94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Plant Sci., 08 March 2023

Sec. Plant Development and EvoDevo

Volume 14 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2023.1099587

This article is part of the Research TopicPhase Separation in PlantsView all 6 articles

Yuki Nakashima1,2

Yuki Nakashima1,2 Yuka Kobayashi1,3

Yuka Kobayashi1,3 Mizuki Murao1,2

Mizuki Murao1,2 Rika Kato2,4

Rika Kato2,4 Hitoshi Endo5

Hitoshi Endo5 Asuka Higo1,6

Asuka Higo1,6 Rie Iwasaki5

Rie Iwasaki5 Mikiko Kojima7

Mikiko Kojima7 Yumiko Takebayashi7

Yumiko Takebayashi7 Ayato Sato5

Ayato Sato5 Mika Nomoto1,2

Mika Nomoto1,2 Hitoshi Sakakibara7,8

Hitoshi Sakakibara7,8 Yasuomi Tada1,2

Yasuomi Tada1,2 Kenichiro Itami2,5

Kenichiro Itami2,5 Seisuke Kimura9,10

Seisuke Kimura9,10 Shinya Hagihara4

Shinya Hagihara4 Keiko U. Torii5,11

Keiko U. Torii5,11 Naoyuki Uchida1,2,5*

Naoyuki Uchida1,2,5*Plants retain the ability to generate a pluripotent tissue called callus by dedifferentiating somatic cells. A pluripotent callus can also be artificially induced by culturing explants with hormone mixtures of auxin and cytokinin, and an entire body can then be regenerated from the callus. Here we identified a pluripotency-inducing small compound, PLU, that induces the formation of callus with tissue regeneration potency without the external application of either auxin or cytokinin. The PLU-induced callus expressed several marker genes related to pluripotency acquisition via lateral root initiation processes. PLU-induced callus formation required activation of the auxin signaling pathway though the amount of active auxin was reduced by PLU treatment. RNA-seq analysis and subsequent experiments revealed that Heat Shock Protein 90 (HSP90) mediates a significant part of the PLU-initiated early events. We also showed that HSP90-dependent induction of TRANSPORT INHIBITOR RESPONSE 1, an auxin receptor gene, is required for the callus formation by PLU. Collectively, this study provides a new tool for manipulating and investigating the induction of plant pluripotency from a different angle from the conventional method with the external application of hormone mixtures.

Since plants are sessile organisms, they have developed mechanisms thorough evolution that enable flexible responses to ever-changing internal and external situations. One of such abilities is a high degree of plasticity for changing developmental programs (Gaillochet and Lohmann, 2015). Plants can generate a pluripotent tissue called callus by dedifferentiating somatic cells (Ikeuchi et al., 2016; Perez-Garcia and Moreno-Risueno, 2018; Eshed Williams, 2021). In nature, a callus is a mass of highly proliferative cells mainly for injury repair and occasionally acts as a site for pluripotency acquisition to regenerate organs. A pluripotent callus can also be artificially induced from explants using a callus-inducing medium (CIM) which contains appropriate concentrations of auxin and cytokinin at a high auxin/cytokinin ratio (Skoog and Miller, 1957; Ikeuchi et al., 2013; Shin and Seo, 2018). Shoot tissues can then be regenerated by transferring the callus to a cytokinin-rich shoot-inducing medium (SIM). This methodology has been widely used, from basic genetic technologies to agricultural applications. However, because the success of callus induction for many plant species still requires time-consuming attempts with changing the amount and ratio of applied hormones for each species, the development of alternative pluripotency induction methodologies will help overcome this situation by complementing the conventional methodology.

Callus induction by CIM partly shares processes with lateral root formation (Atta et al., 2009; Sugimoto et al., 2010). The formation of lateral root primordia is initiated by the division of differentiated pericycle cells adjacent to protoxylem cells, called xylem pole pericycle (XPP) cells (Peret et al., 2009). CIM induces the formation of XPP-like cells even if the starting explant is derived from any organs, and the formed callus initial exhibits a lateral-root-primordia-like structure (Atta et al., 2009; Sugimoto et al., 2010). CIM-induced callus formation is suppressed in mutants incapable of lateral root initiation, indicating that CIM requires the activation of a lateral root development program for callus induction. The ability of auxin to trigger lateral root initiation (Fukaki et al., 2005; Okushima et al., 2007; Goh et al., 2012) underlies the fact that auxin is an essential ingredient of CIM to initiate callus formation. Callus tissues express genes involved in the formation and maintenance of root meristem such as WUSCHEL-RELATED HOMEOBOX 5 (WOX5) (Haecker et al., 2004), SCARECROW (SCR) (Di Laurenzio et al., 1996), PLETHORA (PLT) family (Aida et al., 2004), and these genes play important roles in establishing pluripotency (Kareem et al., 2015; Kim et al., 2018; Ikeuchi et al., 2019; Shin et al., 2020). When a callus is transferred to SIM, the established pluripotency in the callus enables shoot regeneration that reconstructs shoot meristems and develops shoot tissues. However, although molecular mechanisms for pluripotency induction have been gradually revealed, the current understanding is mainly based on reports on CIM- or wound-induced calli (Ikeuchi et al., 2016; Perez-Garcia and Moreno-Risueno, 2018; Eshed Williams, 2021). Therefore, approaches without hormone treatment or wounding may reveal as-yet-unknown mechanisms of pluripotency induction.

In this study, we identified a novel pluripotency-inducing small compound, PLU, that induces the formation of callus with tissue regeneration potency without external application of either auxin or cytokinin. PLU-induced callus formation required activation of the auxin signaling pathway despite the reduction in the amount of active auxin. Further analyses revealed that Heat Shock Protein 90 (HSP90) mediates a significant part of PLU-initiated early responses, and that PLU potentiates auxin signaling via activation of expression of auxin receptor genes in an HSP90-dependent manner. Collectively, this study provides novel insights and a new tool for understanding and manipulating the induction of plant pluripotency.

The Arabidopsis thaliana Columbia (Col-0) accession was used as the wild-type background in this study, except for J0121 in the C24 accession. slr/iaa14 mutant, tir1/afb-family mutants, and marker lines of AtHB8pro:4xYFP, SCRpro:4xYFP, SUC2pro:4xYFP, J0121 (J0121:GFPer), and DR5:GUS were described previously (Ulmasov et al., 1997; Dharmasiri et al., 2005b; Fukaki et al., 2005; Laplaze et al., 2005; Marques-Bueno et al., 2016; Prigge et al., 2020).

Plasmids constructed in this study and primers used for the construction are listed in Tables S1 and S2, respectively. PLT2pro:Eluc-3xVenus, PLT3pro:Eluc-3xVenus, CUC2pro:Eluc-3xVenus were introduced into Col, and TIR1pro:TIR1-Venus was introduced into tir1 afb2. More than fifteen T1 plants were generated for each construct, and at least two lines harboring the corresponding transgene at a single locus were selected for further analyses.

Seeds were sterilized, stored in the dark at 4°C for a few days, transferred to a half Murashige and Skoog (1/2 MS) medium containing 0.5% sucrose, and grown under continuous white light at 22°C. For liquid culture, seeds were germinated in 24-well plates on a shaker set at 140 rpm. For chemical treatment, seedlings at 1 or 5 days post-inoculation (dpi) were treated with compounds, and samples were observed after incubation for indicated days.

Seedlings were grown in solid 1/2 MS medium for 5 days, and cut at seven mm from the root tip. Root explants were transferred to CIM (1/2 MS medium containing 10 g/l sucrose, 0.5 mg/l 2,4-D and 0.1 mg/l kinetin) or 1/2 MS medium containing 10 g/l sucrose and 40 μM PLU (CAS No.1060777-62-9; Z154270794, Enamine), and cultured for 6 days. For experiments in Figure 2A, 20 g/l glucose was used instead of sucrose as a sugar source. The explants were then transferred to SIM (Gamborg B5 medium containing 20 g/l glucose, 0.2 mg/l indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) and 2.5 mg/l 2-isopentenyladenine.

GUS staining was performed as described previously (Uchida et al., 2007). Briefly, seedlings at 5 dpi were treated with ice-cold 90% acetone for 20 min, washed with water, placed in GUS staining solution (50 mM sodium phosphate [pH 7.0], 10 mM potassium ferricyanide, and 10 mM potassium ferrocyanide, 2 mM X-gluc, 0.2% Triton-X) and vacuumed for 5 min. After incubation at 37°C, root samples were mounted in water and observed.

For observation of cleared samples, FAA-fixed samples were washed with water and cleared with chloral hydrate solution (8 g chloral hydrate, 1ml glycerol, and 2ml water) for at least 1 day. The cleared samples were observed using an Axio Imager A2 microscope (Zeiss) and photographed with an Axiocam 512 color camera (Zeiss). Fluorescence observation was performed using the ClearSee method (Kurihara et al., 2015) with a confocal laser microscope LSM800 or LSM900 (Zeiss). YFP and GFP were excited at 488 nm, and fluorescent images were acquired with the detection range from 490 to 546 nm. Differential interference contrast (DIC) images were taken by a T-PMT detector. Image adjustments were performed using the ImageJ software.

Yeast two hybrid assay was performed as described previously (Uchida et al., 2018). Briefly, EGY48 strain transformed with pSH18-34 (LexA operon::LacZ reporter), pGLex313/TIR1 (LexA-DNA-binding domain fused with TIR1), and pJG4-5/IAA3-DI/DII (B42-transcriptional-activator domain fused with DI/DII domain of IAA3) was incubated in liquid medium composed of minimal SD/Gal/Raf base (Clontech), –His/–Trp/–Ura dropout supplement (Clontech), 50 mM Na-phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), 80 μg/ml X-gal (Wako) and various concentrations of compounds. After 3-day incubation, cultured media containing yeast were transferred to wells in a 96-well plate (white, flat bottom) and observed.

Seedlings at 5 dpi were treated with 40 μM PLU and used for the quantification of IAA and its aspartic-acid-conjugated inactivated form (IAAsp). Each sample was prepared from a pool of 60 whole seedlings. Quantification was performed with ultra-high performance-liquid chromatography (UHPLC)-electrospray interface quadrupole-orbitrap mass spectrometer (UHPLC/Q-Exactive; Thermo Scientific) and an ODS column (ACQUITY UPLC HSS T3, 1.8 µm, 2.1 x 100 mm; Waters) as described previously (Kojima et al., 2009; Shinozaki et al., 2015).

Seedlings at 5 dpi cultured in liquid media were treated with 40 μM PLU for one hour, and total RNAs were extracted and purified using RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (QIAGEN). Each RNA sample was prepared from a pool of 20 whole seedlings. Three independent RNA samples were prepared. 3 μg of purified RNA was used for RNA-seq as described previously (Uchida et al., 2018). The count data were subjected to the trimmed mean of M-value (TMM) normalization, and then transcript expression and digital gene expression were defined using edgeR (Robinson et al., 2010). Gene Ontology (GO) analysis was performed using the PANTHER classification system (http://pantherdb.org/). Venn diagram was drawn using the “Draw Venn Diagram” software at the Van de Peer Lab website (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/Venn/). For drawing a Venn diagram with PLU-upregulated genes, we used the publicly available reported lists of auxin-induced genes, CIM-induced genes, and Lateral Root Initiation (LRI)-related genes (Vanneste et al., 2005; Sugimoto et al., 2010; Uchida et al., 2018).

Each total RNA was extracted from a pool of 20 whole seedlings using an RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (QIAGEN), and quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using a ReverTra Ace qPCR RT Master Mix with gDNA Remover kit (TOYOBO), a SYBR Fast qPCR kit (KAPA), and a Light Cycler 96 (Roche). The primers used for expression analyses are listed in Table S2.

292 genes significantly upregulated more than two-fold upon the PLU treatment (FDR<0.01, logFC>1) were analyzed for enriched motifs by a program that identifies overrepresented cis elements in 1-kb upstream sequences from the transcriptional start site of input genes by comparing surrounding sequences for every pentamer in the upstream sequences as previously reported (Yamamoto et al., 2011). The enriched octamers were aligned according to conserved pentamer sequences and then analyzed using Weblogo version 2.8.2 (Crooks et al., 2004).

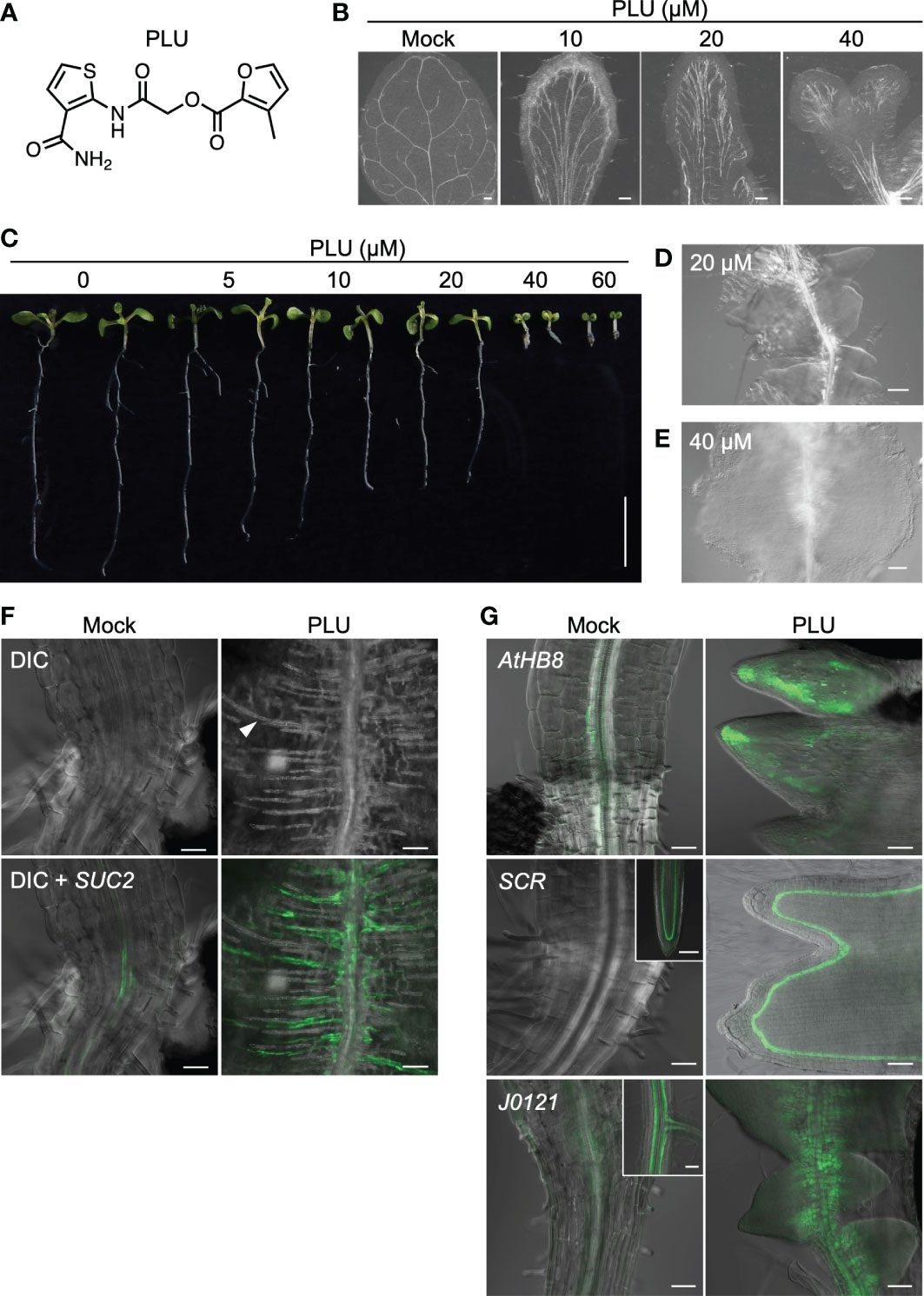

Previously we performed a chemical screen to identify small compounds that increase the number of stomata of Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings using a collection of small synthetic compounds (Ziadi et al., 2017). During the screen of 11,000 compounds, we unexpectedly found that a compound composed of two heteroaromatics, furan and thiophene, tethered by a spacer (formally, 2-Furancarboxylic acid, 3-methyl-, 2-[[3-(aminocarbonyl)-2-thienyl]amino]-2-oxoethyl ester) (Figure 1A), affects leaf venation patterns. We named this compound PLU (Pluripotency-inducing compound; see the later explanation). When wild-type seedlings were incubated with different concentrations of PLU in liquid culture, true leaves exhibited abnormal venation patterns in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 1B). Upon 10 µM PLU treatment, vascular strands were formed parallel in the central regions, and leaves were occasionally fused when treated at concentrations higher than 20 µM. Cotyledons of PLU-treated plants ectopically developed many short secondary free-ending veins from primary loop-shaped veins (Figure S1).

Figure 1 PLU induces abnormal venation patterns and the formation of callus. (A) The molecular structure of PLU. (B) Differential Interference Contrast (DIC) images of cleared true leaves of wild-type seedlings treated with DMSO (mock) or PLU from 1 to 11 days post inoculation (dpi). Scale bars: 200 μm. (C) PLU-treated seedlings. Scale bar: 1 cm. (D, E) Close-up image of roots below the hypocotyl-root junction at 20 µM treatment (D) and the hypocotyl-root junction at 40 µM treatment (E). Scale bars: 100 μm. (F, G) SUC2pro:4xYFP reporter plants were treated with DMSO (mock) or 40 µM PLU at 1 dpi, and regions around the hypocotyl-root junction were observed at 8 dpi. Fluorescent signals of reporter lines were merged with DIC images. In DIC microscopy, thick secondary cell walls of xylem tracheary elements can be easily recognized (the white arrowhead indicates a representative signal). 20 µM PLU-treated AtHB8pro:4xYFP, SCRpro:4xYFP, and J0121:GFPer (G). Insets show original expression patterns of the reporters in the roots of mock-treated plants. Scale bar: 50 µm.

PLU treatment also influenced the growth of the whole seedling body (Figure 1C). Root growth was attenuated in a dose-dependent manner, and growth of both aboveground tissues and roots was severely inhibited at higher than 40 µM. Intriguingly, 20 µM treatment led to the formation of structures that appeared to consist of closely formed multiple lateral root primordia along the primary root just below the hypocotyl-root junction (Figure 1D), and 40 µM treatment induced a large cell mass, or callus (Figure 1E).

Close observation of the PLU-induced callus showed the ectopic formation of xylem strands, which ran in the direction vertical to the original vascular bundle of the primary root (Figure 1F). SUC2pro:4xYFP, a marker of mature phloem companion cells, was also expressed along the ectopically formed xylem strands in the PLU-induced callus. AtHB8 (AtHB8pro:4xYFP), a marker gene for vascular stem cells (procambial cells) that produce both xylem and phloem (Baima et al., 1995) was expressed around the central part of root vasculatures in mock-treated plants, while it was broadly expressed in the PLU-induced callus (Figure 1G). In this callus, SCR, which is required for the proper maintenance of root meristem (Di Laurenzio et al., 1996), and J0121, an enhancer-trap line for XPP cells acting as initial cells for lateral root formation (Laplaze et al., 2005), were also expressed (Figure 1G). SCR (SCRpro:4xYFP) was expressed in quiescent center cells and developing endodermal cells at the root tip in mock-treated plants, and the expression disappeared in mature regions, including the hypocotyl-root junction, while it was expressed in the PLU-induced callus, at one layer located a-few-cell apart from the epidermis. J0121 (J0121:GFPer) was observed as two strands of XPP cells along vasculatures in developing roots of mock-treated plants, and the signal gradually became dim toward the hypocotyl. In the PLU-induced callus, the J0121 signals were clearly detected and expanded toward the cell mas beyond the original expression domain. These results suggested that the PLU-induced callus may retain some characteristics related to root meristem and lateral root development.

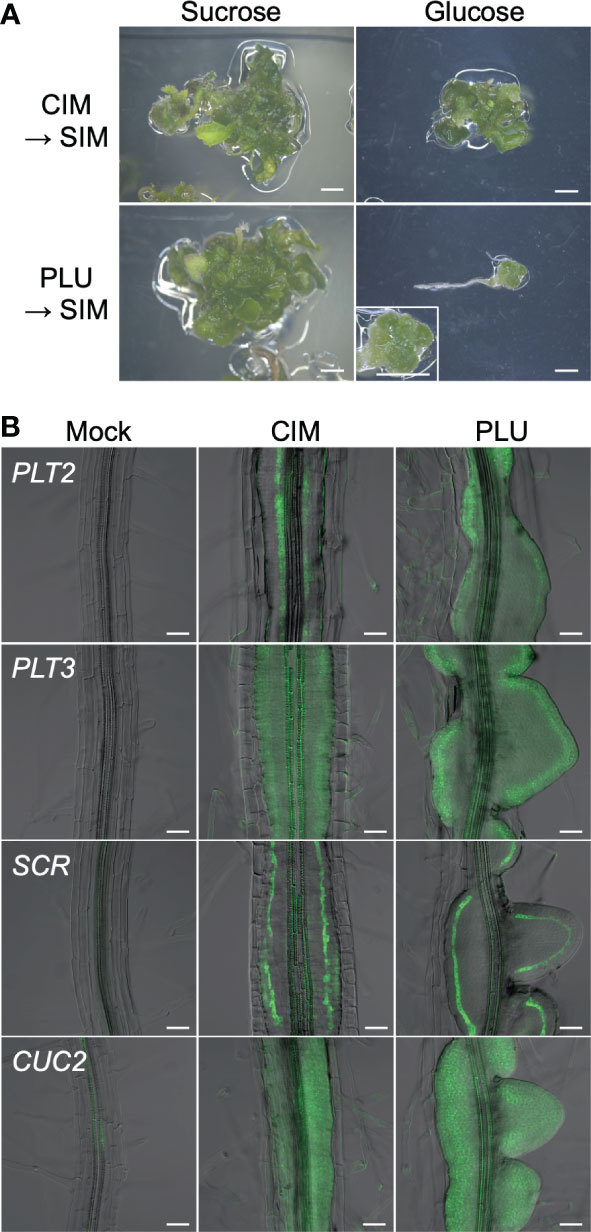

Expression of SCR and J0121 is known as characteristics of pluripotent callus that retains shoot regeneration potency (Sugimoto et al., 2010; Ikeuchi et al., 2019; Shin et al., 2020). Furthermore, callus formation shares processes with lateral root formation, such as being initiated by the division of XPP cells (Atta et al., 2009; Sugimoto et al., 2010). Because the PLU-induced callus expressed SCR and J0121 (Figure 1G) and resembled lateral root primordia (Figure 1D), the idea was raised that the PLU-induced callus may retain pluripotency for shoot regeneration like a callus induced by a conventional CIM containing auxin and cytokinin. To test this idea, root explants from wild-type seedlings were cultured for 6 days on CIM or the standard 1/2 MS medium supplemented with 40 µM PLU, and then transferred to cytokinin-rich SIM. After culturing on SIM, green shoot tissues were regenerated in either case (Figure 2A, left). This result showed that PLU-treated explants acquired pluripotency to regenerate shoots and that, unlike the conventional CIM, PLU did not require either externally applied auxin or cytokinin for the pluripotency induction. In these experiments, we used sucrose as a sugar source during the CIM or PLU treatments, while glucose can also be used instead of sucrose for CIM (Atta et al., 2009; Sugimoto et al., 2010). We next examined whether the sugar type influences the induction of shoot regeneration potency by PLU (Figure 2A). When glucose was used for CIM- or PLU-treatment, CIM-treated explants regenerated shoot tissues on SIM, but not PLU-treated ones. PLU-treated explants only formed a mass of green cells that did not develop further. These results indicated that PLU shows the sucrose preference as a sugar source for the induction of regeneration potency. It is known that CIM-induced callus expresses genes important for establishing pluripotency through lateral root initiation processes, such as PLT2, PLT3, SCR, and CUP SHAPED COTELYDON 2 (CUC2) (Gordon et al., 2007; Kareem et al., 2015; Kim et al., 2018). PLU-induced callus expressed these genes, like CIM-induced callus (Figure 2B).

Figure 2 PLU-induced callus retains shoot regeneration potency. (A) Root explants from wild-type seedlings at 5 dpi were cultured on CIM or 40 µM PLU-containing medium with sucrose or glucose for 6 days, transferred to SIM, and further cultured for 19 days. The enlarged image in the lower-right panel shows a mass of green cells that did not develop further. Scale bars: 2 mm. (B) Roots explants from seedlings of reporter lines at 5 dpi were cultured on PLU-supplemented medium or CIM for 6 days. Fluorescent signals of PLT2pro:Eluc-3xVenus, PLT3pro:Eluc-3xVenus SCRpro:4xYFP, and CUC2pro:Eluc-3xVenus reporters were merged with DIC images. Scale bars: 50 µm.

To investigate PLU-initiated early events, we performed RNA-seq analysis 1 hour after treatment of wild-type seedlings with PLU and identified 292 genes upregulated more than two-fold (FDR<0.01) (Dataset S1). Gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis showed that the GO categories, “response to endogenous stimulus”, “response to hormone”, and “response to auxin” were enriched with extremely low P-values (Table S3). In the hierarchy of GO terms, “response to endogenous stimulus” and “response to hormone” includes “response to auxin” as a subcategory (child category), indicating that “response to auxin” could be the most intrinsically enriched category. When we compared the PLU-upregulated genes with the publicly available list of genes induced by IAA treatment (Dataset S1) (Uchida et al., 2018), 82 of 292 PLU-induced genes overlapped with the IAA-induced genes, including well-known auxin-inducible genes, 22 SMALL AUXIN UP RNA genes, 8 IAA/AUX genes, 4 GRETCHEN HAGEN 3 (GH3) genes, and 3 LATERAL ORGAN BOUNDARIES-DOMAIN genes (Okushima et al., 2007; Paponov et al., 2008). These results suggested that the activation of auxin responses could be involved in the action of PLU.

The induction of a significant number of auxin-response-related genes by PLU raised the possibility that PLU may act as an auxin agonist. Auxin regulates downstream responses via its receptors, TRANSPORT INHIBITOR RESPONSE 1 (TIR1) and AUXIN SIGNALING F-BOX (AFB) family proteins (Dharmasiri et al., 2005a; Dharmasiri et al., 2005b; Kepinski and Leyser, 2005; Parry et al., 2009; Prigge et al., 2020). Auxin binding to TIR1 promotes the interaction between TIR1 and AUXIN/INDOLE-3-ACETIC ACID (AUX/IAA) proteins (Tan et al., 2007). We examined whether PLU directly binds to TIR1 as an auxin agonist by the previously reported yeast two-hybrid assay that detects the TIR1-AUX/IAA protein interaction (Uchida et al., 2018). Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), a major natural auxin, effectively promoted the interaction as low as 0.1 µM, while PLU showed no effects even at 100 µM (Figure 3A). This result suggested that PLU does not bind to TIR1, consistent with no apparent similarity in molecular structure between PLU and IAA (Figure 1A).

Figure 3 PLU slowly activates DR5 responses differently from IAA. (A) IAA and PLU at various concentrations were applied to the yeast two-hybrid assay that shows the TIR1-AUX/IAA interaction by blue color. (B) 5-dpi DR5:GUS seedlings were treated with DMSO (mock), 0.5 µM IAA, or 40 µM PLU. GUS staining was performed at indicated time points after compound treatment. Scale bars: 100 μm.

Next, we compared the time of the DR5:GUS activation at the root tip after IAA or PLU treatments (Figure 3B). Strong GUS signals were detected at the entire root tip 3 hours after the treatment of 0.5 µM IAA, showing that, as expected, IAA rapidly activates auxin responses. By contrast, the application of 40 µM PLU, which is sufficient for the induction of callus formation (Figure 1), induced no apparent changes in 3 hours and even 24 hours, and GUS signals were eventually enhanced after 48 hours, indicating that PLU slowly activates DR5-monitored auxin responses differently from IAA.

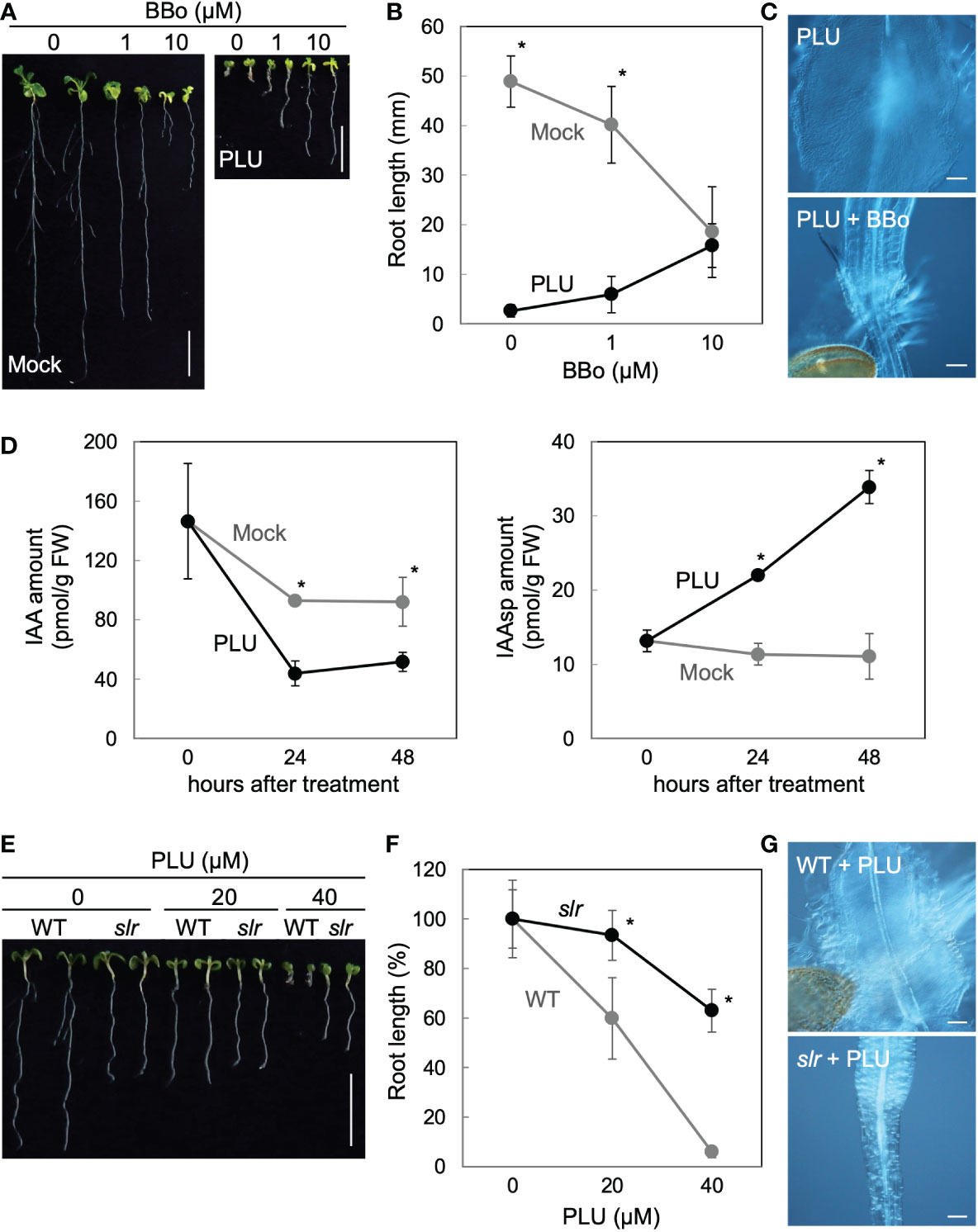

Because the slow activation of DR5 responses by PLU could be mediated through the action of endogenous auxin, we investigated how the inhibition of endogenous auxin biosynthesis affects PLU-induced phenomena. When auxin biosynthesis was attenuated by the treatment of 4-biphenylboronic acid (BBo), an inhibitor of YUCCA-family auxin biosynthesis enzymes (Kakei et al., 2015), BBo alleviated root shortening by PLU in a dose-dependent manner and also blocked callus formation at 10 µM (Figures 4A-C). Another inhibitor of YUCCA enzymes, Yucasin (Nishimura et al., 2014), which is structurally unrelated to BBo, also suppressed the PLU-induced root shortening (Figure S2). These results showed that endogenous auxin is required for PLU-induced effects. Next, we quantified amounts of IAA and its inactivated form in PLU-treated plants. IAA, a major active form of auxin, is known to be converted into inactive aspartic-acid-conjugated form (indole-3-acetyl-aspartate: IAAsp) by GH3-family enzymes (Staswick et al., 2005; Kramer and Ackelsberg, 2015). PLU treatment decreased the IAA amount within 24 hours and increased the IAAsp amount (Figure 4D), consistent with our RNA-seq analysis showing that PLU treatment upregulates the expression of GH3 genes. Since PLU requires endogenous auxin to exert its effects despite the reduction of endogenous IAA, it is likely that PLU enhances sensitivity to auxin.

Figure 4 PLU requires an auxin-mediated transcriptional pathway to induce callus formation despite reducing endogenous IAA. (A–C) (A) Photos of 8-dpi wild-type seedlings grown on media containing indicated concentrations of BBo with or without 40 µM PLU (Scale bars: 1 cm), (B) the quantification graph of root length data in (A), and (C) DIC images at the hypocotyl-root junction of 40 µM PLU-treated seedlings cultured with or without 10 µM BBo (Scale bar: 100 µm). (D) Quantification graphs of amounts of IAA and its aspartic-acid-conjugated form (IAAsp) per fresh weight (FW) of samples. 5-dpi wild-type seedlings were treated with 40 μM PLU and harvested for quantification at indicated times. (E–G) (E) Photos of 8-dpi wild-type or slr seedlings grown on media containing indicated concentrations of PLU (Scale bar: 1 cm), (F) the quantification graph of root length data in (E), and (G) DIC images at the hypocotyl-root junction of 40 µM PLU-treated seedlings (Scale bar: 100 µm). The average root length without compound treatment is set at 100% in (F). In graphs, the mean ± standard deviation (n=10 for B and F, or n=3 for D) is shown. * indicates significant differences between mock and PLU treatments, or WT and slr at P < 0.05 based on Welch’s t test (two-tailed).

PLU ectopically activated DR5 (Figure 3), which is a transcriptional output reporter of auxin signaling (Ulmasov et al., 1997). To examine whether PLU requires the auxin-mediated transcriptional pathway to induce callus formation, we applied PLU to the solitary root/indole-3-acetic-acid 14 (slr/iaa14) mutant, in which the auxin-triggered transcriptional activation is attenuated due to a dominant mutation in IAA14 (Fukaki et al., 2005). The slr mutation markedly suppressed both root shortening and callus formation induced by 40 µM PLU (Figures 4E-G), showing that auxin-regulated transcription mediates PLU effects.

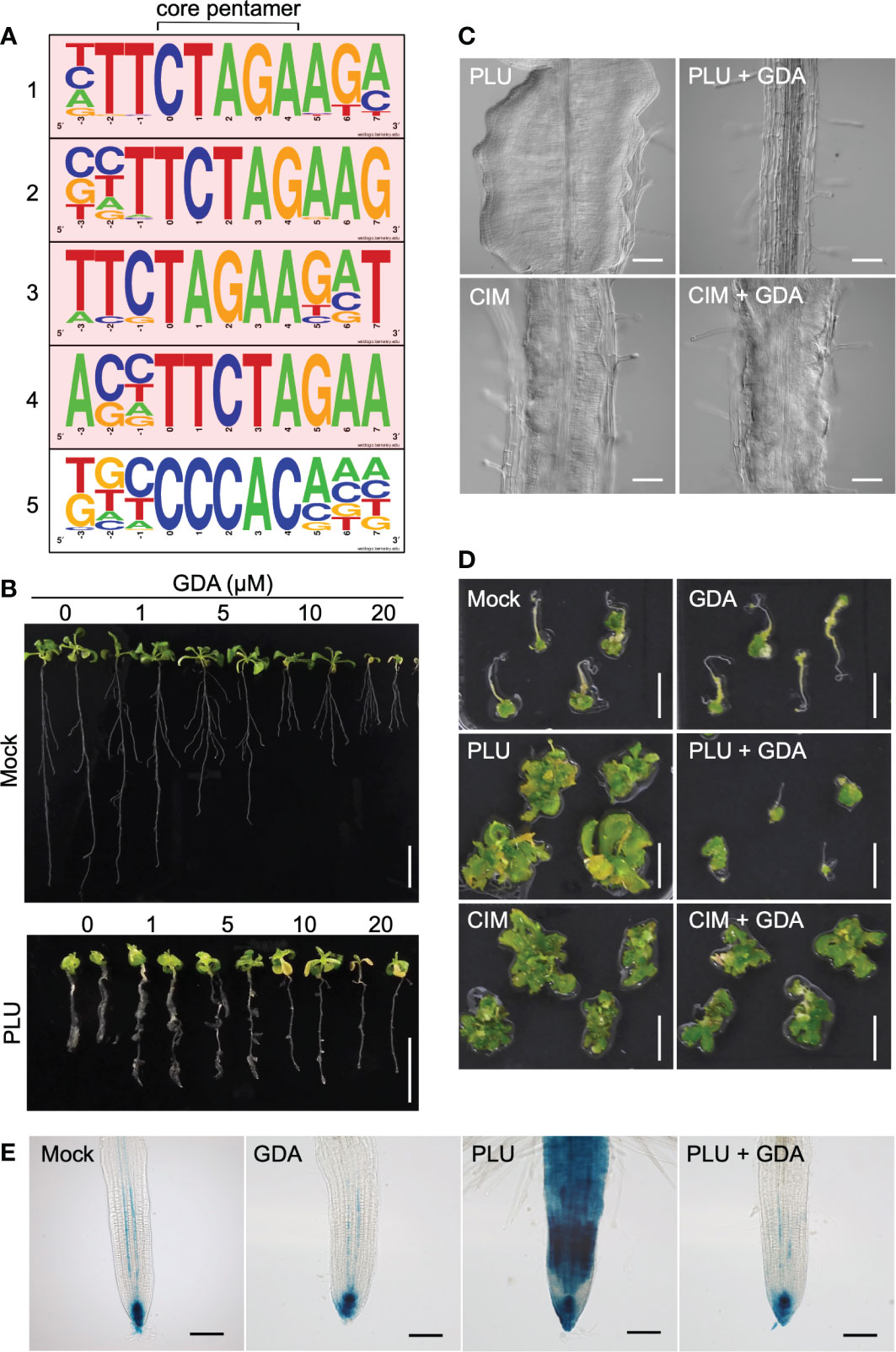

The rapid auxin-related responses within 1 hour and the slow DR5-monitored auxin responses may be mediated through distinct regulation. When we drew the Venn diagram showing the number of genes overlapping among the PLU-induced genes, the IAA-induced genes, and also publicly available lists of CIM-induced genes (Sugimoto et al., 2010) and lateral-root-initiation (LRI)-related genes (Vanneste et al., 2005) (Figure S3, Dataset S1), the majority of the PLU-induced genes (184 of 292 genes) did not overlap with genes in the compared lists, suggesting that PLU may activate some specific mechanisms to control these downstream genes. To further explore a PLU-initiated mechanism, we next surveyed cis-regulatory elements overrepresented in upstream promoter regions of the PLU-upregulated genes (Yamamoto et al., 2011). Strikingly, 52 genes shared the most overrepresented sequence TTCTAGAA, which preferred a G at its 3’ position (Figures 5A, S4, Dataset S1). By contrast, only 1 of the 81 PLU-downregulated genes retained the TTCTAGAA sequence in its 1-kb upstream sequence (Figure S4, Dataset S1). The TTCTAGAA sequence is known as Heat Shock Element (HSE), a recognition motif of Heat Shock Factors (HSFs) (Guhathakurta et al., 2002; Manuel et al., 2002). Because Heat Shock Protein 90 (HSP90) plays a central role in regulating HSFs (Scharf et al., 2012; Guo et al., 2016; Jacob et al., 2017), the overrepresentation of HSE in upstream sequences of PLU-induced genes suggested the involvement of HSP90 in the initial action of PLU.

Figure 5 PLU requires HSP90 activity to trigger DR5 responses and the callus formation. (A) The top five motifs overrepresented in 1-kb upstream sequences of 292 genes upregulated more than two-fold 1 hour after PLU treatment by a program that identifies overrepresented cis elements by comparing surrounding sequences for every pentamer in input sequences. The core pentamer of each overrepresented motif is positioned at the center. The top four motifs containing TTCTAGAA sequences are highlighted in pink. (B) 5-dpi wild-type seedlings were transferred to media containing indicated concentrations of GDA with or without 40 µM PLU, and observed at 14 dpi. Scale bars: 1 cm. (C) DIC images of roots of 12-dpi seedlings. 5-dpi wild-type seedlings grown in normal media were transferred to media containing 40 µM PLU- or CIM with or without 20 µM GDA. Scale bars: 100 µm. (D) Root explants from wild-type seedlings at 5 dpi were cultured on 40 µM PLU- or CIM-containing medium with or without 20 µM GDA for 6 days, transferred to SIM, and observed 22 days after the transfer to SIM. Scale bar: 1 cm. (E) 5-dpi DR5:GUS seedlings were treated with or without 40 µM PLU and/or 20 µM GDA, and GUS staining was performed after 48-hour incubation. Scale bar: 40 µm.

To examine whether PLU requires HSP90 activity to trigger downstream events, we investigated how the reduction of HSP90 activity influences PLU-induced phenomena using Geldanamycin (GDA), a specific inhibitor of HSP90 proteins without known off-target activity (Pearl and Prodromou, 2006; Wang et al., 2016), which has been widely used to overcome the difficulties in the genetic loss-of-function analysis due to high redundancy of HSP90-family genes (Stebbins et al., 1997; Krishna and Gloor, 2001; Queitsch et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2016). When wild-type plants were treated with GDA from 1 to 14 dpi, no obvious growth inhibition was observed even with 20 µM GDA (Figure S5), indicating that GDA does not retain general non-specific deleterious effects. When 5-dpi wild-type seedlings were transferred to GDA-containing media (Figure 5B), the growth of the primary root was attenuated, while lateral roots appeared to be less affected. It is likely that responses to GDA, which may include acclimation or desensitization responses, vary by growth stage and developmental context. The primary root of PLU-treated seedlings grew longer in the presence of GDA than in no GDA condition. GDA treatment completely suppressed PLU-induced callus formation, while CIM induced callus regardless of the presence or absence of GDA (Figure 5C). Shoot regeneration experiments, in which PLU- and/or GDA-treated explants were transferred to SIM, showed that PLU did not induce shoot regeneration potency in the presence of GDA (Figure 5D). By contrast, CIM-treated samples developed shoot tissues regardless of the presence or absence of GDA (Figure 5D), consistent with the result that CIM induced callus even in the presence of GDA. These results indicated that HSP90 activity is required for PLU to induce pluripotency.

It was reported that ectopic activation of auxin signaling by exogenously applied IAA is suppressed by GDA (Wang et al., 2016), raising the possibility that PLU-induced slow activation of auxin responses (Figure 3) may also require HSP90 activity. To examine this possibility, DR5:GUS seedlings were analyzed 48 hours after PLU treatment in the presence or absence of GDA (Figure 5E). In mock-treated seedlings, GUS signals were detected strongly at the root tip and weakly in protoxylem cell files within the stele (De Smet et al., 2007), and GDA did not alter the original DR5:GUS pattern. On the other hand, GDA blocked the activation of DR5:GUS by PLU, bringing the PLU-induced GUS pattern back to the normal pattern as if there had been no PLU treatment, showing that, although normal auxin responses do not require HSP90 activity, PLU requires it to activate ectopic auxin responses.

To investigate how HSP90 enables PLU to induce auxin responses, we focused on past reports that a variety of stresses such as heat, osmotic stress, drought, and pathogens affects the expression of TIR1/AFB-family auxin receptors (Navarro et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2016; Kalve et al., 2020). It was also reported that HSP90 mediates heat-induced accumulation of TIR1/AFB-family proteins (Wang et al., 2016) and that overexpression of TIR1 enhances sensitivity to auxin (Chen et al., 2011; Windels et al., 2014). We hypothesized that PLU may induce the expression of TIR1/AFB family and that this process may require HSP90 activity. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed TIR1pro:TIR1-Venus reporter plants. TIR1 proteins localize in the nucleus for transcriptional regulation (Dharmasiri et al., 2005b). PLU treatment of TIR1pro:TIR1-Venus seedlings induced nuclear accumulation of Venus signals in cells around vasculatures of roots within 48 hours (Figure 6A), in sharp contrast to the mock-treated case that only exhibited strong autofluorescence of thick secondary cell walls of xylem. The nuclear accumulation of TIR1-Venus signals was maintained in several layers of cells of developing callus (Figure 6B). GDA blocked the PLU-induced TIR1-Venus expression (Figure 6A), indicating that PLU requires HSP90 activity to activate TIR1. qRT-PCR analysis showed that the 48-hour PLU treatment increased expression levels of endogenous TIR1 and AFB genes (Figure S6) and that the co-treatment of GDA suppressed the increase, except for the case of AFB2. The expression of TIR1 and AFB3 was kept at the level of the mock condition even in the presence of GDA, which is consistent with the result that, although GDA blocked the PLU-induced ectopic activation of auxin responses, it did not cause apparent changes in normal auxin responses (Figure 5E). The large reduction of AFB1 expression by GDA and the resistance of the PLU-induced AFB2 increase to GDA (Figure S6) suggest that the involvement of HSP90 in transcriptional control is not uniform among TIR1/AFB genes.

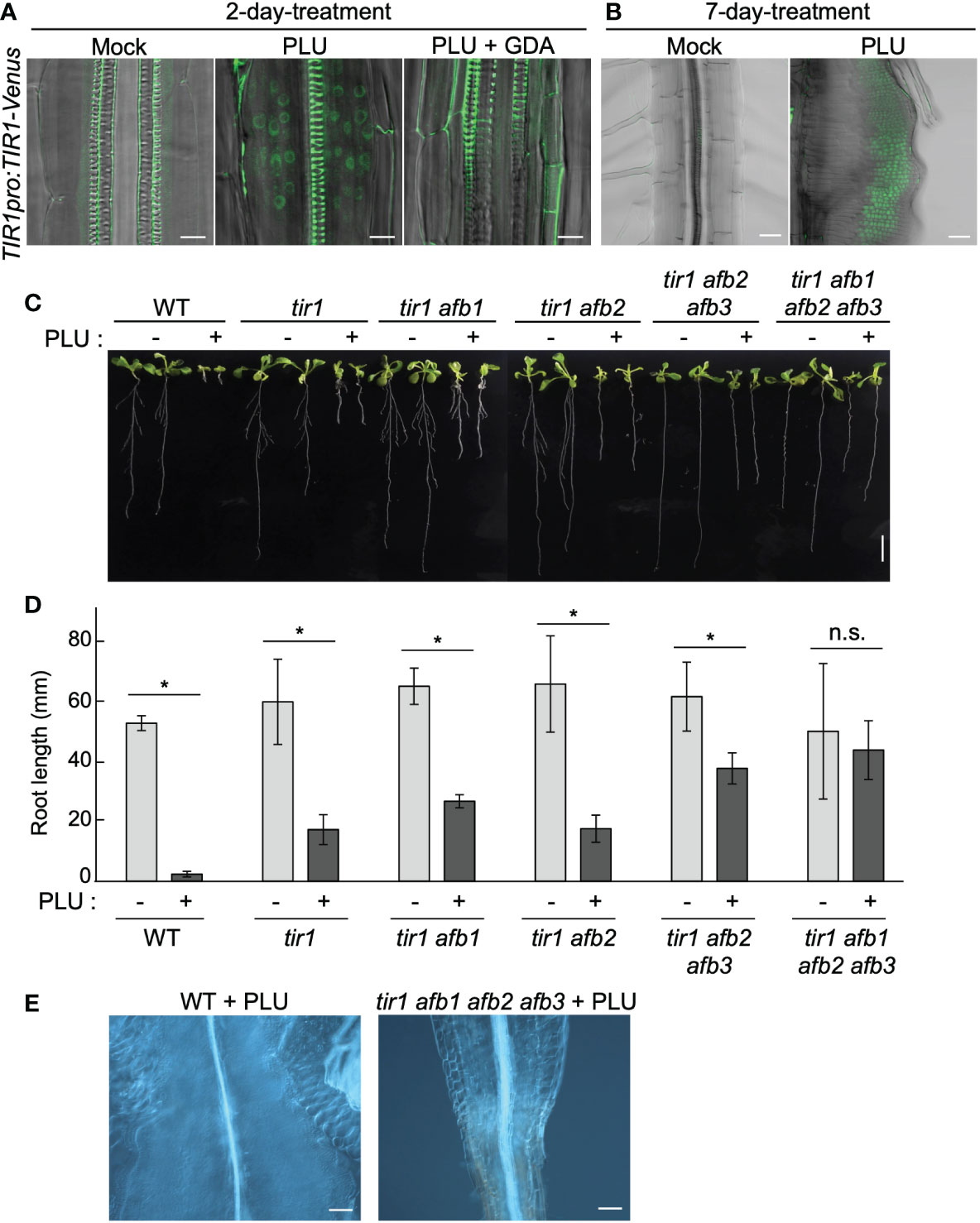

Figure 6 HSP90-dependent induction of auxin receptors is required for callus formation by PLU. (A, B) 5-dpi TIR1pro:TIR1-Venus seedlings were treated with or without 40 µM PLU and/or 20 µM GDA and observed after 2-day incubation (Scale bar: 50 µm) (A) or 7-day incubation (Scale bar: 10 µm) (B). Fluorescent signals were merged with DIC images. Note that xylem strands show strong self-fluorescence due to thick secondary cell wall. (C) Photos of 14-dpi wild-type or tir1/afb-family mutant seedlings grown on media containing DMSO (mock) or 40 µM PLU (Scale bar: 1 cm). Because some tir1/afb-family multiply mutant lines frequently fail to produce the primary root (Dharmasiri et al., 2005b), only seedlings that produced primary root were used for experiments. (D) The quantification graph of root length data in (C). The mean ± standard deviation is shown. Sample size is n=8 except for tir1 afb1 afb2 afb3 (n=6). * indicates significant differences from mock treatment at P < 0.05, and n.s. indicates no significant difference based on Welch’s t test (two-tailed). (E) DIC images at the hypocotyl-root junction of 40 µM PLU-treated seedlings (Scale bar: 100 µm).

To examine the importance of TIR1/AFB family for callus induction by PLU, we analyzed how tir1/afb-family mutants react to PLU. Because TIR1/AFB-family members retain redundant functions (Dharmasiri et al., 2005b; Parry et al., 2009; Prigge et al., 2020), we treated several tir1/afb-family multiply mutants with PLU. Higher-order mutants exhibited higher resistance to the PLU treatment, and PLU neither attenuated root growth nor induced callus formation in tir1 afb1 afb2 afb3 quadruple mutant (Figures 6C-E). These results showed that PLU requires TIR1/AFB family to induce the formation of pluripotent callus. Collectively, we concluded that PLU potentiates responsiveness to auxin via activation of expression of auxin receptor genes.

CIM, which has been used for artificial callus induction, requires externally supplemented auxin and cytokinin to induce pluripotency (Skoog and Miller, 1957; Ikeuchi et al., 2013; Shin and Seo, 2018). Although PLU does not require the external application of either auxin or cytokinin to initiate the formation of pluripotent callus, PLU potentiates responsiveness to endogenous auxin by inducing the expression of auxin receptors. However, only activation of auxin signaling is considered insufficient to induce pluripotency (Skoog and Miller, 1957; Ikeuchi et al., 2013; Shin and Seo, 2018). It was reported that, although TIR1 overexpression enhances the sensitivity to auxin (Chen et al., 2011; Windels et al., 2014), overexpression of TIR1 or AFBs do not cause callus formation (Chen et al., 2011; Ren et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2015; El-Sharkawy et al., 2016; He et al., 2018; Garrido-Vargas et al., 2020). It is likely that, though auxin responses are required for callus induction, the TIR1 overexpression alone is insufficient to cause callus induction. Like cytokinin in the case of CIM, another additional factor(s) would be required to effectively induce callus formation. In this regard, the sugar-type preference of PLU for the pluripotency induction may be noteworthy. It is known that the glucose/sucrose ratio affects growth and development and that sugar signaling is complexly intertwined with cytokinin signaling (Wang et al., 2021; Meng et al., 2022). Exploring a mechanism underlying the sugar-type preference of PLU may lead to understanding why PLU can effectively induce pluripotency without the external application of cytokinin.

Cis-element analysis and following experiments revealed the overrepresentation of the HSE motif among PLU-upregulated genes and the requirement of HSP90 for PLU-initiated callus formation. A variety of internal and external stresses, as well as heat stress, modulate HSP90 activity (Sangster and Queitsch, 2005; Kadota and Shirasu, 2012; Di Donato and Geisler, 2019). HSP90 proteins, which pre-exist in cells, initiate downstream events in response to stresses. Because our RNA-seq data indicates no rapid change in HSP90 expression after PLU treatment, PLU likely modulates the activity of pre-existing HSP90 proteins. The unidentified direct target of PLU may be a factor acting in the machinery that modulates HSP90 activity in response to specific stress. Because HSP90 functions by forming context-specific protein complexes (Sangster and Queitsch, 2005; Kadota and Shirasu, 2012; Di Donato and Geisler, 2019; Toribio et al., 2020), it would be interesting to investigate whether PLU influences HSP90-including protein complexes and what context-specific complex PLU modulates.

PLU induces expression of TIR1/AFB-family genes in an HSP90-dependent manner. It was reported that heat stress enhances the TIR1 activity by stabilizing TIR1 proteins via HSP90 (Wang et al., 2016). However, despite the overrepresentation of the HSE motif among PLU-upregulated genes, PLU treatment did not induce apparent heat responses such as enhanced elongation of hypocotyls. Because a variety of stresses such as osmotic stress, drought, and pathogens can affect the transcription of TIR1/AFB-family genes (Navarro et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2011; Kalve et al., 2020), PLU may modulate some stress-related pathway other than heat. Combined with the report that HSP90 stabilizes TIR1 proteins upon heat stress (Wang et al., 2016), PLU may synergistically activate TIR1 in an HSP90-dependent manner by both the transcriptional level and the protein stability level.

Other possible mechanisms for the mode of action of PLU may include the modulation of auxin transport. True leaves of PLU-treated seedlings exhibited a venation pattern similar to those with defects in auxin transport (Thomson et al., 1973; Sieburth, 1999). Unlike IAA that can directly and globally affect downstream genes and, therefore, can rapidly activate DR5 responses, PLU may modulate a mechanism that can affect the expression of only a part of auxin-regulated genes (Figure S3). Auxin transport could be involved in this partial effect of PLU on auxin-regulated genes.

Although artificial induction of callus by CIM containing auxin and cytokinin is a general procedure for plant transformation and some agricultural applications, the production of pluripotent callus is still challenging for many plant species. Another small compound, fipexide (FPX), was also reported to promote callus formation and shoot regeneration in plants (Nakano et al., 2018), and the mode of action of FPX seems different from that of PLU or CIM because FPX forms pluripotent tissues without vasculatures, while PLU and CIM induce those with vasculatures (Figure 1F) (Nakano et al., 2018). Further exploring details of pluripotency-inducing mechanisms activated by these novel compounds, including analysis of which parts or functional groups in their chemical structures are critical for their activities, may lead to developing alternative pluripotency induction methodologies that complement the conventional methodology. Because these compounds contain an amide linkage, which could be cleaved in plants (Savaldi-Goldstein et al., 2008), they may become active forms by being cleaved in plants. It would be noteworthy that their possible chemical structures after the presumable cleavage of the amide linkage can commonly retain the same moiety as the side chain of 2,4-D, a synthetic auxin. In this scenario, the identification of actual in planta structures of such auxin-like forms after the cleavage may provide further insights into the understanding of the mode of action of these compounds and facilitate the applied usage of these compounds.

The datasets presented in this study are deposited in the DDBJ repository, accession number DRA013685.

NU conceived the project; YN and NU designed experiments; YN, YK, HE, AH, RI, MK, YT, HS, SK, MN, YT, and NU performed research and analyzed data; MM, RK, RI, AS, KI, SH, KT, and NU developed and provided materials; YN and NU wrote the manuscript; YN, HS, SK, SH, KT and NU edited the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by MEXT/JSPS KAKENHI (Grant numbers JP17H06476, JP20K21422, JP21H02513, JP20H04883, JP20H05409, JP20H05905, JP20H05912, JP21H02503 and JP22K15140), the Mitsubishi Foundation, and the Asahi Glass Foundation. This work is also partially supported by Nagoya University Research Fund.

We thank Hidehiro Fukaki, Koji Takahashi, Michael Prigge, Mark Estelle, and ABRC for providing Arabidopsis seeds and materials. We also thank Hiroe Kato and Misato Ohtani for the support of chemical screening and sharing the protocol of callus induction by CIM, respectively.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2023.1099587/full#supplementary-material

Aida, M., Beis, D., Heidstra, R., Willemsen, V., Blilou, I., Galinha, C., et al. (2004). The PLETHORA genes mediate patterning of the arabidopsis root stem cell niche. Cell 119, 109–120. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.018

Atta, R., Laurens, L., Boucheron-Dubuisson, E., Guivarc'h, A., Carnero, E., Giraudat-Pautot, V., et al. (2009). Pluripotency of arabidopsis xylem pericycle underlies shoot regeneration from root and hypocotyl explants grown in vitro. Plant J. 57, 626–644. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03715.x

Baima, S., Nobili, F., Sessa, G., Lucchetti, S., Ruberti, I., Morelli, G. (1995). The expression of the athb-8 homeobox gene is restricted to provascular cells in arabidopsis thaliana. Development 121, 4171–4182. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.12.4171

Chen, Z. H., Bao, M. L., Sun, Y. Z., Yang, Y. J., Xu, X. H., Wang, J. H., et al. (2011). Regulation of auxin response by miR393-targeted transport inhibitor response protein 1 is involved in normal development in arabidopsis. Plant Mol. Biol. 77, 619–629. doi: 10.1007/s11103-011-9838-1

Chen, Z., Hu, L., Han, N., Hu, J., Yang, Y., Xiang, T., et al. (2015). Overexpression of a miR393-resistant form of transport inhibitor response protein 1 (mTIR1) enhances salt tolerance by increased osmoregulation and na+ exclusion in arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 56, 73–83. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcu149

Crooks, G. E., Hon, G., Chandonia, J. M., Brenner, S. E. (2004). WebLogo: A sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 14, 1188–1190. doi: 10.1101/gr.849004

De Smet, I., Tetsumura, T., De Rybel, B., Frei Dit Frey, N., Laplaze, L., Casimiro, I., et al. (2007). Auxin-dependent regulation of lateral root positioning in the basal meristem of arabidopsis. Development 134, 681–690. doi: 10.1242/dev.02753

Dharmasiri, N., Dharmasiri, S., Estelle, M. (2005a). The f-box protein TIR1 is an auxin receptor. Nature 435, 441–445. doi: 10.1038/nature03543

Dharmasiri, N., Dharmasiri, S., Weijers, D., Lechner, E., Yamada, M., Hobbie, L., et al. (2005b). Plant development is regulated by a family of auxin receptor f box proteins. Dev. Cell 9, 109–119. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.05.014

Di Donato, M., Geisler, M. (2019). HSP90 and co-chaperones: A multitaskers' view on plant hormone biology. FEBS Lett. 593, 1415–1430. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.13499

Di Laurenzio, L., Wysocka-Diller, J., Malamy, J. E., Pysh, L., Helariutta, Y., Freshour, G., et al. (1996). The SCARECROW gene regulates an asymmetric cell division that is essential for generating the radial organization of the arabidopsis root. Cell 86, 423–433. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80115-4

El-Sharkawy, I., Sherif, S., El Kayal, W., Jones, B., Li, Z., Sullivan, A. J., et al. (2016). Overexpression of plum auxin receptor PslTIR1 in tomato alters plant growth, fruit development and fruit shelf-life characteristics. BMC Plant Biol. 16, 56. doi: 10.1186/s12870-016-0746-z

Eshed Williams, L. (2021). Genetics of shoot meristem and shoot regeneration. Annu. Rev. Genet. 55, 661–681. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-071719-020439

Fukaki, H., Nakao, Y., Okushima, Y., Theologis, A., Tasaka, M. (2005). Tissue-specific expression of stabilized SOLITARY-ROOT/IAA14 alters lateral root development in arabidopsis. Plant J. 44, 382–395. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02537.x

Gaillochet, C., Lohmann, J. U. (2015). The never-ending story: From pluripotency to plant developmental plasticity. Development 142, 2237–2249. doi: 10.1242/dev.117614

Garrido-Vargas, F., Godoy, T., Tejos, R., O'brien, J. A. (2020). Overexpression of the auxin receptor AFB3 in arabidopsis results in salt stress resistance and the modulation of NAC4 and SZF1. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 9528. doi: 10.3390/ijms21249528

Goh, T., Joi, S., Mimura, T., Fukaki, H. (2012). The establishment of asymmetry in arabidopsis lateral root founder cells is regulated by LBD16/ASL18 and related LBD/ASL proteins. Development 139, 883–893. doi: 10.1242/dev.071928

Gordon, S. P., Heisler, M. G., Reddy, G. V., Ohno, C., Das, P., Meyerowitz, E. M. (2007). Pattern formation during de novo assembly of the arabidopsis shoot meristem. Development 134, 3539–3548. doi: 10.1242/dev.010298

Guhathakurta, D., Palomar, L., Stormo, G. D., Tedesco, P., Johnson, T. E., Walker, D. W., et al. (2002). Identification of a novel cis-regulatory element involved in the heat shock response in caenorhabditis elegans using microarray gene expression and computational methods. Genome Res. 12, 701–712.

Guo, M., Liu, J. H., Ma, X., Luo, D. X., Gong, Z. H., Lu, M. H. (2016). The plant heat stress transcription factors (HSFs): Structure, regulation, and function in response to abiotic stresses. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 114. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00114

Haecker, A., Gross-Hardt, R., Geiges, B., Sarkar, A., Breuninger, H., Herrmann, M., et al. (2004). Expression dynamics of WOX genes mark cell fate decisions during early embryonic patterning in arabidopsis thaliana. Development 131, 657–668. doi: 10.1242/dev.00963

He, Q., Yang, L., Hu, W., Zhang, J., Xing, Y. (2018). Overexpression of an auxin receptor OsAFB6 significantly enhanced grain yield by increasing cytokinin and decreasing auxin concentrations in rice panicle. Sci. Rep. 8, 14051. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-32450-x

Ikeuchi, M., Favero, D. S., Sakamoto, Y., Iwase, A., Coleman, D., Rymen, B., et al. (2019). Molecular mechanisms of plant regeneration. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 70, 377–406. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050718-100434

Ikeuchi, M., Ogawa, Y., Iwase, A., Sugimoto, K. (2016). Plant regeneration: Cellular origins and molecular mechanisms. Development 143, 1442–1451. doi: 10.1242/dev.134668

Ikeuchi, M., Sugimoto, K., Iwase, A. (2013). Plant callus: Mechanisms of induction and repression. Plant Cell 25, 3159–3173. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.116053

Jacob, P., Hirt, H., Bendahmane, A. (2017). The heat-shock protein/chaperone network and multiple stress resistance. Plant Biotechnol. J. 15, 405–414. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12659

Kadota, Y., Shirasu, K. (2012). The HSP90 complex of plants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1823, 689–697. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.09.016

Kakei, Y., Yamazaki, C., Suzuki, M., Nakamura, A., Sato, A., Ishida, Y., et al. (2015). Small-molecule auxin inhibitors that target YUCCA are powerful tools for studying auxin function. Plant J. 84, 827–837. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13032

Kalve, S., Sizani, B. L., Markakis, M. N., Helsmoortel, C., Vandeweyer, G., Laukens, K., et al. (2020). Osmotic stress inhibits leaf growth of arabidopsis thaliana by enhancing ARF-mediated auxin responses. New Phytol. 226, 1766–1780. doi: 10.1111/nph.16490

Kareem, A., Durgaprasad, K., Sugimoto, K., Du, Y., Pulianmackal, A. J., Trivedi, Z. B., et al. (2015). PLETHORA genes control regeneration by a two-step mechanism. Curr. Biol. 25, 1017–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.02.022

Kepinski, S., Leyser, O. (2005). The arabidopsis f-box protein TIR1 is an auxin receptor. Nature 435, 446–451. doi: 10.1038/nature03542

Kim, J. Y., Yang, W., Forner, J., Lohmann, J. U., Noh, B., Noh, Y. S. (2018). Epigenetic reprogramming by histone acetyltransferase HAG1/AtGCN5 is required for pluripotency acquisition in arabidopsis. EMBO J. 37, e98726. doi: 10.15252/embj.201798726

Kojima, M., Kamada-Nobusada, T., Komatsu, H., Takei, K., Kuroha, T., Mizutani, M., et al. (2009). Highly sensitive and high-throughput analysis of plant hormones using MS-probe modification and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry: an application for hormone profiling in oryza sativa. Plant Cell Physiol. 50, 1201–1214. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcp057

Kramer, E. M., Ackelsberg, E. M. (2015). Auxin metabolism rates and implications for plant development. Front. Plant Sci. 6, 150. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00150

Krishna, P., Gloor, G. (2001). The Hsp90 family of proteins in arabidopsis thaliana. Cell Stress Chaperones 6, 238–246. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(2001)006<0238:THFOPI>2.0.CO;2

Kurihara, D., Mizuta, Y., Sato, Y., Higashiyama, T. (2015). ClearSee: A rapid optical clearing reagent for whole-plant fluorescence imaging. Development 142, 4168–4179. doi: 10.1242/dev.127613

Laplaze, L., Parizot, B., Baker, A., Ricaud, L., Martiniere, A., Auguy, F., et al. (2005). GAL4-GFP enhancer trap lines for genetic manipulation of lateral root development in arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Bot. 56, 2433–2442. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eri236

Manuel, M., Rallu, M., Loones, M. T., Zimarino, V., Mezger, V., Morange, M. (2002). Determination of the consensus binding sequence for the purified embryonic heat shock factor 2. Eur. J. Biochem. 269, 2527–2537. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.02917.x

Marques-Bueno, M. D. M., Morao, A. K., Cayrel, A., Platre, M. P., Barberon, M., Caillieux, E., et al. (2016). A versatile multisite gateway-compatible promoter and transgenic line collection for cell type-specific functional genomics in arabidopsis. Plant J. 85, 320–333. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13099

Meng, Y., Zhang, N., Li, J., Shen, X., Sheen, J., Xiong, Y. (2022). TOR kinase, a GPS in the complex nutrient and hormonal signaling networks to guide plant growth and development. J. Exp. Bot. 73, 7041–7054. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erac282

Nakano, T., Tanaka, S., Ohtani, M., Yamagami, A., Takeno, S., Hara, N., et al. (2018). FPX is a novel chemical inducer that promotes callus formation and shoot regeneration in plants. Plant Cell Physiol. 59, 1555–1567. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcy139

Navarro, L., Dunoyer, P., Jay, F., Arnold, B., Dharmasiri, N., Estelle, M., et al. (2006). A plant miRNA contributes to antibacterial resistance by repressing auxin signaling. Science 312, 436–439. doi: 10.1126/science.1126088

Nishimura, T., Hayashi, K., Suzuki, H., Gyohda, A., Takaoka, C., Sakaguchi, Y., et al. (2014). Yucasin is a potent inhibitor of YUCCA, a key enzyme in auxin biosynthesis. Plant J. 77, 352–366. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12399

Okushima, Y., Fukaki, H., Onoda, M., Theologis, A., Tasaka, M. (2007). ARF7 and ARF19 regulate lateral root formation via direct activation of LBD/ASL genes in arabidopsis. Plant Cell 19, 118–130. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.047761

Paponov, I. A., Paponov, M., Teale, W., Menges, M., Chakrabortee, S., Murray, J. A., et al. (2008). Comprehensive transcriptome analysis of auxin responses in arabidopsis. Mol. Plant 1, 321–337. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssm021

Parry, G., Calderon-Villalobos, L. I., Prigge, M., Peret, B., Dharmasiri, S., Itoh, H., et al. (2009). Complex regulation of the TIR1/AFB family of auxin receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 22540–22545. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911967106

Pearl, L. H., Prodromou, C. (2006). Structure and mechanism of the Hsp90 molecular chaperone machinery. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 75, 271–294. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142738

Peret, B., De Rybel, B., Casimiro, I., Benkova, E., Swarup, R., Laplaze, L., et al. (2009). Arabidopsis lateral root development: An emerging story. Trends Plant Sci. 14, 399–408. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2009.05.002

Perez-Garcia, P., Moreno-Risueno, M. A. (2018). Stem cells and plant regeneration. Dev. Biol. 442, 3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2018.06.021

Prigge, M. J., Platre, M., Kadakia, N., Zhang, Y., Greenham, K., Szutu, W., et al. (2020). Genetic analysis of the arabidopsis TIR1/AFB auxin receptors reveals both overlapping and specialized functions. Elife 9. doi: 10.7554/eLife.54740.sa2

Queitsch, C., Sangster, T. A., Lindquist, S. (2002). Hsp90 as a capacitor of phenotypic variation. Nature 417, 618–624. doi: 10.1038/nature749

Ren, Z., Li, Z., Miao, Q., Yang, Y., Deng, W., Hao, Y. (2011). The auxin receptor homologue in solanum lycopersicum stimulates tomato fruit set and leaf morphogenesis. J. Exp. Bot. 62, 2815–2826. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq455

Robinson, M. D., Mccarthy, D. J., Smyth, G. K. (2010). edgeR: a bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26, 139–140. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616

Sangster, T. A., Queitsch, C. (2005). The HSP90 chaperone complex, an emerging force in plant development and phenotypic plasticity. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 8, 86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2004.11.012

Savaldi-Goldstein, S., Baiga, T. J., Pojer, F., Dabi, T., Butterfield, C., Parry, G., et al. (2008). New auxin analogs with growth-promoting effects in intact plants reveal a chemical strategy to improve hormone delivery. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 15190–15195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806324105

Scharf, K. D., Berberich, T., Ebersberger, I., Nover, L. (2012). The plant heat stress transcription factor (Hsf) family: Structure, function and evolution. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1819, 104–119. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2011.10.002

Shin, J., Bae, S., Seo, P. J. (2020). De novo shoot organogenesis during plant regeneration. J. Exp. Bot. 71, 63–72. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erz395

Shin, J., Seo, P. J. (2018). Varying auxin levels induce distinct pluripotent states in callus cells. Front. Plant Sci. 9, 1653. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01653

Shinozaki, Y., Hao, S., Kojima, M., Sakakibara, H., Ozeki-Iida, Y., Zheng, Y., et al. (2015). Ethylene suppresses tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) fruit set through modification of gibberellin metabolism. Plant J. 83, 237–251. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12882

Sieburth, L. E. (1999). Auxin is required for leaf vein pattern in arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 121, 1179–1190. doi: 10.1104/pp.121.4.1179

Skoog, F., Miller, C. O. (1957). Chemical regulation of growth and organ formation in plant tissues cultured in vitro. Symp Soc. Exp. Biol. 11, 118–130.

Staswick, P. E., Serban, B., Rowe, M., Tiryaki, I., Maldonado, M. T., Maldonado, M. C., et al. (2005). Characterization of an arabidopsis enzyme family that conjugates amino acids to indole-3-acetic acid. Plant Cell 17, 616–627. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.026690

Stebbins, C. E., Russo, A. A., Schneider, C., Rosen, N., Hartl, F. U., Pavletich, N. P. (1997). Crystal structure of an Hsp90-geldanamycin complex: targeting of a protein chaperone by an antitumor agent. Cell 89, 239–250. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80203-2

Sugimoto, K., Jiao, Y., Meyerowitz, E. M. (2010). Arabidopsis regeneration from multiple tissues occurs via a root development pathway. Dev. Cell 18, 463–471. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.02.004

Tan, X., Calderon-Villalobos, L. I., Sharon, M., Zheng, C., Robinson, C. V., Estelle, M., et al. (2007). Mechanism of auxin perception by the TIR1 ubiquitin ligase. Nature 446, 640–645. doi: 10.1038/nature05731

Thomson, K. S., Hertel, R., Muller, S., Tavares, J. E. (1973). 1-n-naphthylphthalamic acid and 2,3,5-triiodobenzoic acid : In-vitro binding to particulate cell fractions and action on auxin transport in corn coleoptiles. Planta 109, 337–352. doi: 10.1007/BF00387102

Toribio, R., Mangano, S., Fernandez-Bautista, N., Munoz, A., Castellano, M. M. (2020). HOP, a Co-chaperone involved in response to stress in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 11, 591940. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.591940

Uchida, N., Takahashi, K., Iwasaki, R., Yamada, R., Yoshimura, M., Endo, T. A., et al. (2018). Chemical hijacking of auxin signaling with an engineered auxin-TIR1 pair. Nat. Chem. Biol. 14, 299–305. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2555

Uchida, N., Townsley, B., Chung, K. H., Sinha, N. (2007). Regulation of SHOOT MERISTEMLESS genes via an upstream-conserved noncoding sequence coordinates leaf development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 15953–15958. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707577104

Ulmasov, T., Murfett, J., Hagen, G., Guilfoyle, T. J. (1997). Aux/IAA proteins repress expression of reporter genes containing natural and highly active synthetic auxin response elements. Plant Cell 9, 1963–1971.

Vanneste, S., De Rybel, B., Beemster, G. T., Ljung, K., De Smet, I., Van Isterdael, G., et al. (2005). Cell cycle progression in the pericycle is not sufficient for SOLITARY ROOT/IAA14-mediated lateral root initiation in arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 17, 3035–3050. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.035493

Wang, M., Le Gourrierec, J., Jiao, F., Demotes-Mainard, S., Perez-Garcia, M. D., Oge, L., et al. (2021). Convergence and divergence of sugar and cytokinin signaling in plant development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 1282. doi: 10.3390/ijms22031282

Wang, R., Zhang, Y., Kieffer, M., Yu, H., Kepinski, S., Estelle, M. (2016). HSP90 regulates temperature-dependent seedling growth in arabidopsis by stabilizing the auxin co-receptor f-box protein TIR1. Nat. Commun. 7, 10269. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10269

Windels, D., Bielewicz, D., Ebneter, M., Jarmolowski, A., Szweykowska-Kulinska, Z., Vazquez, F. (2014). miR393 is required for production of proper auxin signalling outputs. PloS One 9, e95972. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095972

Yamamoto, Y. Y., Yoshioka, Y., Hyakumachi, M., Maruyama, K., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K., Tokizawa, M., et al. (2011). Prediction of transcriptional regulatory elements for plant hormone responses based on microarray data. BMC Plant Biol. 11, 39. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-11-39

Keywords: Arabidopsis thaliana, auxin, callus, HSP90, pluripotency, small compound

Citation: Nakashima Y, Kobayashi Y, Murao M, Kato R, Endo H, Higo A, Iwasaki R, Kojima M, Takebayashi Y, Sato A, Nomoto M, Sakakibara H, Tada Y, Itami K, Kimura S, Hagihara S, Torii KU and Uchida N (2023) Identification of a pluripotency-inducing small compound, PLU, that induces callus formation via Heat Shock Protein 90-mediated activation of auxin signaling. Front. Plant Sci. 14:1099587. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2023.1099587

Received: 16 November 2022; Accepted: 13 January 2023;

Published: 08 March 2023.

Edited by:

Nobutoshi Yamaguchi, Nara Institute of Science and Technology (NAIST), JapanCopyright © 2023 Nakashima, Kobayashi, Murao, Kato, Endo, Higo, Iwasaki, Kojima, Takebayashi, Sato, Nomoto, Sakakibara, Tada, Itami, Kimura, Hagihara, Torii and Uchida. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Naoyuki Uchida, dWNoaW5hb0BnZW5lLm5hZ295YS11LmFjLmpw

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.