- Department of Biology, University of Louisiana at Lafayette, Lafayette, LA, United States

Although heat and desiccation stresses often coincide, the response to heat especially in desiccation tolerant plants is rarely studied. We subjected hydrated Pleopeltis polypodioides fronds to temperatures up to 50°C and dehydrated fronds up to 65°C for 24 h. The effect of heat stress was evaluated using morphological changes, photosystem (PS) II efficiency, and metabolic indicators. Pinnae of dried fronds exposed to more than 40°C curled tighter and became brittle compared to fronds dried at lower temperatures. Exposure to > 50°C leads to discolored fronds after rehydration. Hydrated fronds turned partially brown at > 35°C. Chlorophyll fluorescence (Ft) and quantum yield (Qy) increased following re-hydration but the recovery process after 40°C treatment lasted longer than at lower temperatures. Similarly, hydrated fronds showed reduced Qy when exposed to > 40°C. Dried and hydrated fronds remained metabolically active up to 40°C. Hydroperoxides and lipid hydroperoxides in dried samples remained high up to 50°C, but decreased in hydrated fronds at > 40°C. Catalase (CAT) and glutathione (GSH) oxidizing activities remained high up to 40°C in dehydrated fronds and up to 35°C in hydrated fronds. Major fatty acids detected in both dehydrated and hydrated fronds included palmitic (C16:0) and stearic (C18:0) acids, oleic (18:1), linoleic (C18:2); and linolenic (C18:3) acids. Linolenic acid was most abundant. In dried fronds, all fatty acids decreased at > 35°C. The combined data indicate that the thermotolerance of dry fronds is about 55°C but is at least 10°C lower for hydrated fronds.

Introduction

Heat stress is one of the major abiotic stresses limiting plant growth, yield, and productivity (Wang et al., 2016). Temperatures beyond the “physiological capacity” of plants have debilitating effects on biochemical processes, cellular homeostasis (Kotak et al., 2007), changes in enzyme activities, photosynthesis (Greer, 2015), protein synthesis (Ferguson et al., 1994), and membrane fluidity (Hemantaranjan et al., 2014). Damage to photosystem (PS) II and associated proteins (Chen et al., 2018) is reported to be a primary target of high temperature stress (Wen et al., 2005; Mathur et al., 2014). Heat stress uncouples electron transport activity, ATP synthesis and variable (Fv), and maximum (Fm) chlorophyll fluorescence (Maxwell and Johnson, 2000), which results in the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as singlet oxygen, superoxides, hydrogen peroxide, and hydroxyl radicals, all of which induce oxidative stress (Hasanuzzaman et al., 2013; Awasthi et al., 2015). Furthermore, heat stress affects activity of the antioxidative enzymes superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), peroxidases (POD), ascorbate peroxidase (APX), and low molecular weight antioxidants like ascorbic acid and glutathione (GSH), which change in response to heat stress (Lu et al., 2008; Ergin et al., 2016).

Plants not only experience heat- but also desiccation stress, which stems from loss of water via evapotranspiration. Distinguishing combined stresses is difficult because many of the physiological and molecular responses between these stresses overlap (Zandalinas et al., 2018). Some studies suggest that the combination of these two stresses is more deleterious to plant growth and productivity than each individual stress (Jiang and Huang, 2001; Rizhsky et al., 2002; Lipiec et al., 2013; Zandalinas et al., 2018) and the response to combined stresses cannot be extrapolated from the individual stress (Zandalinas et al., 2018). Therefore, studies typically report the combined effects of heat and drought stress (Rizhsky et al., 2002; Bhardwaj et al., 2015; Zandalinas et al., 2018). However, this approach obscures the individual stress response. Additionally, separating heat from desiccation stress is not possible in the field and difficult to establish even under laboratory conditions but leads to meaningful characterization of the metabolic response to individual stressors.

Plants that are especially well-suited to study desiccation stress are “resurrection” plants. These plants are defined by their vegetative tissues being able to sustain desiccation to water potentials as low as −100 MPa (Gaff, 1997). They can reach complete air dryness and rehydrate without suffering noticeable injury. Because these plants can sustain desiccation and attain certain levels of quiescence during this process, their heat tolerance can be tested in dry and hydrated conditions. A large body of research has reported thermotolerance capacity of non-vascular, poikilohydric species such as bryophytes (Lange, 1955; Nörr, 1974; Meyer and Santarius, 1998) and lichens (Lange, 1953; Tegler and Kershaw, 1981). Although thermo and frost resistance of desiccation tolerant pteridophytes (Kappen, 1964) and heat resistance of desiccation tolerant pteridophytes (Eickmeier, 1986) and angiosperms (Hambler, 1961; Kappen, 1966; Vieweg and Ziegler, 1969) was examined, there is no information on biochemical responses of these plants to elevated temperatures. Based on morphological and photosynthetic responses, there is general consensus that non-vascular and vascular plants show increased thermotolerance after desiccation (Macfarlane and Kershaw, 1978; Tegler and Kershaw, 1981; Eickmeier, 1986). However, the dependency on seasonal conditions also indicates that desiccation alone is insufficient to establish thermotolerance. To dissect the biochemical responses to heat and desiccation, we studied the response of the desiccation tolerant fern Pleopletis polypodioides in dry and hydrated fronds. Because pteridophytes are widely distributed and successfully established in various environments, they not only provide essential information on the evolution of desiccation tolerance but also serve an excellent model to study the effects of heat stress.

Pleopeltis polypodioides (aka resurrection fern) can tolerate loss of 95% of cellular water content and regain full metabolic activities within a few hours of rehydration (Pessin, 1924; Stuart, 1968; John and Hasenstein, 2017). In response to dehydration, the ventral surface curls inward and the dorsal surface, covered with peltate scales, remains exposed (Pessin, 1924). Such folding mechanisms, also demonstrated by other resurrection plants, are thought to be a defensive mechanism against photooxidation (Farrant et al., 1999; Helseth and Fischer, 2005). Although there is plenty of information on morphological changes of plants in response to heat and desiccation stress, adaptations of ferns to desiccation (Pessin, 1924; Stuart, 1968; Helseth and Fischer, 2005; John and Hasenstein, 2017), and biochemical response to drought (Maslenkova and Homann, 2000; Georgieva and Maslenkova, 2001; Layton et al., 2010; John and Hasenstein, 2018) are limited. In addition, the response of Pleopeltis to heat has not been investigated.

We evaluate the biochemical responses of dry and hydrated fronds of Pleopeltis to heat by assessing their photosynthetic and metabolic activities, levels of stress molecules, activities of antioxidative enzymes, membrane stability, and the fatty acid profile. Our results indicate that independent of hydration, oxidative and antioxidative systems are sensitive to heat but dried fronds tolerate heat better than hydrated fronds.

Materials and Methods

Plant Materials

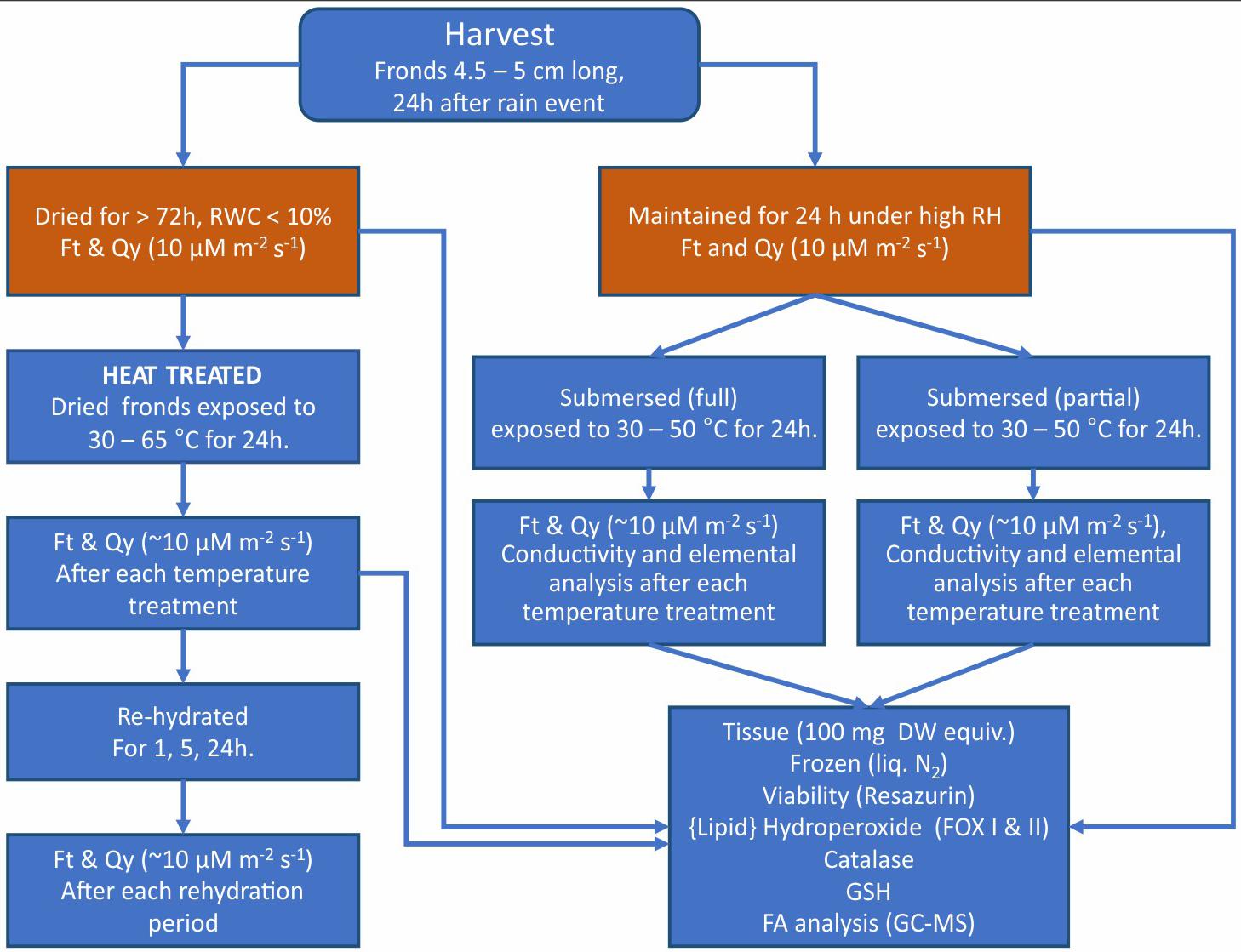

Because Pleopeltis fronds are highly responsive to environmental conditions and are efficient in water uptake compared to plants with intact rhizomes (John and Hasenstein, 2017), we focused on studying the thermal tolerance of isolated fronds. Hydrated fronds P. polypodioides were collected from live oak (Quercus virginiana) trees on the campus of the University of Louisiana at Lafayette (30.21 N, −92.02 W). All fronds were collected after a rain event during March to May from 2016 to 2019 and prior to experimentation maintained in a humid chamber at high RH. All fronds were between 4.5 and 5 cm long. The outline of the workflow is illustrated in Figure 1 and individual methodologies explained below.

Figure 1. Summary of the workflow of experiments and analyses performed on dried, rehydrated, and submersed Pleopeltis fronds. Data obtained from the initial sample status (red boxes) served a reference for all other treatments.

Heat Treatment

Heat treatment was applied for 24 h in darkness. Assays of heat treated dry and hydrated (fully and partly submersed) samples were compared with 25°C dry and fresh control, respectively.

Dehydrated Fronds

Detached, fresh fronds were dried at 25°C for 72 h, which reduces the RWC to < 5% (John and Hasenstein, 2018). After drying, the fronds were exposed to temperatures between 30 and 50°C for 24 h in an incubator. Relative humidity decreased as a function of temperature increase.

Hydrated Fronds

Detached fresh fronds were placed in DI water in 20 mL glass vials such that either the entire frond (vial filled with 20 mL water) or just the apical end (4 mL water) was submersed and exposed to the same temperature as dried fronds. The reason for different levels of submersion was to test the effect of oxygen deprivation in fronds that were fully submersed compared to 100% humidity. The data were compared with hydrated fronds (without immersion) at 25°C.

Photosynthetic Performance

The photosynthetic performance of the fronds before and after heat stress and after re-hydration was assessed by measuring the minimum chlorophyll fluorescence (F0, which is equivalent to Ft if the leaf sample is dark-adapted) and quantum yield (Qy) using a FluorPen FP100 (Photo Systems Instruments, Czechia). F0 was measured by applying a light pulse (455 nm of 0.09 μmoles m–2s–1 for 30 μs) and recorded as Ft. Similarly, Qy measurements were obtained by applying a saturating light that measures maximum value of fluorescence (Fm) from PS II (approximately 3000 μmol m–2 s–1 for 0.8 s) to dark-adapted dry fronds and dim-light (∼10 μM m–2 s–1) exposed fronds. Preliminary measurements showed no difference between dark or dim-light adapted measurements. The difference between minimal fluorescence F0 and maximal fluorescence Fm divided by Fm, i.e., (Fm-F0)/Fm. We used this ratio to describe quantum yield (Qy) of PS II system. Normal photosynthetic activity shows maximum Qy of about 0.83 (Maxwell and Johnson, 2000; Murchie and Lawson, 2013). We considered reduced values indicative of stress.

The Ft and Qy data were collected from fresh, dried and 24 h heat treated fronds as well as after re-hydration for 1, 5, and 24 h at room temperature (25°C). Because obtaining reliable fluorescence measurements from curled (dried) fronds was difficult, the Ft and Qy measurements were obtained from flattened fronds that were dried between paper towels and glass plates for 5 days at room temperature. Dried and submersed fronds were examined after temperature treatments. Fronds were rehydrated on water-saturated foam under dim light, and were measured after 1, 5, and 24 h. Qy and Ft were identical in dark and dim-light-maintained fronds, we therefore report data of fronds measured under dim light (10 μM m–2 s–1). The Ft and Qy measurements were obtained from the base, center, and the tip of each of six fronds and shown as average of these positions.

Membrane Permeability

Cell membrane permeability was deduced from the conductivity (μS cm–1) of the water in which the fronds were submersed. Conductivity was measured with a MW 301 EC meter (Milwaukee Instruments, Inc.) in 4 mL samples for partially and 20 mL samples in fully submersed fronds and reported as μS normalized to 10 mL. After heat treatments, fronds were kept at room temperature for an additional 24 h to assess re-uptake of ions. Elemental analysis was performed by Inductively Coupled Plasma – Optical Emission Spectrometry (Perkin Elmer, Optima 5300 DV) in 15% HNO3.

Metabolic Activity

In their natural environment, Pleopeltis fronds are exposed to sometimes extreme fluctuations of temperatures, humidity, and light intensities. Our intention is to understand how Pleopeltis responds to heat stress. Because measuring enzyme activities of dried fronds inevitably requires hydration, metabolic activities of dried fronds may not represent the actual activity in the dried state but indicate available metabolites and metabolic capacity at the endpoint of dehydration. Despite these limitations, the following tests were performed with dehydrated and hydrated fronds.

Tissue Viability

The reduction of resazurin as described in John and Hasenstein (2017) served as proxy for the assessment of vitality. Pinnae [100 mg dry weight equivalents, calculated as FW/(1-RWC) as documented in John and Hasenstein (2018)] were macerated in 2 mL of 10 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) and 0.2 mL of 4 mM resazurin (Sigma R7017), and incubated under continuous illumination (∼300 μM m–2 s–1) at 25°C for 3 h before the fluorescence of the supernatant was determined (Varian Cary, λex = 560 nm; λem = 590 nm).

Hydroperoxide Determination

Hydroperoxide (and other water-soluble peroxide) content was measured using the ferrous ammonium sulfate/xylenol orange, FOX I assay (Wolff, 1994; Cheeseman, 2006) at 560 nm (John and Hasenstein, 2018). Hydroperoxide quantification in μM was based on a standard curve and calculated as (OD560 – 0.004)/0.0763.

Measurement of Lipid Peroxide

The FOX II assay was used to quantify lipid peroxides, LOOHs (Jiang et al., 1992; Gay and Gebicki, 2003) according to John and Hasenstein (2018) such that (OD560 − 0.1305)/0.0383, determines the BHT equivalent in nM.

Catalase Activity

Catalase activity was determined from the decrease of OD240 of H2O2 for 180 s (John and Hasenstein, 2018). Based on 100 mg samples, enzyme activity was expressed as μM × min–1 × mg protein–1.

Consumption of Reduced Glutathione

The consumption of GSH was measured as described earlier (John and Hasenstein, 2018). The assay was modified after (Starlin and Gopalakrishnan, 2013). Samples (100 mg DW equivalent) were extracted in chilled sodium phosphate buffer (40 mM, pH 7, 2 mL) and centrifuged (23,000 g, 12 min, 4°C). 500 μL supernatant was transferred into a fresh centrifuge tube, mixed with 400 μL 40 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.0, 100 μL 10 mM sodium azide (Sigma, S-2002), 200 μL DI water, and vortexed. After adding 200 μL (4 mM) GSH (Cayman chemical company, 10007461) and 100 μL 2.5 mM H2O2, the solution was mixed and incubated for 1 min. The reaction was terminated by adding 500 μL of 10% trichloroacetic acid (Aldrich Chemical Company, 76-03-9). The solution was incubated at RT for 30 min and centrifuged (23,000 g, 5 min, 4°C). The supernatant (500 μL) was mixed with 1.5 mL 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) and 1 mL 5, 5’-dithiobis-2-nitrobenzoic acid (Sigma, D8130). After inversion, OD 409 was determined. Enzyme activity is reported as μM GSH consumed min–1 × mg protein–1.

Protein Determination

Protein content for the enzyme assays was determined according to Bradford (1976) using ovalbumin (Sigma, A-5378) as standard.

Fatty Acid Analysis

Fatty acids were extracted from tissue equivalent to 100 mg fresh weight, derivatized to their methyl esters, and quantified (John and Hasenstein, 2018) using an Agilent (Wilmington, DE, United States) gas chromatograph (6890) with mass selective detector (5973). One μL samples were injected and separated on a Phenomenex Zebron ZB-5MS column with hydrogen as carrier gas at a flow rate of 1.8 mL min–1. The temperature profile started at 100°C for 2 min, ramped (10°C × min–1) to 280°C and held for another 8 min. Identification of compounds was based on the National Institute of Science and Technology library 2008 in Chemstation software (E.02.02.1431). The quantity of individual fatty acids was determined based on retention time and slope of derivatized palmitic acid (Sigma, P-5917; Rt = 11.7 min; 3.98 × 106 TIC ng–1), linoleic acid (Sigma, L1376; Rt = 13.3 min, 3.53 × 106 TIC ng–1), linolenic acid (Cayman Chemical Company, 90210; Rt = 13.37 min; 2.51 × 106 TIC ng–1), oleic acid (Sigma, O1630; Rt = 13.4 min; 1.88 × 106 TIC ng–1), and stearic acid (Sigma, S-4751; Rt = 13.6 min; 3.05 × 106 TIC ng–1). Tissue samples were analyzed under identical conditions as standards.

Statistical Analysis

The data are reported as means of three to six biological replicates obtained from individual fronds. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey-Kramer post hoc test was performed using Excel data analysis tool pack (Microsoft Corporation, 2016).

Results

Morphological Response

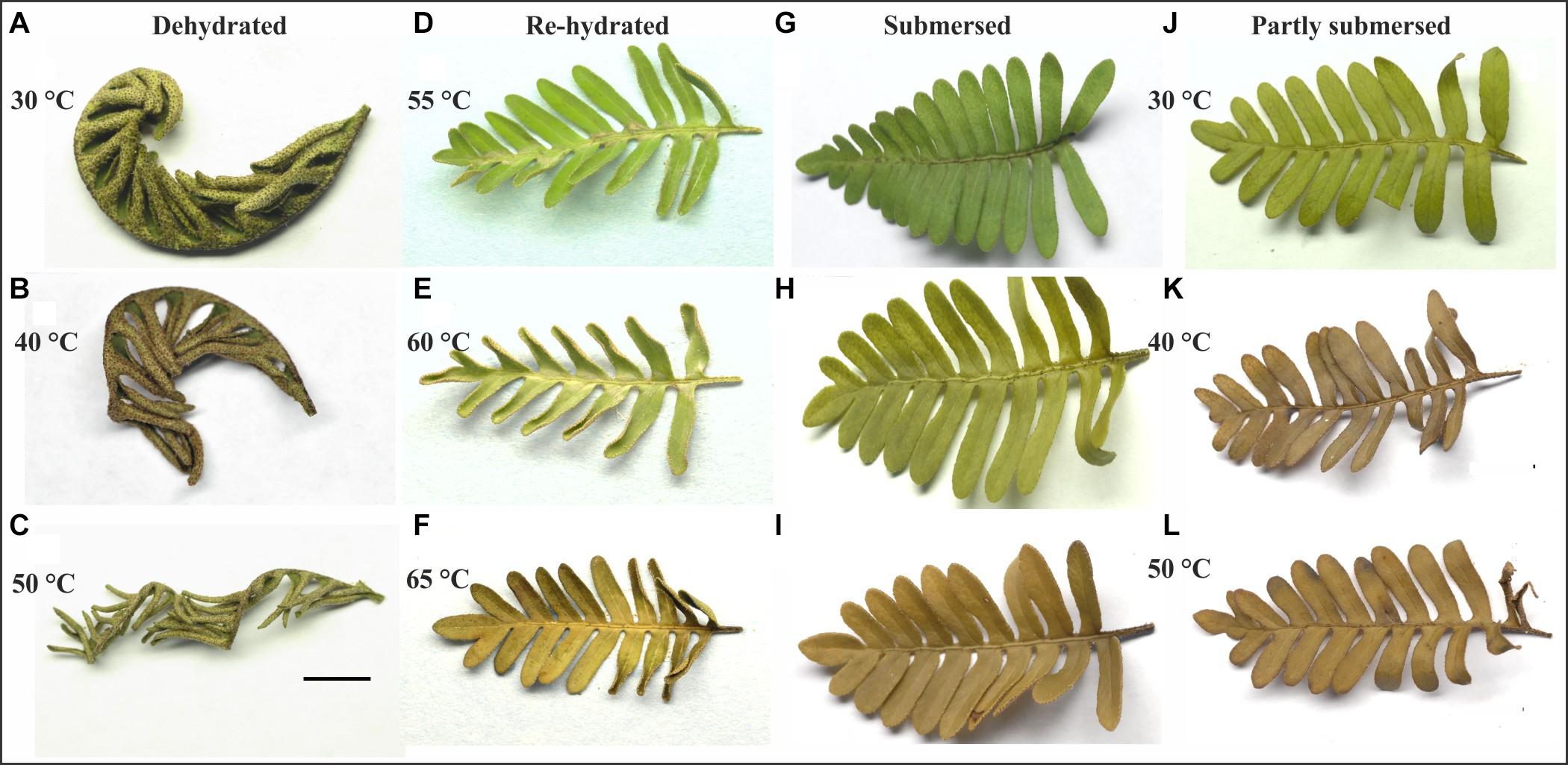

Pinnae of dried Pleopeltis fronds curled tighter with increasing temperature treatment (Figures 2A–C). Dried tissue showed no effects, but discolorations became visible after rehydration. Exposure to 55°C resulted in patchy browning along the mid-rib (rachis) of the frond (Figure 2D); after 60°C fronds were slightly (Figure 2E) and after 65°C completely discolored (Figure 2F). Submersed (Figure 2G) and partly submersed (Figure 2J) fronds showed no effects at 30°C but after exposure > 40°C submersed (Figures 2H,I) and partly submersed (Figures 2K,L) fronds showed browning.

Figure 2. Response of dehydrated (A,B,C), submersed (G,H,I), and partly submersed (J,K,L) fronds to 24 h heating at 30, 40, and 50°C, and fronds re-hydrated after exposure to 55, 60, and 65°C (D,E,F). Exposure to ≥ 40°C resulted in tight curling of dehydrated fronds and browning of the hydrated fronds. Re-hydrated fronds show discoloration near the rachis between 55 and 60°C and complete discoloration of the frond after 65°C. Scale bar = 1 cm.

Photosynthetic Performance

Dried Frond

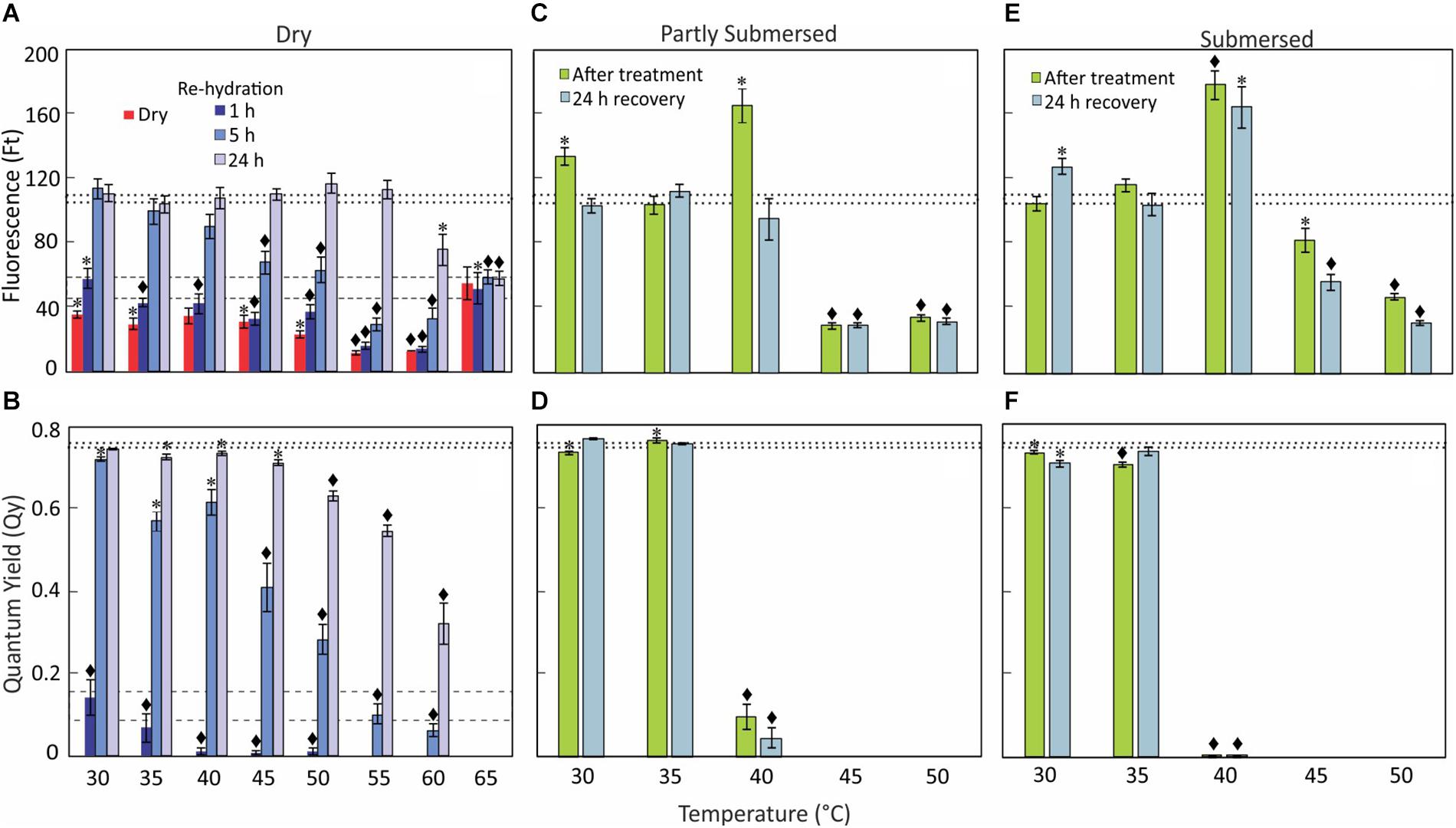

Instantaneous fluorescence (Ft) of treated dried fronds measured lower than (control) dry fronds at 25°C (Figure 3A) while Qy of fronds exposed to 30°C and higher was not detectable (Figure 3B). Interestingly, Ft of 65°C treated samples was higher than 60°C and not different from control (Figure 3A), whereas Qy even after rehydration remained undetectable (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. Chlorophyll fluorescence, Ft (A,C,E) and Qy (B,D,F) data of dry, re-hydrated, partially, and fully submersed Pleopeltis fronds after 24 h exposure to different temperatures. Control values ± SE @ 25°C for Ft and Qy of dry fronds are indicated by dashed lines (A,B) and for rehydrated fronds by dotted lines (A–F). The Ft and Qy of heat-treated, dry samples are compared with 25°C dry samples (A,B); dried fronds did not show measurable Qy values regardless of temperature. Re-hydrated and hydrated samples are compared with 25°C fresh samples (C–F). Significant differences between controls and treatments are indicated by * (P ≤ 0.05) and ◆ (P ≤ 0.001); means ± SE, n = 6.

Re-hydrated Fronds

After rehydration, the chlorophyll fluorescence (Ft) increased over time and reached control levels within 5 h for temperatures up to 35°C (Figure 3A). However, exposure to higher temperatures (≤55°C) required a recovery period of 24 h. Despite the high Ft values, the Qy decreased with higher temperatures (Figure 3B). Ft of 1-h re-hydrated fronds was low compared to (fresh) control but measurable at all temperature ranges, i.e., 30–65°C (Figure 3A). However, the Qy value decreased from 30 to 50°C and was not detectable at > 50°C (Figure 3B). Similarly, Ft of fronds re-hydrated for 5 h after less than 40°C showed values similar to (fresh) controls (Figure 3A) but Ft was lower in rehydrated fronds exposed to ≥ 45° [F(5,30) = 18, P < 0.0001]. The Qy of 5 h re-hydrated fronds was lower than in controls [F(8,45) = 37.5, P < 0.0001] but greater than after 1 h re-hydration [F(1,94) = 55.8, P < 0.0001] (Figure 3B). Beyond 45°C, Qy efficiency decreased steadily with increasing temperature (Figure 3B); there was no recovery after exposure to 65°C. Based on these data, Qy is a better indicator of sensing heat than Ft.

Hydrated Fronds

Despite some increase after 30 and 40°C treatments, Ft of partially submersed fronds decreased after exposure to temperatures higher than 40°C [F(2,15) = 312, P < 0.0001] (Figure 3C); in contrast Qy was already significantly reduced at 40°C [F(1,10) = 217, P < 0.0001] (Figure 3D). After recovery (at room temperature for 24 h), Ft and Qy of 30 and 35°C treated samples did not differ from controls (Figures 3C,D). However, in 40°C treated samples Qy remained significantly lower than base-line values [F(1,10) = 711.6, P < 0.0001], which suggests that hydration is beneficial for samples exposed to temperatures below 40°C. Unchanging but measurable Ft values in ≥ 45°C fronds and the lack of recovery of Qy after 40°C indicates degradation of PS II.

In fully submersed samples, chlorophyll fluorescence was higher but Qy suppression was stronger than in partly submersed fronds (Figure 3F). All heat-stressed samples showed reduced Ft values after the recovery period, indicating that chlorophyll degradation continues during this time. The Qy values of ≥ 40°C treated samples remained undetectable (Figure 3F). Overall, the samples exposed to ≥ 40°C showed a response similar to partially submersed fronds. The data clearly show that hydration renders the photosynthetic apparatus more sensitive to heat stress than dried fronds. Importantly, the similarity between partial and full hydration suggests that reduced gas exchange in submersed fronds is not the cause of the decline of Qy.

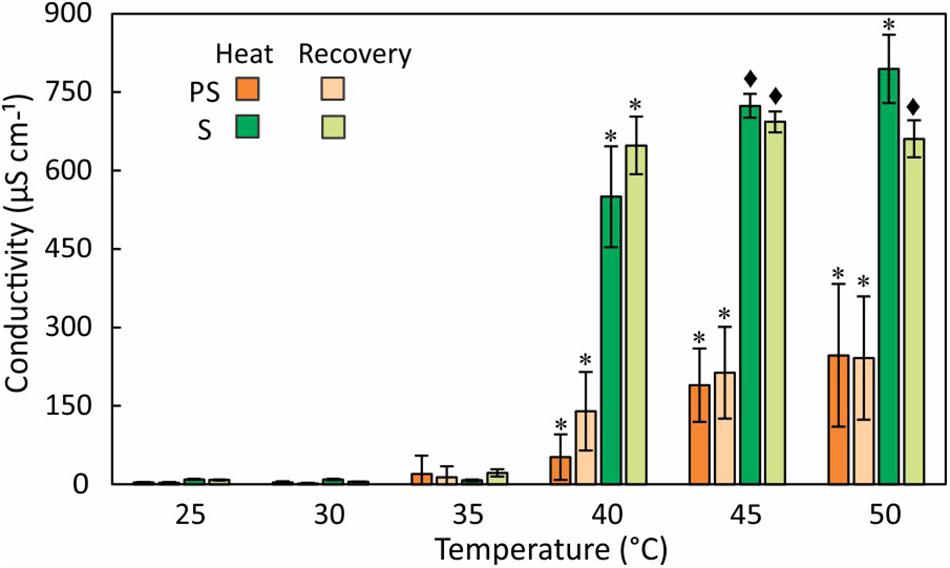

Ion Leakage

To assess the response of cell membranes to heat stress, we measured the conductivity of external water from partly and fully submersed samples treated between 30 and 50°C (Figure 4). Although the fronds were washed before the experiments to minimize surface contamination, the conductivity (normalized to 10 mL) at 30 and 35°C were not different from controls, did not differ between partly and fully submersed samples, and likely represents surface-bound ions or normal ion exchange. However, treatment of ≥ 40°C strongly increased the conductivity of fully and partly submersed fronds, indicating membrane leakiness (Figure 4). There was no reduction in conductivity after 24 h recovery at RT (Figure 4); thus, there was no re-uptake of ions during the recovery phase. The conductivities of submersed samples were higher than those of partly submersed samples (Figure 4). The ion concentration was clearly dependent on the extent of immersion, indicating that long-distance transport did not contribute to the ion release.

Figure 4. Electrolyte leakage measured as conductivity of external water after 24 h at various temperatures and after a 24 h recovery period at RT. Differences in conductivity between heat treated and 25°C control are indicated by * (P ≤ 0.05) and ◆ (P ≤ 0.001); means ± SE, n = 6.

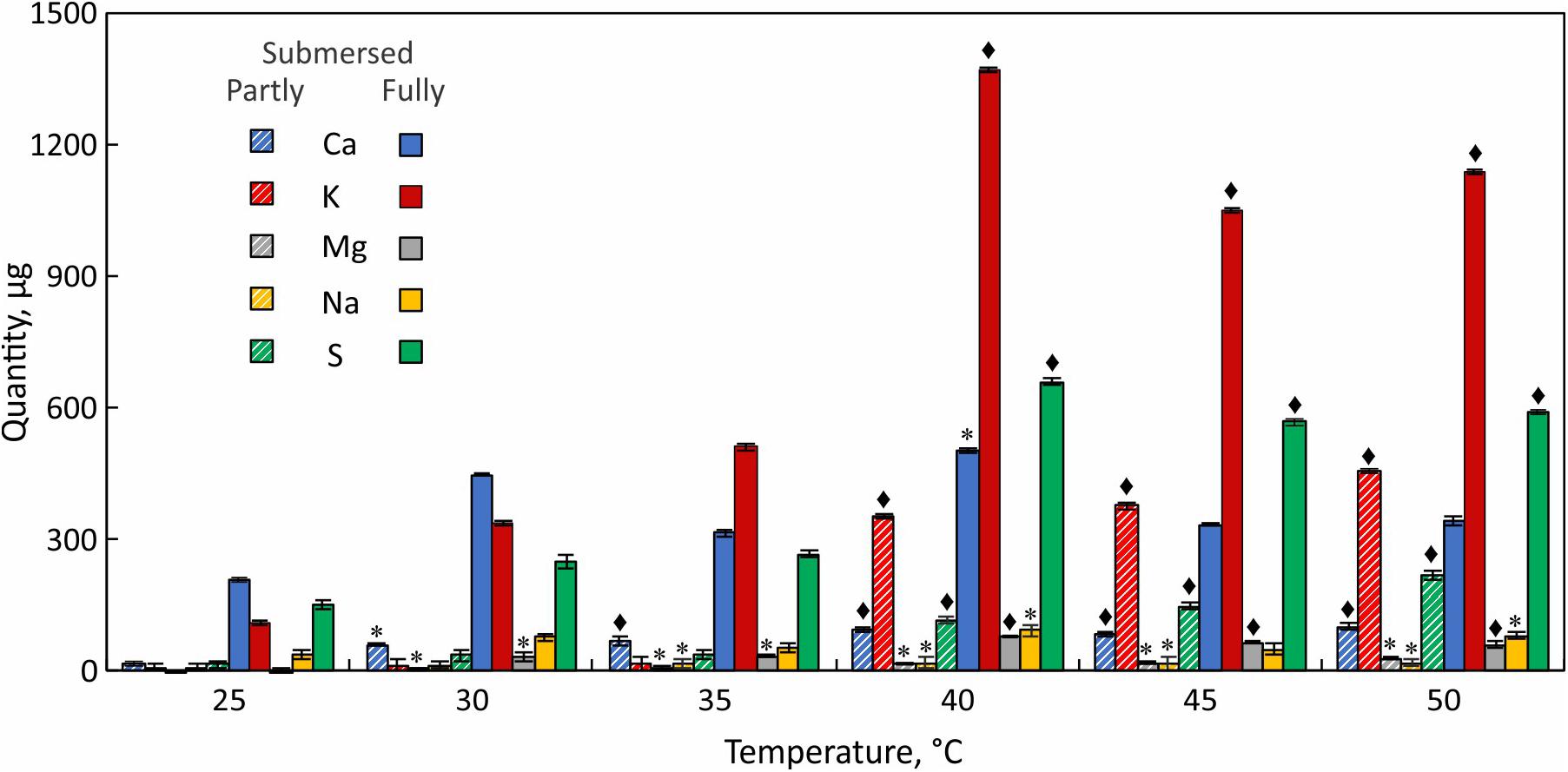

Elemental analysis of the leachate revealed that K+ is the major released ion followed by Ca+2 and S (Figure 5). Na+ and Mg2+ were present at lower quantities. K+ and S in the leachate increased with temperature and both elements showed the largest increase at 40°C (Figure 5). Ca+2 loss occurred more evenly across the tested temperature range and like Na+ did not show a distinct threshold temperature (Figure 5). Unlike partly submersed samples, the ions from submersed fronds did not increase beyond 40°C, which indicates that membrane damage occurs at that temperature.

Figure 5. Elemental analysis of leachate from partially (hatched bars) and fully submersed (solid bars) Pleopeltis fronds. Significant differences between heat treated and 25°C control are indicated by * (P ≤ 0.05) and ◆ (P ≤ 0.001); means ± SE, n = 3.

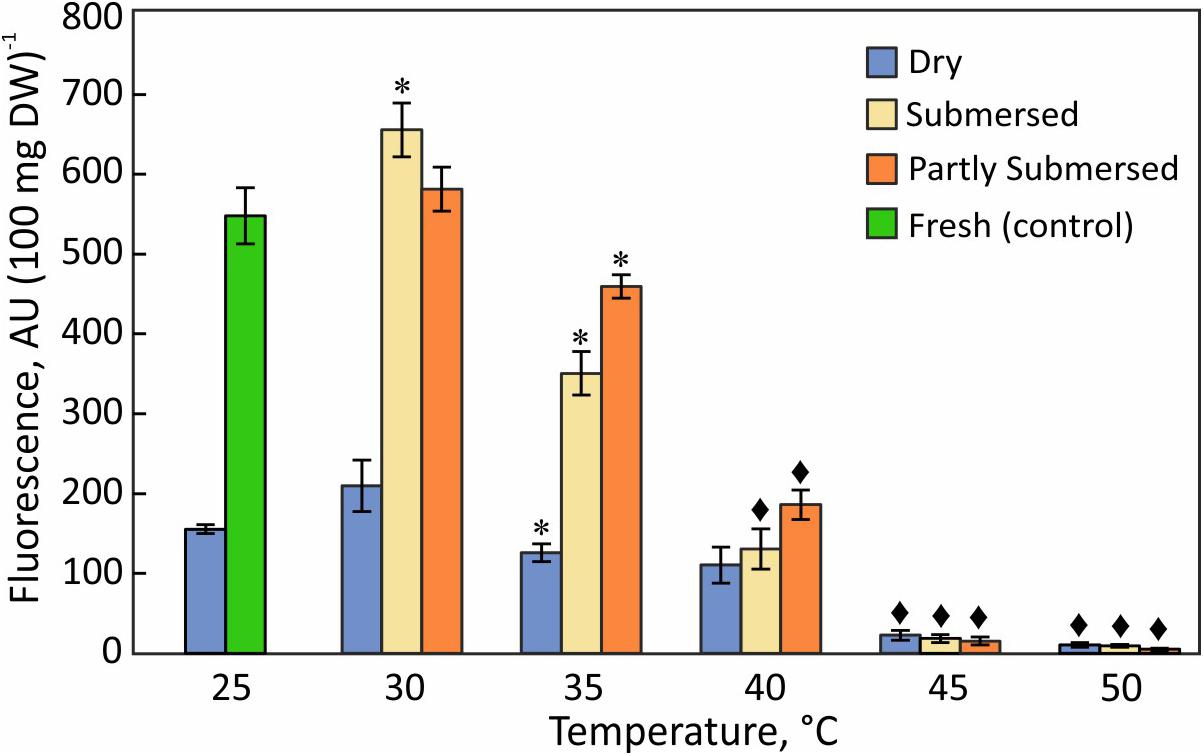

Reducing Capacity

Generic reducing capacity represents overall metabolic activity. Dried fronds showed significantly lower activity than hydrated tissue [F(4,25) = 19.6, P < 0.0001] below 45°C but their reducing capacity exceeded that of submersed tissue at higher temperatures (Figure 6) regardless of the type of submersion. Despite declining reducing capacity of dried fronds at elevated temperatures, dried fronds showed metabolic activity. Likewise, the reducing capacity remained higher in partly than in fully submersed fronds [F(1,10) = 4.9, P = 0.05] (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Reduction of resazurin in dried fronds and hydrated (fully and partly submersed) fronds exposed to heat for 24 h. The metabolic activity of heat treated dry and hydrated fronds is compared with 25°C dry and fresh (control), respectively. Significant differences between treated and controls are indicated by * (P ≤ 0.05) and ◆ (P ≤ 0.001); means ± SE, n = 6.

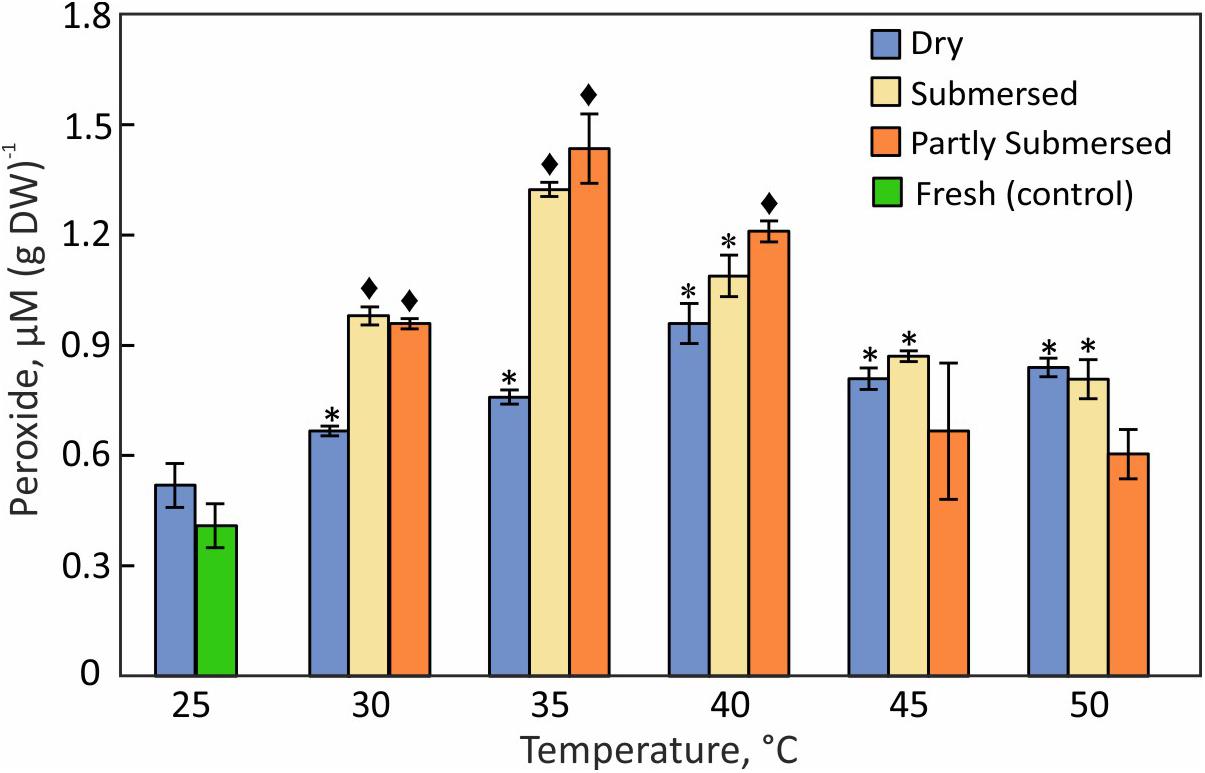

Hydroperoxides

The hydroperoxide content of dried fronds increased gradually with temperature and reached a maximum at 40°C (Figure 7). Fully and partly submersed fronds responded similarly and showed their highest values at 35°C (Figure 7). Higher temperatures led to a decrease on peroxides that was less in dried than in submersed fronds. The moderate increase in dry but stronger increase in hydrated fronds suggests that peroxide accumulates during heat stress but declines when the stress exceeds the metabolic capacity.

Figure 7. Hydroperoxide content in dried, fully, or partly submersed Pleopeltis fronds exposed to various temperatures for 24 h. The content from heat treated dry and hydrated fronds is compared with 25°C dry and fresh (control), respectively. Significant differences between treated and controls are indicated by * (P ≤ 0.05) and ◆ (P ≤ 0.001); means ± SE, n = 4.

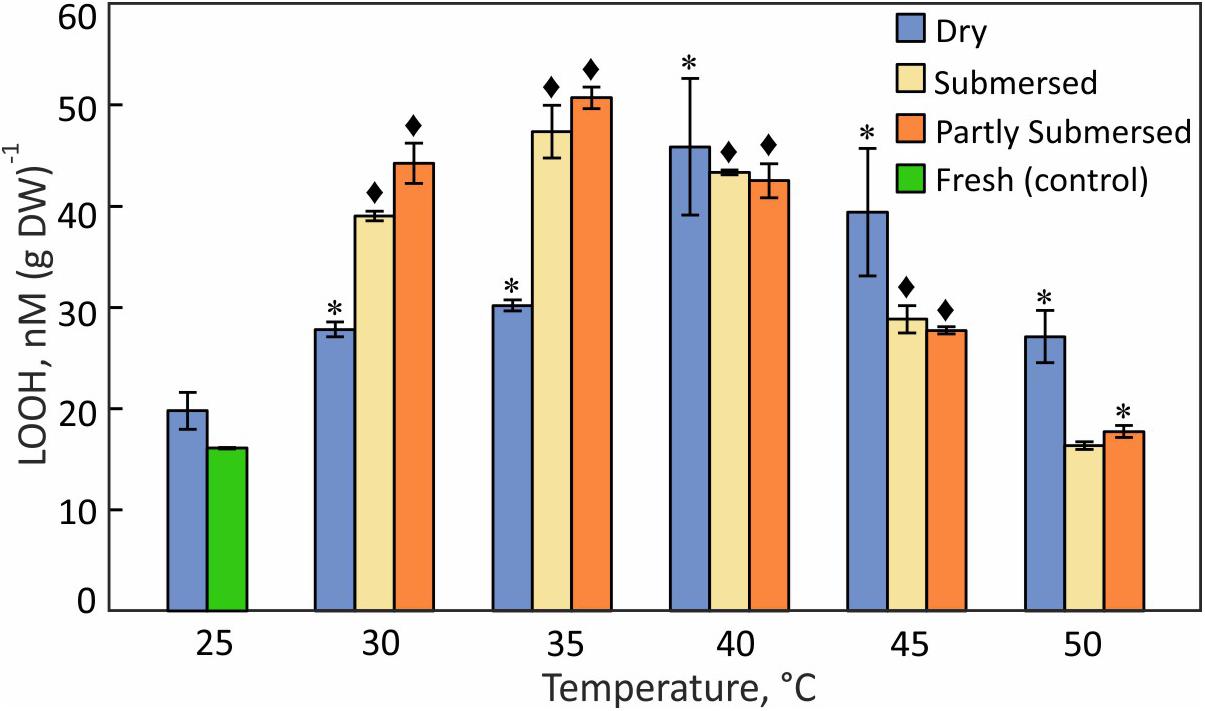

Lipid Hydroperoxides

The LOOH pattern was similar to hydroperoxides; dried fronds showed a steady increase with temperature with a maximum at 40°C [F(4,15) = 3.7, P = 0.03] (Figure 8). Partly and fully submersed samples reached their maximum at 35°C but showed lower levels of LOOH than dried fronds at 45 and 50°C (Figure 8), likely related to damaged metabolism, which weakens the response. Therefore, similar to the hydroperoxide profile, the maximum LOOH values signal the onset of non-compensated, i.e., damaging, heat stress.

Figure 8. Lipid hydroperoxide (LOOH) content in dried and fully or partly submersed Pleopeltis fronds exposed to different temperatures for 24 h. The content from heat treated dry and hydrated fronds is compared with 25°C dry and fresh (control), respectively. Significant differences between treated and controls are indicated by * (P ≤ 0.05) and ◆ (P ≤ 0.001); means ± SE, n = 4.

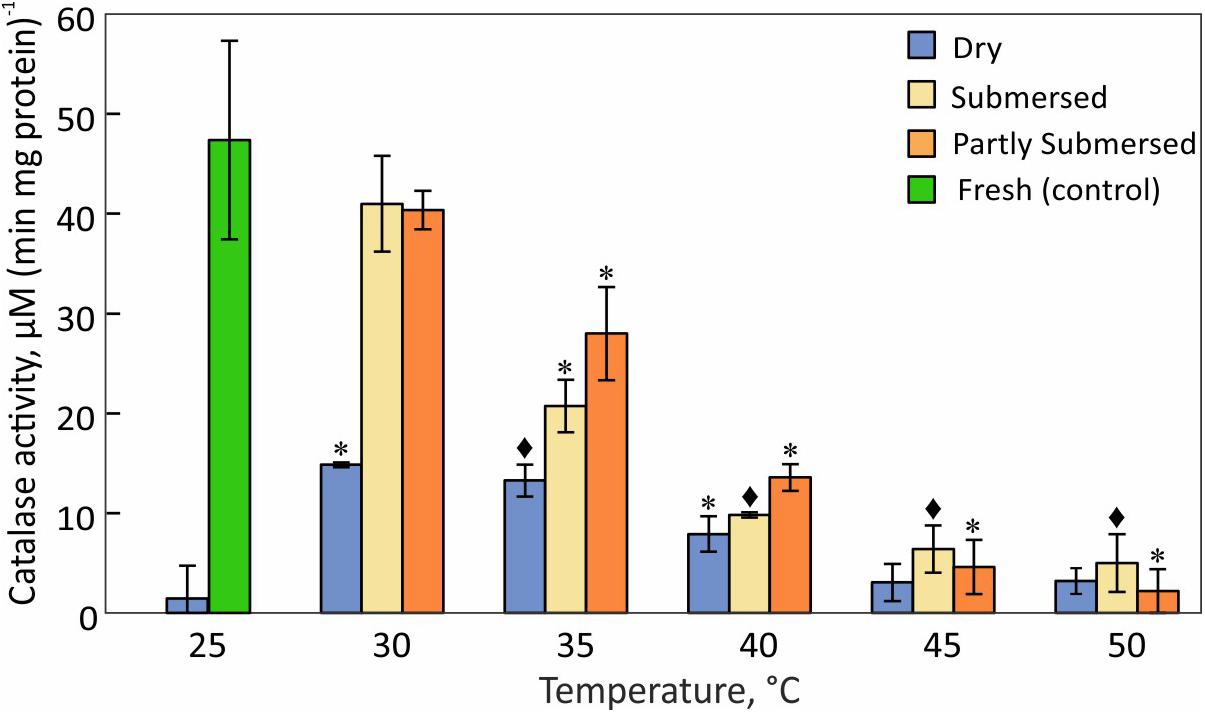

Catalase Activity

The greatest difference between dried and fresh tissue was measured at 25°C (Figure 9). Dried fronds showed their highest CAT activity at 30°C but the decline at higher temperatures was less than in hydrated fronds [F(2,57) = 3.1, P = 0.05]. Like dry fronds, submersed fronds showed a steady decline in CAT activity and the extent of submersion had no effect (Figure 9). Because CAT activity in dried fronds was significantly higher after 30°C treatment than at 25°C and significantly reduced in hydrated fronds at 35°C, CAT activity was higher in hydrated vs. dried tissue. CAT activity is remarkably temperature sensitive and the decline at 35°C indicates a stress response of CAT-linked processes.

Figure 9. Catalase activity in dried and fully or partly submersed Pleopeltis fronds exposed to different temperatures for 24 h. The activity of heat treated dry and hydrated fronds is compared with 25°C dry and fresh (control), respectively. Significant differences between treated and controls are indicated by * (P ≤ 0.05) and ◆ (P ≤ 0.001); means ± SE, n = 4.

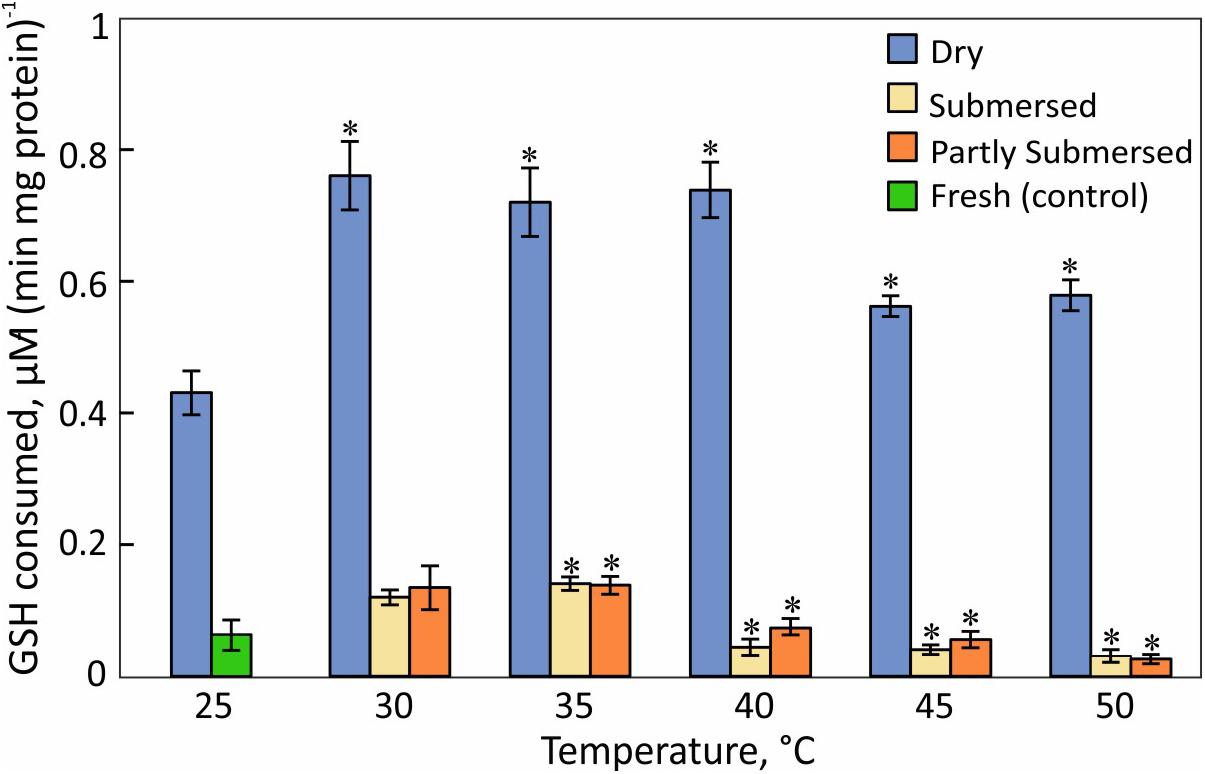

Glutathione (GSH) Consumption

Glutathione consumption responded stronger to desiccation than heat stress [F(2,57) = 363, P < 0.0001] (Figure 10). GSH consumption in dried fronds decreased at ≥ 45°C [F(1,6) = 13.3, P = 0.01] compared to 30–40°C treated samples (Figure 10). GSH consumption of hydrated fronds showed a similar reduction and the extent of submersion had no effect. GSH utilization of 30°C dried and hydrated samples did not differ from the respective 25°C controls.

Figure 10. H2O2-dependent glutathione oxidation activity in dried and partially and fully submersed Pleopeltis fronds exposed to different temperatures for 24 h. The activity of heat treated dry and hydrated fronds is compared with 25°C dry and fresh (control), respectively. Significant differences between treated and controls are indicated by ∗ (P ≤ 0.05); means ± SE, n = 4.

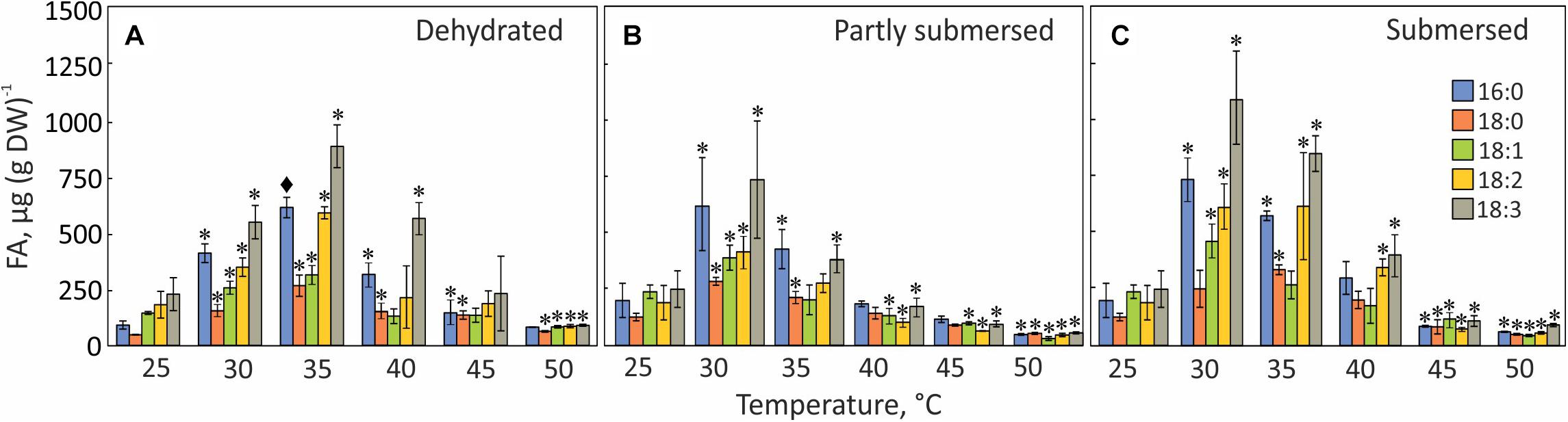

Fatty Acid (FA) Profile

Temperature stress changed the FA composition and quantity in all samples. The total FA content in dehydrated fronds increased up to 35°C but decreased at higher temperatures (Figure 11A). In partly and fully submersed fronds, the total fatty acid reached its peak at 30°C and declined at higher temperatures (Figures 11B,C); the FA content in 50°C treated dried and hydrated samples was 76% and 90% lower than 30°C treated fronds, respectively (Figure 11).

Figure 11. FA profiles in dried (A), partly submersed (B), and fully submersed (C) fronds after exposure to various temperatures for 24 h. 16:0 = palmitic acid; 18:0 = stearic acid; 18:1 = oleic acid; 18:2 = linoleic acid; 18:3 = linolenic acid. Significance levels are based on the FA content of 25°C dry and hydrated fronds, respectively. Significant differences between treated and controls are indicated by * (P ≤ 0.05) and ◆ (P ≤ 0.001); means ± SE, n = 4.

Palmitic (16:0), stearic (18:0), oleic (18:1), linoleic (18:2), and linolenic (18:3) acid were detected in controls and heat-treated fronds but linolenic acid (18:3) was the dominant FA at all temperatures and the total amount of fatty acids in fully submersed fronds was higher than in dried and partly submersed samples (Figure 11).

The extent of unsaturation correlated with peroxidation; therefore, we examined the degree of unsaturation for each temperature. The percentage of unsaturated fatty acids (18:1, 18:2, 18:3) in 30°C, dried and partly submersed samples was 12 and 5% lower than at 25°C (Figure 11). Exposure to temperatures higher than 30°C decreased unsaturation, especially in partly submersed samples (Figure 11 and Supplementary Table 1). Regardless of the hydration condition, after exposure to temperatures of 45°C and higher, all FAs showed reduced but equal quantities. In general, the relative proportion of unsaturated fatty acids was higher in dried than in hydrated fronds; and declined in dried fronds above 40°C; this reduction began in hydrated fronds at 35°C.

Discussion

Our data describe diverse responses to separate desiccation and high temperature stresses. As stated under section “Materials and Methods,” it is important to reiterate the arbitrary nature of the study. The problematic aspects include the duration of the temperature treatment and the testing of various processes and enzymatic activities. It is unlikely that in nature temperatures greater than 40°C extend for more than 12 h. Nonetheless, heat tolerance was tested previously for an equally arbitrary time of 30 min, which resulted in tolerance of > 100°C (Lange, 1955). While evaporative cooling likely provides some protection during short-term heat exposure, our heat treatments of 24 h exceeds naturally occurring conditions but provides enough time to assess metabolic responses. Similarly, submersion of fronds eliminates water stress but may cause different stress for the epiphytic Pleopletis as was shown by the lower reducing capacity (Figure 6) and reduced Qy (Figure 3F) of completely vs. partially submersed fronds (Figure 3D). This sensitivity may be the result of reduced gas exchange (Voesenek et al., 2006), or the enhanced activity of symbiotic surface organisms (Koch and Barthlott, 2009); both phenomena can lead to anoxia (Blokhina et al., 2003; Banti et al., 2010). Nonetheless, the differences between the submersion treatments illustrate the sensitivity of the fronds to different conditions and allow for nuanced evaluation of heat effects.

Stress response includes changes in morphology, cellular functions, metabolism, and ultimately gene expression. Because of the reduced metabolism under dry conditions, it is likely that dry tissue shows reduced susceptibility to heat damage. The co-variance between desiccation and heat may induce changes in cell wall and thus frond shape (Wu et al., 2018) a suitable indicator for heat stress of dry material (Figure 2). However, fronds expanded even after exposure to 65°C; therefore, heat stress cannot be assessed solely through changes in shape or color.

Changes in Frond Shape and Color

In response to increasing temperature, dehydrated Pleopeltis fronds became thinner, pinnae curled tighter (Figures 2B,C), and after exposure to ≥ 45°C fronds became brittle. Such dramatic changes are likely a response to the combination of water loss and heat that reduces matrix hydration and therefore affects shape and elasticity of cell wall polymers (Lima et al., 2013). These changes possibly indicate glass transition, which facilitates survival in ferns spores (Ballesteros et al., 2017). Among the cell wall polymers, pectin affects the elasticity of the cell wall (Willats et al., 2001) and heat sensitivity (Lima et al., 2013). Loss of pectin functionality leads to increased cell wall porosity, brittleness, and conductive evaporation (Willats et al., 2001; Bethke et al., 2016). Pectin arrangements are likely modified in response to the combination of drying and elevated temperatures, but further research is needed to assess the status of pectin in the cell wall of dried Pleopeltis fronds. Fronds exposed to 30–50°C fully expanded upon rehydration (at 25°C) and did not show necrosis, or changes in shape of the fronds (data not shown).

Discolorations of hydrated fronds after exposure to ≥ 35°C (Figures 2E–I) and re-hydrated fronds after exposure to > 55°C (Figure 2) indicate that these fronds have experienced stress beyond their thermal tolerance resulting in chloroplast or chlorophyll degradation, which eventually leads to senescence (Jespersen et al., 2016) and programmed cell death (PCD) (Qu et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2015). One of the key enzymes known to regulate the breakdown of chlorophyll is pheophytinase (Schelbert et al., 2009). It is possible that the activity of this enzyme increases at high temperatures, similar to observations in bentgrass (Jespersen et al., 2016). Stress-induced chlorophyll degradation is also affected by ethylene, abscisic acid, cytokinin, and ROS (Xu and Huang, 2007). These compounds also influence PS II-mediated electron transport (Xu and Huang, 2007; Griffiths et al., 2014), and membrane-bound ion channels (Demidchik, 2018), proteins, and lipids (Veerasamy et al., 2007; Griffiths et al., 2014). Based on browning, our morphological data indicate that 40°C is the threshold for heat damage for hydrated Pleopeltis fronds (Figures 2E–I); in contrast, dried fronds can tolerate > 60°C (Figure 2).

Photosynthetic Susceptibility

Dried Fronds

Fluorescence (Ft) and quantum yield (Qy) of dried fronds were lower than in fresh fronds but readily detectable (Figures 3A,B), indicating that drying decreases but not completely blocks photosynthetic activity. After dry fronds were exposed to > 50°C, Qy was undetectable (Figure 3B) and Ft decreased (Figure 3A) suggesting that the PS II system responds to stress and is blocked by heat (Yamada et al., 1996). This disruption likely protects the photosynthetic apparatus from oxidative damage. Interestingly, after exposure to 65°C, Ft was higher than after 60°C exposure or in non-heat-treated, dry fronds (Figure 3A), suggesting that extreme temperatures (i.e., 65°C) lead to the disintegration of the photosynthetic reaction center (Wise et al., 2004; Kadir et al., 2007) but chlorophyll fluorescence persists. Thus, based on the Ft and Qy data, the photosynthetic apparatus in dry fronds is heat-tolerant up to 60°C. The photosynthetic apparatus adjusts to stress in several ways, including elevated non-photochemical quenching (NPQ), which can lead to increases in Zeaxanthin and other pigments even under dark conditions (Brüggemann et al., 2009; Leuenberger et al., 2017) and ROS (Ramel et al., 2012). Thus, pigment metabolism may be an important element of stress response.

The recovery of the photosynthetic performances (Ft and Qy) following re-hydration was time dependent. Qy values of fronds exposed to 30°C reached control values within 5 h of re-hydration but required at least 24 h in fronds exposed to higher temperatures (Figure 3B). The slow recovery of Qy performance indicates that heat exerts long-term stress on the PS II system, likely by interfering with the water oxidation complex (Srivastava et al., 1997) and/or PS II energy transfer (Kadir et al., 2007). Fronds re-hydrated after 60°C appeared photosynthetically functional but at significantly reduced efficiency (Figures 3A,B), which suggests that repair processes are damaged (Allakhverdiev et al., 2008). Photosynthetic activity (Qy) in re-hydrated fronds after 65°C was not detectable (Figure 3B), and indicates irreversible damage (Kadir et al., 2007). Thus, similar to morphological data, Ft and Qy measurements indicate that the maximal heat tolerance of dehydrated Pleopeltis is 60°C. These data indicate that chlorophyll and/or the reaction center remain intact in spite of absence of PS II activity. The lack of photosynthetic activity may protect the photosynthetic apparatus from damage.

Hydrated Fronds

Ft and Qy of partly and fully submersed (Figures 3C–F) fronds exposed to ≤ 35°C were not affected. However, at 40°C, Qy decreased while Ft increased. Similar to observations in dried tissue, this unequal response indicates a dichotomy between chlorophyll stability and reduced photosynthetic efficiency, possibly as a result from inactivation of the oxygen evolving system (Wise et al., 2004) and/or the PS II reaction center (Bolharnordenkampe et al., 1989). The reduction of Ft at > 40°C and non-detectable Qy (Figures 3D,F) indicates that the fronds become photosynthetically non-functional beyond 40°C and identifies the thermal tolerance of hydrated fronds as 40°C.

Electrolyte Leakage

An increase in conductivity of the external medium indicates cell membrane damage and efflux of ions (Ilik et al., 2018). High conductivity in fully submersed samples relative to partly submersed suggests that the integrity of the membrane is affected by the combination of heat and extent of immersion. Further, the absence of gas exchange seems to negatively impact membrane stability, especially at temperatures > 35°C. Low conductivity in partly and fully submersed samples at ≤ 35°C and no difference from the control likely represents regular ion exchange in intact membranes that is maintained until about 35°C (Figure 4A). During the ensuing 24 h recovery period, the (slight) decrease in conductivity suggests at least partial reuptake of ions (Figure 4B). Since re-absorption is an active process, it is likely that this process is dependent on the activity of plasma membrane proton ATPase, which is reported to be activated by the combination of high temperature and resulting membrane lipid modification (Viegas et al., 1995).

Leaching from leaves is broadly defined as removal of substances from plant leaves by action of rain, fog, dew, and washing (Tukey, 1970). Other factors such as stress, water content, nutrient availability, and physical characteristics of the tissue also influence the extent of leaching (Tukey, 1970). In partly submersed samples, presence of relatively lower amount of water and interaction of vapor mixture with the tissue surface may contribute to leaching. Additionally, since Pleopeltis fronds readily absorb water (John and Hasenstein, 2017), it is likely that water permeability contributes to ion loss. The higher quantity of ions in the leachate (Figure 5) and high conductivity (Figure 4) in fully submersed samples compared to partly submersed samples is likely proportional to the extent a submersion but indicates the deleterious effect of heat on membrane stability. The most abundant ion found in the leachate was K+ (Figure 5) consistent with its vital role in the osmoregulation (Cochrane and Cochrane, 2009). Loss of ions in general likely triggers ROS production that leads to oxidative stress and eventually cell death (Demidchik et al., 2014). Taken together, photosynthetic data (Figure 3) and cation leakage (Figure 4) suggest that thermal tolerance of hydrated fronds is 40°C.

Metabolism

Metabolically active cells rely on a steady supply of reduced compounds; therefore, the concentration of reduction equivalents is a measure of metabolic health. However, assessing the metabolic status of dried Pleopeltis through aqueous redox dyes is problematic because tissue rehydrates in the dye solution. Therefore, our data report the reduction capacity of dried fronds immediately after hydration. Nonetheless, the temperature and hydration variability of the data indicates that the measurements provide a meaningful estimate of the reduction capacity. The declining reducing capacity with increasing temperatures (Figure 6) is likely the result of diminished electron transport (Hüve et al., 2011)and uncoupled photosynthetic electron transport (Sharkey and Zhang, 2010; Awasthi et al., 2015). Because metabolic activity of dried fronds was detectable, dehydrated Pleopeltis remain metabolically active up to at 40°C (Figure 6). Metabolic changes in desiccated moss tissue resulted in a glassy state only after rapid desiccation where enzymatic reactions were absent. In contrast, slow drying achieved a “rubbery state” (Fernandez-Marin et al., 2013). We assume that the slow drying of Pleopeltis and its maintained flexibility is indicative of a non-glassy state with reduced metabolism.

Hydrated fronds showed higher metabolic activity than dried fronds up to 40°C (Figure 6) but similar values at higher temperatures. This observation corresponds to the heat sensitivity of imbibed seeds, which deteriorate at high temperature compared to dried seeds (Hill and Johnstone, 1985). The metabolism of hydrated fronds is similar to the photosynthetic performance (Figures 3C–F) and is similar to the thermotolerance of other tropical and sub-tropical plants (Hemantaranjan et al., 2014). Exposure of plants to heat loads beyond their tolerance level leads to senescence, necrotic symptoms (Figures 2E–I), or apoptosis (Reape and McCabe, 2008). Apoptosis or PCD is typically estimated by the loss of metabolic functions (as in Figure 6) and characterized by cell shrinkage, nuclear condensation and fragmentation, and breakup of a cell into small apoptotic bodies (van Doorn et al., 2011). In contrast, necrosis is characterized as a chaotic and uncontrolled form of cell death that involves early rupture of the plasma membrane (van Doorn et al., 2011) and confined swelling of the cell (Reape et al., 2008). Viability stains can assess overall cell health but cannot distinguish between PCD and necrosis (Reape et al., 2008). To determine the type of cell death that occurs in Pleopeltis in response to heat stress, examination of endomembranes, nuclease activity, and DNA integrity would be essential, as has been shown in carrot (McCabe et al., 1997) and tobacco cells (Burbridge et al., 2006).

Reactive Oxygen Species and Antioxidant Enzyme Activities

The increase of ROS (Figure 7) in dry and hydrated fronds suggests that Pleopeltis experiences oxidative stress (Ali et al., 2005; Awasthi et al., 2015). The decline of ROS for hydrated but not dried fronds at > 40°C indicates that dehydrated fronds are capable of coping with elevated ROS at higher temperatures than hydrated fronds. The high levels of peroxides at 40°C (Figures 7, 8) also support heat tolerance to about 40°C.

Pleopeltis, like most plants, responds to heat by enhanced production of ROS (Hemantaranjan et al., 2014), which in turn activate signal transduction and ultimately defense mechanisms and PCD (Burbridge et al., 2006). Therefore, the decrease of hydroperoxide (Figure 7) and lipid hydroperoxide (Figure 8) above 40°C indicates damaging, possibly lethal, shifts in the redox equilibrium (Foyer and Noctor, 2005; Suzuki et al., 2012).

In addition to elevated ROS, the decreased availability of antioxidants or activity of reducing enzymes likely enhances ROS toxicity. CAT, an important enzyme for the detoxification of H2O2, is sensitive to elevated temperatures (Figure 9) and has been reported to decline upon dehydration (John and Hasenstein, 2018). The heat correlated reduction of CAT activity suggests that CAT is unable to detoxify ROS as also reported by Ali et al. (2005). Reduced CAT activity and high amounts of hydroperoxides may lead to an oxidative environment that then enhances consumption of GSH, a phenomenon also observed in Arabidopsis (Queval et al., 2011) and barley mutants (Smith et al., 1985) that lack CAT activity. GSH-oxidation increases during dehydration (John and Hasenstein, 2018) and heat-stressed, dried fronds maintain their high GSH levels up to 40°C (Figure 10). Thus, GSH oxidizing enzymes have greater heat tolerance than CAT. It is also possible that the accumulation of the oxidized form of GSH (GSSG) in chloroplasts and vacuoles (Queval et al., 2011) is important for redox regulation, especially during stress (Smith et al., 1985; Tommasini et al., 1993).

Hydrated fronds accumulate high levels of hydro- (Figure 7) and lipid hydroperoxide (Figure 8) up to 40°C. These stress indicators could be a response to electrolyte leakage (Figure 4), as reported for bentgrass (Liu and Huang, 2000). However, unlike bentgrass which showed increased lipid peroxide and electrolyte leakage, Pleopeltis exhibited increased electrolyte leakage (Figure 4) but LOOH content decreased at > 40°C (Figure 8), which could result from interactions between peroxide (Figure 7) and membrane-bound unsaturated fatty acids (Figures 11B,C) (Blokhina et al., 2003). These results suggest that (hydrated) Pleopeltis membranes are affected even by temperatures below ≤ 40°C. Because CAT (Figure 9) and GSH consuming enzymes (Figure 10) may protect membranes, further research is needed to determine temperature effects on membrane integrity.

Fatty Acids

Stress-responsive metabolites in plants include fatty acids (Su et al., 2009; Xu et al., 2010; Zhong et al., 2011; Ahmad et al., 2013). Our data confirm this notion because the FA composition of Pleopeltis fronds changes with temperature and hydration (Figure 11). Increasing temperature reduces desaturation and overall FA quantity, which indicates that heat interferes with either fatty acid synthesis and/or stimulates fatty acid breakdown. On average, the relative proportion of unsaturated fatty acids in dried fronds was higher than in hydrated fronds (Supplementary Table 1), which may protect the temperature sensitive photosynthetic apparatus (Gombos et al., 1994). Additionally, unsaturation declined in dried fronds at temperatures > 40 and > 35°C in hydrated fronds (Figure 11), suggesting that heat stress increases saturation of fatty acids. Saturated FAs reduce membrane fluidity and enhance integrity (Ahmad et al., 2013; Sakhno et al., 2014). Both parameters are important for surviving high temperatures (Murata and Los, 1997; Upchurch, 2008). Additionally, the presence of polyunsaturated fatty acid makes membranes susceptible to peroxidation (Liu and Huang, 2004), which corresponds to our observation of higher LOOH in heat-stressed, dry fronds compared with hydrated fronds (Figure 8). Although saturated fatty acids (16:0 and 18:0) made up a small fraction of the total fatty acid pool (Figure 11), their presence likely contributes to membrane stability and heat tolerance (Liu and Huang, 2004; Ahmad et al., 2013).

The decline of all fatty acids at elevated temperatures (Figure 11) links the fatty acid content to senescence (Koiwai et al., 1981; Yang and Ohlrogge, 2009). Even though senescence is not detectable in dried fronds, high amounts of lipid hydroperoxides (Figure 8) imply that dehydrated fronds are also affected by heat-induced membrane damage. The sensitivity of FA spectra to temperature and hydration indicates that FA profiling can be an effective stress indicator. Future studies will decipher how the FA profile changes with the extent and duration of stress, and during recovery. Dried material undergoes metabolic reactions of lipids (Golovina et al., 2010) and longevity has been attributed to “differences in the structure or mobility of molecules within the solidified cytoplasm” (Ballesteros et al., 2017). The remaining elasticity of dried Pleopeltis fronds suggests that they are below the glass transition threshold and therefore capable of low-level metabolism. The changing levels of FAs are indicative of ongoing metabolism in tissue with low water content (Figure 11). One could speculate that the stress response to drying includes enhanced lipid biosynthesis (Quartacci et al., 2002) to maintain membrane fluidity (Murata and Los, 1997; Ahmad et al., 2013) and that elevated temperatures enhance respiration such that beta oxidation of FAs leads to their lowered content. Future studies will analyze the time course of these rather drastic changes, and how the FA profile changes during recovery.

Conclusion

The mechanism of Pleopeltis response to heat stress is complex. Our biochemical data indicate that > 40°C causes heat stress in Pleopeltis fronds. Despite obvious stress signals, dried fronds recovered after exposure up to 55°C while thermo-tolerance of hydrated fronds was limited to 40°C. The difference in heat tolerance between hydrated and dried fronds indicates that dehydration protects Pleopeltis from heat damage. Our data further illustrate the adaptability of this epiphytic fern to cope with environmental stress.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

SJ and KH conceived the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. SJ performed the research. Both authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was partially supported by NASA grants NNX10AP91G and NNX13AN05A.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2020.597731/full#supplementary-material

References

Ahmad, M., Nangyal, H., Sherwani, S., Islam, Z., and Shah, S. (2013). Effect of heat stress on fatty acids profiles of Aloe vera and Bryophyllum pinnatum leaves. World Appl. Sci. J. 28, 1592–1596.

Ali, M., Hahn, E.-J., and Paek, K.-Y. (2005). Effects of temperature on oxidative stress defense systems, lipid peroxidation and lipooxygenase activity in Phalaenopsis. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 43, 213–223. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2005.01.007

Allakhverdiev, S. I., Kreslavski, V. D., Klimov, V. V., Los, D. A., Carpentier, R., and Mohanty, P. (2008). Heat stress: an overview of molecular responses in photosynthesis. Photosynth. Res. 98, 541–550. doi: 10.1007/s11120-008-9331-0

Awasthi, R., Bhandari, K., and Nayyar, H. (2015). Temperature stress and redox homeostasis in agricultural crops. Front. Environ. Sci. 3:11. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2015.00011

Ballesteros, D., Hill, L. M., and Walters, C. (2017). Variation of desiccation tolerance and longevity in fern spores. J. Plant Physiol. 211, 53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2017.01.003

Banti, V., Mafessoni, F., Loreti, E., Alpi, A., and Perata, P. (2010). The heat-inducible transcription factor HsfA2 enhances anoxia tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 152, 1471–1483. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.149815

Bethke, G., Thao, A., Xiong, G. Y., Li, B. H., Soltis, N. E., Hatsugai, N., et al. (2016). Pectin biosynthesis is critical for cell wall integrity and immunity in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 28, 537–556. doi: 10.1105/tpc.15.00404

Bhardwaj, A. R., Joshi, G., Kukreja, B., Malik, V., Arora, P., Pandey, R., et al. (2015). Global insights into high temperature and drought stress regulates genes by RNA-Seq in economically important oilseed crop Brassica juncea. BMC Plant Biol. 15:9. doi: 10.1186/s12870-014-0405-1

Blokhina, O., Virolainen, E., and Fagerstedt, K. (2003). Antioxidants, oxidative damage and oxygen deprivation stress: a review. Ann. Bot. 91, 179–194. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcf118

Bolharnordenkampe, H. R., Long, S. P., Baker, N. R., Oquist, G., Schreiber, U., and Lechner, E. G. (1989). Chlorophyll fluorescence as a probe of the photosynthetic competence of leaves in the field - a review of current instrumentation. Funct. Ecol. 3, 497–514. doi: 10.2307/2389624

Bradford, M. (1976). A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3

Brüggemann, W., Bergmann, M., Nierbauer, K., Pflug, E., Schmidt, C., and Weber, D. (2009). Photosynthesis studies on European evergreen and deciduous oaks grown under Central European climate conditions: II. Photoinhibitory and light-independent violaxanthin deepoxidation and downregulation of photosystem II in evergreen, winter-acclimated European Quercus taxa. Trees 23, 1091–1100. doi: 10.1007/s00468-009-0351-y

Burbridge, E., Diamond, M., Dix, P. J., and Mccabe, P. F. (2006). Use of cell morphology to evaluate the effect of a peroxidase gene on cell death induction thresholds in tobacco. Plant Sci. 171, 139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2006.03.004

Cheeseman, J. M. (2006). Hydrogen peroxide concentrations in leaves under natural conditions. J. Exp. Bot. 57, 2435–2444. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erl004

Chen, J. P., Burke, J. J., and Xin, Z. G. (2018). Chlorophyll fluorescence analysis revealed essential roles of FtsH11 protease in regulation of the adaptive responses of photosynthetic systems to high temperature. BMC Plant Biol. 18:11. doi: 10.1186/s12870-018-1228-2

Cochrane, T. T., and Cochrane, T. A. (2009). Differences in the way potassium chloride and sucrose solutions effect osmotic potential of significance to stomata aperture modulation. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 47, 205–209. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2008.11.006

Demidchik, V. (2018). ROS-activated ion channels in plants: biophysical characteristics, physiological functions and molecular nature. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19:1263. doi: 10.3390/ijms19041263

Demidchik, V., Straltsova, D., Medvedev, S., Pozhvanov, G., Sokolik, A., and Yurin, V. (2014). Stress-induced electrolyte leakage: the role of K+-permeable channels and involvement in programmed cell death and metabolic adjustment. J. Exp. Bot. 65, 1259–1270. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru004

Eickmeier, W. (1986). The correlation between high-temperature and desiccation tolerances in a poikilohydric desert plant. Can. J. Bot. 64, 611–617. doi: 10.1139/b86-078

Ergin, S., Gülen, H., Kesici, M., Turhan, E., Ýpek, A., and Köksal, N. (2016). Effects of high temperature stress on enzymatic and nonenzymatic antioxidants and proteins in strawberry plants. Turkish J. Agric. For. 40, 908–917. doi: 10.3906/tar-1606-144

Farrant, J. M., Cooper, K., Kruger, L. A., and Sherwin, H. W. (1999). The effect of drying rate on the survival of three desiccation-tolerant angiosperm species. Ann. Bot. 84, 371–379. doi: 10.1006/anbo.1999.0927

Ferguson, I. B., Lurie, S., and Bowen, J. H. (1994). Protein-synthesis and breakdown during heat-shock of cultured pear (Pyrus-communis L) cells. Plant Physiol. 104, 1429–1437. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.4.1429

Fernandez-Marin, B., Kranner, I., San Sebastian, M., Artetxe, U., Laza, J. M., Vilas, J. L., et al. (2013). Evidence for the absence of enzymatic reactions in the glassy state. A case study of xanthophyll cycle pigments in the desiccation-tolerant moss Syntrichia ruralis. J. Exp. Bot. 64, 3033–3043. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert145

Foyer, C., and Noctor, G. (2005). Oxidant and antioxidant signalling in plants: a re-evaluation of the concept of oxidative stress in a physiological context. Plant Cell Environ. 28, 1056–1071. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2005.01327.x

Gaff, D. F. (1997). “Mechanisms of desiccation tolerance in resurrection vascular plants,” in Mechanisms of Environmental Stress Resistance in Plants, eds A. Basra and R. Basra (Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers), 43–58.

Gay, C. A., and Gebicki, J. A. (2003). Measurement of protein and lipid hydroperoxides in biological systems by the ferric-xylenol orange method. Anal. Biochem. 315, 29–35. doi: 10.1016/s0003-2697(02)00606-1

Georgieva, K., and Maslenkova, L. (2001). Drought induced changes in PS II activity in leaves from desiccation-sensitive plant Spinacia oleracea and desiccation-tolerant “resurrection” fern Polypodium polypodioides. Compt. Rend. Bulg. Acad. Sci. 54, 67–72.

Golovina, E. A., Van As, H., and Hoekstra, F. A. (2010). Membrane chemical stability and seed longevity. Eur. Biophys. J. 39, 657–668. doi: 10.1007/s00249-009-0543-9

Gombos, Z., Wada, H., Hideg, E., and Murata, N. (1994). The unsaturation of membrane-lipids stabilizes photosynthesis against heat-stress. Plant Physiol. 104, 563–567. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.2.563

Greer, D. H. (2015). Temperature-dependent responses of the photosynthetic and chlorophyll fluorescence attributes of apple (Malus domestica) leaves during a sustained high temperature event. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 97, 139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2015.10.002

Griffiths, C. A., Gaff, D. F., and Neale, A. D. (2014). Drying without senesence in resurrection plants. Front. Plant Sci. 5:36. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00036

Hambler, D. (1961). A poikilohydrous, poikilochlorophyllous angiosperm from Africa. Nature 191, 1415–1416. doi: 10.1038/1911415a0

Hasanuzzaman, M., Nahar, K., Alam, M., Roychowdhury, R., and Fujita, M. (2013). Physiological, biochemical, and molecular mechanisms of heat stress tolerance in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14, 9643–9684. doi: 10.3390/ijms14059643

Helseth, L. E., and Fischer, T. M. (2005). Physical mechanisms of rehydration in Polypodium polypodioides, a resurrection plant. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 71:061903.

Hemantaranjan, A., Bhanu, N., Singh, M., Yadav, D., Patel, P., and Singh, R. (2014). Heat stress responses and thermotolerance. Adv. Plants Agric. Res. 1, 62–70.

Hill, M., and Johnstone, C. (1985). “Heat damage and drying effects on seed quality,” in Producing Herbage Seeds, eds M. Hare and J. Brock (Palmerston North: Grassland Association), 53–57.

Hüve, K., Bichele, I., Rasulov, B., and Niinemets, Ü (2011). When it is too hot for photosynthesis: heat-induced instability of photosynthesis in relation to respiratory burst, cell permeability changes and H2O2 formation. Plant Cell Environ. 34, 113–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2010.02229.x

Ilik, P., Spundova, M., Sicner, M., Melkovicova, H., Kucerova, Z., Krchnak, P., et al. (2018). Estimating heat tolerance of plants by ion leakage: a new method based on gradual heating. New Phytol. 218, 1278–1287. doi: 10.1111/nph.15097

Jespersen, D., Zhang, J., and Huang, B. R. (2016). Chlorophyll loss associated with heat-induced senescence in bentgrass. Plant Sci. 249, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2016.04.016

Jiang, Y., and Huang, B. (2001). Drought and heat stress injury to two cool-season turfgrasses in relation to antioxidant metabolism and lipid peroxidation. Crop Sci. 41, 436–442. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2001.412436x

Jiang, Z. Y., Hunt, J. V., and Wolff, S. P. (1992). Ferrous ion oxidation in the presence of xylenol orange for detection of lipid hydroperoxide in low-density-lipoprotein. Anal. Biochem. 202, 384–389. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(92)90122-n

John, S. P., and Hasenstein, K. H. (2017). The role of peltate scales in desiccation tolerance of Pleopeltis polypodioides. Planta 245, 207–220. doi: 10.1007/s00425-016-2631-2

John, S. P., and Hasenstein, K. H. (2018). Biochemical responses of the desiccation-tolerant resurrection fern Pleopeltis polypodioides to dehydration and rehydration. J. Plant Physiol. 228, 12–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2018.05.006

Kadir, S., Von Weihe, M., and Al-Khatib, K. (2007). Photochemical efficiency and recovery of photosystem II in grapes after exposure to sudden and gradual heat stress. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 132, 764–769. doi: 10.21273/jashs.132.6.764

Kappen, L. (1964). Untersuchungen über den Jahreslauf der Frost-, Hitze- und Austrocknungsresistenz von Sporophyten einheimischer Polypodiaceen (Filicinae). Flora 155, 123–166. doi: 10.1016/s0367-1615(17)33347-5

Kappen, L. (1966). Der Einfluß des Wassergehaltes auf die Widerstandsfähigkeit von Pflanzen gegenüber hohen und tiefen Temperaturen, untersucht an Blättern einiger Farne und von Ramonda myconi. Flora 156, 427–445. doi: 10.1016/s0367-1836(17)30278-1

Koch, K., and Barthlott, W. (2009). Superhydrophobic and superhydrophilic plant surfaces: an inspiration for biomimetic materials. Philso. Trans. R. Soc. A 367, 1487–1509. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2009.0022

Koiwai, A., Matsuzaki, T., Suzuki, F., and Kawashima, N. (1981). Changes in total and polar lipids and their fatty-acid composition in Tobacco-leaves during growth and senescence. Plant Cell Physiol. 22, 1059–1065.

Kotak, S., Larkindale, J., Lee, U., Von Koskull-Doring, P., Vierling, E., and Scharf, K. D. (2007). Complexity of the heat stress response in plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 10, 310–316.

Lange, O. (1955). Untersuchungen über die hitzeresistenz der moose in beziehung zu ihrer verbreitung: i. die resistenz stark ausgetrockneter Moose. Flora 142, 381–399. doi: 10.1016/s0367-1615(17)33089-6

Lange, O. L. (1953). Hitze- und Trockenresistenz der Flechten in Beziehung zu ihrer Verbreitung. Flora 140, 39–97. doi: 10.1016/s0367-1615(17)31917-1

Layton, B. E., Boyd, M. B., Tripepi, M. S., Bitonti, B. M., Dollahon, M. N. R., and Balsamo, R. A. (2010). Dehydration-induced expression of a 31-kDa dehydrin in Polypodium polypodioides (Polypodiaceae) may enable large, reversible deformation of cell walls. Am. J. Bot. 97, 535–544. doi: 10.3732/ajb.0900285

Leuenberger, M., Morris, J. M., Chan, A. M., Leonelli, L., Niyogi, K. K., and Fleming, G. R. (2017). Dissecting and modeling zeaxanthin- and lutein-dependent nonphotochemical quenching in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 114, E7009–E7017.

Lima, R., dos Santos, T. B., Vieira, L., Ferrarese, M. D. L. L., Ferrarese-Filho, O., Donatti, L., et al. (2013). Heat stress causes alterations in the cell-wall polymers and anatomy of coffee leaves (Coffea arabica L.). Carbohydr. Polym. 93, 135–143. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.05.015

Lipiec, J., Doussan, C., Nosalewicz, A., and Kondracka, K. (2013). Effect of drought and heat stresses on plant growth and yield: a review. Int. Agrophys. 27, 463–477. doi: 10.2478/intag-2013-0017

Liu, X., and Huang, B. (2004). Changes in fatty acid composition and saturation in leaves and roots of creeping bentgrass exposed to high soil temperatures. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 129, 795–801. doi: 10.21273/jashs.129.6.0795

Liu, X. Z., and Huang, B. R. (2000). Heat stress injury in relation to membrane lipid peroxidation in creeping bentgrass. Crop Sci. 40, 503–510. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2000.402503x

Lu, P., Sang, W., and Ma, K. (2008). Differential responses of the activities of antioxidant enzymes to thermal stresses between two invasive Eupatorium species in China. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 50, 393–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2007.00583.x

Macfarlane, J. D., and Kershaw, K. A. (1978). Thermal sensitivity in Lichens. Science 201, 739–741. doi: 10.1126/science.201.4357.739

Maslenkova, L. T., and Homann, P. H. (2000). Stabilized S2 state in leaves of the desiccation tolerant resurrection fern Polypodium polypodioides. CR Bulg. Acad. Sci. 53, 99–102.

Mathur, S., Agrawal, D., and Jajoo, A. (2014). Photosynthesis: response to high temperature stress. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 137, 116–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2014.01.010

Maxwell, K., and Johnson, G. N. (2000). Chlorophyll fluorescence - a practical guide. J. Exp. Bot. 51, 659–668. doi: 10.1093/jxb/51.345.659

McCabe, P. F., Levine, A., Meijer, P. J., Tapon, N. A., and Pennell, R. I. (1997). A programmed cell death pathway activated in carrot cells cultured at low cell density. Plant J. 12, 267–280. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1997.12020267.x

Meyer, H., and Santarius, K. A. (1998). Short-term thermal acclimation and heat tolerance of gametophytes of mosses. Oecologia 115, 1–8. doi: 10.1007/s004420050484

Microsoft Corporation (2016). Available online at: https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-365/excel

Murata, N., and Los, D. (1997). Membrane fluidity and temperature perception. Plant Physiol. 115, 875–879. doi: 10.1104/pp.115.3.875

Murchie, E. H., and Lawson, T. (2013). Chlorophyll fluorescence analysis: a guide to good practice and understanding some new applications. J. Exp. Bot. 64, 3983–3998. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert208

Pessin, L. J. (1924). A physiological and anatomical study of the leaves of Polypodium polypodioides. Am. J. Bot. 11, 370–381. doi: 10.1002/j.1537-2197.1924.tb05783.x

Qu, G. Q., Liu, X., Zhang, Y. L., Yao, D., Ma, Q. M., Yang, M. Y., et al. (2009). Evidence for programmed cell death and activation of specific caspase-like enzymes in the tomato fruit heat stress response. Planta 229, 1269–1279. doi: 10.1007/s00425-009-0908-4

Quartacci, M., Glišiæ, O., Stevanoviæ, B., and Navari-Izzo, F. (2002). Plasma membrane lipids in the resurrection plant Ramonda serbica following dehydration and rehydration. J. Exp. Bot. 53, 2159–2166. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erf076

Queval, G., Jaillard, D., Zechmann, B., and Noctor, G. (2011). Increased intracellular H2O2 availability preferentially drives glutathione accumulation in vacuoles and chloroplasts. Plant Cell Environ. 34, 21–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2010.02222.x

Ramel, F., Birtic, S., Cuine, S., Triantaphylides, C., Ravanat, J. L., and Havaux, M. (2012). Chemical quenching of singlet oxygen by carotenoids in plants. Plant Physiol. 158, 1267–1278. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.182394

Reape, T. J., and McCabe, P. F. (2008). Apoptotic-like programmed cell death in plants. New Phytol. 180, 13–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02549.x

Reape, T. J., Molony, E. M., and Mccabe, P. F. (2008). Programmed cell death in plants: distinguishing between different modes. J. Exp. Bot. 59, 435–444. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm258

Rizhsky, L., Liang, H., and Mittler, R. (2002). The combined effect of drought stress and heat shock on gene expression in Tobacco. Plant Physiol. 130, 1143–1151. doi: 10.1104/pp.006858

Sakhno, L., Slyvets, M., Korol, N., Karbovska, N., Ostapchuk, A., Sheludko, Y., et al. (2014). Changes in fatty acid composition in leaf lipids of Canola Biotech plants under short-time heat stress. J. Stress Physiol. Biochem. 10, 24–34.

Schelbert, S., Aubry, S., Burla, B., Agne, B., Kessler, F., Krupinska, K., et al. (2009). Pheophytin Pheophorbide Hydrolase (Pheophytinase) Is Involved in Chlorophyll Breakdown during Leaf Senescence in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 21, 767–785. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.064089

Sharkey, T. D., and Zhang, R. (2010). High temperature effects on electron and proton circuits of photosynthesis. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 52, 712–722. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2010.00975.x

Smith, I. K., Kendall, A. C., Keys, A. J., Turner, J. C., and Lea, P. J. (1985). The regulation of the biosynthesis of glutathione in leaves of barley (Hordeum vulgare L). Plant Sci. 41, 11–17. doi: 10.1016/0168-9452(85)90059-7

Srivastava, A., Guisse, B., Greppin, H., and Strasser, R. J. (1997). Regulation of antenna structure and electron transport in Photosystem II of Pisum sativum under elevated temperature probed by the fast polyphasic chlorophyll a fluorescence transient: OKJIP. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 1320, 95–106. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(97)00017-0

Starlin, T., and Gopalakrishnan, V. K. (2013). Enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant properties of Tylophora pauciflora Wight and Arn.–An in vitro study. Asian J. Pharm Clin. Res. 6, 68–71.

Stuart, T. S. (1968). Revival of respiration and photosynthesis in dried leaves of Polypodium polypodioides. Planta 83, 185–206. doi: 10.1007/bf00385023

Su, K., Bremer, D., Jeannotte, R., Welti, R., and Yang, C. (2009). Membrane lipid composition and heat tolerance in cool-sesaon turfgrasses, including a hybrid bluegrass. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 134, 511–520. doi: 10.21273/jashs.134.5.511

Suzuki, N., Koussevitzky, S., Mittler, R., and Miller, G. (2012). ROS and redox signalling in the response of plants to abiotic stress. Plant Cell Environ. 35, 259–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2011.02336.x

Tegler, B., and Kershaw, K. A. (1981). Physiological-environmental interactions in lichens. XII. The seasonal-variation of the heat-stress response of Cladonia rangiferina. New Phytol. 87, 395–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1981.tb03210.x

Tommasini, R., Martinoia, E., Grill, E., Dietz, K. J., and Amrhein, N. (1993). Transport of Oxidized Glutathione into barley vacuoles–evidence for the involvement of the glutathione-S-conjugate ATPase. Z. Naturforsch. C 48, 867–871. doi: 10.1515/znc-1993-11-1209

Tukey, H. B. J. (1970). The leaching of substances from plants. Ann. Rev. Plant Physiol. 21, 305–324. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pp.21.060170.001513

Upchurch, R. (2008). Fatty acid unsaturation, mobilization, and regulation in the response of plant to stress. Biotechnol. Lett. 30, 967–977. doi: 10.1007/s10529-008-9639-z

van Doorn, W. G., Beers, E. P., Dangl, J. L., Franklin-Tong, V. E., Gallois, P., Hara-Nishimura, I., et al. (2011). Morphological classification of plant cell deaths. Cell Death Differ. 18, 1241–1246. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.36

Veerasamy, M., He, Y., and Huang, B. (2007). Leaf senescence and protein metabolism in creeping bentgrass exposed to heat stress and treated with cytokinins. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 132, 467–472. doi: 10.21273/jashs.132.4.467

Viegas, C., Sebastião, P., Nunes, A., and Sá-Correia, I. (1995). Activation of plasma membrane H1-ATPase and expression of PMA1 and PMA2 genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells grown at supraoptimal temperatures. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61, 1904–1909. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.5.1904-1909.1995

Vieweg, G., and Ziegler, H. (1969). Zur Physiologie von Myrothamnus flabellifolia. Ber. Dtsch. Bot. Ges. 82, 29–36.

Voesenek, L., Colmer, T., Pierik, R., Millenaar, F., and Peeters, A. (2006). How plants cope with complete submergence. New Phytol. 170, 213–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01692.x

Wang, D., Heckathorn, S., Mainali, K., and Tripathee, R. (2016). Timing effects of heat-stress on plant ecophysiological characteristics and growth. Front. Plant Sci 7:1629. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01629

Wang, P., Zhao, L., Hou, H. L., Zhang, H., Huang, Y., Wang, Y. P., et al. (2015). Epigenetic changes are associated with programmed cell death induced by heat stress in seedling leaves of Zea mays. Plant Cell Physiol. 56, 965–976. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcv023

Wen, X. G., Gong, H. M., and Lu, C. M. (2005). Heat stress induces a reversible inhibition of electron transport at the acceptor side of photosystem II in a cyanobacterium Spirulina platensis. Plant Sci. 168, 1471–1476. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2005.01.015

Willats, W. G. T., Orfila, C., Limberg, G., Buchholt, H. C., Van Alebeek, G., Voragen, A. G. J., et al. (2001). Modulation of the degree and pattern of methyl-esterification of pectic homogalacturonan in plant cell walls - Implications for pectin methyl esterase action, matrix properties, and cell adhesion. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 19404–19413. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m011242200

Wise, R. R., Olson, A. J., Schrader, S. M., and Sharkey, T. D. (2004). Electron transport is the functional limitation of photosynthesis in field-grown Pima cotton plants at high temperature. Plant Cell Environ. 27, 717–724. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2004.01171.x

Wolff, S. (1994). Ferrous ion oxidation in presence of ferric ion indicator xylenol orange for measurement of hydroperoxides. Methods Enzymol. 233, 182–189. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(94)33021-2

Wu, H. C., Bulgakov, V. P., and Jinn, T. L. (2018). Pectin Methylesterases: cell wall remodeling proteins are required for plant response to heat stress. Front. Plant Sci 9:1612. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01612

Xu, L., Han, L., and Huang, B. (2010). Membrane fatty acid composition and saturation levels associated with leaf dehydration tolerance and post-drought rehydration in Kentucky bluegrass. Crop Sci. 51, 273–281. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2010.06.0368

Xu, Y., and Huang, B. (2007). Heat-induced leaf senescence and hormonal changes for thermal bentgrass and turf-type bentgrass species differing in heat tolerance. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 132, 185–192. doi: 10.21273/jashs.132.2.185

Yamada, M., Hidaka, T., and Fukamachi, H. (1996). Heat tolerance in leaves of tropical fruit crops as measured by chlorophyll fluorescence. Sci. Hortic. 67, 39–48. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4238(96)00931-4

Yang, Z. L., and Ohlrogge, J. B. (2009). Turnover of fatty acids during natural senescence of Arabidopsis, Brachypodium, and Switchgrass and in Arabidopsis beta-Oxidation Mutants. Plant Physiol. 150, 1981–1989. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.140491

Zandalinas, S., Mittler, R., Balfagón, D., Arbona, V., and Gómez-Cadenas, A. (2018). Plant adaptations to the combination of drought and high temperatures. Physiol. Plant. 162, 2–12. doi: 10.1111/ppl.12540

Keywords: heat stress, hydroperoxide, lipid hydroperoxide, antioxidative enzymes, Pleopeltis polypodioides, fatty acids

Citation: John SP and Hasenstein KH (2020) Desiccation Mitigates Heat Stress in the Resurrection Fern, Pleopeltis polypodioides. Front. Plant Sci. 11:597731. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.597731

Received: 21 August 2020; Accepted: 10 November 2020;

Published: 30 November 2020.

Edited by:

Eric Ruelland, UMR 7618 Institut d’écologie et des sciences de l’environnement de Paris (IEES), FranceReviewed by:

Jose Ignacio Garcia-Plazaola, University of the Basque Country, SpainThomas Roach, University of Innsbruck, Austria

Copyright © 2020 John and Hasenstein. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Karl H. Hasenstein, aGFzZW5zdGVpbkBsb3Vpc2lhbmEuZWR1

Susan P. John

Susan P. John Karl H. Hasenstein

Karl H. Hasenstein