94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Plant Sci., 15 December 2021

Sec. Plant Breeding

Volume 12 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.738805

This article is part of the Research TopicThe Brassicaceae — Agri-Horticultural and Environmental Perspectives, Volume IIView all 19 articles

Karanjot Singh Gill1†

Karanjot Singh Gill1† Gurpreet Kaur1*†

Gurpreet Kaur1*† Gurdeep Kaur1

Gurdeep Kaur1 Jasmeet Kaur1

Jasmeet Kaur1 Simarjeet Kaur Sra1

Simarjeet Kaur Sra1 Kawalpreet Kaur1

Kawalpreet Kaur1 Kaur Gurpreet1

Kaur Gurpreet1 Meha Sharma1

Meha Sharma1 Mitaly Bansal2

Mitaly Bansal2 Parveen Chhuneja2

Parveen Chhuneja2 Surinder S. Banga1

Surinder S. Banga1Brassica juncea L. is the most widely cultivated oilseed crop in Indian subcontinent. Its seeds contain oil with very high concentration of erucic acid (≈50%). Of late, there is increasing emphasis on the development of low erucic acid varieties because of reported association of the consumption of high erucic acid oil with cardiac lipidosis. Erucic acid is synthesized from oleic acid by an elongation process involving two cycles of four sequential steps. Of which, the first step is catalyzed by β-ketoacyl-CoA synthase (KCS) encoded by the fatty acid elongase 1 (FAE1) gene in Brassica. Mutations in the coding region of the FAE1 lead to the loss of KCS activity and consequently a drastic reduction of erucic acid in the seeds. Molecular markers have been developed on the basis of variation available in the coding or promoter region(s) of the FAE1. However, majority of these markers are not breeder friendly and are rarely used in the breeding programs. Present studies were planned to develop robust kompetitive allele-specific PCR (KASPar) assays with high throughput and economics of scale. We first cloned and sequenced FAE1.1 and FAE1.2 from high and low erucic acid (<2%) genotypes of B. juncea (AABB) and its progenitor species, B. rapa (AA) and B. nigra (BB). Sequence comparisons of FAE1.1 and FAE1.2 genes for low and high erucic acid genotypes revealed single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) at 8 and 3 positions. Of these, three SNPs for FAE1.1 and one SNPs for FAE1.2 produced missense mutations, leading to amino acid modifications and inactivation of KCS enzyme. We used SNPs at positions 735 and 1,476 for genes FAE1.1 and FAE1.2, respectively, to develop KASPar assays. These markers were validated on a collection of diverse genotypes and a segregating backcross progeny. KASPar assays developed in this study will be useful for marker-assisted breeding, as these can track recessive alleles in their heterozygous state with high reproducibility.

Developed KASPar assays for selection of low erucic acid are high throughput, robust, and codominant capable to track recessive alleles in their heterozygous state.

Indian mustard [Brassica juncea (L.) Czern and Coss] is an important source of edible and industrial oil in the Indian subcontinent. Its seeds contain nearly 40% oil on a seed weight basis. Similar to other plants, oil in Indian mustard is a complex mixture of triglycerides (>95%) along with diacylglycerols (<5%), phytosterols, etc. Though mustard oil contains seven major fatty acids, erucic acid, a very long chain fatty acid (C22:1) is the predominant fatty acid contributing more than 50% to the total pool of fatty acids. Such levels are undesirable in view of their perceived role in cardiac lipidosis and fatty deposits in skeletal muscles (Vogtmann et al., 1975; Burrows and Tyrl, 2013). This concern precipitated substantive efforts to genetically reduce the erucic acid content in different rapeseed-mustard crops. Canadian rapeseed breeders were first to develop cultivars with low erucic acid (<2%) in B. napus and B. rapa (Downey and Craig, 1964). Combining low erucic acid trait with low glucosinolate content (<30 μmol/g defatted meal) in the meal subsequently aided the development of canola quality rapeseed cultivars. Similar success was achieved in B. juncea with the discovery of low erucic acid (<2%) genotypes (Zem 1 and Zem 2) in Australia (Kirk and Oram, 1981). Only a few varieties and hybrids of canola mustard are currently under cultivation. However, linkage drag continues to be an issue as low erucic acid donors (Zem 1 and Zem 2) and their derivatives are late maturing, small seeded, and possess low seed oil content (Banga et al., 2015). Traditional breeding methods have not been able to eliminate limitations of low oil in the presently available low erucic acid mustard varieties. Transferring the low erucic acid trait into agronomically superior genotypes is difficult, since the trait is double recessive and fatty acid composition is defined by the genotype of the embryo. Each cycle of backcrossing requires one generation of selfing after every backcross. Plants carrying low erucic acid alleles in the self-progenies are selected on the basis of half-seed analysis for the next cycle of recurrent backcrossing to the recurrent parent. A countless number of half seeds must be analyzed in each generation and this procedure is beyond the analytical capacity of most laboratories in mustard-growing countries. Although many rapid screening techniques (e.g., Near-infrared spectroscopy) are now available (Kaur et al., 2016; Sen et al., 2018), these require a large sample size and are not suitable for the analysis of single seeds. The development of functional markers with the ability to differentiate between homozygous and heterozygous states of plants is considered important. It will obviate the wet chemistry analysis for fatty acid profiling and the necessity of selfing after every generation of backcrossing.

The genes involved in the biosynthesis of very long-chain fatty acids (VLCFAs) are well known. Long-chain fatty acids are synthesized de novo with two enzyme systems, acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACCase) and fatty acid synthase (FAS) complex. ACCase catalyzes the formation of malonyl-acyl carrier protein (ACP) (Harwood, 1996), whereas FAS complex catalyzes the elongation of malonyl-ACP into palmitoyl-ACP with seven rounds of four sequential reactions. Elongation of palmitoyl-ACP results in stearoyl-ACP, which is then saturated by plastidal stearoyl-ACP desaturase to produce oleoyl-ACP. The removal of ACP by acyl-ACP thioesterase (FatA/FatB) marks the termination of elongation in plastids and leads to the formation of free fatty acids such as palmitic, stearic, and oleic acid. Most of the free fatty acids are transported to endoplasmic reticulum, where oleic acid is desaturated and elongated to produce polyunsaturated fatty acid and VLCFA. Fatty acid desaturases (FAD) encoded by FAD genes catalyze the desaturation reaction (Kunst et al., 1992; Miquel and Browse, 1992), whereas β-ketoacyl-CoA synthase (KCS) catalyzes the first step of two rounds of four sequential chain elongation reactions (James et al., 1995). This enzyme is encoded by the fatty acid elongase 1 (FAE1) gene in Brassica. Mutation in the FAE1 genes impairs the activity of KCS enzyme (Katavic et al., 2002). Orthologs of the FAE and FAD genes were also reported in different oilseed Brassica species (Barker et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2015; Tang et al., 2019; Xue et al., 2020). B. juncea (AABB) and B. napus (AACC) possess two homologs of FAE1.1 and FAE1.2 genes. These show more than 99% nucleotide identity. High homologies exist between the gene sequences of the gene from B. juncea, B. rapa, and B. napus (Zeng and Cheng, 2014). Four and three single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in FAE1.1 and FAE1.2 differentiated low erucic genotypes from high erucic acid ones in B. juncea (Gupta et al., 2004). A total of 26 SNPs caused changes in 13 amino acids in B. rapa (Yan et al., 2015). Deletion of two bases in C homolog in B. napus produced low erucic acid phenotype (Fourmann et al., 1998). Single nucleotide primer extension (SNuPE) assays have been used to track allelic variation in the FAE1 gene (Gupta et al., 2004), but these are expensive and tedious to implement. Cleaved amplified polymorphic sequences were also used to characterize FAE1.1 and FAE1.2 alleles in B. juncea (Saini et al., 2016), but CAPS markers are dominant and these fail to identify recessive alleles in heterozygous state. Recently, Saini et al. (2019) have reported PCR markers based on the sequence variation in the promoter regions of the FAE1. These are gel-based markers. A marker-assisted breeding program requires simple but robust molecular assays that benefit from economies of scale. Kompetitive allele-specific PCR (KASPar) genotyping assay is considered as an ideal approach to hasten the breeding processes through rapid genotyping of thousands of samples at very low error rates (Chen et al., 2010; Kumpatla et al., 2012). In this study, we report the development of KASPar assay for high-throughput genotyping of erucic acid content. These allele-specific assays were developed on the basis of SNPs at positions 735 and 1,476 from A and B homologs of FAE1.1 and FAE1.2. These SNPs were identified on the basis of Sanger sequencing of cloned FAE1.1 and FAE1.2 genes from both the high and low erucic acid accessions of B. juncea and the progenitor species: B. rapa and B. nigra. All these sequences have been submitted to the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) and included in Supplementary File 1. The practical utility of the designed KASPar assays was established by validating these in a germplasm collection and a segregating backcross progeny varying for erucic acid contents.

A total of 29 pure lines of B. juncea (25) and inbred lines of its genome donor species, B. rapa (2) and B. nigra (2) were selected for this study (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1). Selected genotypes varied for erucic acid content (0–52%) in the oil and represented a broad spectrum of geographic and genetic diversity. The FAE1 gene was cloned and sequenced from four genotypes of B. juncea, two of B. rapa and one of B. nigra. A backcross progeny 1 (BC1) was developed from a cross of PBR357/RLC3//PBR357 [(High × Low) × High erucic genotype(s)] through hand pollinations. It was raised under field conditions and used to validate KASPar markers in segregating generation.

Fatty acid profile was determined through gas chromatography by following standard protocols (Appelqvist, 1968). For this fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) were injected in a fused silica capillary CP-SIL 88 column (50 mm × 0.25 mm id) fitted on gas chromatograph (Varian CP-3800, United States). Temperatures of oven, injector, and Flame ionisation detector (FID) were maintained at 200, 230, and 250°C, respectively. The peak identity of different fatty acids was determined by analyzing the FAME mix (Supelco Incorporation, United States) as a reference under similar conditions. The relative area percentage was used for estimating the identified fatty acids.

In Brassica, embryo genotype determines the composition of fatty acids. This mode of inheritance allows non-destructive estimation of fatty acids at a single seed level. Brassica seeds possess conduplicate cotyledons, where the inner cotyledon is attached with germ, and the outer cotyledon covers the inner one. The outer cotyledon was used for ascertaining the fatty acid composition and the inner one was retained for raising into adult plant. To follow half-seed method, the seeds were placed on moistened filter paper in petriplates at 25 ± 2°C under dark conditions. The swollen seeds were taken out after 24 h and the outer cotyledon of each seed was separated for estimating the fatty acid composition as per the procedure described earlier.

Full-length FAE1.1 and FAE1.2 genes were isolated and cloned separately from high and low erucic acid genotypes of B. juncea along with its progenitors B. rapa and B. nigra. Gene-specific primers for FAE1.1 and FAE1.2 were designed by using previously available sequence information (NCBI Gene Accession nos. AJ558197.1 and AJ558198.1). Primers FAE1.1 AR (forward-TGACGTCATAGTGTTAGGCGT and reverse TTTGGCACCTTTCATCGGAC) and FAE1.2 BR (forward-ACGAAAGAGAGCAAACATCATTT and reverse-CGACA3 ACACACTGAGCAAT) were got synthesized from IDT, Germany. Thymine/Adenine (TA) cloning kit was used for cloning the amplicons in pGEM-T Easy Vector followed by sequencing with forward and reverse primer of M13. At least five clones from each genotype were sequenced by Sanger dideoxy chain termination method on capillary electrophoresis system (ABI 3730XL, Applied Biosystems, United States). Sanger sequencing was outsourced to the Eurofins Genomics India Pvt. Ltd, India. Vector contamination was removed through VecScreen tool1. The consensus sequences were obtained through the Geneious software (Kearse et al., 2012).

Differentiating SNPs were identified by aligning the sequences of FAE1.1 and FAE1.2 genes isolated from high erucic and low erucic acid accessions of B. juncea and its progenitor species by sequence alignment tool of the Geneious software.

Gene-specific KASPar assays were manually designed for FAE1.1 and FAE1.2. SNPs at positions 735 and 1,476 for FAE1.1 and FAE1.2 were used for the purpose (Table 2). Thermodynamic properties of the designed primers were analyzed by using software Vector NTI version 11.5.32.

Kompetitive allele-specific PCR reaction mix constituted 2 μl DNA (ng), 1.944 μl KASP reagent (LGC Genomics, Beverly, MA, United States) and primer mix of 0.056 μl. PCR was run initially for 15 min at 94°C followed by 10 cycles for 20 s at 94°C and 1 min at 65°C in touchdown mode with a decrease of 1°C in every cycle and finally 30 cycles of 20 s at 94°C and for 1 min at 55°C. The Applied Biosystems™ QuantStudio™ 12K Flex (Thermo Fisher Scientific, United States) was utilized for carrying out PCR reaction and analyzing the PCR product.

Brassica rapa accessions, QR 2 and TL 17, contained 0.2 and 42.6% erucic acid, respectively, while both the genotypes of B. nigra (UP and CN 113799) had high erucic acid. B. juncea genotypes from India varied between 0.8 and 52.3% for erucic acid in the oil. Erucic acid content of introduced mustard genotypes ranged between 0.8 and 21% (Table 1). EC 597325 and CBJ 001, of Australian and Chinese origin, respectively, exhibited low erucic acid (<2%) in the oil. The East European genotype Donskaja had intermediate erucic acid content.

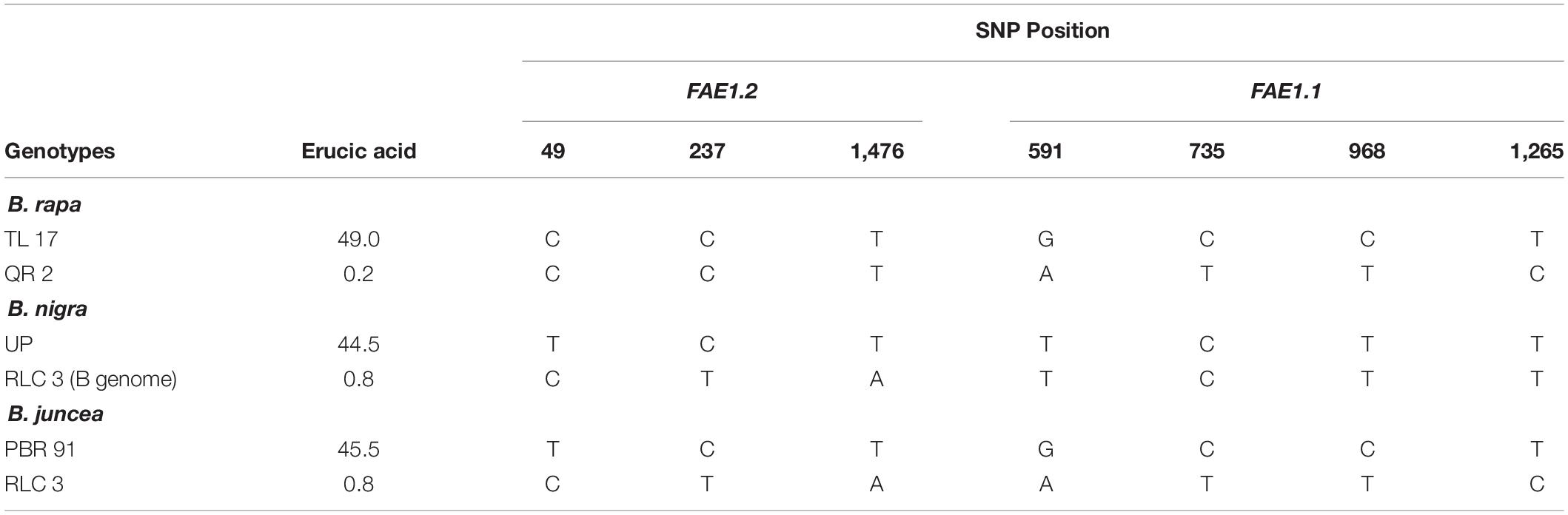

Sequence size of FAE1.1 from B. rapa cv. TL 17 (high erucic acid) and QR 2 (low erucic acid genotype) was 1,521 bp. The gene(s) comprised a single exon without any intron in FAE1.1 from both the high and low erucic acid (Supplementary Figure 1). Sequence alignment of FAE1.1 indicated high similarity (97%). Nucleotide variations were recorded at eight positions (Supplementary Figure 2). These variations manifested into seven transitions and one transversions. A total of 506 amino acids were encoded by messenger RNA (mRNA) of FAE1.1 gene. Amino acid sequence comparison revealed that amino acid changes at three positions (Supplementary Figure 2). Four SNPs at positions 591, 735, 968, and 1,265 caused transition types of changes and were common across the available database. KASPar primers were designed only at position 735.

Sequence of B. nigra genotype, UP with high erucic acid content, was compared with the B homolog from mustard genotype, RLC3 with low erucic acid. FAE1.2 gene had a sequence length of 1,521 bp with one exon (Supplementary Figure 3). Sequence alignment revealed high homology (99%) between FAE1.2 gene sequences isolated from B. nigra and B. juncea. Nucleotide changes were identified only at three positions. These variations were indicative of two transitions and one transversion (Supplementary Figure 4). Translated mRNA sequence of FAE1.2 encoded 506 amino acids. A comparison of mRNA amino acid sequences of high/low erucic acid Brassica genotypes indicated changes only at single position as compared to the changes at three positions for the nucleotide sequence of the gene (Supplementary Figure 4). Gene sequences of FAE1.2 deciphered in our studies were also aligned with the corresponding sequences available in public domain (NCBI: AJ 558198.1). All the three identified SNPs at positions T/C (49), C/T (237), and T/A (1,476) were consensus. SNP at position 1,476 was selected for developing KASPar primer.

Four common SNPs distinguishing high/low erucic acid FAE1.1 gene were observed in B. rapa and B. juncea gene sequences. Likewise, three SNPs for high/low erucic acid identified for gene FAE1.2 in B. nigra were also present in B. juncea. These SNPs were common across the ploidy and present in all the test germplasm, irrespective of geographic and genetic origin (Table 3 and Supplementary Figure 5).

Table 3. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) differentiating low/high erucic acid (FAE1.1 and FAE1.2) in Brassica species.

The KASPar assay for FAE1.1 was designed for SNPs at position 735 and validated over 29 accessions of B. rapa, B. nigra, and B. juncea (Table 4). Genotypes with low erucic acid formed a cluster distinct from the genotypes with high erucic acid (Figure 1A). Amplification was not observed for B. nigra genotypes, indicating the A homolog specificity for the assay developed. KASPar assay specific to the gene FAE1.2 was designed for SNP at position 1,476. This KASPar assay was also validated on 29 genotypes and formed separate clusters for high vs. low erucic acid genotypes (Table 4 and Figure 1B). B. rapa genotypes showed no amplification, confirming the specificity of the assay for B homolog.

Figure 1. Kompetitive allele-specific PCR (KASPar) genotyping in germplasm lines and backcross population. (A) KASPar genotyping of FAE1.1 gene on pure/inbred lines: genotypes homozygous (FAE1.1) for high and low erucic acid clustered to the FAM side (Y axis: blue dots) and VIC side (X axis: red dots), respectively. (B) KASPar genotyping of FAE1.2 gene on pure/inbred lines: genotypes homozygous for high and low erucic acid (FAE1.2) clustered to the VIC side (X axis: red dots) and FAM side (Y axis: blue dots), respectively. (C) KASPar genotyping for FAE1.1 gene on BC1 population. Homozygous genotypes clustered to FAM (Y axis: blue dots) whereas heterozygotes clusterd as green dots. (D) KASPar genotypes for FAE1.2 on BC1 population. Homozygotes clustered to VIC side (X axis: red dots) whereas heterozygotes clustered as green dots.

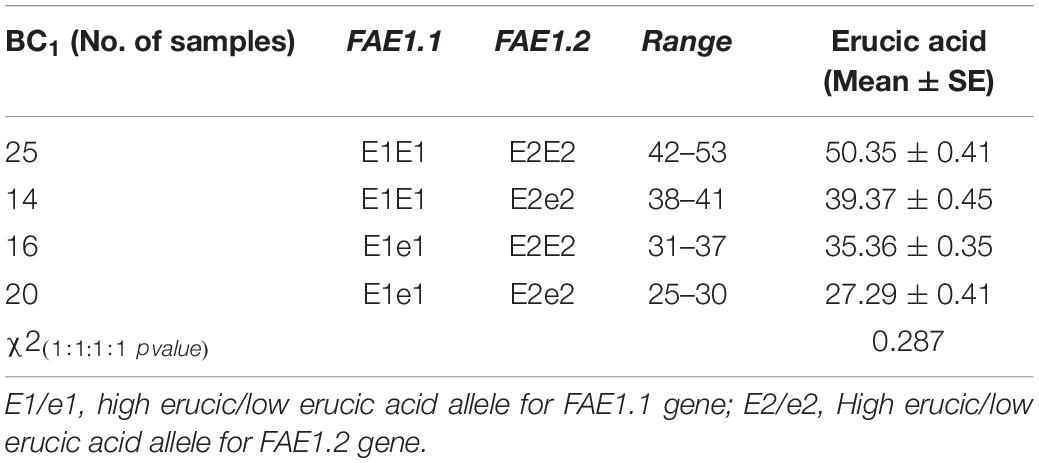

The KASPar assays were authenticated on BC1 seeds, segregating for varied erucic acid content. The seed fatty acid composition was determined by using half-seed method. The outer cotyledon of swollen seeds was harvested for fatty acid analysis, whereas corresponding inner cotyledon with germ portion was seeded to develop into the adult plant. DNA was isolated from first true leaves of plants with known fatty acid composition. The KASPar assays were used for specific amplification of FAE1.1 and FAE1.2. KASP clusters showed equivalence with the segregation expected for a BC1 progeny (Figures 1C,D). Four genotypic classes were inferred from the analysis of 75 BC1 plants (Table 5). These were E1E1E2E2 (25): E1E1E2e2 (14): E1e1E2E2 (16): E1e1E2e2 (20). Plants with genotype E1E1E2E2 possessed average erucic acid level of 50.35% and plants heterozygous at both the loci (E1e1E2e2) had average erucic acid content of 27.29%. The remaining two genotypic classes, heterozygotes for either of two alleles, E1E1E2e2 and E1e1E2E2 showed erucic acid contents of 39.37 and 35.36%, respectively. E1 allele contributed more than that of the E2 allele. The gene action with an additive effect was indicated for the erucic acid phenotype. Heterozygotes, E1e1E2e2 showed an intermediate phenotype.

Table 5. Genotyping for FAE1.1 and FAE1.2 genes and their association with erucic acid in B. juncea.

Genetic modification of oil quality is now a major breeding objective in mustard. However, most breeding groups are following traditional crop-breeding methods with little application of marker-assisted breeding in India. This is in spite of the availability of many high-density linkage maps and molecular marker systems in the species (Pradhan et al., 2003; Ramchiary et al., 2007; Panjabi et al., 2008; Yadava et al., 2012). KCS enzyme encoded by the FAE1 is involved in one of the step for the synthesis of erucic acid from oleic acid. The mutation in coding region of the FAE1 gene impairs its activity and results in drastic reduction of erucic acid (Katavic et al., 2002). Molecular markers, SNuPE (Gupta et al., 2004), and CAPS (Saini et al., 2016) for tracking the allelic variation for the FAE1 gene, have been developed in B. juncea. Recently, a PCR-based marker system has been developed, which exploits the variation in the promoter region of the FAE1 (Saini et al., 2019). None of these systems allow high throughput and cost-effective genotyping. It is, thus, important to develop breeder friendly and robust marker system.

We independently isolated FAE1.1 and FAE1.2 from four genotypes of B. juncea, two of B. rapa, and one of B. nigra. Cloning and gene sequencing allowed us to identify one copy each of FAE1.1 in B. rapa and FAE1.2 in B. nigra. Both the genes (FAE1.1 and FAE1.2) were also detected in allotetraploid B. juncea as it has been reported earlier (Das et al., 2002; Gupta et al., 2004; Yan et al., 2015). Comparative sequence analysis has also indicated that the coding sequences (CDSs) from the FAE1 are highly conserved with high similarity across the tested Brassica species. A broader genetic conservation of the gene has also been reported in the related Brassicaceae species, Sinapis alba (Zeng and Cheng, 2014). The predicted amino acid sequences of Sinapis alba have shared high homology with cultivated Brassica and Arabidopsis. Our studies have also emphasized the role of point/missense mutations in the coding region to inactivate KCS. Differences in the regulatory region or CDS due to SNPs, Insertion/deletions (InDels), and insertion of transposable elements cause dysfunction in the FAE1 (Roscoe et al., 2001; Katavic et al., 2002; Chiron et al., 2015). In contrast, a deletion of four base pairs in the FAE1 CDS from B. napus has produced a frameshift mutation and led to the formation of non-functional polypeptide with short length (Wu et al., 2008). Serine at 282 positions in the FAE1 is considered essential for elongase activity in B. napus (Katavic et al., 2002). We have also observed transition and transversion types of nucleotide variations at eight positions in FAE1.1 gene sequences of B. rapa. Of these, seven positions have been identified as transition changes and three of which cause amino acid alterations to inactivate KCS. These transition types of alterations have also been reported to cause low erucic acid in B. rapa (Wang et al., 2010). A total of 26 SNPs have caused changes in 13 amino acids and consequently loss of activity of KCS has also been reported in B. rapa (Yan et al., 2015). Whereas for B. juncea, total six nucleotide variations were detected in FAE1.1 gene and all were of transition types. Comparatively, less nucleotide variations in FAE1.1 of allotetraploid B. juncea were identified as compared to its diploid progenitor, B. rapa. Of these variations, four SNPs are common across the ploidy. These SNPs have also been reported earlier by Gupta et al. (2004) in B. juncea. For FAE1.2, nucleotide variations have occurred at the three positions both in diploid, B. nigra and allotetraploid, B. juncea. However, only one of these SNPs caused amino acid alteration that led to the loss of function of KCS. SNPs resulting from transition changes in FAE1.2 gene have also been documented in B. juncea (Gupta et al., 2004). Low sequence diversity was recorded for B homologs of the FAE1 genes in diploid and allotetraploid crop Brassica species. SNPs and InDels in gene or genome are being exploited for marker-assisted breeding (Garcés-Claver et al., 2007).

In this study, we planned to develop high throughput and breeder friendly markers capable of discriminating homozygous and heterozygous individuals in the segregating progenies. Effectiveness of the KASPar assays for high-throughput genotyping has already been documented in many crops including Brassica (Chhetri et al., 2017; Steele et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2021; Fu et al., 2021). The KASPar assays reported for FAE1.1 and FAE1.2 genes in the current communication were validated on large number of diverse genotypes and showed complete associations with erucic acid. High erucic acid B. juncea accessions are homozygous dominant for both the genes in contrast to homozygous recessive condition for low erucic acid genotypes as reported earlier (Gupta et al., 2004). Donskaja with intermediate erucic acid level is homozygous recessive for FAE1.1 and dominant for FAE1.2. This observation has explained the intermediate erucic acid levels reported earlier in East European B. juncea (Kirk and Hurlstone, 1983). The ability of our present marker system to differentiate between high vs. low erucic acid genotypes from the diverse geographic origins (Australia, India, China, East Europe, and Sweden) indicates its wider applicability. This could be largely due to involvement of Zem 1 and Zem 2 as donors for present low erucic acid cultivars of B. juncea (Potts et al., 1999; Bhat et al., 2002). These newly developed KASPar assays are codominant and could discriminate between homozygous and heterozygous states in the BC1 progeny investigated. The segregation pattern of these assays is in confirmatory with digenic additive inheritance for erucic acid (Bhat et al., 2002; Gupta et al., 2004). The ability of our marker assays to differentiate homozygous/heterozygous state of alleles in inbred/pure lines and in segregating progenies will expedite the process of marker-assisted selection for low erucic acid in B. juncea.

The KASPar assays were developed on the basis of SNP variations in the coding regions of the FAE1 genes. These assays are highly genome specific and can discriminate between heterozygous, double recessive, or double dominant states of a genotype. These can be coupled with a background selection to expedite the recovery of the recurrent parent and reduce linkage drag associated with the trait donor parent. Per sample costs are also low and a large number of samples can be processed in 1 day. Developed KASPar assays are single step, high throughput, robust, codominant, and cost-effective than gel-based markers and can be efficiently used for marker-assisted selection of low erucic acid.

The data set included in this manuscript is appended as Supplementary Material.

GK and SB conceived and coordinated the study. GK, SK, KK, KG, and MS developed gene-specific primers and cloned the genes. KSG, GK, GDK, and JK conducted genotyping. GK and KSG looked after the field experiments and the phenotypic data collection. PC, MB, and GK designed the KASPar assays. KSG and GK wrote the manuscript and SB edited it. All authors read, commented, and approved the final manuscript.

This study was financially supported by the Indian Council of Agricultural Research under the project “Consortia for Research Platform on Molecular breeding for improvement of tolerance to biotic and abiotic stresses, yield, and quality traits in crops mustard” awarded to GK.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

This manuscript is based on the thesis submitted by Karanjot Singh Gill to the Punjab Agricultural University as a partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Master of Science in Plant Breeding and Genetics (https://krishikosh.egranth.ac.in/handle/1/5810039286).

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2021.738805/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary File 1 | Nucleotide sequences of FAE1.1 (B. rapa and B. juncea) and FAE1.2 (B. nigra and B. juncea) genes in the Fast Adaptive Shrinkage Threshold Algorithm (FASTA) format.

Supplementary Figure 1 | Structure of FAE1.1 gene of B. rapa genotypes (A) TL17 (high erucic acid) and (B) QR 2 (low erucic acid).

Supplementary Figure 2 | Alignment of nucleotides and amino acids derived from gene sequences of FAE1.1 genes from high (TL17) and low erucic acid (QR 2) genotypes of B. rapa.

Supplementary Figure 3 | Structure of FAE1.2 gene. (A) B. nigra (UP: high erucic acid; B). B. juncea (RLC 3: low erucic acid).

Supplementary Figure 4 | Alignment of nucleotides and amino acids derived from gene sequences of FAE1.2 genes from high (UP) and low erucic acid (RLC 3) genotypes of B. nigra and B. juncea, respectively.

Supplementary Figure 5 | Alignment of nucleotides of FAE1.1 and FAE1.2 genes of B. juncea (PBR91: high erucic acid and RLC 3: low erucic acid).

Supplementary Table 1 | Source of diverse germplasm lines of B. juncea, B. rapa, and B. nigra.

Appelqvist, L. A. (1968). Lipids in Cruciferae: III. Fatty acid composition of diploid and tetraploid seeds of Brassica campestris and Sinapisalba grown under two climatic extremes. Plant Physiol. 21, 615–625. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1968.tb07286.x

Banga, S. K., Kumar, P., Bhajan, R., Singh, D., and Banga, S. S. (2015). “Genetics and Breeding” in Brassica Oilseeds: Breeding and Management. eds A. Kumar, S. S. Banga, P. D. Meena, and P. R. Kumar (Wallingford: CABI), 11–41. doi: 10.1079/9781780644837.0011

Barker, G. C., Larson, T. R., Graham, I. A., Lynn, J. R., and King, G. J. (2007). Novel Insights into Seed Fatty Acid Synthesis and Modification Pathways from Genetic Diversity and Quantitative Trait Loci Analysis of the Brassica C Genome. Plant Physiol. 144, 1827–1842. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.096172

Bhat, M. A., Gupta, M. L., Banga, S. K., Raheja, R. K., and Banga, S. S. (2002). Erucic acid heredity in Brassica juncea. Plant Breed. 121, 456–458. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0523.2002.731805.x

Burrows, G. E., and Tyrl, R. J. (2013). Toxic Plants of North America, 2nd Edn. New Jersey: Wiley. doi: 10.1002/9781118413425

Chen, W., Mingus, J., Mammadov, J., Backlund, J. E., Greene, T., Thompson, S., et al. (2010). “KASPar: a simple and cost-effective system for SNP genotyping” in Proceedings of Plant and Animal Genomes XVII Conference. (US). 194.

Chen, Z., Tang, D., Ni, J., Li, P., Wang, L., Zhou, J., et al. (2021). Development of genic KASP SNP markers from RNA-Seq data for map-based cloning and marker-assisted selection in maize. BMC Plant Biol. 21:157. doi: 10.1186/s12870-021-02932-8

Chhetri, M., Bariana, H., Wong, D., Sohail, Y., Hayden, M., and Bansal, U. (2017). Development of robust molecular markers for marker-assisted selection of leaf rust resistance gene Lr23 in common and durum wheat breeding programs. Mol. Breed. 37:21. doi: 10.1007/s11032-017-0628-6

Chiron, H., Wilmer, J., Lucas, M. O., Nesi, N., Delseny, M., Devic, M., et al. (2015). Regulation of Fatty acid elongation1 expression in embryonic and vascular tissues of Brassica napus. Plant Mol. Biol. 88, 65–83. doi: 10.1007/s11103-015-0309-y

Das, S., Roscoe, T. J., Delseny, M., Srivastava, P. S., and Lakshmikumaran, M. (2002). Cloning and molecular characterization of the Fatty Acid Elongase 1 (FAE1) gene from high and low erucic acid lines of Brassica campestris and Brassica oleracea. Plant Sci. 162, 245–250. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9452(01)00556-8

Downey, R. K., and Craig, B. M. (1964). Genetic control of fatty acid biosynthesis in rapeseed (Brassica napus L). J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 41, 475–478. doi: 10.1007/BF02670026

Fourmann, M., Barret, P., Renard, M., Pelletier, G., Delourme, R., and Brunel, D. (1998). The two genes homologous to Arabidopsis FAE1 co-segregate with the two loci governing erucic acid content in Brassica napus. Theor. Appl. Genet. 96, 852–858. doi: 10.1007/s001220050812

Fu, Y., Mason, A. S., Zhang, Y., and Yu, H. (2021). Identification and Development of KASP Markers for Novel Mutant BnFAD2 Alleles Associated With Elevated Oleic Acid in Brassica napus. Front. Plant Sci. 12:142. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.715633

Garcés-Claver, A., Fellman, S. M., Gil-Ortega, R., Jahn, M., and ArnedoAndrés, M. S. (2007). Identification validation and survey of a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) associated with pungency in Capsicum spp. Theor. Appl. Genet. 115, 907–916. doi: 10.1007/s00122-007-0617-y

Gupta, V., Mukhopadhyay, A., Arumugam, N., Sodhi, Y. S., Pental, D., and Pradhan, A. K. (2004). Molecular tagging of erucic acid trait in oilseed mustard (Brassica juncea) by QTL mapping and single nucleotide polymorphisms in FAE1 gene. Theor. Appl. Genet. 108, 743–749. doi: 10.1007/s00122-003-1481-z

Harwood, J. L. (1996). Recent advances in the biosynthesis of plant fatty acids. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Lipids Lipid Metab. 1301, 7–56. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(95)00242-1

James, D. W., Lim, E., Keller, J., Plooy, I., Ralston, E., and Dooner, H. K. (1995). Directed tagging of the Arabidopsis fatty acid elongation 1 (FAE1) gene with the maize transposon activator. Plant Cell 7, 309–319. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.3.309

Katavic, V., Mietkiewska, E., Barton, D. L., Giblin, E. M., Reed, D. W., and Taylor, D. C. (2002). Restoring enzyme activity in nonfunctional low erucic acid Brassica napusfatty acid elongase 1 by a single amino acid substitution.Eur. J. Biochem. 269, 5625–5631. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03270.x

Kaur, B., Sangha, M. K., and Kaur, G. (2016). Calibration of NIRS for the estimation of fatty acids in Brassica juncea. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 93, 673–680. doi: 10.1007/s11746-016-2802-0

Kearse, M., Moir, R., Wilson, A., Stones-Havas, S., Cheung, M., Sturrock, S., et al. (2012). Geneious basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics 28, 1647–1649. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199

Kirk, J. T. O., and Hurlstone, C. G. (1983). Variation and inheritance of erucic acid content in Brassica juncea. Z Pflanzenzucht 90, 331–338.

Kirk, J. T. O., and Oram, R. N. (1981). Isolation of erucic acid-free lines of Brassica juncea: indian mustard now a potential oilseed crop in Australia. J. Aust. Inst. Agric. Sci. 47, 51–52.

Kumpatla, S. P., Buyyarapu, R., Abdurakhmonov, I. Y., and Mammadov, J. A. (2012). “Genomics-assisted plant breeding in the 21st century: technological advances and progress,” in Plant Breed. ed. I. Y. Abdurakhmonov (InTech). 131–183. doi: 10.5772/37458

Kunst, L., Taylor, D. C., and Underhill, E. W. (1992). Fatty acid elongation in developing seeds of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 30, 425–434.

Miquel, M., and Browse, J. (1992). Arabidopsis mutants deficient in polyunsaturated fatty acid synthesis. Biochemical and genetic characterization of a plant oleoyl-phosphatidyl choline desaturase. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 1502–1509. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)45974-1

Panjabi, P., Jagannath, A., Bisht, N. C., Padmaja, K. L., Sharma, S., Gupta, V., et al. (2008). Comparative mapping of Brassica juncea and Arabidopsis thaliana using Intron Polymorphism (IP) markers: homoeologous relationships, diversification and evolution of the A, B and C Brassica genomes. BMC Genomics 9:113. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-113

Potts, D. A., Rakow, G. W., and Males, D. R. (1999). “Canola-quality Brassica juncea, a new oilseed crop for the Canadian prairies” in New Horizons for an old crop. Proceedings of 10th International Rapeseed Congress. (Australia).

Pradhan, A., Gupta, V., Mukhopadhyay, A., Arumugam, N., Sodhi, Y., and Pental, D. (2003). A high-density linkage map in Brassica juncea (Indian mustard) using AFLP and RFLP markers. Theor. Appl. Genet. 106, 607–614. doi: 10.1007/s00122-002-1083-1

Ramchiary, N., Padmaja, K. L., Sharma, S., Gupta, V., Sodhi, Y. S., Mukhopadhyay, A., et al. (2007). Mapping of yield influencing QTL in Brassica juncea: implications for breeding of a major oilseed crop of dryland areas. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2115, 807–817. doi: 10.1007/s00122-007-0610-5

Roscoe, T. J., Lessireb, R., Puyaubertb, J., Renardc, M., and Delsenya, M. (2001). Mutations in the fatty acid elongation 1 gene are associated with a loss of L-ketoacyl-CoA synthase activity in low erucic acid rapeseed. FEBS Lett. 492, 107–111. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(01)02243-8

Saini, N., Koramutla, M. K., Singh, N., Singh, S., Singh, R., Yadav, S., et al. (2019). Promoter polymorphism in FAE1.1 and FAE1.2 genes associated with erucic acid content in Brassica juncea. Mol. Breed. 39:75. doi: 10.1007/s11032-019-0971-x

Saini, N., Singh, N., Kumar, A., Vihan, N., Yadav, S., Vasudev, S., et al. (2016). Development and validation of functional CAPS markers for the FAE genes in Brassica juncea and their use in marker-assisted selection. Breed. Sci. 66, 831–837. doi: 10.1270/jsbbs.16132

Sen, R., Sharma, S., Kaur, G., and Banga, S. S. (2018). Near-infrared reflectance spectroscopy calibrations for assessment of oil, phenols, glucosinolates and fatty acid content in the intact seeds of oilseed Brassica species. J. Sci. Food Agr. 98, 4050–4057. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.8919

Steele, K. A., Quinton-Tulloch, M. J., Amgai, R. B., Dhakal, R., Khatiwada, S. P., Vyas, D., et al. (2018). Accelerating public sector rice breeding with high-density KASP markers derived from whole genome sequencing of indica rice. Mol. Breed. 38:38. doi: 10.1007/s11032-018-0777-2

Tang, M., Zhang, Y., Liu, Y., Tong, C., Cheng, X., Zhu, W., et al. (2019). Mapping loci controlling fatty acid profiles, oil and protein content by genome-wide association study in Brassica napus. Crop J. 7, 217–226. doi: 10.1016/j.cj.2018.10.007

Vogtmann, H., Christian, R., Hardin, R. T., and Clandinin, D. R. (1975). The effects of high and low erucic acid rapeseed oils in diets for rats. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 45, 221–229.

Wang, N., Shi, L., Tian, F., Ning, H., Wu, X., Long, Y., et al. (2010). Assessment of FAE1 polymorphisms in three Brassica species using EcoTILLING and their association with differences in seed erucic acid contents. BMC Plant Biol. 10:137. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-10-137

Wang, X., Long, Y., Yin, Y., Zhang, C., Gan, L., Liu, L., et al. (2015). New insights into the genetic networks affecting seed fatty acid concentrations in Brassica napus. BMC Plant Biol. 15:91. doi: 10.1186/s12870-015-0475-8

Wu, G., Wu, Y., Xiao, L., Li, X., and Lu, C. (2008). Zero erucic acid trait of rapeseed (Brassica napusL.) results from a deletion of four base pairs in the fatty acid elongase 1 gene. Theor. Appl. Genet. 116, 491–499. doi: 10.1007/s00122-007-0685-z

Xue, Y., Jiang, J., Yang, X., Jiang, H., Du, Y., Liu, X., et al. (2020). Genome-wide mining and comparative analysis of fatty acid elongase gene family in Brassica napus and its progenitors. Gene 747:144674. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2020.144674

Yadava, S. K., Arumugam, N., Mukhopadhyay, A., Sodhi, Y. S., Gupta, V., Pental, D., et al. (2012). QTL mapping of yield-associated traits in Brassica juncea: meta-analysis and epistatic interactions using two different crosses between east European and Indian gene pool lines. Theor. Appl. Genet. 125, 1553–1564. doi: 10.1007/s00122-012-1934-3

Yan, G., Li, D., Cai, M., Gao, G., Chen, B., Xu, K., et al. (2015). Characterization of FAE1 in the zero erucic acid germplasm of Brassica rapaL. Breed. Sci. 65, 257–264. doi: 10.1270/jsbbs.65.257

Keywords: KASPar, erucic acid, SNPs, FAE genes, allotetraploid

Citation: Gill KS, Kaur G, Kaur G, Kaur J, Kaur Sra S, Kaur K, Gurpreet K, Sharma M, Bansal M, Chhuneja P and Banga SS (2021) Development and Validation of Kompetitive Allele-Specific PCR Assays for Erucic Acid Content in Indian Mustard [Brassica juncea (L.) Czern and Coss.]. Front. Plant Sci. 12:738805. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.738805

Received: 09 July 2021; Accepted: 20 October 2021;

Published: 15 December 2021.

Edited by:

Harsh Raman, New South Wales Department of Primary Industries, AustraliaReviewed by:

Anket Sharma, University of Maryland, College Park, United StatesCopyright © 2021 Gill, Kaur, Kaur, Kaur, Kaur Sra, Kaur, Gurpreet, Sharma, Bansal, Chhuneja and Banga. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gurpreet Kaur, Z3VycHJlZXRrYXVyQHBhdS5lZHU=; orcid.org/0000-0002-0660-9592

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.