- 1College of Horticulture, Northwest A&F University, Shaanxi Engineering Research Center for Vegetables, Yangling, China

- 2Department of Horticulture, The University of Haripur, Haripur, Pakistan

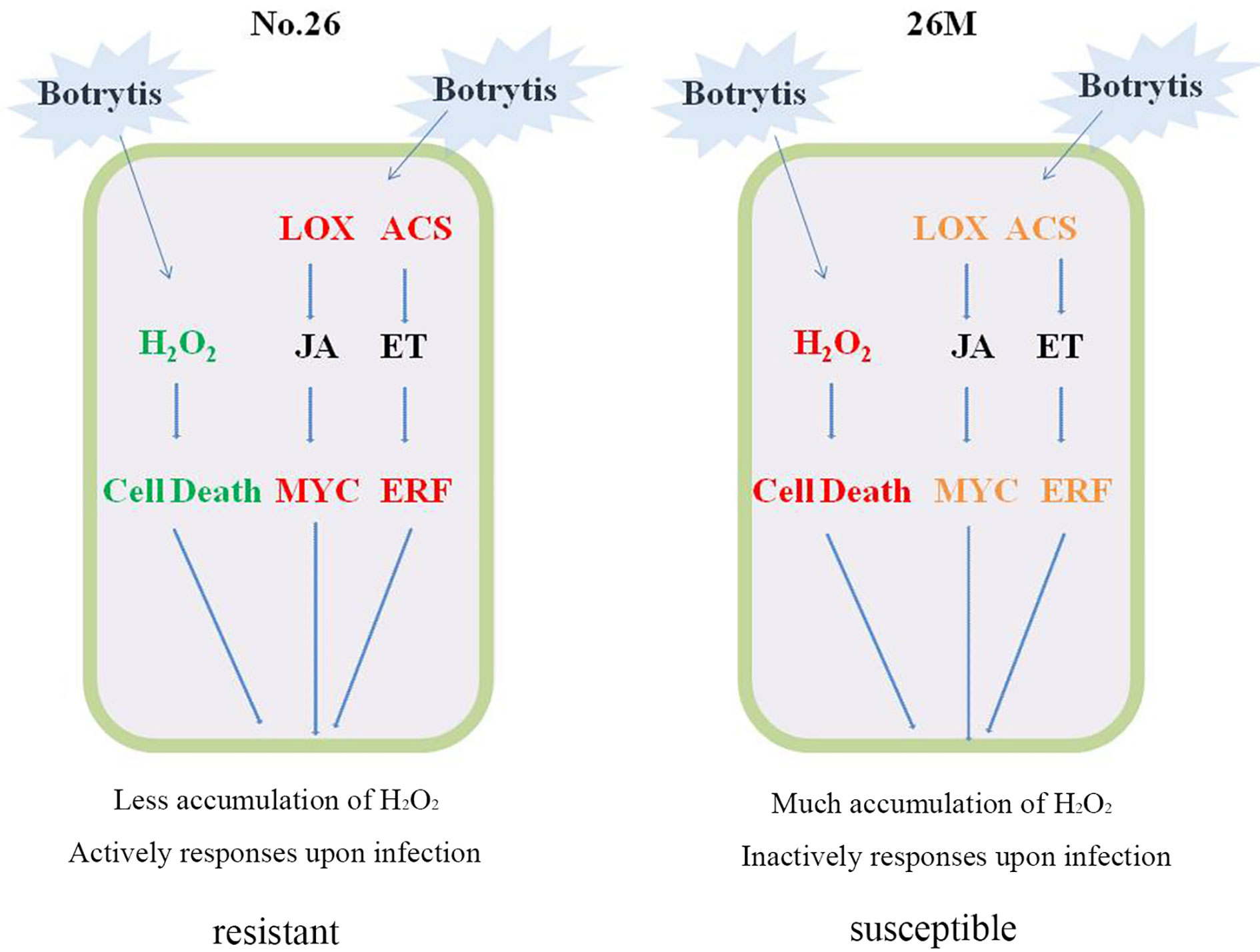

Botrytis cinerea is an important necrotrophic fungal pathogen with a broad host range and the ability to causing great economic losses in cucumber. However, the resistance mechanism against this pathogen in cucumber was not well understood. In this study, the microscopic observation of the spore growth, redox status measurements and transcriptome analysis were carried out after Botrytis cinerea infection in the resistant genotype No.26 and its susceptible mutant 26M. Results revealed shorter hypha, lower rate of spore germination, less acceleration of H2O2, O2-, and lower total glutathione content (GSH+GSSG) in No.26 than that in 26M, which were identified by the staining result of DAB and NBT. Transcriptome data showed that after pathogen infection, a total of 3901 and 789 different expression genes (DEGs) were identified in No.26 and 26M respectively. These DEGs were highly enriched in redox regulation pathway, hormone signaling pathway and plant-pathogen interaction pathway. The glutathione S-transferase genes, putative peroxidase gene, and NADPH oxidase were up-regulated in No.26 whereas these genes changed little in 26M after Botrytis cinerea infection. Jasmonic acid and ethylene biosynthesis and signaling pathways were distinctively activated in No.26 comparing with 26M upon infection. Much more plant defense related genes including mitogen-activated protein kinases, calmodulin, calmodulin-like protein, calcium-dependent protein kinase, and WRKY transcription factor were induced in No.26 than 26M after pathogen infection. Finally, a model was established which elucidated the resistance difference between resistant cucumber genotype and susceptible mutant after B. cinerea infection.

Introduction

Gray mold caused by B. cinerea, which is a plant fungal pathogen with a typically necrotrophic lifestyle. B. cinerea could attack more than 200 plant species including tomato, potato, oilseed rape, kiwi fruit, cucumber, and other high-value as well as important economic crops (Thomma, 2003; Williamson et al., 2007). Cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) is a warm season vegetable crop with suitable growing temperature between 15–32°C and it is mainly cultivated in greenhouse in China (Li et al., 2019). To increase the production and economic efficiency, most of the farmers grow their vegetables continuously in greenhouse that may cause continuous cropping obstacle and ultimately the accumulation of pathogens such as B. cinerea (Li et al., 2016). High humidity with 20–30°C temperature inside the greenhouse is suitable for the epidemic B. cinerea (Kozhar and Peever, 2018). This fungus can kill the host cells through the production of toxins and acquire nutrients from death cells, thus, a parasitic relationship starts with infection process.

Necrotrophic pathogen infection triggers plant immunity with further biological and physiological processes (Mengiste, 2012). Normally, necrotrophic pathogens are shown to be facilitated by the onset of the hypersensitivity (HR), such as host cell death (van Kan, 2006; Williams et al., 2011), production of various secondary metabolites (Sanchez-Vallet et al., 2010), hormones changes (Garcia-Andrade et al., 2011; La Camera et al., 2011; Duan et al., 2014) and the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Lehmann et al., 2014; Survila et al., 2016). Previously, it has been reported that ROS play a major role in plant and pathogen interactions (Wang et al., 2019), and the hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) content of the plants increased by regulating the redox signaling pathways after pathogens infection, (Foyer and Noctor, 2005). The level of cellular ROS was one of the cellular redox status markers, and the higher the ROS level, the more oxidizing the cellular redox environment was (Martinez-Sanchez and Giuliani, 2007). Many signaling molecules are important in plants defense response and redox sensitiveness. However, ROS caused severe damage even plant cell death when it accumulated to toxic levels (Baxter et al., 2014). In order to adjust the cellular redox status of some molecules, plants initiated their corresponding scavenging systems (enzymatic and non-enzymatic) to scavenge high intracellular ROS levels which damage the plant integrity (Finiti et al., 2014). Non-enzymatic system has been reported an important one which mainly depended on glutathione (GSH) and ascorbic acid to maintain the intracellular redox homeostasis via AsA-GSH cycle (Smirnoff, 2007; Foyer and Noctor, 2011). AsA remove the H2O2 and eliminate oxidation damage in the cell. First, AsA was oxidized into dehydroascorbate (DHA) under the action of ascorbate peroxidase (APX; EC 1.11.1.11), and then the DHA reduced to dehydroascorbate reductase (DHAR; EC 1.8.5.1). During redox regulation, the glutathione disulfide (GSSG) was converted into GSH which could be recycled through the action of glutathione reductase (GR) using reduced NADPH as the electron donor (Apel and Hirt, 2004).

As the most commonly known members of phytohormones, Jasmonic acid (JA) signaling pathways were reported to have an active effect on inhibiting gray mold (Liu et al., 2019). It was generally believed that activating of JA signaling pathway can induce resistance against necrotrophs (Liu et al., 2019) and endogenous contents of JAs was rapidly up-regulated and then triggered the formation of COI1-JA-JAZ ternary complex to induce degradation of the Jasmonate-ZIM domain (JAZ) proteins (Zhang et al., 2019). The basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factor MYC2 acted as a key regulator in the JA signaling pathway (Boter et al., 2004; Lorenzo et al., 2004; Dombrecht et al., 2007) and transcriptional activity of MYC2 was repressed by JAZ (Chini et al., 2007; Thines et al., 2007; Pauwels et al., 2010).

Ethylene (ET) has been reported to play crucial roles in both basal and race-specific immunity (Liu et al., 2018) and found that it plays a crucial role in defense response against Botrytis (Audenaert et al., 2002; Belkhadir et al., 2012), especially the ethylene biosynthesis and signaling transduction was induced in response to B. cinerea (Nambeesan et al., 2012). Indeed, the activation of ethylene biosynthesis and production under pathogen infection was an early resistance response of the plants (Chagué et al., 2006). In plants, ethylene was synthesized from the amino acid ‘methionine’ through the intermediate aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC) pathway (Chagué et al., 2006), and it was reported that ACC synthase was the rate-limiting enzyme of ethylene biosynthesis in plants (Liu and Zhang, 2004). ET signals transduction components such as ethylene response factors (ERFs) and ethylene insensitive (EIN) were often involved in plant resistance to B. cinerea (Wang et al., 2015).

The induction of phenylpropanoid biosynthesis is a well-known response of plants to of B. cinerea infection (Dixon et al., 2002; Wei et al., 2017; Oliva et al., 2020), which provided physical and chemical barriers such as reinforcement of plant cell walls (Barber and Mitchell, 1997). A variety of phenylpropanoid-based polymers including coumarate, ferulate, kaempferol, phenylethyl iso-thiocyanate, 3-phenyllactate, and salicylate were significantly synthesized under the infection of B. cinerea via the catalyzing of phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) and cinnamoyl-CoA reductase (CCR) (Naikoo et al., 2019). The related genes encoded the enzymes involved in the phenylpropanoid biosynthetic pathways were induced (Lloyd et al., 2011). The accumulation of phenylalanine derivatives reduced susceptibility of Arabidopsis as well as petunia to B. cinerea (Oliva et al., 2020). Lignin biosynthesis is a downstream branch of the phenylpropanoid pathway and the increased expression of genes in lignin biosynthesis has been noted recently, which can thick cell walls to form a physical barrier and inhibit pathogen invasion and colonization (Lee et al., 2019). At the same time, accumulation of lignin also inhibits the spread of pathogens and prevents the pathogens from extracting nutrients from host plants (Mottiar et al., 2016). Thereby, phenylpropanoid-derived metabolites are important in defense against B. cinerea.

Cucumber had a narrow genetic background with multiple uses in fresh and processed products, so it was critical important to develop some specialized genotypes for research of genetic modification and innovation, such as disease resistance, stress tolerance, nutritional quality and plant architecture. The available variations for cucumber could be induced by EMS at present. In our study, the resistant genotype and its susceptible EMS-induced mutant were used to investigate the mechanism that regulated responses to B. cinerea infection using histological and transcriptome analysis. Differential gene expressions associated with redox regulation and hormone signaling transduction network governing the cucumber defense response and its discovery mechanisms to B. cinerea infection were dissected. It will be helpful to uncover the redox status, JA/ET signaling pathway and plant-pathogen interaction pathway regulated in response to B. cinerea infection between the resistant genotype and its susceptible mutant. Our study will also lay a foundation for the mechanism more clearly in regulating resistance to B. cinerea and will provide a strategy to explore plant defense responses to B. cinerea on other horticultural crops.

Materials and Methods

Plant Material and Growth Conditions

The plant materials used in this study were provided by our Cucumber Research Group, College of Horticulture, Northwest A&F University, P.R. China and they were the important parental lines in our research group. Cucumber resistant inbred line No.26 and its susceptible mutation 26M induced by EMS were used. The mutant used in our study is the fifth generation of self-breeding seedlings. No significant difference in the growth rate of these two cucumber lines was found, even at seedling stage or maturity stage during the growth process. Seedlings were grown in a controlled growth chamber with a temperature maintained 24 ± 2°C, 16 h light/8 h dark photoperiod and 80%–90% relative humidity. Seedlings having two true leaves were used for pathogen inoculation.

Fungal Pathogen and Preparation of Spore Suspension

B. cinerea was isolated from cucumber plants in greenhouse of Yangling, Shaanxi, China. The pathogens were identified by analyzing their spore morphology and gene sequence. The primer of internal transcribed spacer (ITS1: CTTGGTCATTTAGAGGAAGTAA, ITS4: TCCTCCGCTTATTGATTATGC) was used to molecular identification. Reinfection experiment was carried out in the normal cucumber plant. For conidial production, B. cinerea was cultured on potato glucose agar medium at 22°C for 15–20 days in darkness. After 2 weeks, the spores were harvested and filtered through sterile medical gauze. Spores were counted with a haemocytometer and adjusted to 1×104 conidia ml-1 using distilled water and 2% sucrose was added as a source of nutrient to start the infection (La Camera et al., 2011).

Inoculation of Seedlings

Seedling were sprayed with spore suspension until leaf dripping using sprayer, while control plants were sprayed with same amount of sterile distilled water. After inoculation, seedlings were kept in a growth cabinet having same growing conditions as mentioned earlier for 2 days. Samples were harvested at 0, 12, 24, 48 hpi. The experiment was replicated three times and at least five seedlings per replicate were used. The collected samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C for further analysis.

In order to assess for disease resistance of seedlings, the 20 μl spore suspension containing 104 spores ml-1 were dropped on two sides of the mid-vein of the leaf (La Camera et al., 2011). Equal volume ddH2O were dropped as control. Lesion size was measured at 3, 4, 5, and 6 days post-inoculation (dpi). Leaves were harvested at 4, 12, 16, 20, 24, 48, 72, 120 hpi for staining.

Staining Methods

H2O2 was stained using 3, 3-diaminobenzidine-tetrahydrochloride (DAB) (Sigma, D8001) according to Orozco-Cardenas and Ryan (1999) in order to observe conveniently. O2− was stained using nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT) (Sigma, N6639) according to Carol et al. (2005). The KOH-aniline blue fluorescence staining was used to observe the development of the fungal spores according to Hood and Shew (1996). The fungi were observed using Olympus BX-51 inverted fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Japan) under ultravioletray light.

The spore germination rate and length of the hyphae were observed at 48 hpi. Image was analyzed using Image J.

Measurement of Glutathione Content

Determination of total glutathione was carried out according to Rahman et al. (2006) with a little bit modifications. Briefly, 0.1 g cucumber leaf was weighted and ground in liquid nitrogen. The reaction volumes were containing 20 μl of KPE buffer (0.1M potassium phosphate buffer with 5mM EDTA disodium salt, pH 7.5), 20 μl clear supernatant, 120 μl equal volume mixture of freshly prepared 0.06% DTNB [5,50-dithiobis (2-nitrobenzoic acid); Sigma] in KPE and 3 U of GR (Sigma) in KPE, and 60 μl NADPH (Sigma). The solution of the reactions displayed yellow. The absorbance was immediately read at 412 nm in a microplate reader.

For GSSG assay, 4 μl of 2-vinylpyridine (Sigma) was added to 20 μl of clear supernatant and mixed well to produce GSH. The reaction was allowed to proceed for 1 h at room temperature in laboratory fume hood. The derivative samples were assayed by the same method as described for total GSH. The total GSH and GSSG concentrations in samples were calculated using a standard curve of GSH and GSSG (containing 2 ml of 2-vinylpyridine) (Sigma).

Determination of H2O2 and O2-

Determination of the H2O2 referred to the method of Khan et al. (2014). Absorbance was measured at 390 nm by full-wavelength microplate reader (Infinite M200 Pro, Switzerland) and 3 repetitions per treatment. A standard curve was prepared using the H2O2 standard solution, and the H2O2 content of the sample was calculated from the standard curve.

The determination of the O2- content was carried out by the method of Liu and Wang (2012) with some modifications. Absorbance was measured at 530 nm by full-wavelength micro plate reader (Infinite M200 Pro, Switzerland) and 3 repetitions per treatment. At the same time, a standard curve was prepared using the NaNO2 standard solution to calculate the concentration of O2-.

Transcriptome Analysis and Functional Annotation

Leaf samples from the control and treated plants were collected at 48 hpi, frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C. Three seedlings was used as one replicates and three replicates are included. Samples were sent to Novogene in Beijing (https://en.novogene.com) for RNA sequencing. The reference genome for transcriptome analysis was obtained from http://cucurbitgenomics.org/organism/2.

For deferentially expressed genes (DEGs) analysis, the original read count was normalized. Then the statistical model was used to calculate the hypothesis test probability (p value). Multiple hypothesis test corrections were performed to obtain False Discovery Rate (FDR) values. The statistically significant DEGs (P-value < 0.05; |log2 FC| > 0) of the resistant versus susceptible cucumber comparison were used to identify enriched Gene ontology (GO) terms. Cucumber gene locus IDs identified through the DEG analysis was used to perform gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis. RNA-seq raw data are available under the website of NCBI ((https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) with the BioProject ID PRJNA630950.

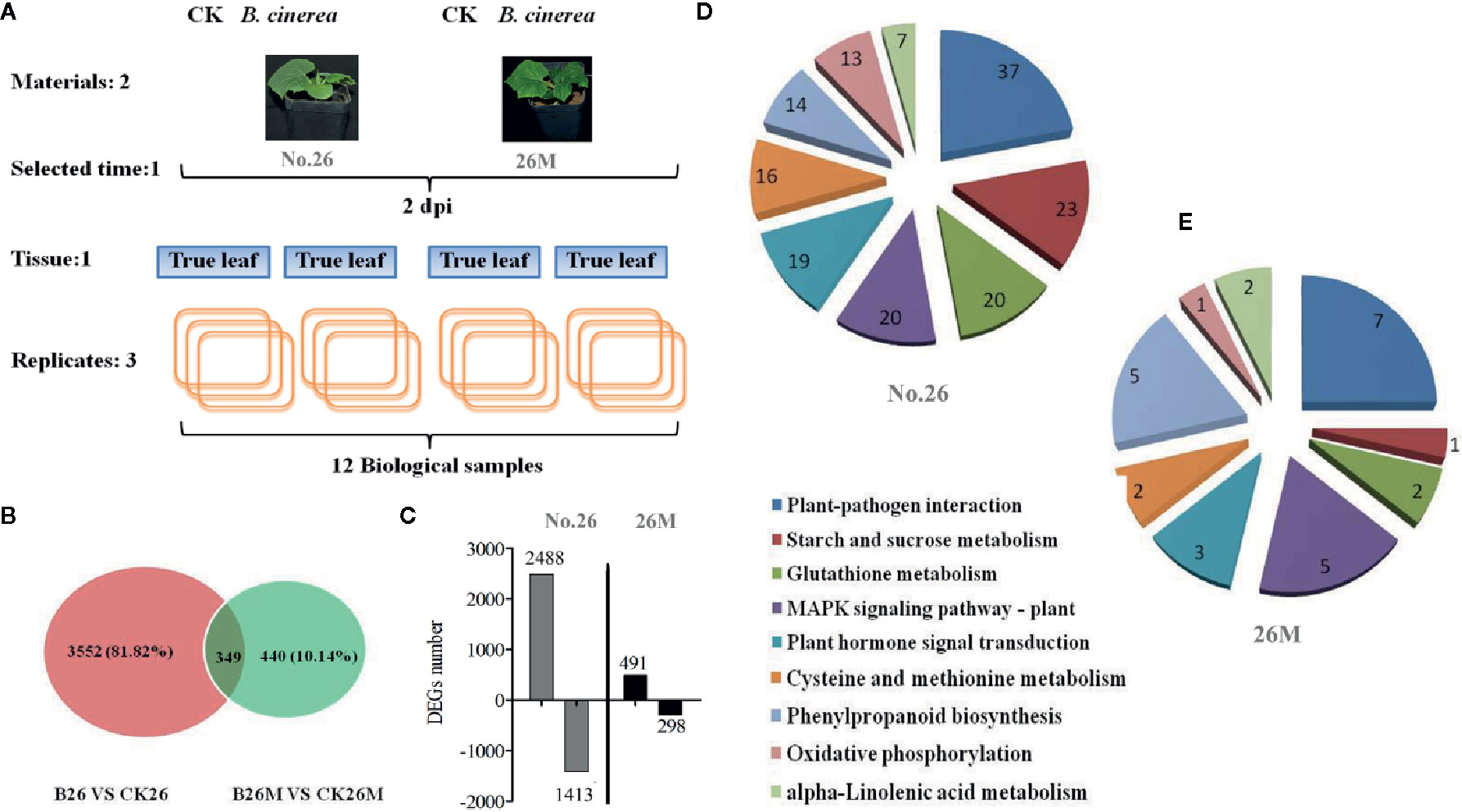

Validations of DEGs Using Quantitative Real-Time PCR

To confirm the accuracy and reproducibility of the Illumina RNA-Seq results, six candidate DEGs were selected to be tested using qRT-PCR. The leaf of the resistant No.26 and susceptible 26M plants were sampled at 48 hpi, frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C. Total RNA was extracted using EasyPure™ Plant RNA kit (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China). Genomic DNA was digested by using DNase I (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). cDNA was synthesized using cDNA synthesis kit (TaKaRa Biotechnology, Dalian, China) and quantified with a spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Inc.)

All qRT-PCR was run with SYBR green (TaKaRa Biotechnology, Dalian, and China) with a QuantStudio®5 real time-PCR machine (Life Technologies, USA). 10 μl of Mix, 0.6 μl of both the forward and reverse gene specific primers (Table 1), 2 μl of cDNA, and 6.8 μl of RNase-free water were included per reaction. The process for PCR amplification was as follows: initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles at 95°C for 30 s, 56°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 15 s. CsUBQ5 was used as reference gene to normalize transcript level for each sample, and the final data was calculated using formula 2−ΔΔCT.

Statistic Analysis

All data were analyzed using SPSS 20 (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, Chicago, IL, USA) for Windows PC. Values were presented as mean ± standard deviations (SD). Statistical significance was calculated using Student’s t-test and one-way ANOVA with Duncan’s multiple range test (P<0.05). The statistically significant difference (p<0.05) were presented using asterisk between different genotypes. Histograms were generated using Graph Pad Prism5 (Graph Pad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA, 2005). The Heatmap were generated with Heml (version 1.0.3.7) and MeV (Multi Experiment Viewer 4.7.4, TIGR, China) to show the expression patterns of genes.

Results

The Lesion Development and Growth of B. cinerea Between the Susceptible and Resistant Cucumber Genotypes

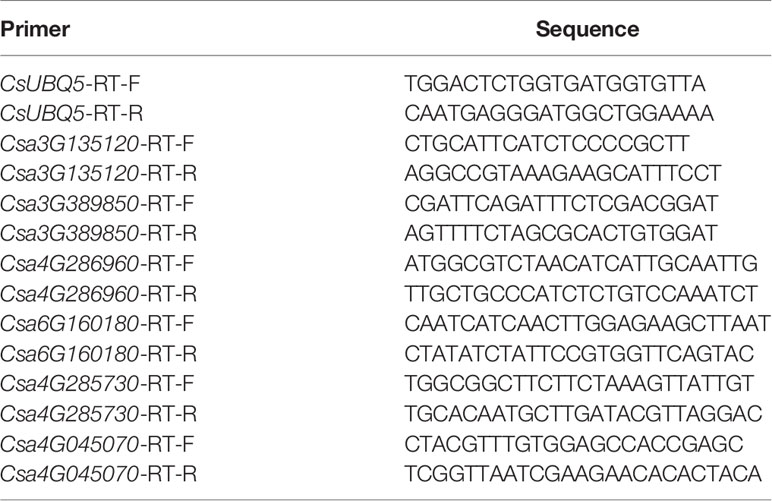

Lesion development was observed after infection by the identified B. cinerea (Figure S1). Visible lesions were first observed on the back side of leaves in both cucumber lines at 48 hpi. Then the lesions on the leaves of the two cucumber genotypes became water-soaked and macerated, displayed a typical spreading symptom (Figure 1A). The lesion area was measured. The lesion area ranged from 0.047 to 0.42 cm2 in No.26 whereas the lesion area changed from 0.17 to 0.55 cm2 in 26M (Figure 1B). A significant difference in the lesion area of both genotypes was observed at 5 days and 6 dpi.

Figure 1 Symptom development in susceptible (26M) and resistant (No. 26) cucumber. (A) Disease symptoms observed at 0, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 days post-inoculation (dpi). (B) The lesion area at 3, 4, 5, 6 days post-inoculation (dpi) in susceptible and resistant cucumber; (C) The length of primary hyphal at 2 days post-inoculation (dpi) in susceptible and resistant cucumber; (D) The germination of spores at 1 day post-inoculation (dpi) in susceptible and resistant cucumber. (E) Growth of B. cinerea was observed at 1, 2, 3, 5 days post-inoculation (dpi). Red arrow: conidium; Yellow arrow: stomata; Black arrow: germ tube; Green arrow: callose; hy: hypha; Fifteen plants per cucumber genotype were infected with B. cinerea and lesion sizes were measured. The means of lesion size data from five independent experiments are shown (mean ± SD). Five seedlings per replicate and three replicates are included for staining. Asterisk indicated the statistically significant difference between different cucumber genotypes after B. cinerea infection (p < 0.05). Bar=50 μm.

In order to observe the germination and growth of B. cinerea on the inoculated leaves, 10 μl spore suspension were dropped both sides of the leaf beside the main vein. The conidia of B. cinerea germinated at 24 h post-inoculation (hpi) and the developed mycelia get elongated after 48 h post-inoculation (hpi) (Figure 1E). After penetration of the cuticle the fungus hypha formed and elongated at 48 hpi. Hyphae continuously elongated with invasion progresses (Figure 1E). We also measured the rate of spore germination and length of primary hypha at 48 hpi (Figures 1C, D). The result showed that the wild type No.26 had lower spore germination rate and shorter mycelia than that in 26M. The rate of spore germination was individually 23.23% in No.26 and 82.16% in 26M. The mean length of primary hypha was about 1.07 cm in No.26, while the mean length of primary hypha was about 1.89 cm in 26M.

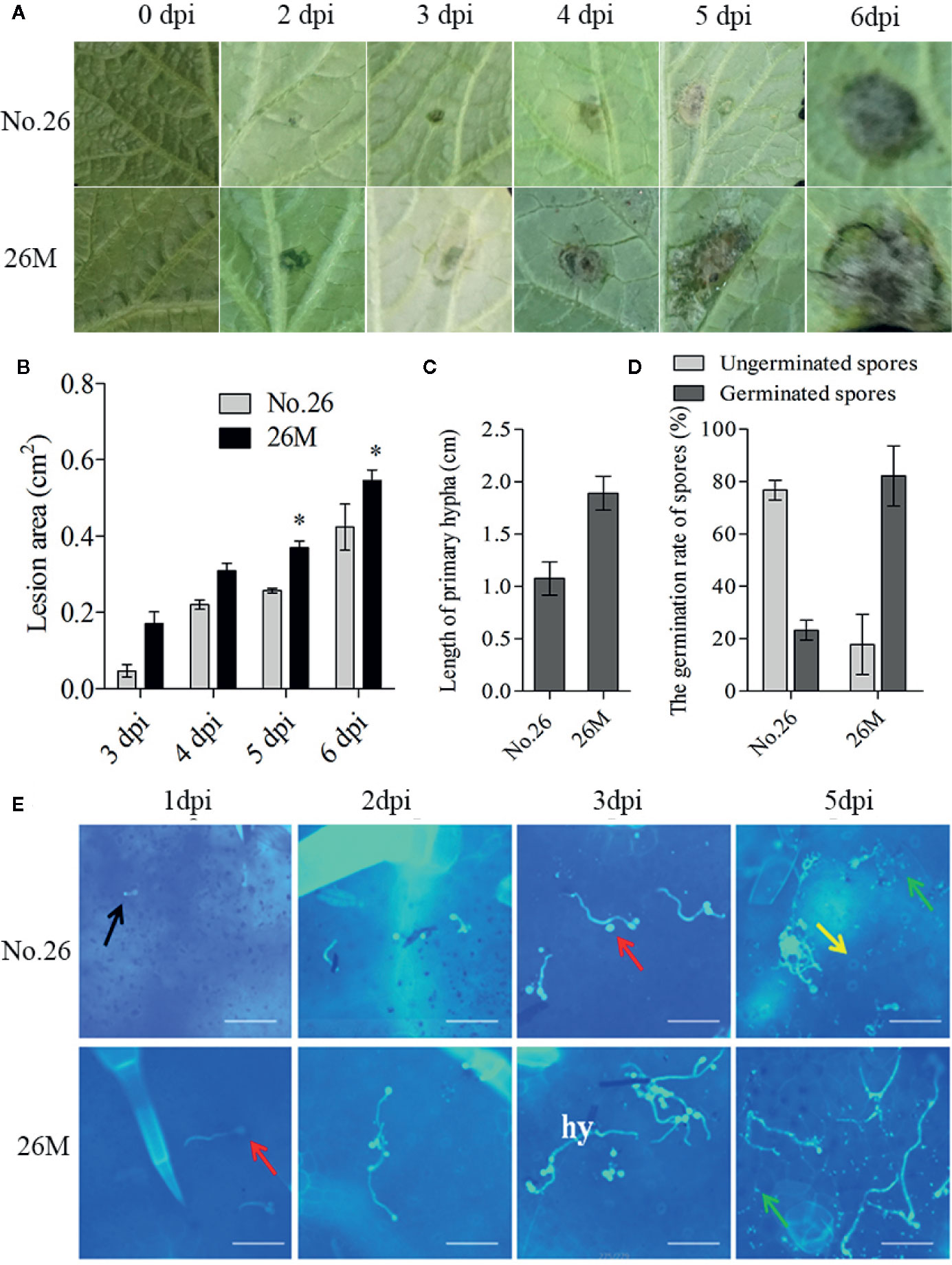

The Difference in the Content of H2O2 and O2- Between Infected Leaves of No.26 and 26M

Quantitative measurements of ROS were carried out and the microscopy detections of superoxide ion (O2-) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) were observed using nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT) and 3, 3’-diaminobenzidine (DAB) staining respectively. It showed that the enhanced synthesis of O2- and H2O2 were observed in the leaves after inoculation of B. cinerea. The H2O2 accumulation was observed in the early time of inoculated leaves of both 26M and No.26 at 4 hpi (Figure 2A), and the significant difference between them was observed at 12 hpi. Accumulation of H2O2 in the leaves of 26M was significantly higher than that in the leaves of No.26 at 12 dpi and 24 hpi (Figure 2B1).

Figure 2 Content of hydrogen peroxide, superoxide anion. (A) DAB and NBT staining; (B1) the content of H2O2; (B2) the content of O2-; (B3) the content of total glutathione and (B4) the content of oxidized glutathione. At least five seedlings per replicate and three replicates are included for determining content of H2O2 and O2-. Asterisk indicated the statistically significant difference between different cucumber genotypes after B. cinerea infection (p < 0.05). Bar=50 μm (at 4 hpi). Bar=200 μm (at 12 hpi, 16 hpi, 20 hpi).

The production of O2- was higher at 4 hpi and 12 hpi in the inoculated leaves of 26M than No.26 (Figure 2A). During the infection, an obvious difference in the production of O2- was observed between the 26M and No.26 genotypes (Figures 2A, B2). The O2- concentration in the inoculated leaves of both genotypes reached the maximum at 48 hpi, and was significantly higher in 26M than No.26 (Figure 2B2).

The Difference of GSH Content Between Infected Leaves of No.26 and 26M

GSH participated in the regeneration of ascorbate via dehydroascorbate reductase (DHAR), thus contributing to H2O2 detoxification (Smirnoff, 2007). The total GSH content increased after the seedlings were inoculated with suspension of pathogen (Figure 2B3) and peaked at 24 hpi in both 26M and No.26 genotypes. The content of total GSH in 26M was much higher than that in No.26 at 12 hpi and 48 hpi after B. cinerea infection. The content of total GSH in 26M was 1.33 and 1.17 folds respectively as compared with No.26. The content of GSSG showed the similar trend with total GSH content which was significantly increased with the infection time in both No.26 and 26M genotypes and peaked at 24 hpi (Figure 2B4). This suggests an effect of fungi treatment on the oxidative imbalance.

Differential Expression Genes Between 26M and No.26 After B. cinerea Infection

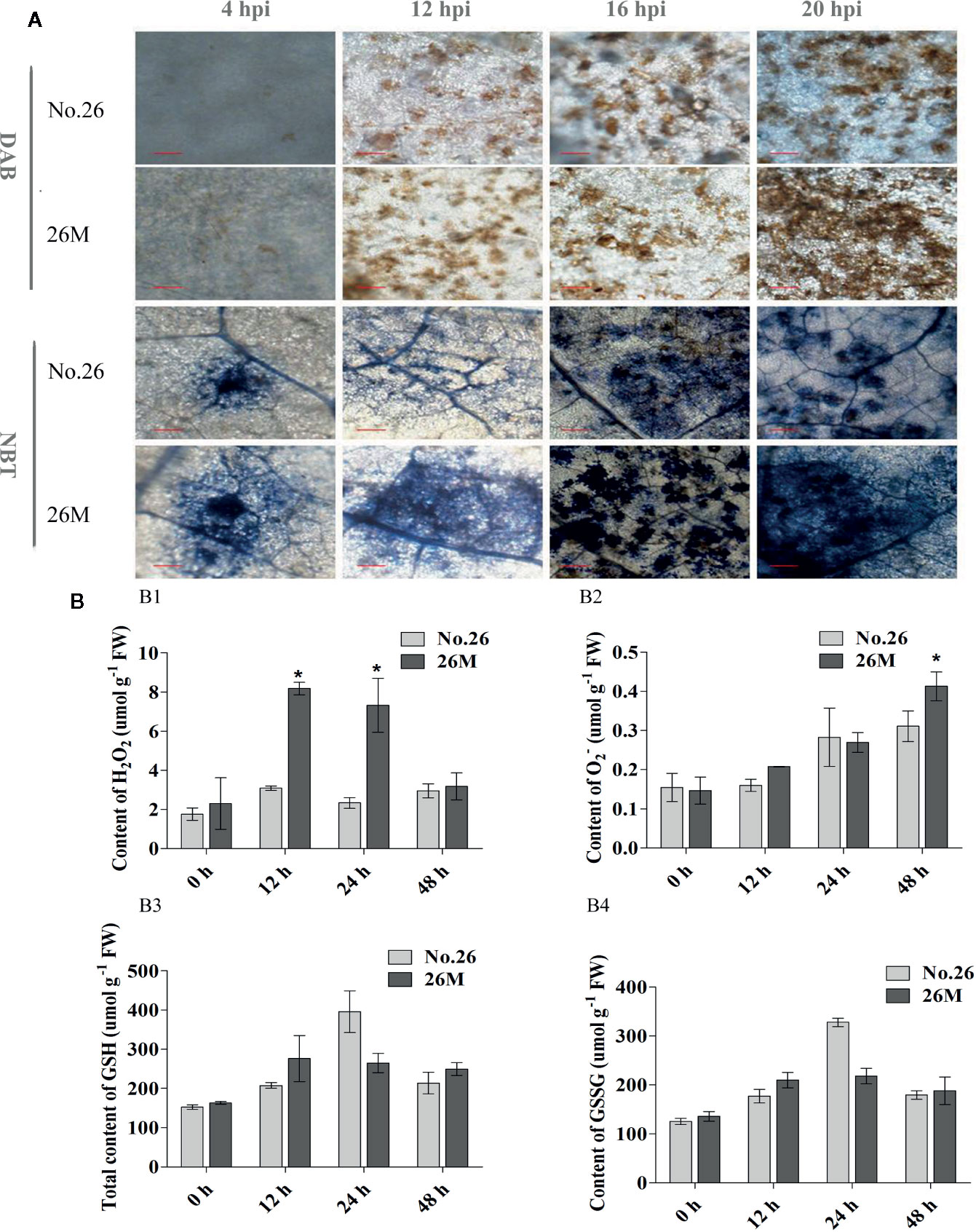

A total of 3901 DEGs were identified between No.26 and its control, while 789 DEGs were identified between 26M and its control respectively (Figures 3A, B). Among DEGs in 26M, 491 DEGs were significantly up-regulated and 298 DEGs were significantly down-regulated. In resistant No.26 genotype, 2,488 DEGs were significantly up-regulated and 1,413 DEGs were down-regulated in a significant manner (Figure 3C). After B. cinerea infection, it was noted that there were more up-regulated DEGs than down-regulated in both genotypes and more DEGs were identified in No.26 genotype as compared to 26M genotype. Multiple genes were found to be involved in the interaction between cucumber and Botrytis pathogen.

Figure 3 Expression patterns of unigenes differentially expressed after leaf inoculation with B. cinerea. (A) Experimental design; (B) The number of differentially expressed genes after inoculation with B. cinerea at 2 days post-inoculation (dpi) in the susceptible and resistant cucumber; (C) The number of up and down regulated expression genes after inoculation with B. cinerea at 2 days post-inoculation (dpi) in the susceptible and resistant cucumber. (D, E) The analysis of metabolite pathway in resistant and susceptible cucumber under B. cinerea infection.

The Result of KEGG Analysis

Based on the KEGG descriptions of the entire set of DEGs, the number of genes with particular annotation term was significantly overrepresented (Figures 3D, E). There were 104 biochemical pathways identified in No.26 compared as compared to the control, in which 37 DEGs were mainly enriched in plant defense responses during plant-pathogen interaction, while 19 important DEGs were identified in hormone signal transduction such as SA, JA and ET. Some other DEGs were found to be enriched in the MAPK signaling pathway, the redox regulation and phenylpropanoid biosynthesis in No.26 compared with that in control (Figure 3D). Whereas there were fewer DEGs identified in susceptible 26M, in which only seven DEGs were involved in plant-pathogen interaction, five and three DEGs involved in MAPK signaling and phytohormones signal transduction pathway respectively, two DEGs were found to be involved in glutathione metabolism and 5 were involved in phenylpropanoid biosynthesis (Figure 3E).

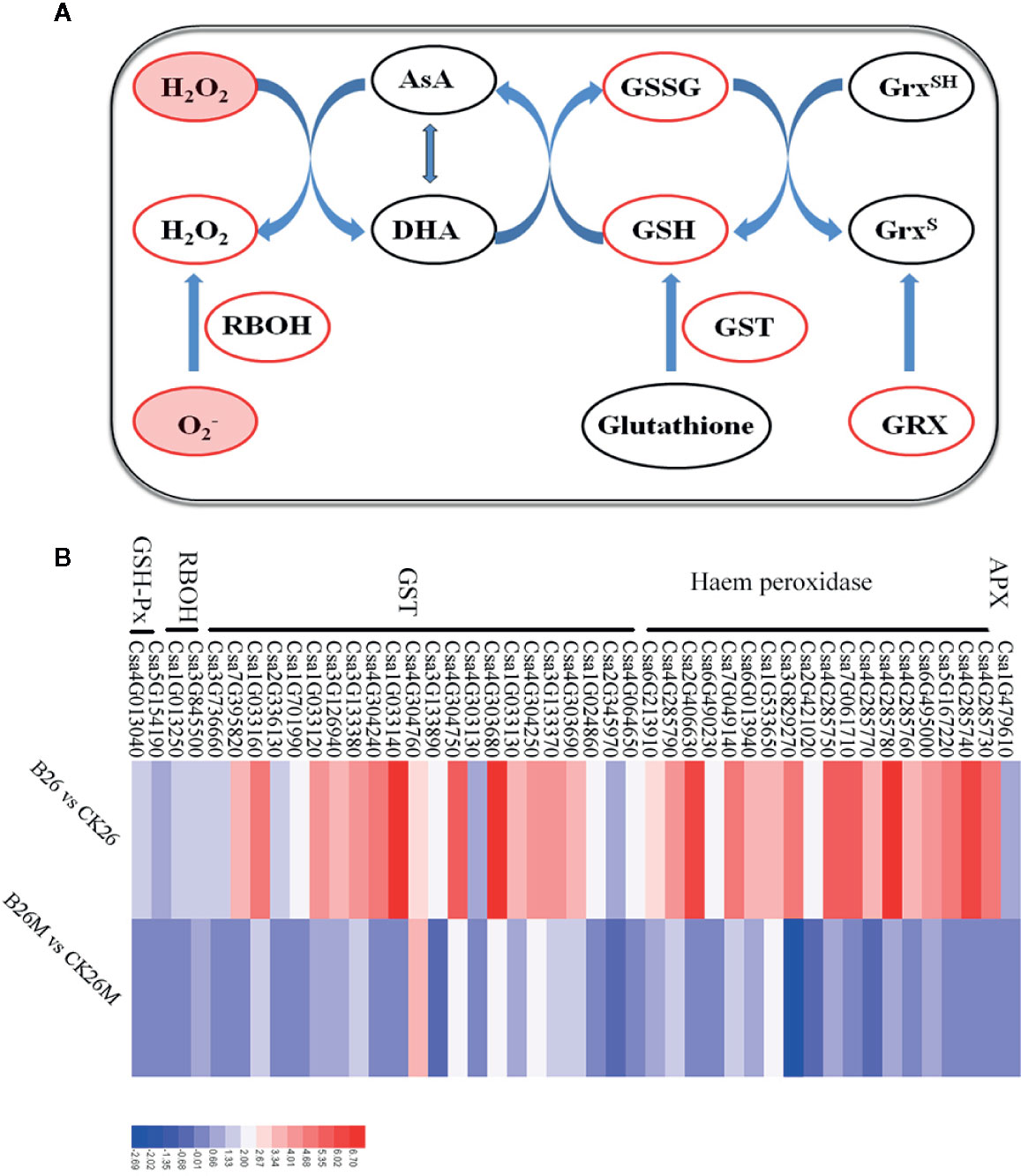

Differential Expression Genes Related to Redox Status

The oxidative burst caused by the hypersensitive response following perception of pathogen virulence signals is an early plant response to pathogen infection, which often led to rapid generation of superoxide, accumulation of H2O2 and the hypersensitive response (Torres et al., 2006; Patykowski, 2006; Asai and Yoshioka, 2009; Foyer and Noctor, 2013). After pathogen infection, some DEGs related to redox status regulation were identified, which were mainly involved in the up-regulation of some key antioxidant enzymes, such as peroxidases, glutathione S-transferase (GSTs), acerbates oxidase, superoxide, and NADPH oxidase in both 26M and No.26 genotypes (Figure 4). Four glutathione S-transferase genes (Csa4G303690, Csa3G126940, Csa4G304250, and Csa4G304760), one putative peroxidase gene (Csa7G049140) and a NADPH oxidase gene (Csa3G845500) were significantly up-regulated in resistant No.26 genotype compared with susceptible 26M genotype, indicating that resistant genotype No.26 prevented oxidative damage caused by B. cinerea. Several glutathione S-transferase genes such as Csa1G033160, Csa7G395820, Csa1G701990, Csa1G033130, Csa1G033140, and peroxidase genes including Csa4G304750, Csa4G285740, Csa6G013940, Csa4G285760, Csa4G285770 were up-regulated in resistant No.26 genotype (Figure 4B), whereas these genes changed little in susceptible 26M mutant. Other oxidoreductases were also identified such as glutaredoxin (Csa6G518190) which is involved in redox regulation, was induced in susceptible genotype 26M, whereas no change was found in No.26 genotype. Glutaredoxins (GRXs) played a crucial role in response to oxidative stress by reducing disulfides in various organisms, and it has been reported that A. thaliana glutaredoxin ATGRXS13 was required to facilitate B. cinerea infection (La Camera et al., 2011). All of these results suggested that rapid redox regulation in the resistant genotype responding to the infection of pathogen was necessary for the resistance.

Figure 4 Differentially expressed genes related to ROS regulation at 2 days post-inoculation (dpi) in the susceptible and resistant cucumber (B) and some key substances involved in ROS regulation (A). RBOH: respiratory burst oxidase homologue; GST: glutathione S-transferase; GRX: glutaredoxin; AsA: ascorbate and DHA: dehydroascorbate. Red box represented up-regulation of genes or increment in content.

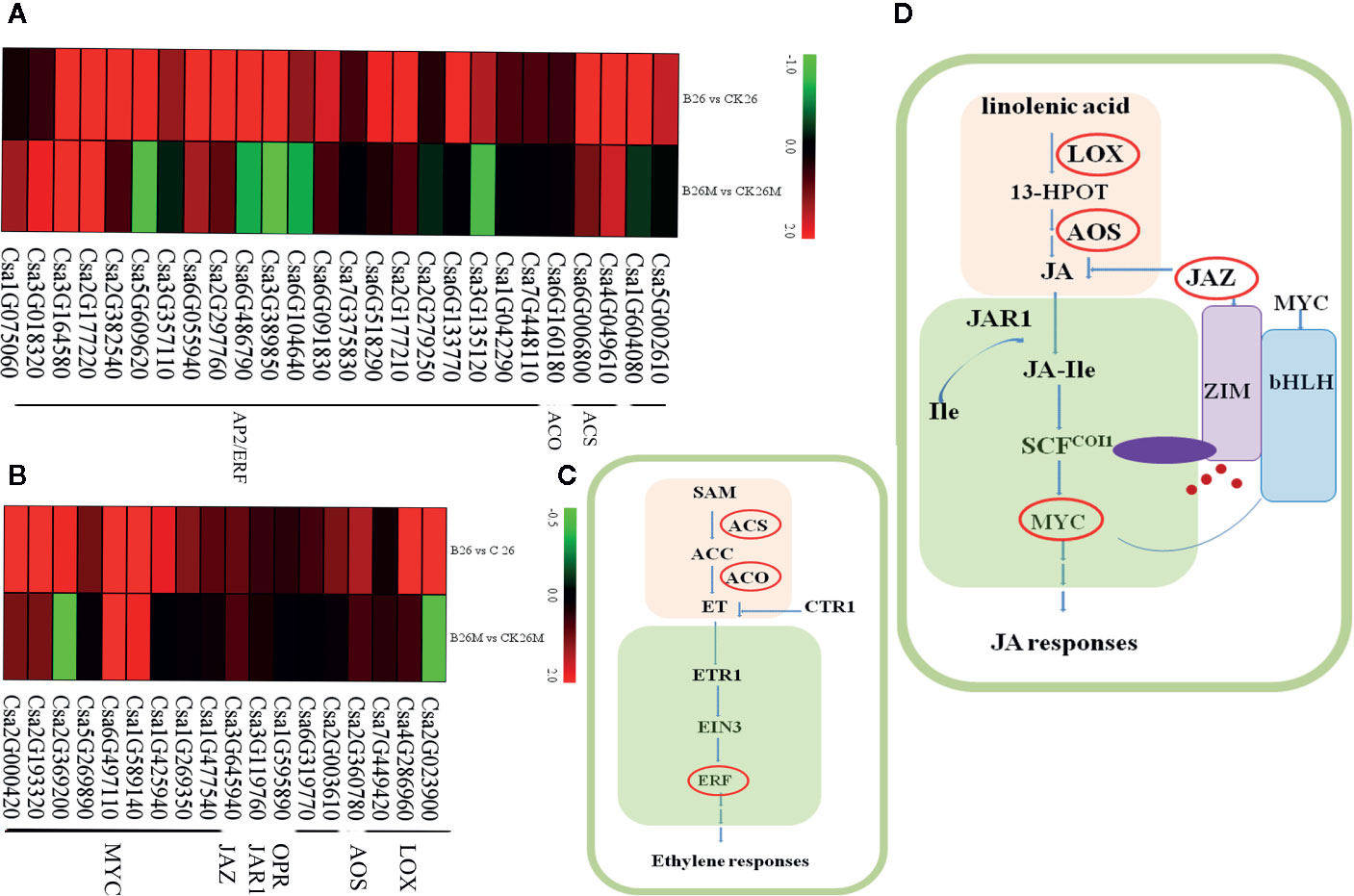

Differential Expression Genes Related to JA

Jasmonate acid (JA) plays an important role in the defense response of plants against fungal pathogens. Genes encoding of Lipoxygenase (LOX), allene oxide synthase (AOS), and alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) involved in JA synthesis pathway were identified and the jasmonate resistant 1 (JAR1), jasmonate ZIM domain protein (JAZ) and MYC transcription factor (MYC) genes involved in JA signaling pathway were identified after pathogen infection (Figures 5B, D). Some genes which were closely related to JA synthetic pathway were significantly up-regulated in No.26, such as one ADH (Csa7G322060), three oxidase reductases (Csa1G595890, Csa6G319770, and Csa2G003610), while only LOX (Csa7G449420) and AOS (Csa2G360780) were up-regulated in 26M, indicating that the synthesis of JA was inhibited in some extent in susceptible 26M. Eight MYC2 transcription factors (Csa2G000420, Csa1G425940, Csa1G589140, Csa1G269350, Csa5G269890, Csa2G193320, Csa2G369200, and Csa1G477540) which are the key components of JA signaling pathway were significantly up-regulated in No.26 genotype, while in 26M genotype they were either induced a little or not induced at all, showing that JA signal transduction pathway was inactive in 26M during B. cinerea infection.

Figure 5 Differentially expressed genes involved in hormone signal pathway at 2 days post-inoculation (dpi) in the susceptible and resistant cucumber. DEGs in ET signal (A) and JA signal (B). (C) Simplified ET signal transduction induced by B. cinerea infection. (D) Simplified JA signal transduction induced by B. cinerea infection. 13-HPOT (13(S)-9(Z), ll(E), 15(Z)-Hydroperoxyoctade-catrienoic acid); LOX (Lipoxygenase); JA (jasmonate); JAR1 (jasmonate resistant 1); SCF (Skp/Cullin/F-box); COI1 (coronatine-insensitive 1); JA-Ile (jasmonate-isoleucine); JAZ (jasmonate ZIM domain protein); MYC (MYC transcription factor); SAM (S′ adenosyl-l-methionine); ACS (1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid synthase); ACC (1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid); ACO (1- aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate oxidase); ET (ethylene); ETR1 (ethylene-response gene 1); CTR1 (constitutive triple response); EIN3 (ethylene insensitive 3); ERF (ethylene-responsive transcription factor). Red box represented up-regulation of genes.

Differential Expression Genes Related to ET

Ethylene (ET) is a main modulator of disease resistance in plants. Genes related to both ET biosynthetic and signal transduction pathways were identified during B. cinerea infection (Figures 5A, C), such as cytosine-specific methyltransferase, 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid synthase (ACS), 1- aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate oxidase (ACO), ethylene-responsive transcription factor (ERF). After B. cinerea infection, the ACS (Csa4G049610), ACO (Csa6G160180) and two methyltransferase (Csa1G604080 and Csa5G002610) genes were induced in No.26, whereas ACO and methyltransferase genes were not induced in 26M, indicating that synthesis of ET was inhibited in 26M during B. cinerea infection. Sixteen ERFs (Csa6G133770, Csa6G091830, Csa6G486790, Csa2G177210, Csa2G297760, Csa6G518290, Csa3G135120, Csa7G375830, Csa2G382540, Csa7G448110, Csa3G389850, Csa5G609620, Csa1G042290, Csa3G357110, Csa6G104640, and Csa2G279250) and a MAPK (Csa3G651720) gene was significantly up-regulated in resistant No.26 genotype, whereas only five other ERFs involving ET signal transduction were up-regulated in 26M, indicating that the ET signaling transduction pathway in 26M was not as active as that in No.26.

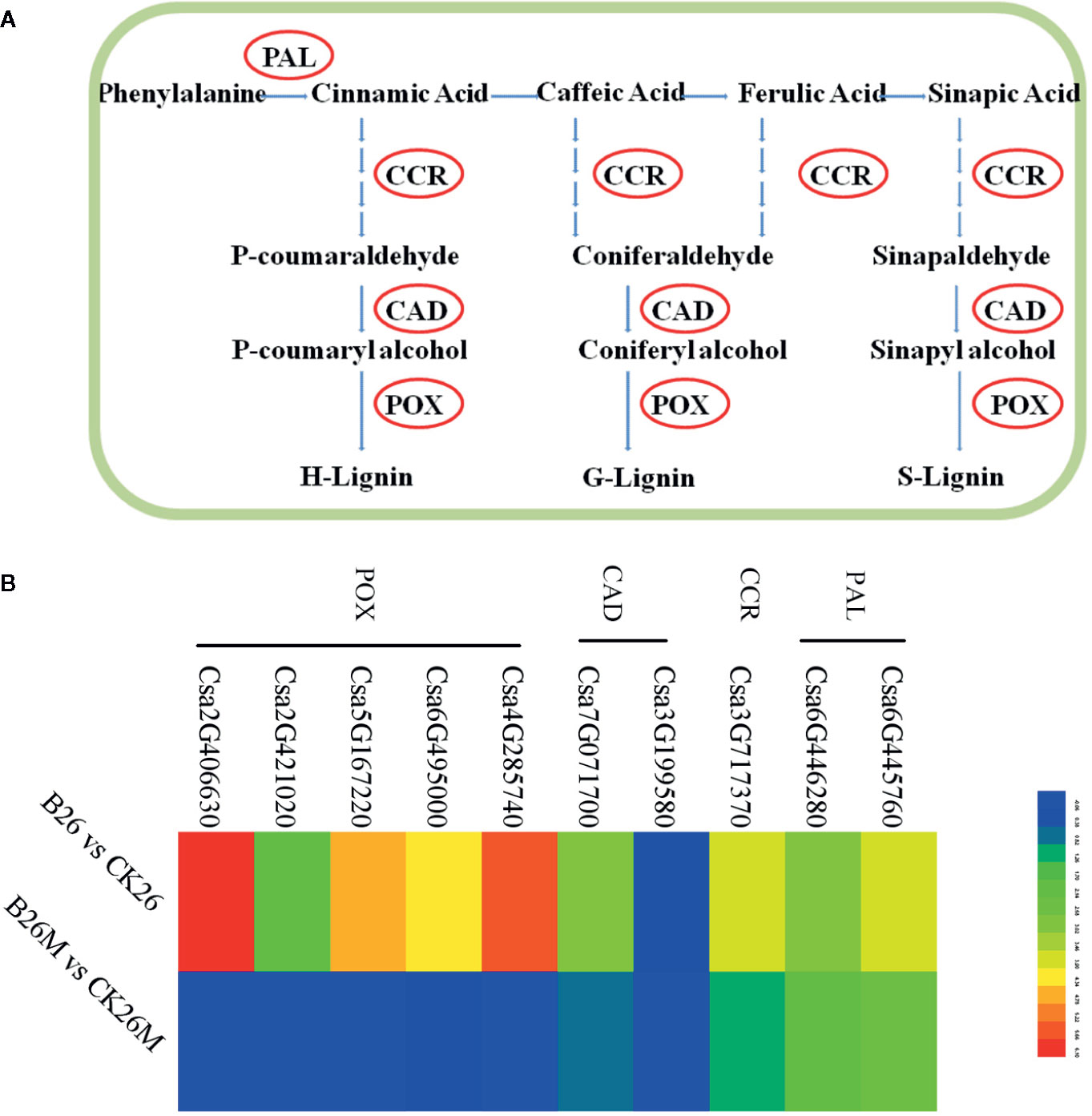

Differential Expression Genes Related to Phenylpropanoid Pathway

It was found that there were some DEGs associated with phenylpropanoid pathway to be identified between the resistant and susceptible cucumber genotypes (Figures 6A, B). Some genes such as phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL), lignin biosynthetic enzymes, cinnamoyl-CoA reductase (CCR), cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase (CAD), and peroxidase (POX) associated with phenylpropanoid pathway were up-regulated during B. cinerea infection. However, some genes were only induced in resistant No.26 genotype, such as CAD genes (Csa7G071700 and Csa3G199580) and peroxidase genes (Csa4G285740, Csa2G406630, Csa5G167220, Csa6G495000 and Csa2G421020), while the transcript level of these genes did not change in susceptible 26M genotype (Figure 6B).

Figure 6 Differentially expressed genes involved in PAL pathway at 2 days post-inoculation (dpi) in the susceptible and resistant cucumber (B) and simplified PAL pathway induced by B. cinerea infection (A) PAL (phenylalanine ammonia-lyase); CCR (cinnamoyl-CoA reductase); CAD (cinnamoyl alcohol dehydrogenase); POX (peroxidase). Red box represented up-regulation of genes.

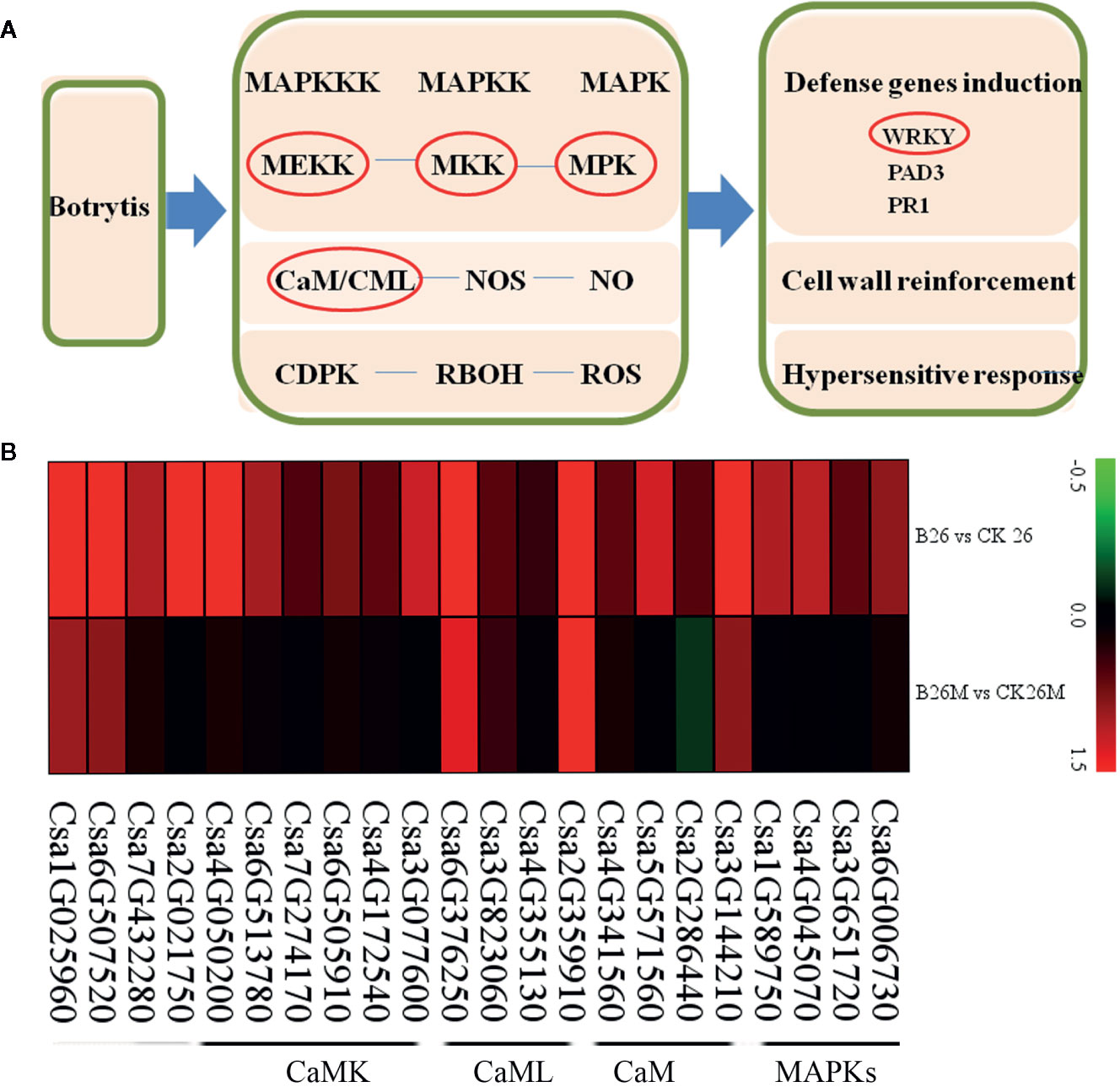

Differential Expression Genes Related to Plant Defense

The expression results revealed that some plant defense related DEGs such as mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), calmodulin (CaM), calmodulin-like protein (CaML), and calcium-dependent protein kinase (CaMK)were identified during B. cinerea infection (Figures 7A, B). Two MAPK genes (Csa6G006730 and Csa4G045070), two mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MAPKK) genes (Csa1G589750 and Csa3G651720) and a mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MAPKKK) gene (Csa2G021750) were highly up-regulated in No.26, whereas the above mentioned defense-related genes were not induced in 26M. Five CaM/CaML genes (Csa5G571560, Csa4G341560, Csa4G355130, Csa3G144210, and Csa2G286440) and six CaMK genes (Csa6G513780, Csa6G505910, Csa3G077600, Csa2G359910, Csa4G050200, Csa7G274170, and Csa4G172540) were significantly up-regulated in No.26, while they were not induced in 26M. In addition, glycerol kinase (Csa7G432280) and chitinase (Csa6G507520) were also up-regulated in No.26. CaM/CaML genes (Csa3G823060 and Csa6G376250) were induced in both genotypes after pathogen infection.

Figure 7 Differentially expressed genes involved in basal defense at 2 days post-inoculation (dpi) in the susceptible and resistant cucumber (B) and simplified basal defense induced by B. cinerea infection (A). MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase); CaM (calmodulin), CaML (calmodulin-like protein); CaMK (calcium-dependent protein kinase).

Interesting, the transcription level of 24 WRKY genes had changed in both cucumber genotypes upon B. cinerea, (Figure S2). Two WRKY genes (Csa2G406060 and Csa7G049170) were up-regulated in No.26, whereas these two genes were down-regulated in 26M after pathogen infection. The rest of WRKY genes displayed the similar expression pattern in both cucumber lines upon B. cinerea infection, which exhibited the higher transcription level in No.26 while lower transcription level in 26M. Among them, three WRKY genes (Csa6G486960, Csa5G223070 and Csa6G363560) were highly induced in No.26 upon B. cinerea, which were more than 6-fold change than control. They were showed lower transcription level in 26M and were about 1-fold change compared with control.

Validation of Transcriptomic Expression Levels

Six genes were selected to validate the RNA-Seq results through real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) in leaves of both No.26 and 26M genotypes. These genes included lipoxygenase (Csa4G286960), AP2 transcription factors (Csa3G135120 and Csa3G389850), ACO (Csa6G160180), POD (Csa4G285730), and MAPK (Csa4G045070) (Table 1). The qRT-PCR results were in accordance with the transcriptomic data (Figure S3). The transcript level of these genes in resistant cucumber genotype No.26 was higher than susceptible cucumber genotype 26M under B. cinerea infection.

Discussions

Redox Status Regulation Was Crucial for the Response to B. cinerea

There were few reports about the interaction between cucumber and B. cinerea by far, so the mechanism about the cucumber resistance to B. cinerea was not well elucidated. It was believed that redox-related gene expression and metabolites were activated in the priming of plant and were regulated by proper cellular function as well as enzymatic and non-enzymatic mechanisms (González-Bosch, 2018). ROS production and scavenging networks were composed of ROS-producing enzymes, antioxidant enzymes and biosynthetic pathways of antioxidants (Posmyk et al., 2009), which were crucial in the plant defense against external threats (Noctor et al., 2018). In current study, the regulation of oxidative state caused by B. cinerea was significantly different between the resistant and susceptible.

The oxidative burst and scavenging were often regulated by cellular detoxification system such as peroxidases, glutathione S-transferases, ascorbate oxidase, superoxide, and NADPH oxidase (Heller and Tudzynski, 2011). These activated antioxidant and detoxifying enzymes were activated and induced by the infection of pathogens in the invaded plant cells (Lamb and Dixon, 1997; AbuQamar et al., 2006; Parisy et al., 2007). In our study, it was found that some genes encoding antioxidant and detoxifying enzymes such as glutathione S-transferases (GSTs), peroxidase and other antioxidant enzymes were significantly induced in No.26, while these genes were not induced so obviously in the 26M genotype during B. cinerea pathogen infection (Figure 4). There were some other genes regarding glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) and peroxidase which were induced in the resistant cucumber genotype than in susceptible genotype, signifying that more ROS were removed in No.26 and less ROS were accumulated (Figure 2). Normally, ROS such as H2O2 and O2- occurred at early stage during infection of necrotrophics, which caused cell death or as an indicator of successful infection and colonization of necrotrophic pathogens (Govrin and Levine, 2000; Govrin et al., 2006; van Kan, 2006). The amount of ROS affected the extent of programmed cell death and the colonization of pathogens, which in turn affected the resistance of plant to pathogens (Figure 8).

Figure 8 Cellular model summarizing potential mechanism of cucumber resistance to B. cinerea. Red represented the higher level of gene expression and much accumulation of content; Green represented the less accumulation of content. Orange represented the lower level of gene expression.

GSH, belong to non-enzymatic antioxidant system, that can reduce ROS by directly reaction with it. GSH can also play an important role in the removal of ROS as a substrate for the enzymes. GSH and redox equilibrium-controlling genes were essential for an appropriate defense response against B. cinerea (Chassot et al., 2008). High content of total GSH and GSSG were detected after B. cinerea infection in both cucumber genotypes used in our study, reflecting a rapid regulation of oxidized status at this time (Figure 2). The result was consistent with the early oxidative burst which occurred on fungal inoculation (Finiti et al., 2014).

Multiple Hormone Signaling Pathways Modulated Resistance Responses to Botrytis Pathogens

Plant always defends itself through fine-tuning of the hormones to cope with biotic and abiotic stresses (Miao et al., 2019). JA, SA, and ET were thought to be main phytohormones in response to pathogen attack. It was generally believed that salicylic acid (SA) was traditionally associated with defense against biotrophic and hemibiotrophic pathogens, whereas jasmonic acid (JA) and ethylene (ET) signaling appear to be more important towards necrotrophic pathogens and herbivores (Erb et al., 2012; Mengiste, 2012; Pieterse et al., 2012; Han and Kahmann, 2019). It has been reported that the synthesis of JA was activated by the infection of B. cinerea through the upstream synthesis gene AdLoxD of tomato. Besides, the ET synthetic pathway was also elicited by the up-regulation of the ET-forming aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid oxidase gene in response to B. cinerea (Finiti et al., 2014). There were more and more evidences that the content of JA and ET increased after infection of B. cinerea.

The JA/ET signaling pathway was activated against necrotrophs through some key regulators such as transcription factors MYC2 and ERF (Kazan and Manners, 2009; Liu et al., 2018). The ERF1, ERF5, ERF6, RAP2.2, and ORA59 were involved in the regulation of plant defense against B. cinerea in Arabidopsis (Ouyang et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2018; Sham et al., 2019). The resistant ‘Syrah’ grapes displayed higher basal levels of JA-Ile comparing to the susceptible ‘Trincadeira’ along with higher expression of MYC2 and JAZ8 although the synthesis of jasmonic acid increased in infected berries of both ‘Syrah’ and ‘Trincadeira’ cultivars (Coelho et al., 2019). In our study, the synthetic pathway of JA and ET is inhibited to a certain extent in the susceptible material, resulting in partial inhibition of related signal transduction and inactive response to B. cinerea infection. This illustrated that the activation of hormone signals of JA/ET and the expression of downstream defense-related genes played an important role against gray mold resistance.

Resistance Responses to Botrytis Infection Was Closely Related With Phenylpropanoid Pathway

Phenylpropanoid pathway was reported to be a pivotal pathway in defending pathogen invasion because of phenylalanine derivatives, which play an active role to defend the pathogen attack (Dixon et al., 2002). PAL, lignin, coumarins, benzoic acids, stilbenes, and flavonoids/isoflavonoids were important derivatives of phenylpropanoid pathway which exhibited broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity and were believed to help the plants to fight against microbial disease (Dixon et al., 2002). The activities of PAL, cinnamate 4-hydroxylase (C4H) and CAD enzyme were differentially induced between the two apple cultivars in response to B. cinerea (Ma et al., 2018). In addition, the phenylpropane polymer lignin provided strength to the cell walls for preventing direct penetration of the fungus (Pesquet et al., 2019). CAD as a key enzyme in lignin biosynthesis, the AtCAD4/5 double mutant Arabidopsis exhibited 40% reduction in lignin biosynthesis and was more susceptible to infection (Sibout et al., 2005). Down-regulation of genes encoding PAL, lignin biosynthetic enzymes, ferulate 5-hydroxylase (F5H), cinnamoyl-CoA reductase (CCR) and CAD led to the reduction of resistance to necrotrophic fungi Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in resistant soybean line (Ranjan et al., 2019). In our study, the up-regulation of PAL gene, lignin biosynthetic enzymes gene, CCR gene, CAD gene and peroxidase (POX) gene were observed to be induced in No.26 resistant genotype, whereas only CCR gene was induced in susceptible genotype 26M, while CAD and POX genes exhibited no change in their expression, indicating that the activation of phenylpropanoid pathway might be the reason of resistance to Botrytis infection in the resistant genotype No.26.

Defense Related Genes Involved in Response to Botrytis Infection

Studies showed that MAPKs of tobacco and their orthologs in other species including Arabidopsis MPK3 and MPK6 were activated after PAMP treatment or pathogen infection (Yang et al., 2001; Ichimura et al., 2002), and MAPK cascades were predominately involved in defense when strawberry fruit were infected by B. cinerea (Haile et al., 2019). Inhibition of SlMPK1/2/3 disrupted tomato fruit defense signaling pathways and enhances the susceptibility to B. cinerea, while knock-down of SlMAPK3 reduced the disease resistance of tomato to B. cinerea (Zhang et al., 2018). Calmodulins (CaM) have been reported to be involved in plant defense responses (Kim et al., 2002; Kang et al., 2006). A Ca2+-independent calmodulin-binding proteins (CaMBP) affected defense against the B. cinerea in Arabidopsis (Lv et al., 2019). NtCaM1, NtCaM2 and NtCaM13 were induced by tobacco mosaic virus (TMV)-mediated hypersensitive reaction in tobacco (Takabatake et al., 2007). In our study, five CaM/CaML genes and six CaMK genes were significantly up-regulated in resistant genotype No.26, while they were not induced in 26M, which confirmed that the activation of CaM genes were essential for the resistance response of the No.26 genotype.

Global transcriptional profiling have implicated the involvement of key transcription factors (TFs) in interaction between plant and B. cinerea (AbuQamar et al., 2006; Mathys et al., 2012; Windram et al., 2012). These TF families included ERFs (Dey and Corina Vlot, 2015; Zhang et al., 2016), MYBs (Mengiste, 2012), NACs (Nuruzzaman et al., 2013), MYCs (Kazan and Manners, 2013) and WRKYs (Birkenbihl and Somssich, 2011; Jiang and Yu, 2016). These TFs either positively or negatively modulated the plant defenses. Reports showed that the wrky33 mutant was highly susceptible to B. cinerea (Liu et al., 2015). However, loss of function of WRKY57 has been reported to enhance the host resistance to this pathogen (Jiang and Yu, 2016). Our results also revealed that WRKY transcription factors were involved in B. cinerea infection. There were 24 WRKY transcription factors were detected (Figure S2). Some of the WRKY transcription factors (Csa2G406060, Csa3G727990, Csa6G486960, Csa5G223070, Csa7G328830, Csa4G051470, and Csa4G012390) showed higher transcript level in No.26 cucumber. All of the above-mentioned genes were up-regulated more than 3–6 folds while their expression was only 1–2 fold in 26M compared with uninfected cucumber. Csa7G049170 and Csa2G406060 WRKY genes had an opposite expression patterns in both cucumber genotypes, which were induced in No.26 and down-regulated in 26M respectively. These results showed that WRKY transcription factor might be a key factor in resistance to B. cinerea, which may regulated the gray mold either negatively or positively in cucumber.

Genotype-Related Differences in Response to Botrytis Infection

Different genotypes exhibited a different response to B. cinerea. Transcriptome study of tomato fruits upon B. cinerea infection displayed that the genes associated with biosynthesis and signal transduction of ethylene (ET) and jasmonic acid (JA) were involved in interaction between tomato fruit and pathogens (Blanco-Ulate et al., 2013). Same situation was observed on resistant and susceptible grape cultivars. The transcription level of genes involved in the JA signaling pathway was induced after B. cinerea infection (Coelho et al., 2019). In our study, similar results were also appeared in both cucumber genotypes upon infection. The infection of B. cinerea included accumulation of H2O2 as well as O2-, and up-regulated expression of genes related to synthesis and signal transduction of JA, ET, PAL and defense (Figures 2, 5–7).

However, some genotype-related differences were presented. Our results also revealed the effect of genotype on the ROS production and gene expression after B. cinerea infection. There were less accumulation of H2O2 and O2- and much more DEGs were induced in cucumber resistant genotype No.26 than that in cucumber susceptible genotype 26M upon infection (Figures 2B1, B2, 3B). All of the DEGs were summarized into three categories between No.26 and 26M. The first type was that DEGs had an opposite expression pattern in both cucumber genotypes, which were up-regulated in No.26 and down-regulated in 26M respectively. DEGs were induced in No.26 while their expression was constant in 26M, which was another expression pattern of DEGs. The last type was that expression pattern of DEGs were common in both cucumber genotypes. Difference was mainly focus on the fold change of EDGs. The Higher induced expression fold of DEGs was exhibited in No.26 whereas lower fold change of DEGs was shown in 26M. It indicated that some difference existed between two different cucumber genotypes after infection by B. cinerea. There was an exception for the content of total GSH. It was reported that glutathione can act as a powerful cellular redox agent to remove ROS and regulate post-translational modification of protein (Ball et al., 2004; Foyer and Noctor, 2005; Dalle-Donne et al., 2007). Obviously, glutathione initiated oxidative regulation because of increment of glutathione content in both cucumber lines upon B. cinerea infection. While measurement of glutathione content was not at later stage of infection but at early stage of infection, which may be the major reason why it was no significant difference in glutathione content between No.26 and 26M after B. cinerea infection. Moreover, previous research indicated that GSH also could act as a signaling molecule, which was not only involved in pathogen defense but also actively participate in the cross-communication with other signaling molecules such as JA and ET (Ghanta et al., 2011). Thus, the effect of GSH appeared to be unobvious among the many defense-response signal molecules induced at the early stage of infection in our study. Instead, some WRKY transcription factor might play an important role currently. Especially for the two WRKY genes Csa2G406060 and Csa7G049170, they may exert a key function in resistant to B. cinerea, because their completely different expression patterns were displayed in No.26 and 26M after B. cinerea infection. Other two WRKY genes Csa6G363560 and Csa6G486960 were also important. As for how these WRKY genes affect and regulate plant disease resistance, it needs to be further confirmed by experiment.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the role of ROS, JA, and ET in response to necrotrophic pathogens was revealed combined ROS content with differential expression genes involved in hormonal synthesis and signal transduction (Figure 8). In resistant cucumber genotype No.26, Less acceleration of H2O2 and O2- resulted in the less cell death that was beneficial to facilitate infection of B. cinerea. Higher transcription level of differential expression genes having a correlation with JA and ET signaling pathway triggered an active defense response that lead to the tolerance of cucumber No.26 against B. cinerea. While cucumber genotype 26M suffered from severe ROS production, accompanied by relative lower or constant transcription level of differential expression genes involved in JA and ET signaling pathway, which result in an inactive response and susceptible to B. cinerea.

Data Availability Statement

The RNA-seq data has been uploaded to NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). The BioProject ID is PRJNA630950. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA630950/.

Author Contributions

SC conceived and designed the experiments. YY performed the experiments and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. SC and KA revised the manuscript. YY, XW, and PC analyzed the data. KZ and WX contributed to reagents/materials. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 31772335), Ningxia Major Science and Technology Project during the 13th 5-Year Plan Period (2016BZ0904), and Shaanxi Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Project (NYKJ-2019-YL04).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2020.559070/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Figure 1 | Isolation and identification of B. cinerea. (A) the isolation of B. cinerea; (B) morphological observation of B.cinerea; (C) PCR amplification; (D) sequence alignment; (E) symptom of B. cinerea after reinfection in cucumber.

Supplementary Figure 2 | The DEGs of WRKY in susceptible (26M) and resistant (No. 26) cucumber at 2 dpi.

Supplementary Figure 3 | The validation of DEGs in susceptible (26M) and resistant (No. 26) cucumber at 2 dpi.

References

AbuQamar, S., Chen, X., Dhawan, R., Bluhm, B., Salmeron, J., Lam, S., et al. (2006). Expression profiling and mutant analysis reveals complex regulatory networks involved in Arabidopsis response to Botrytis infection. Plant J. 48, 28–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02849.x

Apel, K., Hirt, H. (2004). Reactive oxygen species: metabolism, oxidative stress, and signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 55, 373–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141701

Asai, S., Yoshioka, H. (2009). Nitric oxide as a partner of reactive oxygen species participates in disease resistance to nectrotophic pathogen Botrytis cinerea in Nicotiana benthamiana. Mol. Plant Microbe 22, 619–629. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-22-6-0619

Audenaert, K., De Meyer, G. B., Höfte, M. M. (2002). Abscisic acid determines basal susceptibility of tomato to Botrytis cinerea and suppresses salicylic acid-dependent signaling mechanisms. Plant Physiol. 128, 491–501. doi: 10.1104/pp.010605

Ball, L., Accotto, G. P., Bechtold, U., Creissen, G., Funck, D., Jimenez, A., et al. (2004). Evidence for a direct link between glutathione biosynthesis and stress defense gene expression in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 16, 2448–2462. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.022608

Barber, M. S., Mitchell, H. J. (1997). Regulation of phenylpropanoid metabolism in relation to lignin biosynthesis in plants. Int. Rev. Cytol. 172, 243–293. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(08)62362-1

Baxter, A., Mittler, R., Suzuki, N. (2014). ROS as key players in plant stress signaling. J. Exp. Bot. 65, 1229–1240. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert375

Belkhadir, Y., Jaillais, Y., Epple, P., Balsemão-Pires, E., Dangl, J. L., Chory, J. (2012). Brassinosteroids modulate the efficiency of plant immune responses to microbe-associated molecular patterns. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 109, 297–302. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112840108

Birkenbihl, R. P., Somssich, I. E. (2011). Transcriptional plant responses critical for resistance towards necrotrophic pathogens. Front. Plant Sci. 2:76. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2011.00076

Blanco-Ulate, B., Vincenti, E., Powell, A. L., Cantu, D. (2013). Tomato transcriptome and mutant analyses suggest a role for plant stress hormones in the interaction between fruit and Botrytis cinerea. Front. Plant Sci. 4, 142. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00142

Boter, M., Ruíz-Rivero, O., Abdeen, A., Prat, S. (2004). Conserved MYC transcription factors play a key role in jasmonate signaling both in tomato and Arabidopsis. Gene Dev. 18, 1577–1591. doi: 10.1101/gad.297704

Carol, R. J., Takeda, S., Linstead, P., Durrant, M. C., Kakesova, H., Derbyshire, P., et al. (2005). A RhoGDP dissociation inhibitor spatially regulates growth in root hair cells. Nature 438, 1013–1016. doi: 10.1038/nature04198

Chagué, V., Danit, L. V., Siewers, V., Gronover, C. S., Tudzynski, P., Tudzynski, B., et al. (2006). Ethylene sensing and gene activation in Botrytis cinerea: a missing link in ethylene regulation of fungus-plant interactions? Mol. Plant Microbe 19, 33–42. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-19-0033

Chassot, C., Buchala, A., Schoonbeek, H. J., Métraux, J. P., Lamotte, O. (2008). Wounding of Arabidopsis leaves causes a powerful but transient protection against Botrytis infection. Plant J. 55, 555–567. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03540.x

Chini, A., Fonseca, S., Fernandez, G., Adie, B., Chico, J. M., Lorenzo, O., et al. (2007). The JAZ family of repressors is the missing link in jasmonate signaling. Nature 448, 666–671. doi: 10.1038/nature06006

Coelho, J., Almeida-Trapp, M., Pimentel, D., Soares, F., Reis, P., Rego, C., et al. (2019). The study of hormonal metabolism of trincadeira and syrah cultivars indicates new roles of salicylic acid, jasmonates, ABA and IAA during grape ripening and upon infection with Botrytis cinerea. Plant Sci. 283, 266–277. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2019.01.024

Dalle-Donne, I., Rossi, R., Giustarini, D., Colombo, R., Milzani, A. (2007). S-glutathionylation in protein redox regulation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 43, 883–898. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.06.014

Dey, S., Corina Vlot, A. (2015). Ethylene responsive factors in the orchestration of stress responses in monocotyledonous plants. Front. Plant Sci. 6, 640. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00640

Dixon, R. A., Achnine, L., Kota, P., Liu, C. J., Reddy, M. S., Wang, L. (2002). The phenylpropanoid pathway and plant defense-a genomics perspective. Mol. Plant Pathol. 3, 371–390. doi: 10.1046/j.1364-3703.2002.00131.x

Dombrecht, B., Xue, G. P., Sprague, S. J., Kirkegaard, J. A., Ross, J. J., Reid, J. B., et al. (2007). MYC2 differentially modulates diverse jasmonate-dependent functions in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 19, 2225–2245. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.048017

Duan, L., Liu, H., Li, X., Xiao, J. (2014). andWang, SMultiple phytohormones and phytoalexins are involved in disease resistance to Magnaporthe oryzae invaded from roots in rice. Physiol. Plant 152, 486–500. doi: 10.1111/ppl.12192

Erb, M., Meldau, S., Howe, G. A. (2012). Role of phytohormones in insect-specific plant reactions. Trends Plant Sci. 17, 250–259. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2012.01.003

Finiti, I., de la O. Leyva, M., Vicedo, B., Gómez-Pastor, R., López-Cruz, J., García-Agustín, P., et al. (2014). Hexanoic acid protects tomato plants against Botrytis cinerea by priming defence responses and reducing oxidative stress. Mol. Plant Pathol. 15, 550–562. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12112

Foyer, C. H., Noctor, G. (2005). Redox homeostasis and antioxidant signaling: a metabolic interface between stress perception and physiological responses. Plant Cell. 17, 1866–1875. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.033589

Foyer, C. H., Noctor, G. (2011). Ascorbate and glutathione: the heart of the redox hub. Plant Physiol. 155, 2–18. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.167569

Foyer, C. H., Noctor, G. (2013). Redox signaling in plants. Antioxid. Redox Sign. 18, 2087–2090. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5278

Garcia-Andrade, J., Ramirez, V., Flors, V., Vera, P. (2011). Arabidopsis ocp3 mutant reveals a mechanism linking ABA and JA to pathogen-induced callose deposition. Plant J. 67, 783–794. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04633.x

Ghanta, S., Bhattacharyya, D., Chattopadhyay, S. (2011). Glutathione signaling acts through NPR1-dependent SA-mediated pathway to mitigate biotic stress. Plant Signal Behav. 6, 607–609. doi: 10.4161/psb.6.4.15402

González-Bosch, C. (2018). Priming plant resistance by activation of redox-sensitive genes. Free Radical Bio Med. 122, 171–180. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.12.028

Govrin, E. M., Levine, A. (2000). The hypersensitive response facilitates plant infection by the necrotrophic pathogen Botrytis cinerea. Curr. Biol. 10, 751–757. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00560-1

Govrin, E. M., Rachmilevitch, S., Tiwari, B. S., Solomon, M., Levine, A. (2006). An elicitor from Botrytis cinerea induces the hypersensitive response in Arabidopsis thaliana and other plants and promotes the gray mold disease. Phytopathology 96, 299–307. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-96-0299

Han, X., Kahmann, R. (2019). Manipulation of phytohormone pathways by effectors of filamentous plant pathogens. Front. Plant Sci. 10, 822. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.00822

Haile, Z. M., Nagpala-De Guzman, E. G., Moretto, M., Sonego, P., Engelen, K., Zoli, L., et al. (2019). Transcriptome profiles of strawberry (Fragaria vesca) fruit interacting with Botrytis cinerea at different ripening stages. Front Plant. Sci. 10, 1131. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.01131

Heller, J., Tudzynski, P. (2011). Reactive oxygen species in phytopathogenic fungi: signaling, development, and disease. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 49, 3693–3690. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-072910-095355

Hood, M. E., Shew, H. D. (1996). Applications of KOH-aniline blue fluorescence in the study of plant-fungal interactions. Phytopathology 86, 704–708. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-86-704

Ichimura, K., Shinozaki, K., Tena, G., Sheen, J., Henry, Y., Champion, A., et al. (2002). Mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades in plants: a new nomenclature. Trends Plant Sci. 7, 301–308. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(02)02302-6

Jiang, Y., Yu, D. (2016). The WRKY57 transcription factor affects the expression of Jasmonate ZIM-domain genes transcriptionally to compromise Botrytis cinerea resistance. Plant Physiol. 171, 2771–2782. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.00747

Kang, C. H., Jung, W. Y., Kang, Y. H., Kim, J. Y., Kim, D. G., Jeong, J. C., et al. (2006). AtBAG6, a novel calmodulin-binding protein, induces programmed cell death in yeast and plants. Cell Death Differ. 13, 84–95. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401712

Kazan, K., Manners, J. M. (2009). Linking development to defense: auxin in plant-pathogen interactions. Trends Plant Sci. 14, 373–382. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2009.04.005

Kazan, K., Manners, J. M. (2013). MYC2: The master in action. Mol. Plant 6, 686–703. doi: 10.1093/mp/sss128

Khan, Z. U., Aisikaer, G., Khan, R. U., Bu, J., Jiang, Z., Ni, Z., et al. (2014). Effects of composite chemical pretreatment on maintaining quality in button mushrooms (Agaricus bisporus) during postharvest storage. Postharv. Biol. Tec. 95, 36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2014.04.001

Kim, M. C., Panstruga, R., Elliott, C., Müller, J., Devoto, A., Yoon, H. W., et al. (2002). Calmodulin interacts with MLO protein to regulate defence against mildew in barley. Nature 416, 447–451. doi: 10.1038/416447a

Kozhar, O., Peever, T. L. (2018). How does Botrytis cinerea infect red raspberry? Phytopathology 108, 1287–1298. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-01-18-0016-R

La Camera, S., L’Haridon, F., Astier, J., Zander, M., Abou-Mansour, E., Page, G., et al. (2011). The glutaredoxin ATGRXS13 is required to facilitate Botrytis cinerea infection of Arabidopsis thaliana plants. Plant J. 68, 507–519. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04706.x

Lamb, C., Dixon, R. A. (1997). The oxidative burst in plant disease resistance. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 48, 251–275. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.48.1.251

Lee, M. H., Jeon, H. S., Kim, S. H., Chung, J. H., Roppolo, D., Lee, H. J., et al. (2019). Lignin-based barrier restricts pathogens to the infection site and confers resistance in plants. EMBO J. 38, e101948. doi: 10.15252/embj.2019101948

Lehmann, S., Serrano, M., L’Haridon, F., Tjamos, S. E., Metraux, J. P. (2014). Reactive oxygen species and plant resistance to fungal pathogens. Phytochemistry 112, 54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2014.08.027

Li, X., Lewis, E. E., Liu, Q., Li, H., Bai, C., Wang, Y. (2016). Effects of long-term continuous cropping on soil nematode community and soil condition associated with replant problem in strawberry habitat. Sci. Rep. 6, 30466. doi: 10.1038/srep30466

Li, X., Sun, Y., Wang, X., Dong, X., Zhang, T., Yang, Y., et al. (2019). Relationship between key environmental factors and profiling of volatile compounds during cucumber fruit development under protected cultivation. Food Chem. 290, 308–315. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.03.140

Liu, Z., Wang, X. (2012). Changes in color, antioxidant, and free radical scavenging enzyme activity of mushrooms under high oxygen modified atmospheres. Postharv. Biol. Tec. 69, 1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2012.02.008

Liu, Y., Zhang, S. (2004). Phosphorylation of 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid synthase by MPK6, a stress-responsive mitogen-activated protein kinase, induces ethylene biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 16, 3386–3399. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.026609

Liu, S., Kracher, B., Ziegler, J., Birkenbihl, R. P., Somssich, I. E. (2015). Negative regulation of ABA signaling by WRKY33 is critical for Arabidopsis immunity towards. Botrytis Cinerea 2100 Elife 4, e07295. doi: 10.7554/eLife.07295

Liu, X., Cao, X., Shi, S., Zhao, N., Li, D., Fang, P., et al. (2018). Comparative RNA-Seq analysis reveals a critical role for brassinosteroids in rose (rosa hybrida) petal defense against Botrytis cinerea infection. BMC Genet. 19, 62. doi: 10.1186/s12863-018-0668-x

Liu, C., Chen, L., Zhao, R., Li, R., Zhang, S., Yu, W., et al. (2019). Melatonin induces disease resistance to Botrytis cinerea in tomato fruit by activating jasmonic acid signaling pathway. J. Agr. Food Chem. 67, 6116–6124. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.9b00058

Lloyd, A. J., William, A. J., Winder, C. L., Dunn, W. B., Heald, J. K., Cristescu, S. M., et al. (2011). Metabolomic approaches reveal that cell wall modifications play a major role in ethylene-mediated resistance against Botrytis cinerea. Plant J. 67, 852–868. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04639.x

Lorenzo, O., Chico, J. M., Sánchez-Serrano, J. J., Solano, R. (2004). JASMONATE-INSENSITIVE1 encodes a MYC transcription factor essential to discriminate between different jasmonate-regulated defense responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 16, 1938–1950. doi: 10.1105/tpc.022319

Lv, T., Li, X., Fan, T., Luo, H., Xie, C., Zhou, Y., et al. (2019). The calmodulin-binding protein IQM1 interacts with CATALASE2 to affect pathogen defense. Plant Physiol. 181, 1314–1327. doi: 10.1104/pp.19.01060

Ma, L., He, J., Liu, H., Zhou, H. (2018). The phenylpropanoid pathway affects apple fruit resistance to Botrytis cinerea. J. Phytopathol. 166, 206–215. doi: 10.1111/jph.12677

Martinez-Sanchez, G., Giuliani, A. (2007). Cellular redox status regulates hypoxia inducible factor-1 activity. role in tumour development. J. Exp. Clin. Canc. Res. 26, 39.

Mathys, J., De Cremer, K., Timmermans, P., Van Kerkhove, S., Lievens, B., Vanhaecke, M., et al. (2012). Genome-wide characterization of ISR induced in Arabidopsis thaliana by Trichoderma hamatum T382 against Botrytis cinerea infection. Front. Plant Sci. 3, 108. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2012.00108

Mengiste, T. (2012). Plant immunity to necrotrophs. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 50, 267–294. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-081211-172955

Miao, Y., Xu, L., He, X., Zhang, L., Shaban, M., Zhang, X. L., et al. (2019). Suppression of tryptophan synthase activates cotton immunity by triggering cell death via promoting SA synthesis. Plant J. 98, 329–345. doi: 10.1111/tpj.14222

Mottiar, Y., Vanholme, R., Boerjan, W., Ralph, J., Mansfield, S. D. (2016). Designer lignins: harnessing the plasticity of lignification. Curr. Opin. Biotech. 37, 190–200. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2015.10.009

Naikoo, M., II, Dar, M., II, Raghib, F., Jaleel, H., Ahmad, B., Raina, A., et al. (2019). Role and regulation of plants phenolics in abiotic stress tolerance: an overview. Plant Signaling Mol., 157–168. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-816451-8.00009-5

Nambeesan, S., AbuQamar, S., Laluk, K., Mattoo, A. K., Mickelbart, M. V., Ferruzzi, M. G., et al. (2012). Polyamines attenuate ethylene-mediated defense responses to abrogate resistance to Botrytis cinerea in tomato. Plant Physiol. 158, 1034–1045. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.188698

Noctor, G., Reichheld, J. P., Foyer, C. H. (2018). ROS-related redox regulation and signaling in plants. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 80, 3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2017.07.013

Nuruzzaman, M., Sharoni, A. M., Kikuchi, S. (2013). Roles of NAC transcription factors in the regulation of biotic and abiotic stress responses in plants. Front. Microbiol. 4, 248. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00248

Oliva, M., Hatan, E., Kumar, V., Galsurker, O., Nisim-Levi, A., Ovadia, R., et al. (2020). Increased phenylalanine levels in plant leaves reduces susceptibility to Botrytis cinerea. Plant Sci. 290, 110289. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2019.110289

Orozco-Cardenas, M., Ryan, C. A. (1999). Hydrogen peroxide is generated systemically in plant leaves by wounding and systemin via the octadecanoid pathway. P. Nat. Acad. Sci. 96, 6553–6557. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6553

Ouyang, Z., Liu, S., Huang, L., Hong, Y., Li, X., Huang, L., et al. (2016). Tomato SlERF.A1, SlERF.B4, SlERF.C3 and SlERF.A3, members of B3 group of ERF family, are required for resistance to Botrytis cinerea. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 1964. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01964

Parisy, V., Poinssot, B., Owsianowski, L., Buchala, A., Glazebrook, J., Mauch, F. (2007). Identification of PAD2 as a γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase highlights the importance of glutathione in disease resistance of Arabidopsis. Plant J. 49, 159–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02938.x

Patykowski, J. (2006). Role of hydrogen peroxide and apoplastic peroxidase in tomato Botrytis cinerea interaction. Acta Physiol. Plant 28, 589–598. doi: 10.1007/s11738-006-0054-6

Pauwels, L., Barbero, G. F., Geerinck, J., Tilleman, S., Grunewald, W., Pérez, A. C., et al. (2010). NINJA connects the co-repressor TOPLESS to jasmonate signalling. Nature 464, 788. doi: 10.1038/nature08854

Pesquet, E., Wagner, A., Grabber, J. H. (2019). Cell culture systems: invaluable tools to investigate lignin formation and cell wall properties. Curr. Opin. Biotech. 56, 215–222. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2019.02.001

Pieterse, C. M., Van der Does, D., Zamioudis, C., Leon-Reyes, A., Van Wees, S. C. (2012). Hormonal modulation of plant immunity. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Bi 28, 489–521. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154055

Posmyk, M. M., Kontek, R., Janas, K. M. (2009). Antioxidant enzymes activity and phenolic compounds content in red cabbage seedlings exposed to copper stress. Ecotox Environ. Safe. 72, 596–602. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2008.04.024

Rahman, I., Kode, A., Biswas, S. K. (2006). Assay for quantitative determination of glutathione and glutathione disulfide levels using enzymatic recycling method. Nat. Protoc. 1, 3159–3165. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.378

Ranjan, A., Westrick, M. N., Jain, S., Piotrowski, J. S., Ranjan, M., Kessens, K., et al. (2019). Resistance against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in soybean involves a reprogramming of the phenylpropanoid pathway and up-regulation of antifungal activity targeting ergosterol biosynthesis. Plant Biotechnol. J. 17, 1–15. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13082

Sanchez-Vallet, A., Ramos, B., Bednarek, P., López, G., Piślewska‐Bednarek, M., Paul Schulze‐Lefert, P., et al. (2010). Tryptophan-derived secondary metabolites in Arabidopsis thaliana confer non-host resistance to necrotrophic Plectosphaerella cucumerina fungi. Plant J. 63 (1), 115–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04224.x

Sham, A., Al-Ashram, H., Whitley, K., Iratni, R., El-Tarabily, K.A., buQamar, S.F. (2019). Meta-transcriptomic analysis of multiple environmental stresses identifies RAP2.4 gene associated with Arabidopsis immunity to Botrytis cinerea. Sci. Rep. 9, 1–15. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-53694-1

Sibout, R., Eudes, A., Mouille, G., Pollet, B., Lapierre, C., Jouanin, L., et al. (2005). CINNAMYL ALCOHOL DEHYDROGENASE-C and -D are the primary genes involved in lignin biosynthesis in the floral stem of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 17, 2059–2076. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.030767

Smirnoff, N. (2007). “Ascorbate, tocopherol and carotenoids: metabolism, pathway engineering and functions,” in Antioxidants and Reactive Oxygen Species in Plants. Ed. Smirnoff, N. (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd).

Survila, M., Davidsson, P. R., Pennanen, V., Kariola, T., Broberg, M., Sipari, N., et al. (2016). Peroxidase-generated apoplastic ROS impair cuticle integrity and contribute to DAMP-elicited defenses. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 1945. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01945

Takabatake, R., Karita, E., Seo, S., Mitsuhara, I., Kuchitsu, K., Ohashi, Y. (2007). Pathogen-induced calmodulin isoforms in basal resistance against bacterial and fungal pathogens in tobacco. Plant Cell Physiol. 48, 414–423. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcm011

Thines, B., Katsir, L., Melotto, M., Niu, Y., Mandaokar, A., Liu, G., et al. (2007). JAZ repressor proteins are targets of the SCF COI1 complex during jasmonate signalling. Nature 448, 661. doi: 10.1038/nature05960

Thomma, B. P. (2003). Alternaria spp.: from general saprophyte to specific parasite. Mol. Plant Pathol. 4, 225–236. doi: 10.1046/j.1364-3703.2003.00173.x

Torres, M. A., Jones, J. D., Dangl, J. L. (2006). Reactive oxygen species signaling in response to pathogens. Plant Physiol. 141, 373–378. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.079467

van Kan, J. A. (2006). Licensed to kill: the lifestyle of a necrotrophic plant pathogen. Trends Plant Sci. 11, 247–253. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2006.03.005

Wang, H., Hu, Y., Pan, J., Yu, D. (2015). Arabidopsis VQ motif-containing proteins VQ12 and VQ29 negatively modulate basal defense against Botrytis cinerea. Sci. Rep. 5, 14185. doi: 10.1038/srep14185

Wang, D., Huang, J., He, Y., Zhou, G., Liu, S., Chai, G. (2018). Arabidopsis NIMIN1,2 mediate redox homeostasis and JA/ET pathways to modulate Botrytis cinerea resistance. Oil Crop Sci. 3, 63. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2096-2428.2018.01.008

Wang, Y., Ji, D., Chen, T., Li, B., Zhang, Z., Qin, G., et al. (2019). Production, signaling, and scavenging mechanisms of reactive oxygen species in fruit-pathogen interactions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 2994. doi: 10.3390/ijms20122994

Wei, Y., Zhou, D., Peng, J., Pan, L., Tu, K. (2017). Hot air treatment induces disease resistance through activating the phenylpropanoid metabolism in cherry tomato fruit. J. Agr. Food Chem. 65, 8003–8010. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b02599

Williams, B., Kabbage, M., Kim, H. J., Britt, R., Dickman, M. B. (2011). Tipping the balance: Sclerotinia sclerotiorum secreted oxalic acid suppresses host defenses by manipulating the host redox environment. PLoS Pathog. 7, e1002107. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002107

Williamson, B., Tudzynski, B., Tudzynski, P., Van Kan, J. A. (2007). Botrytis cinerea: the cause of grey mould disease. Mol. Plant Pathol. 8, 561–580. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2007.00417.x

Windram, O., Madhou, P., McHattie, S., Hill, C., Hickman, R., Cooke, E., et al. (2012). Arabidopsis defense against Botrytis cinerea: chronology and regulation deciphered by high-resolution temporal transcriptomic analysis. Plant Cell 24, 3530–3557. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.102046

Yang, K. Y., Liu, Y., Zhang, S. (2001). Activation of a mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway is involved in disease resistance in tobacco. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 98, 741–746. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.2.741

Zhang, H., Hong, Y., Huang, L., Li, D., Song, F. (2016). Arabidopsis AtERF014 acts as a dual regulator that differentially modulates immunity against Pseudomonas syringae pv tomato and Botrytis cinerea. Sci. Rep. 6, 30251. doi: 10.1038/srep30251

Zhang, S., Wang, L., Zhao, R., Yu, W., Li, R., Li, Y., et al. (2018). Knockout of SlMAPK3 reduced disease resistance to Botrytis cinerea in tomato plants. J. Agr. Food Chem. 66, 8949–8956. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b02191

Keywords: cucumber, B. cinerea, resistant, redox status, signaling pathway

Citation: Yang Y, Wang X, Chen P, Zhou K, Xue W, Abid K and Chen S (2020) Redox Status, JA and ET Signaling Pathway Regulating Responses to Botrytis cinerea Infection Between the Resistant Cucumber Genotype and Its Susceptible Mutant. Front. Plant Sci. 11:559070. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.559070

Received: 06 May 2020; Accepted: 04 September 2020;

Published: 25 September 2020.

Edited by:

Aardra Kachroo, University of Kentucky, United StatesReviewed by:

Zhao Zhang, China Agricultural University, ChinaAnn Powell, University of California, Davis, United States

Copyright © 2020 Yang, Wang, Chen, Zhou, Xue, Abid and Chen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shuxia Chen, c2h1eGlhY2hlbkBud3N1YWYuZWR1LmNu

Yuting Yang

Yuting Yang Xuewei Wang1

Xuewei Wang1