- 1College of Forestry, Shenyang Agricultural University, Shenyang, Liaoning, China

- 2The Key Laboratory of Forest Tree Genetics, Breeding and Cultivation of Liaoning Province, Shenyang Agricultural University, Shenyang, Liaoning, China

Previously, we have shown that the transcription factor BplMYB46 in Betula platyphylla can enhance tolerance to salt and osmotic stress and promote secondary cell wall deposition, and we characterized its downstream regulatory mechanism. However, its upstream regulatory mechanism remains unclear. Here, the promoter activity and upstream regulatory factors of BplMYB46 were studied. Analyses of β-glucuronidase (GUS) staining and activity indicated that BplMYB46 promoter was specific temporal and spatial expression, and its expression can be induced by salt and osmotic stress. We identified three upstream regulatory factors of BplMYB46: BpDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpbZIP3. Yeast-one hybrid assays, GUS activity, chromatin immunoprecipitation, and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction revealed that BpDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpbZIP3 can directly regulate the expression of BplMYB46 by specifically binding to Dof, W-box, and ABRE elements in the BplMYB46 promoter, respectively. BpDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpbZIP3 were all localized to the nucleus, and their expressions can be induced by stress. Overexpression of BpDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpbZIP3 conferred the resistance of transgenic birch plants to salt and osmotic stress. Our findings provide new insights into the upstream regulatory mechanism of BplMYB46 and reveal new upstream regulatory genes that mediate resistance to adverse environments. The genes identified in our study provide novel targets for the breeding of forest tree species.

Introduction

Plants are sessile organisms that are continually exposed to different types of abiotic and biotic stress, and they possess various mechanisms to cope with adverse environmental conditions and resist attack by other organisms (Hickman et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2019; Iqbal et al., 2021). Several genes are involved in the regulation of stress responses. Transcription factors (TFs) can bind to specific cis-acting elements on promoters to control the expression of various target genes; they thus play important roles in the growth and development of plants (Franco-Zorrilla and Solano, 2017; Wang et al., 2021a).

The MYB family is one of the largest families of TFs in plants; MYB TFs play key roles in primary and secondary metabolism and regulate resistance to biotic and abiotic stresses and other physiological processes in plants (Mitra et al., 2019; Berardi et al., 2021; Xiao et al., 2021; Cao et al., 2022). Over expression of MYB6 in transgenic poplar up-regulates the expression of flavonoid biosynthesis genes and significantly increases the accumulation of anthocyanins and proanthocyanidins in Populus tomentosa (Wang et al., 2019). MdMYB308L positively regulates the accumulation of anthocyanins and cold tolerance in apple (An et al., 2020). BpMYB4 promotes stem development and cellulose biosynthesis and regulates tolerance to abiotic stress in birch (Yu et al., 2021). Overexpression of MbMYB108 from Malus baccata enhances resistance to cold and drought stress in transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana plants (Yao et al., 2022). Some studies have shown that MYB TFs can regulate the expression of target genes and affect the response to various signals in plants (Xue et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2022b). For example, PavMYB10.1 in sweet cherry regulates the expression of PavANS and PavUFGT by binding to the AE-box, a light response element in their promoters, and promotes anthocyanin synthesis (Jin et al., 2016). Yeast-one hybrid (Y1H) assays and electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) have shown that CiMYB42 regulates the expression of CiOSC by binding to the MYB core element in its promoter to positively regulate limonoid biosynthesis in citrus (Zhang et al., 2020). MYB21 plays a key role in regulating flavonol biosynthesis by directly binding to the GARE cis-acting element in the FLS1 promoter in A. thaliana (Zhang et al., 2021). MdMYB2 directly binds to the MBS motif in the SUMO E3 ligase MdSIZ1 promoter and activates the expression of MdSIZ1, which affects cold tolerance and the accumulation of anthocyanins in apple (Jiang et al., 2022). PnMYB2 in Panax notoginseng binds to the promoters of PnCesA3 and PnCCoAOMT1 to regulate their expression; these genes promote primary cell wall (PCW) and secondary cell wall (SCW) biosynthesis by enhancing cellulose and lignin biosynthesis (Shi et al., 2022). Although the downstream regulatory mechanisms of MYB TFs have been well studied, the upstream regulatory mechanisms of MYB TFs have been less well studied by comparison. The upstream regulators of TFs mediate the responses to various signals. Given that upstream regulators of TFs have global effects in transcriptional regulation, additional studies are needed to clarify the upstream regulatory mechanisms of TFs.

Previously, we have shown that BplMYB46 in Betula platyphylla (birch), a pioneer species of secondary forests in northeastern China, enhances tolerance to salt and osmotic stress and promotes SCW deposition; we have also characterized its downstream regulatory mechanism (Guo et al., 2017; Guo et al., 2018). However, its upstream regulatory mechanism remains unclear. Here, the promoter activity and upstream regulatory factors of BplMYB46 were analyzed. We also studied the functions of the upstream regulatory factors of BplMYB46. The results of our study provide new insights into the upstream regulatory mechanism of BplMYB46. Our findings will also aid the discovery of novel upstream regulatory genes that promote resistance to adverse environments and provide targets for the breeding of new forest tree species.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

The stems and leaves of birch were cut into small pieces and incubated on woody plant medium (WPM + 0.5 mg/L 6-BA + 0.5 mg/L KT). After the calli regenerated, they were transferred to growth medium (WPM + 1.0 mg/L 6-BA) for bud differentiation. Adventitious buds with 3–5-cm shoots were cut and transferred to root generation medium (WPM + 0.2 mg/L NAA) in a growth chamber with a 12 h/12 h light/dark cycle, an average temperature of 26°C, and 70–75% relative humidity.

Birch seeds were cultivated on Woody Plant Medium (WPM with 2.5% (w/v) sucrose and 0.6% (w/v) agar (pH 5.8) in a growth chamber and then planted in pots containing a mixture of perlite/vermiculite/soil (1:1:3) in a greenhouse. Conditions in the growth chamber were as follows: 12 h/12 h light/dark cycle, average temperature of 26°C, and 70–75% relative humidity. The plants were thoroughly watered every day.

Plasmid construct and plant transformation

Genomic DNA was extracted from B. platyphylla using the CTAB method (Cheng et al., 2003). A 1,443-bp sequence of the BplMYB46 promoter excluding 5’ untranslated region (UTR) was amplified and then cloned into the pCAMBIA1301 vector to replace the cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) 35S promoter driving the beta-glucuronidase (GUS) gene. The primers used are listed in Table S1. The BplMYB46 promoter::GUS construct was electroporated into Agrobacterium competent cells (EHA105) and then transformed into B. platyphylla using the Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transient transformation method well applied in herbaceous and woody plants (Zang et al., 2017; Hu et al., 2019), according to a previous protocol (Ji et al., 2014) with some modifications. Briefly, single colony of A. tumefaciens strain EHA105 harboring BplMYB46 promoter::GUS was grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) liquid medium (containing 50 mg/L kanamycin and 50 mg/L rifampicin) at 28°C with shaking. After overnight incubation, 1ml of culture was transferred to 50 ml of fresh LB liquid media and incubated at 28°C with shaking. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 3,000 rpm for 10 min when the culture density reached an OD600 of 0.5–0.6, and were resuspended in the transformation solution (1/2 MS + sucrose [2.0%, w/v] + 10 mM CaCl2 + 120 μM acetosyringone + 200 mg/L DTT + Tween-20 [0.02%, v/v], pH 5.8] as the transformation solution for the transformation study. For transient genetic transformation, the birch plants at different developmental stages were soaked in the transformation solution and shaken at 120 rpm and 25°C in the dark. After 24 h, the birch samples were collected.

GUS staining and activity analysis

The birch plants of BplMYB46 promoter::GUS transient genetic transformation, including 5-day-old seedlings, 10-day-old seedlings, 14-day-old seedlings, 30-day-old seedlings, and mature leaves of 45-day-old seedlings were collected. Next, β-glucuronidase (GUS) staining was performed according to previous method (Zheng et al., 2012). The BplMYB46 promoter::GUS transient transgenic birch plants for one-month-old were watered with 150 mM NaCl or 200 mM mannitol solution for 6, 12, and 24 h. Specifically, taking 24 h as the final treatment time point, 6 h and 12 h treatments were carried out backwards. The control plants were watered for 24 h with water. All birch plants were collected at the 24th h, then were homogenized in GUS extraction buffer. The supernatant was assayed for GUS activity with 4-methylumbellifery-β-d-glucuronic acid as the substrate; fluorescence values were measured using 4-methylumbelliferon as the calibration control. The activity of GUS was determined using previously published method (Gampala et al., 2001). Data were shown as the mean of three biological replicates.

Identification of the upstream regulatory factors of BplMYB46 using Y1H assays

The total RNA of one-month-old birch plants was extracted. The cDNA library was obtained via the Matchmaker® Gold Yeast One-Hybrid Library Construction & Screening Kit (Clontech) and used as the effector construct. The BplMYB46 promoter was inserted into multiple cloning sites of the pHIS2 plasmid (EcoR I and Sac I) to drive HIS3 expression and used as the reporter construct. The primers used are shown in Table S2.

The cDNA library (effector) and BplMYB46 promoter (reporter) were co-transformed into Y187 yeast cells using the Y1H technique. The Y1H system consisted of the following: 3 µg of Sma I-linearized pGADT7-Rec2, 2–5 µg of cDNA library, 5 µg of reporter construct, and 20 µL of carrier DNA. The mixture was added to 600 μL of competent Y187 yeast cells. The transformation was performed using the Yeast Transformation System 2 (Clontech). The Y187 construct was grown on SD/-Trp/-His/(DDO) and SD/-Trp/-His/-Leu/(TDO), and TDO contained 50 mM 3-AT (3-amino-1, 2, 4-triazole) medium. The yeast plasmids were extracted from monoclonal colonies cultured on TDO medium with 50 mM 3-AT using the Easy Yeast Plasmid Isolation Kit (Clontech); they were then transformed into Escherichia coli DH5α competent cells through heat shock and cultured on LB medium containing ampicillin to identify the TFs that bind to the promoter sequence of BplMYB46. Positive clones were detected via PCR (primers are shown in Table S3) and were sequenced.

Y1H verification

The truncated BplMYB46 promoter with and without Dof, W-box, and ABRE cis-acting elements; the three tandem copies of DNA sequences of the Dof, W-box, and ABRE cis-acting elements; the three tandem copies of mutated DNA sequences (A/T was mutated to C, G/C was mutated to A) of the Dof, W-box, and ABRE were cloned into the pHIS2 vector and used as reporters. Primers used and sizes of amplicons are shown in Table S4. The pGADT7-Rec2-BpDof1, pGADT7-Rec2-BpWRKY3, and pGADT7-Rec2-BpbZIP3 constructs were used as effectors. The effectors and their corresponding reporters were co-transformed into yeast cells (Y187) and selected on TDO medium containing 50 mM 3-AT. The positive control was the interaction between pGADT7-Rec2-p53 and pHIS2-p53. The negative control was the interaction between pGADT7-Rec2-p53 and pHIS2-BplMYB46 promoter.

ChIP analysis

The open reading frames (ORFs) of BpDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpbZIP3, without the termination codon, were separately inserted into the vector pBI121 upstream of green fluorescent protein (GFP) under the control of the CaMV 35S promoter. The pBI121-35S::BpDof1-GFP, pBI121-35S::BpWRKY3-GFP and pBI121-35S::BpbZIP3-GFP construct was transformed into Agrobacterium EHA105 competent cells and then into the one-month-old birch plants by A. tumefaciens-mediated transient transformation, respectively. To determine whether the upstream regulators could bind to specific cis-acting elements of the BplMYB46 promoter to regulate its expression in vivo, ChIP analysis was conducted following a previously described method (Zhao et al., 2020) with some modifications. Briefly, transgenic birch plants (1–5 g) transiently expressing BplDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpbZIP3 were collected and crosslinked with 3% formaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature in a vacuum. The cross-linking was quenched by 2 mol/L glycine for 2 min in a vacuum at room temperature, followed by five washes with deionized water. Tissue was then ground into a fine powder using liquid nitrogen. The purified cross-linked nuclei were sonicated to shear the chromatin into 0.2–0.8 kb fragments, and 1/10 volume was saved as the input control. One portion of chromatin was immunoprecipitated with GFP antibody (ChIP+). The other portion was immunoprecipitated without antibody as a negative control (ChIP−). The immunoprecipitated complexes were incubated at 65°C for 12 h to release the DNA fragments. The immunoprecipitated DNA was extracted with chloroform for purification. The DNA fragments containing or lacking Dof, W-box, and ABRE elements in the BplMYB46 promoter region were selected for amplification. The thermal cycling conditions for PCR were as follows: 95°C for 5 min; 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 56°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s; and a final incubation at 72°C for 7 min. Enrichment of truncated promoters in the immunoprecipitated samples was determined by quantitative PCR (qPCR). The thermal cycling protocol was as follows: 95°C for 30 s; 40 cycles at 95°C for 10 s, 55°C for 10 s, and 72°C for 30 s; and 60°C for 15 s for plate reading. The tubulin gene was used as an internal control. Three biological replicates were conducted. All the primers used are shown in Table S5.

Validation by transient expression assay

The binding ability of upstream regulatory factor to the specific element in BplMYB46 promoter was validated using the GUS reporter gene assay. The truncated promoter including or lacking the Dof, W-box or ABRE elements was fused with the CaMV 35S minimal promoter (46 bp to +1, replaced 35S promoter) to drive the GUS gene. BpDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpbZIP3 was inserted into the pROKII vector under the control of the CaMV 35S promoter and used as effector, respectively. Each effector of pROKII-35S::BpDof1, pROKII-35S::BpWRKY3 and pROKII-35S::BpbZIP3 was co-transformed with each reporter into one-month-old birch plants by Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transient expression. The GUS activity was determined. Data are represented as the mean of three biological replicates. The primers are listed in Tables S6.

Expression analysis of BplMYB46

To determine whether the upstream regulatory factors can regulate the expression of BplMYB46, each effector of pROKII-35S::BpDof1, pROKII-35S::BpWRKY3 and pROKII-35S::BpbZIP3 was transformed into the one-month-old birch plants using the transient transformation method. The RNA was extracted using a Universal Plant RNA Extraction Kit (BioTeke Corporation, China). The cDNA was synthesized from approximately 1 μg of total RNA using PrimeScript IV First-Strand cDNA Synthesis Mix (TaKaRa, Japan). Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) of BplMYB46 was conducted with 10 μL of SYBR Green Real-time PCR Master Mix (BioTake Corporation, China), 1 μL of cDNA template, 1 μL of forward primer (10 μM), and 1 µL of reverse primer (10 μM); the final reaction volume was adjusted to 20 µL with ultrapure water. The thermal cycling conditions were as follows: 94°C for 30 s; 94°C for 12 s, 58°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 45 s for 45 cycles; and 79°C for 1 s for plate reading using a qTOWER3 G system (Analytik Jena AG, Germany). After the final PCR cycle, the temperature was increased from 55°C to 99°C at 0.5°C per s to generate the melting curve for the samples. Three independent experiments were performed. The tubulin (GenBank accession number: FG067376) and ubiquitin (GenBank accession number: FG065618) genes were used as internal controls. All primers and amplicon sizes are shown in Table S7. The expression of BplMYB46 for each sample was calculated using the delta-delta CT method (Pfaffl et al., 2002).

Subcellular localization analysis of upstream regulatory factors

The pBI121-gene-GFPs and pBI121-GFP (control) were separately transformed into onion epidermal cells using particle bombardment (BioRad). After incubation on 1/2MS medium for 24 h in the dark, the transformed onion epidermal cells were stained with DAPI (100 ng/mL) and visualized under a confocal laser-scanning microscope (A1, Nikon, Japan).

qRT-PCR analysis of upstream regulatory factors

After approximately 2 months of cultivation, healthy birch seedlings approximately 25 cm in height with similar growth conditions were treated with 200 mM NaCl or 300 mM mannitol for 0.5, 12, 24, and 48 h. Specifically, taking 48 h as the final treatment time point, 0.5 h, 12 h and 24 h treatments were carried out backwards. The control plants were treated with fresh water for 48 h. The birch seedlings were collected at the 48th h. Three independent biological replicates were conducted, and each replicate comprised six seedlings. All samples were quickly frozen using liquid nitrogen and stored at –80°C.

Total RNA was extracted and treated with DNase I; it was then reverse-transcribed into cDNA using the PrimeScript™ RT reagent Kit (Takara). qRT-PCR was performed for BpDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpbZIP3. The primers and amplicon sizes of the genes are shown in Table S8. All the procedures and parameters for qRT-PCR were the same as those described above.

Stress tolerance analyses of plants overexpressing upstream regulatory factors

The pROKII-35S::gene and pROKII-35S empty vector were separately transformed into one-month-old birch seedlings using the transient transformation method. The transient transgenic plants were treated with 150 mM NaCl or 200 mM mannitol for 12 h. Control plants were treated with water. The detached leaves of birch plants were incubated with 0.5 mg/mL nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT, dissolved in phosphate buffer, pH 7.8) and 0.5 mg/mL 3’-diaminobenzidine (DAB, dissolved in phosphate buffer, pH 3.8) as described in a previous study (Zhang et al., 2011). Evans blue (1.0 mg/mL, dissolved in sterile deionized water) staining was conducted to detect cell death following previously published procedures (Kim et al., 2003). The activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and peroxidase (POD), the content of H2O2, and electrolyte leakage were measured following previously described methods (Liu et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2015). The concentration of protein in plants was detected using a kit produced by Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute. Three independent biological replicates were conducted.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted in SPSS software (IBM, IL, USA), and analysis of variance was used to evaluate the significance of differences between groups. The threshold for statistical significance was P <0.05.

Results

The temporal and spatial expression of BplMYB46 promoter

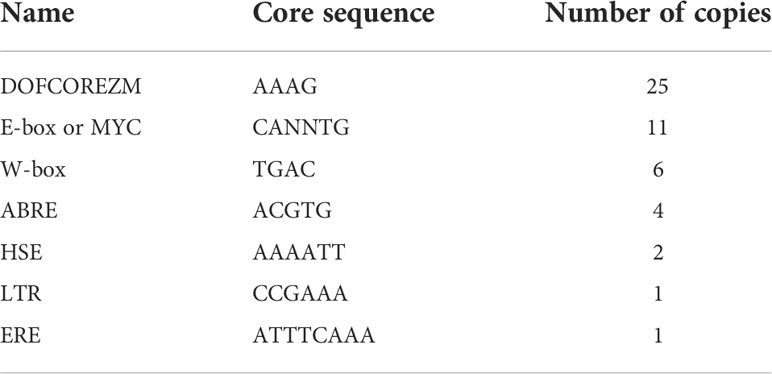

The BplMYB46 promoter::GUS construct was transiently transformed into birch plants using A. tumefaciens-mediated transformation. The expression pattern of BplMYB46 promoter in birch was performed via GUS staining (Figure 1). GUS activity was detected at every developmental stage and in almost all tissues of birch plants. At the initial developmental stage of birch seedlings, GUS activity of the hypocotyls was higher than that of the cotyledons (Figure 1A). Interestingly, GUS activity of the leaves and roots was higher than that of the stems, with the continuous development of birch seedlings (Figures 1B, C). Moreover, GUS activity was much higher in old leaves than in young leaves (Figures 1D, E), and GUS activity of the leaf veins was higher than the rest of the leaf (Figure 1E). Our findings suggest that BplMYB46 promoter have the temporal and spatial expression specificity.

Figure 1 The temporal and spatial expression of BplMYB46 promoter in transient transgenic BplMYB46 promoter::GUS birch plants. The BplMYB46 promoter::GUS construct was transformed into birch plants and β-glucuronidase (GUS) histochemical staining was performed to investigate the temporal and spatial expression of BplMYB46 promoter. (A) 5-day-old seedling; (B) 10-day-old seedling; (C) 14-day-old seedling; (D) 30-day-old seedling; (E) mature leaf of 45-day-old seedling.

BplMYB46 promoter activity under abiotic stress

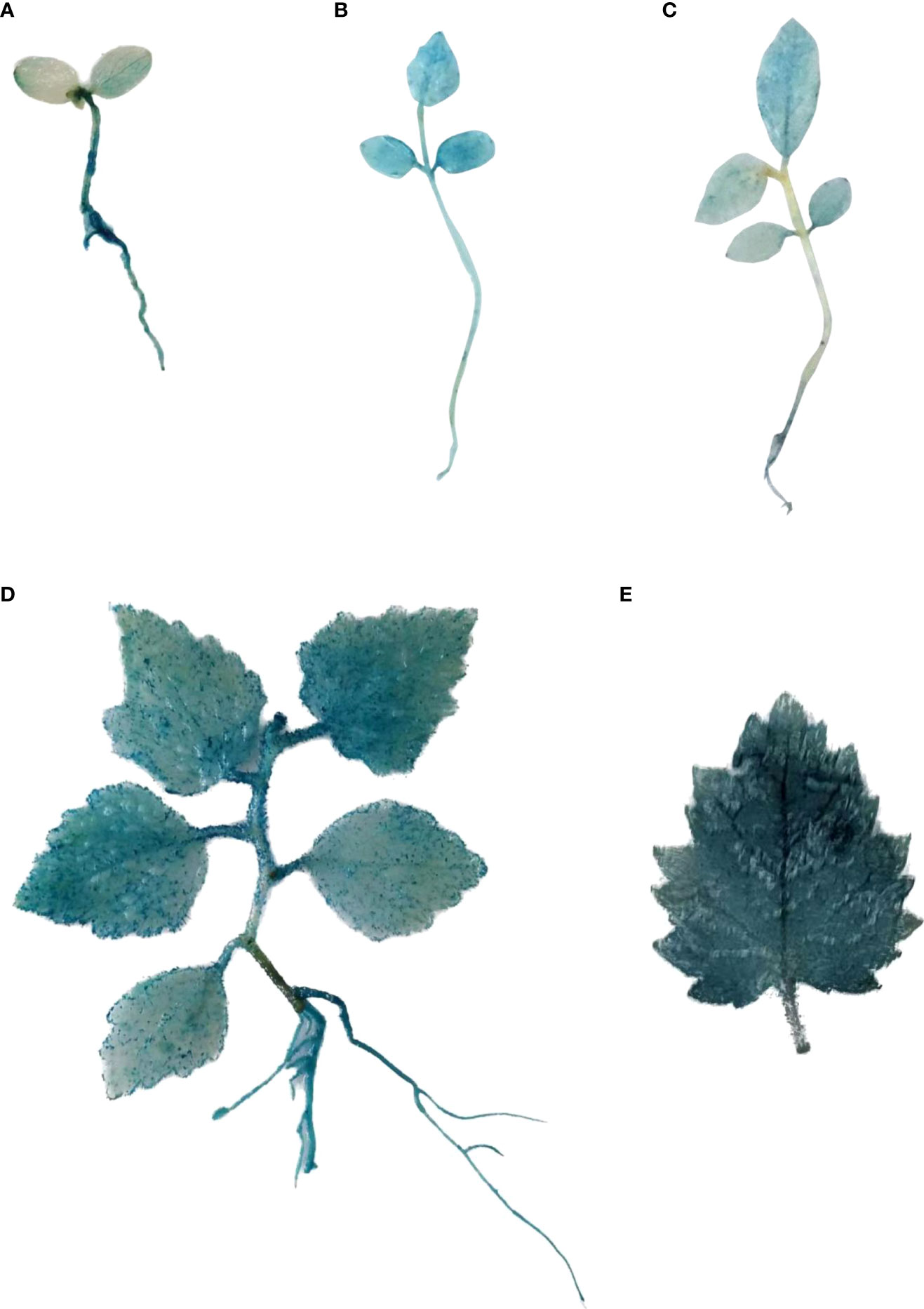

To clarify the roles of the BplMYB46 promoter in response to stress, transient transgenic BplMYB46 promoter::GUS birch plants were exposed to salt and osmotic stress for different lengths of time, and the relative GUS activity was determined (Figure 2). Our results showed that GUS activity was up-regulated under salt and osmotic stress compared with the control. Specifically, GUS activity increased from 6 h to 24 h under salt treatment; under osmotic treatment, GUS activity first increased from 6 h to 12 h and then decreased from 12 h to 24 h. Our findings suggested that the BplMYB46 promoter can respond to abiotic stress and that its expression can be induced by salt and osmotic treatment in vivo.

Figure 2 Relative activity of GUS in transient transgenic BplMYB46 promoter::GUS birch plants under salt and osmotic stress. Relative activity of GUS under salt stress of 150 mM NaCl and osmotic stress of 200 mM mannitol for 6 h, 12h and 24 h. BplMYB46 promoter::GUS construct was transformed into one-month-old birch plants using the Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transient transformation method. The relative activity of GUS mean that the relative level of GUS in transient transgenic BplMYB46 promoter::GUS birch plants under salt and osmotic stress, compared with that in transient transgenic BplMYB46 promoter::GUS birch plants under water treatment. Error bars indicate the standard deviation of three biological replicates.

Analysis of the cis-acting elements of BplMYB46 promoter

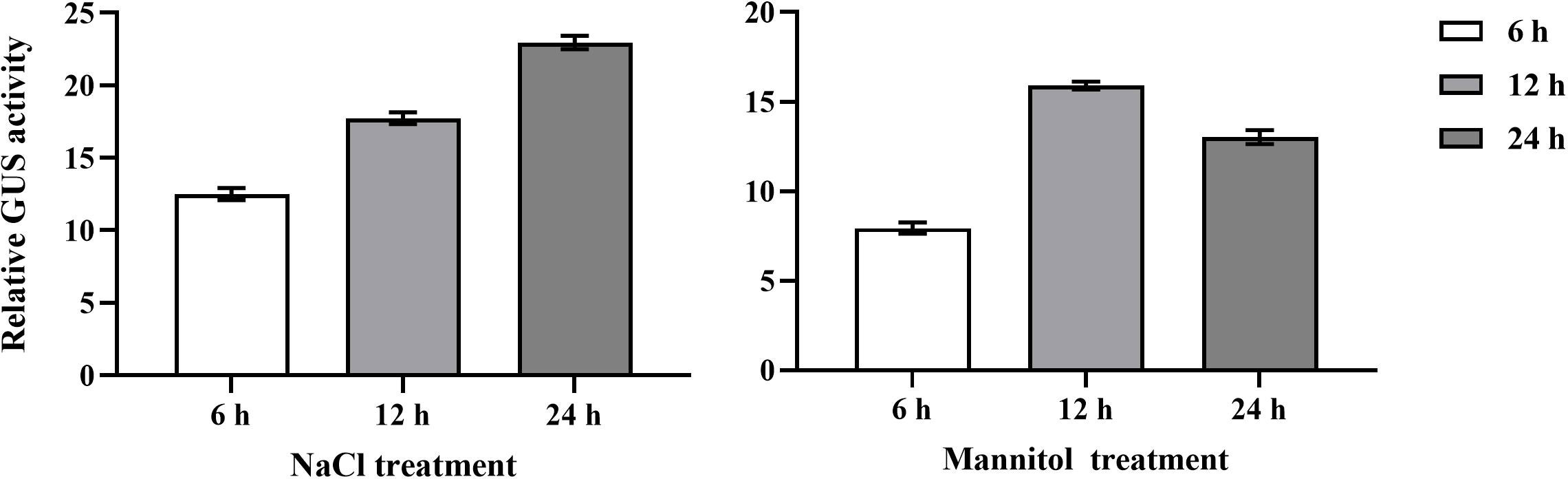

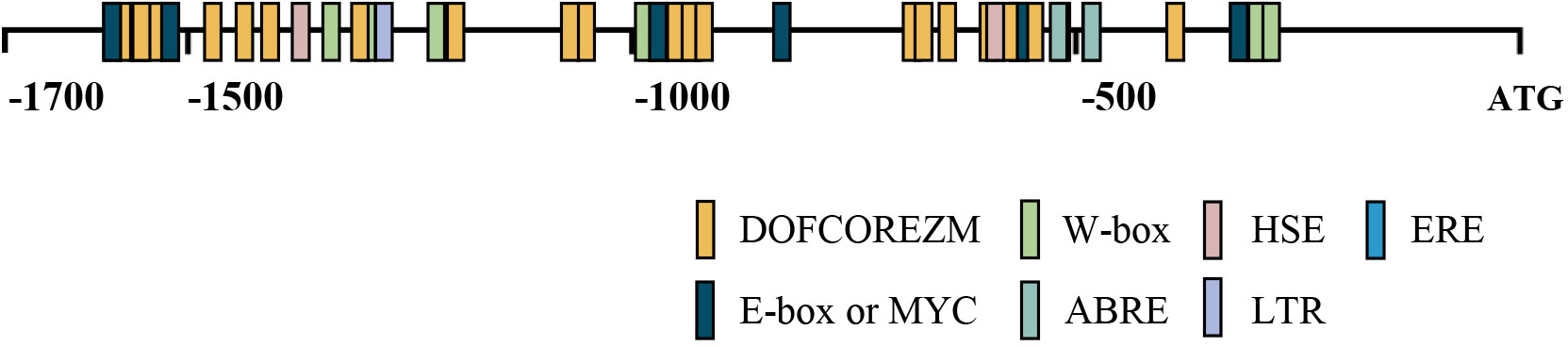

The cisacting elements in the promoter sequence of BplMYB46 excluding 5’ UTR were predicted using the PlantCARE database. Some cisacting elements in BplMYB46 promoter were identified (Figure 3), including DOFCOREZM, E-box/MYC, W-box, ABRE, HSE, LTR, and ERE elements, which are involved in abiotic stress, light, abscisic acid, and ethylene responsiveness. In them, DOFCOREZM, E-box/MYC, W-box and ABRE were the more abundant cisacting elements than the rest elements (Table 1).

Figure 3 Distribution of cis-acting elements in BplMYB46 promoter. The 7 different cis-acting elements in the promoter of BplMYB46 gene are represented in different color boxes.

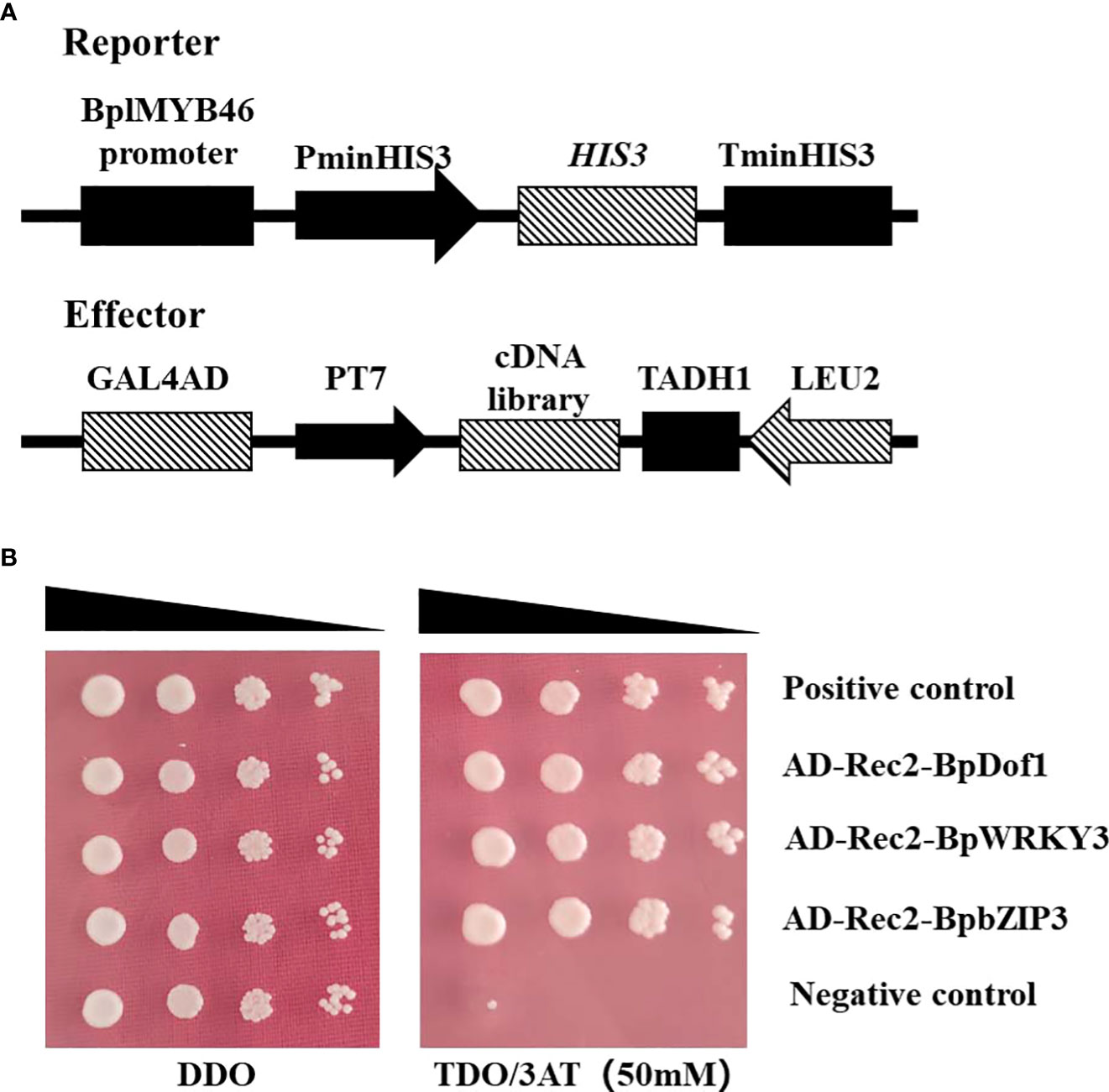

Identification of the upstream regulatory factors of BplMYB46

To identify upstream regulatory factors, the BplMYB46 promoter was cloned into the pHIS2 vector, which was used as a reporter, and co-transformed into Y187 yeast cells with the cDNA library of birch plants for Y1H analysis (Figure 4A). The yeast plasmids were extracted from monoclonal colonies cultured on TDO medium containing 50 mM 3-AT and then were transformed into E. coli DH5α. The positive clones were screened on LB medium with ampicillin and then were sequenced. We identified a total of three upstream regulatory factors, BpDof1 (GenBank number: MT075779), BpWRKY3 (GenBank number: OP265743), and BpbZIP3 (GenBank number: OP265744), according to the BLAST sequence analysis tool on the NCBI website (Figure 4B).

Figure 4 Three regulatory factors that bound to the BplMYB46 promoter were identified from the birch cDNA library via Y1H analysis. (A) Schematic diagram of the effector and reporter used in the Y1H analysis. (B) Verification of the birch cDNA library (effector) and the BplMYB46 promoter (reporter) constructs co-transformed into yeast Y187 cells. The positive transformants were determined by spotting the serial dilutions (1:1, 1:10, 1:100, and 1:1000) of yeast onto DDO and TDO plates with 3-AT. Positive control: pGADT7-p53/pHIS2-p53; Negative control: pGADT7-p53/pHIS2-BplMYB46 promoter.

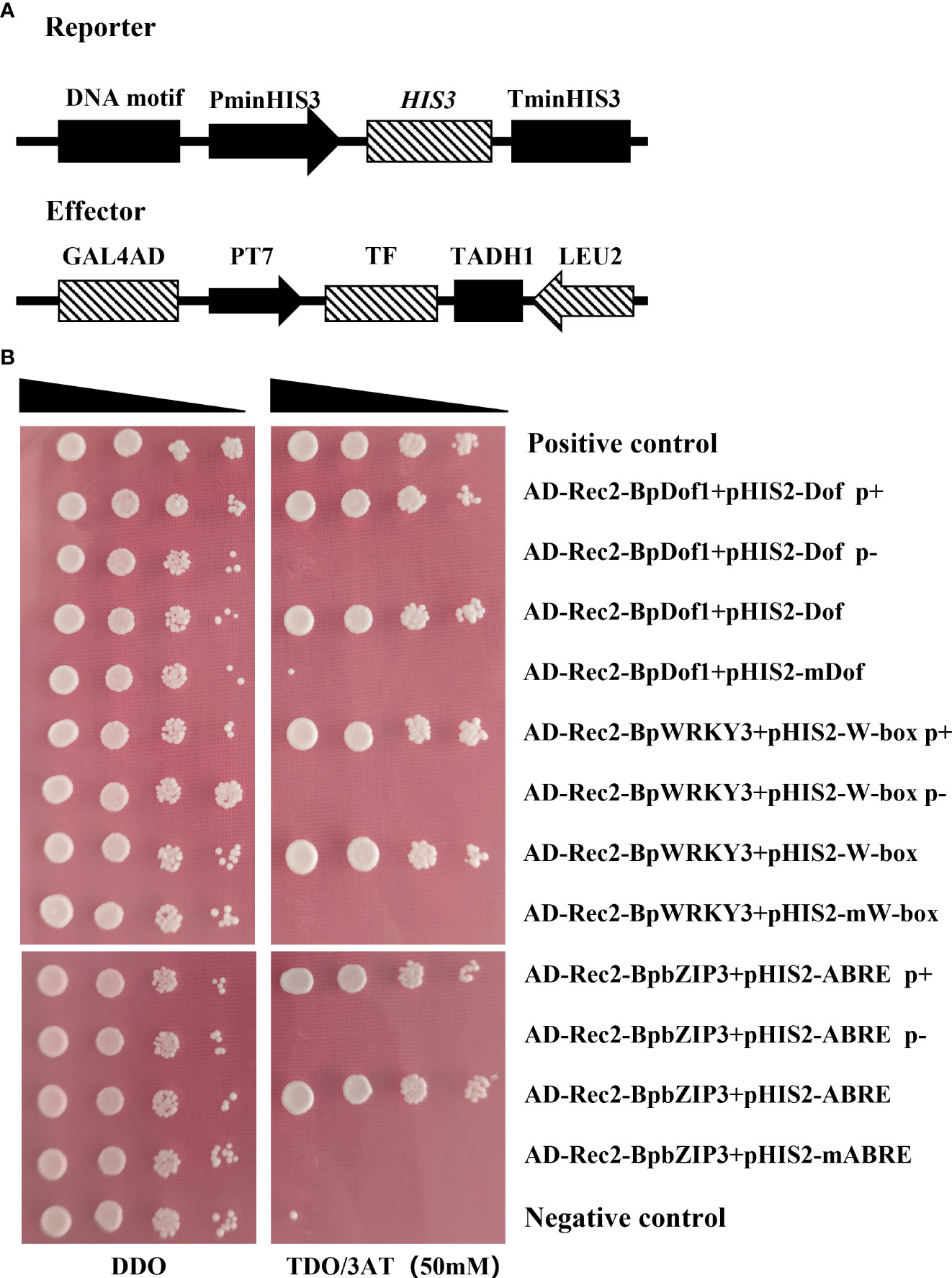

Analysis of the interaction between regulatory factors and specific elements

The interactions of BpDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpbZIP3 effectors with the truncated BplMYB46 promoter with and without Dof, W-box, and ABRE elements; with three tandem copies of Dof, W-box, and ABRE elements; and with their mutated sequences were analyzed using Y1H assays (Figure 5A). BpDof1, BpWRKY3 and BpbZIP3 bound to the truncated BplMYB46 promoter containing Dof, W-box, and ABRE elements and three tandem copies of Dof, W-box, and ABRE elements but failed to bind to the truncated BplMYB46 promoter lacking Dof, W-box, and ABRE elements and three tandem copies of mutated Dof, W-box, and ABRE elements (Figure 5B). Our results further indicated that BpDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpbZIP3 can specifically bind to the Dof, W-box, and ABRE elements, respectively.

Figure 5 Analysis of the upstream regulatory factors that bind to the Dof, W-box, and ABRE elements by Y1H assays. (A) Schematic diagrams of the reporter and effector vectors. (B) Verification of the BpDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpbZIP3 effectors and reporter constructs of specific DNA motifs co-transformed into yeast Y187 cells. The DNA motifs are as follows: Dof p+, Dof p-, Dof, and mutated Dof elements; W-box p+, W-box p-, W-box, and mutated W-box elements; ABRE p+, ABRE p-, ABRE, and mutated ABRE elements. Dof p+, W-box p+, and ABRE p+: truncated BplMYB46 promoter containing Dof, W-box, and ABRE elements, respectively (located at -794 bp – -564 bp, -1347 bp – -1149 bp, and -534 bp – -348 bp upstream of the ORF of BplMYB46, respectively). Dof p-, W-box p-, and ABRE p-: truncated BplMYB46 promoter lacking Dof, W-box, and ABRE elements, respectively (located at -706 bp – -582 bp, -1305 bp – -1149 bp, and -480 bp – -348 bp upstream of the ORF of BplMYB46, respectively). Dof, W-box, and ABRE elements: three tandem copies of Dof, W-box, and ABRE elements, respectively. Mutated Dof, W-box, and ABRE elements: three tandem copies of mutated Dof, W-box, and ABRE elements, respectively (A/T was mutated to C, G/C was mutated to A). TF means BpDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpbZIP3 transcription factor, respectively. Positive control: pGADT7-p53/pHIS2-p53; Negative control: pGADT7-p53/pHIS2-BplMYB46 promoter.

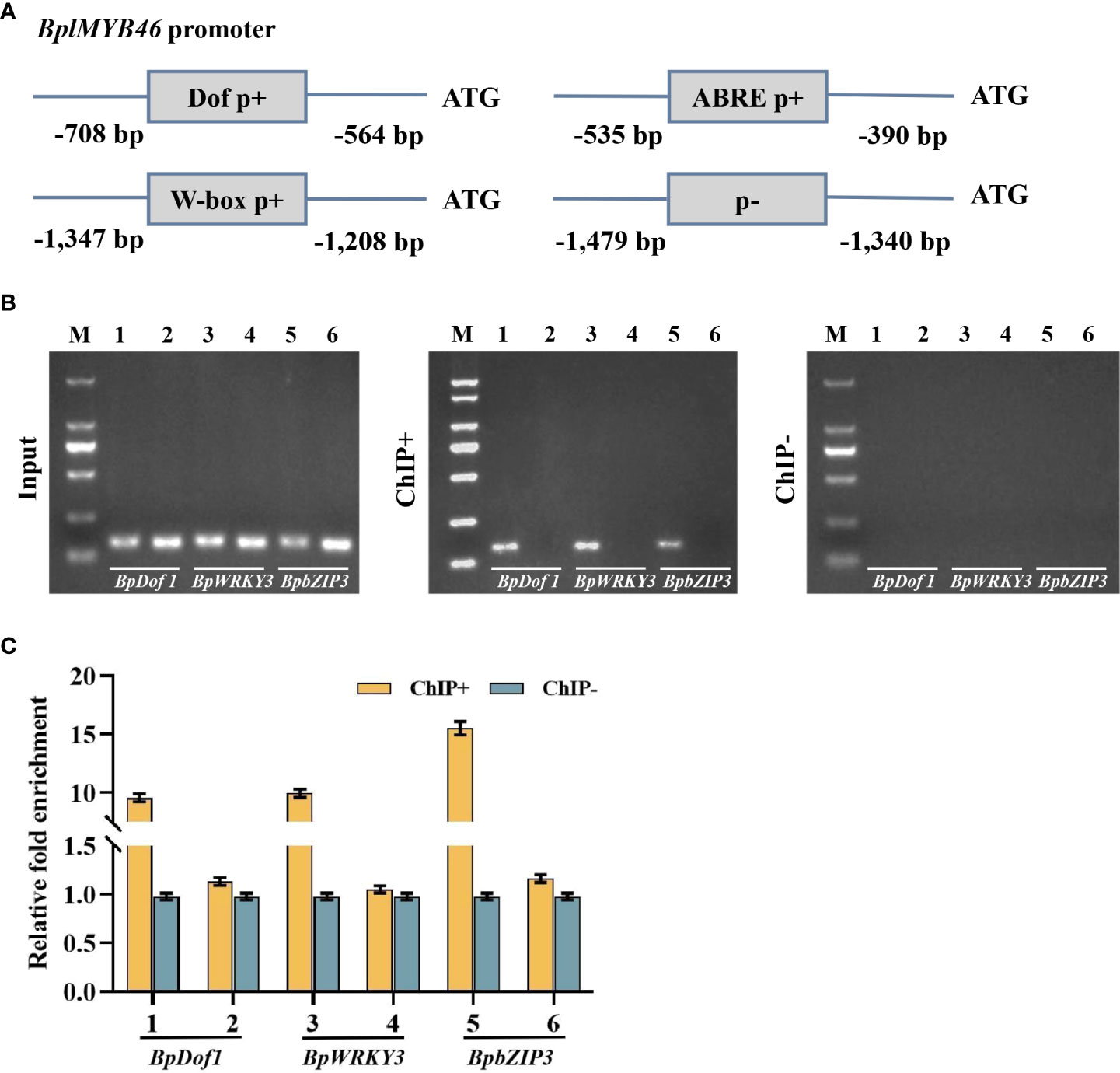

Interaction of upstream regulatory factors with specific elements in planta

The binding between the three upstream regulatory factors and specific cisacting elements in planta was analyzed using ChIP. The pBI121-35S::BpDof1-GFP, pBI121-35S::BpWRKY3-GFP and pBI121-35S::BpbZIP3-GFP construct was separately transformed into birch plants. BplMYB46 promoter fragments with Dof, W-box, and ABRE elements (Figure 6A) bound by BpDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpbZIP3 TFs were separately captured by ChIP using GFP antibody. ChIP-PCR results revealed that the BplMYB46 promoter fragments containing the Dof, W-box, and ABRE elements could be enriched by ChIP using GFP antibody (Figure 6B). However, the truncated promoter lacking Dof, W-box, and ABRE elements was not enriched by ChIP with GFP antibody (ChIP+) compared with the positive control input and the negative control (ChIP−) (Figure 6B). ChIP-qPCR revealed that the promoter region of BplMYB46, including the Dof, W-box, and ABRE elements, was significantly enriched in ChIP+, compared with ChIP− (Figure 6C). These findings indicated that BpDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpbZIP3 could specifically bind to the Dof, W-box, and ABRE elements in vivo, respectively.

Figure 6 The upstream regulatory factors of BplMYB46 specifically binding to the Dof, W-box, and ABRE elements according to ChIP assays. (A) Positions of truncated BplMYB46 promoters containing and lacking the Dof element. Dof p+, W-box p+, and ABRE p+: truncated BplMYB46 promoter containing three copies of the Dof element, two copies of the W-box element, and two copies of the ABRE element, respectively. p-: truncated BplMYB46 promoter without Dof, W-box, and ABRE elements. (B) ChIP products obtained from the promoter of BplMYB46 analyzed by gel electrophoresis after PCR amplification. M: DL2000 Marker (from top to bottom: 2 kb, 1 kb, 750 bp, 500 bp, 250 bp, and 100 bp). (C) Real-time quantitative PCR analysis showing the enrichment of the promoter sequence of BplMYB46 after ChIP. Input, Input DNA (positive control); CHIP+: chromatin immunoprecipitation with anti-GFP antibody; CHIP−: chromatin immunoprecipitation without antibody (negative control). 1: Dof p+, 3: W-box p+, 5: ABRE p+, 2, 4, 6: p-.

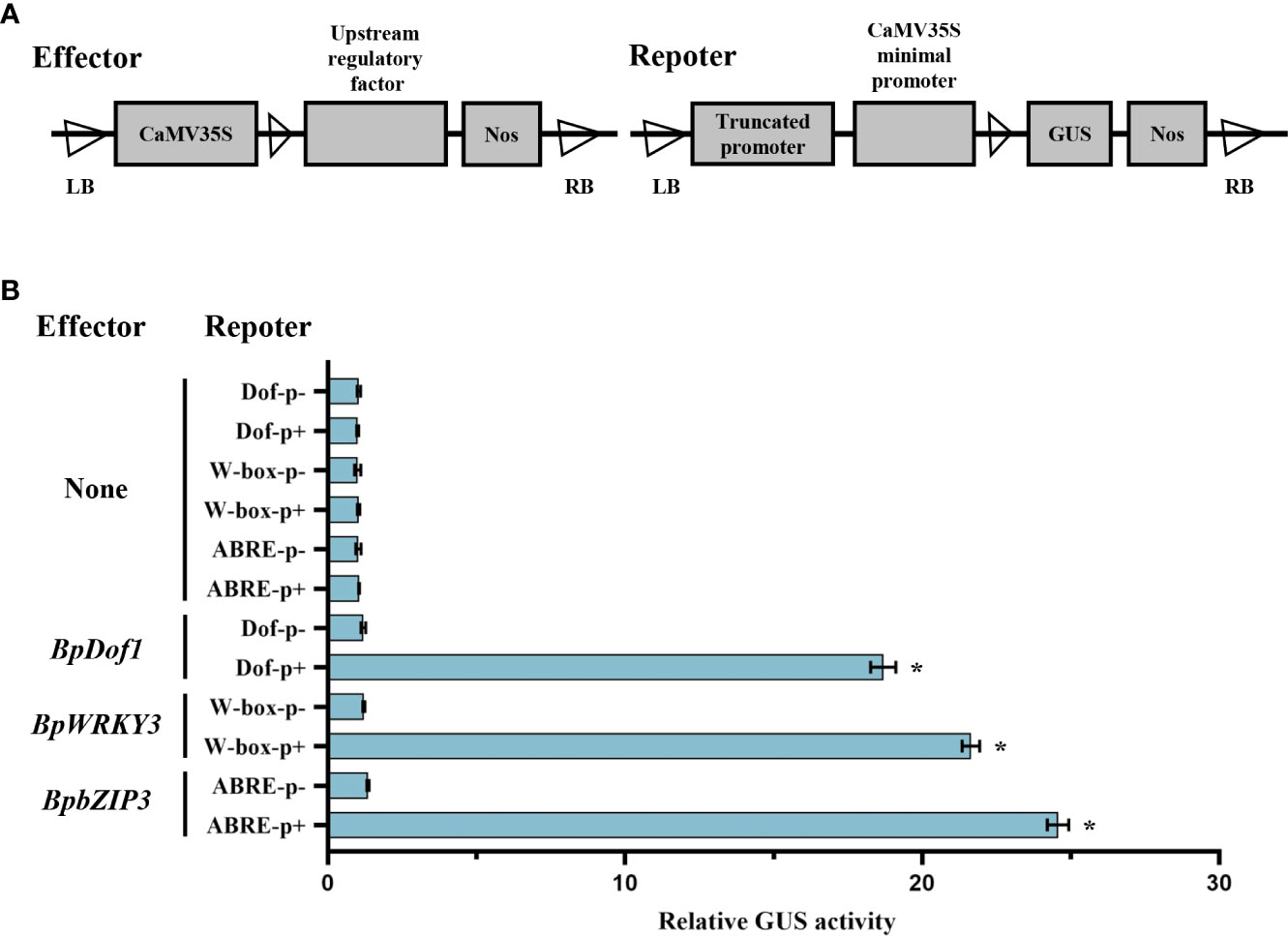

The binding ability of upstream regulatory factors to specific elements

To further substantiate the interaction between upstream regulatory factor and the truncated BplMYB46 promoter containing specific elements, we tested the interaction using the GUS reporter assay. Each effector of pROKII-35S::BpDof1, pROKII-35S::BpWRKY3 and pROKII-35S::BpbZIP3 was co-transformed with each truncated promoter containing or lacking Dof, W-box, or ABRE elements into birch plants (Figure 7A). Only the truncated promoter containing or lacking Dof, W-box, or ABRE elements, without effector, were designated as controls. The results ((Figure 7B) indicated that relative GUS activity was much higher in the transformed lines harboring the Dof, W-box, and ABRE than the control, which was about 18, 21 and 24 times that of the control, respectively. So, our results demonstrated that the high binding ability of BpDof1, BpWRKY3 and BpbZIP3 to the Dof, W-box, and ABRE elements in BplMYB46 promoter, respectively.

Figure 7 Analysis of upstream regulatory factors binding to the truncated promoters including Dof, W-box, or ABRE elements in birch plants. (A) Schematic representation of upstream regulatory factor and the truncated promoter including or lacking the Dof, W-box, or ABRE elements used in the co-expression of effector and reporter in birch plants. The upstream regulatory factor: pROKII-35S::BpDof1, pROKII-35S::BpWRKY3 or pROKII-35S::BpbZIP3. Dof p+, W-box p+, and ABRE p+: the truncated BplMYB46 promoter containing Dof, W-box, and ABRE elements, respectively. Dof p-, W-box p-, and ABRE p-: the truncated BplMYB46 promoter lacking Dof, W-box, and ABRE elements, respectively. (B) Transient co-transformation of effector and reporter constructs in birch plants to study the binding of BpDof1, BpWRKY3 and BpbZIP3 to Dof, W-box, and ABRE elements, respectively. GUS activity indicated the binding affinity of different upstream regulatory factor to the specific truncated promoter. Error bars indicate the standard deviation of three biological replicates. * indicates a significant difference (P < 0.05).

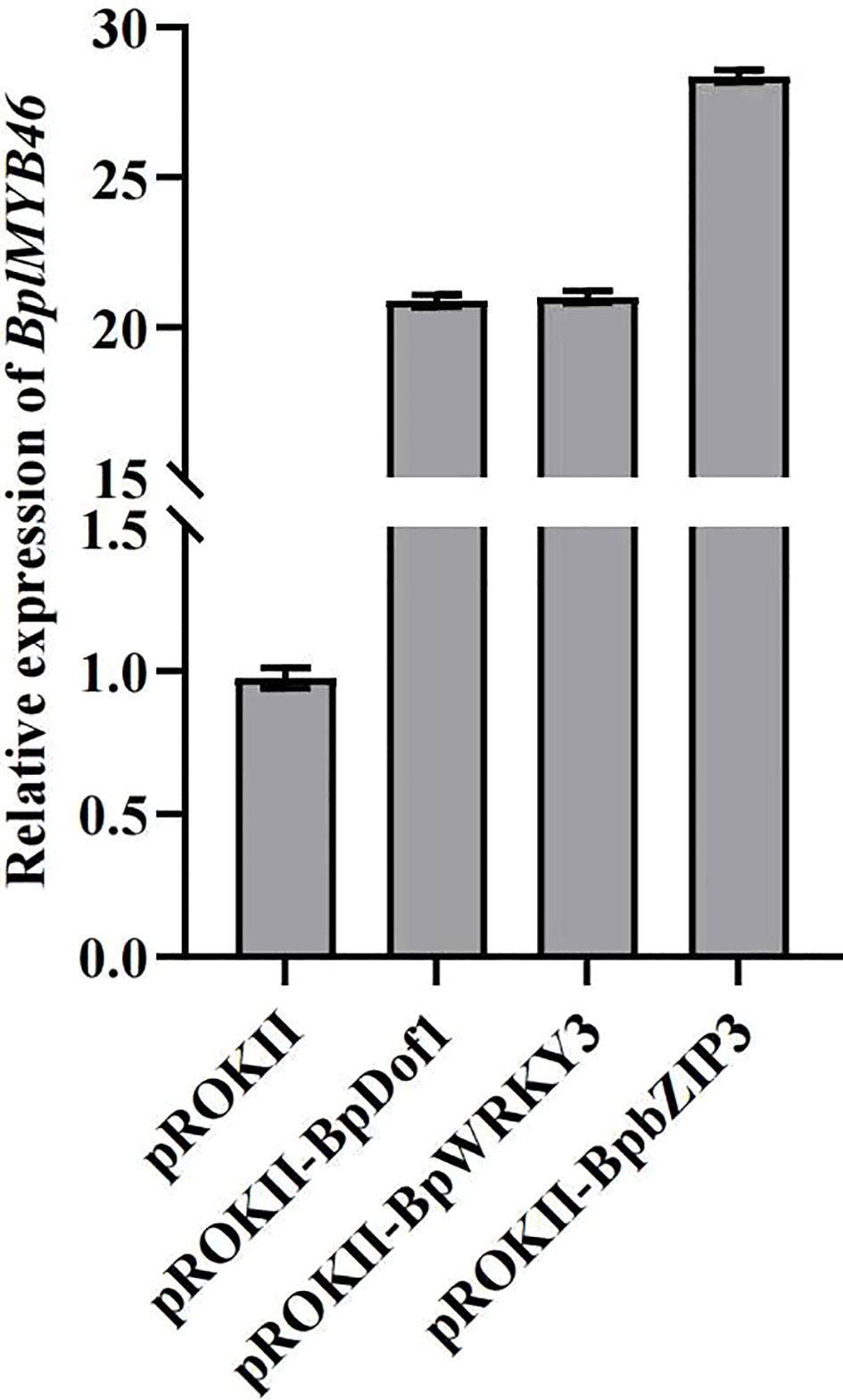

Analysis of BplMYB46 expression under regulation by upstream regulatory factors

To determine whether the upstream regulatory factors can regulate the expression of BplMYB46, we transformed each effector of pROKII-35S::BpDof1, pROKII-35S::BpWRKY3 and pROKII-35S::BpbZIP3 into birch using the transient transformation method to generate the overexpression plants, respectively. The relative expression of BplMYB46 was analyzed using qRT-PCR. The relative expression of BplMYB46 was much higher in BpDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpbZIP3-transformed birch plants compared with control plants transformed with the empty pROKII vector. The results further indicated that BpDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpbZIP3 can regulate the expression of BplMYB46 by specifically binding to Dof, W-box, and ABRE elements in BplMYB46 promoter (Figure 8).

Figure 8 The relative expression levels of BplMYB46. The effector, including pROKII-35S:: BpDof1, pROKII-35S:: BpWRKY3 and pROKII-35S:: BpbZIP3, was transiently transformed into one-month-old birch plants, respectively. The plants transformed with the empty pROKII vector were used as the control. Error bars indicate the standard deviation of three biological replicates.

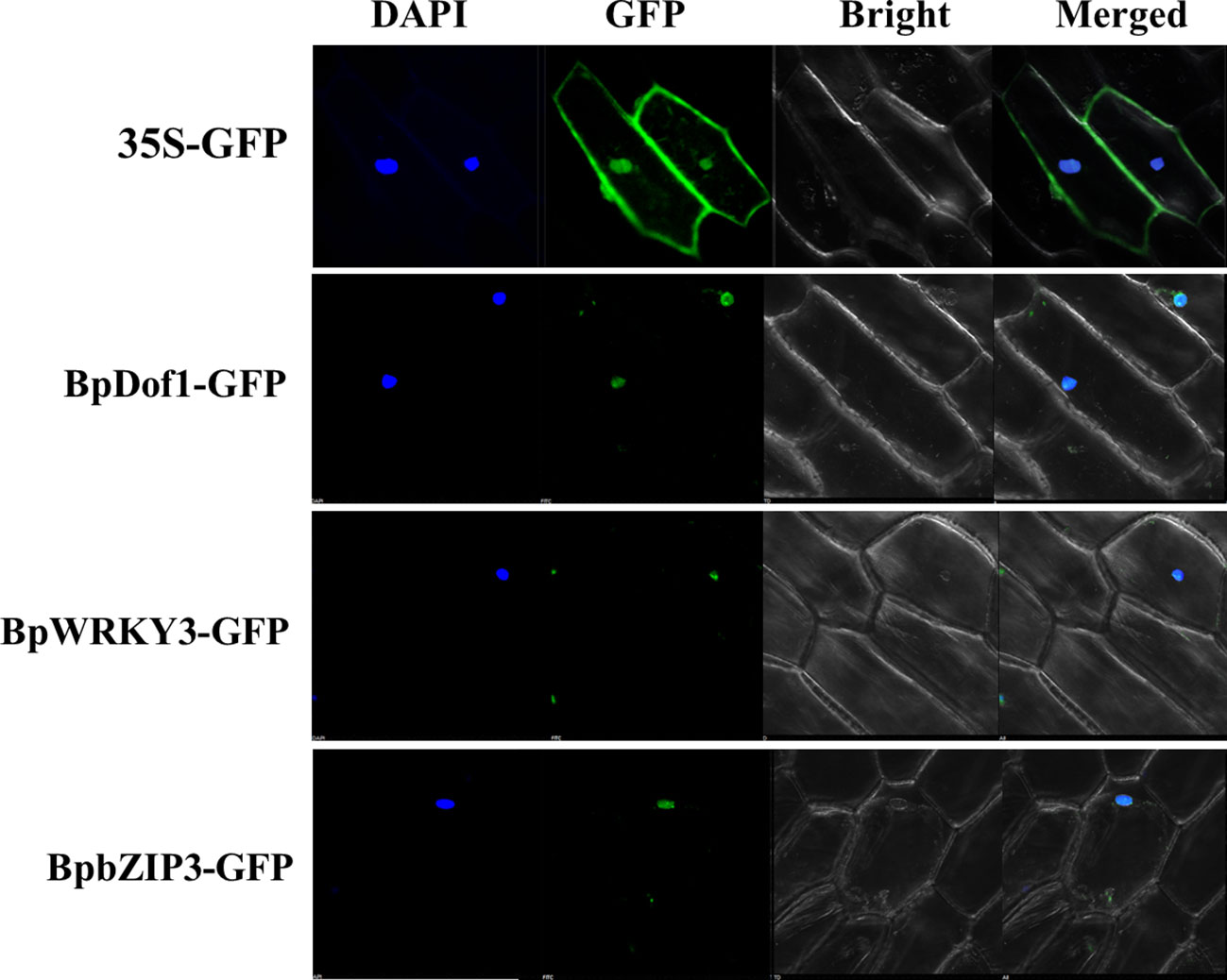

Subcellular localization of the three regulatory factors

The fusion genes of regulatory factors with GFP were transformed into onion epidermal cells by particle bombardment using 35S::GFP as the control. The 35S::GFP signals were uniformly distributed throughout the cell, but the green fluorescent signals from BpDof1-GFP, BpWRKY3-GFP, and BpbZIP3-GFP-transformed cells were detected in the nuclei, which were stained using DAPI (Figure 9). Our findings indicated that BpDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpbZIP3 are all nuclear proteins similar to BplMYB46.

Figure 9 Subcellular localization of three upstream regulatory factors. The fusion genes of BpDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpbZIP3 with GFP, with 35S-GFP as the control, were transiently expressed in onion epidermal cells using the particle bombardment method. The transformed cells were cultured on 1/2 Murashige-Skoog (1/2 MS) medium for 24 h and visualized using a confocal microscope at 488 nm. DAPI: DAPI staining of nuclei; GFP: GFP fluorescence detection; Bright: bright field; Merge: the DAPI, GFP, and bright field images merged.

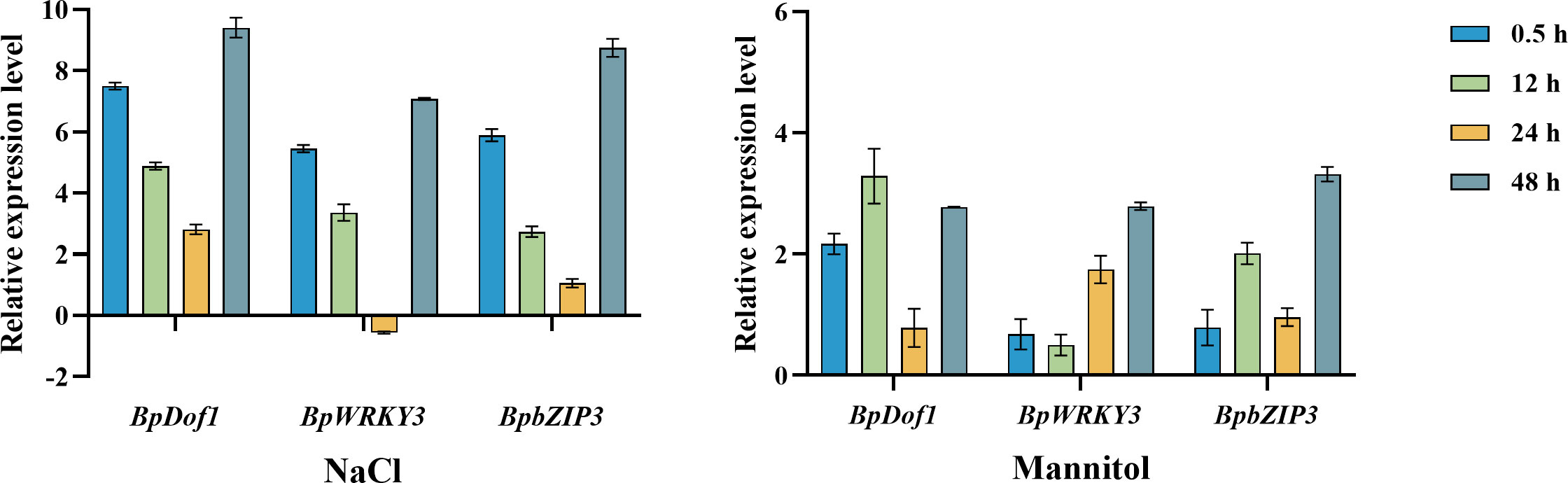

Expression patterns of the upstream regulatory factors in response to different types of abiotic stress

To clarify the expression patterns of BpDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpbZIP3 in response to salt and osmotic stress, qRT-PCR analyses were conducted (Figure 10). Under salt stress, the expression of all three genes was up-regulated from 0.5 h to 48 h relative to the control (water treatment), with the exception of BpWRKY3 at 24 h, and their expression levels were highest at 48 h. Under osmotic stress, the expression of these three genes was up-regulated from 0.5 h to 48 h relative to the control. The expression levels of BpWRKY3 and BpbZIP3 were highest at 48 h, whereas the expression of BpDof1 was highest at 12 h. Our findings indicated that the expression of BpDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpbZIP3 can be induced by salt and osmotic stress in birch plants.

Figure 10 Expression patterns of BpDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpbZIP3 under different types of abiotic stress. Two-month-old birch seedlings were treated with 200 mM NaCl and 300 mM mannitol for different lengths of time. Plants watered with fresh water were used as control. After these treatments, birch plants were harvested and pooled for RT-PCR analyses. The error bars indicate the standard deviation of three biological replicates.

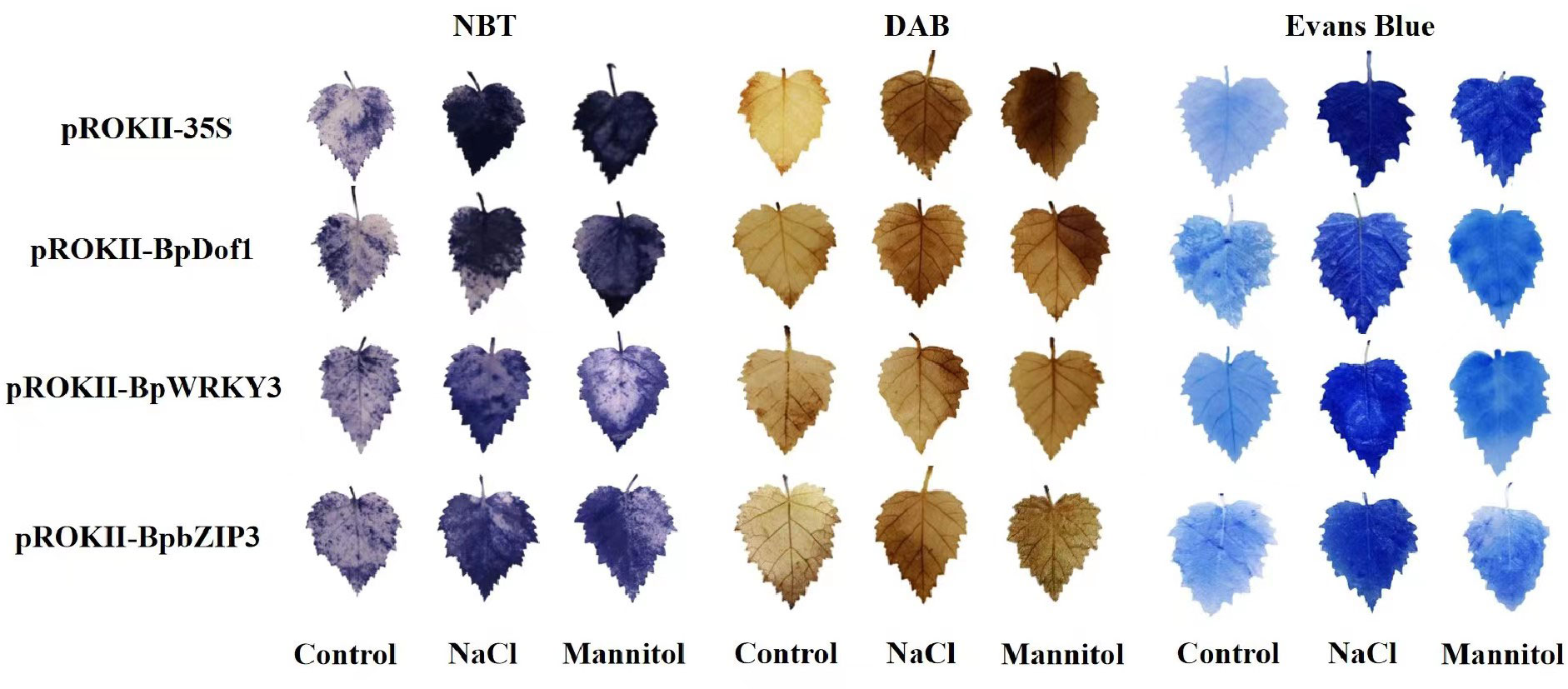

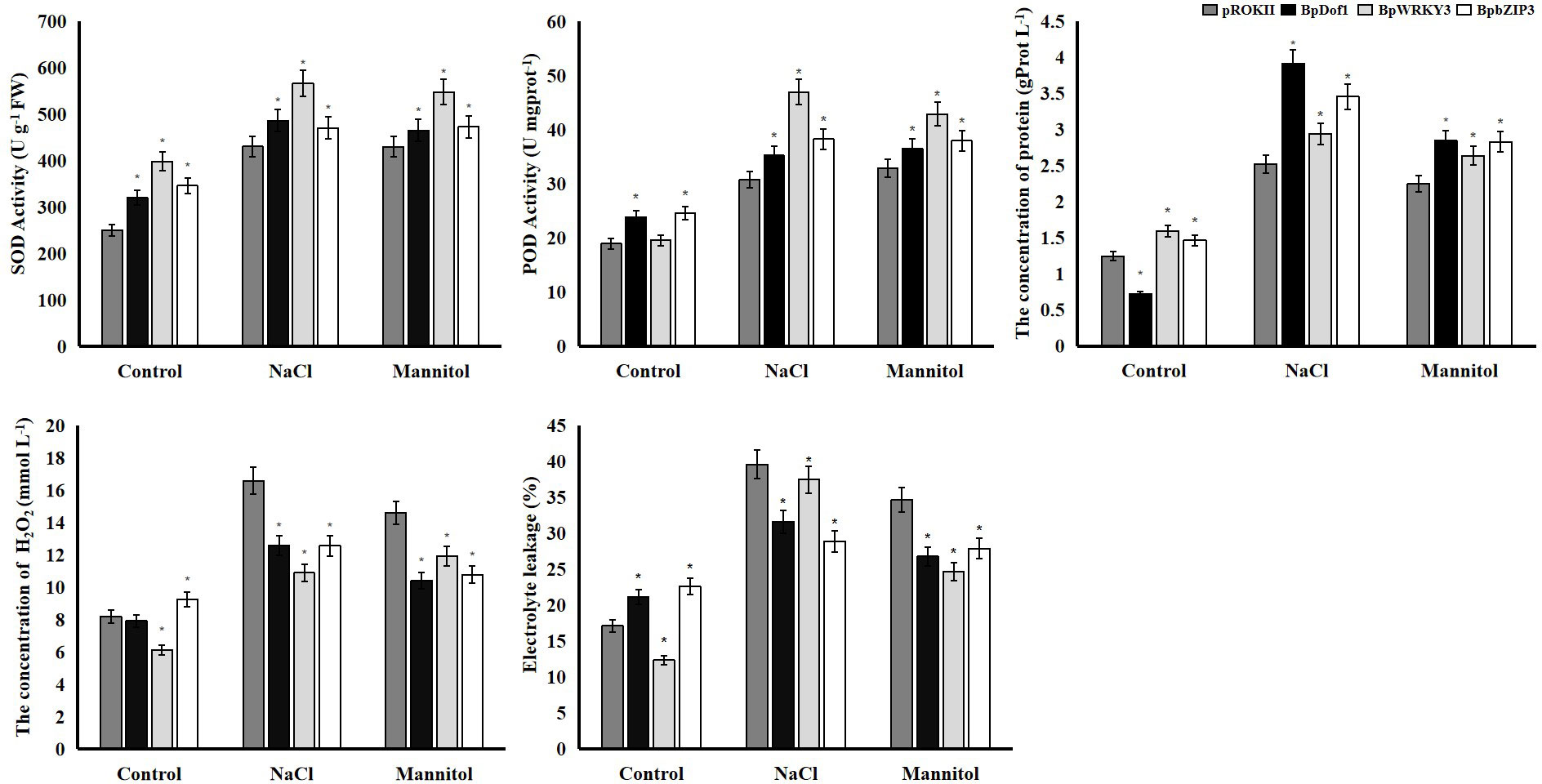

BpDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpbZIP3 overexpression mitigates oxidative stress and cell membrane damage

To study reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation, NBT and DAB in situ staining of overexpressing BpDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpbZIP3 were performed, which can stain two prominent ROS, O2− and H2O2, respectively (Figure 11). The leaves of BpDof1, BpWRKY3, BpbZIP3, and pROKII-35S plants were stained with NBT and DAB; stained leaves from water-treated plants were used as controls. Under salt and osmotic stress, O2− and H2O2 levels in the leaves of plants overexpressing BpDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpbZIP3 were greatly reduced compared with those in pROKII-35S plants. The content of O2− and H2O2 indicates the ROS-scavenging ability of plants. Our findings thus indicated that plants overexpressing BpDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpbZIP3 had enhanced ROS-scavenging abilities. Evans blue staining was conducted to detect cell membrane damage. The blue staining of plants overexpressing BpDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpbZIP3 was less intense compared with that of pROKII-35S plants under salt and osmotic stress, indicating that the extent of cell death was reduced in transgenic plants compared with pROKII-35S plants.

Figure 11 Analysis of ROS accumulation and cell membrane damage in overexpressing BpDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpbZIP3 plants under salt and osmotic stress. Birch plants overexpressing BpDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpdZIP3 were generated by transient transforming them with pROKII-35S::BpDof1, pROKII-35S::BpWRKY3, and pROKII-35S::BpbZIP3, respectively. The empty pROKII was transiently transformed into birch plants. After exposure to salt stress of 150 mM NaCl and mannitol stress of 200 mM for 12 h. Plants watered with fresh water were used as control. All birch plants were individually stained with NBT to visualize O2− levels and with DAB to visualize H2O2 levels. Evans blue staining was conducted to visualize cell membrane damage.

Physiological characterization of plants overexpressing BpDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpbZIP3

Activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and, peroxidase (POD) activities, the content of soluble protein and H2O2, and electrolyte leakage are often used to analyze the stress tolerance of plants. We characterized the activity of SOD and POD, the content of soluble protein and H2O2, and electrolyte leakage to evaluate the resistance of plants overexpressing BpDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpbZIP3 and control plants transformed with pROKII-35S to salt and osmotic stress (Figure 12). The activity of SOD and POD was higher in plants exposed to salt and osmotic stress than in control plants. The activity of SOD and POD was significantly higher in plants overexpressing BpDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpbZIP3 than in pROKII-35S plants, and the activity of SOD and POD was highest in plants overexpressing BpWRKY3. The concentrations of protein were higher in plants under abiotic stress compared with control plants. Concentrations of protein were significantly higher in plants overexpressing BpDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpbZIP3 than in pROKII-35S plants, and the concentration of protein was highest in plants overexpressing BpDof1 under salt and osmotic stress. The H2O2 level was significantly lower in plants overexpressing BpDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpbZIP3 than in pROKII-35S plants under salt and osmotic stress. The H2O2 level was lowest in plants overexpressing BpWRKY3 under salt stress and in plants overexpressing BpDof1 under osmotic stress. Electrolyte leakage was lower in the three transgenic plants than in pROKII-35S plants under salt and osmotic stress. Electrolyte leakage was lowest in plants overexpressing BpDof1 under salt stress and in plants overexpressing BpWRKY3 under osmotic stress. These findings indicate that BpDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpbZIP3 can enhance the ROS-scavenging ability of plants and inhibit cell death.

Figure 12 Physiological analyses of overexpressing BpDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpbZIP3 plants under salt and osmotic stress. Birch plants overexpressing BpDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpdZIP3 were generated by transient transformation method. The empty pROKII was transiently transformed into birch plants. All birch plants were treated using salt of 150 mM NaCl and mannitol of 200 mM for 12 h. Plants watered with fresh water were used as control. All birch plants were individually detected the activity of SOD and POD, content of protein and H2O2 and electrolyte leakage. The error bars indicate the standard deviation of three biological replicates. * indicates a significant difference (P < 0.05).

Discussion

Three regulatory factors directly bind to specific cis-acting elements in the promoter to regulate BplMYB46 expression

Abiotic stress is a main factor that limit plant growth and development, and TFs play key roles in abiotic stress responses (Xu et al., 2018). Previously, we have shown that BplMYB46 can enhance resistance to salt and osmotic stress in birch plants via gain-of-function and loss-of-function analyses (Guo et al., 2017). In the current study, the GUS expression driving by BplMYB46 promoter was highly induced in birch plants in response to salt and mannitol (Figure 2). These results suggest that BplMYB46 plays an important role in the response to abiotic stress. As BplMYB46 plays a regulatory role, its upstream regulatory factors should play more important regulatory roles, thus, studies of the upstream regulatory factors of BplMYB46 are more meaningful to clarify the molecular mechanism underlying the resistance of birch to stress. Previous reports found that Dof, WRKY and bZIP TFs can bind to Dof, W-box and ABRE elements, respectively (Yanagisawa, 2002; Rushton et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2022a). In the present study, Y1H and ChIP results both showed that three upstream regulatory factors of BplMYB46, named BplDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpbZIP3, can also specifically bind to the Dof, W-box, and ABRE elements in the BplMYB46 promoter, respectively. TFs regulate the expressions of the target genes via binding to the cis-acting elements in the promoters. For instance, the TF GmNFYA can regulate the expression of GmZF392 and GmZF351 by binding to the CCAAT box in their promoter regions, in soybean (Lu et al., 2021). ThNAC12 can directly regulate the expression of ThPIP2;5 by binding to the NACRS element in the ThPIP2;5 promoter (Wang et al., 2021b). In this study, GUS activity analysis further verified the high binding ability of the upstream regulatory factors and the specific cis-acting elements (Figure 7), and the relative expression of BplMYB46 was much higher in the overexpressing transient transgenic birch plants of BplDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpbZIP3 compared with control plants (Figure 8), which indicates that the three genes directly regulate the expression of BplMYB46 by binding to the Dof, W-box, and ABRE elements in its promoter, respectively.

The upstream regulatory factors are localized to the nucleus and respond to salt and osmotic stress

In this study, the three upstream regulatory transcription factors of BplMYB46, namely BplDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpbZIP3, are all localized to the nucleus (Figure 9) like to BplMYB46 (Guo et al., 2017). Previous studies have indicated that most plant TFs are localized to the nucleus, and play their regulatory role (Wang et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2017; Ren et al., 2020), and our results are consistent with these studies. In Cleistogenes songorica, the expression of Dof genes can respond to high/low temperature, salinity, and ABA treatment (Wang et al., 2021a). In Spirodela polyrhiza, the expression patterns of SpWRKYs under phosphate starvation, cold, and submergence treatment indicate that most SpWRKYs are involved in the response to different types of abiotic stress (Zhao et al., 2021). Gene expression patterns and qRT-PCR results indicate that four JcbZIPs in Jatropha curcas are key stress resistance-related genes under drought and salinity stress (Wang et al., 2021c). Our qRT-PCR results also revealed that three upstream regulatory factors, BplDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpbZIP3 can respond to salt and osmotic stress, suggesting they may be involved in stress-signaling pathways.

BpDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpbZIP3 enhance resistance to salt and osmotic stress when they are overexpressed in transgenic birch plants

Plants are often exposed to various types of stress, and this can result in the accumulation of ROS (Wang et al., 2005), and ROS scavenging is thus an important mechanism by which plants resist various types of stress (Zhang et al., 2011). SOD and POD are important antioxidant enzymes and they play the vital roles in ROS scavenging in plants (Wu et al., 2013). Our findings indicate that BpDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpbZIP3 can enhance the ROS-scavenging ability of plants by increasing the activity of SOD and POD. Some studies have shown that the accumulation of soluble protein in cells plays an osmoregulatory role and thus can increase the resistance to osmotic stress in plants (Parvaiz and Satyawati, 2008; Hanif et al., 2021). Our study showed that overexpression of BpDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpbZIP3 can improve stress tolerance by regulating soluble sugar accumulation to balance osmotic pressure. Evans blue staining and electrolyte leakage can affect cell death in plants, as manifested by damage to the cell membrane (Wang et al., 2014). Our results indicated that BpDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpbZIP3 can improve stress resistance of plants by reducing the extent of cell death, according to Evans blue staining and electrolyte leakage analysis.

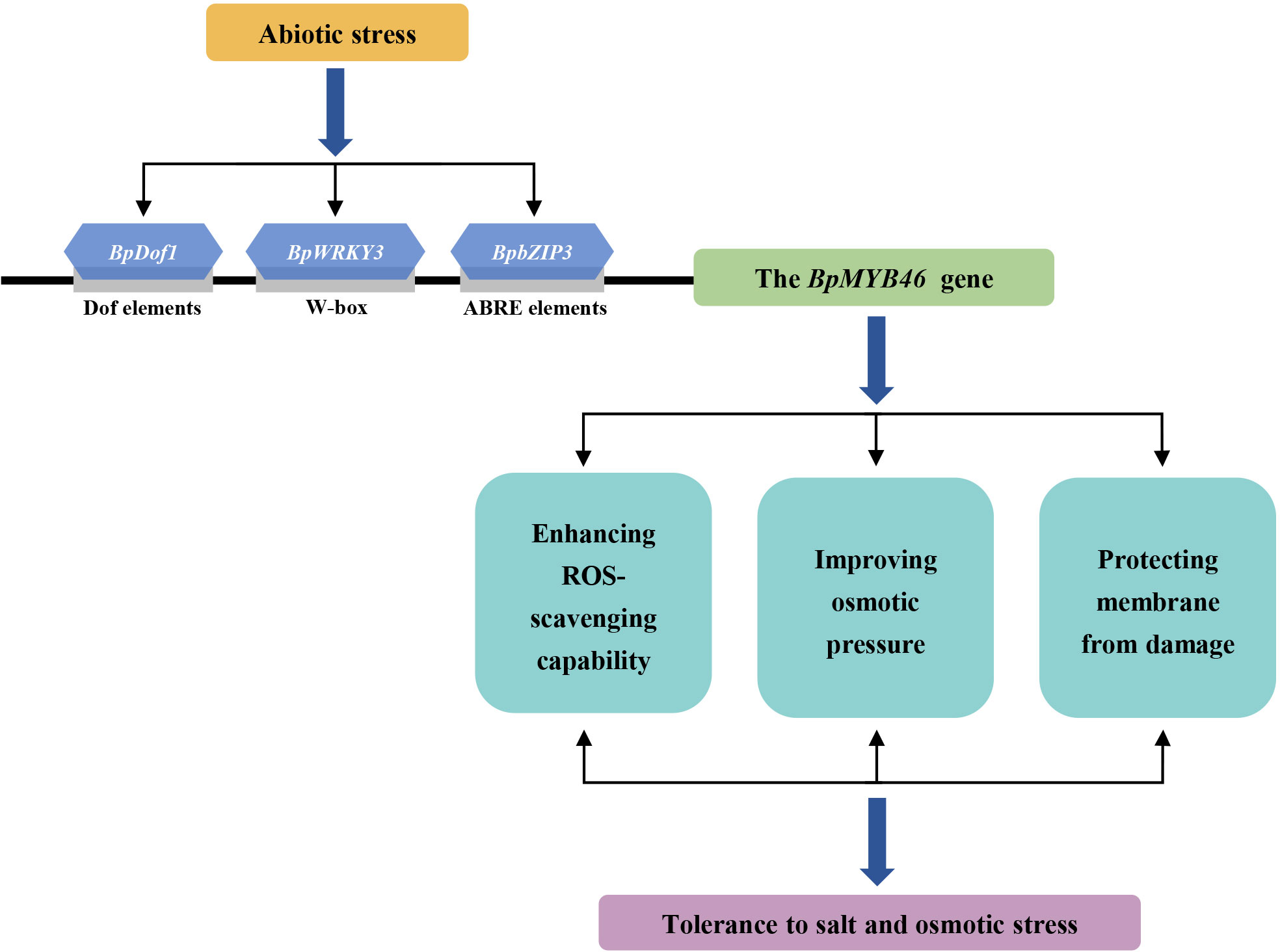

An upstream regulatory model presenting the function of BplMYB46 in the response to abiotic stress

Based on the present results, we propose a model describing the upstream regulation of BplMYB46 in the response to abiotic stress (Figure 13). Abiotic stress, such as salt or osmotic stress, can induce the expression of BpDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpbZIP3. The activated BpDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpbZIP3 then separately specifically binds to Dof, W-box, and ABRE elements to regulate the expression of BplMYB46 gene. BplMYB46 gene significantly altered the expression of its target genes, and triggered physiological changes, including reduced ROS accumulation and membrane damage, improved osmotic pressure, which ultimately enhanced salt and osmotic stress tolerance in birch plant.

Figure 13 Model of the upstream regulatory network of BplMYB46 involved in abiotic stress responses. Abiotic stress, such as salt or osmotic stress, significantly induce the expression of BpDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpdZIP3. The activated BpDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpdZIP3 then separately binds to Dof, W-box and ABRE elements to regulate the expression of BplMYB46 gene, which result in significant physiological changes, including reduced reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation and membrane damage, and improved osmotic pressure, leading to enhanced salt and osmotic stress tolerance.

Conclusion

Analyses of GUS staining and activity driven by the BplMYB46 promoter revealed that the BplMYB46 promoter exhibits temporal and spatial expression specificity and its expression can be induced by salt and osmotic treatment in vivo. Three upstream regulatory factors of BplMYB46, BpDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpbZIP3, were identified using Y1H and ChIP assays. GUS activity and qRT-PCR revealed that BpDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpbZIP3 can regulate the expression of BplMYB46 by specifically binding to Dof, W-box, and ABRE elements in the BplMYB46 promoter, respectively. BpDof1, BpWRKY3, and BpbZIP3 were all localized to the nucleus and enhanced tolerance to salt and osmotic stress when they were overexpressed in birch plants. Our study displayed that the upstream regulatory factors of BplMYB46 were identified and their overexpressing birch plants increased the stress tolerance, therefore provided the new candidate genes for breeding of new forest tree varieties with resistance to adverse environments.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Author contributions

HG and YW designed the study. XS, BW, and HS provided reagents and materials for the experiments. XS, BW, DW, and HS participated in the experiments, and analyzed the data. HG and YW drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31700587) and the Xingliao Talents Program (XLYC1902007).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2022.1030459/full#supplementary-material

References

An, J.-P., Wang, X.-F., Zhang, X.-W., Xu, H.-F., Bi, S.-Q., You, C.-X., et al. (2020). An apple MYB transcription factor regulates cold tolerance and anthocyanin accumulation and undergoes MIEL1-mediated degradation. Plant Biotechnol. J. 18 (2), 337–353. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13201

Berardi, A. E., Esfeld, K., Jaggi, L., Mandel, T., Cannarozzi, G. M., Kuhlemeier, C. (2021). Complex evolution of novel red floral color in petunia. Plant Cell 33 (7), 2273–2295. doi: 10.1093/plcell/koab114

Cao, X., Xu, L., Li, L., Wan, W., Jiang, J. (2022). TcMYB29a, an ABA-responsive R2R3-MYB transcriptional factor, upregulates taxol biosynthesis in taxus chinensis. Front. Plant Sci. 13. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.804593

Cheng, Y.-J., Guo, W.-W., Yi, H.-L., Pang, X.-M., Deng, X. (2003). An efficient protocol for genomic DNA extraction fromCitrus species. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 21 (2), 177–178. doi: 10.1007/BF02774246

Chen, R., Ma, J., Luo, D., Hou, X., Ma, F., Zhang, Y., et al. (2019). CaMADS, a MADS-box transcription factor from pepper, plays an important role in the response to cold, salt, and osmotic stress. Plant Sci. 280, 164–174. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2018.11.020

Franco-Zorrilla, J. M., Solano, R. (2017). Identification of plant transcription factor target sequences. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gene Regul. Mech. 1860 (1), 21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2016.05.001

Gampala, S. S., Hagenbeek, D., Rock, C. D. (2001). Functional interactions of lanthanum and phospholipase d with the abscisic acid signaling effectors VP1 and ABI1-1 in rice protoplasts. J. Biol. Chem. 276 (13), 9855–9860. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009168200

Guo, H., Wang, Y., Wang, L., Hu, P., Wang, Y., Jia, Y., et al. (2017). Expression of the MYB transcription factor gene BplMYB46 affects abiotic stress tolerance and secondary cell wall deposition in betula platyphylla. Plant Biotechnol. J. 15 (1), 107–121. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12595

Guo, H. Y., Wang, L. Q., Yang, C. P., Zhang, Y. M., Zhang, C. R., Wang, C. (2018). Identification of novel cis-elements bound by BpIMYB46 involved in abiotic stress responses and secondary wall deposition. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 60 (10), 1000–1014. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12671

Hanif, S., Saleem, M. F., Sarwar, M., Irshad, M., Shakoor, A., Wahid, M. A., et al. (2021). Biochemically triggered heat and drought stress tolerance in rice by proline application. J. Plant Growth Regul. 40 (1), 305–312. doi: 10.1007/s00344-020-10095-3

Hickman, R., Hill, C., Penfold, C. A., Breeze, E., Bowden, L., Moore, J. D., et al. (2013). A local regulatory network around three NAC transcription factors in stress responses and senescence in arabidopsis leaves. Plant J. 75 (1), 26–39. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12194

Hu, P., Zhang, K. M., Yang, C. P. (2019). BpNAC012 positively regulates abiotic stress responses and secondary wall biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 179 (2), 700–717. doi: 10.1104/pp.18.01167

Iqbal, Z., Iqbal, M. S., Hashem, A., Abd Allah, E. F., Ansari, M. I. (2021). Plant defense responses to biotic stress and its interplay with fluctuating Dark/Light conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 12. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.631810

Jiang, H., Zhou, L.-J., Gao, H. N., Wang, X. F., Li, Z. W., Li, Y. Y. (2022). The transcription factor MdMYB2 influences cold tolerance and anthocyanin accumulation by activating SUMO E3 ligase MdSIZ1 in apple. Plant Physiol. 189(4), 2044–2060. doi: 10.1093/plphys/kiac211

Jin, W., Wang, H., Li, M., Wang, J., Yang, Y., Zhang, X., et al. (2016). The R2R3 MYB transcription factor PavMYB10.1 involves in anthocyanin biosynthesis and determines fruit skin colour in sweet cherry (Prunus avium l.). Plant Biotechnol. J. 14 (11), 2120–2133. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12568

Ji, X., Zheng, L., Liu, Y., Nie, X., Liu, S., Wang, Y. (2014). A transient transformation system for the functional characterization of genes involved in stress response. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 32 (3), 732–739. doi: 10.1007/s11105-013-0683-z

Kim, M., Ahn, J.-W., Jin, U.-H., Choi, D., Paek, K.-H., Pai, H.-S. (2003). Activation of the programmed cell death pathway by inhibition of proteasome function in plants. J. Biol. Chem. 278 (21), 19406–19415. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210539200

Liu, Y., Ji, X., Nie, X., Qu, M., Zheng, L., Tan, Z., et al. (2015). Arabidopsis AtbHLH112 regulates the expression of genes involved in abiotic stress tolerance by binding to their e-box and GCG-box motifs. New Phytol. 207 (3), 692–709. doi: 10.1111/nph.13387

Lu, L., Wei, W., Li, Q.-T., Bian, X.-H., Lu, X., Hu, Y., et al. (2021). A transcriptional regulatory module controls lipid accumulation in soybean. New Phytol. 231 (2), 661–678. doi: 10.1111/nph.17401

Mitra, M., Agarwal, P., Kundu, A., Banerjee, V., Roy, S. (2019). Investigation of the effect of UV-b light on arabidopsis MYB4 (AtMYB4) transcription factor stability and detection of a putative MYB4-binding motif in the promoter proximal region of AtMYB4. PLoS One 14 (8). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0220123

Parvaiz, A., Satyawati, S. (2008). Salt stress and phyto-biochemical responses of plants - a review. Plant Soil Environ. 54, 89–99. doi: 10.17221/2774-PSE

Pfaffl, M. W., Horgan, G. W., Dempfle, L. (2002). Relative expression software tool (REST) for group-wise comparison and statistical analysis of relative expression results in real-time PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 30 (9), e36. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.9.e36

Ren, D., Rao, Y., Yu, H., Xu, Q., Cui, Y., Xia, S., et al. (2020). MORE FLORET1 encodes a MYB transcription factor that regulates spikelet development in rice. Plant Physiol. 184 (1), 251–265. doi: 10.1104/pp.20.00658

Rushton, P. J., Somssich, I. E., Ringler, P., Shen, Q. J. (2010). WRKY transcription factors. Trends Plant Sci. 15 (5), 247–258. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.02.006

Shi, Y., Man, J., Huang, Y., Zhang, J., Zhang, Z., Yin, G., et al. (2022). Overexpression of PnMYB2 from panax notoginseng induces cellulose and lignin biosynthesis during cell wall formation. Planta 255 (5). doi: 10.1007/s00425-022-03891-6

Wang, L., Lu, W., Ran, L., Dou, L., Yao, S., Hu, J., et al. (2019). R2R3-MYB transcription factor MYB6 promotes anthocyanin and proanthocyanidin biosynthesis but inhibits secondary cell wall formation in populus tomentosa. Plant J. 99 (4), 733–751. doi: 10.1111/tpj.14364

Wang, L. Q., Qin, L. P., Liu, W. J., Zhang, D. Y., Wang, Y. C. (2014). A novel ethylene-responsive factor from tamarix hispida, ThERF1, is a GCC-box- and DRE-motif binding protein that negatively modulates abiotic stress tolerance in arabidopsis. Physiologia Plantarum 152 (1), 84–97. doi: 10.1111/ppl.12159

Wang, F.-Z., Wang, Q.-B., Kwon, S.-Y., Kwak, S.-S., Su, W.-A. (2005). Enhanced drought tolerance of transgenic rice plants expressing a pea manganese superoxide dismutase. J. Plant Physiol. 162 (4), 465–472. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2004.09.009

Wang, B. X., Xu, B., Liu, Y., Li, J. F., Sun, Z. H., Chi, M., et al. (2022a). A novel mechanisms of the signaling cascade associated with the SAPK10-bZIP20-NHX1 synergistic interaction to enhance tolerance of plant to abiotic stress in rice (Oryza sativa l.). Plant Sci. an Int. J. Exp. Plant Biol. 323, 111393. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2022.111393

Wang, P., Yan, Z., Zong, X., Yan, Q., Zhang, J. (2021a). Genome-wide analysis and expression profiles of the dof family in cleistogenes songorica under temperature, salt and ABA treatment. Plants-Basel 10 (5). doi: 10.3390/plants10050850

Wang, Z., Zhang, B., Chen, Z., Wu, M., Chao, D., Wei, Q., et al. (2022b). Three OsMYB36 members redundantly regulate casparian strip formation at the root endodermis. Plant Cell. 34 (8), 2948–2968. doi: 10.1093/plcell/koac140

Wang, R., Zhang, Y., Wang, C., Wang, Y. C., Wang, L. Q. (2021b). ThNAC12 from tamarix hispida directly regulates ThPIP2;5 to enhance salt tolerance by modulating reactive oxygen species. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 163, 27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2021.03.042

Wang, L., Zheng, L., Zhang, C., Wang, Y., Lu, M., Gao, C. (2015). ThWRKY4 from tamarix hispida can form homodimers and heterodimers and is involved in abiotic stress responses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 16 (11), 27097–27106. doi: 10.3390/ijms161126009

Wang, Z., Zhu, J., Yuan, W., Wang, Y., Hu, P., Jiao, C., et al. (2021c). Genome-wide characterization of bZIP transcription factors and their expression patterns in response to drought and salinity stress in jatropha curcas. Int. J. Biol. Macromolecules 181, 1207–1223. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.05.027

Wu, B., Zhang, S.W., Gao, D., Pan, C.M. (2013). Effect of Drought Stress and Re-watering on Active Oxygen Scavenging System of Fructus Evodiae Cutting Seedling. J. Guangzhou Univ. Trad. Chin. Med. 78–82.

Wu, Q., Liu, X., Yin, D., Yuan, H., Xie, Q., Zhao, X., et al. (2017). Constitutive expression of OsDof4, encoding a c-2-C-2 zinc finger transcription factor, confesses its distinct flowering effects under long- and short-day photoperiods in rice (Oryza sativa l.). BMC Plant Biol. 17. doi: 10.1186/s12870-017-1109-0

Xiao, R., Zhang, C., Guo, X., Li, H., Lu, H. (2021). MYB transcription factors and its regulation in secondary cell wall formation and lignin biosynthesis during xylem development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 (7). doi: 10.3390/ijms22073560

Xue, C., Yao, J.-L., Xue, Y.-S., Su, G.-Q., Wang, L., Lin, L.-K., et al. (2019). PbrMYB169 positively regulates lignification of stone cells in pear fruit. J. Exp. Bot. 70 (6), 1801–1814. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erz039

Xu, H., Shi, X., He, L., Guo, Y., Zang, D., Li, H., et al. (2018). Arabidopsis thaliana trihelix transcription factor AST1 mediates salt and osmotic stress tolerance by binding to a novel AGAG-box and some GT motifs. Plant Cell Physiol. 59 (5), 946–965. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcy032

Yanagisawa, S. (2002). The dof family of plant transcription factors. Trends Plant Sci. 7 (12), 555–560. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(02)02362-2

Yao, C., Li, W., Liang, X., Ren, C., Liu, W., Yang, G., et al. (2022). Molecular cloning and characterization of MbMYB108, a malus baccata MYB transcription factor gene, with functions in tolerance to cold and drought stress in transgenic arabidopsis thaliana. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 (9). doi: 10.3390/ijms23094846

Yu, Y., Liu, H., Zhang, N., Gao, C., Qi, L., Wang, C. (2021). The BpMYB4 transcription factor from betula platyphylla contributes toward abiotic stress resistance and secondary cell wall biosynthesis. Front. Plant Sci. 11. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.606062

Zang, D. D., Wang, L. N., Zhang, Y. M., Zhao, H. M., Wang, Y. C. (2017). ThDof1.4 and ThZFP1 constitute a transcriptional regulatory cascade involved in salt or osmotic stress in tamarix hispida. Plant Mol. Biol. 94 (4-5), 495–507. doi: 10.1007/s11103-017-0620-x

Zhang, X., He, Y., Li, L., Liu, H., Hong, G. (2021). Involvement of the R2R3-MYB transcription factor MYB21 and its homologs in regulating flavonol accumulation in arabidopsis stamen. J. Exp. Bot. 72 (12), 4319–4332. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erab156

Zhang, P., Liu, X., Yu, X., Wang, F., Long, J., Shen, W., et al. (2020). The MYB transcription factor CiMYB42 regulates limonoids biosynthesis in citrus (vol 20, 254, 2020). BMC Plant Biol. 20 (1). doi: 10.1186/s12870-020-02491-4

Zhang, X., Wang, L., Meng, H., Wen, H., Fan, Y., Zhao, J. (2011). Maize ABP9 enhances tolerance to multiple stresses in transgenic arabidopsis by modulating ABA signaling and cellular levels of reactive oxygen species. Plant Mol. Biol. 75 (4-5), 365–378. doi: 10.1007/s11103-011-9732-x

Zhao, H., Li, H., Jia, Y., Wen, X., Guo, H., Xu, H., et al. (2020). Building a robust chromatin immunoprecipitation method with substantially improved efficiency. Plant Physiol. 183 (3), 1026–1034. doi: 10.1104/pp.20.00392

Zhao, X., Yang, J., Li, G., Sun, Z., Hu, S., Chen, Y., et al. (2021). Genome-wide identification and comparative analysis of the WRKY gene family in aquatic plants and their response to abiotic stresses in giant duckweed (Spirodela polyrhiza). Genomics 113 (4), 1761–1777. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2021.03.035

Keywords: BplMYB46, Betula platyphylla, upstream regulatory factors, cis-acting elements, stress resistance

Citation: Guo H, Sun X, Wang B, Wu D, Sun H and Wang Y (2022) The upstream regulatory mechanism of BplMYB46 and the function of upstream regulatory factors that mediate resistance to stress in Betula platyphylla. Front. Plant Sci. 13:1030459. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.1030459

Received: 29 August 2022; Accepted: 11 October 2022;

Published: 25 October 2022.

Edited by:

Stephan Pollmann, National Institute of Agricultural and Food Research and Technology, SpainReviewed by:

Siti Nor Akmar Abdullah, Universiti Putra Malaysia, MalaysiaYanjun Jing, Institute of Botany (CAS), China

Copyright © 2022 Guo, Sun, Wang, Wu, Sun and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yucheng Wang, d2FuZ3l1Y2hlbmdAbXMueGpiLmFjLmNu

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Huiyan Guo

Huiyan Guo Xiaomeng Sun

Xiaomeng Sun Bo Wang1,2

Bo Wang1,2 Yucheng Wang

Yucheng Wang