- The Key Laboratory of Biology and Genetic Improvement of Oil Crops, The Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the PRC, Oil Crops Research Institute of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Wuhan, China

Serine/arginine-rich (SR) proteins are indispensable factors for RNA splicing, and they play important roles in development and abiotic stress responses. However, little information on SR genes in Brassica napus is available. In this study, 59 SR genes were identified and classified into seven subfamilies: SR, SCL, RS2Z, RSZ, RS, SR45, and SC. In each subfamily, the genes showed relatively conserved structures and motifs, but displayed distinct expression patterns in different tissues and under abiotic stress, which might be caused by the varied cis-acting regulatory elements among them. Transcriptome datasets from Pacbio/Illumina platforms showed that alternative splicing of SR genes was widespread in B. napus and the majority of paralogous gene pairs displayed different splicing patterns. Protein-protein interaction analysis indicated that SR proteins were involved in the regulation of the whole lifecycle of mRNA, from synthesis to decay. Moreover, the association mapping analysis suggested that 12 SR genes were candidate genes for regulating specific agronomic traits, which indicated that SR genes could affect the development and hence influence the important agronomic traits of B. napus. In summary, this study provided elaborate information on SR genes in B. napus, which will aid further functional studies and genetic improvement of agronomic traits in B. napus.

Introduction

RNA splicing is an important process in eukaryotes that could produce one or multiple mature mRNAs via different splicing sites, which significantly increases the flexibility of gene expression regulation and the diversity of transcriptome and proteome (Black, 2003). The process is mediated by the spliceosome, a large macromolecule complex composed of five small nuclear ribonucleo-proteins (snRNPs) and a mass of proteins (Will and Luhrmann, 2010). Among these proteins, the serine/arginine-rich (SR) proteins are vital splicing factors to regulate the selections of splicing sites by binding splicing enhancers on the pre-mRNA (Zahler et al., 1992). The structure of SR proteins is conserved, containing one or two RNA binding domains (RBDs) at the N-terminus and an arginine/serine-rich (RS) domain at the C-terminus (Shepard and Hertel, 2009). The RBDs are responsible to recognize and bind to specific RNA regions, while the RS domain contributes to the protein-protein interactions. The subcellular localization of SR proteins is directly related to their molecular functions, and it has been reported that they are localized in the nuclear speckles (Caceres et al., 1997), a subset of them could shuttle between the nucleus and cytoplasm (Sapra et al., 2009).

In plants, SR proteins were initially identified in Arabidopsis (Kalyna and Barta, 2004), then in rice, maize, wheat, tomato, cassava, and so on (Isshiki et al., 2006; Richardson et al., 2011; Yoon et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2019, 2020b; Gu et al., 2020; Rosenkranz et al., 2021). According to sequence similarity, SR proteins could be divided into seven subfamilies: SR, SCL, RS2Z, RSZ, RS, SR45, SC, and three of them (SCL, RS2Z, RS) are plant-specific (Richardson et al., 2011). Subfamily SCL is the largest plant-specific one containing members from dicots, monocots, moss, and green algae. Subfamily RS2Z was mainly composed of dicots and monocots, whereas most members of subfamily RS came from photosynthetic eukaryotes. Many studies have shown that the SR genes play important roles in plant developmental processes and respond to hormonal signaling or environmental stress (Isshiki et al., 2006; Palusa et al., 2007; Reddy and Shad Ali, 2011; Melo et al., 2020). For example, the life cycle of Atsr45-1 was significantly shorter, the leaves of Atsr45-1 were elongated and curly, and the number of petals and stamens was also significantly different from the wild type (Ali et al., 2007). Overexpression of RSZ33 in Arabidopsis can result in developmental abnormalities in embryos and root apical meristem (Kalyna et al., 2003). And knockout SC and SCL in Arabidopsis could affect the transcriptions of many genes, resulting in serrated leaves, late flowering, shorter roots and abnormal silique phyllotaxy (Yan et al., 2017). Most members of the plant-specific SCL are involved in stress responses mediated by exogenous abscisic acid (ABA) (Cruz et al., 2014). In terms of environmental stress, Atsr34B reduces plant tolerance to calcium by regulating the expression of IRT1 (Zhang et al., 2014), while AtRS40 and AtRS41 act as critical modulators under salt stress (Chen et al., 2013).

In addition to regulating the splicing of other genes, SR genes also could be alternatively spliced. A total of 19 SR genes were identified in Arabidopsis (Kalyna and Barta, 2004). Among them, 15 genes could produce 95 transcripts under hormone induction or abiotic stress, which greatly increased the complexity of the SR genes by sixfold (Palusa et al., 2007). There were 21 and 18 SR genes in maize and sorghum, respectively, whereas 92 and 62 transcripts were detected in each of them, and the majority of SR transcripts were not conserved between maize and sorghum (Rauch et al., 2014). SR genes in tomato showed different splicing profiles in various organs as well as in response to heat stress (Rosenkranz et al., 2021). And a variety of AS events occurred in SR genes of Brassica rapa under abiotic stresses (Yoon et al., 2018). Recently, an increasing number of studies focused on the detailed functional and regulatory mechanisms of the varied SR transcripts. Numerous SR transcripts contained premature termination codons (PTCs) which might elicit nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD) to regulate the gene expression (McGlincy and Smith, 2008; Palusa and Reddy, 2010). And other SR transcripts showed distinct biological functions, like salt-responsive gene SR45a could generate two transcripts SR45a-1a and SR45a-1b, the first of which directly interacted with the cap-binding protein 20 (CBP20), whereas the latter promoted the association of SR45a-1a with CBP20, through the fine-tune regulatory mechanism, it was conducive for the plants to response to salt stress (Li et al., 2021).

Brassica napus is an important global oil crop (Chalhoub et al., 2014), which is an allotetraploid species derived from hybridization between B. rapa and Brassica oleracea. To date, it is unclear how many SR genes/transcripts are present in B. napus and how they perform their function to affect the oil crop. Now the genome sequences and various transcriptome datasets of B. napus are available (Chalhoub et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2019; Yao et al., 2020), which provide an ample resource to investigate the specific genes at the genome-wide level. In this study, SR genes were identified in B. napus, the phylogenetic relationship, gene structures, conserved motifs, gene duplications and protein interactions were also analyzed. The transcriptome data from various tissues and environmental stresses were used for the expression patterns and alternative splicing analysis of SR genes in B. napus. Moreover, genetic variations of SR genes in a worldwide core collection germplasm (Tang, 2019) were also investigated, and the association mapping analysis revealed that 12 SR genes were candidate genes for agronomic traits in B. napus. This study expanded our understanding of SR genes in B. napus and provided a foundation for further functional studies.

Materials and Methods

Identification of SR Genes in Brassica napus

The genome and annotation information of the B. napus cultivar ‘‘Darmor-bzh’’ were obtained from the Brassicaceae Database (BRAD)1 (Chalhoub et al., 2014). The amino acid sequences of the SR family in Arabidopsis thaliana (Kalyna and Barta, 2004) were obtained to build a Hidden Markov Model (HMM), and HMMER3.0 (Mistry et al., 2013) was used to search for SR genes in B. napus (E value was set to 1e-5). The NCBI Conserved Domain Database2 (Lu et al., 2020)and the SMART databases3 (Letunic et al., 2020)were used for verification of candidate genes, preserving the ones containing RRM and RS domains. Moreover, ProtParam,4 an online software of SWISS-PROT, was used to predict the molecular weights (MW) and isoelectric point (pI) of SR proteins, and CELLO v2.5 (Yu et al., 2006) was used to predict the subcellular location of these proteins.

Chromosomal Location and Gene Duplication Analysis

The locations of SR genes were obtained from the annotation of B. napus genome. To identify gene duplication events, BLASTP with the e-value of 1e–10 was used to align the sequence, and MCScanX (Wang et al., 2012) was used to detect the duplication patterns including segmental and tandem duplication. Chromosomal locations and duplication events were visualized using the Circos software (Krzywinski et al., 2009). The ratios of non-synonymous to synonymous substitutions (Ka/Ks) of duplicate gene pairs were counted by ParaAT2.0 (Zhang et al., 2012), which aligned the protein sequence by Muscle (Edgar, 2004) and calculated the Ka/Ks ratio by KaKs_Calculator (Wang et al., 2010).

Gene Structure, Conserved Motifs, and cis-Acting Regulatory Elements Analysis

TBtools (Chen et al., 2020a) and Multiple Expectation Maximization for Motif Elicitation (MEME) (Bailey et al., 2015) were used to display the gene structures and to analyze the conserved motifs in SR proteins. To identify the cis-acting regulatory elements of SR genes, promoters (2 kb upstream sequences from initiation codon) were extracted and predicted by PlantCARE5 (Magali, 2002). The location was displayed by Gene Structure Display Server (GSDS 2.0) (Hu et al., 2015), the amount heatmap was visualized by R.6

Phylogenetic Analysis of SR Family Members

To gain insights into the evolutionary relationships of SR family members, multiple sequence alignments of SR amino acids of A. thaliana and B. napus were performed using the ClustalW (Larkin, 2007). Phylogenetic trees were generated with the MEGA 11 program using the Neighbor-Joining (NJ) method with 1,000 bootstrap replications (Tamura et al., 2021). The tree was visualized using Evolview7 (He et al., 2016).

Prediction of Protein-Protein Interactions

The Protein-Protein Interactions of A. thaliana were downloaded from STRING8 (Szklarczyk et al., 2021), the interaction networks of SR proteins in B. napus were predicted based on the homologs in A. thaliana, and Cytoscape (Shannon et al., 2003) was used to display the interaction. To investigate the involved biological process, genes that interacted with SR proteins were taken out for Gene Ontology and KEGG enrichment analysis by clusterProfiler in R (Yu et al., 2012).

Expression Analysis of SR Genes in Brassica napus

Transcriptome data from five tissues (leaf, callus, bud, root, and young silique) and different stress conditions (dehydration, salt, cold and ABA) of B. napus cultivar “ZS11” were used in this study (Zhang et al., 2019; Yao et al., 2020), the expression levels of SR genes were calculated with Stringtie (Pertea et al., 2015) after alignment with Hisat2 (Kim et al., 2015), and displayed by Pheatmap and UpSet in R. And expression patterns of four genes were showed by TBtools-eFP (Chen et al., 2020a).9

Alternative Splicing Analysis of SR Genes in Brassica napus

Based on the two sets of transcriptome data, alternative splicing of SR genes were also investigated. For the transcript isoform catalog of B. napus obtained from Iso-seq (Yao et al., 2020), the AS events were identified by Astalavista (Sylvain and Michael, 2007) and the expression of alternative splicing transcripts of SR genes in various tissues were calculated with Stringtie. For the RNA-seq of different stress conditions (Zhang et al., 2019), transcripts were assembled by Stringtie firstly, then the AS events and the expression of alternative splicing transcripts were counted. In order to verify the AS events between paralogous gene pairs, transcriptome data based on EST sequencing of B. napus were downloaded and analyzed (Troncoso-Ponce et al., 2011).

RNA Isolation and qRT-PCR Analysis of SR Genes

The seeds of B. napus cultivar “ZS11” were germinated and grown in a growth room at 24°C, with a 16/8 h light/dark photoperiod. The leaves and roots were collected from 20-day-old seedlings, while buds were collected from 70-day-old seedings, siliques were harvested 90 days after germination. Samples were immediately stored in liquid nitrogen, and total RNA was extracted from samples using Invitrogen trizol reagent (TRIzol™15596026, United States) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Total RNA was then reverse-transcribed into complementary DNAs by using the PrimeScript RT reagent Kit With gDNA Eraser (Takara, Japan). The complementary DNAs were used as templates in quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) with the gene-specific primers (Supplementary Table 1). qRT-PCR was performed by using SYBR Green Real-time PCR Master Mix (Bio-Rad, United States) in 20 μl reaction mixture and run on CFX96 Real-time PCR system (Bio-Rad, United States). B. napus β-actin gene was used as internal standard. All assays were conducted with three biological repeats, and each with three technical repeats. The relative expression level was obtained using the 2–ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001).

Association Mapping of SR Genes in a Natural Population of Brassica napus

To understand the natural variations of SR genes in B. napus, a natural population with 324 worldwide accessions was used in this study (Tang, 2019). SNPs in the gene regions of SR genes were extracted and annotated by SnpEff (Cingolani et al., 2012). The agronomic traits including primary flowering time (PFT), full flowering time (FFT1), final flowering time (FFT2), early flowering stage (EFS), late-flowering stage (LFS), flowering period (FP), plant height (PH), branch number (BN), branch height (BH), main inflorescence length (MIL), main inflorescence silique number (MISN), main inflorescence silique density (MISD) were selected (Tang, 2019). With the mixed linear model, a family-based association mapping analysis considering population structure and relative kinship was performed by EMMAX (Kang et al., 2010). The linkage disequilibrium and haplotype blocks were made by LDBlockShow (Dong et al., 2020) and the enriched Gene Ontology terms of interacted proteins were drawn by Cytoscape (Shannon et al., 2003).

Results

SR Genes Form Seven Subfamilies in Brassica napus

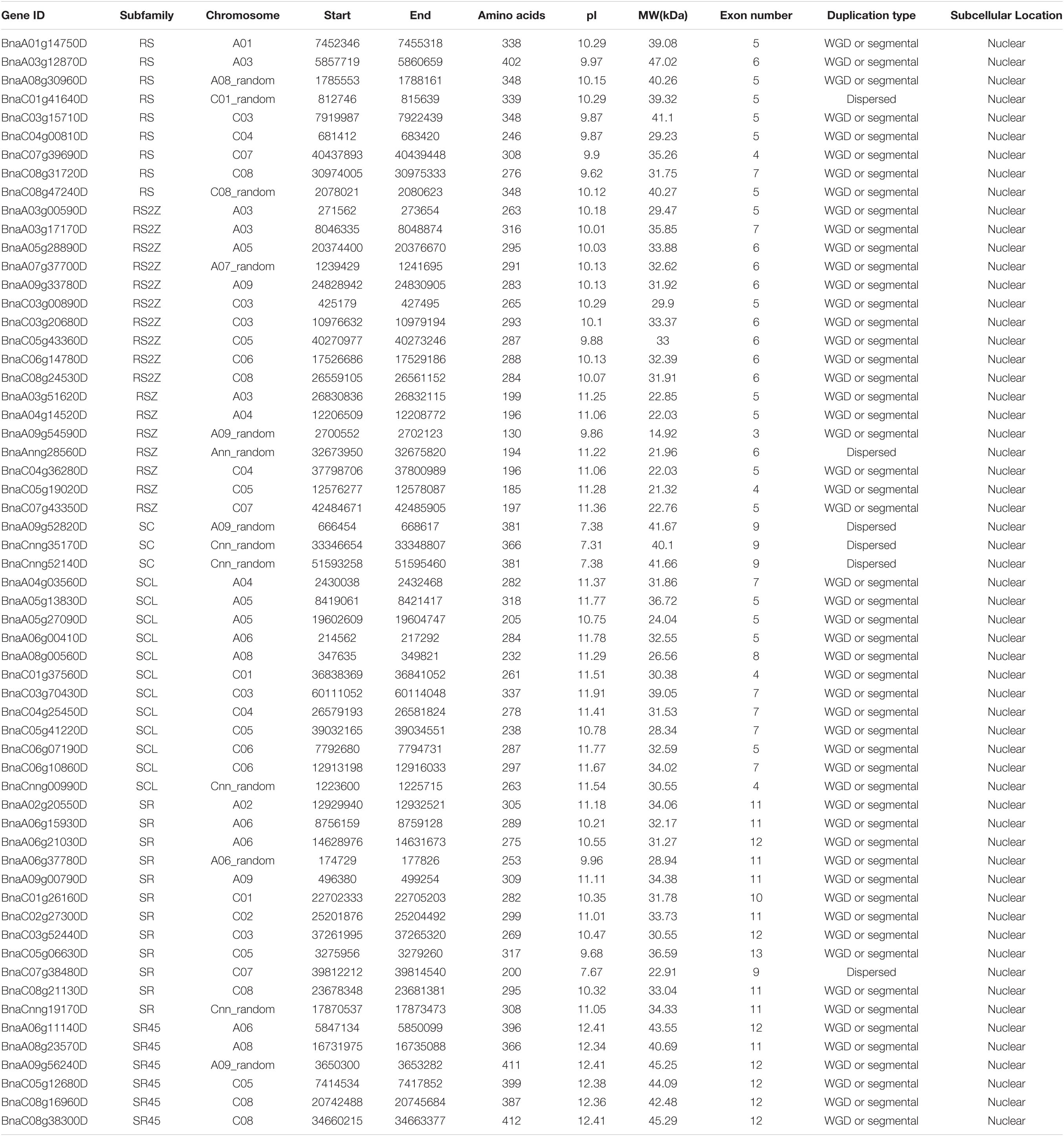

After performing HMM search and domain verification, a total of 59 SR genes were identified in B. napus. The detailed information of each SR was listed in Table 1, including gene ID, genomic location, amino acids (AA) length, isoelectric point (pI), and molecular weight (MW) and so on. The lengths of SR proteins ranged from 130 to 412 AA, with an average length of 293 AA. The pI values were varied from 7.31 to 12.41 and the MW values were varied from 14.92 to 47.02 kDa. According to the prediction of CELLO, it showed that all the SR proteins were located in nuclear.

To understand the evolutionary relationships of SR genes between B. napus and A. thaliana, a phylogenetic tree was constructed based on their protein sequences. Finally, 19 AtSRs and 59 BnSRs were clustered into seven subfamilies (Figure 1 and Table 1). According to the previous nomenclature system, subfamily SR, SCL, RS2Z, RSZ, RS, SR45, and SC were also used in this study. Subfamily SCL and SR were the largest, each of which included 12 SR genes, while subfamily SC was the smallest, with only 3 SR genes, and the other subfamily RS2Z, RS, RSZ, and SR45 contained 10, 9, 7, and 6 SR genes, respectively.

Figure 1. Phylogenetic analysis of SR proteins in B. napus and A. thaliana. All SR proteins were clustered into seven subfamilies, and each subfamily was represented by a different color.

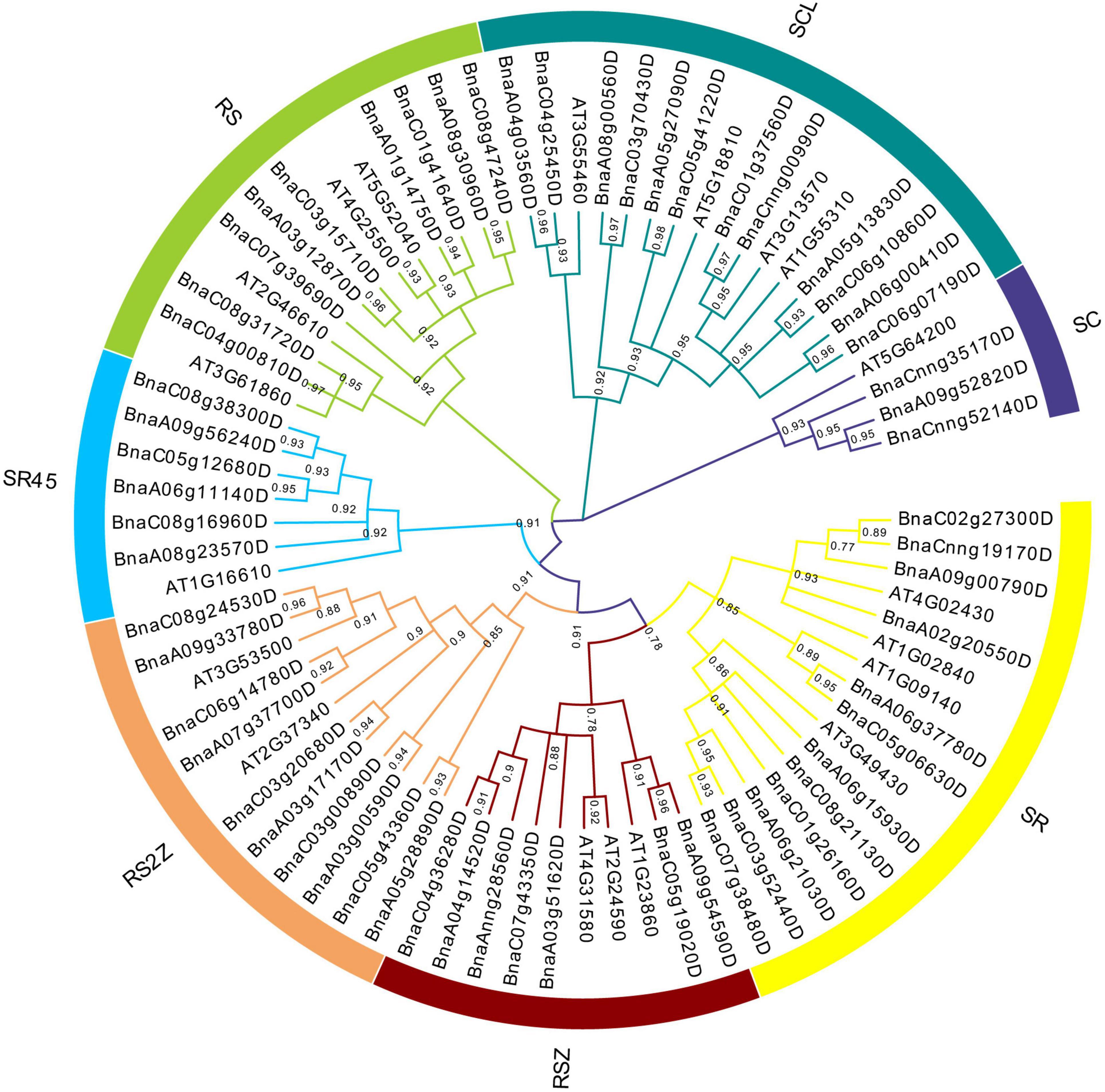

Chromosomal Distribution and Gene Duplication of SR Genes in Brassica napus

In B. napus, 46 of 59 SR genes were unevenly distributed over 19 chromosomes, while the other 13 SR genes were assigned to unanchored scaffolds (Figure 2). In total, 26 and 33 SR genes were located on the A subgenome and C subgenome, respectively. There were 5 SR, 5 SCL, 5 RS2Z, 4 RSZ, 3 SR45, 3 RS, and 1 SC subfamily genes on A subgenome, with compared to 7 SR, 7 SCL, 5 RS2Z, 3 RSZ, 3 SR45, 6 RS, and 2 SC on C subgenome. Chromosomes C03, C05, and C08 had the most SR genes (5 genes per chromosome), while chromosomes A01, A02, and C02 contained only one SR gene, respectively, and no SR gene was located on chromosomes A07, A10, and C09.

Figure 2. The chromosomal distribution and duplication analysis of SR genes in B. napus. The locations of all the chromosomal SR genes were shown in different chromosomes. The different colors indicated different subfamilies of the SR genes. The orange lines highlighted the duplicated SR gene pairs.

According to BLAST and MCScanX, gene duplication events of the SR genes were detected in B. napus. In short, all 59 SR genes were derived from duplication (Table 1), 89.83% of them (53 SR genes) were originated from whole-genome duplication (WGD) or segmental duplications, while the other 6 SR genes resulted from dispersed duplications. Moreover, there were 91 paralogous gene pairs in B. napus (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 2), 15 of them occurred in the A subgenome, 21 of them took place in the C subgenome, and the other 55 duplication events occurred between the A and C subgenome. To estimate the selection mode of SR genes in B. napus, the ratios of non-synonymous to synonymous substitutions (Ka/Ks) for paralogous gene pairs were calculated. Generally, Ka/Ks > 1 means positive selection, Ka/Ks = 1 means neutral selection, and Ka/Ks < 1 represents purifying selection. In this work, Ka/Ks ratios of all the paralogous gene pairs were less than 1, suggesting that SR genes were under purifying selection (Supplementary Table 2).

Gene Structure, Conserved Motifs, and cis-Acting Regulatory Elements Analysis of SR Genes in Brassica napus

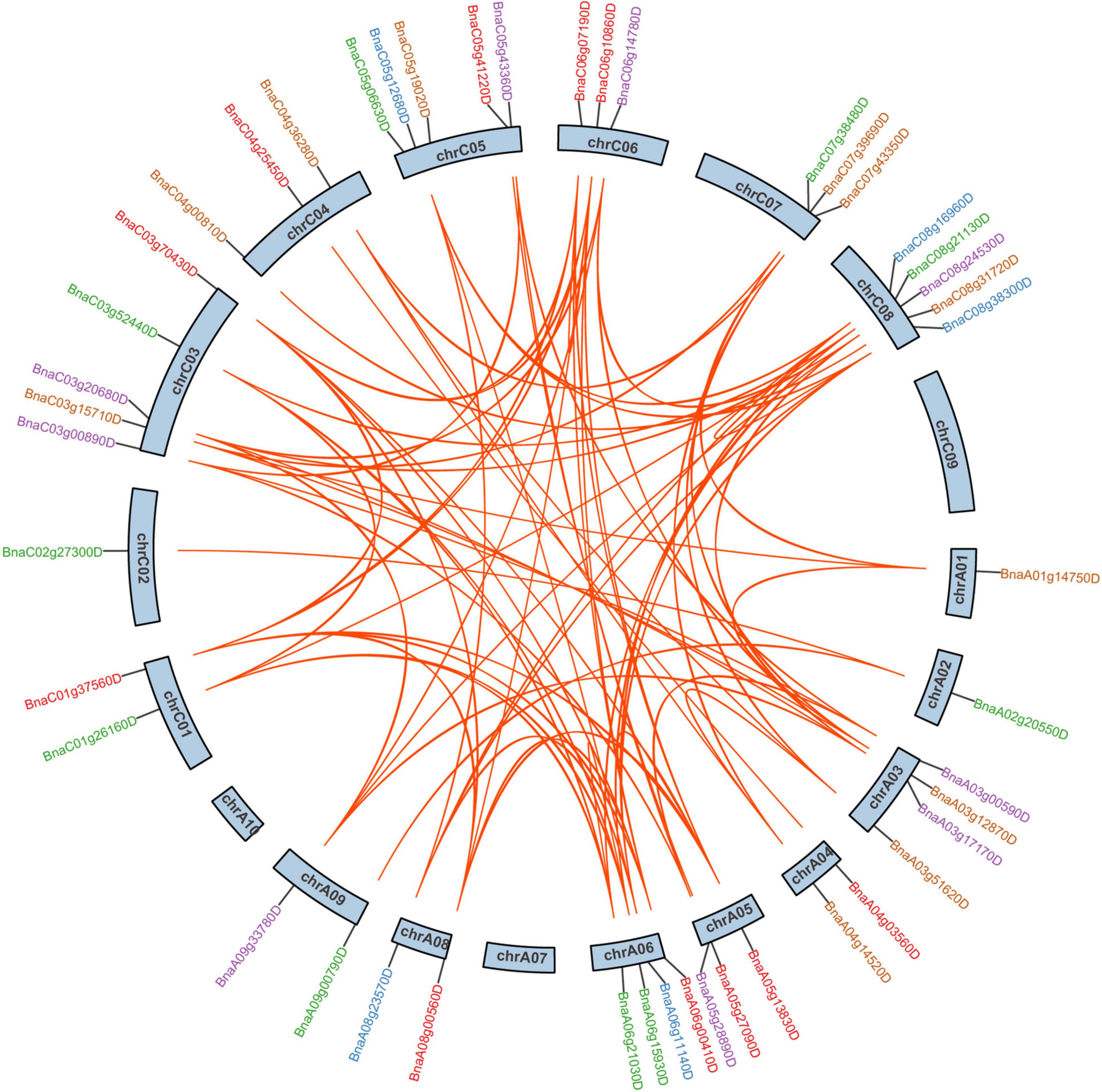

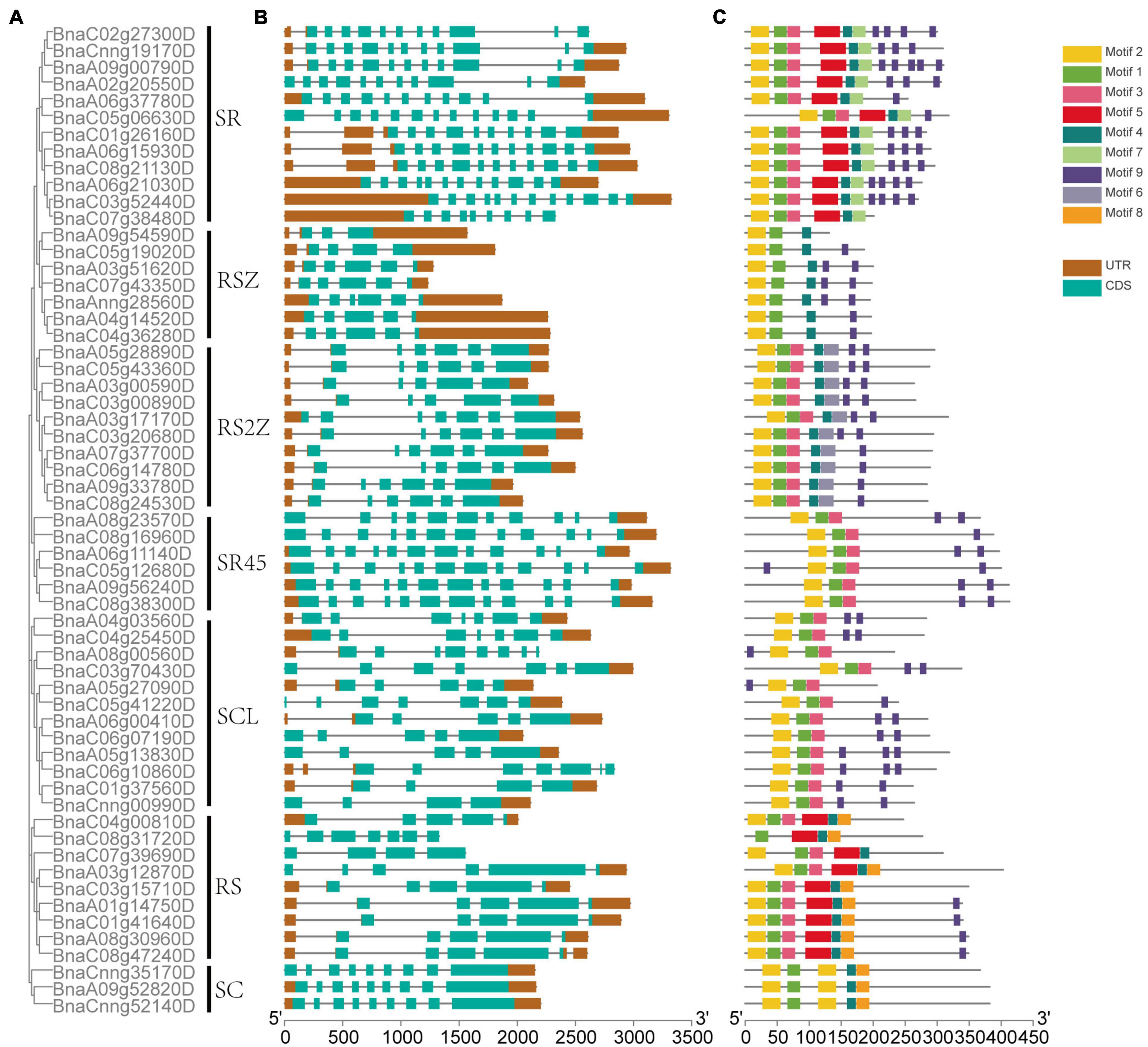

The exon-intron structure of 59 SR genes in seven subfamilies was displayed (Figures 3A,B), On average, each gene included 7 exons, but the exon numbers differed widely, ranging from 3 to 13, and different subfamilies exhibited different exon numbers. While the genes in the same subfamily tended to possess similar gene structures, for example, in subfamily SC, all the SR genes had 9 exons, and in subfamily SR45, all the SR genes contained 12 exons except BnaA08g23570D.

Figure 3. The phylogenetic relationship, gene structure, and conserved motifs of SR genes in B. napus. (A) The phylogenetic relationships of 59 SR proteins based on the NJ method. (B) Gene structures of the SR genes. Dark brown boxes represented UTR, and indigo boxes represented CDS. (C) The motif composition of SR proteins. Numbers 1–9 were displayed in different colored boxes.

In total, 9 conserved motifs were identified in 59 SR genes (Figure 3C). All the SR genes contained motif 1 and motif 2 except BnaC08g31720D, which lacked motif 1. All the SR genes possessed motif 9, except those in subfamily SC. Apparently, the motif structures of distinct subfamilies varied. For example, the pattern of subfamily SC was motif 2-1-2-4-8, while subfamily RS2Z was motif 2-1-3-4-6-9. And some subfamilies had a few specific motifs, like motif 7 was unique to subfamily SR, motif 8 only existed in subfamily RS2Z.

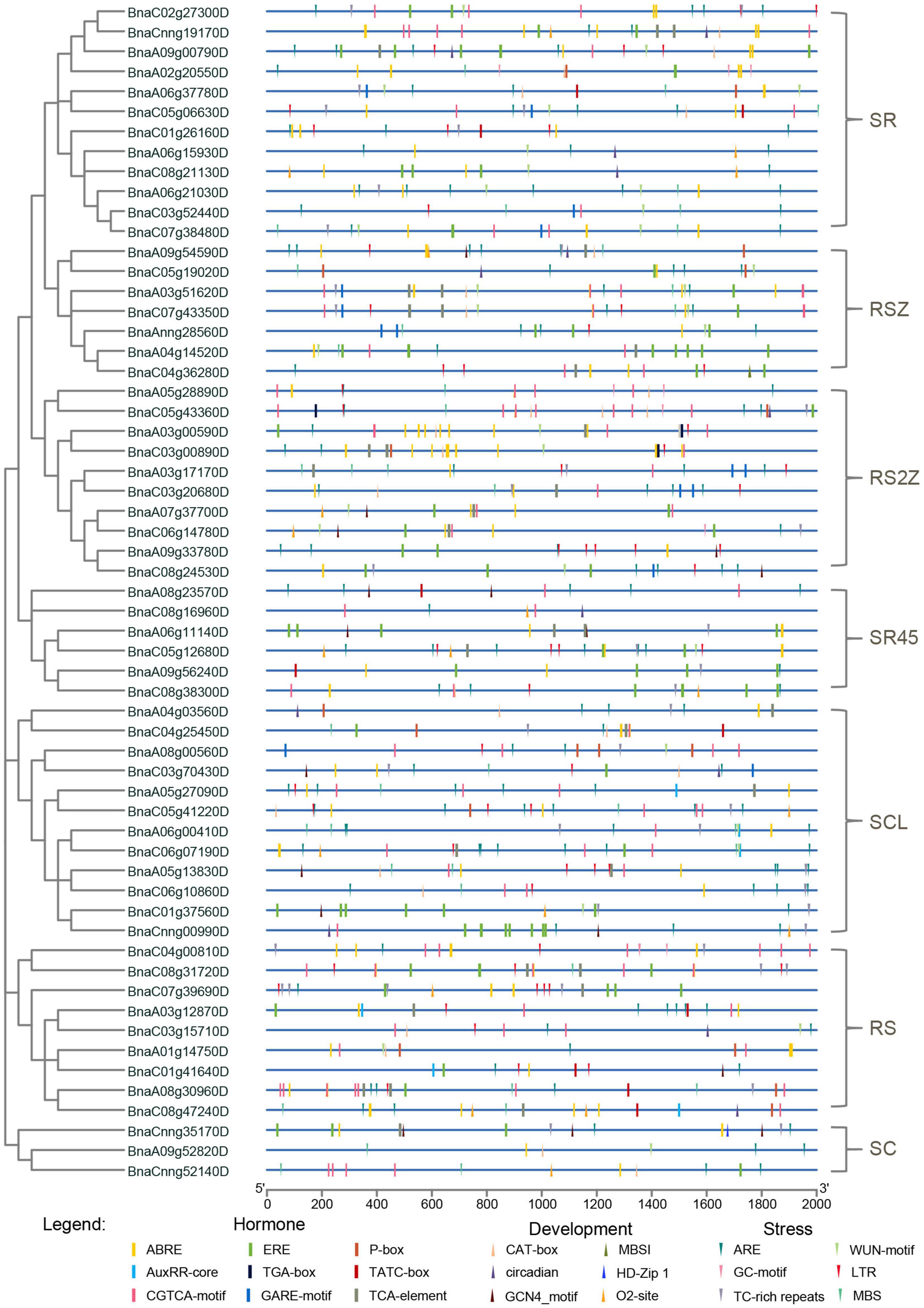

Promoter regions were found to be critical for gene expression (Oudelaar and Higgs, 2021), so cis-acting regulatory elements in these regions were investigated for SR genes. Cis-acting regulatory elements related to stress, hormone and development (ranging from 5 to 23) were detected in promoters of SR genes (Figure 4, Supplementary Figure 1, and Supplementary Table 3). The majority of SR genes (56/59, 94.92%) contained ARE elements, which is essential for anaerobic induction. Moreover, stress-responsive elements such as TC-rich repeats (involved in defense and stress responsiveness, 33/59, 55.93%), LTR (involved in low-temperature responsiveness, 33/59, 55.93%) and MBS (involved in drought-inducibility, 29/59, 49.15%) were also common in promoters of SR genes. Hormone-responsive elements like ABRE (involved in the abscisic acid responsiveness), CGTCA-motif (involved in the MeJA-responsiveness) and ERE (involved in the ethylene responsiveness) existed in most promoters of SR genes. In terms of development-related elements, CAT-box (24/59, 40.68%), which is related to meristem expression, was most frequently observed in the promoters of SR genes. The results indicated that many SR genes in B. napus were responsible for plant growth and stress response.

Figure 4. Cis-acting regulatory elements identified in promoters of SR genes in B. napus. Boxes indicated hormone-related elements, up-triangles indicated development-related elements, and down-triangles indicated stress-related elements. Different colors indicated different elements.

Predicted Protein Interactions of SR Proteins in Brassica napus

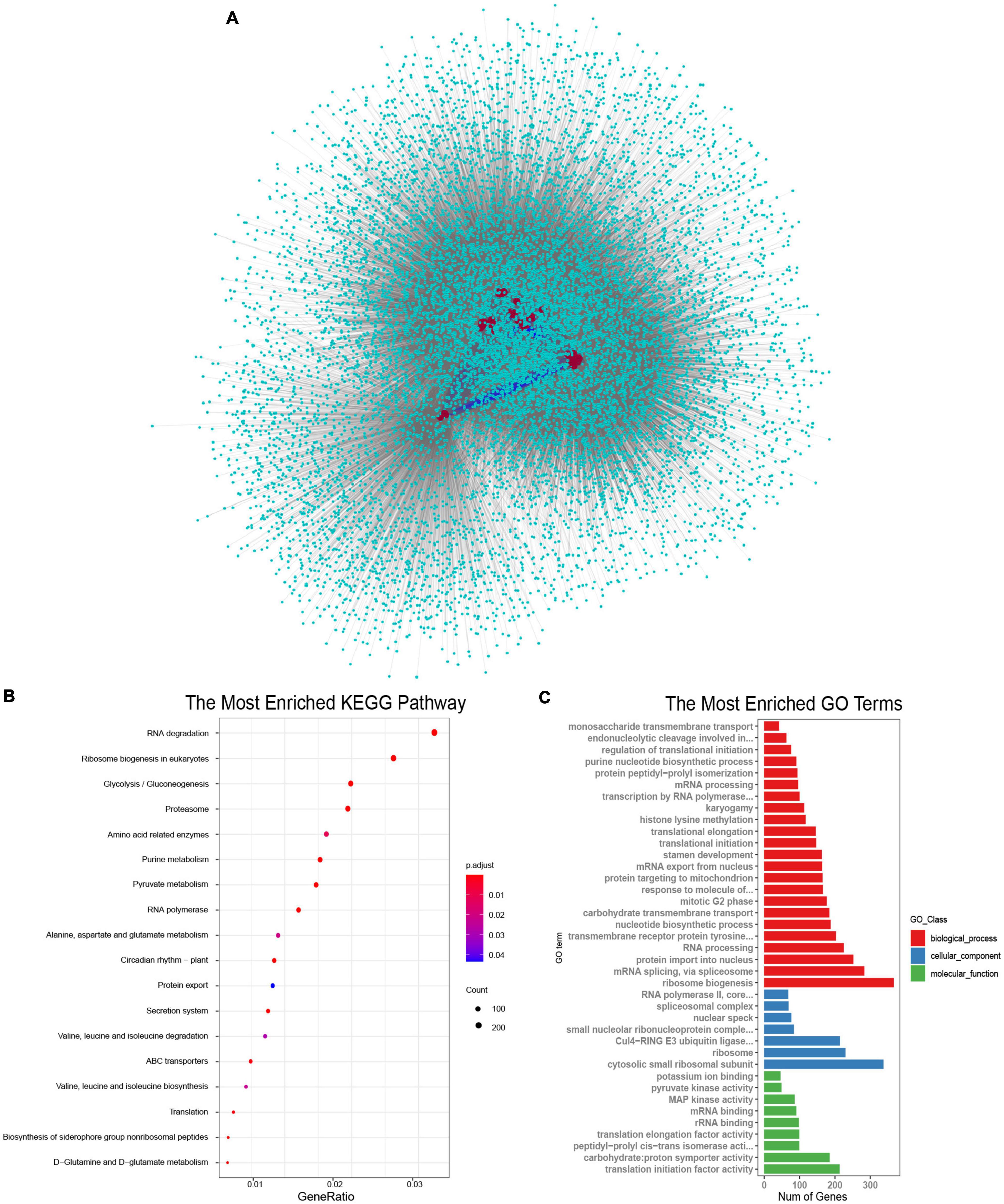

SR proteins were the key components of the spliceosome and they always interacted with other proteins to perform their functions (Shepard and Hertel, 2009; Will and Luhrmann, 2010). To understand the biological processes involved by SR proteins in B. napus, interaction networks were predicted according to known protein interactions in Arabidopsis. The homologous proteins of 59 BnSR proteins interacted with 3,528 proteins in Arabidopsis, which were homologous to 13,591 proteins in B. napus (Figure 5A). It demonstrated that SR proteins were the core nodes in the network, most SR proteins interacted with each other, meanwhile, they also interacted with other proteins to participate in different biological processes. KEGG enrichment analysis showed these interacted proteins were involved in a variety of processes including RNA degradation, ribosome biogenesis, RNA polymerase, proteasome, circadian rhythm, and so on (Figure 5B and Supplementary Table 4). Gene Ontology enrichment analysis (Figure 5C and Supplementary Table 5) showed that ribosome biogenesis, mRNA splicing and protein import into the nucleus were the significantly enriched terms in the biological process category. While the terms including cytosolic small ribosomal subunit and ribosome in the cellular component category were highly enriched, and in the molecular function category, translation initiation factor activity, proton symporter activity and RNA binding were significantly enriched. Protein-protein interactions analysis showed that SR proteins played important roles in the regulation of the whole lifecycle of mRNA, from synthesis to decay.

Figure 5. Proteins interacted with SR proteins in B. napus. (A) Protein-protein interaction network of SR proteins in B. napus. The red circles represented the SR proteins, the indigo circles represented proteins that interacted with SR proteins. The blue lines represented the interaction between SR proteins, and the gray lines represented the interaction between SR proteins and other proteins. (B) KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of proteins interacted with SR proteins. (C) Gene Ontology enrichment analysis of proteins interacted with SR proteins.

Various Expression Patterns of SR Genes in Different Tissues and Under Abiotic Stresses in Brassica napus

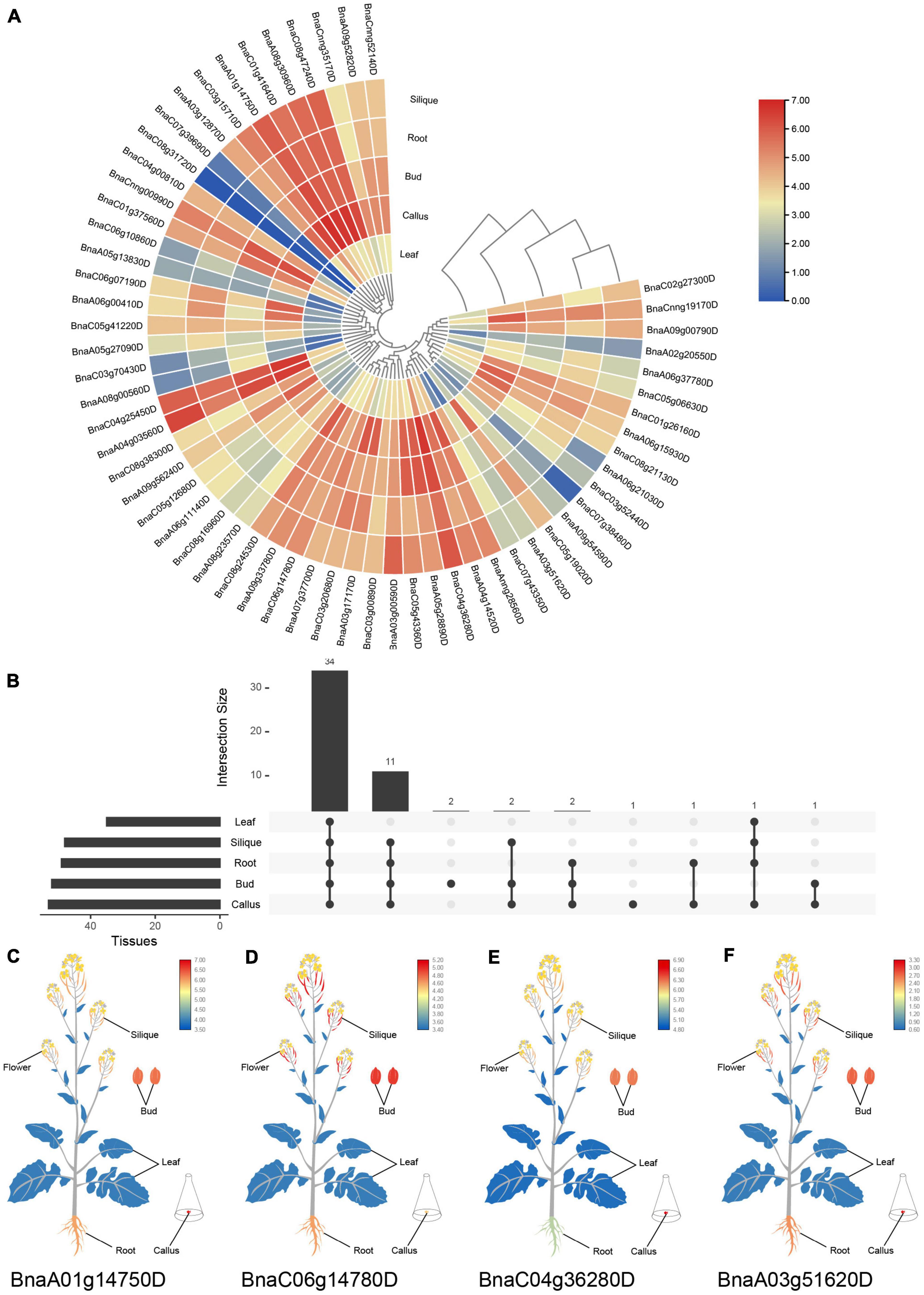

To predict the potential functions of SR genes, expression patterns based on RNA-Seq of five tissues in B. napus cultivar “ZS11” (Yao et al., 2020) were displayed in Figure 6. SR genes showed different expression patterns among the five tissues. The expression profiles of SR genes in the silique and root displayed similar patterns. Almost all the SR genes were expressed highly in bud, root, silique and callus, but lowly in leaf (Figure 6A). There was 34 SR genes expressed in all of the five tissues based on the threshold value (FPKM > 5), and some of the SR genes were tissue-specific or preferential expression (Figure 6B). Like BnaA01g14750D showed the highest expression in callus (Figure 6C), and BnaC06g14780D expressed at a high level in silique and bud (Figure 6D), nevertheless, both of them expressed lowly in leaf. Meanwhile, a few SR genes expressed highly in callus and lowly in silique. And two SR genes (BnaC08g31720D and BnaC07g39690D) barely expressed in these five tissues.

Figure 6. Expression profiles of SR genes in different tissues of B. napus. (A) Heatmap representation of 59 SR genes in different tissues. (B) Number of SR genes that were expressed in various tissues. (C–F) The expression patterns of four selected SR genes in B. napus plants. Expression data were processed with log2 normalization. The color scale represented relative expression levels from low (blue color) to high (red color).

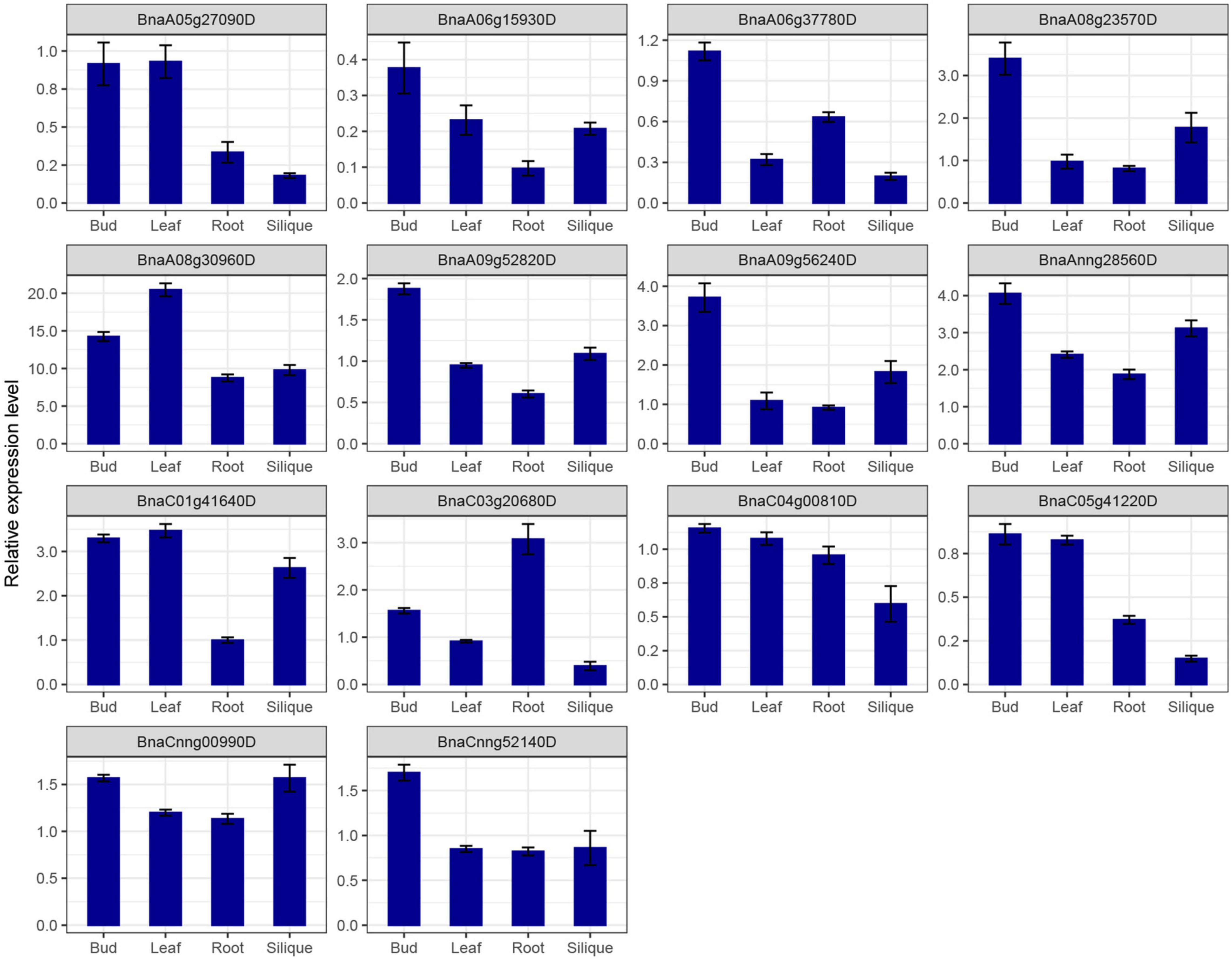

SR genes in subfamily RS2Z, SR45, and SC showed similar expression patterns, paralogous gene pairs in these subfamilies also owned similar expression patterns, like BnaA09g33780D/BnaC06g14780D in RS2Z, BnaA06g11140D/BnaC05g12680D in SR45. Nevertheless, in other subfamilies, different patterns were observed, for example, paralogous gene pairs (BnaA04g03560D/BnaC04g25450D) in subfamily SCL expressed at the same pattern, while in subfamily RS BnaC08g31720D barely expressed in five tissues, its paralogous gene BnaC04g00810D expressed at a high level in callus, bud, root and silique, and in subfamily RSZ, BnaC04g36280D and its paralogous gene BnaA04g14520D expressed at a high level in each tissue (Figure 6E), but their paralogous gene BnaA03g51620D and BnaC07g43350D weakly expressed (Figure 6F). Moreover, 14 SR genes from different subfamilies were selected for qRT-PCR analysis (Figure 7 and Supplementary Table 1), similarly, most of these genes expressed higher in bud, and the expression patterns of two genes (BnaA09g52820D and BnaCnng52140D) from subfamily SC were almost the same, while in subfamily SCL, BnaCnng00990D showed different expression patterns with BnaA05g27090D and BnaC05g41220D.

Figure 7. qRT-PCR expression analysis of 14 SR genes in different tissues of B. napus. The error bars represented the standard error of the means of three replicates.

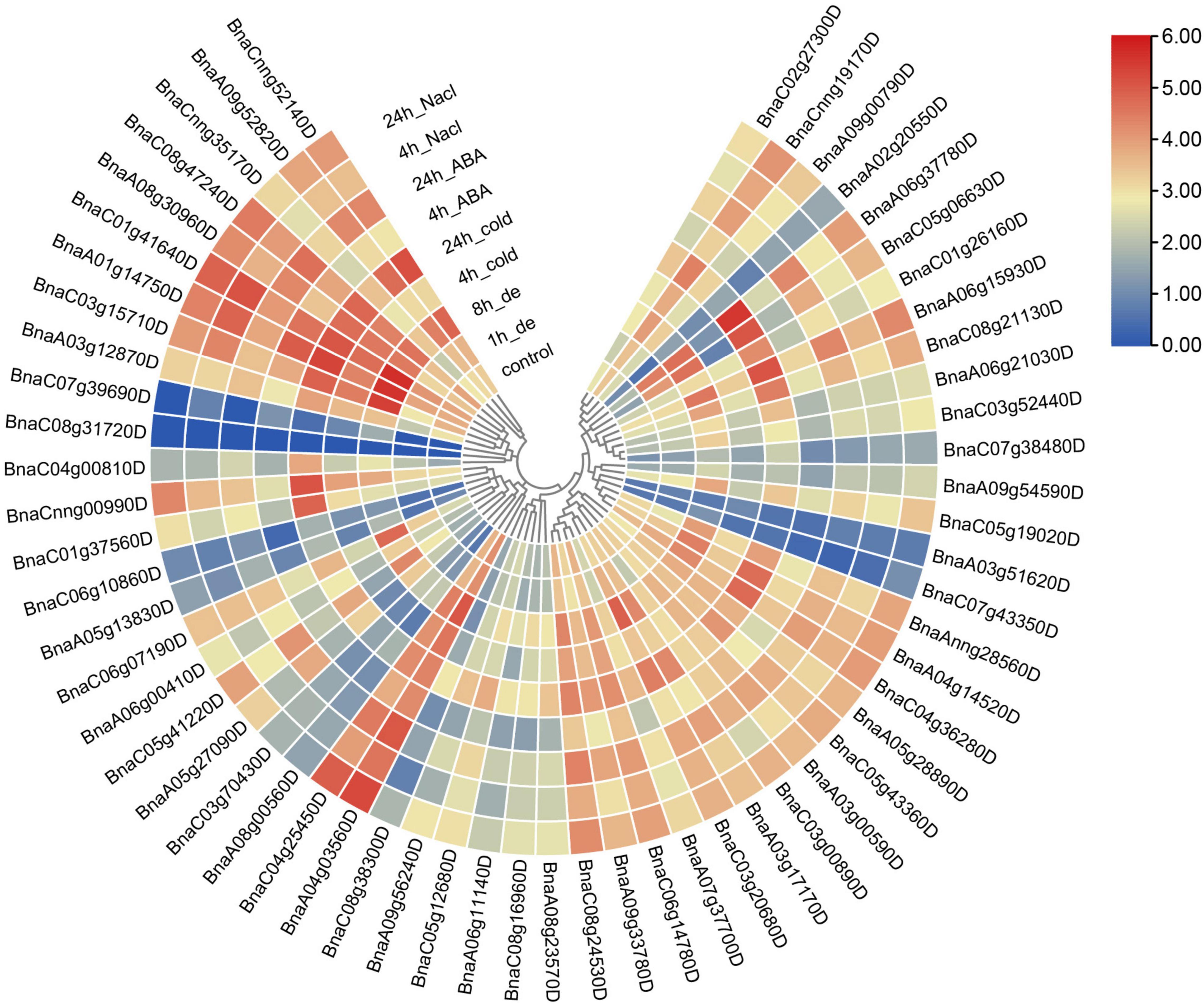

In spite of expression patterns in various tissues were investigated, the expression profiles of SR genes under different abiotic stresses were also analyzed. In this study, RNA-Seq data of samples from different abiotic treatments including cold, drought, salinity, ABA induction (Zhang et al., 2019) were utilized to analyze the expression pattern of SR genes in B. napus (Figure 8). Obviously, all the SR genes expressed higher after the treatment of abiotic stresses except those unexpressed or low-expressed genes. The expression of BnaC07g39690D was apparently up-regulated under dehydration stress. The expression of BnaC05g06630D dramatically increased under ABA induction as well as cold and salt stress, and it was noticed that elements response to these stresses (ABRE, LTR, and TC-rich repeats) were enriched in its promoter. All the SR genes expressed at a higher level in both subfamily RS2Z and subfamily SC, but in other subfamilies, different expression patterns were observed, especially for some paralogous gene pairs, like BnaC03g15710D/BnaC07g39690D, BnaC04g00810D/BnaC08g31720D, and BnaA02g20550D/ BnaA09g00790D, coincidentally, these gene pairs also showed different patterns in various tissues, which suggested they were differentiated into different directions, and the low-expressed genes like BnaC07g39690D, BnaC04g00810D and BnaA02g20550D may become pseudogenes.

Figure 8. Expression profiles of SR genes under abiotic stress conditions. Expression data were processed with log2 normalization. The color scale represented relative expression levels from low (blue color) to high (red color).

Alternative Splicing of SR Genes Is Widespread in Brassica napus

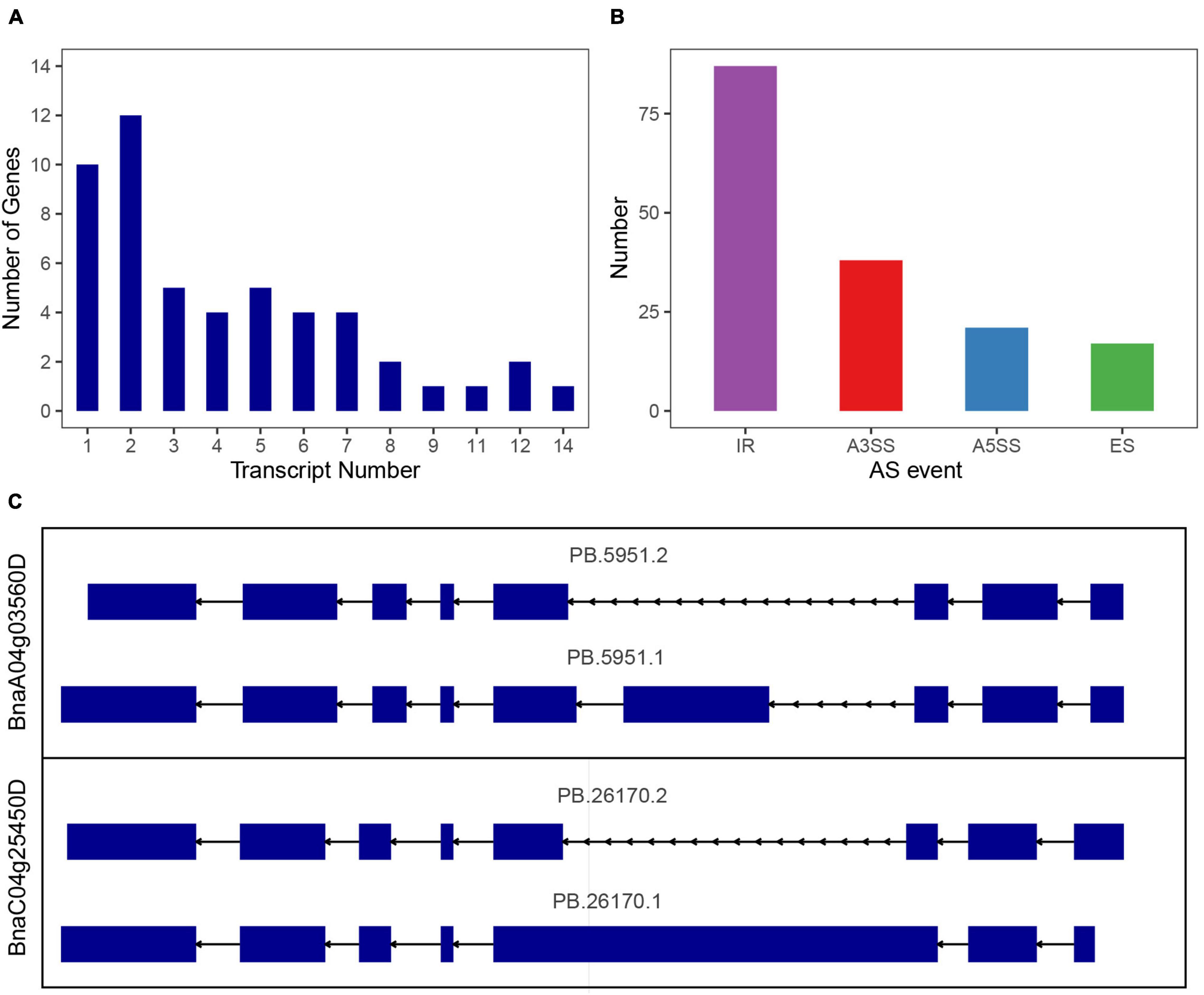

In Arabidopsis, maize and sorghum, most of the SR genes could be alternatively spliced, in order to investigate the alternative splicing (AS) of SR genes in B. napus, we used the dataset from Pacbio Iso-Seq technique, which could directly detect the existed mRNA and provide full-length transcripts. Based on Iso-Seq of B. napus cultivar “ZS11” (Yao et al., 2020), 51 of 59 SR genes were detected in this dataset, and 41 SR genes were alternative spliced, yielding 206 transcripts, an average of 5 transcripts for each gene (Figure 9A and Supplementary Table 6). As to each subfamily, SR genes in subfamily RS owned the most transcripts per gene (average 6.4 transcripts), whereas SR genes in subfamily SC contained the least transcripts, only 1.7 transcripts per gene, and the other subfamily RS, SR45, RS2Z, SCL, and RSZ contained 6.2, 4.3, 4.3, 2, and 1.8 transcripts, respectively. In the multi-exon SR genes, a total of 163 AS events were discovered, intron retention (IR) was the most one (87), followed by alternative 3′ splice site (A3SS, 38), alternative 5′ splice site (A5SS, 21) and exon skipping (ES, 17) (Figure 9B). Subfamily RS had 51 AS events (IR-29, A3SS-8, A5SS-9, ES-5), which was the most and consistent with its most transcripts. While the fewer transcripts in subfamily RSZ and SC contained fewer AS events. Most of the paralogous gene pairs displayed distinct splicing patterns, the first one was the transcripts number varied between paralogous gene pairs, like 2 transcripts of BnaA06g11140D vs. 4 transcripts of BnaC05g12680D, and 8 transcripts of BnaA03g17170D vs. 3 transcripts of BnaA07g37700D, the second one was the AS events varied between paralogous gene pairs, both BnaA04g03560D and BnaC04g25450D had 2 transcripts, but the identified AS events were different (Figure 9C). To verify the AS events, the detailed alignment information was displayed, and it showed that a small number of reads could span the splice sites (Supplementary Figure 2). Moreover, EST dataset was also used to blast against the alternative splicing transcripts, and the results revealed that the different AS events really existed (Supplementary Table 7). To find out the expression patterns of transcripts in various tissues, the expression levels of all the transcripts of SR genes were also counted (Supplementary Figure 3), and it showed that only a fraction of them expressed higher in these tissues, for paralogous gene pair BnaA04g03560D/BnaC04g25450D, the expression patterns of their transcripts were also different.

Figure 9. Splicing profiles of SR genes in B. napus based on Iso-Seq data. (A) The numbers of SR genes that produced one or more transcripts from Iso-Seq data. (B) Classification of AS events. IR, intron retention; A3SS, alternative 3′ splice site; A5SS, alternative 5′ splice site; ES, exon skipping. (C) Different splicing patterns of a paralogous gene pair.

Moreover, in the RNA-seq of abiotic stresses, the short reads were assemblied to predict the splicing profiles (Supplementary Figure 4), finally 124 transcripts were detected in 46 genes, and 61 AS events were identified. In this dataset, IR was not the most prevalent AS type, instead, A3SS was more prevalent. Five transcripts of BnaA06g37780D, BnaC05g06630D, and BnaA01g14750D were obviously induced by all four stresses, and the increment was obvious as the treatment time increased (Supplementary Figure 4), indicating that they were the responsible splicing factors responding to abiotic stress in B. napus.

Genetic Effects of SR Genes on Agronomic Traits of Brassica napus

To investigate the genetic variations of SR genes, SNPs were identified in a natural population containing 324 accessions collected from worldwide countries (Supplementary Table 8; Tang, 2019). Averagely, each SR gene contained 43 SNPs, lower than the whole genome level (94 SNPs in each gene). In consideration of genome size, we calculated the average SNP number of each kilobase (kb), all the SR genes were 17 SNPs/kb, while the whole genome level was 11 SNPs/kb. The SNP density of SR genes in the A subgenome (22 SNPs/kb) was slightly higher than the C subgenome (13 SNPs/kb). Moreover, the SNP density varied in different subfamilies, like subfamily SR45 had the most, with an average of 90 SNPs, followed by RSZ (41 SNPs) and SCL (39 SNPs), while SC had the fewest (only 29 SNPs). We also examined the genetic variations of paralogous gene pairs, there were 97 SNPs in BnaA09g00790D, but none in its paralogous gene BnaCnng19170D, while paralogous gene pairs BnaC04g00810D/BnaC08g31720D, had 49 and 5 SNPs, respectively. On the whole, most paralogous gene pairs exhibited unequal variations. Finally, SNP annotation showed that 658 SNPs occurred in exon regions and 194 SNPs in 39 SR genes resulted in missense mutations.

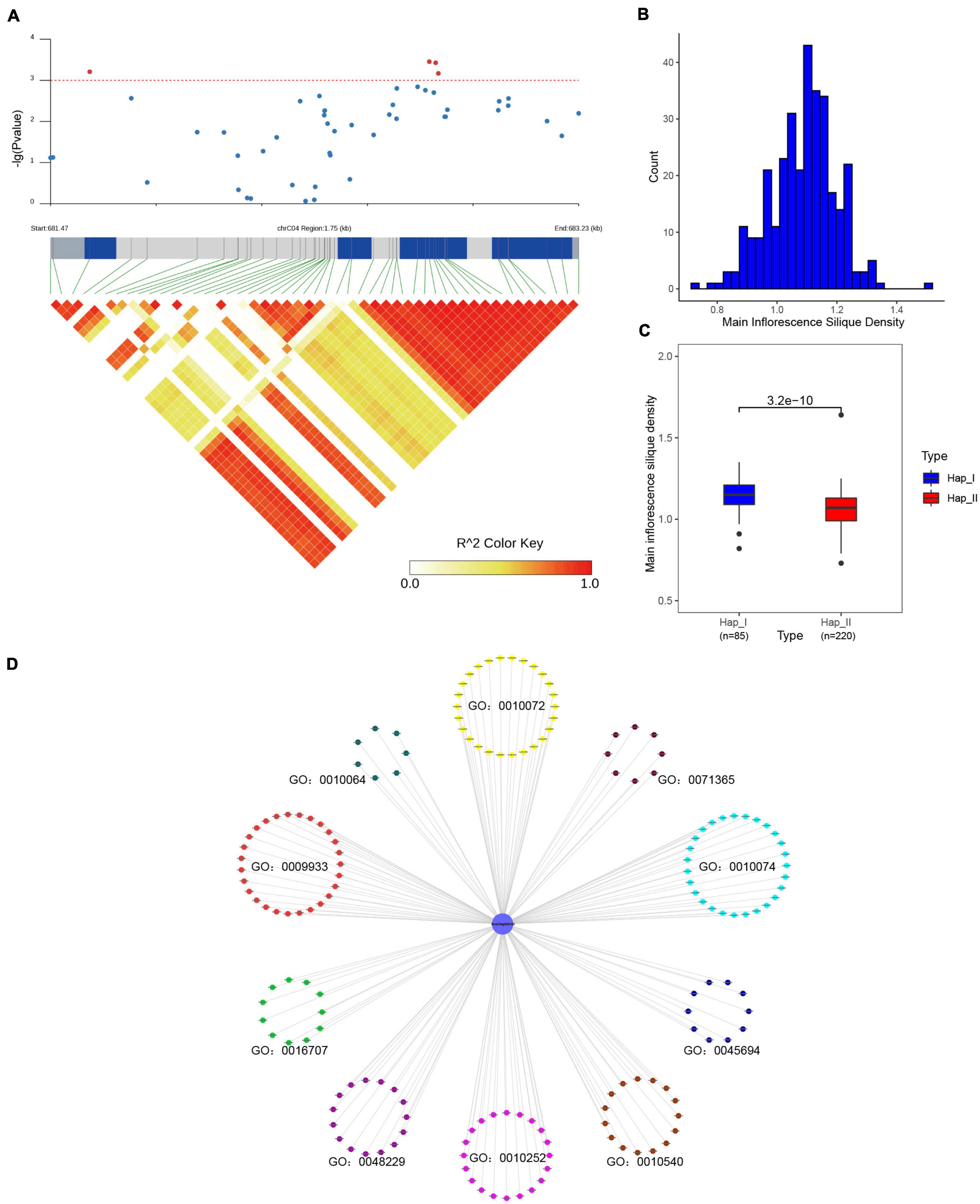

For SR genes were the fundamental regulators in pre-mRNA processing, it could affect various physiological processes, and finally result in diverse phenotype (Shepard and Hertel, 2009; Reddy and Shad Ali, 2011). In order to study the impact of SR genes on agronomic traits in B. napus, the association mapping analysis was conducted for 12 agronomic traits. In total, 49 SNPs (corresponding to 12 SR genes, Supplementary Table 8) located on A03, A05, A09, C03, C04, C05, C06, C07 and unanchored scaffolds were significantly associated with one or more agronomic traits (p < 0.001). BnaC04g00810D was significantly associated with main inflorescence silique density (Figures 10A,B), and the missense mutation in the coding sequence changed the arginine to histidine (305G > A). According to the genotype, two groups were divided and the main inflorescence silique density was significantly different based on the t-test (p < 3.2e–10) (Figure 10C). The interacted proteins of BnaC04g00810D were analyzed, they were not only enriched in mRNA splicing and spliceosome, but also enriched in the maintenance of meristem identity (GO:0010074), regulation of embryo sac egg cell differentiation (GO:0045694), meristem structural organization (GO:0009933), primary shoot apical meristem specification (GO:0010072), embryonic shoot morphogenesis (GO:0010064), gibberellin 3-beta-dioxygenase activity (GO:0016707), auxin homeostasis (GO:0010252), basipetal auxin transport (GO:0010540), cellular response to auxin stimulus (GO:0071365) (Figure 10D). As we knew, gibberellins (GAs) could promote stem elongation and floral development during bolting (Olszewski et al., 2002), auxin biosynthesis and transport played an important role in floral meristem initiation and inflorescence organization (Teo et al., 2014). All these processes were related with the regulation of endogenous hormone and the development of meristem/gametophyte, which could affect the silique density (Ren et al., 2018). The interacted proteins of BnaC04g00810D took part in these processes, like GA3OX1/2/4 in GO:0016707 were responsible for the last step of the biosynthetic of active GAs (Williams et al., 1998), ABCB19 in GO:0010540 mediated polar auxin transport (Wu et al., 2016), and GAF1 was involved in female gametophyte development (Zhu et al., 2016). Therefore, it was speculated that BnaC04g00810D also participated in the above processes through interacting with related proteins and might be an important candidate gene for silique density in B. napus. Moreover, BnaA03g12870D was significantly associated with flowering time and branch number, whereas BnaC03g20680D was significantly associated with the flowering period (Supplementary Figure 5), and the involved processes of their interacted proteins were also enriched in meristem structural organization, regulation of flower development and so on. Overall, the results suggested that sequence variations of SR genes could affect the development of B. napus and, ultimately influence the important agronomic traits.

Figure 10. Association mapping analysis of BnaC04g00810D in 324 core collections of B. napus germplasm. (A) BnaC04g00810D was significantly associated with main inflorescence silique density. (B) The distribution of main inflorescence silique density. (C) Comparison of main inflorescence silique density between the two haplotypes based on the most significantly associated SNP of BnaC04g00810D. (D) The enriched Gene Ontology terms of interacted proteins of BnaC04g00810D.

Discussion

Alternative splicing plays important role in the plant growth and development process, especially enhancing the adaptability of plants under stress conditions (Black, 2003; Palusa et al., 2007). Splicing factors are essential for the execution and regulation of splicing. Among them, SR proteins are the prominent factors involved in the assembly of spliceosomes, recognition and splicing of pre-mRNAs (Zahler et al., 1992). Recently, SR proteins in many plants have been studied at the genome-wide level to understand their evolution and function (Kalyna and Barta, 2004; Isshiki et al., 2006; Richardson et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2019, 2020b; Gu et al., 2020). In this study, 59 SR genes were identified and characterized in B. napus. A systematical analysis of SR genes including chromosomal locations, gene structures, conserved motifs, phylogenetic relationships, and protein-protein interactions was performed. Moreover, the expression patterns and AS types of SR genes in various tissues and stresses were analyzed. Variations in SR gene sequences and the association mapping analysis based on various agronomic traits were also performed to detect the relationship between SR genes and the final phenotype in B. napus.

After divergence from Arabidopsis lineage, the genus Brassica underwent a genome triplication event that occurred 13 million years ago, then interspecific hybridization between B. rapa and B. oleracea formed the allotetraploid B. napus (Allender and King, 2010). All the genes in B. napus expanded during its evolution and formation (Chalhoub et al., 2014). Many studies had shown that whole-genome duplication (WGD) and segmental duplications were the key factors to produce duplicated genes and result in the expansion of gene families (Ma et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2018; Zhu et al., 2020), as well as observed in SR genes in this study. Based on the effect of two recent duplication events, six homologs for each Arabidopsis gene were expected to present in B. napus, but we only found 59 SR genes in B. napus (about threefold of AtSRs), which indicated that gene loss happened (Albalat and Canestro, 2016). And the distribution of SR genes in the A and C subgenome implied the gene loss is asymmetrical, which is consistent with the genome level (Chalhoub et al., 2014). According to the Ka/Ks ratios of paralogous gene pairs, it is suggested that purifying selection played an important role in the evolution of SR genes in B. napus.

In plants, SR gene family had been investigated in Arabidopsis, rice, maize, wheat, tomato, cassava, and so on (Kalyna and Barta, 2004; Isshiki et al., 2006; Richardson et al., 2011; Yoon et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2019, 2020b; Gu et al., 2020; Rosenkranz et al., 2021). Most of the SR genes were divided into five to seven subfamilies according to the domain sequence or the whole sequence, likewise, 59 SR genes in B. napus were also classified into seven subfamilies. The proportion of plant-specific subfamily members in B. napus (31/59, 52.54%) was similar to that of other plants (Chen et al., 2019). Most genes in the same subfamily shared similar gene structures, conserved motifs, but the cis-acting regulatory elements in promoters emerged a big difference, which would affect the expression patterns (Zou et al., 2011; Oudelaar and Higgs, 2021). In the RNA-seq of various tissues, SR genes expressed obviously lower in leaf in comparison with bud, root, silique and callus, which was probably due to more complex splicing events in differentiated organs than mature organs, similarly, it had been proved that many SR genes expressed highly in early stages of fruit growth and development in tomato, which indicated a higher demand for factors to regulate pre-mRNA processing during cell expansion in immature green fruits (Rosenkranz et al., 2021). Various expression patterns of duplicated genes were also observed in this study, and it had been proved as one common way to lead to pseudogenization, neofunctionalization, or subfunctionalization in polyploids (Chaudhary et al., 2009). The lifestyle of plants is sessile, which is different from animals, environmental factors such as light, temperature, water or soil characteristics strongly influence their growth and development. As a result, plants have intelligently evolved various strategies for fleetly responding to changes (Meena et al., 2017). The diverse cis-acting regulatory elements in the promoter regions of different SR genes indicated their expression could be induced by hormones or abiotic stress. The different types, copy numbers and combinations of cis-acting regulatory elements predicted the diversity of SR genes expression patterns and flexibility in response to different stresses. Under environmental stress or hormone induction, the expression patterns of most SR genes changed. Expression of BnaA06g37780D and BnaC05g06630D increased with the treatment of cold, drought, salinity and ABA, and it had been verified that its orthologous gene AtSR30 was up-regulated by salinity stress (Tanabe et al., 2007).

Transcription is a flexible mechanism, which not only alters the gene expression but also could create diverse transcripts (Herbert and Rich, 1999). With the development of sequencing technology, it is possible to provide full-length transcripts by Iso-Seq directly (Abdel-Ghany et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2017), avoiding sequence assembly by short reads from RNA-seq. In the Iso-Seq data of the five tissues (Yao et al., 2020), 41 SR genes were alternatively spliced to produce 206 transcripts, which increased the transcriptome complexity greatly. If datasets from other various tissues and treatments were obtained, it was speculated that the amounts of SR transcripts were astounding in B. napus. AS not only regulated the gene expression, but also could cause neofunctionalization or subfunctionalization between paralogous genes (Zhang et al., 2009). Here we found diverse AS patterns that occurred in the paralogous gene pairs, this result supplied a clue for further functional study which would focus on the different transcripts of SR genes. Furthermore, SR genes generated a variety of transcripts by alternative splicing in response to abiotic stress. In Arabidopsis, it had been proved that the alternatively spliced transcripts of several SR genes were directly associated with plants’ ability to adapt to different environmental stresses (Palusa et al., 2007; Rauch et al., 2014). Similarly, 21 SR transcripts were detected under salt stress in cassava, which indicated these transcripts might participate in the biological process induced by salt (Gu et al., 2020). In this study, five transcripts from three SR genes obviously increased their expression after prolonged treatments of four different stresses. However, further research is required to determine the precise function and regulatory mechanisms of these SR transcripts in response to abiotic stress.

Sequence variations of SR genes were investigated in a natural population of B. napus (Tang, 2019), the SNP density in SR genes was higher than the average level of the genome, implying that abundant variations have accumulated in the evolution of SR gene family. The greater SNP prevalence of SR genes in the A subgenome was consistent with other gene families such as GATAs in a core collection of B. napus (Zhu et al., 2020). For genes in polyploids, after predicting function through their orthologs, to distinguish the one which performs function among several paralogous genes is another question. One way is to verify the function of paralogous genes one by one through traditional transgenic analysis, another way is with the aid of association mapping analysis. Typically, changes between paralogous gene pairs were distinct, leading to pseudogenization, neofunctionalization or subfunctionalization (Schiessl et al., 2017). For example, in contrast to Bn-CLG1C, a dominant point mutation in Bn-CLG1A led to cleistogamy in B. napus, which was regarded as a gain-of-function semi-dominant mutation (Lu et al., 2012). A single “C-T” mutation in the coding sequence of BnaA03.CHLH hindered chloroplast development, resulting in yellow-virescent leaf, while BnaC03.CHLH maintained the virescent color of the leaf (Zhao et al., 2020). In this study, 194 missense mutations could introduce various divergences of SR genes in B. napus. For paralogous gene pairs BnaC04g00810D/BnaC08g31720D, the expressions of BnaC04g00810D in tissues were higher than BnaC08g31720D, the missense mutation in the coding sequence of BnaC04g00810D changed the arginine to histidine, the association analysis and enriched processes of interacted proteins indicated that it was candidate gene for regulating silique density in B. napus. In previous studies, over-expression or transgenic analysis had proved that SR genes could affect the development and morphology in Arabidopsis (Kalyna et al., 2003; Ali et al., 2007), although none of the SR genes were studied by experimental analysis in B. napus, the association mapping analysis performed in this study could provide a useful clue for understanding the effect of SR genes on final phenotype and supply candidate genes for further improving agronomic traits in B. napus.

Conclusion

In this study, a comprehensive genome-wide identification and characterization of SR genes in B. napus were conducted. In total, 59 SR genes were identified and classified into seven subfamilies. Genes belonging to the same subfamily shared similar gene structures and motifs. Cis-acting regulatory elements in the promoters of SR genes and expression patterns in various tissues and environmental stresses revealed that they played important roles in development and stress responses. Transcriptome datasets from Pacbio/Illumina platforms showed that alternative splicing of SR genes was widespread in B. napus and the majority of paralogous gene pairs displayed different splicing patterns. Protein-protein interaction analysis showed that SR genes were involved in the whole lifecycle of mRNA, from synthesis to decay. Furthermore, genetic variations in SR genes were also investigated, and the association mapping results indicated that 12 SR genes were candidate genes for regulating specific agronomic traits. In summary, these findings provide elaborate information about SR genes in B. napus and may serve as a platform for further functional studies and genetic improvement of agronomic traits in B. napus.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author Contributions

MX, CT, and SL designed the research. MX, RZ, ZB, CZ, and LY performed the experiments. MX, RZ, FG, XC, JH, and YuL analyzed the data. MX, CT, and YaL wrote and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the current version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2018YFE0108000), the Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Program of Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CAAS-ASTIP-2013-OCRI), China Agriculture Research System of MOF and MARA (CARS-12), and the Young Top-notch Talent Cultivation Program of Hubei Province.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We thank Isobel Parkin and Gary Peng from Saskatoon Research Centre of Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada for meaningful discussion and constructive comments. We thank Zhixian Qiao of the Analysis and Testing Center at IHB for technical supports in RNA-seq analysis.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2022.829668/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Figure 1 | Amount of cis-acting regulatory elements in promoters of SR genes in B. napus. Elements numbers were processed with log2 normalization. The color scale represented amounts from low (blue color) to high (red color).

Supplementary Figure 2 | The alignment information of BnaA04g03560D and BnaC04g25450D.

Supplementary Figure 3 | Heatmap representation of transcripts of SR genes in different tissues. Expression data were processed with log2 normalization. The color scale represented relative expression levels from low (blue color) to high (red color).

Supplementary Figure 4 | Splicing profiles of SR genes in B. napus under abiotic stress condition. (A) Distribution of genes that produced one or more transcripts from RNA-Seq data. (B) Classification of AS events from RNA-Seq data. IR, intron retention; A3SS, alternative 3′ splice site; A5SS, alternative 5′ splice site; ES, exon skipping. (C) Five transcripts were obviously induced by all four stresses. Expression data were processed with log2 normalization. The color scale represented relative expression levels from low (blue color) to high (red color).

Supplementary Figure 5 | Association mapping analysis of SR genes in 324 core collections of B. napus germplasm. (A,B) BnaA03g12870D was significantly associated with primary flowering time. (C,D) BnaA03g12870D was significantly associated with branch number. (E,F) BnaC03g20680D was significantly associated with the flowering period.

Footnotes

- ^ http://brassicadb.cn/

- ^ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi

- ^ http://smart.embl.de/

- ^ https://web.expasy.org/protparam/

- ^ http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/

- ^ https://cran.r-project.org/

- ^ https://www.evolgenius.info/evolview/

- ^ https://www.string-db.org/

- ^ http://yanglab.hzau.edu.cn/BnTIR/eFP

References

Abdel-Ghany, S. E., Hamilton, M., Jacobi, J. L., Ngam, P., Devitt, N., Schilkey, F., et al. (2016). A survey of the sorghum transcriptome using single-molecule long reads. Nat. Commun. 7:11706. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11706

Albalat, R., and Canestro, C. (2016). Evolution by gene loss. Nat. Rev. Genet. 17, 379–391. doi: 10.1038/nrg.2016.39

Ali, G. S., Palusa, S. G., Golovkin, M., Prasad, J., Manley, J. L., and Reddy, A. S. N. (2007). Regulation of Plant Developmental Processes by a Novel Splicing Factor. PLoS One 2:e471. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000471

Allender, C., and King, G. (2010). Origins of the amphiploid species Brassica napus L. investigated by chloroplast and nuclear molecular markers. BMC Plant Biol. 10:54. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-10-54

Bailey, T. L., Johnson, J., Grant, C., and Noble, W. S. (2015). The MEME Suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, W39–W49. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv416

Black, D. L. (2003). Mechanisms of alternative pre-messenger RNA splicing. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 72, 291–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161720

Caceres, J. F., Misteli, T., Screaton, G. R., Spector, D. L., and Krainer, A. R. (1997). Role of the Modular Domains of SR Proteins in Subnuclear Localization and Alternative Splicing Specificity. J. Cell Biol. 138, 225–238. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.2.225

Chalhoub, B., Denoeud, F., Liu, S., Parkin, I. A., Tang, H., Wang, X., et al. (2014). Early allopolyploid evolution in the post-Neolithic Brassica napus oilseed genome. Science 345, 950–953. doi: 10.1126/science.1253435

Chaudhary, B., Flagel, L., Stupar, R. M., Udall, J. A., Verma, N., Springer, N. M., et al. (2009). Reciprocal Silencing, Transcriptional Bias and Functional Divergence of Homeologs in Polyploid Cotton (Gossypium). Genetics 182, 503–517. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.102608

Chen, C., Chen, H., Zhang, Y., Thomas, H., Frank, M., He, Y., et al. (2020a). TBtools: An Integrative Toolkit Developed for Interactive Analyses of Big Biological Data. Mol. Plant 13, 1194–1202. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2020.06.009

Chen, S., Li, J., Liu, Y., and Li, H. (2019). Genome-Wide Analysis of Serine/Arginine-Rich Protein Family in Wheat and Brachypodium distachyon. Plants 8:188. doi: 10.3390/plants8070188

Chen, T., Cui, P., Chen, H., Ali, S., Zhang, S., Xiong, L., et al. (2013). A KH-Domain RNA-Binding Protein Interacts with FIERY2/CTD Phosphatase-Like 1 and Splicing Factors and Is Important for Pre-mRNA Splicing in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet. 9:e1003875. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003875

Chen, X., Huang, S., Jiang, M., Chen, Y., XuHan, X., Zhang, Z., et al. (2020b). Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the SR gene family in longan (Dimocarpus longan Lour.). PLoS One 15:e0238032. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0238032

Cingolani, P., Platts, A., Wang, I. L., Coon, M., Nguyen, T., Wang, L., et al. (2012). A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly 6, 80–92. doi: 10.4161/fly.19695

Cruz, T. M., Carvalho, R. F., Richardson, D. N., and Duque, P. (2014). Abscisic acid (ABA) regulation of Arabidopsis SR protein gene expression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 15, 17541–17564. doi: 10.3390/ijms151017541

Dong, S. S., He, W. M., Ji, J. J., Zhang, C., and Yang, T. L. (2020). LDBlockShow: a fast and convenient tool for visualizing linkage disequilibrium and haplotype blocks based on variant call format files. Brief. Bioinformatics 22:bbaa227. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbaa227

Edgar, R. C. (2004). MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340

Gu, J., Ma, S., Zhang, Y., Wang, D., Cao, S., and Wang, Z. Y. (2020). Genome-Wide Identification of Cassava Serine/Arginine-Rich Proteins: Insights into Alternative Splicing of Pre-mRNAs and Response to Abiotic Stress. Plant Cell Physiol. 61, 178–191. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcz190

He, Z., Zhang, H., Gao, S., Lercher, M. J., Chen, W. H., and Hu, S. (2016). Evolview v2: an online visualization and management tool for customized and annotated phylogenetic trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W236–W241. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw370

Herbert, A., and Rich, A. (1999). RNA processing and the evolution of eukaryotes. Nat. Genet. 21, 265–269. doi: 10.1038/6780

Hu, B., Jin, J., Guo, A., Zhang, H., Luo, J., and Gao, G. (2015). GSDS 2.0: an upgraded gene feature visualization server. Bioinformatics 31, 1296–1297. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu817

Isshiki, M., Tsumoto, A., and Shimamoto, K. (2006). The Serine/Arginine-Rich Protein Family in Rice Plays Important Roles in Constitutive and Alternative Splicing of Pre-mRNA. Plant Cell 18, 146–158. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.037069

Kalyna, M., and Barta, A. (2004). A plethora of plant serine/arginine-rich proteins: redundancy or evolution of novel gene functions? Biochem. Soc. Trans. 32, 561–564. doi: 10.1042/BST0320561

Kalyna, M., Lopato, S., and Barta, A. (2003). Ectopic Expression of atRSZ33 Reveals Its Function in Splicing and Causes Pleiotropic Changes in Development. Mol. Biol. Cell 14, 3565–3577. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e03-02-0109

Kang, H. M., Sul, J. H., Service, S. K., Zaitlen, N. A., Kong, S. Y., Freimer, N. B., et al. (2010). Variance component model to account for sample structure in genome-wide association studies. Nat. Genet. 42, 348–354. doi: 10.1038/ng.548

Kim, D., Langmead, B., and Salzberg, S. L. (2015). HISAT: A fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods 12, 357–360. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3317

Krzywinski, M., Schein, J., Birol, I., Connors, J., Gascoyne, R., Horsman, D., et al. (2009). Circos: an information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 19, 1639–1645. doi: 10.1101/gr.092759.109

Larkin, M. (2007). Clustal W and Clustal X v. 2.0. Bioinformatics 23, 2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404

Letunic, I., Khedkar, S., and Bork, P. (2020). SMART: recent updates, new developments and status in 2020. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D458–D460. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa937

Li, Y., Guo, Q., Liu, P., Huang, J., Zhang, S., Yang, G., et al. (2021). Dual roles of the serine/arginine-rich splicing factor SR45a in promoting and interacting with nuclear cap-binding complex to modulate the salt-stress response in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 230, 641–655. doi: 10.1111/nph.17175

Livak, K. J., and Schmittgen, T. D. (2001). Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2 ΔΔ C T Method. Methods 25, 402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262

Lu, S., Wang, J., Chitsaz, F., Derbyshire, M., Geer, R., Gonzales, N., et al. (2020). CDD/SPARCLE: the conserved domain database in 2020. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, D265–D268. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz991

Lu, Y. H., Arnaud, D., Belcram, H., Falentin, C., Rouault, P., Piel, N., et al. (2012). A dominant point mutation in a RINGv E3 ubiquitin ligase homoeologous gene leads to cleistogamy in Brassica napus. Plant Cell 24, 4875–4891. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.104315

Ma, J. Q., Jian, H. J., Yang, B., Lu, K., Zhang, A. X., Liu, P., et al. (2017). Genome-wide analysis and expression profiling of the GRF gene family in oilseed rape (Brassica napus L.). Gene 620, 36–45. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2017.03.030

Magali, L. (2002). PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 325–327. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.325

McGlincy, N. J., and Smith, C. W. J. (2008). Alternative splicing resulting in nonsense-mediated mRNA decay: what is the meaning of nonsense? Trends Biochem. Sci. 33, 385–393. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.06.001

Meena, K. K., Sorty, A. M., Bitla, U. M., Choudhary, K., Gupta, P., Pareek, A., et al. (2017). Abiotic Stress Responses and Microbe-Mediated Mitigation in Plants: The Omics Strategies. Front. Plant Sci. 8:172. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00172

Melo, J. P., Kalyna, M., and Duque, P. (2020). Current Challenges in Studying Alternative Splicing in Plants: The Case of Physcomitrella patens SR Proteins. Front. Plant Sci. 11:286. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.00286

Mistry, J., Finn, R. D., Eddy, S. R., Bateman, A., and Punta, M. (2013). Challenges in homology search: HMMER3 and convergent evolution of coiled-coil regions. Nucleic Acids Res. 41:e121. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt263

Olszewski, N., Sun, T. P., and Gubler, F. (2002). Gibberellin signaling: biosynthesis, catabolism, and response pathways. Plant Cell 14, S61–S80. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010476

Oudelaar, A., and Higgs, D. (2021). The relationship between genome structure and function. Nat. Rev. Genet. 22, 154–168. doi: 10.1038/s41576-020-00303-x

Palusa, S. G., Ali, G. S., and Reddy, A. S. (2007). Alternative splicing of pre-mRNAs of Arabidopsis serine/arginine-rich proteins: regulation by hormones and stresses. Plant J. 49, 1091–1107. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.03020.x

Palusa, S. G., and Reddy, A. (2010). Extensive coupling of alternative splicing of pre-mRNAs of serine/arginine (SR) genes with nonsense-mediated decay. New Phytol. 185, 83–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.03065.x

Pertea, M., Pertea, G. M., Antonescu, C. M., Chang, T. C., Mendell, J. T., and Salzberg, S. L. (2015). StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 290–295. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3122

Rauch, H. B., Patrick, T. L., Klusman, K. M., Battistuzzi, F. U., Mei, W., Brendel, V. P., et al. (2014). Discovery and expression analysis of alternative splicing events conserved among plant SR proteins. Mol. Biol. Evol. 31, 605–613. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst238

Reddy, A. S., and Shad Ali, G. (2011). Plant serine/arginine-rich proteins: roles in precursor messenger RNA splicing, plant development, and stress responses. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2, 875–889. doi: 10.1002/wrna.98

Ren, Y., Cui, C., Wang, Q., Tang, Z., and Zhou, Q. (2018). Genome-wide association analysis of silique density on racemes and its component traits in Brassica napus L. Sci. Agricult. Sin. 54, 1020–1033. doi: 10.3864/j.issn.0578-1752.2018.06.002

Richardson, D. N., Rogers, M. F., Labadorf, A., Ben-Hur, A., Guo, H., Paterson, A. H., et al. (2011). Comparative analysis of serine/arginine-rich proteins across 27 eukaryotes: insights into sub-family classification and extent of alternative splicing. PLoS One 6:e24542. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024542

Rosenkranz, R. R. E., Bachiri, S., Vraggalas, S., Keller, M., Simm, S., Schleiff, E., et al. (2021). Identification and Regulation of Tomato Serine/Arginine-Rich Proteins Under High Temperatures. Front. Plant Sci. 12:645689. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.645689

Sapra, A. K., Ank, M. L., Grishina, I., Lorenz, M., and Neugebauer, K. M. (2009). SR Protein Family Members Display Diverse Activities in the Formation of Nascent and Mature mRNPs In Vivo. Mol. Cell 34, 179–190. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.02.031

Schiessl, S., Huettel, B., Kuehn, D., Reinhardt, R., and Snowdon, R. (2017). Post-polyploidisation morphotype diversification associates with gene copy number variation. Sci. Rep. 7:41845. doi: 10.1038/srep41845

Shannon, P., Markiel, A., Ozier, O., Baliga, N. S., Wang, J. T., Ramage, D., et al. (2003). Cytoscape: A Software Environment for Integrated Models of Biomolecular Interaction Networks. Genome Res. 13, 2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303

Shepard, P. J., and Hertel, K. J. (2009). The SR protein family. Genome Biol. 10:242. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-10-242

Sylvain, F., and Michael, S. (2007). ASTALAVISTA: dynamic and flexible analysis of alternative splicing events in custom gene datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W297–W299. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm311

Szklarczyk, D., Gable, A. L., Nastou, K. C., Lyon, D., Kirsch, R., Pyysalo, S., et al. (2021). The STRING database in 2021: customizable protein-protein networks, and functional characterization of user-uploaded gene/measurement sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D605–D612. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa1074

Tamura, K., Stecher, G., and Kumar, S. (2021). MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 3022–3027. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msab120

Tanabe, N., Yoshimura, K., Kimura, A., Yabuta, Y., and Shigeoka, S. (2007). Differential expression of alternatively spliced mRNAs of Arabidopsis SR protein homologs, atSR30 and atSR45a, in response to environmental stress. Plant Cell Physiol. 48, 1036–1049. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcm069

Tang, M. (2019). Population genome variations and subgenome asymmetry in Brassica napus L. Huazhong: Huazhong Agricultural University.

Teo, Z. W., Song, S., Wang, Y. Q., Liu, J., and Yu, H. (2014). New insights into the regulation of inflorescence architecture. Trends Plant Sci. 19, 158–165. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2013.11.001

Troncoso-Ponce, M. A., Kilaru, A., Cao, X., Durrett, T. P., Fan, J., Jensen, J. K., et al. (2011). Comparative deep transcriptional profiling of four developing oilseeds. Plant J. 68, 1014–1027. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04751.x

Wang, D., Zhang, Y., Zhang, Z., Zhu, J., and Yu, J. (2010). KaKs_Calculator 2.0: A Toolkit Incorporating Gamma-Series Methods and Sliding Window Strategies. Genom. Protem. Bioinf. 8, 77–80. doi: 10.1016/S1672-0229(10)60008-3

Wang, M., Wang, P., Liang, F., Ye, Z., Li, J., Shen, C., et al. (2017). A global survey of alternative splicing in allopolyploid cotton: landscape, complexity and regulation. New Phytol. 217, 163–178. doi: 10.1111/nph.14762

Wang, Y., Tang, H., Debarry, J. D., Tan, X., Li, J., Wang, X., et al. (2012). MCScanX: a toolkit for detection and evolutionary analysis of gene synteny and collinearity. Nucleic Acids Res. 40:e49. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1293

Will, C. L., and Luhrmann, R. (2010). Spliceosome Structure and Function. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 3:a003707. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003707

Williams, J., Phillips, A. L., Gaskin, P., and Hedden, P. (1998). Function and Substrate Specificity of the Gibberellin 3β-Hydroxylase Encoded by the Arabidopsis GA4 Gene. Plant Physiol. 117, 559–563. doi: 10.1104/pp.117.2.559

Wu, G., Carville, J. S., and Spalding, E. P. (2016). ABCB19-mediated polar auxin transport modulates Arabidopsis hypocotyl elongation and the endoreplication variant of the cell cycle. Plant J. 85, 209–218. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13095

Wu, Y., Ke, Y., Wen, J., Guo, P., Ran, F., Wang, M., et al. (2018). Evolution and expression analyses of the MADS-box gene family in Brassica napus. PLoS One 13:e0200762. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0200762

Yan, Q., Xia, X., Sun, Z., and Fang, Y. (2017). Depletion of Arabidopsis SC35 and SC35-like serine/arginine-rich proteins affects the transcription and splicing of a subset of genes. PLoS Genet. 13:e1006663. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006663

Yao, S., Liang, F., Gill, R. A., Huang, J., Cheng, X., Liu, Y., et al. (2020). A global survey of the transcriptome of allopolyploid Brassica napus based on single-molecule long-read isoform sequencing and Illumina-based RNA sequencing data. Plant J. 103, 843–857. doi: 10.1111/tpj.14754

Yoon, E. K., Krishnamurthy, P., Kim, J. A., Jeong, M.-J., and Lee, S. I. (2018). Genome-wide Characterization of Brassica rapa Genes Encoding Serine/arginine-rich Proteins: Expression and Alternative Splicing Events by Abiotic Stresses. J. Plant Biol. 61, 198–209. doi: 10.1007/s12374-017-0391-6

Yu, C. S., Chen, Y. C., Lu, C. H., and Hwang, J. K. (2006). Prediction of protein subcellular localization. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinform. 64, 643–651. doi: 10.1002/prot.21018

Yu, G., Wang, L. G., Han, Y., and He, Q. Y. (2012). clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS J. Integrat. Biol. 16, 284–287. doi: 10.1089/omi.2011.0118

Zahler, A. M., Lane, W. S., Stolk, J. A., and Roth, M. B. (1992). SR proteins: a conserved family of pre-mRNA splicing factors. Genes Dev. 6, 837–847. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.5.837

Zhang, W., Du, B., Di, L., and Qi, X. (2014). Splicing factor SR34b mutation reduces cadmium tolerance in Arabidopsis by regulating iron-regulated transporter 1 gene. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 455, 312–317. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.11.017

Zhang, Y., Ali, U., Zhang, G., Yu, L., Fang, S., Iqbal, S., et al. (2019). Transcriptome analysis reveals genes commonly responding to multiple abiotic stresses in rapeseed. Mol. Breed. 39:158. doi: 10.1007/s11032-019-1052-x

Zhang, Z., Li, Z., Ping, W., Yang, L., Chen, X., and Hu, L. (2009). Divergence of exonic splicing elements after gene duplication and the impact on gene structures. Genome Biol. 10:R120. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-11-r120

Zhang, Z., Xiao, J., Wu, J., Zhang, H., Liu, G., Wang, X., et al. (2012). ParaAT: A parallel tool for constructing multiple protein-coding DNA alignments. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 419, 779–781. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.02.101

Zhao, C., Liu, L., Safdar, L. B., Xie, M., Xiaohui Cheng, Liu, Y., et al. (2020). Characterization and Fine Mapping of a Yellow-Virescent Gene Regulating Chlorophyll Biosynthesis and Early Stage Chloroplast Development in Brassica napus. G3 Genes Genom. Genet. 10, 3201–3211. doi: 10.1534/g3.120.401460

Zhu, D. Z., Zhao, X. F., Liu, C. Z., Ma, F. F., Wang, F., Gao, X. Q., et al. (2016). Interaction between RNA helicase ROOT INITIATION DEFECTIVE 1 and GAMETOPHYTIC FACTOR 1 is involved in female gametophyte development in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 67, 5757–5768. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw341

Zhu, W., Guo, Y., Chen, Y., Wu, D., and Jiang, L. (2020). Genome-wide identification, phylogenetic and expression pattern analysis of GATA family genes in Brassica napus. BMC Plant Biol. 20:543. doi: 10.1186/s12870-020-02752-2

Keywords: serine/arginine-rich gene family, Brassica napus, expression pattern, alternative splicing, association mapping analysis, agronomic traits

Citation: Xie M, Zuo R, Bai Z, Yang L, Zhao C, Gao F, Cheng X, Huang J, Liu Y, Li Y, Tong C and Liu S (2022) Genome-Wide Characterization of Serine/Arginine-Rich Gene Family and Its Genetic Effects on Agronomic Traits of Brassica napus. Front. Plant Sci. 13:829668. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.829668

Received: 06 December 2021; Accepted: 10 January 2022;

Published: 16 February 2022.

Edited by:

Hai Du, Southwest University, ChinaReviewed by:

Kun Lu, Southwest University, ChinaXiaoming Song, North China University of Science and Technology, China

Haifeng Li, Northwest A&F University, China

Copyright © 2022 Xie, Zuo, Bai, Yang, Zhao, Gao, Cheng, Huang, Liu, Li, Tong and Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Chaobo Tong, dG9uZ2NoYW9ib0AxMjYuY29t; Shengyi Liu, bGl1c3lAb2lsY3JvcHMuY24=

Meili Xie

Meili Xie Rong Zuo

Rong Zuo Zetao Bai

Zetao Bai Chuanji Zhao

Chuanji Zhao Junyan Huang

Junyan Huang Chaobo Tong

Chaobo Tong Shengyi Liu

Shengyi Liu