94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Plant Sci., 14 July 2022

Sec. Plant Nutrition

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.853220

This article is part of the Research TopicInsights in Plant Nutrition: 2021View all 13 articles

Due to the rising concentration of atmospheric CO2, climate change is predicted to intensify episodes of drought. However, our understanding of how combined environmental conditions, such as elevated CO2 and drought together, will influence crop-insect interactions is limited. In the present study, the direct effects of combined elevated CO2 and drought stress on wheat (Triticum aestivum) nutritional quality and insect resistance, and the indirect effects on the grain aphid (Sitobion miscanthi) performance were investigated. The results showed that, in wheat, elevated CO2 alleviated low water content caused by drought stress. Both elevated CO2 and drought promoted soluble sugar accumulation. However, opposite effects were found on amino acid content—it was decreased by elevated CO2 and increased by drought. Further, elevated CO2 down-regulated the jasmonic acid (JA) -dependent defense, but up-regulated the salicylic acid (SA)-dependent defense. Meanwhile, drought enhanced abscisic acid accumulation that promoted the JA-dependent defense. For aphids, their feeding always induced phytohormone resistance in wheat under either elevated CO2 or drought conditions. Similar aphid performance between the control and the combined two factors were observed. We concluded that the aphid damage suffered by wheat in the future under combined elevated CO2 and drier conditions tends to maintain the status quo. We further revealed the mechanism by which it happened from the aspects of wheat water content, nutrition, and resistance to aphids.

Elevated CO2 is identified as one major driving force of global climate change, and results in higher air temperature and altered precipitation patterns, which increase the area of arid areas (IPCC, 2014; Li et al., 2014). In the agroecosystem, the co-evolution of plants and insects is influenced by distinct environmental factors, such as CO2, soil moisture, and air temperature. Under complex climate change, to clarify the effects of multiple environmental factors—especially elevated CO2 alongside other factors on plant-insect interactions—is crucial for better understanding the damage as well as the occurrence trends of insect pests (Murray et al., 2013; Scherber et al., 2013; Zandalinas et al., 2018; Hervé et al., 2019; Wei et al., 2022).

Elevated CO2 changes the primary and secondary metabolism of plants by stimulating the photosynthetic rate (Zavala et al., 2017), which not only resulted in increased carbon:nitrogen ratio, but also changed the insect resistance in plants (Zavala et al., 2013; Sun et al., 2015, 2016; Guo et al., 2017; Johnson et al., 2022). Meanwhile, drought stress drives plants to develop a number of physiological responses as well, such as closing stoma, increasing carbohydrate and amino acid accumulation, and activating phytohormone signaling pathways (Mcdowell et al., 2008; Lee and Luan, 2012; Danquah et al., 2014; Ullah et al., 2018; Xie et al., 2021), which subsequently lead to the change in plant nutritional quality (water content and C/N ratio) as well as plant chemical defenses to insects (English-Loeb et al., 1997; Guo et al., 2016; Castagneyroi et al., 2018; Suarez-Vidal et al., 2019).

Combined effects of elevated CO2 and drought on different host plants and further plant-pest interaction vary (Roth et al., 1997; Nackley et al., 2018). This host plant-species-specific pattern is not surprising and is also found in other combined effects analyses such as combined warming and elevated CO2. Depending on the plant, warming treatment may weaken or strengthen the effect of elevated CO2 treatment (Johns and Hughes, 2002; Murray et al., 2013; Niziolek et al., 2013). However, elevated CO2 routinely promotes stomatal closureand root growth, and prolongs physiological activity, which is proven helpful in withstanding the negative impact of drought stress on dry biomass, water status, and water use efficiency (Wall, 2001; Roy et al., 2016; Li et al., 2017, 2019b; Miranda-Apodaca et al., 2018; Uddin et al., 2018).

Aphids are key economic pests for many crops that cause extensive feeding damage and transmit viruses (Blackman and Eastop, 2000; Züst and Agrawal, 2016). Both elevated CO2 and drought stress indirectly affect insects in two ways, namely, the changes in plant nutritional quality and its resistance to insects (Zavala et al., 2013; Xie et al., 2021). Both ways mediated by phytohormones are important factors affecting aphid feeding, growth, and population size (Sun et al., 2016). As sap-sucking insects, the soluble sugar and free nitrogen assimilation transferred in plant phloem are the main sources of carbon and nitrogen nutrients for aphids (Oehme et al., 2013). Recent studies have revealed that aphid feeding alters the content of phytohormones (e.g. abscisic acid, ABA; Jasmonic acid, JA; salicylic acid, SA), as well as the expression of defense genes (AOC, LOX, PAL, PR-1) related to JA and SA signaling pathways in plant tissues (Guo et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2017). Change in phytohormone content is an important index for plant resistance to aphids, and the expression is generally induced by aphid feeding. These phytohormones' signaling pathways work together to regulate plant defense response to aphids. The resulting induced resistance is common in plants. However, the specific aphid resistance effect varies between species or even genotypes (Kempel et al., 2011; Züst and Agrawal, 2016).

In the growth and development of wheat, elevated CO2 and water stress are two constraints. This, in turn, can alter the metabolic rates, development, and aphids feeding performance. Elevated CO2 increased wheat starch, sucrose, glucose, total non-structure carbohydrates (TNCs), TNC:nitrogen ratio, free amino acids, soluble protein and grain weight, and decreased fructose and nitrogen contents, which further enhanced the grain aphid Sitobion avenae Fabricius population fed on wheat (Chen and Ge, 2004), but decreased fecundity of bird cherry-oat aphid Rhopalosiphum padi (Navarro et al., 2020). Drought stress significantly promoted amino acid accumulation, soluble sugar, and phytohormone contents in wheat, and also increased aphid abundance and population growth rates fed on wheat (Mousa et al., 2019; Cui et al., 2020; Xie et al., 2021). Other research has shown that compared to semiarid and moist area clones, arid area clones of the aphid Sitobion avenae (Fabricius) tended to have longer developmental times and smaller body sizes (Ahammed et al., 2016). However, what the interaction between these two factors is and how it affects the susceptibility of wheat plants to insect attack is still completely occluded.

In the present study, we used a plant-aphid interaction system, namely wheat (Triticum aestivum) and its key pest aphid Sitobion miscanthi, which is widely misreported as S. avenae in China (Zhang, 1999; Jiang et al., 2019), to comprehensively and systematically investigate the combined effects of elevated CO2 and drought stress on wheat nutritional quality and resistance to aphid, as well as how these changes in the host plants affect aphid performance. Results from this study should help to understand the occurrence trend of aphid population on wheat under elevated CO2 and drought, which will subsequently aid in adjusting pest control strategies under the context of future climate change.

The grain aphid isolate S. miscanthi was originally collected from wheat in the Hebei province of China. This isogenic colony was started from a single parthenogenetic female and was maintained on wheat (Triticum aestivum) in the laboratory at 22 ± 1°C, with 75% relative humidity and 16L: 8D photoperiod. To avoid overcrowding, aphids were continuously transferred to new plants until the start of the experiment.

Elevated CO2 conditions were supplied from gas tanks. Ambient CO2 conditions were supplied from the surrounding air entering the environmental chamber facilities. The chambers were maintained at 25 ± 1°C, 60–70% relative humidity, and 14 h light /10 h dark photoperiods with 9000 lx fluorescent lamp active radiation levels. Wheat seeds (variety Zhongmai 175) were planted in pots (7.5 cm diameter x 9.0 cm height) with a sterilized loamy field soil (organic carbon content ~75 g kg−1). Each pot was planted with several seeds, and then only one seedling kept for the coming treatments.

Closed-dynamic CO2 chambers (CDCC) were used and the parameters set here mainly followed several classic cases which used CDCC (Chen and Ge, 2004; Guo et al., 2012; Kurepin et al., 2018; Dusenge et al., 2020). Six chambers were employed, and three of them were treated with elevated CO2 (~750 ± 15 ppm), the other three as their controls were maintained at ambient CO2 (~380 ppm). Wheat plants were exposed to the CO2 and drought treatments from germination to the end of the experiment. Forty pots were used for well-watered (80% of field capacity moisture) and drought (40% of field capacity moisture) treatment, respectively, in each chamber. Wheat plants (2-week-old) from half of 40 pots were collected for testing physiological indicators (one leaf each pot) after treatment, and the remaining 20 pots were further treated with aphid infestation. The testing indicators were performed in three replicates. To minimize positional effects, plants were randomly positioned within each chamber daily.

Leaf relative water content (RWC) was measured using the formula RWC (%) = (fresh weight-dry weight)*100/ (turgor weight-dry weight) (Barrs and Weatherley, 1962). Fresh weight (FW) was measured and leaves were cut off to rehydrate in distilled water for 24 h at 15°C in darkness to obtain the weight at full turgor (TW). Leaf dry weight (DW) was obtained after the samples were dried in an oven at 70°C for 48 h.

To quantify soluble sugar and amino acid concentrations in the phloem, phloem exudate from leaves was obtained using the EDTA exudation technique previously described by Tetyuk et al. (2013). For soluble sugar analysis, phloem exudate from leaves and 40% acetonitrile (40 mL) were transferred into volumetric flasks (50 ml), followed by ultrasound extraction for 30 min and dilution with 40% acetonitrile to 50 ml for use as samples. Samples of 20 μL aliquots from each treatment were injected into the HPLC-MS/MS system. Sugars were separated with a Waters BEH Amide column (4.6 mm × 250 mm, 5 μm; Waters Corporation) using 75% acetonitrile as the mobile phase with isocratic elution at a flow rate of 1.0 ml/min. The column was maintained at 30°C. For amino acid analysis, phloem exudates and pure water (60 ml) were transferred into 100 mL volumetric flasks. After ultrasonic extraction for 30 min, the volume was fixed to the scale mark with water. Then, 10 μL aliquots of each sample were injected into the HPLC-MS/MS system. Amino acids were separated using an ACQUITY HSS T3 column (100 mm × 2.1 mm, 1.8 μm; Waters Corporation) under gradient conditions with 5 mM ammonium acetate (A) and acetonitrile (B) as the mobile phases at a 0.3 ml/min flow rate. The gradient program is shown in Supplementary Table S1. The column was maintained at 30°C.

For the phytohormone (ABA, JA, and SA) defense response analysis, the above wheat leaves with and without aphid infection were collected. Twenty-two wingless adults were transferred to wheat leaves for 24 h at the two-leaf stage. Then, all aphids were removed. Leaves without aphid infection were used as control. Samples of leaves (0.2 g) were homogenized by liquid nitrogen. The resulting homogenate and 10 mL of ethyl acetate were transferred into a centrifuge tube, followed by ultrasound extraction for 20 min and centrifugation for 10 min at 20,000 × g. The supernatant was evaporated to dryness under a stream of nitrogen at 40°C, and the final extracts were dissolved in 1 mL of 70% methanol and used as samples for analysis. Then, 10 μL aliquots of the samples were injected into the HPLC-MS/MS system. Phytohormones were separated with an Acquity UPLC® BEH C18 column (2.1 mm. 100 mm 1.7 μm; Waters Corporation) under gradient conditions, using 0.1% formic acid (A) and methanol (B) as the mobile phases, at a flow rate of 0.3 ml min¯1. The gradient program for phytohormone quantification is shown in Supplementary Table S2. The column was maintained at 30°C.

Total RNA was extracted using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and combined with a micro total RNA extraction kit (Tianmo, Beijing, China) following the manufacturer's instructions. The tissues were homogenized with a liquid-nitrogen-cooled mortar and ground with a pestle into a very fine dust. Homogenized tissues were covered with 1 mL of Trizol reagent. RNA degradation and contamination were monitored on 2% agarose gels. RNA purity was checked using a Nanodrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop products, Wilmington, DE, USA). RNA concentration was measured using a spectrophotometer RNA Nano 6000 Assay Kit of the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA). Individual total RNA was isolated and corresponding type cDNA was synthesized using the TRUEscript RT kit (LanY Science & Technology, Beijing, China) following the manufacturing protocol.

When plants were at the two-leaf stage, 20 wingless S. miscanthi adults were transferred to the first leaf (i.e., the oldest leaf) of each plant (Zhang et al., 2017). Plants without aphid feeding were set as control. After feeding for 24 h, all aphids were removed. The relative expressions of four genes in leaves, Lipoxygenase (LOX) and allene oxide synthase (AOS) for the JA-responsive pathway (Liu et al., 2011) and the SA synthesis enzyme gene phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL) and the induced SA marker protein gene pathogenesis-related protein 1 (PR-1) for the SA-responsive pathway (Chen et al., 2009) were determined using RT-qPCR. Actin was used as the internal control and was amplified using the primer sequences described by Liu et al. (2011). Referring to Zhang's primers (Supplementary Table S3, 2017), RT-qPCR was performed on an ABI 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The PCRs were performed in 20-μL reaction volumes that contained 1 μL of cDNA, 0.5 μL each of 10 μmol L−1 forward and reverse primers, 10 μL of 2× SybrGreen qPCR Mastermix, and 8.0 μL of ddH2O under the following thermal cycling conditions: 2 min at 95°C followed by 40 cycles of 10 s at 95°C and 30 s at 60°C.

Wheat plants under the different treatments mentioned above were used to rear aphids in corresponding environmental chambers. Using a camel hair brush, a single newly emerged nymph (<6 h) was placed on the first leaf of each plant (20 aphids in total for each treatment). To prevent the aphids from escaping, the plant was confined in transparent plastic column cages covered with double-deck gauze on top. All indicators were tested in triplicate. To minimize positional effects, plants were randomly positioned within each chamber daily. The above-recorded data was used to construct a life table and obtain the life table parameters (net reproductive rate R0, intrinsic rate of increase rm, generation time T, and finite rate of increase λ). Age-specific reproduction was used to construct a life table (Birch, 1948).

For RT-qPCR, the fold changes in the expression of target genes were computed using the 2−ΔΔCt normalization method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). For the life table parameters, rm was computed using the Euler equation:, where lx is survivorship of the original cohort over the age interval from day x-1 to day x (i.e., pivotal age) and mx is the mean number of offspring produced per surviving aphid during the age interval x (Maia et al., 2000). R0, T, and λ, were calculated as reported by Maia et al. (2000). The effects of elevated CO2 and drought stress on relative water content, soluble sugar content, and free amino acids content as well as aphid life table parameters were tested by two-way ANOVAs (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). The effects of elevated CO2, drought, and aphid infestation on phytohormone (ABA, JA, and SA) content as well as JA- and SA-related gene expression in wheat were tested by three-way ANOVAs. Least significant different (LSD) tests were used to determine if treatment means significantly differed when ANOVAs indicated a factor was significant. For all analyses, P < 0.05 was considered the threshold for statistical significance.

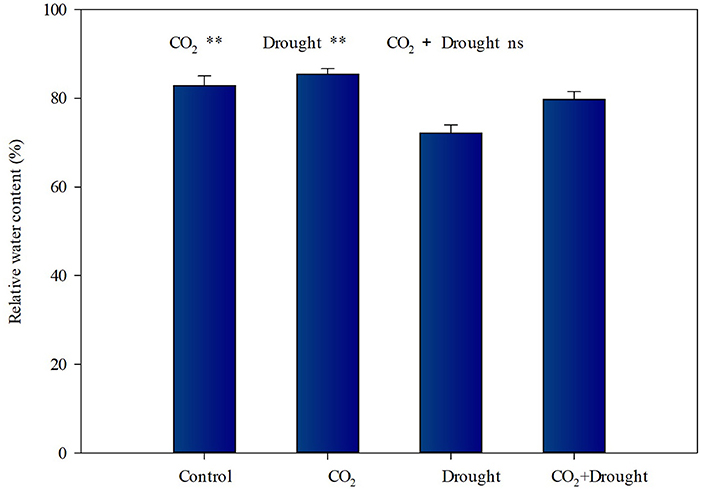

The relative water contents of wheat under elevated CO2 or drought stress vary in opposite ways (Figure 1, Supplementary Table S4). It increased by 6.63% under elevated CO2 conditions (Figure 1), and decreased by 10.9% under drought stress conditions (Figure 1). The interactions between elevated CO2 and drought stress on the relative water content of wheat were not significant (Supplementary Table S4).

Figure 1. Relative water content of Triticum aestivum grown under elevated CO2 and drought conditions. Each value shown represents the mean (±SE) of three replicates. P values are provided for two-way ANOVA on the effects of elevated CO2 and drought treatments on relative water content. Significant differences: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ns, P > 0.05.

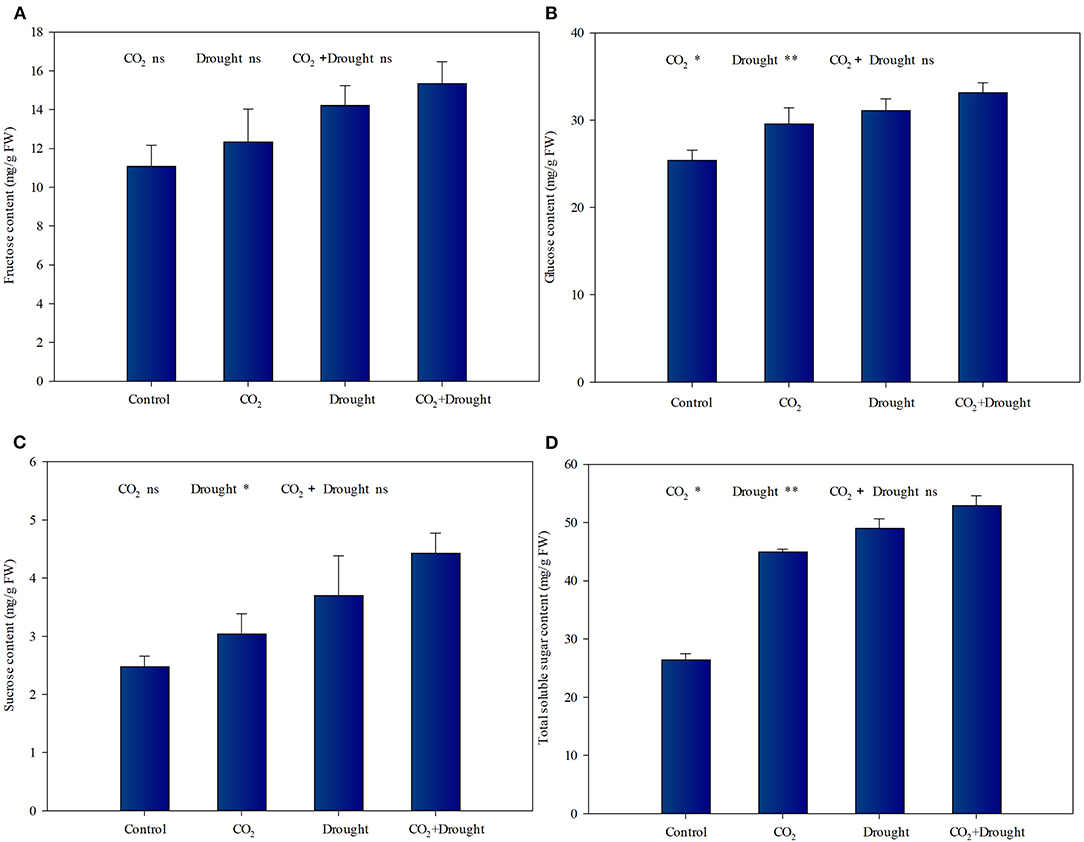

Elevated CO2 and drought stress significantly promoted soluble sugar accumulation in wheat (Figure 2, Supplementary Table S5). Relative to the ambient CO2 treatment, both the glucose and total soluble sugar content increased under elevated CO2 conditions (Figures 2B,D). Meanwhile, Relative to the well-watered treatment, the fructose, glucose, sucrose, and total soluble sugar content increased in wheat under drought stress (Figures 2A–D). The interaction effects between elevated CO2 and drought stress on soluble sugars in wheat were not significant (Supplementary Table S5).

Figure 2. Soluble sugars content of Triticum aestivum grown under elevated CO2 and drought conditions. (A) fructose; (B) glucose; (C) sucrose; (D) total soluble sugars. Each value shown represents the mean (±SE) of three replicates. P-values are provided for two-way ANOVA on the effects of elevated CO2 and drought treatments on soluble sugar content. Significant differences: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ns, P > 0.05.

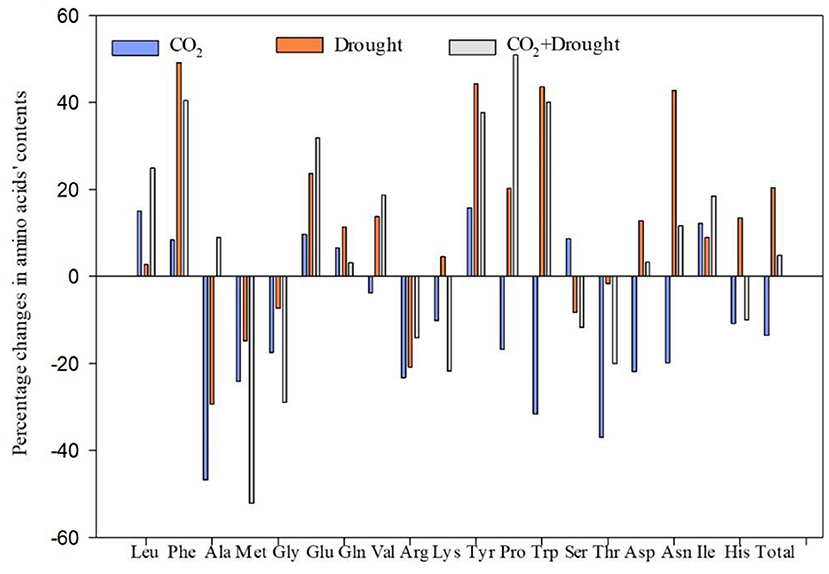

Nineteen amino acids in wheat were quantified (Figure 3, Supplementary Table S6). The effects of elevated CO2 and drought stress on amino acid accumulation in wheat were different and some indicators even show opposite trends. Elevated CO2 significantly decreased the Met, Gly, Lys, Try, Thr, Asp, His, and total amino acid content compared to ambient CO2 treatment (Supplementary Table S6). Drought stress significantly increased the Phe, Glu, Tyr, Pro, Try, Asp, Asn, and total amino acid content, compared to the well-watered treatment (Supplementary Table S6). Furthermore, it showed significantly negative interaction effects between elevated CO2 and drought stress on three amino acids including alanine and tryptophan (Supplementary Table S6).

Figure 3. Percentage changes in amino acid content of Triticum aestivum grown under elevated CO2 and drought conditions. Percentage change value (%) = (treatment-control)*100/control.

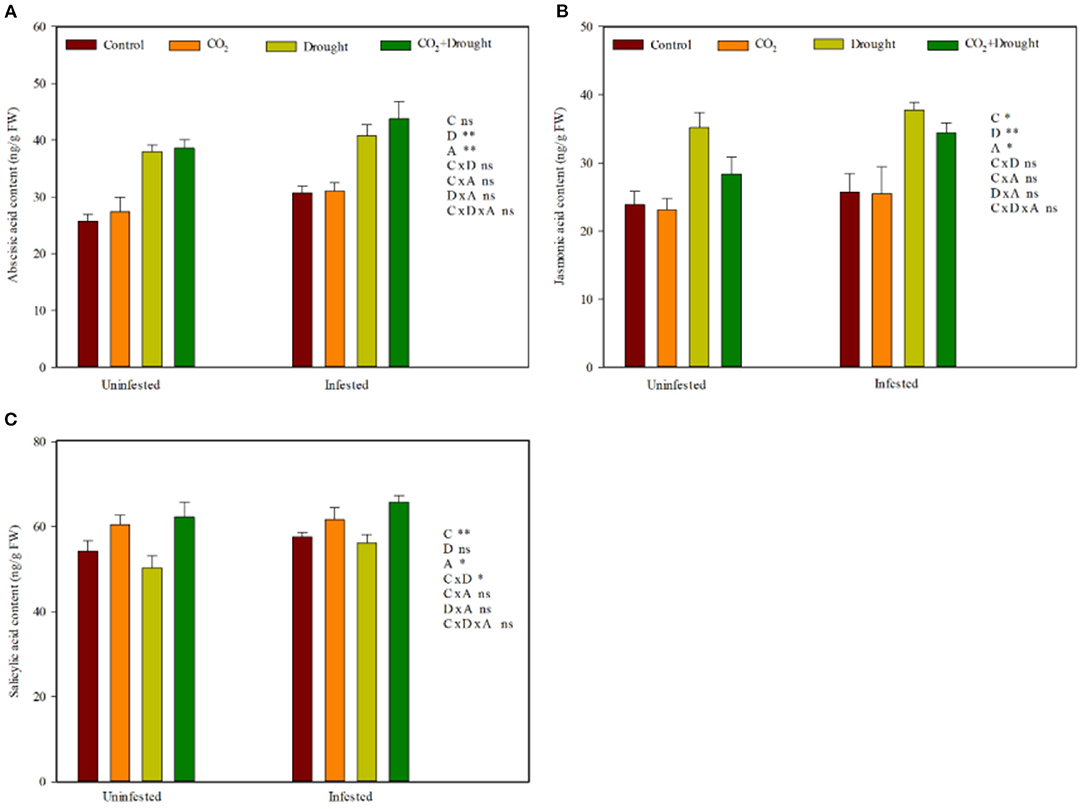

Elevated CO2, drought stress, and aphid infestation significantly influenced the wheat phytohormone content (Figure 4, Supplementary Table S7). Relative to the ambient CO2 treatment, elevated CO2 decreased JA, but increased SA content (Figures 4B,C). Relative to the well-watered treatment, drought stress increased ABA and JA content (Figures 4A,B). Aphid infestation significantly increased ABA, JA, and SA content in wheat compared with control (the uninfested wheat) (Figures 4A–C). Moreover, the interaction effects among elevated CO2, drought stress, and aphids infestation on wheat phytohormones were all not significant (Supplementary Table S7).

Figure 4. Phytohormone content of Triticum aestivum grown under elevated CO2 and drought conditions with and without aphid infestation. (A) abscisic acid; (B) jasmonic acid; (C) salicylic acid. Each value shown represents the mean (±SE) of three replicates. P-values are provided for three-way ANOVA on the effects of elevated CO2 (C), drought (D), and aphid (A) treatments on phytohormone content. Significant differences: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ns, P > 0.05.

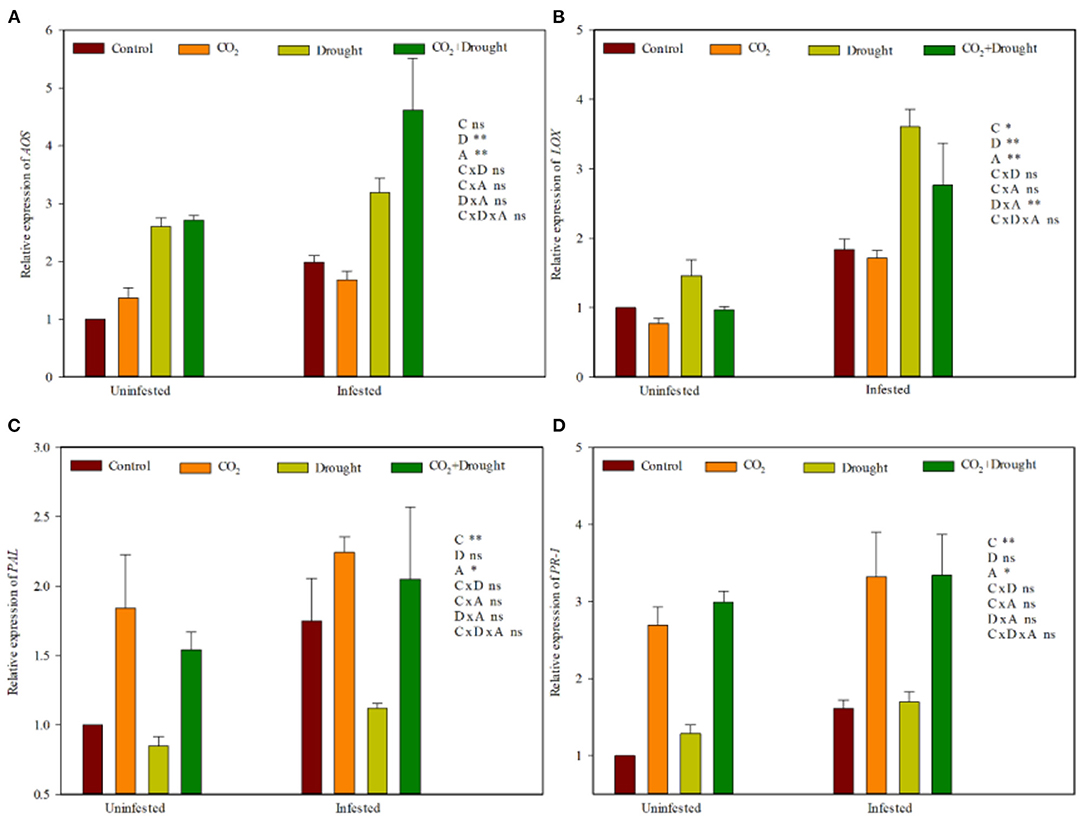

Furthermore, two genes from each plant hormone defense response pathway (JA and SA) in response to aphid induction in wheat were quantified by RT-qPCR. Elevated CO2, drought stress and aphid infestation significantly influenced the relative expression of four defense-related genes (Figure 5, Supplementary Table S8). LOX (JA) was down-regulated, and PR-1, as well as PAL (SA), were up-regulated in wheat grown under elevated CO2 (Figures 5B–D). Relative to the well-watered treatment, the relative expressions of AOS (JA) and LOX (JA) were up-regulated in wheat grown under drought stress (Figures 5A,B). Aphid infestation up-regulated the relative expression of AOS, LOX (JA), PAL, and PR-1 (SA) in wheat, compared to control (the uninfested wheat) (Figures 5A–D). Three factors as well as any two among the three factors analyzed on four gene expressions showed no interaction effect except drought stress and aphid infestation on LOX which showed a significantly positive interaction effect (Supplementary Table S8).

Figure 5. JA- and SA-related gene expression of Triticum aestivum grown under elevated CO2 and drought conditions with and without aphid infestation. (A) allene oxide synthase (AOS); (B) Lipoxygenase (LOX); (C) phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL), (D) pathogenesis-related protein 1 (PR-1). Each value shown represents the mean (±SE) of three replicates. P-values are provided for three-way ANOVA on the effects of elevated CO2 (C), drought (D), and aphid (A) treatments on JA- and SA-related gene expression. Significant differences: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ns, P > 0.05.

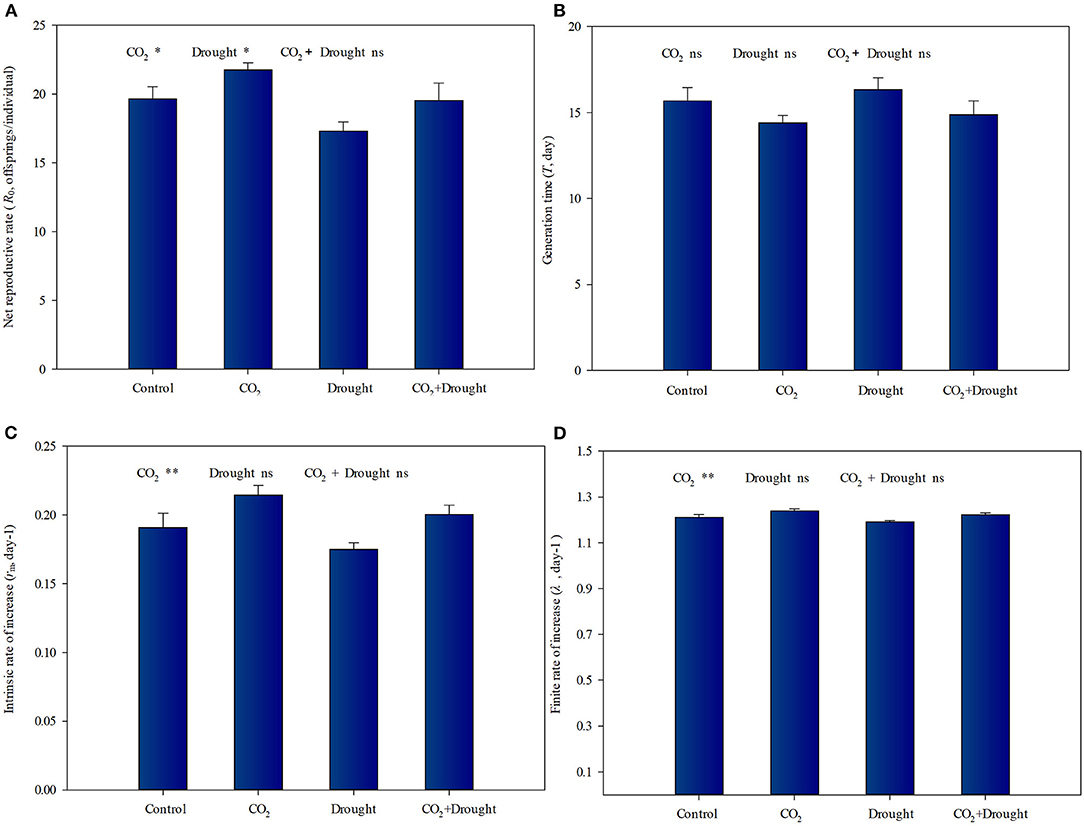

There are contrasting effects of elevated CO2 and drought stress on the life table parameters of aphids fed on wheat (Figure 6, Supplementary Table S9). Under elevated CO2, the R0, r, and λ values of aphid populations increased by 10.6, 13.1, and 2.5%, respectively, compared to control (ambient CO2) (Figures 6A,C,D). The R0 values of aphid populations decreased by 12.4% under drought stress compared to the well-watered treatment (Figure 6A). The interaction effects between elevated CO2 and drought stress on the aphid life table parameters were not significant (Supplementary Table S9).

Figure 6. Life table parameters of aphid reared on Triticum aestivum grown under elevated CO2 and drought conditions. (A) net reproduction rate (R0); (B) generation time (T); (C) intrinsic rate of increase (rm); (D) finite rate of increase (λ). Each value shown represents the mean (±SE) of three replicates. P-values are provided for two-way ANOVA on the effects of elevated CO2 and drought treatments on life table parameters. Significant differences: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ns, P > 0.05.

The water content, nutritional quality (soluble sugar, amino acid, etc), and the secondary metabolic defense pathways in host plants are key limiting factors for aphids' growth and development (Douglas, 1993; Bezemer and Jones, 1998; Mewis et al., 2012; Züst and Agrawal, 2016). The effects of many single environmental factors on all the above aspects have been well-documented. It is necessary and interesting to further explore how the combined environmental factors such as elevated CO2 and drought stress work on the aphids' limiting factors as well as further change the plant-aphid interactions.

The Combined Effects of Elevated CO2 and Drought Treatment on Relative Water Content Tend to Balance Out.

Elevated CO2 has been found to induce stomatal closure, which leads to lower evaporative flux density. As a result of decreases in evaporative flux density and increases in net photosynthesis, also found to occur in elevated CO2, plants have often been shown to maintain higher water use efficiencies when grown under elevated CO2 conditions (Barbehenn et al., 2004; Sun et al., 2015). The elevated CO2 also can facilitate the access to sub-soil water by promoting wheat root growth (Li et al., 2017; Uddin et al., 2018). In the present study, we also found that elevated CO2 treatment increased the water content of wheat. Meanwhile, drought stress decreased the water content as expected. Further, there was no significant interaction between these two environmental factors which indicates that their combined effects can be regarded as the simple sum of their single effects. Thus, the similar water contents between control and combined elevated CO2 and drought treatment demonstrated that elevated CO2 alleviates lower water content caused by drought stress.

It has long been recognized that elevated CO2 increases the photosynthetic rate of C3 plants including wheat, and further promotes carbohydrate accumulation (Barbehenn et al., 2004; Chen et al., 2005). La et al. (2019) also indicated that plant sugar accumulation was mainly due to the increased sucrose content with the highest expression of ABA-dependent sucrose signaling genes under drought stress. To be specific, in wheat the enhancements in carbohydrate accumulation of each single factor such as elevated CO2 (Sun et al., 2009) and drought (Xie et al., 2021) have been verified. Also, under certain combined abiotic stresses such as drought and warming up, the increased carbohydrate accumulation had been reported (Zandalinas et al., 2018). Drought stress not only increased the energy accumulation but also coordinated with the activation of specific physiological and molecular responses in growing plants to mitigate the damaging effects of drought (Zandalinas et al., 2018). In the present study, our results supported that each factor of elevated CO2 and drought stress significantly promoted soluble sugar accumulation in wheat.

Lower nitrogen concentration was generally found in the plants grown under elevated CO2 (Zavala et al., 2013). Indeed, in the present study, all tested contents such as Met, Gly, Lys, Try, Thr, Asp, His, and total amino acid content of wheat were decreased under elevated CO2. There have been several explanations for this decline phenomenon. It may be due to enhanced carbohydrates or biomass accumulation in plants grown under elevated CO2 conditions, then the amino acid concentration was diluted (Nie et al., 1995; Smart et al., 2010; Novriyanti et al., 2012). Besides, the elevated CO2 inhibits plant nitrogen assimilation and metabolism (Bloom et al., 2014) and further mechanism study revealed that the reduced activity of nitrate reductase finally coursed the decreased protein and amino acid contents (Dier et al., 2017; Andrews et al., 2019).

On the contrary, drought stress increased the amino acid content in this study. Previous studies have shown that the accumulation of amino acids enhances plant drought stress tolerance by regulating the activation of material metabolism in plants (Suguiyama et al., 2014). Interestingly, three up-regulated amino acids under drought stress in the present study, namely Try, Tyr, and Phe, are located in the downstream of the shikimic acid pathway, which precisely functions to adjust metabolism toward secondary metabolite production and contributes to hormone metabolism in wheat (Tzin and Galili, 2010).

Their opposing effects on total amino acid contents as well as most of the other test amino acids (17 of 19) in wheat of elevated CO2 and drought did not show interaction, except for two amino acids, Ala and Try. The interaction indicated the existence of a potential crosstalk in which they both participate and a more complicated mechanism of change patterns in certain amino acids and proteins under combined elevated CO2 and drought treatment.

Plant response to abiotic and biotic stress commonly through ABA, JA, or SA defense signaling pathways including the accumulation of phytohormone and up-regulated related gene expression (Adie et al., 2007; Danquah et al., 2014; Zandalinas et al., 2016; Gupta et al., 2017), although the regulated process is complicated and difficult to parse. In general, the ABA signaling pathway activity up-regulated the JA signaling pathway but suppressed the SA signaling pathway when plants were grown under abiotic stress. The up-regulated JA further enhanced the effective resistance of host plants to herbivorous insects (Casteel et al., 2008; Zavala et al., 2008; Ahammed et al., 2016; Guo et al., 2016). JA and SA defense-related gene expression (LOX, AOS, PR-1, and PAL) studies showed that infiltration of S. avenae watery saliva in wheat leaves induced the JA and SA-dependent defense (Zhang et al., 2017).

Elevated CO2 weakens the effective resistance of wheat to aphids by altering the phytohormone signal pathways (Guo et al., 2012, 2016; Sun et al., 2013, 2015). In the present study, elevated CO2 down-regulated the expression levels of the JA defense-related gene LOX and further reduced JA accumulation. Meanwhile, it up-regulated the expression levels of the SA defense-related genes PR-1 and PAL and further increased SA accumulation, which indicated that elevated CO2 weakeed the resistance of wheat.

Drought stress enhanced ABA accumulation and promoted the activity of key enzymes from JA signaling pathway and therefore increased the resistance against aphids in wheat. In the present study, drought stresses up-regulated the expression of LOX and AOS from the JA pathway in wheat and increased ABA and JA accumulation, which showed that drought stress strengthens the resistance of wheat.

Moreover, aphid infestation always up-regulated the JA and SA signaling pathways by increasing JA and SA accumulation and their defense-related genes (LOX, AOS, PR-1, and PAL) regardless of the elevated CO2 and drought conditions in the present study (Supplementary Tables S6, 7).

In summary, the wheat resistance to aphids produced by phytohormone under elevated CO2, drought stresses, or aphid infestation is quite different. But the combined effects among all three factors tended to beindependent, and there was no interaction at all.

Higher host plant water availability enhances aphid feeding efficiency (Sun et al., 2015; Guo et al., 2016). However, aphid response varied to the increasing soluble sugar in their host plants. Some reports have suggested that the increasing soluble sugar content in host plants is beneficial to aphid feeding (Li et al., 2019a). However, others showed that increased soluble sugar content is not necessarily conducive to aphid growth (Slosser et al., 2004; Alkhedir et al., 2013).

Aphids utilize a food source rich in carbohydrates but relatively low in nitrogen. Even so, they must obtain some essential amino acids such as Leu, His, Lys, etc from their host (Chen et al., 2005). Thus, the nitrogen concentration of the host is commonly a limiting nutritional factor for aphids, as reflected in the strong correlations between this variable (nitrogen concentration of wheat) and the individual performance of aphids (Sandström and Pettersson, 1994; Hansen and Moran, 2011). Other literature further shows that the decline of amino acid content enhanced aphid ingestion efficiency which was driven by their instinct for nitrogen (Chen et al., 2005; Sun et al., 2009). Our work here supported the above ideas. Considering the increased soluble sugar accumulation and decreased total amino acid content of wheat under elevated CO2, the improved indicators such as R0, r, and λ values of aphid populations could benefit from the resulting increased feeding effectiveness. Besides, the increased water content also enhanced aphid feeding efficiency, which together with weakened JA-dependent defense for aphids explained why elevated CO2 improved the occurrence of aphid populations in wheat.

However, the R0 value of aphid populations decreased when they fed on wheat grown under drought stress. The decreased fecundity may be relative to the lower water content reducing aphid feeding efficiency and higher JA-dependent defense in wheat grown under drought stress, although drought increased the soluble sugar and amino acid accumulation in wheat. At the same time, the existing studies also showed that the increased JA and SA content enhanced the accumulation of sugars and amino acids in plants (Ilyas et al., 2017; Zhao et al., 2021). Thus, both the accumulation of phytohormone and substances may contribute to the stress resistance (drought and aphid) of wheat in this study, which could be explained through further experiment.

Although each of the two factors significantly influenced wheat water contents, nutritional quality, and phytohormone-dependent defense, further indirectly influencing the performance of aphids significantly, the combined effect on the aphid life table parameters was not significant. It showed similar aphid performance between control and combined treatment in this study, which suggested that in the case of elevated CO2 and drought stresses, aphid damage will continue.

We concluded that the aphid damage suffered by wheat in the future under combined elevated CO2 and drier conditions tends to maintain the status quo. We further revealed the mechanism by which it happened from aspects of wheat water content, nutrition, and resistance to aphids. It could be necessary to reveal details of the plant-insect interactions from the perspective of multiple environmental factors and species specificity and deepen our understanding of the relationship between pest occurrence and its damage to plants.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

HX and JF conceived the idea and developed research questions. FS, YL, and HX collected and analyzed the data and prepared the original draft. MY, JL, and XY managed the experiment, collected the data, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Research Project for Colleges and Universities in Hebei Province (BJ2020049) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31871966).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2022.853220/full#supplementary-material

Adie, B. A., Pérez, J., Pérez, M. M., Godoy, M., Sánchez, J. J., Schmelz, E. A., et al. (2007). ABA is an essential signal for plant resistance to pathogens affecting JA biosynthesis and the activation of defenses in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 19, 1665–1681. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.048041

Ahammed, G. J., Li, X., Zhou, J., Zhou, Y. H., and Yu, J. Q. (2016). “Role of hormones in plant adaptation to heat stress,” in Plant Hormones Under Challenging Environmental Factors, eds G. Ahammed and J. Q. Yu (Dordrecht: Springer) 1–21. doi: 10.1007/978-94-017-7758-2

Alkhedir, H., Karlovsky, P., and Vidal, S. (2013). Relationship between water soluble carbohydrate content, aphid endosymbionts and clonal performance of Sitobion avenae on cocksfoot cultivars. PLoS One. 8, e54327. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054327

Andrews, M., Condron, L. M., Kemp, P. D., Topping, J. F., Lindsey, K., Hodge, S., et al. (2019). Elevated CO2 effects on nitrogen assimilation and growth of C3 vascular plants are similar regardless of N-form assimilated. J. Exp. Bot. 70, 683–690. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ery371

Barbehenn, R. V., Chen, Z., Karowe, D. N., and Spickard, A. (2004). C3 grasses have higher nutritional quality than C4 grasses under ambient and elevated atmospheric CO2. Glob. Change Biol. 10, 1565–1575. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2004.00833.x

Barrs, H. D., and Weatherley, P. E. (1962). A re-examination of the relative turgidity technique for estimating water deficits in leaves. Aust. J. Biol. Sci. 15, 413–428. doi: 10.1071/BI9620413

Bezemer, T. M., and Jones, T. H. (1998). Plant-insect herbivore interactions in elevated atmospheric CO2: quantitative analyses and guild effects. Oikos 82, 212–222. doi: 10.2307/3546961

Birch, L. C.. (1948). The intrinsic rate of natural increase of an insect population. J. Anim. Ecol. 17, 15–26. doi: 10.2307/1605

Blackman, R. L., and Eastop, V. F. (2000). Aphids on the World's Crops: an Identification and Information Guide. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons Ltd.

Bloom, A. J., Burger, M., Kimball, B. A., and Pinter, P. J. (2014). Nitrate assimilation is inhibited by elevated CO2 in field-grown wheat. Nat. Clim. Change. 4, 477–480. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2183

Castagneyroi, B., Jactel, H., and Moreira, X. (2018). Anti-herbivore defences and insect herbivory: interactive effects of drought and tree neighbours. J. Ecol. 106, 2043–2057. doi: 10.1111/1365-2745.12956

Casteel, C. L., O'Neill, B. F., Zavala, J. A., Bilgin, D. D., Berenbaum, M. R., and Delucia, E. H. (2008). Transcriptional profiling reveals elevated CO2 and elevated O3 alter resistance of soybean (Glycine max) to Japanese beetles (Popillia japonica). Plant Cell Environ. 31, 419–434. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2008.01782.x

Chen, F. J., and Ge, F. (2004). An experimental instrument to study the effects of changes in CO2 concentrations on the interactions between plants and insects-CDCC-1 chamber. Entomol. Knowledge. 41, 279–281.

Chen, F. J., Ge, F., and Parajulee, M. N. (2005). Impact of elevated CO2 on tri-trophic interaction of Gossypium hirsutum, Aphis gossypii, and Leis axyridis. Environ. Entomol. 34, 37–46. doi: 10.1603/0046-225X-34.1.37

Chen, Z., Zheng, Z., Huang, J., Lai, Z., and Fan, B. (2009). Biosynthesis of salicylic acid in plants. Plant Signal Behav. 4, 493–496. doi: 10.4161/psb.4.6.8392

Cui, H., Wang, L., Reddy, G., and Zhao, Z. (2020). Mild drought facilitates the increase in wheat aphid abundance by changing host metabolism. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 114, 79–83. doi: 10.1093/aesa/saaa038

Danquah, A., Zelicourt, D. A., Colcombet, J., and Hirt, H. (2014). The role of ABA and MAPK signaling pathways in plant abiotic stress responses. Biotechnol Adv. 32, 40–52. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2013.09.006

Dier, M., Meinen, R., Erbs, M., Kollhorst, L., and Manderscheid, R. (2017). Effects of free air carbon dioxide enrichment (FACE) on nitrogen assimilation and growth of winter wheat under nitrate and ammonium fertilization. Glob Chang Biol. 24, 40–54. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13819

Douglas, A. E.. (1993). The nutritional quality of phloem sap utilized by natural aphid populations. Ecol. Entomol. 18, 31–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2311.1993.tb01076.x

Dusenge, M. E., Madhavji, S., and Way, D. A. (2020). Contrasting acclimation responses to elevated CO2 and warming between an evergreen and a deciduous boreal conifer. Global Change Biol. 26, 3639–3657. doi: 10.1111/gcb.15084

English-Loeb, G., Stout, M. J., and Duffey, S. S. (1997). Drought stress in tomatoes: changes in plant chemistry and potential nonlinear consequences for insect herbivores. Oikos 79, 456. doi: 10.2307/3546888

Guo, H. J., Peng, X. H., Gu, L. Y., Wu, J. Q., Ge, F., and Sun, Y. C. (2017). Up-regulation of MPK4 increases the feeding efficiency of the green peach aphid under elevated CO2 in Nicotiana attenuata. J. Exp. Bot. 68, 5923–5935. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erx394

Guo, H. J., Sun, Y., Ren, Q., Zhu, S. K., Kang, L., Wang, C. Z., et al. (2012). Elevated CO2 reduces the resistance and tolerance of tomato plants to Helicoverpa armigera by suppressing the JA signaling pathway. PLoS ONE 7, e41426. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041426

Guo, H. J., Sun, Y. C., Peng, X. H., Wang, Q. Y., Harris, M., and Ge, F. (2016). Up-regulation of abscisic acid signaling pathway facilitates aphid xylem absorption and osmoregulation under drought stress. J. Exp. Bot. 3, 681–693. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erv481

Gupta, A., Hisano, H., Hojo, Y., Matsuura, T., Ikeda, Y., Mori, I. Z., et al. (2017). Global profiling of phytohormone dynamics during combined drought and pathogen stress in Arabidopsis thaliana reveals ABA and JA as major regulators. Sci. Rep. 7, 4017. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-03907-2

Hansen, A. K., and Moran, N. A. (2011). Aphid genome expression reveals host-symbiont cooperation in the production of amino acids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Scie. U. S. A. 108, 2849–2854. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013465108

Hervé, J., Koricheva, J., and Castagneyrol, B. (2019). Responses of forest insect pests to climate change: not so simple. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 35, 103–108. doi: 10.1016/j.cois.2019.07.010

Ilyas, N., Gull, R., Mazhar, R., Saeed, M., Kanwal, S., Shabir, S., et al. (2017). Influence of salicylic acid and jasmonic acid on wheat under drought stress. Commun. Soil Sci. Plan. 1–9. doi: 10.1080/00103624.2017.1418370

IPCC. (2014). “Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability”, in Working Group II, Contribution to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on climate Change, 1132, eds. C. B. Field, V. R. Barros, D. J. Dokken, K. J. Mach, M. D. Mastrandrea, and T. E. Bilir (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press) 1–32.

Jiang, X., Zhang, Q., Qin, Y. G., Yin, H., Zhang, S. Y., Li, Q., et al. (2019). A chromosome-level draft genome of the grain aphid Sitobion miscanthi. GiGA Sci. 8:1–8 doi: 10.1093/gigascience/giz101

Johns, C. V., and Hughes, L. (2002). Interactive effects of elevated CO2 and temperature on the leaf-miner Dialectica scalariella Zeller (Lepidoptera: Gracillariidae) in Paterson's Curse, Echium plantagineum (Boraginaceae). Glob. Change Biol. 8, 142–152. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2486.2002.00462.x

Johnson, S. N., Cibils-Stewart, X., Waterman, J. M., Biru, F. N., Rowe, R. C., and Hartley, S. E. (2022). Elevated atmospheric CO2 changes defence allocation in wheat but herbivore resistance persists. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 289, 20212536. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2021.2536

Kempel, A., Schaedler, M., Chrobock, T., and Fischer, M.arkus K. M. (2011). Tradeoffs associated with constitutive and induced plant resistance against herbivory. Proc. Natl. Acd. Sci. U. S. A. 108, 5685–5689. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016508108

Kurepin, L. V., Stangl, Z. R., Ivanov, A. G., Bui, V., Mema, M., Hunter Norman, P. A., et al. (2018). Contrasting acclimation abilities of two dominant boreal conifers to elevated CO2 and temperature. Plant Cell Environ. 41, 1331–1345. doi: 10.1111/pce.13158

La, V. H., Lee, B. R., Islam, M. T., Park, S. H., Lee, H., Bae, D. W., et al. (2019). Antagonistic shifting from abscisic acid- to salicylic acid-mediated sucrose accumulation contributes to drought tolerance in Brassica napus. Environ. Exp. Bot. 162:38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2019.02.001

Lee, S. C., and Luan, S. (2012). ABA signal transduction at the crossroad of biotic and abiotic stress responses. Plant Cell Environ. 35, 53–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2011.02426.x

Li, L. K., Wang, M. F., Pokharel, S. S., Li, C. X., Parajulee, M. N., Chen, F. J., et al. (2019a). Effects of elevated CO2 on foliar soluble nutrients and functional components of tea, and population dynamics of tea aphid, Toxoptera aurantii. Plant Physiol. Bioch. 145, 84–94. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2019.10.023

Li, S., Li, X., Wei, Z., and Liu, F. (2019b). ABA-mediated modulation of elevated CO2 on stomatal response to drought. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 13, 1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2019.12.002

Li, X., Yang, Y. Q., Sun, X. D., Lin, H. M., Chen, J. H., Ren, J., et al. (2014). Comparative physiological and proteomic analyses of poplar (Populus yunnanensis) plantlets exposed to high temperature and drought. PLoS ONE 9, e107605. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107605

Li, Y. F., Li, X., Yu, J. J., and Liu, F. L. (2017). Effect of the transgenerational exposure to elevated CO2 on the drought response of winter wheat: stomatal control and water use efficiency. Environ. Exp. Bot. 136, 78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2017.01.006

Liu, X., Meng, J., Starkey, S., and Smith, C. M. (2011). Wheat gene expression is differentially affected by a virulent Russian wheat aphid biotype. J. Chem. Ecol. 37, 472–482. doi: 10.1007/s10886-011-9949-9

Livak, K. J., and Schmittgen, T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25, 402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262

Maia, A., Luiz, A. J., and Campanhola, C. (2000). Statistical inference on associated fertility life table parameters using Jackknife technique: computational aspects. J. Econ. Entom. 93, 511–518. doi: 10.1603/0022-0493-93.2.511

Mcdowell, N., Pockman, W. T., Allen, C. D., Breshears, D. D., Cobb, N., Kolb, T., et al. (2008). Mechanisms of plant survival and mortality during drought: why do some plants survive while others succumb to drought? New Phytol. 178, 719–739. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02436.x

Mewis, I., Khan, Mohammed, A. M., Glawischnig, E., Schreiner, M., and Ulrichs, C. (2012). Water stress and aphid feeding differentially influence metabolite composition in Arabidopsis thaliana (L.). PLoS ONE 7, e48661. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048661

Miranda-Apodaca, J., Pérez-López, U., Lacuesta, M., Mena-Petite, A., and Muñoz-Rueda, A. (2018). The interaction between drought and elevated CO2 in water relations in two grassland species is species-specific. J. Plant Physiol. 220, 193–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2017.11.006

Mousa, K. M., Gawad, A. A., Shawer, D. M., and Kamara, M. M. (2019). Drought stress and nitrogen fertilization affect cereal aphid populations in wheat fields. J. Plant Protection Pathol. 10, 613–619. doi: 10.21608/jppp.2019.78153

Murray, T. J., Ellsworth, D. S., Tissue, D. T., and Riegler, M. (2013). Interactive direct and plant-mediated effects of elevated atmospheric [CO2] and temperature on a eucalypt feeding insect herbivore. Global Change Biol. 19, 1407–1416. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12142

Nackley, L. L., Betzelberger, A., Skowno, A., West, A. G., Ripley, B. S., Bond, W. J., et al. (2018). CO2 enrichment does not entirely ameliorate Vachellia karroo drought inhibition: a missing mechanism explaining savanna bush encroachment. Environ. Exp. Bot. 155, 98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2018.06.018

Navarro, E. C., Lam, S. K., and Trbicki, P. (2020). Elevated carbon dioxide and nitrogen impact wheat and its aphid pest. Front. Plant Sci. 11, 605337. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.605337

Nie, G. Y., Hendrix, D. L., Webber, A. N., Kimball, B. A., and Long, S. P. (1995). Increased accumulation of carbohydrates and decreased photosynthetic gene transcript levels in wheat grown at an elevated CO2 concentration in the field. Plant Physiol. 108, 975–983. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.3.975

Niziolek, O. K., Berenbaum, M. R., and Delucai, E. H. (2013). Impact of elevated CO2 and increased temperature on Japanese beetle herbivory. Insect Sci. 20, 513–523. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7917.2012.01515.x

Novriyanti, E., Watanabe, M., Kitao, M., Utsugi, H., Uemura, A., and Koike, T. (2012). High nitrogen and elevated [CO2] effects on the growth, defense and photosynthetic performance of two eucalypt species. Environ. Pollut. 170, 124–130. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2012.06.011

Oehme, V., Petra, H., Claus, P. W., and Zebitz, A. F. (2013). Effects of elevated atmospheric CO2 concentrations on phloem sap composition of spring crops and aphid performance. J. Plant Interact. 8, 7484. doi: 10.1080/17429145.2012.736200

Roth, S., Mcdonald, E. P., and Lindroth, R. L. (1997). Atmospheric CO2 and soil water availability: consequences for tree-insect interactions. Can. J. Forest Res. 27, 1281–1290. doi: 10.1139/x97-031

Roy, J., Picon-Cochard, C., Augusti, A., Benot, M.arie, L., Thiery, L., Darosnville, O., et al. (2016). Elevated CO2 maintains grassland net carbon uptake under a future heat and drought extreme. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 113, 6224–6229. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1524527113

Sandström, J., and Pettersson, J. (1994). Amino acid composition of phloem sap and the relation to intraspecific variation in pea aphid (Acyrthosiphon pisum) performance. J. Insect Physiol. 40, 947–955. doi: 10.1016/0022-1910(94)90133-3

Scherber, C., Gladbach, D. J., Stevnbak, K., Karsten, R. J., Schmidt, I. K., Michelsen, A., et al. (2013). Multi-factor climate change effects on insect herbivore performance. Ecol. Evo. 3, 1449–1460. doi: 10.1002/ece3.564

Slosser, J. E., Parajulee, M. N., Hendrix, D. L., Henneberry, T. J., and Pinchak, W. E. (2004). Cotton aphid (Homoptera: Aphididae) abundance in relation to cotton leaf sugars. Environ. Entomol. 33, 690–699. doi: 10.1603/0046-225X-33.3.690

Smart, D. R., Chatterton, N. J., and Bugbee, B. (2010). The influence of elevated CO2 on non-structural carbohydrate distribution and fructan accumulation in wheat canopies. Plant Cell Environ. 17, 435–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.1994.tb00312.x

Suarez-Vidal, E., Sampedro, L., Voltas, J., Serrano, L., and Zas, R. (2019). Drought stress modifies early effective resistance and induced chemical defences of Aleppo pine against a chewing insect herbivore. Environ. Exp. Bot. 162, 550–559. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2019.04.002

Suguiyama, V. F., Silva, E. A., Meirelles, S. T., Centeno, D. C., and Braga, M. R. (2014). Leaf metabolite profile of the Brazilian resurrection plant Barbacenia purpurea Hook. (Velloziaceae) shows two time-dependent responses during desiccation and recovering. Front. Plant Sci. 5, 96. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00096

Sun, Y., Guo, H., and Ge, F. (2016). Plant-aphid interactions under elevated CO2: some cues from aphid feeding behavior. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 502. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00502

Sun, Y., Guo, H., Yuan, L., Wei, J. N., Zhang, W. H., and Ge, F. (2015). Plant stomatal closure improves aphid feeding under elevated CO2. Glob. Change Biol. 21, 2739–2748. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12858

Sun, Y., Guo, H., Zhu-Salzman, K., and Ge, F. (2013). Elevated CO2 increases the abundance of the peach aphid on Arabidopsis by reducing jasmonic acid defenses. Plant Sci. 210, 128–140. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2013.05.014

Sun, Y. C., Jing, B. B., and Ge, F. (2009). Response of amino acid changes in Aphis gossypii (Glover) to elevated CO2 levels. J. Appl. Entomol. 133, 189–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0418.2008.01341.x

Tetyuk, O., Benning, U. F., and Hoffmann, B. S. (2013). Collection and analysis of Arabidopsis phloem exudates using the EDTA-facilitated method. J. Vis. Exp. 80, e51111. doi: 10.3791/51111

Tzin, V., and Galili, G. (2010). New insights into the shikimate and aromatic amino acids biosynthesis pathways in plants. Mol Plant. 3, 956–972. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssq048

Uddin, S., Löw, M., Parvin, S., Fitzgerald, G. J., Tausz-Posch, S., Armstrong, R., et al. (2018). Elevated [CO2] mitigates the effect of surface drought by stimulating root growth to access sub-soil water. PLoS ONE 13, e0198928. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198928

Ullah, A., Manghwar, H., Shaban, M., Khan, A. H., Akbar, A., Ali, U., et al. (2018). Phytohormones enhanced drought tolerance in plants: a coping strategy. Environ. Sci. Pollut. R. 25, 33103–33118. doi: 10.1007/s11356-018-3364-5

Wall, G. W.. (2001). Elevated atmospheric CO2 alleviates drought stress in wheat. Agr Ecosyst. Environ. 87, 261–271. doi: 10.1016/S0167-8809(01)00170-0

Wei, Z. H., Abdelhakim, L. O. A., Fang, L., Peng, X. Y., Liu, J., and Liu, F. L. (2022). Elevated CO2 effect on the response of stomatal control and water use efficiency in amaranth and maize plants to progressive drought stress. Agr. Water Manag. 266, 107609. doi: 10.1016/j.agwat.2022.107609

Xie, H. C., Shi, J. Q., Shi, F. Y., Xu, H. Y., He, K. L., and Wang, Z. Y. (2021). Aphid fecundity and aphid defenses in wheat exposed to a combination of heat and drought stresses. J. Exp. Bot. 71, 2713–2722. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eraa017

Zandalinas, S. I., Balfagon, D., Arbona, V., Gomez, C. A., Inupakutika, M. A., and Mittler, R. (2016). ABA is required for the accumulation of APX1 and MBF1c during a combination of water deficit and heat stress. J. Exp. Bot. 67, 5381–5390. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw299

Zandalinas, S. I., Mittler, R., Balfagón, D., Arbona, V., and Gómez-Cadenas, A. (2018). Plant adaptations to the combination of drought and high temperatures. PhysioL. Plantarum. 162, 2–12. doi: 10.1111/ppl.12540

Zavala, J. A., Casteel, C. L., DeLucia, E. H., and Berenbaum, M. R. (2008). Anthropogenic increase in carbon dioxide compromises plant defense against invasive insects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105, 10631–10631. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800568105

Zavala, J. A., Gog, L., and Giacometti, R. (2017). Anthropogenic increase in carbon dioxide modifies plant-insect interactions. Ann. Appl. Biol. 170, 68–77. doi: 10.1111/aab.12319

Zavala, J. A., Nabity, P. D., and DeLucia, E. H. (2013). An emerging understanding of mechanisms governing insect herbivory under elevated CO2. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 58, 79–97. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-120811-153544

Zhang, G.. (1999). Aphids in Agriculture and Forestry of Northwest China, 1st Edn. Beijing: China Environmental Science.

Zhang, Y., Fan, J., Francis, F., and Chen, J. L. (2017). Watery saliva secreted by the grain aphid Sitobion avenae stimulates aphid resistance in wheat. J. Agr. Food Chem. 65, 8798–8805. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b03141

Zhao, Y., Song, C. C., Brummell, D. A., Qi, S. N., Lin, Q., Duan, Y. Q., et al. (2021). Jasmonic acid treatment alleviates chilling injury in peach fruit by promoting sugar and ethylene metabolism. Food Chem. 338, 128005. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.128005

Keywords: Triticum aestivum, Sitobion miscanthi, elevated CO2, drought, nutritional quality, insect resistance

Citation: Xie H, Shi F, Li J, Yu M, Yang X, Li Y and Fan J (2022) The Reciprocal Effect of Elevated CO2 and Drought on Wheat-Aphid Interaction System. Front. Plant Sci. 13:853220. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.853220

Received: 12 January 2022; Accepted: 08 June 2022;

Published: 14 July 2022.

Edited by:

Durgesh Kumar Tripathi, Amity University, IndiaReviewed by:

Van Hien La, Chonnam National University, South KoreaCopyright © 2022 Xie, Shi, Li, Yu, Yang, Li and Fan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jia Fan, amZhbkBpcHBjYWFzLmNu

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.