- 1College of Forestry, Nanjing Forestry University, Nanjing, China

- 2Institute of Qiong Bamboo, Southwest Forestry University, Kunming, China

- 3Key Laboratory of State Forestry Administration on Biodiversity Conservation in Southwest China, Southwest Forestry University, Kunming, China

- 4College of forestry, Southwest Forestry University, Kunming, China

- 5Daguan County Forestry and Grassland Bureau, Zhaotong, China

Objectives: Bamboo is a globally significant plant with ecological, environmental, and economic bene-fits. Choosing suitable native tree species for mixed planting in bamboo forests is an effective measure for achieving both ecological and economic benefits of bamboo forests. However, little is currently known about the impact of bamboo forests on nitrogen cycling and utilization efficiency after mixing with other tree species. Therefore, our study aims to compare the nitrogen cycling in pure bamboo forests with that in mixed forests.

Methods: Through field experiments, we investigated pure Qiongzhuea tumidinoda forests and Q. tumidinoda-Phellodendron chinense mixed forests, and utilized 15N tracing technology to explore the fertilization effects and fate of urea-15N in different forest stands.

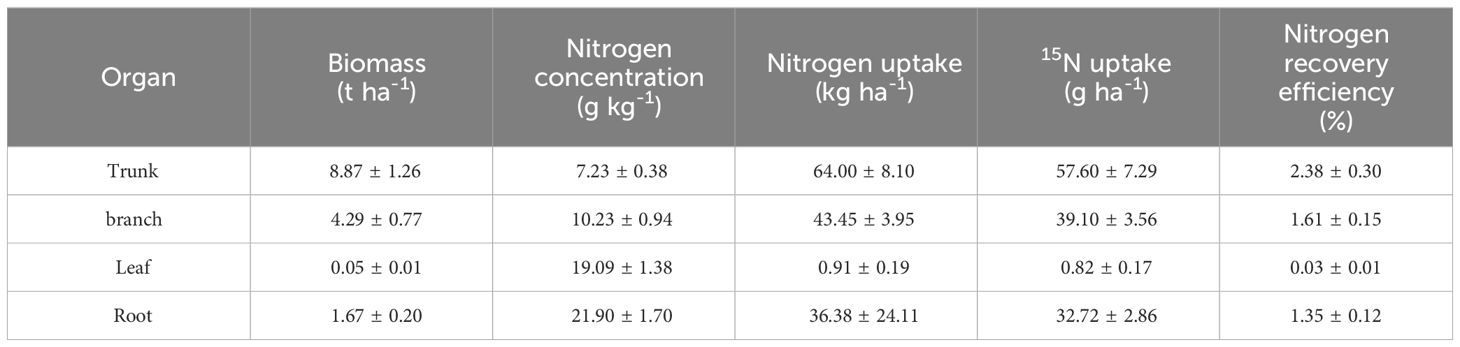

Results: The results demonstrated the following: 1) in both forest stands, bamboo culms account for the highest biomass percentage (42.99%-51.86%), while the leaves exhibited the highest nitrogen concentration and total nitrogen uptake (39.25%-44.52%/29.51%-33.21%, respectively) Additionally, the average nitrogen uptake rate of one-year-old bamboo is higher (0.25 mg kg-1 a-1) compared to other age groups. 2) the urea-15N absorption in mixed forests (1066.51–1141.61 g ha-1, including 949.65–1000.07 g ha-1 for bamboo and 116.86–141.54 g ha-1 for trees) was significantly higher than that in pure forests (663.93–727.62 g ha-1, P<0.05). Additionally, the 15N recovery efficiency of culms, branches, leaves, stumps, and stump roots in mixed forests was significantly higher than that in pure forests, with increases of 43.14%, 69.09%, 36.84%, 51.63%, 69.18%, 34.60%, and 26.89%, respectively. 3) the recovery efficiency of urea-15N in mixed forests (45.81%, comprising 40.43% for bamboo and 5.38% for trees) and the residual urea-15N recovery rate in the 0–60 cm soil layer (23.46%) are significantly higher compared to those in pure forests (28.61%/18.89%). This could be attributed to the nitrogen losses in mixed forests (30.73%, including losses from ammonia volatilization, runoff, leaching, and nitrification-denitrification) being significantly lower than those in pure forests (52.50%).

Conclusion: These findings suggest that compared to pure bamboo forests, bamboo in mixed forests exhibits higher nitrogen recovery efficiency, particularly with one-year-old bamboo playing a crucial role.

1 Introduction

Qiongzhuea tumidinoda was one of the two bamboo species listed in the first edition of the “Chinese Rare and Endangered Plants Protection List” published in 1984, designated as a nationally protected plant at the third level. It is indigenous to the southwestern region of China, with its natural distribution confined to a narrow strip along the lower reaches of the Jinsha River in the provinces of Sichuan and Yunnan. There exists a total area of 13900 hectares of natural Q. tumidinoda resources in Daguan County. This area accounts for 59% of the global total area of natural Q. tumidinoda, which amounts to 23560 hectares (Dong, 2019; Wu et al., 2023b). The highly raised nodes on the culms of Q. tumidinoda make it an excellent material for crafting walking sticks, bamboo handicrafts, and round bamboo furniture (Yiyuan et al., 2020; Li et al., 2021). Bamboo shoots from Q. tumidinoda are renowned for their exquisite taste, crisp and tender texture, and delightful sweetness, while also boasting a rich nutritional profile. Consequently, over 90% of products derived from Q. tumidinoda, such as fresh bamboo shoots, dried bamboo shoots and salted bamboo shoots, have consistently enjoyed robust sales in Japan and the Greater China region, encompassing Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan (Dong, 2019; Li et al., 2021).

Q. tumidinoda demonstrates rapid growth, taking just around 50 days from the emergence of bamboo shoots to reaching full height and diameter, enabling the proliferation of numerous new individuals within a span of two months and consuming substantial nutrients (Dong et al., 2002; Wu et al., 2022). Q. tumidinoda forests are primarily managed for bamboo timber and bamboo shoots. With the rapid development of the bamboo industry, the substantial annual harvest of bamboo timber and bamboo shoot biomass inevitably leads to direct removal of a significant amount of nutrients, resulting in the depletion of soil nutrients in bamboo forests (Yang et al., 2012; Li et al., 2024). Furthermore, the slow decomposition of residual rhizomes and stumps left after harvesting in bamboo forests results in a low nutrient return rate (Jiang, 2007; Zheng et al., 2022). Therefore, achieving sustainable high yields in bamboo forests requires nutrient supplementation through fertilization. Among these, nitrogen fertilizer stands as the primary nutrient factor enhancing bamboo forest productivity (Sardar et al., 2023; Zhao and Cai, 2023; Zou et al., 2023). In bamboo forest ecosystems, nitrogen allocation directly influences the growth of bamboo shoots, the development of bamboo culms, and the overall productivity of the stand (Wu et al., 2023a; Zuo et al., 2024).

However, overreliance solely on nitrogen fertilizers can lead to a series of issues such as soil compaction and groundwater contamination, particularly pronounced in monoculture bamboo forests (Tariq et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2023a). To tackle this challenge, strategies involving intercropping broadleaf forests with bamboo stands are frequently employed (Peng et al., 2021). Research indicated that compared to pure forests, mixed forests may have had higher species diversity, leading to potentially more diverse root exudates and leaf litter, further enhancing soil chemical properties such as total nitrogen (Gillespie et al., 2021; Liang et al., 2022). Additionally, studies found differences in microbial diversity and composition between pure and mixed forests, resulting in distinct nitrogen utilization patterns possibly indirectly influenced by pH and differing litter qualities (Wen et al., 2014; Bai et al., 2023). These variances possibly led to higher rates of soil nitrogen mineralization and nitrification in broadleaf trees in mixed forests compared to pure ones, consequently elevating nitrogen concentrations in the soil (Yan et al., 2008; Kong et al., 2020; Yan et al., 2022). Furthermore, broadleaf forests aid in soil moisture retention, providing compensatory ecosystem services to address the limitations of pure bamboo forest ecosystems (Bauhus et al., 2017; Gong et al., 2022). Research has shown that this difference was determined by specific hybrid tree species and hybrid ratios. For instance, Weih et al (Weih et al., 2021). studied the nitrogen utilization patterns of four hybrid willow forests and found that individual species’ functionalities played a determining role. Recent studies on nitrogen in monoculture and mixed forests focused mostly on the distribution patterns of nitrogen in plants, soil or systems, but there was limited research on the fate of nitrogen in monoculture and mixed forests (Voigtlaender et al., 2019; Masuda et al., 2022).

Q. tumidinoda, a small to medium-sized bamboo species, thrives in temperate and humid environments. Lots of research have indicated that mixed forests of Q. tumidinoda with broadleaf trees exhibit superior productivity (Zhang et al., 2020b; Chen et al., 2022), soil quality (Xia et al., 2022; Yuan et al., 2022), species diversity (Yang et al., 2012) and water conservation (Zhong et al., 2020) compared to pure Q. tumidinoda forest. Studies on nitrogen in Q. tumidinoda have mainly focused on soil nitrogen concentration related to its growth (Zhang et al., 2020b; Zhong et al., 2023), whereas research on nitrogen allocation patterns in bamboo and its utilization in different forest types remains unexplored. Simultaneously, to effectively utilize nitrogen, the 15N tracing technique has been widely employed to quantify nitrogen fertilizer uptake, residual amounts, and losses in research. However, few studies have existed regarding the distribution and translocation of urea-15N in different forest types within Q. tumidinoda ecosystems. This study focuses on bamboo and soil from Q. tumidinoda forests and mixed forests of Q. tumidinoda with P. chinense. Utilizing 15N tracing techniques, the objectives are: (1) to compare the partitioning efficiency of applied nitrogen in different organs at various ages between pure forests and mixed forests; (2) to compare the nitrogen recovery and residue rates in bamboo ecosystems between pure forests and mixed forests to determine which type exhibits higher rates.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Site description

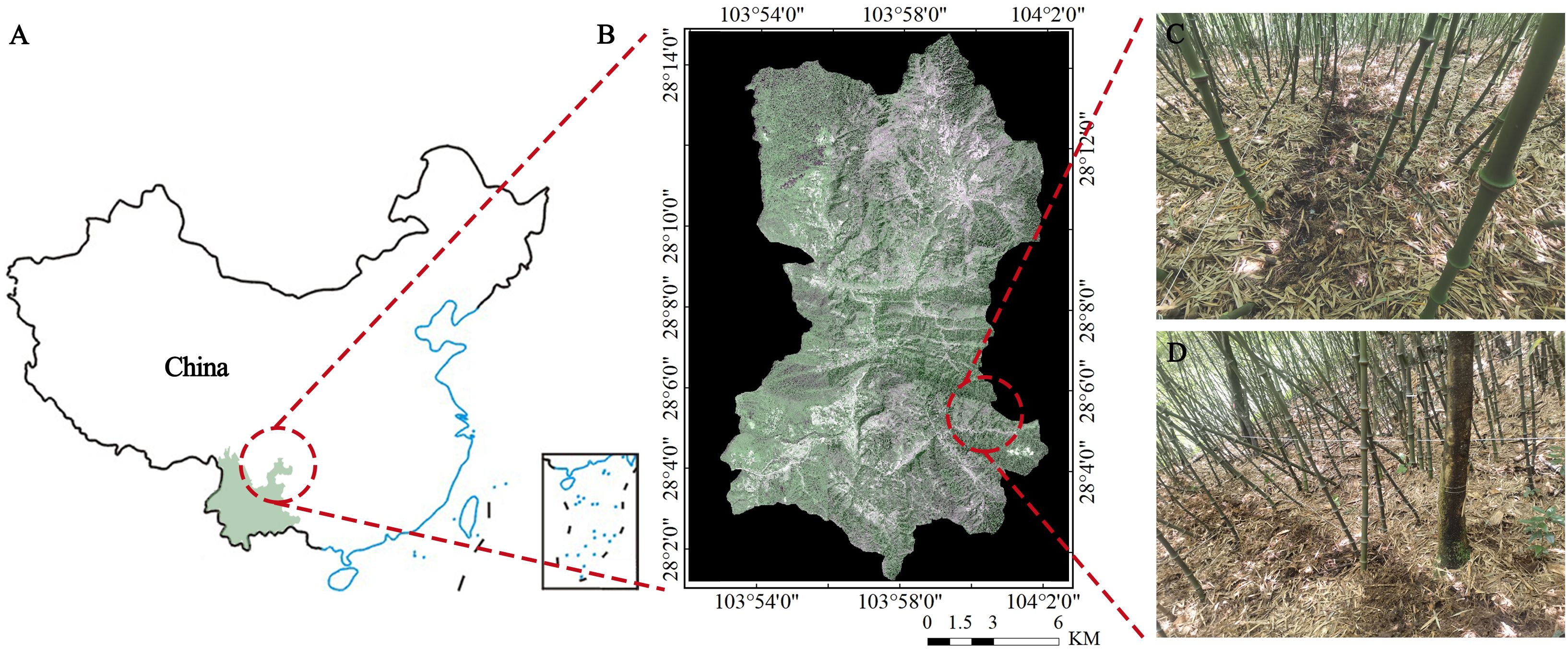

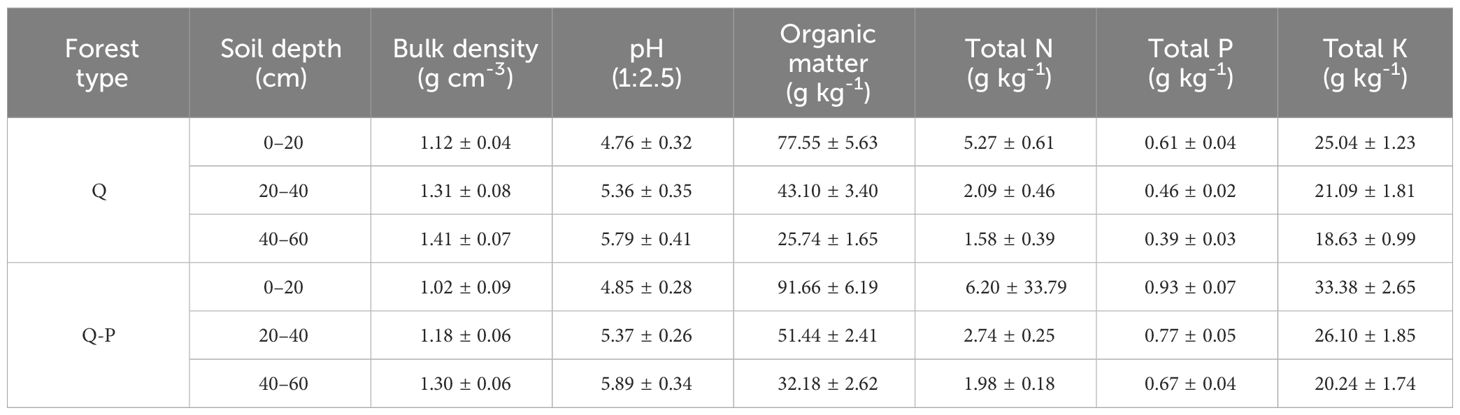

The experimental site is located in Daluohanba, Mugan Town, Daguan County, Yunnan Province, China (Figure 1), the climate condition is the moderate temperate continental climate, with an annual average temperature of 10.5°C, the maximum temperature of 29°C, the lowest temperature of -10°C, annual average precipitation of 1200 mm, annual average evaporation of 1076 mm and relative humidity of 85%. The soils in the research area were a type of yellow-brown forest soil (mostly Inceptisols, United States Soil Taxonomy), originating from basalt with a loam texture. Before the experiment, we measured the soil physical properties of the 0–60 cm soil depth. The soil physicochemical properties were presented in Table 1, soil bulk density was measured by the ring knife method (Qiao et al., 2020). Soil organic matter was determined by the potassium dichromate external heating method (Fan et al., 2016). Soil pH was determined using a pH meter at a soil/water ratio of 1:2.5. Soil total nitrogen (TN) was determined by the appropriate Kjeldahl’s method. soil total phosphorus (TP) and total potassium (TK) were determined by using colorimetrically (ammonium molybdate method) and flame photometer after wet digestion (Bao, 2000).

Figure 1 Geographical location of the research area. (A) China; (B) Daguan County, Zhaotong city; (C, D) Q and Q-P represent a mixed forest of pure Q. tumidinoda and Q. tumidinoda-Phellodendron chinense, respectively.

Table 1 Soil physicochemical properties in soil layer 0–60 cm across various forest types (Mean ± SD).

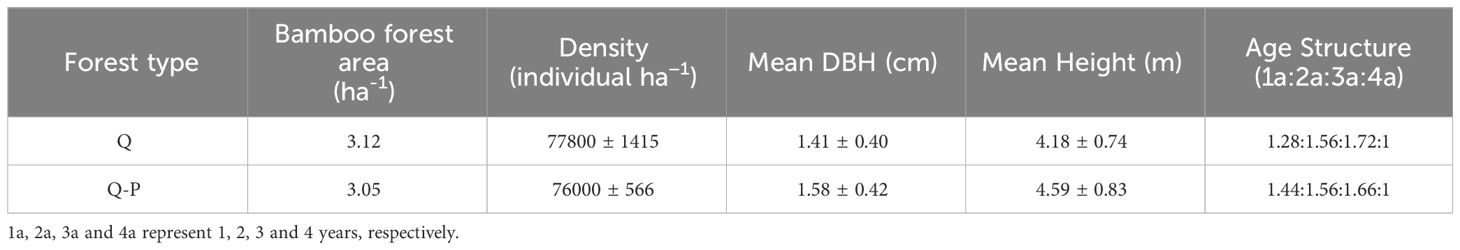

There were two types of forest stands in the study area, Q: Q. tumidinoda pure forest and Q-P: a mixed forest of Q. tumidinoda and artificially planted 1-year-old saplings of Phellodendron chinense. The Q. tumidinoda forest was a natural forest, The P. chinense was planted in September 2012 within the bamboo forest at a density of 400 individuals per hectare, with a spacing of 5m × 5m between plants, an average diameter at breast height (DBH) of 6.12 cm, and an average tree height of 5.50 m. Underneath the forest canopy, there are understory plants including Hydrangea davidii, Smilax china, Elatostema involucratum, Selaginella tamariscina, Achyranthes bidentata, Pilea sinofasciata, and Dryopteris erythrosora and the vegetation cover is approximately 30%.

2.2 Experimental design

The experimental design employed a factorial design with two forest types (Q:28° 5′ N, 104° 0′ E, altitude 1488 - 1512 m a. s. l., slope 21, Q-P:28° 6′ N, 104° 1′ E, altitude 1411 - 1435 m, a. s. l., slope 22°), and two treatments: fertilized and unfertilized. The experimental plots had an area of 400 m2 (20 m × 20 m), replicated three times, with distances larger than 20 m between adjacent plots. Four isolation trenches were excavated around each plot, with a depth of 60 centimeters to sever rhizomes and effectively prevent long-distance nutrient transport. The bamboo in the study area was used for both shoot harvesting and timber production. Before the initiation of the experiment, uniform density control measures were applied to the bamboo forest; however, fertilization management was not implemented. The bamboo stand structures before harvest for the two forest types are presented in Table 2.

Per the previous study (Wang et al., 2022), the experimental fields received a single application of 300 kg ha−1 urea (46% N). Additionally, in each fertilization plot, 200 g of 15N-labeled urea (10.06 atom%, supplied by the Shanghai Research Institute of Chemical Industry) was administered. The fertilization experiment was conducted in August 2022 (Dai et al., 2011), coinciding with the initiation of substantial underground growth in the bamboo, demanding a significant nutrient supply. Furrow application was employed in the trial, consisting of nine fertilizer furrows per plot arranged along contour lines (each furrow measuring 0.2 meters in width, 0.15 meters in depth, spaced 2 meters apart). Before application, all fertilizers were thoroughly mixed and uniformly blended, then applied at the specified depth. To achieve this, initially blend 200 g of 15N-labeled urea with 2 kg of urea evenly, subsequently distribute 10 kg of urea uniformly to a specific depth, sprinkle 2.20 kg of the mixed urea evenly on its surface, turn over and uniformly mix.

2.3 Plant and soil sampling and analyses

In each plot, three bamboo individuals with different ages (1a, 2a, 3a, 4a) and with an average diameter at DBH were selected and harvested, totaling 144 individuals in November 2022. The bamboo was separated into culms, branches, leaves, stumps, and stump roots. The specific procedure was as follows: Firstly, the diameter of each bamboo was measured one by one using a vernier caliper. Next, standard bamboo specimens were selected and cut down, and their heights were measured using a steel tape measure. Subsequently, all leaves and branches were collected, the bamboo culms were segmented and labeled, the stumps were excavated, and allstump roots were collected, cleaned, dried, and labeled. The sampling method for rhizomes and rhizome roots involved placing five randomly selected 1 m × 1 m subplots in an “S” shape within each plot. All culms and culm roots were collected, washed, dried, and labeled, and then their fresh weights were measured in batches. Finally, each organ (rhizomes sampled in appropriate proportions) was taken back to the laboratory, where fresh samples were dried at 105°C, then dried at 70°C to constant weight to determine dry weight and calculate organ biomass. m m Dried samples were ground and sieved through a 0.15 mm mesh screen for 15N analysis.

An Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometer (IsoPrime 100, IsoPrime limited, UK) was employed to analyze the total nitrogen content in all plant and soil samples, the pure abundance of nitrogen in both plant and soil from the unfertilized plot, and the atom percentage of 15N in the fertilized plot.

2.4 Calculation methods

The urea-15N derived percentage (%Ndff) is calculated using Equation 1, while other nitrogen-related indicators are calculated separately using Equations 2–7. (Shi et al., 2012; Su et al., 2019):

In which a is the at% 15N in the unfertilized plant organ or soil, b represents the atom% 15N of the fertilized plant organ or soil, and c is the atom% 15N of the fertilizer.

2.5 Statistical analysis

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed to assess significant distinctions among treatments across all variables throughout the experiment. The Duncan’s multiple range test was utilized for mean separation, and statistical significance was determined at P< 0.05. by SPSS 23.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), while figure creation relied on Origin 8.6 software (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA).

3 Results

3.1 Q. tumidinoda bamboo biomass

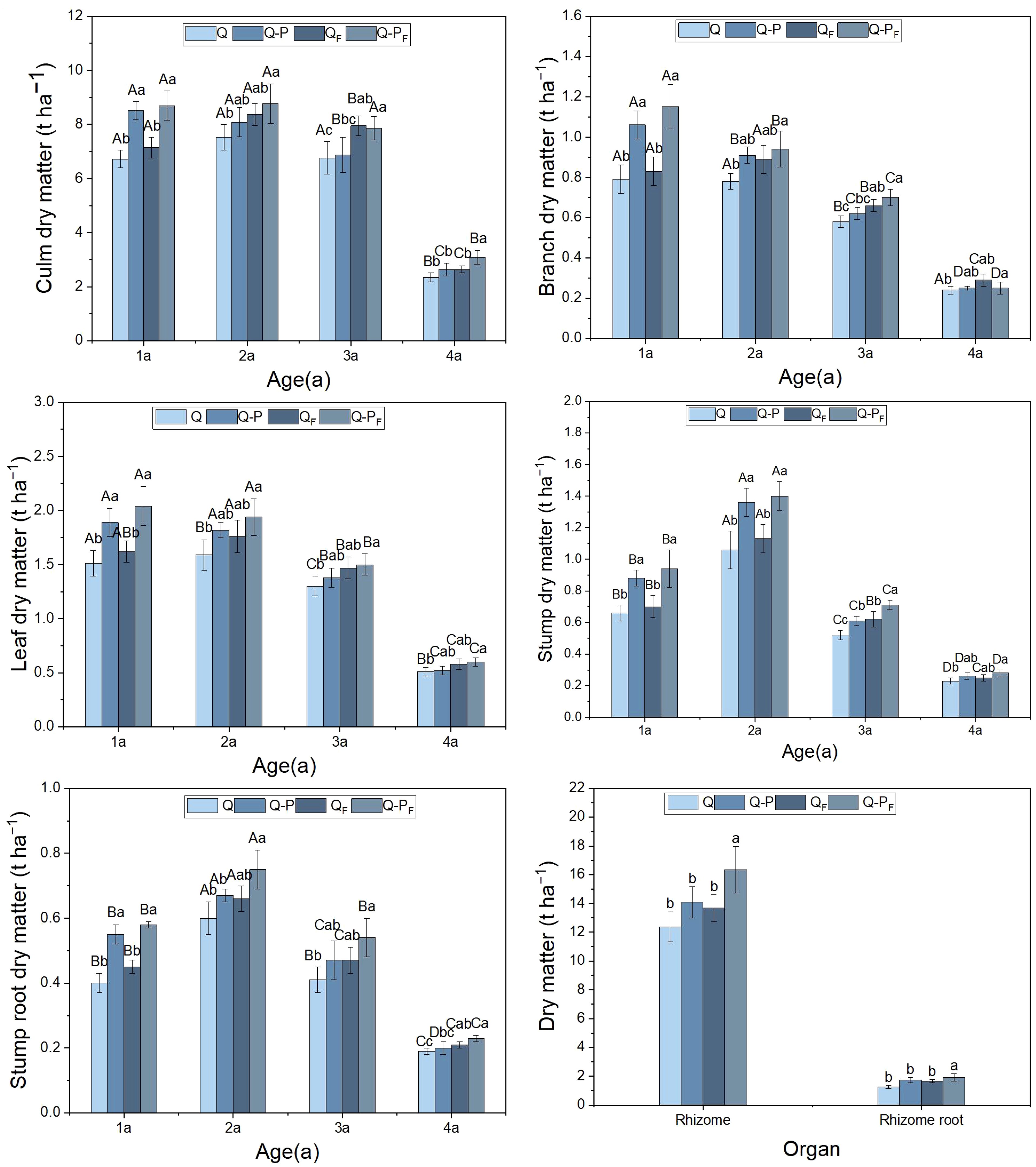

Under fertilization treatment, the biomass of various organs in bamboo of Q-P type at different ages was significantly higher than that of Q type (Figure 2, P< 0.05). This result was similar under no fertilization treatment, but the difference in rhizomes and rhizome roots were not significant (P>0.05). Compared with the unfertilized treatment, under the fertilization treatment, the biomass of various organs in bamboo of different ages of Q-P and Q types increased, but only the difference in rhizomes and rhizome root of Q-P type bamboo reached a significant level. The average proportion of bamboo culm biomass to total biomass was 47.55% (ranging from 42.99% to 49.33%), ranking first. Following that, the rhizomes emerged as the second-highest component, with an average biomass of 14.12 t/ha-1 and peaking at 17.93 t/ha-1 in Q-PF type, with no significant differences observed in other plots (P > 0.05). The aboveground biomass of the bamboo in the four plots (comprising leaves, branches, and culms) exceeded the belowground biomass (including stumps, stump roots, rhizomes, and rhizome roots).

Figure 2 Organ biomass characteristics of Qiongzhuea tumidinoda forests across four types of plots (Mean ± SD). In the first five figures, different uppercase letters in the same sampling site represent significant distinctions between different ages (P< 0.05), and different lowercase letters in the same age indicate significant differences between sampling sites (P< 0.05). In the last figure, different lowercase letters within the same organ indicate significant differences between different plots (P< 0.05).

3.2 N Concentration and N uptake

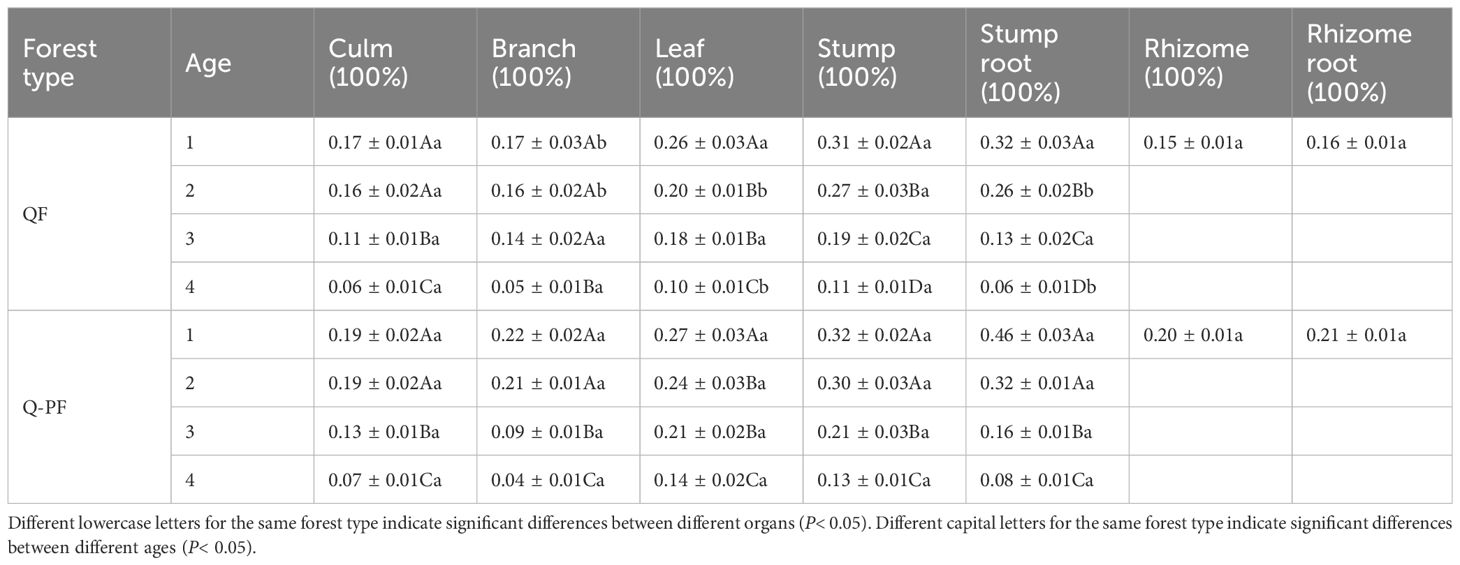

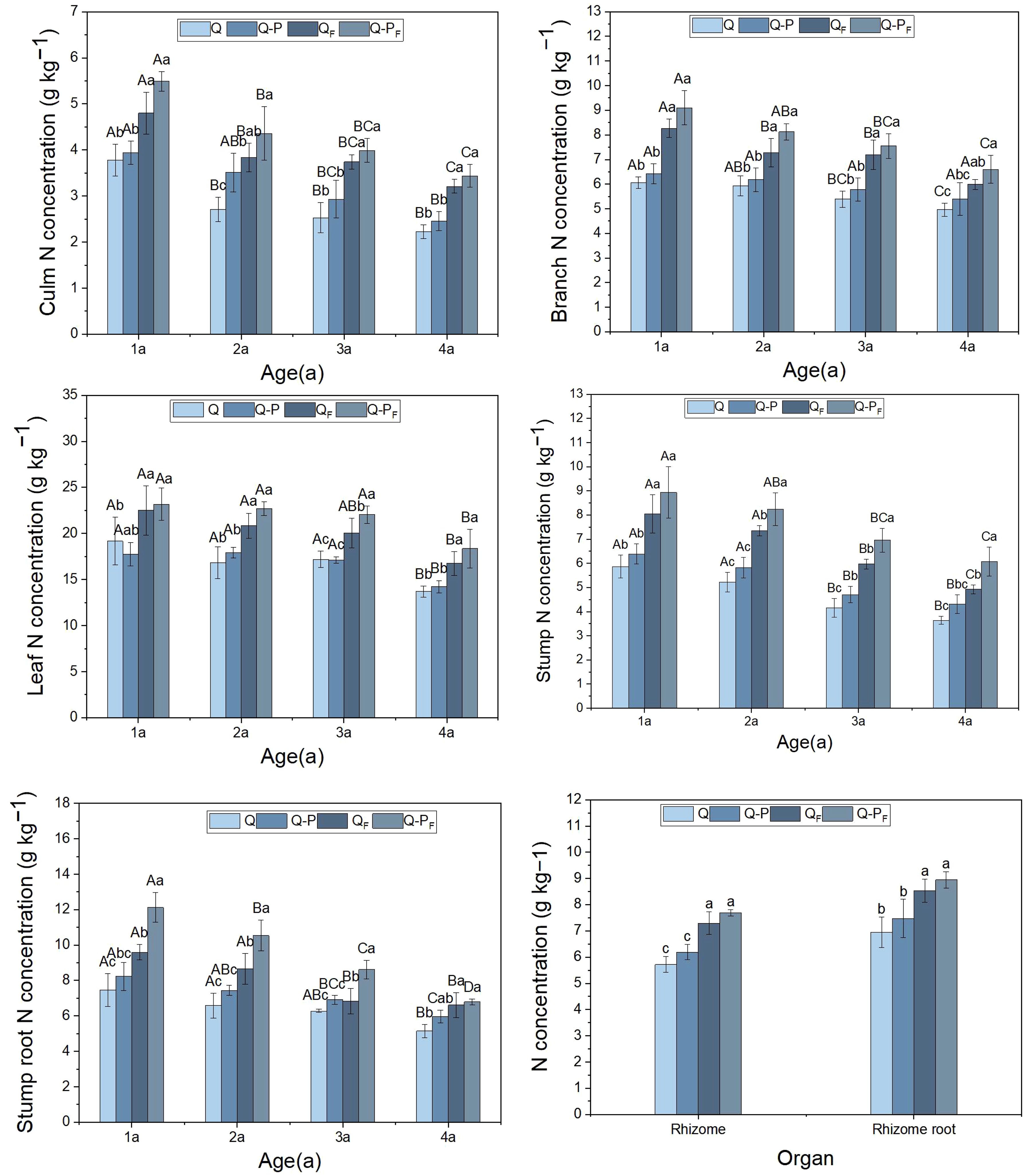

Under the fertilization treatment, the nitrogen concentrations in various organs of different-aged bamboo in the Q. tumidinoda mixed forest (Q-P) were higher than those in the pure Q. tumidinoda forest (Q, Figure 3). This result was similar to the unfertilized treatment, but some organs showed no significant differences (P > 0.05). Compared to the unfertilized treatment, the nitrogen concentrations in various organs of Q-P and Q types significantly increased under the fertilization treatment, with Q-P type (averaging a growth of 41.92%) showing a more pronounced increase than Q type (averaging a growth of 37.23%). Among the types, Q-PF type exhibited the highest concentrations in various organs, followed by QF type. The nitrogen concentrations varied among different organs of Q. tumidinoda, with the leaves of bamboo in all four plots exhibiting significantly higher nitrogen concentrations than other organs, ranging from 13.76 to 27.03 g kg-1. Additionally, the nitrogen concentrations in various organs across the four plots showed a decreasing trend with the increasing age of the bamboo.

Figure 3 Organ nitrogen concentration of Qiongzhuea tumidinoda forests across four types of plots (Mean ± SD). In the first five figures, different uppercase letters in the same sampling site represent significant distinctions between different ages (P< 0.05), and different lowercase letters in the same age indicate significant differences between sampling sites (P< 0.05). In the last figure, different lowercase letters within the same organ indicate significant differences between different sampling plots (P< 0.05).

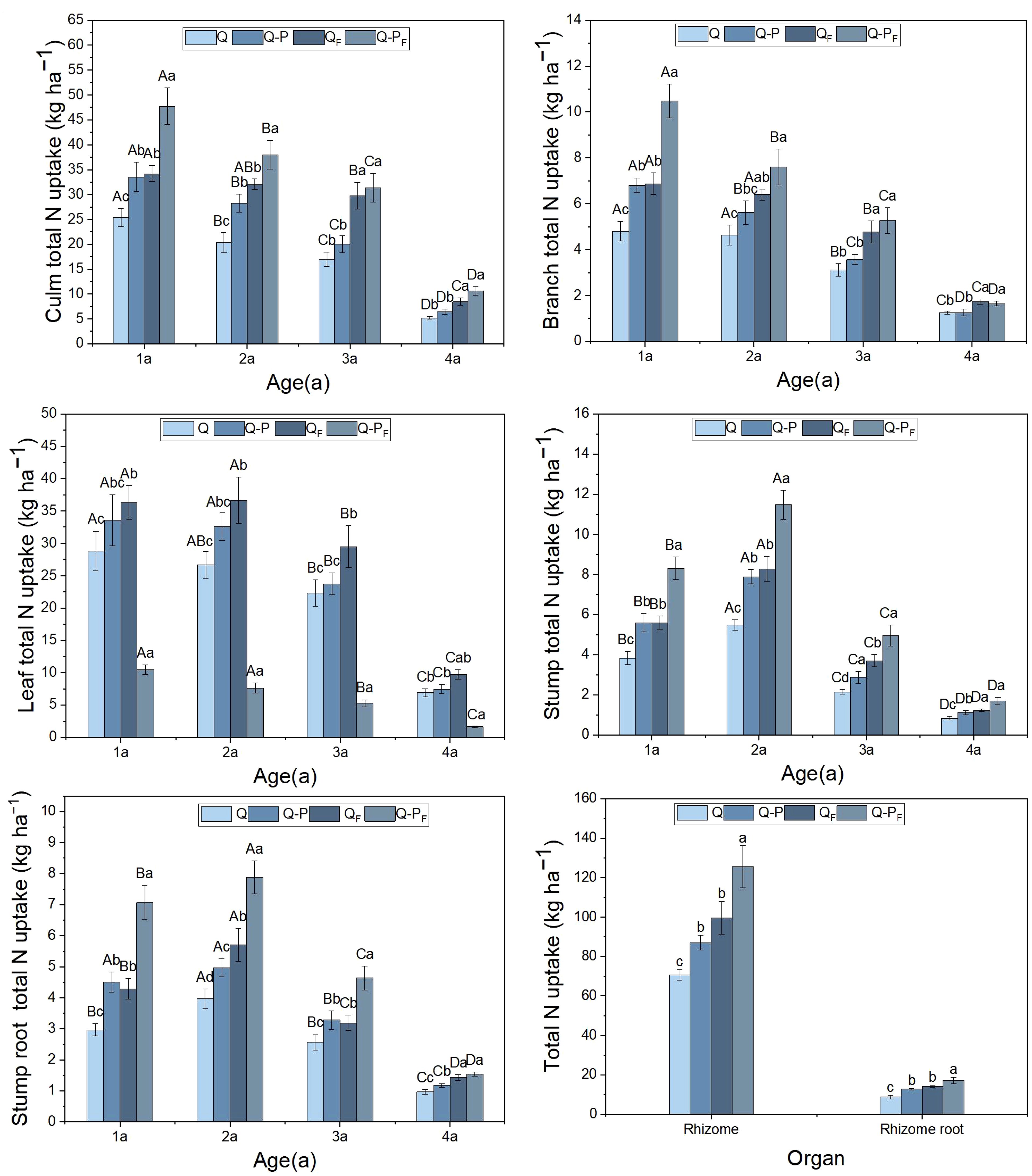

The differences in total nitrogen uptake among various organs of different ages in different types of bamboo were significant (P< 0.05, Figure 4), with all showing higher values for Q. tumidinoda mixed forest (Q-P) compared to pure Q. tumidinoda forest (Q). Compared to the unfertilized treatment, the nitrogen concentrations in various organs of both Q-P and Q types significantly increased under the fertilized treatment. Among them, the Q-P type showed a more pronounced increasing trend (average growth of 45.10%) than Q type (average growth of 42.41%). Nitrogen uptake for each organ (except rhizomes and rhizome roots) decreased with increasing bamboo age. Among these, leaves exhibited the highest total nitrogen uptake, accounting for an average of 29.33% (ranging from 28.31% to 31.52%) of the total uptake, and the aboveground parts showed a 31.52% higher total nitrogen uptake than that of the underground parts (P< 0.05). Q-PF type displayed the highest total nitrogen uptake, reaching up to 478.41 kg ha-1.

Figure 4 Organ nitrogen uptake of Qiongzhuea tumidinoda forests across four types of plots (Mean ± SD). In the first five figures, different uppercase letters in the same plot represent significant distinctions between different ages (P< 0.05), and different lowercase letters in the same age indicate significant differences between plots (P< 0.05). In the last figure, different lowercase letters within the same organ indicate significant differences between different plots (P< 0.05).

3.3 Allocation of urea-15N in various forest types of Q. tumidinoda bamboo forests

Under fertilization, there was no significant difference in Ndff between Q-P and Q types (Table 3). There were significant differences in Ndff among different organs. The average Ndff of stump (0.25%) was the highest, while the average Ndff of branch (0.13%) was similar to that of culm (0.13%), with no significant difference (P > 0.05).

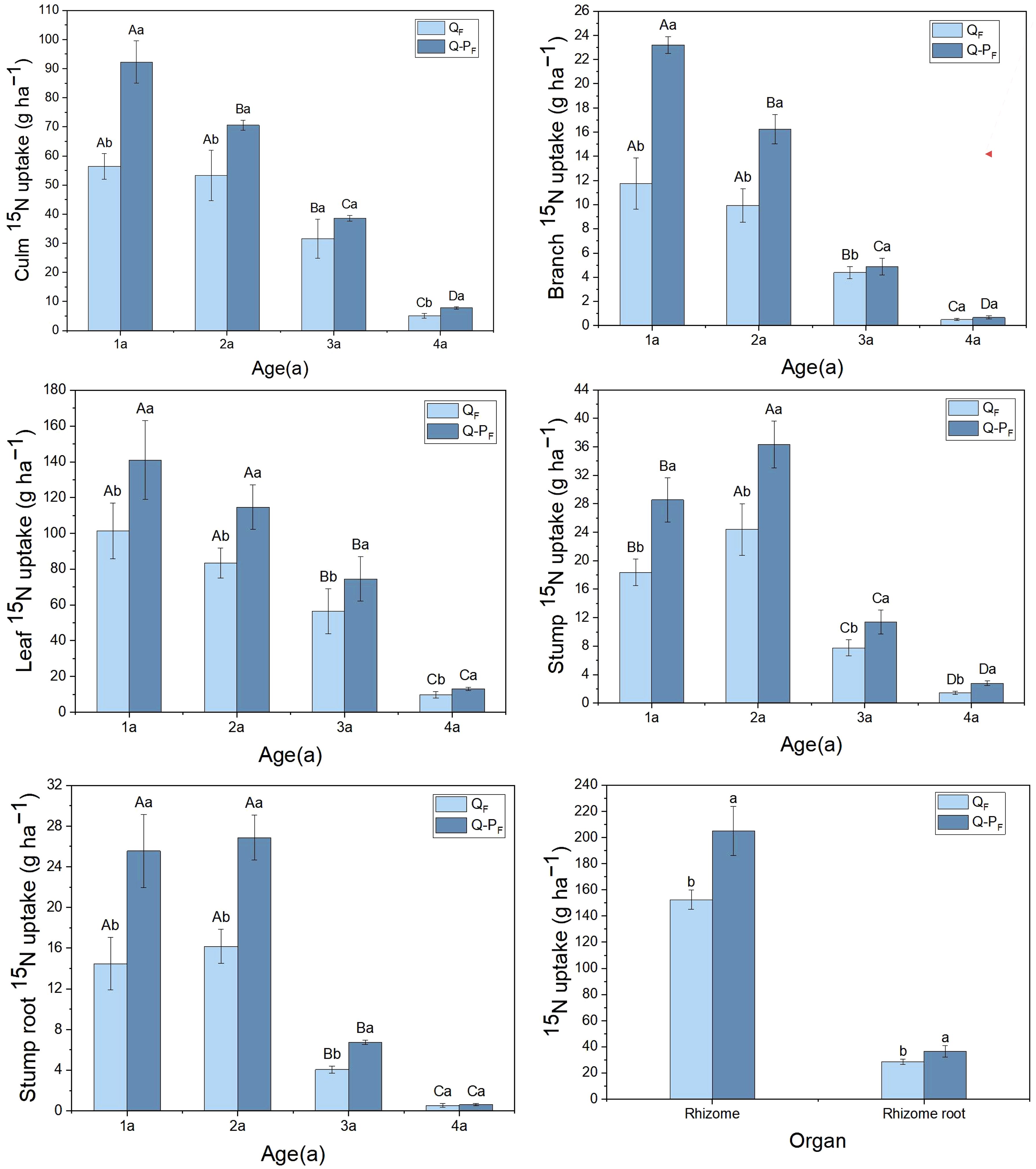

Significant differences were observed in the total 15N uptake among various organs of different types of Q. tumidinoda (Figure 5). The total 15N uptake in organs of Q-P type was notably higher than in Q type (P< 0.05). Except for culms and culm roots, most organs showed a decreasing trend in 15N uptake with increasing bamboo age. The total 15N uptake in leaves was notably higher than in other organs across both forest types, averaging 35.62% of the total uptake, ranging from 32.72% to 38.53%.

Figure 5 15N uptake of Qiongzhuea tumidinoda forests across four types of plots (Mean ± SD). In the first five figures, different uppercase letters in the same plot represent significant distinctions between different ages (P< 0.05), and different lowercase letters in the same age indicate significant differences between plots (P< 0.05). In the last figure, different lowercase letters within the same organ indicate significant differences between different plots (P< 0.05).

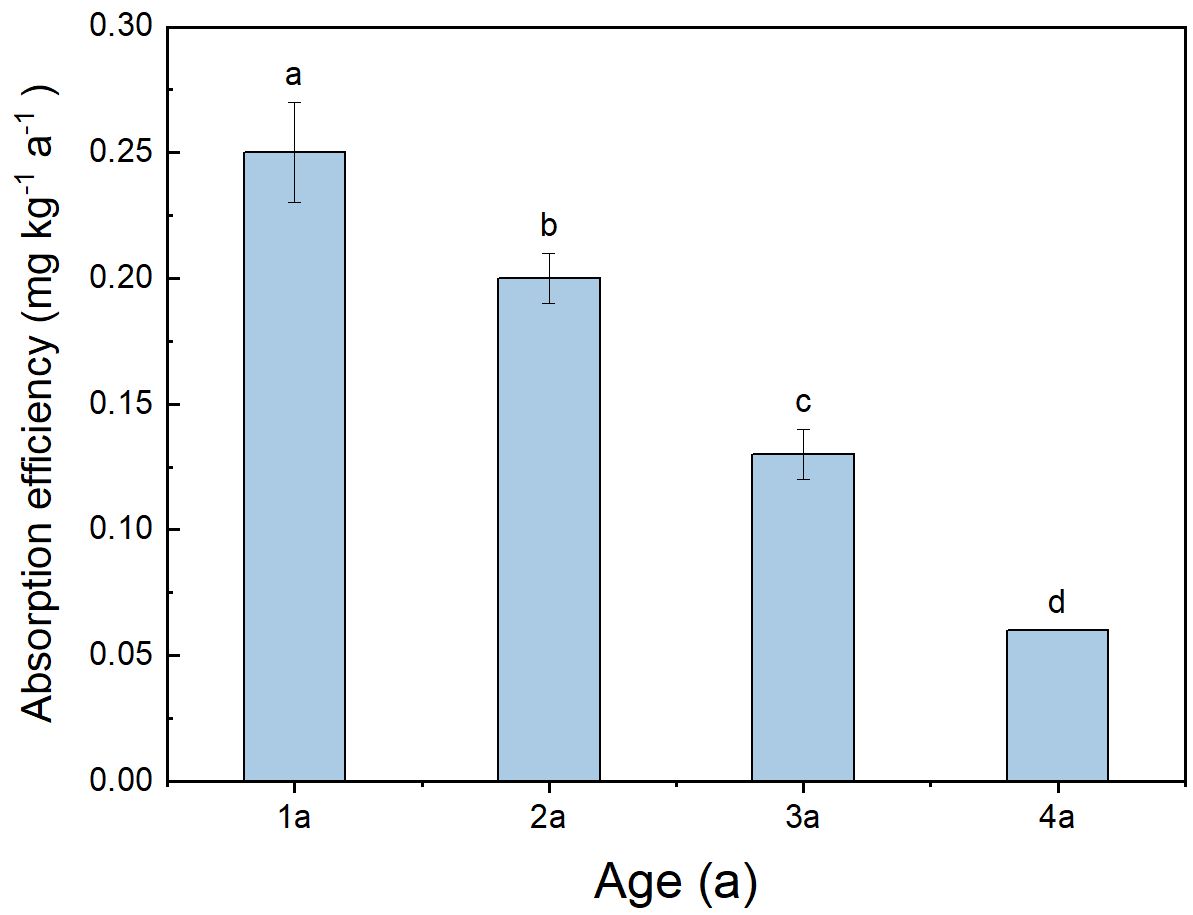

There were significant differences observed in the absorption of 15N among bamboo of different ages (Figure 6), with absorption efficiency gradually decreasing as bamboo aged. The absorption efficiency of 1a bamboo was notably higher than that of other ages, ranging from 0.20 to 0.28 (mean 0.25).

Figure 6 Total absorption efficiency of different ages in Qiongzhuea tumidinoda forests. Different lowercase letters represent significant differences between different ages (P< 0.05).

3.4 Allocation of residual urea-15N in soil

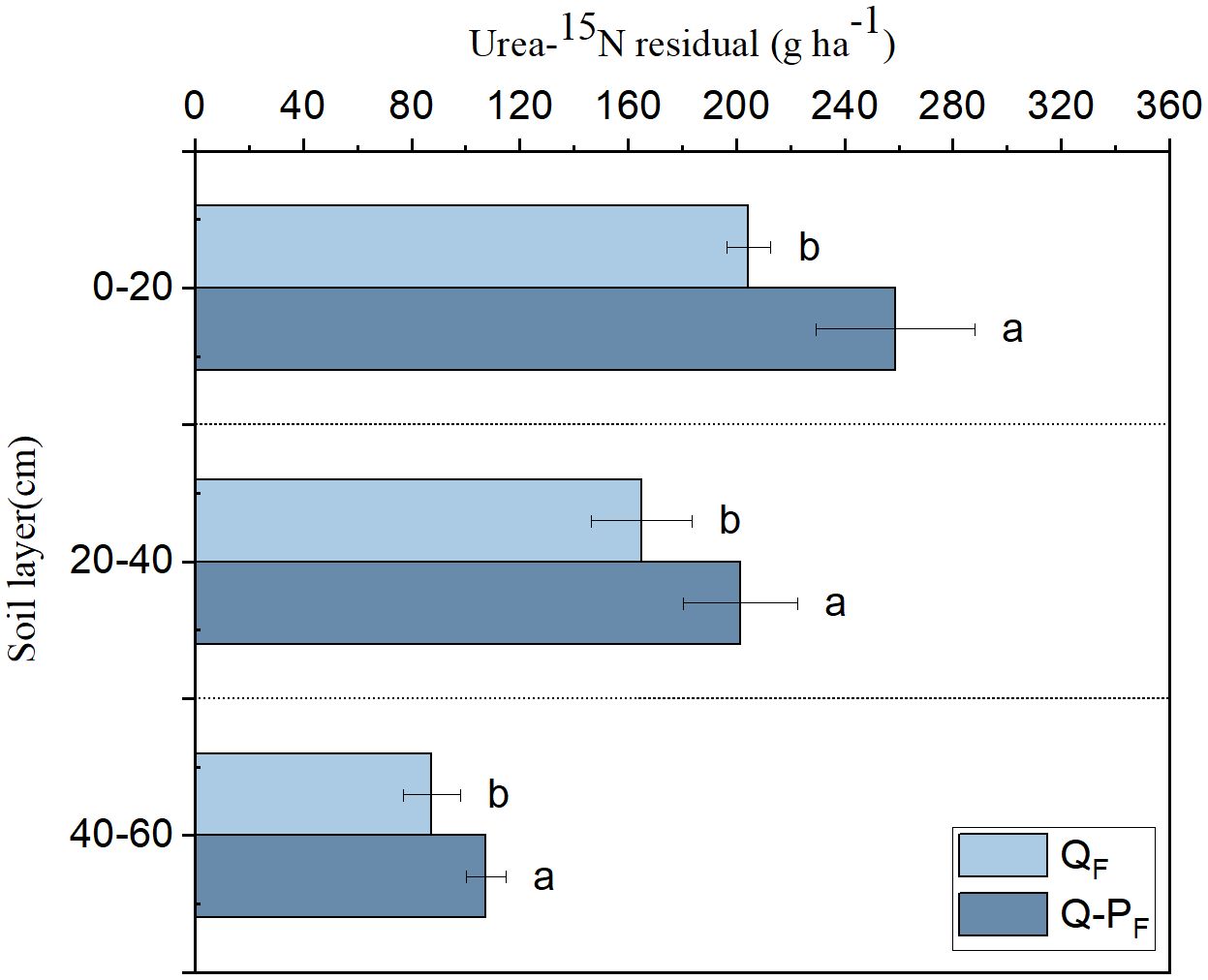

In the same soil layer, Q-P type exhibited significantly higher total residual urea-15N compared to Q type (Figure 7). With increasing soil depth, there was a decreasing trend observed in the total residual urea-15N among different forest types. The majority of residual urea-15N was found in the 0–20 cm soil layer, accounting for 44.86% of the total residual in Q type and 45.56 in Q-P type, respectively.

Figure 7 The distribution of residual urea-15N in the soil. Different lowercase letters of the same soil layer indicate significant differences among different sampling sites at the P< 0.05 level.

3.5 Fate of urea-15N in bamboo-soil system

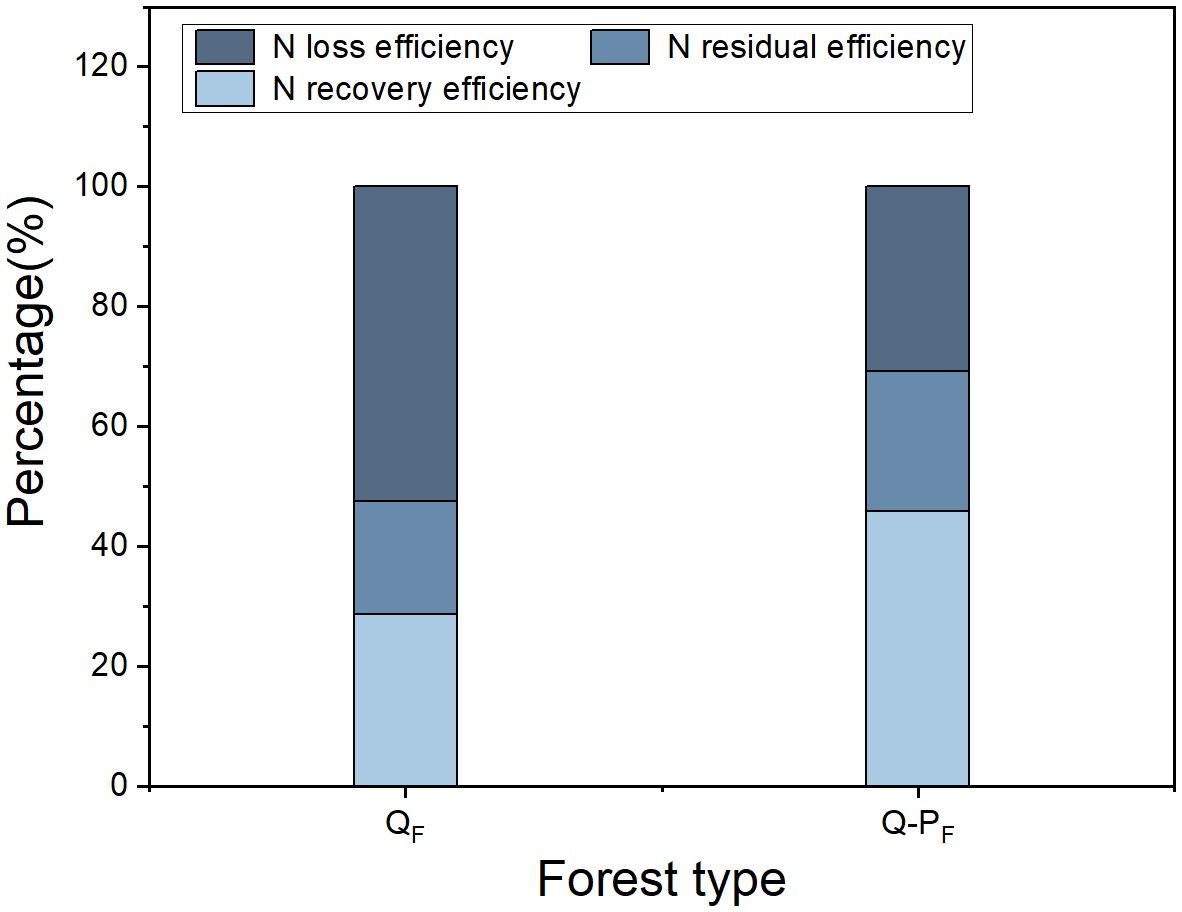

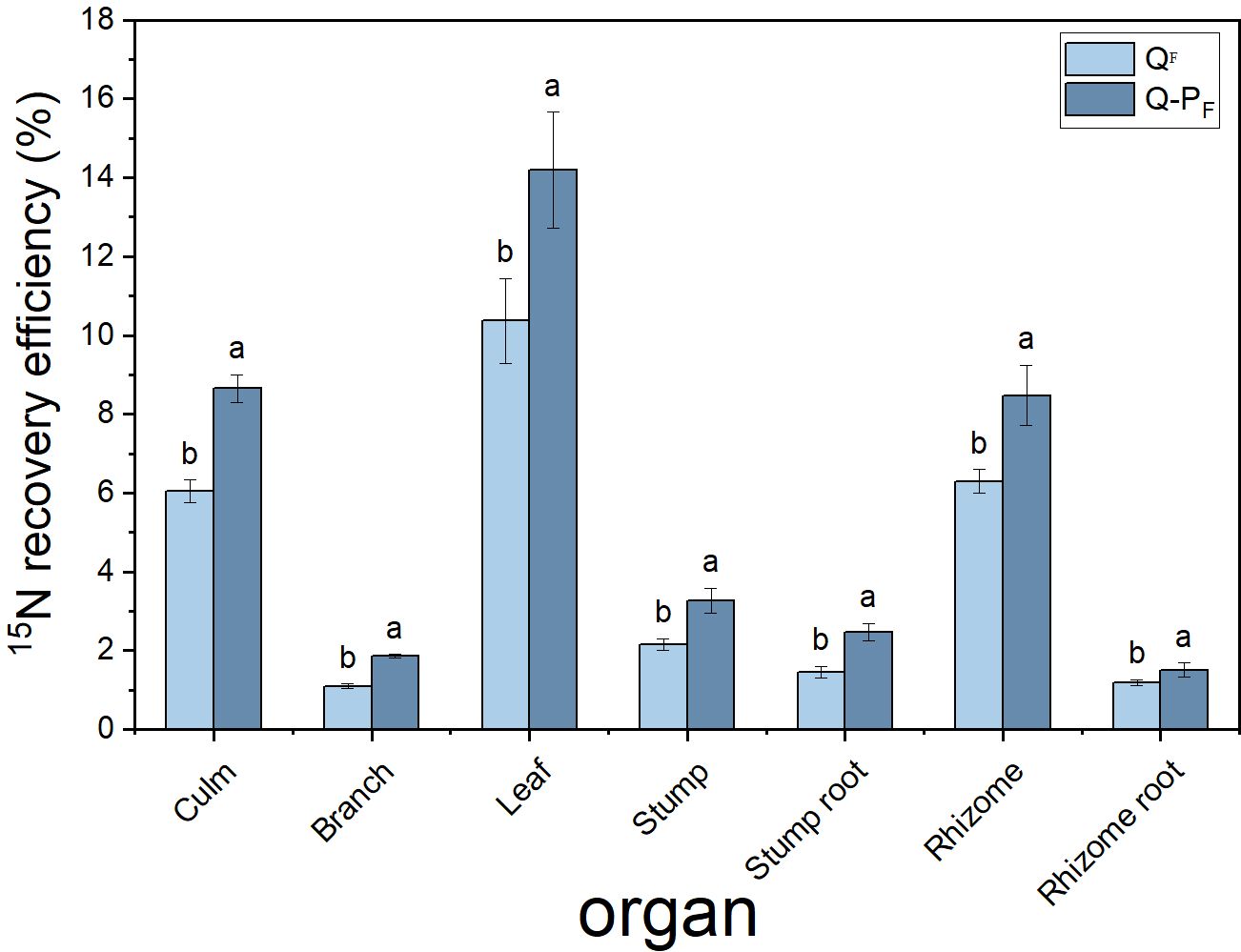

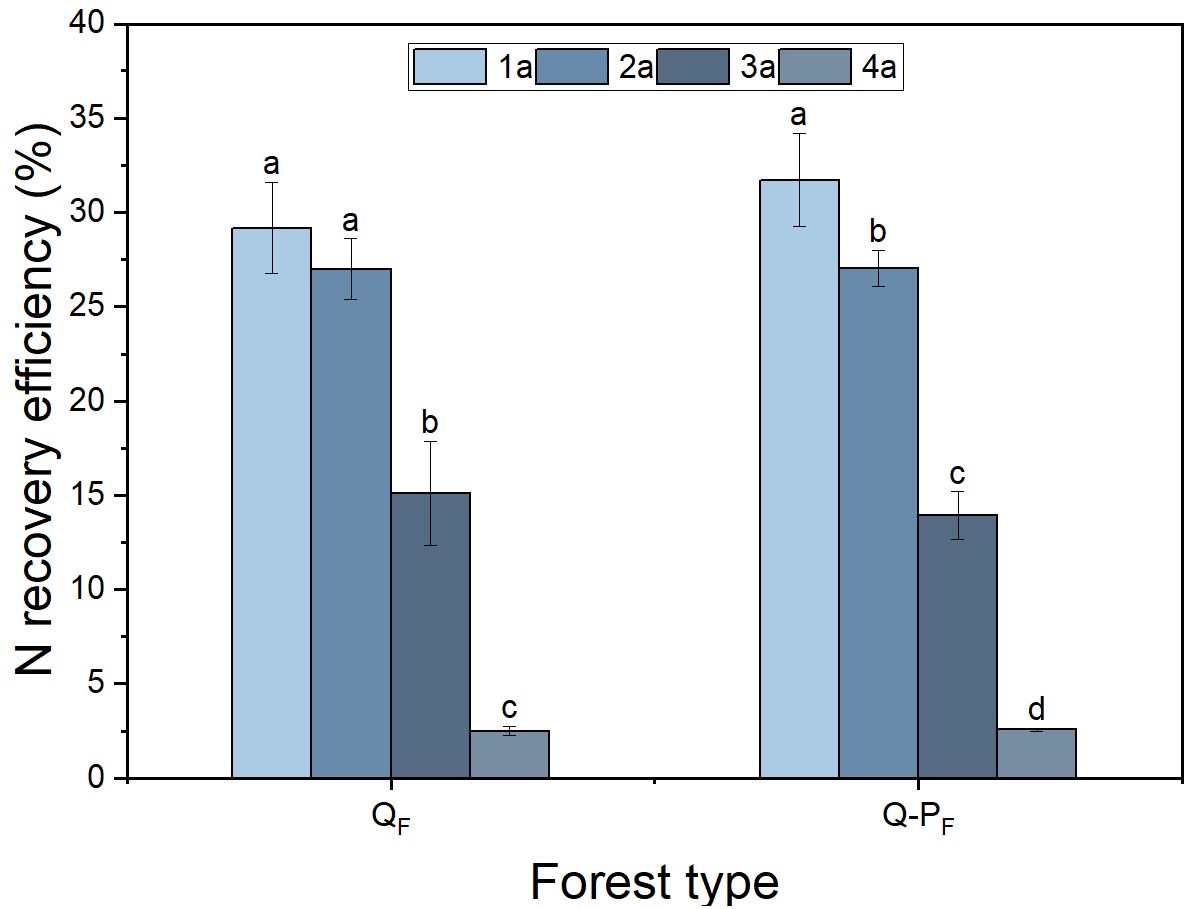

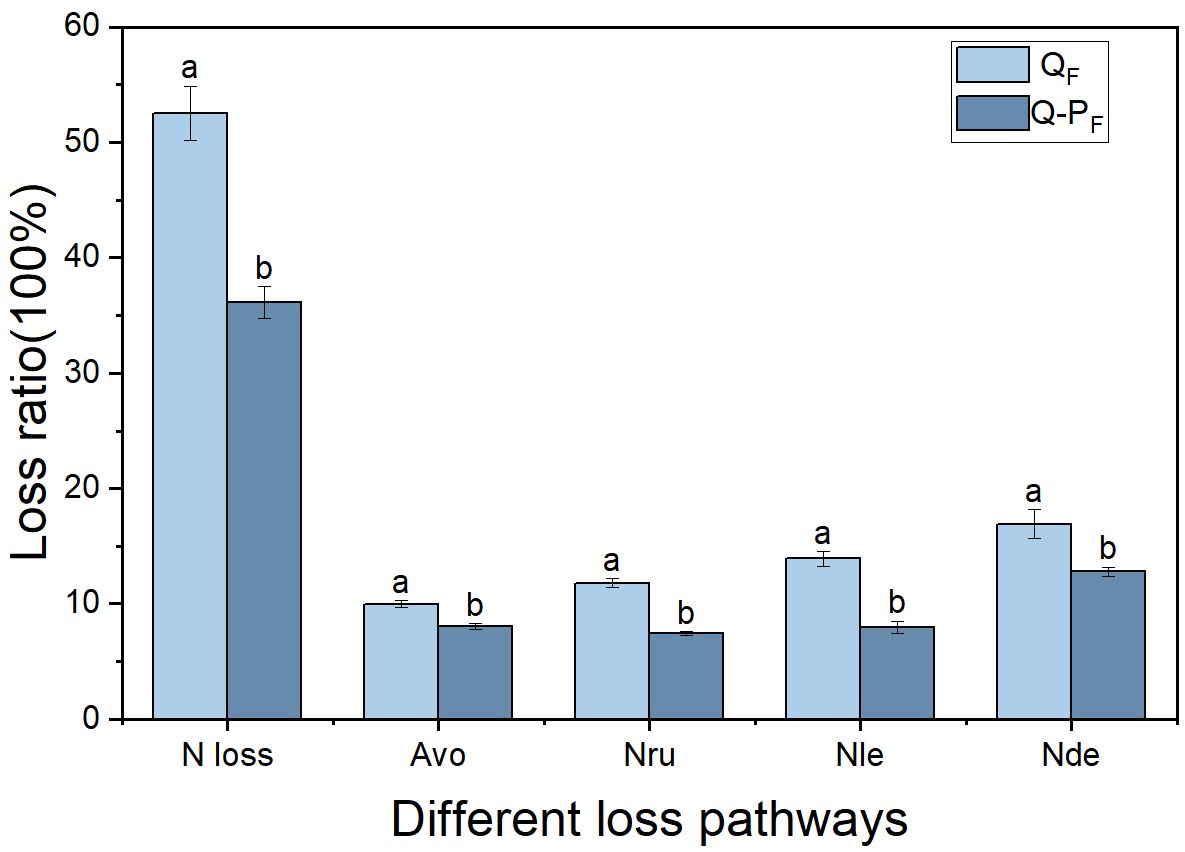

There were significant differences observed in nitrogen recovery efficiency among different forest types, with Q-P type showing significantly higher nitrogen recovery efficiency in various organs compared to Q type. The 15N recovery efficiency of Q-P type culms, branches, leaves, stumps, and stump roots was significantly higher than that of Q type, with increases of 43.14%, 69.09%, 36.84%, 51.63%, 69.18%, 34.60%, and 26.89%, respectively. From an overall perspective, the nitrogen recovery efficiency of leaves averaged at 12.28%, ranging from 9.57% to 15.76%, notably higher than other organs. The culm roots exhibited the lowest recovery efficiency, ranging from 1.18% to 1.52% (Figure 8). The nitrogen recovery efficiency of Q-P and Q types at different ages showed no significant difference, but they exhibited the same pattern. That is, with the aging of bamboo, the nitrogen recovery efficiency significantly decreased (Figure 9). The nitrogen recovery efficiency and residual urea-15N were higher in Q-P type than in Q type, but nitrogen loss rate showed the opposite trend (Figure 10).

Figure 8 Effects of various forest types on 15N recovery efficiency in Qiongzhuea tumidinoda forests. Different lowercase letters within the same organ indicate significant differences between different sampling sites (P< 0.05).

Figure 9 Effects of various forest types on the N recovery efficiency of different ages in Qiongzhuea tumidinoda forests. Different lowercase letters within the same forest type indicate significant differences in nitrogen recycling efficiency among different ages (P< 0.05).

4 Discussion

Bamboo and broadleaved mixed forest is an excellent agricultural forestry model featuring bamboo. Research indicates that in competition with broadleaved trees, bamboo exhibits a greater advantage, possibly owing to its enhanced plasticity and environmental adaptability (Zheng and Lv, 2023). For instance, an experiment on nitrogen uptake conducted with Castanopsis fargesii and moso bamboo revealed that moso bamboo maintained dominance due to its higher tolerance threshold to ammonium nitrogen (Zou et al., 2020). Numerous studies indicated that a beneficial competition was established when bamboo was mixed with an appropriate proportion of broadleaved trees (Cao, 2001; Cheng et al., 2015; Yan et al., 2018). For example, research indicated that when the intercropping ratio of moso bamboo and broadleaved trees was in the range of 20–30%, optimal soil nutrients were achieved, leading to the best growth performance of moso bamboo (Zhang et al., 2020a). Similarly, The intercropping of Q. tumidinoda with other tree species had a certain impact on the growth of the bamboo forest, and the extent of this impact depended on the choice of tree species (Zhou et al., 2016).

Previous research indicated that P. chinense was one of the excellent native tree species for establishing Q. tumidinoda mixed forests. In the mixed forests of P. chinense and Q. tumidinoda, the diameter at breast height, height, and biomass of bamboo were significantly higher than those in pure Q. tumidinoda forests (Zhang et al., 2020b; Chen et al., 2022). This study also confirmed these findings, where the biomass of various parts of Q-P type’s Q. tumidinoda was significantly higher compared to Q type (except for rhizome and rhizome root). However, the difference in underground rhizome-root system (rhizome and rhizome root) between Q-P and Q types was not significant, possibly due to the occupation of certain underground spaces by p. chinense root. In the fertilized treatment, there was a significant difference in the underground rhizome-root system of Q-P type, indicating that compared to Q type, Q-P type’s rhizome-root system absorbed more nitrogen, consequently accumulating more biomass. Furthermore, compared to the unfertilized treatment, the biomass of various bamboo organs in both forest types increased under fertilization, but only the rhizome and rhizome roots reached significant levels, This could be attributed to the relatively high soil temperature and abundant rainfall during this period, which prompts bamboo to primarily focus its growth on the underground parts, accumulating a significant amount of nutrients in its rhizomes and shoots (Chen and Yang, 2003; Zhu et al., 2023).

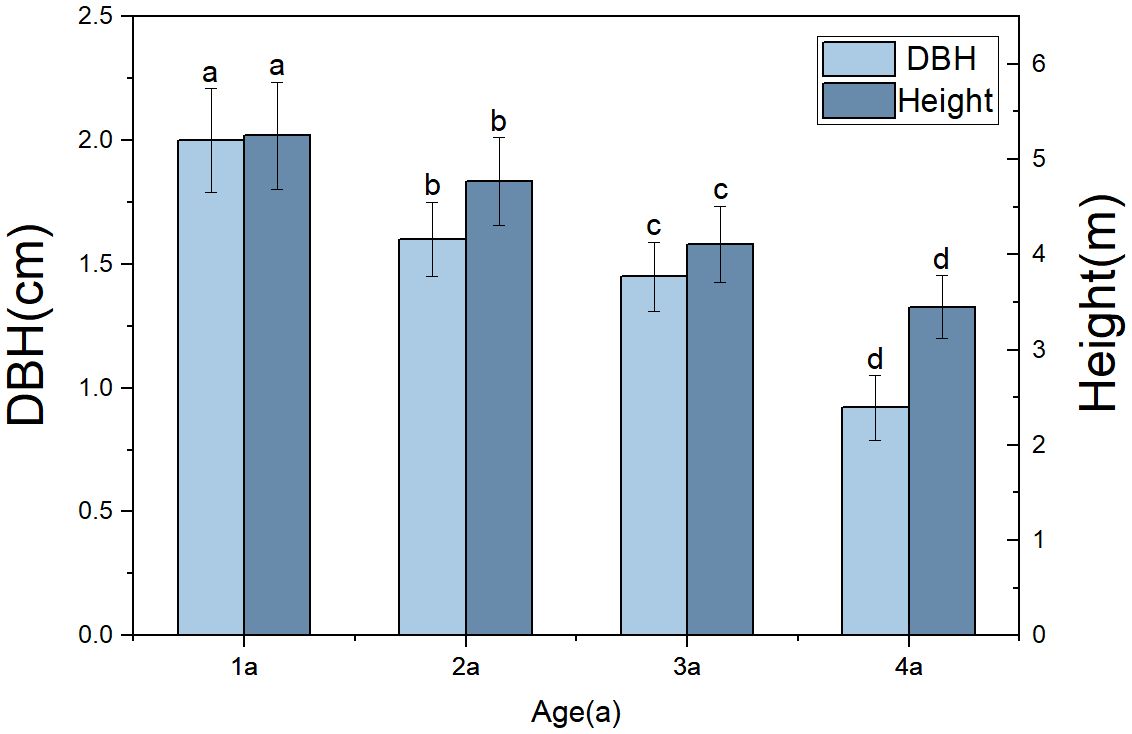

Due to age structure and individual size (Figure 11), the biomass of various organs of the four-year-old bamboo was significantly lower than in other age groups. The biomass of culm was the highest, consistent with previous research findings, accounting for 42.72% of the total biomass as revealed by this study (Chen et al., 2022).

Figure 11 Comparison of Morphological Characteristics of Qiongzhuea tumidinoda in different forest types. The different lowercase letters of columns of the same color representing the height and diameter at breast height at different ages show significant differences (P< 0.05), respectively.

Following fertilization, both the nitrogen concentration and uptake in various organs of Q-P type were significantly higher than in Q type, further emphasizing Q-P type’s greater nitrogen absorption. The leaves exhibited the highest nitrogen concentration and uptake, likely attributed to their photosynthetic activity. Despite the culms having the largest biomass, their nitrogen absorption was lower due to their comparatively lower nitrogen concentration.

In bamboo forest ecosystems, nitrogen fertilizer is primarily utilized in three ways: uptake by bamboo, retention within the soil, or loss from the bamboo-soil system (Chalk et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2023b). Currently, the use of 15N isotope tracing technology is considered the optimal method for studying nitrogen fertilizer utilization efficiency and nitrogen balance in bamboo forest ecosystems (Haque et al., 2022). This technique, employing labeled 15N fertilizers, enables direct or indirect determination of nitrogen recovery by bamboo, residual fertilizer levels in the soil, and nitrogen loss rates (Raymond et al., 2016; Su et al., 2019). In this study, 15N distribution varied among different types of Q. tumidinoda forests, yet the overall allocation pattern remained largely consistent. A range of 32.72% to 38.53% of the total 15N absorption was allocated to the leaves, representing the highest proportion. Following this, the branches accounted for 19.06% to 23.89% of the total 15N absorption. This alignment with the distribution of 26.90% to 37.21% of total 15N absorption in the leaves in Moso bamboo forests. However, discrepancies in the overall 15N absorption distribution were evident among different Q. tumidinoda forests. For instance, in Moso bamboo forests, bamboo stump ranked second (Su et al., 2019), indicating variations possibly attributed to different bamboo species. Based on previous studies, the residual amount and downward movement of nitrogen fertilizer can be reflected by the concentration of 15N in the soil layers (Wang et al., 2011; Jing et al., 2020). The average residual amount of 15N-labeled urea in the 0–60 cm soil layer of Q-P type was 567.73 g ha-1, accounting for 23.46% of the total applied 15N. It was significantly higher in all soil layers compared to Q type, correlating with the soil organic matter content. Research has shown that nitrogen becomes immobilized within soil organic matter (Mostafa et al., 2020). In this study, the participation of p. chinense ‘s litter in decomposition led to higher organic matter content in all soil layers of Q-P type compared to Q type, consequently immobilizing more nitrogen. The residual 15N in both forest types exhibited a decreasing trend with increasing soil depth, consistent with previous reports (Ru et al., 2020; Nguyen et al., 2021; Effah et al., 2022).

It is well-known that ammonia volatilization, nitrification-denitrification, runoff, and leaching are the primary pathways for nitrogen loss (Räbiger et al., 2020; Shi et al., 2020; Lan et al., 2022). In this study, it was found that the nitrogen recovery efficiency and soil nitrogen residual efficiency of the mixed forest (Q-P) were significantly higher than those of the pure forest (Q), which may be attributed to the differences in nitrogen loss between them. All types of nitrogen loss pathways in the Q-P type (including ammonia volatilization, runoff, leaching, and nitrification-denitrification) were significantly higher than those in the Q type (Figure 12). This conclusion can be inferred from previous studies. For instance, research has indicated that compared to pure bamboo forests, the canopy of mixed bamboo and broadleaf tree forests provides effective shading, thus reducing ammonia volatilization (Cheng et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2020a). Additionally, the canopy interception by broadleaf trees in mixed forests, along with the impact of their litter and root systems on soil and water conservation (Zhang et al., 2020a; Nainar et al., 2021; Ding et al., 2023), results in lower nitrogen losses from runoff and leaching compared to pure forests. Apart from differences in nitrogen loss, the Q-P type exhibited two distinct nitrogen recovery pathways: the recovery rate of 15N from P. chinense (5.37%, Table 4) and the recovery rate of 15N from bamboo (40.43%). Compared to the single forest type of Q type, Q-P type more efficiently utilized the abundant nitrogen resources.

Figure 12 Comparison of nitrogen loss rates through various pathways of Qiongzhuea tumidinoda in different forest types. Different lowercase letters within the same forest type indicate significant differences in nitrogen loss rates through different nitrogen loss pathways (P< 0.05), respectively. Avo, ammonia volatilization; Nru, nitrogen runoff; Nle, nitrogen leaching; Nde, nitrification-denitrification.

Table 4 Biomass allocation characteristics and nitrogen fate of phellodendron chinense forests in Q-P (Mean ± SD).

In this study, the mean nitrogen recovery rate for both bamboo forest systems was 37.21%, significantly higher than the nitrogen recovery rate determined by Su et al (Su et al., 2019). in fertilized Moso bamboo forests (28.98%). These findings differed from the recovery rate of fertilization in Moso bamboo forests reported by Mao et al (Mao et al., 2016). (13.96%). This discrepancy could potentially stem from variations in bamboo biological characteristics, timing, and dosage of fertilizer applications. Therefore, further experiments are needed to validate the specific reasons.

5 Conclusions

In this study, it was clearly indicated that there are significant differences in the fate and distribution ratios of nitrogen labeled urea applied in different types of bamboo forest ecosystems. The bamboo forest with mixed P. chinense and Q. tumidinoda exhibited notably higher nitrogen recovery and soil residue compared to the pure Q. tumidinoda forest, while showing an opposite trend in nitrogen loss rate. In these two types of bamboo forests, despite the largest biomass being in the bamboo culms, the leaves exhibited the highest nitrogen absorption and content. The residual 15N was primarily concentrated in the fertilized layer. These studies indicate that the proportion of trees to bamboo in this experimental design may fall within an appropriate range of mixed cropping ratios, thereby enhancing the nitrogen recovery efficiency of bamboo and reducing nitrogen loss efficiency. However, the competitive relationship between trees and bamboo cannot be ignored. Therefore, we hypothesize that increasing or decreasing the proportion of trees in bamboo forests may have similar or opposite effects on the nitrogen cycle of bamboo, which requires further experimental support. Additionally, the impact of different types of mixed tree species on bamboo may vary, especially the intercropping of nitrogen-fixing tree species with bamboo, which will be the focus of future research.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

YW: Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Methodology. WD: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. HZ: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. JD: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. WL: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft. CP: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. XL: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. ZX: Project administration, Resources, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by Forestry science and technology promotion demonstration project of central finance ([2019] tg14), Jiangsu postgraduate scientific research innovation program (NO.KYCX21-0925).

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to the Forestry and Grassland Bureau of Daguan County, and Guang-you XIE for their support in providing the field site. We also appreciate the partial experimental support from the Yunnan Biodiversity Research Institute at Southwest Forestry University.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Bai, Y., Wei, H., Ming, A., Shu, W., Shen, W. (2023). Tree species mixing begets admixture of soil microbial communities: Variations along bulk soil, rhizosphere soil and root tissue. Geoderma 438, 116638. doi: 10.1016/j.geoderma.2023.116638

Bauhus, J., Forrester, D. I., Gardiner, B., Jactel, H., Vallejo, R., Pretzsch, H. (2017). “Ecological stability of mixed-species forests,” in Mixed-Species Forests: Ecology and Management. Eds. Pretzsch, H., Forrester, D. I., Bauhus, J. (Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg), 337–382. doi: 10.1007/978–3-662–54553-9_7

Cao, K.-F. (2001). Morphology and growth of deciduous and evergreen broad-leaved saplings under different light conditions in a Chinese beech forest with dense bamboo undergrowth: Morphology and growth of saplings. Ecol. Res. 16, 509–517. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1703.2001.00413.x

Chalk, P. M., Craswell, E. T., Polidoro, J. C., Chen, D. (2015). Fate and efficiency of 15N-labelled slow-and controlled-release fertilizers. Nutr. Cycl Agroecosyst. 102, 167–178. doi: 10.1007/s10705-015-9697-2

Chen, S., Yang, Q. (2003). Review on the influence of underground rhizome system growth factors of monopodial bamboo. Forestry Res. 16 (4), 473–478. doi: 10.13275/j.cnki.lykxyj

Chen, X., Dong, W. Y., Zhong, H., Yuan, L. L., Xia, L., Huang, X. D., et al. (2022). Construction of aboveground biomass model of Qiongzhuea tumidinoda in artificial mixed forest with Phellodendri chinensis. World Bamboo Rattan 20, 23–28. doi: 10.12168/sjzttx.2022.02.005

Cheng, X., Shi, P., Hui, C., Wang, F., Liu, G., Li, B. (2015). An optimal proportion of mixing broad-leaved forest for enhancing the effective productivity of moso bamboo. Ecol. Evol. 5, 1576–1584. doi: 10.1002/ece3.1446

Dai, X., Wang, L., Tang, J., Huang, L. J. (2011). Research advance of biology of qiongzhuea tumidinod. World Bamboo Rattan 9, 34–36. doi: 10.13640/j.cnki.wbr.2011.05.014

Ding, N., Bai, Y., Zhou, Y. (2023). Tree species mixtures can improve the water storage of the litter–soil continuum in subtropical coniferous plantations in China. Forests 14, 431. doi: 10.3390/f14020431

Dong, W. Y. (2019). Some insights on bamboo resources and their industrialization at county level. For. resource Manage. 6, 17–22. doi: 10.13466/j.cnki.lyzygl.2019.06.004

Dong, W. Y., Huang, B. L., Xie, Z. X., Xie, Z. H., Liu, H. Y. (2002). Studies on the structure and dynamics of biomass of Qiongzhuea tumidinod clone population. For. Res. 15, 416–420. doi: 10.13275/j.cnki.lykxyj.2002.04.009

Effah, Z., Li, L., Xie, J., Karikari, B., Wang, J., Zeng, M., et al. (2022). Post-anthesis relationships between nitrogen isotope discrimination and yield of spring wheat under different nitrogen levels. Front. Plant Sci. 13. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.859655

Fan, S., Guan, F., Xu, X., Forrester, D. I., Ma, W., Tang, X. (2016). Ecosystem carbon stock loss after land use change in subtropical forests in China. Forests 7, 142. doi: 10.3390/f7070142

Gillespie, L. M., Hättenschwiler, S., Milcu, A., Wambsganss, J., Shihan, A., Fromin, N. (2021). Tree species mixing affects soil microbial functioning indirectly via root and litter traits and soil parameters in European forests. Funct. Ecol. 35, 2190–2204. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.13877

Gong, C., Tan, Q., Liu, B., Xu, M. (2022). Impacts of mixed forests on controlling soil erosion in China. CATENA 213, 106147. doi: 10.1016/j.catena.2022.106147

Haque, A. N. A., Uddin, M. K., Sulaiman, M. F., Amin, A. M., Hossain, M., Solaiman, Z. M., et al. (2022). Combined use of biochar with 15Nitrogen labelled urea increases rice yield, N use efficiency and fertilizer N recovery under water-saving irrigation. Sustainability 14, 7622. doi: 10.3390/su14137622

Jing, B., Niu, N., Zhang, W., Wang, J., Diao, M. (2020). 15N tracer-based analysis of fertilizer nitrogen accumulation, utilization and distribution in processing tomato at different growth stages. Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica Section B — Soil Plant Sci. 70, 620–627. doi: 10.1080/09064710.2020.1825786

Kong, Y., Ma, N. L., Yang, X., Lai, Y., Feng, Z., Shao, X., et al. (2020). Examining CO2 and N2O pollution and reduction from forestry application of pure and mixture forest. Environ. pollut. 265, 114951. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114951

Lan, T., Huang, Y., Song, X., Deng, O., Zhou, W., Luo, L., et al. (2022). Biological nitrification inhibitor co-application with urease inhibitor or biochar yield different synergistic interaction effects on NH3 volatilization, N leachingand, and N use efficiency in a calcareous soil under rice cropping. Environ. pollut. 293, 118499. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2021.118499

Li, S., Yang, S., Shang, L., Liu, X., Ma, J., Ma, Q., et al. (2021). 3D visualization of bamboo node’s vascular bundle. Forests 12, 1799. doi: 10.3390/f12121799

Li, Z., Guan, F., Zhou, X., Liu, L., Fu, D., Zhang, X., et al. (2024). Effect of fertilization on soil fertility and individual stand biomass in strip cut moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) forests. Forests 15, 252. doi: 10.3390/f15020252

Liang, C., Liu, L., Zhang, Z., Ze, S., Ji, M., Li, Z., et al. (2022). Do mixed pinus yunnanensis plantations improve soil’s physicochemical properties and enzyme activities? Diversity 14, 214. doi: 10.3390/d14030214

Mao, C., Qi, L. H., Liu, Q. R., Song, X. Z., Zhang, Y. (2016). The distribution and use efficiency of nitrogen in phyllostachys edulis forest. Scientia Silvae sinicae 52, 64–70. doi: 10.11707/j.1001–7488.20160508

Masuda, C., Morikawa, Y., Masaka, K., Koga, W., Suzuki, M., Hayashi, S., et al. (2022). Hardwood mixture increases stand productivity through increasing the amount of leaf nitrogen and modifying biomass allocation in a conifer plantation. For. Ecol. Manage. 504, 119835. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2021.119835

Mostafa, M., Karim, S., Nahid, K., Meisam, R. (2020). The influence of organic amendment source on carbon and nitrogen mineralization in different soils | Journal of soil science and plant nutrition. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 20, 171–791. doi: 10.1007/s42729–019-00116-w

Nainar, A., Kishimoto, K., Takahashi, K., Gomyo, M., Kuraji, K. (2021). How do ground litter and canopy regulate surface runoff?—A paired-plot investigation after 80 years of broadleaf forest regeneration. Water 13, 1205. doi: 10.3390/w13091205

Nguyen, D. H., Grace, P. R., Rowlings, D. W., Biala, J., Scheer, C. (2021). The fate of urea 15N in a subtropical rain-fed maize system: influence of organic amendments. Soil Res. 60, 252–261. doi: 10.1071/SR21101

Peng, C., Song, Y., Li, C., Mei, T., Wu, Z., Shi, Y., et al. (2021). Growing in mixed stands increased leaf photosynthesis and physiological stress resistance in moso bamboo and mature chinese fir plantations. Front. Plant Sci. 12. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.649204

Qiao, Y., Zhu, H., Zhong, H., Li, Y. (2020). Stratified data reconstruction and spatial pattern analyses of soil bulk density in the northern grasslands of China. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Information 9, 682. doi: 10.3390/ijgi9110682

Raymond, J. E., Fox, T. R., Strahm, B. D. (2016). Understanding the fate of applied nitrogen in pine plantations of the Southeastern United States using 15N enriched fertilizers. Forests 7, 270. doi: 10.3390/f7110270

Räbiger, T., Andres, M., Hegewald, H., Kesenheimer, K., Köbke, S., Quinones, T. S., et al. (2020). Indirect nitrous oxide emissions from oilseed rape cropping systems by NH3 volatilization and nitrate leaching as affected by nitrogen source, N rate and site conditions. Eur. J. Agron. 116, 126039. doi: 10.1016/j.eja.2020.126039

Ru, X., Jingnan, C., Zhiyuan, L., Xieyong, C., Maomao, H., Shanshan, S., et al. (2020). Fate of urea-15 N as influenced by different irrigation modes. RSC Adv. 10, 11317–11324. doi: 10.1039/D0RA00002G

Sardar, M. F., Younas, F., Farooqi, Z. U. R., Li, Y. (2023). Soil nitrogen dynamics in natural forest ecosystem: a review. Front. For. Glob. Change 6. doi: 10.3389/ffgc.2023.1144930

Shi, X., Hu, K., Batchelor, W. D., Liang, H., Wu, Y., Wang, Q., et al. (2020). Exploring optimal nitrogen management strategies to mitigate nitrogen losses from paddy soil in the middle reaches of the Yangtze River. Agric. Water Manage. 228, 105877. doi: 10.1016/j.agwat.2019.105877

Shi, Z., Jing, Q., Cai, J., Jiang, D., Cao, W., Dai, T. (2012). The fates of 15N fertilizer in relation to root distributions of winter wheat under different N splits. Eur. J. Agron. 40, 86–93. doi: 10.1016/j.eja.2012.01.006

Su, W., Fan, S., Zhao, J., Cai, C. (2019). Effects of various fertilization placements on the fate of urea- 15N in moso bamboo forests. For. Ecol. Manage. 453, 117632. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2019.117632

Tariq, A., Maqsood, M. A., Kanwal, S., Hussain, S., Ahmad, H. R., Sabir, M. (2015). Fertilizers and environment: issues and challenges. Crop Production Global Environ. Issues 30, 575–598. doi: 10.1007/978–3-319–23162-4_21

Voigtlaender, M., Brandani, C. B., Caldeira, D. R. M., Tardy, F., Bouillet, J.-P., Gonçalves, J. L. M., et al. (2019). Nitrogen cycling in monospecific and mixed-species plantations of Acacia mangium and Eucalyptus at 4 sites in Brazil. For. Ecol. Manage. 436, 56–67. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2018.12.055

Wang, D., Xu, Z., Zhao, J., Wang, Y., Yu, Z. (2011). Excessive nitrogen application decreases grain yield and increases nitrogen loss in a wheat–soil system. Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica Section B — Soil Plant Sci. 61, 681–692. doi: 10.1080/09064710.2010.534108

Wang, R., Zhang, J., Cai, C., Wang, S. (2023a). Mechanism of nitrogen loss driven by soil and water erosion in water source areas. J. For. Res. 34, 1985–1995. doi: 10.1007/s11676-023-01640-3

Wang, R., Zhang, J., Cai, C., Zhang, H. (2023b). How to control nitrogen and phosphorus loss during runoff process? – A case study at Fushi Reservoir in Anji County (China). Ecol. Indic. 155, 111007. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2023.111007

Wang, T., Wang, N., Song, S. Z., Wang, W. Y. (2022). Effects of fertilization on qiongzhuea tumidinod shoots growth. World Bamboo Rattan 20, 34–37. doi: 10.12168/sjzttx.2022.03.006

Weih, M., Nordh, N.-E., Manzoni, S., Hoeber, S. (2021). Functional traits of individual varieties as determinants of growth and nitrogen use patterns in mixed stands of willow (Salix spp.). For. Ecol. Manage. 479, 118605. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2020.118605

Wen, L., Lei, P., Xiang, W., Yan, W., Liu, S. (2014). Soil microbial biomass carbon and nitrogen in pure and mixed stands of Pinus massoniana and Cinnamomum camphora differing in stand age. For. Ecol. Manage. 328, 150–158. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2014.05.037

Wu, X. P., Liu, S., Luan, J., Wang, Y., Gao, X., Chen, C. (2023a). Nitrogen addition alleviates drought effects on water status and growth of Moso bamboo (Phllostachys edulis). For. Ecol. Manage. 530, 120768. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2023.120768

Wu, Y., Dong, W., Pu, C., Xie, Z., Zhong, H., Li, J., et al. (2022). Biomass of accumulation and allocation characteristics of Qiongzhou tumidinoda components and its relationship with soil physical properties. Acta Ecologica Sin. 42, 3516–3524. doi: 10.5846/stxb202103290815

Wu, Y., Li, J., Yu, L., Wang, S., Lv, Z., Long, H., et al. (2023b). Overwintering performance of bamboo leaves, and establishment of mathematical model for the distribution and introduction prediction of bamboos. Front. Plant Sci. 14. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2023.1255033

Xia, L., Dong, W. Y., Zhong, H., Pu, C., Chen, X., Yuan, L. L., et al. (2022). Diagnosis and comprehensive evaluation of soil fertility in four typical qiongzhuea tumidinod. J. West China Forestry Sci. 51, 62–69. doi: 10.16473/j.cnki.xblykx1972.2022.01.010

Yan, E.-R., Wang, X.-H., Huang, J.-J., Li, G.-Y., Zhou, W. (2008). Decline of soil nitrogen mineralization and nitrification during forest conversion of evergreen broad-leaved forest to plantations in the subtropical area of Eastern China. Biogeochemistry 89, 239–251. doi: 10.1007/s10533-008-9216-5

Yan, W., Farooq, T. H., Chen, Y., Wang, W., Shabbir, R., Kumar, U., et al. (2022). Soil nitrogen transformation process influenced by litterfall manipulation in two subtropical forest types. Front. Plant Sci. 13. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.923410

Yan, Y., Xia, M., Fan, S., Zhan, M., Guan, F. (2018). Detecting the competition between moso bamboos and broad-leaved trees in mixed forests using a terrestrial laser scanner. Forests 9, 520. doi: 10.3390/f9090520

Yang, L., Dong, W. Y., Zhao, J. F., Mao, W. J. (2012). Biodiversity of qiongzhuea tumidinod community in daguan county of Yunnan province. J. West China Forestry Sci. 41, 60–65. doi: 10.16473/j.cnki.xblykx1972.2012.03.021

Yiyuan, W., Wenyuan, D., Pei, L., Mengnan, Z., Zexuan, X., Fakun, T. (2020). Anatomical characteristics and adaptability plasticity of Qiongzhuea tumidinoda stalk under different soil water and nutrient conditions. bjlydxxb 42, 80–90. doi: 10.12171/j.1000–1522.20190290

Yuan, L. L., Dong, W. Y., Zhong, H., Chen, X., Xia, L., Huang, X. D., et al. (2022). Vertical distribution characteristics of soil enzyme activities in different types of qiongzhuea tumidinod stands. World Bamboo Rattan 20, 56–61+66. doi: 10.12168/sjzttx.2022.02.010

Zhang, M., Fan, S., Guan, F., Yan, X., Yin, Z. (2020a). Soil bacterial community structure of mixed bamboo and broad-leaved forest based on tree crown width ratio. Sci. Rep. 10, 6522. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-63547-x

Zhang, W., Dong, W. Y., Zhong, H., Li, J., Liu, Z., Wu, Y. Y., et al. (2020b). Effects of different mixed types on the growth of qiongzhuea tumidinod and spatial differences of soil nutrients. J. West China Forestry Sci. 49, 70–75+84. doi: 10.16473/j.cnki.xblykx1972.2020.06.010

Zhao, J., Cai, C. (2023). Effects of physiological integration on nitrogen use efficiency of moso bamboo in homogeneous and heterogeneous environments. Front. Plant Sci. 14. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2023.1203881

Zheng, A., Lv, J. (2023). Spatial patterns of bamboo expansion across scales: how does Moso bamboo interact with competing trees? Landsc Ecol. 38, 3925–3943. doi: 10.1007/s10980-023-01669-z

Zheng, Y., Fan, S., Guan, F., Zhang, X., Zhou, X. (2022). Characteristics of the litter dynamics in a Moso bamboo forest after strip clearcutting. Front. Plant Sci. 13. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.1064529

Zhong, H., Dong, W. Y., Li, J., Zhang, W., Liu, Z., Zheng, J. N., et al. (2020). Water holding capacity of litters from four types of qiong bamboo forest in northeastern Yunnan Province. World Bamboo Rattan 18, 21–27. doi: 10.12168/sjzttx.2020.03.004

Zhong, H., Dong, W. Y., Pu, C., Xie, Z. X., Zhang, W., Zheng, J. N., et al. (2023). Ecological stoichiometry of soil C, N and P in 4 different types of qiongzhuea tumidinod forests in Northeast Yunnan. J. Southwest Forestry Univ. (Natural Sciences) 43, 111–119. doi: 10.11929/j.swfu.202203054

Zhou, Y. Q., Dong, J., Guan, F., Fan, S. H. (2016). Progress and prospects of the research on mixed bamboo and broadleaf forest. For. resource Manage. 3, 145–150. doi: 10.13466/j.cnki.lyzygl.2016.03.026

Zhu, Y., Gong, Y., Li, J., Wang, N., Zhao, X. (2023). Review and future prospects of the research on qiongzhuea tumidinoda. World Bamboo Rattan 21, 75–83+98. doi: 10.12168/sjzttx.2023.03.014

Zou, N., Shi, W., Hou, L., Kronzucker, H. J., Huang, L., Gu, H., et al. (2020). Superior growth, N uptake and NH4+ tolerance in the giant bamboo Phyllostachys edulis over the broad-leaved tree Castanopsis fargesii at elevated NH4+ may underlie community succession and favor the expansion of bamboo. Tree Physiol. 40, 1606–1622. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpaa086

Zou, Z., Li, Y., Song, H. (2023). Influence of the size of clonal fragment on the nitrogen turnover processes in a bamboo ecosystem. Front. Plant Sci. 14. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2023.1308072

Keywords: biomass, N recovery efficiency, bamboo-broadleaf mixed forests, Qiongzhuea tumidinoda, 15N tracing technology

Citation: Wu Y, Dong W, Zhong H, Duan J, Li W, Pu C, Li X and Xie Z (2024) Comparative study of urea-15N fate in pure bamboo and bamboo-broadleaf mixed forests. Front. Plant Sci. 15:1382934. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2024.1382934

Received: 06 February 2024; Accepted: 30 April 2024;

Published: 21 May 2024.

Edited by:

Anoop Kumar Srivastava, Central Citrus Research Institute (ICAR), IndiaReviewed by:

Muhammad Haroon U. Rashid, University of Agriculture, Faisalabad, PakistanSeyed Majid Mousavi, Soil & Water Research Institute, Iran

Copyright © 2024 Wu, Dong, Zhong, Duan, Li, Pu, Li and Xie. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wenyuan Dong, d3lkb25nNjgzOUBzaW5hLmNvbQ==

Yiyuan Wu

Yiyuan Wu Wenyuan Dong2*

Wenyuan Dong2*