- 1College of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture, Southwest University, Chongqing, China

- 2Chongqing Key Laboratory of Olericulture, Chongqing, China

Flowering is crucial for sexual reproductive success in angiosperms. The core regulatory factors, such as FT, FUL, and SOC1, are responsible for promoting flowering. BRANCHED 1 (BRC1) is a TCP transcription factor gene that plays an important role in the regulation of branching and flowering in diverse plant species. However, the functions of BjuBRC1 in Brassica juncea are largely unknown. In this study, four homologs of BjuBRC1 were identified and the mechanism by which BjuBRC1 may function in the regulation of flowering time was investigated. Amino acid sequence analysis showed that BjuBRC1 contained a conserved TCP domain with two nuclear localization signals. A subcellular localization assay verified the nuclear localization of BjuBRC1. Expression analysis revealed that BjuBRC1-1 was induced by short days and was expressed abundantly in the leaf, flower, and floral bud but not in the root and stem in B. juncea. Overexpression of BjuBRC1-1 in the Arabidopsis brc1 mutant showed that BjuBRC1-1 delayed flowering time. Bimolecular fluorescent complementary and luciferase complementation assays showed that four BjuBRC1 proteins could interact with BjuFT in vivo. Notably, BjuBRC1 proteins formed heterodimers in vivo that may impact on their function of negatively regulating flowering time. Yeast one-hybrid, dual-luciferase reporter, and luciferase activity assays showed that BjuBRC1-1 could directly bind to the promoter of BjuFUL, but not BjuFT or BjuSOC1, to repress its expression. These results were supported by the reduced expression of AtFUL in transgenic Arabidopsis overexpressing BjuBRC1-1. Taken together, the results indicate that BjuBRC1 genes likely have a conserved function in the negative regulation of flowering in B. juncea.

Introduction

Flowering represents a crucial developmental transition from vegetative to reproductive growth, which is crucial for sexual reproductive success in angiosperms. The molecular mechanism and genetic basis of flowering have been characterized in detail in Arabidopsis thaliana (Andrés and Coupland, 2012; Dally et al., 2014; Blümel et al., 2015). Flowering is induced by complex exogenous and endogenous cues, such as photoperiod and hereditary factors. Six major pathways, comprising the autonomous, photoperiod, vernalization, aging, thermosensory, and gibberellin (GA) signaling pathways (Simpson and Dean, 2002; Blázquez et al., 2003; Halliday et al., 2003; Amasino, 2004; Han et al., 2008; Kumar et al., 2012; Fornara et al., 2010), regulate flowering by influencing the floral integrator genes FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT), SUPPRESSOR OF OVEREXPRESSION OF CONSTANS 1 (SOC1), and LEAFY (LFY).

The FT protein is a phosphatidylethanolamine-binding protein (PEBP). The PEBP family consists of three phylogenetically distinct groups: FT-like proteins, TERMINAL FLOWER1-like (TFL1), and MOTHER OF FT AND TFL1-like (MFT) proteins (Pin and Nilsson, 2012; Wickland and Hanzawa, 2015). FT is transported from leaves to the shoot apex to induce flowering by forming a protein complex with the bZIP transcription factor FLOWERING LOCUS D (Wigge et al., 2005; Corbesier et al., 2007; Tamaki et al., 2007; Wickland and Hanzawa, 2015; Zhang et al., 2016) and is regulated under long days (LD) by transcription factors such as CONSTANS (CO) and TEMPRANILLO (TEM) (Castillejo and Pelaz, 2008). Furthermore, TFL1 and FT compete with FD and thus affect flowering (Zhu et al., 2020). Studies of tomato and rice indicate the involvement of 14-3-3 proteins in the protein interactions of FT orthologs with FD orthologs (Pnueli et al., 2001; Taoka et al., 2011). The MADS-box gene FRUITFULL (FUL) plays an essential role in regulating flowering time, differentiation of floral meristems, and carpel and fruit development in Arabidopsis (Ferrándiz et al., 2000; Melzer et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2009). In addition, FUL coordinates with the aging pathway and gibberellin signaling pathway to accelerate flowering (Yamaguchi et al., 2009; Li et al., 2016).

The TCP transcription factor family was first described in 1999. The conserved domain consists of a 59-amino acid basic helix–loop–helix (bHLH) motif that allows DNA binding and protein–protein interactions. The first characterized members were TEOSINTE BRANCHED 1 (TB1), CYCLOIDEA (CYC), and PROLIFERATING CELL NUCLEAR ANTIGEN FACTOR 1 and 2 (PCFs); hence, it was termed the TCP family (Cubas et al., 1999; Kosugi et al., 2015; Luo et al., 1996; Doebley et al., 1997). TCP genes are classified into two classes based on differences within the TCP domain: class I (Kosugi and Ohashi, 2002), also termed the PCF class (Cubas, 2002) or TCP-P class (Navaud et al., 2007), and class II, also known as the TCP-C class. Class II can be further subdivided into two clades based on differences in the TCP domain: the CIN clade, which is involved in lateral organ development, and the CYC/TB1 clade (or ECE clade) (Howarth and Donoghue, 2006), which is mainly involved in the development of axillary meristems giving rise to either flowers or lateral shoots (Cubas and Martı, 2009; Nicolas and Cubas, 2015; Li et al., 2019; Li et al., 2021).

BRANCHED 1 (BRC1 or TCP18) encodes a member of the TCP family and is an integrator of multiple internal and external signals that act in the axillary buds to suppress shoot branching. For example, in Arabidopsis, BRC1 is expressed in developing buds to arrest bud development, and downregulation of BRC1 leads to branch outgrowth (Aguilar-Martínez et al., 2007; Finlayson, 2007). In tomato, two BRC1-like paralogs, SlBRC1a and SlBRC1b, are expressed in arrested axillary buds, with SlBRC1a transcribed at much lower levels than SlBRC1b (Martín-Trillo et al., 2011). Some researchers have reported that BRC1 plays a role in controlling branching in crop brassicas such as Brassica napus (AACC, 2n = 38) (Li et al., 2020) and Brassica juncea (AABB, 2n = 36) (Muntha et al., 2019), indicating that BRC1 may have conserved functions in regulating the growth and development of axillary buds in crop brassicas.Many genes are involved in BRC1-mediated axillary bud growth (Liu et al., 2017; Shen et al., 2019; Xie et al., 2020), indicating that BRC1 as integrator in controlling shoot branching is regulated by multiple transcription factors.

BRC1 is also reported to participate in the regulation of flowering time. For example, BRC1 can interact with FT and TSF (but not with TFL1) and modulates florigen activity in the axillary buds to prevent premature floral transition of the apical meristems (Niwa et al., 2013). Certain class II TCP proteins containing BRC1 can interact with FD, raising the possibility that they may be incorporated into the FT–FD module to control photoperiodic flowering (Li et al., 2019). In hybrid aspen, BRC1 physically interacts with FT2, further reinforcing the effect of a short photoperiod and triggering growth cessation by antagonizing FT action (Maurya et al., 2020). The allotetraploid Brassica juncea, which originated from Brassica rapa (AA, 2n = 20) and Brassica nigra (BB, 2n = 16) by natural interspecific hybridization, is an economically important crop plant in China. Five BRC1 homologous genes with a conserved TCP domain are present in the genome of B. juncea based on information in the BRAD database; two homologs (BjuVA03G39990 and BjuVA01G37280) originated from B. rapa, whereas the other three homologs (BjuVB07G28850, BjuVB01G36290, and BjuVB07G09230) originated from B. nigra. It is not clear whether the BjuBRC1 homologs function in the regulation of flowering in B. juncea.

In this study, we isolated four BjuBRC1 genes from B. juncea and selected one (BjuBRC1-1, BjuVB07G09230) for study in detail. In B. juncea, BjuBRC1-1 expression was induced by short days (SD), and its heterologous overexpression in Arabidopsis delayed flowering time under LD. Four BjuBRC1 proteins were capable of interaction with BjuFT, whereas only BjuBRC1-1 could directly bind to the promoter of BjuFUL to repress its expression. These mechanisms indicated that BjuBRC1-1 may function in the regulation of flowering.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

The Brassica juncea plant materials used in this study were the homozygous line mustard “J92” which was provided by our laboratory. B. juncea seedlings were grown in the artificial climate chamber under long-day conditions (22°C 16-h light/20°C 8-h dark).

Wild-type Arabidopsis (Columbia ecotype) and its brc1 mutant (T-DNA insert lines; results of positive detection by PCR amplification are shown in Supplementary Figure 1) used in this study were obtained from ABRC (https://www.arashare.cn/index/Product/index). After surface sterilization, all Arabidopsis seeds were sown on half-strength MS media plates supplemented with 3% sucrose to allow seed germination and seedling growth, and the plates were placed in the artificial climate chamber (22°C 16-h light/20°C 8-h dark). Then, Arabidopsis were transferred from plates to soil after about 5 days for growth.

The seeds of Nicotiana benthamiana were directly sown into the soil and were grown in the chamber for 1 month (25°C, 16-h light/8-h dark).

Multiple-sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis

The coding sequence of Arabidopsis thaliana AtBRC1 was downloaded from The Arabidopsis Information Resource (https://www.arabidopsis.org/) and was used as the query for a BLAST search of BRAD to obtain BRC1 sequences in Brassica species. The full-length amino acid sequences of BjuBRC1 proteins (BjuVA03G39990, BjuVA01G37280, BjuVB07G28850, BjuVB01G36290, and BjuVB07G09230) were downloaded from the Brassicaceae Database (BRAD, http://39.100.233.196/). In addition, all amino acid sequences for BRC1 proteins of other Brassica species were obtained from BRAD, comprising B. rapa (BraA01g035600.3.5C and BraA03g038870.3.5C), B. nigra (BniB035325, BniB039293, and BniB017427), B. oleracea (BolC1t04530H, BolC5t33435H, and BolC3t17248H), B. napus (BnaDarC03p49500.1, BnaDARA03p40710.1, BnaDARC05p47080.1, BnaDARA01p35910.1, and BnaDARC01p45680.1), and B. carinata (BcaC01g03693, BcaB04g18990, BcaB04g18989, BcaB06g25899, BcaC05g28604, and BcaC09g48810). A multiple-sequence alignment was generated with BioXM2.7 software. Phylogenetic analysis was performed with the neighbor-joining method with 1,000 bootstrap replicates using MEGA10.2.0. The phylogenetic tree for the BRC1 proteins was visualized and adjusted with EvolView (https://www.evolgenius.info/evolview/).

RNA extraction, reverse transcription, and gene cloning

Leaves and flowers were sampled from 5-week-old B. juncea plants and were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was extracted from the samples using the Biospin Plant Total RNA Extraction Kit (BioFlux) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Genomic DNA (gDNA) was digested in a 15-μl reaction mixture containing 3 μl 5× gDNA Digester Mix, 6 μl total RNA, and 6 μl RNase-free H2O, at 42°C for 2 min). The purified RNA was reverse-transcribed in a 20-μl reaction volume using the Hifair III 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis SuperMix Kit (YEASEN) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. The reverse transcription thermal profile comprised 25°C for 5 min, followed by 55°C for 15 min and 85°C for 5 min. All cDNA samples were diluted with ddH2O (1:4, v/v). The diluted cDNA was used directly for PCR amplification.

Based on the conserved sequences in the Brassica BRC1 genes, gene-specific primers (BRC1-F1, BRC1-F2, and BRC1-R1) were designed to amplify the BjuBRC1 genes in this study. Based on sequences of BjuBRC1-1, four truncated genes were subcloned by special primers. In addition, two BjuFT genes (BjuVB05G49700 and BjuVA07G33060) were cloned using the same procedure described above. All primers used are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Subcellular localization assay

The BjuBRC1-1 coding region without the stop codon (and two truncated sequences BjuBRC1-1-I and BjuBRC1-1-II, respectively) was subcloned into the pCAMBIA1300-GFP vector via double-enzyme digestion with XbaI and KpnI. The recombinant plasmid p35S::BjuBRC1-1-GFP and the empty vector pCAMBIA1300-GFP were transformed separately into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101. The leaves of 1-month-old Nicotiana benthamiana plants were infiltrated with A. tumefaciens cells harboring pCAMBIA1300-GFP, pCAMBIA1300-BjuBRC1-1-GFP, or the corresponding construct containing a truncated BjuBRC1-1 sequence. The N. benthamiana leaves infiltrated with A. tumefaciens were incubated in the dark for 1 day and then transferred to a growth chamber maintained at 25°C with a 16-h/8-h (light/dark) photoperiod for 24–48 h. The leaves were used for visualization of the GFP signal with a laser scanning confocal microscope (LSM78010800, ZEISS).

Expression analysis

Brassica juncea plants used for expression analysis were grown in an artificial climate chamber under LD (22°C 16-h light/20°C 8-h dark) or SD (22°C 8-h light/20°C 16-h dark). At least three leaf (stems, flowering buds, and flowerings) samples from each day-length treatment were collected for subsequent analysis. All Arabidopsis plants were grown in the artificial climate chamber under LD, and their 2-week-old leaves were sampled.

Total RNA extraction and reverse transcription were conducted as described under “RNA extraction, reverse transcription and gene cloning”. The cDNA was used either immediately in the following reaction or stored at −80°C until use. Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis was performed using the SYBR qPCR SuperMix Plus (Novoprotein Scientific) on a CFX96™ Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad). The primers used for qPCR analysis of BjuBRC1-1 (BRC1-qPCR-F and BRC1-qPCR-R) and AtFUL (FUL-qPCR-F and FUL-qPCR-R) are listed in Supplementary Table 1. The BjuACTIN2 and AtTUB2 genes were used for normalization of the B. juncea and Arabidopsis samples, respectively. Each qPCR analysis was performed in a volume of 20 μl containing 10 μl 2× NovoStart® SYBR qPCR SuperMix Plus, 1 μl cDNA, 2 μl of the primer pair, and 7 μl ddH2O. The qPCR protocol incorporated “two-step amplification” for greater specificity as follows: 95°C for 1 min, 95°C for 20 s, and 60°C for 1 min, conducted for a maximum of 40 cycles. The relative expression level was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). Each sample was quantified in triplicate with three biological replicates. GraphPad Prism 5 software was used to graphically visualize the results. The significance of differences among the data was analyzed using Student’s t-test with SPSS software (18.0). The primers used are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Overexpression vector construction and plant transformation

BjuBRC1-1 (full-length) was subcloned and inserted into the pCAMBIA1300 vector containing the HYG resistance gene under the control of the 35S promoter. The recombination plasmid was introduced into A. tumefaciens strain GV3101 using the freeze–thaw method and transformed into Arabidopsis by the floral dip method (Bent and Clough, 1998). First, hygromycin was used to screen positive transgenic plants, and then PCR amplification was performed to verify the presence of the transgene. Three T1 transgenic Arabidopsis lines and their T3 progeny were subjected to qPCR for gene expression analysis.

DNA extraction and promoter cloning

The gDNA used for cloning of promoters was extracted using the Plant Genomic DNA Kit (TIANGEN) from young leaves of B. juncea following the manufacturer’s instructions. The gDNA product was stored at −80°C until use. The primers used for PCR amplification of the promoter region (the 1–2-kb region upstream of the start codon “ATG”) were designed based on the reference sequences (ProBjuFUL, BjuVA03G46090, 1,200 bp; ProBjuFT, BjuVB05G49700, 2,000 bp; and ProBjuSOC1, BjuVB08G24640, 800 bp) accessed from BRAD. All primers used are listed in Supplementary Table 1. Moreover, ProBjuSOC1 (pAbAi-ProBjuSOC1 vector) was provided by our laboratory.

Yeast two-hybrid assay

To detect protein–protein interactions using a yeast two-hybrid system, four BjuBRC1 homologous genes and BjuFT were inserted into the pGADT7 and pGBDT7 vectors, respectively. The recombinant plasmids pGBDT7-BjuBRC1s and pGBDT7-BjuFT were separately transformed into yeast strain Y2H Gold, whereas the pGADT7-BjuBRC1s and pGADT7-BjuFT plasmids were transformed into yeast strain Y187. Each prey (pGADT7) yeast strain was fused with the bait (pGBDT7) yeast strain with 2× YPDA liquid medium, and the recombined strains were cultured on DDO (SD/−Leu/−Trp) plates for 3 days at 30°C. Three independent colonies on the DDO plates were chosen to detect the interactions on QDO (SD/−Leu/−Trp/−Ade/−His) plates supplemented with X-α-gal (40 µg/ml) and aureobasidin A (AbA; 0.3 µg/ml).

Bimolecular fluorescent complimentary assays

The coding sequences of four BjuBRC1 genes and BjuFT were subcloned into the pVYCE and pVYNE vectors with the specific primers, respectively. Agrobacterium solutions containing pVYNE and pVYNE–BjuBRC1s were respectively mixed with the same volumes of Agrobacterium solutions containing pVYCE–BjuFT. Similarly, different combinations were held to detect the interactions among four BjuBRC1 proteins. The following procedures were similar to those used in the above subcellular localization experiment, and the fluorescent was detected by LSCM.

Luciferase complementation assay

The full-length BjuBRC1-1 and BjuFT were separately cloned into the pCAMBIA1300-CLuc (pC-C) and pCAMBIA1300-NLuc (pC-N) vectors, respectively (Zhou et al., 2018). Agrobacterium suspensions harboring pC-C and pC-C–BjuBRC1-1 were respectively mixed with the same volumes of Agrobacterium suspensions harboring pC-N–BjuFT.

Before bacterial infiltration, healthy and vigorous N. benthamiana plants were selected and placed under light for more than 1 h to ensure that most stomata were open and suitable for agroinfiltration. Small leaves were not suitable for agroinfiltration. The negative controls and tested protein pairs (pC-C–BjuBRC1 and pC-N–BjuFT) were infiltrated into the same leaf to avoid false positives and negatives caused by differences in physiological conditions between leaves. The infiltrated plants were incubated in a greenhouse for 40–48 h before measurement of luminescence. Then, a 1-mM D-luciferin solution was sprayed onto the leaves of N. benthamiana, ensuring that the leaves were completely wet, and then the plant was placed in the dark for 5–8 min to allow the chlorophyll luminescence to decay. Luminescence images were captured using a IVIS Imaging System.

Yeast one-hybrid assay

Four BjuBRC1 genes (and four truncated BjuBRC1-1) were respectively inserted into the pGADT7 vector by double-enzyme digestion with NdeI and EcoR I. The promoters of BjuFUL, BjuFT, and BjuSOC1 were cloned from leaves of B. juncea ‘J92’ and then recombined separately into the pAbAi vector. Using the Matchmaker Gold Yeast One-Hybrid Library Screening System (TaKaRa), the linearized plasmids pAbAi-ProBjuFUL, pAbAi-ProBjuFT, and pAbAi-ProBjuSOC1 were introduced into the yeast strain Y1H Gold and cultured on SD/−Ura agar plates. The minimum concentration of AbA (0–800 ng/ml) that inhibited yeast growth was screened on SD/−Ura/AbA plates. Subsequently, the pGADT7-BjuBRC1 plasmids were transformed into yeast strain Y1H Gold harboring pAbAi-ProBjuFT, pAbAi-ProBjuFUL, or pAbAi-ProBjuSOC1. The yeast strains were successively plated on SD/−Leu and SD/−Leu/AbA media. The growth of the yeast strains at 30°C was assessed for testing the protein–DNA interactions.

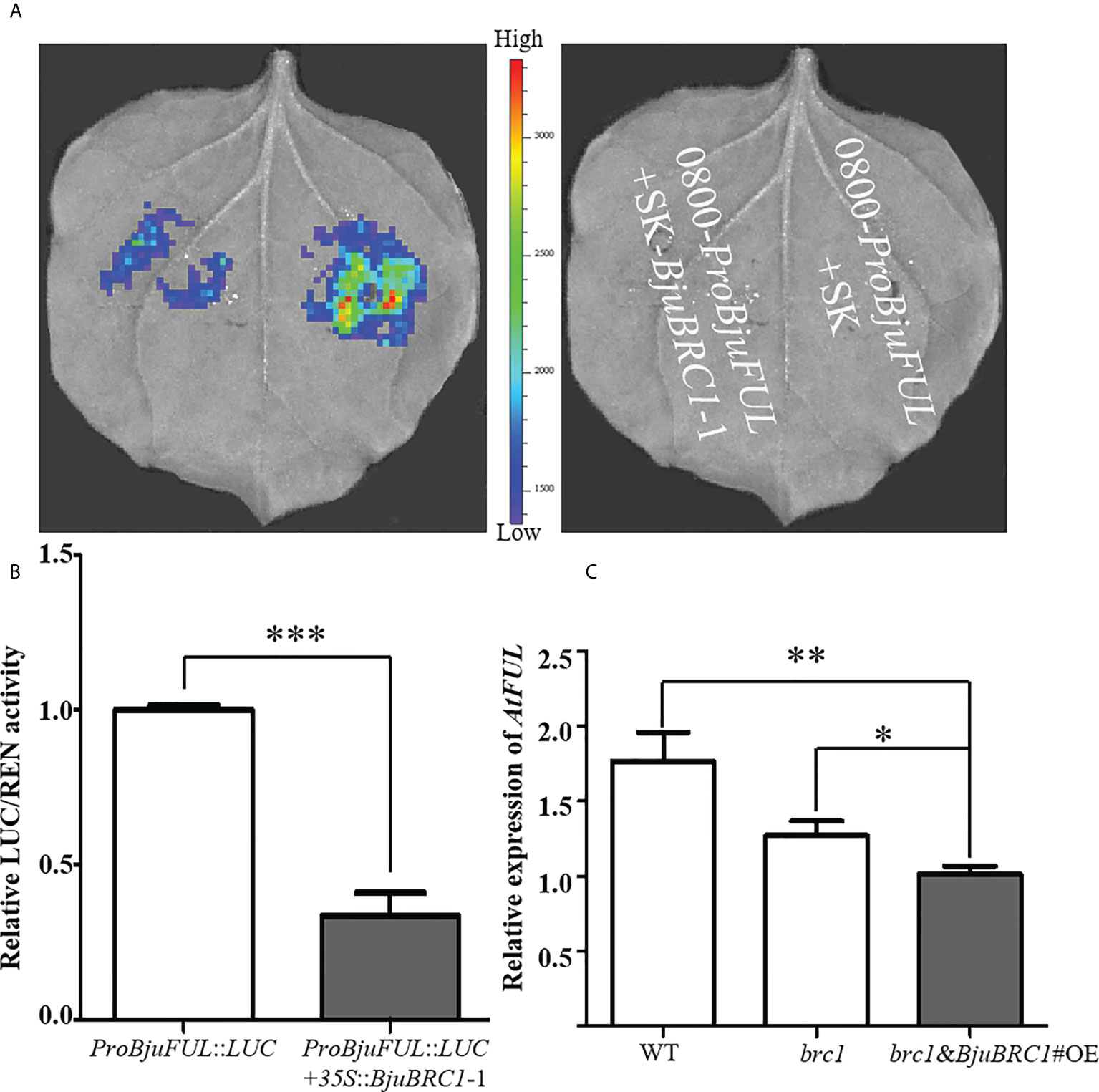

Dual-luciferase reporter system

The BjuFUL promoter containing the W-box element was amplified and digested with HindIII and Xho I and then recombined into the pGreenII0800-LUC vector as the reporter plasmid (Hellens et al., 2005). Similarly, BjuBRC1 was digested with SacI and BamH I and then inserted into the pGreenII62-SK vector as the effector plasmid. Using the freeze–thaw method, both pGreenII62-0800-ProBjuFUL and pGreenII62-SK-BjuBRC1 plasmids were introduced into A. tumefaciens strain GV3101 and then cultured at 28°C until OD600 = 0.9–1.1 in 50 ml YEB medium supplemented with 50 μg/ml kanamycin and 25 μg/ml rifampicin. The cells were harvested and resuspended in suspension medium (10 mM MgCl2, 100 μl of 100 mM acetosyringone, and 100 μl of 0.5 M MES) and then cultured for 2–3 h at room temperature in the dark. The agrobacteria were infiltrated into 1-month-old N. benthamiana leaves, and the infiltrated plant was placed in the dark for 24 h and then transferred to the light for 36 h. Luciferase signals were measured with a microplate reader. Transcriptional activity in the infiltrated tobacco leaves was determined as the ratio of LUC to REN with the Dual Luciferase Reporter Gene Assay Kit (YEASEN).

Luciferase activity assay

Nicotiana benthamiana leaves were injected with ProBjuFUL::LUC or co-injected with 35S::BjuBRC1 and ProBjuFUL::LUC and incubated at 22°C for 2–3 days. The injected leaves were detached and sprayed with 1 mM of D-luciferin solution (potassium salt, APExBIO) and incubated in the dark for 5–7 min. Luciferase luminescence in the infiltrated area was visualized using an IVIS Lumina Series III10899 Imaging System (America, PerkinElmer).

Results

Gene cloning and characterization of BjuBRC1 homologs in B. juncea

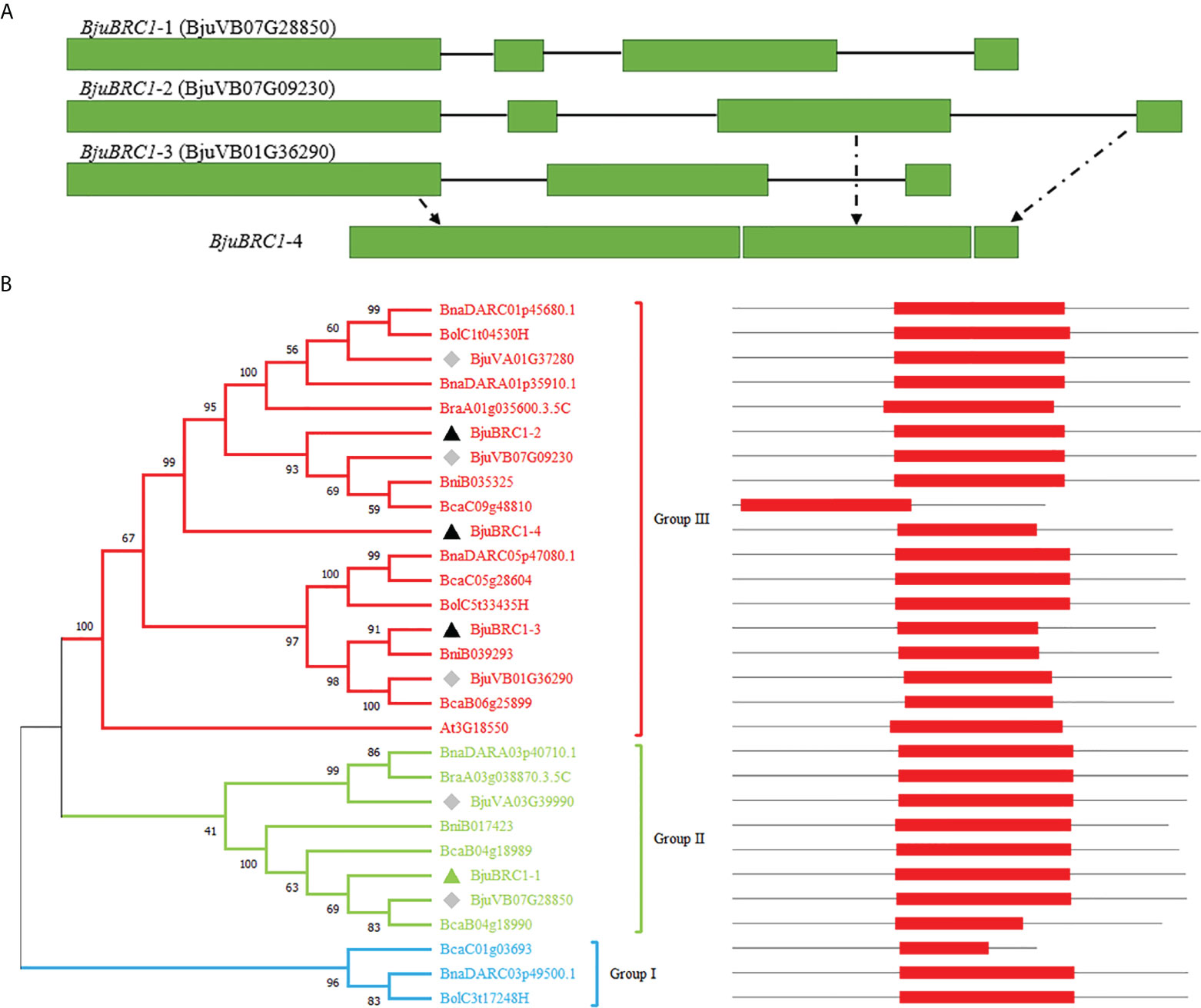

In this study, BjuBRC1 genes were cloned from B. juncea by PCR using gene-specific primers. Four homologous BjuBRC1 genes in the genome of B. juncea were sequenced, and the respective gene structures were analyzed (Figure 1A). The results indicated that their gene sequences were significantly different. Notably, the N-terminal region of the BjuBRC1-4 sequence was highly similar to that of BjuBRC1-3, whereas the central and C-terminal regions of BjuBRC1-4 were similar to those of BjuBRC1-2 (Figure 1A, Supplementary Figure 2). Therefore, BjuBRC1-4 was indicated to be a unique homolog that was not yet registered in the BRAD database.

Figure 1 BjuBRC1 gene structure and phylogenetic tree. (A) BjuBRC1 gene structure. The green rectangle parts indicate exons; the black lines indicate introns. BjuBRC1-4 has no accession number in the BRAD database, whose gene structure consists of parts of BjuBRC1-2 and BjuBRC1-3 (drawn by dotted lines). (B) Phylogenetic tree of BRC1 proteins from different plants in Brassicas; the accession number of all genes are shown in the picture. BRC1 proteins are classed as three groups (red, green, and blue) according to their evolutionary relationship. Triangles indicate the genes cloned in this study, and the green triangle indicates representative genes chosen to be studied. The diamonds indicate homologous genes of BjuBRC1 in BRAD. The location of TCP domains (red rectangle) in AA sequences are shown on the right.

A multiple alignment of the full-length amino acid sequences was generated to examine the phylogenetic relationships among the BjuBRC1 proteins and their orthologs from multiple species of Brassica. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining algorithm (Figure 1B). Phylogenetic analysis revealed the evolutionary relationship of BRC1 homologs in Brassicas. The Pfam database (http://pfam.xfam.o-rg/) was used to predict the conserved domains in the BRC1 protein sequences. The BjuBRC1-1 protein showed the highest similarity to the AtBRC1 (At3G18550) sequence, based on a BLAST search of BRAD. Therefore, BjuBRC1-1 was selected as representative to analyze the function of BjuBRC1 genes.

Expression patterns of BjuBRC1-1 in B. juncea

The expression patterns of BjuBRC1-1 at different developmental stages (in leaves) and in diverse organs (under LD, sampled while flowering) were analyzed by qPCR. The expression levels in the flower, floral bud, and leaf were higher than those in the root and stem (Supplementary Figure 3A).

It has been reported that BRC1 is induced under SD, resulting in growth cessation, in hybrid aspen (Maurya et al., 2020). Therefore, we explored the relative expression levels of BjuBRC1-1 in B. juncea leaves under LD and SD by qPCR. The results revealed that BjuBRC1-1 was expressed more abundantly under SD than under LD. However, the expression level decreased gradually with growth of the plant (Supplementary Figure 3B). Furthermore, SD delayed the growth and flowering of B. juncea plants (Supplementary Figure 4). Thus, BjuBRC1-1 may negatively regulate flowering in B. juncea.

Subcellular localization

It was speculated that the BjuBRC1 protein, as a transcription factor, would be localized in the nucleus. To investigate the subcellular localization of BjuBRC1-1, we fused BjuBRC1-1 to the N-terminus of the green fluorescent protein gene (GFP) and used Agrobacterium-mediated transformation to transiently express the fusion protein in leaves of Nicotiana benthamiana. The fluorescent signal of the BjuBRC1-1-GFP protein was only observed in the nucleus, whereas the GFP control signal was observed in the cytoplasm and nucleus (Figure 2). These results indicated that BjuBRC1-1 was a nuclear-localized protein and acted as a transcription factor.

Figure 2 The subcellular localization of BjuBRC1-1 protein and its two truncated proteins. The schematic diagram of two truncated proteins is shown on the right. GFP, GFP fluorescent; BF, bright-field; Merged, merged image of GFP and BF.

In potato, alternative splicing leads to the generation of two different protein isoforms from StBRC1a, namely, StBRC1aL (with a strong activation domain in the C-terminal region) and StBRC1aS (which lacks an activation domain in the C-terminal region). StBRC1aL is a nuclear protein and acts as a strong transcription factor that causes growth arrest, whereas StBRC1aS is localized to the cytoplasm and acts as a dominant-negative factor that antagonizes StBRC1aL, mainly by sequestering it outside the nucleus (Nicolas et al., 2015). Therefore, we constructed two truncated proteins, BjuBRC1-1-I and BjuBRC1-1-II (the structure of the truncated proteins is shown in Figure 2), to examine their subcellular localization to assess whether a similar molecular mechanism may exist in B. juncea. BjuBRC1-1-I was localized in the cytoplasm and nucleus, whereas BjuBRC1-1-II was detected in the nucleus only (Figure 2), indicating that the mechanism in B. juncea may differ from that of potato.

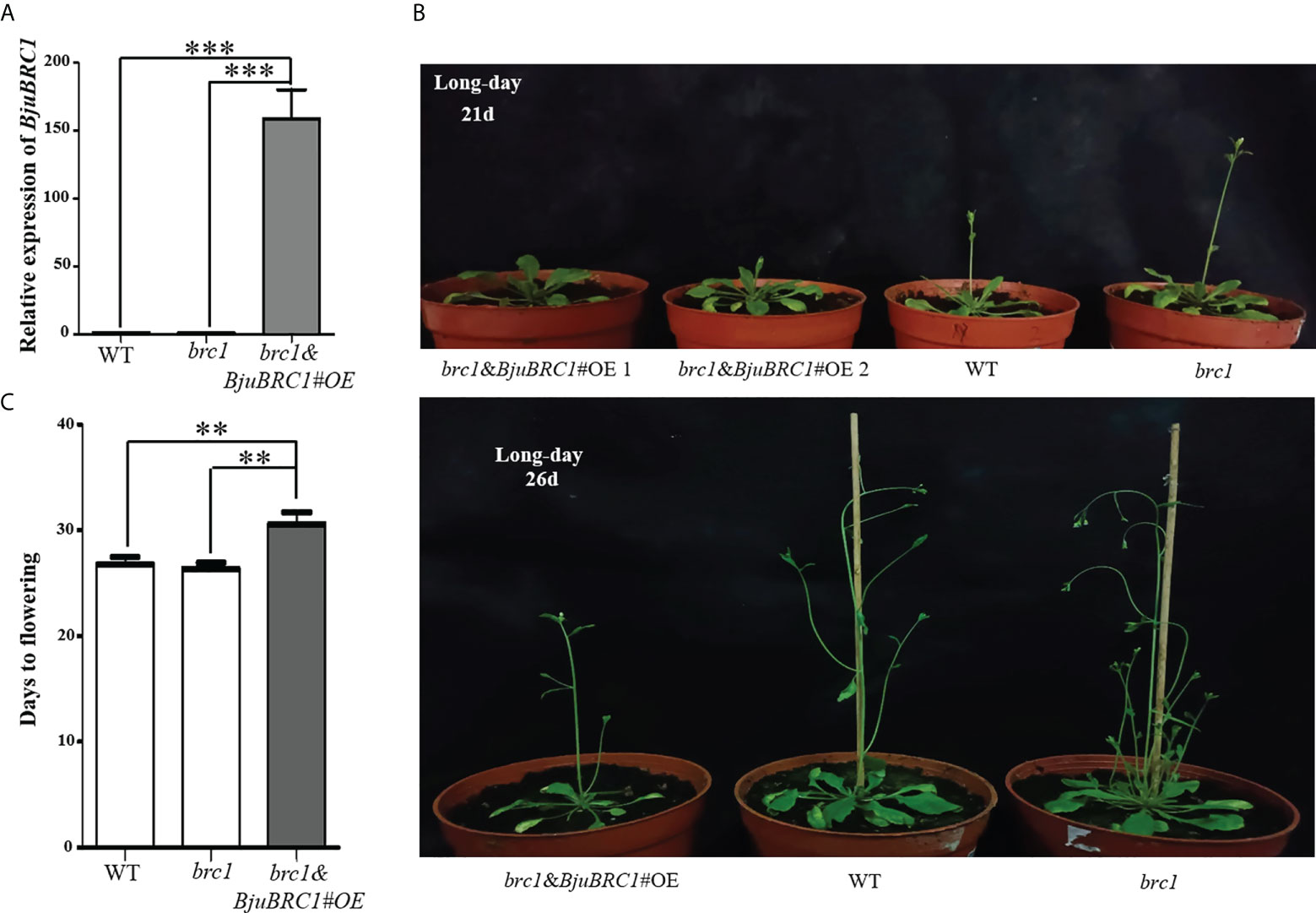

Overexpression of BjuBRC1-1 in Arabidopsis repressed flowering

To explore the biological functions of BjuBRC1, an overexpression vector driven by a 35S promoter was constructed. After Agrobacterium infection of Arabidopsis flowers (Bent and Clough, 1998), we obtained transgenic Arabidopsis plants in the brc1 mutant background. The transgenic Arabidopsis lines were verified by PCR (at the DNA level) and qPCR (at the RNA level) (Figure 3A, Supplementary Figure 5). Three transgenic lines were obtained, and their T3 progeny was selected for further phenotypic analysis. No difference was observed in the expression level of BjuBRC1 between transgenic Arabidopsis line 3 and the wild type (WT; brc1 mutant) in T3 plants; therefore, line 3 was not included in the statistics. Compared with WT plants, two transgenic lines (lines 1 and 2) showed a late-flowering phenotype, whereas no significant difference in flowering time was observed between the brc1 mutant and WT (Figure 3B). The indication that BjuBRC1 impacted on flowering time was consistent with the influence of BRC1 in hybrid aspen and Arabidopsis (Niwa et al., 2013; Maurya et al., 2020). In addition, the transgenic lines developed similar branches with the brc1 mutant (Supplementary Figure 6), which indicated that BjuBRC1-1 may not play a role in the regulation of branching.

Figure 3 Flowering time comparison of distinct Arabidopsis lines. (A) The relative expression level of BjuBRC1-1 in transgenic Arabidopsis (brc1 mutant background), WT, and brc1 Arabidopsis. “***” indicates significant difference, p < 0.001, by Student’ s t-test. (B) Overexpression of BjuBRC1-1 delayed flowering. (C) Days to flowering of the WT, brc1, and the transgenic Arabidopsis. Error bars represent SE. “**” indicates significant difference, p < 0.01, by Student’ s t-test.

BjuBRC1 homologs interacted with BjuFT in vivo

It has been reported that BRC1 physically interacts with FT and inhibits flowering in axillary buds by antagonizing FT action in Arabidopsis (Niwa et al., 2013) and hybrid aspen (Maurya et al., 2020). Five FT homologous genes were detected in the genome of B. juncea (BjuVB05G49700, BjuVA02G18040, BjuVB03G38700, BjuVA07G33060, and BjuVA07G42420) through BRAD. In this study, two homologous BjuFT genes (BjuVB05G49700 and BjuVA07G33060) that showed high sequence similarities were cloned, and one (BjuVB05G49700) was selected for the following analysis. A yeast two-hybrid assay was performed to examine the possible interactions between BjuFT and four BjuBRC1 proteins. All fused yeast strains were unable to grow on the QDO medium supplemented with AbA and X-α-gal (Figure 4A). Interaction of BjuBRC1-1 with FT was not detected in yeast. To further explore the interaction between BjuBRC1-1 and BjuFT, BiFC and LCI assays were performed. The results revealed that BjuBRC1-1 was capable of interacting with BjuFT in vivo (Figures 4B, C).

Figure 4 Interaction analysis between BjuBRC1-1 and BjuFT. (A) Yeast two-hybrid assay between BjuBRC1-1 and BjuFT. (B) BiFC assays between YN-BjuBRC1-1 and YC-BjuFT. YFP, YFP fluorescence; BF, bright-field; Merged, merged image of YFP and BF (C) LCI assays of BjuBRC1-nLuc with cLuc-BjuFT.

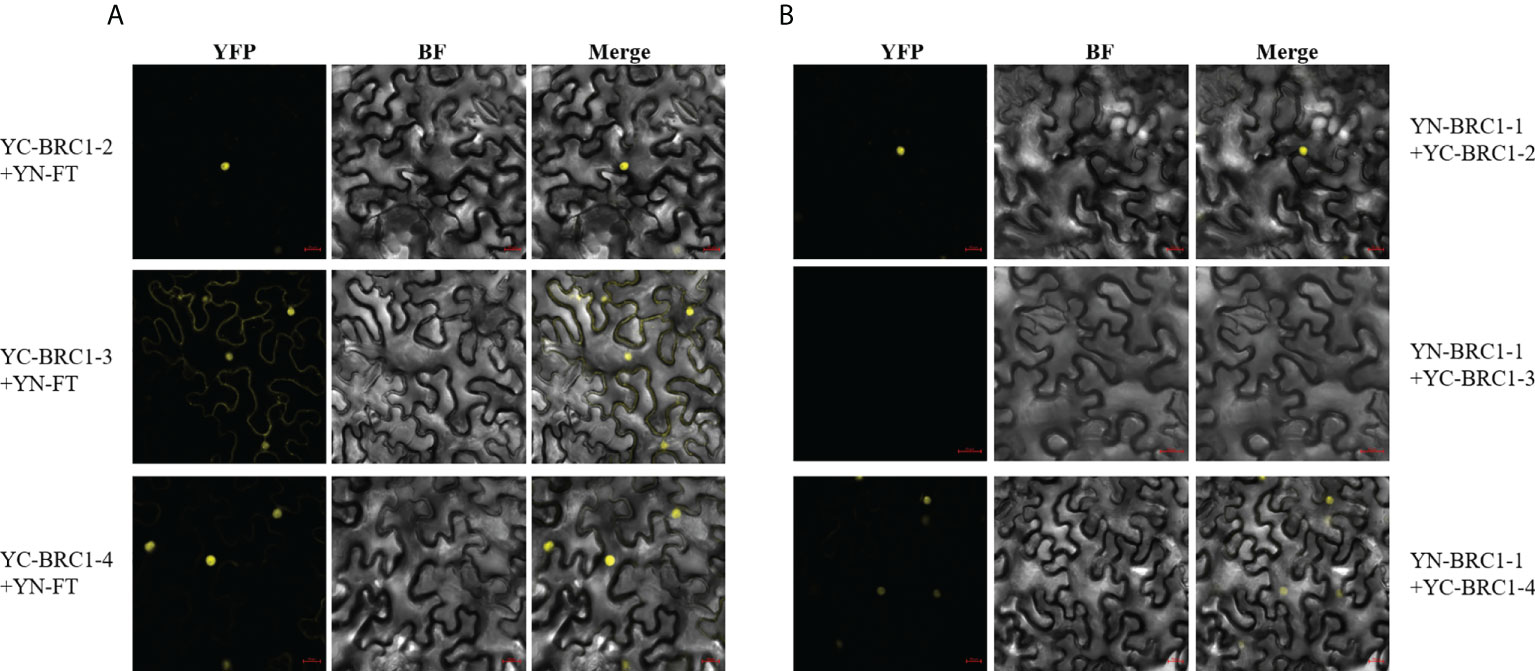

To further assess the conservation of the interaction between BRC1 and FT in B. juncea, the interactions of three homologous BjuBRC1 proteins with BjuFT were studied. A yeast two-hybrid assay was conducted to detect the separate interactions between the BjuBRC1 proteins and BjuFT. The results showed that interactions of the three BjuBRC1 homologs (BRC1-2, BRC1-3, and BRC1-4) with BjuFT were not detected in yeast (Supplementary Figure 7).

Next, BiFC assays were performed and the results indicated that BjuFT was capable of interacting with BjuBRC1-2, BjuBRC1-3, and BjuBRC1-4 in vivo (Figure 5A, Supplementary Figure 8). Notably, BjuBRC1-3 was colocalized in the nucleus and cytomembrane and interacted with BjuFT, which was distinct from the other BjuBRC1 homologs. These results suggested that BjuBRC1 may regulate flowering by interacting with BjuFT to antagonize the CO/FT pathway, resulting in downregulation of its downstream targets (Niwa et al., 2013; Maurya et al., 2020).

Figure 5 Detections of three BjuBRC1 homologous proteins interact with BjuFT or each other in vivo. (A) BiFC assays between three BjuBRC1 proteins and BjuFT (B) BiFC assays between BjuBRC1-1 and BjuBRC1-2, BjuBRC1-3, or BjuBRC1-4. YFP, YFP fluorescence; BF, bright-field; Merged, merged image of YFP and BF.

BjuBRC1 homologs formed heterodimers

BRC1 forms homo- and heterodimers in Solanum tuberosum (Nicolas et al., 2015). To explore if a similar mechanism may operate in B. juncea, the interactions of BjuBRC1 proteins were examined by means of a yeast two-hybrid assay. The results indicated that at least BjuBRC1-3 could not form heterodimers with itself and other homologous proteins in yeast (Supplementary Figure 7B). A BiFC assay in N. benthamiana leaves indicated that BjuBRC1-1 could form heterodimers with BjuBRC1-2 or BjuBRC1-4, but not with BjuBRC1-3, which was consistent with the results of the yeast two-hybrid assay (Figure 5B, Supplementary Figure 9). In addition, we further tested other BiFC combinations to detect homologous interactions and the results showed there were no YFP signals in these BiFC combinations (Supplementary Figure 10). These results provided evidence that BjuBRC1 proteins could form heterodimers, but whether this mechanism mediates the regulation of flowering requires further study.

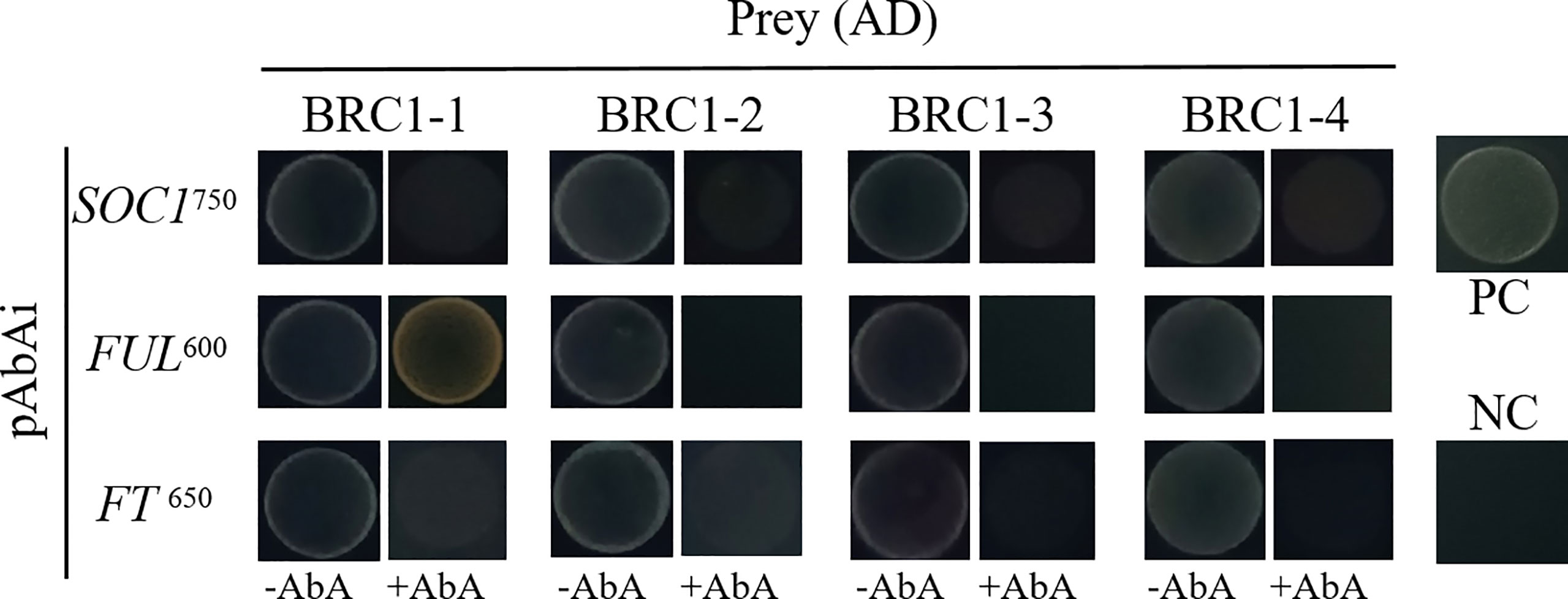

BjuBRC1-1 repressed BjuFUL expression

To examine if BjuBRC1 proteins may influence the flowering time by directly binding to the promoters of floral regulatory genes in B. juncea, we performed a yeast one-hybrid assay to test the interactions of BjuBRC1s with ProBjuFUL (BjuVA03G46090, one of the six detected in BRAD), ProBjuFT (BjuVB05G49700, one of the five in BRAD), and ProBjuSOC1 (BjuVB08G24640, one of the six in BRAD). Only the yeast strain harboring ProBjuFUL and pGADT7-BjuBRC1-1 was able to grow on SD/−Leu/AbA600 plates, indicating that BjuBRC1-1 may bind to the promoter of BjuFUL (Figure 6). The other BjuBRC1 homologous proteins were not capable of binding to the promoter of BjuFUL, which indicated that the mechanism of BjuBRC1 binding to ProBjuFUL was not conserved (Figure 6).

Figure 6 Yeast one hybrid assay. Yeast one-hybrid assay to test whether the four BjuBRC1 proteins could directly bind to the promoters of BjuFT, BjuFUL, or BjuSOC1. pGADT7-BjuBRC1s was transformed into yeast Y1H strains in combination with pAbAi-ProBjuFT, pAbAi-ProBjuFUL, and pAbAi-ProBjuSOC1, respectively. The transformed strains all were grown on SD/-Leu selective media containing aureobasidin A (ABA) (650, 600, and 750 μg/l, respectively). PC, positive control; NC, negative control.

To explore the amino acid residues required for binding to ProBjuFUL, four truncated proteins of BjuBRC1-1 were generated (Supplementary Figure 11A). Yeast one-hybrid assays demonstrated that only the full-length BjuBRC1-1 protein was capable of interacting with the BjuFUL promoter (Figures 6, Supplementary Figure 11). Subsequently, a LUC assay and dual-luciferase reporter system were performed to clarify the mechanism by which BjuBRC1-1 regulated the downstream gene BjuFUL. The results indicated that BjuBRC1-1 was able to repress the transcription of BjuFUL (Figures 7A, B).

Figure 7 BjuBRC1-1 regulates the expression of BjuFUL. (A) LUC assays to detect the activation/repression function of BjuBRC1-1 protein to ProBjuFUL (B) Dual-luciferase reporter assay to verify whether BjuBRC1-1 protein regulates the transcription of BjuFUL. (C) Relative expression levels of AtFUL in transgenic Arabidopsis compared with WT or brc1 mutant. Error bars represent SE. “***” indicates significant difference, p < 0.001; “**”, p < 0.01; “*”, p < 0.05. By Student’ s t-test.

To verify this conclusion, a qPCR analysis was performed to quantify the expression level of AtFUL in leaves of WT, brc1 mutant, and transgenic Arabidopsis plants. In accordance with the abovementioned results, AtFUL expression was reduced in transgenic Arabidopsis compared with that in the WT and brc1 mutant (Figure 7C).

Collectively, from the present results, we concluded that BjuBRC1-1 was capable of directly binding to the promoter of BjuFUL to repress its expression in B. juncea and speculated that this mechanism may be involved in the regulation of flowering.

Discussion

Considerable efforts have been made to illuminate the complex molecular networks that regulate flowering time owing to its importance for reproductive success and crop yields. The BRC1 proteins, a member of TCP transcriptional factors family, are well known to function as an essential hub for different signals to regulate bud growth in many plant species (Aguilar-Martínez et al., 2007; Dun et al., 2009; Leyser, 2009; Beveridge and Kyozuka, 2010; Rameau et al., 2015; Nicolas and Cubas, 2016; Xie et al., 2020). In addition, BRC1 is involved in the regulation of flowering in certain plants, such as Arabidopsis and hybrid aspen (Niwa et al., 2013; Maurya et al., 2020). However, the functions of BRC1 genes in Brassica species, especially B. juncea, remain unknown.

In this study, we identified four BRC1 genes in the B. juncea genome and one (BjuBRC1-1) was selected for study in detail as a representative of the genes. A subcellular localization analysis indicated that BjuBRC1-1 was functional as a transcription factor localized to the nucleus (Figure 2). A qPCR analysis demonstrated that BjuBRC1-1 could be induced by SD rather than LD (Supplementary Figure 3B), which was consistent with the induction of BRC1 in hybrid aspen (Maurya et al., 2020). Short days is a negative factor in the regulation of flowering plant development; therefore, we speculated that BjuBRC1-1 may function as a repressor of flowering.

To evaluate this hypothesis, we generated three transgenic Arabidopsis lines (in the brc1 mutant background) that ectopically expressed BjuBRC1-1. The brc1 mutant has an early-flowering phenotype identical to the WT, whereas the transgenic Arabidopsis plants showed a late-flowering phenotype under LD (Figures 3B, C). To explore the mechanism by which BjuBRC1-1 influences flowering time, we tested whether BjuBRC1-1 could interact with BjuFT, similar to previous reports for Arabidopsis and hybrid aspen (Niwa et al., 2013; Maurya et al., 2020). Yeast two-hybrid, BiFC, and LCI assays showed that BjuBRC1-1 was capable of interacting with BjuFT in vivo but not in yeast (Figure 4). Based on these interactions between BjuBRC1 proteins and BjuFT, we speculated that BjuBRC1 proteins may delay flowering by interfering with the function of BjuFT. In rice, Hd3a is non-functional as a florigen without interacting with 14-3-3 proteins (Taoka et al., 2011). This is probably the reason that BjuBRC1 proteins were unable to interact with BjuFT in yeast. In addition, BjuBRC1 was capable of forming heterodimers, which thus probably enhanced its repressive influence on BjuFT (Figure 5B). Moreover, we found that BjuBRC1-1 protein (only full-length proteins) could bind to the promoter of BjuFUL directly to reduce its expression (Figures 6, 7A, B Supplementary Figure 11). Moreover, AtFUL expression was reduced in transgenic Arabidopsis that ectopically expressed BjuBRC1-1 (Figure 7C).

Studies of floral organ development in model plants indicate that homologous genes controlling flower development are classifiable into five groups: classes A, B, C, D, and E (Weigel and Meyerowitz, 1994). FUL shows high similarity with the class A gene APETALA 1 (AP1), has a conserved C-terminus, and is involved in the regulation of flower and fruit development in Arabidopsis. Most MADS-box genes are expressed only in flowers, whereas FUL is expressed at different specific stages of plant development (Coen and Meyerowitz, 1991; Borner et al., 2000; Drobyazina and Khavkin, 2006; Melzer et al., 2008). Thus, it is recognized that FUL plays an essential role in the control of flowering. Based on previous studies of FUL, we speculate that BjuBRC1-1 can directly repress BjuFUL expression to influence flowering or other growth-related processes in B. juncea.

Previous research has indicated that two FT-LIKE paralogs, StSP3D and StSP6A, control floral and tuberization transitions in potato (Navarro et al., 2011), and the orthologs of the CO and FT proteins have a conserved function in the control of tuberization in photoperiodic tuberization (Rodríguez-Falcón et al., 2006; González-Schain et al., 2012). A recent study found that BRC1b acts as a tuberization repressor in aerial axillary buds via interaction with SP6A, which prevents buds from competing in sink strength with stolons in potato (Nicolas et al., 2022). Based on the interaction between BjuBRC1s and BjuFT, we speculate that BjuBRC1 may be involved in the regulation of tuberization in B. juncea (mustard), which requires further investigation.

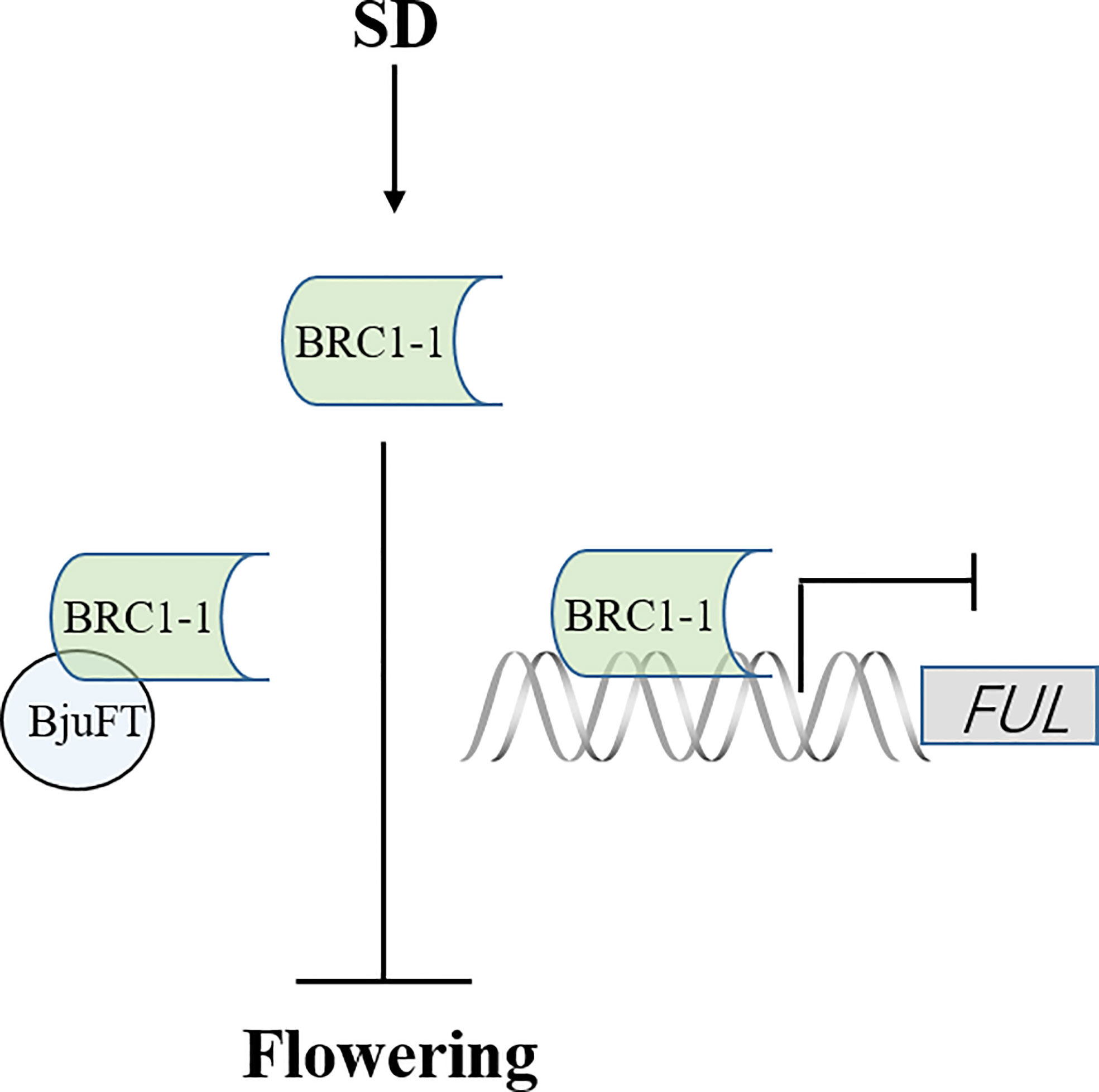

The present study identified four homologous proteins of BjuBRC1 with distinct C-terminal and N-terminal regions in B. juncea. However, only BjuBRC1-1 could bind to the promoter of BjuFUL. Therefore, we speculate that the ability to bind specifically to the promoter of BjuFUL is conferred by the particular sequence in the N-terminal or C-terminal region. Interestingly, four homologous proteins could interact with BjuFT in vivo, and BjuBRC1-3 uniquely interacted in the cytomembrane and nucleus. Whether this mechanism is involved in the regulation of B. juncea development requires further study. Whether the five homologous BjuBRC1 genes in B. juncea exhibit functional redundancy in the regulation of flowering or branching is currently unclear. In addition, it is possible that BjuBRC1 proteins interact with the promoters of other floral regulatory genes in addition to the BjuFUL promoter. In summary, a proposed model of BjuBRC1-1 to regulate flowering is established (Figure 8). And the present results provide evidence that BjuBRC1 genes may be involved in the regulation of flowering and provide a theoretical basis for breeding mustard cultivars with a specific desired flowering and maturity time.

Figure 8 A proposed model of BjuBRC1-1 to regulate flowering. FT, FLOWERING LOCUS T; FUL, FRUITFULL; arrow, enhanced expression; horizontal line, inhibited expression.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

QT and JF designed the study. QT, JF, QD, and HL performed the experiments and analyzed the data. JF wrote the paper. QT, QD, HL, DW, and ZW revised the manuscript. QT is the corresponding author. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was funded by grants from the Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing (cstc2019jcyj-zdxmX0022) and the Technology Innovation and Application Development Project of CQ CSTC, China (cstc2021jscx-gksbX0021).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2022.986811/full#supplementary-material

References

Aguilar-Martínez, J. A., Poza-Carrión, C., Cubas, P. (2007). Arabidopsis Branched1 acts as an integrator of branching signals within axillary buds. Plant Cell 19, 458–472. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.048934

Amasino, R. (2004). Vernalization, competence, and the epigenetic memory of winter. Plant Cell 16, 2553–2559. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.161070

Andrés, F., Coupland, G. (2012). The genetic basis of flowering responses to seasonal cues. Nat. Rev. Genet. 13, 627–639. doi: 10.1038/nrg3291

Bent, A. F., Clough, S. J. (1998). Floral dip: a simplified method for agrobacterium-mediated transformation of arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 16, 735–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x

Beveridge, C. A., Kyozuka, J. (2010). New genes in the strigolactone-related shoot branching pathway. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 13, 34–39. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2009.10.003

Blázquez, M. A., Ahn, J. H., Weigel, D. (2003). A thermosensory pathway controlling flowering time in arabidopsis thaliana. Nat. Genet. 33, 168–171. doi: 10.1038/ng1085

Blümel, M., Dally, N., Jung, C. (2015). Flowering time regulation in crops-what did we learn from arabidopsis? Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 32, 121–129. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2014.11.023

Borner, R., Kampmann, G., Chandler, J., Gleißner, R., Wisman, E., Apel, K., et al. (2000). A MADS domain gene involved in the transition to flowering in arabidopsis. Plant J. 24, 591–599. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2000.00906.x

Castillejo, C., Pelaz, S. (2008). The balance between CONSTANS and TEMPRANILLO activities determines FT expression to trigger flowering. Curr. Biol. 18, 1338–1343. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.07.075

Coen, E. S., Meyerowitz, E. M. (1991). The war of the whorls: genetic interactions controlling flower development. Nature 353, 31–37. doi: 10.1038/353031a0

Corbesier, L., Vincent, C., Jang, S., Fornara, F., Fan, Q., Searle, I., et al. (2007). FT protein movement contributes to long-distance signaling in floral induction of arabidopsis. Science 316, 1030–1033. doi: 10.1126/science.1141752

Cubas, P. (2002). Role of TCP genes in the evolution of morphological characters in angiosperms. Systemat. Associat. Special 65, 247–266. doi: 10.1201/9781420024982.ch13

Cubas, P., Lauter, N., Doebley, J., Coen, E. (1999). The TCP domain : a motif found in proteins regulating plant growth and development. Plant J. 18, 215–222. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1999.00444.x

Cubas, P., Martı, M. (2009). TCP genes : a family snapshot ten years later. Trends Plant Sci. 15, 31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2009.11.003

Dally, N., Xiao, K., Holtgräwe, D., Jung, C. (2014). The B2 flowering time locus of beet encodes a zinc finger transcription factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 111, 10365–10370. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1404829111

Doebley, J., Stec, A., Hubbard, L. (1997). The evolution of apical dominance in maize. Nature 386, 485–488. doi: 10.1038/386485a0

Drobyazina, P. E., Khavkin, E. E. (2006). Homologs of Apetala1/Fruitfull in solanum plants. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 53, 217–222. doi: 10.1134/S1021443706020117

Dun, E. A., Brewer, P. B., Beveridge, C. A. (2009). Strigolactones: discovery of the elusive shoot branching hormone. Trends Plant Sci. 14, 364–372. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2009.04.003

Ferrándiz, C., Gu, Q., Martienssen, R., Yanofsky, M. F. (2000). Redundant regulation of meristem identity and plant architecture by FRUITFULL, APETALA1 and CAULIFLOWER. Development 127, 725–734. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.4.725

Finlayson, S. A. (2007). Arabidopsis TEOSINTE BRANCHED1-LIKE 1 regulates axillary bud outgrowth and is homologous to monocot TEOSINTE BRANCHED1. Plant Cell Physiol. 48, 667–677. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcm044

Fornara, F., de Montaigu, A., Coupland, G. (2010). SnapShot: Control of flowering in arabidopsis. Cell 141, 550–550. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.04.024

González-Schain, N. D., Díaz-Mendoza, M., Zurczak, M., Suárez-López, P. (2012). Potato CONSTANS is involved in photoperiodic tuberization in a graft-transmissible manner. Plant J. 70, 678–690. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.04909.x

Halliday, K. J., Salter, M. G., Thingnaes, E., Whitelam, G. C. (2003). Phytochrome control of flowering is temperature sensitive and correlates with expression of the floral integrator FT. Plant J. 33, 875–885. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01674.x

Han, P., García-Ponce, B., Fonseca-Salazar, G., Alvarez-Buylla, E. R., Yu, H. (2008). AGAMOUS-LIKE 17, a novel flowering promoter, acts in a FT-independent photoperiod pathway. Plant J. 55, 253–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03499.x

Hellens, R. P., Allan, A. C., Friel, E. N., Bolitho, K., Grafton, K., Templeton, M. D., et al. (2005). Transient expression vectors for functional genomics, quantification of promoter activity and RNA silencing in plants. Plant Methods 1, 13. doi: 10.1186/1746-4811-1-13

Howarth, D. G., Donoghue, M. J. (2006). Phylogenetic analysis of the “ECE” (CYC/TB1) clade reveals duplications predating the core eudicots. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103, 9101–9106. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602827103

Kosugi, S., Ohashi, Y. (2002). DNA Binding and dimerization specicity and potential targets for the TCP protein family. Plant J. 30, 337–348. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2002.01294.x

Kosugi, S., Ohashi, Y., The, S., Cell, P., Sep, N. (2015). PCF1 and PCF2 specifically bind to cis elements in the rice proliferating cell nuclear antigen gene. Plant Cell 9, 1607–1619. doi: 10.2307/3870447

Kumar, S. V., Lucyshyn, D., Jaeger, K. E., Alós, E., Alvey, E., Harberd, N. P., et al. (2012). Transcription factor PIF4 controls the thermosensory activation of flowering. Nature 484, 242–245. doi: 10.1038/nature10928

Leyser, O. (2009). The control of shoot branching: An example of plant information processing. Plant Cell Environ. 32, 694–703. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.01930.x

Li, Z., Ding, Y., Xie, L., Jian, H., Gao, Y., Yin, J., et al. (2020). Regulation by sugar and hormone signaling of the growth of brassica napus l. axillary buds at the transcriptome level. Plant Growth Regul. 90, 571–584. doi: 10.1007/s10725-020-00581-9

Liu, J., Cheng, X., Liu, P., Sun, J. (2017). miR156-targeted SBP-box transcription factors interact with DWARF53 to regulate teosinte branched1 and barren STALK1 expression in bread wheat. Plant Physiol. 174, 1931–1948. doi: 10.1104/pp.17.00445

Livak, K. J., Schmittgen, T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-ΔΔCT method. Methods 25, 402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262

Li, W., Wang, H., Yu, D. (2016). Arabidopsis WRKY transcription factors WRKY12 and WRKY13 oppositely regulate flowering under short-day conditions. Mol. Plant 9, 1492–1503. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2016.08.003

Li, X., Zhang, G., Liang, Y., Hu, L., Zhu, B., Qi, D., et al. (2021). TCP7 interacts with nuclear factor-ys to promote flowering by directly regulating SOC1 in arabidopsis. Plant J. 108, 1493–1506. doi: 10.1111/tpj.15524

Li, D., Zhang, H., Mou, M., Chen, Y., Xiang, S., Chen, L., et al. (2019). Arabidopsis class II TCP transcription factors integrate with the FT-FD module to control flowering. Plant Physiol. 181, 97–111. doi: 10.1104/pp.19.00252

Luo, D., Carpenter, R., Vincent, C., Copsey, L., Coen, E. (1996). Origin of floral asymmetry in Antirrhinum. Nature 383, 794–799. doi: 10.1038/383794a0

Martín-Trillo, M., Grandío, E. G., Serra, F., Marcel, F., Rodríguez-Buey, M. L., Schmitz, G., et al. (2011). Role of tomato BRANCHED1-like genes in the control of shoot branching. Plant J. 67, 701–714. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04629.x

Maurya, J. P., Singh, R. K., Miskolczi, P. C., Prasad, A. N., Jonsson, K., Wu, F., et al. (2020). Branching regulator BRC1 mediates photoperiodic control of seasonal growth in hybrid aspen. Curr. Biol. 30, 122–126.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2019.11.001

Melzer, S., Lens, F., Gennen, J., Vanneste, S., Rohde, A., Beeckman, T. (2008). Flowering-time genes modulate meristem determinacy and growth form in arabidopsis thaliana. Nat. Genet. 40, 1489–1492. doi: 10.1038/ng.253

Muntha, S. T., Zhang, L., Zhou, Y., Zhao, X., Hu, Z., Yang, J., et al. (2019). Phytochrome a signal transduction 1 and CONSTANS-LIKE 13 coordinately orchestrate shoot branching and flowering in leafy brassica juncea. Plant Biotechnol. J. 17, 1333–1343. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13057

Navarro, C., Abelenda, J. A., Cruz-Oró, E., Cuéllar, C. A., Tamaki, S., Silva, J., et al. (2011). Control of flowering and storage organ formation in potato by FLOWERING LOCUS T. Nature 478, 119–122. doi: 10.1038/nature10431

Navaud, O., Dabos, P., Carnus, E., Tremousaygue, D., Hervé, C. (2007). TCP Transcription factors predate the emergence of land plants. J. Mol. Evol. 65, 23–33. doi: 10.1007/s00239-006-0174-z

Nicolas, M., Rodrı́guez-Buey, M. L., Franco-Zorrilla, J. M., Cubas, P. (2015). A recently evolved alternative splice site in the BRANCHED1a gene controls potato plant architecture. Curr. Biol. 25, 1799–1809. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.05.053

Nicolas, M., Cubas, P. (2016). The role of TCP transcription factors in shaping flower structure, leaf morphology, and plant architecture. Gonzalez, D. H. (Ed.), Plant Transcription Factors: Evolutionary, Structural And Functional Aspects, Elsevier, 249–267. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-800854-6.00016-6

Nicolas, M., Torres-Pérez, R., Wahl, V., Cruz-Oró, E., Rodríguez-Buey, M. L., Zamarreño, A. M., et al. (2022). Spatial control of potato tuberization by the TCP transcription factor BRANCHED1b. Nat. Plants 8, 281–294. doi: 10.1038/s41477-022-01112-2

Niwa, M., Daimon, Y., Kurotani, K. I., Higo, A., Pruneda-Paz, J. L., Breton, G., et al. (2013). BRANCHED1 interacts with FLOWERING LOCUS T to repress the floral transition of the axillary meristems in arabidopsis. Plant Cell 25, 1228–1242. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.109090

Pin, P. A., Nilsson, O. (2012). The multifaceted roles of FLOWERING LOCUS T in plant development. Plant Cell Environ. 35, 1742–1755. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2012.02558.x

Pnueli, L., Gutfinger, T., Hareven, D., Ben-Naim, O., Ron, N., Adir, N., et al. (2001). Tomato SP-interacting proteins define a conserved signaling system that regulates shoot architecture and flowering. Plant Cell 13, 2687–2702. doi: 10.1105/tpc.13.12.2687

Rameau, C., Bertheloot, J., Leduc, N., Andrieu, B., Foucher, F., Sakr, S. (2015). Multiple pathways regulate shoot branching. Front. Plant Sci. 5. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00741

Rodríguez-Falcón, M., Bou, J., Prat, S. (2006). Seasonal control of tuberization in potato: Conserved elements with the flowering response. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 57, 151–180. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105224

Shen, J., Zhang, Y., Ge, D., Wang, Z., Song, W., Gu, R., et al. (2019). CsBRC1 inhibits axillary bud outgrowth by directly repressing the auxin efflux carrier CsPIN3 in cucumber. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 116, 17105–17114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1907968116

Simpson, G. G., Dean, C. (2002). Arabidopsis, the rosetta stone of flowering time. Science 296, 285–289. doi: 10.1126/science.296.5566.285

Tamaki, S., Matsuo, S., Wong, H. L., Yokoi, S., Shimamoto, K. (2007). Hd3a protein is a mobile flowering signal in rice. Science 316, 1033–1036. doi: 10.1126/science.1141753

Taoka, K. I., Ohki, I., Tsuji, H., Furuita, K., Hayashi, K., Yanase, T., et al. (2011). 14-3-3 proteins act as intracellular receptors for rice Hd3a florigen. Nature 476, 332–335. doi: 10.1038/nature10272

Wang, J. W., Czech, B., Weigel, D. (2009). miR156-regulated SPL transcription factors define an endogenous flowering pathway in arabidopsis thaliana. Cell 138, 738–749. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.014

Weigel, D., Meyerowitz, E. M. (1994). The ABCs of floral homeotic genes. Cell 78, 203–209. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90291-7

Wickland, D. P., Hanzawa, Y. (2015). The FLOWERING LOCUS T/TERMINAL FLOWER 1 gene family: functional evolution and molecular mechanisms. Mol. Plant 8, 983–997. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2015.01.007

Wigge, P. A., Kim, M. C., Jaeger, K. E., Busch, W., Schmid, M., Lohmann, J. U., et al. (2005). Integration of spatial and temporal information during floral induction in arabidopsis. Science 309, 1056–1059. doi: 10.1126/science.1114358

Xie, Y., Liu, Y., Ma, M., Zhou, Q., Zhao, Y., Zhao, B., et al. (2020). Arabidopsis FHY3 and FAR1 integrate light and strigolactone signaling to regulate branching. Nat. Commun. 11, 1955. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15893-7

Yamaguchi, A., Wu, M. F., Yang, L., Wu, G., Poethig, R. S., Wagner, D. (2009). The microRNA-regulated SBP-box transcription factor SPL3 is a direct upstream activator of LEAFY, FRUITFULL, and APETALA1. Dev. Cell 17, 268–278. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.06.007

Zhang, L., Yu, H., Lin, S., Gao, Y. (2016). Molecular characterization of FT and FD homologs from eriobotrya deflexa nakai forma koshunensis. Front. Plant Sci. 7. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00008

Zhou, Z., Bi, G., Zhou, J. M. (2018). Luciferase complementation assay for protein-protein interactions in plants. Curr. Protoc. Plant Biol. 3, 42–50. doi: 10.1002/cppb.20066

Keywords: BjuBRC1, BjuFT, BjuFUL, flowering, Brassica juncea

Citation: Feng J, Deng Q, Lu H, Wei D, Wang Z and Tang Q (2022) Brassica juncea BRC1-1 induced by SD negatively regulates flowering by directly interacting with BjuFT and BjuFUL promoter. Front. Plant Sci. 13:986811. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.986811

Received: 05 July 2022; Accepted: 12 September 2022;

Published: 30 September 2022.

Edited by:

Sachin Teotia, Sharda University, IndiaReviewed by:

Hyo-Jun Lee, Korea Research Institute of Bioscience and Biotechnology (KRIBB), South KoreaChris Helliwell, Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), Australia

Copyright © 2022 Feng, Deng, Lu, Wei, Wang and Tang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Qinglin Tang, dGFuZ3FsQHN3dS5lZHUuY24=

Junjie Feng

Junjie Feng Qinlin Deng

Qinlin Deng Huanhuan Lu

Huanhuan Lu Dayong Wei1,2

Dayong Wei1,2 Zhimin Wang

Zhimin Wang Qinglin Tang

Qinglin Tang