95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Plant Sci. , 02 December 2022

Sec. Plant Metabolism and Chemodiversity

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.1090967

This article is part of the Research Topic Rising Stars in Plant Metabolism and Chemodiversity 2022 - Phenylpropanoid Metabolism and Regulation View all 5 articles

Bowei Chen1,2

Bowei Chen1,2 Yile Guo1,2

Yile Guo1,2 Xu Zhang1,2

Xu Zhang1,2 Lishan Wang1,2

Lishan Wang1,2 Lesheng Cao1,2

Lesheng Cao1,2 Tianxu Zhang1,2

Tianxu Zhang1,2 Zihui Zhang1,2

Zihui Zhang1,2 Wei Zhou1,2

Wei Zhou1,2 Linan Xie1,2

Linan Xie1,2 Jiang Wang1,2*

Jiang Wang1,2* Shanwen Sun1,2*

Shanwen Sun1,2* Chuanping Yang1*

Chuanping Yang1* Qingzhu Zhang1,2*

Qingzhu Zhang1,2*Lignin is one of the most important secondary metabolites and essential to the formation of cell walls. Changes in lignin biosynthesis have been reported to be associated with environmental variations and can influence plant fitness and their adaptation to abiotic stresses. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying this association remain unclear. In this study, we evaluated the relations between the lignin biosynthesis and environmental factors and explored the role of epigenetic modification (DNA methylation) in contributing to these relations if any in natural birch. Significantly negative correlations were observed between the lignin content and temperature ranges. Analyzing the transcriptomes of birches in two habitats with different temperature ranges showed that the expressions of genes and transcription factors (TFs) involving lignin biosynthesis were significantly reduced at higher temperature ranges. Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing revealed that promoter DNA methylation of two NAC-domain TFs, BpNST1/2 and BpSND1, may be involved in the inhibition of these gene expressions, and thereby reduced the content of lignin. Based on these results we proposed a DNA methylation-mediated lignin biosynthesis model which responds to environmental factors. Overall, this study suggests the possibility of environmental signals to induce epigenetic variations that result in changes in lignin content, which can aid to develop resilient plants to combat ongoing climate changes or to manipulate secondary metabolite biosynthesis for agricultural, medicinal, or industrial values.

Climate change includes the instantaneous and rapid alterations of numerous important environmental parameters that regulate the dynamics of the ecosystem, such as temperature and precipitation. These rapid changes may have direct and indirect effects on plants via alterations in plant secondary metabolism (Christensen and Christensen, 2007; Bita and Gerats, 2013; Rienth et al., 2021). Lignin is one of the most important secondary metabolites and is essential to the formation of cell walls. Changes in lignin biosynthesis can influence plant fitness and their adaptation to environment (Liu et al., 2018). For example, a lignin-deficient mutant of Arabidopsis was found to have a significantly lower seed germination rate compared to the wild type, hypothetically due to an increase of sensitivity to unfavorable environments (Liang et al., 2006). Moreover, previous studies have shown that the lignin biosynthesis is highly responsive to environmental changes (Moura et al., 2010; Cesarino, 2019; Gu et al., 2020). Under drought and salt stresses, increased lignin can reduce plant cell wall water penetration and transpiration, which helps to maintain cell osmotic balance and protect membrane integrity (Monties and Fukushima, 2001; Chun et al., 2019). When plants are exposed to an excess of light, an increased level of lignin content is observed, which may prevent the accumulation of hydrogen peroxide and thus protect the cellular damage from the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Chen et al., 2002). Similarly, increased lignin content can reduce damage from ultraviolet (UV)-B radiation in plants (Rozema et al., 1997). In addition, changes in lignin content are also found to be related to cold acclimation (Wei et al., 2006; Zeng et al., 2016). One possible reason is that the altered ratio of syringyl (S) to guaiacyl (G) subunits affects cell wall rigidity and water permeability, thus increasing plant resistance to cold temperatures (Zhao et al., 2013). Overall, these previous findings indicate that lignin biosynthesis is tightly associated with environmental conditions. Deciphering the molecular basis underlying this association is thus crucial to understanding plants adaptation and evolution and to promoting plants conservation and breeding.

DNA methylation (5-methylcytosine) is an important regulatory mechanism by which plants respond to environmental fluctuations (McCaw et al., 2020; Sun et al., 2022). In plants, DNA methylation occurs in three sequence contexts: CG, CHG, and CHH, where H is any nucleotide except G. Maintenance DNA methylation in symmetrical CG and CHG contexts is executed by DNA METHYLTRANSFERASE 1 (MET1) and CHROMOMETHYLASE 3 (CMT3), respectively. Asymmetric CHH methylation is maintained by CHROMOMETHYLASE 2 (CMT2) and the 24nt-siRNA involved RNA-directed DNA methylation (RdDM) pathway (Law and Jacobsen, 2010; Zemach et al., 2013; Stroud et al., 2014). Changes in DNA methylation in response to altered environmental conditions may facilitate plant adaptation via their effects on gene expressions. For example, in B. gymnorhiza, genome-wide CHH hypermethylation induced by increased environmental salinity can enhance several salt-responsive genes expression, such as Bg70 and BURP Domain Containing protein 3 (BgBDC3) (Miryeganeh et al., 2022). In maize, genome-wide demethylation enables the activation of stress-responsive genes under cold stresses (Steward et al., 2002). In natural populations, genome-wide CHH methylation variations are associated with the changes of temperature seasonality in Arabidopsis accessions (Shen et al., 2014). CG methylation variations, which affects dehydration-responsive genes in oak, are found to be significantly associated with the mean maximum temperature of the warmest month (Gugger et al., 2016). Together, these results provide evidence that epigenetic variation can be an important molecular mechanism that influences plant adaptations to the changing climates.

Since DNA methylation and lignin production can both be adaptive responses to external environments, we hypothesized that DNA methylation is likely to respond to environmental fluctuations by participating in lignin regulation. This was based on two lines of evidence. First, previous studies have shown that the variations of DNA methylation are, at the same time, associated with the biosynthesis of secondary metabolism and with the environmental gradients. For example, in birch, variations in methylation of the bHLH9 promoter are found to affect the biosynthesis of betulin and be significantly associated with local temperatures and precipitations (Wang et al., 2021). In wheat, DNA methylation of genes involved in carbon metabolism or fatty acid metabolism contributes to male spikelet sterility in a temperature-sensitive genic male sterile (TGMS) line, BS366, in response to cold (Liu et al., 2021). Further, DNA methylation levels involved in metabolic processes are significantly associated with high temperatures in rice (Li et al., 2022). These results provide the evidence that the regulatory role of DNA methylation in plant adaptation can be mediated by its effects on secondary metabolisms.

Second, lignin biosynthesis is a very complex network, involving many enzymes and transcription factors (TFs). Lignin monomer synthesis is mainly composed of phenylpropane metabolic pathways and downstream synthases (Xie et al., 2018). The classic phenylpropane metabolic pathways are primarily composed of phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL), cinnamate-4-hydroxylase (C4H), and 4-coumarate: CoA ligase (4CL), contributing to the conversion of phenylalanine into p-coumaroyl-CoA (Fraser and Chapple, 2011; Wang et al., 2018). In addition to these three enzymes, some other phenylpropanoid biosynthetic enzymes are responsible for the sequential conversion of intermediate/downstream products of the phenylpropane metabolic pathway into lignin monomers (Raes et al., 2003; Yoon et al., 2015). The polymerization of lignin monomers is then carried out by peroxidase (POD) and laccase (LAC) (Liu et al., 2011; Alejandro et al., 2012). Moreover, the transcriptional regulation of lignin biosynthesis genes is mainly well-known for the first-layer NAC-domain TFs (Kubo et al., 2005; Zhong et al., 2007; Fang et al., 2020), and the second-layer MYB-domain TFs (Ko et al., 2014; Nakano et al., 2015; Xiao et al., 2021). This complexity can offer more chances in which DNA methylation could be involved. As an example, we recently found that a transcription factor, CmMYB6, that regulates another downstream branch of phenylpropane metabolic pathways, can have methylation variations in the promoter which regulates anthocyanins biosynthesis (Tang et al., 2022). However, whether DNA methylation is involved in lignin biosynthesis and this relation, if exist, would contribute to environmental adaptation in natural conditions are still unclear.

In this study, to investigate the relation of DNA methylation with lignin and its role in plant adaptation, Chinese birch (Betula platyphylla Suk.), which is widely distributed in the northeast China, was selected as the target species (Geng et al., 2022). Lignin content, methylome and transcriptome profiles of genes involved in the lignin biosynthesis pathway were assessed to uncover a possible molecular regulatory mechanism and to test their relations with climatic factors. We found that the lignin content of natural birch was significantly negatively correlated with local temperature ranges. Nearly all critical lignin biosynthesis genes were expressed at significantly higher levels in birch trees grown at low temperature ranges than at high temperature ranges. This differential expression was likely regulated by two master switches of lignin activators, BpNST1/2 and BpSND1, whose expressions were likely regulated by differential methylation of the promoters between birches grown in different temperature ranges. In summary, our results support the hypothesis that DNA methylation can be involved in responses to climate changes via its regulation on plant secondary metabolites and can further provide useful information about how to manage the white birch to efficiently utilize lignin from natural birch sources.

To ensure that the sampling covered the entire distribution area of birch (Betula platyphylla) in the northeast China (119.91°-133.75°E, 41.32°-53.15°N), four representative regions with distinct climates were selected: Changbai Mountain, Xiaoxing Anling, Daxing Anling and Sanjiang Plain. The landscape was characterized by plains and mountains with elevations ranging from 55.2 to 995.0 m. The Annual Mean Temperature (bio1) varied between -4.71°C and 5.15°C, and the Temperature Annual Range (bio7) differed from 43.34°C to 61.56°C. Precipitation primarily occurred during the crop-growing season (from April to August), and the Annual Precipitation (bio12) ranges from 420 to 935 mm.

In the summer of 2019, cores were collected from 60 sites with naturally growing 20-30 years old birch trees (Supplementary Figure S1 and Supplementary Table S1). Among them, 17 sampling sites were distributed in Changbai Mountain, 12 were distributed in Xiaoxing Anling, 27 were distributed in Daxing Anling, and 4 were distributed in Sanjiang Plain. We sampled one individual from each sampling site and used the abbreviated name of sampling sites to indicate each sample. For example, “Sl”, “Fhs”, “Ame” and “Alh” were used to refer to the sample from “Shulan”, “Fenghuangshan”, “Amuer”, and “Alihe” sampling sites, respectively. For each individual, cores were collected at 15-20 cm in diameter at breast height (DBH, 1.3 m above the ground) (Guo et al., 2017). Collected fresh leaves and cores were immediately stored in liquid nitrogen and dry sealed tubes, respectively, for subsequent experiments.

Collected cores were first fixed in wooden troughs and left to dry completely at room temperature (20°C) for at least 7 days. Subsequently, the 400-grit and 600-grit sandpaper were used to perform rough grinding and fine grinding in turn until the surface of the cores was smooth and the boundaries of tree ring were exposed. Finally, the treated cores were calibrated under a microscope to determine the age of each birch.

To determine the lignin content in each birch individual, the Soxhlet extraction method was adopted in this study (Arni, 2018; Saha et al., 2019). The first step was to extract the wood powder. Dried cores were ground with a 40-grit sandpaper, and the resulting wood powder was stored in a Soxhlet extractor. The Soxhlet extractor was then connected to an extraction device containing 300 ml of extraction solution (ethanol: benzene = 1:2) for 6 hours and transferred to a fume hood to air-dry for at least 48 hours.

The second step was to measure the weight of dry wood powder. Extracted wood powder (0.0500~0.0505 g, recording the weight as W1 (g)) was placed in an oven at 105°C for at least 8 hours. After that, the dried wood powder was transferred to a vacuum dryer and vacuumed for about 10 min, then transferred to dry conditions and naturally cooled for 1 hour. The final weight was recorded as W2 (g). Moisture content and dry wood powder were calculated as follows:

The third step was to measure the content of lignin. Extracted wood powder (0.0500~0.0505 g) was first acid-hydrolyzed by mixing with 1.5 ml of 72% H2SO4 solution in a 10-ml glass tube for 90 min. Each sample was transferred into a 100-ml glass bottle, supplemented with ultrapure water to 36 ml, then sealed and autoclaved at 121°C for 90 min. After cooled to room temperature and suction filtered, 10 ml of filtrate was measured at 205 nm using a UV spectrophotometer (W3). The remaining solid particles in the bottles were washed with 200 ml of ultrapure water and stored in a crucible. After drying in an oven at 105°C for 8 h, the weight was recorded as W4 (g). Three independent replicates were performed for each sample. Lignin content was calculated as follows:

The 19 climatic variables (bio1 ~ bio19) used in this study were extracted from the WorldClim 2.0 database using the R package “Raster” (Fick and Hijmans, 2017) based on the recorded longitude and latitude information of the sampling sites (Supplementary Tables S1, S2). Specifically, bio5, bio8 and bio10 are climatic variables related to summer temperatures, bio6, bio9 and bio11 are related to winter temperatures, bio2, bio3, bio4 and bio7 are related to temperature ranges, bio13, bio16 and bio18 are related to summer precipitations, and bio14, bio17 and bio19 are related to winter precipitations.

15 lignin biosynthesis synthases in birch, namely BpPAL1, BpPAL3, BpC4H2, BpC4H3, Bp4CL2, BpHCT1, BpC3H1, BpCCoAOMT2, BpCCR1, BpCCR4, BpF5H2, BpCOMT9, BpCOMT17, BpCAD9 and BpCAD12, were acquired from Chen et al. (2020). 18 TFs involved in regulation of lignin biosynthesis in birch, namely BpNST1/2, BpSND1, BpVND6/7, BpMYB46/BpMYB83, BpMYB61, BpMYB75, BpMYB103, BpMYB3/4/7/32, BpMYB20/43/85 and BpMYB15/58/63, were identified by BLAST alignment and a phylogenetic tree with known lignin-regulated TFs in Arabidopsis (Xiao et al., 2021).

We collected the fresh mature leaves of Sl (127.12˚E, 44.20˚N, 18.5˚C), Fhs (127.98˚E, 44.22˚N, 19.0˚C), Ame (123.34˚E, 52.86˚N, 15.5˚C), and Alh (123.69˚E, 50.63˚N, 17.0˚C) in June of 2019. The collected leaves were immediately stored in liquid nitrogen in sampling sites, and used to assess the methylome and transcriptome profiles of genes involved in the lignin biosynthesis pathway. Previous studies have shown that lignin content and the methylation as well as expression levels of related biosynthetic and regulatory genes in different tissues may be the same trend (Barber and Mitchell, 1997; Davey et al., 2004; Akgul et al., 2007; Zagoskina et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2021). We, therefore, used leaves for both methylome and transcriptome experiments instead of stems due to technical obstacles.

Genomic DNA was extracted from fresh leaves using the CTAB method (Pan et al., 2006). DNA was recovered from a sizing gel to select for fragment size, and PCR amplification was performed to construct the MethylC-seq library, and finally, an Illumina Hiseq 2000 sequencer was used for PE150 sequencing. Raw HiSeq data was filtered using Fastp, and the clean reads were mapped to the reference genome (Betula pendula) using BSMAP software with default parameters (Li and Li, 2009; Salojarvi et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2018). Methylated cytosines were called using a Python script in BSMAP. A WIG file was generated using a Perl script, and was used for visualization of differentially methylated regions (DMRs). Similar workflows were followed to construct the DNA-seq library and PE150 sequencing. Clean reads were mapped to the reference genome using the Burrows-Wheeler-Alignment Tool (BWA) (Li and Durbin, 2009). The Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK v.4.0) was used to analyze the SNPs and Insertion/Deletion mutations (InDels) throughout the birch genome (Poplin et al., 2018).

RNA was isolated from the fresh leaves (without petioles) of the same four individuals using the OminiPlant RNA Kit (DNase I), and RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) was performed on the Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform. Each sample was performed with three independent technical replicates. Raw transcriptome data was filtered using Fastp and the clean reads were mapped to the B. pendula reference genome using the HISAT2 aligner with default parameters (Kim et al., 2019). Expression of each gene was calculated in transcripts per million (TPM) by converting the sorted BAM alignment files with StringTie software (Pertea et al., 2015). Small RNA (sRNA) data was also aligned to the reference genome using BOWTIE software with parameters that allow up to one base mismatch. sRNA abundance for each region was calculated in reads per million (RPM) (Langmead et al., 2009). Summary statistics for the MethylC-seq, DNA-seq, RNA-seq and sRNA-seq libraries can be found in Supplementary Tables S3, S4.

The relative expression levels of randomly-selected genes involved in lignin biosynthesis were verified via qRT-PCR using Sl, Fhs, Ame, and Alh samples. After RNA was extracted from leaves as described above, cDNA was synthesized through reverse transcription reactions. The total reaction mixture was 10 μL per sample and contained 1 μL Primer Script RT enzyme, 1 μL RT Primer Mix, 4 μL 5× Primer Script buffer, and 4 μL RNase-free ddH2O. The reaction conditions were set as follows: 15 min at 37°C, 5 s at 85°C, and 10 min at 0°C. The total reaction mixture for qRT-PCR was 15 μL, which contained 6.3 μL of 10× diluted cDNA template, 7.5 μL SYBR Green Supermix (catalog number: RK02001), 0.6 μL forward primer, and 0.6 μL reverse primer. Reactions were carried out in technical triplicate on the Applied Biosystems ABI7500 real-time PCR machine. The transcript abundance for each gene was calculated using the 2-ΔΔCt method (Skern et al., 2005) with tubulin (Bpev01.c0597.g0026) used as the internal control for expression normalization. Primers used for qRT-PCR are shown in Supplementary Table S5.

Lignin content for each birch was visualized in the study area of the northeast China using the R package ‘maptools’ (South, 2011). Spearman’s correlation was used to assess the relation between lignin content and tree age. To eliminate the potential interference of age factors, a partial correlation analysis was conducted to evaluate the relations between lignin content and climatic variables (Sadeghi and Marchetti, 2012). Correlations were considered significant at p ≤ 0.05. Differences in lignin content and gene expression between the two groups of birches were assessed with Student’s t-test, and DMRs that surrounded the relevant genes were analyzed with a hypergeometric test (Zhang et al., 2016). Significant differences were called at p ≤ 0.05.

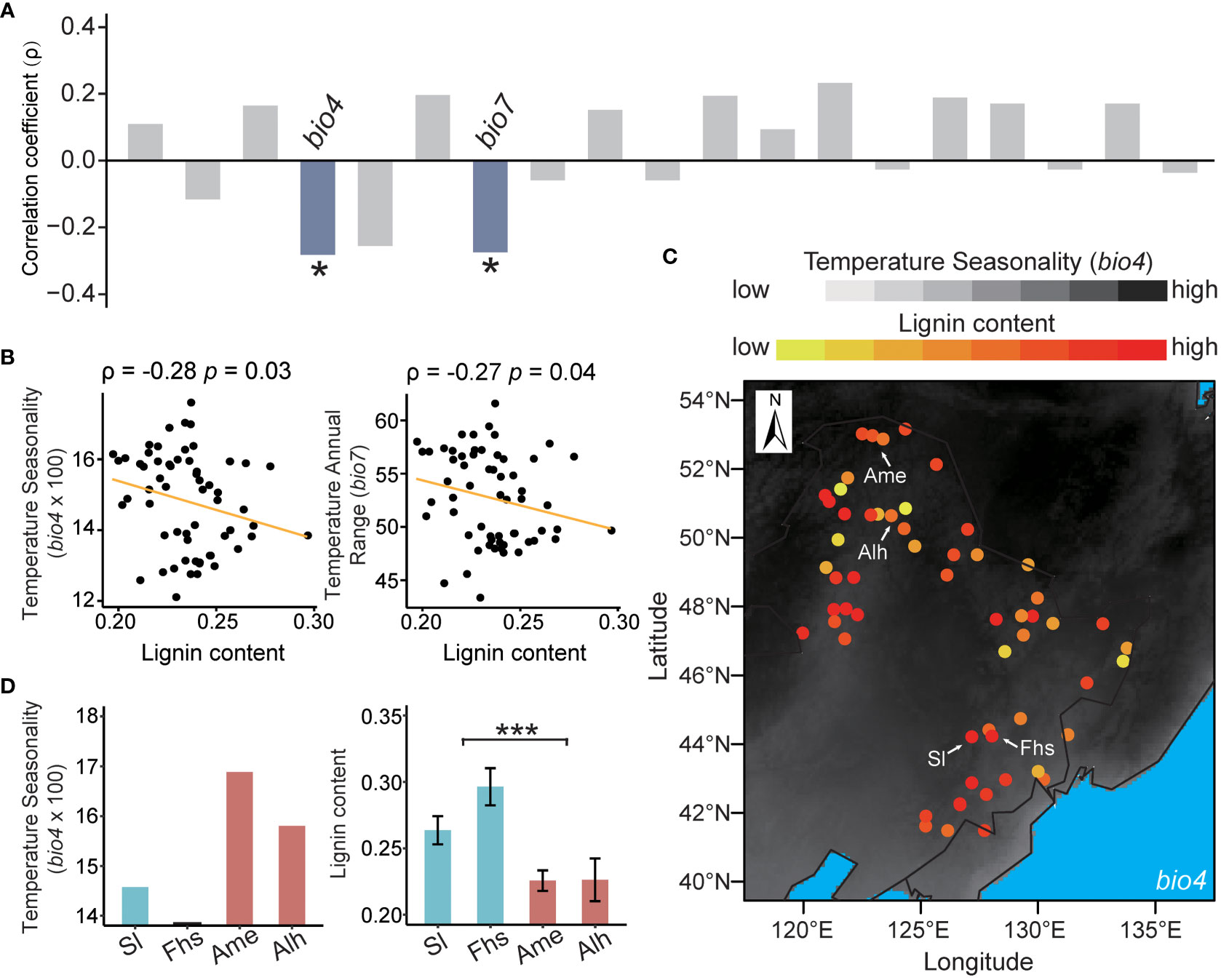

The lignin content of 60 natural birch individuals with a diverse geographic distribution ranged from 0.2 to 0.3 (Supplementary Figure S1 and Supplementary Table S1). Spearman’s correlation analysis showed that the lignin content was independent of tree age (ρ = 0.22, p = 0.1) (Supplementary Figure S2). To control for the potential influence of tree age, partial correlations were used to analyze the relationships between the lignin content and 19 climatic variables. We found that the lignin content of natural birch was significantly negatively correlated with the local temperature ranges (Figure 1A and Supplementary Table S6). Specifically, the correlation coefficient between lignin content and Temperature Seasonality (bio4) was -0.28 (p = 0.03), and the correlation coefficient for Temperature Annual Range (bio7) was -0.27 (p = 0.04) (Figure 1B). These results suggested that temperature ranges may have a negative effect on the lignin content in native birch.

Figure 1 Correlations between lignin content and climatic variables. (A) Partial correlations between lignin content and 19 climatic variables. The correlation coefficients (ρ) in blue bar mean the lignin content is significantly negatively correlated with the indicated climatic variables, and those in grey mean the lignin content is not significantly correlated with the indicated climatic variables. (B) Distribution of lignin content with Temperature Seasonality (bio4) and Temperature Annual Range (bio7). The segmental line in orange represents the partial correlation fit of lignin to an indicated climatic variable. (C) Visualization of the relationship between lignin content and bio4 in the northeast China. The color of the point in background reflects the value of bio4, with darker for a higher value and lighter for a lower value. The color of sampling sites reflects the content of lignin, with a redder color for a higher content and vice versa. The symbols “Sl”, “Fhs”, “Ame”, and “Alh” referred to the sample from different sampling sites, namely “Shulan”, “Fenghuangshan”, “Amuer”, and “Alihe”. (D) Comparisons of Temperature Seasonality (bio4) and the lignin content in Sl, Fhs, Ame, and Alh. The p ≤ 0.05 is marked as ‘*’, and p ≤ 0.001 is marked as ‘***’.

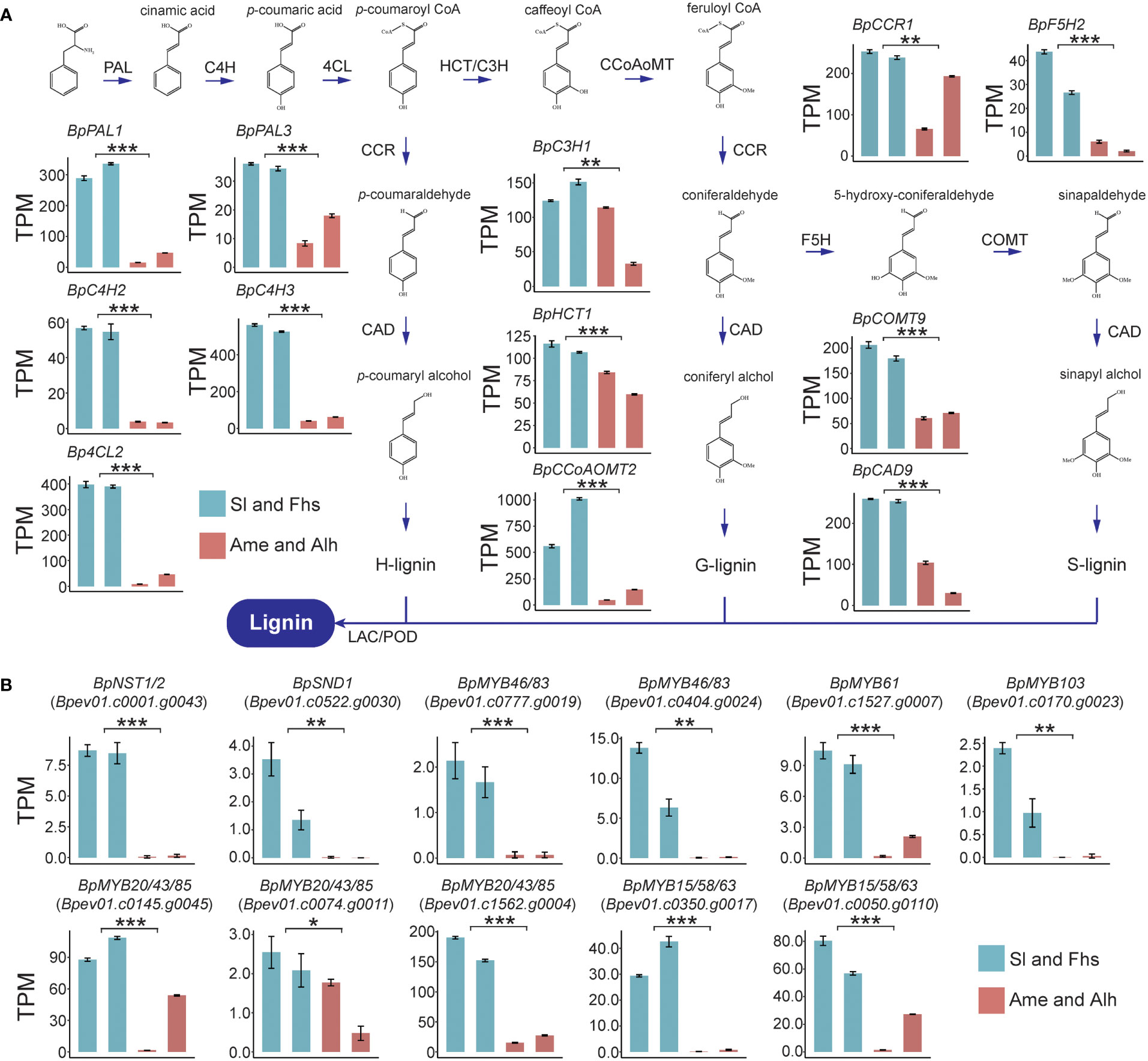

To illustrate the molecular regulatory mechanisms affecting temperature ranges related lignin biosynthesis, the expression patterns of lignin biosynthesis genes of Sl, Fhs, Ame, and Alh were analyzed. Overall, Sl and Fhs (located in Changbai Mountain), which experience lower temperature ranges, had higher lignin content than Ame and Alh (located in Daxing Anling) (Figures 1C, D and Supplementary Figures S3, S4). The expression levels of all known genes (except for BpCCR4) involved in lignin biosynthesis were significantly reduced in birch (Ame and Alh) with lower lignin content compared to those (Sl and Fhs) with higher lignin content (Figure 2A, Supplementary Figure S5 and Supplementary Tables S7–9). For example, BpPAL1 (Bpev01.c0042.g0040), encoding the first enzyme of the general phenylpropanoid pathway catalyzing the deamination of phenylalanine (Higuchi et al., 1997), was expressed 10-fold lower in the Ame and Alh than in the Sl and Fhs (p = 3.58E-09). Similarly, BpCOMT9 (Bpev01.c0210.g0051), that encodes a S-adenosylmethionine-dependent ortho-methyltransferase (Saluja et al., 2021), was expressed about three-fold lower in the Ame and Alh than in the Sl and Fhs individuals (p = 3.50E-07). Relative expression levels of several randomly-selected genes involved in lignin biosynthesis were further verified with qRT-PCR (Supplementary Figure S6). These results suggested that differences in the lignin content of natural birch may be related to the changes in the expression levels of lignin biosynthesis genes.

Figure 2 Expression profiles of lignin biosynthesis genes (A) and TFs (B) in Sl, Fhs, Ame, and Alh. Transcriptome levels for 12 lignin biosynthesis genes and 11 TFs were normalized to TPM (Transcripts Per Million). Colors represent the groups of birch trees (Sl and Fhs in green, and Ame and Alh in red). The t-test was used to evaluate the difference in gene expression between Sl, Fhs and Ame, Alh. The p ≤ 0.05 is marked as ‘*’, p ≤ 0.01 is marked as ‘**’, p ≤ 0.001 is marked as ‘***’.

Numerous TFs, such as the MYB-domain and NAC-domain TFs, have been reported to directly or indirectly regulate the expression of multiple downstream lignin biosynthesis genes (Nakano et al., 2015; Ohtani and Demura, 2019; Xiao et al., 2021). Here, we used BLAST alignment and phylogenetic analysis of known Arabidopsis lignin biosynthesis regulators to identify 18 homologous TFs in birch, 14 of which were putative positive regulators and 4 of which were putative negative regulators. (Supplementary Figure S7, Supplementary Table S7). Among the 14 TFs that may positively regulate lignin biosynthesis in birch, we found that the expression levels of 11 were significantly reduced in birch individuals with lower lignin content (Ame and Alh) than in those with higher lignin content (Sl and Fhs) (Figure 2B and Supplementary Tables S8 and S9). The remaining 3 putative positive regulators (BpVND6/7, Bpev01.c0022.g0005 and Bepv01.c0411.g0006; BpMYB61, Bpev01.c0918.g0016) were expressed at very low levels in all individuals. Notably, the expression level of BpNST1/2 (Bpev01.c0001.g0043) and BpSND1 (Bpev01.c0522.g0030), as the homologs of master controller of all three major secondary wall components in Arabidopsis (Fang et al., 2020), were significant decreased (p = 1.31E-07 and 2.68E-03, respectively) in birch with lower lignin content (Ame and Alh) than in those with the higher lignin content (Sl and Fhs), suggesting that the down-regulation of positively-regulated MYB-domain TFs and lignin biosynthesis genes may be subjected to these two NAC-domain TFs. In addition, the expression patterns of the 4 TFs that may negatively regulate lignin biosynthesis were not uniform (Supplementary Figure S8). For example, BpMYB3/4/7/32 (Bpev01.c0639.g0015) was expressed at lower levels in Ame (p = 5.37E-03), but BpMYB3/4/7/32 (Bpev01.c0668.g0007, and Bpev01.c0549.g0004) showed an enhanced expression (p = 5.60e-06 and 1.75E-04, respectively). Taken together, these results suggested that changes in the expression of lignin biosynthetic genes and of positively-regulated MYB-domain TFs (and thus in lignin content) are likely subject to expression of the two NAC-domain TFs, BpNST1/2 and BpSND1.

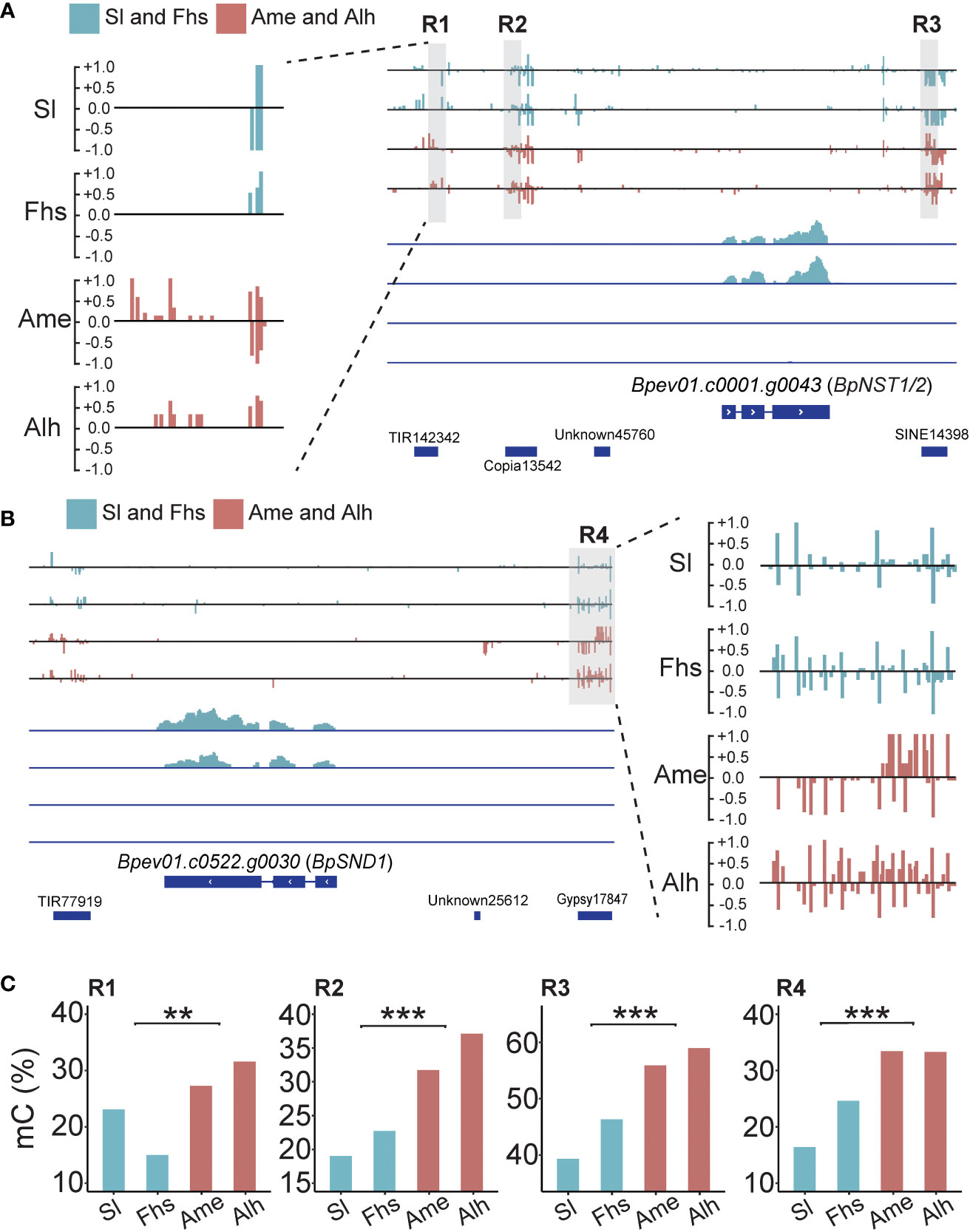

Previous studies have shown that DNA methylation variations caused by temperature changes may affect nearby gene expressions (Naydenov et al., 2015; He et al., 2018; Zhu et al., 2020). Here, we found four DMRs: three near BpNST1/2 (R1, R2 and R3) and one near BpSND1 (R4). All four had higher methylation levels in Ame and Alh than those in Sl and Fhs (Figure 3, Supplementary Figure S9 and Supplementary Table S10). For instance, the R1 region (Chr5:20,594,500-20,594,600) located on a TE (TIR142342) 3.5 kb upstream of BpNST1/2, where the weighted methylation level in Sl and Fhs (18.18%) was significantly lower than that in Ame and Alh (29.10%, p = 1.13E-03). Similarly, the R4 region (Chr14:277,346-277,605) located on a TE (Gypsy17847) 2.0 kb upstream of BpSND1, where the weighted methylation level in Sl and Fhs (20.51%) was significantly lower than that in Ame and Alh (33.36%, p = 1.47E-146). These results showed an opposite trend compared to the expression patterns observed for BpNST1/2 and BpSND1, suggesting that hypermethylation in the promoter regions of BpNST1/2 and BpSND1 may contribute to the repression of these genes expression.

Figure 3 Methylation and expression profiles of BpNST1/2 and BpSND1. (A) Methylation and transcript snapshot of BpNST1/2 in Sl, Fhs, Ame, and Alh. R1 (Chr5:20,594,500-20,594,600), R2 (Chr5:20,595,495-20,595,599) and R3 (Chr5:20,600,700-20,600,825) marked in grey box were identified as the DMRs nearby the BpNST1/2. The height of each column represents the methylation level at each cytosine. The lower part indicates the transcript level of BpNST1/2, ranging from 0 to 100. (B) Methylation and transcript snapshot of BpSND1 in Sl, Fhs, Ame, and Alh. R4 (Chr14:277,350-277,600) marked in grey box was identified as the DMRs located in promoter of BpSND1. The lower part indicates the transcript level of BpSND1, ranging from 0 to 30. (C) DNA methylation level of R1-R3 (BpNST1/2) and R4 (BpSND1) in Sl, Fhs, Ame, and Alh. The p ≤ 0.01 is marked as ‘**’ and p ≤ 0.001 is marked as ‘***’".

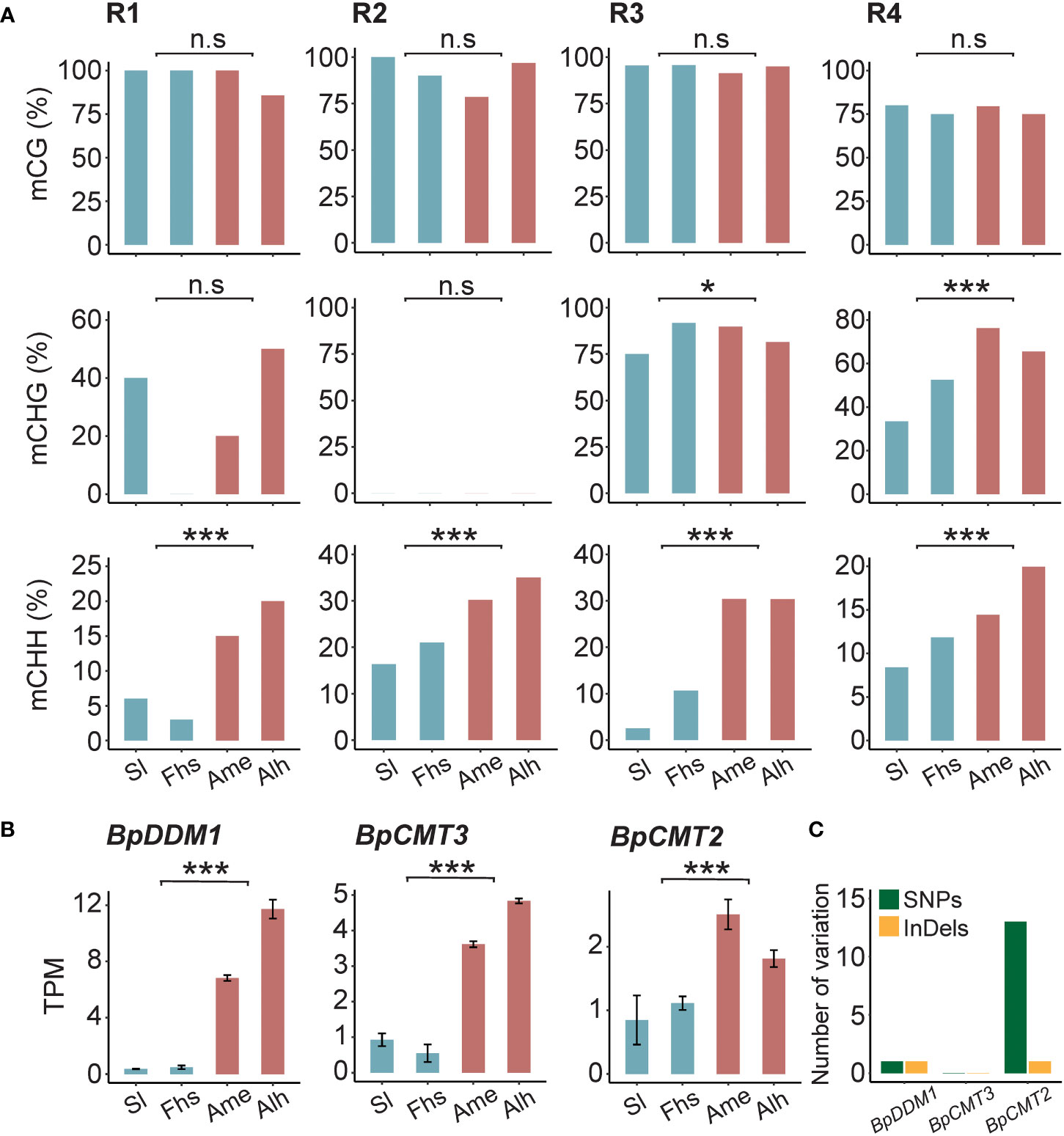

To assess whether the methylation patterns of BpNST1/2 and BpSND1 differed in sequence background, CG, CHG, and CHH methylation levels in the R1-R4 regions were calculated, respectively. We found that the CHH methylation levels of these 4 regions varied significantly between the two groups of birch, consistent with the trend of total methylation (Figures 4A, 3C and Supplementary Tables S10, S11). However, there was no such observations in CG methylation. For example, for the R1 region of BpNST1/2, the weighted CG methylation level of birch in Sl and Fhs (1.0) was not significantly different from that of Ame and Alh (0.94) (p = 5.29E-01). In contrast, Ame and Alh showed a significant increase in weighted CHH methylation (0.04 vs. 0.18, p = 2.84E-04). Small interfering RNA (siRNA) analysis indicated that CHH methylation variations of these 4 regions among different individuals were not correlated with the abundance of 24-nt siRNA (Supplementary Figure S10 and Supplementary Table S12), suggesting that the RdDM pathway may de novo establish the DNA methylation of these regions, but the maintenance of the DNA methylation subject to mitosis or meiosis is somehow affected by the natural environments (Elhamamsy, 2016; Johannes and Schmitz, 2019). Furthermore, the transcriptomes showed that the expression levels of three critical genes (BpCMT2, BpCMT3 and BpDDM1) involved in CHH methylation maintenance were significantly up-regulated in Ame and Alh, compared with those in Sl and Fhs (Figure 4B). Although we did not find homozygous non-synonymous mutations in the exons of these three genes between the two groups birch (Sl and Fhs vs. Ame and Alh), there are 14 (13 snp and 1 indel) and 2 (1 snp and 1 indel) potential natural selective genetic variants in the introns of BpCMT2 and BpDDM1, respectively (Figure 4C and Supplementary Table S13). In conclusion, we hypothesized that temperature ranges, such as Temperature Seasonality, may influence lignin biosynthesis by affecting the maintenance of non-CG methylation in the promoter regions of the BpNST1/2 and BpSND1.

Figure 4 DNA methylation of BpNST1/2 and BpSND1 in different sequence background. (A) CG, CHG and CHH methylation levels in the R1-R3 (BpNST1/2) and R4 (BpSND1), and (B) transcript level of BpDDM1, BpCMT3 and BpCMT2 in Sl, Fhs, Ame, and Alh. The p ≤ 0.05 is marked as ‘*’, p ≤ 0.001 is marked as ‘***’ and p > 0.05 is marked as ‘n.s’. (C) Number of nonsynonymous mutations in the introns of BpCMT2, BpCMT3 and BpDDM1. Genetic variants were counted when variants at the locus were completely distinct from Ame and Alh to Sl and Fhs.

Lignin is a group of phenolic polymers which is abundant in the woody tissues of vascular plants and has long been considered to play an important role in plant growth and development (Liljegren et al., 2000; Bonawitz et al., 2014; Peng et al., 2014). Recently, a few studies have shown that the lignin biosynthesis is related to plant adaptations to external stresses, such as metal exposure, drought, salinity, and temperature stresses (Mao et al., 2004; Moura-Sobczak et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2018). For example, Gindl et al. (2000) found that lignin deposition in the late terminal trachea of Norway spruce is positively correlated with temperature from early September to late October. Yun et al. (2013) found that high temperature stress can induce lignin deposition in Satsuma mandarin pericarp. Similarly, at 30°C, the accumulation of lignin in the MtCAD1 mutant of Medicago was inhibited and thus the vascular system was damaged, which led to impaired transpiration and overheating and thus the stalled growth (Zhao et al., 2013). In addition, an increased lignin production during cold acclimation has also been observed in several species, suggesting a physiological mechanism of freezing tolerance in trees (Griffith et al., 1985; Marzanna et al., 1999; Wei et al., 2006; Vitasse et al., 2014). Besides environmental factors, tree age is also shown to affect lignin content (Durkovic et al., 2012). However, the general trend is not consistent and somehow controversy with increase (Jahan and Mun, 2005; Rencoret et al., 2011), decrease (Stolarski et al., 2011; Healey et al., 2016) or no responses (Lachowicz et al., 2019) of lignin in wood being reported with tree aging. In this study, we found that the impact of the age of trees on lignin content was not significant (Supplementary Figure S2). This inconsistency among various studies may be ascribed to other factors, including the species, whether the wood came from a plantation or a natural forest, forest habitat type, the part of the tree from which samples were taken, the time of sampling, etc. (Lachowicz et al., 2019). Nevertheless, after controlling for the potential influence of tree age, we found that the lignin content of natural birch was significantly negatively correlated with the temperature ranges (bio4 and bio7) (Figure 1 and Supplementary Table S6). This suggested that temperature regimes can play a significant role in lignin biosynthesis, and that changes in lignin content may contribute to plants adaptations to fluctuations in temperature.

Uncovering the basis underlying the associations between traits and the environment is a central topic in molecular biology. At the molecular level, DNA methylation is thought to be involved in plant plasticity in the face of environmental stresses and/or climate changes, but solid evidence in natural population is few and mostly come from Arabidopsis. For example, the global DNA methylation of Arabidopsis accessions are negatively associated with the temperatures in Europe, in which the accessions with hypomethylomes are enriched in habitats with higher temperatures (Kawakatsu et al., 2016). The methylation level of NMR19, a naturally occurring epiallele controlling leaf senescence, is negatively associated with the Mean Temperature of Driest Quarter (bio9) (He et al., 2018). As one of the studies that focuses on trees, Wang et al. (2021) found that in natural birch the methylation variations of bHLH9 are associated with winter temperature and summer precipitation and affected betulin biosynthesis. Overall, these results suggested that temperature regimes are strong environmental factors that can shape the methylation patterns of key genes along their gradients. To support this, we found that DNA methylation levels of the two NAC-domain TFs (BpNST1/2 and BpSND1) were significantly correlated with the local Temperature Seasonality (bio4) and Temperature Annual Range (bio7) (Figures 1 and 3). These trends were strong, especially in CHH sequence context (Figure 4A). This result was consistent with the temperature-dependent characteristics of CHH methylation (Bewick and Schmitz, 2015), which probably caused by the differentiation of CMT2 alleles that participates the maintenance of CHH methylation status along temperature regime gradients, such as temperature (Dubin et al., 2015) and Temperature Seasonality (Shen et al., 2014). Indeed, we found 14 genetic differences in the intron of BpCMT2 between low and high temperature ranges regions (Figure 4C and Supplementary Table S13). These differences may form alleles and lead to different expression patterns of BpCMT2 or alter the splicing of mRNA. Additionally, there were significant expression differences of BpCMT3 and BpDDM1 but no and only 2 genetic variations in intron, respectively, between low and high temperature ranges regions (Figures 4B, C and Supplementary Table S13). Nevertheless, other factors, such as environmentally-induced DNA methylation (Miryeganeh et al., 2022), may also contribute to the differential expressions of BpCMT2, BpDDM1 and BpCMT3.

One of the crucial consequences of DNA methylation is to affect the gene expressions and thus contribute to phenotypic variations (Zemach et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2018). Several epigenetic variations with phenotypic consequences have been characterized as epialleles, such as plant architecture (Miura et al., 2009), flowering time (Ikeda et al., 2007), root length (Cortijo et al., 2014), and biomass (Ong-Abdullah et al., 2015). Although limited epialleles have been identified so far, transposons in which most epigenetic variations occur may be important carriers for epialleles (Slotkin and Martienssen, 2007). In birch, the content of transposons can be up to 50% with a relatively uniformly distribution in the genome, suggesting that this species is prone to have more epialleles (Salojarvi et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2021). To support this, we found that both differential methylation modifications of BpNST1/2 and BpSND1 occurred on transposons (TIR and Gypsy, respectively) within the gene promoter region and affected corresponding gene expressions (Figures 3A, B). Similarly, other genes, such as Bp4CL2, BpCOMT9, and BpMYB103, also differed significantly in their promoter (2 kb upstream of ATG) DNA methylation, which occurred on TEs (Copia, TIR and TIR) (Supplementary Figure S11 and Supplementary Table S14). These methylation variations were also opposite to their genes’ expression pattern (Figure 2). Thus, we cannot exclude the possibility that the DNA methylation modification of these genes’ promoter could be involved in regulating their expression. Yet, we believe that the differentiation of DNA methylation and the resultant gene expression patterns of BpNST1/2 and BpSND1, which are the first-layer switches in regulation of downstream lignin biosynthesis genes and MYB-domain TFs (Zhong et al., 2007; Golfier et al., 2017; Fang et al., 2020), are likely to be the main cause of the changes in these downstream genes’ expression and thus lignin biosynthesis. Further, we found that CHH and part of CHG methylation levels on transposons of BpNST1/2 and BpSND1 were negatively related to their expressions (Figures 2B, 4A), similar to the CMT2/3-dependent epiallele (Cnr) that regulates tomato fruit ripening in tomato (Chen et al., 2015). Likely, we recently found that CHH methylation can be involved in anthocyanin biosynthesis (another downstream branch of the phenylpropane metabolic pathway) by affecting the expression of CmMYB6 in chrysanthemum (Tang et al., 2022). We hypothesized that CHH as well as CHG methylation can form a heterochromatin by coupling with the H3K9me2, thereby inhibiting the gene expression by restricting the access of TFs to their binding sites in promoters, which may ultimately result in the changes of lignin content. This positive feedback loop between H3K9me2 and non-CG methylation has also been considered as a major contributing factor to the origins of spontaneous epialleles and that heterochromatin is a quantitative trait that influences epiallele formation (Zhang et al., 2021).

Cellulose and hemicellulose are also the target products regulated by BpNST1/2 and BpSND1. We evaluated the transcript levels of critical cellulose and hemicellulose biosynthesis genes (10 homologs of BpCesA and 11 homologs of BpCsl) in Sl, Fhs, Ame, and Alh (Supplementary Figure S12 and Supplementary Table S15). The gene expression levels of BpCesA04, BpCesA07, and BpCesA08, which function mainly in the secondary plant cell wall (Desprez et al., 2007; Persson et al., 2007), were significantly decreased in Ame and Alh (trees with high temperature ranges) compared with Sl and Fhs (trees with low temperature ranges), and this expression pattern was highly consistent with the expression of BpSND1 (Figure 2B). Further, the expression level of BpCslB and BpCslG subfamilies, which are specific in non-grass angiosperms (Keegstra and Walton, 2006; Suzuki et al., 2006), were tightly correlated with that of BpNST1/2 and BpSND1 (Supplementary Figure S13 and Supplementary Table S15). Based on these findings, we hypothesised that these two gene families (CesA and Csl) may be commonly indirectly regulated by NST1/2 and SND1 in trees, and likely play a role in the biosynthesis of cellulose and hemicellulose in second cell wall of woody plants.

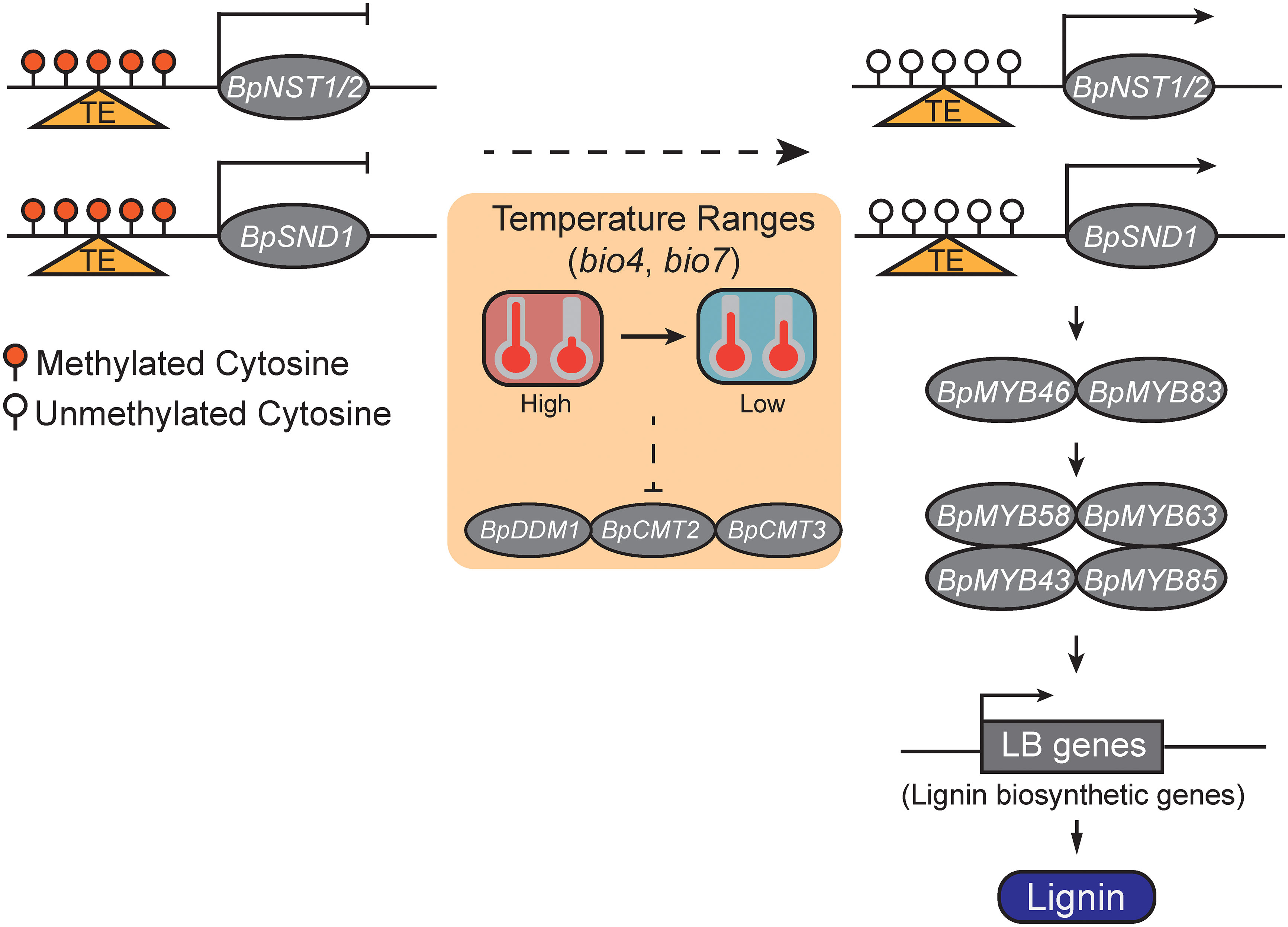

To summary, we proposed a DNA methylation-mediated lignin biosynthesis model which responds to environmental factors (Figure 5). Specifically, relatively low temperature ranges may decrease DNA methylation levels of BpNST1/2 and BpSND1, and lead to the enhanced expressions of BpNST1/2 and BpSND1 and the downstream MYB-domain TFs and lignin biosynthesis genes, and ultimately, result in a high level of lignin content. However, manipulated experiments are needed to test whether DNA methylation of BpNST1/2 and BpSND1 can be directly altered by Temperature Seasonality and/or Temperature Annual Range (TAR), and if variation of these methylation is heritable.

Figure 5 A schematic model of temperature ranges (TRs) responsive DNA methylation involved in lignin biosynthesis via the regulation of the expression of BpNST1/2 and BpSND1. The small red balloons represent highly methylated cytosines, white ones represent unmethylated cytosines, and the triangles in orange indicate a genomic region with transposable element (TE) insertion. With a decreasing of TRs, the methylation levels of the promoter region of the BpNST1/2 and BpSND1 decrease and their expressions are thus enhanced, leading to the up-regulation of downstream MYB-domain TFs and lignin biosynthesis genes and, ultimately, increasing the content of lignin in birch.

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding authors. The sequencing data are available through the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under the accession number PRJNA902946.

BC, JW, SS, and QZ conducted the experimental design, data analysis, and prepared the manuscript. YG, XZ, LW, TZ, LC, ZZ and WZ provided help in carrying out the experiments and guidance in designing the research. QZ, CY, SS, JW, LX and BC interpreted the results and modified the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China during the 14th Five-year Plan Period (2021YFD2200304), Heilongjiang Touyan Innovation Team Program (Tree Genetics and Breeding Innovation Team), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31871220, 62273086, 62001088), the National Nonprofit Institute Research Grant of the Chinese Academy of Forestry (CAFYBB2019ZY003), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2572022BD04, 2572018AA27).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2022.1090967/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Figure 1 | Sampling sites of naturally growing birch in the northeast China. Each dot in orange indicates the sampling site. Accessions 1 to 19 (except 4 and 5) belong to Changbai Mountain; 24 to 35 belong to Xiaoxing Anling; 36 to 59 (including 4 and 5) belong to Daxing Anling; 20 to 23 belong to Sanjiang Plain.

Supplementary Figure 2 | Correlation analysis between tree age and lignin content. Spearman’s correlation analysis was used to assess the relationship between the tree age and lignin content.

Supplementary Figure 3 | Comparisons of Temperature Annual Range (bio7) in Sl, Fhs, Ame and Alh.

Supplementary Figure 4 | Visualization of the relationship between lignin content and Temperature Annual Range (bio7) in the northeast China. The color of the point in the background reflects the value of bio7, with darker for a higher value and lighter for a lower value. The color of sampling sites reflects the lignin content, with a redder color for a higher content and vice versa.

Supplementary Figure 5 | Transcript level of the BpCCR4. The p ≤ 0.001 is marked as ‘***’.

Supplementary Figure 6 | Relative expressions of randomly-selected genes assessed with qRT- PCR. The t-test was used to evaluate the difference in genes expression between the two groups of birch trees. p ≤ 0.01 is marked as ‘**’ and p ≤ 0.001 is marked as ‘***’.

Supplementary Figure 7 | Phylogenetic analysis of NAC-domain and MYB-domain TFs involved in lignin biosynthesis of birch and Arabidopsis. The rooted neighbor-joining (NJ) phylogenetic tree of TFs was clustered with bootstrap values shown for each clade in circles with a different size. Genes in bold with black circle outside is for the candidate genes that most probably encode phenylpropanoid biosynthesis enzymes.

Supplementary Figure 8 | Transcript level of BpMYB3/4/7/32. The p ≤ 0.05 is marked as ‘*’, p ≤ 0.01 is marked as ‘**’ and p > 0.05 is marked as ‘n.s’.

Supplementary Figure 9 | Snapshots of DNA methylation of R2 and R3 in Sl, Fhs, Ame, and Alh. The height of each column represents the methylation level at each cytosine.

Supplementary Figure 10 | Snapshots of (A) CHH methylation and (B) 24nt-siRNA of R1-R4 in Sl, Fhs, Ame, and Alh. Of the methylation snapshot, the height of each column represents the methylation level at each cytosine in CHH context. Of the 24nt-siRNA snapshot, the height of each column represents the RPM of 24nt-siRNA in 10 bp window. (C) The bar chart indicates the RPM of 24nt-siRNA for each region (R1-R4).

Supplementary Figure 11 | Promoter DNA methylation level of lignin biosynthesis genes and TFs in birch. (A) Heatmap of DNA methylation levels in the promoter regions (2kb upstream of ATG) of genes involved in lignin biosynthesis. (B) Methylation snapshot of Bp4CL2, BpCOMT9 and BpMYB103 in Sl, Fhs, Ame, and Alh. Box in grey color indicate regions with pronounced methylation variations in their promoter region.

Supplementary Figure 12 | Transcript level of BpCesAs in birch. (A) Phylogenetic analysis of CesAs of birch and Arabidopsis. The rooted neighbor-joining (NJ) phylogenetic tree of CesAs was clustered with bootstrap values shown for each clade in circles with a different size. The CesAs of Arabidopsis with green star outside function mainly in second plant cell wall, and those with blue star outside function mainly in primary plant cell wall. “?” indicates the function of the gene is remain unclear. (B) Transcript level of BpCesAs in Sl, Fhs, Ame, and Alh. The t-test was used to evaluate the difference in genes expression between the Sl, Fhs and Ame, Alh. The p ≤ 0.01 is marked as ‘**’, p ≤ 0.001 is marked as ‘***’, and p > 0.05 is marked as ‘n.s’.

Supplementary Figure 13 | Transcript level of BpCsls in birch. (A) Phylogenetic analysis of Csls of birch and Arabidopsis. The rooted neighbor-joining (NJ) phylogenetic tree of Csls was clustered with bootstrap values shown for each clade in circles with a different size. Birch genes with black circle outside is for the candidate genes that most probably encode Csls in birch. (B) Transcript pattern of BpCsls in Sl, Fhs, Ame, and Alh.

Akgul, M., Copur, Y., Temiz, S. (2007). A comparison of kraft and kraft-sodium borohydrate brutia pine pulps. Build. Sci. 42, 2586–2590. doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2006.07.022

Alejandro, S., Lee, Y., Tohge, T., Sudre, D., Osorio, S., Park, J., et al. (2012). AtABCG29 is a monolignol transporter involved in lignin biosynthesis. Curr. Biol. 22, 1207–1212. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.04.064

Arni, S. A. (2018). Extraction and isolation methods for lignin separation from sugarcane bagasse: A review. Ind. Crops Prod. 115, 330–339. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2018.02.012

Barber, M. S., Mitchell, H. J. (1997). Regulation of phenylpropanoid metabolism in relation to lignin biosynthesis in plants. Int. Rev. Cytol. 172, 243–293. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(08)62362-1

Bewick, A. J., Schmitz, R. J. (2015). Epigenetics in the wild. Elife 4, e07808. doi: 10.7554/eLife.07808

Bita, C. E., Gerats, T. (2013). Plant tolerance to high temperature in a changing environment: Scientific fundamentals and production of heat stress-tolerant crops. Front. Plant Sci. 4. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00273

Bonawitz, N. D., Kim, J. I., Tobimatsu, Y., Ciesielski, P. N., Anderson, N. A., Ximenes, E., et al. (2014). Disruption of mediator rescues the stunted growth of a lignin-deficient Arabidopsis mutant. Nature 509, 376–380. doi: 10.1038/nature13084

Cesarino, I. (2019). Structural features and regulation of lignin deposited upon biotic and abiotic stresses. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 56, 209–214. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2018.12.012

Chen, E. L., Chen, Y. A., Chen, L. M., Liu, Z. H. (2002). Effect of copper on peroxidase activity and lignin content in Raphanus sativus. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 40, 439–444. doi: 10.1016/S0981-9428(02)01392-X

Chen, W. W., Kong, J. H., Qin, C., Yu, S., Tan, J. J., Chen, Y. R., et al. (2015). Requirement of CHROMOMETHYLASE3 for somatic inheritance of the spontaneous tomato epimutation colourless non-ripening. Sci. Rep. 5, 9192. doi: 10.1038/srep09192

Chen, S., Zhao, Y. M., Zhao, X. Y., Chen, S. (2020). Identification of putative lignin biosynthesis genes in Betula pendula. Trees 34, 1255–1265. doi: 10.1007/s00468-020-01995-8

Chen, S. F., Zhou, Y. Q., Chen, Y. R., Gu, J. (2018). Fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34, 884–890. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty560

Christensen, J. H., Christensen, O. B. (2007). A summary of the PRUDENCE model projections of changes in European climate by the end of this century. Clim. Change 81, 7–30. doi: 10.1007/s10584-006-9210-7

Chun, H. J., Baek, D., Cho, H. M., Lee, S. H., Jin, B. J., Yun, D. J., et al. (2019). Lignin biosynthesis genes play critical roles in the adaptation of Arabidopsis plants to high-salt stress. Plant Signaling Behav. 14, 1625697. doi: 10.1080/15592324.2019.1625697

Cortijo, S., Wardenaar, R., Colome-Tatche, M., Gilly, A., Etcheverry, M., Labadie, K., et al. (2014). Mapping the epigenetic basis of complex traits. Science 343, 1145–1148. doi: 10.1126/science.1248127

Davey, M. P., Bryant, D. N., Cummins, I., Ashenden, T. W., Gates, P., Baxter, R., et al. (2004). Effects of elevated CO2 on the vasculature and phenolic secondary metabolism of Plantago maritima. Phytochemistry 65, 2197–2204. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2004.06.016

Desprez, T., Juraniec, M., Crowell, E. F., Jouy, H., Pochylova, Z., Parcy, F., et al. (2007). Organization of cellulose synthase complexes involved in primary cell wall synthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104, 15572–15577. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706569104

Dubin, M. J., Zhang, P., Meng, D. Z., Remigereau, M. S., Osborne, E. J., Casale, F. P., et al. (2015). DNA Methylation in Arabidopsis has a genetic basis and shows evidence of local adaptation. Elife 4, e05255. doi: 10.7554/eLife.05255

Durkovic, J., Kanuchova, A., Kacik, F., Solar, R., Lengyelova, A. (2012). Genotype- and age-dependent patterns of lignin and cellulose in regenerants derived from 80-year-old trees of black mulberry (Morus nigra l.). Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 108, 359–370. doi: 10.1007/s11240-011-0047-z

Elhamamsy, A. R. (2016). DNA Methylation dynamics in plants and mammals: Overview of regulation and dysregulation. Cell Biochem. Funct. 34, 289–298. doi: 10.1002/cbf.3183

Fang, S., Shang, X. G., Yao, Y., Li, W. X., Guo, W. Z. (2020). NST- and SND-subgroup NAC proteins coordinately act to regulate secondary cell wall formation in cotton. Plant Sci. 301, 110657. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2020.110657

Fick, S. E., Hijmans, R. J. (2017). WorldClim 2: New 1-km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 37, 4302–4315. doi: 10.1002/joc.5086

Fraser, C. M., Chapple, C. (2011). The phenylpropanoid pathway in Arabidopsis. Arabidopsis Book 9, e0152. doi: 10.1199/tab.0152

Geng, W. L., Li, Y. Y., Sun, D. Q., Li, B., Zhang, P. Y., Chang, H., et al. (2022). Prediction of the potential geographical distribution of Betula platyphylla suk. in China under climate change scenarios. PloS One 17, e0262540. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0262540

Gindl, W., Grabner, M., Wimmer, R. (2000). The influence of temperature on latewood lignin content in treeline Norway spruce compared with maximum density and ring width. Trees 14, 409–414. doi: 10.1007/s004680000057

Golfier, P., Volkert, C., He, F., Rausch, T., Wolf, S. (2017). Regulation of secondary cell wall biosynthesis by a NAC transcription factor from Miscanthus. Plant Direct 1, e00024. doi: 10.1002/pld3.24

Griffith, M., Huner, N. P. A., Espelie, K. E., Kolattukudy, P. E. (1985). Lipid polymers accumulate in the epidermis and mestome sheath cell walls during low temperature development of winter rye leaves. Protoplasma 125, 53–64. doi: 10.1007/BF01297350

Gugger, P. F., Fitz-Gibbon, S., Pellegrini, M., Sork, V. L. (2016). Species-wide patterns of DNA methylation variation in Quercus lobata and their association with climate gradients. Mol. Ecol. 25, 1665–1680. doi: 10.1111/mec.13563

Guo, S. L., Zhang, D. H., Wei, H. Y., Zhao, Y. N., Cao, Y. B., Yu, T., et al. (2017). Climatic factors shape the spatial distribution of concentrations of triterpenoids in barks of white birch (Betula platyphylla suk.) trees in northeast China. Forests 8, 334. doi: 10.3390/f8090334

Gu, H. L., Wang, Y., Xie, H., Qiu, C., Zhang, S. N., Xiao, J., et al. (2020). Drought stress triggers proteomic changes involving lignin, flavonoids and fatty acids in tea plants. Sci. Rep. 10, 15504. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-72596-1

Healey, A. L., Lupoi, J. S., Lee, D. J., Sykes, R. W., Guenther, J. M., Tran, K., et al. (2016). Effect of aging on lignin content, composition and enzymatic saccharification in Corymbia hybrids and parental taxa between years 9 and 12. Biomass Bioenergy 93, 50–59. doi: 10.1016/j.biombioe.2016.06.016

He, L., Wu, W. W., Zinta, G., Yang, L., Wang, D., Liu, R. Y., et al. (2018). A naturally occurring epiallele associates with leaf senescence and local climate adaptation in Arabidopsis accessions. Nat. Commun. 9, 460. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-02839-3

Higuchi, Y., Yagi, T., Yasuoka, N. (1997). Unusual ligand structure in Ni-fe active center and an additional mg site in hydrogenase revealed by high resolution X-ray structure analysis. Structure 5, 1671–1680. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(97)00313-4

Ikeda, Y., Kobayashi, Y., Yamaguchi, A., Abe, M., Araki, T. (2007). Molecular basis of late-flowering phenotype caused by dominant epi-alleles of the FWA locus in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 48, 205–220. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcl061

Jahan, M. S., Mun, S. P. (2005). Effect of tree age on the cellulose structure of nalita wood (Trema orientalis). Wood Sci. Technol. 39, 367–373. doi: 10.1007/s00226-005-0291-7

Johannes, F., Schmitz, R. J. (2019). Spontaneous epimutations in plants. New Phytol. 221, 1253–1259. doi: 10.1111/nph.15434

Kawakatsu, T., Huang, S. S. C., Jupe, F., Sasaki, E., Schmitz, R. J., Urich, M. A., et al. (2016). Epigenomic diversity in a global collection of Arabidopsis thaliana accessions. Cell 166, 492–505. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.06.044

Keegstra, K., Walton, J. (2006). β-glucans - brewer’s bane, dietician’s delight. Science 311, 1872–1873. doi: 10.1126/science.1125938

Kim, D., Paggi, J. M., Park, C., Bennett, C., Salzberg, S. L. (2019). Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 907–915. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0201-4

Ko, J. H., Jeon, H. W., Kim, W. C., Kim, J. Y., Han, K. H. (2014). The MYB46/MYB83-mediated transcriptional regulatory programme is a gatekeeper of secondary wall biosynthesis. Ann. Bot. 114, 1099–1107. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcu126

Kubo, M., Udagawa, M., Nishikubo, N., Horiguchi, G., Yamaguchi, M., Ito, J., et al. (2005). Transcription switches for protoxylem and metaxylem vessel formation. Genes Dev. 19, 1855–1860. doi: 10.1101/gad.1331305

Lachowicz, H., Wroblewska, H., Wojtan, R., Sajdak, M. (2019). The effect of tree age on the chemical composition of the wood of silver birch (Betula pendula roth.) in Poland. Wood Sci. Technol. 53, 1135–1155. doi: 10.1007/s00226-019-01121-z

Langmead, B., Trapnell, C., Pop, M., Salzberg, S. L. (2009). Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 10, R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25

Law, J. A., Jacobsen, S. E. (2010). Establishing, maintaining and modifying DNA methylation patterns in plants and animals. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11, 204–220. doi: 10.1038/nrg2719

Liang, M. X., Davis, E., Gardner, D., Cai, X. N., Wu, Y. J. (2006). Involvement of AtLAC15 in lignin synthesis in seeds and in root elongation of Arabidopsis. Planta 224, 1185–1196. doi: 10.1007/s00425-006-0300-6

Li, B., Cai, H. Y., Liu, K., An, B. Z., Wang, R., Yang, F., et al. (2022). DNA Methylation alterations and their association with high temperature tolerance in rice anthesis. J. Plant Growth Regul. doi: 10.1007/s00344-022-10586-5

Li, H., Durbin, R. (2009). Fast and accurate short read alignment with burrows-wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324

Li, Y. X., Li, W. (2009). BSMAP: Whole genome bisulfite sequence MAPping program. BMC Bioinf. 10, 232. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-232

Liljegren, S. J., Ditta, G. S., Eshed, Y., Savidge, B., Bowman, J. L., Yanofsky, M. F. (2000). SHATTERPROOF MADS-box genes control seed dispersal in Arabidopsis. Nature 404, 766–770. doi: 10.1038/35008089

Liu, Y. J., Li, D., Gong, J., Wang, Y. B., Chen, Z. B., Pang, B. S., et al. (2021). Comparative transcriptome and DNA methylation analysis in temperature-sensitive genic male sterile wheat BS366. BMC Genomics 22, 911. doi: 10.1186/s12864-021-08163-3

Liu, Q. Q., Luo, L., Zheng, L. Q. (2018). Lignins: Biosynthesis and biological functions in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, 335. doi: 10.3390/ijms19020335

Liu, C. J., Miao, Y. C., Zhang, K. W. (2011). Sequestration and transport of lignin monomeric precursors. Molecules 16, 710–727. doi: 10.3390/molecules16010710

Mao, C. Z., Yi, K., Yang, L., Zheng, B. S., Wu, Y. R., Liu, F. Y., et al. (2004). Identification of aluminium-regulated genes by cDNA-AFLP in rice (Oryza sativa l.): Aluminium-regulated genes for the metabolism of cell wall components. J. Exp. Bot. 55, 137–143. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erh030

Marzanna, S., Mieczysław, K., Maria, K. Z., Alina, K. (1999). Low temperature affects pattern of leaf growth and structure of cell walls in winter oilseed rape (Brassica napus l., var. oleifera l.). Ann. Bot. 84, 313–319. doi: 10.1006/anbo.1999.0924

McCaw, B. A., Stevenson, T. J., Lancaster, L. T. (2020). Epigenetic responses to temperature and climate. Integr. Comp. Biol. 60, 1469–1480. doi: 10.1093/icb/icaa049

Miryeganeh, M., Marletaz, F., Gavriouchkina, D., Saze, H. (2022). De novo genome assembly and in natura epigenomics reveal salinity-induced DNA methylation in the mangrove tree Bruguiera gymnorhiza. New Phytol. 233, 2094–2110. doi: 10.1111/nph.17738

Miura, K., Agetsuma, M., Kitano, H., Yoshimura, A., Matsuoka, M., Jacobsen, S. E., et al. (2009). A metastable DWARF1 epigenetic mutant affecting plant stature in rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106, 11218–11223. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901942106

Monties, B., Fukushima, K. (2001). Occurrence, function and biosynthesis of lignins. Biopolymers 1, 1–64. doi: 10.1002/3527600035.bpol1001

Moura, J., Bonine, C. A. V., Viana, J. D. F., Dornelas, M. C., Mazzafera, P. (2010). Abiotic and biotic stresses and changes in the lignin content and composition in plants. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 52, 360–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2010.00892.x

Moura-Sobczak, J., Souza, U., Mazzafera, P. (2011). Drought stress and changes in the lignin content and composition in Eucalyptus. BMC Proc. 5, P103. doi: 10.1186/1753-6561-5-S7-P103

Nakano, Y., Yamaguchiz, M., Endo, H., Rejab, N. A., Ohtani, M. (2015). NAC-MYB-based transcriptional regulation of secondary cell wall biosynthesis in land plants. Front. Plant Sci. 6. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00288

Naydenov, M., Baev, V., Apostolova, E., Gospodinova, N., Sablok, G., Gozmanova, M., et al. (2015). High-temperature effect on genes engaged in DNA methylation and affected by DNA methylation in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 87, 102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2014.12.022

Ohtani, M., Demura, T. (2019). The quest for transcriptional hubs of lignin biosynthesis: Beyond the NAC-MYB-gene regulatory network model. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 56, 82–87. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2018.10.002

Ong-Abdullah, M., Ordway, J. M., Jiang, N., Ooi, S. E., Kok, S. Y., Sarpan, N., et al. (2015). Loss of Karma transposon methylation underlies the mantled somaclonal variant of oil palm. Nature 525, 533–537. doi: 10.1038/nature15365

Pan, H., Yang, C., Wei, Z., Jiang, J. (2006). DNA Extraction of birch leaves by improved CTAB method and optimization of its ISSR system. J. For. Res. 17, 298–300. doi: 10.1007/s11676-006-0068-3

Peng, D. L., Chen, X. G., Yin, Y. P., Lu, K. L., Yang, W. B., Tang, Y. H., et al. (2014). Lodging resistance of winter wheat (Triticum aestivum l.): Lignin accumulation and its related enzymes activities due to the application of paclobutrazol or gibberellin acid. Field Crops Res. 157, 1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2013.11.015

Persson, S., Paredez, A., Carroll, A., Palsdottir, H., Doblin, M., Poindexter, P., et al. (2007). Genetic evidence for three unique components in primary cell-wall cellulose synthase complexes in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104, 15566–15571. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706592104

Pertea, M., Pertea, G. M., Antonescu, C. M., Chang, T. C., Mendell, J. T., Salzberg, S. L. (2015). StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 290–295. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3122

Poplin, R., Ruano-Rubio, V., DePristo, M. A., Fennell, T. J., Carneiro, M. O., van der Auwera, G. A., et al. (2018). Scaling accurate genetic variant discovery to tens of thousands of samples. bioRxiv 201178. doi: 10.1101/201178

Raes, J., Rohde, A., Christensen, J. H., Van de Peer, Y., Boerjan, W. (2003). Genome-wide characterization of the lignification toolbox in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 133, 1051–1071. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.026484

Rencoret, J., Gutierrez, A., Nieto, L., Jimenez-Barbero, J., Faulds, C. B., Kim, H., et al. (2011). Lignin composition and structure in young versus adult Eucalyptus globulus plants. Plant Physiol. 155, 667–682. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.167254

Rienth, M., Vigneron, N., Darriet, P., Sweetman, C., Burbidge, C., Bonghi, C., et al. (2021). Grape berry secondary metabolites and their modulation by abiotic factors in a climate change scenario-a review. Front. Plant Sci. 12. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.643258

Rozema, J., van de Staaij, J., Bjorn, L. O., Caldwell, M. (1997). UV-B as an environmental factor in plant life: Stress and regulation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 12, 22–28. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5347(96)10062-8

Sadeghi, K., Marchetti, G. M. (2012). Graphical markov models with mixed graphs in r. R J. 4, 65–73. doi: 10.32614/RJ-2012-015

Saha, M., Saynik, P. B., Borah, A., Malani, R. S., Arya, P., Shivangi, et al. (2019). Dioxane-based extraction process for production of high quality lignin. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 5, 206–211. doi: 10.1016/j.biteb.2019.01.018

Salojarvi, J., Smolander, O. P., Nieminen, K., Rajaraman, S., Safronov, O., Safdari, P., et al. (2017). Genome sequencing and population genomic analyses provide insights into the adaptive landscape of silver birch. Nat. Genet. 49, 904–912. doi: 10.1038/ng.3862

Saluja, M., Zhu, F. Y., Yu, H. F., Walia, H., Sattler, S. E. (2021). Loss of COMT activity reduces lateral root formation and alters the response to water limitation in sorghum brown midrib (bmr) 12 mutant. New Phytol. 229, 2780–2794. doi: 10.1111/nph.17051

Shen, X., De Jonge, J., Forsberg, S. K. G., Pettersson, M. E., Sheng, Z. Y., Hennig, L., et al. (2014). Natural CMT2 variation is associated with genome-wide methylation changes and temperature seasonality. PloS Genet. 10, e1004842. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004842

Skern, R., Frost, P., Nilsen, F. (2005). Relative transcript quantification by quantitative PCR: Roughly right or precisely wrong? BMC Mol. Biol. 6, 10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-6-10

Slotkin, R. K., Martienssen, R. (2007). Transposable elements and the epigenetic regulation of the genome. Nat. Rev. Genet. 8, 272–285. doi: 10.1038/nrg2072

South, A. (2011). Rworldmap: A new r package for mapping global data. R J. 3, 35–43. doi: 10.32614/RJ-2011-006

Steward, N., Ito, M., Yamaguchi, Y., Koizumi, N., Sano, H. (2002). Periodic DNA methylation in maize nucleosomes and demethylation by environmental stress. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 37741–37746. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204050200

Stolarski, M. J., Szczukowski, S., Tworkowski, J., Wroblewska, H., Krzyzaniak, M. (2011). Short rotation willow coppice biomass as an industrial and energy feedstock. Ind. Crops Prod. 33, 217–223. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2010.10.013

Stroud, H., Do, T., Du, J. M., Zhong, X. H., Feng, S. H., Johnson, L., et al. (2014). Non-CG methylation patterns shape the epigenetic landscape in Arabidopsis. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 21, 64–72. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2735

Sun, M. H., Yang, Z., Liu, L., Duan, L. (2022). DNA Methylation in plant responses and adaption to abiotic stresses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 6910. doi: 10.3390/ijms23136910

Suzuki, S., Li, L. G., Sun, Y. H., Chiang, V. L. (2006). The cellulose synthase gene superfamily and biochemical functions of xylem-specific cellulose synthase-like genes in Populus trichocarpa. Plant Physiol. 142, 1233–1245. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.086678

Tang, M. W., Xue, W. J., Li, X. Q., Wang, L. S., Wang, M., Wang, W. P., et al. (2022). Mitotically heritable epigenetic modifications of CmMYB6 control anthocyanin biosynthesis in chrysanthemum. New Phytol. 236, 1075–1088. doi: 10.1111/nph.18389

Vitasse, Y., Lenz, A., Korner, C. (2014). The interaction between freezing tolerance and phenology in temperate deciduous trees. Front. Plant Sci. 5. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00541

Wang, J., Chen, B. W., Ali, S., Zhang, T. X., Wang, Y., Zhang, H., et al. (2021). Epigenetic modification associated with climate regulates betulin biosynthesis in birch. J. For. Res. doi: 10.1007/s11676-021-01424-7

Wang, Q. S., Ci, D., Li, T., Li, P. W., Song, Y. P., Chen, J. H., et al. (2016). The role of DNA methylation in xylogenesis in different tissues of poplar. Front. Plant Sci. 7. doi: 10.3389/fbls.2016.01003

Wang, J. P., Matthews, M. L., Williams, C. M., Shi, R., Yang, C. M., Tunlaya-Anukit, S., et al. (2018). Improving wood properties for wood utilization through multi-omics integration in lignin biosynthesis. Nat. Commun. 9, 1579. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03863-z

Wei, H., Dhanaraj, A. L., Arora, R., Rowland, L. J., Fu, Y., Sun, L. (2006). Identification of cold acclimation-responsive Rhododendron genes for lipid metabolism, membrane transport and lignin biosynthesis: Importance of moderately abundant ESTs in genomic studies. Plant Cell Environ. 29, 558–570. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2005.01432.x

Xiao, R. X., Zhang, C., Guo, X. R., Li, H., Lu, H. (2021). MYB transcription factors and its regulation in secondary cell wall formation and lignin biosynthesis during xylem development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 3560. doi: 10.3390/ijms22073560

Xie, M., Zhang, J., Tschaplinski, T. J., Tuskan, G. A., Chen, J. G., Muchero, W. (2018). Regulation of lignin biosynthesis and its role in growth-defense tradeoffs. Front. Plant Sci. 9. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01427

Yoon, J., Choi, H., An, G. (2015). Roles of lignin biosynthesis and regulatory genes in plant development. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 57, 902–912. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12422

Yun, Z., Gao, H., Liu, P., Liu, S., Luo, T., Jin, S., et al. (2013). Comparative proteomic and metabolomic profiling of citrus fruit with enhancement of disease resistance by postharvest heat treatment. BMC Plant Biol. 13, 44. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-13-44

Zagoskina, N. V., Goncharuk, E. A., Alyavina, A. K. (2007). Effect of cadmium on the phenolic compounds formation in the callus cultures derived from various organs of the tea plant. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 54, 237–243. doi: 10.1134/s1021443707020124

Zemach, A., Kim, M. Y., Hsieh, P. H., Coleman-Derr, D., Eshed-Williams, L., Thao, K., et al. (2013). The Arabidopsis nucleosome remodeler DDM1 allows DNA methyltransferases to access H1-containing heterochromatin. Cell 153, 193–205. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.033

Zeng, J. K., Li, X., Zhang, J., Ge, H., Yin, X. R., Chen, K. S. (2016). Regulation of loquat fruit low temperature response and lignification involves interaction of heat shock factors and genes associated with lignin biosynthesis. Plant Cell Environ. 39, 1780–1789. doi: 10.1111/pce.12741

Zhang, Y. W., Jang, H., Xiao, R., Kakoulidou, I., Piecyk, R. S., Johannes, F., et al. (2021). Heterochromatin is a quantitative trait associated with spontaneous epiallele formation. Nat. Commun. 12, 6958. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-27320-6

Zhang, H. M., Lang, Z. B., Zhu, J. K. (2018). Dynamics and function of DNA methylation in plants. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 19, 489–506. doi: 10.1038/s41580-018-0016-z

Zhang, Q. Z., Wang, D., Lang, Z. B., He, L., Yang, L., Zeng, L., et al. (2016). Methylation interactions in Arabidopsis hybrids require RNA-directed DNA methylation and are influenced by genetic variation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 113, E4248–E4256. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1607851113

Zhao, Q., Tobimatsu, Y., Zhou, R., Pattathil, S., Gallego-Giraldo, L., Fu, C., et al. (2013). Loss of function of cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase 1 leads to unconventional lignin and a temperature-sensitive growth defect in Medicago truncatula. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 110, 13660–13665. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1312234110

Zhong, R. Q., Richardson, E. A., Ye, Z. H. (2007). Two NAC domain transcription factors, SND1 and NST1, function redundantly in regulation of secondary wall synthesis in fibers of Arabidopsis. Planta 225, 1603–1611. doi: 10.1007/s00425-007-0498-y

Keywords: lignin, climate change, DNA methylation, BpNST1/2 and BpSND1, secondary metabolite

Citation: Chen B, Guo Y, Zhang X, Wang L, Cao L, Zhang T, Zhang Z, Zhou W, Xie L, Wang J, Sun S, Yang C and Zhang Q (2022) Climate-responsive DNA methylation is involved in the biosynthesis of lignin in birch. Front. Plant Sci. 13:1090967. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.1090967

Received: 06 November 2022; Accepted: 22 November 2022;

Published: 02 December 2022.

Edited by:

Yunjun Zhao, Center for Excellence in Molecular Plant Sciences (CAS), Shanghai, ChinaReviewed by:

Dongliang Song, Yeasen Biotechnology (Shanghai) Co., Ltd., ChinaCopyright © 2022 Chen, Guo, Zhang, Wang, Cao, Zhang, Zhang, Zhou, Xie, Wang, Sun, Yang and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jiang Wang, amlhbmd3YW5nQG5lZnUuZWR1LmNu; Shanwen Sun, c3Vuc2hhbndlbkBuZWZ1LmVkdS5jbg==; Chuanping Yang, eWFuZ2NwQG5lZnUuZWR1LmNu; Qingzhu Zhang, cWluZ3podS56aGFuZ0BuZWZ1LmVkdS5jbg==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.