95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Plant Sci. , 03 April 2023

Sec. Plant Bioinformatics

Volume 14 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2023.1161539

This article is part of the Research Topic Multi-omics and Computational Biology in Horticultural Plants: From Genotype to Phenotype, Volume II View all 25 articles

Yuqing Zhu1,2,3,4

Yuqing Zhu1,2,3,4 Wei Kuang1,2,3,4

Wei Kuang1,2,3,4 Jun Leng1,2,3,4

Jun Leng1,2,3,4 Xue Wang1,2,3,4

Xue Wang1,2,3,4 Linlin Qiu1,2,3,4

Linlin Qiu1,2,3,4 Xiangyue Kong1,2,3,4

Xiangyue Kong1,2,3,4 Yongzhang Wang1,2,3,4*

Yongzhang Wang1,2,3,4* Qiang Zhao1,2,3,4*

Qiang Zhao1,2,3,4*The 14-3-3 (GRF, general regulatory factor) regulatory proteins are highly conserved and are widely distributed throughout the eukaryotes. They are involved in the growth and development of organisms via target protein interactions. Although many plant 14-3-3 proteins were identified in response to stresses, little is known about their involvement in salt tolerance in apples. In our study, nineteen apple 14-3-3 proteins were cloned and identified. The transcript levels of Md14-3-3 genes were either up or down-regulated in response to salinity treatments. Specifically, the transcript level of MdGRF6 (a member of the Md14-3-3 genes family) decreased due to salt stress treatment. The phenotypes of transgenic tobacco lines and wild-type (WT) did not affect plant growth under normal conditions. However, the germination rate and salt tolerance of transgenic tobacco was lower compared to the WT. Transgenic tobacco demonstrated decreased salt tolerance. The transgenic apple calli overexpressing MdGRF6 exhibited greater sensitivity to salt stress compared to the WT plants, whereas the MdGRF6-RNAi transgenic apple calli improved salt stress tolerance. Moreover, the salt stress-related genes (MdSOS2, MdSOS3, MdNHX1, MdATK2/3, MdCBL-1, MdMYB46, MdWRKY30, and MdHB-7) were more strongly down-regulated in MdGRF6-OE transgenic apple calli lines than in the WT when subjected to salt stress treatment. Taken together, these results provide new insights into the roles of 14-3-3 protein MdGRF6 in modulating salt responses in plants.

Plants are often affected by environmental stresses such as high salinity, drought, and extreme temperatures, which can adversely inhibit their growth and development (Golldack et al., 2014). High salinity is a severe abiotic stressor that inhibits plant development and productivity (Yoshida et al., 2014). Many genes are involved in salt stress tolerance, including antioxidant protective enzymes, signal transduction, and transcription factors (TFs) (Pardo et al., 1998; Mao et al., 2017; Jiroutova et al., 2021). Among these, 14-3-3 proteins primarily act as molecular chaperones and are extensively involved in abiotic and biotic stress responses via regulation of the conformation, activity, stability, and subcellular localization of target proteins (Campo et al., 2012).

The 14-3-3 proteins are a family of highly conserved proteins found in all eukaryotes, and can be classified into two categories: the non-ϵ (non-epsilon) and ϵ (epsilon) types (Brennan et al., 2013; Cao et al., 2016). The target proteins of the 14-3-3 family are phosphorylated at certain sites, causing a conformational shift that allows the family to exist as homo or heterodimers (Yasuda et al., 2014). In plants, protein interactions allow the 14-3-3 protein to attach to the plasma membrane H+-ATP (Jahn et al., 1997). This interaction, which mediates the ATP-driven transport of H+ across membranes, is involved in the active transport to manage both the osmotic and ionic stresses under high-salinity conditions (Wang et al., 2021). The 14-3-3 protein characteristics allow for the control of a variety of environmental signaling pathways, including those related to drought, excessive salinity, and extreme temperatures (Li et al., 2013; He et al., 2015; Tian et al., 2015).

In recent years, a growing number of studies have investigated the molecular functions of the 14-3-3 proteins in plants. To date, 13, 8, 12, 18, 5, 6, and 11 14-3-3 proteins have been identified in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), rice (Oryza sativa), tomato (Solanum lycopersicum), soybean (Glycine max), barley (Hordeum vulgare), cotton (Gossypium hirsutum), and grape (Vitis vinifera L.), respectively (Xu and Shi, 2006; Schoonheim et al., 2007; Yao et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2010; Li and Dhaubhadel, 2011). In tobacco, 14-3-3 proteins interact with RSG and CDPK1 to form a heterodimeric trimer, which is used to control the gibberellin pathway (Ito et al., 2014). In tobacco, A 14-3-3 protein is involved in biological stress response via the interaction with the plasma membrane oxidase (NtrbohD16) to regulate ROS production in plants (Elmayan et al., 2007). In response to heat, cold, and salt stresses, rice exhibits significant variations in OsGRF expression (Yao et al., 2007). The 14-3-3λ and 14-3-3κ proteins in Arabidopsis participate in response to salt stress by regulating SOS2 activity in the SOS (salt overly sensitive) pathway (Zhou et al., 2014). 14-3-3 proteins are involved in the browning pathway of potato tubers by regulating the antioxidant enzyme activity (Łukaszewicz et al., 2002). Additionally, 14-3-3 proteins demonstrate considerable up- or down-regulation in Vitis vinifera L. under cold and heat stresses, suggesting their possible function in the regulation of abiotic stress response (Cheng et al., 2018).

Plants cope with salt stress through complex physiological responses and molecular regulatory mechanisms. However, the precise role of apple 14-3-3 proteins in regulating salt stress remains largely unclear. Therefore, it is very valuable to clarify the function of 14-3-3 protein under salt stress. To identify the function of Md14-3-3s, a total of nineteen 14-3-3 genes in apples were analyzed in this study. Functional characterization demonstrated that MdGRF6 negatively regulates salt tolerance. Therefore, this study provides the basis for future research examining the molecular processes of MdGRF6 in controlling the salt stress response in apples.

The apple (Malus×domestica) seedlings were cultured in MS medium with 1 mg/L 6-BA, 0.1 mg/L NAA, and 0.1 mg/L GA3 at 23 ± 1°C and 16 h light/8 h dark photoperiod. The apple calli were cultured for 20 days in the dark at room temperature (24°C) on MS medium with 3 mg/L 2, 4-D, and 0.4 mg/L 6-BA. Tobacco seeds were surface-sterilized with 2% sodium hypochlorite (NaClO) for 10 min followed by 75% ethanol wash for 1 min. Then the seeds were washed with sterile water five times and cultured on MS medium with 0.8% agar and 2.5% sucrose at 23°C under 16 h light/8 h dark photoperiod.

For tissue expression analysis, the samples (roots, stems, leaves, fruits, and seeds) were collected from ten five-year-old apple trees grown in the experimental field of the horticulture orchard of the Qingdao Agricultural University (Shandong Province, China) in October 2022. For gene expression, the apple seedlings were treated with 100 mmol/L NaCl and harvested at 0, 1, 3, 6, and 12 h after treatment. Following the collection of each sample, the seedlings were immediately flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C until future use.

Total RNA was extracted using the RNA Plant Plus Reagent (Tiangen, Beijing, China) and the first-strand cDNA was synthesized using the PrimeScript First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Takara, Dalian, China). The ChamQ SYBR Mixture (Vazyme) was used for RT-qPCR reactions using a LightCycler 480 II RT-qPCR system. The cycle threshold (Ct) 2−ΔΔCT approach was used to analyze relative gene expression (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). MdACTIN (apple) and NtACTIN (tobacco) were used as internal controls. Each RT-qPCR sample was done at least in triplicate. The primers are listed in Supplemental Table S2.

Sequences of the 14-3-3 protein from apple, rice, and Arabidopsis were aligned using ClustalW in MAGEX. Neighbor-joining was used to construct the molecular phylogenetic trees with 1,000 reiterations. iTOL (https://itol.embl.de/itol.cgi) was used to annotate the 14-3-3 protein sequence information. TBtools was used to identify the chromosomal locations of Md14-3-3 genes, using the apple genome annotation file (gene_models_20170612.gff3.gz) (Chen et al., 2020). Plant-CARE (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/) was then used to analyze the cis-elements in the promoters of Md14-3-3 genes (2,000-bp fragment at the upstream of the start codon) (Wang et al., 2014). Protein sequences of the Md14-3-3 genes family were submitted to MEME (https://meme-suite.org/meme/doc/meme.html) for conserved motif analysis (Tripathi et al., 2016).

The full-length of MdGRF6 was cloned into the overexpression vector pRI101-EGFP to obtain the 35S::MdGRF6-EGFP recombinant plasmids. The MdGRF6-RNAi were constructed using the RNAi vector. To generate the PMdGRF6::GUS reporter construct, ~2 kb MdGRF6 promoter fragments were cloned from apple genomic DNA and inserted into the pCAMBIA1391::GUS vector containing the GUS reporter gene. The primers in this study are listed in Supplemental Table S2.

The recombinant vectors 35S::MdGRF6-EGFP, MdGRF6-RNAi, and 35S::EGFP were introduced into Agrobacterium rhizogenes strain EHA105. The transgenic apple calli or tobacco plants were generated by Agrobacturium-mediated transformation method as described previously (Gallois and Marinho, 1995; An et al., 2017). The calli were subcultured on the MS medium containing 30 mg/L kanamycin, and the rooted transgenic tobacco plants were planted into the soil.

For subcellular localization, the 35S::MdGRF6-EGFP or 35S::EGFP vector was transformed into an Agrobacterium EHA105 strain and used for transient expression in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves. The fluorescence was then observed after 2-3 days using a laser confocal microscope.

The 30-day PMdGRF6::GUS transgenic tobacco was used for tissue expression analysis. Young leaf, stem, and root tissues were visualized using the GUS Staining Kit (Solarbio, Beijing, China).

The WT and transgenic apple calli were treated with 100 mM NaCl or 150 mM NaCl for 15 days. Following treatment, the apple calli were collected and the fresh weight was measured. Relative conductivity was determined according to Yang et al. method (Yang et al., 2022), using a DDSJ-318 conductometer (Yidian Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). The thiobarbituric acid-based method was used to determine the malondialdehyde (MDA) content and the absorbance value of the reaction solution was determined using a spectrophotometer at 600, 532, and 450nm (Yoke Istrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China).

WT and transgenic tobacco seeds were sterilized and sown onto MS, MS + 50 mmol/L NaCl, or MS + 100 mmol/L NaCl plates to detect the germination rates. Following seed germination, consistently growing transgenic and WT tobacco were transferred to MS medium with 50 mM NaCl or 100 mM NaCl for 10 days. After salt treatment, the fresh weight, root length, chlorophyll, and MDA content were measured. As previously described, the MDA content was measured using the thiobarbituric acid method. Chlorophyll was extracted with 95% ethanol, and the supernatant was used to determine the absorbance values at 665 and 649 nm (Yoke Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China).

Uniformly-developed seedlings of transgenic and WT tobacco plants were treated with 350 mM NaCl for four weeks. Water was used as the control. After four weeks, the chlorophyll content and relative conductivity were determined as above described. Diaminobenzidine (DAB) and p-nitroblue tetrazolium chloride (NBT) histochemical staining were used to determine H2O2 and contents in tobacco leaves, respectively. The activities of enzymes SOD and POD were measured using the SOD and POD assay kits (Solarbio, Beijing, China), respectively. The above experiments were replicated three times.

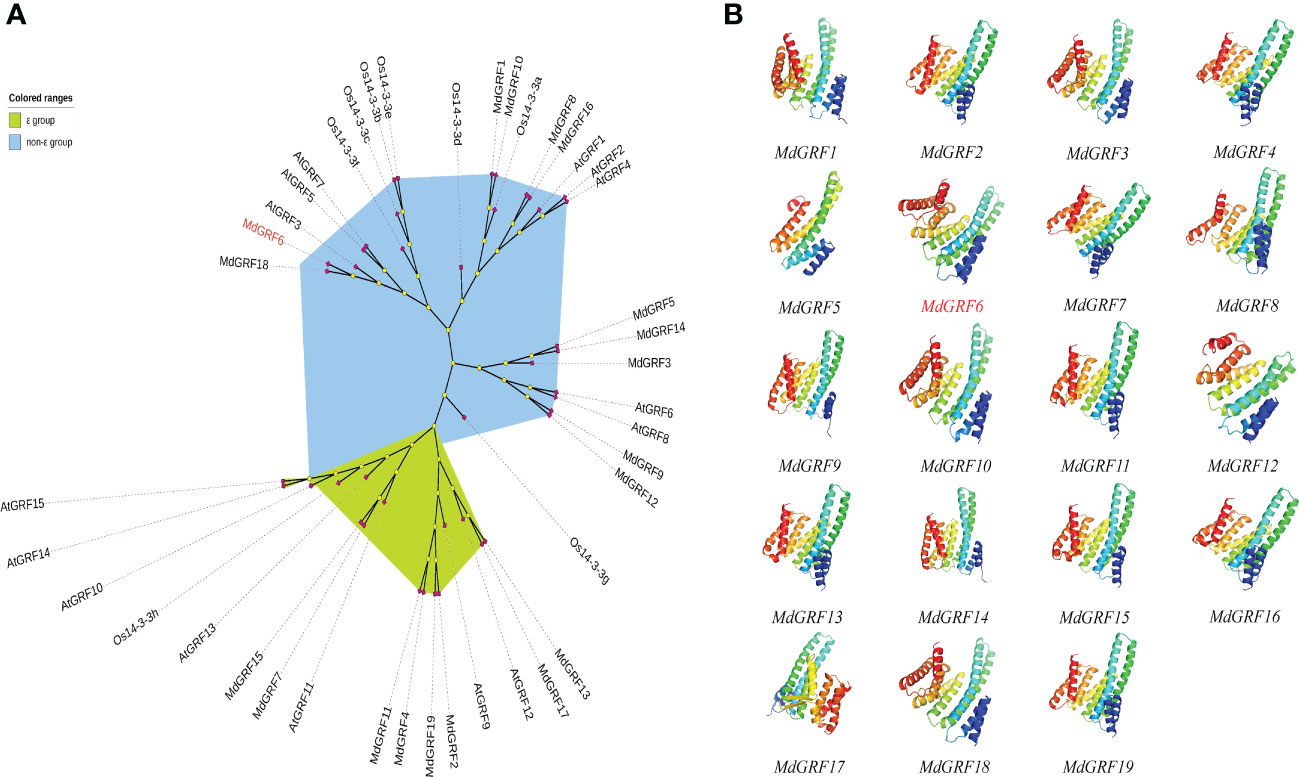

To identify the 14-3-3 genes in the apple genome, the BLASTp and the Pfam tool were used. A total of twenty 14-3-3 genes were identified in the apple genome based on their homology to the 14-3-3 protein sequences in Arabidopsis from the TAIR database (http://www.arabidopsis.org). However, only nineteen genes were cloned and labeled as MdGRF1-MdGRF19 based on their chromosomal location (Table S1). The phylogenetic tree demonstrated that the Md14-3-3 proteins were divided into two groups (ϵ and non-ϵ group) (Figure 1A). Following the protein 3D models, the 14-3-3 secondary structures were classified into three divisions. The middle position domain structure was similar, while the differences were the N-terminal and C-terminal structures (Figure 1B).

Figure 1 Phylogenetic tree and protein structures of Md14-3-3s. (A) The NJ phylogenetic tree (1,000 bootstrap replicates) was generated with 14-3-3 proteins from apples, rice, and Arabidopsis. (B) Phyre2 in ‘Normal’ mode and Pymol were used to generate all 3D models of MdGRFs. Images were colored by rainbow N → C terminus. All models were based on template d1o9da or c3e6yB.

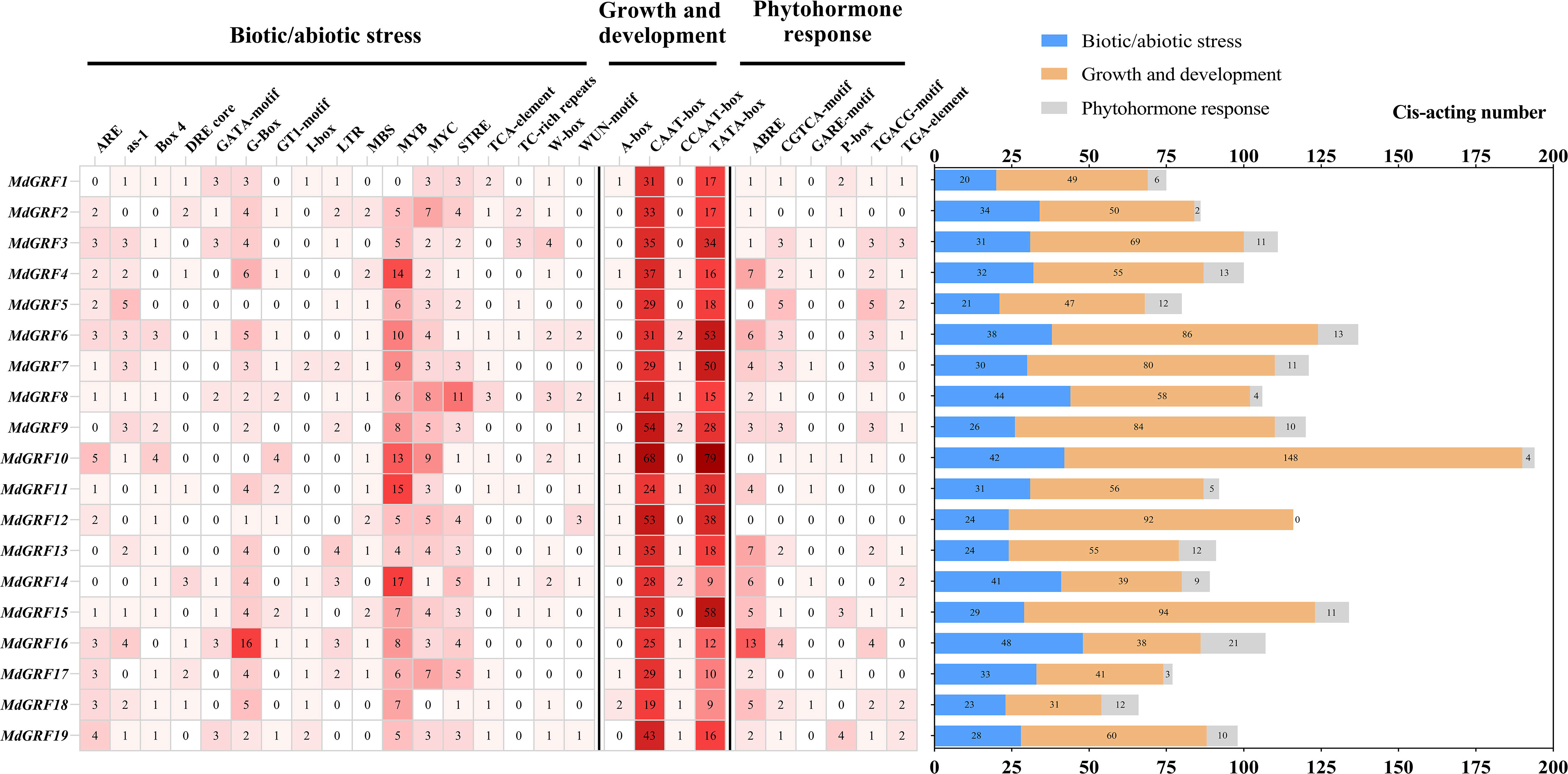

The cis-acting elements in the promoter regions of Md14-3-3 genes were examined using the PlantCARE database (Figure 2). Based on their functions, the cis-acting elements were divided into three groups: biotic/abiotic stress, growth and development, and phytohormone response. The cis-acting elements of plant biotic/abiotic stress, including salicylic acid (TCA-element: CCATCTTTTT), defense and stress (TC-rich repeats: GTTTTCTTAC), low temperature (LTR: CCGAAA), MYB-binding site involving in drought-inducibility (MBS: CAACTG), were identified in the promoters of the Md14-3-3 genes. A large number of core cis-acting elements (such as TATA box, CAAT box, and others) were also identified in the Md14-3-3s promoter regions. In addition, multiple elements responding to phytohormones were identified. The promoters of Md14-3-3s also contained cis-acting elements responding to TGA-element (AACGAC), ABRE (ACGTG), GARE (TCTGTTG), and CGTCA that involved in auxin (IAA), abscisic acid (ABA), gibberellin (GA), and methyl jasmonate (MeJA) response.

Figure 2 Promoter analysis of Md14-3-3s. The amount of various cis-acting elements are presented in the grid by the different numbers and color tones. The sum of the cis-acting elements in the three classes of each gene is displayed in the histogram.

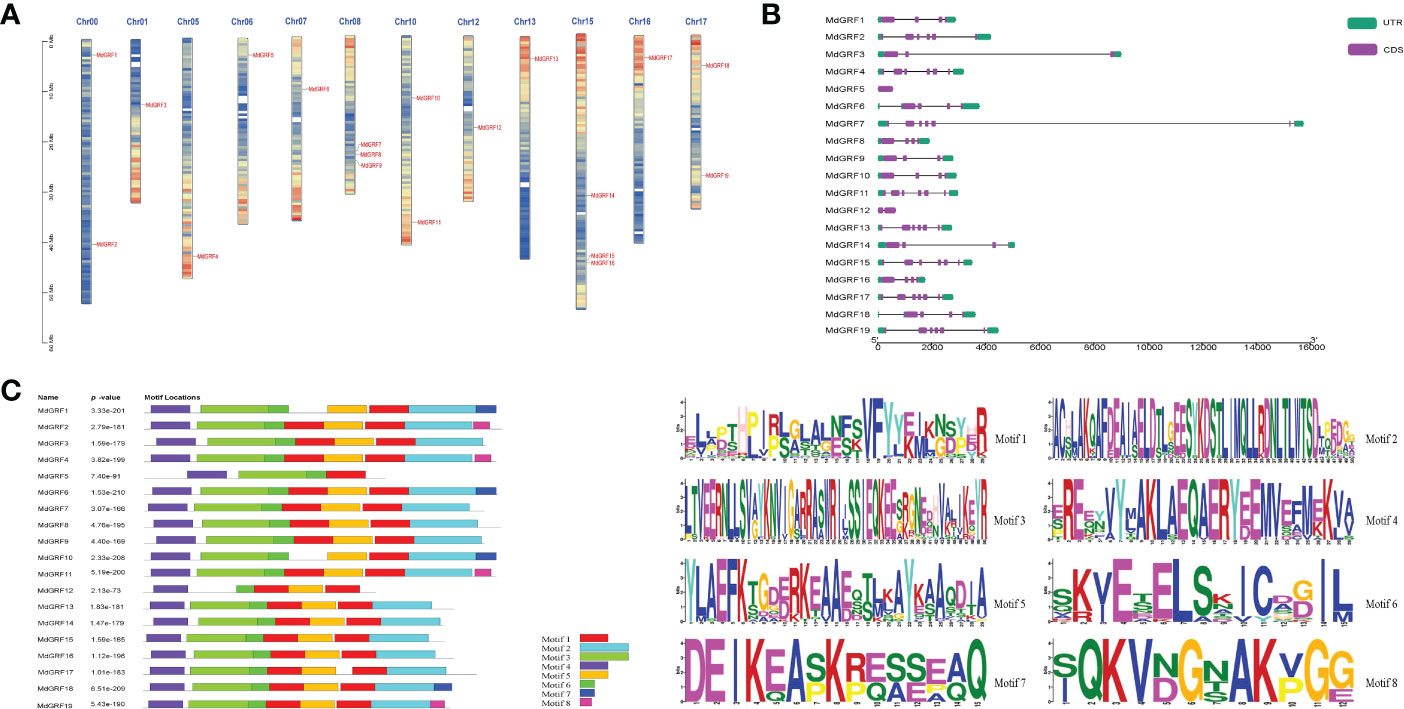

The Md14-3-3 genes were identified on twelve apple chromosomes (Chr): Chr00, 01, 05, 06, 07, 08, 10, 12, 13, 15, 16, and 17 (Figure 3A). The intron/exon analysis showed that the Md14-3-3 genes contained from 0 to 6 introns (Figure 3B). Among these, MdGRF4, 7, 11, 13, 15, 17, and 19 contained the most introns (6 introns), while MdGRF5 had none. Additionally, the phylogenetic tree demonstrated that MdGRF6 and 18, which were both situated on the same branch, had similar intron/exon distribution (Figure 3B). Eight motifs in the Md14-3-3 proteins were predicted using the Multiple Em for Motif Elicitation (MEME) program. Most of the conserved motifs were similar in distribution (Figure 3C). However, these conserved motif differences may be responsible for different gene functions.

Figure 3 Characterization and chromosomal localization of the Md14-3-3 genes. (A) Chromosomal localization of 14-3-3 genes in apple. (B) Structural analysis of the Md14-3-3 genes. Different blocks represent UTRs (green), CDs (purple), and introns (black lines). (C) The motif details of the identified conserved domains of the Md14-3-3 proteins. Each motif is represented by a different colored box.

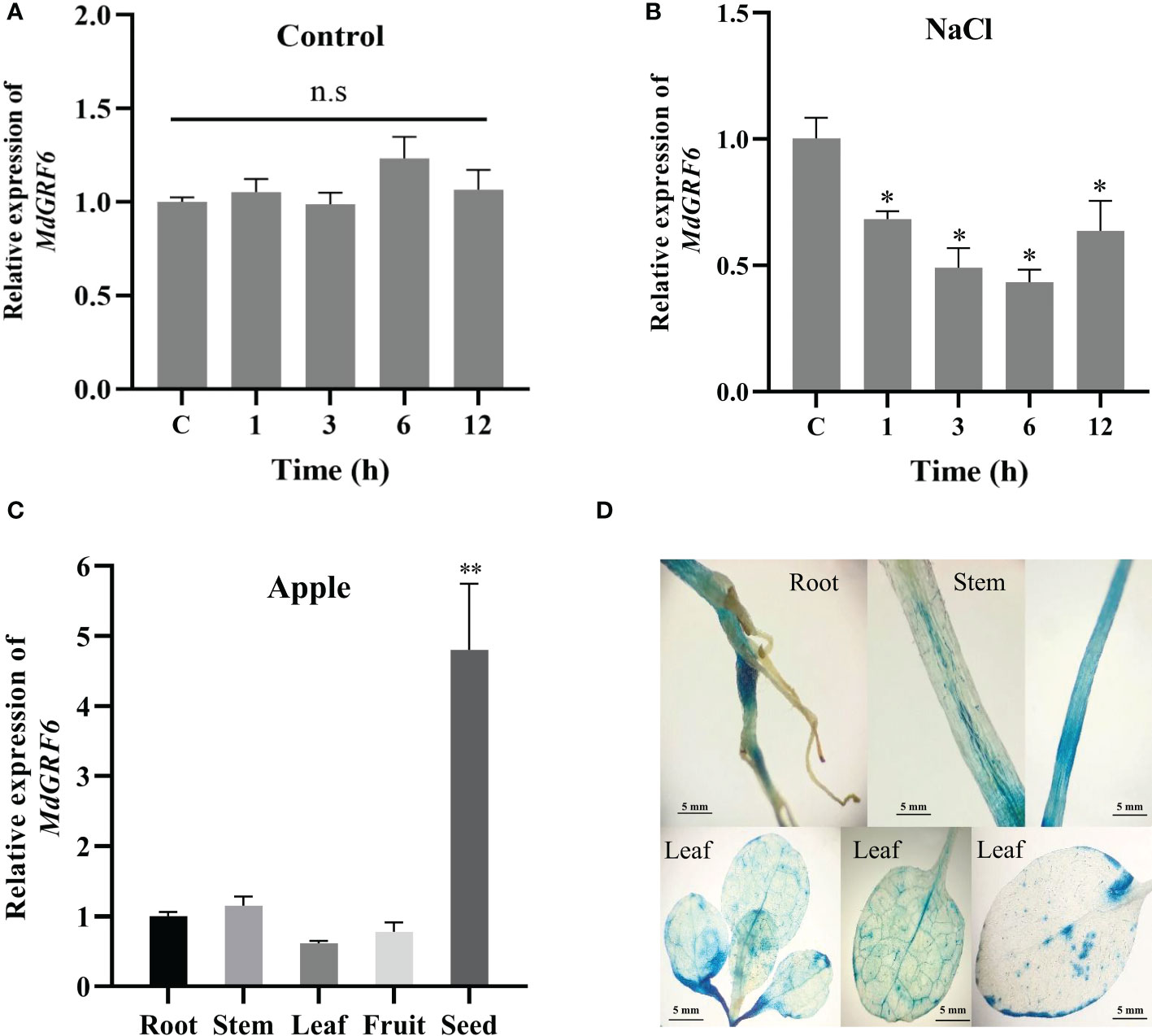

Previous studies have shown that 14-3-3 genes play an important role in plant response to salt stress (Zhou et al., 2014). Here, the transcript levels of the MdGRFs family members were up or down-regulated in response to salinity treatments (Figure S1). One of the members, MdGRF6 was chosen for further analysis. MdGRF6 was down-regulated under salt treatment, with a 0.42-fold down-regulation at the sixth hour. However, there was no significant change in the control group (Figures 4A, B). Next, gene expression in apple roots, stems, leaves, fruits, and seeds were analyzed. The results demonstrated that MdGRF6 was highly expressed in seeds, with the lowest expression in leaves (Figure 4C). To confirm MdGRF6 these results, the PMdGRF6::GUS transgenic tobacco plants were then developed. GUS signals were detected in the roots, stems, and leaves of the transgenic tobacco seedlings (Figure 4D).

Figure 4 Expression patterns of Md14-3-3 genes. (A, B) RT-qPCR analysis of MdGRF6 expression in apple seedlings treated without or with 100 mM NaCl for the indicated time. (C) Expression analysis of MdGRF6 in different apple tissues. (D) PMdGRF6::GUS expression pattern in transgenic tobacco in different tissues. Data are presented as means ± SD (n = 3). Asterisks indicate significant differences LSD test, **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; ns, no significant difference.

In addition, the constructed expression vectors 35S::MdGRF6-EGFP or 35S::EGFP were injected into Nicotiana benthamiana leaves to examine the subcellular localization of MdGRF6. As a result, we found that MdGRF6 was localized in the cytoplasm and cell membrane (Figure S2).

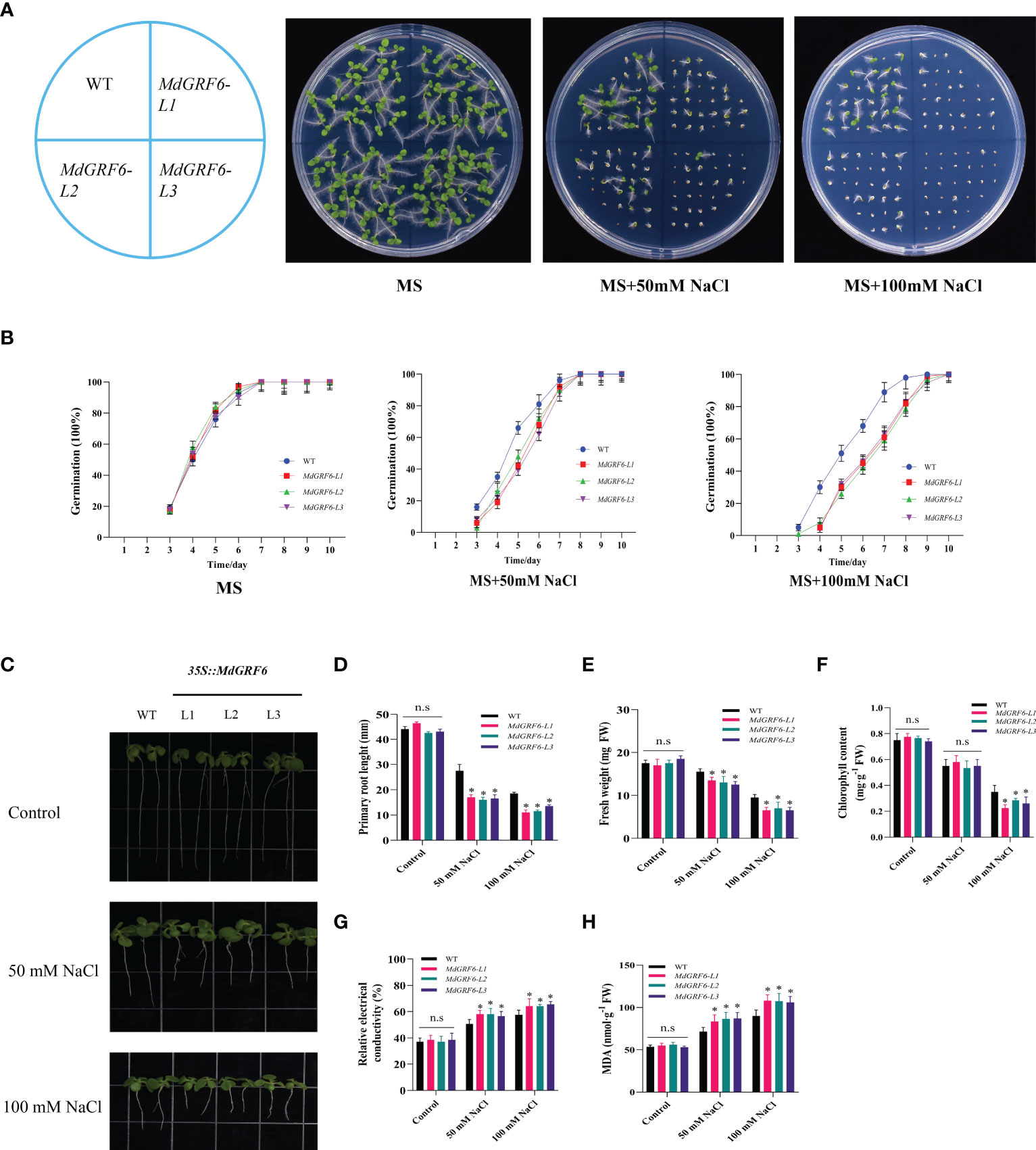

To characterize the function of MdGRF6 under salt stress, three independent transgenic tobacco lines (#1, #2, and #3) were selected for further analyses using RT-qPCR and western blotting (Figure S3). The germination rates of the WT and MdGRF6-OE lines on MS medium with or without NaCl were first determined. The germination rates were comparable on MS-only media (Figures 5A, B). However, supplementation with 50mM or 100mM NaCl significantly reduced the germination rates of all lines, but had the most significant effects in the transgenic plants (Figures 5A, B). Furthermore, the roots were significantly shorter in the MdGRF6-OE transgenic plants compared to WT (Figures 5C, D). Under salt stress, MdGRF6-OE transgenic plants exhibited lower fresh weights and chlorophyll content compared to WT (Figures 5E, F), and exhibited significantly higher electrolyte leakage and MDA content compared to WT (Figures 5G, H).

Figure 5 Salt response of 35S::MdGRF6 transgenic tobacco plants during germination. (A) Effects of salt treatment on the germination of WT and 35S::MdGRF6 transgenic tobacco lines. Germination was assessed at the indicated time. (B) The WT and 35S::MdGRF6 transgenic tobacco lines were grown on MS medium supplemented with 0, 50, or 100 mM NaCl. The seeds germinated after 10 days. Representative seedlings are presented in the images. (C) The seedlings were grown vertically for 4 days on MS medium and then moved to the medium containing different doses of 50 or 100 mM NaCl for an additional 10 days in a vertical position. (D) Root elongation of WT and 35S::MdGRF6 transgenic tobacco seedlings in response to salt stress. (E–H) Fresh weight (E), chlorophyll content (F), relative electrical conductivity (G), and MDA content (H) in WT and 35S::MdGRF6 transgenic tobacco seedlings under control or salt stress conditions. Error bars indicate the means ± SD (n = 3). The asterisks indicate significant differences (LSD test, *P < 0.05; ns, no significant difference).

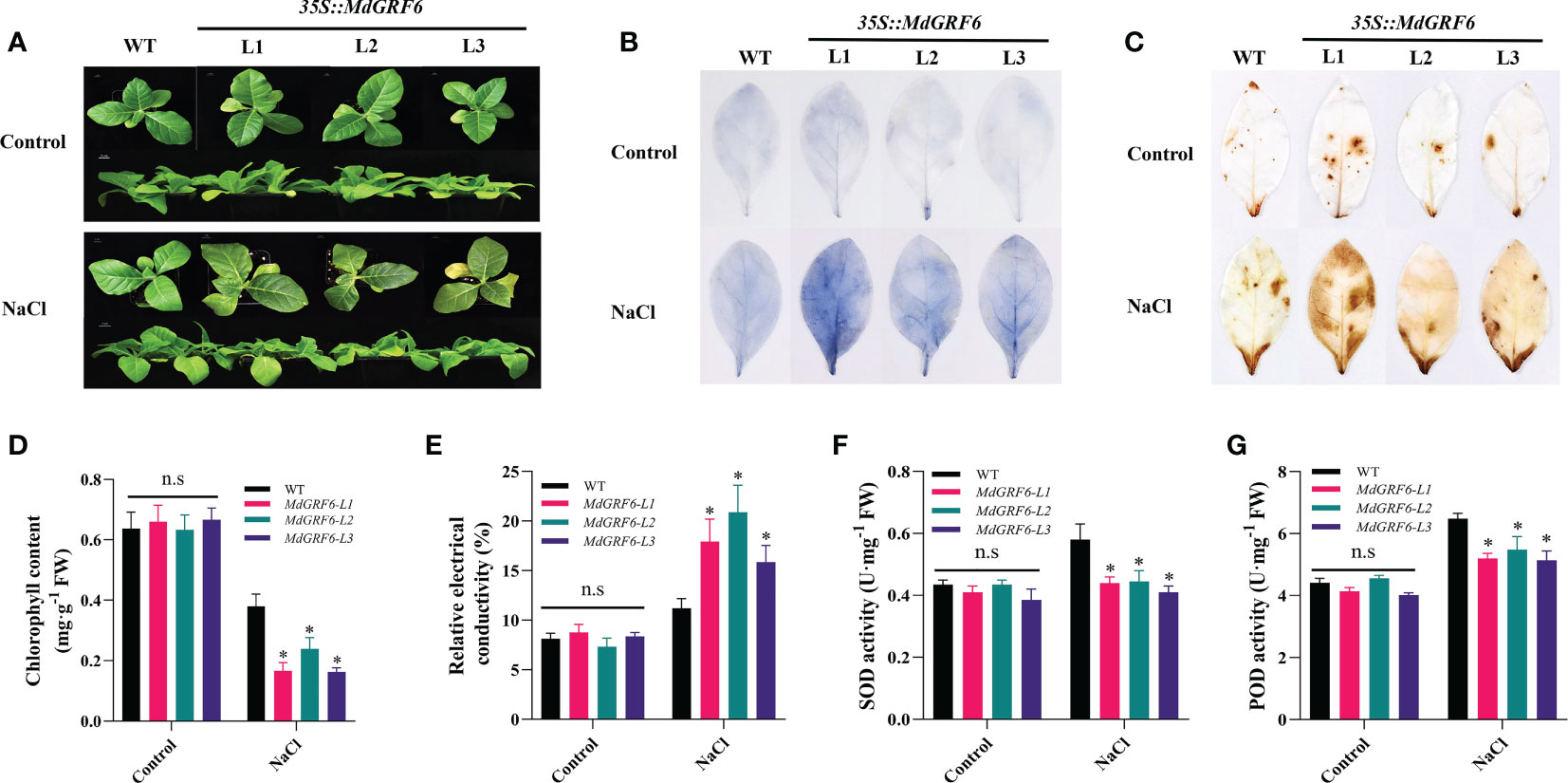

In addition, 30-day-old soil-grown seedlings of WT and transgenic plants were supplied with water or 350 mM NaCl for four weeks. The results of observed phenotypes were consistent with result of germination rates (Figure 6A). ROS levels may increase in response to abiotic stress, and their accumulation is harmful to plant cells (Sun et al., 2010). Under salt treatment, DAB and NBT histochemical staining of transgenic leaves were more intense than in WT than MdGRF6-OE plants, and MdGRF6 transgenic lines accumulated more H2O2 and contents compared to WT plants (Figures 6B, C). Consistent with this data, the activities of important antioxidant enzymes (POD and SOD) displayed lower in MdGRF6-OE plants compared to WT (Figures 6F, G). Furthermore, the increased electrical conductivity and decreased chlorophyll content further confirmed that MdGRF6 overexpression reduced salt tolerance (Figures 6D, E). According to the above results, the ectopic expression of MdGRF6 decreased tolerance to salt stress by impeding the activity of several antioxidant enzymes and causing H2O2 and accumulation.

Figure 6 Effects of salt on the growth of germinated WT and 35S::MdGRF6 transgenic tobacco plants. (A) The phenotype of WT and three transgenic tobacco lines under salinity stress conditions. (B, C) Following salt stress treatments, leaves from MdGRF6 transgenic lines and WT were stained for H2O2 using DAB staining and for using NBT staining. Statistical analysis of (D) chlorophyll content, (E) electrical conductivity, (F) SOD activity, and (G) POD activity in WT and transgenic lines after salt treatments. Error bars indicate the means ± SD (n = 3). The asterisks indicate significant differences (LSD test, *P < 0.05; ns, no significant difference).

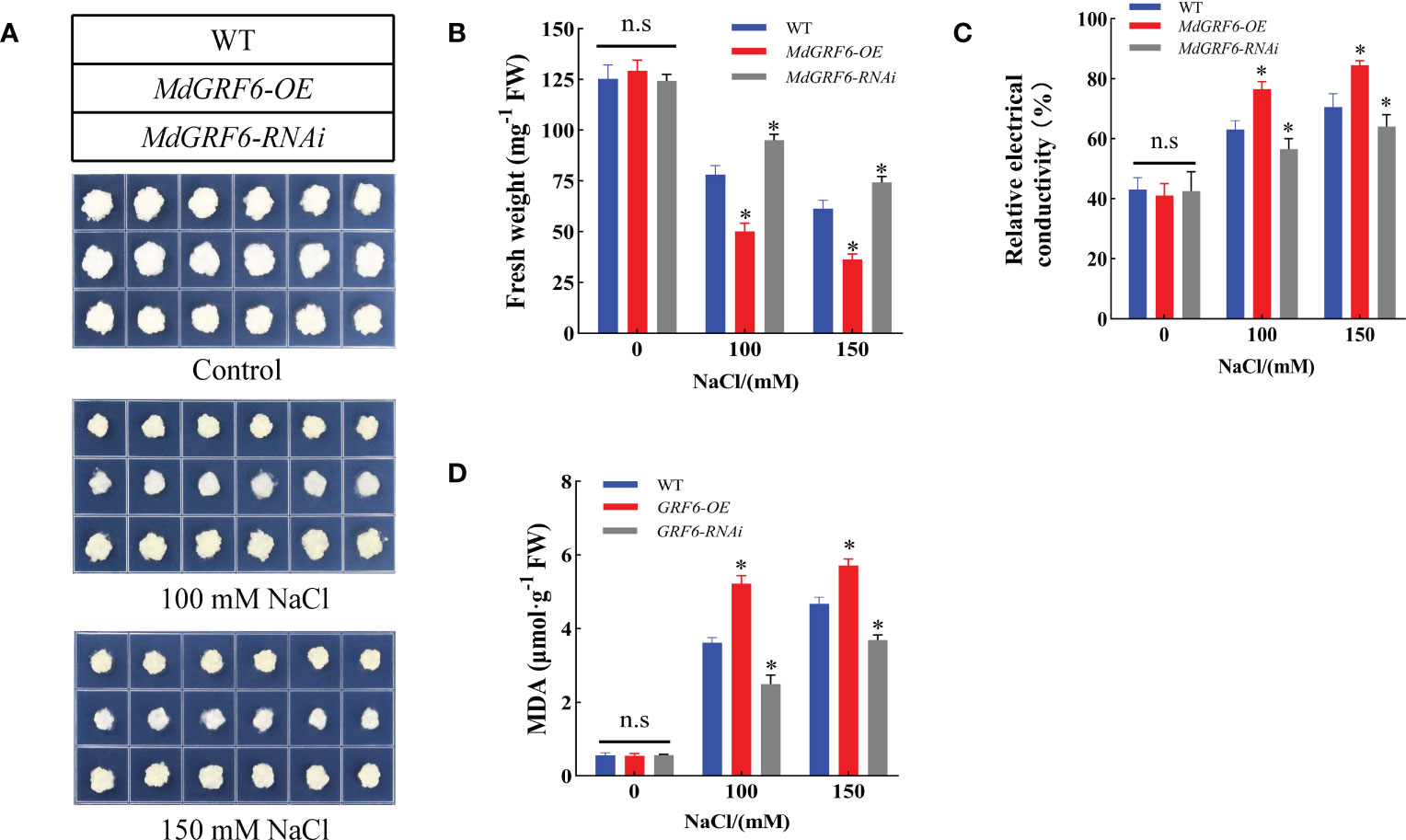

To further investigate MdGRF6 function under salt stress, the MdGRF6-OE and MdGRF6-RNAi transgenic apple calli were obtained. RT-qPCR demonstrated that MdGRF6-OE and MdGRF6-RNAi transgenic calli generated significantly higher or lower expression levels compared to WT, respectively (Figure S4). Then, the 15-day-old WT, MdGRF6-OE, and MdGRF6-RNAi transgenic calli were placed on MS medium containing 100 mM or 150 mM NaCl. The results demonstrate that MdGRF6-OE transgenic calli grew significantly slower than WT, and MdGRF6-RNAi transgenic calli grew much stronger than WT (Figure 7A). In agreement with the observed phenotype, MdGRF6-OE calli exhibited higher MDA level, lower fresh weight, and higher electrical conductivity compared to the WT, whereas MdGRF6-RNAi transgenic calli reduced MDA content, electrical conductivity, and had higher fresh weight under salt stress (Figures 7B–D). Overall, the results suggest that MdGRF6 overexpression improved sensitivity to salt in transgenic apple calli.

Figure 7 MdGRF6 enhanced sensitivity to salt stress in apple. (A) The phenotypes of transgenic and WT apple calli in response to NaCl treatment. The apple calli were placed on the MS medium containing 100 or 150 mM NaCl for 15 days. (B-D) Fresh weight, electrical conductivity, and MDA content of the WT and transgenic apple calli after 15 days under salt treatment. Error bars indicate the means ± SD (n = 3). The asterisks indicate significant differences (LSD test, *P < 0.05; ns, no significant difference).

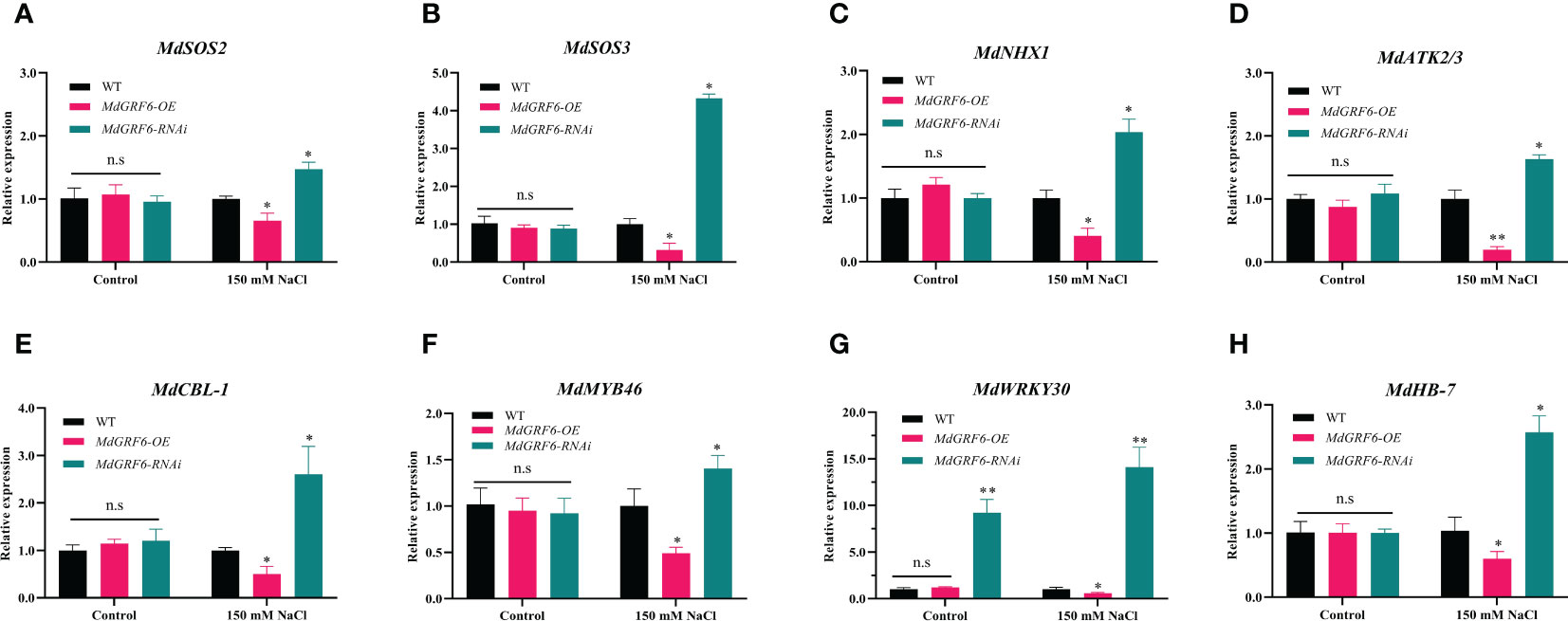

To investigate the molecular mechanisms of MdGRF6-mediated salt stress tolerance, RT-qPCR was used to assess the expression levels of salt stress-related genes (MdSOS2, MdSOS3, MdNHX1, MdATK2/3, MdCBL-1, MdMYB46, MdWRKY30, and MdHB-7). Under normal conditions, the transcript abundance did not differ between the MdGRF6-OE transgenic calli and WT. However, the expression of these genes was considerably lower in MdGRF6-OE transgenic calli, and was higher in MdGRF6-RNAi transgenic calli compared to WT calli under salt stress (Figures 8A–H). The above results suggested that MdGRF6 may negatively regulate these genes under salt stress.

Figure 8 MdGRF6 affected the expression of salt stress-related genes in response to salt stress. (A–H) The relative expression of MdSOS2 (A), MdSOS3 (B), MdNHX1 (C), MdATK2/3 (D) MdCBL-1 (E), MdMYB46 (F), MdWRKY30 (G), and MdHB-7 (H) in WT, MdGRF6-OE and MdGRF6-RNAi transgenic calli under control and salt treatments. Error bars indicate the means ± SD (n = 3). The asterisks indicate significant differences LSD test, **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; ns, no significant difference.

Salinization is one of the most increasingly severe environmental and ecological issues that threaten the limited soil resources on which humans depend and poses a significant constraint on the sustainability of crop yields (Jiao et al., 2019; Hassani et al., 2021; Li et al., 2021). As crucial regulatory proteins in signaling networks involved in adaptation to various abiotic pressures, 14-3-3 proteins have recently attracted considerable interest. In the current study, a 14-3-3 gene (MdGRF6) that negatively regulated salt stress tolerance in apple was identified (Figures 6, 7).

The 14-3-3 proteins contained highly conserved proteins that are widely expressed in all eukaryotes. The family has fifteen and eight members in the Arabidopsis and rice genomes, respectively (DeLille et al., 2001; Rosenquist et al., 2001; Yao et al., 2007). Previously, eighteen or twenty Md14-3-3 gene family members have been identified in the apple genome (Ren et al., 2019; Zuo et al., 2021). Here, twenty Md14-3-3 genes were identified in the apple (Table S1), similar to Ren et al. (2019). However, the MD17G1105100 could not be cloned due to either its low expression level or due its non-existence. The variations in the raw high-throughput genomic sequences were likely due to splicing errors of the DNA fragments. Additionally, variations in apple germplasm resources cannot be completely ruled out (Herndon et al., 2020; Kuo et al., 2020). Previous studies have shown that 14-3-3 proteins have a significant impact on stress resistance (Roberts, 2003). In rice, OsGF14b improves salt tolerance by interacting with OsPCL1, inhibiting its ubiquitination for protection from degradation, and promoting its activity and stability (Wang et al., 2023). Overexpression of both heterologous PvGF14a and PvGF14g in transgenic Arabidopsis under salt stress reduces seed germination and fresh seedling weight, suggesting the involvement of these genes in the negative regulation of salt tolerance in seedlings (Li et al., 2018). In Arabidopsis thaliana, GRF3 is crucial in osmotic stress response and root growth, as well as negatively regulating mitochondrial retrograde control of AOX1a expression via the ROS pathway (Li et al., 2022). Notably, we observed that MdGRF6 was homologous to AtGRF3 and both belonged to the non-ϵ group (Figure 1A). In the present study, MdGRF6 is a negative regulator and its expression was reduced due to salt stress, similar to AtGRF3. The 14-3-3 protein family, therefore, exhibits high conservation of orthologs among different species (Zhou et al., 2014; Li et al., 2018).

Salt stress induces cell membrane damage primarily through osmotic and ion stresses (Golldack et al., 2014; Yoshida et al., 2014). Multiple evidences indicate that the 14-3-3 proteins are primarily localized at the plasma membrane to modify multiple ion channels and alleviate osmotic stress (Yang et al., 2019). Using the 14-3-3 omega (At1g78300) from Arabidopsis as bait, ion transport proteins (Ca2+, K+, and Cl−) were discovered using proteomic analysis of tandem affinity purified 14-3-3 protein complexes (Chang et al., 2009). Relative electrical conductivity reflects the state of the plant membrane system. An increase in the conductivity of the external medium suggests cell membrane damage and ion outflow (Ilik et al., 2018). Similarly, MDA content is an essential indicator of lipid peroxidation in plants and reflects their resistance to external adversity. When various enzymes and membrane systems in plant tissues are disrupted, MDA content increases (Hernandez et al., 2010; Mo et al., 2016). In the present study, the MDA content and relative electrical conductivity were higher in MdGRF6-OE calli and tobacco tissues compared to WT under salt stress. Thus, this study further confirmed that overexpression of MdGRF6 accelerated membrane damage at high salinity.

Under abiotic stresses, plants commonly produce a large amount of ROS, which can damage the mitochondria, chloroplasts, and cell membranes unless the ROS are promptly removed (Li et al., 2015; Jia et al., 2019). Protective substances, such as SOD and POD, can scavenge ROS to alleviate salt stress and protect plant cell membrane structure (Liang et al., 2017; Guo et al., 2020). Many studies have shown that 14-3-3 proteins play a significant role in protection from osmotic and oxidative stress in plants (Yan et al., 2004). For example, RBOHD-dependent H2O2 operates upstream of H+-ATPase and 14-3-3 proteins, required for salt tolerance in pumpkin (Huang et al., 2019). Here, we observed that the activities of antioxidant enzymes SOD and POD were inhibited in the MdGRF6-OE transgenic tobacco (Figures 6F, G). In addition, ROS-induced cellular damage leads to the destruction of photosynthetic machinery including chlorophyll and carotenoids (Cardenas-Perez et al., 2020). Just like this, the chlorophyll contents were markedly decreased in the transgenic tobacco lines compared to WT (Figures 5F, 6D). In Arabidopsis, it was found that 14-3-3 proteins can respond to salt stress by regulating the activity of antioxidant enzymes (Visconti et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019). In general, 14-3-3 proteins can interact with many TFs to regulate salt stress resistance in plants (Chang et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2023). For example, 14-3-3 proteins can interact with GmMYB173 to regulate antioxidant enzyme activity and hydrogen peroxide scavenging in soybean to regulate salt resistance (Pi et al., 2018). Just like this, MdGRF6 protein may regulate the activity of antioxidant enzymes in response to salt stress by interacting with these TFs. In addition, many studies have also confirmed that 14-3-3 proteins can regulate the expression of antioxidant enzyme gene in response to stresses (Manosalva et al., 2011; Li et al., 2014). In apple, many genes such as MdMYB46, MdWRKY30, and MdHB-7 are important components of the gene network that is involved in the regulation of reactive oxygen species-related genes, and they regulate ROS scavenging in response to salt stress (Chen K. et al., 2019; Dong et al., 2020; Zhao et al., 2021). Here, we found that the expression of MdMYB46, MdWRKY30, and MdHB-7 was decreased in MdGRF6-OE plants, and increased in MdGRF6-RNAi plants (Figures 8F–H). This may be due to the fact that MdGRF6 interacts with other proteins to indirectly regulate their expression to modulate salt stress resistance.

Previous studies have shown that many genes can also affect ionic balance (Na+/K+ ratio) pathways in response to salt stress (Chen Z. X. et al., 2019). For example, the MdSOS2, MdSOS3, MdNHX1, MdATK2/3, and MdCBL-1 were reported to involve in salt stress response (Shabala, 2013; Hu et al., 2016; Borkiewicz et al., 2020; Su et al., 2020). We found that the MdSOS2, MdSOS3, MdNHX1, MdATK2/3, and MdCBL-1 genes were upregulated in MdGRF6-RNAi transgenic calli, but decreased in MdGRF6-OE lines under salt stress conditions (Figures 8A–E). Many functional studies have demonstrated that 14-3-3 proteins interact with the WRKY family (Chang et al., 2009; Rushton et al., 2010). In Fortunella crassifolia, FcWRKY40 plays an active role in salt tolerance by directly regulating SOS2 and P5CS1 to control ion homeostasis (Dai et al., 2018). 14-3-3 interacts with the SOS pathway proteins to cope with high salinity, attenuating interactions with AtSOS2 and activating AtSOS2 kinase activity under salt stress conditions in Arabidopsis (Yang et al., 2019). Therefore, we speculated that MdGRF6 may directly regulate the expression of those genes, or indirectly regulate them by interacting with WRKY-TFs.

In this study, the mechanism by which MdGRF6 elevates the salt sensitivity of apple possibly by regulating the activity of the antioxidant enzymes and expression of salt stress-responsive genes were investigated. In conclusion, the molecular biological functions of MdGRF6 were investigated to provide a basis for a more in-depth exploration of the molecular mechanisms of salt stress in apples. Moreover, this study enhanced the understanding of the biological functions of the 14-3-3 gene family in apples.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

QZ and YW conceived and designed the research. YZ provided experimental materials. YZ, WK, JL, XW, LQ, and XK performed the experiments. YZ and QZ analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2018YFD1000300), the Shandong Province Government (SDAIT-06-05), and the Talents of High-Level Scientific Research Foundation of Qingdao Agricultural University.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2023.1161539/full#supplementary-material

An, J. P., Qu, F. J., Yao, J. F., Wang, X. N., You, C. X., Wang, X. F., et al. (2017). The bZIP transcription factor MdHY5 regulates anthocyanin accumulation and nitrate assimilation in apple. Hortic. Res. 4, 17023. doi: 10.1038/hortres.2017.23

Borkiewicz, L., Polkowska-Kowalczyk, L., Ciesla, J., Sowinski, P., Jonczyk, M., Rymaszewski, W., et al. (2020). Expression of maize calcium-dependent protein kinase (ZmCPK11) improves salt tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis plants by regulating sodium and potassium homeostasis and stabilizing photosystem II. Physiol. Plant 168, 38–57. doi: 10.1111/ppl.12938

Brennan, G. P., Jimenez-Mateos, E. M., McKiernan, R. C., Engel, T., Tzivion, G., Henshall, D. C. (2013). Transgenic overexpression of 14-3-3 zeta protects hippocampus against endoplasmic reticulum stress and status epilepticus in vivo. PloS One 8, e54491. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054491

Campo, S., Peris-Peris, C., Montesinos, L., Peñas, G., Messeguer, J., Blanca, S. S. (2012). Expression of the maize ZmGF14-6 gene in rice confers tolerance to drought stress while enhancing susceptibility to pathogen infection. J. Exp. Bot. 63, 983–999. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err328

Cao, H., Xu, Y., Yuan, L., Bian, Y., Wang, L., Zhen, S., et al. (2016). Molecular characterization of the 14-3-3 gene family in Brachypodium distachyon l. reveals high evolutionary conservation and diverse responses to abiotic stresses. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 1099. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01099

Cardenas-Perez, S., Piernik, A., Ludwiczak, A., Duszyn, M., Szmidt-Jaworska, A., Chanona-Perez, J. J. (2020). Image and fractal analysis as a tool for evaluating salinity growth response between two salicornia europaea populations. BMC Plant Biol. 20, 467. doi: 10.1186/s12870-020-02633-8

Chang, I. F., Curran, A., Woolsey, R., Quilici, D., Cushman, J. C., Mittler, R., et al. (2009). Proteomic profiling of tandem affinity purified 14-3-3 protein complexes in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proteomics 9, 2967–2985. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800445

Chang, H. C., Tsai, M. C., Wu, S. S., Chang, I. F. (2019). Regulation of ABI5 expression by ABF3 during salt stress responses in Arabidopsis thaliana. Botanical Stud. 60, 16. doi: 10.1186/s40529-019-0264-z

Chen, C., Chen, H., Zhang, Y., Thomas, H. R., Frank, M. H., He, Y., et al. (2020). TBtools: An integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol. Plant 13, 1194–1202. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2020.06.009

Chen, K., Song, M., Guo, Y., Liu, L., Xue, H., Dai, H., et al. (2019). MdMYB46 could enhance salt and osmotic stress tolerance in apple by directly activating stress-responsive signals. Plant Biotechnol. J. 17, 2341–2355. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13151

Chen, Z. X., Zhao, X. Q., Hu, Z. H., Leng, P. S. (2019). Nitric oxide modulating ion balance in hylotelephium erythrostictum roots subjected to NaCl stress based on the analysis of transcriptome, fluorescence, and ion fluxes. Sci. Rep. 9, 18317. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-54611-2

Cheng, C., Wang, Y., Chai, F., Li, S., Xin, H., Liang, Z. (2018). Genome-wide identification and characterization of the 14-3-3 family in vitis vinifera l. during berry development and cold- and heat-stress response. BMC Genomics 19, 579. doi: 10.1186/s12864-018-4955-8

Dai, W. S., Wang, M., Gong, X. Q., Liu, J. H. (2018). The transcription factor FcWRKY40 of fortunella crassifolia functions positively in salt tolerance through modulation of ion homeostasis and proline biosynthesis by directly regulating SOS2 and P5CS1 homologs. New Phytol. 219, 972–989. doi: 10.1111/nph.15240

DeLille, J. M., Sehnke, P. C., Ferl, R. J. (2001). The arabidopsis 14-3-3 family of signaling regulators. Plant Physiol. 126, 35–38. doi: 10.1104/pp.126.1.35

Dong, Q., Zheng, W., Duan, D., Huang, D., Wang, Q., Liu, C., et al. (2020). MdWRKY30, a group IIa WRKY gene from apple, confers tolerance to salinity and osmotic stresses in transgenic apple callus and Arabidopsis seedlings. Plant Sci. 299, 110611. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2020.110611

Elmayan, T., Fromentin, J., Riondet, C., Alcaraz, G., Blein, J. P., Simon-Plas, F. (2007). Regulation of reactive oxygen species production by a 14-3-3 protein in elicited tobacco cells. Plant Cell Environ. 30, 722–732. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2007.01660.x

Gallois, P., Marinho, P. (1995). Leaf disk transformation using agrobacterium tumefaciens-expression of heterologous genes in tobacco. Methods Mol. Biol. 49, 39–48. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-321-X:39

Golldack, D., Li, C., Mohan, H., Probst, N. (2014). Tolerance to drought and salt stress in plants: Unraveling the signaling networks. Front. Plant Sci. 5, 151. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00151

Guo, H., Huang, Z., Li, M., Hou, Z. (2020). Growth, ionic homeostasis, and physiological responses of cotton under different salt and alkali stresses. Sci. Rep. 10, 21844. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-79045-z

Hassani, A., Azapagic, A., Shokri, N. (2021). Global predictions of primary soil salinization under changing climate in the 21st century. Nat. Commun. 12, 6663. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-26907-3

He, Y., Wu, J., Lv, B., Li, J., Gao, Z., Xu, W., et al. (2015). Involvement of 14-3-3 protein GRF9 in root growth and response under polyethylene glycol-induced water stress. J. Exp. Bot. 66, 2271–2281. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erv149

Hernandez, M., Fernandez-Garcia, N., Diaz-Vivancos, P., Olmos, E. (2010). A different role for hydrogen peroxide and the antioxidative system under short and long salt stress in Brassica oleracea roots. J. Exp. Bot. 61, 521–535. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp321

Herndon, N., Shelton, J. M., Gerischer, L., Ioannidis, P., Ninova, M., Donitz, J., et al. (2020). Enhanced genome assembly and a new official gene set for tribolium castaneum. BMC Genomics 21, 47. doi: 10.1186/s12864-019-6394-6

Hu, D. G., Ma, Q. J., Sun, C. H., Sun, M. H., You, C. X., Hao, Y. J. (2016). Overexpression of MdSOS2L1, a CIPK protein kinase, increases the antioxidant metabolites to enhance salt tolerance in apple and tomato. Physiologia Plantarum 156, 201–214. doi: 10.1111/ppl.12354

Huang, Y., Cao, H., Yang, L., Chen, C., Shabala, L., Xiong, M., et al. (2019). Tissue-specific respiratory burst oxidase homolog-dependent H2O2 signaling to the plasma membrane h+-ATPase confers potassium uptake and salinity tolerance in cucurbitaceae. J. Exp. Bot. 70, 5879–5893. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erz328

Ilik, P., Spundova, M., Sicner, M., Melkovicova, H., Kucerova, Z., Krchnak, P., et al. (2018). Estimating heat tolerance of plants by ion leakage: A new method based on gradual heating. New Phytol. 218, 1278–1287. doi: 10.1111/nph.15097

Ito, T., Nakata, M., Fukazawa, J., Ishida, S., Takahashi, Y. (2014). Scaffold function of Ca2+-dependent protein kinase: Tobacco Ca2+-DEPENDENT PROTEIN KINASE1 transfers 14-3-3 to the substrate REPRESSION OF SHOOT GROWTH after phosphorylation. Plant Physiol. 165, 1737–1750. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.236448

Jahn, T., Fuglsang, A. T., Olsson, A., Bruntrup, I. M., Collinge, D. B., Volkmann, D., et al. (1997). The 14-3-3 protein interacts directly with the c-terminal region of the plant plasma membrane h+-ATPase. Plant Cell 9, 1805–1814. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.10.1805

Jia, T., Wang, J., Chang, W., Fan, X., Sui, X., Song, F. (2019). Proteomics analysis of E. angustifolia seedlings inoculated with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi under salt stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 788. doi: 10.3390/ijms20030788

Jiao, X., Li, Y., Zhang, X., Liu, C., Liang, W., Li, C., et al. (2019). Exogenous dopamine application promotes alkali tolerance of apple seedlings. Plants (Basel) 8, 580. doi: 10.3390/plants8120580

Jiroutova, P., Kovalikova, Z., Toman, J., Dobrovolna, D., Andrys, R. (2021). Complex analysis of antioxidant activity, abscisic acid level, and accumulation of osmotica in apple and cherry in vitro cultures under osmotic stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 7922. doi: 10.3390/ijms22157922

Kuo, R. I., Cheng, Y. Y., Zhang, R. X., Brown, J. W. S., Smith, J., Archibald, A. L., et al. (2020). Illuminating the dark side of the human transcriptome with long read transcript sequencing. BMC Genomics 21, 751. doi: 10.1186/s12864-020-07123-7

Li, Y. Q., Chai, Y. H., Wang, X. S., Huang, L. Y., Luo, X. M., Qiu, C., et al. (2021). Bacterial community in saline farmland soil on the Tibetan plateau: Responding to salinization while resisting extreme environments. BMC Microbiol. 21, 119. doi: 10.1186/s12866-021-02190-6

Li, X., Dhaubhadel, S. (2011). Soybean 14-3-3 gene family: Identification and molecular characterization. Planta 233, 569–582. doi: 10.1007/s00425-010-1315-6

Li, X. Y., Gao, G. L., Li, Y. J., Sun, W. K., He, X. Y., Li, R. H., et al. (2018). Functional roles of two 14-3-3s in response to salt stress in common bean. Acta Physiol. Plant 40, 209. doi: 10.1007/s11738-018-2787-4

Li, H., Liu, D., He, H., Zhang, N., Ge, F., Chen, C. (2013). Overexpression of Pp14-3-3 from pyrus pyrifolia fruit increases drought and salt tolerance in transgenic tobacco plant. Mol. Biol. 47, 591–601. doi: 10.1016/j.ieri.2013.11.077

Li, H. L., Liu, D. Q., He, H., Zhang, N. N., Ge, F., Chen, C. Y. (2014). Molecular cloning of a 14-3-3 protein gene from lilium regale Wilson and overexpression of this gene in tobacco increased resistance to pathogenic fungi. Scientia Hortic. 168, 9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2013.12.034

Li, X., Lyu, W., Cai, Q., Sha, T., Cai, L., Lyu, X., et al. (2022). General regulatory factor 3 regulates the expression of alternative oxidase 1a and the biosynthesis of glucosinolates in cytoplasmic male sterile brassica juncea. Plant Sci. 319, 111244. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2022.111244

Li, W., Zhao, F., Fang, W., Xie, D., Hou, J., Yang, X., et al. (2015). Identification of early salt stress responsive proteins in seedling roots of upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum l.) employing iTRAQ-based proteomic technique. Front. Plant Sci. 6, 732. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00732

Liang, Q. Y., Wu, Y. H., Wang, K., Bai, Z. Y., Liu, Q. L., Pan, Y. Z., et al. (2017). Chrysanthemum WRKY gene DgWRKY5 enhances tolerance to salt stress in transgenic chrysanthemum. Sci. Rep. 7, 4799. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-05170-x

Livak, K. J., Schmittgen, T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-delta delta C(T)) method. Methods 25, 402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262

Łukaszewicz, M., Matysiak-Kata, I., Aksamit, A., Oszmiański, J., Szopa, J. (2002a). 14-3-3 protein regulation of the antioxidant capacity of transgenic potato tubers. Plant Sci. 163, 125–130. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9452(02)00081-X

Manosalva, P. M., Bruce, M., Leach, J. E. (2011). Rice 14-3-3 protein (GF14e) negatively affects cell death and disease resistance. Plant J. 68, 777–787. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04728.x

Mao, K., Dong, Q., Li, C., Liu, C., Ma, F. (2017). Genome wide identification and characterization of apple bHLH transcription factors and expression analysis in response to drought and salt stress. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 480. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00480

Mo, Y., Wang, Y., Yang, R., Zheng, J., Liu, C., Li, H., et al. (2016). Regulation of plant growth, photosynthesis, antioxidation and osmosis by an arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus in watermelon seedlings under well-watered and drought conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 644. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00644

Pardo, J. M., Reddy, M. P., Yang, S., Maggio, A., Huh, G. H., Matsumoto, T., et al. (1998). Stress signaling through Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein phosphatase calcineurin mediates salt adaptation in plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 9681–9686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9681

Pi, E. X., Zhu, C. M., Fan, W., Huang, Y. Y., Qu, L. Q., Li, Y. Y., et al. (2018). Quantitative phosphoproteomic and metabolomic analyses reveal GmMYB173 optimizes flavonoid metabolism in soybean under salt stress. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 17, 1209–1224. doi: 10.1074/mcp.RA117.000417

Ren, Y. R., Yang, Y. Y., Zhang, R., You, C. X., Zhao, Q., Hao, Y. J. (2019). MdGRF11, an apple 14-3-3 protein, acts as a positive regulator of drought and salt tolerance. Plant Sci. 288, 110219. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2019.110219

Roberts, M. R. (2003). 14-3-3 proteins find new partners in plant cell signalling. Trends Plant Sci. 8, 218–223. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(03)00056-6

Rosenquist, M., Alsterfjord, M., Larsson, C., Sommarin, M. (2001). Data mining the Arabidopsis genome reveals fifteen 14-3-3 genes. expression is demonstrated for two out of five novel genes. Plant Physiol. 127, 142–149. doi: 10.1104/pp.127.1.142

Rushton, P. J., Somssich, I. E., Ringler, P., Shen, Q. J. (2010). WRKY transcription factors. Trends Plant Sci. 15, 247–258. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.02.006

Schoonheim, P. J., Veiga, H., Pereira Dda, C., Friso, G., van Wijk, K. J., de Boer, A. H. (2007). A comprehensive analysis of the 14-3-3 interactome in barley leaves using a complementary proteomics and two-hybrid approach. Plant Physiol. 143, 670–683. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.090159

Shabala, S. (2013). Learning from halophytes: Physiological basis and strategies to improve abiotic stress tolerance in crops. Ann. Bot. 112, 1209–1221. doi: 10.1093/aob/mct205

Su, Q., Zheng, X., Tian, Y., Wang, C. (2020). Exogenous brassinolide alleviates salt stress in malus hupehensis rehd. by regulating the transcription of NHX-type Na+(K+)/H+ antiporters. Front. Plant Sci. 11. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.00038

Sun, S. J., Guo, S. Q., Yang, X., Bao, Y. M., Tang, H. J., Sun, H., et al. (2010). Functional analysis of a novel Cys2/His2-type zinc finger protein involved in salt tolerance in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 61, 2807–2818. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq120

Tian, F., Wang, T., Xie, Y., Zhang, J., Hu, J. (2015). Genome-wide identification, classification, and expression analysis of 14-3-3 gene family in populus. PloS One 10, e0123225. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123225

Tripathi, P., Rabara, R. C., Reese, R. N., Miller, M. A., Rohila, J. S., Subramanian, S., et al. (2016). A toolbox of genes, proteins, metabolites and promoters for improving drought tolerance in soybean includes the metabolite coumestrol and stomatal development genes. BMC Genomics 17, 102. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-2420-0

Visconti, S., D’ambrosio, C., Fiorillo, A., Arena, S., Muzi, C., Zottini, M., et al. (2019). Overexpression of 14-3-3 proteins enhances cold tolerance and increases levels of stress-responsive proteins of Arabidopsis plants. Plant Sci. 289, 110215. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2019.110215

Wang, P. H., Lee, C. E., Lin, Y. S., Lee, M. H., Chen, P. Y., Chang, H. C., et al. (2019). The glutamate receptor-like protein GLR3.7 interacts with 14-3-3omega and participates in salt stress response in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Plant Sci. 10, 1169. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.01169

Wang, Q., Lu, X., Chen, X., Malik, W. A., Wang, D., Zhao, L., et al. (2021). Transcriptome analysis of upland cotton revealed novel pathways to scavenge reactive oxygen species (ROS) responding to Na2SO4 tolerance. Sci. Rep. 11, 8670. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-87999-x

Wang, N. N., Shi, Y. Y., Jiang, Q., Li, H., Fan, W. X., Feng, Y., et al. (2023) A 14-3-3 protein positively regulates rice salt tolerance by stabilizing phospholipase C1. Plant Cell Environment 46, 1232–1248. doi: 10.1111/pce.14520

Wang, Y., Wang, L., Zou, Y., Chen, L., Cai, Z., Zhang, S., et al. (2014). Soybean miR172c targets the repressive AP2 transcription factor NNC1 to activate ENOD40 expression and regulate nodule initiation. Plant Cell 26, 4782–4801. doi: 10.1105/tpc.114.131607

Xu, W. F., Shi, W. M. (2006). Expression profiling of the 14-3-3 gene family in response to salt stress and potassium and iron deficiencies in young tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) roots: Analysis by real-time RT-PCR. Ann. Bot. 98, 965–974. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcl189

Yan, J., He, C., Wang, J., Mao, Z., Holaday, S. A., Allen, R. D., et al. (2004). Overexpression of the Arabidopsis 14-3-3 protein GF14 lambda in cotton leads to a “stay-green” phenotype and improves stress tolerance under moderate drought conditions. Plant Cell Physiol. 45, 1007–1014. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pch115

Yang, Z., Wang, C., Xue, Y., Liu, X., Chen, S., Song, C., et al. (2019). Calcium-activated 14-3-3 proteins as a molecular switch in salt stress tolerance. Nat. Commun. 10, 1199. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09181-2

Yang, L., Yan, C., Peng, S., Chen, L., Guo, J., Lu, Y., et al. (2022). Broad-spectrum resistance mechanism of serine protease Sp1 in bacillus licheniformis W10 via dual comparative transcriptome analysis. Front. Microbiol. 13, 974473. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.974473

Yao, Y., Du, Y., Jiang, L., Liu, J. Y. (2007). Molecular analysis and expression patterns of the 14-3-3 gene family from oryza sativa. J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 40 (3), 349–357. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2007.40.3.349

Yasuda, S., Sato, T., Maekawa, S., Aoyama, S., Fukao, Y., Yamaguchi, J. (2014). Phosphorylation of Arabidopsis ubiquitin ligase ATL31 is critical for plant carbon/nitrogen nutrient balance response and controls the stability of 14-3-3 proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 15179–15193. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.533133

Yoshida, T., Mogami, J., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. (2014). ABA-dependent and ABA-independent signaling in response to osmotic stress in plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 21, 133–139. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2014.07.009

Zhang, Z. T., Zhou, Y., Li, Y., Shao, S. Q., Li, B. Y., Shi, H. Y., et al. (2010). Interactome analysis of the six cotton 14-3-3s that are preferentially expressed in fibres and involved in cell elongation. J. Exp. Bot. 61, 3331–3344. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq155

Zhao, S., Wang, H., Jia, X., Gao, H., Mao, K., Ma, F. (2021). The HD-zip I transcription factor MdHB7-like confers tolerance to salinity in transgenic apple (Malus domestica). Physiol. Plant 172, 1452–1464. doi: 10.1111/ppl.13330

Zhou, H., Lin, H., Chen, S., Becker, K., Yang, Y., Zhao, J., et al. (2014). Inhibition of the Arabidopsis salt overly sensitive pathway by 14-3-3 proteins. Plant Cell 26, 1166–1182. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.117069

Keywords: apple, 14-3-3 proteins, MdGRF6, salt stress, negative regulation

Citation: Zhu Y, Kuang W, Leng J, Wang X, Qiu L, Kong X, Wang Y and Zhao Q (2023) The apple 14-3-3 gene MdGRF6 negatively regulates salt tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 14:1161539. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2023.1161539

Received: 08 February 2023; Accepted: 22 March 2023;

Published: 03 April 2023.

Edited by:

Xiaoxu Li, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CAAS), ChinaReviewed by:

Suwen Lu, Nanjing Agricultural University, ChinaCopyright © 2023 Zhu, Kuang, Leng, Wang, Qiu, Kong, Wang and Zhao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Qiang Zhao, emhhb3FpYW5nMDAwNjY2QDE2My5jb20=; Yongzhang Wang, cWF1d3l6QDE2My5jb20=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.