIP candidate genes involved in regulating the developmental process of P. grandiflorus and in resistance to drought and salinity stress.

The plant material P. grandiflorus was cultivated from the Medicinal Botanical Garden of Heilongjiang University of Chinese Medicine (HLJUCM), Harbin, China. There are two types of plant materials used in this study, one of which was the roots, stems, leaves and flowers of 1-year-old P. grandiflorus in the normal growth state without treatment. The other was a three-month-old P. grandiflorus seedling grown in a simulated abiotic stress environment. P. grandiflorus seedlings were watered with 200 mmol/L NaCl and 20% PEG6000 (Coolaber Science & Technology, Beijing, China) to simulate drought and salt stress, respectively, and roots were collected at 48 h. Following the sample process, all plant components were instantly frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately after sampling and kept in a medical refrigerator at -80°C for additional analysis.

The complete genome sequence and annotated file of P. grandiflorus can be downloaded from the Figshare database (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.21511020). TBtools software was used to identify every member of the bZIP TFs in the genome of P. grandiflorus (Chen et al., 2020). TBtools software was used to extract all genes sequences in the P. grandiflorus genome. The hidden Markov model file in the bZIP domain was used as a template to identify each gene and obtain the candidate PgbZIP protein sequence. For validation, the candidate sequences were uploaded to the NCBI CD-search tools and the plant transcription factor database. After removing redundant and structurally incomplete domain sequences, the final PgbZIP protein was obtained. Use the web tool ExPASy ProtParam (https://web.expasy.org/protparam/) to search the molecular weight (MW), isoelectric point, grand average of hydropathicity (GRAVY) of PgbZIP proteins.

The genome annotation file of P. grandiflorus was analyzed and the chromosome location information of PgbZIP gene was obtained, and its corresponding chromosomal physical location was mapped using Tbtools software. The genomic information of Malus domestica (GCF_002114115.1), Cannabis sativa (GCA_900626175.1), Vitis vinifera (GCF_000003745.3), Solanum lycopersicum (GCF_000188115.4) and Oryza_sativa (GCA_001433935.1) were downloaded from the NCBI database. MCScanX software was used to analyze the gene duplication and collinearity of PgbZIP gene family (Wang et al., 2012). The PgbZIP gene replication events were visualized using the TBtools software’s “Advanced Circos” function, and the collinearity relationship between P. grandiflorus and other species was shown using the “Dual Systeny Plot” function.

The TAIR database (https://www.arabidopsis.org/) provided the sequence of the A. thaliana bZIP protein. MEGA X was used to perform multiple sequence alignment of AtbZIP, IibZIP (Jiang et al., 2022) and PgbZIP protein, respectively (Kumar et al., 2018). The phylogenetic tree was constructed by neighbor- joining (NJ) method, and the bootstrap was repeated 1000 times. PgbZIP proteins are divided into different subfamilies based on A. thaliana bZIP proteins (Jakoby et al., 2002).

The PgbZIP gene family was subjected to motif analysis using the Multiple Em for Motif Elicitation website. The parameters were set to Classic mode, and ten motifs were discovered (Bailey et al., 2009). Extract the upstream 2 kb sequence of the PgbZIP family gene using the “GXF Sequences Extract” tool in TBtools software, and then identify and retrieve the cis-elements of the gene family through the PlantCare database (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/) for analysis and comparison (Lescot et al., 2002).

The NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database has the raw transcriptome data for the eight P. grandiflorus tissues that were used in this investigation. These accession numbers are as follows: SER912510-SER912517 (Kim et al., 2020). The expression of every PgbZIP gene used to be quantified in fragments per kilobase of exon model per million mapped fragments (FPKM). All FPKM values have been processed using row scale transformation, and heatmaps were generated using TBtools.

Total RNA was extracted from leaves, roots and stems of 1-year-old P. grandiflorus, drought, and salt stress treated P. grandiflorus seedlings, respectively, using the RNAprep Pure Plant Kit (TIANGEN Biotech Co.,Ltd, Beijing, China). Then, The first strand cDNA was synthesized using MS 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis SuperMix for qPCR (+gDNA wiper) kit (Msunflowers Biotech Co.,Ltd, Beijing, China) reverse transcribed RNA as a template, and finally, qRT-PCR experiments were performed using 2×SYBR Green qPCR Mix (With ROX) kit (Shandong SparkJade Biotechnology Co., Ltd, Shandong, China) kit. qRT-PCR experiments had been carried out the use of an AriaMx real-time PCR system (Agilent Technologies, USA). The PgGAPDH had been used as a reference gene (Ma et al., 2016), and three technical replicates had been set up for each experiment. The relative expression of genes was computed by the 2− ΔΔCT Method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). The Primer3web (version 4.1.0) website (https://primer3.ut.ee/) was used to layout unique primers (Untergasser et al., 2012). GraphPad Prism (v8.0.2) software program was once used to draw the histogram of relative expression of genes, which was once analyzed by t-test.

PlantTFDB was used to identify TFs for the whole genome proteins of P. grandiflorus, and the online database of Pfam was used to annotate the conserved domains of genes. The correlation between transcriptomes was calculated using a Python script primarily based on the Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC) (Zhang et al., 2017). Visualization of correlation network diagrams using Cytoscape (v3.7.1) software (Shannon et al., 2003). The GO (Gene Ontology) and KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) enrichment analysis using the R language package clusterProfiler (Zhang et al., 2017).

After removing redundant and incomplete domain sequences, we finally identified 47 bZIP genes in P.grandiflorus (Supplementary Table 1). In subsequent analyses, we named the genes PgbZIP1 to PgbZIP47 based on their location on the chromosome or contig (from Pg_chr01_03120T to Pg_contig01856_00120T). Then, we analyzed the physicochemical parameters of the PgbZIP protein in detail. The results confirmed that the amino acid (AA) size of the PgbZIP proteins ranged from 132 AA (PgbZIP40) to 704 AA (PgbZIP13). The molecular weight (MW) of the PgbZIP proteins ranged from 14840.52 Da to 75818.79 Da, with an theoretical isoelectric point (pI) of 4.66 (PgbZIP28) to 9.77 (PgbZIP27). The GRAVY values of all PgbZIP proteins were less than 0, suggesting that all PgbZIP proteins may be hydrophilic.

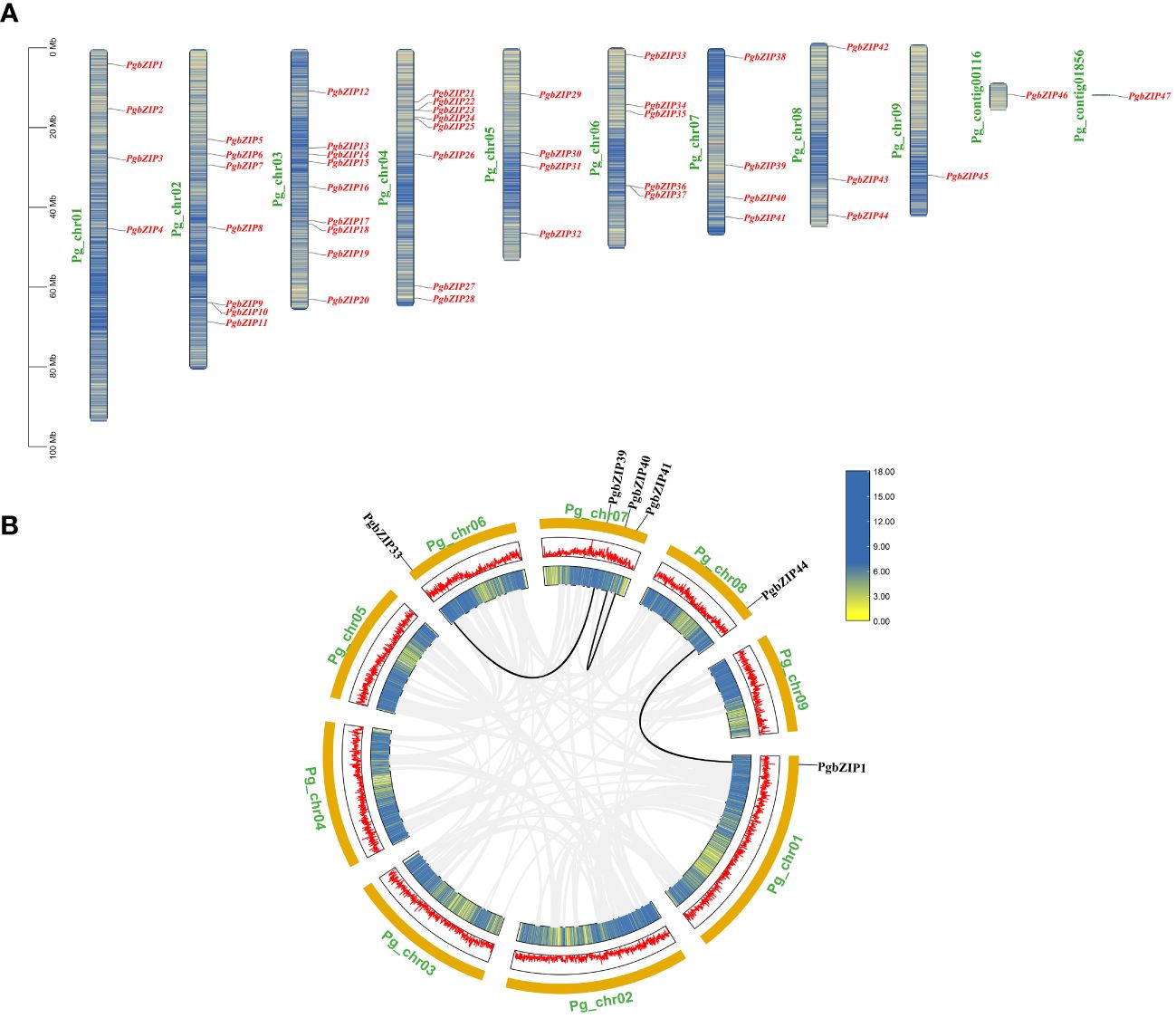

The distribution of PgbZIP genes on the chromosomes of P.grandiflorus did not show any obvious pattern, with 47 PgbZIP genes unevenly distributed on 9 chromosomes and 2 contigs (Figure 1). Chromosome 3 contained the most bZIP genes (9), and chromosome 9, Pg_contig00116 and Pg_contig01856 contained the fewest bZIP genes (only a single gene each). The bZIP genes were distributed on all chromosomes, but none of the genes showed a preferential distribution on a particular chromosome.

Figure 1 The distribution information of PgbZIP genes on chromosomes and gene replication events in the P.grandiflorus. (A) Information on the location of the PgbZIP genes on the P.grandiflorus. (B) Gene duplication events of bZIP genes in P.grandiflorus. Black lines indicate gene segmental duplication events in the PgbZIP gene, and gray lines show that collinear pairs of all P.grandiflorus genes. The yellow lines and red bar indicate the genes density in each chromosome.

Investigations into the gene replication events in P. grandiflorus were conducted to understand the expansion of the PgbZIP genes. Gene duplication within the same chromosome or on different chromosomes, but without one following the other, is considered a segmental duplication event. In the PgbZIP gene family, four PgbZIP gene pairs were generated by segmental duplication. It is worth noting that 1 pair of segmental duplication events (PgbZIP5 and PgbZIP46) is not shown in the Figure 1B, because the PgbZIP46 gene was not mapped to the chromosome and was distributed on the contig.

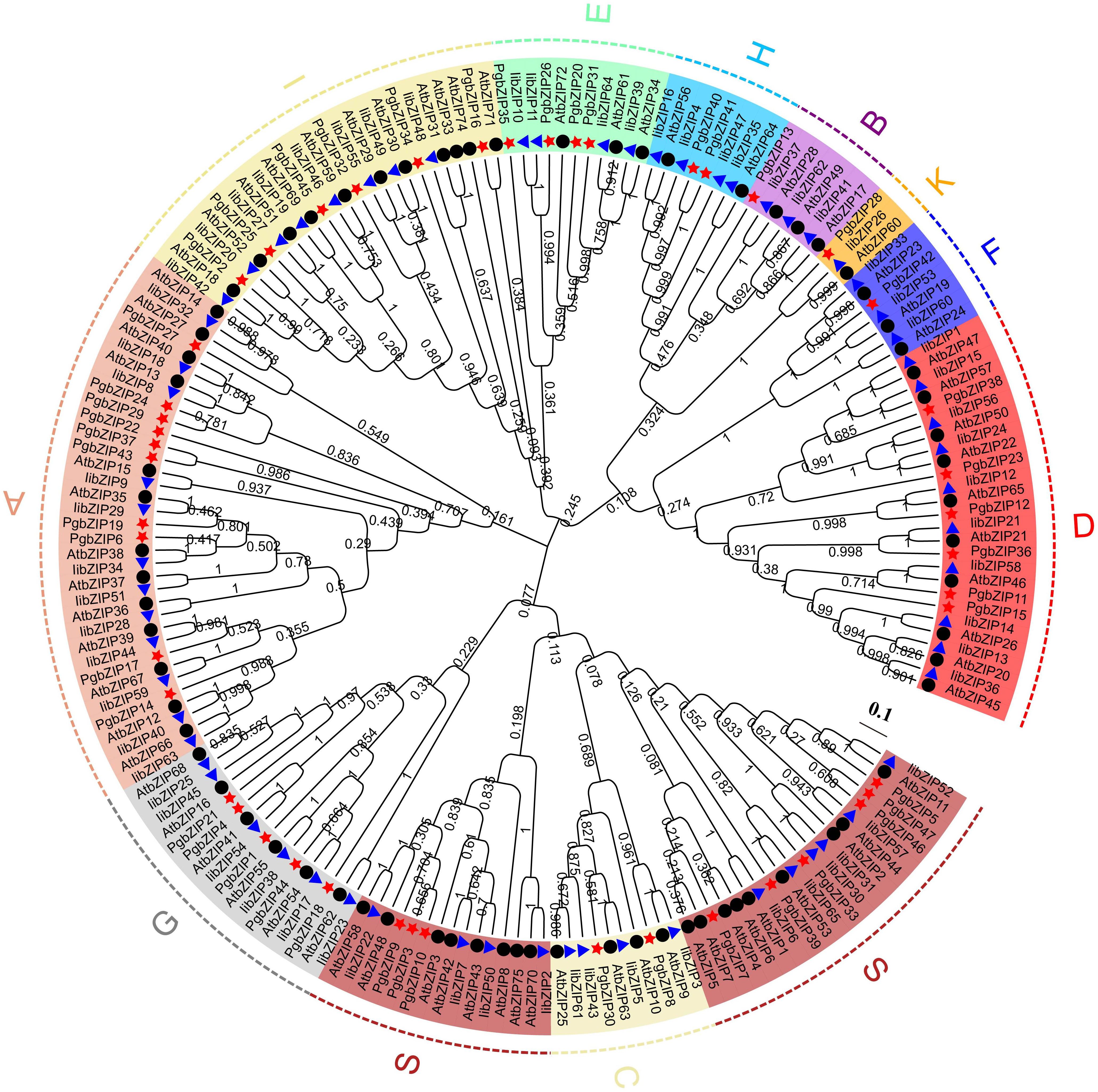

To explore the evolutionary relationships and classification of the PgbZIP gene family, we constructed NJ phylogenetic trees using MEGA X software (Supplementary Table 2). Based on the earlier classification results of the A. thaliana and I. indigotica bZIP gene family, 47 PgbZIP proteins were divided into 11 subfamilies (Figure 2), comprising A (10), B (1), C (2), D (6), E (4), F (1), G (5), H (2), I (6), K (1) and S (9). The outcome of phylogenetic tree evaluation confirmed that the bZIP genes of P. grandiflorus, A. thaliana and I. indigotica were highly homologous in each cluster.

Figure 2 The phylogenetic relationship and classification of the of the bZIP proteins in P. grandiflorus, I. indigotica and A. thaliana. The bootstrap value were set to 1000 replications. Subfamilies are marked with distinct colors. The red star, blue triangle and black dots point out the bZIP proteins of P. grandiflorus, I. indigotica and A. thaliana, respectively.

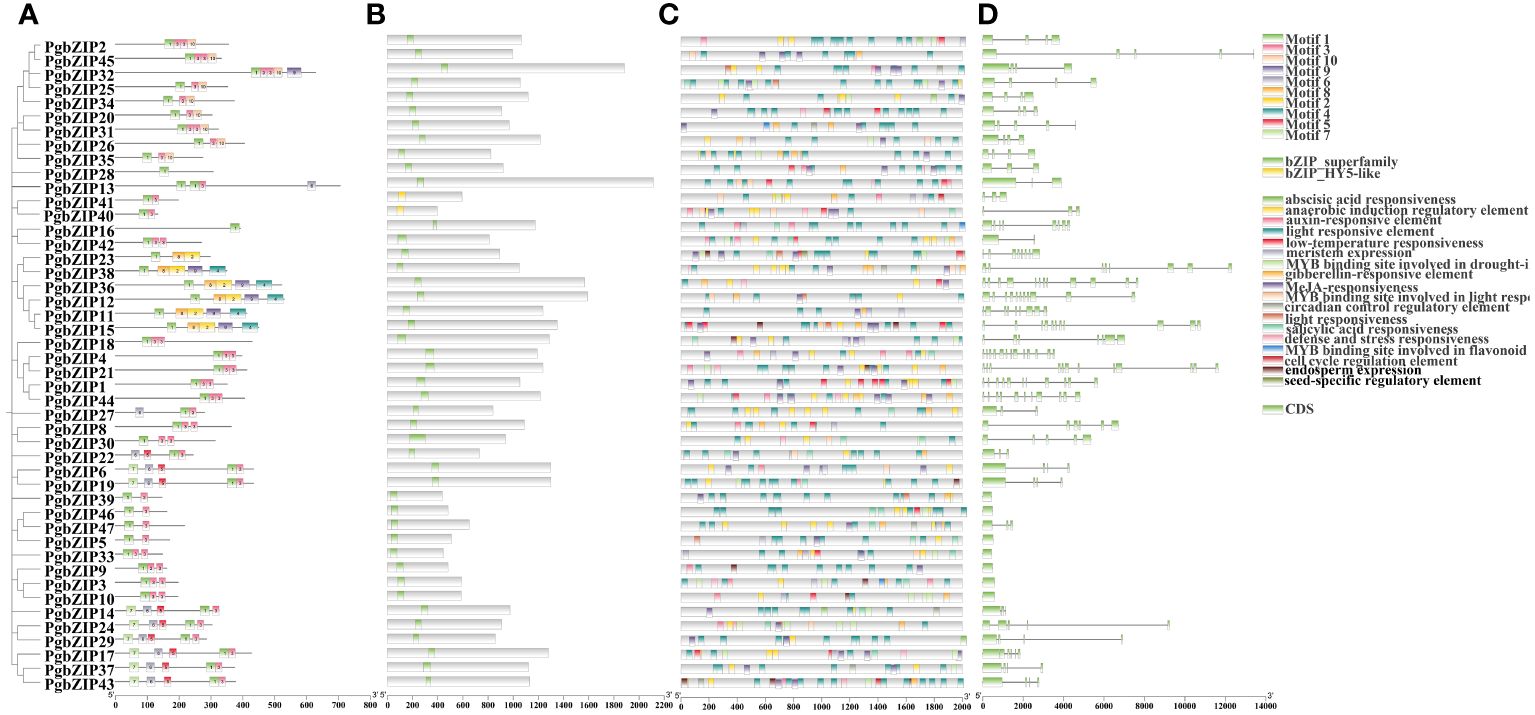

To explore the structural similarity of PgbZIP proteins, 10 conserved motifs have been recognized the use of the MEME website (Figure 3A). These motifs vary in size from 21–50 AA, with at least 1 to 5 motifs distributed across 47 PgbZIP proteins, and all sequences have motif 1. Members of gene families with close evolutionary relationships have similar motif compositions; for example, G subfamily members all have motifs 1 and 3. Furthermore, all PgbZIP proteins contain conserved domains of the bZIP genes, proving that the outcome of gene identification had been dependable (Figure 3B).

Figure 3 Phylogenetic analysis motifs, conserved domains and cis-element analysis of the PgbZIP genes. (A) Distribution of motifs within each PgbZIP protein. (B) Conserved domains of PgbZIP proteins. (C) Distribution of different types of cis-elements in the promoter region of the PgbZIP genes. (D) PgbZIP gene structures, lines indicate introns. (D) Distribution of different types of cis-elements in the promoter region of the PgbZIP genes.

To research the potential transcriptional regulatory role of PgbZIP genes, in this study, cis-elements were extracted from the PlantCARE database using 2K bp upstream of the PgbZIP genes as the promoter region. A total of 929 valuable cis-elements were recognized in the promoter regions of 47 PgbZIP genes, these cis-elements could be broadly categorized into three groups (Figure 3C) (Supplementary Table 3). Relevant to plant growth include light responsive elements, meristem expression, endosperm expression, anaerobically induced regulatory elements, seed-specific regulatory response elements, cell cycle regulatory elements, and circadian regulatory elements. Hormone response related elements include MeJA responsive elements, auxin responsive elements, abscisic acid responsive elements, and gibberellin responsive elements. Involved in abiotic stress related including stress responsive and defense elements and low-temperature responsive elements. Interestingly, the PgbZIP gene has cis-elements that bind to the MYB gene, participating in photoresponse, drought response, and flavonoid synthesis. This suggests that the PgMYB gene may regulate PgbZIP, forming regulatory networks that exercise different biological functions.

In order to further clarify the evolution of the PgbZIP genes, we compared the PgbZIP gene sequences and analyzed the coding regions and introns (Figure 3D). Except for seven members of the S family who do not have introns, the number of introns in other members is distributed between 1 and 12. As anticipated, members of the same subfamily have a relatively conserved number of introns, such as the H subfamily, which has 2 introns, and the E subfamily, which has 3 to 4 introns.

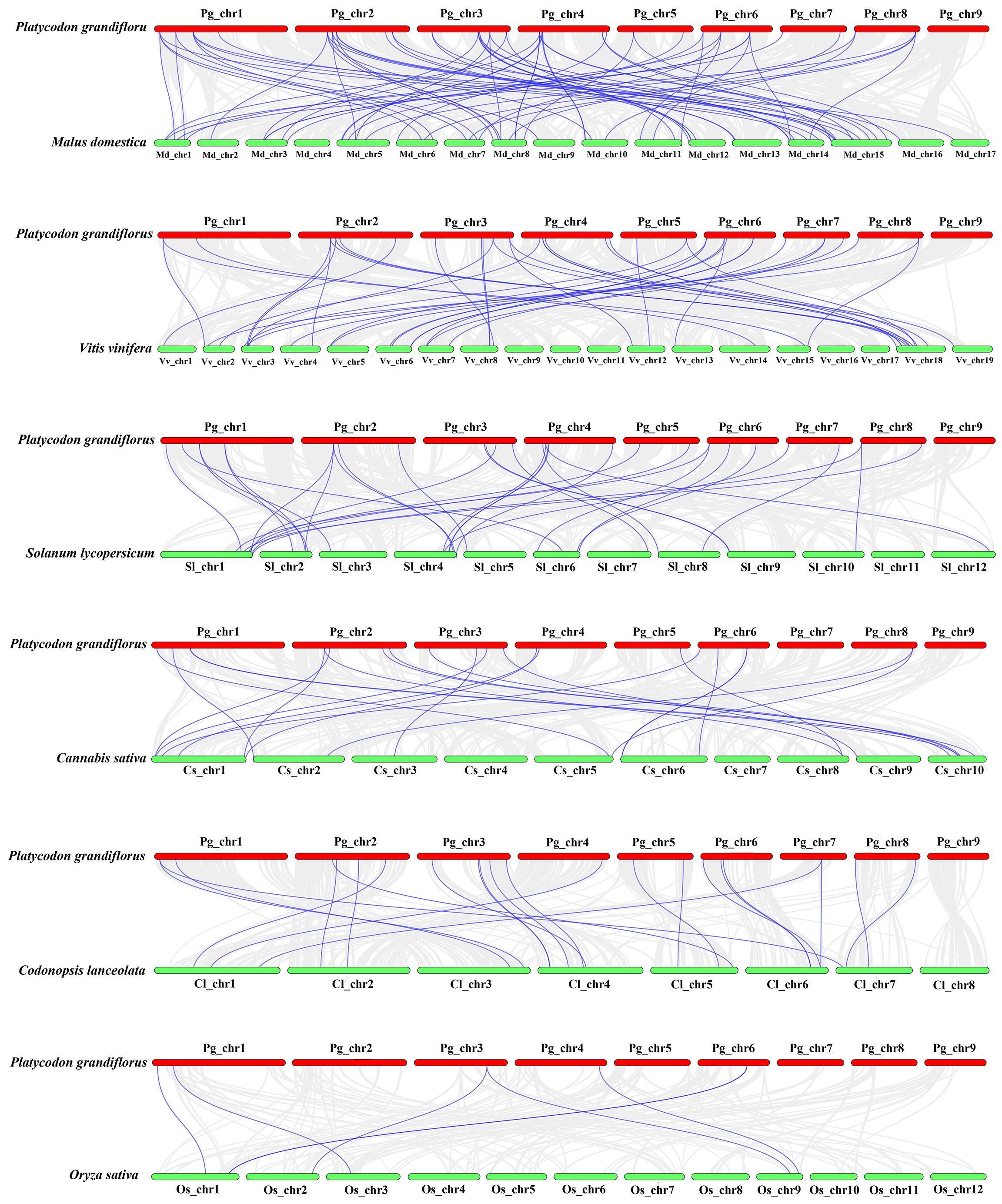

For investigating further the relationship of bZIP genes evolution among various plants, we compared interspecific synteny of P. grandiflorus with that of five dicotyledonous plants and one monocotyledonous plant (O. sativa) (Figure 4). Dicotyledonous plants include three fruit (M. domestica, V. vinifera and S. lycopersicum), and two medicinal plants (C. sativa and C. lanceolata). The results showed that the collinearity relationship between PgbZIP genes and MdbZIP genes was the closest, with 79 pairs of genes, 40 pairs of PgbZIP and VvbZIP genes, 32 pairs of PgbZIP and SlbZIP genes, 23 pairs of PgbZIP and ClbZIP genes, and the same pairs of CsbZIP genes. PgbZIP and OsbZIP had the worst collinearity relationship, with only 7 pairs of genes. These results indicate that most of these homologous bZIP genes occur after the differentiation of dicotyledons and monocotyledons. It is worth noting that PgbZIP1 (Pg_chr01_03120T) and PgbZIP19 (Pg_chr03_29870T) have syntenic gene pairs with 6 other species, which may have existed before species divergence and participated in the evolution of these plants.

Figure 4 Synteny analysis of bZIP genes between P.grandiflorus and M. domestica, V. vinifera, S. lycopersicum, C. sativa, C. lanceolata, and O. sativa. Gray lines symbolize the colinear blocks within P.grandiflorus and other genomes, Purple lines represent the syntenic bZIP gene pairs.

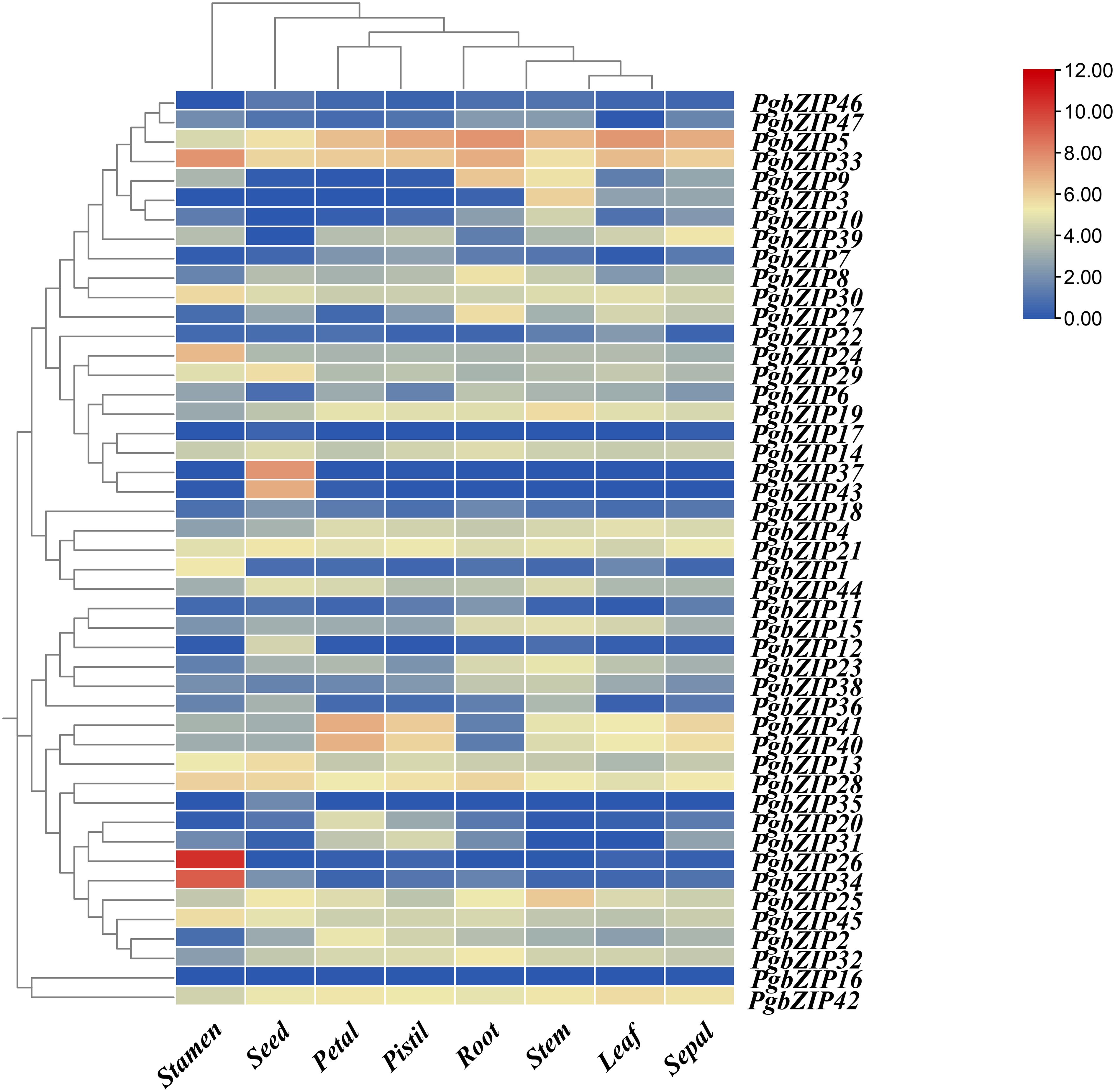

To investigate the expression profile of bZIP genes in P. grandiflorus tissues, the gene relative expression of 47 PgbZIP genes were analyzed based on RNA-seq data of P. grandiflorus root, leaf, seed, petal, stem, stamen, pistil, and sepal (Figure 5) (Supplementary Table 5). The findings indicated that 20 genes were expressed in leaf, 28 genes in petal, 34 genes in pistil, 32 genes in root, 38 genes in seed, 37 genes in sepal, 37 genes in stamen and 37 genes in stem (FPKM>0.5). A total of 10 genes (PgbZIP5, PgbZIP13, PgbZIP14, PgbZIP21, PgbZIP25, PgbZIP28, PgbZIP30, PgbZIP33, PgbZIP42 and PgbZIP45) were highly expressed in all tissues (FPKM>10), and these genes probably participating in the whole development processes of P. grandiflorus. PgbZIP16 and PgbZIP17 were not expressed in all tissues and may be pseudogenes or require specific conditions to activate expression. Interestingly, PgbZIP genes are also tissue-specific. For example, PgbZIP26 and PgbZIP34 are expressed only in stamens. PgbZIP12, PgbZIP35, PgbZIP37 and PgbZIP43 are only expressed in seeds. These genes involved in specific tissue expression may only be involved in the biological process of this tissue.

Figure 5 Heatmap of bZIP gene expression profiles in eight tissues of P. grandifloru. Data represent FPKM values from transcriptome data come from 8 tissues, including seed, leaf, petal, pistil, root, sepal, stamen and stem. Gene expression using Log2(FPKM+1) logarithmic transformation treatment.

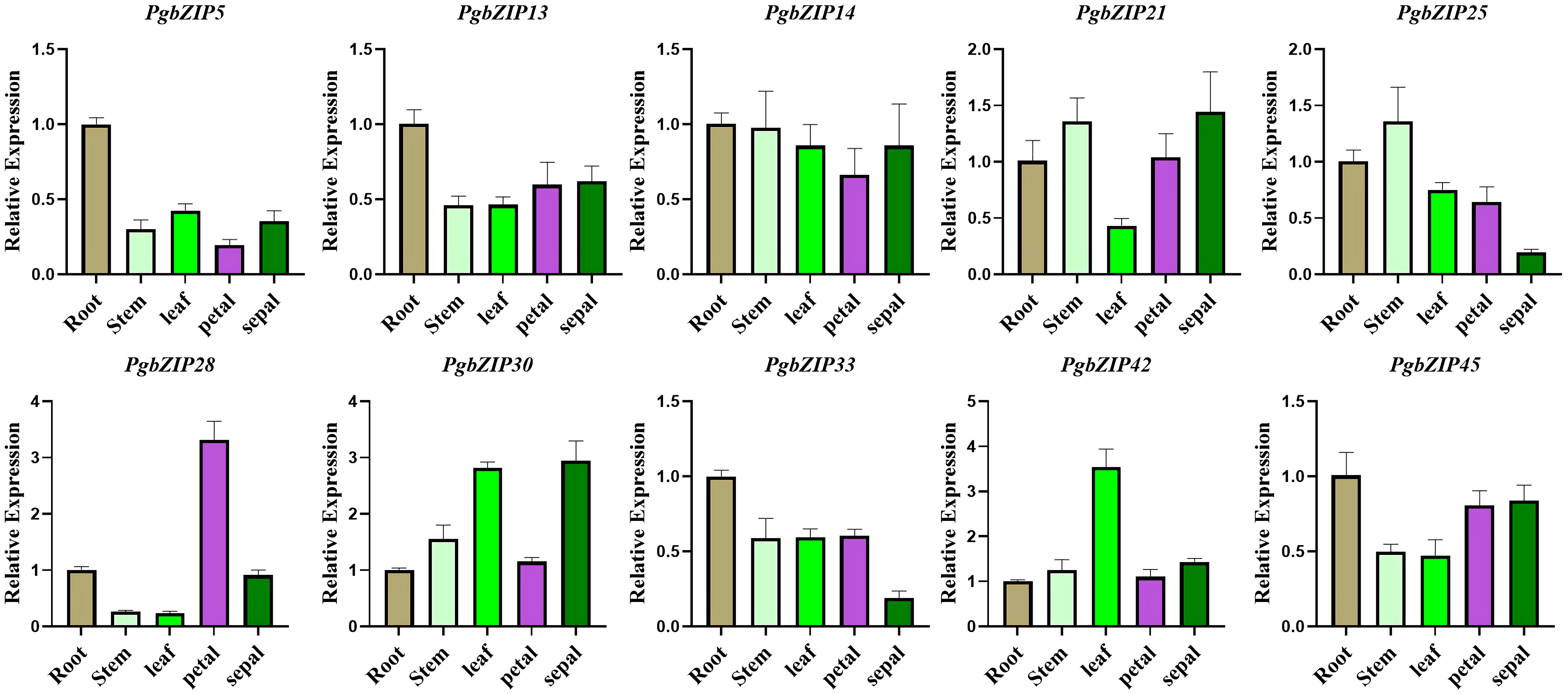

As mentioned above, subfamilies A (PgbZIP14), B (PgbZIP13), C (PgbZIP30), F (PgbZIP42), G (PgbZIP21), I (PgbZIP25/45), K (PgbZIP28) and S (PgbZIP5/33) have been expressed at very high levels in various tissue parts of P. grandiflorus, and are probably participated in the regulation of developmental process in all tissues. Therefore, those 10 PgbZIP genes were selected as candidate genes for qRT-PCR experiments to validate in this research (Supplementary Table 6). The relative expression of the 10 candidate genes were basically consistent to the expression trends obtained from the RNA-seq data (Figure 6). Notably, PgbZIP28 showed higher expression in petals, and PgbZIP30 and PgbZIP33 were expressed at higher levels in sepals than stems. All of the above suggest that these 10 PgbZIP genes possibly are closely involved to the developmental process of P. grandiflorus.

Figure 6 qRT–PCR analysis of PgbZIP genes in five different tissues of P. grandiflorus. Different colors represent different tissues. Use of the PgGAPDH gene as a reference gene.

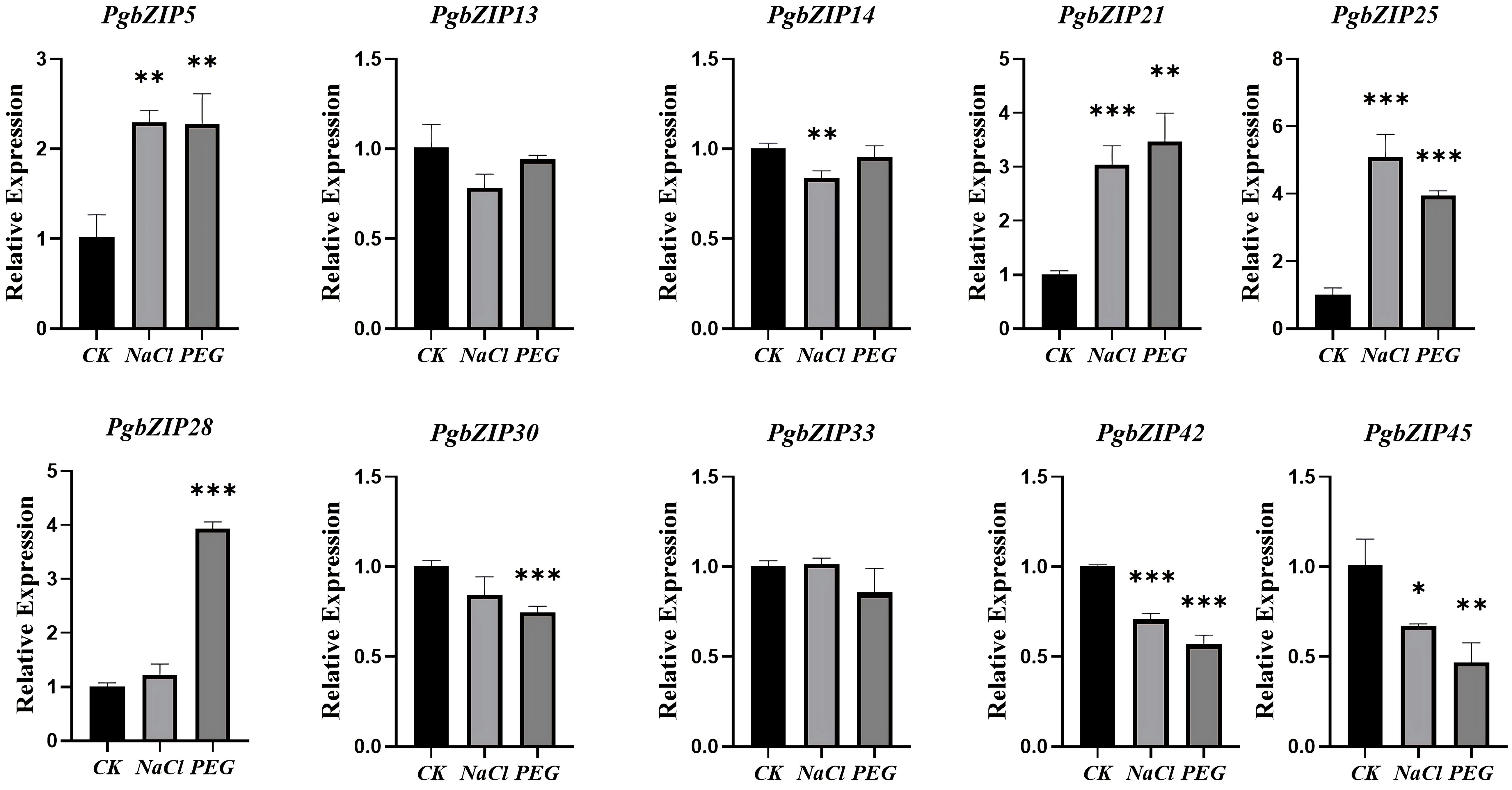

The root of P. grandiflorus is the main medicinal part. For studying the potential role of PgbZIP gene family under abiotic stress, the qRT-PCR experiments analysis was conducted using the roots of P. grandiflorus seedlings under drought and salt stress as templates (Figure 7). Compared with the normally growth group (CK), the expression levels of 4 genes (PgbZIP5, PgbZIP21, PgbZIP25 and PgbZIP28) were increased under both drought and salt stress. PgbZIP33 was only highly expressed under salt stress, but its expression was reduced under drought stress. These PgbZIP genes with increased expression levels under drought and salt stress could help P. grandifloru to resist abiotic stress.

Figure 7 qRT-PCR analysis of PgbZIP genes under drought and salt stress. CK: normal growth group; Salt stress and drought stress simulated using NaCl and PEG. The PgGAPDH gene was used as a reference gene. The significance analysis was carried out the use of a t-test. *, **, *** indicate significant difference in p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001.

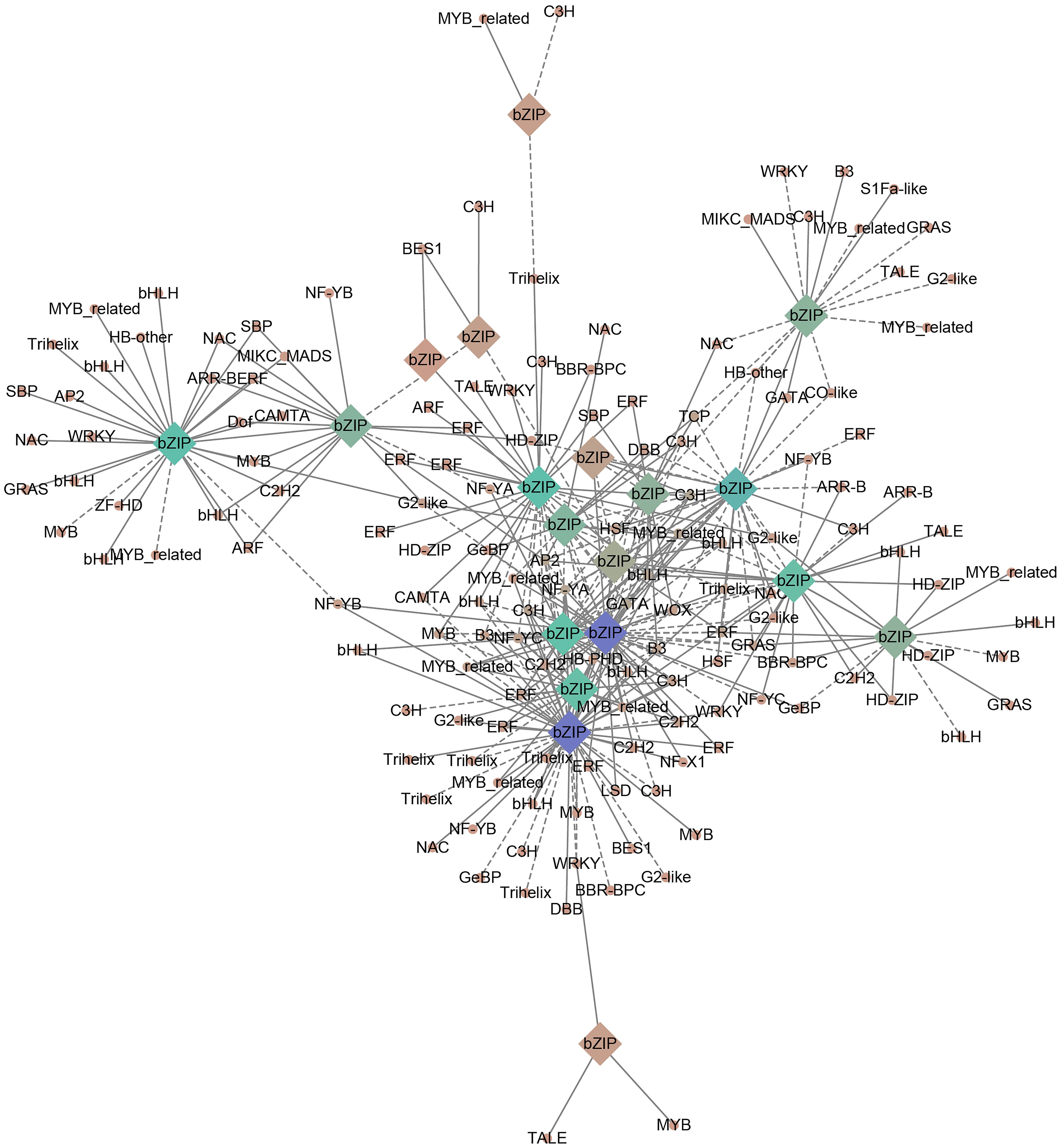

The bZIP genes often form an interaction networks with various TFs to participate in plant developmental processes. In order to mine the transcriptional regulatory network of PgbZIP in different tissues, this study characterized TFs in the RNA-seq data of 8 different tissues of P. grandiflorus and constructed a correlation network. A total of 1567 TFs were identified and categorized into 58 gene families, among which the top 5 were ERF (136), bHLH (118), C2H2 (115), MYB (105) and NAC (90). The expression profiles of all genes in the RNA-seq data of 8 different tissues of P.grandiflorus were analyzed using Python script to explore the TFs co-expressed with the PgbZIP gene. In the correlation network, a total of 19 PgbZIPs were co-expressed with 149 TFs, and 168 nodes with 361 network pairs were found. The positive (r > 0.7) (P < 0.05) and negative (r < -0.7) (P < 0.05) correlation network pairs are 232 and 129, respectively (Figure 8). PgbZIP45, PgbZIP30, PgbZIP13 and PgbZIP32 were presented as hub genes (degree≧30). The highest correlations (degree≧7) among TFs were Pg_chr05_09390T (GATA), Pg_chr08_31480T (C3H), Pg_chr02_03150T (MYB-related), Pg_chr01_14460T (AP2), Pg_chr06_07740T (bHLH), and Pg_contig26001_00320T (NF-YA) (Supplementary Table 7). These TFs has been shown to function in regulating plant growth and development in a large number of studies. Therefore, PgbZIP genes could be interacting with these TFs to form a regulatory network and participate in the development process of P.grandiflorus.

Figure 8 PgbZIP genes correlation network established using RNA-seq data from 8 tissues of P.grandiflorus. Circles represent co-expressed transcription factors, and diamonds represent the PgbZIP genes. Positive and negative correlations are indicated by solid and dashed lines, respectively. The shade of the color indicates the amount of genes correlated.

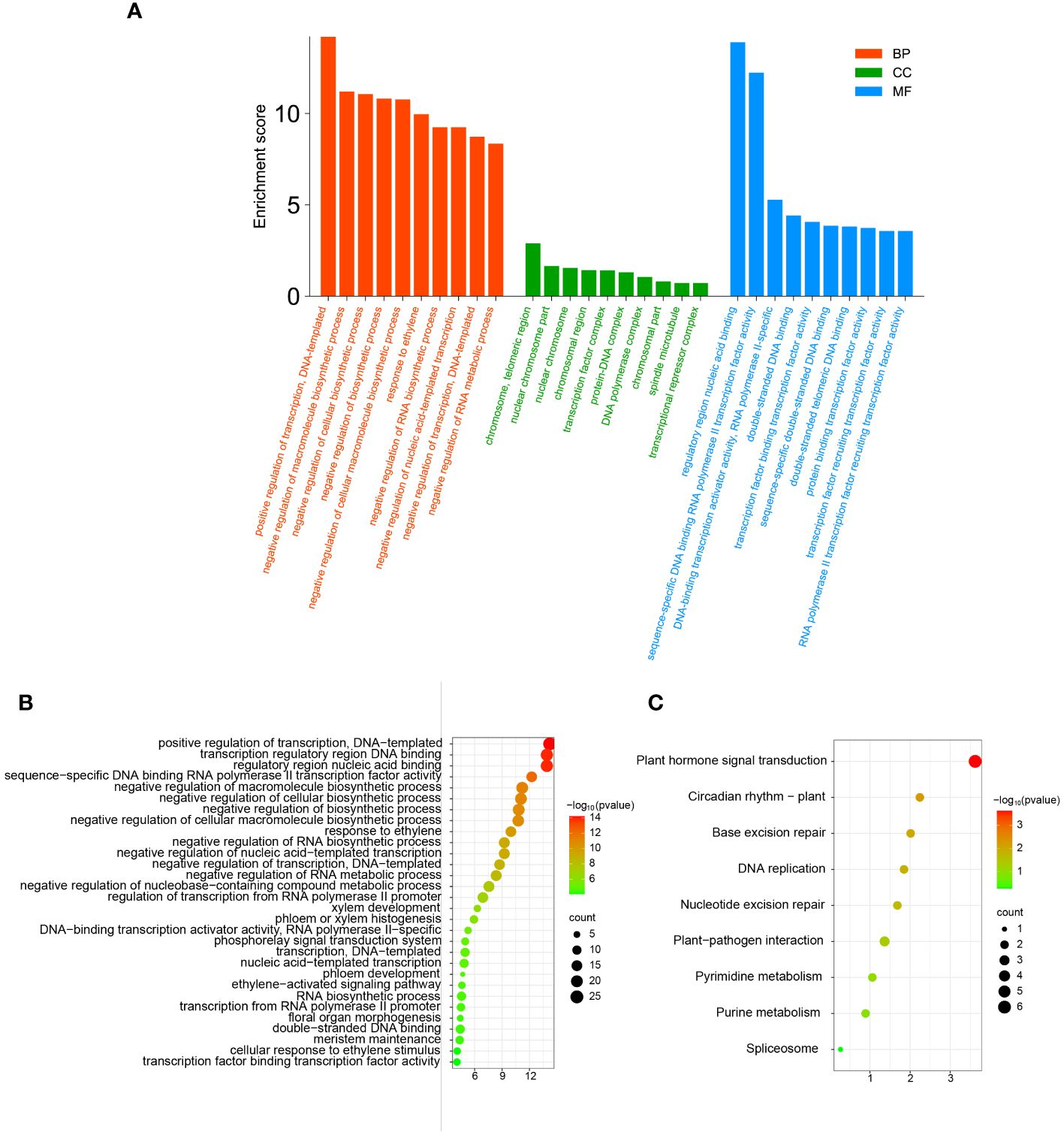

In order to further clarify the functions of TFs in the network in biological processes and the pathways involved, we performed GO annotation, GO and KEGG enrichment analyses of all TFs in the correlation network (Figure 9). The results of the analysis of the GO annotation findings suggests that those genes function in the molecular function classification for recruitment of TFs and activation of transcriptional activity (Figure 9A). In the cellular component classification, these genes were found to be predominantly distributed in the telomeric region, chromosome, nuclear chromosome and spindle microtubule. In biological processes, these genes are mainly involved in response to ethylene, negative regulation of macromolecular biosynthesis processes, negative regulation of RNA metabolic processes and ethylene response (Supplementary Table 8).

Figure 9 The GO annotation and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of TFs in correlation networks. (A) The GO annotation of TFs in correlation networks. (B) The GO enrichment analysis of TFs in correlation networks. (C) The KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of TFs in correlation networks.

Similarly, we performed GO and KEGG enrichment analysis of TFs in the correlation network. The outcome of GO enrichment analysis indicated that the main functions of these genes are transcription factor binding transcription factor activity, cellular response to ethylene stimulus, meristem maintenance, response to ethylene, xylem development, phloem development, floral organ morphogenesis, meristem maintenance, and so on (Figure 9B). The outcome of KEGG enrichment indicated that these TFs were primarily enriched in circadian rhythm, phytohormone signal transduction, nucleotide excision repair, plant-pathogen interaction, pyrimidine metabolism, purine metabolism and so on (Figure 9C). These outcomes indicate that the TFs in the correlation network are participating in most bioprocesses in plants and play a certain role.

The bZIP transcription factors are among the most widely distributed and conserved families of eukaryotic TFs, and have been more thoroughly researched in the plant field (Li et al., 2016). The bZIP TFs are widely involved in plant developmental process, biotic and abiotic stress response, and regulation of plant secondary metabolite synthesis such as terpenoids (Zhong et al., 2021). P. grandiflorus is a species of both medicine and food. Its young shoots and roots are often used to make pickles, cold soups and sauces. Similarly, the dried root of P. grandiflorus is a traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) called PLATYCODONIS RADIX, which has a variety of pharmacological effects and is a commonly used bulk of TCM (Ma et al., 2021). In the context of the post-epidemic era, the concept of “preventing disease” has gradually taken root in people’s hearts, and the concept of health care based on the same source of medicine and food will be the focus of attention at home and abroad in the future. As one of the representative medicinal materials of the same source of medicine and food, the international requirement for its raw materials is increasing, but the quality of different production areas is different. Therefore, studying the molecular regulatory mechanisms of the developmental process of P. grandiflorus to increase its productivity and high quality has emerged as a research hotspot. The bZIP TFs were extensively studied in various plants, but not in P. grandiflorus. In this present work, 47 PgbZIP genes were recognized by bioinformatics methods, which was similar to most previous reports, such as 49 in Solanum tuberosum (Wang et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021), 54 in Litchi chinensis (Hou et al., 2022), 59 in Castanea mollissima (Zhang et al., 2023), 65 in Lagenaria siceraria (Wang et al., 2022) and 65 in I. tinctoria. A deeper analysis revealed that all PgbZIP genes included the bZIP conserved domains, suggesting that the identification results were reliable and accurate. Similarly, motif1 and motif3 comprise a leucine zipper region and base region of the bZIP genes, consistent with the identification of bZIP TFs in Nicotiana tabacum (Duan et al., 2022).

Phylogenetic analysis can identify homologous genes in different species for the purpose of predicting the function of unknown genes. In this study, a total of 47 PgbZIP protein and 75 A. thaliana bZIP protein have been employed to build a phylogenetic trees, which was divided into 11 subfamilies and showed good clustering results. In subfamily A, the PgbZIP6 and PgbZIP19 proteins were homologous with AtbZIP36, and the PgbZIP17 protein was homologous with AtbZIP36, indicating that the three PgbZIP proteins probably have important functions in ABA induction and stress treatment (Choi et al., 2000). Similarly, in subfamily D, AtbZIP46 is participating in the progression of A. thaliana flower and plays a role in regulating the size of meristems or floral organ number (Chuang et al., 1999), and its homologous gene PgbZIP15 probably has the same functionality. Notably, the H subfamily have two genes, namely, HY5 (AtbZIP56) and HYH (AtbZIP64), while the H subfamily in the PgbZIP gene family contains only two HY5 genes (PgbZIP40, PgbZIP41) but no HYH gene, suggests that there could be possible gene expansions and deletions in the PgbZIP gene family that may have occurred during the evolutionary process.

The function of transcription factors is highly correlated with their expression patterns (Wang et al., 2023). Earlier research has indicated that the bZIP gens were participating in the developmental processes of various tissues and organs in plants. Coexpression of AtbZIP10/25 with ABI3 significantly increases the activation capacity of the At2S1 promoter to form a regulatory complex for seed-specific expression (Lara et al., 2003). The AtbZIP9 gene is involved in regulating leaves and vascular bundle development (Silveira et al., 2007). Overexpression of OsbZIP49 in O. sativa reduced internode length and plant height in transgenic rice, which exhibited a tiller-spreading phenotype (Ding et al., 2021). Overexpression of the Capsicum annuum CabZIP1 gene in A. thaliana can slow plant growth and decrease the amount of petals (Lee et al., 2006). To identify the regulatory functions of PgbZIP genes in P. grandiflorus development, 10 PgbZIP genes (PgbZIP5, PgbZIP13, PgbZIP14, PgbZIP21, PgbZIP25, PgbZIP28, PgbZIP30, PgbZIP33, PgbZIP42 and PgbZIP45) that were highly expressed in the transcriptome data of 8 tissues were selected as potential genes, the relative expression of those genes in stems, leaves, roots, petals and sepals have been analyzed by qRT-PCR. The relative expression of candidate genes were in accordance with the trend of RNA-seq data, suggesting these 10 candidate genes were participated in the development of various tissues of P. grandiflorus. Similarly, the PgbZIP genes also showed tissue-specific expression in different organs. Transcriptome data showed that PgbZIP12, PgbZIP35, PgbZIP37 and PgbZIP43 were only expressed in seed species, which predicted that they could be participated in seed developmental processes. A comparable tissue-specific expression patterns have been found for the bZIP TFs in species such as M. domestica (Wang et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021), Musa nana (Hu et al., 2016), and Citrullus lanatus (Yang et al., 2019).

In recent years, the biosynthesis of natural products has become increasingly popular. However, the molecular mechanisms by which TFs are involved in regulating the biosynthesis of plant secondary metabolism are complex. The triterpenoid saponins of P. grandiflorus are very important secondary metabolites, that are mainly enriched in roots (Zhang et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2015). Root development is a complex process regulated by the expression of multiple genes and influenced by endogenous hormone levels and natural resources (Siqueira et al., 2022). During energy deprivation in A. thaliana, AtbZIP63 activates AtARF19 expression in response to basal lateral root initiation (Muralidhara et al., 2021). Under stress and normal conditions, different levels of ABA (abscisic acid) regulate the development of plant root architecture, including the initiation and elongation of main, adventitious, adventitious roots, and root hairs, as well as root system hydrophilicity and geotropism (Teng et al., 2023). Similarly, bZIP TFs perform important functions in the control of terpenoids; for example, the bZIP TF AaTGA6 in A. annua is involved in the regulation of salicylic acid (SA) in the synthesis of artemisinin (Lv et al., 2019), and AabZIP1 is involved in ABA signaling, which in turn regulates artemisinin biosynthesis (Zhang et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022). In this study, cis-elements for physiological control, hormonal response and stress response were detected in the promoter region of the PgbZIP gene, suggesting that the PgbZIP gene with these elements performs an essential function in the regulation of root developmental processes and terpene biosynthesis in P. grandifloru.

With the fast speed of modern industrial development and climate change, plants suffer from abiotic stress increasingly frequently in the manner of increase and development, which conduct to a reduction in yield, quality damage, and even plant death (Zhang et al., 2022). To cope with the stress caused by adverse environments, plants have evolved various mechanisms, including the regulation of gene expression through various transcription factors, so that plants can adapt to or escape the effects of stress (Badis et al., 2009). Among these transcription factors, the bZIP TFs has been widely reported to enhance the ability of response to biotic and abiotic stresses. For example, OsbZIP71 gene in O. sativa enhances the tolerance to drought and salinity by activating the expression of the OsNHX1 protein and COR413-TM1 protein (Liu et al., 2014). In V. vinifera, the VvbZIP23 expression is induced by a number of abiotic stresses, including cold, salinity and drought stress (Tak and Mhatre, 2013). The Hordeum vulgare bZIP TF HvABI5 is participating in ABA-dependent regulation of resistance to drought stress (Collin et al., 2020). In this study, PgbZIP5, PgbZIP21, PgbZIP25 and PgbZIP28 genes with significantly considerably elevated expression levels beneath drought and salinity stress were verified through qRT-PCR experiments. Additionally, PgbZIP33 was only highly expressed under salt stress. Among them, PgbZIP5 is the homologous gene of AtbZIP11, which may have the same features in resistance to stress (Weltmeier et al., 2009). PgbZIP21 and PgbZIP28 have cis-elements participating in defense and stress responses, and PgbZIP21, PgbZIP25, and PgbZIP33 have binding sites for drought regulation with PgMYB genes. PgbZIP28 and PgbZIP33 also contain low-temperature responsiveness elements. These 5 genes also have co-expression links with bHLH, GATA, MYB of the stress resistance related genes. It is hypothesized that those TFs might perform key functions in supporting P. grandiflorus to resist abiotic stress. However, the specific biological functions of these genes need to be further verified.

In this work, a number of 47 PgbZIP genes were characterized based on genome-wide analysis, and their chromosomal distribution, phylogenetic, motifs, gene structure, cis-element prediction, synteny and expression profiles have been comprehensively analyzed. Ten candidate PgbZIP genes that are expressed at high levels in all tissues indicate their crucial role in various physiological and biological processes, and the co-express network results also provide evidence for further research. The expression pattern of candidate genes under drought and salt stress provide valuable information for the expression of PgbZIP genes under salt and drought stress. These results provide clues to investigate the functions of the PgbZIP genes in the developmental processes of different plant organs and abiotic stress responses.

This study analyzed publicly available data from the NCBI database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Accession numbers: SRR8712510-SRR8712517.

ZW: Investigation, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. PW: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. HC: Formal analysis, Software, Writing – original draft. ML: Investigation, Software, Writing – original draft. LK: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. HW: Resources, Writing – original draft. WR: Resources, Software, Writing – original draft. QF: Formal analysis, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft. WM: Funding acquisition, Resources, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by Mechanism of WRKY transcription factor regulating Platycodin Biosynthesis (CZKYF2022-F04). National Key Research and development Project, research and demonstration of collection, screening and breeding technology of ginseng and other genuine medicinal materials (2021YFD1600901); Talent training project supported by the central government for the reform and development of local colleges and Universities (ZYRCB2021008); Heilongjiang Touyan Innovation Team Program (HLJTYTP2019001).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2024.1403220/full#supplementary-material

Badis, G., Berger, M. F., Philippakis, A. A., Talukder, S., Gehrke, A. R., Jaeger, A. S., et al. (2009). Diversity and complexity in dna recognition by transcription factors. Science 324, 1720–1723. doi: 10.1126/science.1162327

Bailey, T. L., Boden, M., Buske, F. A., Frith, M., Grant, C. E., Clementi, L., et al. (2009). Meme suite: tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, W202–W208. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp335

Bi, C., Yu, Y., Dong, C., Yang, Y., Zhai, Y., Du, F., et al. (2021). The bzip transcription factor tabzip15 improves salt stress tolerance in wheat. Plant Biotechnol. J. 19, 209–211. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13453

Chen, C., Chen, H., Zhang, Y., Thomas, H. R., Frank, M. H., He, Y., et al. (2020). Tbtools: an integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol. Plant 13, 1194–1202. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2020.06.009

Choi, H., Hong, J., Ha, J., Kang, J., Kim, S. Y. (2000). Abfs, a family of aba-responsive element binding factors. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 1723–1730. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.3.1723

Chuang, C. F., Running, M. P., Williams, R. W., Meyerowitz, E. M. (1999). The perianthia gene encodes a bzip protein involved in the determination of floral organ number in arabidopsis thaliana. Genes Dev. 13, 334–344. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.3.334

Collin, A., Daszkowska-Golec, A., Kurowska, M., Szarejko, I. (2020). Barley abi5 (abscisic acid insensitive 5) is involved in abscisic acid-dependent drought response. Front. Plant Sci. 11. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.01138

Ding, C., Lin, X., Zuo, Y., Yu, Z., Baerson, S. R., Pan, Z., et al. (2021). Transcription factor osbzip49 controls tiller angle and plant architecture through the induction of indole-3-acetic acid-amido synthetases in rice. Plant J. 108, 1346–1364. doi: 10.1111/tpj.15515

Duan, L., Mo, Z., Fan, Y., Li, K., Yang, M., Li, D., et al. (2022). Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the bzip transcription factor family genes in response to abiotic stress in nicotiana tabacum l. BMC Genomics 23, 318. doi: 10.1186/s12864-022-08547-z

Gai, W., Ma, X., Qiao, Y., Shi, B., Ul Haq, S., Li, Q., et al. (2020). Characterization of the bzip transcription factor family in pepper (capsicum annuum l.): Cabzip25 positively modulates the salt tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 11. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.00139

Gangappa, S. N., Botto, J. F. (2016). The multifaceted roles of hy5 in plant growth and development. Mol. Plant 9, 1353–1365. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2016.07.002

Hou, H., Kong, X., Zhou, Y., Yin, C., Jiang, Y., Qu, H., et al. (2022). Genome-wide identification and characterization of bzip transcription factors in relation to litchi (litchi chinensis sonn.) Fruit ripening and postharvest storage. Int. J. Biol. Macromol 222, 2176–2189. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.09.292

Hu, W., Wang, L., Tie, W., Yan, Y., Ding, Z., Liu, J., et al. (2016). Genome-wide analyses of the bzip family reveal their involvement in the development, ripening and abiotic stress response in banana. Sci. Rep. 6, 30203. doi: 10.1038/srep30203

Jakoby, M., Weisshaar, B., Dröge-Laser, W., Vicente-Carbajosa, J., Tiedemann, J., Kroj, T., et al. (2002). Bzip transcription factors in arabidopsis. Trends Plant Sci. 7, 106–111. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(01)02223-3

Ji, M., Bo, A., Yang, M., Xu, J., Jiang, L., Zhou, B., et al. (2020). The pharmacological effects and health benefits of platycodon grandiflorus—a medicine food homology species. Foods 9, 142. doi: 10.3390/foods9020142

Jiang, M., Wang, Z., Ren, W., Yan, S., Xing, N., Zhang, Z., et al. (2022). Identification of the bzip gene family and regulation of metabolites under salt stress in isatis indigotica. Front. Plant Sci. 13. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.1011616

Jing, L., Hanwen, Y., Mengli, L., Bowen, C., Nan, D., Chang, X., et al. (2022). Transcriptome-wide identification of wrky transcription factors and their expression profiles in response to methyl jasmonate in platycodon grandiflorus. Plant Signaling Behav. 17, 2089473. doi: 10.1080/15592324.2022.2089473

Kim, J., Kang, S. H., Park, S. G., Yang, T. J., Lee, Y., Kim, O. T., et al. (2020). Whole-genome, transcriptome, and methylome analyses provide insights into the evolution of platycoside biosynthesis in platycodon grandiflorus, a medicinal plant. Hortic. Res. 7, 112. doi: 10.1038/s41438-020-0329-x

Kong, L., Sun, J., Jiang, Z., Ren, W., Wang, Z., Zhang, M., et al. (2023). Identification and expression analysis of yabby family genes in platycodon grandiflorus. Plant Signal Behav. 18, 2163069. doi: 10.1080/15592324.2022.2163069

Kumar, S., Stecher, G., Li, M., Knyaz, C., Tamura, K. (2018). Mega x: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 1547–1549. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy096

Lan, Y., Pan, F., Zhang, K., Wang, L., Liu, H., Jiang, C., et al. (2023). Phebzip47, a bzip transcription factor from moso bamboo (phyllostachys edulis), positively regulates the drought tolerance of transgenic plants. Ind. Crops Products 197. doi: 10.1016/J.INDCROP.2023.116538

Lara, P., Oñate-Sánchez, L., Abraham, Z., Ferrándiz, C., Díaz, I., Carbonero, P., et al. (2003). Synergistic activation of seed storage protein gene expression in arabidopsis by abi3 and two bzips related to opaque2. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 21003–21011. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210538200

Lee, D. J., Choi, J. W., Kang, J. N., Lee, S. M., Park, G. H., Kim, C. K. (2023). Chromosome-scale genome assembly and triterpenoid saponin biosynthesis in korean bellflower (platycodon grandiflorum). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 6534. doi: 10.3390/ijms24076534

Lee, S. C., Choi, H. W., Hwang, I. S., Choi, D. S., Hwang, B. K. (2006). Functional roles of the pepper pathogen-induced bzip transcription factor, cabzip1, in enhanced resistance to pathogen infection and environmental stresses. Planta 224, 1209–1225. doi: 10.1007/s00425-006-0302-4

Lescot, M., Déhais, P., Thijs, G., Marchal, K., Moreau, Y., Peer, Y., et al. (2002). Plantcare, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 325–327. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.325

Li, Y., Meng, D., Li, M., Cheng, L. (2016). Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the bzip gene family in apple (malus domestica). Tree Genet. Genomes 12, 82. doi: 10.1007/s11295-016-1043-6

Liu, M., Liu, T., Liu, W., Wang, Z., Kong, L., Lu, J., et al. (2023). Genome-wide identification and expression profiling analysis of the trihelix gene family and response of pggt1 under abiotic stresses in platycodon grandiflorus. Gene 869, 147398. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2023.147398

Liu, C., Mao, B., Ou, S., Wang, W., Liu, L., Wu, Y., et al. (2014). Osbzip71, a bzip transcription factor, confers salinity and drought tolerance in rice. Plant Mol. Biol. 84, 19–36. doi: 10.1007/s11103-013-0115-3

Livak, K. J., Schmittgen, T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative pcr and the 2(-delta c(t)) method. Methods 25, 402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262

Lv, Z., Guo, Z., Zhang, L., Zhang, F., Jiang, W., Shen, Q., et al. (2019). Interaction of bzip transcription factor tga6 with salicylic acid signaling modulates artemisinin biosynthesis in artemisia annua. J. Exp. Bot. 70, 3969–3979. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erz166

Ma, C., Gao, Z., Zhang, J., Zhang, W., Shao, J., Hai, M., et al. (2016). Candidate genes involved in the biosynthesis of triterpenoid saponins in platycodon grandiflorum identified by transcriptome analysis. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 673. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00673

Ma, X., Shao, S., Xiao, F., Zhang, H., Yan, M. (2021). Platycodon grandiflorum extract: chemical composition and whitening, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory effects. Rsc Adv. 11, 10814–10826. doi: 10.1039/D0RA09443A

Muralidhara, P., Weiste, C., Collani, S., Krischke, M., Kreisz, P., Draken, J., et al. (2021). Perturbations in plant energy homeostasis prime lateral root initiation via snrk1-bzip63-arf19 signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2106961118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2106961118

Nijhawan, A., Jain, M., Tyagi, A. K., Khurana, J. P. (2008). Genomic survey and gene expression analysis of the basic leucine zipper transcription factor family in rice. Plant Physiol. 146, 333–350. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.112821

Shannon, P., Markiel, A., Ozier, O., Baliga, N. S., Wang, J. T., Ramage, D., et al. (2003). Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 13, 2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303

Sharma, P. D., Singh, N., Ahuja, P. S., Reddy, T. V. (2011). Abscisic acid response element binding factor 1 is required for establishment of arabidopsis seedlings during winter. Mol. Biol. Rep. 38, 5147–5159. doi: 10.1007/s11033-010-0664-3

Shen, Q., Huang, H., Zhao, Y., Xie, L., He, Q., Zhong, Y., et al. (2019). The transcription factor aabzip9 positively regulates the biosynthesis of artemisinin in artemisia annua. Front. Plant Sci. 10, 1294. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.01294

Silveira, A. B., Gauer, L., Tomaz, J. P., Cardoso, P. R., Carmello-Guerreiro, S., Vincentz, M. (2007). The arabidopsis atbzip9 protein fused to the vp16 transcriptional activation domain alters leaf and vascular development. Plant Ence 172, 1148–1156. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2007.03.003

Siqueira, J. A., Otoni, W. C., Araújo, W. L. (2022). The hidden half comes into the spotlight: peeking inside the black box of root developmental phases. Plant Commun. 3, 100246. doi: 10.1016/j.xplc.2021.100246

Tak, H., Mhatre, M. (2013). Cloning and molecular characterization of a putative bzip transcription factor vvbzip23 from vitis vinifera. Protoplasma 250, 333–345. doi: 10.1007/s00709-012-0417-3

Teng, Z., Lv, J., Chen, Y., Zhang, J., Ye, N. (2023). Effects of stress-induced aba on root architecture development: positive and negative actions. Crop J. 11, 1072–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.cj.2023.06.007

Tian, J. H., Shu, J. X., Xu, L., Ya, H., Yang, L., Liu, S., et al. (2023). Genome-wide identification of r2r3-myb transcription factor family in docynia delavayi (franch.) Schneid and its expression analysis during the fruit development. Food Bioscience 54, 102878. doi: 10.1016/j.fbio.2023.102878

Untergasser, A., Cutcutache, I., Koressaar, T., Ye, J., Faircloth, B. C., Remmet, M., et al. (2012). Primer3–new capabilities and interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, e115. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks596

Wang, Q., Guo, C., Li, Z., Guo, Y. (2021). Identification and analysis of bzip family genes in potato and their potential roles in stress responses. Front. Plant Sci. 12. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.637343

Wang, Y., Tang, H., Debarry, J. D., Tan, X., Li, J., Wang, X., et al. (2012). Mcscanx: a toolkit for detection and evolutionary analysis of gene synteny and collinearity. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, e49. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1293

Wang, J., Wang, Y., Wu, X., Wang, B., Lu, Z., Zhong, L., et al. (2022). Insight into the bzip gene family in lagenaria siceraria: genome and transcriptome analysis to understand gene diversification in cucurbitaceae and the roles of lsbzip gene expression and function under cold stress. Front. Plant Sci. 13. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.1128007

Wang, Z., Zhang, Z., Wang, P., Qin, C., He, L., Kong, L., et al. (2023). Genome-wide identification of the nac transcription factors family and regulation of metabolites under salt stress in isatis indigotica. Int. J. Biol. Macromol 240, 124436. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.124436

Wang, S., Zhang, R., Zhang, Z., Zhao, T., Zhang, D., Sofkova, S., et al. (2021). Genome-wide analysis of the bzip gene lineage in apple and functional analysis of mhabf in malus halliana. Planta 254, 78. doi: 10.1007/s00425-021-03724-y

Weltmeier, F., Rahmani, F., Ehlert, A., Dietrich, K., Schütze, K., Wamg, X., et al. (2009). Expression patterns within the arabidopsis c/s1 bzip transcription factor network: availability of heterodimerization partners controls gene expression during stress response and development. Plant Mol. Biol. 69, 107–119. doi: 10.1007/s11103-008-9410-9

Yang, Y., Li, J., Li, H., Yang, Y., Guang, Y., Zhou, Y., et al. (2019). The bzip gene family in watermelon: genome-wide identification and expression analysis under cold stress and root-knot nematode infection. Peerj 7, e7878. doi: 10.7717/peerj.7878

Zhang, S., Chai, X., Hou, G., Zhao, F., Meng, Q. (2022). Platycodon grandiflorum (jacq.) A. Dc.: A review of phytochemistry, pharmacology, toxicology and traditional use. Phytomedicine 106, 154422. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2022.154422

Zhang, F., Fu, X., Lv, Z., Lu, X., Shen, Q., Zhang, M., et al. (2015). A basic leucine zipper transcription factor, aabzip1, connects abscisic acid signaling with artemisinin biosynthesis in artemisia annua. Mol. Plant 8, 163–175. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2014.12.004

Zhang, P., Liu, J., Jia, N., Wang, M., Lu, Y., Wang, D., et al. (2023). Genome-wide identification and characterization of the bzip gene family and their function in starch accumulation in chinese chestnut (castanea mollissima blume). Front. Plant Sci. 14. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2023.1166717

Zhang, T., Song, C., Song, L., Shang, Z., Yang, S., Wang, D., et al. (2017). Rna sequencing and coexpression analysis reveal key genes involved in α-linolenic acid biosynthesis in perilla frutescens seed. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18, 2433. doi: 10.3390/ijms18112433

Zhang, L., Wang, Y., Yang, D., Zhang, C., Zhang, N., Li, M., et al. (2015). Platycodon grandiflorus - an ethnopharmacological, phytochemical and pharmacological review. J. Ethnopharmacol 164, 147–161. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.01.052

Zhang, H., Zhu, J., Gong, Z., Zhu, J. K. (2022). Abiotic stress responses in plants. Nat. Rev. Genet. 23, 104–119. doi: 10.1038/s41576-021-00413-0

Zhao, J., Guo, R., Guo, C., Hou, H., Wang, X., Gao, H. (2016b). Evolutionary and expression analyses of the apple basic leucine zipper transcription factor family. Front. Plant Sci. 7. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00376

Keywords: Platycodon grandiflorus, bZIP transcription factor, evolutionary analyses, expression profiling, abiotic stress

Citation: Wang Z, Wang P, Cao H, Liu M, Kong L, Wang H, Ren W, Fu Q and Ma W (2024) Genome-wide identification of bZIP transcription factors and their expression analysis in Platycodon grandiflorus under abiotic stress. Front. Plant Sci. 15:1403220. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2024.1403220

Received: 19 March 2024; Accepted: 13 May 2024;

Published: 28 May 2024.

Edited by:

Ertugrul Filiz, Duzce University, TürkiyeReviewed by:

Xiaomei Zhang, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, ChinaCopyright © 2024 Wang, Wang, Cao, Liu, Kong, Wang, Ren, Fu and Ma. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Weichao Ren, bHp5cmVud2VpY2hhb0AxMjYuY29t; Qifeng Fu, MjY5NzAyNjEzQHFxLmNvbQ==; Wei Ma, bWF3ZWlAaGxqdWNtLmVkdS5jbg==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.