94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Plant Sci. , 05 November 2020

Sec. Plant Physiology

Volume 11 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2020.582353

Plant ribosomal proteins play universal roles in translation, although they are also involved in developmental processes and hormone signaling pathways. Among Arabidopsis RPL10 family members, RPL10A exhibits the highest expression during germination and early development, suggesting that RPL10A is the main contributor to these processes. In this work, we first analyzed RPL10A expression pattern in Arabidopsis thaliana using transgenic RPL10Apro:GUS plants. The gene exhibits a ubiquitous expression pattern throughout the plant, but it is most strongly expressed in undifferentiated tissues. Interestingly, gene expression was also detected in stomatal cells. We then examined protein function during seedling establishment and abscisic acid (ABA) response. Heterozygous rpl10A mutant plants show decreased ABA-sensitivity during seed germination, are impaired in early seedling and root development, and exhibit reduced ABA-inhibition of stomatal aperture under light conditions. Overexpression of RPL10A does not affect the germination and seedling growth, but RPL10A-overexpressing lines are more sensitive to ABA during early plant development and exhibit higher stomatal closure under light condition both with and without ABA treatment than wild type plants. Interestingly, RPL10A expression is induced by ABA. Together, we conclude that RPL10A could act as a positive regulator for ABA-dependent responses in Arabidopsis plants.

Plant ribosomal proteins exist as families of two or more members, which are incorporated into the ribosome in certain tissues or under particular situations (Byrne, 2009; Moin et al., 2016a). Several evidences indicate that, in eukaryotes, the ribosome heterogeneity conferred by different ribosomal components allows the selective translation of specific mRNAs (Byrne, 2009; Moin et al., 2016a; Calamita et al., 2018). The characterization of Arabidopsis thaliana ribosomal protein mutant plants, as well as the complementation observed between paralog genes, has demonstrated partial and even absence of redundancy between family members. Each family member acts specifically at different developmental stages, in different tissues or under particular stress conditions (Sormani et al., 2011; Horiguchi et al., 2012; Hummel et al., 2012). Arabidopsis mutants in genes encoding ribosomal proteins exhibit a wide range of developmental phenotypes, including extreme anomalies such as embryo lethality, suggesting that ribosomes could also have specific functions during development (Degenhardt and Bonham-Smith, 2008; Horiguchi et al., 2012; Carroll, 2013).

Under sub-optimal environmental conditions, such as hypoxia, salinity, and heat, different studies have shown that the abundance of a transcript does not necessarily correlate with its association with polysomes and, therefore, with its translational level (Juntawong et al., 2014; Yamasaki et al., 2015). Furthermore, the absence of correlation between transcription and translation was demonstrated in Arabidopsis seeds during imbibition and germination (Basbouss-Serhal et al., 2015). During germination, gene expression is mainly regulated at a translational level and involves the selective and dynamic recruitment of specific mRNA to polysomes (Basbouss-Serhal et al., 2015). In this way, components of the translational machinery, such as ribosomal proteins, are key players in the regulation of the germination process.

The ribosomal protein L10 (RPL10), a component of the major subunit (60S) of the ribosome, is a key factor to form the 80S functional ribosome (Hofer et al., 2007). Arabidopsis has three genes encoding RPL10 proteins, RPL10A, RPL10B, and RPL10C. Previously, we have demonstrated that Arabidopsis RPL10 genes are differentially regulated by UV-B radiation and are not functionally equivalent (Falcone Ferreyra et al., 2010a). Homozygous rpl10A mutants are not viable, indicating that RPL10A is essential for plant survival; homozygous rpl10B plants exhibit abnormal growth and development in both their vegetative and reproductive stages, while homozygous rpl10C plants do not exhibit phenotypic differences compared to wild type plants under normal growth conditions. All the three RPL10 proteins are localized both in the cytosol and the nuclei, suggesting that these proteins have extra-ribosomal functions (Falcone Ferreyra et al., 2013). This observation is supported by other studies, which have also proposed RPL10 extra-ribosomal roles in several eukaryotic organisms, including plants, such as transcriptional regulation under stress responses (Singh et al., 2009; Zorzatto et al., 2015; Moin et al., 2016a,b; Shi et al., 2017).

Previous reports indicate that RPL10A plays a predominant role during abiotic and biotic stresses (Imai et al., 2008; Falcone Ferreyra et al., 2010a, 2013; Zorzatto et al., 2015), and published microarray and RNA-seq gene expression data show that RPL10A, among Arabidopsis RPL10 family members, exhibits the highest expression during germination and early development (Klepikova et al., 2016). Moreover, plant ribosomal proteins are also involved in different hormone signaling pathways (Cherepneva et al., 2003; Guo et al., 2011; Rosado et al., 2012; Moin et al., 2016b; Denver and Ullah, 2019). Here, we aim to gain further insights in the contribution of RPL10A during plant development and abscisic acid (ABA) responses.

ABA plays important roles during plant growth and development, including seed dormancy and germination, vegetative growth, radicular architecture, and stomatal movement (Sah et al., 2016; Santos Teixeira and ten Tusscher, 2019). In addition, ABA promotes leaf senescence and regulates responses to both biotic and abiotic stresses. Low water availability resulting from drought, high salinity, and cold promotes ABA synthesis, which stimulates stomatal closure and modulates gene expression changes so that plants can cope with stressful conditions (Ng et al., 2014; Sah et al., 2016).

Our data show that RPL10A is ubiquitously expressed throughout A. thaliana, but it is most strongly expressed in undifferentiated tissues. Interestingly, gene expression was also detected in stomatal cells. We then examined the role of the protein in regulating germination and seedling development. We have used heterozygous rpl10A mutant and RPL10A-overexpressing lines. We demonstrate that the mutant and overexpressing lines are less and more sensitive to ABA, respectively, than wild type plants, evidenced by an altered germination percentage, cotyledon greening percentage, primary root elongation, lateral root (LR) density, petiole length, leaf number, chlorophyll content, and water loss. Even more, RPL10A transcript levels do not increase in abi3 and abi5 mutants as in wild type seedlings. These results suggest that RPL10A is required for some ABA-dependent responses.

Arabidopsis thaliana ecotypes, Columbia-0 (Col-0, hereinafter referred to as WT), Wassilewskja (hereinafter referred to as WT Ws), and Landsberg erecta (hereinafter referred to as WT Ler), were used in this study. Seeds were vernalized for 3 days at 4°C in plates containing MS medium (Murashige and Skoog plant salt mixture) supplemented with 0.7% (w/v) agar or in pots containing soil, as indicated. Plates and pots were then placed in a growth chamber under a light intensity of 100 μE m−2 s−1 with a photoperiod of 16-h-light/8-h-dark at 22°C. The abi3-1 mutant (CS24, background Ler-0) and the abi5-1 mutant (CS8105, background Ws) were obtained from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (ABRC, Columbus, OH). The rpl10A heterozygous mutant lines (SALK 010170 and SALK 106656, designed rpl10A-1 and rpl10A-2, respectively) and transgenic RPL10Apro:GUS plants were previously described (Falcone Ferreyra et al., 2013).

For ABA treatment in MS liquid medium, seedlings previously grown on MS-agar plates for 14 days were transferred to MS liquid medium supplemented or not with 5, 10, and 20 μM ABA and incubated under light conditions (with a photoperiod of 16-h-light/8-h-dark) with gentle agitation. Afterwards, seedlings were collected at 4 and 24 h after treatment and stored at −80°C until use.

Arabidopsis thaliana seeds were surface sterilized, sown on MS-agar plates with or without ABA supplementation, as indicated. After stratification at 4°C for 3 days in the dark, plates were transferred to a grow chamber at 22°C, under a photoperiod of 16-h-light/8-h-dark and a light intensity of 100 μE m−2 s−1. Germination was monitored at the indicated times (h) by counting the frequency of radicle emergence through the seed coat. The percentage of inhibition of germination by exogenous ABA was calculated using the following formula: [(Germination % in MS – Germination % in MS + ABA) / (Germination % in MS)] × 100. Cotyledon greening is defined as the full opening of green cotyledons, while seedling stage is recorded when leaf #4 is emerging. Experiments were performed in triplicate, with at least 100 seeds each. For all genotypes analyzed, seeds had same after-ripening time periods.

For analysis of the ABA effect after germination, seedlings previously grown on MS-agar plates for 7 days were transferred to MS-agar medium supplemented or not with 5 and 10 μM ABA. Leaf numbers, petiole lengths, and chlorophyll contents were measured over time for 10 days. Seedlings were photographed 8 and 10 days after the transfer.

Three independent T3 transgenic lines (RPL10Apro:GUS) were used for histochemical analysis. Transgenic RPL10Apro:GUS seeds were sown in MS-agar plates. Samples were collected at different developmental stages (germinative and post-germinative) to further stain with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-D-glucuronide at 37°C for 24 h, followed by washes with ethanol. Seedlings were kept in 50% (v/v) ethanol and 5% (v/v) acetic acid before being photographed. Germinated seed stage is defined as a visible radicle protrusion through the seed coat. Samples were collected for staining at 22 or 46 h after stratification in the absence or presence of ABA, respectively. Cotyledon greening stage is defined as the full opening of green cotyledons. Samples were collected for staining at 4 or 8 days after stratification in the absence or presence of ABA, respectively.

For guard cells staining, 8-day-old seedlings were first stained and abaxial epidermis was further peeled from leaves as described below. The experiments were repeated three times using at least three independent lines with similar results.

To generate RPL10A-overexpressing plants, the full-length ORF of RPL10A was amplified by PCR using F-KpnI-AtRPL10A and R-SalI-AtRPL10A primers containing the KpnI and SalI restriction sites for cloning and the start and stop codons, respectively (Supplementary Table S1; Falcone Ferreyra et al., 2013). PCR reaction was performed using Platinum Pfx DNA polymerase (Invitrogen) under the following conditions: 1X Pfx buffer, 1.5 mM MgSO4, 0.5 μM of each primer, 0.2 mM of each dNTP, 0.5 U Platinum Pfx DNA polymerase, and the plasmid pCHF3:AtRPL10A-GFP as template in 25 μl of final volume. Cycling conditions were as follows: 60 s denaturation at 95°C, followed by 35 cycles of 20 s denaturation at 95°C, 30 s annealing at 60°C, 60 s amplification at 68°C, and a final extension of 7 min at 68°C. The PCR product was purified, cut with the corresponding KpnI and SalI restriction enzymes, purified and cloned into pCS052_GFP_pCHF3 vector (a modified version of pCHF3; Falcone Ferreyra et al., 2013) previously cut with the same enzymes, generating 35Spro:RPL10A construct. The absence of random mutations in the PCR amplified fragment was determined by DNA sequencing. The 35Spro:RPL10A construct was transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 by electroporation, and the transformation of A. thaliana plants (WT) by the resulting bacteria was performed by the floral dip method (Clough and Bent, 1998). Transformed seedlings (T1) were identified by selection on solid MS medium containing kanamycin (50 mg L−1), and the plants were then transferred to soil. Further analysis of transgenic plants was carried out by PCR as described in Falcone Ferreyra et al. (2013) on the genomic DNA using the combination of primers: F-35Sprom and the reverse primer R-RPL10A-RT2. The expression of the AtRPL10A in transformed plants was analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR using F-RPL10A-RT2 and R-RPL10A-RT2 primers (Supplementary Table S1).

Total RNA was isolated from 100 mg of tissues using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) followed by DNase treatment (Promega, Madison, WI). RNA was converted into first-strand cDNA using SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) with oligo-dT as a primer. The resultant cDNA was used as a template for quantitative PCR amplification in a MiniOPTICON2 apparatus (Bio-Rad), using the intercalation dye SYBRGreen I (Invitrogen) as a fluorescent reporter and Platinum Taq DNA Polymerase (Invitrogen). Primers were designed to generate unique 150–250 bp fragments using the PRIMER3 software (Rozen and Skaletsky, 2000). The experiments were carried out using three biological replicates. Data of ABA treatments were normalized to ACTIN2 (ACT2) transcript. All primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table S1. Amplification conditions were as follows: 2 min denaturation at 94°C, 40–45 cycles at 94°C for 10 s, 57°C for 15 s, and 72°C for 20 s, followed by 10 min at 72°C. Melting curves for each PCR assay were determined by measuring the decrease of fluorescence with increasing temperature (from 65 to 98°C). To confirm the size of the PCR products and to check that they corresponded to a unique and expected product, the final products were separated on a 2% (w/v) agarose gel.

Total chlorophylls (Chl) were determined by standard procedures (Wintermans and De Mots, 1965). Leaves #3 were harvested, photographed, and petiole lengths were measured using ImageJ software.

Five-day-old seedlings grown on MS-agar plates were transferred to MS-agar plates supplemented or not with 10 μM ABA and held in vertical position in a growth chamber. Plates were photographed immediately after the transfer, and every day for the following 4 days. Images were analyzed using the ImageJ software. Experiments were performed in triplicate using 20 biological samples in each case.

Fully expanded leaves #5 were harvested from 3-week-old wild type (WT Col-0), heterozygous rpl10A-1 mutant plants, and RPL10A-overexpressing lines (RPL10A-OE3 and RPL10A-OE5) before the light period, placed into culture dishes and floated in an opening medium containing 10 mM KCl, 7.5 mM iminodiacetic acid, and 10 mM MES (pH 6.15) for 2.5 h in the growth chamber under dark to ensure that stomata were fully closed. Then, one group of samples were harvested, while the other group was transferred to the light and further incubated for 2 h in the same opening solution containing 20 μM ABA or without supplementation (control), to ensure that most of the stomata of the control samples were fully opened. After treatments (under dark and light conditions in the presence or absence of ABA), the abaxial epidermis was peeled from leaves and stomata were immediately photographed using a Leica microscope with a 40X objective. Stomatal apertures were measured using ImageJ software. For each condition, at least three leaves from different plants were used and 60 stomatal apertures were measured. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

For water loss measurement, fully expanded #5 leaves were detached from 3-week-old wild type (WT Col-0), heterozygous rpl10A-1 mutant, and RPL10A-overexpressing plants, immediately weighed on a piece of weighing paper, and their petioles were immersed in a solution supplemented or not with 20 μM ABA under white light for 1 h. Leaves were further weighed and allowed to air dry for 5 h. Alternatively, 3-week-old rosettes of WT, heterozygous rpl10A-1 mutant, and RPL10A-overexpressing plants were detached and water loss measurements were carried out as described above. Fresh weight was recorded at each hour and normalized to the initial fresh weight. The percentage of water loss (%) was calculated as the difference. Experiments were carried out in triplicate, using at least 10 leaves #5 from different plants in each experiment.

For germination, early plant development and root elongation inhibition assays in the presence of ABA, heterozygous rpl10A mutant plants (rpl10A/+) were identified after the experiments were finished by PCR on genomic DNA using specific primers for RPL10A gene and one primer that hybridizes with the left border of the T-DNA. For stomatal aperture measurement, water loss experiments, and RT-qPCR analysis, rpl10A-1/+ mutant plants were previously identified by PCR using genomic DNA extracted from leaves #1/#2 of 12-day-old seedlings. Primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Data were subjected to a two-factorial ANOVA, applying Tukey, Bonferroni, and Duncan tests (p < 0.05). When comparing two data sets, Student’s t test was used (p < 0.05). Statistical analysis of the data was obtained using InfoStat software v. 2017 (Di Rienzo et al., 2017).

In silico analysis of RPL10A promoter was done using the following database: AGRIS,1 AthaMap,2 PlantPAN2.0,3 and PLACE.4

Sequence data from this article can be found in the Arabidopsis Genome Initiative under the following accession numbers: ACTIN2, At3g18780; RPL10A, At1g14320; RPL10B, At1g26910; and RPL10C, At1g66580.

Previous reported microarray and RNA-seq gene expression studies have indicated that RPL10A transcript levels increase at 6 h imbibition after stratification (Narsai et al., 2011) are maintained up to 24 h and are higher than RPL10B and RPL10C transcript levels (Klepikova et al., 2016; Supplementary Figures S1A,B). In addition, RPL10A transcript levels in root, cotyledons, hypocotyl, and shoot apical meristem from 1-day-old seedlings are higher than those of RPL10B and RPL10C (Klepikova et al., 2016; Supplementary Figure S1C). These comparative analyses show that RPL10A is the most abundantly expressed gene of the RPL10 family members and suggest that RPL10A could play important roles during seed germination and early seedling development.

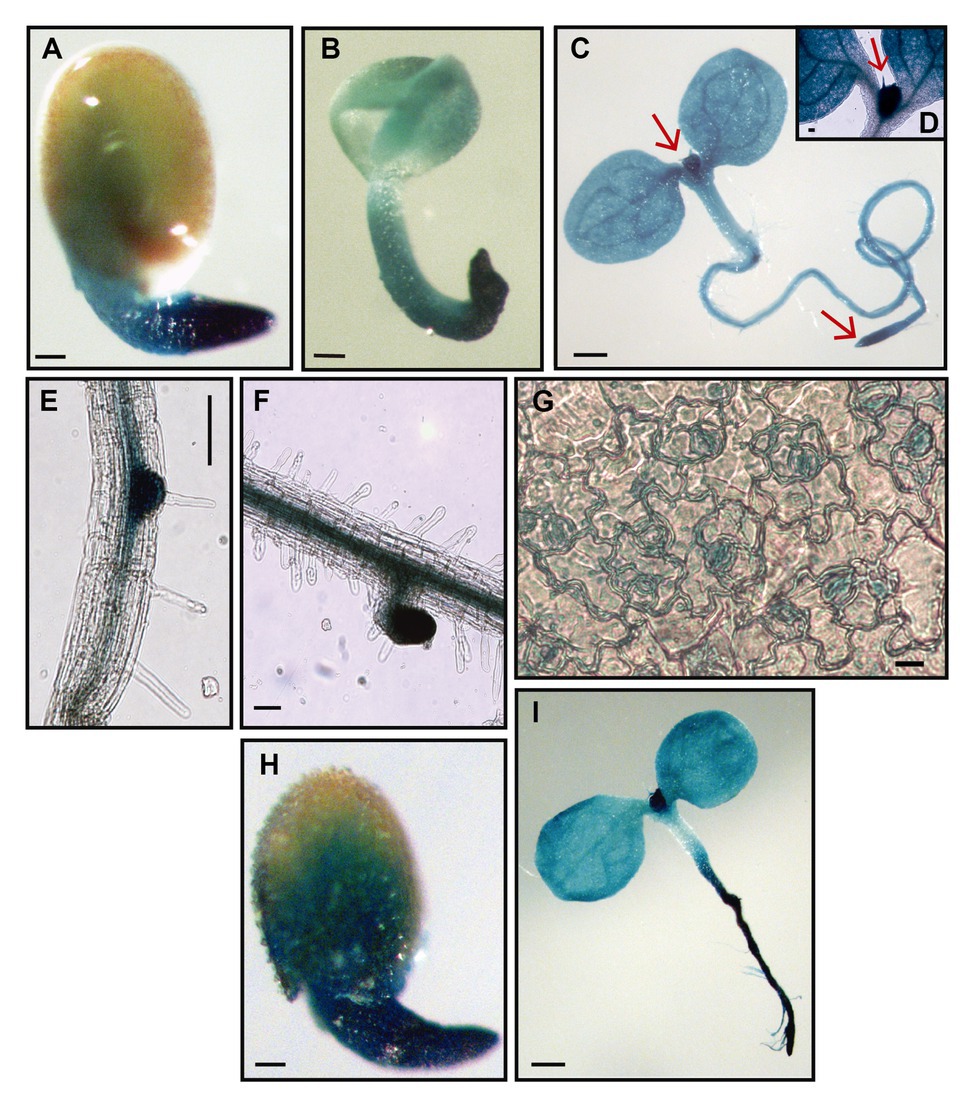

Thus, we first analyzed RPL10A expression pattern during development using transgenic RPL10Apro:GUS plants previously generated (Falcone Ferreyra et al., 2013). RPL10A was highly expressed in germinated seeds (Figures 1A,B) and early seedlings (Figure 1C), with strong GUS staining in proliferating tissues such as shoot and root apical meristems (Figures 1C,D). Furthermore, high RPL10A expression was also observed during lateral root (LR) emergence and in elongated LRs (Figures 1E,F). GUS signal was also detected in stomatal cells (Figure 1G).

Figure 1. Histochemical GUS staining of transgenic RPL10Apro:GUS plants. (A) Germinated seed, 22 h after stratification. (B) Germinated seed without the testa, 22 h after stratification. (C) Four-day-old seedling at cotyledon greening stage. (D) Shoot apical meristem from 4-day-old seedling. (E) Primary root during lateral root emergence. (F) Lateral root from 7-day-old seedling. (G) Abaxial epidermis peeled from leaves #1/2 of 8-day-old seedlings. (H) Germinated seed, 46 h after stratification, with 1 μM abscisic acid (ABA). (I) Eight-day-old seedling at cotyledon greening stage, with 1 μM ABA. Arrows point to shoot apical meristem (C,D) and root apical meristem (C). Scale bars, 100 μm (A-C,H,I) and 10 μm (E-G).

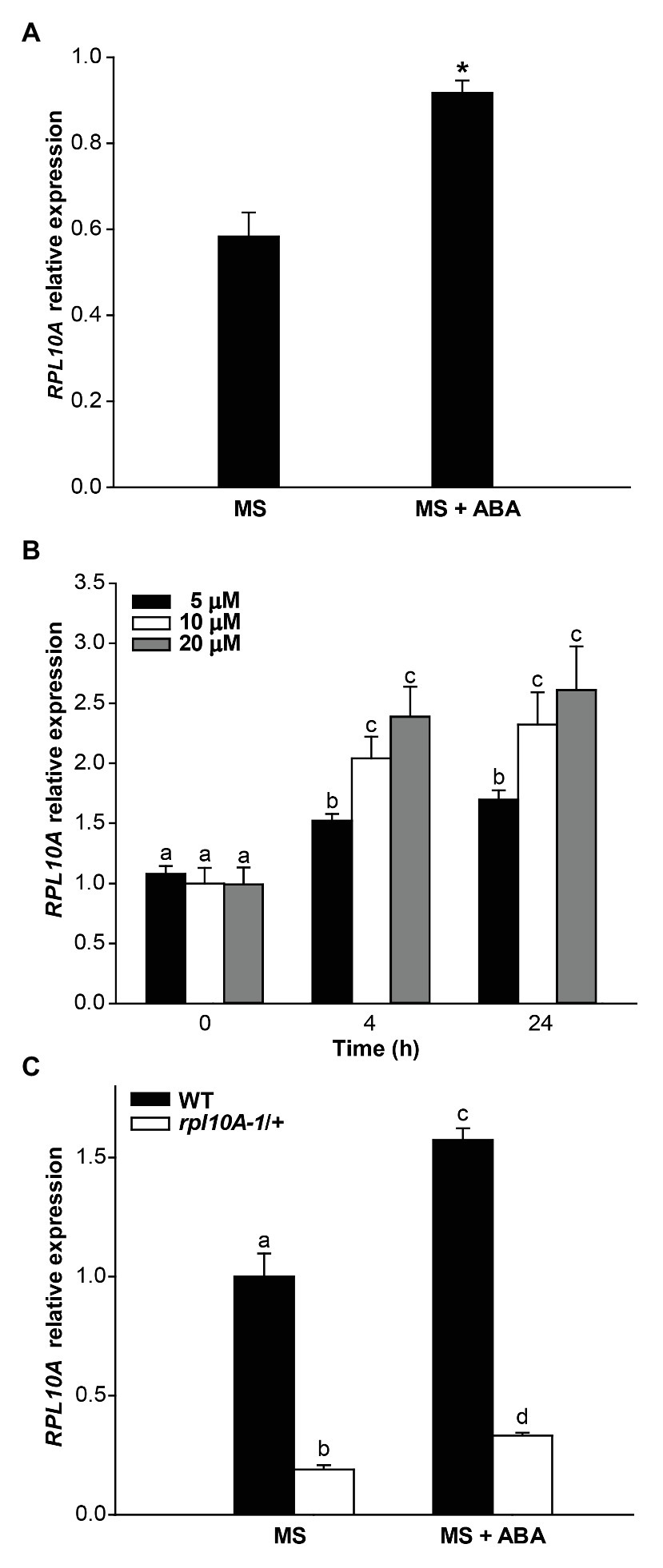

To analyze whether RPL10A is involved in ABA responses, we determined the regulation of RPL10A expression by ABA treatment by RT-qPCR. Figure 2A shows that, at cotyledon greening stage (seedlings with fully open and green cotyledons), RPL10A expression is induced 1.6-fold by 1 μM ABA. This induction is observed as early as 4 h after the exposure of 14-day-old seedlings to 5, 10, and 20 μM ABA (Figure 2B). No differences in RPL10A transcript levels were observed between 10 and 20 μM ABA at 4 h or 24 h after treatment. To discard that other RPL10 family genes can also be implicated in ABA responses, the expression of RPL10B and RPL10C genes was also analyzed by RT-qPCR. Transcript levels of both RPL10B and RPL10C were not modified by ABA treatment (Supplementary Figure S2A).

Figure 2. Regulation of the RPL10A expression by ABA. (A) RPL10A transcript levels in WT seedlings, at cotyledon greening stage, grown in MS-agar medium (MS) or in MS-agar medium with 1 μM ABA (MS + ABA), analyzed by RT-qPCR. Asterisks indicate statistical differences between conditions (Student’s t-test, p < 0.05). (B) RPL10A transcript accumulation in WT seedlings after ABA treatment (5, 10, and 20 μM) for 4 and 24 h. Values are expressed relative to the control set as 1. ACTIN2 transcript accumulation was used as a reference. Results represent the average ± SE of three biological replicates. Different letters over the bar indicate statistical differences between samples applying ANOVA test (p < 0.05). (C) RPL10A transcript levels in WT and rpl10A/+ mutant seedlings, at cotyledon greening stage, grown in MS-agar medium (MS) or in MS-agar medium with 1 μM ABA (MS + ABA). Values are expressed relative to the WT seedlings in MS-agar medium (MS) set as 1. ACTIN2 transcript accumulation was used as a reference. Results represent the average ± SE of three biological replicates. Different letters over the bar indicate statistical differences between samples applying ANOVA test (p < 0.05).

The induction of RPL10A expression by ABA was also examined using transgenic RPL10Apro:GUS plants. GUS activity was evaluated at germinated seed stage. Because ABA delays seed germination (Finkelstein et al., 2002; Yoshida et al., 2019), GUS activity was determined at 22 or 46 h after stratification in the absence (Figure 1A) or presence of 1 μM ABA (Figure 1H), respectively. Results show an increased GUS staining in the presence of ABA. GUS activity was also assessed at cotyledon greening stage. This stage was reached 4 and 8 days after stratification in the absence and presence of ABA, respectively. Although no appreciable differences in the GUS signal could be detected in the cotyledons of seedlings grown in the presence of ABA with respect to what was observed in its absence (Figure 1C), GUS staining markedly increased in the primary root by ABA (Figure 1I).

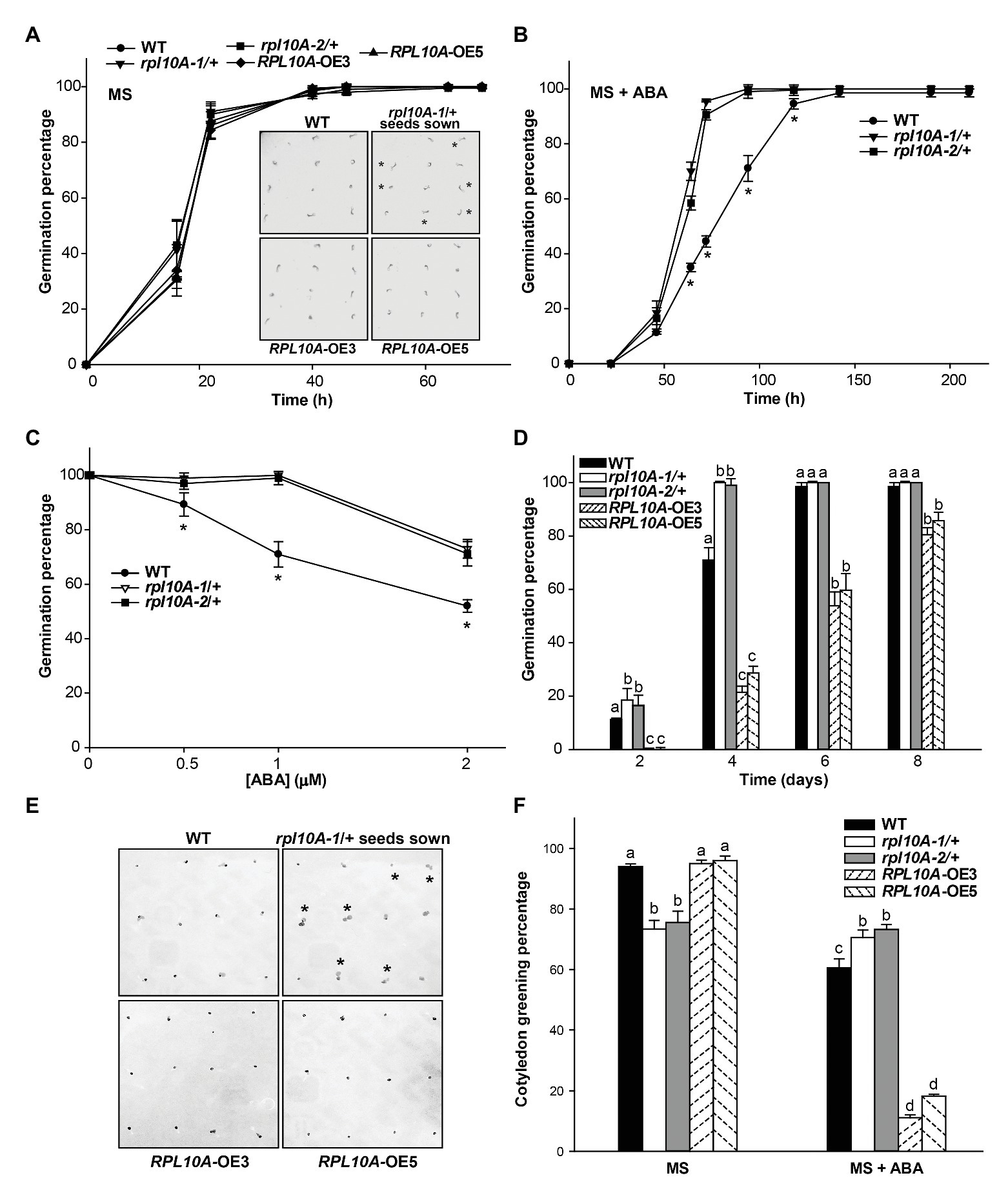

Germination of heterozygous rpl10A mutant (designed as rpl10A-1/+ and rpl10A-2/+; Falcone Ferreyra et al., 2010a) and WT seeds was evaluated in MS-agar plates by scoring the radicle emergence. Fresh rpl10A-1A+ and rpl10A-2/+ mutant seeds showed a similar germination rate compared with WT seeds, reaching a maximum at 40 h after stratification (Figure 3A). However, in the presence of 1 μM ABA, rpl10A/+ seeds showed an increased germination rate compared to WT seeds (Figure 3B). When percentage of inhibition of seed germination by ABA was compared between genotypes, rpl10A/+ seeds exhibited lower values than WT seeds (Supplementary Figure S3A). The earlier germination pattern in rpl10A/+ plants was also observed at 0.5 and 2 μM ABA (Figure 3C and Supplementary Figures S3B,C). To validate the role of RPL10A in ABA-mediated seed germination, RPL10A-overexpressing lines (RPL10A-OE3 and RPL10A-OE5) were generated. First, increased RPL10A transcript levels were confirmed by RT-qPCR in RPL10A-overexpressing lines (8.7-fold and 6.5-fold in RPL10A-OE3 and RPL10A-OE5, respectively, compared with those in WT plants; Supplementary Figure S2B). In addition, the expression of RPL10B and RPL10C genes was also analyzed in RPL10A-OE lines, and their transcript levels were similar to those in WT seedlings (Supplementary Figure S2B). Germination of RPL10A-OE lines was further analyzed. Germination of RPL10A-OE lines was similar to that of WT seeds in the absence of ABA (Figure 3A and inset). However, in the presence of exogenous applied ABA (1 μM), RPL10A-OE3 and RPL10A-OE5 lines were more sensitive to ABA than WT seeds, showing significantly reduced germination rates compared to WT seeds at 4 days after stratification (Figures 3D,E). These results suggest that RPL10A is required for the inhibition of seed germination by ABA.

Figure 3. Effect of exogenous ABA on germination and cotyledon greening of rpl10A/+ mutant and RPL10A-overexpressing seeds. (A) Germination percentage of wild type (WT), rpl10A-1/+, rpl10A-2/+, and RPL10A-overexpressing OE3 and OE5 seeds on MS-agar medium (MS). Inset: representative images of seedlings from all genotypes 1 day after stratification. Heterozygous rpl10A-1 mutant seedlings are indicated with asterisks. (B) Germination percentage of WT and rpl10A-1/+ and rpl10A-2/+ seeds on MS-agar medium supplemented with 1 μM ABA (MS + ABA). Asterisks indicate statistical differences between WT and each mutant at each time applying Student’s t-test (p < 0.05). (C) ABA concentration-dependent germination assay. rpl10A-1/+, rpl10A-2/+, and WT seeds were germinated on MS-agar medium supplemented with increasing concentration of ABA and the germination percentages were scored at 4 days after stratification. Results represent the average of three independent experiments ± SE (n = 100 for each biological replicate). Asterisks indicate statistical differences between WT and each mutant at each time applying Student’s t-test (p < 0.05). (D) Germination percentage of WT, rpl10A/+ mutants (rpl10A-1/+ and rpl10A-2/+), and RPL10A-overexpressing seeds (RPL10A-OE3 and RPL10A-OE5) on MS-agar medium supplemented with 1 μM ABA at 2, 4, 6, and 8 days after stratification. Results represent the average of three independent experiments ± SE (n = 100 for each biological replicate). Different letters over the bars indicate statistical differences between genotypes at each time using ANOVA test (p < 0.05). (E) Representative images of WT, rpl10A-1/+ mutants, and RPL10A-overexpressing lines (RPL10A-OE3 and RPL10A-OE5) grown on MS-agar medium supplemented with 1 μM ABA (MS + ABA), at 4 days after stratification. Heterozygous rpl10A-1 mutant seedlings are indicated with asterisks. (F) Cotyledon greening percentage of WT, rpl10A/+ mutants (rpl10A-1/+ and rpl10A-2/+), and RPL10A-overexpressing lines (RPL10A-OE3 and RPL10A-OE5) grown on MS-agar medium (MS) or on MS-agar medium supplemented with 1 μM ABA (MS + ABA), at 8 days after stratification. Results are the mean of three independent experiments ± SE. For each genotype and condition (MS or MS + ABA), different letters over the bars indicate statistical differences applying ANOVA test (p < 0.05).

Then, we investigated ABA sensitivity of rpl10A/+ mutants and transgenic RPL10A overexpressing lines during early plant development. The addition of exogenous ABA decreased the cotyledon greening percentage to 60, 11, and 18% of the untreated control in WT, RPL10A-OE3, and RPL10A-OE5 lines, respectively (Figure 3F). Supplementary Figure S4A shows representative images of seedlings from WT, mutant, and overexpressing genotypes at 4 and 8 days after stratification in the absence and presence of ABA, respectively. It should be mentioned that under control conditions rpl10A-1/+ and rpl10A-2/+ mutant plants only exhibited 73 and 75% cotyledon greening at 8 days after stratification, respectively; whereas RPL10A-OE3 and RPL10A-OE5 lines showed maximum and similar percentages (about 98%) to those observed in WT plants (Figure 3F). However, rpl10A/+ mutant plants did not show a decrease in cotyledon greening percentage in response to ABA treatment respect to the control condition, exhibiting similar percentages under both growth conditions (Figure 3F). Thus, we also investigated seedling establishment of rpl10A/+ mutants after cotyledon greening stage. Consistently, rpl10A/+ seeds showed a deficient juvenile vegetative development (68 and 71% for rpl10A-1/+ and rpl10A-2/+, respectively) compared to WT seeds (94%) at 12 days after stratification in MS-agar control medium (Supplementary Figures S4B,C). Several mutant seedlings arrested their growth before the emergence or expansion of true leaves and died, suggesting that RPL10A is necessary for this developmental stage. In contrast, transgenic RPL10A-overexpressing lines showed no differences in seedling development with respect to WT.

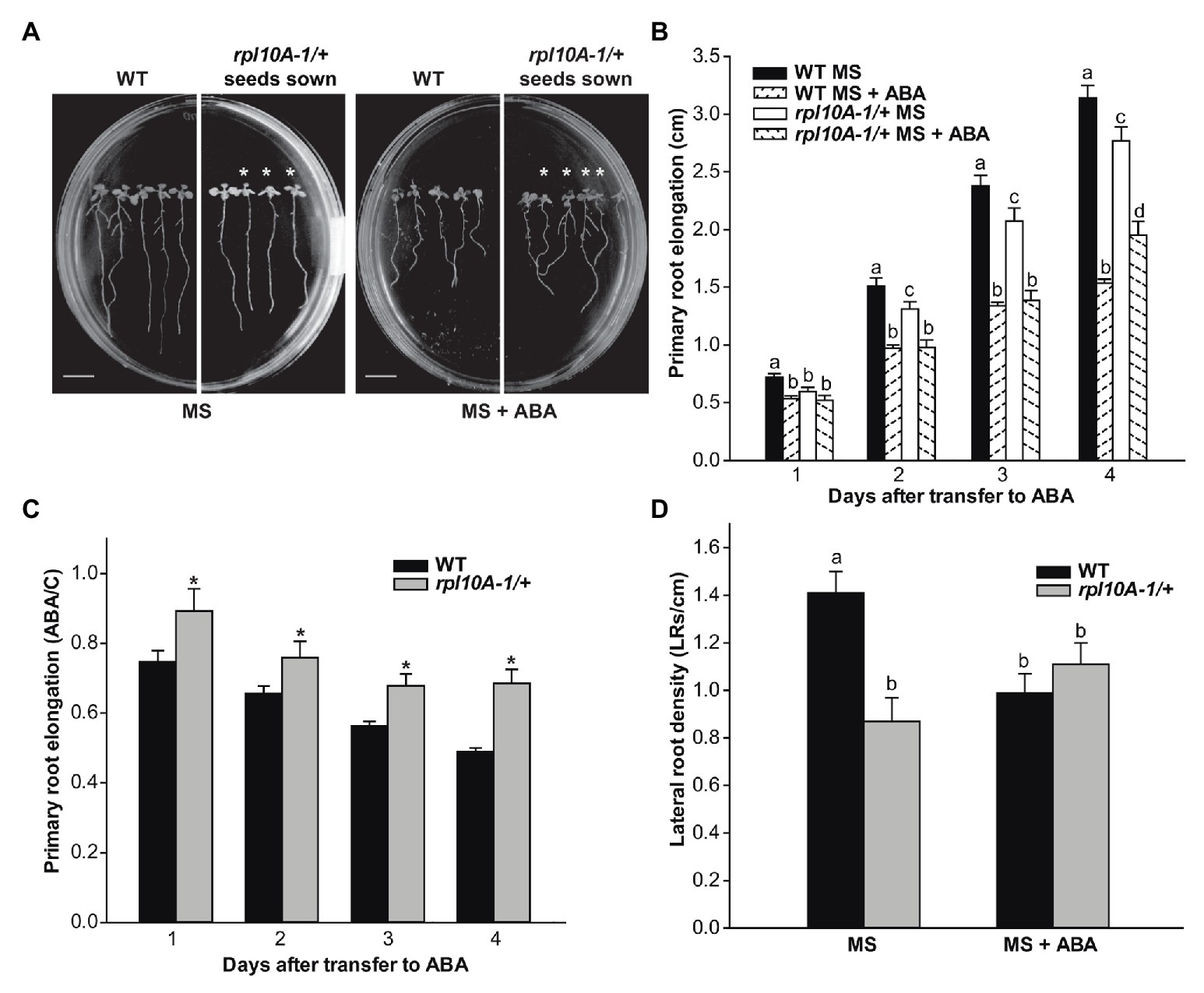

Root growth in response to ABA was also evaluated. Five-day-old WT and rpl10A-1/+ mutant seedlings were transferred from MS-agar control medium to new plates, either containing MS medium supplemented or not with 10 μM ABA. Figure 4A shows representative images of seedlings from both genotypes 4 days after treatment. In the absence of ABA, rpl10A-1/+ mutants showed shorter primary roots and a lower number of LRs per root length unit (LRs density) than WT plants (Figures 4B–D). In the presence of ABA, both WT and rpl10A-1/+ mutants showed primary root elongation inhibition, but the inhibition by ABA was lower in rpl10A-1/+ mutants than in WT plants at 4 days after the transfer (Figures 4B,C), demonstrating that rpl10A-1/+ plants show a lower sensitivity to ABA than WT plants. Accordingly, rpl10A-1/+ mutants displayed no inhibition of LR development in response to exogenous ABA (Figure 4D), while the LRs density was decreased in WT plants (Figure 4D).

Figure 4. ABA inhibition of primary root elongation and lateral root development of WT and rpl10A/+ mutant seedlings. (A) Representative images of WT and rpl10A-1/+ mutant seedlings grown on MS-agar plates and transferred to MS-agar medium (MS) or MS-agar medium supplemented with 10 μM ABA (MS + ABA) 4 days after the transfer. Heterozygous rpl10A-1 mutant seedlings are indicated with asterisks. Bars = 1 cm. (B) Primary root elongation of WT and rpl10A-1/+ mutant seedlings measured each day after the transfer to MS-agar medium (MS) or MS-agar medium supplemented with 10 μM ABA (MS + ABA). Results are the mean of three independent experiments (n = 20 for each biological experiment). For each genotype and condition (MS or MS + ABA), different letters over the bars indicate statistical differences applying ANOVA test (p < 0.05). (C) Average root length after the transfer to ABA treatment relative to control conditions (ABA/C). Asterisks indicate statistical differences between genotype at each day (Student’s t-test, p < 0.05). (D) LR density estimated as the number of LRs per root length unit of WT and rpl10A-1/+ mutants. The number of LRs was determined 4 days after the transfer of 5-day-old seedlings to plates supplemented or not with ABA. Results are the mean of three independent experiments ± SE (n = 20 for each biological experiment). For each genotype and condition (MS or MS + ABA), different letters over the bars indicate statistical differences applying ANOVA test (p < 0.05).

Primary root elongation was also investigated in RPL10A-OE plants. Under control conditions, RPL10A-OE lines had longer primary roots with more LRs per root length unit than WT plants (Supplementary Figures S5A–D). However, primary root elongation and LR development were inhibited to the same extent by ABA treatment in overexpressing and WT plants (Supplementary Figures S5C,E), suggesting that a threshold RPL10A level seems to be enough for its root elongation function.

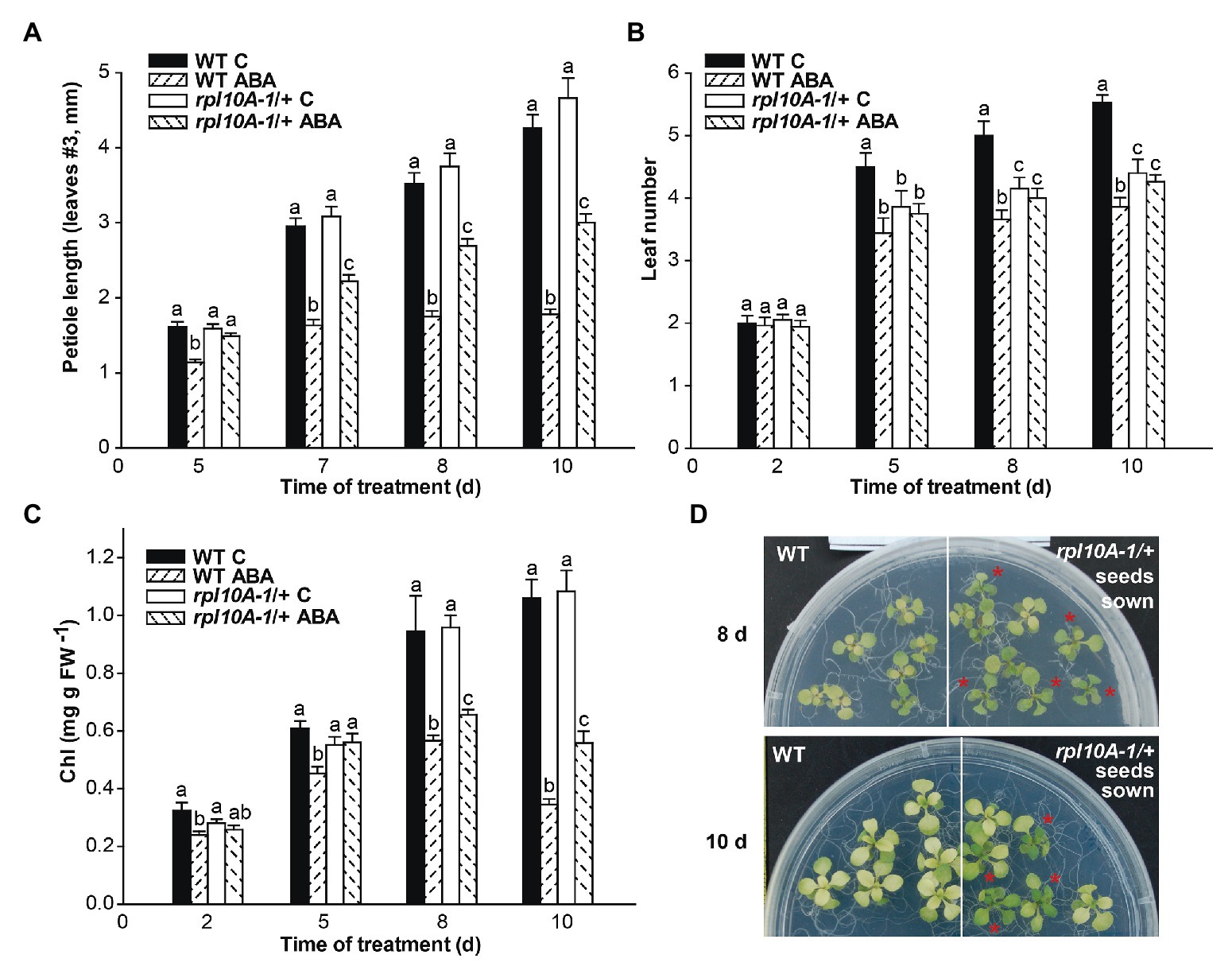

We also determined the effect of ABA on petiole length, leaf number, and yellowing (Figure 5). WT plants treated with ABA (10 μM) were found to have shorter petioles of leaf #3 (Figure 5A), fewer developed leaves (Figure 5B), and increased leaf yellowing as determined by the amount of total chlorophyll (Figure 5C) compared with the control analyzed over the time of the treatment after the transfer to MS-agar medium supplemented with ABA. Notably, rpl10A-1/+ mutants exhibited less ABA sensitivity than WT plants, showing a lower reduction of petiole length (Figure 5A) and yellowing (Figure 5C) than WT plants, while the leaf number was not modified by ABA treatment (Figure 5B). Figure 5D shows representative images of plants from both genotypes at 8 days (upper panel) and at 10 days (lower panel) after the transfer. Similar results were observed when the treatment was carried out with 5 μM ABA (Supplementary Figure S6).

Figure 5. ABA sensitivity time course of rpl10A/+ seedlings. Seven-day-old seedlings grown in MS-agar medium were transferred to MS-agar (MS) or MS-agar medium supplemented with 10 μM ABA (MS + ABA). Petiole length (A), leaf number (B), and chlorophyll (Chl) content per mg fresh weight−1 (FW; C) were measured over the time for 10 days. (D) Representative images of WT and rpl10A-1/+ mutant plants at 8 days (upper panel) and 10 days after the transfer to MS-agar medium supplemented with 10 μM ABA (lower panel). Asterisks indicate heterozygous rpl10A-1 mutant seedlings. Results are the mean of three independent experiments ± SE (n = 30 for each biological experiment). For each genotype and condition (with or without 10 μM ABA), different letters indicate statistical differences applying ANOVA test at p < 0.05.

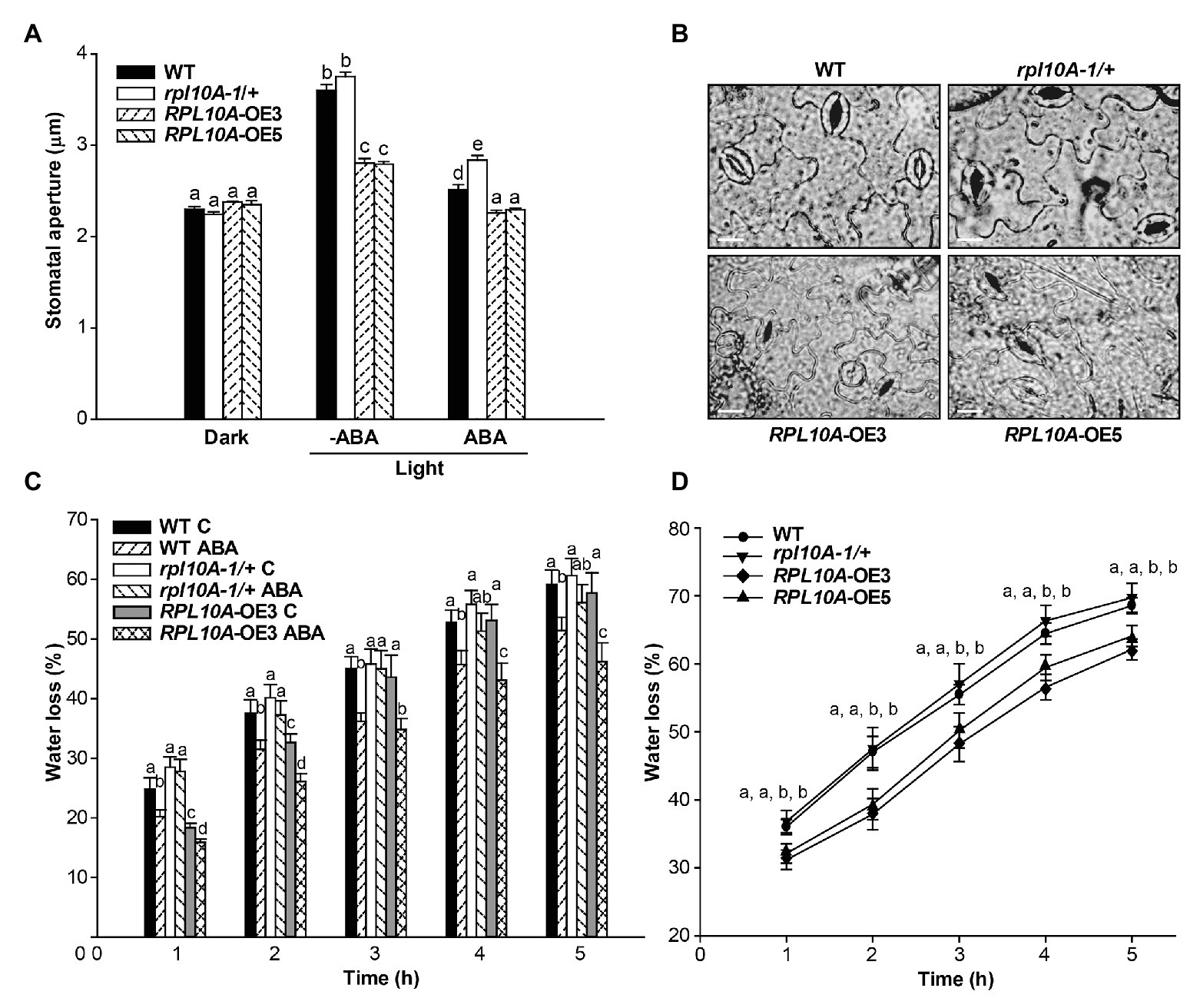

Public microarray data show that RPL10A transcript levels increased 1.3-fold and 1.4-fold in guard and mesophyll cells exposed to ABA, respectively (Supplementary Figure S1D; Winter et al., 2007), and here we show that RPL10A is expressed in stomatal cells (Figure 1G). To investigate if ABA-mediated stomatal movement is affected in rpl10A mutant and RPL10A-overexpressing plants, stomata were induced to open under white light in the presence and absence of 20 μM ABA. No differences in stomatal apertures in dark-adapted leaves in the absence of ABA were observed between genotypes. In illuminated leaves, WT and rpl10A/+ mutant plants did not show differences in stomatal apertures, but RPL10A-overexpressing plants showed less stomatal opening compared to WT plants. ABA treatment caused a decrease of stomatal opening in all plants, but rpl10A-1/+ mutants were less responsive to ABA-promoted stomatal closure than WT plants, while RPL10A-OE lines exhibited the most decrease in this parameter (Figure 6A). Figure 6B shows representative images of stomata from abaxial epidermis of leaf #5 from all genotypes treated with 20 μM ABA. We also evaluated the kinetics of water loss. Treatment with 20 μM ABA leads rpl10A-1/+ mutants to lose water faster than WT plants (Figure 6C), probably due to their less sensitivity to ABA-induced stomatal closure, suggesting that RPL10A could be a player in the regulation of guard cell ABA signaling. On the contrary, leaves #5 of RPL10A-OE3 line showed less water loss than WT plants, both under control conditions and after ABA treatment (Figure 6C). In 3-week-old whole rosettes maintained under control conditions, similar results were observed for RPL10A-OE3 and RPL10A-OE5 lines, while rpl10A-1/+ mutants showed similar water loss to WT plants without ABA treatment (Figure 6D).

Figure 6. Effect of ABA on stomatal aperture and water loss. (A) Stomatal aperture was measured on epidermal peels of leaves #5 from WT, rpl10A-1/+ mutants, and RPL10A-overexpressing lines (RPL10A-OE3 and RPL10A-OE5) plants after 2 h in the dark and subsequent incubation without (−ABA) or with 20 μM ABA (+ABA) under white light for 2 additional hour. Results are the mean of three independent experiments ± SE For each experiment, at least three leaves from three different plants were used and 60 stomata were analyzed. For each genotype and condition (dark and light with or without 20 μM ABA), different letters over the bars indicate significant differences applying ANOVA test at p < 0.05. (B) Representative images of abaxial epidermis peeled from leaves #5 of 3-week-old WT, rpl10A-1/+ mutants, and RPL10A-overexpressing lines (RPL10A-OE3 and RPL10A-OE5) plants incubated with 20 μM ABA under white light for 2 h. Bar = 10 μm. (C) Water loss of air-dried leaves #5 from 3-week-old WT, rpl10A/+ mutant and RPL10A-OE3 plants after petiole-feeding with 20 μM ABA or water (Control, C) for 1 h under white light. Fresh weight was measured every hour and data were normalized to the initial fresh weight. Results represent the average of three independent experiments ± SE, n = 10 for each biological replicate. At each time, for each genotype and condition (with or without 20 μM ABA), different letters over the bars indicate statistical differences applying ANOVA test (p < 0.05). (D) Water loss of air-dried rosettes from 3-week-old WT, rpl10A-1/+ mutant, and RPL10A-overexpressing plants (RPL10A-OE3 and RPL10A-OE5) maintained under control conditions. Fresh weight was measured every hour and data were normalized to the initial fresh weight. Results represent the average of three independent experiments ± SE, n = 10 for each biological replicate. Different letters indicate statistical differences between genotypes at each time applying ANOVA test at p < 0.05.

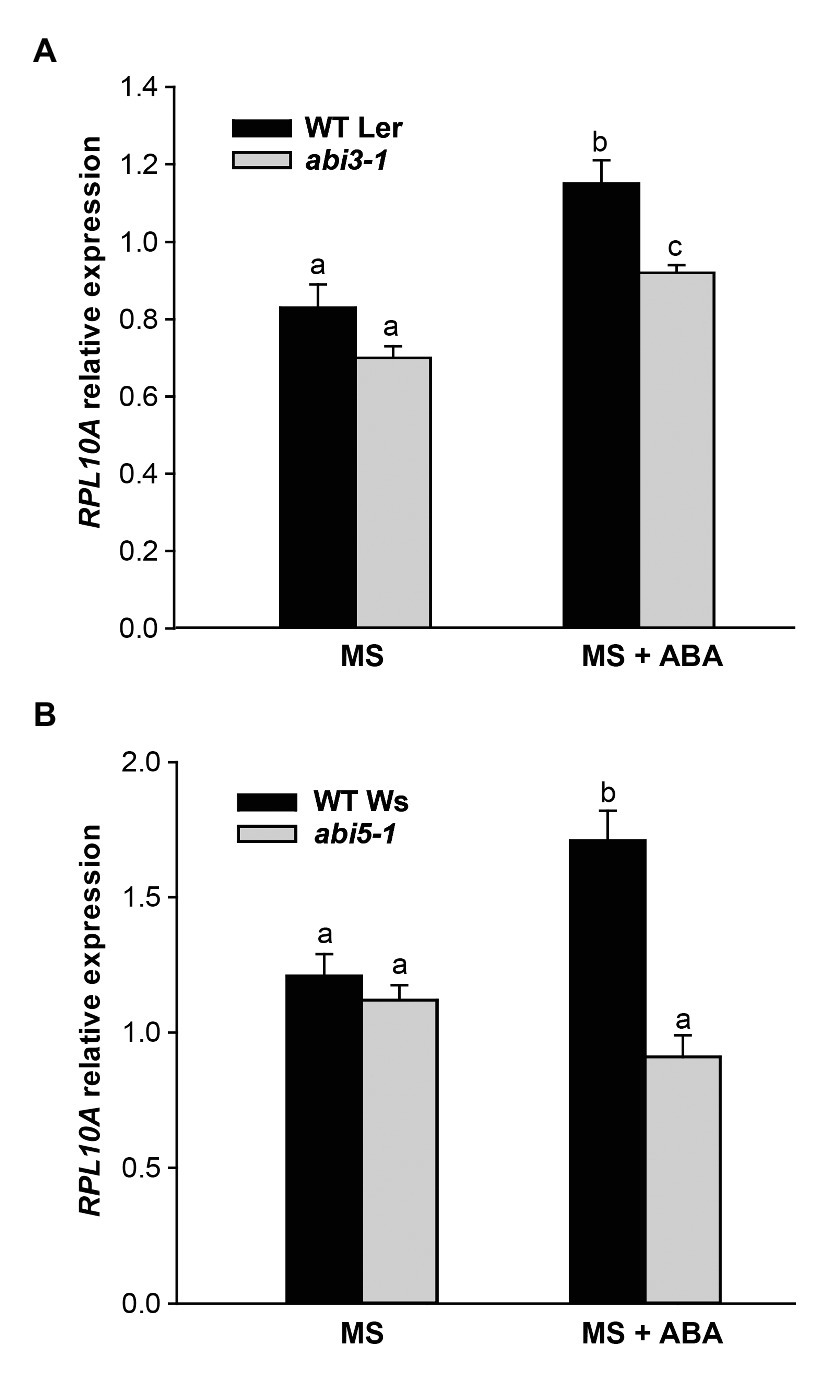

Next, we investigated whether the induction of RPL10A by ABA depended on ABI3 and ABI5 transcription factors. Figures 7A,B show that RPL10A transcript levels did not increase in abi3 and abi5 mutants as in WT seedlings. In the absence of ABA, RPL10A expression was similar in all genotypes.

Figure 7. RPL10A expression analysis in abi3 and abi5 mutant plants. RPL10A transcript levels in abi3-1 (A) and abi5-1 (B) mutant plants and their respective WT background plants (Ler and Ws, respectively) grown in MS-agar medium without (MS) or with 1 μM ABA supplementation (MS + ABA). ACTIN2 transcript accumulation was used as a reference. Results represent the average ± SE of three biological replicates. Different letters over the bar indicate statistical differences between samples applying ANOVA test (p < 0.05).

We further analyzed if a decreased sensitivity to ABA of rpl10A/+ mutants could be related to an altered expression of RPL10 genes. Fourteen-day-old WT seedlings and rpl10A-1/+ mutants previously grown in MS-agar plates were transferred to liquid MS medium with or without ABA supplementation and further incubated under light conditions for 4 h. In rpl10A-1/+ heterozygous mutant plants, the induction of RPL10A expression by ABA was similar to the one observed in WT plants, but transcript levels of mutant plants were significantly lower than those in WT plants after treatment (Supplementary Figure S2A). Moreover, to confirm the absence of functional compensation in the RPL10 family by variations in their transcript levels, the expression of RPL10B and RPL10C genes was analyzed by RT-qPCR in rpl10A-1/+ mutants treated with ABA. Transcript levels of RPL10B and RPL10C were similar in seedlings under control and ABA condition (Supplementary Figure S2A). In addition, at cotyledon greening stage (seedlings with fully open and green cotyledons), RPL10A expression is induced in rpl10A-1/+ mutants (1.7-fold) as in WT plants (1.6-fold) by 1 μM ABA (Figure 2C). Thus, both the regulation of RPL10A expression by ABA and the expression of other RPL10 family members are not altered in rpl10A/+ mutant plants.

Many studies have shown that distinct paralogous family members of ribosomal proteins could play a role in different developmental stages/tissues, under specific stress conditions (Byrne, 2009; Horiguchi et al., 2012; Hummel et al., 2012; Carroll, 2013), or in response to hormones (Byrne, 2009; Rosado et al., 2012). Besides their roles in translation, ribosomal proteins have also been reported to have extra-ribosomal functions. Recently, an extra-ribosomal function in miRNA biogenesis was attributed to A. thaliana RPL24B (Li et al., 2017). Previously, RPL10A was demonstrated to be essential for plant viability and also to play roles in abiotic and biotic stress responses in A. thaliana and rice (Falcone Ferreyra et al., 2010a,b, 2013; Zorzatto et al., 2015; Moin et al., 2016a). Under some of these stresses, the protein could be detected both in cytosol and nuclei, thus suggesting extra-ribosomal functions (Falcone Ferreyra et al., 2013). In addition, ribosomal proteins have been involved in modulating gene expression (Merchante et al., 2017; Calamita et al., 2018; Genuth and Barna, 2018). Specifically, RPL10A was reported to regulate gene expression both at a transcriptional level, acting as a transcriptional repressor, and at a translational level, as a component of the 80S ribosome (Falcone Ferreyra et al., 2010a; Zorzatto et al., 2015). One demonstrated step that regulates gene expression is the upstream open reading frame (uORF)-mediated translational control (Merchante et al., 2017). In fact, RPL10A has been demonstrated to control uORF-mediated translation (Imai et al., 2008). In this work, we extend these studies by analyzing the additional roles of RPL10A in A. thaliana.

We first analyzed the spatial and temporal expression of RPL10A. The gene exhibits a ubiquitous expression pattern throughout the plant, but it is most strongly expressed in undifferentiated tissues with active division, in primary and LRs, both at emergency and at outgrowth stages and in elongated LRs (Figure 1). Notably, gene expression was also detected in stomatal cells (Figure 1). These data are supported by microarray data of different Arabidopsis tissues (Supplementary Figure S1). Supplementary Figure S1 shows high RPL10A transcript levels in all types of cells, being the highest in the shoot apical meristem, but high levels of expression are also present in roots and cotyledons.

We then examined the role of RPL10A during early plant development and ABA response using Arabidopsis rpl10A heterozygous mutants and RPL10A-overexpressing lines. Under control conditions, no differences during seed germination (Figure 3A) were observed between genotypes. However, rpl10A/+ mutants showed reduced cotyledon greening (Figure 3F) and decreased early seedling development (Supplementary Figure S4) compared to WT plants. In addition, rpl10A/+ mutant seedlings showed defects in root growth, with shorter primary roots and impaired LR formation compared to WT seedlings (Figure 4). In contrast, although RPL10A-overexpressing lines did not exhibit differences in cotyledon greening and seedling development respect to WT plants, they showed longer primary roots with higher LRs density than WT plants (Figure 3; Supplementary Figures S4, S5). These results may indicate that a RPL10A threshold level may be necessary for plant development specially during the early stages when active cell division occurs, possibly attributed to its key function to form mature 80S ribosomes during protein synthesis, as it was previously reported for this protein and other Arabidopsis ribosomal proteins (Degenhardt and Bonham-Smith, 2008; Byrne, 2009; Falcone Ferreyra et al., 2010a). Accordingly, public RNA-Seq data of Arabidopsis WT cells after light exposition over time show an increase in RPL10A transcript levels (Petryszak et al., 2016) supporting the RPL10A involvement in seed-to-seedling transition. Additionally, protein-protein interaction networks constructed using AraPPINet (http://netbio.sjtu.edu.cn/arappinet/; Zhang et al., 2016) show that a large group of possible protein interactors with RPL10A are involved in photomorphogenesis and plant growth and development. These findings indicate that RPL10A may also have roles in these physiological processes and, consequently, it could explain the growth arrest of germinated seeds in rpl10A/+ mutants.

ABA was reported to negatively regulate seed germination and plant development (Finkelstein et al., 2002; Yoshida et al., 2019) and to control primary and LR development (Santos Teixeira and ten Tusscher, 2019). It was also demonstrated that ribosomal proteins can play roles in ABA responses through their participation in protein translation (Wang et al., 2011). Consequently, we investigated if RPL10A is involved in ABA response during seed germination and seedling development. First, we observed that RPL10A expression is induced by ABA (Figures 1H,I, 2A,B). This result is in accordance with previous reported data (Supplementary Figure S1D; Petryszak et al., 2016). We also showed that in the presence of exogenous ABA, rpl10A/+ seeds germinated earlier than WT seeds, while the opposite was observed in RPL10A-OE lines (Figures 3B–E). rpl10A/+ mutants also showed less ABA-inhibition of cotyledon greening, primary root elongation, LR formation, petiole length, leaf number, and chlorophyll content compared to WT seedlings (Figures 3–5). Similarly, Arabidopsis mutant plants in RACK1A, a protein with many different functions, which include translation, development, ABA-signaling, and auxin-signaling, showed insensitivity to LR development inhibition by salinity, an abiotic stress that involved ABA action (Denver and Ullah, 2019). Thus, based on these data and the phenotypes observed in this work, RPL10A seems to be a positive regulator of ABA responses.

Because ABA inhibits stomatal opening under light conditions (Kim et al., 2010; Assmann and Jegla, 2016), we also investigated the RPL10A role in stomatal aperture. Both leaves #5 and detached rosettes of RPL10A-overexpressing lines lost significantly less water than WT in correlation with a high stomatal closure observed under light condition both with and without ABA treatment (Figure 6). On the contrary, rpl10A/+ mutant plants did not exhibit differences with respect to WT in water loss of both leaf #5 and detached rosettes under control condition but showed a decreased ABA sensitivity in guard cells, with a higher stomatal aperture under light conditions and an increased water loss after the treatment (Figure 6). These results are consistent with the in vivo localization of RPL10A in guard cells (Figure 1G). Even more, protein-protein interaction networks predict that RPL10A interacts with proteins that regulate the stomatal closure, such as ATH-BTB domain proteins (BPMs) and the negative regulator of ABA response, the class I homeobox-leucine zipper (HD-ZIP) transcription factor ATHB6 (Lechner et al., 2011). Consequently, the involvement of RPL10A in these physiological processes in response to ABA could be mediated through its interaction with these and other proteins involved in stomatal movement. In fact, previous co-immunoprecipitation studies showed that RPL10A interacts with TGG1 and TGG2 myrosinases, both proteins involved in ABA signaling in guard cells (Islam et al., 2009; Falcone Ferreyra et al., 2010a,b).

To investigate a link between RPL10A and ABA-dependent responses, we analyzed RPL10A induction by ABA. This induction is lower or does not take place in abi3-1 and abi5-1 mutants, respectively (Figures 7A,B), suggesting that RPL10A expression might be regulated by ABI3 and ABI5 transcription factors. In silico analysis of RPL10A promoter show the presence of cis-regulatory elements associated with hormone regulation, stress, and development (Supplementary Figure S7). For example, G-box elements, involved in ABA responses, binding sites for bZIP transcription factors (TFs) such as ABI5 (Finkelstein and Lynch, 2000) and RY elements for B3-type TFs such as ABI3, among others are predicted in the RPL10A promoter. ABA signaling also involves diverse types of transcription factors, such as NACs, MYCs, MYBs, ERFs (ethylene response factors), and WRKYs (Liu et al., 2012; Sah et al., 2016), some of which were also predicted in the RPL10A promoter. It is then possible that RPL10A regulation by ABA can involve multiple TFs and more than one signaling pathway.

Taken together, these results indicate that RPL10A could play roles in ABA-dependent responses at one or more different levels. One possibility is that nuclear RPL10A can transcriptionally regulate the expression of genes involved in ABA signaling and/or be involved in the post-transcriptional regulation through its binding to RNA or RNA-binding proteins. Accordingly, RPL10A co-immunoprecipitated proteins involved in mRNA stability such as the glycine-rich protein GRP7 (Falcone Ferreyra et al., 2010a) and protein-protein interaction networks predict that RPL10A can interact with a RNA-binding proteins proposed to be involved in exon junction and in RNA processing. In addition, RPL10A may have a precise role in protein synthesis of key components of ABA responses. This hypothesis, focus of future studies, agrees with our data showing that RPL10A is induced by ABA and with previous reports indicating that this gene is translational regulated and that a reconfiguration of translatomes by different stress can occur to facilitate acclimation (Mustroph et al., 2009; Falcone Ferreyra et al., 2010a). Our results deserve further analysis by RNA-seq technology to provide insights about WT, mutant, and transgenic plant response to ABA treatment and to characterize regulatory gene networks. Future work is needed to investigate how RPL10A is involved in ABA signaling.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

MLFF designed the study. RR performed the experiments. MLFF, RR, CS, and PC analyzed and interpreted the data. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript and approved the final version.

This research was supported by Fondo para la Investigación Científica y Tecnológica (FONCyT) grants PICT 2018‐01998 to MLFF, and PICT 2016‐141 and PICT 2015‐157 to PC. MLFF, CS, and PC are members of the Researcher Career of the Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET) and are Professors at the Universidad Nacional de Rosario (UNR). RR is a doctoral fellow from ANPCyT.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We thank María José Maymó for cultivating Arabidopsis plants.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2020.582353/full#supplementary-material

Assmann, S. M., and Jegla, T. (2016). Guard cell sensory systems: recent insights on stomatal responses to light, abscisic acid, and CO2. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 33, 157–167. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2016.07.003

Basbouss-Serhal, I., Soubigou-Taconnat, L., Bailly, C., and Leymarie, J. (2015). Germination potential of dormant and nondormant Arabidopsis seeds is driven by distinct recruitment of messenger RNAs to polysomes. Plant Physiol. 168, 1049–1065. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.00510

Byrne, M. E. (2009). A role for the ribosome in development. Trends Plant Sci. 14, 512–519. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2009.06.009

Calamita, P., Gatti, G., Miluzio, A., Scagliola, A., and Biffo, S. (2018). Translating the game: ribosomes as active players. Front. Genet. 9:533. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2018.00533

Carroll, A. J. (2013). The Arabidopsis cytosolic ribosomal proteome: from form to function. Front. Plant Sci. 4:32. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00032

Cherepneva, G. N., Schmidt, K. H., Kulaeva, O. N., Oelmüller, R., and Kusnetsov, V. V. (2003). Expression of the ribosomal proteins S14, S16, L13a and L30 is regulated by cytokinin and abscisic acid: implication of the involvement of phytohormones in translational processes. Plant Sci. 165, 925–932. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9452(03)00204-8

Clough, S. J., and Bent, A. F. (1998). Floral dip: a simplified method for agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 16, 735–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1998.00343.x

Degenhardt, R. F., and Bonham-Smith, P. C. (2008). Arabidopsis ribosomal proteins RPL23aA and RPL23aB are differentially targeted to the nucleolus and are disparately required for normal development. Plant Physiol. 147, 128–142. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.111799

Denver, J. B., and Ullah, H. (2019). miR393s regulate salt stress response pathway in Arabidopsis thaliana through scaffold protein RACK1A mediated ABA signaling pathways. Plant Signal. Behav. 14, 1–7. doi: 10.1080/15592324.2019.1600394

Di Rienzo, J. A., Casanoves, F., Balzarini, M. G., Gonzalez, L., Tablada, M., and Robledo, C. V. (2017). InfoStat versión 2017. Grupo InfoStat, FCA, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Argentina.

Falcone Ferreyra, M. L., Biarc, J., Burlingame, A. L., and Casati, P. (2010b). Arabidopsis l10 ribosomal proteins in UV-B responses. Plant Signal. Behav. 5, 1222–1225. doi: 10.4161/psb.5.10.12758

Falcone Ferreyra, M. L., Casadevall, R., Luciani, M. D., Pezza, A., and Casati, P. (2013). New evidence for differential roles of L10 ribosomal proteins from Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 163, 378–391. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.223222

Falcone Ferreyra, M., Pezza, A., Biarc, J., Burlingame, A. L., and Casati, P. (2010a). Plant L10 ribosomal proteins have different roles during development and translation under ultraviolet-B stress. Plant Physiol. 153, 878–1894. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.157057

Finkelstein, R. R., Gampala, S. S. L., and Rock, C. D. (2002). Abscisic acid signaling in seeds and seedlings. Plant Cell 14, 15–46. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010441

Finkelstein, R. R., and Lynch, T. J. (2000). The Arabidopsis abscisic acid response gene ABI5 encodes a basic leucine zipper transcription factor. Plant Cell 12, 599–609. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.4.599

Genuth, N. R., and Barna, M. (2018). The discovery of ribosome heterogeneity and its implications for gene regulation and organismal life. Mol. Cell 71, 364–374. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.07.018

Guo, J., Wang, S., Valerius, O., Hall, H., Zeng, Q., Li, J. F., et al. (2011). Involvement of Arabidopsis RACK1 in protein translation and its regulation by abscisic acid. Plant Physiol. 155, 370–383. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.160663

Hofer, A., Bussiere, C., and Johnson, A. W. (2007). Mutational analysis of the ribosomal protein Rpl10 from yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 32630–32639. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705057200

Horiguchi, G., Van Lijsebettens, M., Candela, H., Micol, J. L., and Tsukaya, H. (2012). Ribosomes and translation in plant developmental control. Plant Sci. 191–192, 24–34. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2012.04.008

Hummel, M., Cordewener, J. H. G., de Groot, J. C. M., Smeekens, S., America, A. H. P., and Hanson, J. (2012). Dynamic protein composition of Arabidopsis thaliana cytosolic ribosomes in response to sucrose feeding as revealed by label free MSE proteomics. Proteomics 12, 1024–1038. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201100413

Imai, A., Komura, M., Kawano, E., Kuwashiro, Y., and Takahashi, T. (2008). A semi-dominant mutation in the ribosomal protein L10 gene suppresses the dwarf phenotype of the acl5 mutant in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 56, 881–890. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03647.x

Islam, M. M., Tani, C., Watanabe-Sugimoto, M., Uraji, M., Jahan, M. S., Masuda, C., et al. (2009). Myrosinases, TGG1 and TGG2, redundantly function in ABA and MeJA signaling in Arabidopsis guard cells. Plant Cell Physiol. 50, 1171–1175. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcp066

Juntawong, P., Girke, T., Bazin, J., and Bailey-Serres, J. (2014). Translational dynamics revealed by genome-wide profiling of ribosome footprints in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 111, E203–E212. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1317811111

Kim, J. Y., Kwak, K. J., Jung, H. J., Lee, H. J., and Kang, H. (2010). MicroRNA402 affects seed germination of Arabidopsis thaliana under stress conditions via targeting DEMETER-LIKE Protein3 mRNA. Plant Cell Physiol. 51, 1079–1083. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcq072

Klepikova, A. V., Kasianov, A. S., Gerasimov, E. S., Logacheva, M. D., and Penin, A. A. (2016). A high resolution map of the Arabidopsis thaliana developmental transcriptome based on RNA-seq profiling. Plant J. 88, 1058–1070. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13312

Lechner, E., Leonhardt, N., Eisler, H., Parmentier, Y., Alioua, M., Jacquet, H., et al. (2011). MATH/BTB CRL3 receptors target the homeodomain-leucine zipper ATHB6 to modulate abscisic acid signaling. Dev. Cell 21, 1116–1128. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.10.018

Li, S., Liua, K., Zhang, S., Wang, X., Rogers, K., Ren, G., et al. (2017). STV1, a ribosomal protein, binds primary microRNA transcripts to promote their interaction with the processing complex in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 114, 1424–1429. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1613069114

Liu, Z. Q., Yan, L., Wu, Z., Mei, C., Lu, K., and Yu, Y. T. (2012). Cooperation of three WRKY-domain transcription factors WRKY18, WRKY40, and WRKY60 in repressing two ABA-responsive genes ABI4 and ABI5 in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 63, 6371–6392. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers293

Merchante, C., Stepanova, A. N., and Alonso, J. M. (2017). Translation regulation in plants: an interesting past, an exciting present and a promising future. Plant J. 90, 628–653. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13520

Moin, M., Bakshi, A., Saha, A., Dutta, M., Madhav, S. M., and Kirti, P. B. (2016a). Rice ribosomal protein large subunit genes and their spatio-temporal and stress regulation. Front. Plant Sci. 7:1284. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01284

Moin, M., Bakshi, A., Saha, A., Udaya Kumar, M., Reddy, A. R., Rao, K. V., et al. (2016b). Activation tagging in indica rice identifies ribosomal proteins as potential targets for manipulation of water-use efficiency and abiotic stress tolerance in plants. Plant Cell Environ. 39, 2440–2459. doi: 10.1111/pce.12796

Mustroph, A., Zanetti, M. E., Jang, C. J. H., Holtan, H. E., Repetti, P. P., Galbraith, D. W., et al. (2009). Profiling translatomes of discrete cell populations resolves altered cellular priorities during hypoxia in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106, 18843–18848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906131106

Narsai, R., Law, S. R., Carrie, C., Xu, L., and Whelan, J. (2011). In-depth temporal transcriptome profiling reveals a crucial developmental switch with roles for RNA processing and organelle metabolism that are essential for germination in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 157, 1342–1362. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.183129

Ng, L. M., Melcher, K., Teh, B. T., and Xu, H. E. (2014). Abscisic acid perception and signaling: structural mechanisms and applications. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 35, 567–584. doi: 10.1038/aps.2014.5

Petryszak, R., Keays, M., Tang, Y. A., Fonseca, N. A., Barrera, E., Burdett, T., et al. (2016). Expression Atlas update—an integrated database of gene and protein expression in humans, animals and plants. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D746–D752. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1045

Rosado, A., Li, R., Van de ven, W., Hsu, E., and Raikhel, N. V. (2012). Arabidopsis ribosomal proteins control developmental programs through translational regulation of auxin response factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109, 19537–19544. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1214774109

Rozen, S., and Skaletsky, H. (2000). Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. Methods Mol. Biol. 132, 365–386.

Sah, S. K., Reddy, K. R., and Li, J. (2016). Abscisic acid and abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Front. Plant Sci. 7:571. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00571

Santos Teixeira, J. A., and ten Tusscher, K. H. (2019). The systems biology of lateral root formation: connecting the dots. Mol. Plant 12, 784–803. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2019.03.015

Shi, C., Wang, Y., Guo, Y., Chen, Y., and Liu, N. (2017). Cooperative down-regulation of ribosomal protein L10 and NF-κB signaling pathway is responsible for the anti-proliferative effects by DMAPT in pancreatic cancer cells. Oncotarget 8, 35009–35018. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16557

Singh, K., Paul, A., Kumar, S., and Ahuja, P. S. (2009). Cloning and differential expression of QM like protein homologue from tea [Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze]. Mol. Biol. Rep. 36, 921–927. doi: 10.1007/s11033-008-9264-x

Sormani, R., Masclaux-Daubresse, C., Daniele-Vedele, F., and Chardon, F. (2011). Transcriptional regulation of ribosome components are determined by stress according to cellular compartments in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS One 6:e28070. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028070

Wang, R. S., Pandey, S., Li, S., Gookin, T. E., Zhao, Z., Albert, R., et al. (2011). Common and unique elements of the ABA-regulated transcriptome of Arabidopsis guard cells. BMC Genomics 12:216. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-216

Winter, D., Vinegar, B., Nahal, H., Ammar, R., Wilson, G. V., and Provart, N. J. (2007). An “electronic fluorescent pictograph” browser for exploring and analyzing large-scale biological data sets. PLoS One 2:e718. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000718

Wintermans, J. F. G. M., and De Mots, A. (1965). Spectrophotometric characteristics of chlorophylls a and b and their phenophytins in ethanol. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 109, 448–453. doi: 10.1016/0926-6585(65)90170-6

Yamasaki, S., Matsuura, H., Demura, T., and Kato, K. (2015). Changes in polysome association of mRNA throughout growth and development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 56, 2169–2180. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcv133

Yoshida, T., Christmann, A., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K., Grill, E., and Fernie, A. (2019). Revisiting the basal role of ABA—roles outside of stress. Trends Plant Sci. 24, 625–635. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2019.04.008

Zhang, F., Liu, S., Li, L., Zuo, K., Zhao, L., and Zhang, L. (2016). Genome-wide inference of protein-protein interaction networks identifies crosstalk in abscisic acid signaling. Plant Physiol. 171, 1511–1522. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.00057

Keywords: seed germination, ABA, early seedling development, rpl10A mutant, RPL10A-overexpressing lines

Citation: Ramos RS, Casati P, Spampinato CP and Falcone Ferreyra ML (2020) Ribosomal Protein RPL10A Contributes to Early Plant Development and Abscisic Acid-Dependent Responses in Arabidopsis . Front. Plant Sci. 11:582353. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.582353

Received: 11 July 2020; Accepted: 01 October 2020;

Published: 05 November 2020.

Edited by:

Taku Takahashi, Okayama University, JapanReviewed by:

Haitao Shi, Hainan University, ChinaCopyright © 2020 Ramos, Casati, Spampinato and Falcone Ferreyra. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: María Lorena Falcone Ferreyra, ZmFsY29uZUBjZWZvYmktY29uaWNldC5nb3YuYXI=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.