94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Plant Sci. , 04 November 2021

Sec. Plant Nutrition

Volume 12 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.726186

An increase in plant biomass under elevated CO2 (eCO2) is usually lower than expected. N-deficiency induced by eCO2 is often considered to be a reason for this. Several hypotheses explain the induced N-deficiency: (1) eCO2 inhibits nitrate assimilation, (2) eCO2 lowers nitrate acquisition due to reduced transpiration, or (3) eCO2 reduces plant N concentration with increased biomass. We tested them using C3 (wheat, rice, and potato) and C4 plants (guinea grass, and Amaranthus) grown in chambers at 400 (ambient CO2, aCO2) or 800 (eCO2) μL L−1 CO2. In most species, we could not confirm hypothesis (1) with the measurements of plant nitrate accumulation in each organ. The exception was rice showing a slight inhibition of nitrate assimilation at eCO2, but the biomass was similar between the nitrate and urea-fed plants. Contrary to hypothesis (2), eCO2 did not decrease plant nitrate acquisition despite reduced transpiration because of enhanced nitrate acquisition per unit transpiration in all species. Comparing to aCO2, eCO2 remarkably enhanced water-use efficiency, especially in C3 plants, decreasing water demand for CO2 acquisition. As our results supported hypothesis (3) without any exception, we then examined if lowered N concentration at eCO2 indeed limits the growth using C3 wheat and C4 guinea grass under various levels of nitrate-N supply. While eCO2 significantly increased relative growth rate (RGR) in wheat but not in guinea grass, each species increased RGR with higher N supply and then reached a maximum as no longer N was limited. To achieve the maximum RGR, wheat required a 1.3-fold N supply at eCO2 than aCO2 with 2.2-fold biomass. However, the N requirement by guinea grass was less affected by the eCO2 treatment. The results reveal that accelerated RGR by eCO2 could create a demand for more N, especially in the leaf sheath rather than the leaf blade in wheat, causing N-limitation unless the additional N was supplied. We concluded that eCO2 amplifies N-limitation due to accelerated growth rate rather than inhibited nitrate assimilation or acquisition. Our results suggest that plant growth under higher CO2 will become more dependent on N but less dependent on water to acquire both CO2 and N.

Approximately 90% of plant dry matter consists of C and O (Epstein and Bloom, 2005), mainly derived from atmospheric CO2. Higher atmospheric CO2 concentrations have the potential to increase plant biomass because (1) CO2 is the substrate for photosynthesis in plants, and (2) the photosynthetic rate is not yet saturated under the current ambient CO2 concentration (aCO2), particularly in C3 plants (Lemonnier and Ainsworth, 2018). However, plant growth enhancement under elevated CO2 (eCO2) is almost always lower than expected (Kimball et al., 1993; Ainsworth and Long, 2005). It is frequently pointed out that the reason for this growth shortness is that plants under eCO2 suffer from N-deficiency. Hence the growth is more limited by N compared with aCO2 treatments (Poorter et al., 1997; Cotrufo et al., 1998; Gifford et al., 2000; Taub and Wang, 2008; Feng et al., 2015). To fully realize the effects of CO2 fertilization, such eCO2-induced N-limitation must be overcome. Therefore, it is critical to clarify why plants are more prone to N deficiency under eCO2 treatments (Ainsworth and Long, 2005).

Here, we tested three hypotheses to elucidate the cause of eCO2-induced N-limitation: (1) eCO2 may inhibit the reduction of to by the shortage of reductants, such as NADH, with lower photorespiration, resulting in nitrate accumulation instead of organic-N shortage in plant tissues (Rachmilevitch et al., 2004; Bloom et al., 2010, 2012; Rubio-Asensio et al., 2015); (2) eCO2 may decrease nitrate acquisition via reduced transpiration with lower stomatal conductance as transpiration is the main driving-force for movement in the soil (Conroy, 1992; Taub and Wang, 2008; McGrath and Lobell, 2013; Feng et al., 2015); and (3) stimulation of photosynthesis under eCO2 may directly increase carbohydrate production, and thus, the N concentration in the tissue may decrease as a growth dilution effect unless N acquisition by the plant increases accordingly (Poorter et al., 1997; Gifford et al., 2000; Taub and Wang, 2008).

If hypotheses (1) is responsible for the eCO2-induced N-limitation, partially feeding with instead of may alleviate it because of less reductant requirement. Hypothesis (2) is also true when the N source for plants is because its movement in soil is highly dependent on transpiration-driven mass flow. Taub and Wang (2008) pointed out that the decrease in concentration under elevated CO2 is the highest for macronutrients that are supplied to the roots by transpiration-driven mass flow (nitrate-N, Mg, and Ca) and it is the least for those most dependent on diffusion through the soil (P and K). Therefore, feeding with , which is similar to K+ in the soil, may allow plant N acquisition to be less affected by lowered transpiration. On the contrary, when hypothesis (3) can explain the N-limitation, an important issue is whether lowered N concentration at eCO2 actually limits the growth or not.

To examine these hypotheses, we compared soil-grown plants fed with nitrate or urea, which releases in the soil environment. Because is readily oxidized to by soil microbes, urea and nitrate were applied weekly to maintain fresh released from it. This was not intended to completely control or as the sole N source as in hydroponics, but to provide reduced-N in addition to for application to field crops grown in soil. Further, we used various monocotyledonous (wheat, rice, and guinea grass) and dicotyledonous (potato and Amaranthus) plants that employ C3 (wheat, rice, and potato) or C4 (guinea grass and Amaranthus) photosynthesis mechanisms to examine whether the effects of eCO2 on nitrate assimilation and acquisition differ between C3 or C4 plants. This is because C4 plants have inherently less photorespiration and relatively smaller stomatal openings compared with C3 plants (Imai and Okamoto-Sato, 1991; Ward et al., 1999; Cousins and Bloom, 2003; Lambers et al., 2008). Using the suitable N-form based on the obtained results, we further quantified the growth responses of wheat and guinea grass as representatives of C3 and C4 plants, respectively, against N supply at each CO2 value. To date, such attempts have been rarely made, as most studies have assessed the qualitative results of high contrasts (e.g., high N vs. low N).

Here, we attempted to answer the following questions:

1) Does eCO2 inhibit nitrate assimilation or nitrate acquisition, or both?

2) Is the growth of plants fed with reduced-N (i.e., urea) greater than those fed with nitrate under eCO2?

3) What is the quantity of N supply that is required for maximum plant growth at eCO2?

In addition, we paid special attention to the water-use efficiency (WUE) at the individual plant level (i.e., biomass production per transpiration). This is because an increase in plant biomass is more likely responsible for WUE rather than the amount of water transpired under eCO2 (Yi et al., 2019, 2020; Yi and Yano, 2021), which hardly occurs under current aCO2 treatments except an improvement in nocturnal transpiration (Coupel-Ledru et al., 2016). In this study, we aimed to explore how to improve eCO2-induced N-limitation by answering the above questions.

Wheat (Triticum aestivum L. “Ayahikari”), rice (Oryza sativa L. “Nipponbare”), and potato (Solanum tuberosum L. “Irish Cobbler”) were selected to represent C3 plants, and guinea grass (Panicum maximum Jacq. “Natsukaze”) and Amaranthus spp. (Tusrushin seeds, Co., Ltd., Japan) were selected to represent C4 plants. Seeds were sown into trays filled with vermiculite and grown in controlled environment chambers (LPH-410 SPC, Nippon Medical and Chemical Instruments Co., Ltd., Japan) with the following conditions: light intensity, 400 μmol m−2 s−1; relative humidity, 60%; temperature, 30/25°C (day/night); and photoperiod, 14/10 h (day/night). Potato tubers were cut into ~6.45 g pieces, buried in the tray, and sprouted in a controlled-environment room with the following conditions: light intensity, 150 μmol m−2 s−1; relative humidity, 70%; temperature, 24/24°C (day/night); and photoperiod, 12/12 h (day/night). After sprouting to ~5 cm in length, the tuber pieces were placed in the same chamber as the seedlings of the other species. Before transplanting, each seedling received 21 ml of a nutrient solution (Hyponex liquid fertilizer, Hyponex Japan Co., Ltd., Japan) diluted at 1/1,000 with tap water, and sprouted potato tuber pieces received 25 mL of the nutrient solution diluted at 1/500 with tap water.

The seedlings of each species were then transplanted into 1-L pots (11.3 × 14.0 cm, diameter × depth; one plant per pot) without holes for drainage, and were filled with 643 g of dry Andosol, in which 0.32 g of potassium chloride (60.0% K2O) and 5.05 g of calcium superphosphate (17.5% P2O5) were uniformly mixed per pot. N was applied weekly using aliquots of 1 M NaNO3 or 1 M urea diluted with distilled water to achieve a final N content of 0.19 g per pot, 0.03 g of N at transplanting, 0.03 g of N at 7 d after transplanting (DAT), 0.05g of N at 14 DAT, and 0.08 g of N at 21 DAT. The split application was intended to supply weekly fresh ammonium ions released from urea as previously supplied ones were readily oxidized to nitrate in the soil. We observed that the half-life of ammonium-N was ~10 d in the moistened soil without plants when urea was applied. Each plant was grown using two chambers [light intensity, 400 μmol m−2 s−1; relative humidity, 60%; temperature, 27/17°C (day/night); and photoperiod, 12/12 h (day/night) at ~400 μL L−1 for aCO2 and 800 μL L−1 for eCO2]. The actual CO2 concentration (mean ± SE during the growth period) monitored in each chamber was 397 ± 9 μL L−1 (day) and 569 ± 12 μL L−1 (night) under aCO2, and 749 ± 10 μL L−1 (day) and 711 ± 11 μL L−1 (night) under eCO2. The plants and CO2 concentrations were switched weekly between the two chambers to minimize any potential chamber effects. Each plant was grown for 28 d and then harvested.

Sampling was conducted twice, at transplanting and harvesting, to conduct growth analysis (Hunt et al., 2002), in which relative growth rate (RGR), net assimilation rate (NAR), and leaf area ratio (LAR) were calculated using the following equations (Saeki, 1965):

where, W1: dry weight at transplanting, W2: dry weight at harvesting, LA1: leaf area at transplanting, LA2: leaf area at harvesting, t1: day of transplanting, and t2: day of harvesting. Leaf area and root length were measured immediately after sampling using WinRHIZO Pro LA2400 (Regent Instruments Inc., Canada) before drying. The leaves, stems or leaf sheaths, and roots were separately dried in an oven at 80°C for 48 h and then weighed. After drying, each plant part was separately ground to powder for chemical analysis.

Wheat (T. aestivum L. “Ayahikari”) and guinea grass (P. maximum Jacq. “Natsukaze”) were used. The growth conditions were the same as those described in Experiment 1, except for the N-fertilizer application. Using 1 M NaNO3 solution, 8 levels of N supply rates were prepared at transplanting (0, 0.02, 0.03, 0.06, 0.13, 0.19, 0.26, and 0.32 g N per pot). Each plant was grown in controlled environment chambers with the same conditions and growth periods used in Experiment 1. The actual CO2 concentration (mean ± SE during the growth period) monitored in each chamber was 402 ± 14 μL L−1 (day) and 526 ± 72 μL L−1 (night) under aCO2, and 831 ± 8 μL L−1 (day) and 789 ± 7 μL L−1 (night) under eCO2.

Immediately after transplanting, each pot received 417 mL of tap water to achieve 65% (v/w) of the initial soil water content. Following a previously described method (Yi et al., 2019, 2020), the daily water consumption was measured by weighing each pot covered with a transparent vinyl sheet to prevent evaporation, and then tap water was supplied to maintain the initial soil water content. The cumulative transpiration throughout the growth period was calculated in each pot using the water consumption that was recorded daily. The WUE was calculated as the total plant biomass/cumulative transpiration (Jones, 2004).

Dried and ground samples were simultaneously analyzed to determine the total C and N concentrations using an elemental analyzer (NA2500; CE Instruments, Milan, Italy). To determine the nitrate concentration in the tissues, samples of ~50 mg were extracted in 5 mL of distilled water in a hot bath at 100°C for 30 min and then centrifugated at 2600 g for 2 min. The nitrate concentration in the supernatant was colorimetrically determined according to Cataldo et al. (1975). The precipitate was collected and re-dried in an oven at 80°C for 48 h to measure the δ15N ratio. The dried precipitate from each plant part was thoroughly mixed based on the weight ratio of each part. The mixed sample for each plant was combusted in an elemental analyzer (NA2500; CE Instruments, Milan, Italy). A part of the combustion gases was introduced into an isotopic ratio mass spectrometer (Delta Plus, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. Worcester, MA, USA), and the δ15N value was determined.

Experiment 1 was organized following a factorial design with two CO2 concentrations, two N-forms, and five plant species with four biological replicates. The data were analyzed using a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), in which the sources of variance were CO2 concentration (aCO2 or eCO2), N forms (nitrate or urea), and their interactions within each species. Experiment 2 consisted of two CO2 concentrations, two plant species, and eight levels of N supply rates, and compared the growth responses of each species against N supply under each CO2 treatment. In Experiment 2, there were no biological replicates as our intention was to compare growth responses but not means. In such a case, replicating observations is a necessary sense and loses sensitivity (Barrow, 2021). The main effects of N supply and CO2 treatment within each species were analyzed using a two-way ANOVA without replication.

The RGR was not affected by the form of N fertilizer in wheat, rice, potato, and guinea grass not only under eCO2 but also under aCO2 (Table 1) without any visible symptoms, implying that toxic effects of ammonia released from urea were not detectable. As for these species, the RGR was higher under eCO2 than under aCO2. The only exception was Amaranthus, which showed a higher RGR under the nitrate-fed treatment than under the urea-fed treatment, while the effect of the CO2 level was not significant (Table 1). The increase in the RGR by CO2 enrichment was higher in C3 plants (10–20% increase) than in C4 guinea grass (~3% increase).

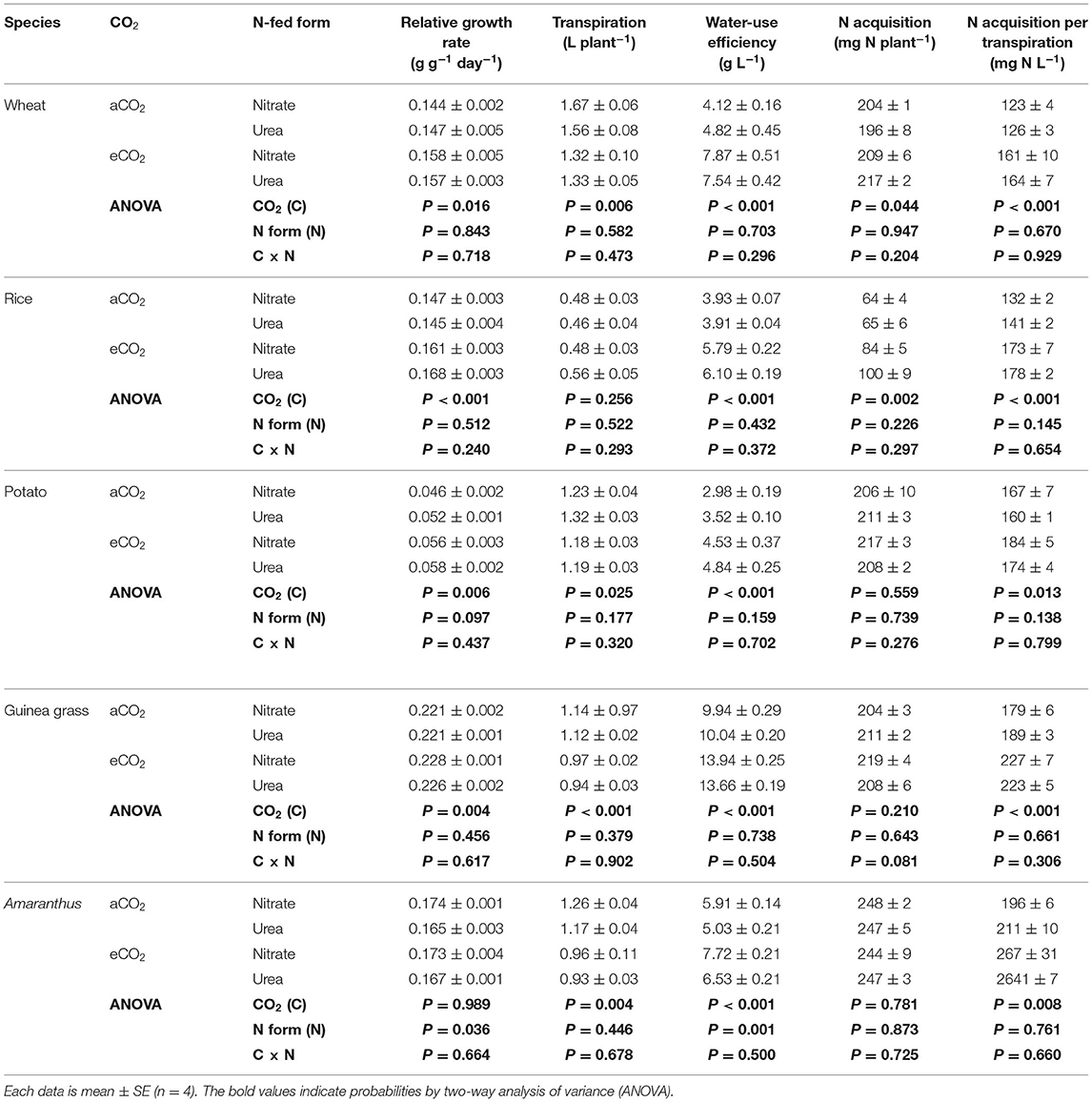

Table 1. Growth parameters of nitrate-fed or urea-fed plants in five species grown for 28 d in the chambers under ambient (aCO2) or elevated (eCO2) CO2 treatments.

Water consumption (i.e., cumulative transpiration during the 28-d experimental period) was lower under eCO2 than under aCO2 in most species except rice (Table 1). Rice increased both leaf area and root length but decreased leaf area per root length with CO2 enrichment, which was not observed in the other species (Supplementary Table 1). The WUE was remarkably enhanced under the eCO2 treatment in all species (p < 0.001), with the highest increase observed in nitrate-fed wheat (1.9-fold) and the lowest increase in nitrate-fed Amaranthus (1.1-fold). However, the form of N fertilizer did not significantly affect the WUE, except for Amaranthus (Table 1).

The amount of N acquired throughout the 28 d was calculated by subtracting the plant N content at transplanting from that at sampling in each species. The eCO2 treatment enhanced the N acquisition in wheat and rice but not in potato, guinea grass, and Amaranthus (Table 1). In all species, CO2 enrichment significantly increased the N acquisition per unit transpiration (Table 1). Changes in the leaf area and the root length, including the ratio, with CO2 enrichment (Supplementary Table 1) did not correspond to such consistent increases in the N acquisition per transpiration across the species.

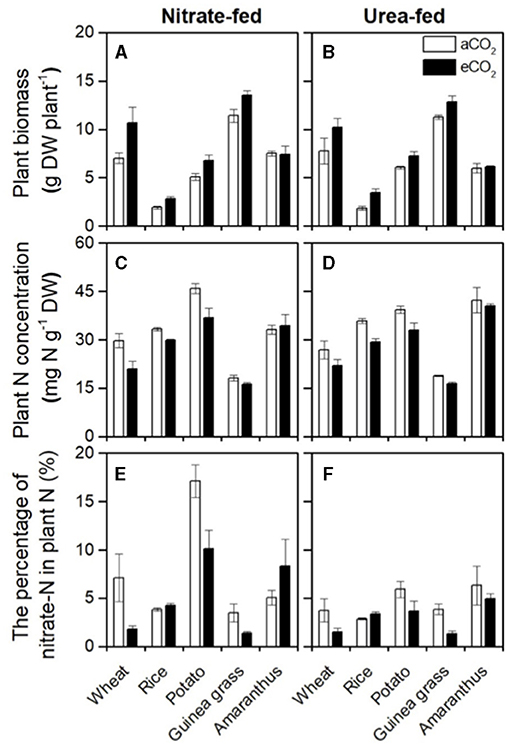

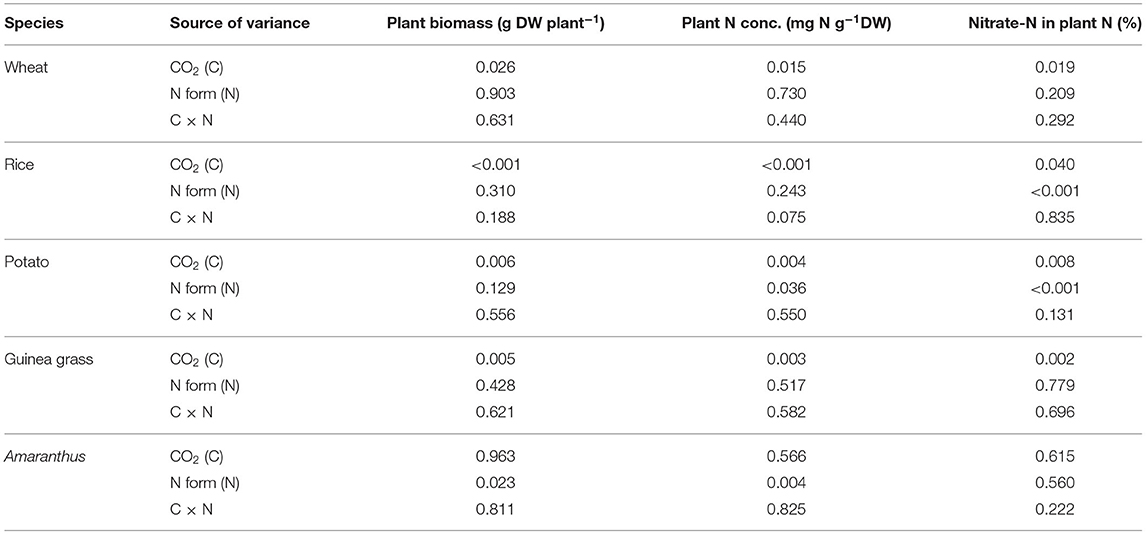

According to the RGR, eCO2 increased the plant biomass of the sampled plants (Figures 1A,B), although the form of N fertilizer did not significantly affect the biomass of each species, except Amaranthus (Table 2). As a result, 1.4, 1.7, 1.3, and 1.2-fold increases in biomass were observed in wheat, rice, potato, and guinea grass plants, respectively. The amount of biomass in each organ is shown in Supplementary Table 2.

Figure 1. Plant biomass (A,B), plant N concentration (C,D), and the percentage of nitrate-N in total N (E,F) in nitrate-fed or urea-fed plants in five species grown for 28 d in the chambers under ambient (aCO2) or elevated (eCO2) CO2 treatments.

Table 2. Probabilities by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for plant biomass, plant N concentration, and the percentage of nitrate-N in plant total N in nitrate-fed or urea-fed plants in five species grown for 28 d in the chambers under ambient (aCO2) or elevated (eCO2) CO2 treatments.

Although the foliar N concentration on the area basis was not affected by either CO2 or the form of N fertilizer in each species (Supplementary Figures 1A,B), the plant N concentration on the mass basis (Figures 1C,D), the total N (Supplementary Table 3), and organic-N (Supplementary Table 4) in each organ was considerably decreased under the eCO2 treatment in all species except Amaranthus, in which biomass was not affected by CO2 (Table 2). In addition, the plant N concentration was also significantly affected by the form of N fertilizer in potato and Amaranthus (Table 2), where the potato had a higher plant N concentration in the nitrate-fed treatment (with a ~three-fold increase in the nitrate-N percentage as shown in Figures 1E,F). In contrast, Amaranthus showed a higher N concentration under the urea-fed treatment (Figures 1C,D). However, we did not observe any differences due to the treatments in the foliar N concentration on the area basis within each species (Supplementary Figures 1A,B). The leaf mass per area was significantly increased by CO2 enrichment in each species, except in Amaranthus again (Supplementary Figures 1C,D).

The percentage of nitrate-N in total plant N was investigated to evaluate nitrate accumulation (Figures 1E,F). Urea-fed plants had a certain amount of nitrate-N (Figure 1F) due to nitrate recently oxidized from ammonium in addition to the initial amount in the soil. Nitrate-fed plants showed a relatively higher percentage than urea-fed plants, especially in the C3 plants (Figure 1E), but it was species dependent. A significant increase in the percentage was detected in rice and potato but not in the other species (Table 2). The percentage was significantly affected by CO2 enrichment in each species, except in Amaranthus (Table 2). However, CO2 enrichment could increase the percentage only in rice, and other species (wheat, potato, and rice) showed a decrease in the percentage under eCO2 compared with that under aCO2 (Figures 1E,F). In each species, CO2 enrichment could affect the percentage of nitrate-N in the shoots but not in the roots (Supplementary Table 5).

To further confirm the effect of eCO2 on nitrate assimilation, we investigated the δ15N in the residues of the plant samples after nitrate extraction. We assumed that N in the residues would approximately reflect plant organic-N, although some contamination of residual nitrate-N and removal of water-soluble organic-N might also be involved. In principle, when nitrate reductase activity (i.e., demand) is relatively lower than the amount of available substrate (i.e., supply), the enzyme preferentially catalyzes 14 over 15, resulting in a lower 15N/14N ratio in plant organic-N (lower δ15N value). Thus, the δ15N value in plant organic-N was expected to decrease when nitrate reductase activity was inhibited under the eCO2 treatment. However, all species, except rice, did not show a decrease in the δ15N values in the residues under eCO2 compared with those observed under aCO2 (Supplementary Table 5). Only rice indicated a lower δ15N value in the residues along with nitrate accumulation promoted by CO2 enrichment.

As the data in Experiment 1 indicated that CO2 enrichment did not necessarily inhibit nitrate assimilation and N acquisition but decreased the plant N concentration on a mass basis, we examined whether an increase in the N supply could improve plant growth while at the same time prevent N deficiency under CO2 enrichment. The growth response to the nitrate-N supply level was investigated using C3 wheat and C4 guinea grass to determine the quantity of N that is required for maximum growth in each CO2 treatment.

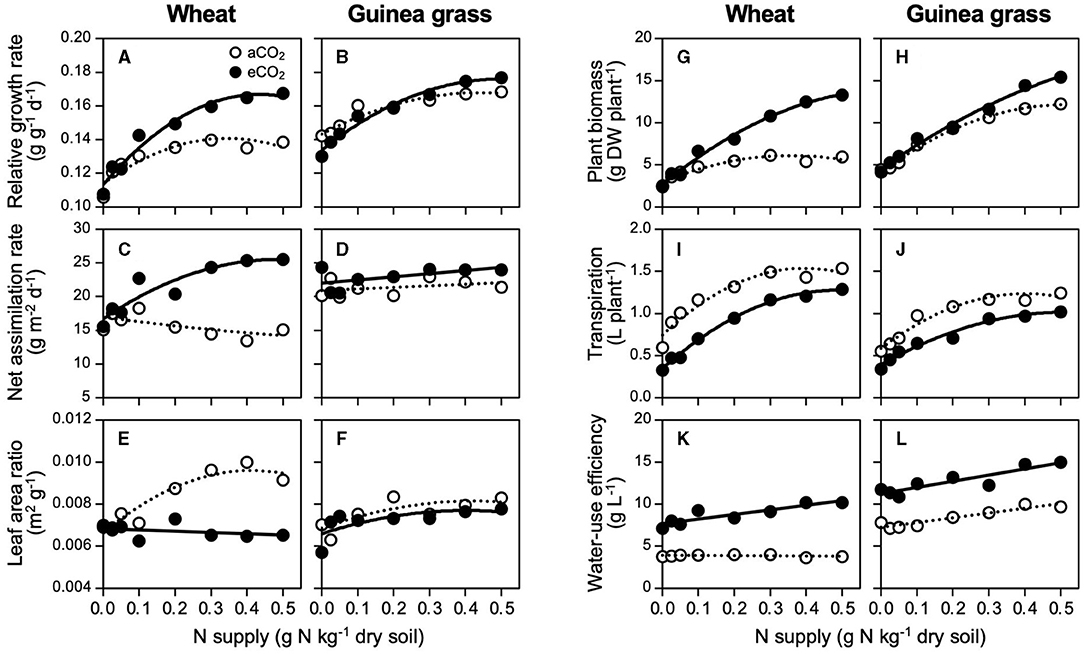

In response to the increase in N supply, both species increased their RGRs and attained maximum levels at 0.4 g N kg−1 soil for wheat in eCO2 and guinea grass in each CO2 treatment, but at a lower N supply level (0.3 g N kg−1 soil) in aCO2 wheat (Figures 2A,B). The eCO2 treatment significantly enhanced the RGR of wheat but not guinea grass (Table 3). In wheat, the enhancement of RGR by CO2 enrichment was attributable to a higher NAR (Figure 2C) rather than the LAR (Figure 2E), which supported the enhancement of foliar photosynthesis with increased N supply levels. At the highest NAR, wheat showed a higher RGR (i.e., 25 g m−2 d−1, Figure 2C) than that of guinea grass (Figure 2D). On the contrary, guinea grass showed less responses to CO2 enrichment and N supply in terms of RGR (Figure 2B), NAR (Figure 2D), and LAR (Figure 2F) than wheat.

Figure 2. Growth responses for nitrate-N supply in C3 wheat and C4 guinea grass is grown for 28 d in the chambers under ambient (aCO2) or elevated (eCO2) CO2 treatments. Relative growth rate (A,B), net assimilation rate (C,D), leaf area ratio (E,F), plant biomass (G,H), cumulative transpiration (I,J), and water-use efficiency (K,L).

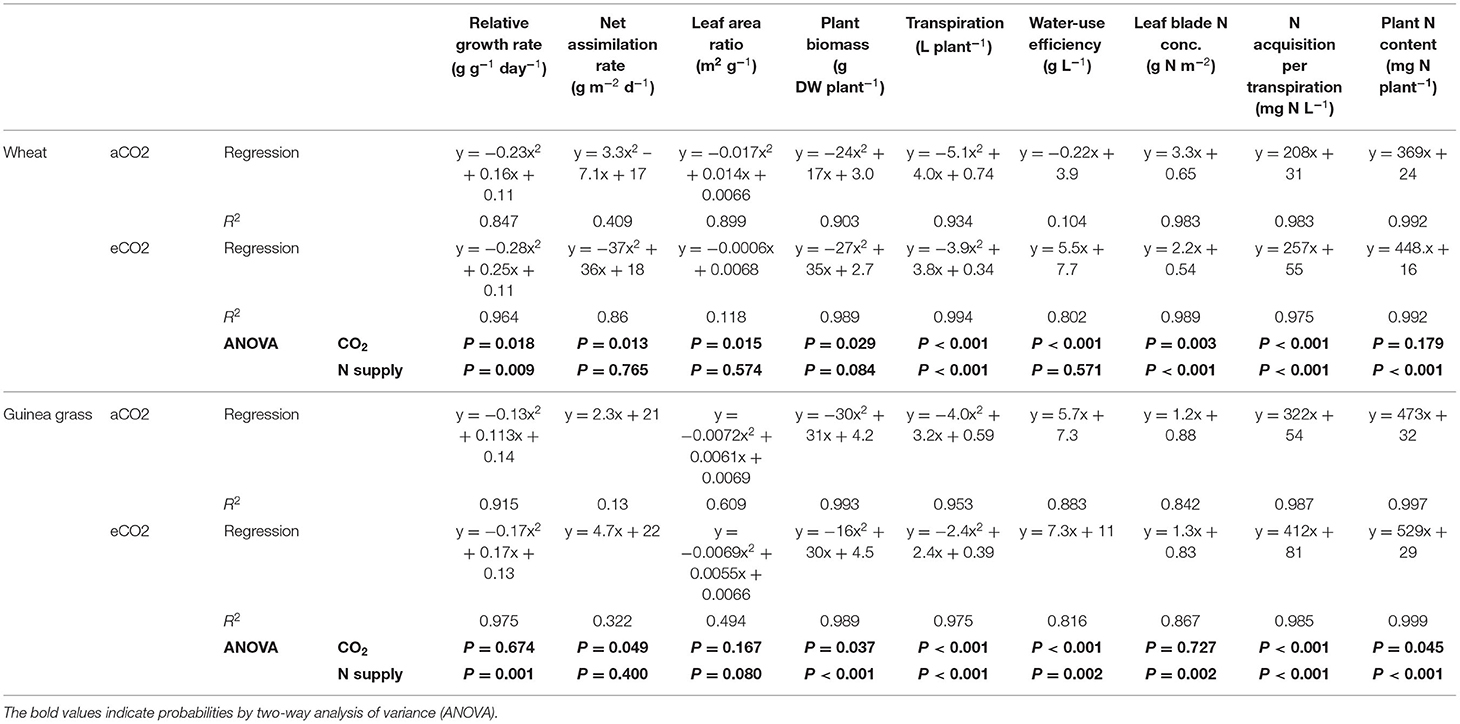

Table 3. Regression equation and coefficient of determination (R2) of each parameter against nitrate-N supply in wheat and guinea grass grown for 28 d in the chambers under ambient (aCO2) or elevated (eCO2) CO2 treatments.

The eCO2 treatment strongly enhanced the plant biomass under higher N levels, particularly in wheat, but had less of an effect on guinea grass (Figures 2G,H). As a result, CO2 enrichment resulted in a 2.2-fold increase in biomass in wheat but a small increase (i.e., by 1.3-fold) in guinea grass. Despite the increase in biomass in each species, water consumption during growth was always lower under the eCO2 treatment than under the aCO2 treatment across the N supply levels (Figures 2I,J). The lower water consumption but greater biomass was attributable to the enhanced WUE under the eCO2 treatment (Figures 2K,L) which ranged from 7 to 11 g biomass per liter of water in eCO2 wheat, remained constant at 4 g biomass per liter of water in aCO2 wheat, ranged from 11 to 15 g biomass per liter water in eCO2 guinea grass, and ranged from 7 to 10 g biomass per liter water in aCO2 guinea grass. Except for aCO2 wheat, the WUE increased under high N supply levels (Table 3).

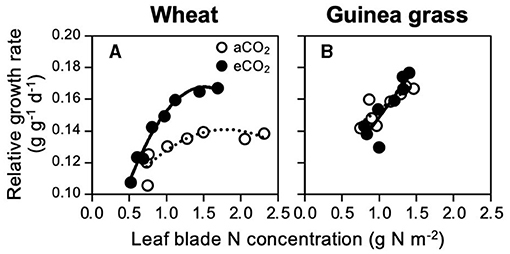

To assess if the foliar N demand for maximum growth is affected by the CO2 treatments, RGR was regressed against the foliar N concentration (Figure 3). To represent the foliar N concentration, we used the area basis unit (mg N m−2 leaf area) instead of the mass basis unit (mg N g−1 leaf dry matter) because the latter would not be suitable, especially when the leaf mass per area is affected by the CO2 treatment (Yi et al., 2020), as observed in the present study (Supplementary Figure 2). Under both CO2 treatments, wheat showed saturated RGRs against the foliar N concentration (Figure 3A), but guinea grass did not (Figure 3B). Both species showed maximum RGRs approximately at 1.5 g N m−2 irrespective of the CO2 treatments, which indicated that eCO2 would not increase the N demand for the maximum growth.

Figure 3. Relationships between relative growth rate and foliar N concentration in C3 wheat (A) and C4 guinea grass (B) grown for 28 d in the chambers under ambient (aCO2) or elevated (eCO2) CO2 treatments.

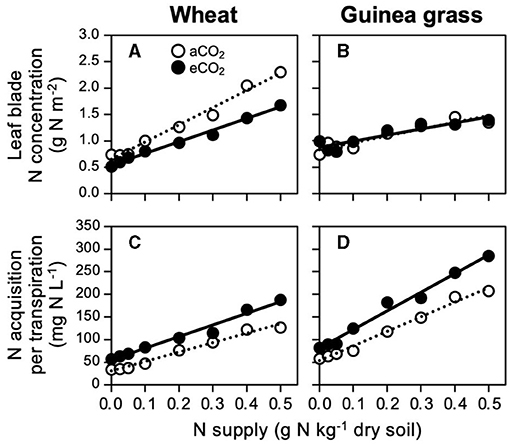

However, to reach a foliar N concentration of 1.5 g N m−2, the level of N supply to the soil differed between the CO2 treatments in wheat (Figure 4A) because the slope of the N concentration against the N supply was 1.5-fold steeper in aCO2 wheat than in eCO2 wheat (Table 3). As a result, in wheat, 0.4 g N kg−1 soil was required to reach the foliar N concentration of 1.5 g N m−2 under eCO2 treatment although a lower N supply (0.3 g N kg−1 soil) was sufficient under aCO2 treatment. In guinea grass, such a difference in the slope was very small in response to the CO2 treatments (Table 3), resulting in similar N supply requirements to reach certain foliar N concentrations (Figure 4B). The lower slope in eCO2 wheat did not result from decreased N acquisition with decreased transpiration (Figure 2I) because the eCO2 treatment enabled higher N acquisition levels per water consumption than the aCO2 treatment across all N supply levels (Figure 4C). Additionally, guinea grass also showed higher N acquisition per unit of transpired water at any N supply level at eCO2 (Figure 4D), but the slope of the regression line was steeper than wheat (Table 3). Consequently, we observed that eCO2 increased N acquisition per unit of transpired water, which did not depend only on the species (Table 1) but also on the N supply level (Figures 4C,D).

Figure 4. Relationships between foliar N concentration (A,B) or N acquisition per transpiration (C,D) and nitrate-N supply in C3 wheat and C4 guinea grass grown for 28 d in the chambers under ambient (aCO2) or elevated (eCO2) CO2 treatments.

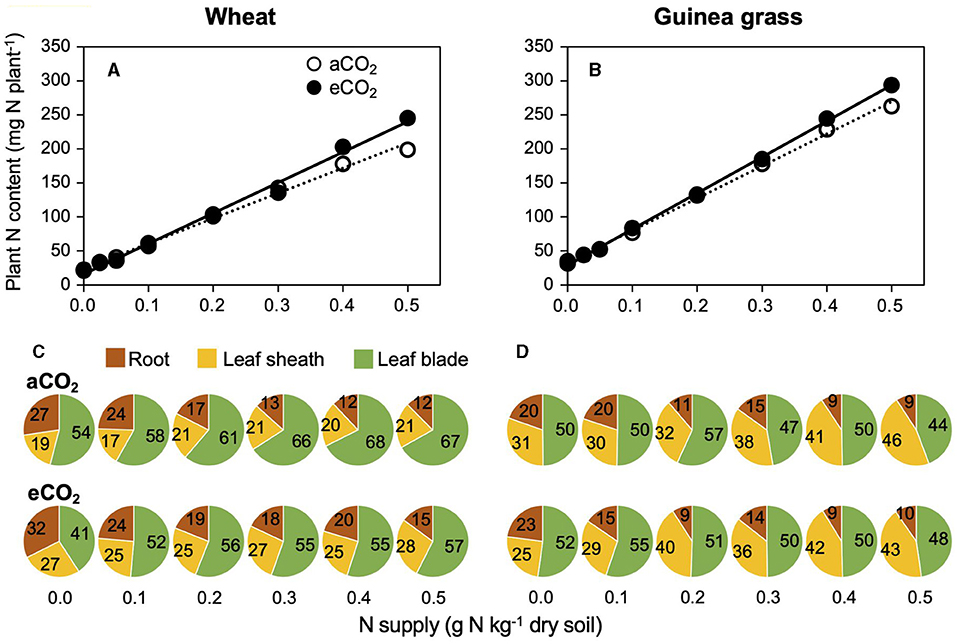

The total N content, including small N accumulation before transplanting in addition to large amounts of N, acquired during 28-day growth, was similar at lower N supply rates or higher at higher N supply rates under eCO2 treatments compared to aCO2 treatments in both species (Figures 5A,B). However, the distribution pattern of N to each organ (i.e., leaf blade, leaf sheath, and root) differed remarkably due to the CO2 and N treatments and was dependent on the species (Figures 5C,D). An increased N supply decreased the N distribution to the roots in both species, although wheat plants had relatively higher N contents in their roots than guinea grass, especially at eCO2. In response to CO2 enrichment, wheat increased the N distribution to the leaf sheath and decreased the N distribution to the leaf blade. In guinea grass, however, CO2 enrichment did not affect the N distribution in the leaves.

Figure 5. Relationships between plant N accumulation and nitrate-N supply (A,B), N distribution to each organ (C,D) in C3 wheat and C4 guinea grass grown for 28 d in the chambers under ambient (aCO2) or elevated (eCO2) CO2 treatments. Each value in the pie chart (C,D) shows the percentage within the individual plant.

Currently, there are different views on whether eCO2 inhibits nitrate assimilation in C3 plants (Bloom et al., 2020) or not (Andrews et al., 2020). Inhibition of nitrate assimilation under eCO2 results in nitrate accumulation. Hence, less organic-N could be present in plants when total N content was similar. Indeed, our results showed that eCO2 significantly decreased organic-N concentrations (Supplementary Table 4), except in Amaranthus, without an increase in biomass (Figures 1A,B). However, it is difficult to distinguish whether the apparent decrease in organic-N concentration (organic-N content per biomass) under eCO2 means a shortage of organic-N or a consequence of dilution due to biomass increase. To eliminate the effect of biomass increase, we used the percentage of nitrate-N in total N (nitrate-N content per total N content) as an index of nitrate accumulation. As a result, in most species, we found that eCO2 decreased (i.e., wheat, potato, and guinea grass) or did not change (i.e., Amaranthus) nitrate accumulation at the whole-plant level under the nitrate-fed condition (Figure 1E; Table 2), which likely supports the view of Andrews et al. (2019, 2020).

Organic-N in the shoot is derived from not only the assimilation of shoot nitrate but also the import of amino acids generated by nitrate assimilation in the root (Andrews, 1986). Thus, shoot nitrate reductase activities and shoot organic-N concentrations alone may not be accurate estimates of shoot nitrate assimilation (Bloom et al., 2020). It has also been proposed that eCO2 decreased nitrate assimilation in the shoot but enhanced it in the root (Bloom et al., 2020), which emphasizes the importance to distinguish between the shoot and the root. However, considering the percentage of nitrate-N in each organ (Supplementary Table 5), we could not confirm the enhancement of nitrate accumulation in the nitrate-fed plants under eCO2 in most species, except in rice.

Only rice showed a significant but slight increase in plant nitrate accumulation in response to CO2 enrichment (Figure 1E; Table 2), along with decreased δ15N values in the residues after nitrate extraction (Supplementary Table 5), suggesting that eCO2 inhibited nitrate reductase activities. While the results support the views of Bloom et al. (2020), an important issue is whether such nitrate accumulation could inhibit growth. We expected that if plants in the soil could receive not only but also reduced-N, such as urea and , they would be less dependent on nitrate assimilation, and consequently, the growth would improve, especially in rice, because it prefers ammonium nutrition. As expected, the percentage of nitrate-N in total N decreased in the urea-fed plants compared with that in the nitrate-fed plants (Figures 1E,F; Table 2), especially in the C3 species, including rice. Nevertheless, there was no significant improvement in the biomass (Figure 1B; Table 2) and RGR (Table 1) due to reduced nitrate accumulation in rice. Therefore, such a slight increase in nitrate accumulation would not cause growth inhibition compared with that in the urea-fed rice (Table 1). As a result, it was difficult to confirm that eCO2 limits plant growth via inhibition of nitrate assimilation in any of the five plant species used, at least under the conditions of this study.

It has been hypothesized that transpiration reduced by eCO2 may reduce nitrate-N acquisition (Taub and Wang, 2008; Feng et al., 2015; Tausz-Posch et al., 2020). This hypothesis seemed to involve an assumption that the amount of N acquired per transpired water is not affected by eCO2. Otherwise, it would be difficult to predict a decrease in N acquisition only from the decrease in transpiration. However, we found that the amount of N acquired per transpired water increased under eCO2, regardless of plant species (Table 1) and the level of N supply in wheat and guinea grass (Figures 4C,D). The results revealed that the above assumption may not be suitable. Considering that the enhancement of nitrate-N acquisition per transpiration at eCO2 was consistent among the species at p = 0.013 (Table 1), the changes in leaf area, root length, or the ratio by CO2 enrichment (Supplementary Table 1), which were not consistent among the species, would not explain the enhancement.

Furthermore, the enhancement of nitrate-N acquisition per transpiration under eCO2 was consistently observed even with no increase in the biomass not only in Amaranthus in Experiment 1 (Table 1) but also in wheat or guinea grass at lower N supply rates in Experiment 2 (Figures 4C,D). The results confirmed that enhancement was independent of the growth promotion. In fact, a parallel slope of the regression, but elevated intercept at eCO2, in each species (Figures 4C,D) suggests that eCO2 can increase the conductance of nitrate-N from soil to plant to a constant level, independent of the level of N supply that strongly affected the RGR of each species (Figures 4A,B).

In a meta-analysis using data from several free-air CO2 enrichment (FACE) experiments, Feng et al. (2015) focused on the fact that N concentrations decreased with eCO2 even when biomass did not increase (i.e., lower N content). The phenomenon was one of the reasons that they claimed a reduction in nitrate-N acquisition per transpiration under eCO2. However, in our results (lower levels of nitrate-N supply in Experiment 2), when plant biomass was comparable between eCO2 and aCO2 treatments (Figures 2G,H), N content was also comparable (Figures 5A,B). One possible reason for the discrepancy is that our measurements comprised “whole plants” at the individual level, and their results were mainly derived from “aboveground parts” at the ecosystem level. For example, in Experiment 2, wheat without N supply allocated 73% of total N to the shoots under aCO2, but only 68% of that under eCO2 (Figure 5C), even though the N content of the whole plant was similar (Figure 5A). Perhaps, a problem with FACE experiments may be the difficulty to measure the belowground parts accurately.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to clarify that eCO2 likely enhances the nitrate-N acquisition per unit transpiration consistently across the species and N supply levels by measuring cumulative transpiration precisely at the individual plant level, although a similar phenomenon was also observed by Houshmandfar et al. (2018) in wheat at a field level. Consequently, we could not confirm that nitrate-N acquisition decreases under eCO2, despite the lower transpiration observed in various species. Therefore, our results indicated that the N concentration decreased under eCO2 (Figures 1C,D), but the reason could not be explained by a lower N acquisition even if transpiration was lowered by CO2 enrichment.

The commonly observed decline in plant N concentration under eCO2 treatments has frequently been interpreted as a dilution effect (Poorter et al., 1997; Gifford et al., 2000; Taub and Wang, 2008; Tausz-Posch et al., 2020), which results from a higher carbon assimilation rate than N acquisition rate (i.e., growth dilution). Consequently, plant tissue N concentrations usually decrease under eCO2 at both the foliar and whole-plant levels (Ainsworth and Long, 2005). In Experiment 1, our results clearly showed that eCO2 decreased the plant N concentration irrespective of the form of N-fertilizer, except in C4 Amaranthus (Figures 1C,D; Table 2). According to Taub and Wang (2008), biomass dilution occurs whenever there is a higher increase in the total biomass of a plant under eCO2 treatments relative to growth under aCO2 treatments than the corresponding increase in the total N. This agreed with the species investigated in the present study, including Amaranthus, which showed no significant effects of eCO2 on the plant N concentration, the biomass (Figures 1A,B; Table 2), and growth rate (Table 1). Therefore, our results fully support that the dilution effect causes a decrease in the N concentration.

However, it remained unclear if such a decrease in the N concentration limits plant growth under eCO2 treatments. In fact, the foliar N concentration on the area basis (Supplementary Figures 1A,B) revealed no effect by CO2 enrichment. Therefore, we can consider that an apparent decrease in the mass-based N concentration was merely the result of the increase in leaf mass per area due to eCO2 (Supplementary Figures 1C,D). To address this, we further investigated the growth responses of wheat and guinea grass (as C3 and C4 representatives, respectively) to nitrate-N supply under both CO2 treatments in Experiment 2.

While the problem of N-limitation under eCO2 has been highlighted (Poorter et al., 1997; Cotrufo et al., 1998; Gifford et al., 2000; Taub and Wang, 2008; Feng et al., 2015), the actual N requirement for the maximum growth under eCO2 has rarely been quantified as Conroy (1992) and Yi et al. (2020). While eCO2 significantly increased the RGR in wheat but not in guinea grass (Table 3), each species showed an increase in the RGR with a higher N supply, and then peaked when there was no longer N-limitation (Figures 2A,B). To achieve the maximum RGR, wheat required a 1.3-fold N supply under eCO2 compared with that under aCO2 (Figure 2A) accompanying a 2.2-fold biomass increase (Figure 2G). However, the N requirement by guinea grass was less affected by the CO2 treatment (Figure 2B). The results revealed that accelerated RGR by eCO2 could create a demand for more N in wheat, causing the N-limited growth unless additional N was supplied.

CO2 enrichment changed the wheat growth from LAR-dependent to NAR-dependent, in which the leaf N concentration strongly determined the RGR (Figure 3A), but this did not occur in guinea grass (Figures 2D,F). Similar results were reported by Imai and Murata (1979) using C3 plants (rice and soybean) and C4 plants (maize and Japanese millet). According to the meta-analysis by Poorter and Navas (2003), eCO2 increased NAR (+24% on average) but decreased LAR (−13% on average) across the species in vegetable growth, which seems to be consistent with eCO2 wheat (Figures 2C,E). In contrast, the growth of aCO2 wheat was LAR-dependent (Figure 2E), which is a typical trait for fast-growing species at the current CO2 level (Poorter and Navas, 2003). Despite the LAR-dependent growth in aCO2 wheat, N supply levels above 0.3 g N kg−1 soil could no longer increase the leaf area with the saturated tiller number (Supplementary Figure 3), thus, exhibiting growth limitation by CO2 rather than N as eCO2 further increased the number of tillers and leaf area.

Burnett et al. (2018) compared fast-growing domesticated annual barley with a slow-growing wild perennial relative under different levels of nutrient supply. They found that the perennial barley has a higher amino acid/sucrose ratio than the annual, implying a greater carbon source-limitation in the perennial than the annual barley. Indeed, eCO2 alleviating the source-limitation weakly increased photosynthesis in the annual but strongly increased photosynthesis and sink (tiller) development in the perennial, again suggesting that the growth was sink-limited in the annual but source-limited in the perennial (Burnett et al., 2016). Our results suggest that more N supply than the sufficient level under aCO2 along with eCO2 may alleviate the sink-limitation in wheat (Supplementary Figure 3).

It was notable that the eCO2 treatment resulted in more than a two-fold increase in wheat biomass despite the lower water consumption compared to aCO2 wheat (Figure 2I) with strongly elevated WUE (Figure 2K), which was comparable to guinea grass (Figure 2L). Such enhanced WUE, accompanied by a higher dry matter, was also observed in other species used under eCO2 in Experiment 1 (Table 1), which hardly occurs at the current CO2 because of the tight coupling between transpiration and carbon assimilation, except during an improvement to reduce nocturnal transpiration (Coupel-Ledru et al., 2016). The growth performances of wheat under eCO2 were equivalent to those of C4 guinea grass (Figures 2B,H,J,L), which revealed that eCO2 may enable C4 performances by C3 wheat without genetic alteration. Consequently, the eCO2 levels are likely to make C3 plants less dependent on water to acquire both CO2 and N but more dependent on the N supply, regardless of the N form of the fertilizer.

Although the RGR showed saturated responses against foliar N concentration in wheat (Figure 3A), the minimum N concentration for the maximum RGR was lower or similar under eCO2 than under aCO2 (Figure 3A), suggesting that the N demand at the foliar level for the maximum RGR was not necessarily increased by CO2 enrichment. Indeed, the distribution of N to the leaf blade was always lower under eCO2 than under aCO2 in wheat (Figure 5C), despite the similar whole-plant N contents between eCO2 and aCO2 (Figure 5A). The results suggest decreased foliar N demand in C3 wheat under eCO2 as a result of decreased investment in photosynthetic and photorespiratory enzymes (Davey et al., 1999; Stitt and Krapp, 1999; Gifford et al., 2000; Long et al., 2004; McMurtrie et al., 2008).

Regardless of the reduced N demand at the foliar level in wheat, eCO2 did not necessarily decrease the N requirement for the maximum RGR at the whole-plant level (Figure 2A). This could be attributed to the lower response of the foliar N concentration to N supply at eCO2 than at aCO2 (Figure 4A), which did not occur in guinea grass (Figure 4B). This interspecific difference may be explained by an increased N requirement by other organs, particularly the leaf sheath under eCO2 (Figure 5C), which was not observed in guinea grass having an inherently greater N distribution in leaf sheath (Figure 5D). To explain these findings, it was assumed that the role of the leaf sheath to store and temporally accumulate carbohydrates would be more important for wheat under eCO2, and thus, the export of carbohydrates accumulated in leaf blade would be accelerated to alleviate the downregulation of photosynthesis (Stitt, 1991; Ainsworth and Bush, 2011).

We showed that inhibited nitrate assimilation, which was weakly observed only in rice, cannot explain the growth limitation by N induced under eCO2 in any species, including rice. Furthermore, we found that nitrate acquisition is not necessarily reduced, despite a decrease in transpiration under eCO2, because of an increase in nitrate acquisition per unit water transpired. Consequently, it is likely difficult to alleviate the N-limitation by feeding with urea instead of nitrate. Our results for all species did not contradict the dilution-effect hypothesis, suggesting that a higher N supply is essential to overcome the N-limitation. Thus, we assessed the minimum nitrate-N supply for the maximum growth of wheat and found that eCO2 resulted in a 2.2-fold increase in wheat biomass with a 1.3-fold N supply compared to aCO2. Surprisingly, this greater biomass was achieved with lower water consumption. We, therefore, concluded that eCO2 strengthens the N-limitation with an accelerated plant growth rate but may enable an increase in biomass with a lower water consumption by meeting the N demand, regardless of the fed-form.

It should be noted that our results were obtained under steady day-light (400 μmol m−2 s−1), which is not sufficiently high to saturate photosynthesis, especially under the eCO2 treatment and for the C4 species examined in this study. Considering that plant responses to eCO2 depend on irradiance levels (Wheeler et al., 1991; Ghannoum et al., 1997; Paterson et al., 1999), it would be worthwhile to test whether our conclusions are valid under different light intensities.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

KY designed research. MI performed research with contributions from YY. MI, YY, and KY analyzed data. MI and KY wrote the paper. YY revised it. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This study was supported by Grant for Environmental Research Projects from The Sumitomo Foundation, and in part by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 21H02328.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

We thank Yasuko Kato for the technical assistance and the members of the Laboratory of Crop Science for valuable discussion. We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the reviewers who took their valuable time to review the manuscript and our greatest respect to the editor for her fair treatment of the manuscript.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2021.726186/full#supplementary-material

Ainsworth, E. A., and Bush, D. R. (2011). Carbohydrate export from the leaf: a highly regulated process and target to enhance photosynthesis and productivity. Plant Physiol. 155, 64–69. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.167684

Ainsworth, E. A., and Long, S. P. (2005). What have we learned from 15 years of free-air CO2 enrichment (FACE)? A meta-analytic review of the responses of photosynthesis, canopy properties and plant production to rising CO2. New Phytol. 165, 351–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01224.x

Andrews, M. (1986). The partitioning of nitrate assimilation between root and shoot of higher plants. Plant Cell Environ. 9, 511–519. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.1986.tb01582.x

Andrews, M., Condron, L. M., Kemp, P. D., Topping, J. F., Lindsey, K., Hodge, S., et al. (2019). Elevated CO2 effects on nitrogen assimilation and growth of C3 vascular plants are similar regardless of N-form assimilated. J. Exp. Bot. 70, 683–690. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ery371

Andrews, M., Condron, L. M., Kemp, P. D., Topping, J. F., Lindsey, K., Hodge, S., et al. (2020). Will rising atmospheric CO2 concentration inhibit nitrate assimilation in shoots but enhance it in roots of C3 plants? Physiol. Plant. 170, 40–45. doi: 10.1111/ppl.13096

Barrow, N. J. (2021). Presenting data and distinguishing response curves. Plant Soil 462, 1–5. doi: 10.1007/s11104-021-04887-z

Bloom, A. J., Burger, M., Rubio-Asensio, J. S., and Cousins, A. B. (2010). Carbon dioxide enrichment inhibits nitrate assimilation in wheat and Arabidopsis. Science 328, 899–903. doi: 10.1126/science.1186440

Bloom, A. J., Kasemsap, P., and Rubio-Asensio, J. S. (2020). Rising atmospheric CO2 concentration inhibits nitrate assimilation in shoots but enhances it in roots of C3 plants. Physiol. Plant. 168, 963–972. doi: 10.1111/ppl.13040

Bloom, A. J., Rubio-Asensio, J. S., Randall, L., Rachmilevitch, S., Cousins, A. B., and Carlisle, E. A. (2012). CO2 enrichment inhibits shoot nitrate assimilation in C3 but not C4 plants and slows growth under nitrate in C3 plants. Ecology 93, 355–367. doi: 10.1890/11-0485.1

Burnett, A. C., Rogers, A., Rees, M., and Osborne, C. P. (2016). Carbon source-sink limitations differ between two species with contrasting growth strategies. Plant Cell Environ. 39, 2460–2472. doi: 10.1111/pce.12801

Burnett, A. C., Rogers, A., Rees, M., and Osborne, C. P. (2018). Nutrient sink limitation constrains growth in two barley species with contrasting growth strategies. Plant Direct 2:e00094. doi: 10.1002/pld3.94

Cataldo, D. A., Maroon, M., Schrader, L. E., and Youngs, V. L. (1975). Rapid colorimetric determination of nitrate in plant tissue by nitration of salicylic acid. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 6, 71–80. doi: 10.1080/00103627509366547

Conroy, J. P. (1992). Influence of elevated atmospheric CO2 concentrations on plant nutrition. Aust. J. Bot. 40, 445–456. doi: 10.1071/BT9920445

Cotrufo, M. F., Ineson, P., and Scott, A. (1998). Elevated CO2 reduces the nitrogen concentration of plant tissues. Glob. Chang. Biol. 4, 43–54. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2486.1998.00101.x

Coupel-Ledru, A., Lebson, E., Christophe, A., Gallo, A., Gago, P., Pantin, F., et al. (2016). Reduced nighttime transpiration is a relevant breeding target for high water-use efficiency in grapevine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 8963–8968. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1600826113

Cousins, A. B., and Bloom, A. J. (2003). Influence of elevated CO2 and nitrogen nutrition on photosynthesis and nitrate photo-assimilation in maize (Zea mays L.). Plant Cell Environ 26, 1525–1530. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3040.2003.01075.x

Davey, P. A., Parson, A. J., Atkinson, L., Wadge, K., and Long, S. P. (1999). Does photosynthetic acclimation to elevated CO2 increase photosynthetic nitrogen-use efficiency? a study of three native UK grassland species in open-top chambers. Funct Ecol. 13, 21–28. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2435.1999.00004.x

Epstein, E., and Bloom, A. J. (2005). Mineral Nutrition of Plants: Principles and Practice (Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates Inc.), 43–45.

Feng, Z. Z., Rutting, T., Pleijel, H., Wallin, G., Reich, P. B., Kammann, C. I., et al. (2015). Constraints to nitrogen acquisition of terrestrial plants under elevated CO2. Global Change Biol. 21, 3152–3168. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12938

Ghannoum, O., von Caemmerer, S., Barlow, E. W. R., and Conroy, J. P. (1997). The effects of CO2 enrichment and irradiance on the growth, morphology and gas exchange of a C3 (Panicum laxum) and C4 (Panicum antidotale) grass. Aust. J. Plant Phisiol. 24, 227–237.

Gifford, R. M., Barrett, D. J., and Lutze, J. L. (2000). The effects of elevated CO2 on the C: N and C: P mass ratios of plant tissues. Plant Soil 224, 1–14. doi: 10.1023/A:1004790612630

Houshmandfar, A., Fitzgerald, G. J., O'Leary, G., Tausz-Posch, S., Fletcher, A., and Tausz, M. (2018). The relationship between transpiration and nutrient uptake in wheat changes under elevated atmospheric CO2. Physiol. Plant. 163, 516–529. doi: 10.1111/ppl.12676

Hunt, R., Causton, D. R., Shipley, B., and Askew, A. P. (2002). A modern tool for classical plant growth analysis. Ann. Bot. 90, 485–488. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcf214

Imai, K., and Murata, Y. (1979). Effect of carbon dioxide concentration on growth and dry matter production of crop plants. VII. Influence of light intensity and temperature on the effect of carbon dioxide-enrichment in some C3- and C4-species. Japanese J. Crop. Sci. 48, 409–417. doi: 10.1626/jcs.48.409

Imai, K., and Okamoto-Sato, M. (1991). Effects of temperature on CO2 dependence of gas exchange in C3 and C4 crop plants. Japanese J. Crop. Sci. 60, 139–145. doi: 10.1626/jcs.60.139

Jones, H. (2004). “What is water use efficiency?” in Water Use Efficiency in Plant Biology, ed M. A. Bacon. (Blackwell: Oxford), 27–41.

Kimball, B. A., Mauney, J. R., Nakayama, F. S., and Idso, S. B. (1993). Effects of increasing atmospheric CO2 on vegetation. Vegetation 104, 65–75. doi: 10.1007/BF00048145

Lambers, H., Chapin, I. I. I. F. S., and Pons, T. L. (2008). Plant Physiological Ecology. New York, NY: Springer.

Lemonnier, P., and Ainsworth, E. A. (2018). “Crop responses to rising atmospheric [CO2] and global climate change,” in Food Security and Climate Change, eds. S. S. Yadav, et al. (Chichester: John Wiley and Sons, Ltd), 51–69.

Long, S. P., Ainsworth, E. A., Rogers, A., and Ort, D. R. (2004). Rising atmospheric carbon dioxide: plants face the future. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 55, 591–628. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141610

McGrath, J. M., and Lobell, D. B. (2013). Reduction of transpiration and altered nutrient allocation contribute to nutrient decline of crops grown in elevated CO2 concentrations. Plant Cell Environ. 36, 697–705. doi: 10.1111/pce.12007

McMurtrie, R. E., Norby, R. J., Medlyn, B. E., Dewar, R. C., Pepper, D. A., Reich, P. B., et al. (2008). Why is plant-growth response to elevated CO2 amplified when water is limiting, but reduced when nitrogen is limiting? a growth-optimisation hypothesis. Funct. Plant Biol. 35, 521–534. doi: 10.1071/FP08128

Paterson, E., Hodge, A., Thornton, B., Millard, P., and Killham, K. (1999). Carbon partitioning and rhizosphere C-flow in Lolium perenne as affected by CO2 concentration, irradiance and below-ground conditions. Global Change Biol. 5, 669–678.

Poorter, H., and Navas, M.-L. (2003). Plant growth and competition at elevated CO2: on winners, losers and functional groups. New Phytol. 157, 175–198. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2003.00680.x

Poorter, H., VanBerkel, Y., Baxter, R., DenHertog, J., Dijkstra, P., Gifford, R. M., et al. (1997). The effect of elevated CO2 on the chemical composition and construction costs of leaves of 27 C3 species. Plant Cell Environ. 20, 472–482. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3040.1997.d01-84.x

Rachmilevitch, S., Cousins, A. B., and Bloom, A. J. (2004). Nitrate assimilation in plant shoots depends on photorespiration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 11506–11510. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404388101

Rubio-Asensio, J. S., Rachmilevitch, S., and Bloom, A. J. (2015). Responses of Arabidopsis and wheat to rising CO2 depend on nitrogen source and nighttime CO2 levels. Plant Physiol. 168, 156–163. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.00110

Saeki, T. (1965). Growth analysis of plants. Bot. Mag. Tokyo 78, 111–119. doi: 10.15281/jplantres1887.78.111

Stitt, M. (1991). Rising CO2 levels and their potential significance for carbon flow in photosynthetic cells. Plant Cell Environ. 14, 741–762. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.1991.tb01440.x

Stitt, M., and Krapp, A. (1999). The interaction between elevated carbon dioxide and nitrogen nutrition, the physiological and molecular background. Plant Cell Environ. 22, 583–621. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3040.1999.00386.x

Taub, D. R., and Wang, X. Z. (2008). Why are nitrogen concentrations in plant tissues lower under elevated CO2? a critical examination of the hypotheses. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 50, 1365–1374. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2008.00754.x

Tausz-Posch, S., Tausz, M., and Bourgault, R. (2020). Elevated [CO2] effects on crops: Advances in understanding acclimation, nitrogen dynamics and interactions with drought and other organisms. Plant Biol. 22, 38–51. doi: 10.1111/plb.12994

Ward, J. K., Tissue, D. T., Thomas, R. B., and Strain, B. R. (1999). Comparative responses of model C3 and C4 plants to drought in low and elevated CO2. Global Change Biol. 5, 857–867. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2486.1999.00270.x

Wheeler, R. M., Tibbitts, T. W., and Fitzpatrick, A. H. (1991). Carbon dioxide effects on potato growth under different photoperiod and irradiance. Crop Sci. 31, 1209–1213.

Yi, Y., Sugiura, D., and Yano, K. (2019). Quantifying phosphorus and water demand to attain maximum growth of Solanum tuberosum in a CO2-enriched environment. Front. Plant Sci. 10,1417. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.01417

Yi, Y., Sugiura, D., and Yano, K. (2020). Nitrogen and water demands for maximum growth of Solanum tuberosum under doubled CO2: interaction with phosphorus based on the demands. Environ. Exp. Bot. 176:104089. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2020.104089

Keywords: ammonium, cumulative transpiration, nitrate, nitrogen nutrition, water-use efficiency

Citation: Igarashi M, Yi Y and Yano K (2021) Revisiting Why Plants Become N Deficient Under Elevated CO2: Importance to Meet N Demand Regardless of the Fed-Form. Front. Plant Sci. 12:726186. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.726186

Received: 16 June 2021; Accepted: 30 September 2021;

Published: 04 November 2021.

Edited by:

Victoria Fernandez, Polytechnic University of Madrid, SpainReviewed by:

Roslyn Gleadow, Monash University, AustraliaCopyright © 2021 Igarashi, Yi and Yano. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Katsuya Yano, a3lhbm9AYWdyLm5hZ295YS11LmFjLmpw

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.