94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Plant Sci. , 10 November 2022

Sec. Plant Nutrition

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.1042513

This article is part of the Research Topic The Role of Nitrate in Plant Response to Biotic and Abiotic Stress View all 8 articles

Nitrate is a key mineral nutrient required for plant growth and development. Plants have evolved sophisticated mechanisms to respond to changes of nutritional availability in the surrounding environment and the optimization of root nitrate acquisition under nitrogen starvation is crucial to cope with unfavoured condition of growth. In this study we present a general description of the regulatory transcriptional and spatial profile of expression of the Lotus japonicus nitrate transporter NRT2 family. Furthermore, we report a phenotypic characterization of two independent Ljnrt2.3 knock out mutants indicating the involvement of the LjNRT2.3 gene in the root nitrate acquisition and lateral root elongation pathways occurring in response to N starvation conditions. We also report an epistatic relationship between LjNRT2.3 and LjNRT2.1 suggesting a combined mode of action of these two genes in order to optimize the Lotus response to a prolonged N starvation.

Plants are sessile organisms growing under fluctuating environmental conditions with nutrient availability that may suddenly change over space and time (Oldroyd and Leyser, 2020). Nitrogen (N) in the form of nitrate is often a limiting resource for supporting plant growth and a regulated spatio-temporal pattern of expression of genes encoding nitrate transporters through the whole plant body represents a key resource to cope with local changes of nitrate conditions, providing nitrate uptake from the soil, translocation and storage/remobilization activities. Two protein families, the low-affinity Nitrate Transporter Peptide (NPF) and the high-affinity Nitrate Transporter (NRT2) play a primary role in this nitrate-related network (Wang et al., 2018). NRT2s represent small families of proton-coupled transporters including 7 and 4 members in Arabidopsis thaliana and Oryza sativa, respectively (Glass et al., 2001; Cai et al., 2008). All the NRT2 proteins characterized so far in higher plants, transport only nitrate as substrate, displaying a high affinity activity (HATS), except the O. sativa NRT2.4 that was reported to act as a dual affinity nitrate transporter in Xenopus laevis oocytes (Wei et al., 2018). The plant NRT2s transport activities depends by an additional component, NAR2/NRT3 that physically interact with NRT2s and is required for plasma membrane targeting and NRT2 stability (Kotur et al., 2012). The exceptions are represented by AtNRT2.7 and OsNRT2.4 that achieve nitrate uptake in Xenopus oocytes alone, without NAR2 co-expression (Chopin et al., 2007; Wei et al., 2018). The HATS for nitrate work at concentrations below 0.5 mM and it is constituted of both constitutive (cHATS) and nitrate-inducible (iHATS) components (Glass and Siddiqi, 1995; Crawford and Glass, 1998; Okamoto et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2012). The nitrate uptake activity has been reported in Arabidopsis for AtNRT2.1, AtNRT2.2, AtNRT2.4 and AtNRT2.5 (Li et al., 2007; Kiba et al., 2012; Lezhneva et al., 2014). AtNRT2.1 is strongly and quickly induced after addition of nitrate, playing a primary role in iHATS nitrate uptake (about 70%), whereas AtNRT2.2 makes a smaller contribution on this pathway (Filleur et al., 2001; Li et al., 2007). On the other hand, AtNRT2.4 and AtNRT2.5 transporters are active in the nutrient uptake without prior exposure to nitrate (cHATS) as they are induced by N-starvation conditions (Kiba et al., 2012; Lezhneva et al., 2014; Kotur and Glass, 2015). However, both the iHATS- and cHATS-mediated nitrate uptake are also involved in the primary nitrate (PNR) and the nitrogen starvation (NSR) responses that are triggered by nitrate treatment of N-depleted plants and by a prolonged N starvation condition, respectively (Hu et al., 2009; Krapp et al., 2011; Safi et al., 2021). PNR and NSR achieve a wide profile of gene expression, which includes among many, nitrate and nitrite reductases, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PDH), glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH3), transcription factors (TF), other than nitrate transporters (Wang et al., 2004; Krouk et al., 2010a; Kiba et al., 2012; Marchi et al., 2013; Zamboni et al., 2014). cHATS and iHATS are likely related each other in the control of NSR and PNR pathways as the cHATS system of nitrate uptake, activated without prior exposure, is required for the immediate acquisition of the nutrient in low nitrate conditions with the consequent induction of the iHATS-mediated nitrate uptake (Behl et al., 1988).

It is well known that nitrate serves not only as a N nutrient but also as a signal molecule that regulates different plant developmental processes including, root architecture, shoot development, seed germination and flowering (Zhang and Forde, 1998; Remans et al., 2006; Krouk et al., 2010b; Nacry et al., 2013; Lin and Tsay, 2017; Safi et al., 2017). The nitrate-mediated root growth, which involves lateral root (LR) initiation, lateral root elongation, root hair growth, and primary root growth is based on local and systemic nitrate signaling pathways that are integrated through long-distance communication to orchestrate root growth in response to the uneven nitrate concentration in soil (Forde, 2014). Several players involved in the nitrate signaling pathway have been identified, including nitrate transceptors, calcium signaling, kinases and transcription factors (Wang et al., 2018). In Arabidopsis a crucial role in the perception of external nitrate is played by the dual-affinity transceptor AtNPF6.3 (Remans et al., 2006; Ho et al., 2009) and AtNRT2.1 has been also reported to act as a nitrate sensor for root development (Little et al., 2005).

The study of nitrate uptake in crops represents a hotspot in agricultural studies because of its crucial role in determining the Nitrogen Use Efficiency (NUE). Improving NUE represents a very significant challenge in agriculture in order to reduce the input costs of farming for the production of N fertilizers and to alleviate the impact of eutrophication with consequent negative effects on soil and atmospheric pollution. N uptake efficiency (NUpE) is a crucial parameter that together with N utilization efficiency (NUtE) contributes to determine the NUE in crops (Xu et al., 2012). Several studies have been focused on the attempts to improve nitrate uptake through the manipulation of the nitrate transporter genes. Direct and un-direct over-expression of both NPF and NRT2 genes involved in the nitrate uptake pathways were reported to improve NUE in crops. In the case of the NRT2 genes, over-expression of the Oryza sativa OsNRT2.1, OsNRT2.3a and OsNRT2.3b leads to increased nitrate uptake enhancing the NUE (Chen et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2017; Luo et al., 2020). Interest on nitrate transporters in legumes has recently increased because of some reports pointed to identify the role of NPF and NRT2 genes in the nitrate dependent signaling pathways governing the initiation, development and functioning of the N2-fixing nodule (Omrane and Chiurazzi, 2009; Valkov and Chiurazzi, 2014), which represents the result of the symbiotic interaction with rhizobia (Yendrek et al., 2010; Valkov et al., 2017; Valkov et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020; Misawa et al., 2022). Nevertheless, studies on root nitrate uptake network in legumes, the identification of the transporters involved and the investigation of their involvement with the genetic programs governing root development is lagging behind.

Here we report a molecular characterization of the Lotus japonicus NRT2 family by analyzing the transcriptional regulatory profiles in response to N starvation conditions and by describing the spatial profile of expression of the NRT2 and NAR2 genes in Lotus roots. Furthermore, the phenotypic analysis carried out on two independents knocks out mutants indicates the involvement of LjNRT2.3 in the root nitrate acquisition and LR elongation pathways. The possible role and mode of action of LjNRT2.3 is discussed.

All experiments were carried out with Lotus japonicus ecotype B-129 F12 GIFU (Handberg and Stougaard, 1992; Jiang and Gresshoff, 1997). Plants were cultivated in a controlled growth chamber with a light intensity of 200 μmol.m-2.sec–1 at 23°C with a 16 h: 8 h, light: night cycle. Seeds sterilization was performed as described in Barbulova et al. (2005). Five days after sowing on H2O agar Petri dishes axenic conditions, unsynchronized seedlings were discarded. Seedlings were grown on solid growth media with the same composition than Gamborg B5 medium (Gamborg, 1970) except that (NH4)2SO4 and KNO3 were omitted and substituted by the proper KNO3 concentrations. KCl was added, when necessary to the medium to replace the same concentrations of potassium source. The media containing vitamins (Duchefa catalogue G0415) were buffered with 2.5 mM 2-(N-morpholino) ethanesulfonic acid (MES; Duchefa, M1503.0250) and pH adjusted to 5.7 with KOH. Plant length parameters were measured with the ImageJ software (Schneider et al., 2012).

M. loti inoculation was performed as described in Rogato et al. (2016). The strain R7A used for the inoculation experiments is grown in liquid TYR-medium supplemented with rifampicin (20 mg/l).

Tissues were first weighed and then frozen at -80°C. The frozen samples were grinded with a tissue lyser (Qiagen, 85220) at 29 Hz/for 1 min 30 sec. The powder was immediately resuspended in H2O (6 ml H2O/g of fresh weight), vortexed and centrifuged at 16.2 g to recover the supernatant. The colorimetric determination of nitrate content in leaves and roots extracts was described by Pajuelo et al. (2002). Briefly, 200 μl of 5% (w/v) salicylic acid in concentrated sulfuric acid is added to aliquots of 50 μL of crude extracts and left for 20 min at room temperature. NaOH (4.75 ml of 2N) is added to the reaction mixtures and absorbance scored at 405 nm after cooling. A calibration curve of known amount of NaNO3 (Sigma, 74246), dissolved in the extraction buffer is used as standard. Controls are prepared without salicylic acid.

Binary vectors were conjugated into the Agrobacterium rhizogenes 15834 strain (Stougaard et al., 1987). A. rhizogenes-mediated L. japonicus transformations have been performed as described in D’apuzzo et al., 2015. Inoculation of composite plants was described in Santi et al. (2003).

Promoter-gusA fusions. The PCR amplified fragments containing 1000 bp (LjNRT2.3), 1961 bp (LjNRT2.1) and 1229 bp (LjNAR2) upstream of the ATG were obtained on genomic DNA with forward and reverse oligonucleotides containing SalI (or HindIII) and BamHI sites, respectively (Supporting Information Table S1). The three amplicons were sub-cloned as SalI-BamHI (or HindIII-BamHI) fragments into the pBI101.1 vector to obtain translational fusions with the gusA marker (Jefferson, 1987).

Real time PCR was performed with a DNA Engine Opticon 2 System, MJ Research (MA, USA) using SYBR to monitor dsDNA synthesis. The procedure is described in Moscatiello et al. (2018). The ubiquitin (UBI) gene (AW719589) has used as an internal standard. The oligonucleotides used for the qRT-PCR are listed in the Supporting Information Table S1.

LORE1 lines 30016697 and 30078926 were obtained from the LORE1 collection (Fukai et al., 2012; Urbanski et al., 2012; Malolepszy et al., 2016). Plants in the segregating populations have been genotyped and expression of homozygous plants tested with oligonucleotides listed in the Supporting Information Table S1. After PCR genotyping, the clonal propagation of shoot cuts of homozygous plants in axenic conditions was performed as described in Sol et al. (2019).

Histochemical GUS staining, fixation and sections of the root material were performed as described in Rogato et al. (2008).

Statistical analyses were performed using the VassarStats two-way factorial ANOVA for independent samples program.

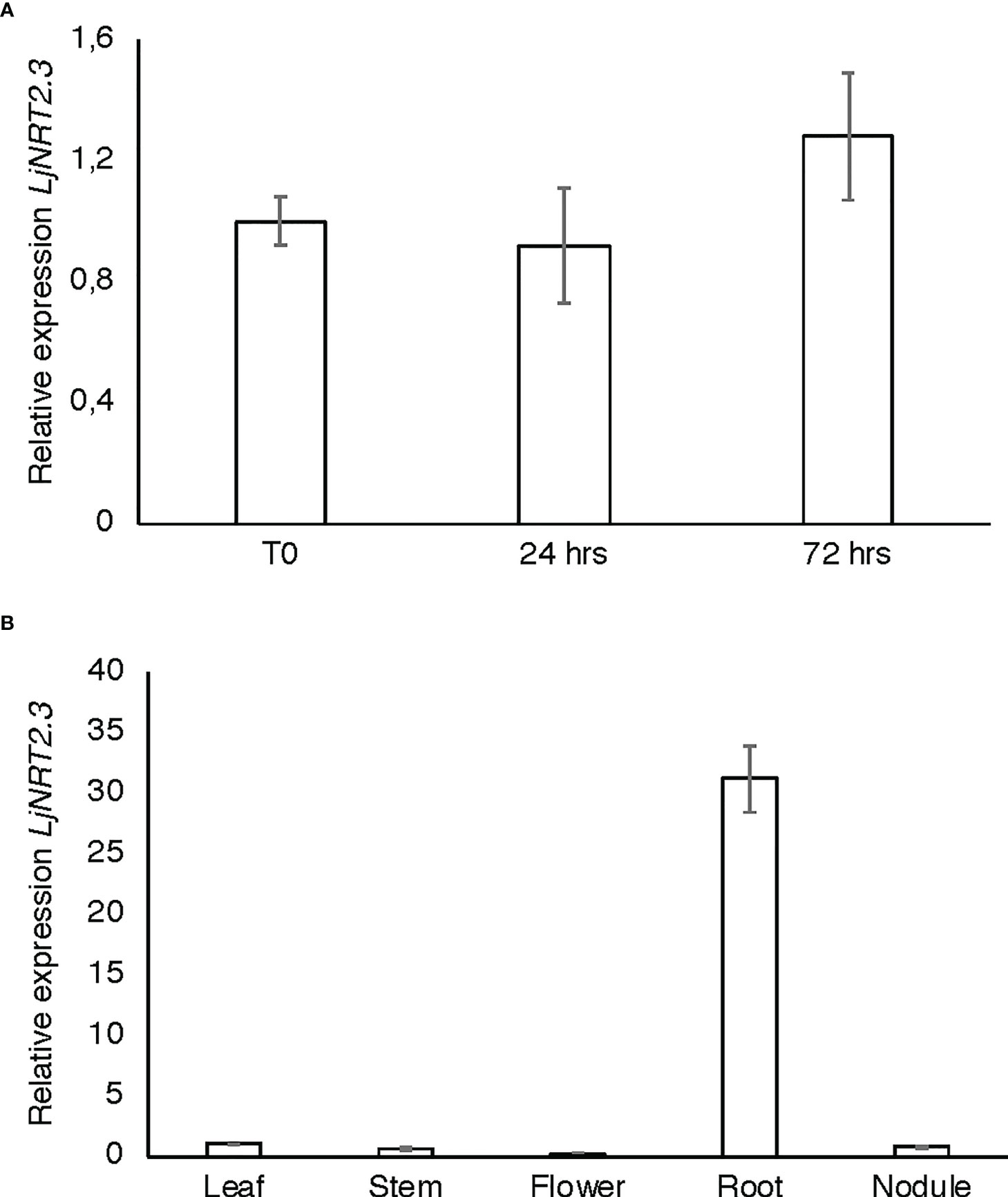

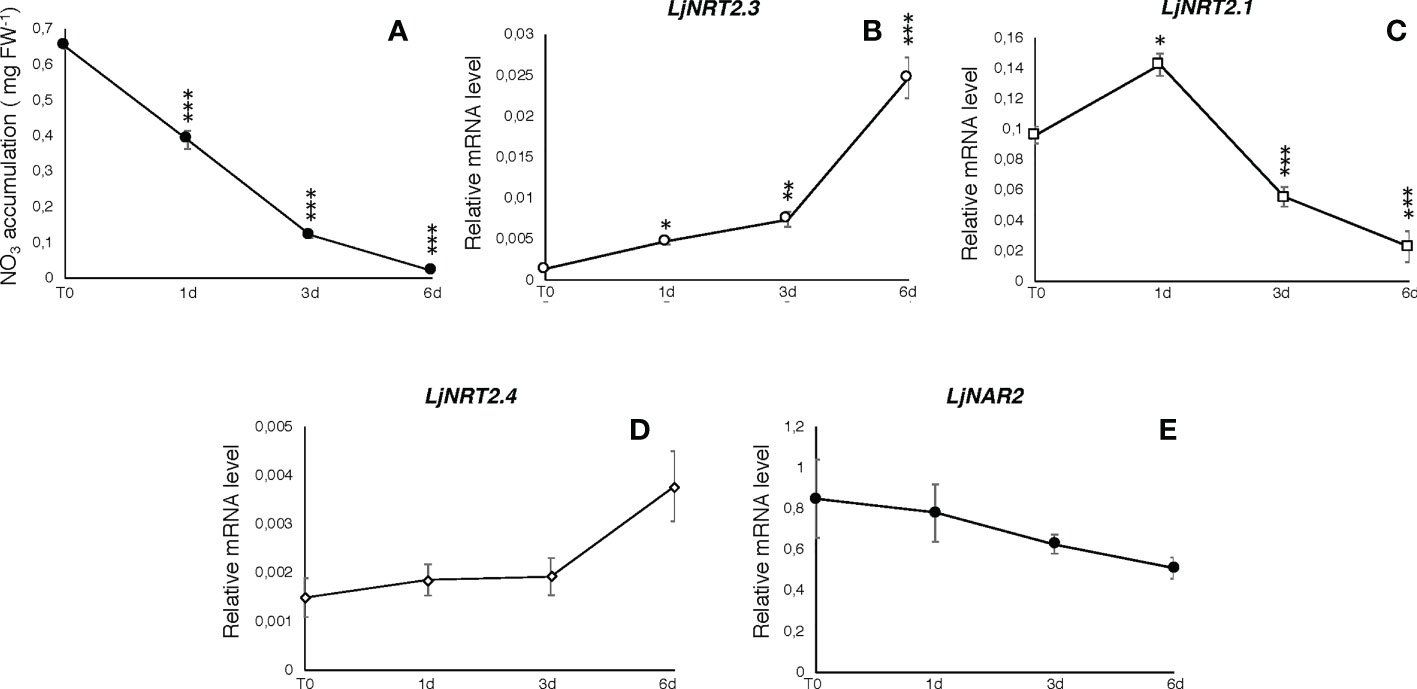

The L. japonicus NRT2 family has been first described as constituted by four members (LjNRT2.1-LjNRT2.4; Criscuolo et al., 2012). More recently, the analyses provided by Misawa et al. (2022) revealed an un-accurate gene prediction for the LjNRT2.2 gene in the L. japonicus MG20 ecotype (Lj3g3v3069050.1; http://www.kazusa.or.jp/lotus/index.html), with a premature stop codon determining a truncated version of the protein. This result was confirmed in the L. japonicus GIFU ecotype indicating an independent evolution of this gene in these Lotus ecotypes (Misawa et al., 2022). Therefore, the NRT2 family of L. japonicus is constituted by three functional genes. The name LjNRT2.3 has been assigned to the MG20 gene Lj4g3v1085060.1 and to the identical copy LotjaGi4g1v0155900.1, identified in the L. japonicus accession Gifu (Valkov et al., 2020; https://lotus.au.dk/). LjNRT2.3 encodes for a 507 amino acid protein with a molecular mass of 55.4 kDa and 11 TM predicted domains (Supplementary Figure S1; Tusnády and Simon, 2001). The two members of the L. japonicus NRT2 family previously characterized, LjNRT2.1 and LjNRT2.4 have been reported to play important roles in different steps of the nodulation program. Consistently, their profiles of expressions revealed a clear-cut relationship with the nodulation programme Misawa et al., 2022) as LjNRT2.4 shows a significant induced expression in the nodule organ (Valkov et al., 2020) and LjNRT2.1 is significantly expressed in the root cortical region, at early times after Mesorhizobium loti inoculation (Misawa et al., 2022). However, the relative expression profile of LjNRT2.3 is not regulated in the root and nodule tissues during the symbiotic interaction with M. loti (Figures 1A, B). Furthermore, the LjNRT2.3 transcript distribution in different L. japonicus organs indicated a substantial root-related expression profile (Figure 1B). LjNRT2.3 shares the highest level of amino acid identity with the AtNRT2.5 protein (74%). AtNRT2.5 (AT1G12940.1) was reported to be strongly induced in A. thaliana plants grown under nitrogen starvation (Lezhneva et al., 2014; Kotur and Glass, 2015). In the preliminary molecular characterization of LjNRT2.3 reported in Criscuolo et al. (2012), we have shown a quick induction of expression in roots of Lotus plants transferred in a medium supplemented with low KNO3 concentrations (0.01 and 0.1 mM) as compared to plants transferred in sufficient KNO3 conditions (1 and 2 mM). In order to better characterize the regulatory profile of LjNRT2.3, L. japonicus plants grown for 10 days in the presence of 8 mM KNO3 were transferred on a growth medium without N sources and a time course of expression was conducted with RNAs extracted from root tissue. As indicated in Figure 2A, the nitrate content in the Lotus plants decreased quickly and progressively after the transfer in N starvation conditions. The amount of the LjNRT2.3 transcript increased rapidly and strongly up to six days after transfer (23 fold; Figure 2B). This pattern of expression was unique for the LjNRT2 family as LjNRT2.1 displayed a progressive reduced level of expression, although a significant level of expression was maintained at the end of the N-starvation period (Figure 2C). LjNRT2.4 was only slightly induced (2.5 fold) after 6 days of N starvation (Figures 2C, D). We have also included in this transcriptional analysis the gene encoding for the activating partner protein NAR2 that is required for plasma membrane targeting and NRT2 stability (Kotur et al., 2012). A blast search in the Lotus genome database has led to the identification of a single homologous protein sharing 55% of amino acid identity with the Arabidopsis AtNAR2.1 protein that was named LjNAR2 (LotjaGi4g1v0227700.1). The profile of expression of LjNAR2 was unresponsive to N-starvation conditions (Figure 2E).

Figure 1 LjNRT2.3 transcriptional regulation. (A) Time course analysis in wild type L. japonicus root and nodule tissues after M. loti inoculation. RNAs were extracted from roots of seedlings grown in N starvation conditions at different times after inoculation (T0, 24 hrs, 72 hrs). (B) Expression in different organs. RNAs were extracted at four weeks after inoculation. Mature flowers were obtained from Lotus plants propagated in the growth chamber. Expression levels obtained by qRT-PCR were normalized with respect to the internal control ubiquitin (UBI) gene and plotted as relative to the expression of T0 (A) and flowers (B). Data bars represent the mean and standard deviations of data obtained with RNA extracted from three different sets of plants and 3 real-time PCR experiments.

Figure 2 Responses to N starvation conditions. Plants were grown for 8 days on B5 derived medium supplemented with 8 mM KNO3 as sole N source and transferred on N starvation conditions (T0). (A) Measures of nitrate content in Lotus plants during N starvation. Samples were collected at days 0, 1, 3 and 6. Measures are means and SE of three replicates (pooling 4 plants for every time point). Asterisks indicate significant differences as relative to nitrate content at T0 (*** p<0.0001). (B–E) Profiles of expression of LjNRT2 and LjNAR2 genes in response to N starvation. RNA was extracted from roots at T0, 1, 3 and 6 days after the transfer. Expression levels obtained by qRT-PCR were normalized with respect to the internal control ubiquitin (UBI) gene. Data represent the mean and standard deviations of results obtained with RNA extracted from three different sets of plants and 3 real-time PCR experiments. Asterisks indicate significant differences as relative to expression at T0 (*p<0.01; **p<0.001; ***p<0.0001).

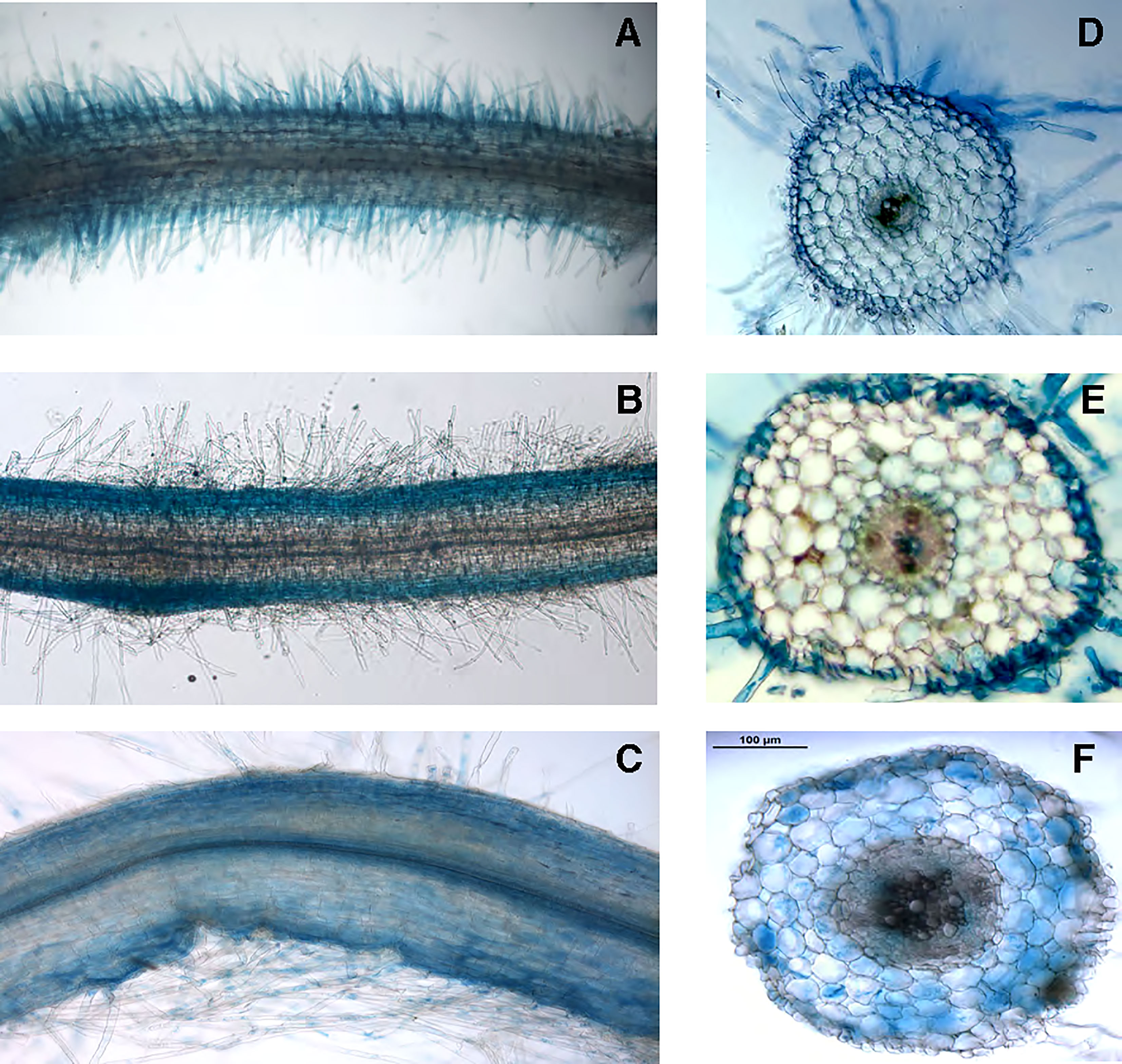

To gain further information about the physiological role played by LjNRT2.3 we have analyzed and compared the patterns of spatial distribution of GUS activity obtained in transgenic hairy roots transformed with the LjNRT2.3, LjNRT2.1 and LjNAR2 promoter-gusA fusions. The LjNRT2.3 expression was subtly confined to the epidermal root cell layer with a strong GUS activity detected in the root hairs (Figures 3A, D). This profile of spatial expression overlaps the one obtained for LjNRT2.1 (Figures 3B, E), which confirmed the pattern reported by Misawa et al. (2022). Interestingly, the LjNAR2 expression was not confined to the epidermis but also detected in the cortical root region (Figures 3C, F). The profile of expressions shown in Figure 3 suggests a role of LjNRT2.3 in enhancing nitrate uptake in the roots, although the data shown in Figure 2B indicate that such a function, which would be shared with LjNRT2.1, may be played in response to specific N starvation environmental conditions. The spatial pattern of expressions of the NRT2 genes in L. japonicus is completed by the one already reported for LjNRT2.4 that is specifically expressed in the root vascular structures and hence appears to not directly participate to the root nitrate uptake from the soil (Valkov et al., 2020).

Figure 3 Representative GUS activity of L. japonicus transgenic hairy roots transformed with the prLjNRT2.3- (A, D), prLjNRT2.1- (B, E) and prLjNAR2-gusA (C, F) constructs. (A–C) whole mount root samples. (D–F) 70 μm root cross sections.

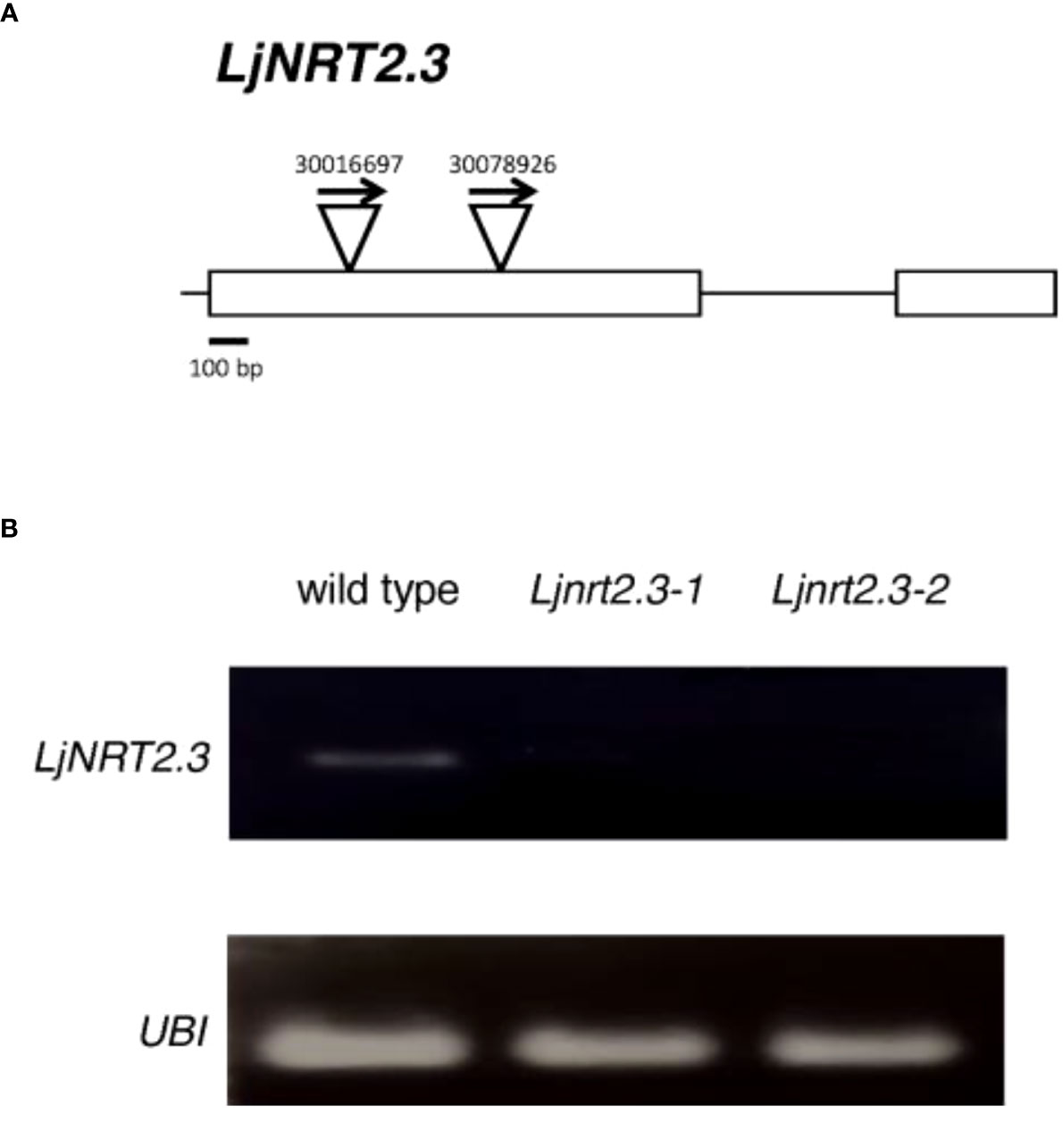

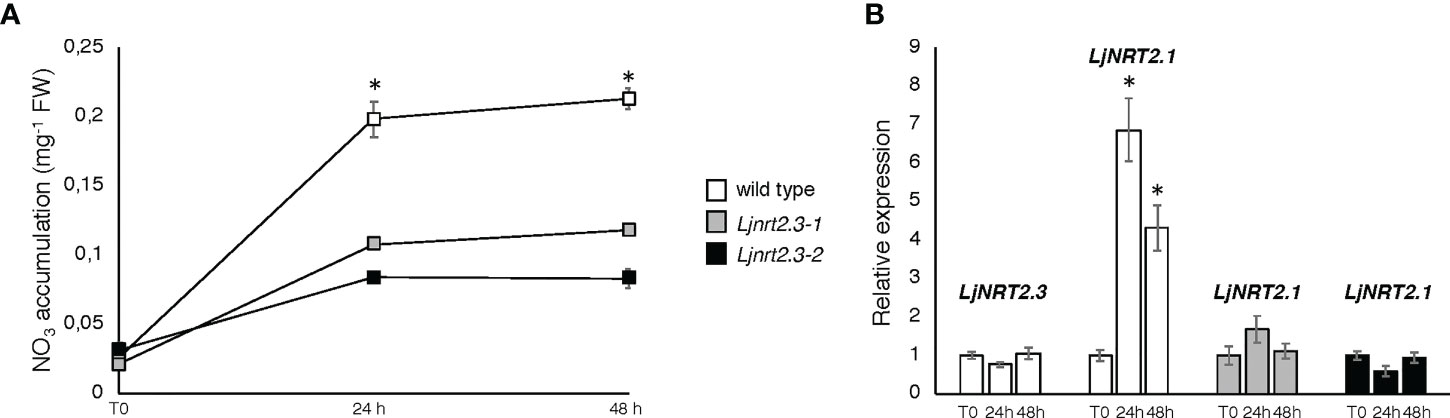

In order to investigate the physiological function of LjNRT2.3, two independent LORE1 insertion mutants have been isolated from the L. japonicus LORE1 lines collection (Fukai et al., 2012; Urbanski et al., 2012; Malolepszy et al., 2016). Lines 30016697 and 30078926, bearing retrotransposon insertions in the first exon (Figure 4A), were genotyped by PCR. Endpoint RT-PCR analyses on RNAs extracted from roots of homozygous plants from lines 30016697 and 30078926 (hereafter called Ljnrt2.3-1 and Ljnrt2.3-2, respectively) revealed no detectable LjNRT2.3 full size mRNA and hence, considered null mutants (Figure 4B). In order to test whether the induced pattern of expression observed for LjNRT2.3 under N starvation conditions (Figure 2B) represents a pre-requisite for an efficient nitrate uptake in Lotus roots after the transfer in the presence of low nitrate concentrations, we have compared the nitrate accumulation in roots of wild type and mutant plants. Plants have been grown as for the experimental scheme described in Figure 2. After 6 days of growth in a medium without N sources, wild type and Ljnrt2.3 plants were transferred in the same medium supplemented with 0.5 mM KNO3 and the root nitrate content was measured in a time course experiment. A clear-cut reduction in NO3- content was scored in both the Ljnrt2.3-1 and Ljnrt2.3-2 roots as compared to wild type at 24 and 48 hrs after the transfer, strongly suggesting the involvement of LjNRT2.3 in root nitrate acquisition (Figure 5A). This was also confirmed by the profile of expression of LjNRT2.3 that was maintained constant up to 48 hrs after the transfer in the presence of 0.5 mM KNO3 (Figure 5B). Moreover, we have also evaluated the involvement of LjNRT2.1, which shares with LjNRT2.3 the spatial pattern of expression in the epidermal cell layer (Figures 2A–D). LjNRT2.1 has been recently reported to be involved in the root nitrate uptake at both low (0.2 mM) and high (10 mM) KNO3 conditions and this was also correlated to a reduced nitrate content in the roots of mutants grown in the presence of 10 mM KNO3 as compared to wild type (Misawa et al., 2022). Interestingly, the qRT-PCR results shown in Figure 5B indicates a significant induction of LjNRT2.1 in wild type roots after the transfer in the presence of 0.5 mM KNO3 (up to 7-fold at 24 hrs; Figure 5B) and this profile was completely abolished in the Ljnrt2.3 genetic background (Figure 5B).

Figure 4 (A) Exon/intron organization of the LjNRT2.3 gene. Insertion sites, relative orientations of the LORE1 retrotransposon element in the 30016697 and 30078926 lines are indicated. (B) LjNRT2.3 is not expressed in the LORE1 homozygous mutant lines Ljnrt2.3-1 and Ljnrt2.3-2.

Figure 5 Plants were grown for 8 days on B5 derived medium supplemented with 8 mM KNO3 as sole N source and then transferred under N starvation conditions for 6 days. At the end of the LjNRT2.3 induction period, plants were transferred on the same medium supplemented with 0.5 mM KNO3 (T0) to score nitrate content and expression profiles at 24 and 48 hrs. (A) Nitrate content in roots of wild type and Ljnrt2.3 plants. Data represent means and SE from three independent experiments (8 plants per experiment). Asterisks indicate significant differences (p<0.001) of nitrate content in wild type and Ljnrt2.3-1 plants. (B) Profiles of LjNRT2.1 and LjNRT2.3 expression in roots of wild type and Ljnrt2.3 plants in response to 0.5 mM KNO3 repletion. Data bars represent means and SD from three independent experiments. Asterisks indicate significant differences as relative to expression at T0 (*p<0.0001). The plant genotypes are indicated.

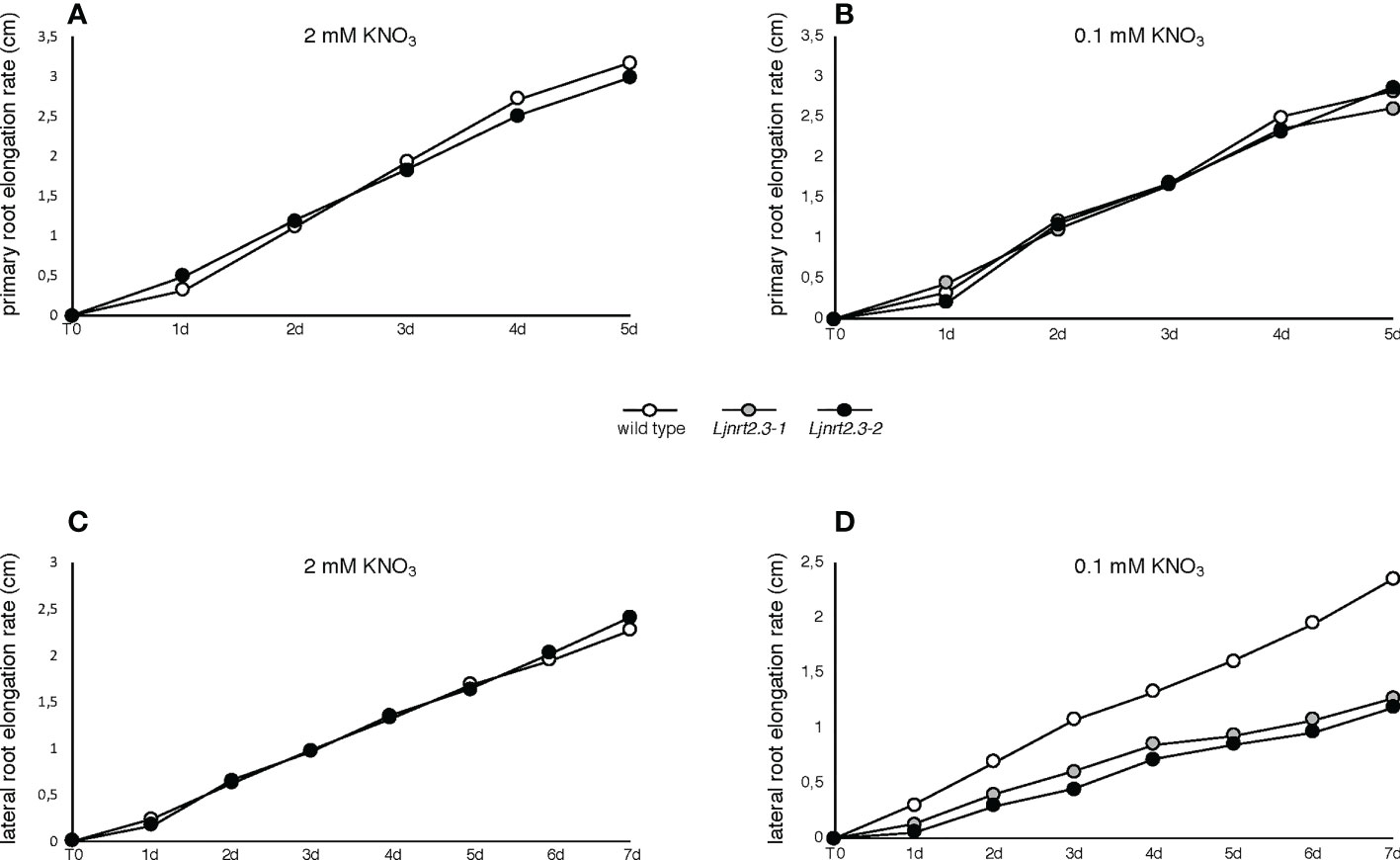

In addition to its role as nutrient, nitrate has been proved to act as a signal regulating many physiological processes, including root architecture. The results reported in Figure 5A prompted us to investigate whether the changes scored in the nitrate acquisition capacity of the Ljnrt2.3 mutants could also determine an alteration of the signaling pathways controlling the root system developmental programs. Therefore, the experimental scheme adopted to maximize the expression of the LjNRT2.3 gene has been exploited to check whether the root elongation programme was affected in the Ljnrt2.3 knock out background. After the induction treatment (6 days of N starvation conditions) plants have been transferred under two different KNO3 conditions, 0.1 mM and 2 mM and the kinetics of elongation of primary root and LRs scored for 5 and 7 days, respectively. Wild type and mutant plants did not exhibit evident shoot growth phenotypes at the end of this cycle of growth (Supplementary Figure S2). Nevertheless, this experimental system allowed to reveal striking differences in the kinetics of root elongation. The kinetics of elongation of the primary roots in both nitrate conditions were quite similar and constant (about 0.5 cm/day) and no differences were revealed between wild type and Ljnrt2.3 plants (Figures 6A, B). In the same way, the mean of the kinetics of LR elongation remained constant in wild type and mutant plants in the presence of 2 mM KNO3 (Figure 6C; about 0.3 cm/day). Interestingly, the kinetics of elongation of LR scored in 0.1 mM KNO3 conditions, showed a significant difference in both Ljnrt2.3-1 and Ljnrt2.3-2 plants as compared to wild type with a progressive slowdown of the elongation rate (Figure 6D; 0.32 cm/day vs 0.18 cm/day).

Figure 6 Root elongation rates in wild type and Ljnrt2.3 plants. (A, B) elongation rate of primary roots of wild type and Ljnrt2.3-1 plants. (C, D) elongation rate of lateral roots of wild type, Ljnrt2.3-1 and Ljnrt2.3-2 plants. Synchronized seedlings were grown for 8 days on B5 derived medium supplemented with 8 mM KNO3 as sole N source and then transferred under N starvation conditions for 6 days. Then plants were transferred on 0.1 mM and 2 mM KNO3 (T0) and measures of primary and lateral roots taken every day. The scoring was carried out on lateral roots long at least 0,3 cm at the time of the transfer. The KNO3 concentrations and plant genotypes are indicated. Wild type and Ljnrt2.3 plants were grown in the same square Petri dishes to minimize the differences of growth conditions. Data represent means of measures performed in two/three independent experiments (18 plants per experiment per condition). A significant difference (p<0.001) was obtained for lateral roots of the Ljnrt2.3 plants scored from T0 to 7d in 0.1 mM KNO3.

The distribution of NRT2 families in land plants is very patchy with a number of members that does not linearly fits with the level of ploidy and overall genome size in different monocot and dicot plants. The number of NRT2 genes spans from 33 in Triticum aestivum, 17 in Brassica napus, 7 in A. thaliana, 5 in O. sativa, 6 in Populus trichocarpa, 6 in Manihot esculenta, 4 in Hordeum vulgare, 4 in Solanum lycopersicon, 2 in Cucumis sativus, 9 in Physcomitrella patens (Zoghbi-Rodrìguez et al., 2021; Akbubak et al., 2022). The situation is even more intriguing in legumes where the reported number of NRT2 genes is generally low: 3 in L. japonicus (Misawa et al., 2022), 3 in M. truncatula (Pellizzaro et al., 2015), 5 in Glycine soya (You et al., 2020), 1 in Pisum sativum (Gu et al., 2022). It was recently hypothesized that the decreased number of NRT2 genes and less reliance on NO3- in legumes could be related to the evolution of the supplying capacity from N-fixing nodules (Gu et al., 2022). This heterogenicity makes difficult the identification of possible functional orthologues among the NRT2 proteins of various plants with the exception of AtNRT2.5, where phylogenetic analyses have revealed the existence of closely related orthologues in both dicots and monocots with the exception of Solanaceae (Plett et al., 2010; Kotur and Glass, 2015). However, functional divergency may have evolved for NRT2.5s in different species and environments as for alophyte and non-alophyte plants (Liu et al., 2020). We have already reported the phylogenetic analysis that places the LjNRT2.3 gene in the NRT2.5 sub-group (Valkov et al., 2020). The profile of expression displayed by LjNRT2.3 in different organs (Figure 1B) resembles the one reported for AtNRT2.5 and OsNRT2.3a with a preferential expression in roots (Tang et al., 2012; Lezhneva et al., 2014). However, the preferential expression in roots is not a constant feature in different plant species as in some monocots the NRT2.5 transcript level is increased in the shoot (Lezhneva et al., 2014). NRT2.5 expression has been also reported in embryos and shell in wheat (Sabermanesh et al., 2017) as well as cobs in corn indicating a role in the accumulation of nitrate in seed and filling of the grain (Ju et al., 2019). However, LjNRT2.3 expression in seed tissue is not reported in the RNAseq data of the Lotus expression atlas (https://lotus.au.dk/expat/). On the contrary, what seems to represent an evolutionary conserved mark in most plant species is the increase in the NRT2.5-like gene expressions in roots in response to N starvation (Lezhneva et al., 2014; Guo et al., 2014). This regulatory profile has been also confirmed in our experimental conditions for the LjNRT2.3 gene (Figure 2B). Interestingly, the LjNRT2.3 and LjNRT2.1 genes displayed a complementary response to N starvation in roots with the latter showing a significant progressive reduction (up to seven-fold) in the level of transcription after a transient slight increase (Figure 2C). The same regulatory profile has been reported for AtNRT2.1 in adult plant (Lezhneva et al., 2014). The profiles of expressions of LjNRT2.4 and LjNAR2 genes did not change significantly in response to N starvation in Lotus roots with the latter still maintaining the highest level of transcription (Figures 2B–E). The analysis in transgenic hairy roots transformed with the prLjNRT2.3-gusA fusion indicated a spatial profile of expression for LjNRT2.3 confined to epidermis and root hairs of primary and lateral roots (Figure 3A), suggesting a nitrate root uptake function. Consistently, this spatial profile of expression has been also reported for AtNRT2.5, which plays a role on high affinity nitrate acquisition in roots (Lezhneva et al., 2014; Kotur and Glass, 2015). Moreover, AtNRT2.5 is also expressed in the phloematic root tissue playing a role on nitrate loading and mobilization to the shoot under conditions of N starvation (Lezhneva et al., 2014). A similar function was reported for OsNRT2.3a that is mainly expressed in the xylem parenchyma cells of the root stele being involved in the transport of nitrate from root to shoot under low NO3- conditions (Tang et al., 2012). Interestingly, LjNAR2 is spatially co-expressed with LjNRT2.3 in the epidermal cell layer (Figure 3), as expected for a partner protein that facilitates the plasma membrane localization of NRT2s. The description of the pattern of spatial expression of the Lotus NRT2 genes in Figure 3 is completed with that of LjNRT2.1, which is also confined to the epidermal cell layer in agreement with the recently reported involvement on nitrate uptake in both low and high nitrate conditions (Misawa et al., 2022). To our knowledge, this is the first report of the spatial pattern of expression of the whole NRT2 family members in legumes. In M. truncatula the MtNRT2.3 gene, orthologue of LjNRT2.3 (83% amino acid identity; Valkov et al., 2020), shows an induced expression in nodules (Pellizzaro et al., 2015). Interestingly, this nodule-induced expression profile is not observed for LjNRT2.3 (Figure 1) but it is shared in L. japonicus by the LjNRT2.4 gene (Criscuolo et al., 2012; Valkov et al., 2020).

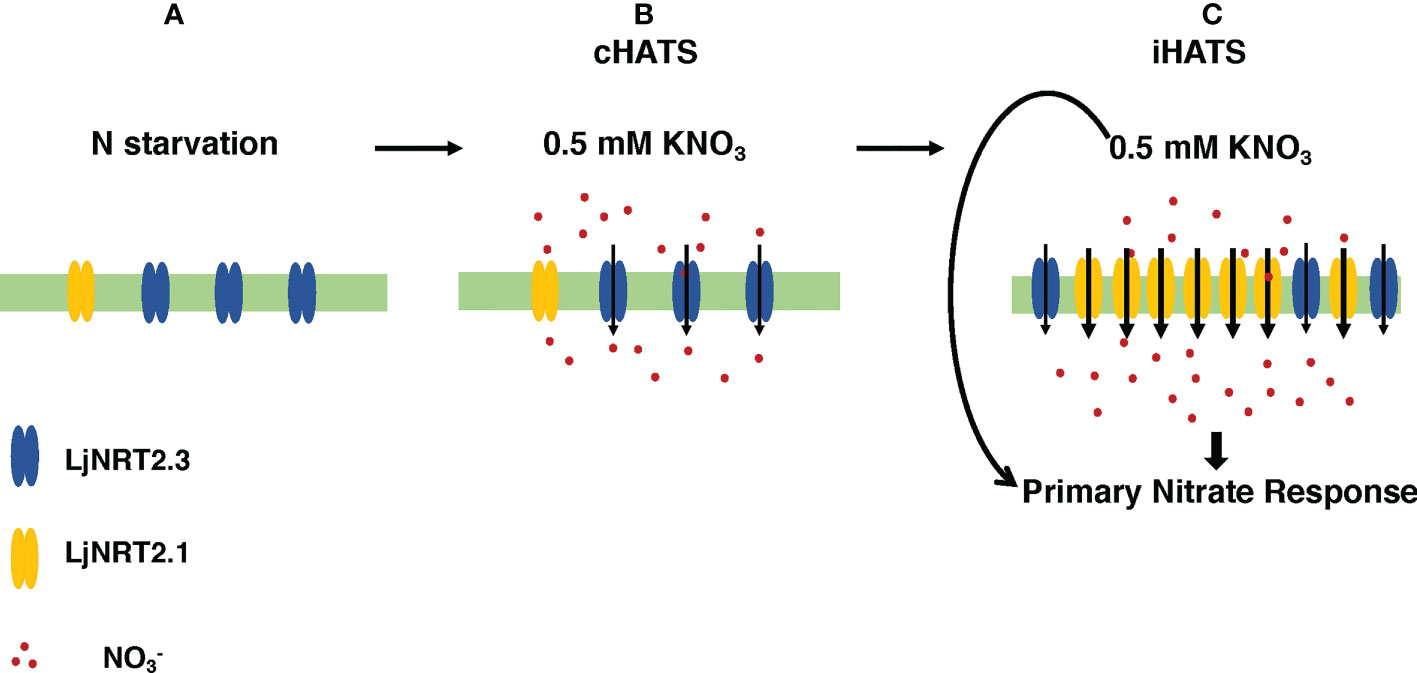

The phenotypic characterization carried out with two independent Ljnrt2.3 knock out mutants indicated a significant reduction of nitrate content in the roots of mutants exposed to low nitrate conditions after a prolonged (six days) N starvation treatment as compared to wild type (Figure 5A). As expected the LjNRT2.3 transcript level did not change in wild type plants transferred in the presence of 0.5 mM KNO3, whereas the LjNRT2.1 expression was strongly induced by this treatment (Figure 5B). A quick nitrate dependent induction of expression for LjNRT2.1 in Lotus roots was previously reported after exposure to both low and high nitrate conditions (Criscuolo et al., 2012; Misawa et al., 2022). However, the LjNRT2.1 induced profile of expression is completely abolished in the Ljnrt2.3 genetic background (Figure 5B). An epistatic relationship between these NRT2 genes has been already suggested in Arabidopsis by the analysis carried out by Kotur and Glass (2015) where the AtNRT2.1 expression was significantly reduced in the Atnrt2.5 mutants after treatment with 1 mM KNO3. The presence in L. japonicus of the LjNRT2.1 and LjNRT2.3 as the only two genes involved in nitrate uptake in the high affinity range facilitates the understanding of their mutual functional relationship. In fact, it can be excluded as in A. thaliana, a role in the control of HATS due to a compensatory up-regulation of other genes such as AtNRT2.2 in the Atnrt2.1 genetic background (Li et al., 2007). The 60% reduction of nitrate content observed in the roots of the Ljnrt2.3 mutants can be explained by a combined action of the LjNRT2.3 and LjNRT2.1 genes on the nitrate uptake mediated by the HATS in response to N starvation conditions. In particular, the expression of LjNRT2.3 in roots exposed to N starvation may warrant the quick initiation of the nitrate uptake and assimilation pathway to set in motion the LjNRT2.1-mediated nitrate HATS pathway (Behl et al., 1988; Kotur and Glass, 2015) is schematized in the model hypothesized in the Figure 7. Consistently with this model, AtNRT2.1 has been reported as the major contributor to the iHATS activity with a nitrate dependent induced expression in Arabidopsis (Filleur et al., 2001; Okamoto et al., 2003; Li et al., 2007), but a significant reduction in the cHATS-mediated NO3- influx has been also reported for Atnrt2.5 mutants in adult plants grown for 10 days under N starvation conditions and then transferred in the presence of 0.2 mM KNO3 (Lezhneva et al., 2014). The partial nitrate acquisition scored at 24 hrs in the roots of the Ljnrt2.3 plants (40% as compared to wild type roots) and maintained until 48 hrs (Figure 5A) could be achieved by LjNRT2.1, which still exhibits a significant, basic level of expression at the end of the period of N starvation (Figure 2C). The cHATS provided by LjNRT2.3 is likely characterized by higher affinity and lower capacity for nitrate (Siddiqi et al., 1990; Kronzucker et al., 1995; Glass and Siddiqi, 1995; Crawford and Glass, 1998), hence warranting a more efficient and quick plant response in the presence of extremely low amounts of available nitrate in the rhizosphere.

Figure 7 Hypothetical model of the combined action exerted by LjNRT2.3 and LjNRT2.1 to achieve the iHATS and the primary nitrate response after prolonged N starvation conditions. Plasma membrane localization and uptake activity of LjNRT2.3 are based on data reported for the orthologous AtNRT2.5 (Kotur et al., 2012; Lezhneva et al., 2014). (A) Induction of LjNRT2.3 under N starvation conditions. (B) LjNRT2.3-mediated cHATS. (C) LjNRT2.1-mediated iHATS and triggering of the primary nitrate response. Arrows in (C) indicate local and systemic nitrate-mediated signalling pathways.

The phenotypic characterization carried out with the Ljnrt2.3-1 plants indicates a very intriguing role of LjNRT2.3 gene on the LR elongation program when plants are transferred in the presence of low KNO3 concentrations (0.1 mM) after a prolonged N starvation treatment. The LR elongation rate of the Ljnrt2.3-1 mutants is half that of wild type plants and this difference is not scored in the presence of 2 mM KNO3 (Figures 6C, D). The nitrate-related LR development pathway presents two major features in many plant species: i) a systemic repression of LR growth in the presence of high nitrate supply; ii) a local stimulation of LR growth by exogenous NO3- supply. In A. thaliana, a localized patch of NO3- in a split agar plate triggers a preferential LR growth in the region of the patch due to both an increase of LR elongation and stimulation of LR primordia emergence in the nitrate enriched region (Zhang and Forde, 1998; Zhang et al., 1999; Linkohr et al., 2002; Remans et al., 2006; Krouk et al., 2010b). When roots encounter a NO3- patch of soil, a rapid physiological response is achieved, consisting of a localized and transient increase in NO3- uptake associated to a slower developmental response characterized by higher rates of LR proliferation within the patch (Forde, 2002). Local and systemic nitrate signaling needs to be integrated through long-distance communication to control root growth in response to the variegated nitrate concentration in soil. Therefore, LR development is controlled by a very intricated network involving NO3- uptake and signaling. In particular, NO3- induces transcription of its own transport and assimilation pathways and of several players involved in the nitrate signaling pathway, including nitrate transceptors, regulators of calcium signaling, kinases, transcription factors, and various peptides (Omrane et al., 2009; Krouk et al., 2010a; Bellegarde et al., 2017). Finally, strong bodies of evidence indicate that many adaptive developmental responses to changes in N availability are triggered by a cross talk between N and hormone signaling pathways. Plants normally develop a more exploratory root system with longer LRs also under N deficiency (Lopez-Bucio et al., 2003; Ruffel et al., 2011) and the effect of N deprivation or low N on root branching depends on the plant nitrogen nutritional condition and the of plant stress (Krouk et al., 2010b; Forde, 2014).

The epistatic relationship between LjNRT2.3 and LjNRT2.1 and hence the reduced expression of LjNRT2.1 observed in the Ljnrt2.3 background could also explain the defect of LRs elongation rate displayed by the Ljnrt2.3 mutants (Figure 6D). Consistently, Atnrt2.1 mutants grown on vertical agar plates supplied with 0.25 mM KNO3 show a reduced LR growth and this phenotype, which is not scored in the presence of 2.5 mM KNO3 (Li et al., 2007), was associated to a significant reduction of the nitrate uptake (Li et al., 2007). Similar results have been obtained in cucumber and rice where knock-down and overexpressing OsNRT2.1 plants, show a reduction and increase of the nitrate-dependent root elongation by regulating auxin transport to roots, respectively (Li et al., 2018; Naz et al., 2019). Interestingly, in common wheat the over-expression of the Triticum aestivum TaNRT2.5 gene triggers higher nitrate accumulation and improved NUE, which was also associated to an increased root elongation capacity (Li et al., 2020). Moreover, a reduction of LR growth has been also reported for Atnrt2.5 mutants that abolish the positive effect due to inoculation with the plant growth promoting bacterium strain Phyllobacterium brassicacearum (Kechid et al., 2013).

In conclusion, our research demonstrates the hierarchical role played by LjNRT2.3 in the orchestration of the response achieved to optimize the nitrate acquisition in Lotus roots facing low nitrate concentrations after a prolonged period of N starvation. LjNRT2.3 acts as a sentinel gene induced without prior exposure to nitrate that plays an epistatic control on the LjNRT2.1 expression.

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

All the authors critically discussed results and development of the work. AR and VV have designed and performed the experiments. MC has designed the experiments and written the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by CNR project FOE-2019 DBA.AD003.139 and within the Agritech, National Research Center and received funding from the European Union Next Generation EU, Piano Nazionale di Ripresa e Resilienza (PNRR) – Missione 4, Componente 2, Investimento 1.4 - D.D.1032, 17/06/2022, CN00000022. This manuscript reflects only the author’s views and opinions, neither the European Union nor the European Commission can be considered responsible for them.

We thank Marco Petruzziello, Francesca Segreti and Giuseppina Zampi for technical assistance.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2022.1042513/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Figure 1 | (A) Amino acid sequence of LjNRT2.3. (B) TMHMM prediction of LjNRT2.3 (Tusnády and Simon, 2001).

Supplementary Figure 2 | (A) Representative images of wild type and Ljnrt2.3-1 plants. Growth conditions: 10 days on 8 mM KNO3, 6 days on N starvation, 7 days on 0.1 mM or 2 mM KNO3. (B) Measures of shoot length per plant at the end of the period of growth (two independent experiments, 18 plants per experiment per condition). (C) Measures of shoot fresh weight per plant at the end of the period of growth.

Akbubak, M. A., Filiz, E., Cetin, D. (2022). Genome-wide identification and characterization of high-affinity nitrate transporter 2 (NRT2) gene family in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) and their transcriptional responses to drought and salinity stresses. J. Plant Physiol. 272, 153684. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2022.153684

Barbulova, A., D’Apuzzo, E., Rogato, A., Chiurazzi, M. (2005). Improved procedures for in vitro regeneration and for phenotypical analysis in the model legume Lotus japonicus. Funct. Plant Biololy 32, 529–536. doi: 10.1071/FP05015

Behl, R., Tischner, R., Raschke, K. (1988). Induction of a high capacity nitrate-uptake mechanism in barley roots prompted by nitrate uptake through a constitutive low capacity mechanism. Planta 176, 235–240. doi: 10.1007/BF00392450

Bellegarde, F., Gojon, A., Martin, A. (2017). Signals and players in the transcriptional regulation of root responses by local and systemic n signaling in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Bot. 68, 2553–2565. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erx062

Cai, C., Wang, J. Y., Zhu, Y. G., Shen, Q. R., Li, B., Tong, Y. P., et al. (2008). Gene structure and expression of the high-affinity nitrate transport system in rice roots. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 50, 443–451. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2008.00642.x

Chen, J., Fan, X., Qian, K., Zhang, Y., Song, M., Liu, Y., et al. (2017). pOsNAR2.1: OsNAR2.1 expression enhances nitrogen uptake efficiency and grain yield in transgenic rice plants. Plant Biotechnol. J. 15, 1273–1283. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12714

Chen, J., Zhang, Y., Tan, Y., Zhang, M., Zhu, L., Xu, G., et al. (2016). Agronomic nitrogen-use efficiency of rice can be increased by driving OsNRT2.1 expression with the OsNAR2.1 promoter. Plant Biotechnol. J. 14, 1705–1715. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12531

Chopin, F., Orsel, M., Dorbe, M. F., Chardon, F., Truong, H. N., Miller, A. J., et al. (2007). The Arabidopsis ATNRT2.7 nitrate transporter controls nitrate content in seeds. Plant Cell 19, 1590–1602. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.050542

Crawford, N. M., Glass, A. D. M. (1998). Molecular and physiological aspects of nitrate uptake in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 3, 389–395. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(98)01311-9

Criscuolo, G., Valkov, V. T., Parlati, A., Martin-Alves, L., Chiurazzi, M. (2012). Molecular characterization of the Lotus japonicus NRT1(PTR) and NRT2 families. Plant Cell Environ. 35, 1567–1581. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2012.02510.x

D’apuzzo, E., Valkov, T. V., Parlati, A., Omrane, S., Barbulova, A., Sainz, M. M., et al. (2015). PII overexpression in Lotus japonicus affects nodule activity in permissive low nitrogen conditions and increases nodule numbers in high nitrogen treated plants. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 28, 432–442. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-09-14-0285-R

Filleur, S., Dorbe, M. F., Cerezo, M., Orsel, M., Granier, F., Gojon, A., et al. (2001). An Arabidopsis T-DNA mutant affected in NRT2 genes is impaired in nitrate uptake. FEBS Lett. 489, 220–224. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02096-8

Forde, B. G. (2002). Local and long-range signaling pathways regulating plant responses to nitrate. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 53, 223–234. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.53.100301.135256

Forde, B. G. (2014). Nitrogen signaling pathways shaping root system architecture: an update. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 21, 30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2014.06.004

Fukai, E., Soyano, T., Umehara, Y., Nakayama, S., Hirakawa, H., Tabata, S., et al. (2012). Establishment of a Lotus japonicus gene tagging population using the exon-targeting endogenous retrotransposon LORE1. Plant J. 69, 720–730. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04826.x

Gamborg, O. L. (1970). The effects of amino acids and ammonium on the growth of plant cells in suspension culture. Plant Physiol. 45, 372–375. doi: 10.1104/pp.45.4.372

Glass, A. D. M., Brito, D. T., Kaiser, B. N., Kronzucker, H. J., Kumar, A., Okamoto, M., et al. (2001). Nitrogen transport in plants, with an emphasis on the regulation of fluxes to match plant demand. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 164, 199–207. doi: 10.1002/1522-2624(200104)164:2<199::AID-JPLN199>3.0.CO;2-k

Glass, A. D. M., Siddiqi, M. Y. (1995). “Nitrogen absorption by plants roots,” in Nitrogen nutrition in higher plants. Eds. Srivastava, H. S., Singh, R. P. (New Delhi: Associated Publishing), 21–56.

Gu, B., Chen, Y., Xie, F., Murray, J. D., Miller, J. A. (2022). Inorganic nitrogen transport and assimilation in pea (Pisum sativum). Genes 13, 158. doi: 10.3390/genes13010158

Guo, T., Xuan, H., Yang, Y., Wang, L., Wei, L., Wang, Y., et al. (2014). Transcription analysis of genes encoding the wheat root transporter NRT1 and NRT2 families during nitrogen starvation. J. Plant Growth Regul. 33, 837–848. doi: 10.1007/s00344-014-9435-z

Handberg, K., Stougaard, J. (1992). Lotus japonicus, an autogamous, diploid legume species for classical and molecular genetics. Plant J. 2, 487–496. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.1992.00487.x

Ho, C. H., Lin, S. H., Hu, H. C., Tsay, Y. F. (2009). CHL1 functions as a nitrate sensor in plants. Cell 138, 1184–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.004

Hu, H. C., Wang, Y. Y., Tsay, Y. F. (2009). AtCIPK8, a CBL-interacting protein kinase, regulates the low-affinity phase of the primary nitrate response. Plant J. 57, 264–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03685.x

Jefferson, R. A. (1987). Assaying chimeric genes in plants: the GUS gene fusion system. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 5, 387–405. doi: 10.1007/BF02667740

Jiang, Q., Gresshoff, P. M. (1997). Classical and molecular genetics of the model legume Lotus japonicus. Mol. Plant Microbe Interaction 10, 59–68. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.1997.10.1.59

Ju, L. L., Deng, G. B., Liang, J. J., Zhang, H. L., Li, Q., Pan, Z. F., et al. (2019). Structural organization and functional divergence of high isoelectric point α-amylase genes in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum l.) and barley (Hordeum vulgare l.). BMC Genet. 20, 1–17. doi: 10.1186/s12863-019-0732-1

Kechid, M., Desbrosses, G., Rokhsi, W., Varoquaux, F., Djekoun, A., Touraine, B. (2013). The NRT2.5 and NRT2.6 genes are involved in growth promotion of Arabidopsis by the plant growth-promoting rhizobacterium (PGPR) strain Phyllobacterium brassicacearum STM196. New Phytol. 198, 514–524. doi: 10.1111/nph.12158

Kiba, T., Feria-Bourrellier, A. B., Lafouge, F., Lezhneva, L., Boutet-Mercey, S., Orsel, M., et al. (2012). The Arabidopsis nitrate transporter NRT2.4 plays a double role in roots and shoots of nitrogen-starved plants. Plant Cell 24, 245–258. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.092221

Kotur, Z., Glass, A. D. M. (2015). A 150kDa plasma membrane complex of AtNRT2.5 and AtNAR2.1 is the major contributor to constitutive high-affinity nitrate influx in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Environ. 38, 1490–1502. doi: 10.1111/pce.12496

Kotur, Z., Mackenzie, N., Ramesh, S., Tyerman, S. D., Kaiser, B. N., Glass, A. D. (2012). Nitrate transport capacity of the Arabidopsis thaliana NRT2 family members and their interactions with AtNAR2.1. New Phytol. 194, 724–731. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04094.x

Krapp, A., Berthom, R., Orsel, M., Mercey-Boutet, S., Yu, A., Castaings, L., et al. (2011). Arabidopsis roots and shoots show distinct temporal adaptation patterns toward nitrogen starvation. Plant Physiol. 157, 1255–1282. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.179838

Kronzucker, H. J., Siddiqi, M. Y., Glass, A. (1995). Kinetics of NO3- influx in spruce. Plant Physiol. 109, 319–326. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.1.319

Krouk, G., Crawford, N. M., Coruzzi, G. M., Tsay, Y. F. (2010b). Nitrate signaling: adaptation to fluctuating environments. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 13, 266–273. doi: 10.1007/s11103-016-0463-x

Krouk, G., Mirowski, P., LeCun, Y., Shasha, D. E., Coruzzi, G. M. (2010a). Predictive network modeling of the high-resolution dynamic plant transcriptome in response to nitrate. Genome Biol. 11, R123. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-12-r123

Lezhneva, L., Kiba, T., Feria-Bourrellier, A. B., Lafouge, F., Boutet-Mercey, S., Zoufan, P., et al. (2014). The Arabidopsis nitrate transporter NRT2.5 plays a role in nitrate acquisition and remobilization in nitrogen-starved plants. Plant J. 80, 230–241. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12626

Li, W., He, X., Chen, Y., Jing, Y., Shen, C., Yang, J., et al. (2020). A wheat transcription factor positively sets seed vigor by regulating the grain nitrate signal. New Phytol. 225, 1667–1680. doi: 10.1111/nph.16234

Li, Y., Li, J., Yan, Y., Liu, W., Zhang, W., Gao, L., et al. (2018). Knock down of CsNRT2.1, a cucumber nitrate transporter, reduces nitrate uptake, root length, and lateral root number at low external nitrate concentration. Front. Plant Sci. 9. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00722

Linkohr, B. I., Williamson, L. C., Fitter, A. H., Leyser, H. M. O. (2002). Nitrate and phosphate availability and distribution have different effects on root system architecture of Arabidopsis. Plant J. 29, 751–760. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2002.01251.x

Lin, Y. L., Tsay, Y. F. (2017). Influence of differing nitrate and nitrogen availability on flowering control in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 68, 2603–2609. doi: 10.1093/jyb/erx053

Little, D. Y., Rao, H., Olva, S., Daniel-Vedele, F., Krapp, A., Malamy, J. E. (2005). The putative high-affinity nitrate tansporter NRT2.1 represses lateral root initiation in response to nutritional cues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 102, 13693–13698. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504219102

Liu, R., Jia, T., Cui, B., Song, J. (2020). The expression patterns and putative function of nitrate transporter 2.5 in plants. Plant Signaling Behav. 15 (12), 1815980. doi: 10.1080/15592324.2020.1815980

Li, W., Wang, Y., Okamoto, M., Crawford, N. M., Siddiqi, M. Y., Glass, A. D. M. (2007). Dissection of the AtNRT2.1:AtNRT2.2 inducible high-affinity nitrate transporter gene cluster. Plant Physiol. 143, 425–433. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.091223

Lopez-Bucio, J., Cruz-Ramirez, A., Herrera-Estrella, L. (2003). The role of nutrient availability in regulating root architecture. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 6, 280–287. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(03)00035-9

Luo, B., Xu, M., Zhao, L., Xie, P., Chen, Y., Harwood, W., et al. (2020). Overexpression of the high-affinity nitrate transporter OsNRT2.3b driven by different promoters in barley improves yield and nutrient uptake balance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 15, 21. doi: 10.3390/ijms21041320

Malolepszy, A., Mun, T., Sandal, N., Gupta, V., Dubin, M., Urbański, D. F., et al. (2016). The LORE1 insertion mutant resource. Plant J. 88, 306–317. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13243

Marchi, L., Degola, F., Polverini, E., Tercè-Laforgue, T., Dubois, F., Hirel, B., et al. (2013). Glutamate dehydrogenase isoenzyme 3 (GDH3) of Arabidopsis thaliana is regulated by a combined effect of nitrogen and cytokinin. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 73, 368–374. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2013.10.019

Misawa, F., Ito, M., Nosaki, S., Nishida, H., Watanabe, M., Suzuki, T., et al. (2022). Nitrate transport via NRT2.1 mediates NIN-LIKE PROTEIN-dependent suppression of root nodulation in lotus japonicus. Plant Cell 34, 1844–1862. doi: 10.1093/pcell/koac046

Moscatiello, R., Sello, S., Ruocco, M., Barbulova, A., Cortese, E., Nigris, S., et al. (2018). The hydrophobin HYTLO1 secreted by the biocontrol fungus Trichodrma longibrachiatum triggers a NAADP-mediated calcium signalling pathway in Lotus japonicus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, 2596–2612. doi: 10.3390/ijms19092596

Nacry, P., Bouguyon, E., Gojon, A. (2013). Nitrogen acquisition by roots: physiological and developmental mechanisms ensuring plant adaptation to a fluctuating resource. Plant Soil 370, 1–29. doi: 10.1007/s11104-013-1645-9

Naz, M., Luo, B., Guo, X., Li, B., Chen, J., Fan, X. (2019). Overexpression of nitrate transporter OsNRT2.1 enhances nitrate-dependent root elongation. Genes 9, 10. doi: 10.3390/genes10040290

Okamoto, M., Vidmar, J. J., Glass, A. D. (2003). Regulation of NRT1 and NRT2 gene families of Arabidopsis thaliana: responses to nitrate provision. Plant Cell Physiol. 44, 304–317. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcg036

Oldroyd, G. E. D., Leyser, O. (2020). A plant’s diet, surviving in a variable nutrient environment. Science 368, eaba0196. doi: 10.1126/science.aba0196

Omrane, S., Chiurazzi, M. (2009). A variety of regulatory mechanisms are involved in the nitrogen-dependent modulation of the nodule organogenesis program in legume roots. Plant Signaling Behav. 4, 1066–1068. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02873.x

Omrane, S., Ferrarini, A., D’Apuzzo, E., Rogato, A., Delledonne, M., Chiurazzi, M. (2009). Symbiotic competence in Lotus japonicus is affected by plant nitrogen status: transcriptomic identification of genes affected by a new signalling pathway. New Phytol. 183, 380–394. doi: 10.1111/J.1469-8137.2009.02873

Pajuelo, P., Pajuelo, E., Orea, A., Romero, J. M., Marquez, A. J. (2002). Influence of plant age and growth conditions on nitrate assimilation in roots of Lotus japonicus plants. Funct. Plant Biol. 29, 485–494. doi: 10.1071/PP99059

Pellizzaro, A., Clochard, T., Planchet, E., Limami, A. M., Morère-Le Paven, M. C. (2015). Identification and molecular characterization of Medicago truncatula NRT2 and NAR2 families. Physiologia plantarum 154, 256–269. doi: 10.1111/ppl.12314

Plett, D., Toubia, J., Garnett, T., Tesster, M., Kaiser, B. N., Baumann, U. (2010). Dichotomy in the NRT gene families of dicots and grass species. PloS One 5, e15289. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015289

Remans, T., Nacry, P., Pervent, M., Filleur, S., Diatloff, E. (2006). The arabidopsis NRT1.1 transporter participates in the signaling pathway triggering root colonization of nitrate-rich patches. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 19206–19211. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.075721

Rogato, A., D’Apuzzo, E., Barbulova, A., Omrane, S., Stedel, K., Simon-Rosin, U., et al. (2008). Tissue-specific down-regulation of LjAMT1;1 compromises nodule function and enhances nodulation in lotus japonicus. Plant Mol. Biol. 68, 585–595. doi: 10.1007/s11103-008-9394-5

Rogato, A., Valkov, T. V., Alves, L. M., Apone, F., Colucci, G., Chiurazzi, M. (2016). Down-regulated Lotus japonicus GCR1 plants exhibit nodulation signalling pathways alteration. Plant Sci. 247, 71–82. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2016.03.007

Ruffel, S., Krouk, G., Ristova, D., Shasha, D., Birnbaum, K. D., Coruzzi, G. M. (2011). Nitrogen economics of root foraging: transitive closure of the nitrate-cytokinin relay and distinct systemic signaling for n supply vs. demand. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 18524–18529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108684108

Sabermanesh, K., Holtham, L. R., George, J., Roessner, U., Boughton, B., Heuer, S., et al. (2017). Transition from a maternal to external nitrogen source in maize seedlings. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 59, 261–274. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12525

Safi, A., Medici, A., Szponarski, W., Martin, F., Clèment-Vidal, A., Marshall-Colon, A., et al. (2021). GARP transcription factors repress Arabidopsis nitrogen starvation response via ROS-dependent and -independent pathways. J. Exp. Bot. 72, 3881–3901. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erab114

Safi, A., Medici, A., Szponarski, W., Ruffel, S., Lacombe, B., Krouk, G. (2017). The world according to GARP transcription factors. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 39, 159–167. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2017.07.006

Santi, C., von Groll, U., Ribeiro, A., Chiurazzi, M., Auguy, F., Bogusz, D., et al. (2003). Comparison of nodule induction in legume and actinorhizal symbioses: The induction of actinorhizal nodules does not involve ENOD40. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 16, 808–816. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2003.16.9.808

Schneider, C. A., Rasband, W. S., Eliceiri, K. W. (2012). NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089

Siddiqi, M. Y., Glass, A. D. M., Ruth, T. J., Rufty, T. W. (1990). Studies of the uptake of nitrate in barley: 1. kinetics of NO-13(3)-influx. Plant Physiol. 93, 1426–1432. doi: 10.1104/pp.93.4.1426

Sol, S., Valkov, V. T., Rogato, A., Noguero, M., Gargiulo, L., Mele, G., et al. (2019). Disruption of the Lotus japonicus transporter LjNPF2.9 increases shoot biomass and nitrate content without affecting symbiotic performances. BMC Plant Biol. 19, 380. doi: 10.1186/s12870-019-1978-5

Stougaard, J., Abildsten, D., Marcker, K. A. (1987). The Agrobacterium rhizogenes pRi TL-DNA segment as a gene vector system for transformation of plants. Mol. Gen. Genet. 207, 251–255. doi: 10.1007/BF00331586

Tang, Z., Fan, X., Li, Q., Feng, H., Iller, A. J., Shen, Q., et al. (2012). Knockdown of a rice stelar nitrate transporter alters long-distance translocation but not root influx. Plant Physiol. 160, 2052–2063. doi: 10.1104/pp112.204461

Tusnády, G. E., Simon, I. (2001). The HMMTOP transmembrane topology prediction server. Bioinformatics 17, 849–850. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.9.849

Urbanski, D. F., Małolepszy, A., Stougaard, J., Andersen, S. U. (2012). Genome-wide LORE1 retrotransposon mutagenesis and high-throughput insertion detection in Lotus japonicus. Plant J. 69, 731–741. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04827.x

Valkov, T. V., Chiurazzi, M. (2014). “Nitrate transport and signaling,” in The lotus japonicus genome, compendium of plant genomes. Eds. Tabata, S., Stougaard, J. (Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag), 125–136. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-44270-8

Valkov, T. V., Rogato, A., Alves, L. M., Sol, S., Noguero, M., Léran, S., et al. (2017). The nitrate transporter family protein LjNPF8.6 controls the n-fixing nodule activity. Plant Physiol. 175, 1269–1282. doi: 10.1104/pp.17.01187

Valkov, T. V., Sol, S., Rogato, A., Chiurazzi, M. (2020). The functional characterization of LjNRT2.4 indicates a novel positive role of nitrate for an efficient nodule N2-fixation activity. New Phytol. 228, 682–696. doi: 10.1111/nph.16728

Wang, Y. Y., Cheng, Y. H., Chen, Y. E., Tsay, W. F. (2018). Nitrate transport, signaling, and use efficiency. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 69, 27.1–27.38. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042817-

Wang, Y. Y., Hsu, P. K., Tsay, Y. F. (2012). Uptake, allocation and signaling of nitrate. Trends Plant Sci. 17, 458–467. doi: 10.1016/j.plants.2012.04.006

Wang, Q., Huang, Y., Ren, Z., Zhang, X., Ren, J., Su, J., et al. (2020). Transfer cells mediate nitrate uptake to control root nodule symbiosis. Nat. Plants 6, 800–808. doi: 10.1038/s41477-020-0683-6

Wang, R., Tischner, R., Gutierrez, R. A., Hoffman, M., Xing, X., Chen, M., et al. (2004). Genomic analysis of the nitrate response using a nitrate reductase-null mutant of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 136, 2512–2522. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.044610

Wei, J., Zheng, Y., Feng, H., Qu, H., Fan, X., Yamaji, N., et al. (2018). OsNRT2.4 encodes a dual-affinity nitrate transporter and functions in nitrate-regulated root growth and nitrate distribution in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 69, 1095–1107. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erx486

Xu, G., Fan, X., Miller, A. J. (2012). Plant nitrogen assimilation and use efficiency. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 63, 153–182. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042811-105532

Yendrek, C. R., Lee, Y. C., Morris, V., Liang, Y., Pislariu, C. I., Burkart, G., et al. (2010). A putative transporter is essential for integrating nutrient and hormone signaling with lateral root growth and nodule development in Medicago truncatula. Plant J. 62, 100–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04134.x

You, H. G., Liu, Y. M., Minh, T. N., Lu, H. R., Zhang, P. M., Li, W. F., et al. (2020). Genome-wide identification and expression analyses of nitrate transporter family genes in wild soybean (Glycine soja). J. Appl. Genet. 61, 489–501. doi: 10.1007/s13553-020-00571-7

Zamboni, A., Astolfi, S., Zuchi, S., Pii, Y., Guardini, K., Tononi, P., et al. (2014). Nitrate induction triggers different transcriptional changes in a high and a low nitrogen use efficiency maize inbred line. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 56, 1080–1094. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12214

Zhang, H. M., Forde, B. G. (1998). An Arabidopsis MADS box gene that controls nutrient-induced changes in root architecture. Science 279, 407–409. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5349.407

Zhang, H. M., Jennings, A., Barlow, P. W., Forde, B. G. (1999). Dual pathways for regulation of root branching by nitrate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 96, 6529–6534. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6529

Zoghbi-Rodrìguez, N. M., Gamboa-Tuz, S. D., Pereira-Santana, A., Rodrìguez-Zapata, L. C., Sanchez-Teyer, L. F., Echavarrìa-Machado, I. (2021). Phylogenomic and microsyntheny analysis provides evidence of genome arrangements of high-affinity nitrate transporter gene families of plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 13036. doi: 10.3390/ijms222313036

Keywords: nitrate, transporters, NRT2, root architecture, response to nitrogen starvation

Citation: Rogato A, Valkov VT and Chiurazzi M (2022) LjNRT2.3 plays a hierarchical role in the control of high affinity transport system for root nitrate acquisition in Lotus japonicus. Front. Plant Sci. 13:1042513. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.1042513

Received: 12 September 2022; Accepted: 25 October 2022;

Published: 10 November 2022.

Edited by:

Anis M. Limami, Université d’Angers, FranceReviewed by:

Marie-Christine Morère-Le Paven, Université d’Angers, FranceCopyright © 2022 Rogato, Valkov and Chiurazzi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Maurizio Chiurazzi, TWF1cml6aW8uY2hpdXJhenppQGliYnIuY25yLml0

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

‡ORCID: Alessandra Rogato, orcid.org/0000-0002-0373-9076

Vladimir Totev Valkov, orcid.org/0000-0002-3811-0913

Maurizio Chiurazzi, orcid.org/0000-0003-2023-9572

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.