94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Plant Sci., 19 January 2023

Sec. Plant Development and EvoDevo

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.1051017

Haruaki Kobayashi1

Haruaki Kobayashi1 Kazuaki Murakami1

Kazuaki Murakami1 Shigeo S. Sugano2

Shigeo S. Sugano2 Kentaro Tamura3

Kentaro Tamura3 Yoshito Oka1

Yoshito Oka1 Tomonao Matsushita1

Tomonao Matsushita1 Tomoo Shimada1*

Tomoo Shimada1*In the past two decades, many plant peptides have been found to play crucial roles in various biological events by mediating cell-to-cell communications. However, a large number of small open reading frames (sORFs) or short genes capable of encoding peptides remain uncharacterized. In this study, we examined several candidate genes for peptides conserved between two model plants: Arabidopsis thaliana and Marchantia polymorpha. We examined their expression pattern in M. polymorpha and subcellular localization using a transient assay with Nicotiana benthamiana. We found that one candidate, MpSGF10B, was expressed in meristems, gemma cups, and male reproductive organs called antheridiophores. MpSGF10B has an N-terminal signal peptide followed by two leucine-rich repeat (LRR) domains and was secreted to the extracellular region in N. benthamiana and M. polymorpha. Compared with the wild type, two independent Mpsgf10b mutants had a slightly increased number of antheridiophores. It was revealed in gene ontology enrichment analysis that MpSGF10B was significantly co-expressed with genes related to cell cycle and development. These results suggest that MpSGF10B may be involved in the reproductive development of M. polymorpha. Our research should shed light on the unknown role of LRR-only proteins in land plants.

Over the last two decades, many biologically active peptides have been identified in land plant species that play critical roles in plant growth and development through molecular genetic studies combined with biochemical analyses. Plant peptides are generally defined as less than 100 amino acids in length. Their structural characteristics can be classified into two major groups (Matsubayashi, 2014; Hirakawa et al., 2017; Stührwohldt and Schaller, 2018). One group is small post-translationally modified peptides characterized by the presence of post-translational modifications and by their small size after proteolytic processing (approximately 5–20 amino acids). The other group comprises cysteine-rich peptides (approximately 40–120 amino acids), characterized by an even number of cysteine residues forming intramolecular disulfide bonds. These plant peptides are often generated by proteolytic processing from larger precursors with N-terminal secretion signal sequences and post-translational modifications. Mature peptides generally function as extracellular ligands in cell-to-cell or long-distance signaling by interacting with their corresponding receptors, leucine-rich repeat receptor-like kinases/proteins (LRR-RLKs/RLPs), on the plasma membrane of target cells.

Since the discovery of systemin in Solanum lycopersicum (Pearce et al., 1991), several classes of small secreted peptides have been identified in land plant species. Hormone-like peptides are classified into several families, including CLAVATA3/EMBRYO SURROUNDING REGION-RELATED (CLE), INFLORESCENCE DEFICIENT IN ABSCISSION (IDA), EPIDERMAL PATTERNING FACTOR (EPF), and RAPID ALKALINIZATION FACTOR (RALF) (Gancheva et al., 2019; Furumizu et al., 2021). These peptide families and their receptors are conserved in embryophytes but are rare in green algae (Ghorbani et al., 2015; Bowman et al., 2017; Olsson et al., 2018), indicating that these peptide-signaling pathways evolved in a common ancestor of land plants and served some advantage in terrestrialization (Furumizu et al., 2018; Moody, 2019). In one example, CLE peptides and their receptors are conserved between Marchantia polymorpha and Arabidopsis thaliana and regulate the size of meristems (Fletcher et al., 1999; Hirakawa et al., 2019; Hirakawa et al., 2020). Many peptide members are encoded as multiple paralogs in most land plant species, which makes it challenging to analyze their characteristics genetically, while M. polymorpha has low redundancy in peptide families (Bowman et al., 2017; Furumizu et al., 2021). Furthermore, M. polymorpha provides a feasible system for studying small peptides reverse-genetically: for example, gateway binary vectors for M. polymorpha (Ishizaki et al., 2015), Agrobacterium-mediated transformation (Kubota et al., 2013; Tsuboyama and Kodama, 2018), and CRISPR/Cas9–based genome editing (Sugano et al., 2018).

Although the importance of bioactive peptides in plant cells has been recognized, reverse genetic analysis to search for new peptides has been difficult. This is due to the short sequence length of peptides, which is often judged as noise rather than a gene by conventional gene prediction (Hellens et al., 2016). In plants, an attempt was made to comprehensively search for small open reading frames (sORFs) that are likely to encode peptides. This was made by a powerful gene prediction method in which statistical processing based on the base composition of known protein-coding genes and the transcriptome are combined, and a high rate of false-positive prediction is overcome (Hanada et al., 2010; Hanada et al., 2013). This study identified 7,901 sORFs as candidates for new genes in A. thaliana. Among these sORFs, 49 were found to cause morphological changes when overexpressed (Hanada et al., 2013). Several databases for sORFs have recently been established (Hazarika et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2020; Liang et al., 2021). Furthermore, in the Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR) database, small coding genes of less than 120 amino acids in length have increased with version updates (Takahashi et al., 2019). These findings suggest that many functional sORFs or peptides in genomes remain uncharacterized involved in various physiological phenomena.

Here, we searched for novel peptide-coding genes conserved between land plant species and analyzed their characteristics using the high-quality dataset of A. thaliana and the feasible platform for reverse genetics of M. polymorpha.

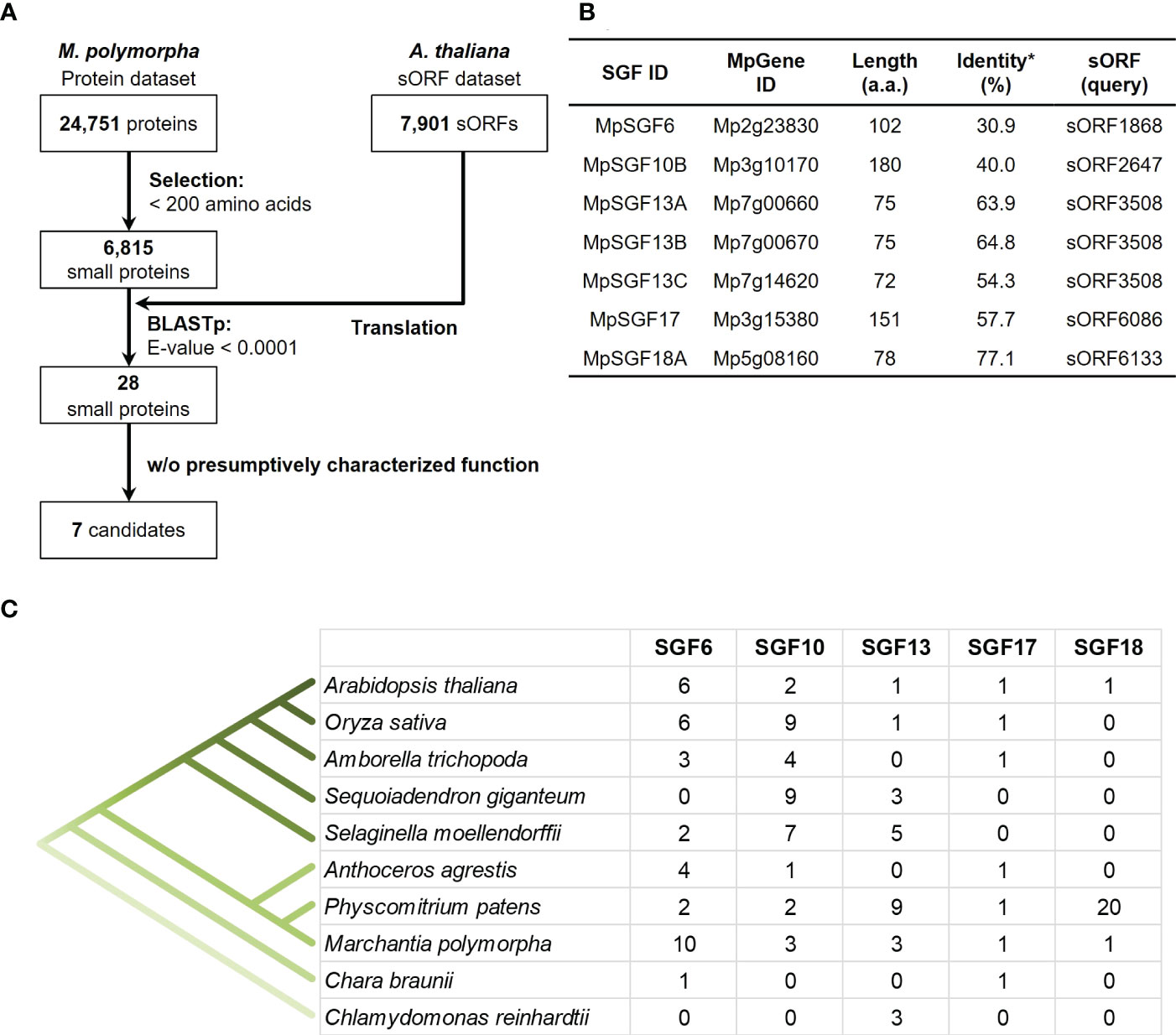

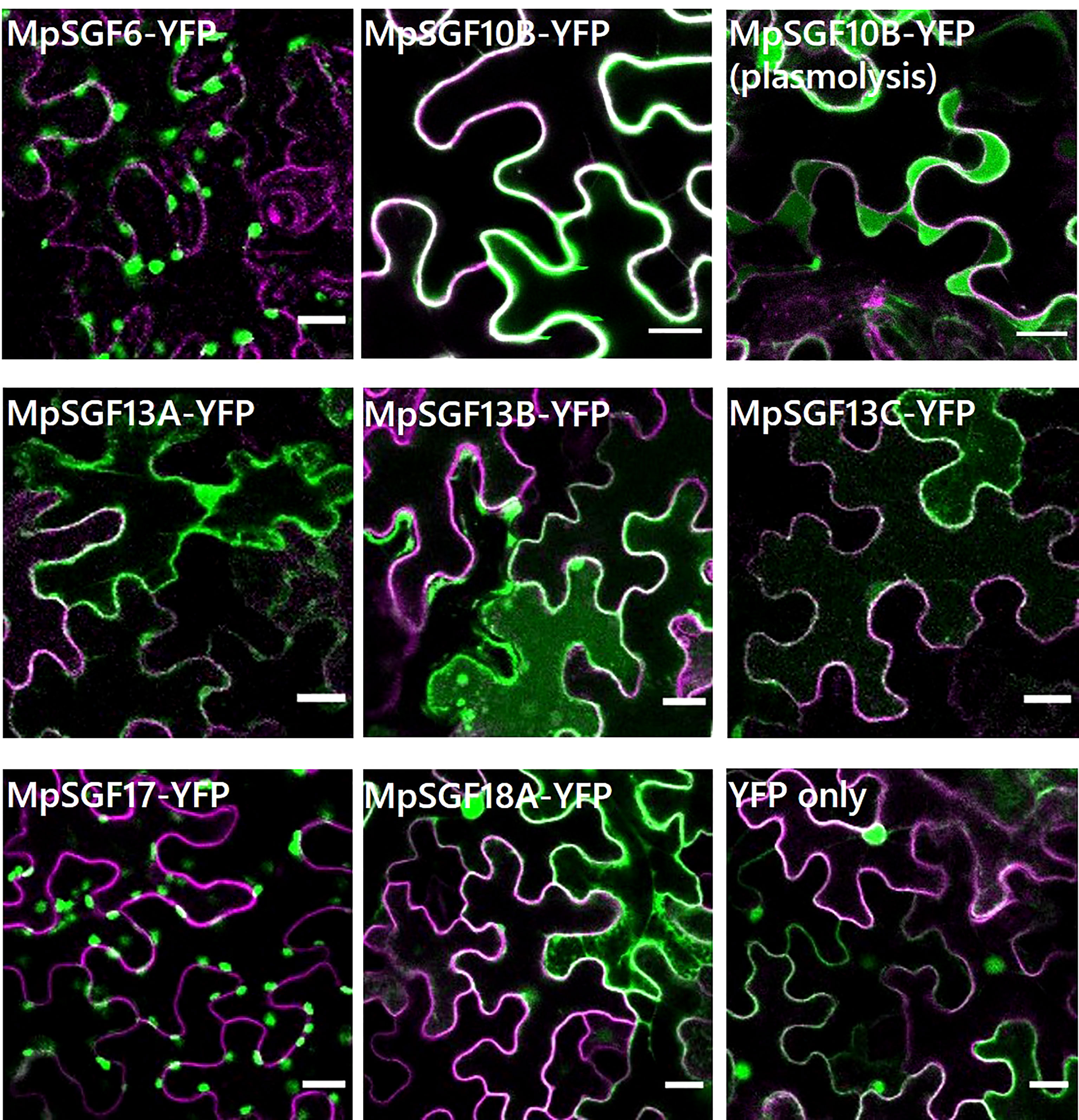

We searched genes in M. polymorpha that had high sequence similarity to sORFs in A. thaliana to find small genes that are evolutionarily conserved among land plants (datasets of the sORFs are available from https://rdr.kuleuven.be/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.48804/SP9WIK). The workflow is shown in Figure 1A. From 24,751 proteins in the M. polymorpha dataset, we first selected 6,815 small proteins with a length of < 200 amino acids. We then performed a BLASTp search using this small protein dataset as a database and the translated sORFs dataset in A. thaliana as a query. After that, we selected 28 genes in M. polymorpha encoded putative bioactive peptides (E-value < 0.0001). The search results are listed (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1). The resulting genes can be classified into 18 groups (collectively designated as “SMALL GENE FAMILIES”; SGF1–SGF18). Among these 28 genes, we focused on 7 MpSGF genes, whose functions cannot be presumed from annotations registered in MarpolBase (https://marchantia.info/; version 5), as candidates without characterized functions (Figure 1B, Table 1, and Supplementary Table S1).

Figure 1 Selection of candidates for M. polymorpha peptide-coding genes. (A) A pipeline for the selection of peptide candidates. The A. thaliana sORF dataset is used as a query for BLASTp analysis. (B) A list of selected peptide candidates in M. polymorpha. *Percentages of identity between MpSGFs and corresponding sORFs in A. thaliana are shown. (C) The number of orthologs of SGFs in land plants. Orthologous genes with the same gene family ID (ORTHO05DXXXXXX) to MpSGFs were obtained from Dicots PLAZA 5.0 (Bel et al., 2021; https://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/plaza/versions/plaza_v5_dicots/). For A. thaliana, sORF genes without AGI codes were included. For M. polymorpha, only genes in the latest database, MpTak v6.1, are shown. See Supplementary Table S3 for more details.

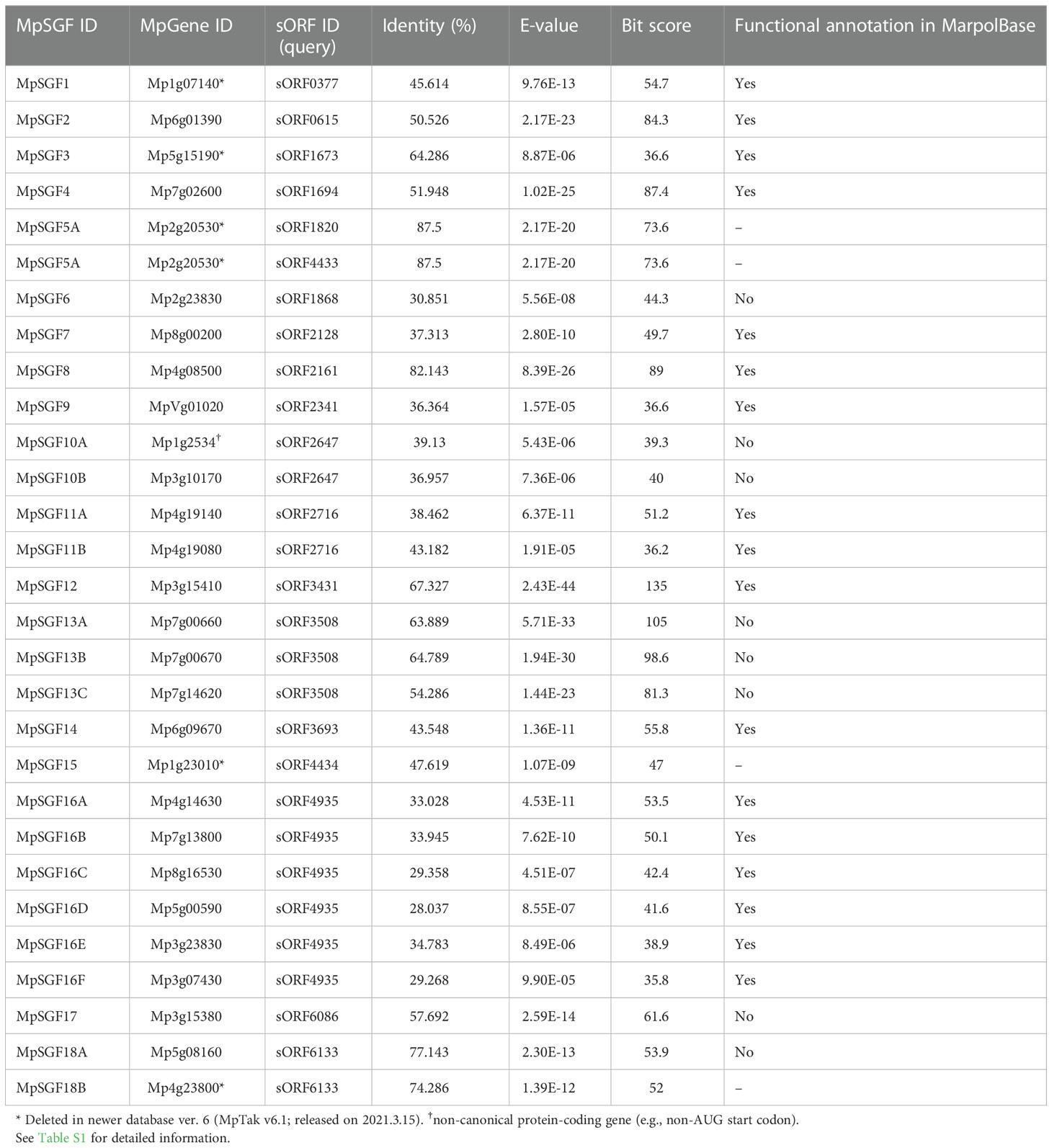

Table 1 A list of MpSGFs, containing BLAST results and annotations registered in the database (MarpolBase).

The selected seven SGF genes are well conserved among land plants, and some are found in green algae (Figure 1C). Multiple sequence alignments and molecular phylogenetic analysis were performed (Supplementary Figures S1, S2). The amino acid sequences of SGF6 and SGF10 are conserved across the entire length of the proteins in various plant species. SGF13 homologs are enriched in non-flowering plants and the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. They are conserved over the entire sequence. Some homologs have an extended N-terminus. SGF17 homologs are found from the Charophyceae Chara braunii to the flowering plants, and the C-terminal region is highly conserved. SGF18 homologs are only found in A. thaliana, M. polymorpha, and Physcomitrium patens and are highly enriched in P. patens. The middle region is well conserved among SGF18 orthologs.

Next, we examined expression pattern of the selected 7 MpSGF genes. It was revealed in reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) analyses that the expression of all MpSGF genes was detected in thalli and antheridiophores, corresponding to vegetative organs and reproductive organs, respectively. These results indicate that these MpSGFs function in both vegetative and reproductive states in M. polymorpha (Figure 2A). The results of RT-PCR were consistent with public transcriptome data (Kawamura et al., 2022). However, the expression levels of each gene varied between organs (Supplementary Figure S3).

Figure 2 Expression patterns of MpSGFs in M. polymorpha. (A) RT-PCR in 2-week-old thallus (thallus) and antheridiophore (anth.). MpEF1α is used as an internal control. MpBNB is used as a marker gene for antheridiophore (Yamaoka et al., 2018). (B) Representative images of the GUS reporter assay for expression patterns of MpSGFs. Two-week-old thalli and antheridiophores were observed for the visualization of promoter activities. Bars = 2 mm. For proMpSGF6:GUS, a magnified image around antheridia is shown in the inset, bar = 1 mm. (C) Magnified images of GUS signal in the bottom of gemma cups and apical notches of proMpSGF10B:GUS plants. Bars = 0.5 mm.

To investigate the spatial expression pattern of the selected MpSGFs in planta, we observed their promoter activities using transgenic plants harboring the ß-glucuronidase (GUS) reporter. We introduced the GUS reporter constructs with 4–5 kb upstream regions of coding sequence (CDS) into male and female wild-type plants Takaragaike-1 (Tak-1) and Takaragaike-2 (Tak-2), respectively. Two- or 3-week-old thalli and gametophores were sampled and stained as vegetative and reproductive organs, respectively (Figure 2B and Supplementary Figure S4).

The GUS activity of proMpSGF6:GUS in male plants was observed in antheridiophores, especially around antheridia, but not in thalli. In female plants, no signal was observed in thalli and archegoniophores. The GUS activity was specifically observed around apical notches, bottoms of gemma cups, and in gametophores in both male and female proMpSGF10B:GUS lines (Figure 2C). Intense GUS activities were detected in thalli and antheridiophores in male MpSGF13A and MpSGF13B plants, much weaker activity was found in whole tissues of female plants, except for the gemma cups. No GUS activity was observed in male and female proMpSGF13C:GUS lines. The GUS signal was specifically observed in antheridia and archegonia in ProMpSGF17:GUS lines. The GUS activity of proMpSGF18A:GUS lines was observed in antheridiophores, especially around antheridia, but not in thalli and archegoniophores. These observations are consistent with public transcriptome data, in which the expression level of MpSGF18A is increased in the “sperm cell” (Supplementary Figure S3).

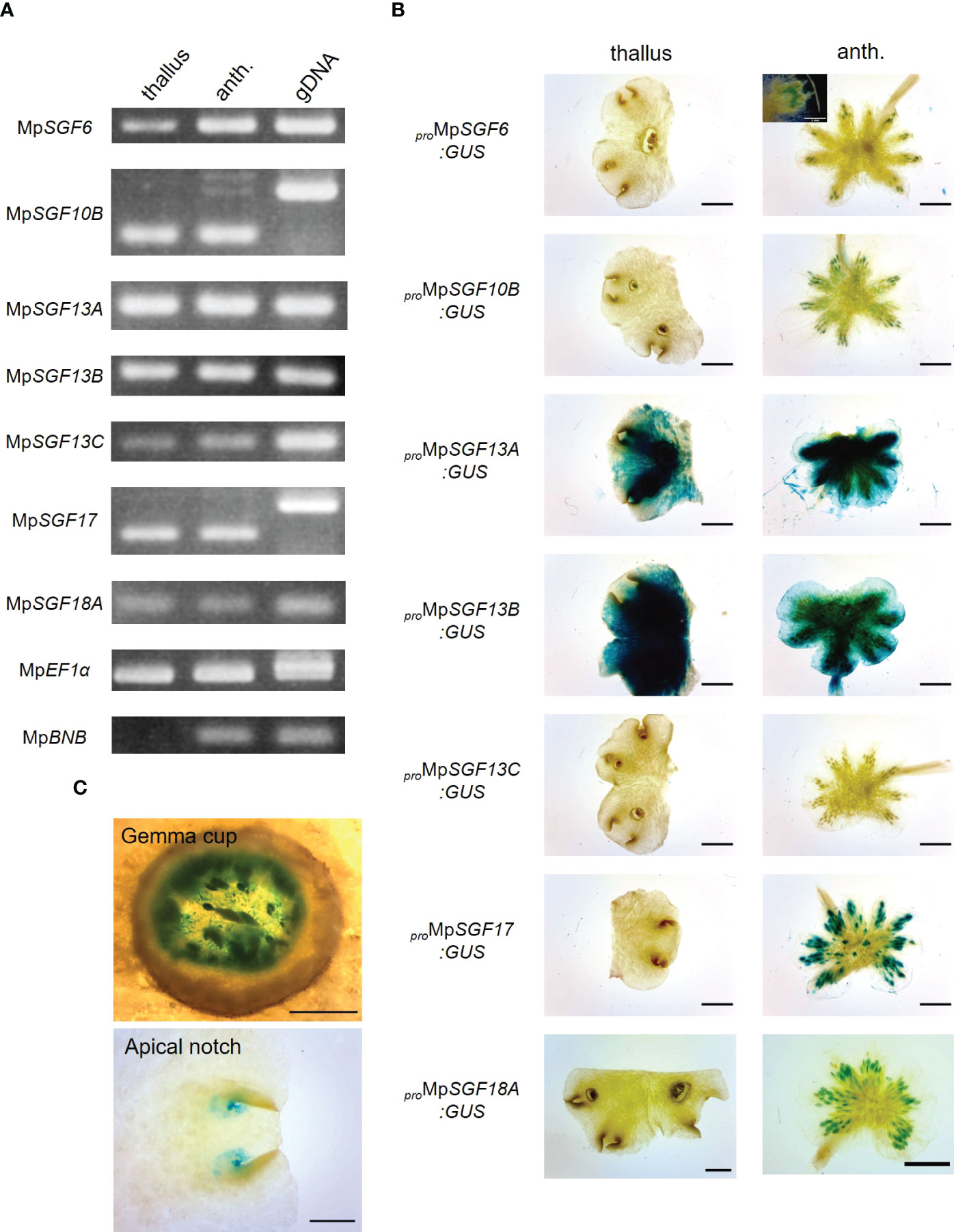

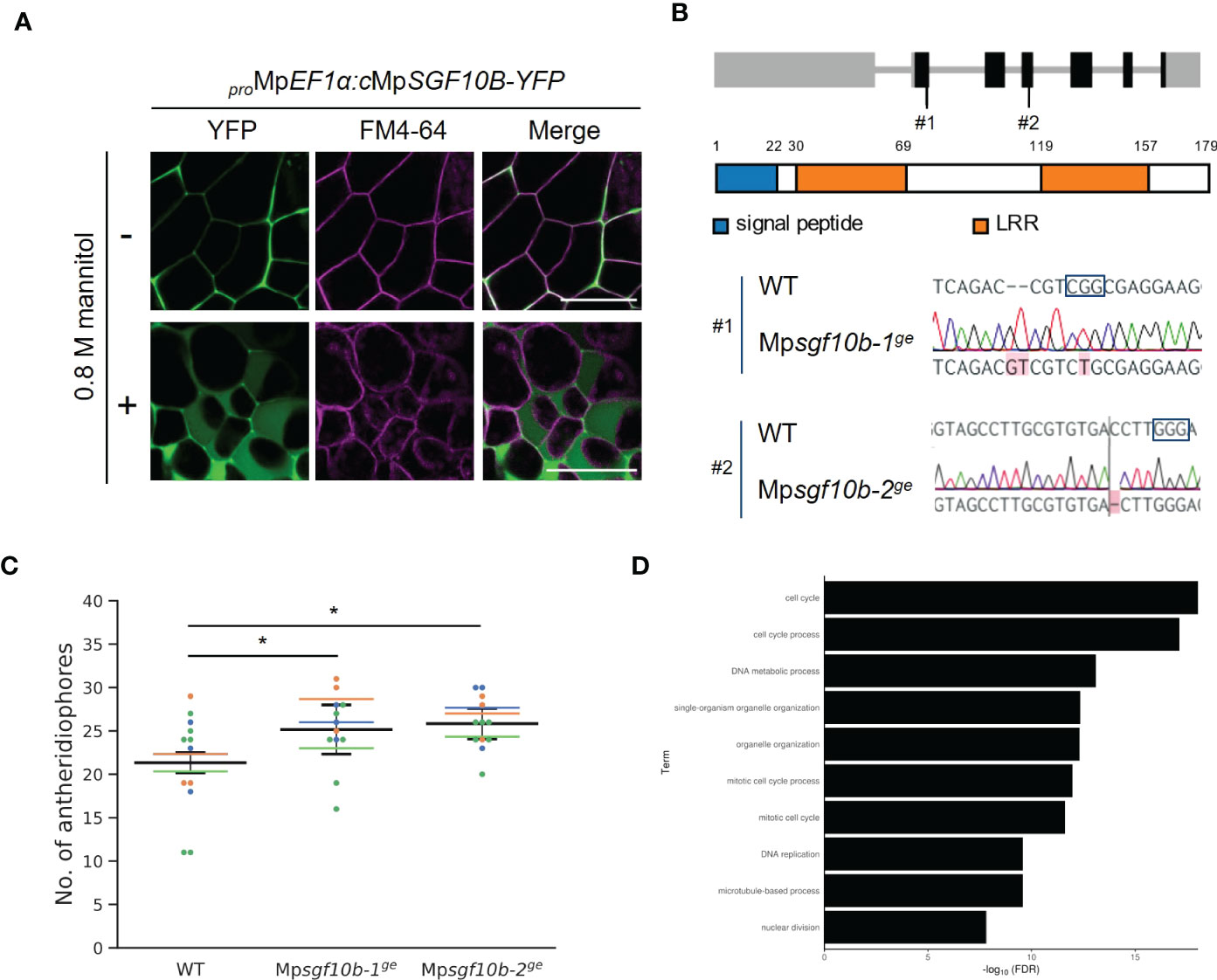

We performed a transient expression assay for a MpSGF and yellow fluorescent protein fusion proteins (MpSGF-YFP) using Nicotiana benthamiana to determine the subcellular distribution of MpSGFs (Figure 3). MpSGF6-YFP was co-localized with chlorophyll (Supplementary Figures S5A, C). While MpSGF10B-YFP was detected in the periphery of epidermal cells and appeared to overlap with the plasma membrane, the signal was visualized in an extracellular region after plasmolysis treatment, suggesting that MpSGF10B can be transported to the extracellular region. MpSGF13A-YFP, MpSGF13B-YFP, and MpSGF13C-YFP were ambiguously observed in the cytosolic compartment. MpSGF17-YFP was co-localized with chlorophyll (Supplementary Figures S5B ,D). MpSGF18A-YFP was observed in a cytosolic compartment.

Figure 3 Subcellular localization of MpSGFs in N. benthamiana. Confocal fluorescence microscopy images of MpSGF-YFP transiently expressed in N. benthamiana; MpSGF6, MpSGF10B under control (water) and hypertonic conditions, MpSGF13A, MpSGF13B, MpSGF13C, MpSGF17, MpSGF18A, and YFP only. The plasma membrane, which was visualized by mRFP-LTI6b, and YFP were shown in magenta and green, respectively. Bars = 20 µm.

We confirmed that MpSGF10B-YFP was also secreted to the extracellular region in M. polymorpha (Figure 4A). Thus, we focused on MpSGF10B as a candidate for a secreted bioactive peptide, and further analyses were performed. MpSGF10B encodes a protein with an N-terminal signal peptide, followed by two LRR motifs (Figure 4B). We generated Mpsgf10bge mutants using the CRISPR/Cas9 system to examine the function of the MpSGF10B in M. polymorpha. Mpsgf10b-1ge and Mpsgf10b-2ge harbor frameshift mutations that generate early stop codons after the predicted signal peptide sequence and in the middle of the sequence, respectively (Figure 4B). In the vegetative growth phase, 2-week-old Mpsgf10bge mutants showed no significant differences in thallus size and the number of apical notches compared to the wild type (Supplementary Figure S6). However, in the subsequent reproductive phase, we found that the number of antheridiophore was slightly increased in both Mpsgf10bge mutants after 3-week induction (Figure 4C). It is suggested in these results that MpSGF10B might function in the reproductive phase in the liverwort.

Figure 4 Reverse genetic analysis of MpSGF10B. (A) Subcellular localization of MpSGF10B-YFP constitutively expressed in M. polymorpha. Three-day-old gemmalings were observed. The plasma membrane was visualized with FM4-64 (magenta). Shown data are representative ones from 5 independent transgenic lines. Bars = 50 µm. (B) Gene structures and genotypes of Mpsgf10b mutants using CRISPR/Cas9. (top) Structure of MpSGF10B/Mp3g10170 locus with the positions of the designed guide RNAs (#1 and #2). Black boxes, gray lines, and gray boxes show coding exons, introns, and untranslated regions. (Middle) The predicted product of MpSGF10B is shown. (Lower) Sequences of genome editing alleles are shown. The PAM sequence is shown in enclosed characters. Edited bases are indicated with red shades. (C) The number of antheridiophores in an individual plant. n = 3, 3, and 5 for all lines from three independent experiments, respectively (indicated in distinct colors). Horizontal lines indicate the average numbers grouped by the experiments. Black lines show the total means ± SD. *P < 0.05, Dunnett’s test against wild type (WT). (D) GO enrichment analysis of highly co-expressed genes with MpSGF10B. The 10 high-ranking biological processes are shown at a 1% false discovery rate (FDR).

We investigated the effect of MpSGF10B mutations on reproductive growth by putting gemmae under reproductive conditions. After 10-day induction, no apparent abnormalities were observed in the branching frequency of thalli and emerging time of gametangiophores in Mpsgf10b mutants (Supplementary Figure S7). Under the same reproductive condition, the overexpression lines of MpSGF10B-YFP developed slightly fewer antheridiophores than the wild type. Still, there was no statistically significant difference (Supplementary Figure S8).

Next, we examined the functional categories of co-expressed genes with MpSGF10B by gene ontology (GO) to infer the functional categories of MpSGF10B at the molecular level. We calculated the R-values (Pearson’s coefficient of correlation) of expression intensities between MpSGF10B and all annotated genes in various organs and conditions. We then defined those annotated genes with the 1% high-ranking R-values as co-expressed genes (Hanada et al., 2013). The over-represented functions of the co-expressed genes were related to cell cycle and development at lower FDR values among the GO categories of biological processes (Figure 4D and Supplementary Table S2). This was consistent with the above-mentioned reporter assay, since the promoter activity of MpSGF10B was detected around the apice and the bottom of gemma cups, in which cell division was taking place for the growth and production of gemmae, respectively (Figure 2C). Collectively, these data suggest that MpSGF10B may be related to cell cycle or cell division at the molecular level.

Since the promoter activity of MpSGF10B was observed in gemma cups and around apical notches (Figure 2C), in which auxin-regulated genes are highly expressed (Ishizaki et al., 2012), we presumed that MpSGF10B could be involved in auxin signaling. However, the expression levels of two auxin-responsive genes, MpWIP and MpEXP (Kato et al., 2017), were not altered in Mpsgf10bge mutants compared to the wild type (Supplementary Figure S9). Furthermore, the expression level of MpSGF10B was also unchanged by auxin dosage according to public transcriptome analyses (Supplementary Figure S3). Thus, its contribution to auxin signaling might be little or null.

Over the past few decades, various peptide-coding genes have been predicted in A. thaliana (Hanada et al., 2007; Hanada et al., 2013). Since many bioactive peptides tend to be conserved among land plant species, it is reasonable that bioactive peptides can be detected by comparing evolutionally distant plant species (e.g., bryophytes and flowering plants). We investigated novel peptide-coding genes conserved between A. thaliana and M. polymorpha through a BLAST-based similarity search followed by expression analyses in this study.

It was revealed in our phylogenetic analyses that the selected SGFs, except for SGF18, were conserved in various land plant species (Figure 1C; Supplementary Figures S1, S2). It was suggested in previous analyses that peptide-coding genes have low redundancy in bryophytes and high copy numbers in vascular plants (Bowman et al., 2017; Olsson et al., 2018; Furumizu et al., 2021). However, we found that orthologous genes of SGF13 and SGF17 were mainly enriched in bryophytes. One possibility is that SGF13 and SGF17 gene families might be more adaptive in the life cycle of bryophytes. Another possibility is that many peptide-coding genes remained unannotated even in the latest database of A. thaliana (Takahashi et al., 2019; Fan et al., 2022). Recently, comprehensive studies have been performed to identify novel functional peptides in land plants (Fesenko et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2020; Liang et al., 2021). Annotations of small peptide-coding genes will be expanded by these analyses in the future. Thus, SGFs classified in this study can be more conserved in land plant species than we reported here.

Bioactive peptides in plants are generally secreted out of cells and function as extracellular ligands in cell-to-cell signaling by interacting with their corresponding receptors on the plasma membrane of target cells. MpSGF10B possessed an N-terminal signal peptide and was secreted into the extracellular region (Figures 3B, C, 4A). However, an N-terminal signal peptide is not necessary to act as an apoplastic signaling ligand. For example, AtPROPEP1 is localized in the cytosolic compartment before maturation, and its mature form, AtPep1, is generated upon tissue damage and released into the apoplast region (Hander et al., 2019). Therefore, the possibility remains that the other MpSGFs, such as cytosolic MpSGF13A, MpSGF13B, MpSGF13C, and MpSGF18A, function as signaling ligands extracellularly in some cases.

We showed that the LRR-containing protein MpSGF10B was secreted to the extracellular region in this study (Figures 3B, C). LRR proteins in plants act in various biological processes. According to the subcellular localization and structure, LRR proteins are classified into three groups: LRR-RLKs/RLPs at the plasma membrane, intracellular nucleotide-binding site (NBS)-LRRs, and extracellular LRR-only proteins (Wang et al., 2011). MpSGF10B may belong to the extracellular LRR-only protein group.

LRR-RLKs/RLPs and NBS-LRRs have been well studied and act in plant immune responses, such as various receptors and R-genes (Dievart et al., 2020; Sett et al., 2022). In contrast, extracellular LRR-only proteins have been poorly reported. A well-known LRR-only protein, polygalacturonase inhibitor 1 (PGIP1), participates in disease resistance by inhibiting the activity of fungal pectin-degrading enzymes (Cheng et al., 2021). Arabidopsis PGIPs have an N-terminal signal peptide and LRR motifs (PGIP1: Q9M5J9, PGIP2: Q9M5J8 in the UniProt database). Therefore, PGIPs and MpSGF10B have similar features. However, there are some differences between MpSGF10B and rice PGIPs, which are anchored to the plasma membrane or cell wall (Wang et al., 2015) and possess as many as 10 repeats of the LRR motif. It is reported that canonical LRR-only proteins contained 7–13 repeats (Wang et al., 2011). Since MpSGF10B has fewer LRR motifs and is smaller than canonical LRR proteins, it can be considered a non-canonical LRR-only protein (Figure 4B). As such non-canonical LRR-only proteins, NTCD4 (F4JNB0 in the UniProt) and LRRop-1 (Q9FPJ5), have been reported in A. thaliana. NTCD4 consists of 153 amino acids and interacts with MoNLP1, a microbe-associated molecular pattern, to induce cell death. NTCD4 is secreted in the extracellular region (Chen et al., 2021). LRRop-1, an LRR-only protein of 218 amino acids, has been suggested to contribute to ABA signaling and is localized in the ER (Ravindran et al., 2020).

Several repeats of LRR motifs, which are generally involved in protein-protein interaction, form a twisted super-helical or a small arc-shaped structure (Kobe and Kajava, 2001; Chakraborty et al., 2019). Therefore, it is unlikely that a small number of LRR units can function as canonical receptors. Further studies are necessary to verify the molecular function of MpSGF10B, whether it acts as a coreceptor that assists other receptors or a ligand for signal transduction or serves an entirely different function.

We found promoter activity of MpSGF10B in the following organs in M. polymorpha: bottom of gemma cups, surrounding areas of the meristem, and antheridia (Figures 2B, C). These expression patterns seem to overlap largely with the accumulation patterns of auxin (Ishizaki et al., 2012). Auxin is proposed to control the development of various organs in M. polymorpha, including gemmae formation and the branching frequency of thalli (Kato et al., 2020), through regulating the expression pattern of auxin-responsive genes. However, the expression levels of two auxin-responsive genes were not altered in the Mpsgf10b mutants (Supplementary Figure S9). Consistently, the Mpsgf10b mutants did not show any phenotypic changes, which were expected when perturbing the auxin signal (Supplementary Figure S7). Furthermore, the expression of MpSGF10B is likely independent of the auxin signal (Supplementary Figure S3). Thus, MpSGF10B may function independently of or weakly associated with auxin signaling.

Here, we reported that MpSGF10B might be involved in the induction of reproductive organs in M. polymorpha (Figure 4C and Supplementary Figures S8). In reproductive induction in liverworts, far-red light and circadian rhythms of long-day are key conditions, and these environmental stimuli are sensed and transduced by various signaling genes including MpBNB, which acts as a master regulator of reproductive development (Kohchi et al., 2021; Yamaoka et al., 2021). Homologous modules are involved in light response and gametogenesis in A. thaliana, suggesting the conserved roles of these signaling modules among land plant species (Kohchi et al., 2021; Yamaoka et al., 2021). In this study, we found that relevant orthologs of MpSGF10B are conserved in land plant species but not in algae (Figure 1C and Supplementary Figures S1, S2). Unfortunately, this time we could not come close to a clear function of MpSGF10. Further analyses are needed to determine the physiological function of MpSGF10B and its orthologs in M. polymorpha and other plant species.

M. polymorpha male and female accessions, Tak-1 and Tak-2, respectively, were used as the wild type in this study. Plants were axenically grown on half-strength Gamborg’s B5 medium pH 5.7 containing 1% agar and 1% sucrose at 22°C under 50–60 μmol photons m−2 s−1 continuous white light. For reproductive induction, plants were incubated under long-day conditions (light: 16 h, dark: 8 h) supplemented with continuous far-red light at 18°C emitted from diodes (IR LED STICK 18W, Namoto).

The sequences of orthologous genes, which were assigned the same ortholog IDs as the MpSGFs, were retrieved from dicots PLAZA 5.0 (Supplementary Table S3). Briefly, SGF6, SGF10, SGF13, SGF17, and SGF18 correspond to ORTHO05D000774,ORTHO05D001118, ORTHO05D007973, ORTHO05D009227, and ORTHO05D009796, respectively. Multiple sequence alignments were performed using stand-alone MAFFT (v7.490) with the L-INS-i method. The alignments were visualized using the LATEX package, TEXshade. The alignment gaps were removed using TrimAl (v1.4) with the “-automated1” method. Substitution models were evaluated with ModelTest-NG (v0.1.6). Phylogenetic trees were generated using RAxML-NG (v0.9.0), with the substitution models of JTT+G4m, LG+I+G4m, LG+G4m, LG+I+G4m, and JTT+I were used for SGF6, SGF10, SGF13, SGF17, and SGF18, respectively. We performed bootstrap analyses with 1,000 replicates for each analysis to assess the statistical support for the topology.

Thalli or antheridiophores frozen in liquid nitrogen were ground with a mortar and a pestle into fine powder. Total RNA was extracted from the tissue powder using the RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen). cDNA was synthesized using ReverTra Ace reverse transcriptase (Toyobo). Amplification was performed with GoTaq DNA polymerase (Promega).

Primers used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table S4. For the promoter GUS constructs, approximately 5,000 bp upstream sequences flanked the start codons of the MpSGFs were amplified from Tak-1 genomic DNA using PrimeSTAR GXL polymerase (Takara Bio) and cloned into a linearized pENTR1A vector using In-fusion (Takara Bio). Inserts were transferred into pMpGWB104 vectors (Ishizaki et al., 2015) using a Gateway LR Clonase II enzyme mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific). For the construction of the transient expression assay, total RNA was extracted from Tak-1 thalli, and cDNA was synthesized. The CDSs of the MpSGFs were amplified from the cDNA using PrimeSTAR GXL polymerase. A DNA fragment of modified Venus (YFP-4×Gly), the fluorescent protein with four Gly-residues at its C-terminus, was amplified from the gateway vector used previously (Sugano et al., 2010). Three fragments of a MpSGF CDS, a YFP-4×Gly CDS, and a linearized pENTR1A backbone were fused using In-fusion. The entry vector was transferred to a binary vector, pGWB602 (Nakamura et al., 2010), with a Gateway LR Clonase II enzyme mix. A genomic fragment of Arabidopsis LTI6b was amplified and fused with pENTR1A using In-fusion and transferred to pGWB655 with a Gateway LR Clonase II enzyme mix to construct mRFP-LTI6b. For the constitutive expression of MpSGF10B-YFP in Marchantia, the MpSGF10B-YFP in pENTR1A mentioned above was used as an entry vector. The entry vector was transferred to a binary vector pMpGWB103 (Ishizaki et al., 2015) with a Gateway LR Clonase II enzyme mix. For genome editing, guide RNAs were designed at two positions for each target gene using the CRISPR-Cas9 system (Sugano et al., 2018). Double-stranded DNAs corresponding to the guide RNA sequences were generated and inserted into AarI-digested pMpGE013 by ligation reaction using Mighty Mix (Takara Bio).

M. polymorpha transformants were obtained by Agrobacterium-mediated transformation from regenerating thalli using the AgarTrap method (Tsuboyama and Kodama, 2018). Two wild-type accessions, Tak-1 (male) and Tak-2 (female), were used as genetic backgrounds. Transgenic plants were selected with the above-mentioned medium and were supplemented with 10 µg/mL hygromycin. The transformants were clonally purified through gemmae generations. To examine the target loci of genome editing lines, genomic DNAs were extracted from G1-generation plants produced from the asexual reproduction of T1 plants, and then the PCR products were amplified using GoTaq DNA polymerase, followed by direct sequencing (Sugano and Nishihama, 2018).

Transgenic plants were fixed with 90% acetone at 4°C and then stained in GUS staining solution (100 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.4, 0.5 mM potassium ferrocyanide, 0.5 mM potassium ferricyanide, 10 mM EDTA, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 0.5 mg/ml 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-b-D-glucuronic acid) overnight at 37°C in the dark for GUS staining. The GUS-stained samples were cleared with 70% ethanol and chloral hydrate solution.

The Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101 strain was transformed with plasmids harboring proteins of interest (POIs) and grown in LB media containing spectinomycin (50 µg/mL). Cultures grown for about 24 h at 28°C with rotation at 220 rpm were used to transform N. benthamiana leaves. POI-containing bacteria were centrifuged for 15 min at 2,800 × g and resuspended in water to 4-fold dilution for infiltration. The cells were infiltrated into the abaxial side of N. benthamiana leaves. The infiltrated plants were incubated under dark conditions for 2 days. For imaging, the leaves were infiltrated with water (control) or 0.8 M D-mannitol solution (plasmolysis) using a 1 mL syringe, and leaf disks were harvested immediately.

The fluorescent images were inspected under a confocal laser scanning microscope (LSM780; Zeiss) using a 514- or 561-nm laser line. We used filter sets of a 519/549 nm band-pass filter for YFP fluorescence, a 583/633 nm for mRFP, and a 571/645 nm for FM4-64. Fresh samples were mounted in water (control) or 0.8 M D-mannitol solution (plasmolysis) and imaged immediately. For gemmalings, the plasma membrane was stained with 10 µg/ml FM4-64 (Invitrogen). These channel images were processed using ImageJ (Fiji; Schindelin et al., 2012).

Growth phenotypes were monitored in plants after reproductive induction for 10–30 days under long-day conditions (light: 16 h, dark: 8 h) supplemented with continuous far-red light at 18°C with or without preculture for two weeks at 22°C under continuous white light. According to the developmental stages of antheridiophores (Higo et al., 2016), antheridiophores of above stage 1, namely “button-like” receptacles, were counted. The number of branches was calculated based on the trajectory of antheridiophores and apical notches in time-lapse images. Apical notches were defined as notches without gametangiophores. The area of thalli was measured with the “color threshold” tool of ImageJ.

Publicly available fastq data from RNA-Seq libraries were obtained from the sequence read archive in NCBI. All libraries used for analyses were performed in triplicate (except for antheridia duplicates). Fastq sequence data were mapped onto the reference genome of M. polymorpha (version 6.1) using STAR (Dobin et al., 2013), and the number of fragments was counted and normalized by transcripts per million (TPM) with RSEM (Li and Dewey, 2011). Accession numbers include: 11-day thalli (DRR050343, DRR050344, and DRR050345), Archegoniophore (DRR050351, DRR050352, and DRR050353), Antheridiophore (DRR050346, DRR050347, and DRR050348), Antheridia (DRR050349, and DRR050350), apical cell (SRR1553294, SRR1553295, and SRR1553296), 13d-Sporophyte (SRR1553297, SRR1553298, and SRR1553299), Sporelings 0 h (SRR4450262, SRR4450261, and SRR4450260), 24hr-Sporeling (SRR4450266, SRR4450265, and SRR4450259), 48hr-Sporeling (SRR4450268, SRR4450264, and SRR4450263), 72hr-Sporeling (SRR4450267, SRR4450258, and SRR4450257), 96hr-Sporeling (SRR4450256, SRR4450255, and SRR4450254), thalli-mock (SRR5905100, SRR5905099, and SRR5905098), and 2,4-D 1h (SRR5905097, SRR5905092, and SRR5905091), plants infected with P. palmivora of 2 dpi (SRR7977547, SRR7977549, and SRR7977550), and mock-inoculated plants of 2 dpi (SRR8068335, SRR8068336, and SRR8068340) (Carella et al., 2018; Flores-Sandoval et al., 2018). Pearson’s correlation coefficients (PCCs) were calculated for the TPM of MpSGF10B and all genes using the R application. The top 1% (182 genes) with high PCC values were selected as co-expressed genes with MpSGF10B. These gene IDs were converted to those in assembly version 3 using the “convert ID” tool in MarpolBase (https://marchantia.info/). Then, GO enrichment analysis was performed using the Plant Transcriptional Regulatory Map (PlantRegMap, http://plantregmap.gao-lab.org/).

Statistical analyses were performed in R version 4.0.3. One-way ANOVA and one-tailed Dunnett’s test in package “multicomp” were used for multiple comparisons of means grouped by technical replicates.

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

HK and TS conceived and designed the research in general; HK performed most of the experiments and analyzed the data; KM generated a construct for visualizing plasma membranes; SSS supported data analysis; KT, YO, and TM supervised the experiments; HK and TS wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by MEXT/JSPS KAKENHI grants to KT (JP22K06269 and JP18K06283), YO (JP18K19964), TM (JP20H05905 and JP20H05906), and TS (JP18K06284 and JP22K19309); Human Frontier Science Program (RGP009/2018) to KT.

We thank our colleagues for their technical assistance, especially Kenta C. Moriya (Kyoto University, Japan), for culturing M. polymorpha and inducing reproductive organs. We also thank Tsuyoshi Nakagawa (Shimane University, Japan) and Shoji Mano (National Institute for Basic Biology, Japan) for sharing the vectors. The authors thank Enago (www.enago.jp) for the English language review.

The reviewer SY declared a shared affiliation and a past co-authorship with several of the authors HK, KT, YO, TM, TS to the handling editor at the time of review.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2022.1051017/full#supplementary-material

Bel, M. V., Silvestri, F., Weitz, E. M., Kreft, L., Botzki, A., Coppens, F., et al. (2021). PLAZA 5.0: extending the scope and power of comparative and functional genomics in plants. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, D1468–D1474. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab1024

Bowman, J. L., Kohchi, T., Yamato, K. T., Jenkins, J., Shu, S., Ishizaki, K., et al. (2017). Insights into land plant evolution garnered from the Marchantia polymorpha genome. Cell 171, 287–304.e15. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.030

Carella, P., Gogleva, A., Tomaselli, M., Alfs, C., Schornack, S. (2018). Phytophthora palmivora establishes tissue-specific intracellular infection structures in the earliest divergent land plant lineage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, E3846–E3855. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1717900115

Chakraborty, S., Nguyen, B., Wasti, S. D., Xu, G. (2019). Plant leucine-rich repeat receptor kinase (LRR-RK): Structure, ligand perception, and activation mechanism. Molecules 24, 3081. doi: 10.3390/molecules24173081

Chen, J. B., Bao, S. W., Fang, Y. L., Wei, L. Y., Zhu, W. S., Peng, Y. L., et al. (2021). An LRR-only protein promotes NLP-triggered cell death and disease susceptibility by facilitating oligomerization of NLP in arabidopsis. New Phytol. 232, 1808–1822. doi: 10.1111/nph.17680

Cheng, S., Li, R., Lin, L., Shi, H., Liu, X., Yu, C. (2021). Recent advances in understanding the function of the PGIP gene and the research of its proteins for the disease resistance of plants. Appl. Sci. 11, 11123. doi: 10.3390/app112311123

Chen, Y., Li, D., Fan, W., Zheng, X., Zhou, Y., Ye, H., et al. (2020). PsORF: a database of small ORFs in plants. Plant Biotechnol. J. 18, 2158–2160. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13389

Dievart, A., Gottin, C., Périn, C., Ranwez, V., Chantret, N. (2020). Origin and diversity of plant receptor-like kinases. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 71, 1–26. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-073019-025927

Dobin, A., Davis, C. A., Schlesinger, F., Drenkow, J., Zaleski, C., Jha, S., et al. (2013). STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635

Fan, K. T., Hsu, C. W., Chen, Y. R. (2022). Mass spectrometry in the discovery of peptides involved in intercellular communication: From targeted to untargeted peptidomics approaches. Mass Spectrom. Rev., e21789. doi: 10.1002/mas.21789

Fesenko, I., Kirov, I., Kniazev, A., Khazigaleeva, R., Lazarev, V., Kharlampieva, D., et al. (2019). Distinct types of short open reading frames are translated in plant cells. Genome Res. 29, 1464–1477. doi: 10.1101/gr.253302.119

Fletcher, J. C., Brand, U., Running, M. P., Simon, R., Meyerowitz, E. M. (1999). Signaling of cell fate decisions by CLAVATA3 in arabidopsis shoot meristems. Science 283, 1911–1914. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5409.1911

Flores-Sandoval, E., Romani, F., Bowman, J. L. (2018). Co-Expression and transcriptome analysis of Marchantia polymorpha transcription factors supports class c ARFs as independent actors of an ancient auxin regulatory module. Front. Plant Sci. 91345. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01345

Furumizu, C., Hirakawa, Y., Bowman, J. L., Sawa, S. (2018). 3D body evolution: Adding a new dimension to colonize the land. Curr. Biol. 28, R838–R840. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.06.040

Furumizu, C., Krabberød, A. K., Hammerstad, M., Alling, R. M., Wildhagen, M., Sawa, S., et al. (2021). The sequenced genomes of non-flowering land plants reveal the innovative evolutionary history of peptide signaling. Plant Cell 33, koab173–. doi: 10.1093/plcell/koab173

Gancheva, M. S., Yu., V., Poliushkevich, L. O., Dodueva, I. E., Lutova, L. A. (2019). Plant peptide hormones. Russ. J. Plant Physl. 66, 171–189. doi: 10.1134/s1021443719010072

Ghorbani, S., Lin, Y. C., Parizot, B., Fernandez, A., Njo, M. F., de Peer, Y. V., et al. (2015). Expanding the repertoire of secretory peptides controlling root development with comparative genome analysis and functional assays. J. Exp. Bot. 66, 5257–5269. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erv346

Hanada, K., Akiyama, K., Sakurai, T., Toyoda, T., Shinozaki, K., Shiu, S. H. (2010). sORF finder: a program package to identify small open reading frames with high coding potential. Bioinformatics 26, 399–400. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp688

Hanada, K., Higuchi-Takeuchi, M., Okamoto, M., Yoshizumi, T., Shimizu, M., Nakaminami, K., et al. (2013). Small open reading frames associated with morphogenesis are hidden in plant genomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 2395–2400. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213958110

Hanada, K., Zhang, X., Borevitz, J. O., Li, W. H., Shiu, S. H. (2007). A large number of novel coding small open reading frames in the intergenic regions of the Arabidopsis thaliana genome are transcribed and/or under purifying selection. Genome Res. 17, 632–640. doi: 10.1101/gr.5836207

Hander, T., Fernández-Fernández, Á.D., Kumpf, R. P., Willems, P., Schatowitz, H., Rombaut, D., et al. (2019). Damage on plants activates Ca2+-dependent metacaspases for release of immunomodulatory peptides. Science 363, eaar7486. doi: 10.1126/science.aar7486

Hazarika, R. R., Coninck, B. D., Yamamoto, L. R., Martin, L. R., Cammue, B. P. A., Noort, V.v. (2017). ARA-PEPs: a repository of putative sORF-encoded peptides in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Bioinf. 18, 37. doi: 10.1186/s12859-016-1458-y

Hellens, R. P., Brown, C. M., Chisnall, M. A. W., Waterhouse, P. M., Macknight, R. C. (2016). The emerging world of small ORFs. Trends Plant Sci. 21, 317–328. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2015.11.005

Higo, A., Niwa, M., Yamato, K. T., Yamada, L., Sawada, H., Sakamoto, T., et al. (2016). Transcriptional framework of Male gametogenesis in the liverwort marchantia polymorpha l. Plant Cell Physiol. 57, 325–338. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcw005

Hirakawa, Y., Fujimoto, T., Ishida, S., Uchida, N., Sawa, S., Kiyosue, T., et al. (2020). Induction of multichotomous branching by CLAVATA peptide in Marchantia polymorpha. Curr. Biol. 30, 3833–3840.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.07.016

Hirakawa, Y., Torii, K. U., Uchida, N. (2017). Mechanisms and strategies shaping plant peptide hormones. Plant Cell Physiol. 58, 1313–1318. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcx069

Hirakawa, Y., Uchida, N., Yamaguchi, Y. L., Tabata, R., Ishida, S., Ishizaki, K., et al. (2019). Control of proliferation in the haploid meristem by CLE peptide signaling in Marchantia polymorpha. PloS Genet. 15, e1007997. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007997

Ishizaki, K., Nishihama, R., Ueda, M., Inoue, K., Ishida, S., Nishimura, Y., et al. (2015). Development of gateway binary vector series with four different selection markers for the liverwort Marchantia polymorpha. PloS One 10, e0138876. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138876

Ishizaki, K., Nonomura, M., Kato, H., Yamato, K. T., Kohchi, T. (2012). Visualization of auxin-mediated transcriptional activation using a common auxin-responsive reporter system in the liverwort Marchantia polymorpha. J. Plant Res. 125, 643–651. doi: 10.1007/s10265-012-0477-7

Kato, H., Kouno, M., Takeda, M., Suzuki, H., Ishizaki, K., Nishihama, R., et al. (2017). The roles of the sole activator-type auxin response factor in pattern formation of marchantia polymorpha. Plant Cell Physiol. 58, 1642–1651. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcx095

Kato, H., Yasui, Y., Ishizaki, K. (2020). Gemma cup and gemma development in Marchantia polymorpha. New Phytol. 228, 459–465. doi: 10.1111/nph.16655

Kawamura, S., Romani, F., Yagura, M., Mochizuki, T., Sakamoto, M., Yamaoka, S., et al. (2022). MarpolBase expression: A web-based, comprehensive platform for visualization and analysis of transcriptomes in the liverwort marchantia polymorpha. Plant Cell Physiol 63, 1745–1755. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcac129

Kobe, B., Kajava, A.V (2001). The leucine-rich repeat as a protein recognition motif. Curr. Opin. Struc. Biol. 11, 725–732. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(01)00266-4

Kohchi, T., Yamato, K. T., Ishizaki, K., Yamaoka, S., Nishihama, R. (2021). Development and molecular genetics of Marchantia polymorpha. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 72, 1–26. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-082520-094256

Kubota, A., Ishizaki, K., Hosaka, M., Kohchi, T. (2013). Efficient Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of the liverwort Marchantia polymorpha using regenerating thalli. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 77, 167–172. doi: 10.1271/bbb.120700

Liang, Y., Zhu, W., Chen, S., Qian, J., Li, L. (2021). Genome-wide identification and characterization of small peptides in maize. Front. Plant Sci. 12. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.695439

Li, B., Dewey, C. N. (2011). RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinf. 12, 323. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-323

Matsubayashi, Y. (2014). Posttranslationally modified small-peptide signals in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 65, 385–413. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050312-120122

Moody, L. A. (2019). The 2D to 3D growth transition in the moss Physcomitrella patens. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 47, 88–95. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2018.10.001

Nakamura, S., Mano, S., Tanaka, Y., Ohnishi, M., Nakamori, C., Araki, M., et al. (2010). Gateway binary vectors with the bialaphos resistance gene, bar, as a selection marker for plant transformation. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 74, 1315–1319. doi: 10.1271/bbb.100184

Olsson, V., Joos, L., Zhu, S., Gevaert, K., Butenko, M. A., Smet, I. D. (2018). Look closely, the beautiful may be small: Precursor-derived peptides in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 70, 1–34. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042817-040413

Pearce, G., Strydom, D., Johnson, S., Ryan, C. A. (1991). A polypeptide from tomato leaves induces wound-inducible proteinase inhibitor proteins. Science 253, 895–897. doi: 10.1126/science.253.5022.895

Ravindran, P., Yong, S. Y., Mohanty, B., Kumar, P. P. (2020). An LRR-only protein regulates abscisic acid-mediated abiotic stress responses during Arabidopsis seed germination. Plant Cell Rep. 39, 909–920. doi: 10.1007/s00299-020-02538-8

Schindelin, J., Arganda-Carreras, I., Frise, E., Kaynig, V., Longair, M., Pietzsch, T., et al. (2012). Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019

Sett, S., Prasad, A., Prasad, M. (2022). Resistance genes on the verge of plant–virus interaction. Trends Plant Sci. 27, 1242–1252. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2022.07.003

Stührwohldt, N., Schaller, A. (2018). Regulation of plant peptide hormones and growth factors by post-translational modification. Plant Biol. 21, 49–63. doi: 10.1111/plb.12881

Sugano, S. S., Nishihama, R. (2018). CRISPR/Cas9-based genome editing of transcription factor genes in Marchantia polymorpha. Methods Mol. Biol. 1830, 109–126. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-8657-6_7

Sugano, S. S., Nishihama, R., Shirakawa, M., Takagi, J., Matsuda, Y., Ishida, S., et al. (2018). Efficient CRISPR/Cas9-based genome editing and its application to conditional genetic analysis in Marchantia polymorpha. PloS One 13, e0205117. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0205117

Sugano, S. S., Shimada, T., Imai, Y., Okawa, K., Tamai, A., Mori, M., et al. (2010). Stomagen positively regulates stomatal density in arabidopsis. Nature 463, 241–244. doi: 10.1038/nature08682

Takahashi, F., Hanada, K., Kondo, T., Shinozaki, K. (2019). Hormone-like peptides and small coding genes in plant stress signaling and development. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 51, 88–95. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2019.05.011

Tsuboyama, S., Kodama, Y. (2018). AgarTrap protocols on your benchtop: Simple methods for Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation of the liverwort Marchantia polymorpha. Plant Biotechnol. 35, 93–99. doi: 10.5511/plantbiotechnology.18.0312b

Wang, R., Lu, L., Pan, X., Hu, Z., Ling, F., Yan, Y., et al. (2015). Functional analysis of OsPGIP1 in rice sheath blight resistance. Plant Mol. Biol. 87, 181–191. doi: 10.1007/s11103-014-0269-7

Wang, J., Tan, S., Zhang, L., Li, P., Tian, D. (2011). Co-Variation among major classes of LRR-encoding genes in two pairs of plant species. J. Mol. Evol. 72, 498–509. doi: 10.1007/s00239-011-9448-1

Wang, S., Tian, L., Liu, H., Li, X., Zhang, J., Chen, X., et al. (2020). Large-Scale discovery of non-conventional peptides in maize and arabidopsis through an integrated peptidogenomic pipeline. Mol. Plant 13, 1078–1093. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2020.05.012

Yamaoka, S., Inoue, K., Araki, T. (2021). Regulation of gametangia and gametangiophore initiation in the liverwort Marchantia polymorpha. Plant Reprod. 34, 297–306. doi: 10.1007/s00497-021-00419-y

Keywords: Marchantia polymorpha, signaling peptide, small ORF, reproductive induction, LRR protein

Citation: Kobayashi H, Murakami K, Sugano SS, Tamura K, Oka Y, Matsushita T and Shimada T (2023) Comprehensive analysis of peptide-coding genes and initial characterization of an LRR-only microprotein in Marchantia polymorpha. Front. Plant Sci. 13:1051017. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.1051017

Received: 22 September 2022; Accepted: 28 December 2022;

Published: 19 January 2023.

Edited by:

Kimitsune Ishizaki, Kobe University, JapanReviewed by:

Takehiko Kanazawa, Graduate University for Advanced Studies (Sokendai), JapanCopyright © 2023 Kobayashi, Murakami, Sugano, Tamura, Oka, Matsushita and Shimada. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tomoo Shimada, dHNoaW1hZGFAZ3IuYm90Lmt5b3RvLXUuYWMuanA=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.