- Coastal Salinity Tolerant Grass Engineering and Technology Research Center, Ludong University, Yantai, China

Introduction: Potassium and phosphorus are essential macronutrients for plant growth and development. However, most P and K exist in insoluble forms, which are difficult for plants to directly absorb and utilize, thereby resulting in growth retardation of plants under P or K deficiency stress. The Aspergillus aculeatus fungus has growth-promoting characteristics and the ability to dissolve P and K.

Methods: Here, to investigate the physiological effects of A. aculeatus on bermudagrass under P or K deficiency, A. aculeatus and bermudagrass were used as experimental materials.

Results and discussion: The results showed that A. aculeatus could promote tolerance to P or K deficiency stress in bermudagrass, decrease the rate of leaf death, and increase the contents of crude fat as well as crude protein. In addition, A. aculeatus significantly enhanced the chlorophyll a+b and carotenoid contents. Moreover, under P or K deficiency stress, bermudagrass inoculated with A. aculeatus showed higher N, P, and K contents than non-inoculated plants. Furthermore, exogenous A. aculeatus markedly decreased the H2O2 level and CAT and POD activities. Based on our results, A. aculeatus could effectively improve the forage quality of bermudagrass and alleviate the negative effects of P or K deficiency stress, thereby playing a positive economic role in the forage industry.

1 Introduction

Phosphorus (P) and potassium (K) are the major macronutrients for plant growth and development (Wang et al., 2021). P and K play dominant roles in maintaining a variety of physiological metabolic processes in plants, including nucleic acid synthesis, energy metabolites, membrane lipids, photosynthesis, membrane polarization, and protein biosynthesis (Clarkson and Hanson, 1980; Poirier and Bucher, 2002). However, P and K in soil exist in the form of insoluble K, which cannot be directly absorbed and used by plants (Illmer and Schinner, 1995; Meena et al., 2016). Therefore, it is of great interest to investigate management strategies that can improve the availability of phosphorus and potassium.

As fundamental mineral nutrients, P and K have been documented to be involved in plant photosynthesis processes (Wang et al., 2012; Krishnaraj and Dahale, 2014). Previous investigators proposed that P deficiency triggered reddish leaf and necrosis on the tips of old leaves and could result in a decrease in the maximum PSII efficiency and electron transport rate (Guo et al., 2002; Luiz et al., 2018). Chlorosis along the leaf margins is an obvious symptom of K deficiency. In severe cases, the leaf will turn yellow and fall off (Meena et al., 2016). Previous research has reported that K deficiency disrupts leaf photosynthetic performance and causes a lower net photosynthetic rate and stomatal conductance, which directly affects the yield of plants (Zhao et al., 2016).

A deficiency of mineral nutrition in plants could cause oxidative stress due to the disequilibrium between the scavenging and production of excess reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Cakmak, 2005; Shin et al., 2005). An excess of ROS triggers protein denaturation, cell membrane lipid peroxidation, and nucleic acid degradation, which restrains normal cellular physiological processes (Mittova et al., 2002). Fortunately, ROS can be scavenged through synergistic and interactive enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant defense systems. The enzymatic systems mainly include peroxidase (POD), superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), ascorbate peroxidase (APX), and glutathione peroxidase (GPX) (Apel and Hirt, 2004).

Whenever the soil cannot adequately supply the P and K required for plant growth, people must supplement soil reserves with chemical P and K fertilizers. However, not all fertilizers that have been applied to the soil are fully taken up and utilized by plants. A portion of the applied fertilizers are left behind, thereby causing environmental contamination, such as eutrophication, and soil fertility depletion (Sharma et al., 2013; Meena et al., 2016; Kumar et al., 2021). Therefore, the emergence of phosphorus and potassium fertilizers has not given the ultimate solution. Such environmental concerns have triggered the exploration of sustainable P and K nutrition in plants. Given this circumstance, phosphate-solubilizing microorganisms have been considered an eco-friendly and cost-effective approach for the supply of P nutrition to plants (Sharma et al., 2013; Meena et al., 2016; Garcia et al., 2017). Mounting evidence suggests that P-solubilizing microorganisms (such as Azotobacter, Bradyrhizobium, Penicillium, and Aspergillus) can convert insoluble P into the bioavailable form through various mechanisms of solubilization and mineralization (Bargaz et al., 2018). Similarly, diverse groups of K-solubilizing microorganisms (Bacillus mucilaginosus, Aspergillus terreus, and Aspergillus niger) were proven to be involved in solubilizing the insoluble forms of K into available forms that are directly absorbed and utilized by plants (Prajapati and Modi, 2012; Gundala et al., 2013; Zarjani et al., 2013). Therefore, improvement of P and K utilization efficiency provides a potential strategy to overcome the adverse effects of P and K deficiencies. Investigation of the characteristics of fungi in dissolving P and K is an important prerequisite to improve plant nutrient utilization efficiency.

Aspergillus aculeatus is isolated from the rhizosphere of bermudagrass in heavy metal-contaminated areas (Xie et al., 2014). Our previous study proved that A. aculeatus can facilitate plant growth by producing indole-3-acetic acid, ACC deaminase, and siderophores (Xie et al., 2017). In addition, we have demonstrated that the fungus possessed P- and K-solubilizing characteristics, which accelerated the uptake and utilization of P and K nutrient elements, thereby promoting the growth and development of plants (Li et al., 2019; Li et al., 2021). However, the critical function of A. aculeatus in increasing the performance of bermudagrass exposed to P and K deficiency is still ambiguous. Bermudagrass [Cynodon dactylon (L.) Pers] is a typical warm season turfgrass and forage and is widely used in urban greening, sports fields, slope protection, and animal husbandry due to its high reproduction rate, short-term turf establishment, and strong mechanical stress resistance (Fan et al., 2014; Shi et al., 2014).

The objective of this experiment was to explore A. aculeatus-mediated protective responses to P or K deficiency stress in bermudagrass. We measured important physiological indicators of P or K deficiency stress, such as biomass, dead leaf rate, chlorophyll, carotenoids, forage quality, ion content, and antioxidant enzyme activities.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Culture of bermudagrass and Aspergillus aculeatus

The experimental materials were obtained from the artificially bred bermudagrass ‘Wrangler’ in the coastal grass germplasm resources and breeding base located in Ludong University, Yantai City, Shandong Province. The fourth to sixth stem segments (three stem segments) of the biological upper end of the bermudagrass were selected, and stems with the same length and thickness were inserted into the pots (10 cm in diameter and 15 cm in height) on 25 July 2021. All the materials were placed in a plant growth incubator at 30°C/25°C (day/night), with a 14-h photoperiod, 400 μmol photons m−2 s−1 of light intensity, and 60% relative humidity for 7 weeks to establish the roots and leaves. The grass was irrigated with 0.5× Hoagland nutrient solution every 2 days and cut based on a one-third principle. Aspergillus aculeatus was cultured and massively propagated in a Martin liquid medium according to our previous study (Xie et al., 2017).

2.2 Experimental treatment

A mixture of sand and sawdust (v:v = 3:1) was used as the growth substance for this experiment. Subsequently, on 10 September 2021, all the substances were sterilized at 127°C for 1 h in an autoclave and then dispensed into 24 pots (10 cm in diameter and 18 cm in height) with 550 g of the mixed matrix. On 12 September 2021, all the roots and shoots of the materials were washed and trimmed, and the length or height was maintained at 8 and 10 cm, respectively. The initial weight was recorded as W0, the trimmed plants were transferred into the above pots, and the 0.5× Hoagland nutrient solution (not present at the source of phosphorus or potassium, i.e., P or K deficiency treatment), was used to irrigate the plants every 2 days (100 ml pot−1). For the P deficiency experiment, tricalcium phosphate was evenly mixed into the growth substance at a concentration of 5 g per pot before the plants were transplanted. Four groups and three replicates were designed, including P0A0 (no tricalcium phosphate and A. aculeatus treatment), P0A1 (only A. aculeatus), P1A0 (only tricalcium phosphate), and P1A1 (tricalcium phosphate and A. aculeatus treatment). In the same way, for the K deficiency experiment, K-feldspar was evenly mixed into the growth substance at a concentration of 5 g per pot before the plants were transplanted. The four groups and three replicates were designed, including K0A0 (no K-feldspar and A. aculeatus treatment), K0A1 (only A. aculeatus), K1A0 (only K-feldspar), and K1A1 (K-feldspar and A. aculeatus treatment). For the inoculated A. aculeatus treatment groups, 100 ml of fungal spore suspension was inoculated into the growth substances. The treatment lasted for 4 weeks, and then the plants were harvested for further analysis on 10 October 2021.

2.3 Determination of growth parameters and forage quality

For growth biomass (GB) determination, the whole bermudagrass (including aboveground and underground) were washed and weighed (W1) at the end of the experiment. GB (kg day−1) = (W1 – W0)/D. W0 is the fresh weight before treatment, W1 is the fresh weight at the end of treatment, and D is the treatment days. To calculate the dead leaf rate (DLR), the leaf biomass (LB) and dead leaf biomass (DLB) of bermudagrass were weighed and recorded. DLR = DLB/LB × 100%.

For crude protein content measurement, the dried samples (0.20 g) were digested with 10 ml of H2SO4 using a graphite digestion apparatus (SH220N; Jinan Hanon, Shandong, China). The crude protein content was measured by an automatic Kjeldahl apparatus (Hanon K9860). Crude protein content (%) = N content × 6.25 × 100%.

To assess the crude fat content, the dried sample powder was weighed and measured with the Soxhlet extraction method. The samples were mixed with 50 ml of petroleum ether and dried in an oven at 120°C for 3 h with a Soxhlet apparatus (SOX406; Jinan Hanon, Shandong, China), and the residue was weighed and recorded.

2.4 Determination of ion content

To measure the N, P, and K contents, dried samples of the leaves (0.20 g) were digested with 10 ml of 99% sulfuric acid (H2SO4) in a graphite digestion apparatus. The contents of P and N were determined by a fully automatic intermittent chemical analyzer (SmartChem 200; AMS Alliance, Guidonia, Rome, Italy) (Zhang et al., 2020). The K content was assessed with flame photometry (Jackson, 1973).

2.5 Determination of chlorophyll and carotenoid content

Chlorophyll and carotenoids were extracted with dimethyl sulfoxide from all leaf segments (200 mg) and were determined using ultraviolet spectrophotometry (UV1700; Meixi, Shanghai, China) according to the method of Wellburn (1994).

2.6 Determination of antioxidant enzyme activity

Antioxidant enzymes were extracted at 4°C using 200 mg of tissue from the fresh samples of bermudagrass leaves. Plant samples were homogenized with 8 ml of phosphate buffer (pH = 7.8) and were centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 20 min, and then the supernatants were collected for the determination of the activities of antioxidant enzymes. POD activity was assayed by measuring the increase in absorbance at 470 nm with guaiacol as the substrate. CAT activity was determined by calculating the substrate consumption of H2O2 in absorbance at 240 nm (Hu et al., 2011). The content of H2O2 was determined according to the method of the hydrogen peroxide kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, A064, Nanjing, China), and the absorbance value at 405 nm was measured with a spectrophotometer to calculate the content of H2O2.

2.7 Statistical analysis

The raw data of the whole experiment were statistically analyzed with one-way ANOVA using SPSS software (Statistical Product and Service Solutions, version 20; IBM, Chicago, United States). The overall significance of the treatment was tested by the SNK test at the p <0.05 level. Correlation analysis was performed using the Pearson method.

3 Results

3.1 Phenotypic characteristics

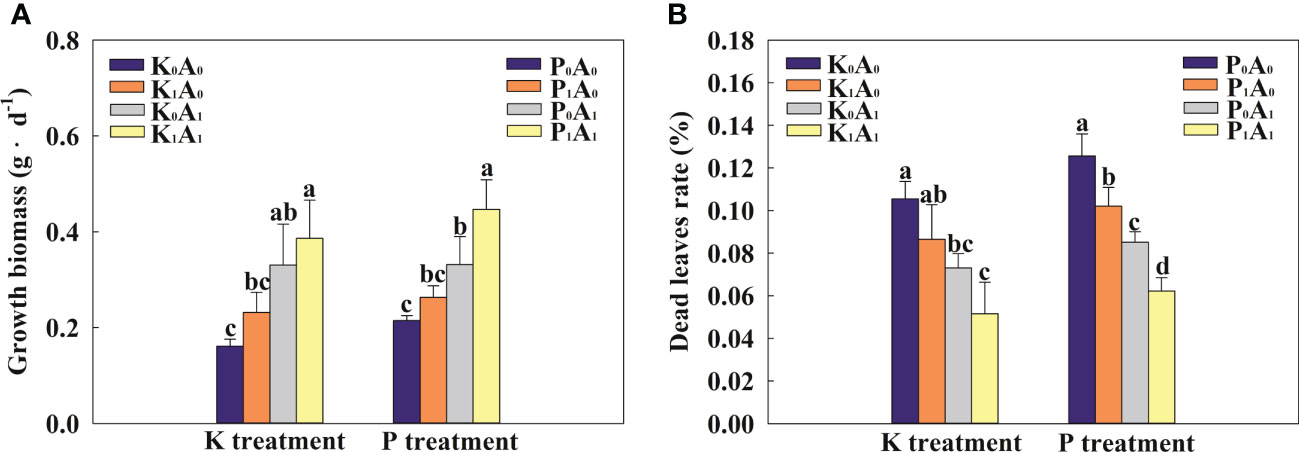

Phosphorus and potassium play an important role in the growth and development of plants. As shown in Figure 1A, the growth biomass of bermudagrass was significantly increased by 105.4% in the K0A1 group compared with the K0A0 treatment. In addition, the K1A1 treatment significantly enhanced the growth of bermudagrass by 66.7% compared with the K1A0 treatment. At the same time, bermudagrass biomass had an obvious increase (by 69.7%) in the P1A1 group compared with the P1A0 regime. In the K treatment group, compared with the K0A0 group, the dead leaf rate of bermudagrass was significantly reduced by 44.3% in the K0A1 group (Figure 1B). K1A1 treatment significantly improved the growth of bermudagrass under the K1A0 stress, which showed a significant decrease of 40.4% in the dead leaf rate. Similarly, P1A1 treatment showed a significant decrease of 39.0% in the rate of dead leaf compared with the P1A0 group. Taken together, A. aculeatus could enhance the growth situation of bermudagrass by improving biomass and decreasing the dead leaf rate under P- or K-deficient conditions.

Figure 1 Effects of Aspergillus aculeatus on growth biomass (A) and death leaf rate (B) of bermudagrass under K or P deficiency stress. K0A0 represents no potassium feldspar and A. aculeatus treatment; K1A0 represents only potassium feldspar treatment; K0A1 represents only A. aculeatus treatment; K1A1 represents potassium feldspar + A. aculeatus treatment; P0A0 represents no tricalcium phosphate and A. aculeatus treatment; P1A0 represents only tricalcium phosphate treatment; P0A1 represents only A. aculeatus treatment; P1A1 represents tricalcium phosphate + A. aculeatus treatment. Columns marked with the same small letter indicate insignificant differences between the four treatment groups (p < 0.05).

3.2 Chlorophyll and carotenoid contents of bermudagrass

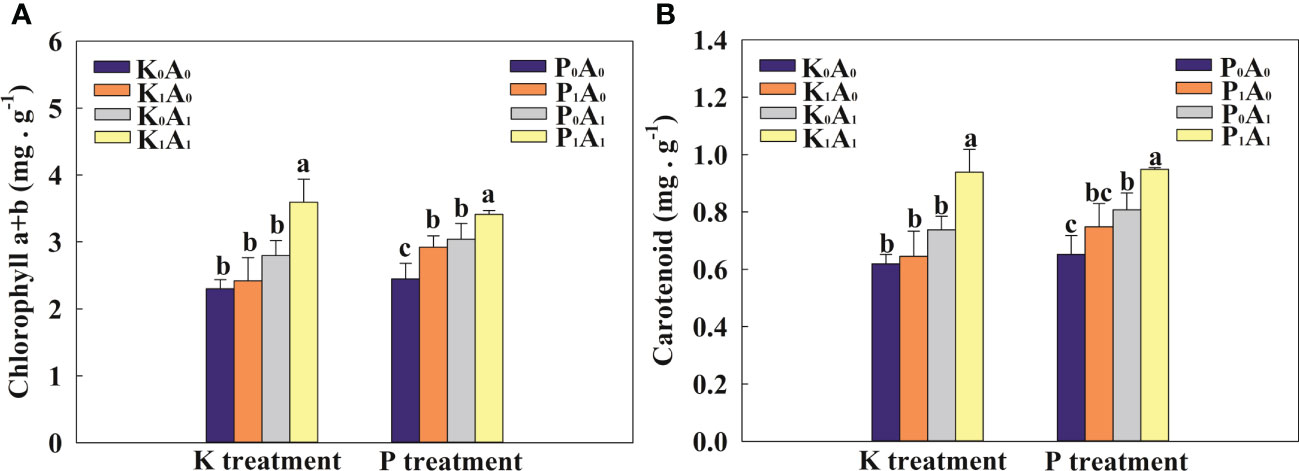

Under K-deficient conditions, the chlorophyll a+b and carotenoid contents were not obviously different in the K0A0, K1A0, and K0A1 groups (Figure 2). Nevertheless, the K1A1 treatment significantly increased the chlorophyll a+b and carotenoid contents of bermudagrass by 48.5% and 45.4%, respectively, compared with the K1A0 treatment. Similarly, under P-deficient conditions, the chlorophyll a+b and carotenoid contents were increased by 30.1% and 23.6% in inoculated plants (P0A1 treatment) compared with the P0A0 treatment. Compared with the P1A0 treatment, the chlorophyll a+b and carotenoid contents in the P1A1 group increased remarkably (16.7% and 26.9%, respectively) (Figure 2). These results implied that A. aculeatus promoted the biosynthesis of chlorophyll a+b and carotenoid contents through its P- or K-releasing characteristics.

Figure 2 Effects of Aspergillus aculeatus on chlorophyll (A) and carotenoid (B) contents of bermudagrass under K or P deficiency stress. K0A0 represents no potassium feldspar and A. aculeatus treatment; K1A0 represents only potassium feldspar treatment; K0A1 represents only A. aculeatus treatment; K1A1 represents potassium feldspar + A. aculeatus treatment; P0A0 represents no tricalcium phosphate and A. aculeatus treatment; P1A0 represents only tricalcium phosphate treatment; P0A1 represents only A. aculeatus treatment; P1A1 represents tricalcium phosphate + A. aculeatus treatment. Columns marked with the same small letter indicate insignificant differences between the four treatment groups (p < 0.05).

3.3 Forage quality

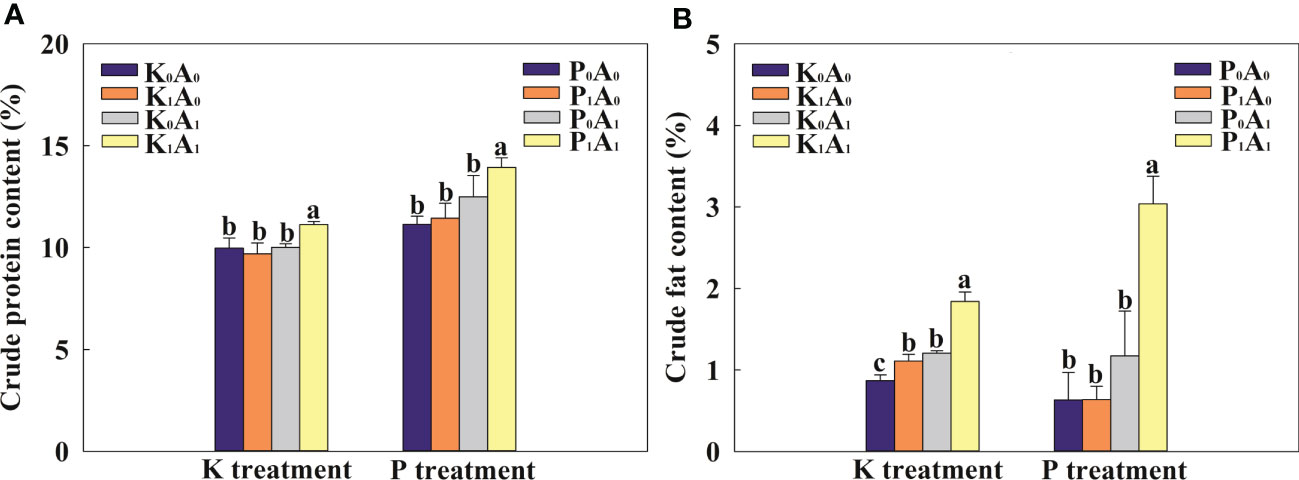

The A. aculeatus treatment obviously increased the crude fat content of bermudagrass by 38.6% compared with the K0A0 treatment and had no effect on crude protein content under K deficiency stress (Figure 3). However, A. aculeatus inoculations combined with K-feldspar (K1A1 regime) remarkably elevated the crude protein and crude fat content by 14.9% and 65.7%, respectively, in bermudagrass, compared with the K-feldspar treatment (K1A0 group). Similarly, under P-deficient conditions, the P1A1 treatment significantly increased the crude protein and crude fat contents by 21.8% and 377.7%, respectively, compared with the P1A0 treatment. In the environment of K or P deficiency, exogenous A. aculeatus effectively increased the contents of crude protein and crude fat and then improved the forage quality of bermudagrass.

Figure 3 Effects of Aspergillus aculeatus on crude protein (A) and crude fat (B) contents of bermudagrass under K or P deficiency stress. K0A0 represents no potassium feldspar and A. aculeatus treatment; K1A0 represents only potassium feldspar treatment; K0A1 represents only A. aculeatus treatment; K1A1 represents potassium feldspar + A. aculeatus treatment; P0A0 represents no tricalcium phosphate and A. aculeatus treatment; P1A0 represents only tricalcium phosphate treatment; P0A1 represents only A. aculeatus treatment; P1A1 represents tricalcium phosphate + A. aculeatus treatment. Columns marked with the same small letter indicate insignificant differences between the four treatment groups (p < 0.05).

3.4 Ion homeostasis

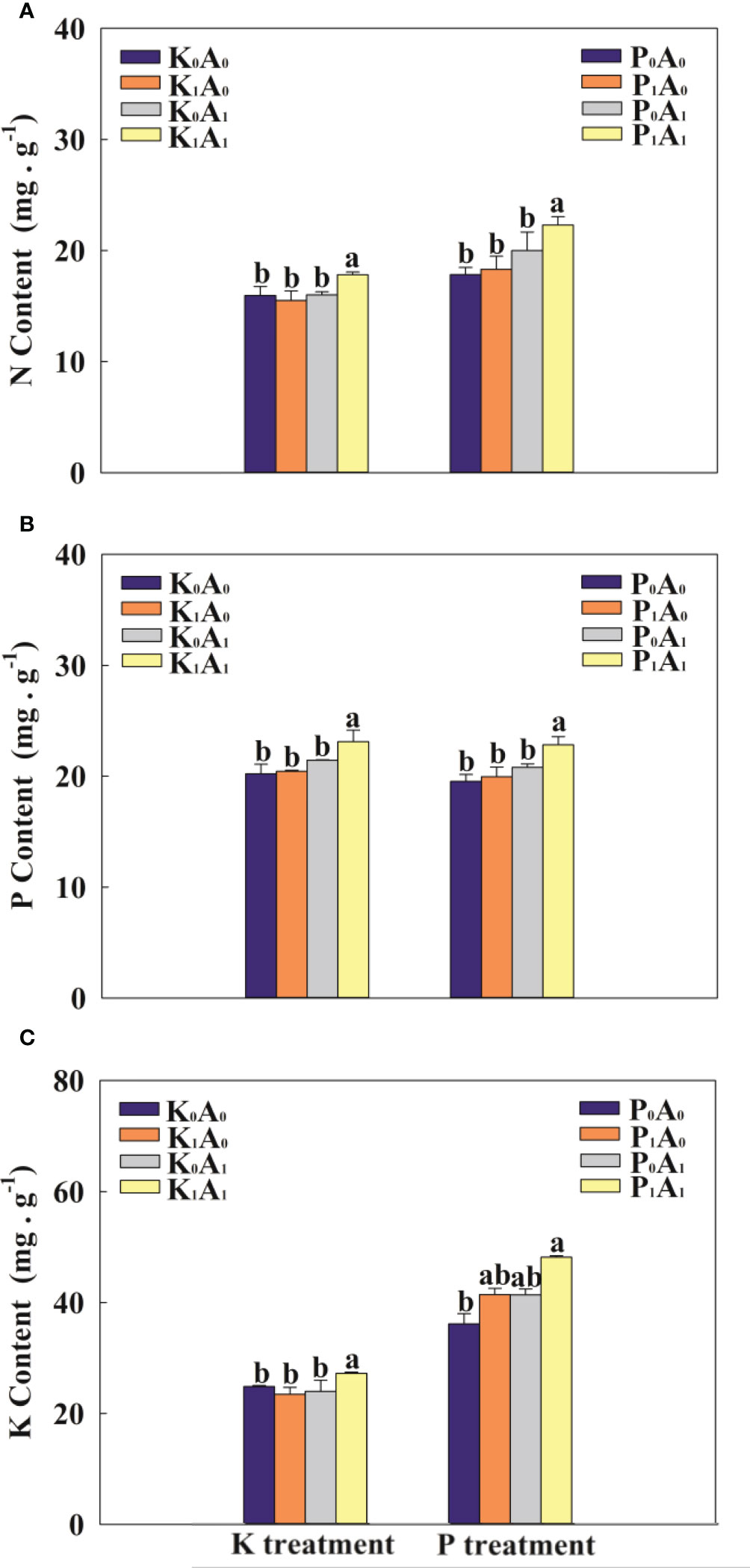

Compared with K0A0, the K1A0 and K0A1 treatments had no obvious effect on the contents of N, P, and K in the leaves (Figure 4). The K1A1 treatment markedly enhanced the contents of N, P, and K in the leaves of bermudagrass by 14.9%, 13.2%, and 16.1%, respectively, compared with the K1A0 treatment. Under P-deficient conditions, the P1A1 treatment significantly increased the contents of N, P, and K in the leaves of bermudagrass by 21.8%, 14.4%, and 16.3%, respectively, compared with the P1A0 group (Figure 4). These results suggest that A. aculeatus can dissolve insoluble K and P into soluble K and P, thereby promoting the uptake of K and P and enhancing the contents of N, P, and K in the leaves of bermudagrass.

Figure 4 Effects of Aspergillus aculeatus on N content (A), P content (B) and K content (C) of bermudagrass under K or P deficiency stress. K0A0 represents no potassium feldspar and A. aculeatus treatment; K1A0 represents only potassium feldspar treatment; K0A1 represents only A. aculeatus treatment; K1A1 represents potassium feldspar + A. aculeatus treatment; P0A0 represents no tricalcium phosphate and A. aculeatus treatment; P1A0 represents only tricalcium phosphate treatment; P0A1 represents only A. aculeatus treatment; P1A1 represents tricalcium phosphate + A. aculeatus treatment. Columns marked with the same small letter indicate insignificant differences between the four treatment groups (p < 0.05).

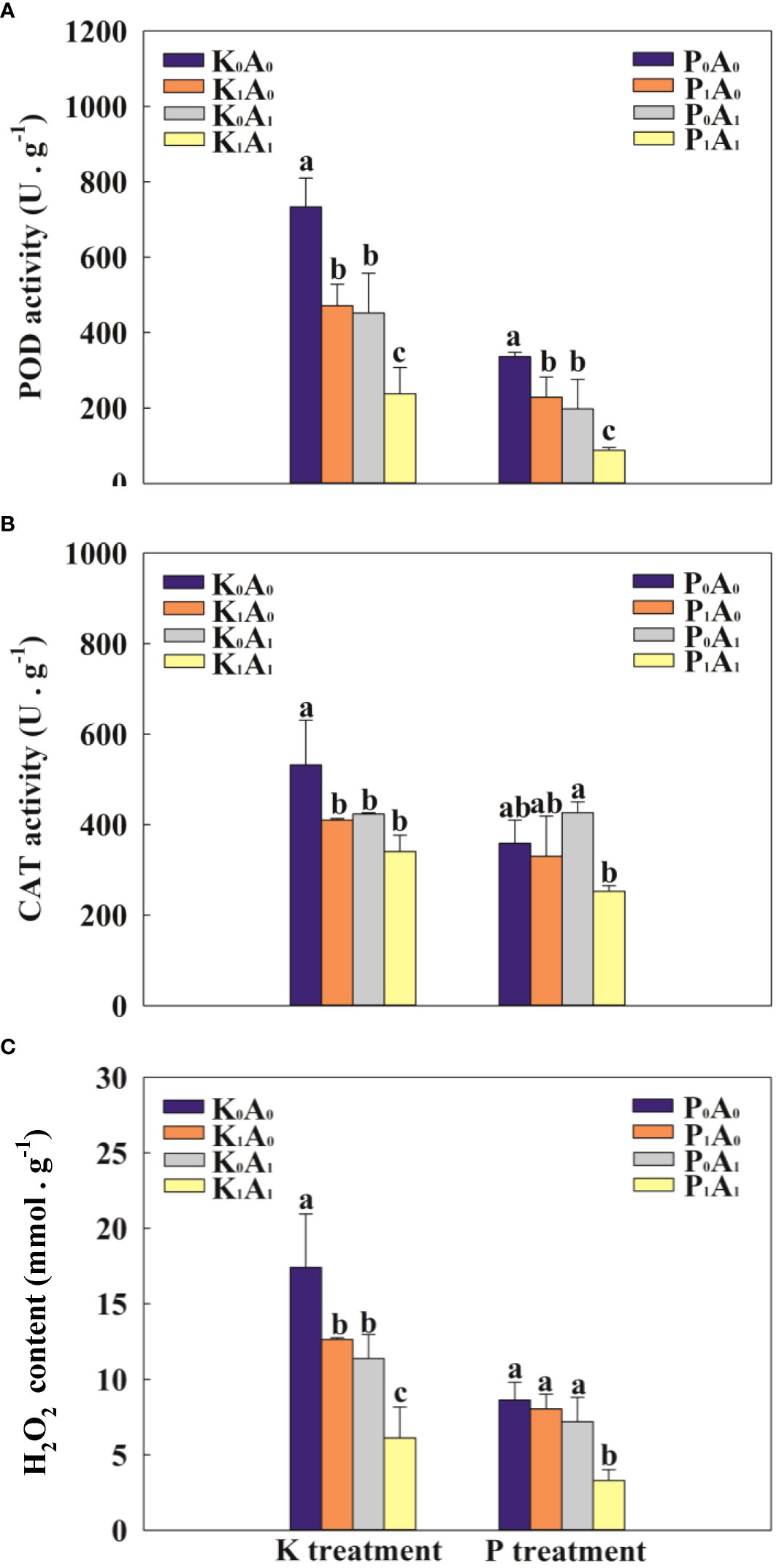

3.5 Antioxidant system

Adverse environments can trigger the excessive accumulation of ROS and aggravate lipid peroxidation in plants. Compared with K0A0, the POD, CAT, and H2O2 of bermudagrass in the K1A0 treatment group were significantly reduced by 55.8%, 30.4%, and 37.8%, while in the K0A1 treatment group, the POD, CAT, and H2O2 activities of bermudagrass were significantly reduced by 62.6%, 25.8%, and 184.2%, respectively (Figure 5). Compared with the K1A0 treatment, the POD activity and H2O2 level were significantly decreased by 49.5% and 51.5%, respectively, in the K1A1 treatment. Simultaneously, under P deficiency stress, the P1A1 treatment significantly decreased the POD activity and H2O2 content (by 61.6% and 59.0%, respectively), compared with the P1A0 treatment. These results indicate that under the P- or K-deficient conditions, A. aculeatus might decrease the activity of the antioxidant enzymes CAT and POD and alleviate membrane lipid peroxidation.

Figure 5 Effects of Aspergillus aculeatus on POD activity (A), CAT activity (B) and H2O2 content (C) of bermudagrass under K or P deficiency stress. K0A0 represents no potassium feldspar and A. aculeatus treatment; K1A0 represents only potassium feldspar treatment; K0A1 represents only A. aculeatus treatment; K1A1 represents potassium feldspar + A. aculeatus treatment; P0A0 represents no tricalcium phosphate and A. aculeatus treatment; P1A0 represents only tricalcium phosphate treatment; P0A1 represents only A. aculeatus treatment; P1A1 represents tricalcium phosphate + A. aculeatus treatment. Columns marked with the same small letter indicate insignificant differences between the four treatment groups (P < 0.05).

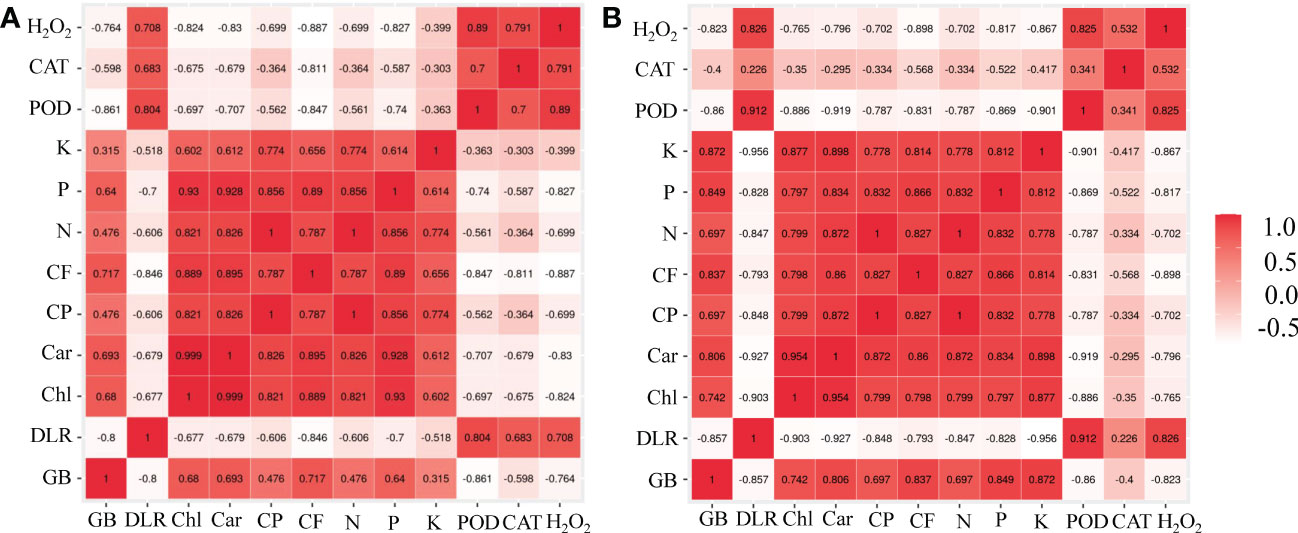

3.6 Correlation analysis

Two correlation plots were depicted for each K or P deficiency stress treatment and are presented in Figures 6A, B, respectively. These correlation plots provide an observation to visually compare the correlation of measured traits. Under K or P deficiency stress, the growth biomass was significantly positively correlated with chlorophyll a+b, carotenoid, and P contents and negatively correlated with the dead leaf rate (Figure 6). There was a significant positive correlation between forage quality (crude protein and crude fat) and chlorophyll a+b, carotenoids, P content, K content, and N content in the leaves of bermudagrass. However, the phenotypic indicators (growth biomass, chlorophyll a+b, carotenoid, crude protein, crude fat, N content, P content, and K content) showed a significant negative correlation with H2O2 content.

Figure 6 Correlation plot designed by the R software for all measured traits in bermudagrass under K deficiency (A) and P deficiency stress (B). In the plots, red, pink, and white represent positive, zero, and negative correlations, respectively, and the darker the color (either red or white), the stronger the correlation. GB, growth biomass; DLR, dead leaf rate; Chl, chlorophyll a+b; Car, carotenoid; CP, crude protein; CF, crude fat; N, N content; P, P content; K, K content; POD, peroxidase; CAT, catalase; H2O2, hydrogen peroxide.

4 Discussion

Nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium play a fundamental role in the growth and development of plants, and they are important mineral nutrients involved in photosynthesis (Wang et al., 2012; Ding et al., 2021). Under the conditions of P or K deficiency, the accumulation of N, P, and K in plants decreases, thereby inhibiting the absorption and utilization of nutrients and impeding the photosynthesis of plants. Photosynthetic pigments are one of the key factors affecting photosynthesis, and their content can directly affect the photosynthesis of plants, particularly chlorophyll and carotenoid contents (Bode et al., 2009). Our results showed that under P or K deficiency stress, the contents of N, P, and K in the leaves increased significantly when A. aculeatus was inoculated. Previous studies have confirmed the P- and K-solubilizing activities of A. aculeatus (Li et al., 2019; Li et al., 2021). In addition, the chemical characteristics of soils with poor fertility have also been measured. We found that the content of available P, K, total N, and total K in the soil was significantly increased after inoculating A. aculeatus into the soil with poor fertility (unpublished data). The beneficial effect of A. aculeatus amendment on bermudagrass under P or K deficiency supports earlier studies. The research reported that co-inoculation of P- and K-solubilizing microorganisms in conjunction with the direct application of insoluble P and K into the soil enhanced N, P, and K uptake of plants grown on P- and K-limited soils (Meena et al., 2016). As we observed, the contents of chlorophyll a+b and carotenoids were distinctly increased in A. aculeatus-inoculated bermudagrass (P1A1 and K1A1 groups) compared with the other groups and were significantly positively correlated with N, P, and K, as well as significantly negatively correlated with the dead leaf rates. The correlation between these functional traits could provide a relatively comprehensive evaluation of plant adaptability to P or K deficiency stress. This is fully aligned with a previous study, which documented that inoculation with a P-solubilizing strain stimulates an increase in chlorophyll (chl a and b) content and nutrient uptake (N, P, and K) in plants (Marathe et al., 2017). Overall, we suggested that A. aculeatus could contribute to better photosynthetic activity (increased chlorophyll a and b content) and growth characteristics when plants are exposed to P or K deficiency stress.

Forage quality is one of the indicators for evaluating the value of forage utilization. A higher feed value was accompanied by a higher crude protein and crude fat content in pasture (Li et al., 2018). Studies have demonstrated that N, P, and K effectively enhanced the content of crude protein and crude fat in plants (Osuagwu and Edeoga, 2013; Ogunyemi et al., 2018). Compared with P- or K-deficient treatments, the contents of crude protein and crude fat were markedly enhanced in the leaves of bermudagrass inoculated with A. aculeatus and were significantly positively correlated with the N and P contents. Nitrogen is an important component of chlorophyll and protein in plants, and a sufficient nitrogen supply can increase the content of chlorophyll and soluble protein (Amy et al., 2006; Fredeen et al., 2010), which is consistent with our results. In addition, P is a component of a series of important biochemical substances, such as nucleic acids, coenzymes, phosphoproteins, and phospholipids, and its deficiency affects nitrogen metabolism. According to Baier and Kristan (1986), the application of P could increase the uptake of N by plants, thereby enhancing the content of crude protein and forage quality (Baier and Kristan, 1986). In the same way, K deficiency could reduce the energy conversion rate and, thus, decrease the crude protein content of herbage, leading to the degradation of forage quality. Combining the above results, we concluded that the inoculation of A. aculeatus enhanced plant forage quality by improving P and K solubilizers. Enhancement of plant forage quality by improving P and K solubilizers is another beneficial effect of microorganisms with P- and K-solubilizing potential characteristics.

In this study, important indicators such as POD, CAT, and H2O2 were assessed to investigate the role of A. aculeatus for P or K deficiency stress tolerance in bermudagrass. When plants are exposed to abiotic stresses, increased cellular damage is associated with the production of ROS (Fadzilla et al., 1997). In our results, we found that inoculated bermudagrass showed remarkably lower H2O2 levels than uninoculated bermudagrass under P- or K-deficient conditions, indicating that A. aculeatus could significantly attenuate stress-induced oxidative damage. Although plants cannot escape from deleterious environments, they have already developed and established a mathematical regulatory mechanism to cope with stress damage (Abeed et al., 2022). Usually, stress-induced ROS accumulation is scavenged by diverse enzymatic scavengers, such as POD, CAT, SOD, or other antioxidants (Apel and Hirt, 2004). H2O2 is an important ROS produced in the catalytic process of SOD, resulting in oxidative damage (Mittler, 2002). CAT and POD are the major antioxidant enzymes in plants, and CAT could degrade H2O2 into water and oxygen to scavenge H2O2. Our results indicated that inoculation with A. aculeatus significantly decreased the CAT and POD activities and the concentration of H2O2 in the P1A1 and K1A1 groups compared with the P1A0 and K1A0 groups. These studies reveal that A. aculeatus can alleviate the antioxidant damage caused by low phosphorus or potassium stress by decreasing ROS accumulation and altering the activity of antioxidant enzymes.

Therefore, our results demonstrated the regulatory mechanism of A. aculeatus on K or P deficiency stresses in bermudagrass. First, A. aculeatus increases the contents of N, P, and K in the leaves of bermudagrass and enhances the accumulation of chlorophyll and carotenoids, thereby promoting plant photosynthesis. Second, A. aculeatus increases the content of crude protein and crude fat accompanied by the growing N and P contents in the leaves of bermudagrass. Finally, A. aculeatus could mitigate membrane lipid peroxidation and decrease the activities of the antioxidant enzymes CAT and POD. Therefore, A. aculeatus has great promotion value and economic benefit in K- or P-deficient soil as a microbial agent.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

XL conceived the experiments and wrote the manuscript. TZ performed the experiments. XL and XX analyzed the data. YX and XC cultivated the experimental materials. JF guided this experiment. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (grant no. ZR2020QC051).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

APX, ascorbate peroxidase; CAT, catalase; DLB, dead leaf biomass; DLR, dead leaf rate; GB, growth biomass; GPX, glutathione peroxidase; H2O2, hydrogen peroxide; K, potassium; K0A0, no K-feldspar and A. aculeatus treatment; K0A1, only A. aculeatus; K1A0, only K-feldspar; K1A1, K-feldspar and A. aculeatus treatment; LB, leaf biomass; P, phosphorus; P0A0, no tricalcium phosphate and A. aculeatus treatment; P0A1, only A. aculeatus; P1A0, only tricalcium phosphate; P1A1, tricalcium phosphate and A. aculeatus treatment; POD, peroxidase; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SOD, superoxide dismutase.

References

Abeed, A. H. A., Mahdy, R. E., Alshehri, D., Hammami, I., Eissa, M. A., Latef, A. A. H., et al. (2022). Induction of resilience strategies against biochemical deteriorations prompted by severe cadmium stress in sunflower plant when Trichoderma and bacterial inoculation were used as biofertilizers. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 1004173. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.1004173

Amy, K., Veronica, C., Neal, B., Lena, H., Tala, A. (2006). Ecophysiological responses of Schizachyrium scoparium to water and nitrogen manipulations. Great Plains Res. 16, 29–36.

Apel, K., Hirt, H. (2004). Reactive oxygen species: metabolism, oxidative stress, and signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 55, 373–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141701

Baier, J., Kristan, V. (1986). Effect of phosphorus fertilizer application on increasing nutrient uptake. Agrochemica. 26, 343–345.

Bargaz, A., Lyamlouli, K., Chtouki, M., Zeroual, Y., Dhiba, D. (2018). Soil microbial resources for improving fertilizers efficiency in an integrated plant nutrient management system. Front. Microbiol. 9, 1606. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01606

Bode, S., Quentmeier, C. C., Liao, P. N., Mafi, N., Barros, T., Wilk, L., et al. (2009). On the regulation of photosynthesis by excitonic interactions between carotenoids and chlorophylls. P. Natl. A. Sci. 106 (30), 12311–12316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903536106

Cakmak, I. (2005). The role of potassium in alleviating detrimental effects of abiotic stresses in plants. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 168, 521–530. doi: 10.1002/jpln.200420485

Clarkson, D. T., Hanson, J. B. (1980). The mineral nutrition of higher plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. 31, 239–298. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pp.31.060180.001323

Ding, Z., Ali, E. F., Almaroai, Y. A., Mamdouh, A. E., Amany, H. A. A. (2021). Effect of potassium solubilizing bacteria and humic acid on faba bean (Vicia faba l.) plants grown on sandy loam soils. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 21, 791–800. doi: 10.1007/s42729-020-00401-z

Fadzilla, N. A. M., Finch, R. P., Burdon, R. H. (1997). Salinity, oxidative stress and antioxidant responses in shoot cultures of rice. J. Exp. Bot. 48, 325–331. doi: 10.1093/jxb/48.2.325

Fan, J., Ren, J., Zhu, W., Amombo, E., Fu, J., Chen, L. (2014). Antioxidant responses and gene expression in s under cold stress. J. Am. Soc Hortic. Sci. 139, 699–705. doi: 10.21273/JASHS.139.6.699

Fredeen, A. L., Gamon, J. A., Field, C. B. (2010). Responses of photosynthesis and carbohydrate-partitioning to limitations in nitrogen and water availability in field-grown sunflower. Plant Cell Environ. 14 (9), 963–970.

Garcia, K., Chasman, D., Roy, S., Ané, J. M. (2017). Physiological responses and gene co-expression network of mycorrhizal roots under k(+) deprivation. Plant Physiol. 173 (3), 1811–1823. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.01959

Gundala, P. B., Chinthala, P., Sreenivasulu, B. (2013). A new facultative alkaliphilic, potassium solubilizing, bacillus spp. SVUNM9 isolated from mica cores of nellore district, andhra pradesh, India. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2 (1), 1–7.

Guo, Y. P., Chen, P. Z., Zhang, L. C., Zhang, S. L. (2002). Effects of different phosphorus nutrition levels on photosynthesis in satsuma mandarin (Citrus unshiu marc.) leaves. Plant Nutr. Fertil. Sci. 8, 186–191.

Hu, T., Li, H. Y., Zhang, X. Z., Luo, H. J., Fu, J. M. (2011). Toxic effect of NaCl on ion metabolism, antioxidative enzymes and gene expression of perennial ryegrass. Ecotox. Environ. Safe. 74, 2050–2056. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2011.07.013

Illmer, P. A., Schinner, F. (1995). Solubilization of inorganic calcium phosphates solubilization mechanisms. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 27, 257–263. doi: 10.1016/0038-0717(94)00190-C

Krishnaraj, P. U., Dahale, S. (2014). Mineral phosphate solubilization: concepts and prospects in sustainable agriculture. Proc. Ind. Natl. Sci. Acad. 80, 389–405. doi: 10.16943/ptinsa/2014/v80i2/55116

Kumar, S., Diksha, Sindhu, S. S., Kumar, R. (2021). Biofertilizers: An ecofriendly technology for nutrient recycling and environmental sustainability. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 3, 100094. 10.1016/j.crmicr.2021.100094

Li, C., Peng, F., Xue, X., You, Q., Lai, C., Zhang, W., et al. (2018). Productivity and quality of alpine grassland vary with soil water availability under experimental warming. Front. Plant Sci. 9, 1790. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01790

Li, X., Sun, X., Wang, G., Amombo, E., Zhou, X., Du, Z., et al. (2019). Inoculation with Aspergillus aculeatus alters the performance of perennial ryegrass under phosphorus deficiency. J. Am. Soc Hortic. Sci. 144, 182–192. doi: 10.21273/JASHS04581-18

Li, X., Yin, Y., Fan, S., Xu, X., Amombo, E., Xie, Y., et al. (2021). Aspergillus aculeatus enhances potassium uptake and photosynthetic characteristics in perennial ryegrass by increasing potassium availability. J. Appl. Microbiol. 00, 1–12.

Luiz, J., Young, M., Kanashiro, S., Jocys, T., Reis, A. (2018). Scientia horticulturae silver vase bromeliad: Plant growth and mineral nutrition under macronutrients omission. Scientia Hortic. 234, 318–322. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2018.02.002

Marathe, R., Phatake, Y., Shaikh, A., Shinde, B., Gajbhiye, M. (2017). Effect of IAA produced by pseudomonas aeruginosa 6a (bc4) on seed germination and plant growth of glycin max. J. Exp. Biol. Agric. Sci. 5, 351–358. doi: 10.18006/2017.5(3).351.358

Meena, V. S., Maurya, B. R., Verma, J. P., Meena, R. S. (2016). Potassium solubilizing microorganisms for sustainable agriculture (New Delhi: Springer).

Mittler, R. (2002). Oxidative stress, antioxidants and stress tolerance. Trends. Plant Sci. 7, 405–410. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(02)02312-9

Mittova, V., Tal, M., Volokita, M., Guy, M. (2002). Salt stress induces up-regulation of an efficient chloroplast antioxidant system in the salt-tolerant wild tomato species lycopersicon pennellii but not in the cultivated species. Physiol. Plant 115 (3), 393–400. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3054.2002.1150309.x

Ogunyemi, A. M., Otegbayo, B. O., Fagbenro, J. A. (2018). Effects of NPK and biochar fertilized soil on the proximate composition and mineral evaluation of maize flour. Food Sci. Nutr. 6 (8), 2308–2313. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.808

Osuagwu, G. G. E., Edeoga, H. O. (2013). Influence of npk inorganic fertilizer treatment on the proximate composition of the leaves of Ocimum gratissimum (L.) and gongronema latifolium (Benth). Pakistan J. Biol. Sci. 16, 372–378. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2013.372.378

Poirier, Y., Bucher, M. (2002). Phosphate transport and homeostasis in arabidopsis. Arabidopsis Book 1, e0024. doi: 10.1199/tab.0024

Prajapati, K., Modi, H. (2012). Isolation and characterization of potassium solubilizing bacteria from ceramic industry soil. CIB Technol. J. Microbiol. 1 (2-3), 8–14.

Sharma, S. B., Sayyed, R. Z., Trivedi, M. H., Gobi, T. A. (2013). Phosphate solubilizing microbes: sustainable approach for managing phosphorus deficiency in agricultural soils. SpringerPlus. 2, 587. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-2-587

Shi, H., Ye, T., Zhong, B., Liu, X., Chan, Z. (2014). Comparative proteomic and metabolomic analyses reveal mechanisms of improved cold stress tolerance in bermudagrass (Cynodon dactylon (L.) pers.) by exogenous calcium. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 56, 1064–1079. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12167

Shin, R., Berg, R., Schachtman, D. (2005). Reactive oxygen species and root hairs in arabidopsis root response to nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium deficiency. Plant Cell Physiol. 46, 1350–1357. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pci145

Wang, Y., Chen, Y. F., Wu, W. H. (2021). Potassium and phosphorus transport and signaling in plants. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 63 (1), 34–52. doi: 10.1111/jipb.13053

Wang, N., Hua, H., Eneji, A. E., Li, Z., Duan, L., Tian, X. (2012). Genotypic variations in photosynthetic and physiological adjustment to potassium deficiency in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum). J. Photochem. Photobiol. 110, 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2012.02.002

Wellburn, A. R. (1994). The spectral determination of chlorophylls a and b, as well as total carotenoids, using various solvents with spectrophotometers of different resolution. J. Plant Physiol. 144, 307–313. doi: 10.1016/S0176-1617(11)81192-2

Xie, Y., Han, S., Li, X., Amombo, E., Fu, J. M. (2017). Amelioration of salt stress on bermudagrass by the fungus Aspergillus aculeatus. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 30, 245–254. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-12-16-0263-R

Xie, Y., Luo, H., Du, Z., Hu, L., Fu, J. M. (2014). Identification of cadmium-resistant fungi related to cd transportation in bermudagrass [Cynodon dactylon (L.) pers.]. Chemosphere. 117, 786–792. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.10.037

Zarjani, J. K., Aliasgharzad, N., Oustan, S., Emadi, M., Ahmadi, A. (2013). Isolation and characterization of potassiumsolubilizing bacteria in some Iranian soils. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 59, 1713–1723. doi: 10.1080/03650340.2012.756977

Zhang, Y. K., Yin, Y. L., Amombo, E., Li, X., Fu, J. M. (2020). Different mowing frequencies affect nutritive value and recovery potential of forage bermudagrass. Crop Pasture Sci. 71, 610–619. doi: 10.1071/CP19369

Keywords: Aspergillus aculeatus, bermudagrass, potassium, phosphorus, P or K deficiency stress

Citation: Li X, Zhang T, Xue Y, Xu X, Cui X and Fu J (2023) Aspergillus aculeatus enhances nutrient uptake and forage quality in bermudagrass by increasing phosphorus and potassium availability. Front. Plant Sci. 14:1165567. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2023.1165567

Received: 14 February 2023; Accepted: 31 March 2023;

Published: 25 April 2023.

Edited by:

Jin-Lin Zhang, Lanzhou University, ChinaReviewed by:

Amany H. A. Abeed, Assiut University, EgyptLei Wang, Xinjiang Institute of Ecology and Geography (CAS), China

Yan Xie, Wuhan Botanical Garden (CAS), China

Copyright © 2023 Li, Zhang, Xue, Xu, Cui and Fu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jinmin Fu, dHVyZmNuQHFxLmNvbQ==

Xiaoning Li

Xiaoning Li Ting Zhang

Ting Zhang Jinmin Fu

Jinmin Fu