95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Plant Sci. , 25 April 2022

Sec. Plant Breeding

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.849421

This article is part of the Research Topic Generating Useful Genetic Variation in Crops by Induced Mutation, Volume II View all 6 articles

Jun Liu1†

Jun Liu1† Chuanbo Sun1†

Chuanbo Sun1† Siqi Guo2†

Siqi Guo2† Xiaohong Yin1

Xiaohong Yin1 Yuling Yuan3

Yuling Yuan3 Bing Fan3

Bing Fan3 Qingxue Lv1

Qingxue Lv1 Xinru Cai1

Xinru Cai1 Yi Zhong1

Yi Zhong1 Yuanfeng Xia1

Yuanfeng Xia1 Xiaomei Dong2

Xiaomei Dong2 Zhifu Guo2

Zhifu Guo2 Guangshu Song1*

Guangshu Song1* Wei Huang1*

Wei Huang1*

The mechanical strength of the stalk affects the lodging resistance and digestibility of the stalk in maize. The molecular mechanisms regulating the brittleness of stalks in maize remain undefined. In this study, we constructed the maize brittle stalk mutant (bk5) by crossing the W22:Mu line with the Zheng 58 line. The brittle phenotype of the mutant bk5 existed in all of the plant organs after the five-leaf stage. Compared to wild-type (WT) plants, the sclerenchyma cells of bk5 stalks had a looser cell arrangement and thinner cell wall. Determination of cell wall composition showed that obvious differences in cellulose content, lignin content, starch content, and total soluble sugar were found between bk5 and WT stalks. Furthermore, we identified 226 differentially expressed genes (DEGs), with 164 genes significantly upregulated and 62 genes significantly downregulated in RNA-seq analysis. Some pathways related to cellulose and lignin synthesis, such as endocytosis and glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored biosynthesis, were identified by the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Gene and Genomes (KEGG) and gene ontology (GO) analysis. In bulked-segregant sequence analysis (BSA-seq), we detected 2,931,692 high-quality Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) and identified five overlapped regions (11.2 Mb) containing 17 candidate genes with missense mutations or premature termination codons using the SNP-index methods. Some genes were involved in the cellulose synthesis-related genes such as ENTH/ANTH/VHS superfamily protein gene (endocytosis-related gene) and the lignin synthesis-related genes such as the cytochrome p450 gene. Some of these candidate genes identified from BSA-seq also existed with differential expression in RNA-seq analysis. These findings increase our understanding of the molecular mechanisms regulating the brittle stalk phenotype in maize.

As the most produced grain crop, maize (Zea mays L.) is an economically important food and forage crop globally. The stalk strength of maize directly influences the lodging resistance and silage quality. Previous studies of maize rinds have indicated that the rind of the stalk is the chief determinant of stalk strength. The structure and composition of the hypodermal cell wall and vascular bundles in the rind directly influence the stalk strength of maize. Furthermore, the stalk strength is strongly associated with the contents and concentration of cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin, and pectin in the cell wall, which directly affect the lodging resistance and digestibility of the stalk (Jiao et al., 2019; Vanholme et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2020). To the best of our knowledge, a large number of genes are involved in biosynthesis and modifications of the cell wall (Carpita et al., 2001). Brittle stalk phenotype is also associated with many genes, and only a few studies have explored the functions of the brittle stalk genes. The characterization of mutants is an effective method to identify the functions of brittle stalk genes and individual components of cell walls. Functions of some brittle stalk genes have been characterized using the mutations in the orthologous genes of Arabidopsis, rice, maize, wheat, and barley (Kokubo et al., 1989; Li et al., 2003; Ching et al., 2006; Burton et al., 2010; Deng et al., 2019; Jiao et al., 2019).

Cellulose synthase (CESA) genes are strongly related to cell wall synthesis, affecting the mechanical strength of cell walls in plants. Many CESA genes related to brittle stalks, such as AtCESA1, AtCESA3, AtCESA4, AtCESA7, and AtCESA8, have been identified in Arabidopsis (Taylor et al., 2003; Zhong et al., 2003; Persson et al., 2007). Rice mutants corresponding to fragile fiber and collapsed xylem mutants in Arabidopsis are brittle culm (bc) mutants, displaying a bc phenotype (Li et al., 2003; Tanaka et al., 2003). Some CESA genes, such as OsCESA4, OsCESA7, and OsCESA9, have also been studied using the bc mutants. The loss-of-function mutations of these genes lead to the reduction of cellulose content and the brittle phenotype (Zhang et al., 2019). COBRA genes encode glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored proteins (COBRA-like proteins), which influence cellulose biosynthesis in primary and secondary cell walls in plants. The COBRA-like family comprises 12 members in Arabidopsis and 11 in rice (Roudier et al., 2002; Li et al., 2003). AtCOBL4 from Arabidopsis and its orthologs, OsBC1 from rice, TmBr1 from wheat, and SbBC1 from sorghum are associated with the mechanical strength of stalks. The loss-of-function mutations of these genes also result in the brittle stalk phenotype (Li et al., 2003, 2019; Brown et al., 2005; Persson et al., 2005; Sindhu et al., 2007; Sato et al., 2010; Deng et al., 2019).

As a chitinase-like protein, CTL1 influences cellulose biosynthesis in plants. In Arabidopsis, AtCTL1 plays an important role in establishing interaction between cellulose microfibrils and hemicelluloses, which affects cellulose biosynthesis (Sánchez-Rodríguez et al., 2012). In rice, OsCTL1 was isolated from the rice bc15 mutant and found to result in a reduction in mechanical strength and cellulose content (Wu et al., 2012). In addition, some genes that modulate the dynamics and structures of the cytoskeleton influence stalk the brittleness and cell wall biosynthesis. OsBC12, an ortholog of the kinesin gene AtKIF4/FRA1 in Arabidopsis, is involved in the microtubule-based effects on cellulose microfibril order. The loss-of-function mutations of OsBC12 lead to the brittleness phenotype of plants (Zhang et al., 2010). OsBC3, a dynamin-related protein in rice, also affects cellulose biosynthesis and mechanical strength (Xiong et al., 2010).

In maize, some brittle stalk (bk) mutants are associated with cellulose biosynthesis and have been utilized to isolate the genes related to brittleness (Langham, 1940; Multani et al., 2003; Ching et al., 2006; Sindhu et al., 2007; Jiao et al., 2019). ZmBk2 gene identified from bk2 mutant encodes a COBRA-like protein similar to rice OsBC1 and Arabidopsis AtCOBL4. ZmBk2 is involved in secondary cellulose biosynthesis of the cell wall, controlling mechanical strength and brittleness of stalks (Sindhu et al., 2007). ZmCtl1 gene identified from bk4 mutant encodes a Chitinase-like1 protein, which is expressed at its highest levels in elongated internodes. ZmCtl1 interacts with CESA proteins, enhancing the tensile strength of stalks (Jiao et al., 2019).

The stalk development of plants is a highly complex process that cannot be completely elucidated by traditional molecular approaches. Although several genes related to brittle stalks have been characterized, the molecular mechanisms regulating the brittleness of stalks in maize remain undefined. It is certain that the brittleness phenotype of maize is involved in multiple genes such as rice and Arabidopsis. It is absolutely essential to clone more genes related to the mechanical strength and brittleness of stalks using bk mutants. As effective methods to identify multiple genes, transcriptome analysis (RNA-seq) and bulked-segregant sequence analysis (BSA-seq) have been widely used to characterize stalk development in various plants. BSA-seq coupled to RNA-seq has also been successfully applied to gene mapping and identification in maize (Liu et al., 2012; Li et al., 2013; Nestler et al., 2014; Tang et al., 2014). In this study, we constructed and identified the maize mutant materials with brittle stalk phenotypes. Cell wall components of the stalk, including cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin, starch, and total soluble sugars, were investigated. Furthermore, some pathways and genes related to brittleness phenotype were identified by RNA-seq combined with BSA-seq. This study provides insight into the molecular basis of the brittle stalk phenotype in maize.

The maize mutants of the brittle stalk were obtained from the M2 families created by crossing the W22:Mu line (active MuDR donor parent) with the Zheng 58 line (recipient parent). Zheng 58 is the female parent of hybrid Zhengdan958 with high and stable yield, multiresistant, and high plant area in China. To have a uniform background, the material was propagated by backcrossing bk mutant with female parent Zheng 58 for additional five times (BC5F1). The BC5F1 was advanced to BC5F2 by selfing for obtaining the mutant (bk5) and wild-type (WT; non-brittleness) plants. The mutant bk5 and WT plants were indistinguishable from each other except for the appearance of a brittleness phenotype at 4 weeks in the mutant.

The second internodes of stalks and leaf sections of bk5 and WT plants in BC5F2 individuals (approximately 1 mm in height) were cut with a razor blade and fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.2 M phosphate buffer (pH = 7.4) overnight at 4°C. After being washed with 0.2 M phosphate buffer, the samples were dried at a critical point under a low vacuum in the desiccators (IXRF, VFD-30, United States) and sputter-coated with gold. All tissues were observed under a Hitachi Regulus 8100 scanning electron microscope (SEM) (Japan) at an acceleration voltage of 10 kV.

The samples were collected from the middle of the second internodes of stalks of bk5 and non-brittleness plants from BC5F2 individuals in the five-leaf stage and then dried at 105°C for half an hour and 80°C in an oven for 48 h. The samples of total dry mass were ground and screened through a combined 40–80 mesh sieve. The carbohydrates and lignin were extracted using a two-step sulfuric acid hydrolysis process (Hatfield et al., 1994). The sample quantity was measured using a high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system (Agilent 1,100 series). Cellulose content was calculated from the glucose content. Hemicellulose content was determined from the sum of xylose and arabinose contents according to the NREL Laboratory analytical procedure. Lignin content was calculated as the sum of the acid-soluble and acid-insoluble lignin contents (Li et al., 2017). The total soluble sugars were extracted with distilled water and their contents were determined by the anthrone/H2SO4 method using a UV-vis spectrometer (UV-1800, Shimadzu). Crude starch was purified from stalks by homogenization in 0.7 M perchloric acid and 10 mg of sand. The crude starch pellets with dimethyl sulfoxide were incubated in a boiling water bath for 15 min to disperse the starch. Later, the starch was enzymatically digested, and the content of Glc was determined using a kit from Megazyme (Total Starch Assay Kit, K-TSTA).

Total RNA was extracted from the stalks of bk5 and WT plants in BC5F2 individuals after the five-leaf stage using an RNA extraction kit (Aidlab, China) and then treated with RNase-free DNase I (Aidlab, China) to remove genomic DNA. RNA libraries were constructed and sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform to generate 150 bp paired-end reads (Biomarker, China). Raw reads of cDNA fragments were preprocessed to remove adapter and low-quality reads. Eligible reads were aligned to the maize B73 reference genome (AGPv2).1

The read numbers mapped to each gene were summarized using HTSeq version 0.6.1 (Anders and Huber, 2010; Hill et al., 2013), and the Fragments PerKilobase Million (FPKM) of each gene was calculated to quantify the gene expression based on read counts mapping to the gene, the length of the gene, and the sequencing depth. The DESeq package in R (version 1.18.0) was used to perform differential expression analysis of the two groups (three biological replicates per group). The P-values were adjusted using Benjamini and Hochberg’s method to control for false discovery rates. Genes with an adjusted p < 0.05 were set as the criteria to filter the differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of DEGs was performed with the GOseq R package (Young et al., 2010). GO terms with a corrected P-value of < 0.05 were considered to be significantly enriched in DEGs. The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway annotations were assigned according to the KEGG database.2 The KOBAS software (Mao et al., 2005) was used to test the enrichment of DEGs in KEGG pathways.

A total of 60 maize plants (B694, 30 brittleness plants, B695, 30 non-brittleness plants) from the above-mentioned BC5F2 population were used for BSA-seq analysis. Total DNA was extracted from leaves with a DNA extraction kit (Aidlab, China), and two DNA pools were constructed by mixing equal amounts of DNA from 30 brittleness and 30 non-brittleness plants. The libraries of these two DNA pools were constructed using an Illumina sequencing platform (HiSeq2500; Illumina). For genomic re-sequencing, the paired-end 100-base (PE100) reads were generated and aligned to the maize B73 reference genome sequences (AGPv2; see text footnote 1) using BWA (Li and Durbin, 2009). The GATK software (McKenna et al., 2010) was used to detect SNPs and small indels and correct for alignment errors. The variants were removed if more than two SNPs occurred in a 5-bp window if the distance was less than 10 bp between two indels or SNPs were within 5 bp of an indel. The association analysis was conducted by the InDel index (Fekih et al., 2013).

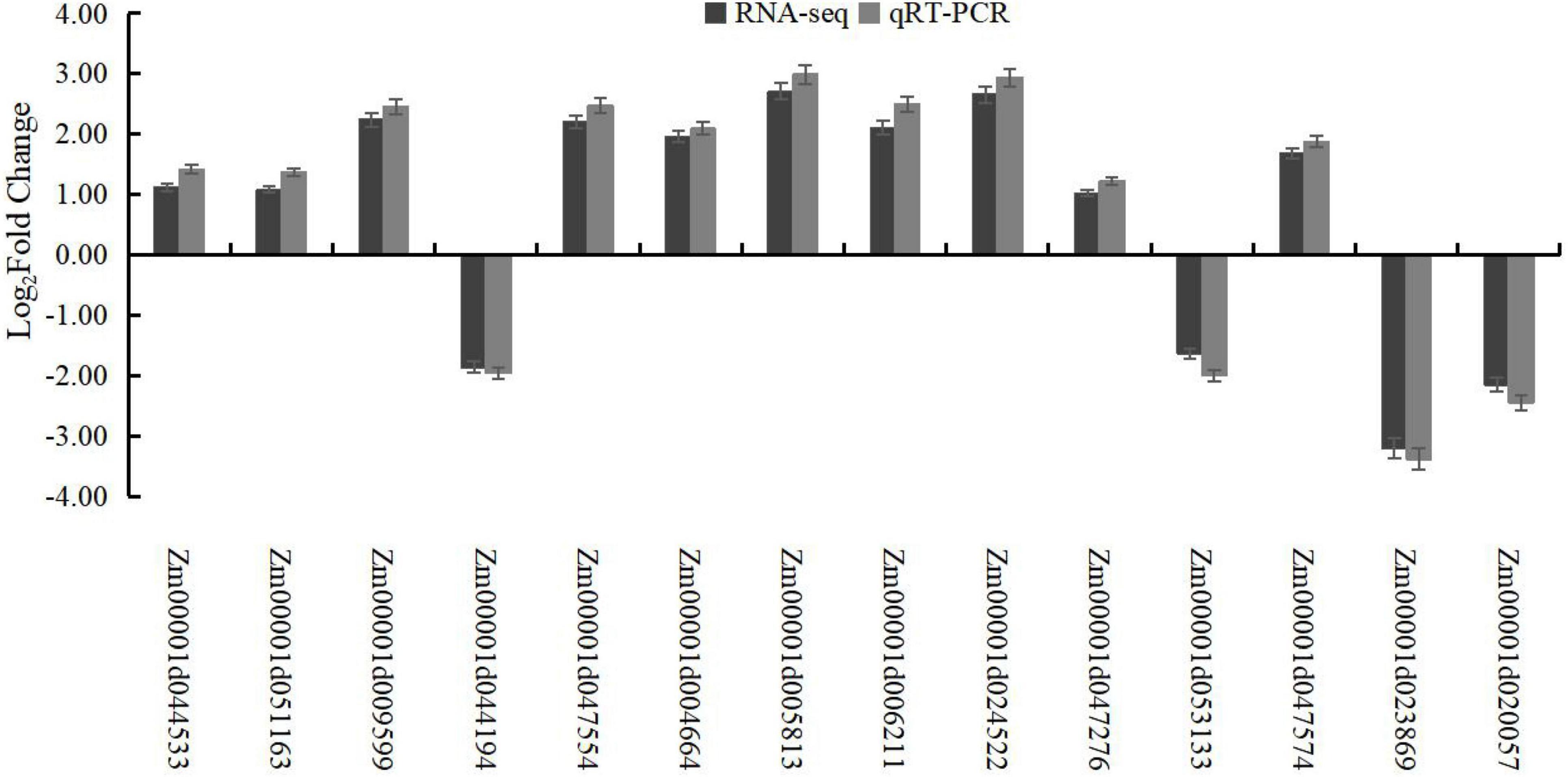

The real-time quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed to identify the expression patterns shown by the RNA-seq analysis. Fourteen genes were randomly selected on the basis of their potential functions in RNA-seq. The qRT-PCR was carried out with a Monad Selected q225 Real-Time PCR System (Monad, China) under the following conditions: 95°C for 3 min; 35 cycles of 95°C for 5 s, 58°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 2 min; and 1 cycle of 72°C for 10 min. Each sample was analyzed in the three biological and three technical replicates. The relative expression levels were calculated via the ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). The actin gene of maize (GenBank accession no. AY273142) was used as a reference gene. All primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

All data that needed statistical analysis are shown as mean values ± SE of the mean by using 3 replicates. The SPSS Statistics3 software was used for statistical analysis via Student’s t-test. Significant differences were considered significant with a probability level of p < 0.05.

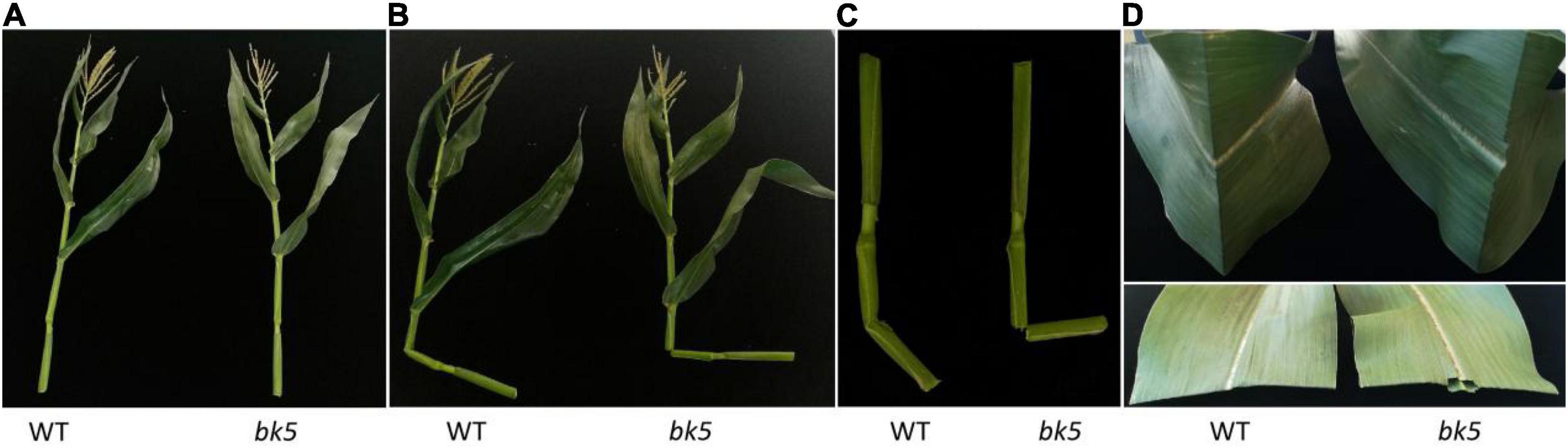

In the uniform backcross progeny, the mutants were phenotypically indistinguishable from WT siblings, except that the stalk and leaves of mutants were brittle after the five-leaf stage throughout the life of the plant (Figure 1). To confirm whether known genes result in the mutant phenotype, we identified the sequences of brittle stalk genes ZmBk2 and ZMBk4 in the mutants and WT using PCR sequencing. No sequence difference was found in these two genes and their promoters between the mutant and WT (Supplementary Figure 1), indicating that some other genes or factors except for ZmBk2 and ZMBk4 could lead to the brittleness phenotype in the mutants. Thus, this mutant was named bk5 for further investigation.

Figure 1. Phenotypes of stalks and leaves of wild-type (WT) and mutant plants at the stage of anthesis. (A) Normal growth conditions. (B) Broken stalks. (C) Enlargement of broken stalks. (D) Broken leaves.

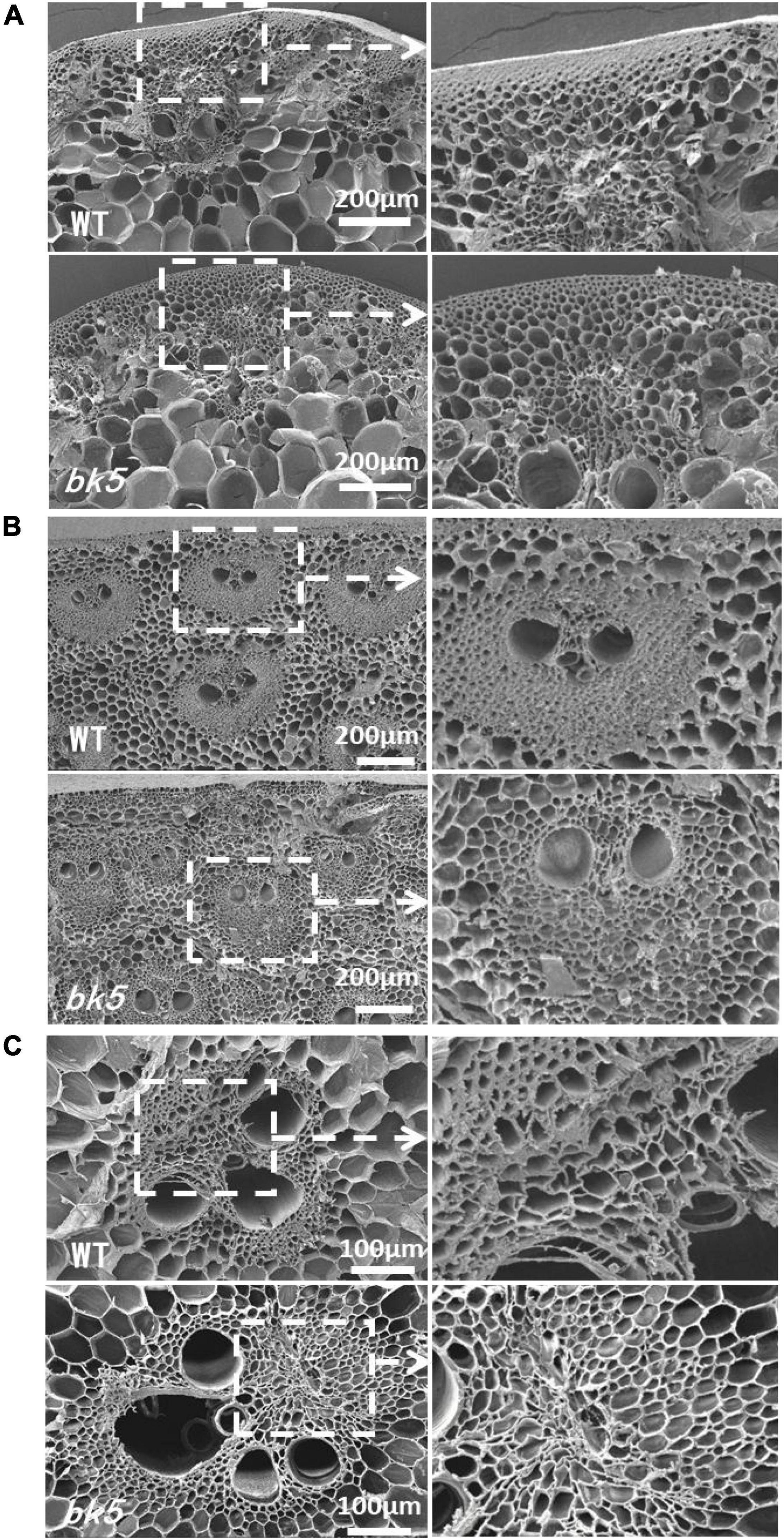

To determine whether the brittleness phenotype of bk5 arises from changes in cell structure, we compared the sclerenchyma cells of internode stalks and leaf veins of bk5 with WT siblings using SEM. Compared to WT plants, the sclerenchyma cells in leaf veins (Figure 2A) and stalks (Figures 2B,C) of bk5 had a looser arrangement. The sclerenchyma cell wall was thinner in the rind region and the stalk vascular bundles in bk5 than those of WT plants (Figure 2). These results demonstrated that the thickness of cell walls and the tightness of cell–cell junctions directly affected the stalk brittleness.

Figure 2. Scanning electron micrographs of bk5 and WT stems and veins taken from cross sections. (A) Leaf veins and local enlargement. (B) Rind regions of the stalk and local enlargement of the vascular bundle. (C) Central regions of the stalk and local enlargement of vascular bundle.

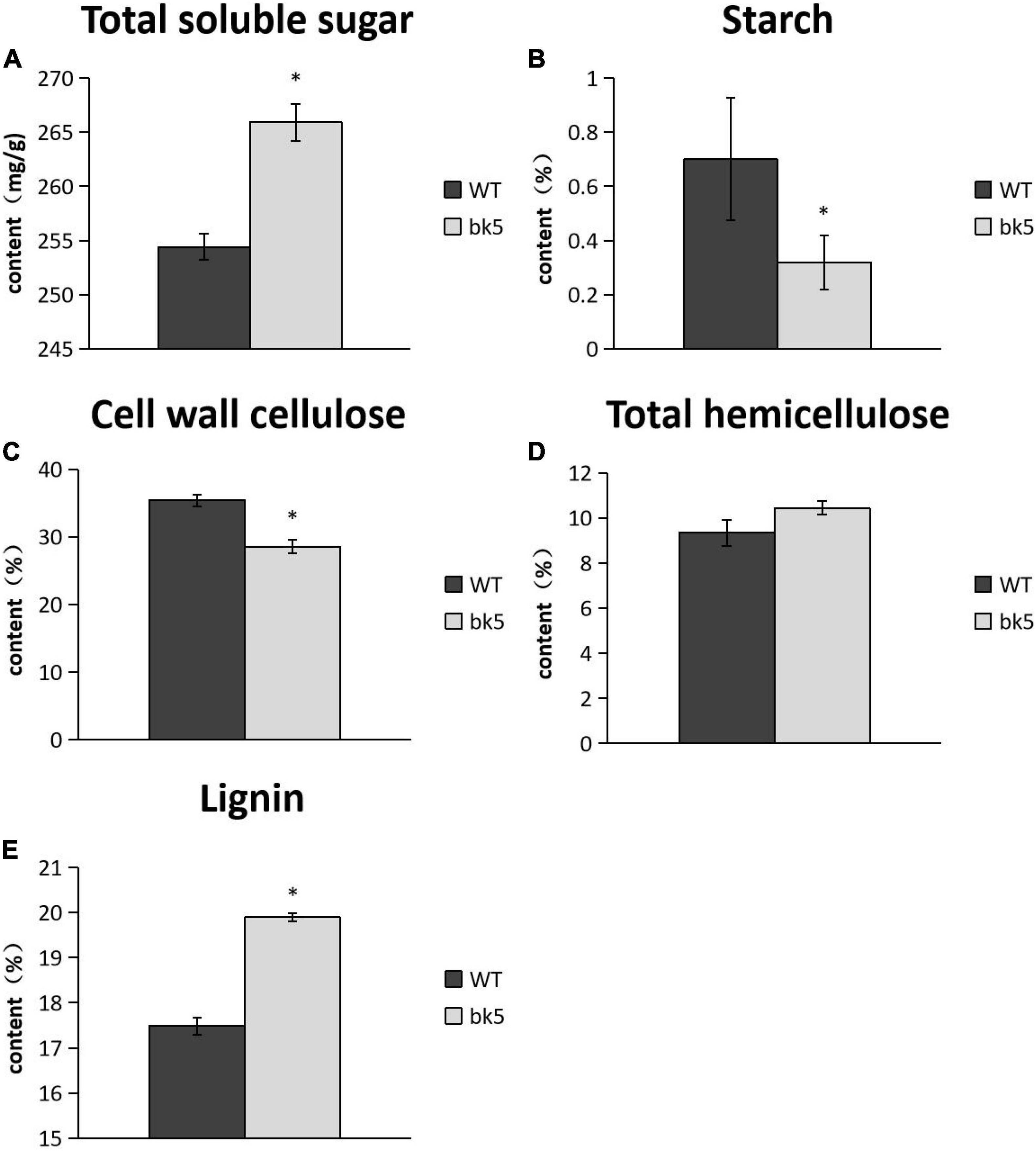

To further explore the association between brittleness and cellular components, we analyzed the cell wall composition of stalks in bk5 and WT plants. The results showed that the cellulose content in cell walls and the starch content in bk5 stalks were significantly lower than those of WT plants (Figures 3B,C), while total soluble sugar content and lignin content were significantly higher than those of WT plants (Figures 3A,E). No obvious difference in hemicellulose content was found between bk5 and WT plants (Figure 3D). These results indicated that the cellulose and starch contents in the cell walls of maize stalks are directly related to the stalk brittleness.

Figure 3. Determination of cell wall composition. (A) Content of total soluble sugar. (B) Starch Content. (C) Cell wall cellulose. (D) Total hemicellulose content. (E) Lignin content. Biological triplicates were averaged and statistically analyzed via Student’s t-test (*p < 0.05).

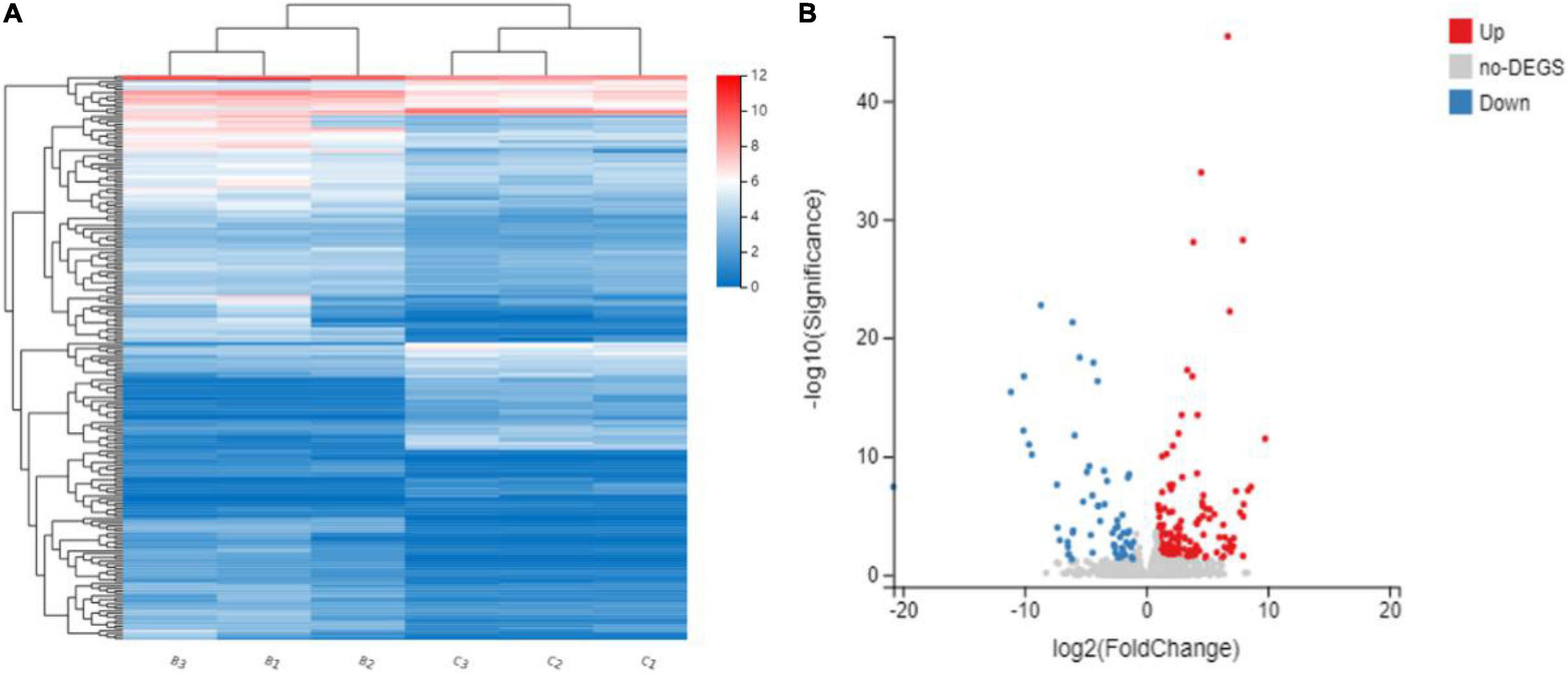

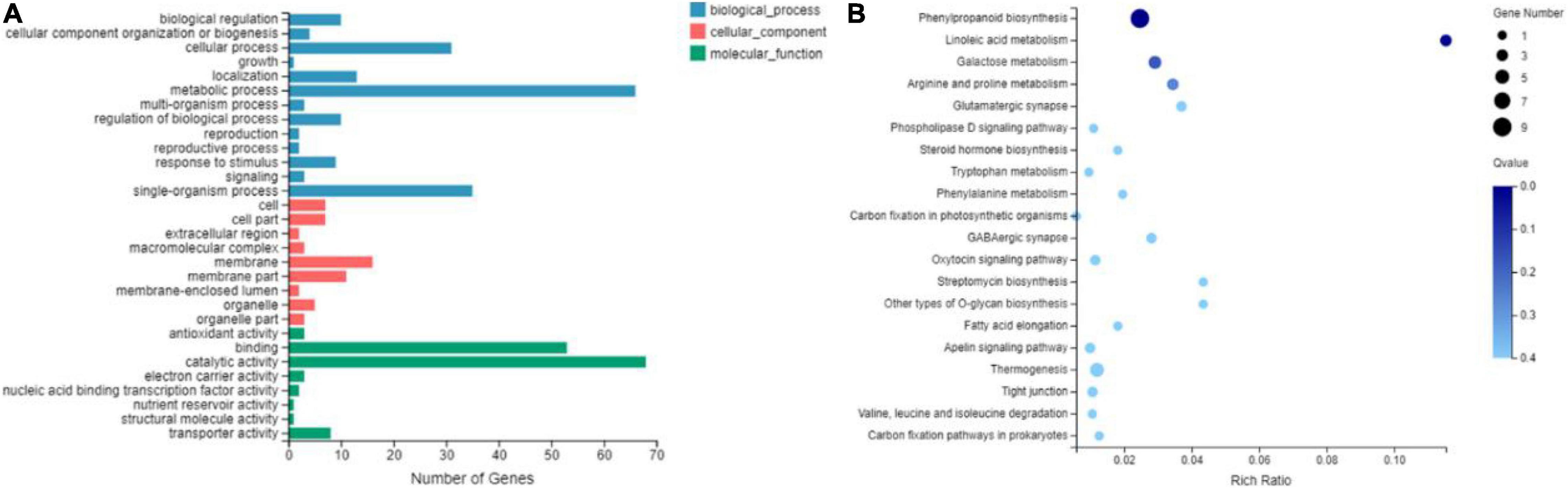

To investigate the transcriptomic difference between bk5 and WT, RNA-seq analysis was performed. In total, 49.34–65.74 million clean reads were generated for each sample. After the removal of low-quality reads, duplicated sequences, adaptor sequences, and ambiguous reads, 78.18–87.14% of reads were uniquely mapped to the Maize B73 reference genome (Table 1). DEGs were compared between the bk5 and WT stalks, and the expression patterns of DEGs were also confirmed by hierarchical clustering to identify the groups of different biological replicates with similar expression patterns (Figure 4A). Comparison results showed that 226 DEGs were detected, with 164 genes significantly upregulated and 62 genes significantly downregulated (Figure 4B and Supplementary Table 2). In these DEGs, ZmBk2 was also detected (Figure 5, Zm00001d047276), indicating that the expression of ZmBk2 may be affected by some factors.

Figure 4. Hierarchical cluster analysis (A) and volcano plots (B) of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between mutant bk5 and WT. Averaged log2 relative NRPKM of all the genes in each cluster was used to generate the heat map.

Figure 5. Validation of RNA-seq expression by qRT-PCR. The actin gene (GenBank accession no. AY273142) was used as an internal control.

The GO enrichment analysis was performed to classify the functions of all DEGs. A significantly enriched GO term was identified with the corrected P < 0.05. The top 30 significant subcategories were finally enriched for GO functional categories, and 13, 9, and 8 functional GO terms were identified for biological processes, cellular components, and molecular functions, respectively (Figure 6A). For example, “metabolic process” (GO:0008152, 66 genes) in the biological processes, “catalytic activity” (GO:0003824, 68 genes) and “binding” (GO:0005488, 53 genes) in the molecular function category was the most highly enriched GO terms. Furthermore, the KEGG enrichment analysis of DEGs was performed to identify the biological pathways. The top 20 KEGG pathways with the most representation were shown in Figure 6B. Many pathways were involved in the cellulose synthesis-related pathways, such as endocytosis (Ko04144), GPI-anchored biosynthesis (Ko00563), tryptophan metabolism (Ko00380), glycerolipid metabolism (Ko00561), and calcium signaling pathway (Ko04020), as well as lignin synthesis-related pathways, such as steroid hormone biosynthesis (Ko00140) and phenylalanine metabolism (Ko00360). In addition, the starch and sucrose metabolism (Ko00500) pathways were also enriched. The expression levels of the genes related to these pathways in RNA-seq have been listed in Supplementary Table 3. These pathways are probably associated with the brittleness phenotype in maize.

Figure 6. Gene ontology classification (A) and enriched Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genome pathway scatterplots (B) of DEGs shared by mutant bk5 vs. WT.

To confirm the accuracy of transcriptome sequencing, 14 genes, including 5 genes related to cellulose synthesis, lignin synthesis, and starch and sucrose metabolism-related pathways, were selected, and their expression profiles were analyzed using qRT-PCR. The results showed the same expression profiles between qRT-PCR assays and RNA-seq analysis, which showed the high reliability of transcriptome sequencing (Figure 5).

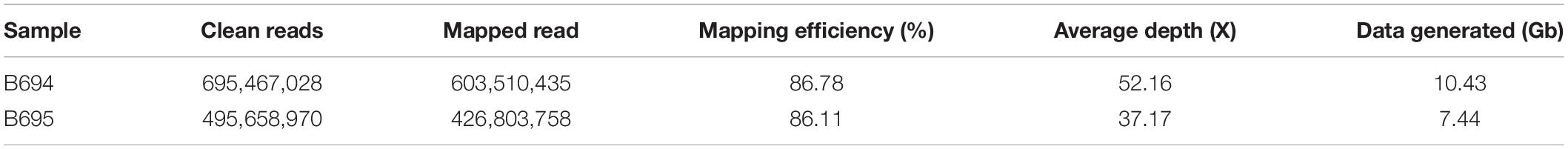

Whole-genome re-sequencing data were generated for brittleness bulk (B694) and non-brittleness bulk (B695) using the Illumina HiSeq2500. In total, 69.55 million clean reads were generated for the brittleness bulk and 49.57 million clean reads for the non-brittleness bulk. Mapping of those reads to the reference genome B73 led to 52.16X and 37.17X coverage with 86.78 and 86.11% mapping efficiency for brittleness and non-brittleness bulks, respectively. The obtained sequencing data were 10.43 GB for B694 and 7.44 GB for B695 (Table 2). Then, 2,931,692 high-quality SNPs were detected after filtering SNPs with low coverage and discrepancy (Figure 7).

Table 2. Summary of sequencing and mapping from brittleness bulk (B694) and non-brittleness bulk (B695) for BSA-seq analysis.

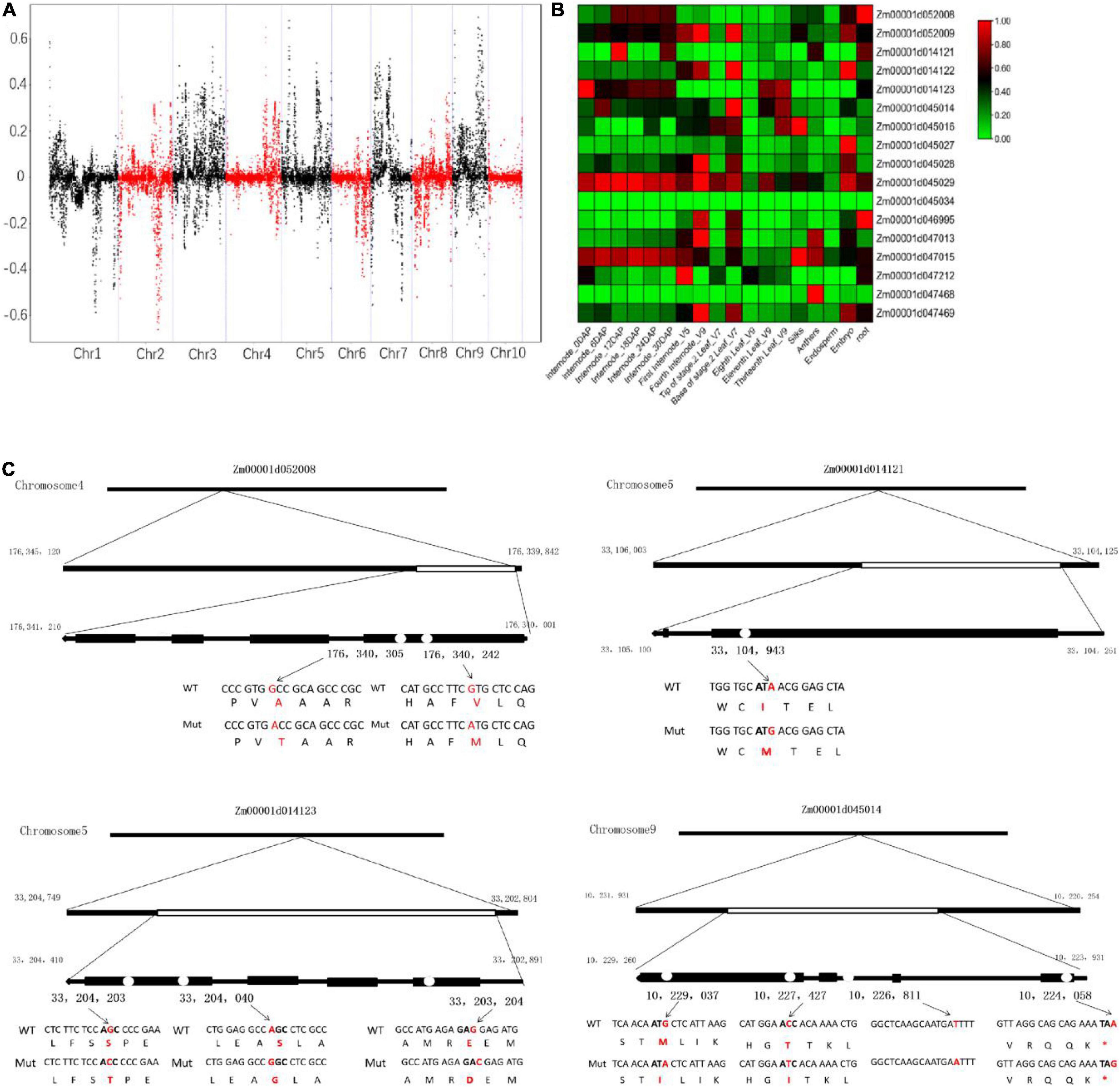

To examine the genomic region related to brittleness phenotype, the SNP-index methods were used to detect the allele segregation of SNPs between the two bulks. The SDs for the genome-wide median were chosen based on the threshold value of the confidence interval of 0.6. Finally, we identified five overlapped regions containing 17 candidate genes with missense mutations or premature termination codons. These genes were located on chromosome 4 (0.3 Mb region containing 2 genes), chromosome 5 (0.2 Mb region containing 3 genes), and chromosome 9 (10.7 Mb containing 12 genes), respectively (Figure 8A and Table 3). Some of these genes were involved in the cellulose synthesis such as ENTH/ANTH/VHS superfamily protein gene (Zm00001d052008, endocytosis-related gene) and chloroplast RNA splicing-related gene (Zm00001d045014), as well as the lignin synthesis such as cytochrome p450 (Zm00001d014121) and peroxidase superfamily protein gene (Zm00001d014123). The expression levels of some candidate genes were different in various tissues and at different growth stages of the same tissue, especially the internode of the stalk (Figure 8B). In addition, some candidate genes identified from BSA-seq also existed with differential expression in RNA-seq analysis. Furthermore, the sequence variations of the above-mentioned candidate genes were analyzed. These sequence variations from SNP sites mainly resulted due to some changes in amino acid residues (Figure 8C). This needs further study on whether the Mu transposons cause these sequence variations.

Figure 8. Allele frequency difference graph from bulked-segregant sequence analysis (A), heat map of expression profiles of candidate genes in maize (B), and the sequence variations of the candidate genes related to the cellulose and lignin synthesis (C). The standard deviations for the genome-wide median were chosen based on the threshold value of the confidence interval of 0.6.

As a complex trait, the stalk development in plants relates closely to many biological processes, including cell wall synthesis, cell wall modification, and vascular bundle formation. These factors directly affect the mechanical strength of the stalk. It was confirmed that the brittle stalk phenotype is associated with many genes (Roudier et al., 2002; Li et al., 2003). In many plants, some genes related to the brittleness phenotype have been identified, while more than one brittle stalk gene was cloned in maize (Sindhu et al., 2007; Jiao et al., 2019). Thus, identifying more brittle stalk genes is important for understanding the molecular mechanism of the stalk’s mechanical strength and brittleness in plants. Because of the fragile stalk strength, the brittle stalk trait in crops is clearly unfavorable for lodging resistance. However, reducing the content of cellulose and lignin can increase the digestibility of the stalk, which increases the feed value of crops, especially maize silage (Wang et al., 2020; Vinayan et al., 2021). From this perspective, the brittle stalk trait in crops is favorable for the feed industry. For breeding applications aiming at unfavorable or favorable traits, molecular markers based on brittle stalk genes can be developed to assist maize breeding.

Published studies have shown that the brittle stalk phenotype in plants is strongly associated with cellulose synthesis and lignin synthesis (Jiao et al., 2019). As the most abundant polysaccharide in plant cell walls, cellulose is synthesized at the plasma membrane by CESA complexes (CSC) using uridine diphosphate (UDP)-glucose as substrates (Somerville, 2006). In this process, the transport of CSCs from the Golgi to the plasma membrane, UDP-glucose, and endocytosis is very vital for cellulose biosynthesis. The trans-Golgi network/early endosome (TGN/EE) compartment has been implicated in protein sorting and as a hub of plant exocytosis and endocytotic pathways. The Golgi-localized STELLO1 and 2 (STL1/2) proteins regulate cellulose synthesis likely by controlling the assembly of CESA CSCs in the Golgi (Zhang et al., 2016; Polko and Kieber, 2019). In this study, an endocytosis-related gene (Zm00001d052008), ENTH/ANTH/VHS superfamily protein gene was identified in BSA-seq analysis. Coincidentally, the endocytosis pathway (Ko04144) was also enriched in the KEGG analysis of RNA-seq. It was shown that the endocytosis may be associated with the brittle stalk phenotype. In addition, a molecular function category, UDP-galactosyltransferase activity (GO:0035250), was detected in GO enrichment analysis.

Besides the CSC, cellulose synthesis is also highly related to other factors such as transcription factors, COBRA-like protein, tryptophan metabolism, etc. (Bray et al., 1996; Dai et al., 2011; Noda et al., 2015). The transcription factor OsMYB103 is a transcriptional regulator of cellulose synthesis by targeting CESA genes in rice (Yang et al., 2014). Some NAC transcription factors are transcriptional switches for the difference of xylem vessels, which regulate the cellulose synthesis and the formation of secondary cell walls in the tissues (Kubo et al., 2005). In this study, the expression levels of MYB-related-transcription factor genes (Zm00001d044194 and Zm00001d009599) and NAC-transcription factor 81 gene (Zm00001d047554) differed between bk5 and WT based on the RNA-seq analysis. These transcription factors may regulate the expression of some genes related to cellulose synthesis in maize, which affects the brittle stalk phenotype. As previously mentioned, ZmBk2 encodes a COBRA-like protein (GPI-anchored protein), which results in the brittleness phenotype in maize mutant bk2 (Sindhu et al., 2007). In this study, we did not find the sequence difference of ZmBk2 and its promoter between bk5 and WT by BSA-seq and PCR sequencing. However, the expression difference of ZmBk2 between bk5 and WT was found by the RNA-seq analysis. In the KEGG analysis, the GPI-anchored biosynthesis pathway (Ko00563) was also enriched. These results indicated that the expression of ZmBk2 may be affected by more genes or some unknown factor(s). Tryptophan oxidation can reduce the extent of binding of the cellulose-binding domain of an exoglucanase/xylanase (CBDcex) to cellulose, which affects the mechanical strength of the stalk in plants (Bray et al., 1996). In this study, the tryptophan metabolism pathway (Ko00380) was enriched in the KEGG analysis. Taken together, these genes or pathways may regulate the cellulose synthesis, which in turn lead to the brittle stalk phenotype in maize. Naturally, more work is required to elaborate on these speculations.

Besides cellulose synthesis, lignin is also associated with the mechanical strength of the stalk in maize. In rice bc mutant bc1, sorghum bc mutant sbbc1, and maize brittle stalk mutant bk2, the lignin contents were higher than those of WT. Furthermore, it was speculated that patterning of lignin–cellulose interactions resulted in the brittle stalk phenotype of mutant bk2 (Li et al., 2003, 2019; Ching et al., 2006; Sindhu et al., 2007). In addition, the lignin synthesis relates to some secondary metabolites and aromatic compounds. For example, as a complex biopolymer, the lignin crosslinks with the phenylpropanoid units in plant secondary cell walls. The lignin biosynthesis requires the cytochrome P450 enzymes located in the endoplasmic reticulum to establish the structural characteristics of its monomeric precursors (Gou et al., 2018; Morgan et al., 2019). In addition, phenylalanine, tyrosine, and phenylpropane biosynthesis pathways also affect lignin synthesis (Liu et al., 2018). In this study, the lignin content of mutant bk5 was also higher than that of WT. In BSA-seq analysis, we identified a gene coding a polypeptide 11 in subfamily B of Cytochrome p450 (Zm00001d014121), while a phenylalanine metabolism (Ko00360) and a cellular aromatic compound metabolic process (GO:0006725) were enriched in KEGG analysis and GO enrichment analysis in RNA-seq, respectively. These pathways or corresponding genes may be associated with the lignin synthesis, which in turn affect the brittle stalk phenotype of maize. Certainly, further investigations are required to shed light on some key critical issues. In conclusion, some genes and metabolism pathways possibly related to the brittle stalk phenotype were identified by RNA-seq and BSA-seq analysis, which provide an important reference for further understanding of the molecular mechanisms regulating the brittle stalk phenotype in maize.

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The name of the repository and accession number(s) can be found below: National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) BioProject, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/, PRJNA794286 and PRJNA794303.

WH and GS designed and supervised the study. JL, CS, XY, YY, and BF constructed the materials. JL, SG, and QL determined phenotypic data and cell wall composition. JL, CS, XC, and SG performed the BSA-seq and RNA-seq analysis. JL, YZ, and YX performed RNA isolation and qRT-PCR experiments. ZG and XD contributed to revising the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by the Basic Research Funds of JAAS (KYJF2021ZR013) and the Innovation Project of Agricultural Science and Technology in Jilin Province.

YY and BF were employed by the company Hulun Buir Agricultural Reclamation Technology Development Co., Ltd.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

We express our gratitude to the reviewers for their helpful comments to improve the manuscript. We thank Prof. Wei-Bin Song from China Agricultural University for providing maize materials (W22::Mu).

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2022.849421/full#supplementary-material

Anders, S., and Huber, W. (2010). Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 11:R106. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106

Bray, M. R., Johnson, P. E., Gilkes, N. R., McIntosh, L. P., Kilburn, D. G., and Warren, R. A. (1996). Probing the role of tryptophan residues in a cellulose-binding domain by chemical modification. Protein Sci. 5, 2311–2318. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560051117

Brown, D. M., Zeef, L. A., Ellis, J., Goodacre, R., and Turner, S. R. (2005). Identification of novel genes in Arabidopsis involved in secondary cell wall formation using expression profiling and reverse genetics. Plant Cell 17, 2281–2295. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.031542

Burton, R. A., Ma, G., Baumann, U., Harvey, A. J., Shirley, N. J., Taylor, J., et al. (2010). A customized gene expression microarray reveals that the brittle stem phenotype fs2 of barley is attributable to a retroelement in the HvCesA4 cellulose synthase gene. Plant Physiol. 153, 1716–1728. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.158329

Carpita, N. C., Defernez, M., Findlay, K., Wells, B., Shoue, D. A., Catchpole, G., et al. (2001). Cell wall architecture of the elongating maize coleoptile. Plant Physiol. 127, 551–565. doi: 10.1104/pp.010146

Ching, A., Dhugga, K. S., Appenzeller, L., Meeley, R., Bourett, T. M., Howard, R. J., et al. (2006). Brittle stalk 2 encodes a putative glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored protein that affects mechanical strength of maize tissues by altering the composition and structure of secondary cell walls. Planta 224, 1174–1184. doi: 10.1007/s00425-006-0299-8

Dai, X., You, C., Chen, G., Li, X., Zhang, Q., and Wu, C. (2011). OsBC1L4 encodes a COBRA-like protein that affects cellulose synthesis in rice. Plant Mol. Biol. 75, 333–345. doi: 10.1007/s11103-011-9730-z

Deng, Q., Kong, Z., Wu, X., Ma, S., Yuan, Y., Jia, H., et al. (2019). Cloning of a COBL gene determining brittleness in diploid wheat using a MapRseq approach. Plant Sci. 285, 141–150. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2019.05.011

Fekih, R., Takagi, H., Tamiru, M., Abe, A., Natsume, S., Yaegashi, H., et al. (2013). MutMap+: genetic mapping and mutant identification without crossing in rice. PLoS One 8:e68529. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068529

Gou, M., Ran, X., Martin, D. W., and Liu, C. J. (2018). The scaffold proteins of lignin biosynthetic cytochrome P450 enzymes. Nat. Plants 4, 299–310. doi: 10.1038/s41477-018-0142-9

Hatfield, R. D., Jung, H.-J. G., Ralph, J., Buxton, D. R., and Weimer, P. J. (1994). A comparison of the insoluble residues produced by the Klason lignin and acid detergent lignin procedures. J. Sci. Food Agric. 65, 51–58. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.2740650109

Hill, J. T., Demarest, B. L., Bisgrove, B. W., Gorsi, B., Su, Y. C., and Yost, H. J. (2013). MMAPPR: mutation mapping analysis pipeline for pooled RNA-seq. Genome Res. 23, 687–697. doi: 10.1101/gr.146936.112

Jiao, S., Hazebroek, J. P., Chamberlin, M. A., Perkins, M., Sandhu, A. S., Gupta, R., et al. (2019). Chitinase-like1 plays a role in stalk tensile strength in maize. Plant Physiol. 181, 1127–1147. doi: 10.1104/pp.19.00615

Kokubo, A., Kuraishi, S., and Sakurai, N. (1989). Culm strength of barley: correlation among maximum bending stress, cell wall dimensions, and cellulose content. Plant Physiol. 91, 876–882. doi: 10.1104/pp.91.3.876

Kubo, M., Udagawa, M., Nishikubo, N., Horiguchi, G., Yamaguchi, M., Ito, J., et al. (2005). Transcription switches for protoxylem and metaxylem vessel formation. Genes Dev. 19, 1855–1860. doi: 10.1101/gad.1331305

Langham, D. G. (1940) The inheritance of intergeneric differences in zea-euchlaena hybrids. Genetics 25, 88–107. doi: 10.1093/genetics/25.1.88

Li, H., and Durbin, R. (2009). Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324

Li, K., Wang, H., Hu, X., Ma, F., Wu, Y., Wang, Q., et al. (2017). Genetic and quantitative trait locus analysis of cell wall components and forage digestibility in the zheng58 × HD568 maize RIL population at anthesis stage. Front. Plant Sci. 8:1472. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01472

Li, P., Liu, Y., Tan, W., Chen, J., Zhu, M., Lv, Y., et al. (2019). Brittle culm 1 encodes a COBRA-like protein involved in secondary cell wall cellulose biosynthesis in sorghum. Plant Cell Physiol. 60, 788–801. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcy246

Li, S., Ge, F. R., Xu, M., Zhao, X. Y., Huang, G. Q., Zhou, L. Z., et al. (2013). Arabidopsis COBRA-LIKE 10, a GPI-anchored protein, mediates directional growth of pollen tubes. Plant J. 74, 486–497. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12139

Li, Y., Qian, Q., Zhou, Y., Yan, M., Sun, L., Zhang, M., et al. (2003). BRITTLE CULM1, which encodes a COBRA-like protein, affects the mechanical properties of rice plants. Plant Cell 15, 2020–2031. doi: 10.1105/tpc.011775

Liu, F., Ahmed, Z., Lee, E. A., Donner, E., Liu, Q., Ahmed, R., et al. (2012). Allelic variants of the amylose extender mutation of maize demonstrate phenotypic variation in starch structure resulting from modified protein-protein interactions. J. Exp. Bot. 63, 1167–1183. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err341

Liu, Q., Luo, L., and Zheng, L. (2018). Lignins: biosynthesis and biological functions in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19:335. doi: 10.3390/ijms19020335

Liu, X., Hu, X., Li, K., Liu, Z., Wu, Y., Wang, H., et al. (2020). Genetic mapping and genomic selection for maize stalk strength. BMC Plant Biol. 20:196. doi: 10.1186/s12870-020-2270-4

Livak, K. J., and Schmittgen, T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative pcr. Methods 25, 402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262

Mao, X., Cai, T., Olyarchuk, J. G., and Wei, L. (2005). Automated genome annotation and pathway identification using the KEGG Orthology (KO) as a controlled vocabulary. Bioinformatics 21, 3787–3793. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti430

McKenna, A., Hanna, M., Banks, E., Sivachenko, A., Cibulskis, K., Kernytsky, A., et al. (2010). The genome analysis toolkit: a mapreduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 20, 1297–1303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110

Morgan, K., Martucci, N., Kozlowska, A., Gamal, W., Brzeszczyński, F., Treskes, P., et al. (2019). Chlorpromazine toxicity is associated with disruption of cell membrane integrity and initiation of a pro-inflammatory response in the HepaRG hepatic cell line. Biomed. Pharmacother. 111, 1408–1416. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.01.020

Multani, D. S., Briggs, S. P., Chamberlin, M. A., Blakeslee, J. J., Murphy, A. S., and Johal, G. S. (2003). Loss of an MDR transporter in compact stalks of maize br2 and sorghum dw3 mutants. Science 302, 81–84. doi: 10.1126/science.1086072

Nestler, J., Liu, S., Wen, T. J., Paschold, A., Marcon, C., Tang, H. M., et al. (2014). Roothairless5, which functions in maize (Zea mays L.) root hair initiation and elongation encodes a monocot-specific NADPH oxidase. Plant J. 79, 729–740. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12578

Noda, S., Koshiba, T., Hattori, T., Yamaguchi, M., Suzuki, S., and Umezawa, T. (2015). The expression of a rice secondary wall-specific cellulose synthase gene, OsCesA7, is directly regulated by a rice transcription factor, OsMYB58/63. Planta 242, 589–600. doi: 10.1007/s00425-015-2343-z

Persson, S., Paredez, A., Carroll, A., Palsdottir, H., Doblin, M., Poindexter, P., et al. (2007). Genetic evidence for three unique components in primary cell-wall cellulose synthase complexes in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 15566–15571. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706592104

Persson, S., Wei, H., Milne, J., Page, G. P., and Somerville, C. R. (2005). Identification of genes required for cellulose synthesis by regression analysis of public microarray data sets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 8633–8638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503392102

Polko, J. K., and Kieber, J. J. (2019). The regulation of cellulose biosynthesis in plants. Plant Cell 31, 282–296. doi: 10.1105/tpc.18.00760

Roudier, F., Schindelman, G., DeSalle, R., and Benfey, P. N. (2002). The COBRA family of putative GPI-anchored proteins in Arabidopsis. A new fellowship in expansion. Plant Physiol. 130, 538–548. doi: 10.1104/pp.007468

Sánchez-Rodríguez, C., Bauer, S., Hématy, K., Saxe, F., Ibáñez, A. B., Vodermaier, V., et al. (2012). Chitinase-like1/pom-pom1 and its homolog CTL2 are glucan-interacting proteins important for cellulose biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 24, 589–607. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.094672

Sato, K., Ito, S., Fujii, T., Suzuki, R., Takenouchi, S., Nakaba, S., et al. (2010). The carbohydrate-binding module (CBM)-like sequence is crucial for rice CWA1/BC1 function in proper assembly of secondary cell wall materials. Plant Signal. Behav. 5, 1433–1436. doi: 10.4161/psb.5.11.13342

Sindhu, A., Langewisch, T., Olek, A., Multani, D. S., McCann, M. C., Vermerris, W., et al. (2007). Maize brittle stalk2 encodes a COBRA-like protein expressed in early organ development but required for tissue flexibility at maturity. Plant Physiol. 145, 1444–1459. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.102582

Somerville, C. (2006). Cellulose synthesis in higher plants. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 22, 53–78. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.022206.160206

Tanaka, K., Murata, K., Yamazaki, M., Onosato, K., Miyao, A., and Hirochika, H. (2003). Three distinct rice cellulose synthase catalytic subunit genes required for cellulose synthesis in the secondary wall. Plant Physiol. 133, 73–83. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.022442

Tang, H. M., Liu, S., Hill-Skinner, S., Wu, W., Reed, D., Yeh, C. T., et al. (2014). The maize brown midrib2 (bm2) gene encodes a methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase that contributes to lignin accumulation. Plant J. 77, 380–392. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12394

Taylor, N. G., Howells, R. M., Huttly, A. K., Vickers, K., and Turner, S. R. (2003). Interactions among three distinct CesA proteins essential for cellulose synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 1450–1455. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337628100

Vanholme, R., De Meester, B., Ralph, J., and Boerjan, W. (2019). Lignin biosynthesis and its integration into metabolism. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 56, 230–239. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2019.02.018

Vinayan, M. T., Seetharam, K., Babu, R., Zaidi, P. H., Blummel, M., and Nair, S. K. (2021). Genome wide association study and genomic prediction for stover quality traits in tropical maize (Zea mays L.). Sci. Rep. 11:686. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-80118-2

Wang, X., Shi, Z., Zhang, R., Sun, X., Wang, J., Wang, S., et al. (2020). Stalk architecture, cell wall composition, and QTL underlying high stalk flexibility for improved lodging resistance in maize. BMC Plant Biol. 20:515. doi: 10.1186/s12870-020-02728-2

Wu, B., Zhang, B., Dai, Y., Zhang, L., Shang-Guan, K., Peng, Y., et al. (2012). Brittle culm15 encodes a membrane-associated chitinase-like protein required for cellulose biosynthesis in rice. Plant Physiol. 159, 1440–1452. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.195529

Xiong, G., Li, R., Qian, Q., Song, X., Liu, X., Yu, Y., et al. (2010). The rice dynamin-related protein DRP2B mediates membrane trafficking, and thereby plays a critical role in secondary cell wall cellulose biosynthesis. Plant J. 64, 56–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04308.x

Yang, C., Li, D., Liu, X., Ji, C., Hao, L., Zhao, X., et al. (2014). OsMYB103L, an R2R3-MYB transcription factor, influences leaf rolling and mechanical strength in rice (Oryza sativa L.). BMC Plant Biol. 14:158. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-14-158

Young, M. D., Wakefield, M. J., Smyth, G. K., and Oshlack, A. (2010). Gene ontology analysis for RNA-seq: accounting for selection bias. Genome Biol. 11:R14. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-2-r14

Zhang, M., Zhang, B., Qian, Q., Yu, Y., Li, R., Zhang, J., et al. (2010). Brittle Culm 12, a dual-targeting kinesin-4 protein, controls cell-cycle progression and wall properties in rice. Plant J. 63, 312–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04238.x

Zhang, Y., Liang, T., Chen, M., Zhang, Y., Wang, T., Lin, H., et al. (2019). Genetic dissection of stalk lodging-related traits using an IBM Syn10 DH population in maize across three environments (Zea mays L.). Mol. Genet. Genomics 294, 1277–1288. doi: 10.1007/s00438-019-01576-6

Zhang, Y., Nikolovski, N., Sorieul, M., Vellosillo, T., McFarlane, H. E., Dupree, R., et al. (2016). Golgi-localized STELLO proteins regulate the assembly and trafficking of cellulose synthase complexes in Arabidopsis. Nat. Commun. 7:11656. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11656

Keywords: maize, brittle stalk, cellulose and lignin synthesis, RNA-seq, BSA-seq

Citation: Liu J, Sun C, Guo S, Yin X, Yuan Y, Fan B, Lv Q, Cai X, Zhong Y, Xia Y, Dong X, Guo Z, Song G and Huang W (2022) Genomic and Transcriptomic Analyses Reveal Pathways and Genes Associated With Brittle Stalk Phenotype in Maize. Front. Plant Sci. 13:849421. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.849421

Received: 06 January 2022; Accepted: 21 March 2022;

Published: 25 April 2022.

Edited by:

Apichart Vanavichit, Kasetsart University, ThailandReviewed by:

Chang-Sheng Wang, National Chung Hsing University, TaiwanCopyright © 2022 Liu, Sun, Guo, Yin, Yuan, Fan, Lv, Cai, Zhong, Xia, Dong, Guo, Song and Huang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Guangshu Song, MTM4NDQwODMxOThAMTI2LmNvbQ==; Wei Huang, aHVhbmd3ZWkyMDZAY2phYXMuY29t

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.