- 1Institute of Crop Research, Fujian Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Fujian Germplasm Resources Center)/Fujian Province Characteristic Dry Crop Variety Breeding Engineering Technology Research Center, Fuzhou, China

- 2State Key Laboratory of Ecological Pest Control for Fujian and Taiwan Crops, Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University, Fuzhou, China

- 3Fujian Key Laboratory for Monitoring and Integrated Management of Crop Pests, Institute of Plant Protection, Fujian Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Fuzhou, China

- 4The Key Laboratory of Biology and Genetic Improvement of Oil Crops, The Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the PRC, Oil Crops Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Wuhan, China

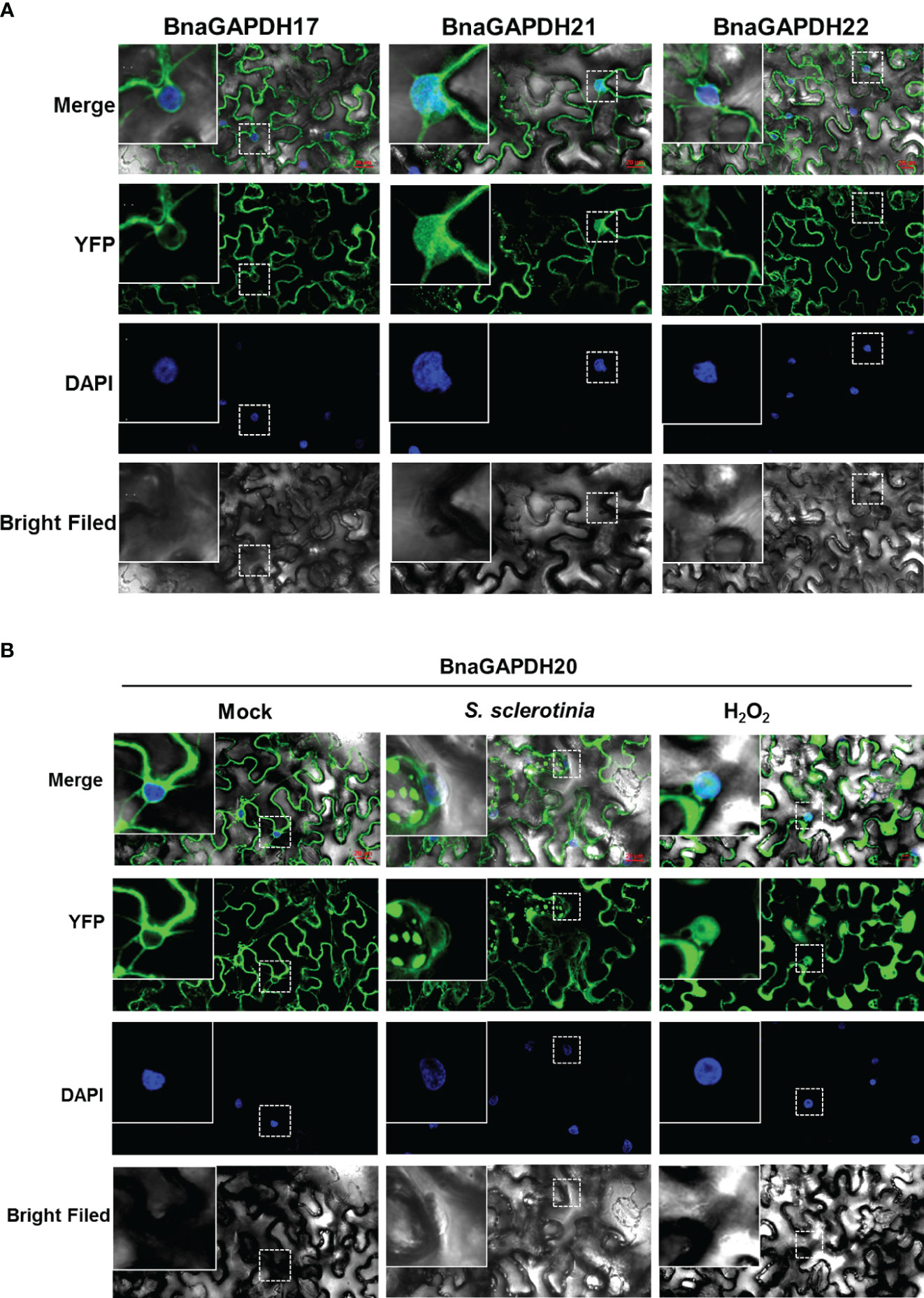

Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) is a crucial enzyme in glycolysis, an essential metabolic pathway for carbohydrate metabolism across all living organisms. Recent research indicates that phosphorylating GAPDH exhibits various moonlighting functions, contributing to plant growth and development, autophagy, drought tolerance, salt tolerance, and bacterial/viral diseases resistance. However, in rapeseed (Brassica napus), the role of GAPDHs in plant immune responses to fungal pathogens remains unexplored. In this study, 28 genes encoding GAPDH proteins were revealed in B. napus and classified into three distinct subclasses based on their protein structural and phylogenetic relationships. Whole-genome duplication plays a major role in the evolution of BnaGAPDHs. Synteny analyses revealed orthologous relationships, identifying 23, 26, and 26 BnaGAPDH genes with counterparts in Arabidopsis, Brassica rapa, and Brassica oleracea, respectively. The promoter regions of 12 BnaGAPDHs uncovered a spectrum of responsive elements to biotic and abiotic stresses, indicating their crucial role in plant stress resistance. Transcriptome analysis characterized the expression profiles of different BnaGAPDH genes during Sclerotinia sclerotiorum infection and hormonal treatment. Notably, BnaGAPDH17, BnaGAPDH20, BnaGAPDH21, and BnaGAPDH22 exhibited sensitivity to S. sclerotiorum infection, oxalic acid, hormone signals. Intriguingly, under standard physiological conditions, BnaGAPDH17, BnaGAPDH20, and BnaGAPDH22 are primarily localized in the cytoplasm and plasma membrane, with BnaGAPDH21 also detectable in the nucleus. Furthermore, the nuclear translocation of BnaGAPDH20 was observed under H2O2 treatment and S. sclerotiorum infection. These findings might provide a theoretical foundation for elucidating the functions of phosphorylating GAPDH.

1 Introduction

Glycolysis is a crucial metabolic process involved in carbohydrate metabolism ubiquitous across all living organisms (Danshina et al., 2001). Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) plays a central role in this pathway, facilitating the NAD-dependent conversion of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate (G3P) to 1,3-bisphosphoglyceric acid (Bruns and Gerald, 1976). Animal cells have only one isoform of GAPDH (Nicholls et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2020), but plants exhibit multiple isoforms of GAPDHs, each encoded by distinct genes and residing in specific subcellular compartments (Zaffagnini et al., 2013). For instance, the Arabidopsis thaliana genome encodes eight GAPDHs, including seven phosphorylating GAPDHs and one nonphosphorylating GAPDH. The phosphorylating GAPDHs consist of chloroplast photosynthetic GAPDH (GAPA1, GAPA2, and GAPB), cytosolic glycolytic GAPDHs (GAPC1 and GAPC2), and plastidic glycolytic GAPDHs (GAPCp1 and GAPCp2). The nonphosphorylating GAPDH is referred to as NADP-dependent nonphosphorylating cytosolic GAPDH (NP-GAPDH) (Zaffagnini et al., 2013). Comprehensive studies have led to the identification and functional elucidation of various GAPDH gene families across numerous plant species, including Arabidopsis (Rius et al., 2006; Holtgrefe et al., 2008; Muñoz-Bertomeu et al., 2009, 2010; Muñoz-Bertomeu et al., 2011; Guo et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2020), rice (Zhang et al., 2011), wheat (Zeng et al., 2016; Ying et al., 2017), tobacco (Han et al., 2015), potato (Liu et al., 2017), sweet orange (Miao et al., 2019), strawberry (Luo et al., 2020), and cassava (Zeng et al., 2018).

GAPDHs have traditionally served as internal reference genes (Morgante et al., 2011; Kozera and Rapacz, 2013; Zhu et al., 2014). Nonetheless, recent findings indicate that the expression levels of GAPDHs vary under different stress scenarios (Bai et al., 2012), a revealing numerous moonlighting functions including membrane trafficking (Tisdale, 2001), mRNA stability (Zeng et al., 2014), DNA repair (Demarse et al., 2009), transcriptional expression (Zheng et al., 2003) signal transduction (Harada et al., 2007), cellular apoptosis (Hara et al., 2005),membrane fusion (Nakagawa et al., 2002), drought stress (Zhang et al., 2020), autophagy (Wang et al., 2022), heat stress (Kim et al., 2020) and immunity (Henry et al., 2015). For example, in Arabidopsis, AtGAPDHs, including AtGAPA, AtGAPCs, and AtGAPCps, regulate the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and cell death when exposed to the bacterial pathogen Pseudomonas syringae, thus negatively regulating disease resistance (Henry et al., 2015). Moreover, NbGAPCs in tobacco are known for their multifunctional roles in regulating autophagy, hypersensitive response, and plant innate immunity (Han et al., 2015). On the contrary, MeGAPCs in cassava play a contrasting role by negatively regulating plant disease resistance against Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. manihotis (Xam) by interacting with MeATG8b and MeATG8e (Zeng et al., 2018). Furthermore, cytosolic GAPDHs are also involved in viral infection (Kaido et al., 2014).

One mechanism underlying GAPDHs’ action in stress response is their stress-induced nuclear translocation (Sirover, 2021). In Arabidopsis, a portion of cytosolic GAPDHs accumulates in the nucleus in response to various stimuli, including cadmium, bacterial flagellin, phosphatidic acid, and hydrogen sulfide (Vescovi et al., 2013; Henry et al., 2015; Aroca et al., 2017). This nuclear accumulation of cytosolic GAPDHs was also noted in tobacco BY-2 (bright-yellow 2) cells subjected to programmed cell death (PCD) triggers, such as long-chain bases (Testard et al., 2016). Given that GAPC lacks a nuclear localization signal, the post-translational modifications of specific amino acid residues are believed to be crucial for its intracellular translocation. In mammals, when cells are continuously exposed to a stressor, an increase in the level of nitrosative stress beyond a certain threshold leads to the nitrosylation of the catalytic Cys150 of rat GAPDH (forming SNO-GAPDH) (Hara et al., 2005). SNO-GAPDH is recognized by Siah1 which contains a nuclear localization signal and mediates the translocation of the SNO-GAPDH-Siah1 complex to the nucleus (Hara et al., 2005). It is reported that the cytosolic GAPDHs AtGAPC1 and AtGAPC2 undergo redox-dependent cysteine modifications, leading to the enzymes’ inactivation in glycolysis (Holtgrefe et al., 2008). Additionally, GAPDH is thought to function as an H2O2 sensor, initiating the protective oxidative stress response and helping reestablish cellular homeostasis. Furthermore, the nuclear presence of cytosolic GAPDH increases under oxidizing conditions in Arabidopsis (Schneider et al., 2018). In summary, GAPDH may detect H2O2 and undergo post-translational modifications, leading to its nuclear translocation, possibly in conjunction with its moonlighting functions.

Brassica napus is one of the most important oil crops in China and one of the four major oil crops globally. It belongs to the Brassicaceae family and is an allotetraploid (2n = 38, AACC) resulting from hybridization between Brassica rapa (2n = 20, AA) and Brassica oleracea (2n = 18, CC) around 7500 years ago (Bayer et al., 2017; Ding et al., 2021). The B. napus genome has evolved through ancient polyploidization events, recent hybridization, and gene loss, resulting in approximately 100,000 genes (De Grassi et al., 2008). This evolutionary history and the close relationship of B. napus with A. thaliana make B. napus an ideal model for studying gene family evolution. B. napus faces constant challenges by various pathogenic microorganisms, including Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (de Bary.), which causes severe stem rot (SSR). This disease leads to yield losses of 10%–20% and can reach up to 80% in some seasons (Yang, 1959; Li et al., 2006; Mei et al., 2011). Although measures like fungicidal control and crop rotation can mitigate this issue, they are often insufficient due to the long survival of sclerotia in the soil and the wide host range of S. sclerotiorum. Consequently, breeding new resistant varieties is essential for managing SSR in the future (Ding et al., 2021). Understanding the interaction mechanism between B. napus and S. sclerotiorum is fundamental to developing disease-resistant varieties.

In all kingdoms of life, stress situations caused by pathogens, such as S. sclerotiorum, have been linked to increased cellular levels of ROS (Hildebrandt et al., 2015). GAPDHs are likely involved in this process in B. napus. However, comprehensive information about the GAPDH gene family in this crop species is lacking. Therefore, in this study, an in silico approach was first used to identify and characterize the phosphorylating GAPDH family in B. napus and then systematically analyze their expression patterns under various stress conditions, including S. sclerotiorum infection and treatment with different hormones and oxalic acid (OA). Specifically, four genes highly induced by these stimuli were selected to observe their subcellular localization and nuclear translocation under normal and stress conditions. In this study, B. napus was used as the research material to clarify the quantity, nature, general relationship, and function of phosphorylating GAPDH proteins in B. napus. This research provides a theoretical foundation for clarifying the functions of phosphorylating GAPDHs.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Identification of GAPDH family genes

Protein sequences from B. napus, B. rapa, and B. oleracea were used to identify GAPDH genes. Initially, the B. napus v5.0 protein set was downloaded from http://www.genoscope.cns.fr/brassicanapus, B. rapa “Z1” and B. oleracea “HDEM” protein sets were downloaded from https://www.genoscope.cns.fr/externe/plants/chromosomes.html. Next, the six GAPDH protein sequences of A. thaliana downloaded from TAIR (https://www.Arabidopsis.org/) were used as queries to perform BLASTp searches against the protein sequences of each species, employing an E-value cutoff of 1e-10. Subsequently, HMMER v3.0 was employed for an HMM search against the local protein database, using the specific Gp_dh_N domain (PF00044) and Gp_dh_C domain (PF02800) HMM profiles obtained from the Pfam database (http://pfam.xfam.org/search), with the default parameters and an E-value cutoff of 1e−5. Subsequently, all putative GAPDHs were validated by batch-CD search (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi), Pfam (http://pfam.xfam.org/), and SMART (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/) databases. Furthermore, the biochemical parameters of BnaGAPDHs were determined using the ProtParam tool (https://web.expasy.org/protparam/, accessed on August 11, 2021). Finally, the subcellular localizations of BnaGAPDHs were predicted using the Plant-mPLoc tool, as described by KuoChen and HongBin in 2010.

2.2 Multiple sequence alignments and phylogenetic analysis

Alignment of the full-length GAPDH protein sequences from B. napus, B. rapa, B. oleracea, and A. thaliana was performed using the MAFFT online server (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/mafft/) (Madeira et al., 2019; Rozewicki et al., 2019). A maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree was constructed using IQ-TREE (Nguyen et al., 2015). For tree construction, the best-fit model, JTT+G4, was chosen based on the Bayesian Information Criterion with ModelFinder (integrated within IQ-TREE) (Kalyaanamoorthy et al., 2017). Both the Ultrafast Bootstrap and the Shimodaira-Hasegawa approximate likelihood ratio test (SH-aLRT) were conducted with 1000 replicates. The resulting tree file was visualized using FigTree V1.4.4 (https://github.com/rambaut/figtree/releases).

2.3 Promoter sequence, gene structure, and conserved motif analysis

The upstream 2000-bp sequences relative to the start codon of each BnaGAPDH gene were obtained to analyze the promoter regions, and the cis-elements within these regions were predicted using the PlantCARE web tool (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/), accessed on 27 July 2021. The findings were visualized using TBtools (V 1.09854).

The exon-intron structures of the BnaGAPDH genes were illustrated by the Gene Structure Display Server (GSDS; http://gsds.cbi.pku.edu.cn), following the genome annotation. The conserved motifs within these proteins were identified using the MEME suite (Bailey et al., 2009) (http://meme-suite.org/tools/meme), employing the following parameters: any number of repetitions, optimal motif widths between 6 and 50 residues, and a maximum of 10 motifs. A comprehensive schematic diagram depicting the amino acid motifs and gene structure for each GAPDH gene was subsequently assembled using the Advanced Gene Structure View module in TBtools.

2.4 Chromosomal distribution, gene duplication, and collinear analysis

The chromosomal distribution of BnaGAPDHs was obtained from the gff3 genome annotation file of B. napus and visualized using the module Gene Location Visualize from GTF/GFF in TBtool. A tandem duplication case is defined as a homologous gene pair located within a 200-kb region of the same chromosome as well as a separation gap of 20 or fewer genes (Malik et al., 2020). The interspecific and intraspecific collinear analyses were performed with MCScanX (E-value 1e-10) (Wang et al., 2012) and visualized using Multiple Synteny Plot in TBtools (V 1.09854). Nonsynonymous (Ka) and synonymous (Ks) substitution sites of each duplicated gene pair were calculated using the Ka/Ks calculator in TBtools (V 1.09854).

2.5 Transcriptional profile of BnaGAPDHs in different tissues and during S. sclerotiorum infection

The sclerotia of the fungus S. sclerotiorum 1980 were germinated to produce hyphal inoculum on potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium. Sensitive cultivar 84039 and moderately resistant cultivar ZhongShuang9 were grown in pots containing soil and vermiculite (3:1, v/v) under greenhouse conditions at 23–25°C with a 16/8-h light/dark photoperiod and fertilization with commercial N: K: P (1:1:1) every 10 days. After 4 weeks, three fourths of the leaves were inoculated with agar plugs excised from the edges of growing S. sclerotiorum colonies. The samples were collected at 12 and 22 hpi and then sent to Novogene Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China) for RNA extraction, library construction, and transcriptome sequencing on the Illumina sequencing platform. After removing the 5’ and 3′ -adapters, N >10% sequences, and low-quality sequences (sequence quality values ≤Q20), the clean data were aligned to the B. napus reference genome (https://www.genoscope.cns.fr/brassicanapus/) using TopHat2 (Kim et al., 2013)(http://ccb.jhu.edu/software/tophat/index.shtml). The transcript abundance [fragments per kilobase million (FPKM) value] of each gene was calculated using HTSeq (Anders et al., 2015) (https://htseq.readthedocs.io/en/release_0.11.1/).

B. napus cultivar ZhongYou 821 (ZY821) and Westar were generally used as resistant and susceptible doubled haploid lines in response to S. sclerotiorum inoculation. The expression data of BnaGAPDHs during the inoculation of S. sclerotiorum in B. napus cultivar ZY821 and cultivar Westar were downloaded from the NCBI GEO database (Accession number GSE81545). Similarly, the expression profile of BnaGAPDHs in different tissues/organs of B. napus cultivar “Zhongshuang 11” were downloaded from the B. napus transcriptome information resource (http://yanglab.hzau.edu.cn/BnTIR/expression_show). The FPKM values of all BnaGAPDHs were extracted and submitted to TBtools to generate heatmaps. All of the heatmaps were normalized using log2(value+1).

2.6 Plant cultivation, treatments, RNA isolation, and qRT-PCR

The third and fourth leaves of 4-week-old Zhongshuang9 were sprayed with methyl jasmonic acid (MeJA), salicylic acid (SA), and OA or inoculated with S. sclerotiorum strain 1980, collected at 0, 6, 12, 24, 36 and 48 hours post-inoculation (hpi), immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C.

The total RNA isolation and purification of samples were performed using an RNAprep Pure Plant Plus Kit (rich in polysaccharides and polyphenolics) (Tiangen, Beijing, China). The RNA isolation for gene expression was done in triplicate for each sample analyzed. RNA integrity was visualized by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. The concentration and purity of RNAs (OD260/OD280 ratio > 1.95) were determined with a NanoDrop One microvolume UV-vis spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, DE, USA). Further, 1 μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed in a 20-μL reaction volume using a PrimeScript RT reagent kit with a gDNA eraser (Takara, Beijing, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions to remove traces of contaminant DNA and prepare cDNA.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis was used to analyze the expression level of the identified BnaGAPDHs. The standard qRT-PCR with SYBR Premix Ex Taq II (TaKaRa, Beijing, China) was repeated at least three times on a CFX96 real-time System (BioRad, Beijing). Primer Premier 6.0 software were used to designed the specific primers of BnaGAPDH genes according to their gene sequences, listed in Supplementary Table S1. Results were analyzed by the 2−(ΔΔCt) method using the BnaACTIN (BnaC05g34300D) as the endogenous reference gene (He et al., 2019).

2.7 Subcellular localization

The full-length coding sequences of the selected BnaGAPDH genes were isolated and linked into the pEarlygate104 vector containing YFP reporter (saved in our laboratory). The competent cells of Escherichia coli (DH5α) and Agrobacterium (GV3101) were used for the transformation of recombinants. Primers used for gene cloning and vector construction are shown in Supplementary Table S1. Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression in tobacco (Nicotiana benthamiana) leaves was performed as previously described (Chen et al., 2019). Tobacco leaves injected with Agrobacterium agrobacterium for 40-48 h containing recombinant vector were cut into 3 mm2 small leaf discs. 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) dyeing solution with 0.1%TritonX-100 mixed in advance was added (CatNo.C1006, Beyotime Biotechnology Co., LTD.) two hours before observing using the laser scanning confocal microscopy (Olympus FV3000, Tokyo, Japan). For treatment of H2O2, the small leaf discs treated with DAPI were transferred into solution containing10 mM H2O2 40 minis before imaging. For inoculation treatment, 36-40 hours after injection of Agrobacterium, tobacco leaves were cut and placed in a tray with wetting filter paper back side up. After inoculating the hyphal plugs on the leaves, the plates were covered with a transparent plastic lid and incubated at 22°C for 8-12 hours. Blue fluorescence at the nuclear could be observed under an excitation wavelength of 340nm. The YFP fluorescence was observed under an excitation wavelength of 488 nm.

3 Results

3.1 Genome-wide identification of GAPDH family genes in Brassica napus

A BLASTP method using six known Arabidopsis homologs as queries and HMM searches with the Gp_dh_N (PF00044) and Gp_dh_C (PF02800) domains were performed to search the local protein database of B. napus so as to accurately identify GAPDH genes. After removing redundant sequences and domain verification, 28 full-length GAPDH homologous sequences were identified in the genomes of B. napus. Similarly, 14 and 14 full-length GAPDH homologous sequences were identified in the genomes of B. rapa and B. oleracea, respectively.

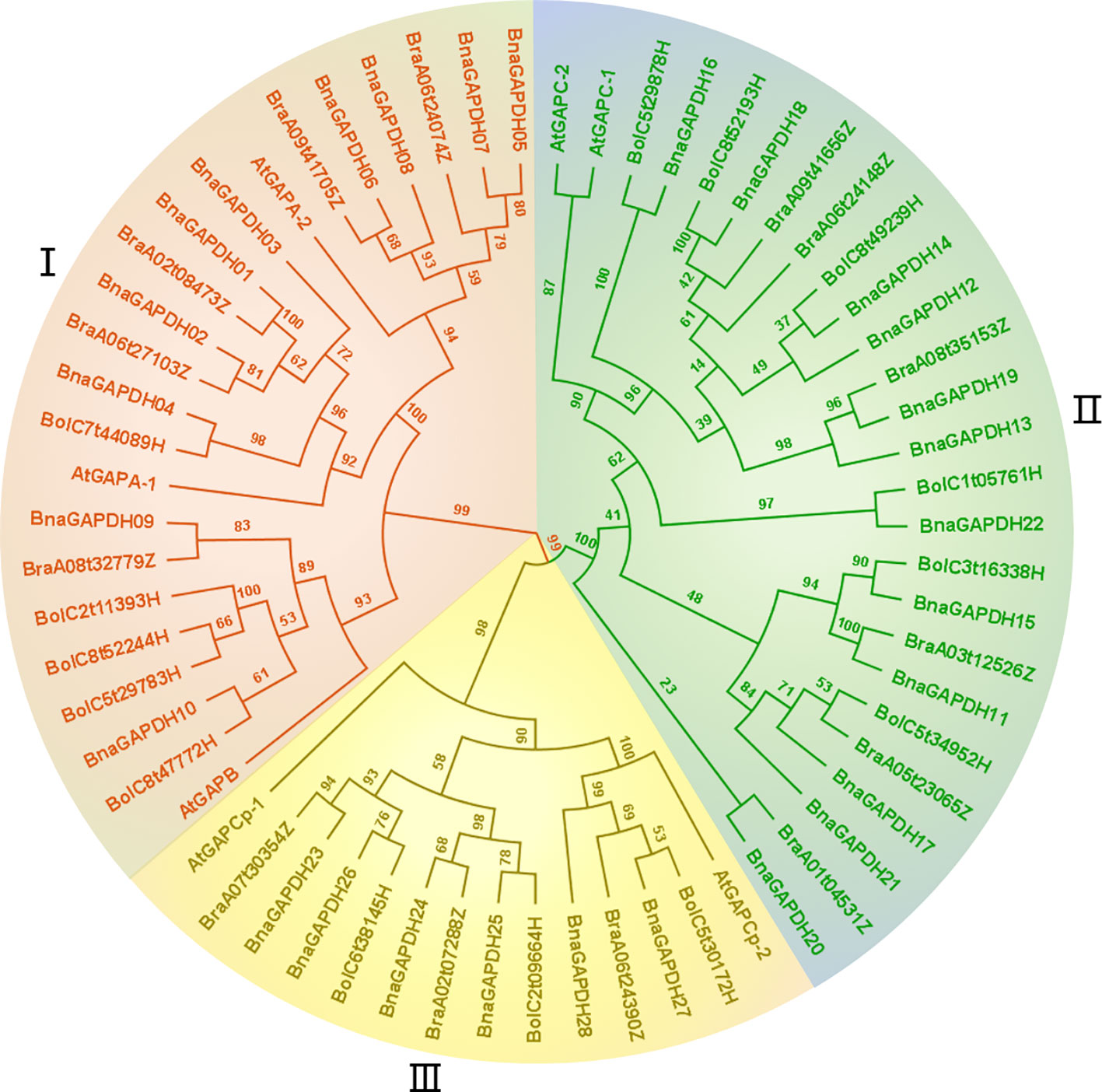

Like Arabidopsis, 28 GAPDHs in B. napus were classified into 3 groups based on the domain organization: Group I (GAPA/B), Group II (GAPCs), and Group III (GAPCps) (Table 1 and Figure 1). New names were assigned to 28 GAPDH genes in B. napus using the prefix “Bna,” followed by “GAPDH” and numbers based on their isoforms and chromosome positions (Table 1). As shown in Table 1, Group I had 10 members (BnaGAPDH01 to BnaGAPDH10), Group II had 12 members (BnaGAPDH11 to BnaGAPDH22), and Group III had 6 members (BnaGAPDH23 to BnaGAPDH28).

Figure 1 Phylogenetic relationship analysis of GAPDH family. The construction of phylogenetic tress using the GAPDH amino acid sequences among B. napus, B. rapa, B. oleracea, and A.thaliana. Phylogenetic tree topology was generated by IQ-Tree online server. The bootstrap value is 1000. All GAPDH genes in the phylogenetic tree are colored group-specific.

Gene characteristics, such as amino acid length, isoelectric point (pI), molecular weight (MW), grand average of hydropathy (GRAVY) values, Instability index, aliphatic indexand, and subcellular localization were analyzed (Table 1). Among the 28 BnaGAPDHs, BnaGAPDH12 was identified to be the smallest protein with 318 amino acids (aa), whereas the largest one was BnaGAPDH09 (448 aa). The predicted pI ranged from 5.59 (BnaGAPDH10) to 8.93 (BnaGAPDH1 and BnaGAPDH23), and the MW ranged from 35.29 kDa (BnaGAPDH12) to 47.55 kDa (BnaGAPDH9 and BnaGAPDH18). The GRAVY score, instability index,and aliphatic index were conserved among the BnaGAPDHs. The GRAVY values reflected that almost all BnaGAPDHs predicted to be hydrophilic proteins (GRAVY values <0). Their instability index were lower than 40, indictcating their stable chracteristics.Relatively, the GAPCP-type proteins were predicted to possesses lower stablity than the other two types of BnaGAPDHs according to their instability indes and aliphatic index scores. The Plant-mPLoc predicted that all of the GAPA/B-type BnaGAPDHs were localized in chloroplasts, while all of the GAPC-types in the cytoplasm.The GAPCp-types may appear in the cytoplasm and mitochondria.

3.2 Phylogenetic tree of the GAPDH gene family in B. napus

A maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree was generated based on the full-length protein sequences for 60 GAPDHs, including 28 B. napus, 14 B. rapa, 14 B. oleracea, and 7 A. thaliana members to further characterize and explore the evolutionary relationships of BnaGAPDHs. According to the classification of AtGAPDHs and the topology of the phylogenetic tree, as described earlier, 60 GAPDHs were assigned to 3 groups (I, II, and III), containing 23, 26, and 14 members (Figure 1), respectively. Each group contained the corresponding subgroup members from B. napus, AtGAPDHs, B. rapa, and B. oleracea. For example, Group III included AtGAPCp-1; AtGAPCp-2; BnaGAPDH23 to BnaGAPDH28; BraA07t30354Z, BraA02t07288Z, and BraA06t24390Z; BolC6t38145H, BolC2t09664H; and BolC5t30172H. Notably, the number of BnaGAPDHs in each group was equal to the sum of that in B. rapa and B. oleracea. Also, the BnaGAPDHs had a closer phylogenetic relationship with the BraGAPDHs and BloGAPDHs than AtGAPDHs. These results indicated the existence of three ancestral GAPDH paralogs in the most recent common ancestor of Brassicaceae; these paralogs might have undergone subsequent functional divergence.

3.3 Chromosomal distribution, gene duplication, and synteny analysis of B. napus GAPDH genes

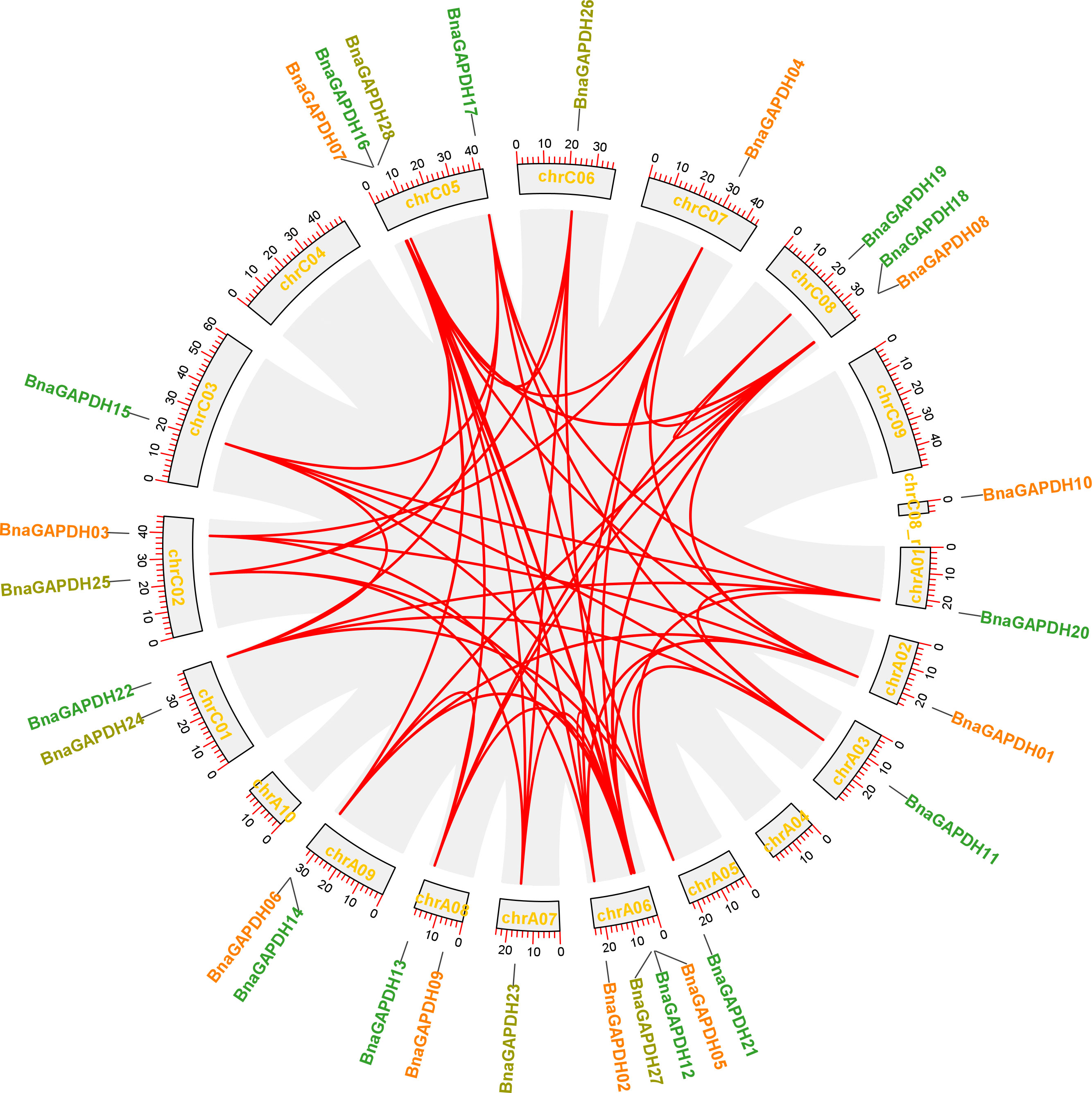

A chromosomal locational analysis was performed to gain insights into the distribution of GAPDH family genes on the chromosomes of B. napus. A total of 28 BnaGAPDHs were distributed unevenly on 16 chromosomes of B. napus, 13 genes in the An-subgenome, and 15 genes in the Cn-subgenome (Figure 2). ChrA06 and ChrC05 contained four GAPDH genes, whereas ChrA01, ChrA02, ChrA03, ChrA07, ChrC03, ChrC06, and ChrC07 had only one. Furthermore, potential gene duplication events in the B. napus genome were analyzed (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table S2). 58 whole-genome duplication (WGD)/segmental duplication events with 25 BnaGAPDHs were detected in the B. napus genome, indicating that WGD and segmental duplication were important in the expansion of the B. napus GAPDH gene family.

Figure 2 Schematic representations for the chromosomal distribution and inter-chromosomal associations of B.napus GAPDH genes. Grey lines indicate all syntenic blocks in the B. napus genome, and the red lines indicate syntenic BnaGAPDH gene pairs. The chromosome numbers are indicated at the bottom of each chromosome.

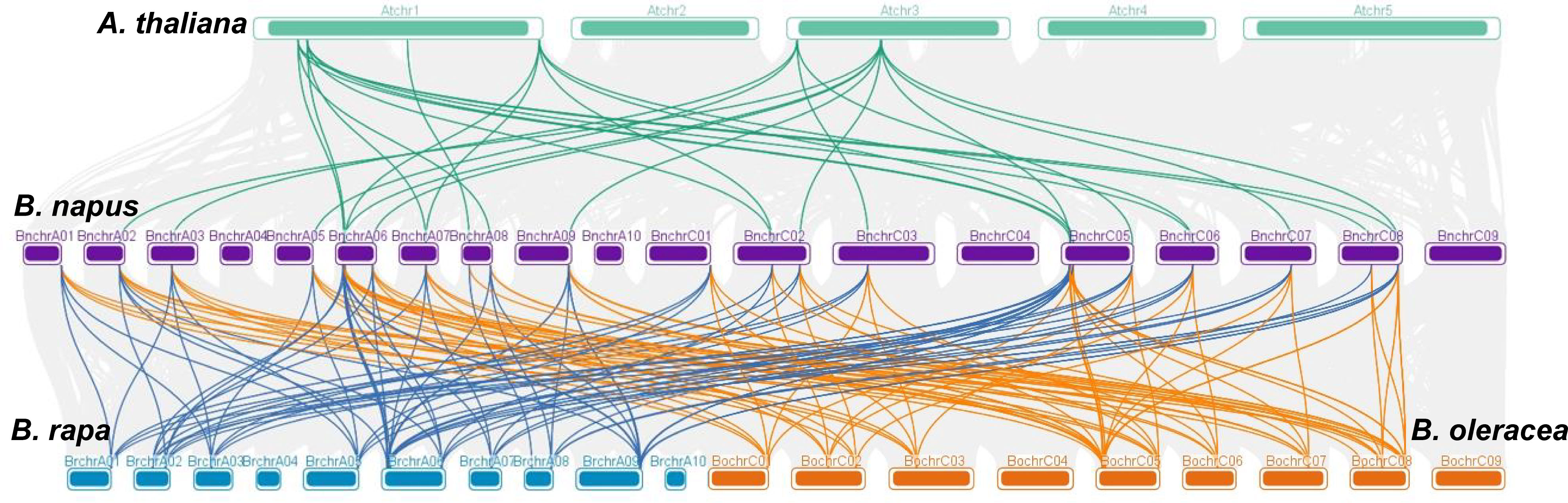

Collinearity analysis was conducted involving B. napus, B. rapa, B. oleracea, and A. thaliana to further explore the evolutionary mechanisms of the BnaGAPDH genes (Figure 3; Supplementary Table S3). A total of 23 BnaGAPDHs had a collinear relationship with 6 AtGAPDHs in A. thaliana, whereas 26 BnaGAPDHs were collinear with 14 BraGAPDHs in B. rapa and 14 BolGAPDHs in B. oleracea. Notably, most of the orthologs of A. thaliana (6/7, 85.7%), B. rapa (14/14, 100%), and B. oleracea (14/14, 100%) sustained a syntenic association with BnaGAPDHs, suggesting that WGD played a key role in BnaGAPDH gene family evolution along with segmental duplication. Also, nonsynonymous and synonymous substitution ratio (Ka and Ks) analyses of orthologous GAPDH gene pairs were performed to detect the driving force for the evolution of the GAPDH gene family (Supplementary Table S3). The results showed that most of the orthologous GAPDH gene pairs had a Ka/Ks ratio of less than 1, suggesting purifying selective pressure during GAPDH gene family evolution and conserved functions of these genes. Only one gene pair, BnaGAPDH26 (BnaC06g19790D) and BolC6t38145H, had a Ka/Ks ratio of more than 1, indicating that these genes had undergone positive selection pressure and might have evolved new functions to help plants cope with their living environments.

Figure 3 Syntenic relationships of GAPDH genes between B. napus, B. rapa, B. oleracea, and A. thaliana. The four species of plants chromosomes are shown in different colors. Grey lines in the background show the collinear blocks between B.napus and other 3 plant genomes, the colored lines highlight the syntenic GAPDH gene pairs.

3.4 Conserved motifs, structural domains, and gene structure analyses of BnaGAPDHs in B. napus

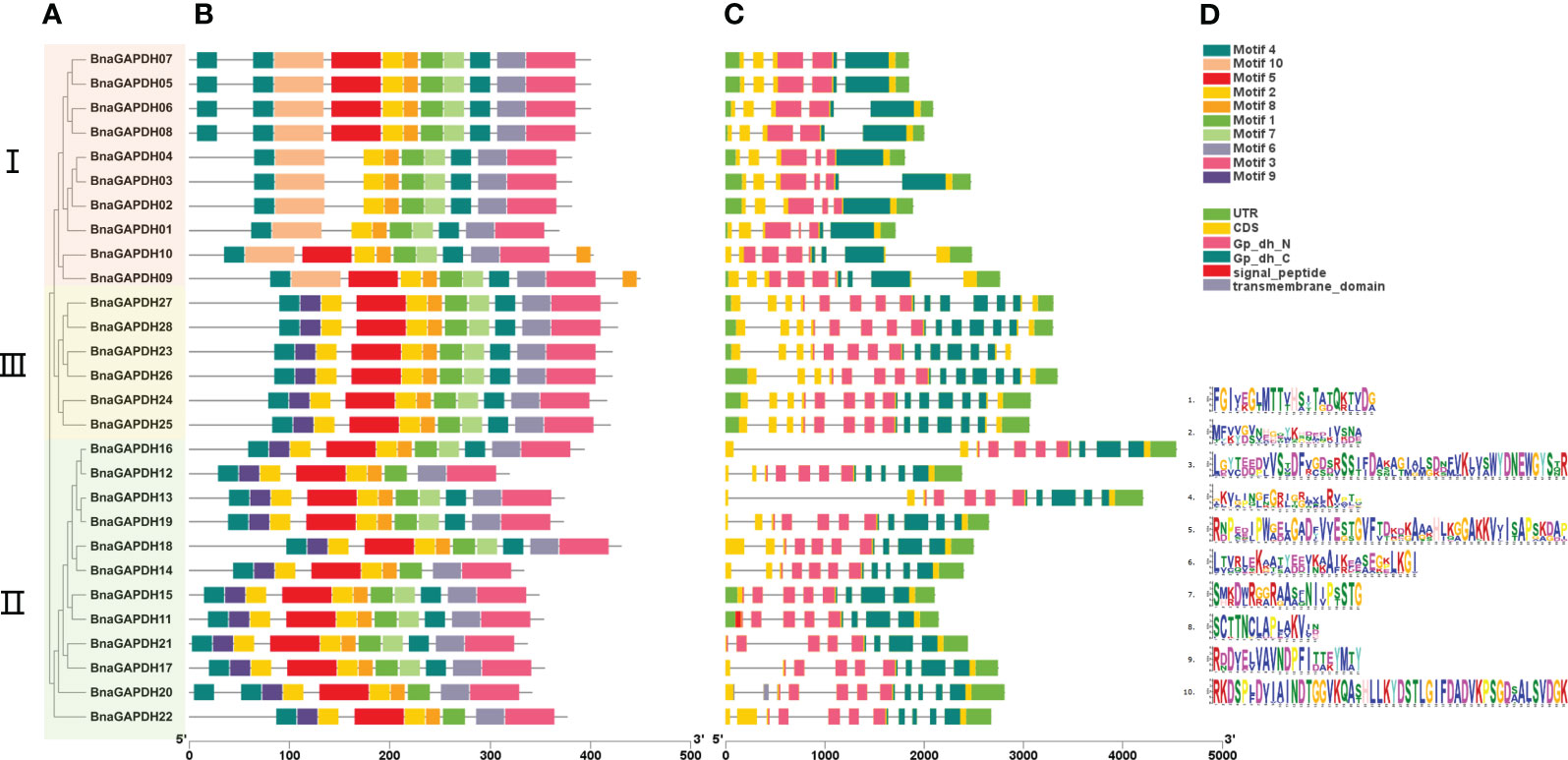

Ten motifs and the association with conserved domains were predicted in the BnaGAPDH proteins (Figure 4B and Supplementary Table S4). Motif 5 and Motif 10 belonged to the Gp_dh_N domain, whereas Motifs 1, 3, 4, 6, 7, and 8 belonged to the Gp_dh_C domain. Most members from the same group shared similar motif compositions, whereas the motif compositions varied slightly among groups (Figures 4A, B). Motifs 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, and 8 were identified in all BnaGAPDHs except for four genes (BnaGAPDH12, BnaGAPDH14, BnaGAPDH20, and BnaGAPDH22). Motif 10 was found only in Group I, whereas Motif 9 was present only in Groups II and III. Taken together, these results indicated that the motif compositions within the group were relatively consistent, providing additional support for the phylogenetic classification.

Figure 4 The motif analysis and gene structure of the GAPDH family genes from B.napus. (A) Phylogenetic tree of 28 BnaGAPDHs. According to the phylogenetic relationships, the GAPDH genes from B.napus genome were clustered into three groups (Groups I–III). (B) Conserved motifs identified in the BnGAPDHs. Different color boxes show motifs 1 to 10. (C) The overlying of gene structure and conserved domains of the BnGAPDHs. Light green color shows the UTR regions, yellow color shows the CDS or exons (pink color shows the specific Gp_dh_N domain (PF00044), dark green color shows Gp_dh_C domain (PF02800), red color shows transmembrane domain, and grey color shows signal peptide), black horizontal line shows the introns. (D) The corresponding sequence logos of 10 conserved motifs.

Subsequently, the gene structure of the 28 BnaGAPDHs were investigated (Figure 4C). The number of exons varied, ranging from 5 to 14. Most of the genes within the same cluster displayed similar exon-intron structures. Notably, members of Group III contained the highest number of exons, with each having 14, while those in Group I had the fewest. According to the protein structure predictions, all members possessed two domains specific to full-length GAPDHs: the Gp_dh_N domain and the Gp_dh_C domain. Interestingly, within Group III, BnaGAPDH11 and BnaGAPDH20 were unique, with the former appearing to have a signal peptide domain and the latter a transmembrane domain. These results demonstrated the presence of highly conserved structures within the subgroups and diversity among different groups. They indicated that the gaining and splitting of exons and introns, as well as the presence of highly conserved domains, were characteristic developments within the BnaGAPDH gene family.

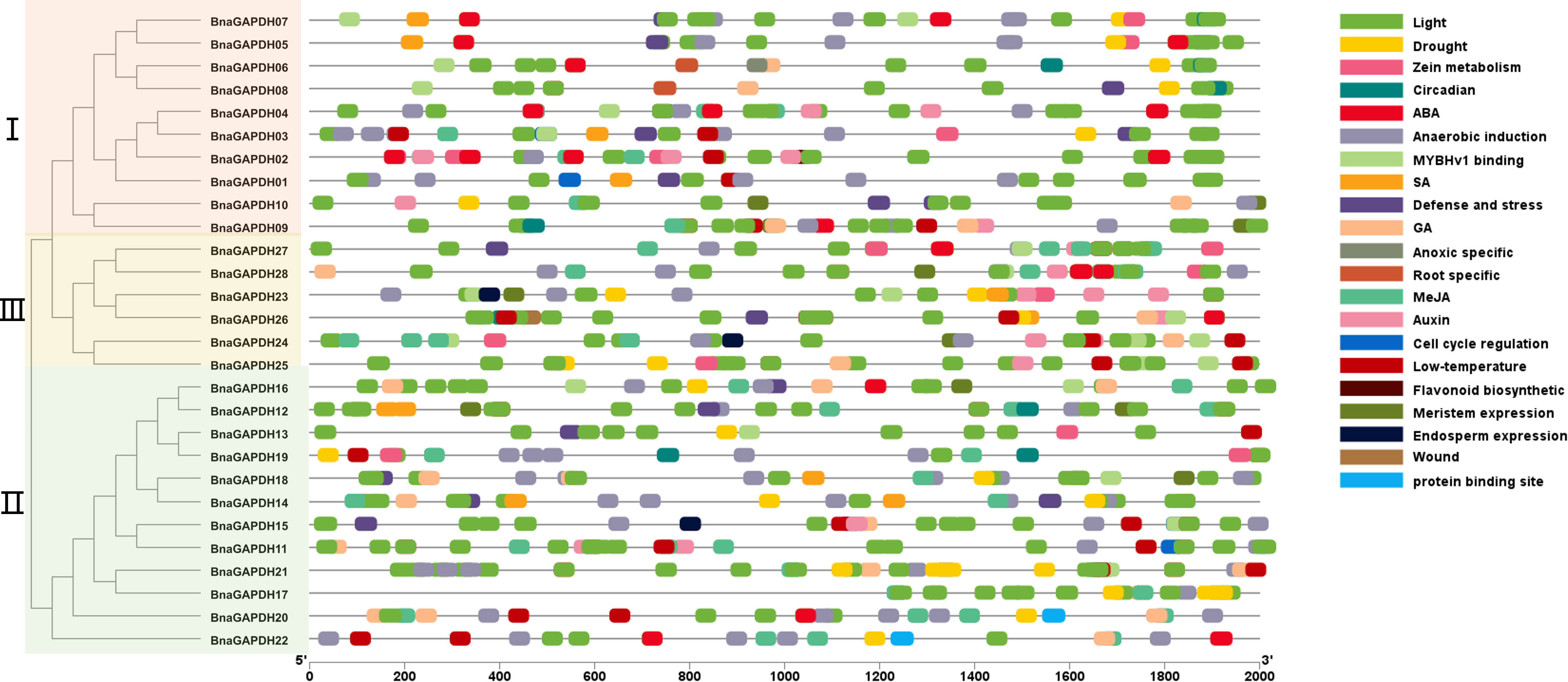

3.5 Cis-acting element analysis of BnaGAPDHs

The cis-elements in the 2-kb promoter regions were examined to recognize the gene functions and regulatory patterns of the BnGAPDH genes. A series of important cis-elements were identified (Figure 5 and Supplementary Table S5), including abiotic, hormone-, defense-, and development-responsive elements. Defense- and stress-related elements (TC-rich repeats) were predicted in the promoter regions of 13 BnaGAPDH genes, and 12 of these 13 genes additionally contained 1–3 hormone-responsive elements related to ABA (ABRE), SA (TCA-element), gibberellin (GARE-motif/P-box), and MeJA (TGACG/CGTCA-motif). Other cis-elements, such as drought-, wound-, low-temperature-, light-, and anaerobic-responsive elements, were also present in the promoter regions of BnGAPDH genes. These findings suggested that the expression of the BnGAPDH genes was regulated by various environmental factors.

Figure 5 Cis-elements in the 2.0-kb upstream regions of the BnGAPDH family genes in B. napus. The cis-acting regulatory element analysis in the promoter region (2.0 kb upstream of translation initiation site) of BnaGAPDH genes was performed using the PlantCARE database. The gray horizontal line represents the promoter region with the length of 2000 bp. The forward 2.0 kb of the gene coding start site is used as the starting point of promoter analysis, marked as 5’0bp, and to the coding starting site as the end point of the promoter region, marked as 2000bp.Different color boxes show different identified cis-elements. The details of the cis-elements are provided in Supplementary Table S5. Different color boxes show different identified cis-elements.

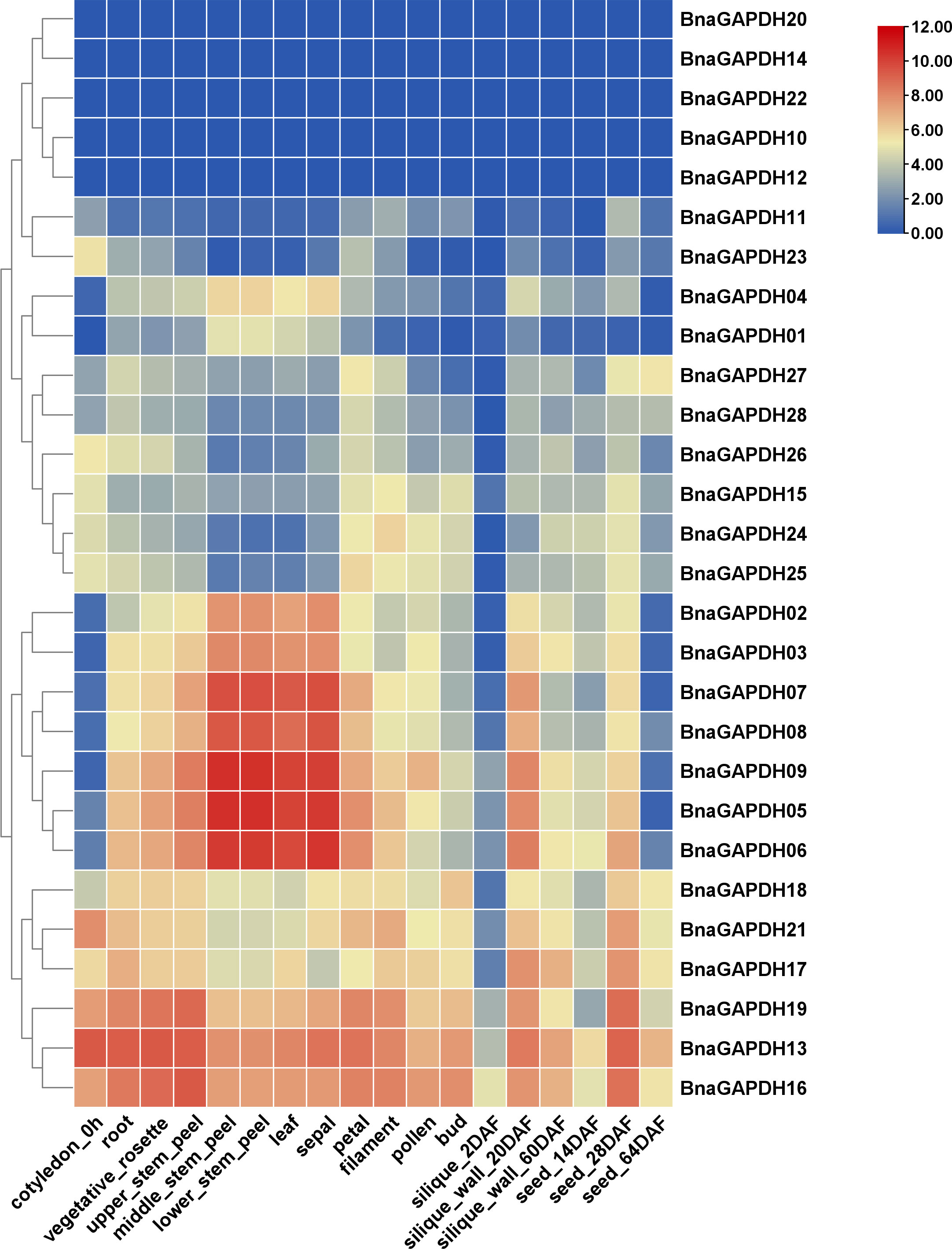

3.6 Expression patterns of BnaGAPDH genes in multiple tissues

The expression patterns of BnaGAPDHs were investigated in the cotyledons, roots, rosettes, stems, leaves, sepals, filaments, pollens, buds, siliques, silique walls, and seeds in different developing stages to assess the functional properties of GAPDH genes in B. napus (Figure 6 and Supplementary Table S6). The results showed that 3 genes were expressed (FPKM > 1) in at least 1 stage, 12 genes showed high expression (FPKM > 100), and 11 genes were lowly expressed (1 < FPKM < 100). All Group I BnaGAPDHs except for BnaGAPDH10 were highly expressed in stems, leaves, and sepals, but lowly expressed in cytoledon_0h, silique_20 DAF, and seed_64DAF. Six Group II genes (BnaGAPDH13, BnaGAPDH16, BnaGAPDH17, BnaGAPDH18, BnaGAPDH19, and BnaGAPDH21) were consistently expressed at high levels in most tissues, whereas Group III members exhibited relatively low expression levels in most tissues except the silique_20 DAF stage. The other five BnaGAPDH genes showed weak or no expression in different tissues. The diverse expression patterns among groups indicated that BnaGAPDH genes might exert different functions in growth and development.

Figure 6 Expression patterns of BnGAPDH family genes in different tissues. The expression data were gained from the RNA-seq data and calculated by fragments per kilobase of exon model per million (FPKM) values. The label below the heatmap represents the different tissues of B. napus ZS11, the right side of the heatmap represents different BnGAPDH genes. The color bar represents log2 (FPKM+1) values. All values were detailed in Supplementary Table S6.

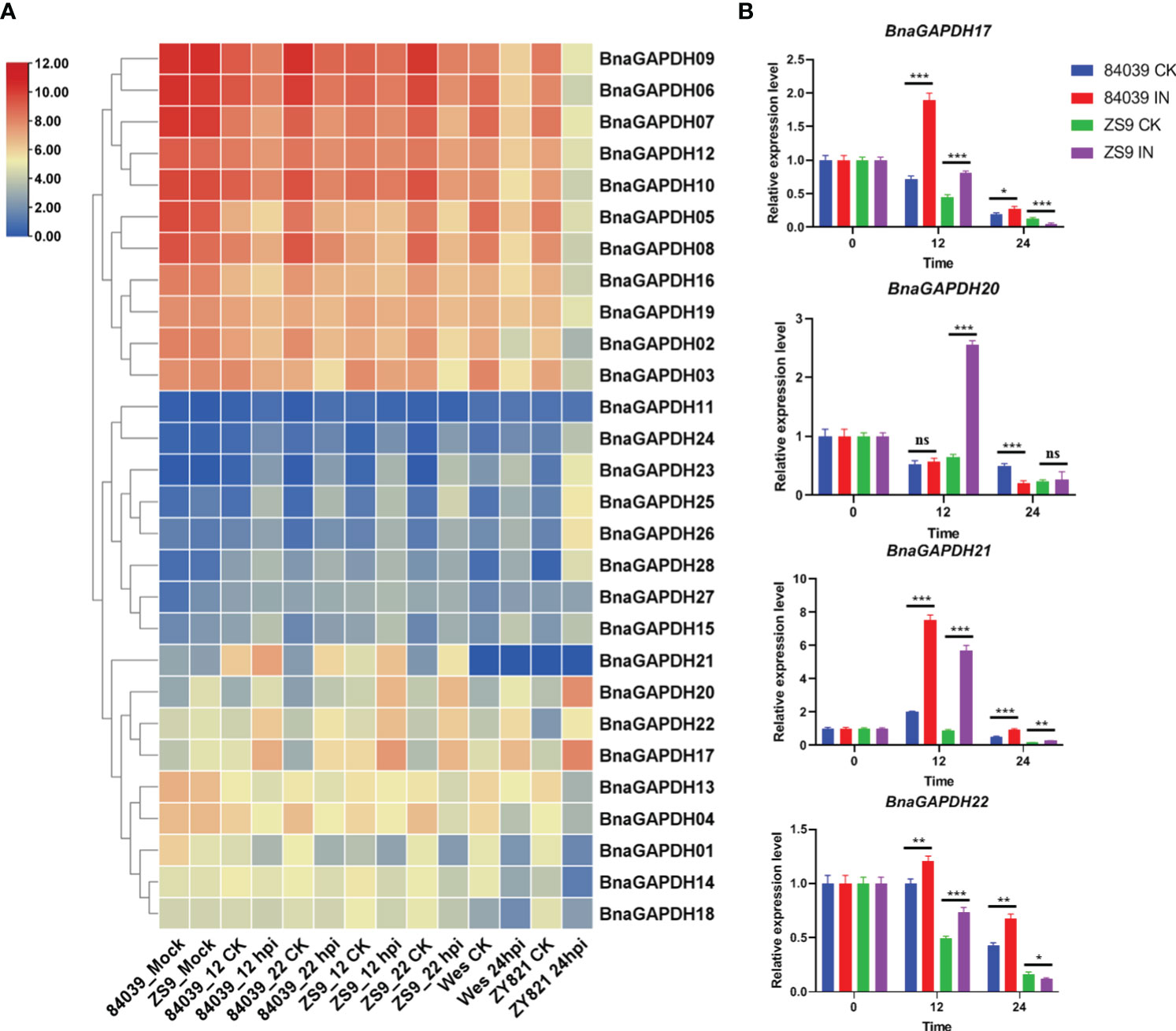

3.7 Expression patterns of BnGAPDH genes in response to S. sclerotiorum infection

The expression profiles of 28 BnaGAPDHs in four B. napus cultivars (sensitive cultivar 84039 and Westar and moderately resistant cultivar ZS9 and ZY821) inoculated with S. sclerotiorum were investigated to assess the role of BnaGAPDH genes in response to biotic stress responses (Figure 7A, Supplementary Table S7). BnaGAPDH02, BnaGAPDH03, BnaGAPDH05, BnaGAPDH06, BnaGAPDH07, BnaGAPDH08, BnaGAPDH09, BnaGAPDH10, BnaGAPDH12, BnaGAPDH16, and BnaGAPDH19 were highly expressed at all time points in four cultivars, but downregulated in the four cultivars after S. sclerotiorum infection compared with the control. Moreover, BnaGAPDH17, BnaGAPDH20, and BnaGAPDH22 were highly upregulated in the four cultivars after S. sclerotiorum infection, whereas BnaGAPDH01, BnaGAPDH04, BnaGAPDH13, BnaGAPDH14, and BnaGAPDH18 were downregulated, indicating that these genes might positively/negatively facilitate resistance against S. sclerotiorum in B. napus. While BnaGAPDH21 was not detected in Westar and ZY821, it was highly upregulated in cultivar 84039 and ZS9 during S. sclerotiorum infection. Other BnaGAPDHs showed lower expression in all samples. Taken together, BnaGAPDH genes exhibited variable expression patterns in response to necrotrophic biotic stress.

Figure 7 Expression patterns of BnaGAPDH genes in different cultivar of B. napus inoculated with S. sclerotiorum. (A) Expression patterns of BnaGAPDH genes in B. napus cultivars 84039, ZS9, Westar and ZY821 inoculated with S. sclerotiorum. Expression data were gained from the RNA-seq data and calculated by fragments per kilobase of exon model per million (FPKM) values. The expression levels of each gene were normalized by log2 (FPKM+1) in each sample, as indicated by different color rectangles. All values were detailed in Supplementary Table S7. (B) RT-qPCR analysis of BnGAPDH17, BnGAPDH20, BnGAPDH21 and BnGAPDH22 in B. napus cultivars 84039 and ZS9 inoculated with S. sclerotiorum. Data were calculated by the method of 2-ΔΔCT. * p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

To verify the aforementioned results, RT-qPCR was performed focusing on the expression levels of BnaGAPDH17, BnaGAPDH20, BnaGAPDH21, and BnaGAPDH22 in cultivars ZS9 and 84039 during S. sclerotiorum inoculation (Figure 7B). Our results closely mirror those obtained from the overall transcriptome sequencing, demonstrating varying degrees of upregulation for all four genes during S. sclerotiorum infection. In the moderately resistant cultivar ZS9, the four genes exhibited a consistent pattern of upregulation at the early stage (12 hpi), followed by downregulation at the later stage (24 hpi) in response to S. sclerotiorum infection. However, notable discrepancies were observed in the susceptible cultivar 84039. Specifically, both BnaGAPDH17 and BnaGAPDH22 showed significant upregulation at both 12 and 24 hpi in 84039, while BnaGAPDH20 displayed no significant upregulation and even underwent downregulation in the later stages of infection. Interestingly, the sole gene that exhibited consistent upregulation in both cultivars was BnaGAPDH21. These results imply that the response of these genes to S. sclerotiorum infection varies between cultivars, suggesting potential disparities in the underlying mechanisms of resistance to the pathogen between ZS9 and 84039.

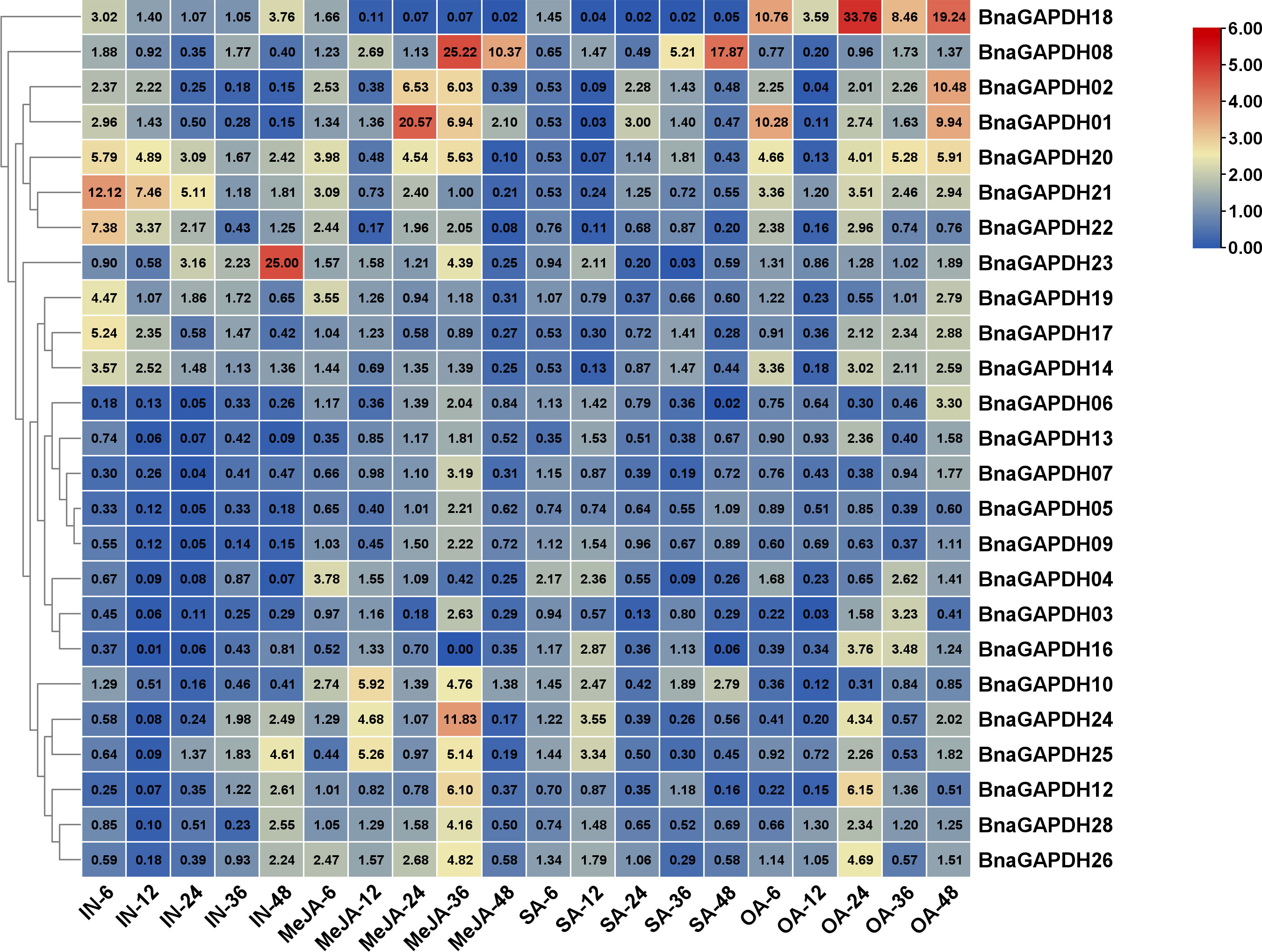

3.8 Expression patterns of BnGAPDH genes under hormonal and OA treatments

Phytohormones SA, MeJA, and OA, as key factors of plant–S. sclerotinia interaction, were used to treat B. napus seedlings to further investigate the possible involvement of BnaGAPDHs in signaling pathways during B. napus – S. sclerotirum ineraction (Figure 8). The relative expression levels of BnaGAPDHs detected by qRT-PCR showed that BnaGAPDHs were differentially affected by SA, MeJA, and OA with significant changes. After inoculation with S. sclerotiorum, the relative expression of BnaGAPDH01, BnaGAPDH02, BnaGAPDH14, BnaGAPDH17, BnaGAPDH18, BnaGAPDH19, BnaGAPDH20, BnaGAPDH21 and BnaGAPDH23 was slightly upregulated in the early stage of MeJA treatment and the late stage of OA treatment, but they were almost not induced by SA (Figure 8). BnaGAPDH18 was upregulated in the early stage (6 hpi) and late stage (48 hpi) of S. sclerotiorum infection. After OA treatment, the expression level showed an upward trend, but it was almost not affected by MeJA and SA. It was speculated that BnaGAPDH18 might participate in the resistance of S. sclerotiorum through an MeJA/SA-independent signaling pathway. On the contrary, BnaGAPDH08 was upregulated by MeJA and SA, whereas S. sclerotiorum infection and OA treatment had no significant effect on its expression. Taken together, the response of BnaGAPDHs to jasmonic acid (JA) and OA was consistent with that of S. sclerotiorum, but it tended to be independent of the SA signaling pathway.

Figure 8 RT-qPCR analysis of BnGAPDH genes under plant hormones treatments. Expression profiles of BnGAPDH genes in leaves of B. napus cultivar ZS9 during inoculation of S. sclerotiorum and treatment with MeJA, SA, and OA. Blue and red colors are used to represent low-to-high expression levels, and colors scales correspond to the fold-change values compared with the counterpart control. RT-qPCR data were calculated by the method of 2-ΔΔCT.

3.9 Subcellular localizations of BnaGAPDH17, BnaGAPDH20, BnaGAPDH21, and BnaGAPDH22

The aforementioned expression analysis revealed that four BnaGAPDHs (BnaGAPDH17, BnaGAPDH20, BnaGAPDH21, and BnaGAPDH22) exhibited a more significant up-regulation trend than other BnaGAPDHs in response to various stimuli, including cold stress, S. sclerotiorum infection, OA treatment, and MeJA treatment. Consequently, it became necessary to investigate their biological functions. Clarifying their intracellular localization is a prerequisite for understanding these functions. The transient expression assay in tobacco leaves revealed that BnaGAPDH17, BnaGAPDH20, and BnaGAPDH22 had similar localizations, primarily in the cytoplasm, and were also distributed near the nucleus and the plasma membrane (Figures 9A, B). However, they were not present in the inner nucleus. The aforementioned subcellular localization was consistent with the predicted results. In contrast, BnaGAPDH21not only clustered near the nucleus and plasma membrane but obviously clustered inside the nucleus (Figure 9A).

Figure 9 Subcellular localization of BnaGAPDH17, BnaGAPDH20, BnaGAPDH21 and BnaGAPDH22. (A) Subcellular localization of BnaGAPDH17, BnaGAPDH21 and BnaGAPDH22 under normal condition. (B) Subcellular localization of BnaGAPDH21 under normal condition (mock), S. sclerotiorum infection and H2O2 treatment. The nuclei were stained by 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI).

GAPC-types of A. thaliana are reported to be localized in different subcellular structures depending on their oxidation state. S. sclerotiorum infection often causes the production of oxidizing substances, such as oxygen anion and hydrogen peroxide (Schneider et al., 2018). Hence, it was speculated that S. sclerotiorum infection might cause the nuclear transfer of GAPC-type BnaGAPDHs. YFP-BnaGAPDHs were transiently expressed in tobacco, followed by the inoculation of S. sclerotiorum to test this hypothesis. As a positive control, tobacco leaves were treated with H2O2. Similar to AtGAPCs, confocal microscopy observation revealed that BnaGAPDH20 treated with H2O2 significantly aggregated in the nucleus (Figure 9B). YFP-BnaGAPDH20 was found to aggregate in the nucleus of individual cells at the disease–health junction of tobacco leaves infected by S. sclerotiorum (Figure 9B). However, the S. sclerotiorum infection induced nuclear translocalization was less than that of H2O2 treatment. Still, many cells were not aggregated in the nucleus even infected by S. sclerotiorum, which might be related to the complex interaction mechanism between S. sclerotiorum and plants.

4 Discussion

Plants have intricate and sophisticated signaling networks that are ubiquitous, similar to those observed in animals. These networks elicit diverse cellular responses to various input signals, including growth promotion and PCD. Plants require efficient regulatory systems that integrate environmental and developmental signals across various tissues to achieve equilibrium. The multifunctional central hub, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPC), plays a crucial role in detecting and counterbalancing metabolic and redox imbalances. Moreover, GAPDH facilitates various modifications of sensitive cysteine residues in a finely-tuned manner, responding to external stressors of different degrees and types (Schneider et al., 2018; Lazarev et al., 2020; Sirover, 2021). Compared with animals, plants harbor more GAPDH isoforms, potentially collaborating to facilitate precise signal transmission and response, thereby restoring and maintaining a dynamic balance (Henry et al., 2015; Xie et al., 2021). Ultimately, PCD is initiated as a last resort when metabolism spins out of control, serving to mitigate damage to surrounding cells.

Numerous studies have indicated that various subtypes of GAPDHs in Arabidopsis occupy specific subcellular locations depending on their oxidation state (Schneider et al., 2018). When the cellular redox state shifts toward oxidation under stress, a portion of the redox-sensitive GAPDH undergoes oxidation, prompting its relocation to the nucleus, potentially triggering changes in gene expression (Schneider et al., 2018). For example, GAPDH has been observed in the nuclei of root cells exposed to cadmium (Vescovi et al., 2013), as well as in calcium-stressed and unstressed tobacco BY-2 cells (Testard et al., 2016). The “moonlighting” functions of GAPDH have been elucidated in an increasing number of studies (Tristan et al., 2011; Nicholls et al., 2012; Sirover, 2012; Hildebrandt et al., 2015). In this study, the nuclear location of BnaGAPDH21 was observed in certain cells during S. sclerotiorum infection but not in others. S. sclerotiorum is an aggressive pathogenic fungus marked by a short biotrophic phase during the infection process. Both the fungus and hosts employ a complex array of regulatory mechanisms to generate and accumulate ROS for survival, with the plant encouraging ROS production to stave off the pathogen, but biotrophic or hemi-biotrophic pathogens tend to scavenge ROS for their own survival. However, the influence of S. sclerotiorum on ROS during early infection is obscure and may implicate intricate regulatory mechanisms. The precise transition point of S. sclerotiorum from biotrophic to necrotrophic growth is not well-defined. Consequently, in cells at the forefront of the plant –S. sclerotiorum interaction, the redox state might fluctuate significantly. Moreover, other complex biological processes, including signal transduction, gene expression regulation, and additional factors, may also contribute to the nuclear translocation of BnaGAPDH20 during plant–pathogen interactions. Thus, a multi-faceted exploration of the mechanisms governing plant–pathogen interactions is essential for a more comprehensive understanding of the reasons behind the nuclear translocation of BnaGAPDH20.

As a necrotrophic pathogen, S. sclerotiorum secretes cell wall–degrading enzymes and toxins such as OA to establish infestation (Magro et al., 1984; Heller and Tudzynski, 2011). Conversely, plants have developed a range of defense mechanisms involving signaling networks, enabling them to survive and maintain their fitness (Zeng et al., 2018). These defense responses commonly begin with the recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns by plant pattern recognition receptors, subsequently activating pattern-triggered immunity (PTI). Alternatively, the detection of effectors by plant resistance (R) gene products triggers effector-triggered immunity (Jones and Dangl, 2006; Henry et al., 2013). To date, the immune response mechanisms of B. napus to S. sclerotiorum have been limited to PTI, although several effectors have been identified (Xiao et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2019; Tang et al., 2020).

The induced resistance response in plants is regulated by a complex signaling network and involves the expression of a series of resistance-related genes. Specifically, in the B. napus−S. sclerotiorum pathosystem, B. napus employs a variety of signaling pathways, involving the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade reaction, ROS, SA, and JA, to activate resistance to S. sclerotiorum (Ding et al., 2021). Although some of the plant–S. sclerotiorum interaction mechanisms are now determined, these perceptions are still just the tip of the iceberg. There are several researches focusing on GAPDH’s functions of regulating gene expression including function as a translational suppressor of AT1R and mediates the effect of H2O2 on AT1R mRNA (Backlund et al., 2009), regulating cyclooxygenase-2 and endothelin-1expression by targeting mRNA stability possibly by a novel, redox-sensitive mechanism (Rodriguez-Pascual et al., 2008; Ikeda et al., 2012). The mechanism by which GAPDH regulates gene expression is not yet fully understood, but research has found that GAPDH acetylation may be required for GAPDH dependent apoptotic gene regulation involving p53, PUMA, Bax and p21 (Sirover, 2021). In this study, the association of GAPDHs with ROS, SA, and MeJA, as well as with S. sclerotiorum, strongly suggested an potential redox-sensitive mechanism of GAPDHs participate in the immune response of B. napus against S. sclerotiorum.

In this study, 12 out of 13 BnaGAPDH genes containing defense and stress response elements were also found to contain 1–3 types of hormone-responsive elements, indicating their diverse roles in various stress regulatory networks. Many studies have shown the involvement of GAPDHs with abiotic stresses besides their roles in the immune responses. In Arabidopsis, AtGAPDHs could interact with E3 ubiquitin ligase (SINAL7), which positively controlled drought resistance and delayed leaf senescence of Arabidopsis plants, revealing the involvement of GAPC in stress tolerance (Peralta et al., 2018). Furthermore, GAPDHs may play important roles in response to drought stress by interacting with PLDδ or pLDα1 to promote ABA-regulated stomata closure (Hong et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2020). Therefore, the identification of BnaGAPDHs interacting proteins is of great significance for further understanding their functional mechanisms in plant resistance to S. sclerotiorum.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Author contributions

JX: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RW: Data curation, Resources, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. XZ: Conceptualization, Investigation, Resources, Writing – review & editing. WZ: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft. YZ: Data curation, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. JL: Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. PZ: Conceptualization, Validation, Writing – review & editing. SC: Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Software, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. HL: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing – original draft. AW: Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. LC: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Characteristic Dry Crop Planting Resource Bank (Nursery) of Fujian Province, the Fundamental Scientific Research Project of Public Scientific Research Institution in Fujian Province (2022R1031001) and the Basic R & D Special Fund Business of Fujian Province (Grant No. 2023R1070).

Acknowledgments

We thank Shengyi Liu (Oil Crops Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences) for providing the seeds of Zhongshuang9 and 84039 and Martin B. Dickman for providing S. sclerotiorum 1980.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2024.1360024/full#supplementary-material

References

Anders, S., Pyl, P. T., Huber, W. (2015). HTSeq–a python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 31, 166–169. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu638

Aroca, A., Schneider, M., Scheibe, R., Gotor, C., Romero, L. C. (2017). Hydrogen sulfide regulates the cytosolic/nuclear partitioning of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase by enhancing its nuclear localization. Plant Cell Physiol. 58, 983–992. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcx056

Backlund, M., Paukku, K., Daviet, L., De Boer, R. A., Valo, E., Hautaniemi, S., et al. (2009). Posttranscriptional regulation of angiotensin ii type 1 receptor expression by glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase. Nucleic. Acids Res. 37 (7), 2346–2358. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp098

Bai, H., Lan, J. P., Gan, Q., Wang, X. Y., Hou, M. M., Cao, Y. H., et al. (2012). Identification and expression analysis of components involved in rice Xa21-mediated disease resistance signalling. Plant Biol. 14, 914–922. doi: 10.1111/j.1438-8677.2012.00585.x

Bailey, T. L., Boden, M. B., Fabian, A., Frith, M., Grant, C. E., Clementi, L., et al. (2009). MEME SUITE: tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, 202–208. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp335

Bayer, P. E., Hurgobin, B., Golicz, A. A., Chan, C. K., Yuan, Y., Lee, H., et al. (2017). Assembly and comparison of two closely related brassica napus genomes. Plant Biotechnol. J. 15, 1602–1610. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12742

Bruns, G. A., Gerald, P. S. (1976). Human glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase in man-rodent somatic cell hybrids. Science. 192, 54–56. doi: 10.1126/science.176725

Chen, G. D., Wang, L., Chen, Q., Qi, K. J., Yin, H., Cao, P., et al. (2019). PbrSLAH3 is a nitrate selective anion channel which is modulated by calcium-dependent protein kinase 32 in pear. BMC Plant Biol. 19, 1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12870-019-1813-z

Danshina, P. V., Schmalhausen, E. V., Avetisyan, A. V., Muronetz, V. I. (2001). Mildly oxidized glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase as a possible regulator of glycolysis. IUBMB Life. 51, 309–314. doi: 10.1080/152165401317190824

De Grassi, A., Lanave, C., Saccone, C. (2008). Genome duplication and gene-family evolution: the case of three OXPHOS gene families. Gene. 421, 1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2008.05.011

Demarse, N. A., Ponnusamy, S., Spicer, E. K., Apohan, E., Baatz, J. E., Ogretmen, B., et al. (2009). Direct binding of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase to telomeric DNA protects telomeres against chemotherapy-induced rapid degradation. J. Mol. Bio. 394 (4), 789–803. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.09.062

Ding, L. N., Li, T., Guo, X. J., Li, M. L., Xiao, Y., Cao, J., et al. (2021). Sclerotinia stem rot resistance in rapeseed: recent progress and future prospects. J. Agric. Food Chem. 69, 2965–2978. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c07351

Guo, L., Devaiah, S. P., Narasimhan, R., Pan, X. Q., Zhang, Y. Y., Zhang, W. H., et al. (2012). Cytosolic glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenases interact with phospholipase Dδ to transduce hydrogen peroxide signals in the arabidopsis response to stress. Plant Cell. 24, 2200–2212. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.094946

Han, S. J., Wang, Y., Zheng, X. Y., Jia, Q., Zhao, J. P., Bai, F., et al. (2015). Cytoplastic glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenases interact with ATG3 to negatively regulate autophagy and immunity in nicotiana benthamiana. Plant Cell. 27, 1316–1331. doi: 10.1105/tpc.114.134692

Hara, M., Agrawal, N., Kim, S., Cascio, M. B., Fujimuro, M., Ozeki, Y., et al. (2005). S-nitrosylated GAPDH initiates apoptotic cell death by nuclear translocation following Siah1 binding. Nat. Cell Biol. 7, 665–674. doi: 10.1038/ncb1268

Harada, N., Yasunaga, R., Higashimura, Y., Yamaji, R., Fujimoto, K., Moss, J., et al. (2007). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase enhances transcriptional activity of androgen receptor in prostate cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 22651–22661. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610724200

He, X., Xie, S., Xie, P., Yao, M., Liu, W., Qin, L. W., et al. (2019). Genome-wide identification of stress-associated proteins (SAP) with A20/AN1 zinc finger domains associated with abiotic stresses responses in brassica napus. Environ. Exp. Botany. 165, 108–119. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2019.05.007

Heller, J., Tudzynski, P. (2011). Reactive oxygen species in phytopathogenic fungi: signaling, development, and disease. Annu. Rev. Phytopathology. 49, 369–390. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-072910-095355

Henry, E., Fung, N., Liu, J., Drakakaki, G., Coaker, G. (2015). Beyond glycolysis: GAPDHs are multi-functional enzymes involved in regulation of ROS, autophagy, and plant immune responses. PloS Genet. 11, e1005199. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005199

Henry, E., Yadeta, K. A., Coaker, G. (2013). Recognition of bacterial plant pathogens: local, systemic and transgenerational immunity. New Phytol. 199 (4), 908–915. doi: 10.1111/nph.12214

Hildebrandt, T., Knuesting, J., Berndt, C., Morgan, B., Scheibe, R. (2015). Cytosolic thiol switches regulating basic cellular functions: GAPDH as an information hub? Biol. Chem. 396, 523–537. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2014-0295

Holtgrefe, S., Gohlke, J., Starmann, J., Druce, S., Klocke, S., Altmann, B., et al. (2008). Regulation of plant cytosolic glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase isoforms by thiol modifications. Physiologia Plantarum. 133, 211–228. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2008.01066.x

Hong, Y. Y., Pan, X. Q., Welti, R., Wang, X. M. (2008). The effect of phospholipase dalpha3 on arabidopsis response to hyperosmotic stress and glucose. Plant Signaling Behavior. 3, 1099–1100. doi: 10.4161/psb.3.12.7003

Ikeda, Y., Yamaji, R., Irie, K., Kioka, N., Murakami, A. (2012). Glyceral-dehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase regulates cyclooxygenase-2 expression by targeting mRNA stability. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 528, 141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2012.09.004

Jones, J. D., Dangl, J. L. (2006). The plant immune system. Nature 444 (7117), 323–329. doi: 10.1038/nature05286

Kaido, M., Abe, K., Mine, A., Hyodo, K., Taniguchi, T., Taniguchi, H., et al. (2014). GAPDH–a recruits a plant virus movement protein to cortical virus replication complexes to facilitate viral cell-to-cell movement. PloS Pathogens. 10, e1004505. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004505

Kalyaanamoorthy, S., Minh, B. Q., Wong, T. K. F., von Haeseler, A., Jermiin, L. S. (2017). ModelFinder: fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat. Methods 14, 587–589. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4285

Kim, D., Pertea, G., Trapnell, C., Pimentel, H., Kelley, R., Salzberg, S. L. (2013). TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol. 14, R36. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-4-r36

Kim, S. C., Guo, L., Wang, X. M. (2020). Nuclear moonlighting of cytosolic glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase regulates arabidopsis response to heat stress. Nat. Commun. 11, 3439–3453. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17311-4

Kozera, B., Rapacz, M. (2013). Reference genes in real-time PCR. J. Appl. Genet. 54, 391–406. doi: 10.1007/s13353-013-0173-x

Lazarev, V. F., Guzhova, I. V., Margulis, B. A. (2020). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase is a multifaceted therapeutic target. Pharmaceutics 12 (5), 416. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics12050416

Li, G. Q., Huang, H. C., Miao, H. J., Erickson, R. S., Jiang, D. H., Xiao, Y. N. (2006). Biological control of sclerotinia diseases of rapeseed by aerial applications of the mycoparasite Coniothyrium minitans. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 114, 345–355. doi: 10.1007/s10658-005-2232-6

Liu, T. F., Fang, H., Liu, J., Reid, S., Hou, J., Zhou, T. T., et al. (2017). Cytosolic glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenases play crucial roles in controlling cold-induced sweetening and apical dominance of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) tubers. Plant Cell Environment. 40, 3043–3054. doi: 10.1111/pce.13073

Luo, Y., Ge, C., Yang, M., Long, Y., Li, M. Y., Zhang, Y., et al. (2020). Cytosolic/plastid glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase is a negative regulator of strawberry fruit ripening. Genes. 11, 580–598. doi: 10.3390/genes11050580

Madeira, F., Park, Y. M., Lee, J., Buso, N., Gur, T., Madhusoodanan, N., et al. (2019). The EMBL-EBI search and sequence analysis tools APIs in 2019. Nucleic. Acids Res. 47, W636–W641. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz268

Magro, P., Marciano, P., Lenna, P. (1984). Oxalic acid production and its role in pathogenesis of sclerotinia sclerotiorum. FEMS Microbiol. Letters. 24, 9–12. doi: 10.1111/fml.1984.24.issue-1

Malik, W. A., Wang, X. G., Wang, X. L., Shu, N., Cui, R., Chen, X. G., et al. (2020). Genome-wide expression analysis suggests glutaredoxin genes response to various stresses in cotton. Int. J. Biol. Macromolecules. 153, 470–491. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.03.021

Mei, J., Qian, L., Disi, J. O., Yang, X., Li, Q., Li, J., et al. (2011). Identification of resistant sources against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in Brassica species with emphasis on B. oleracea. Euphytica 177, 393–399. doi: 10.1007/s10681-010-0274-0

Miao, L., Chen, C. L., Yao, L., Tran, J., Zhang, H. (2019). Genome-wide identification, characterization, interaction network and expression profile of GAPDH gene family in sweet orange (Citrus sinensis). PeerJ. 7, e7934. doi: 10.7717/peerj.7934

Morgante, C. V., Guimarães, P. M., Martins, A. C., Araújo, A. C., Leal-Bertioli, S. C., Bertioli, D. J., et al. (2011). Reference genes for quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction expression studies in wild and cultivated peanut. BMC Res. Notes. 4, 339–349. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-4-339

Muñoz-Bertomeu, J., Bermúdez, M. A., Segura, J., Ros, R. (2011). Arabidopsis plants deficient in plastidial glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase show alterations in abscisic acid (ABA) signal transduction: interaction between ABA and primary metabolism. J. Exp. Botany. 62, 1229–1239. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq353

Muñoz-Bertomeu, J., Cascales-Miñana, B., Irles-Segura, A., Mateu, I., Nunes-Nesi, A., Fernie, A. R., et al. (2010). The plastidial glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase is critical for viable pollen development in arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 152, 1830–1841. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.150458

Muñoz-Bertomeu, J., Cascales-Miñana, B., Mulet, J. M., Baroja-Fernández, E., Pozueta-Romero, J., Kuhn, J. M., et al. (2009). Plastidial glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency leads to altered root development and affects the sugar and amino acid balance in arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 151, 541–558. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.143701

Nakagawa, T., Hirano, Y., Inomata, A. (2002). Participation of a fusogenic protein. Glyceraldehyde-3-Phosphate dehydrogenase, in nuclear membrane assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 20395–20404. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210824200

Nicholls, C., Li, H., Liu, J. P. (2012). GAPDH: A common enzyme with uncommon functions. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 39, 674–679. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2011.05599.x

Nguyen, L. T., Schmidt, H. A., von Haeseler, A., Minh, B. Q. (2015). IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 268–274. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu300

Peralta, D. A., Araya, A., Gomez-Casati, D. F., Busi, M. V. (2018). Over-expression of SINAL7 increases biomass and drought tolerance, and also delays senescence in arabidopsis. J. Biotechnol. 283, 11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2018.07.013

Rius, S. P., Casati, P., Iglesias, A. A., Gomez-Casati, D. F. (2006). Characterization of an arabidopsis thaliana mutant lacking a cytosolic non-phosphorylating glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. Plant Mol. Biol. 61, 945–957. doi: 10.1007/s11103-006-0060-5

Rodríguez-Pascual, F., Redondo-Horcajo, M., Magán-Marchal, N., Lagares, D., Martínez-Ruiz, A., Kleinert, H., et al. (2008). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase regulates endothelin-1 expression by a novel, redox-sensitive mechanism involving mRNA stability. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28, 7139–7155. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01145-08

Rozewicki, J., Li, S., Amada, K. M., Standley, D. M., Katoh, K. (2019). MAFFT-DASH: Integrated protein sequence and structural alignment. Nucleic. Acids Res. 47, W5–W10. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz342z

Schneider, M., Knuesting, J., Birkholz, O., Heinisch, J. J., Scheibe, R. (2018). Cytosolic GAPDH as a redox-dependent regulator of energy metabolism. BMC Plant Biol. 18, 184. doi: 10.1186/s12870-018-1390-6

Sirover, M. A. (2012). Subcellular dynamics of multifunctional protein regulation: mechanisms of GAPDH intracellular translocation. J. Cell. Biochem. 113, 2193–2200. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24113

Sirover, M. A. (2021). The role of posttranslational modification in moonlighting glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase structure and function. Amino Acids 53, 507–515. doi: 10.1007/s00726-021-02959-z

Tang, L. G., Yang, G. G., Ma, M., Liu, X. F., Li, B., Xie, J. T., et al. (2020). An effector of a necrotrophic fungal pathogen targets the calcium-sensing receptor in chloroplasts to inhibit host resistance. Mol. Plant Pathology. 21, 686–701. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12922

Testard, A., Da-Silva, D., Ormancey, M., Pichereaux, C., Pouzet, C., Jauneau, A., et al. (2016). Calcium- and nitric oxide-dependent nuclear accumulation of cytosolic glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase in response to long chain bases in tobacco BY-2 cells. Plant Cell Physiol. 57, 2221–2231. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcw137

Tisdale, E. (2001). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase is required for vesicular transport in the early secretory pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 2480–2486. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007567200

Tristan, C., Shahani, N., Sedlak, T. W., Sawa, A. (2011). The diverse functions of GAPDH: views from different subcellular compartments. Cell. Signaling 23, 317–323. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.08.003

Vescovi, M., Zaffagnini, M., Festa, M., Trost, P., Lo-Schiavo, F., Costa, A. (2013). Nuclear accumulation of cytosolic glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase in cadmium-stressed arabidopsis roots. Plant Physiol. 162, 333–346. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.215194

Wang, Q., Lu, L., Zeng, M., Wang, D., Zhang, T. Z., Xie, Y., et al. (2022). Rice black-streaked dwarf virus P10 promotes phosphorylation of GAPDH (Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) to induce autophagy in laodelphax striatellus. Autophagy 18, 745–764. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2021.1954773

Wang, Z., Ma, L. Y., Cao, J., Li, Y. L., Ding, L. N., Zhu, K. M., et al. (2019). Recent advances in mechanisms of plant defense to sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Front. Plant Science. 10. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.01314

Wang, Y., Tang, H., Debarry, J. D., Tan, X., Li, J., Wang, X., et al. (2012). MCScanX: a toolkit for detection and evolutionary analysis of gene synteny and collinearity. Nucleic. Acids Res. 40, e49–e63. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1293

Xiao, X. Q., Xie, J. T., Cheng, J. S., Li, G. Q., Yi, X. H., Jiang, D. H., et al. (2014). Novel secretory protein ss-caf1 of the plant-pathogenic fungus sclerotinia sclerotiorum is required for host penetration and normal sclerotial development. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interactions: MPMI. 27, 40–55. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-05-13-0145-R

Xie, Q., Zhang, H., Hu, D., Liu, Q., Zuo, T., Zhang, Y., et al. (2021). Analysis of SI-related BoGAPDH family genes and response of BoGAPC to SI signal in brassica oleracea L. Genes 12, 1719–1741. doi: 10.3390/genes12111719

Yang, G. G., Tang, L. G., Gong, Y. D., Xie, J. T., Fu, Y. P., Jiang, D. H., et al. (2018). A cerato-platanin protein SsCP1 targets plant PR1 and contributes to virulence of sclerotinia sclerotiorum. New Phytologist. 217, 739–755. doi: 10.1111/nph.14842

Yang, S. M. (1959). An investigation on the host range and some ecological aspects of the Sclerotinia disease of rape plants. Acta Phytopathol. Sin. 5, 111–122. doi: 10.13926/j.cnki.apps.1959.02.006

Ying, F., Xue, Y. X., Du, P. X., Yang, S. S., Deng, X. P. (2017). Expression analysis and promoter methylation under osmotic and salinity stress of TaGAPC1 in wheat (Triticum aestivum L). Protoplasma. 254, 987–996. doi: 10.1007/s00709-016-1008-5

Zaffagnini, M., Fermani, S., Costa, A., Lemaire, S. D., Trost, P. (2013). Plant cytoplasmic GAPDH: redox post-translational modifications and moonlighting properties. Front. Plant Science. 4. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00450

Zeng, L. F., Deng, R., Guo, Z. P., Yang, S. S., Deng, X. P. (2016). Genome-wide identification and characterization of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase genes family in wheat (Triticum aestivum). BMC Genomics 17, 240. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-2527-3

Zeng, T., Dong, Z. F., Liu, S. J., Wan, R. P., Tang, L. J., Liu, T., et al. (2014). A novel variant in the 3’ UTR of human SCN1A gene from a patient with dravel syndrome decreases mRNA stability mediated by GAPDH’s binding. Hum. Genet. 133, 801–811. doi: 10.1007/s00439-014-1422-8

Zeng, H. Q., Xie, Y. W., Liu, G. Y., Lin, D. Z., He, C. Z., Shi, H. T. (2018). Molecular identification of GAPDHs in cassava highlights the antagonism of MeGAPCs and MeATG8s in plant disease resistance against cassava bacterial blight. Plant Mol. Biol. 97, 201–214. doi: 10.1007/s11103-018-0733-x

Zhang, X. H., Rao, X. L., Shi, H. T., Li, R. J., Lu, Y. T. (2011). Overexpression of a cytosolic glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene OsGAPC3 confers salt tolerance in rice. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Culture 107, 1–11. doi: 10.1007/s11240-011-9950-6

Zhang, L., Zhang, H. W., Yang, S. S. (2020). Cytosolic TaGAPC2 enhances tolerance to drought stress in transgenic arabidopsis plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 7499. doi: 10.3390/ijms21207499

Zheng, L., Roeder, R. G., Luo, Y. (2003). S phase activation of the histone H2B promoter by OCA-S, a coactivator complex that contains GAPDH as a crucial component. Cell 114 (2), 255–266. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00552-X

Keywords: Brassica napus, GAPDH, gene family, Sclerotinia sclerotiorum, subcellular localization, nuclear translocation

Citation: Xu J, Wang R, Zhang X, Zhuang W, Zhang Y, Lin J, Zhan P, Chen S, Lu H, Wang A and Liao C (2024) Identification and expression profiling of GAPDH family genes involved in response to Sclerotinia sclerotiorum infection and phytohormones in Brassica napus. Front. Plant Sci. 15:1360024. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2024.1360024

Received: 22 December 2023; Accepted: 12 April 2024;

Published: 30 April 2024.

Edited by:

Douglas Jardim-Messeder, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, BrazilReviewed by:

Jia-Gang Wang, Shanxi Agricultural University, ChinaJiatao Xie, Huazhong Agricultural University, China

Copyright © 2024 Xu, Wang, Zhang, Zhuang, Zhang, Lin, Zhan, Chen, Lu, Wang and Liao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Changjian Liao, bGlhb2NqMTk3OEAxNjMuY29t; Airong Wang, YWlyb25nd0BmYWZ1LmVkdS5jbg==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Jing Xu

Jing Xu Rongbo Wang

Rongbo Wang Xiong Zhang

Xiong Zhang Wei Zhuang1

Wei Zhuang1 Yang Zhang

Yang Zhang Changjian Liao

Changjian Liao