- Department of Life Science, Gachon University, Seongnam, South Korea

Understanding of intercontinental distribution in the Northern Hemisphere has attracted a lot of attention from botanists. However, although Orchidaceae is the largest group of angiosperms, biogeographical studies on the disjunctive pattern have not been sufficient for this family. Goodyera R. Br. (tribe Cranichideae, subfamily Orchidoideae, family Orchidaceae) is widely distributed in temperate and tropical regions. Although the phylogenetic relationship of Goodyera inferred from both morphological and molecular data has been conducted, the sampled taxa were mainly distributed in Asia regions that resulted in non-monophyly of this genus. In this study, the complete plastid genomes of Goodyera, generated by next-generation sequencing (NGS) technique and sampled in East Asia and North America, were used to reconstruct phylogeny and explore the historical biogeography. A total of 18 Goodyera species including seven newly sequenced species were analyzed. Based on 79 protein-coding genes, the phylogenetic analysis revealed that Goodyera could be subdivided into four subclades with high support values. The polyphyletic relationships among Goodyera taxa were confirmed, and the unclear position of G. foliosa was also resolved. The datasets that are composed of the 14 coding sequences (CDS) (matK, atpF, ndhK, accD, cemA, clpP, rpoA, rpl22, ndhF, ccsA, ndhD, ndhI, ndhA, and ycf1) showed the same topology derived from 79 protein-coding genes. Molecular dating analyses revealed the origin of Goodyera in the mid-Miocene (15.75 Mya). Nearctic clade of Goodyera was diverged at 10.88 Mya from their most recent common ancestor (MRCA). The biogeographical reconstruction suggests that subtropical or tropical Asia is the origin of Goodyera and it has subsequently spread to temperate Asia during the Miocene. In addition, Nearctic clade is derived from East Asian species through Bering Land Bridge (BLB) during the Miocene. The speciation of Goodyera is most likely to have occurred during Miocene, and climatic and geological changes are thought to have had a part in this diversification. Our findings propose both origin and vicariance events of Goodyera for the first time and add an example for the biogeographical history of the Northern Hemisphere.

Introduction

The intercontinental distribution of plants has been the subject of many botanist's research to date. Since Gray (1846) has investigated the vicariance of plants in Northern Hemisphere, many studies of vicariance and disjunction between East Asia and North America have been conducted till date (Donoghue et al., 2001; Wen et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2017, 2019). According to the studies, occasions such as continental drift and global climatic changes may have caused the fragmentation of the Northern Hemisphere. Wen et al. (2010) found that most temperate lineages had a dominance of directionality from East Asia to North America by identifying 98 lineages with disjunct distribution between two regions. Even though the Orchidaceae is the largest family among angiosperms, the results showed that only one lineage is in the orchid family. Currently, biogeographical analyses have been carried out on orchids (Guo et al., 2012; Givnish et al., 2016; Smidt et al., 2021), but the comprehension of the disjunctive pattern of orchids is still lacking compared to the other groups.

The genus Goodyera R. Br., commonly known as ladies' tresses or jewel orchids, is the widespread genus of the subtribe Goodyerinae (tribe Cranichideae; subfamily Orchidoideae; family Orchidaceae). It consists of about 99 species and is distributed in Asia, North America (including Mexico), Europe, Southern Africa, northeast Australia, Madagascar, and the Pacific Islands; ca. 25 species in Indomalaya realm, 30 species in Palearctic realm, 17 species in New World (mostly Nearctic realm and Mexico), and 15 species in Australasian realm (Chen et al., 2009; Chase et al., 2015; Hu et al., 2016; POWO, 2019). Many species of Goodyera are terrestrial (rarely epiphytic), which grow on moist grounds or mossy rocks of mountains and have characteristics of leaves with white or golden reticulate veins, elongate and creeping rhizome, hoods including dorsal sepal and petals, resupinate flowers, and concave-saccate labellum (Chen et al., 2009; Hu et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2019).

According to Schlechter (1911), Goodyera was divided into two sections: Otosepalum and Goodyera, which were recognized by lateral sepals reflexed and later sepals normally spreading, respectively. The treatment of Schlechter (1911) was followed by many scholars (Seidenfaden, 1978; Seidenfaden et al., 1992; Pearce and Cribb, 2002). On the other hand, different characteristics were found as taxonomic keys such as reticulate venation or marking on the surface of the leaves, rosulate leaves or not, etc. (Lang, 1999; Chen et al., 2009; Hu et al., 2016). Previously, a phylogeny study based on the nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region revealed the monophyly of Korean Goodyera species (Shin et al., 2002). Juswara (2010) used the ITS and two chloroplast loci (trnL-F and rpl16) to clarify the phylogenetic relationships of several Goodyera species and demonstrated the polyphyly of Goodyera. Smidt et al. (2020) compared complete chloroplast sequences and concluded that Goodyera is biphyletic, although the clade was supported with a high value. Although different studies have been conducted, the monophyly of Goodyera in East Asia and North America has not been clarified.

Hu et al. (2016) indicated that Goodyera is divided into four sections with specific distribution: section Goodyera in the Northern Hemisphere, section Otosepalaum in Indomalaya and Australasian realm, section Reticulum in Indomalaya and Palearctic realm, and a new section composed by G. procera in the Indomalaya realm, a result of molecular data including ITS, trnL-F, and matK. This paper only identified these geographical distributions but does not conduct a biogeographical analysis or explanation. Furthermore, the disjunction patterns of Goodyera between East Asia and North America have received the least attention.

In this study, we aim to (1) carry out the plastid genome evolution of Goodyera in terms of sequence variation, and gene content and order inferred from seven newly sequenced genomes and the available sequences on National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI); (2) reconstruct the phylogenetic relationships of the genus Goodyera based on 79 protein-coding genes data; (3) conduct nucleotide diversity to find phylogenetically valuable genes; and (4) investigate the origin and divergence periods of Goodyera species between East Asia and North America using biogeographical analysis.

Materials and Methods

Taxon Sampling and DNA Extraction

Fresh leaf of Goodyera was collected in the field in South Korea or North America and dried directly with silica gel at room temperature until conducting DNA extraction (Supplementary Table S1). In total, 18 Goodyera species (including seven new plastid genomes) and 11 additional related genera of 13 species from GenBank (except for Spiranthes sinensis, of which the plastid genome was sequenced in this study) were used. Voucher specimens were made for all used samples and deposited in the Gachon University Herbarium (GCU) with specific accession numbers. Total extracted DNAs of each sample were extracted using the modified 2X CTAB buffer method (Doyle and Doyle, 1987), checked by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis with ethidium bromide staining and measured the concentration by spectrophotometer (Biospec-nano; Shimadzu).

Genome Sequencing, Assembly, and Annotation

The samples were sequenced using the Illumina MiSeq sequencing system (Illumina, Seoul, Korea) (Supplementary Table S1). The resulting next-generation sequencing (NGS) raw reads from MiSeq were imported and trimmed with a 2% error probability limitation to remove poor quality reads by Geneious 7.1.9 (Kearse et al., 2012). Plastid genome of Goodyera fumata (GenBank accession no. = NC_026773.1) was used as a reference sequence to perform “map to reference” using Geneious 7.1.9 to the isolation of cpDNA reads (Kearse et al., 2012). De novo assembly was implemented to reassemble reads using Geneious 7.1.9 (Kearse et al., 2012). Contigs from the de novo assembly were used as the reference sequences to reassemble raw reads repeatedly until complete the plastome structures were obtained. Gene content and order were annotated using Goodyera fumata (GenBank accession no. = NC_026773.1) as a reference using 80% similarity to identify genes in Geneious, and all transfer RNAs (tRNAs) were confirmed by tRNAscan-SE with default search mode (Chan and Lowe, 2019). Complete circular plastome map was illustrated using OGDraw (Greiner et al., 2019).

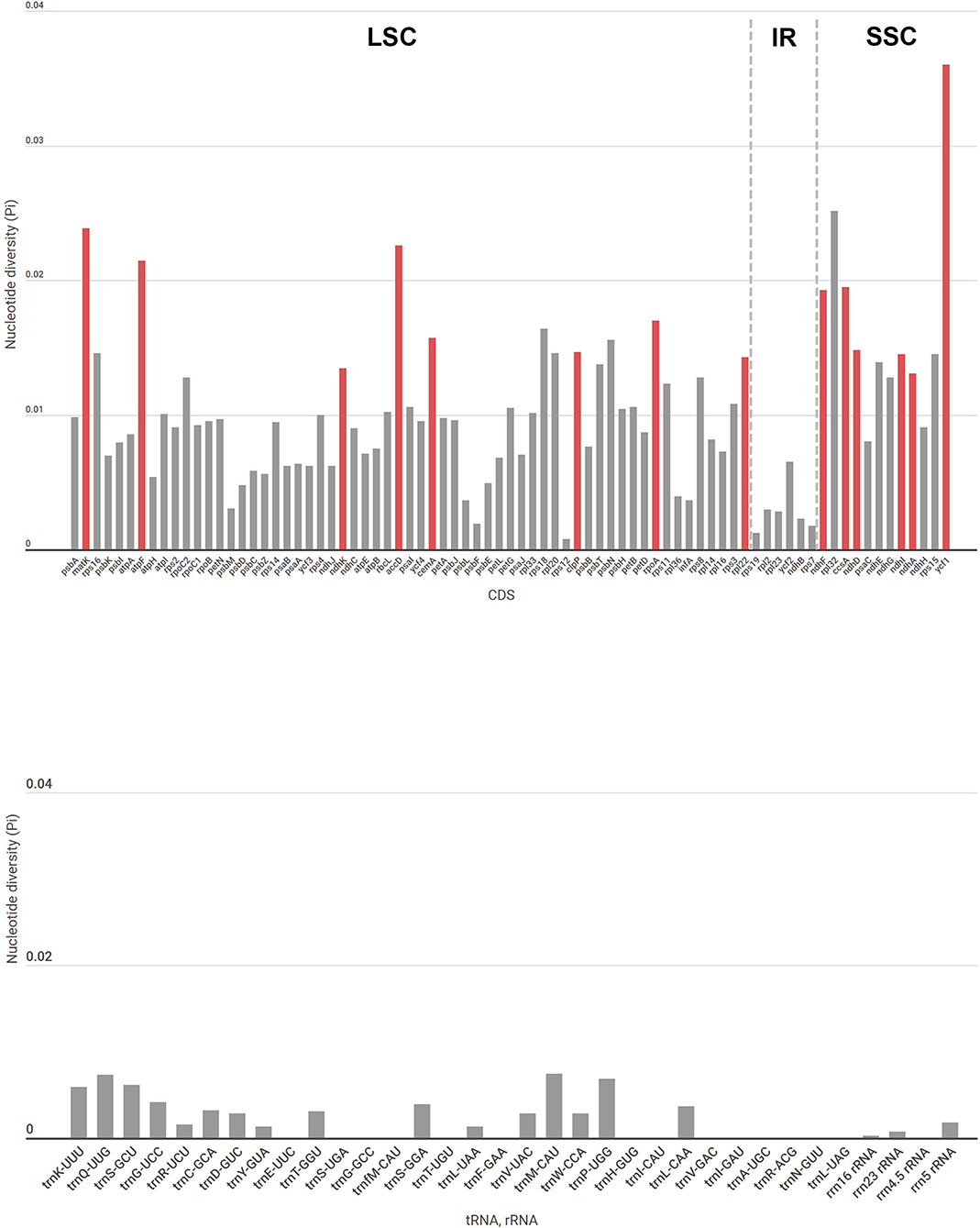

Comparative Genome Analysis

Genome structure, size, and gene contents of 18 Goodyera complete plastid genomes were compared. The GC content was calculated and compared using Geneious. The whole plastid genome sequences of Goodyera species were aligned and compared using mVISTA program in the Shuffle-LAGAN mode (Brudno et al., 2003; Frazer et al., 2004). For the mVISTA plot, we used the annotated cpDNA of Anoectochilus emeiensis as a reference. To find the phylogenetically informative genes, the sliding window analysis using DnaSP v. 6.0 program was used to examine the nucleotide diversity (Pi) of plastid protein-coding genes, transfer RNA genes, and ribosomal RNA genes among the 18 Goodyera species (Rozas et al., 2017). For the sequence divergence analysis, we applied the window size of 100 bp with a 25-bp step size (Supplementary Table S2). The inverted repeat (IR) and single copy (SC) boundaries of the 18 Goodyera species were compared and illustrated using IRscope (Amiryousefi et al., 2018).

Phylogenomic Analysis

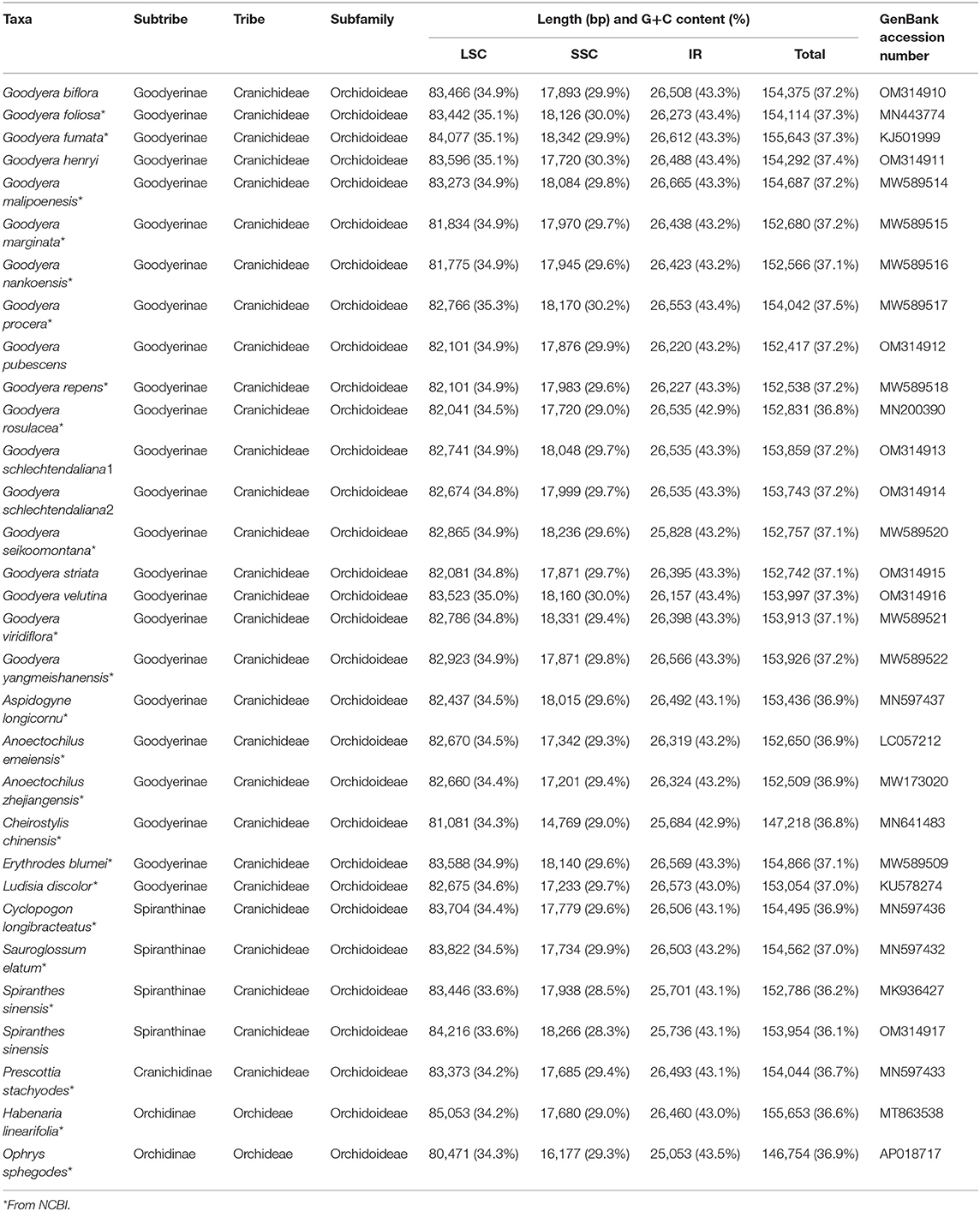

A total of 31 plastid genome sequences were subjected to the phylogenetic study (Table 1). Among them, 23 plastid genome was obtained from NCBI, of which Ophrys sphegodes (GenBank accession no. = AP018717.1) and Habenaria linearifolia (GenBank accession no. = MT863538.1) were used as outgroups (Table 1). For phylogenomic analyses, 79 protein-coding genes were extracted and aligned using the MUSCLE program of Geneious 7.1.9 (Kearse et al., 2012). Gaps were treated as missing data. We performed maximum parsimony (MP), maximum likelihood (ML), and Bayesian inference (BI) based on the combined sequences of 79 protein-coding genes to reconstruct the relationships of Goodyera and related taxa. The MP analyses were conducted in PAUP* v4.0a (Swofford, 2003). All characters equally weighted and unordered. The searches of 1,000 random taxon addition replicates used tree-bisection-reconnection (TBR) branch swapping, and MulTrees permitted ten trees to be held at each step. Bootstrap analyses (PBP, parsimony bootstrap percentages, 1,000 pseudoreplicates) were conducted to examine internal support for individual clades with the same parameters.

Before carrying out the ML and BI analyses, we used jModelTest version 2.1.7 to find the best model with Akaike's information criterion (AIC) (Guindon and Gascuel, 2003; Darriba et al., 2012). The best model for the combined dataset was the GTR+I+G. To carry out the ML searches, the IQ-TREE web server (http://iqtree.cibiv.univie.ac.at/) was used (Trifinopoulos et al., 2016). Support value (MBP, mean bootstrap percentage) was calculated with 1,000 replicates of ultrafast bootstrap (Stamatakis et al., 2008). We used MrBayes v3.2.6 for BI analyses (Ronquist et al., 2012). A total of two simultaneous runs were performed starting from random trees for at least 1,000,000 generations. Then, one tree was sampled for every 1,000 generations. In total, 25% of trees were discarded as burn-in samples. The remaining trees were used to construct a 50% majority-rule consensus tree, with the proportion bifurcations found in this consensus tree given as posterior probability (PP) to estimate the robustness of half of the BI tree. The effective sample size values were then checked for model parameters (at least 200). The phylogenetic trees were modified using FigTree v1.4.4 (Rambaut, 2018).

Molecular Dating Analysis

Based on the phylogenetically useful chloroplast DNA (cpDNA)-coding genes identified by analyzing nucleotide diversity, we used BEAST v.1.8.3 (Drummond and Rambaut, 2007) to estimate the divergence times of Goodyera. The BEAUti interface was used to generate input files for BEAST, in which the GTR+I+R model, Yule speciation tree prior, and uncorrelated lognormal molecular clock model were applied. The Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) analysis was 100 million generations, sampling parameters for every 1,000 generations. After discarding the first 10,000 (10%) trees as burn-in, the samples were summarized in a maximum clade credibility tree in TreeAnnotator v.1.8.3 (Drummond and Rambaut, 2007) using a PP limit of 0.50 and summarizing the mean node heights. The means and 95% higher posterior densities (HPDs) of age estimates were obtained from the combined outputs using tracer. The results were visualized using Figtree v.1.4.4. (Rambaut, 2018).

Age calibration was constrained to the phylogeny of Goodyera and its close relatives. Ramírez et al. (2007) published a pollen fossil dated to 15–20 Mya, Meliorchis caribea S.R.Ramírez, Gravend., R.B.Singer., C.R.Marshall, and N.E.Pierce and resolved its phylogenetic position within the extant subtribe Goodyerinae (subfamily Orchidoideae) based on its morphology. This fossil was used for the calibration point of Goodyerinae with a uniform prior distribution; a lower bound of 15 Mya and an upper bound of 20 Mya (Ramírez et al., 2007; Gustafsson et al., 2010; Iles et al., 2015). To improve the accuracy of calibration, we used an additional secondary calibration point; the crown age of Cranichideae, 42.82 Mya with normal prior distribution (mean = 42, SD = 3.5) following Smidt et al. (2020), from Givnish et al. (2015), who estimated the divergence time of all orchid subfamilies using concatenated nucleotide sequences of three plastid-coding genes (atpB, psaB, and rbcL).

Ancestral Area Reconstruction

The biogeographical data for the Goodyerinae including Goodyera taxa were collected from herbarium specimens and the database (http://www.plantsoftheworldonline.org/, accessed on 20 July 2021) of the Plants of the World Online (POWO, 2019). The distribution range of Goodyerinae was divided into five regions, consisting of (A) Southeast Asia, (B) East Asia, (C) South Asia, (D) North America, and (E) South America. Each species was coded based on the entire range of the species due to the ambiguity of the biogeographical source for the sample from NCBI. The ancestral area reconstruction and the estimation of the spatial patterns of geographic diversification within Goodyera were inferred using the Bayesian binary method (BBM) as implemented in Reconstruct Ancestral State in Phylogenies (RASP v3.1) (Yu et al., 2015). BBM was selected due to its characteristics, which suggests single-distribution areas for ancestral nodes than others and provides the deliberate and instructive results (Müller et al., 2015; Ito et al., 2017; Ha et al., 2018).

For the BBM analysis, we used all post-burn-in trees obtained from the BEAST analysis. The BBM was run using the fixed state frequencies model (Jukes-Cantor) with equal among-site rate variation for 50,000 generations, 10 chains each, and two parallel runs. The consensus tree used to map the ancestral distribution of each node was obtained with the Compute Condense option in RASP from stored trees. The maximum number of ancestral areas was set to five.

Results

Comparative Plastid Genome Structure and Nucleotide Diversity

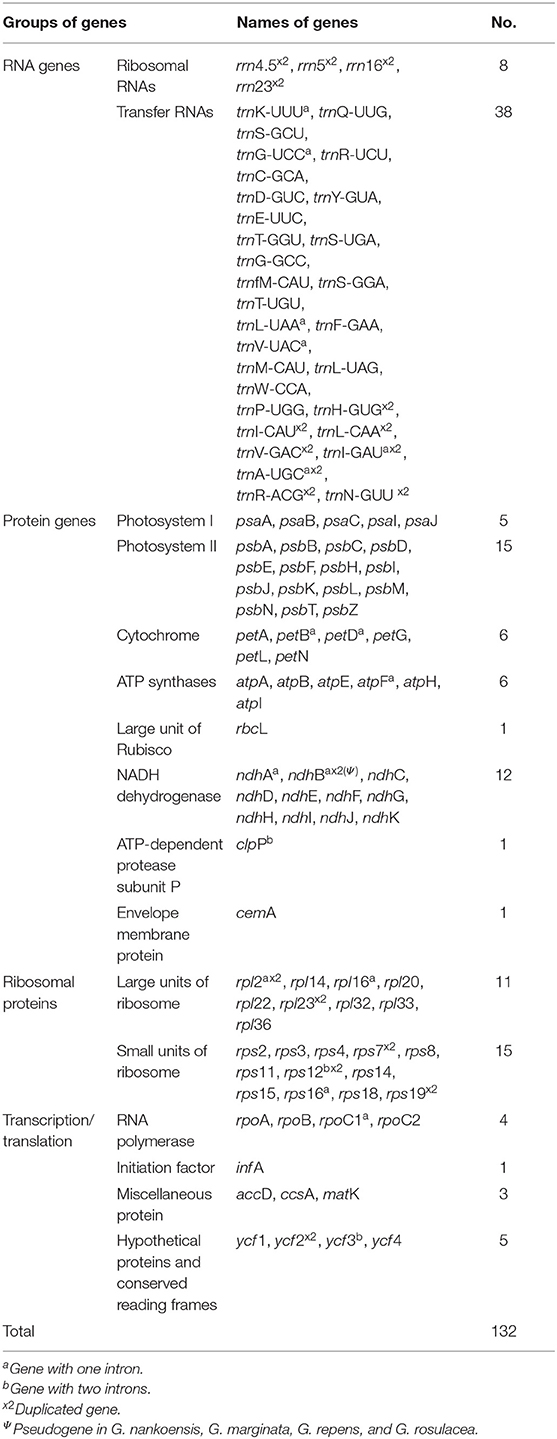

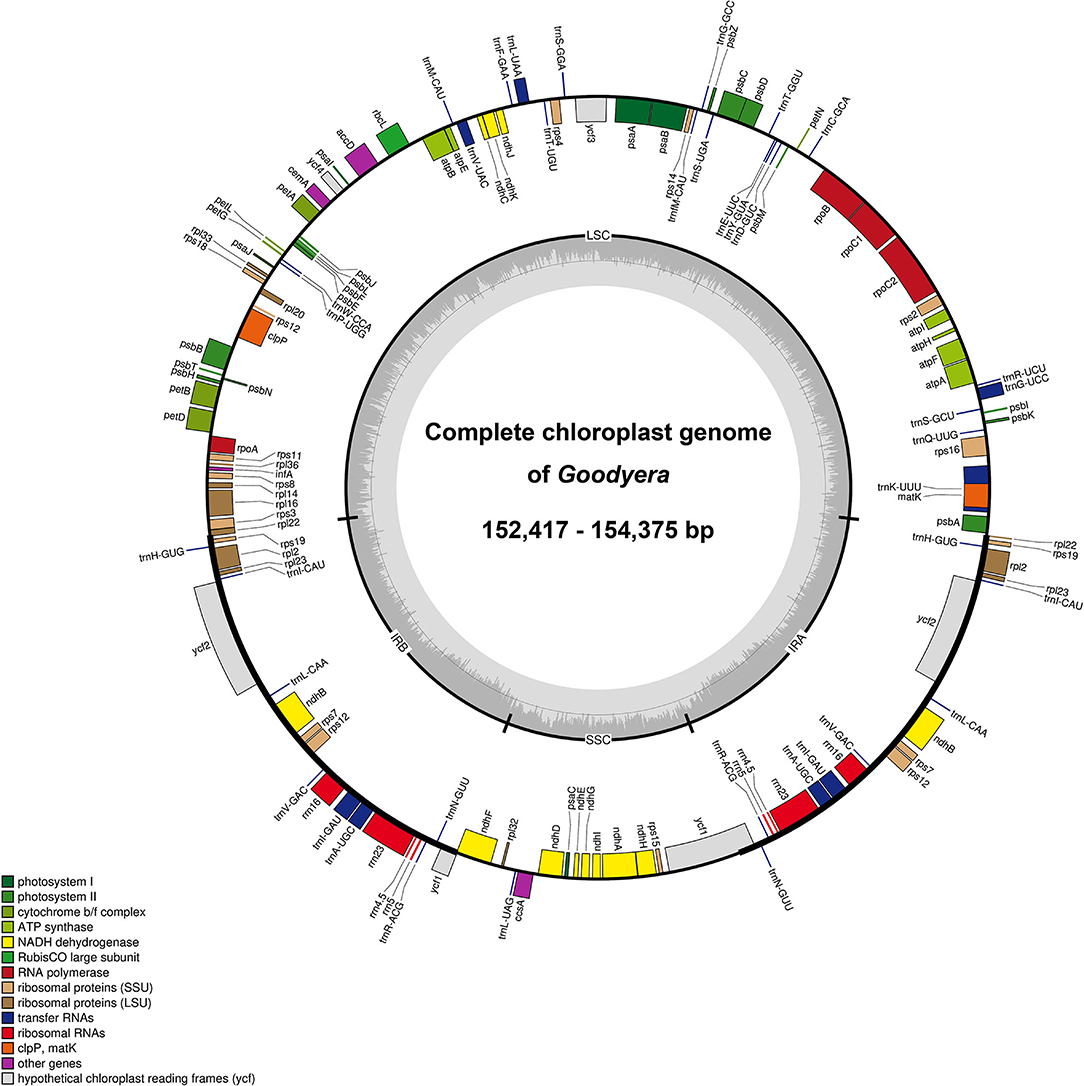

The seven newly sequenced plastomes of Goodyera ranged from 152,417 to 154,375 bp with the typical quadripartite structure (Figure 1 and Supplementary Figure S1). Plastid genome of 18 Goodyera species varied from 152 kb (G. pubescens) to 155 kb (G. fumata) in length with 37.2% of average GC content (Table 1). In Goodyera, G. procera has the highest GC content (37.5%) and G. rosulacea has the lowest GC content (36.8%) (Table 1). Plastid genomes of Goodyera encoded 117 unique genes including 79 protein-coding genes (CDS), 30 tRNA genes, and four ribosomal RNA (rRNA) genes (Table 2). A number of four species (G. nankoensis, G. marginata, G. repens, and G. rosulacea) have a pseudo-ndhB due to point mutation.

Figure 1. Representative plastid genome of Goodyera. The colored boxes represent functional groups of plastid-coding genes. Genes shown inside the circle are transcribed clockwise, whereas genes shown outside the circle are transcribed counter-clockwise. The small gray bar graphs in the inner circle show the GC contents.

Unlike other Goodyera species, G. schlechtendaliana has an inversion (about 1.0 kb) including psbK in the large single copy (LSC) region (Supplementary Figure S2). In comparison with Goodyera species, Aspidogyne longicornu and Erythrodes blumei do not have remarkable differences in sequence variability of the whole plastid genome. The boundaries of the quadripartite structure of the plastid genome were similar among Goodyera species (Supplementary Figure S3). To identify features among the 18 Goodyera plastid genomes, nucleotide divergences of CDS, tRNA, and rRNA were analyzed (Figure 2). In CDS, nucleotide diversity (Pi) has an average of 0.01029. The highest value was 0.03599 (ycf 1), followed by 0.02514 (rpl32) and 0.02387 (matK), whereas the lowest value was 0.00079 (rps12). RNAs have an average of 0.00196 with the Pi values ranged from 0 to 0.00735 (trnQ-UUG). By selecting the datasets of CDS (matK, atpF, ndhK, accD, cemA, clpP, rpoA, rpl22, ndhF, ccsA, ndhD, ndhI, ndhA, and ycf 1) with high values (Pi > 0.013) and over 500 bp in length, we established the phylogenetically useful genes for the Goodyera and confirmed the same topology with aligned 79 plastid protein-coding genes (Supplementary Figure S4).

Figure 2. Nucleotide diversity (Pi) values in protein-coding genes, tRNA, and rRNA in 18 Goodyera species. The dashed lines are the borders of the LSC, IR, and SSC regions. The red bars indicate phylogenetically informative genes with Pi > 0.013 and over 500 bp length in our study.

Phylogenomic Analysis

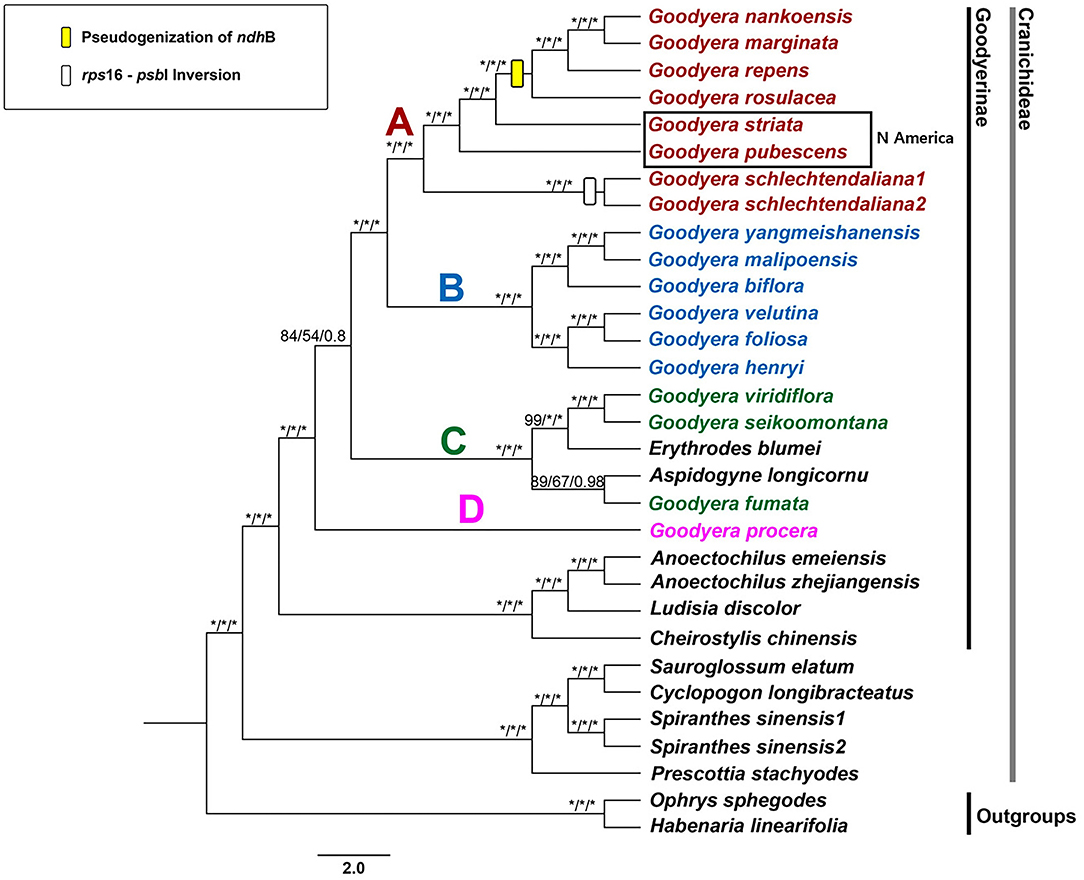

The phylogenetic trees were conducted by maximum parsimony (MP), maximum likelihood (ML), and Bayesian inference (BI) analyses with the data of the concatenated 79 plastid protein-coding genes (71,613 bp). The MP, ML, and BI trees shared the same topology and showed high supports [100% bootstrap (PBP, MBP) values and 1.00 Bayesian posterior probabilities (PP)] in most clades (Figure 3). The genus Goodyera was polyphyletic and subdivided into four subclades A, B, C, and D. Erythrodes blumei was a sister to G. viridiflora and G. seikoomontana (PBP = 99, MBP = 100, PP = 1), and Aspidogyne longicornu was a sister to G. fumata (PBP = 89, MBP = 67, PP = 0.98) (Figure 3). G. procera was a sister to the remaining species of Goodyera (Figure 3). Clade C was shown to be sister to clades A and B with relatively weak support values in all analyses (PBP = 84, MBP = 54, PP = 0.80). Clades A and B formed monophyly with strongly support values (PBP = 100, MBP = 100, PP = 1) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Strict consensus tree from the MP analysis of 31 orchids inferred from 79 plastid protein-coding genes. Numbers indicate support [maximum parsimony bootstrap (PBP)/maximum likelihood bootstrap (MBP)/posterior probability (PP)]. An asterisk (*) indicates that the node has 100% bootstrap or 1.00 posterior probability. The rectangle on the branch indicates the features of the plastome structure.

Divergence Time Estimation

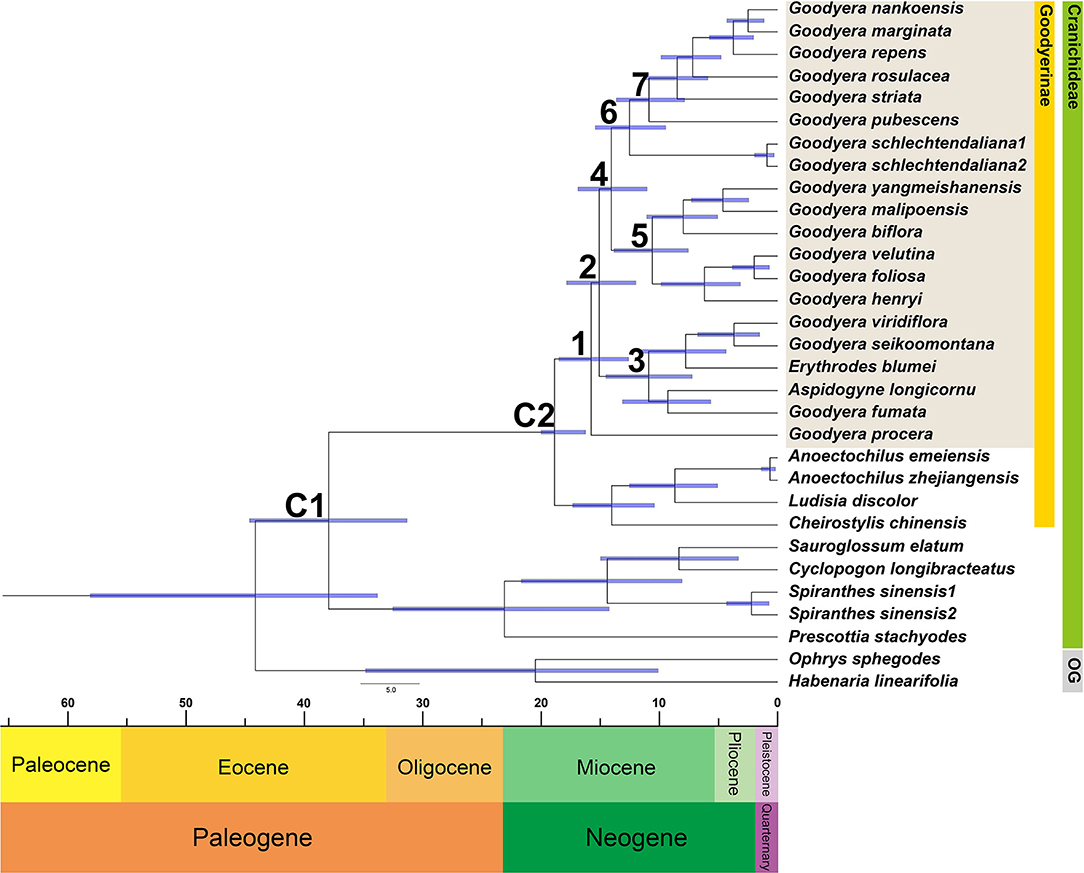

Through nucleotide diversity analysis in this study, 14 genes were selected to create data matric for divergence time estimation. The divergence time of Goodyera was estimated at 15.75 Mya in the mid-Miocene with a 95% HPD range of 12.6–18.49 Mya (node 1; Figure 4 and Table 3). The divergence of Goodyera excluding G. procera was estimated at 15.08 Mya (95% HPD = 11.99–17.83; node 2). The age of clade C (node 3), which comprised of polyphyletic groups from the Indomalesian to East Asia, was estimated at 10.91 Mya (95% HPD = 7.22–14.5 Mya) in the mid-Miocene. Clades A and B were split at 14.05 Mya (11.04–16.88 Mya, 95% HPD; node 4). The age estimate for the crown node of clade B (node 5), which primarily comprised of East Asian species, was dated at 10.59 Mya with a 95% HPD range of 7.55–13.82 Mya. Clade A (node 6) comprised of Goodyera species distributed in diverse continents was estimated at 12.51 Mya (95% HPD = 9.46–15.4 Mya) in the Miocene. Notably, the node 7, which has the distribution of Nearctic region including G. pubescens and G. striata, was diverged at 10.88 Mya (95% HPD = 7.86–13.63 Mya).

Figure 4. Chronogram showing the divergence times estimated in BEAST based on the combined 14 plastid DNA regions. The divergence times of the clades and subclades are shown near each node. Numbers 1–7 indicate nodes of interest (refer to Table 3 for details). Nodes labeled C1 and C2 are the calibration points used in the analysis (for details, refer to the Section “Materials and Methods”). Blue bars represent 95% highest posterior density for the estimated mean dates.

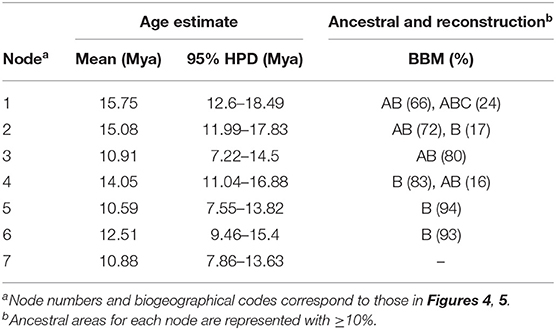

Table 3. Posterior age distributions of major nodes of Goodyera with results of ancestral area reconstruction using BBM analysis.

Ancestral Area Reconstruction

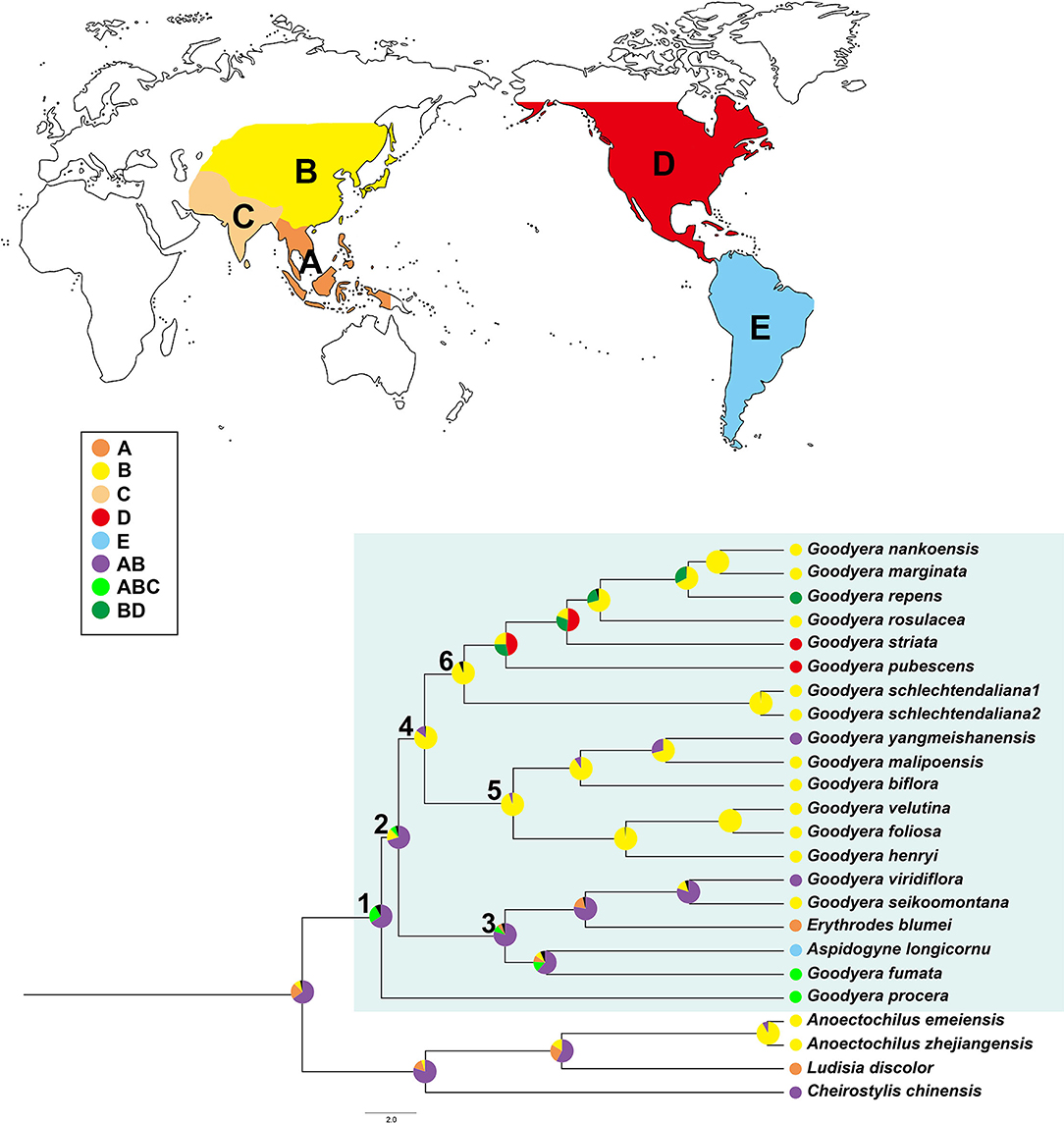

The summary of the ancestral distributions at the node of Goodyera inferred by BBM is shown in Figure 5 and Table 3. The BBM analyses support that Goodyera was originated in Southeast Asia + East Asia (AB), followed by ABC with 66% and 24%, respectively (node 1 in Figure 5). Similar results of origin were obtained for node 2 with 72% and node 3 with 80%, although it included South American species (A. longicornu) and East Asian species. The BBM reconstruction provides that East Asia (B) is the ancestral range for the subclades (node 5 and 6) in node 4 including mainly East Asian and East + Southeastern Asian species. In node 6, which included North American species (G. pubescens and G. striata) and East Asian Goodyera species, the BBM analyses indicated that East Asia (B) is the ancestral area for the subclades.

Figure 5. Summary of Bayesian binary method (BBM) model of ancestral area reconstruction in Goodyera based on a reduced BEAST combined-gene chronogram. The BBM ancestral area reconstructions with the highest likelihood are shown as pes for each clade of Goodyera. Biogeographical regions are used in BBM: A, Southeast Asia; B, East Asia; C, South Asia; D, North America; E, South America. Blue box = Goodyera clade. Numbers 1–6 indicate nodes of interest (for details, refer to Table 3).

Discussion

Characteristics of Plastid Genome in Genus Goodyera

Plastid genomes of Goodyera species have a quadripartite structure consisting of LSC and small single copy (SSC) regions separated by two IR regions (Figure 1). In this study, seven new plastid genomes of the genus Goodyera were completed, and the plastome sizes were 152,417 (G. pubescens) to 154,375 bp (G. biflora) with 37.2% of average GC content (Table 1). In monocot plastomes, unusual structural features happen frequently and provide informative infrageneric relationships. For example, Cyanotinae (Tradescantieae; Commelinaceae) had two large inversions in their plastid genomes, and its characteristics separated the other subtribes (Jung et al., 2021). In orchids such as Cypripedium formosanum and Uncifera acuminata, inversions of the plastid genome were verified (Lin et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2020). In this study, G. schlechtendaliana had one inversion (rps16—psbI), which is the unique feature found in the species (Supplementary Figure S2), and this result corresponds with that of Tu et al. (2021). We propose that AT-rich content of this inversion, which had weak hydrogen bonding, caused structural variations. We also confirmed that inversion sites had a larger proportion of AT contents compared to the average AT content of the LSC region. The GC content value in the LSC region is about 35% (Table 1), and its value in the region where the inversion occurs is about 20%. The IRs dividing LSC and SSC regions have highly conserved structures compared to the single-copy regions (Moore et al., 2007). We identified an IR expansion in members of Goodyera together with Aspidogyne and Erythrodes, but there is no difference in the boundaries of the quadripartite structure (Supplementary Figure S3).

Within Goodyera plastid genomes, four species (G. nankoensis, G. marginata, G. repens, and G. rosulacea) had a pseudogenized ndhB in plastid genomes. The pseudogenization or loss of ndh genes encoding the NAD(P)H-dehydrogenase complex has been found in many Orchidaceae species due to functional copies in the other genomes or redundant. For example, Apostasioideae have intact ndh genes whereas Vanilloideae lost ndh genes. However, some ndh genes are intact or lost in Cypripedioideae, Orchidoideae, and Epidendroideae (Wicke et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2015; Lin et al., 2015; Ruhlman et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2020; Tu et al., 2021). We identified that pseudogenization of ndhB is associated with a specific character of a clade including G. nankoensis, G. marginata, G. repens, and G. rosulacea, which is a potential molecular feature to distinguish members of Goodyera (Figure 3).

To identify the genetic divergence, the nucleotide diversity of CDS, tRNA, and rRNA was calculated among 18 Goodyera plastomes. Due to a highly conserved structure, the IR regions had lower values in nucleotide diversity than single-copy regions (Figure 2). We found a phylogenetically informative CDS dataset composed of 14 genes, which has high values (Pi > 0.013), and over 500 bp length and resulted in the same topology with a 79-aligned CDS dataset with high support value (Supplementary Figure S4).

Phylogenomic and Phylogenetic Relationship Within Genus Goodyera

In contrast to the past phylogeny based on morphological characters, the phylogenetic relationships confirmed the monophyly of Goodyera based on molecular data including plastid, mitochondrial, and nuclear genes since 2000s. Hu et al. (2016) conducted the phylogenetic analysis of Goodyera using plastid and nuclear ribosomal DNA sequences and suggested the division into four sections of Goodyera associated with morphological characters and their distributions. Tu et al. (2021) utilized the whole plastid genome to study the phylogeny of Goodyerinae, especially Cheirostylis and Goodyera clades, and analyzed the plastome structure of Goodyerinae. In this study, we analyzed North American species based on whole plastid protein-coding genes and identified their relationships within Goodyera. In addition, we suggested the possibility that genome structure might be the molecular characters.

We obtained phylogenetic relationships of Goodyera including eight new plastid genomes with two species (G. pubescens and G. striata) distributed in the Nearctic region. Most species of Goodyera were affiliated to high-supported clades except for some clades including the clade C. The genus Goodyera was largely divided into four sections based on the 79 plastid-coding genes (Figure 3).

Clade D is composed of only one species, G. procera, which was a sister to the remainder of Goodyera with high support value (PBP = 100, MBP = 100, PP = 1 in Figure 3), which was corresponded with Tu et al. (2021). Hu et al. (2016) identified that G. procera formed a clade with high support, which has distinctive characters such as narrowly ovate-elliptic leaves or densely non-secund flowers. The position of G. procera is ambiguous to determine due to insufficient species of Goodyera, although that species was identified as the independent clade in this study.

Clade C has been shown as the non-monophyletic clade and a taxonomically debatable group. Erythrodes was affiliated to clade C with the characteristics of no-marking leaves and reflexed lateral sepals based on nuclear ITS, plastid trnL-F, and matK genes (Hu et al., 2016). Chen et al. (2019) and Smidt et al. (2021) defined that clade C is the Microchilus subclade, in which diverse species exist including some Goodyera species. The results of Tu et al. (2021) showed that Aspidogyne was a sister to the rest of clade C, followed by G. fumata, whereas Erythrodes and Goodyera formed a subclade based on plastid-coding genes' dataset. Similarly, our study revealed that Aspidogyne longicornu was a sister to G. fumata and Erythrodes blumei was a sister to G. viridiflora and G. seikoomontana, respectively (Figure 3). Smidt et al. (2021) proposed the combinations of Microchilus s.l. including Aspidogyne, Microchilus, and Kreodanthus based on the results using ITS and matK. However, the 79 CDS datasets revealed the placement of Aspidogyne within Goodyera clade. Therefore, more research should be done to clarify the phylogenetic relationships of those species.

Clade B included six species of Goodyera with strong support value (PBP = 100, MBP = 100, PP = 1) for all nodes in this study (Figure 3). Hu et al. (2016) described this clade as the silver or gold veins and not opened lateral sepals. They referred that G. foliosa formed two clades with G. velutina and G. henryi with high support values, respectively (Hu et al., 2016). In our study, we resolved the complex relationships among them that G. velutina and G. foliosa composed a high-supported clade and G. henryi was a sister to them (Figure 3).

Tu et al. (2021) suggested the combination of clades A and B into one clade; however, Hu et al. (2016) defined them as two sections, sect. Goodyera and sect. Reticulum, which was applied in this study. In our analysis based on 79 aligned plastid-coding genes, clade A included seven species, in which the upper taxon (G. rosulacea, G. repens, G. marginata, and G. nankoensis) has pseudogenized ndhB, which can be used as a synapomorphic feature (Figure 3). Additionally, they have a common character of glabrous inside the labellum, except for G. schlechtendaliana (Hu et al., 2016). All nodes had a strong support value compared to the results of Hu et al. (2016) or Chen et al. (2009).

In this study, a phylogenetic tree based on 79 plastid-coding genes provided phylogenetic relationships of 18 Goodyera species and improved their systematic positions, which were ambiguous in the previous studies. However, to understand the phylogenetic relationships of Goodyera species, more samples of Goodyera are required.

Divergence Time and Biogeographical Origin

Overall, global warming was continued during the Miocene in comparison with the present day. In the mid-Miocene, the temperature was 4–5°C higher than now due to the influence of Mid-Miocene Climatic Optimum (MCO; c. 17 Mya), the global mean surface temperature during peak Miocene warmth (You et al., 2009; Hinsinger et al., 2013; Lawrence et al., 2021). Afterward, a decline in temperature, which is followed from mid- and late Miocene (c. 13 Mya) to Pliocene, triggered an expansion of temperature deciduous trees, grasses, composites, and other herbaceous dicots (Briggs, 1995; Lawrence et al., 2021). There are two situations of angiosperm floras by cooling, drying, and enhanced seasonability in the mid-latitudes; (1) deciduous trees and shrubs became dominant, and (2) monocots and dicots, mainly annual herbs, evolved and diverged (Briggs, 1995; Strömberg, 2011).

To date, some studies have been conducted on the biogeography of Goodyera. Smidt et al. (2021) conducted molecular dating and biogeographical analyses of Goodyerinae based on nuclear ribosomal ITS and plastid matK sequences. Thiv et al. (2021) identified the phylogenetic location of G. macrophylla, which is the sister group to North American species although it is endemic species of Madeira. However, both papers are less reliable in that they used a small number of genes or introns when analyzing them.

Our molecular dating analyses suggest that the genus Goodyera was divaricated in the mid-Miocene (15.75 Mya, ±12.6–18.49) based on 14 plastid protein-coding genes (Figure 4 and Table 3), which was similar to the report of Smidt et al. (2021). Additionally, it originated in East + Southeast Asia, tropical or subtropical Asia including Indomalaya realm (Figure 5 and Table 3). G. procera (forming clade D) and clade C including other genera are distributed in subtropical or tropical Asia except for A. longicornu in South America and diverged c. 15.75 Mya and c. 10.91 Mya, respectively (Figure 4). We expect their most recent common ancestor (MRCA), which was distributed in a tropical or subtropical area and migrated to temperate Asia to survive against the rising temperature due to MCO. Smidt et al. (2021) proposed the Neotropical clade including Aspidogyne in Goodyerinae diverged c. 11 Mya and derived from Indomalayan ancestors, but our study lacked the Neotropical species in Goodyerinae and focused on the genus Goodyera, so further research is needed. Clades A and B ranged from tropical Asia to East Asia as discussed by Hu et al. (2016), diverged c. 12.51 Mya and c. 10.59 Mya at mid-Miocene, respectively (Figure 4). Specifically, clade A included North American species (G. striata and G. pubescens) and they diverged at 10.88 Mya (95% HPD = 7.86–13.63 Mya) in comparison with c. 8.4 Mya of Smidt et al. (2021) (Figure 4). The diversification of Goodyera mainly occurred in 14 Mya, when the temperature began to decrease, which is similar to the result of Briggs (1995). Although there are no significant differences between the two studies, the gaps are likely to happen as the result of the different calibration points or the number of genes. Our dataset provided a reliable value of the genus because 14 phylogenetically informative coding genes of plastid were used, compared to the use of a single matK and ITS by Smidt et al. (2021). Consequently, it is conjectured that the MRCA of Goodyera species migrated from tropical Asia to temperate Asia due to MCO and divided into different lineages as the temperature began to decrease during Miocene.

Intercontinental Disjunctions Between East Asia and North America in Genus Goodyera

Many researches about the biogeographical origin of diverse plants between East Asia and North America have been carried out based on molecular data (Donoghue et al., 2001; Wen et al., 2010, 2016; Kim et al., 2017, 2019). Wen et al. (2010) found that most temperate lineages had a dominance of directionality from East Asia to the North America by identifying 98 lineages with disjunct distribution between two regions: more than half of the lineages were confirmed to migrate from the Old World to the New World. In Cenozoic Era, there is a land bridge connecting continents, which is a migration route of Northern Hemisphere flora: one is the Bering Land Bridge (BLB) and the other is the North Atlantic Land bridge (NALB) (Wen et al., 2010; Deng et al., 2015, 2018; Kim et al., 2019). During the early Paleogene, the NALB, which extended across North America and Greenland to North-eastern Europe, is known as the main migration route for tropical taxa (Tiffney, 1985a; Tiffney and Manchester, 2001). On the other hand, the BLB, from Paleocene to Miocene, is considered as a connection between Asia and North America, which is a crucial route for the extension of temperate taxa (Tiffney, 1985b; Gladenkov et al., 2002).

Our BBM reconstruction suggests East + Southeast Asia as the ancestral area of Goodyera (Figure 5 and Table 3). Therefore, we suggest Goodyera most likely migrated from East Asia to North America via the BLB in the Miocene (Figure 5). Their MRCA remained in East Asia although several species were transferred to North America and then occurred the speciation in each location.

Conclusion

Our study provides eight newly assembled plastid genomes of Goodyera R. Br. Additionally, an evolutionary framework to evaluate the systematic and biogeographical history of Goodyera was conducted. Unlike the previous studies, which mainly focused on species distributed in East Asia, this study conducted a phylogenomic study for the first time including North American species as well. Based on the plastid sequences, two abnormal structures of the plastid genomes in Goodyera have been revealed: an inversion in the LSC region of G. schlechtendaliana and a pseudogenization of ndhB gene in G. nankoensis, G. marginata, G. repens, and G. rosulacea. The phylogenetic analyses using the combined 79 protein-coding genes revealed that Goodyera is polyphyletic and can be divided into four sections with high support corresponding to some morphological characters. Furthermore, we resolved the phylogenetic relationships between unresolved species, suggesting further studies on the phylogeny of Goodyera by adding more samples and molecular data. Through the nucleotide diversity analysis, we found a phylogenetically informative dataset of 14 genes that resulted in same topology of phylogenetic tree to 79 plastid-coding datasets. Divergence time estimation and biogeographical analysis revealed that the common ancestors of all Goodyera species came from the tropical or subtropical Asia including Indomalaya realm in Miocene. In addition, we suggest East Asia as the major center of origin for taxa occurring in East Asia and North America, assuming the Bering Land Bridge played an important part in the migration in Goodyera between East Asia and North America. Our study added an example of the migration in the biogeographical history of the Northern Hemisphere.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found at: National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) BioProject database under accession numbers OM314910 - OM314917.

Author Contributions

J-HK conceived and designed the experiments and revised the draft. J-HK and T-HK collected the plant materials. T-HK performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the draft. All authors agreed on the contents of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the Gachon University research fund of 2019 (GCU-2019-0821) and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) Grant Fund (NRF-2017R1D1A1B06029326).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate Dr. Kenneth M. Cameron at University of Wisconsin–Madison (United States of America), Dr. Gerardo A. Salazar at Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (Mexico), Dr. Changkyun Kim at Honam National Institute of Biological Resources (South Korea), Joonhyung Jung at Gachon University (South Korea) for collecting the plant material for this study, and Dr. Changkyun Kim, Dr. Do Hoang Dang Khoa at NTT Hi-Tech Institute, Nguyen Tat Thanh University (Vietnam) for the valuable comments on the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2022.850170/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Figure S1. Complete plastid genome maps of Goodyera species and Spiranthes sinensis. Genes shown inside the circle are transcribed clockwise, and outside are counterclockwise. Genes belonging to different functional groups are colored. The inner circle shows the LSC, SSC, and IR regions. The darker gray in the inner circle corresponds to GC content, and the lighter gray corresponds to AT content.

Supplementary Figure S2. The alignment of plastid genome sequences based on mVISTA. Plots of percent sequence identity of the plastid genomes of 20 Goodyera clade species with Anoectochilus emeiensis as a reference. The percentage of sequence identities was estimated, and the plots were visualized in mVISTA. CDS means coding sequences and CNS means non-coding sequences.

Supplementary Figure S3. Comparisons of LSC, SSC, and IR regions boundaries between 20 species of Goodyera clade.

Supplementary Figure S4. The maximum likelihood tree of 31 orchids inferred from 14 plastid protein-coding gene datasets. Numbers indicate support [maximum parsimony bootstrap (PBP)/maximum likelihood bootstrap (MBP)]. An asterisk (*) indicates the node has 100% bootstrap.

Supplementary Table S1. List of samples for total DNA extraction and assembly information.

Supplementary Table S2. Nucleotide diversity (Pi) of 18 Goodyera species.

References

Amiryousefi, A., Hyvönen, J., and Poczai, P. (2018). IRscope: an online program to visualize the junction sites of chloroplast genomes. Bioinformatics 34, 3030–3031. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty220

Brudno, M., Do, C. B., Cooper, G. M., Kim, M. F., Davydov, E., Green, E. D., et al. (2003). LAGAN and Multi-LAGAN: efficient tools for large-scale multiple alignment of genomic DNA. Genome Res. 13, 721–731. doi: 10.1101/gr.926603

Chan, P. P., and Lowe, T. M. (2019). tRNAscan-SE: searching for tRNA genes in genomic sequences. Methods Mol. Biol. 1962, 1–14. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-9224-9

Chase, M. W., Cameron, K. M., Freudenstein, J. V., Pridgeon, A. M., Salazar, G., Van den Berg, C., et al. (2015). An updated classification of Orchidaceae. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 177, 151–174. doi: 10.1111/boj.12234

Chen, S.-C., Lang, K.-Y., Gale, S. W., Cribb, P. J., and Ormerod, P. (2009). Flora of China, Vol. 25. St. Louis, MI: Science Press (Beijing) and Missouri Botanical Garden Press.

Chen, S.-P., Tian, H.-Z., Guan, Q.-X., Zhai, J.-W., Zhang, G.-Q., Chen, L.-J., et al. (2019). Molecular systematics of Goodyerinae (Cranichideae, Orchidoideae, Orchidaceae) based on multiple nuclear and plastid regions. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 139, 106542. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2019.106542

Darriba, D., Taboada, G., Doallo, R., and Posada, D. J. (2012). 2: More models, new heuristics and high-performance computing. Nat. Methods 9, 772. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2109

Deng, T., Chen, Y., Wang, H., Zhang, X., Volis, S., Yusupov, Z., et al. (2018). Molecular phylogeny and biogeography of Adenocaulon highlight the biogeographic links between New World and Old World. Fron. Ecol. Evol. 5, 162. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2017.00162

Deng, T., Nie, Z.-L., Drew, B. T., Volis, S., Kim, C., Xiang, C.-L., et al. (2015). Does the Arcto-Tertiary biogeographic hypothesis explain the disjunct distribution of Northern Hemisphere herbaceous plants? The case of Meehania (Lamiaceae). PLoS ONE 10, e0117171. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117171

Donoghue, M. J., Bell, C. D., and Li, J. (2001). Phylogenetic patterns in Northern Hemisphere plant geography. Int. J. Plant. Sci. 162, S41–S52. doi: 10.1086/323278

Doyle, J. J., and Doyle, J. L. (1987). A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochem. Bull. 19, 11–15.

Drummond, A. J., and Rambaut, A. (2007). BEAST: bayesian evolutionary analysis by sampling trees. BMC Evol. Biol. 7, 214. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-214

Frazer, K. A., Pachter, L., Poliakov, A., Rubin, E. M., and Dubchak, I. (2004). VISTA: computational tools for comparative genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, W273–W279. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh458

Givnish, T. J., Spalink, D., Ames, M., Lyon, S. P., Hunter, S. J., Zuluaga, A., et al. (2015). Orchid phylogenomics and multiple drivers of their extraordinary diversification. P. Roy. Soc. B-Biol. Sci. 282, 20151553. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2015.1553

Givnish, T. J., Spalink, D., Ames, M., Lyon, S. P., Hunter, S. J., Zuluaga, A., et al. (2016). Orchid historical biogeography, diversification, Antarctica and the paradox of orchid dispersal. J. Biogeogr. 43, 1905–1916. doi: 10.1111/jbi.12854

Gladenkov, A. Y., Oleinik, A. E., Marincovich, L. Jr., and Barinov, K. B. (2002). A refined age for the earliest opening of Bering Strait. Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl. 183, 321–328. doi: 10.1016/S0031-0182(02)00249-3

Gray, A. (1846). Analogy between the flora of Japan and that of the United States. Am. J. Sci. Arts 2, 135–136.

Greiner, S., Lehwark, P., and Bock, R. (2019). OrganellarGenomeDRAW (OGDRAW) version 1.3. 1: expanded toolkit for the graphical visualization of organellar genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, W59–W64. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz238

Guindon, S., and Gascuel, O. (2003). A simple, fast and accurate method to estimate large phylogenies by maximum-likelihood. Syst. Bio. 52, 696–704. doi: 10.1080/10635150390235520

Guo, Y. Y., Luo, Y. B., Liu, Z. J., and Wang, X. Q. (2012). Evolution and biogeography of the slipper orchids: eocene vicariance of the conduplicate genera in the Old and New World tropics. PLoS ONE 7, e38788. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038788

Gustafsson, A. L. S., Verola, C. F., and Antonelli, A. (2010). Reassessing the temporal evolution of orchids with new fossils and a Bayesian relaxed clock, with implications for the diversification of the rare South American genus Hoffmannseggella (Orchidaceae: Epidendroideae). BMC Evol. Biol. 10, 177. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-10-177

Ha, Y.-H., Kim, C., Choi, K., and Kim, J.-H. (2018). Molecular phylogeny and dating of Forsythieae (Oleaceae) provide insight into the miocene history of Eurasian temperate shrubs. Front. Plant Sci. 9, 99. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00099

Hinsinger, D. D., Basak, J., Gaudeul, M., Cruaud, C., Bertolino, P., Frascaria-Lacoste, N., et al. (2013). The phylogeny and biogeographic history of ashes (Fraxinus, Oleaceae) highlight the roles of migration and vicariance in the diversification of temperate trees. PLoS ONE 8, e80431. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080431

Hu, C., Tian, H., Li, H., Hu, A., Xing, F., Bhattacharjee, A., et al. (2016). Phylogenetic analysis of a ‘jewel orchid’genus Goodyera (Orchidaceae) based on DNA sequence data from nuclear and plastid regions. PLoS ONE 11, e0150366. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150366

Iles, W. J., Smith, S. Y., Gandolfo, M. A., and Graham, S. W. (2015). Monocot fossils suitable for molecular dating analyses. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 178, 346–374. doi: 10.1111/boj.12233

Ito, Y., Tanaka, N., Albach, D. C., Barfod, A. S., Oxelman, B., and Muasya, A. M. (2017). Molecular phylogeny of the cosmopolitan aquatic plant genus Limosella (Scrophulariaceae) with a particular focus on the origin of the Australasian L. curdieana. J. Plant Res. 130, 107–116. doi: 10.1007/s10265-016-0872-6

Jung, J., Kim, C., and Kim, J.-H. (2021). Insights into phylogenetic relationships and genome evolution of subfamily Commelinoideae (Commelinaceae Mirb.) inferred from complete chloroplast genomes. BMC Genomics 22, 231. doi: 10.1186/s12864-021-07541-1

Juswara, L. S. (2010). Phylogenetic analyses of subtribe Goodyerinae and revision of Goodyera section Goodyera (Orchidaceae) from Indonesia, and fungal association of Goodyera section Goodyera (Dissertation). Columbus, OH: The Ohio State University.

Kearse, M., Moir, R., Wilson, A., Stones-Havas, S., Cheung, M., Sturrock, S., et al. (2012). Geneious Basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics 28, 1647–1649. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199

Kim, C., Cameron, K. M., and Kim, J. H. (2017). Molecular systematics and historical biogeography of Maianthemum ss. Am. J. Bot. 104, 939–952. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1600454

Kim, C., Kim, S.-C., and Kim, J.-H. (2019). Historical biogeography of Melanthiaceae: a case of out-of-North America through the Bering land bridge. Front. Plant Sci. 10, 396. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.00396

Kim, H. T., Kim, J. S., Moore, M. J., Neubig, K. M., Williams, N. H., Whitten, W. M., et al. (2015). Seven new complete plastome sequences reveal rampant independent loss of the ndh gene family across orchids and associated instability of the inverted repeat/small single-copy region boundaries. PLoS ONE 10, e0142215. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142215

Lang, K. Y. (1999). “Goodyera R. Br,” in Flora Reipublicae Popularis Sinicaem Tomus 17, eds K.Y. Lang, S.C. Chen, Y.B. Luo, and G.H. Zhu (Beijing: Science Press), 128–155.

Lawrence, K. T., Coxall, H. K., Sosdian, S., and Steinthorsdottir, M. (2021). Data From: Miocene Temperature Portal. Dataset version 1.0. Bolin Centre Database.

Lin, C.-S., Chen, J. J., Huang, Y.-T., Chan, M.-T., Daniell, H., Chang, W.-J., et al. (2015). The location and translocation of ndh genes of chloroplast origin in the Orchidaceae family. Sci. Rep. 5, 9040. doi: 10.1038/srep09040

Liu, D.-K., Tu, X.-D., Zhao, Z., Zeng, M.-Y., Zhang, S., Ma, L., et al. (2020). Plastid phylogenomic data yield new and robust insights into the phylogeny of Cleisostoma–Gastrochilus clades (Orchidaceae, Aeridinae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 145, 106729. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2019.106729

Liu, Y. W., Zhou, X. X., Schuiteman, A., Kumar, P., Hermans, J., Chung, S. W., et al. (2019). Taxonomic notes on Goodyera (Goodyerinae, Cranichideae, Orchidoideae, Orchidaceae) in China and an addition to orchid flora of Vietnam. Phytotaxa 395, 27–34. doi: 10.11646/phytotaxa.395.1.3

Moore, M. J., Bell, C. D., Soltis, P. S., and Soltis, D. E. (2007). Using plastid genome-scale data to resolve enigmatic relationships among basal angiosperms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104, 19363–19368. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708072104

Müller, S., Salomo, K., Salazar, J., Naumann, J., Jaramillo, M. A., Neinhuis, C., et al. (2015). Intercontinental long-distance dispersal of Canellaceae from the New to the Old World revealed by a nuclear single copy gene and chloroplast loci. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 84, 205–219. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2014.12.010

Pearce, N. R., and Cribb, P. J. (2002). The Orchids of Bhutan, Flora of Bhutan. Edinburgh: Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh.

POWO (2019). Plants of the World Online. Available online at: https://powo.science.kew.org/ (accessed July 20, 2021).

Rambaut, A. (2018). FigTree V 1.4.4.: Tree Drawing Tool in Computer Program and Documentation Distributed by the Author. Available online at http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/ (accessed May 8, 2020).

Ramírez, S. R., Gravendeel, B., Singer, R. B., Marshall, C. R., and Pierce, N. E. (2007). Dating the origin of the Orchidaceae from a fossil orchid with its pollinator. Nature 448, 1042–1045. doi: 10.1038/nature06039

Ronquist, F., Teslenko, M., Van Der Mark, P., Ayres, D. L., Darling, A., Höhna, S., et al. (2012). MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 61, 539–542. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/sys029

Rozas, J., Ferrer-Mata, A., Sánchez-DelBarrio, J. C., Guirao-Rico, S., Librado, P., Ramos-Onsins, S. E., et al. (2017). DnaSP 6: DNA sequence polymorphism analysis of large data sets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 34, 3299–3302. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msx248

Ruhlman, T. A., Chang, W.-J., Chen, J. J., Huang, Y.-T., Chan, M.-T., Zhang, J., et al. (2015). NDH expression marks major transitions in plant evolution and reveals coordinate intracellular gene loss. BMC Plant Biol. 15, 100. doi: 10.1186/s12870-015-0484-7

Schlechter, R. (1911). Die Orchidaceen von Deutsch-Neu-Guinea. Reperorium Specierum Novarum Regni Vegetabilis 9, 98–112. doi: 10.1002/fedr.19110090704

Seidenfaden, G., Wood, J. J., and Holttum, R. E. (1992). The Orchids of Peninsular Malaysia and Singapore. Fredensborg: Olsen & Olsen.

Shin, K.-S., Shin, Y. K., Kim, J.-H., and Tae, K.-H. (2002). Phylogeny of the genus Goodyera (Orchidaceae; Cranichideae) in Korea based on nuclear ribosomal DNA ITS region sequences. J. Plant Biol. 45, 182–187. doi: 10.1007/BF03030312

Smidt, E. C., Páez, M. Z., Vieira, L. d. N., Viruel, J., de Baura, V. A., Balsanelli, E., et al. (2020). Characterization of sequence variability hotspots in Cranichideae plastomes (Orchidaceae, Orchidoideae). PLoS ONE 15, e0227991. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0227991

Smidt, E. C., Salazar, G. A., Mauad, A. V. S. R., Engels, M. E., Viruel, J., Clements, M., et al. (2021). An Indomalesian origin in the Miocene for the diphyletic New World jewel orchids (Goodyerinae, Orchidoideae): molecular dating and biogeographic analyses document non-monophyly of the Neotropical genera. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 197, 322–349. doi: 10.1093/botlinnean/boab028

Stamatakis, A., Hoover, P., and Rougemont, J. (2008). A rapid bootstrap algorithm for the RAxML web servers. Syst. Biol. 57, 758–771. doi: 10.1080/10635150802429642

Strömberg, C. A. (2011). Evolution of grasses and grassland ecosystems. Annu. Rev. Earth Pl. Sc. 39, 517–544. doi: 10.1146/annurev-earth-040809-152402

Swofford, D. L. (2003). PAUP*: Phylogenetic Analysis using Parsimony and Other Methods. Version 4. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates.

Thiv, M., Gouveia, M., and Menezes de Sequeira, M. (2021). The Madeiran laurel forest endemic Goodyera macrophylla (Orchidaceae) is related to American orchids. An. Jardin. Bot. Madrid. 78, e116. doi: 10.3989/ajbm.2605

Tiffney, B. H. (1985a). The Eocene North Atlantic land bridge: its importance in Tertiary and modern phytogeography of the Northern Hemisphere. J. Arnold Arboretum 66, 243–273. doi: 10.5962/bhl.part.13183

Tiffney, B. H. (1985b). Perspectives on the origin of the floristic similarity between eastern Asia and eastern North America. J. Arnold Arboretum 66, 73–94. doi: 10.5962/bhl.part.13179

Tiffney, B. H., and Manchester, S. R. (2001). The use of geological and paleontological evidence in evaluating plant phylogeographic hypotheses in the Northern Hemisphere Tertiary. Int. J. Plant Sci. 162, S3–S17. doi: 10.1086/323880

Trifinopoulos, J., Nguyen, L.-T., von Haeseler, A., and Minh, B. Q. (2016). W-IQ-TREE: a fast online phylogenetic tool for maximum likelihood analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W232–W235. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw256

Tu, X.-D., Liu, D.-K., Xu, S.-W., Zhou, C.-Y., Gao, X.-Y., Zeng, M.-Y., et al. (2021). Plastid phylogenomics improves resolution of phylogenetic relationship in the Cheirostylis and Goodyera clades of Goodyerinae (Orchidoideae, Orchidaceae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 164, 107269. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2021.107269

Wen, J., Ickert-Bond, S., Nie, Z.-L., and Li, R. (2010). “Timing and modes of evolution of eastern Asian-North American biogeographic disjunctions in seed plants,” in Darwin's Heritage Today-Proceeding of the Darwin 200 Beijing International Conference, eds M. Long, H. Gu, and Z. Zhou (Beijing: Higher Education Press), 252–269.

Wen, J., Nie, Z.-L., and Ickert-Bond, S. (2016). Intercontinental disjunctions between eastern Asia and western North America in vascular plants highlight the biogeographic importance of the Bering land bridge from late Cretaceous to Neogene. J. Syst. Evol. 54, 469–490. doi: 10.1111/jse.12222

Wicke, S., Schneeweiss, G. M., dePamphilis, C. W., Müller, K. F., and Quandt, D. (2011). The evolution of the plastid chromosome in land plants: gene content, gene order, gene function. Plant Mol. Biol. 76, 273–297. doi: 10.1007/s11103-011-9762-4

You, Y., Huber, M., Müller, R., Poulsen, C., and Ribbe, J. (2009). Simulation of the middle Miocene climate optimum. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L04702. doi: 10.1029/2008GL036571

Keywords: next-generation sequencing, plastid genome, phylogenomic, age estimation, Bering Land Bridge

Citation: Kim T-H and Kim J-H (2022) Molecular Phylogeny and Historical Biogeography of Goodyera R. Br. (Orchidaceae): A Case of the Vicariance Between East Asia and North America. Front. Plant Sci. 13:850170. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.850170

Received: 07 January 2022; Accepted: 04 April 2022;

Published: 02 May 2022.

Edited by:

Charles Bell, University of New Orleans, United StatesReviewed by:

Qiang Fan, Sun Yat-sen University, ChinaDiego Bogarin, University of Costa Rica, Costa Rica

Copyright © 2022 Kim and Kim. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Joo-Hwan Kim, a2ltamgyMDA5QGdhY2hvbi5hYy5rcg==

Tae-Hee Kim

Tae-Hee Kim Joo-Hwan Kim

Joo-Hwan Kim