94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Plant Sci. , 16 November 2020

Sec. Crop and Product Physiology

Volume 11 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2020.533767

Uridine diphosphate glucose pyrophosphorylase (UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase, UGPase), as one of the key enzymes in polysaccharide synthesis, plays important roles in the growth and development of plants. In this study, the DoUGP gene of Dendrobium officinale was overexpressed. The expression of DoUGP and genes playing roles in the same and other saccharide synthesis pathways was determined, and the total soluble polysaccharide was also tested in wild-type and transgenic seedlings. We also performed freezing and osmotic stress treatments to determine whether overexpression of DoUGP could influence stress resistance in transgenic seedlings. Results showed that mRNA expression levels of DoUGP and its metabolic upstream and downstream genes in the transgenic seedlings were increased compared to the expression of these genes in wild-type seedlings. Additionally, most CSLA genes involved in the biosynthesis of mannan polysaccharides were significantly upregulated. The total polysaccharide and mannose content of transgenic seedlings were increased compared to the content of wild type, and enhanced stress tolerance was found in the overexpressed seedlings compared to the wild type.

Dendrobium officinale is an important and endangered species. This orchid is valued for its beautiful flower and significant medicinal value (Harriman, 2010; Yongsun and Wenhong, 2011; Xia et al., 2012; Luo et al., 2017). D. officinale has a long history of being used as a traditional Chinese medicine (Meng et al., 2013). Modern medicinal research has proven that D. officinale contains a number of bioactive substances, such as polysaccharides, phenols, alkaloids, and amino acids that have been widely used to alleviate rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes, obesity, and many other diseases (Xing et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2016). Among these substances, polysaccharides, which are the most important medicinal substances of D. officinale, attract many researchers’ attention. Recently, polysaccharides have been proven to have positive effects on the improvement of antioxidant activity and alleviation of colitis, pulmonary fibrosis, and apoptosis (Huang et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2017a; Chen et al., 2018a; Liang et al., 2018a). What is more, the bioactivities, composition, structure, and physicochemical properties of polysaccharides from Dendrobium have been well defined (Wei et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2016; Ma et al., 2018), and a number of critical genes related to polysaccharide synthesis have been characterized as well, such as uridine diphosphate glucose pyrophosphorylases (UGPases), sucrose-phosphate synthases (SPSs), sucrose synthases (SuSys), and glycosyltransferases (GTs) including cellulose synthase like A (CSLAs) genes (He et al., 2015; Yan et al., 2015; Shen et al., 2017). However, systemic study on the polysaccharide biosynthesis pathway is still limited in D. officinale.

GTs are a very widespread group of carbohydrate-active-related enzymes, and participate in glycan and glycoside biosynthesis in higher plants (Shen et al., 2017). Several lines of evidence have demonstrated that the CSLA family plays important roles in the biosynthesis of mannan polysaccharides in many plant species. For example, CSLA genes from guar (Cyamopsis tetragonolobus), Arabidopsis, and poplar (Populus trichocarpa) are capable of producing β-mannan polysaccharides (Dhugga et al., 2004; Liepman et al., 2005; Suzuki et al., 2006; Goubet et al., 2009; He et al., 2015). In higher plants, sucrose metabolism is mainly catalyzed by SPS and SuSy. SPSs promote sucrose synthesis, and UGPases produce glucose-1-phosphate (Glc-1-P) using SuSy-synthesized uridine diphosphate glucose (UDP-Glc). In D. officinale, it has been revealed that increased polysaccharide content is directly correlated with the reduced sugar content in the cell, and this process is thought to be mediated by sucrose invertase and SPS. However, this hypothesis requires further investigation (Kleczkowski et al., 2004; Yan et al., 2015). The medicinal values of D. officinale mainly depend on the polysaccharide quality and quantity; therefore, more effort is required to elucidate the functions of these genes in D. officinale.

UGPases catalyze reversible production of UDP-Glc and Glc-1-P and uridine triphosphate (Kleczkowski, 1994). Studies have shown that UGPases are key enzymes in the synthesis of structural or storage polysaccharides including some active ones such as pullulan (Wu et al., 2002; Kleczkowski et al., 2004; Lian et al., 2012; Zhu et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2017b). However, studies on UGPase genes (UGPs) in D. officinale are still limited. It has been known that DoUGP is universally expressed in almost all organs especially in the stems of D. officinale (Wan et al., 2017). However, does DoUGP influence the polysaccharide content or growth of D. officinale like UGP genes in other plants? If so, are other genes involved in the process? Are there any other functions, such as stress tolerance, related with DoUGP? These questions remain to be unanswered.

In this study, to know more about the function of DoUGP, DoUGP was overexpressed in D. officinale, and then, the polysaccharide content, biomass, and stress tolerance were investigated. Polysaccharide content assays indicated that the overexpression of DoUGP has a positive effect on D. officinale biomass accumulation and stress tolerance. Our study may provide solutions for quality improvement of the important medicinal plant D. officinale and contribute to further understanding of the function of the key gene, DoUGP, in polysaccharide synthesis.

Primary protocorms generated from D. officinale seeds were used as explants for the transformations. For sterilization, wild-type protocorms were treated with 75% (v/v) ethanol for 30 s followed by the treatment of 0.1%(w/v) HgCl2 for 5 min. Protocorms were maintained and subcultured on a solidified MS (Murashige and Skoog, 1962) basal salt medium (Phyto Technology Laboratories®, Lenexa, KS) containing 30 g L–1 of sucrose, 5 g L–1 of plant agar (gel strength >1,100 g cm–2) (Duchefa Biochemie, Haarlem, Netherlands), 20 g L–1 of ground potato, 0.5 mg L–1 of 1-naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA), 1 mg L–1 of 6-benzylaminopurine (6-BA), and adjusted pH to 5.8. For the ground potato, 20 g of fresh potato tubers were pureed in a blender and then used for medium preparation without filtering. Protocorms were cultured at 25°C with cool fluorescent white light (Panasonic, Osaka, Japan) at an intensity of 70–90 μmol m2 s–1 and a 14 h photoperiod. These culture conditions were used for all stages of tissue culture except as described below. The co-cultivation medium was prepared by supplementing MS with sucrose, ground potato, and 100 μM acetosyringone (AS) without any plant growth regulators. Selection medium was prepared by supplementing MS medium with 30 g L–1 of sucrose, 5 g L–1 of agar, 20 g L–1 of ground potato, 0.2 mg L–1 of NAA, 1 mgL–1 of 6-BA, 20 mg L–1 of hygromycin B, and 500 mg L–1 of cefotaxime, and adjusted pH to 5.8. When the medium was prepared, pH was adjusted with 10% (w/v) KOH, all antibiotics were added after autoclaving at 121°C for 20 min, and all growth regulators were added before autoclaving. Except for those reagents described above, all other reagents were provided by Solarbio, Beijing, China.

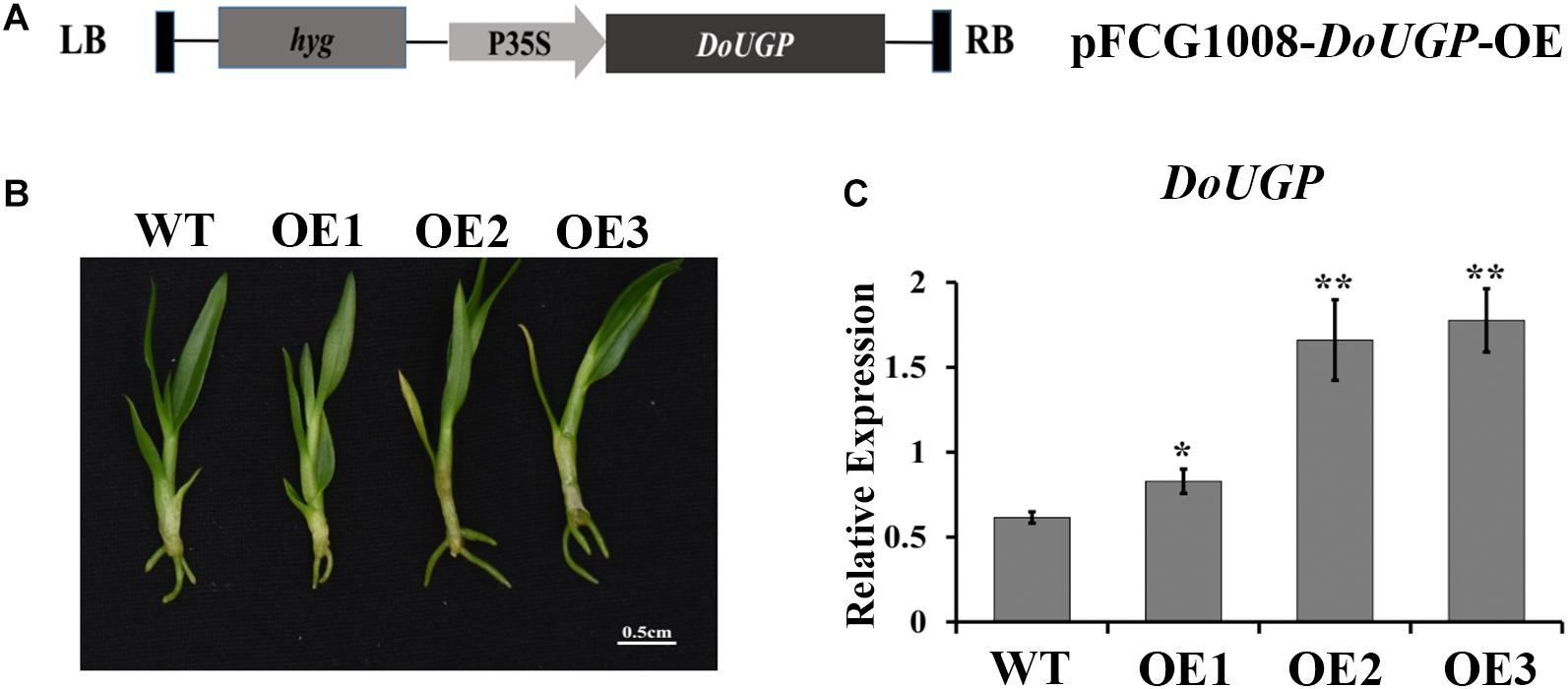

The DoUGP overexpression construct (DoUGP OE) (Figure 1A) (gene bank ID: KF711982.1) was used for this study. The plasmid was transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101 (Chan et al., 1993). When the A. tumefaciens culture OD600 reached 0.8, the cells were collected by centrifugation at 3,000 × g for 10 min. Before infection, the pellets were re-suspended in a liquid MS basal salt and adjusted to OD600 of 0.6. Two-month-old protocorms (Supplementary Figure S1) were used for A. tumefaciens-mediated transformation. When performing infections, the protocorms were incubated in the A. tumefaciens suspension at 28°C for 30 min with agitation at 50 rpm on a shaker. After infection, the protocorms were transferred to filter papers to remove spare liquid.

Figure 1. Transformation and verification of DoUGP over-expression plants. (A) Construction of recombinant expression vector pFGC1008–DoUGP–OE. (B) Morphology of wild-type and three independent transgenic DoUGP overexpression lines (OE1–OE3). (C) DoUGP mRNA expression levels in wild-type and transgenic lines. Results are presented as mean ± standard error calculated from three biological replicates. Asterisks indicate the statistically significant differences (Student’s t-test, p < 0.05).

The infected protocorms were transferred onto the top of a cocultivation medium containing 100 μM AS (Supplementary Figure S1). After cocultivation at 20°C for 4 days, about 30 protocorms per plate were placed on each selection medium (MS supplemented with 30 g L–1 of sucrose, 5 g L–1 of agar, 20 g L–1 of ground potato, 0.2 mg L–1 of NAA, 1 mg L–1 of 6-BA, 20 mg L–1 of hygromycin B, 500 mg L–1 of cefotaxime, pH 5.8). After about 60 days, the surviving green transformants were counted and imaged for statistical analysis (Supplementary Figure S1). Then, these protocorms were transferred onto a regeneration medium (MS medium supplemented with 30 g L–1 of sucrose, 5 g L–1 of agar, 20 g L–1 of ground potato, 0.2 mg L–1 of NAA, and 1 mg L–1 of 6-BA, pH 5.8). For wild-type protocorms, the same medium, but without hygromycin, was used.

Total RNA from the wild-type and three independent overexpression lines was extracted using 100 μg of 12-month-old plants by using an EASYspin Plus RNA extraction kit (Aidlab, Beijing, China), and cDNA was synthesized using a first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo, Waltham, MA, United States). Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using SsoFast EvaGreen Supermix and CFX96 (TaKara, Dalian, China) to evaluate the expression levels of DoUGP and its metabolic upstream and downstream genes in the wild-type and transgenic plants. Transcript levels were normalized against glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). The cDNA was amplified under the following cycling conditions: (1) one cycle of 95°C for 30 s; (2) 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, 55°C for 15 s, and 72°C for 15 s; and (3) melt-curve from 65°C to 95°C by 5 s per step with a 0.5°C increment. The sequences of gene-specific primers used for the amplifications are listed in Supplementary Table S1. Results are presented as mean ± standard error calculated from three biological replicates.

Three grams of shoots from fresh wild-type and two independent transgenic D. officinale seedlings were ground with a mortar at room temperature and suspended in 20 ml of distilled water. The suspended samples were heated in a water bath at 80°C for 2 h. Then the supernatant was collected by centrifugation at 6,000 × g for 5 min and mixed with 20 ml of distilled water. The sediment was used for further polysaccharide extraction by repeating heating, suspending, and centrifugation operation steps for another two times. The crude polysaccharide solutions from three extractions were mixed well. Ethanol was added to each 5 ml of collected supernatant to the final volume of 25 ml. Then the well-mixed solution was allowed to stand for polysaccharide precipitation at 4°C for 24 h. Precipitate was collected by centrifugation at 6,000 × g for 10 min. Collected precipitate was dissolved with hot water (60°C). Then the polysaccharide in the prepared solution was determined by sulfuric acid (80%)–anthrone (0.1%) colorimetry with UV spectrophotometer (UV765, Shanghai, China) at 620 nm, and glucose (0.1 mg L–1) was used to build the standard curves (Li et al., 2016). Results are presented as mean ± standard error calculated from three biological replicates.

Cellulose contents were measured, as described previously (Wang et al., 2020). Mature leaf samples (>0.3 g) from 6-month-old wild type and three independent transgenic D. officinale seedlings were homogenized with 80% (v/v) ethanol with a mortar at room temperature followed by centrifugation. Then the crude extraction was digested with sulfuric acid. Cellulose contents were determined by using a cellulose detection kit (Suzhou Comin biotechnology, Suzhou, China). Results are presented as mean ± standard error calculated from three biological replicates.

Stems of 18-month-old wild-type and three independent transgenic D. officinale seedlings were dried at 80°C until constant weight. Then the dried stems were grounded to powder with a mortar at room temperature. Around 0.3 g of dry powder was used to extract water-soluble polysaccharides, which were then analyzed by using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) according to the reported method (He et al., 2018). Briefly, the powder of each sample was pre-extracted with 80% ethanol at 80°C for 2 h. This process was repeated twice to further remove monosaccharides, oligosaccharides, and ethanol-soluble materials. Then, the water-soluble polysaccharides were extracted with double-distilled water at 100°C for 2.5 h. The extraction was hydrolyzed with 3 M HCl, derivatized with 1-phenyl-3-methyl-5-pyrazolone (PMP), and monosaccharide content was analyzed by using HPLC.

Metabolite extraction, HPLC-MS/MS analysis, metabolite identification and quantification, and data analysis were performed according to the protocol of the laboratory (Novogene Bioinformatics Technology Co., Ltd.). Briefly, 100 mg stems were collected and ground with liquid nitrogen. Then the homogenate was resuspended with prechilled 500 μl of 80% ethanol and 0.1% formic acid by well vortexing. After being centrifugated at 15,000 rpm at 4°C for 10 min, the supernatant was diluted to the final concentration containing 53% methanol and injected into the LC-MS/MS system for analysis. HPLC-MS/MS analyses were carried out using an ExionLC AD system (SCIEX) coupled with a QTRAP 6500+ mass spectrometer (SCIEX) in positive and negative ion modes, respectively. Metabolite identification was based on Q1, Q3, retention time, decluttering potential, and collision energy, and Q3 was used for metabolite quantification. The original data files were processed using the SCIEX OS Version 1.4 to integrate and correct the peak. These metabolites were annotated using the KEGG database1, HMDB database2, and Lipidmaps database3.

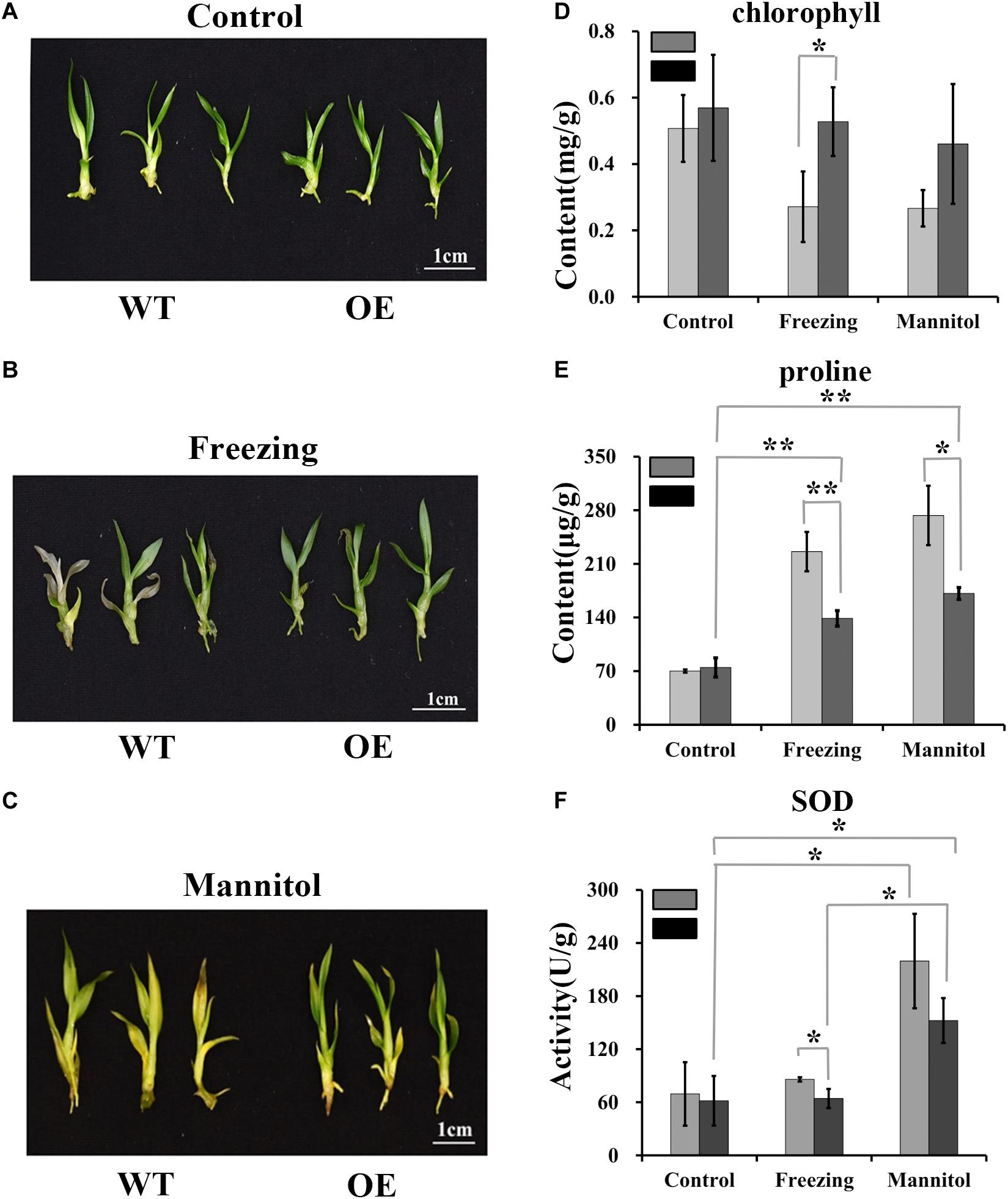

To determine the effects of different stress on transgenic D. officinale, plants of wild-type and three independent overexpression lines with a height of 2–3 cm were selected and cultured in a medium supplemented with mannitol (500 mM) for osmotic stress treatment. Freezing treatment was performed by treating plants at −20°C for 1 h. Ten or Twenty days after freezing or osmotic treatment, plants were harvested for chlorophyll and proline content and SOD enzyme activity tests. Results are presented as mean ± standard error calculated from three biological replicates.

To test the chlorophyll content, fully expanded leaf samples from fresh wild-type and three independent transgenic D. officinale seedlings were homogenized with 95% (v/v) ethanol with a mortar at room temperature followed by centrifugation. The absorbance was measured at 665 and 649 nm for chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b, respectively, using an ultraviolet spectrophotometer (UV765, Shanghai, China). Proline content was determined by using the acid-ninhydrin method, as described previously, with modifications (Tavakoli et al., 2016). SOD activity was assayed by measuring the inhibition of the photochemical reduction of NBT. Chlorophyll, proline, and SOD contents were determined by using materials from three independent transgenic seedlings. Results are presented as mean ± standard error calculated from three biological replicates.

All data collected from the experiments were subjected to a Student’s t-test using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporate, Remond, WA, United States).

To examine the function of DoUGP in D. officinale, in this study, we generated DoUGP overexpression of D. officinale seedlings. The DoUGP-OE construct, which is composed of a CaMV 35S-driven DoUGP cDNA (Figure 1A), was introduced into D. officinale genome and transformation frequency was up to 16.9%. To confirm whether the DoUGP was indeed overexpressed, the mRNA level of DoUGP was determined by using qRT-PCR. Three lines (Figure 1B) with increased mRNA expression levels from 1.35- to 2.89-fold were selected for further study (Figure 1C). Glc-1-P and UDP-Glc are the substrate and product of DoUGPase-mediated reaction. Metabolomics data showed that Glc-1-P was slightly decreased, and UDP-Glc was significantly increased, in the transgenic plants. This result suggests that the overexpressed DoUGP resulted in an increased UGPase activity (Supplementary Figure S2). These three transgenic lines exhibited different expression levels, which could be utilized for the analysis of the overexpression of DoUGP in D. officinale.

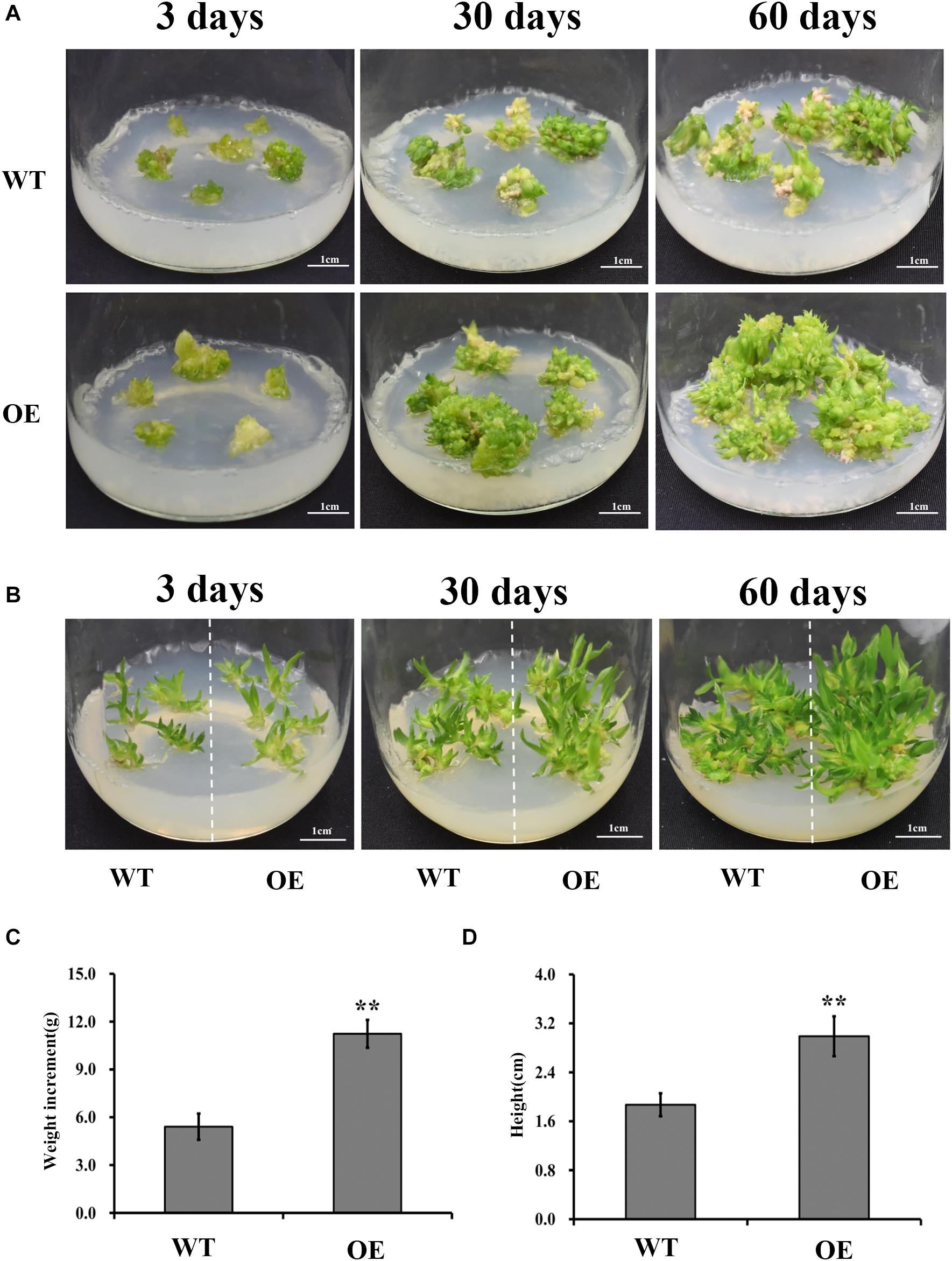

Studies have shown that UGPases, along with other polysaccharide synthesis-related enzymes, promote synthesis of structural or storage polysaccharides (Coleman et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2011). If DoUGP has a similar function as the other UGPases, increased biomass is expected in DoUGP overexpression transgenic seedlings. Therefore, we investigated the growth of transgenic and wild-type D. officinale plants at different stages (3, 30, and 60 days after transplanting) by measuring the biomass of protocorms, and seedlings were determined. Interestingly, both higher growth rate and increased biomass of protocorms were observed in the transgenic seedlings compared to the wild-type ones after 3, 30, and 60 days after transplanting (Figure 2A and Supplementary Figure S3). Similar results were observed in the wild-type and transgenic seedlings on 3, 30, and 60 days after transplanting (Figure 2B and Supplementary Figure S3). Moreover, the weight of protocorms and the height of seedlings were around twofold of the corresponding ones of wild-type (Figures 2C,D) after 60 days. Based on these results, we concluded that the overexpression of DoUGP may increase the biomass of D. officinale at both the protocorm and seedling stages.

Figure 2. Growth performance of DoUGP overexpression (OE3) plants. Protocorms (A) and seedlings (B) were imaged when they were cultivated on MS medium for 3, 30, and 60 days, respectively. For weight (C) measurement, during 60 days, weight increment of protocorms from three independent culture flasks were investigated. For height (D) measurement, seedlings from three independent culture flasks were investigated after 60 days. Results are presented as mean ± standard error calculated from three biological replicates. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences.

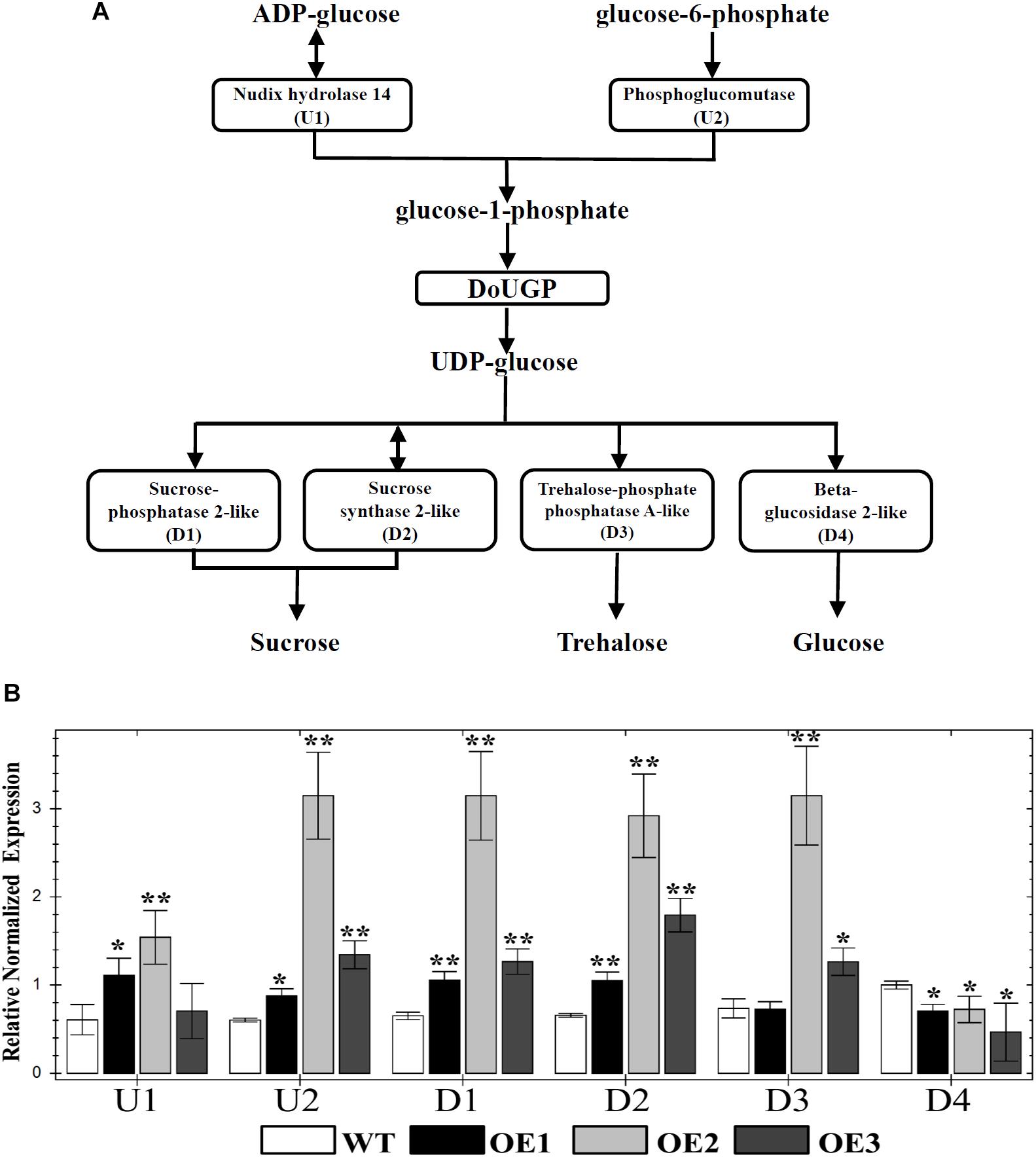

It has been well studied that UGP genes play roles in the sucrose and starch biosynthesis pathway (Kleczkowski, 1994). UGPases catalyze the production of UDP-glc and pyrophosphate from Glc-1-P and uridine triphosphate (Kleczkowski, 1994). In some cases, increased activity of a single enzyme may have an effect on the up- and downstream enzyme activities or gene expression levels of other members of a pathway. However, in other cases, the increased enzyme activities may not affect the expression levels of the genes in the same pathway. To further investigate whether the metabolism-related genes are affected by DoUGP overexpression, we chose several critical genes (U1, nudix hydrolase 14; U2, phosphoglucomutase; D1, sucrose-phosphatase 2-like; D2, sucrose synthase 2-like; D3, trehalose-phosphate phosphatase A-like and D4, beta-glucosidase 2-like) through the KEGG database4. The positions of these genes in the pathway related to DoUGP are shown in Figure 3A. qRT-PCR results showed that except D4, which was slightly decreased, the other genes were all dramatically increased in all three transgenic lines compared to the ones in the wild-type plants (Figure 3B). These results imply that the overexpressed DoUGP alters the expression of the genes in the same pathway, thereby, overexpressed DoUGP affects the pathway.

Figure 3. Quantitative real-time (qRT)-PCR analysis of up/downstream genes of DoUGP in starch and sucrose metabolism pathway. (A) Starch and sucrose metabolism pathway and critical genes. (B) Relative expression levels of up/downstream genes of DoUGP in leaves of transgenic and wild-type plants. Results are presented as mean ± standard error calculated from three biological replicates. Asterisks indicate the statistically significant differences (Student’s t-test, p < 0.05).

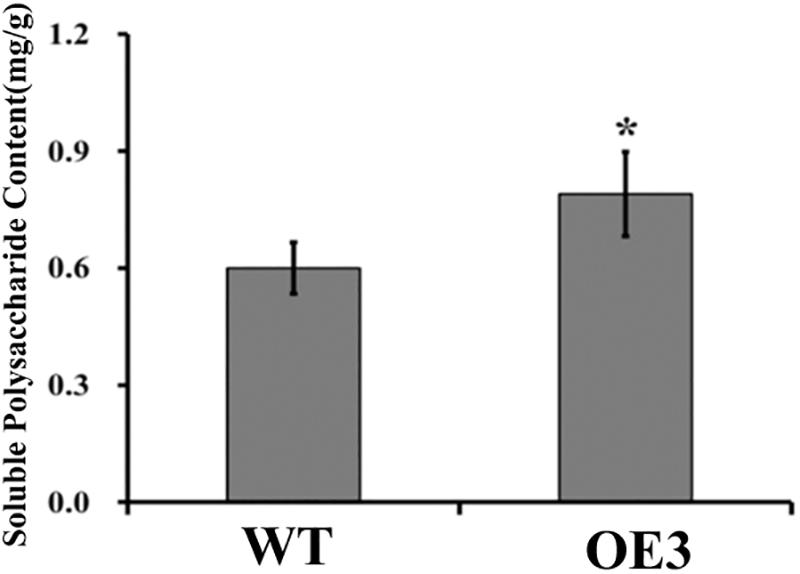

Soluble polysaccharide content is an important index for judging the medicinal value of D. officinale. As both DoUGP and CSLAs play important roles in the polysaccharide synthesis and in the stem of transgenic plants with overexpressed DoUGP, most CSLAs’ expression was significantly increased, and it is a reasonable hypothesis that polysaccharide content in the transgenic plants may be affected as well. To verify this hypothesis, the polysaccharide content of wild-type and transgenic plants was determined. When DoUGP was overexpressed, polysaccharide content was increased by 11.1% (Figure 4 and Supplementary Figure S4). Metabolomics data of monosaccharide composition of water-soluble polysaccharides in the stem of wild-type and transgenic D. officinale plants show that mannose is mainly responsible for the increased polysaccharide content in the DoUGP overexpression plants (Supplementary Table S1). However, the glucose ratio of monosaccharide composition in the transgenic plants was less compared to the one in the wild-type plants (Supplementary Table S1). These data further confirmed that DoUGP plays important roles in the polysaccharide synthesis network. UGPs have been reported to play roles in the cellulose synthesis pathway (Zhang et al., 2013). However, overexpressed DoUGP decreased the cellulose content in the transgenic plants (Supplementary Figure S5).

Figure 4. Comparison of total soluble polysaccharide contents in wild-type (WT) and DoUGP overexpresssion (OE3) plants. Results are presented as mean ± standard error calculated from three biological replicates. Asterisk indicates statistically significant differences (Student’s t-test, p < 0.05).

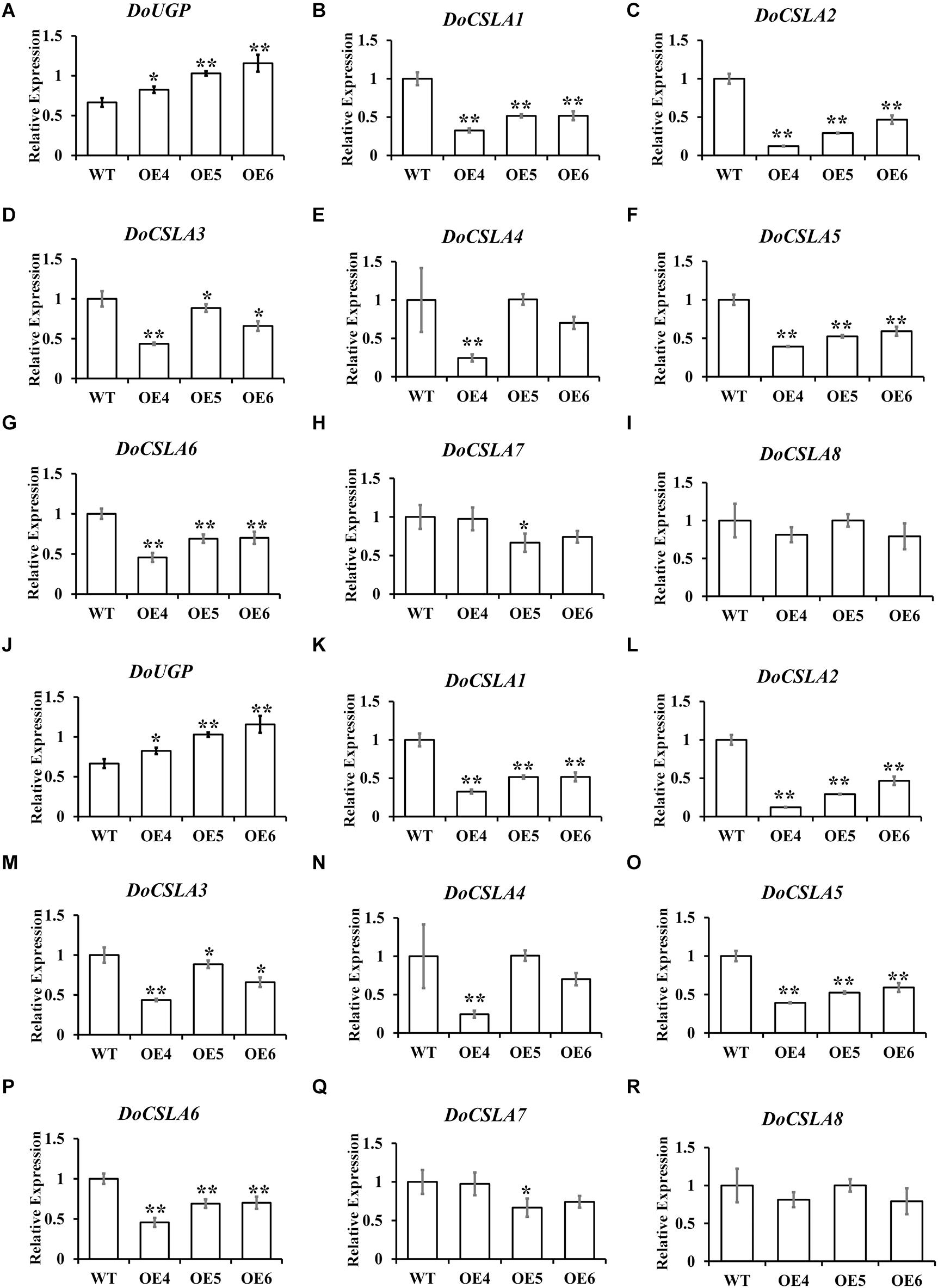

It has been proven that mannose is a major component of polysaccharides in Dendrobium species (Meng et al., 2013), and eight cellulose synthase-like A genes (CSLAs), which are likely related to the biosynthesis of bioactive mannan polysaccharides, have been identified in D. officinale (Shen et al., 2017). As the overexpression of DoUGP disturbed the expression of genes in starch and sucrose pathways, we wonder if these eight genes would be affected by the overexpression of DoUGP as well. Therefore, expression patterns of these eight CSLA genes in DoUGP overexpression plants were determined by qRT-PCR. Expression of all DoCSLA genes except DoCSLA8 significantly increased in the stem of DoUGP overexpression plants (Figures 5A–I). However, to our surprise, the expression of all DoCSLA genes except DoCSLA8 were decreased expression in the leaves of D. officinale (Figures 5J–R). These results suggest that by affecting the expression of DoCSLA genes, DoUGPase or DoUGPase-mediated metabolism may play important roles in the mannan polysaccharide synthesis network.

Figure 5. Expression levels of cellulose synthase-like A (CSLA) family genes in stems (A–I) and leaves (J–R) of DoUGP overexpression plants. Results are presented as mean ± standard error calculated from three biological replicates. Asterisks indicate the statistically significant differences (Student’s t-test, p < 0.05).

High polysaccharide content may enhance plant stress tolerance (Livingston et al., 2009; Correa-Ferreira et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2019; Zou et al., 2019). To determine whether DoUGP overexpression may confer increased stress tolerance to plants, we performed stress treatments using wild-type and transgenic plants. Freezing or osmotic stress treatment were conducted by treating the wild-type and transgenic plants with -20°C or 500 mM mannitol. Chlorophyll and proline contents and superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity were determined. Compared to the chlorophyll content of wild-type plants, after freezing treatment, the chlorophyll content of transgenic plants was 0.67-fold higher (Figure 6D). Besides, proline content decreased 0.63-fold, and there was a 0.34-fold decrease in superoxide dismutase (SOD) activities detected in the transgenic plants after freezing treatments (Figures 6E,F). After osmotic stress, a 0.59-fold reduced proline content was also detected in the transgenic plants (Figure 6E). These results suggest that the overexpressed DoUGP may enhance plant stress tolerance by increasing the polysaccharide content (Figures 6A–C).

Figure 6. Resistance of DoUGP overexpression plants to freezing and osmotic stress treatments. (A) Wild-type (WT) and DoUGP overexpression (OE) seedlings cultured without stress. (B) Wild-type (WT) and DoUGP overexpression seedlings treated at -20°C for 1 h and cultured for another 10 days. (C) Wild-type (WT) and DoUGP overexpression seedlings treated with 500 mM mannitol for 20 days. (D) Chlorophyll contents of wild-type (gray bar) and DoUGP overexpression (black bar) seedlings after freezing or osmotic stress treatments. (E) Proline contents of wild-type and DoUGP overexpression seedlings after freezing or osmotic stress treatments. (F) SOD activities after freezing or osmotic stress treatments. Chlorophyll, proline, and SOD contents were determined by using mixed materials from three independent transgenic seedlings. Results are presented as mean ± standard error calculated from three biological replicates. Asterisks indicate the statistically significant differences (Student’s t-test, p < 0.05).

D. officinale is a traditional but endangered Chinese orchid. As an important component of D. officinale, polysaccharide has significant positive effects such as antioxidation, acute colitis, pulmonary fibrosis, and apoptosis (Zhao et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2018a; Liang et al., 2018b, 2019). In order to improve the polysaccharide yield of D. officinale, agricultural and polysaccharide processing approaches such as fertilizer application and optimized polysaccharide extraction and dehydration methods have been applied (He et al., 2018; Qian et al., 2018). However, so far, no satisfactory results have been achieved. Since some genes, such as UGP, SPS, SuSy, GTs, and CSLA (He et al., 2015; Yan et al., 2015; Shen et al., 2017), related to polysaccharide synthesis have been characterized, enhancing the expression of these genes may be a direct and efficient solution for polysaccharide yield and quality improvement in D. officinale. Therefore, in this study, we overexpressed the DoUGP gene of D. officinale aiming to obtain a higher polysaccharide content in transgenic plants. To our surprise, besides the expected polysaccharide content increase, the transgenic plants exhibited improved biomass and stress tolerance, as well, which are important agricultural traits. These phenotypes have not been found in transgenic plants only containing a vector (Li et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2018b). Therefore, we are confident that the increased biomass and enhanced stress tolerance, along with the increased polysaccharide contents, were due to the DoUGP overexpression. We suppose these improvements were due to the accumulated polysaccharide, which promotes plant growth and enhances osmotic pressure tolerance.

In this study, we also found that when DoUGP was overexpressed, some of the key genes in the same pathway were significantly affected. Surprisingly, among the four downstream genes, three of them were upregulated; nevertheless, beta-glucosidase 2-like gene was downregulated (Figure 3B). This result indicates that these four genes may have other functions in different ways at least when working along with DoUGP. We also noticed that upregulation of these genes such as nudix hydrolase 14 gene and sucrose phosphatase 2-like gene was not consistently related to DoUGP overexpression levels. This phenomenon could be explained by the regulation of nudix hydrolase 14 and sucrose phosphatase 2-like genes by DoUGP that was in a fine tuned way. Moreover, we also noticed that in the stem, most of the CSLA genes in the mannan polysaccharide synthesis pathway were upregulated (Figures 5A–I), which is consistent with the increased total soluble polysaccharide content (Figure 4). Besides, the increased expression of most of the CSLA genes is also consistent with the promoted ratio of mannan to total soluble polysaccharide in the stem (Supplementary Table S1). Although the monosaccharide composition of water-soluble polysaccharide data indicated that the relative ratio of glucose in the DoUGP-OE transgenic plants was decreased compared to the one of WT, given the increased polysaccharide content resulting by the overexpressed DoUGP, the absolute glucose content in the transgenic plants was not less than the one of WT. However, in the leaves of DoUGP-OE transgenic plants, the expression of CSLA genes was significantly downregulated, which indicates that the overexpression of DoUGP affected the CSLA gene expression in a tissue-dependent way (Figures 5J–R). This implies that in the D. officinale, the polysaccharide metabolism network is complex and requires more effort to elucidate it.

The reason we started with DoUGP is to learn about the underlying mechanisms of polysaccharide synthesis in D. officinale and apply this knowledge to improve the polysaccharide content in these plants. In other plants, the UGPs have been reported to play roles in the cellulose synthesis pathway (Zhang et al., 2013). However, in our case, instead of an increase in cellulose content, overexpressed DoUGP resulted in the increased total soluble polysaccharides (Supplementary Figure S5). This result indicates that studies on DoUGP are important for D. officinale, as the soluble polysaccharide content is critical for the medicinal use of D. officinale. For medicinal use, D. officinale plants of 2–4 years old are regarded most appropriate for polysaccharide extraction, as polysaccharide content of D. officinale varies depending on age and developmental stages (Qin et al., 2018). D. officinale plants used in this study were 1-year-old young plants, which means a much higher polysaccharide content could be expected in 2–4-years-old transgenic plants. We also noticed that the stress tolerance of transgenic plants was significantly improved possibly due to the increased polysaccharide content (Figure 6).

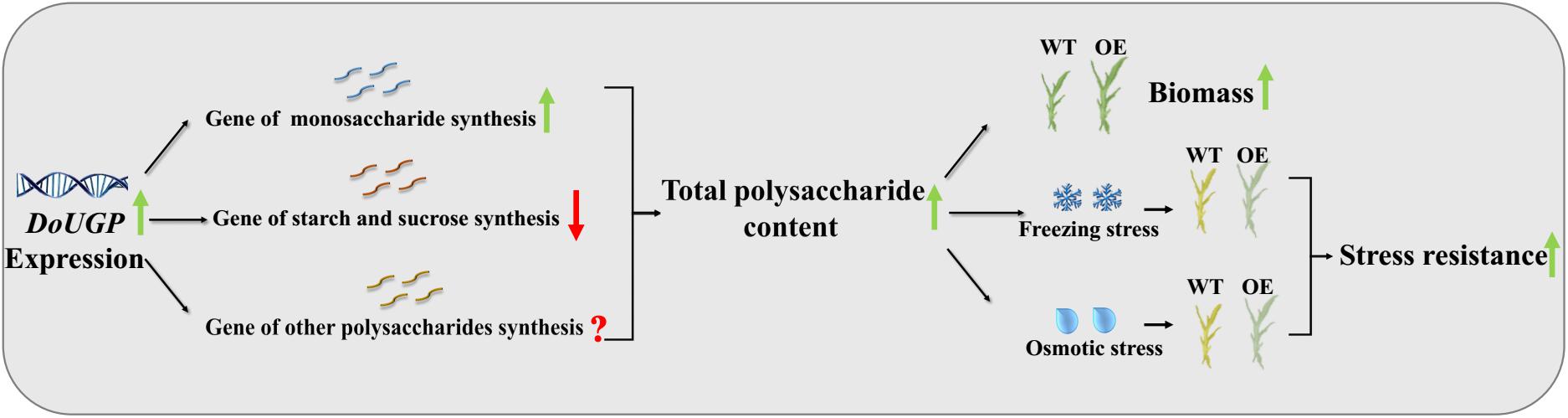

Based on the results obtained in this study, a schematic map was summarized (Figure 7). First, when DoUGP was overexpressed, some genes in the same synthesis pathway were promoted. As a result, the total polysaccharide content was increased in the transgenic plants. Besides these two polysaccharide synthesis pathways, the gene expression of other polysaccharide synthesis pathways remains unclear. Increased polysaccharide content, enhanced biomass accumulation, and improved stress resistance were obtained in DoUGP overexpression of D. officinale plants. All these traits are critical features for D. officinale breeding. We suppose that increased freezing and osmotic resistance resulting from increased polysaccharide content may be due to a better maintained intracellular osmotic pressure and freezing point. Besides, decreased proline content and SOD enzyme activity suggest that the relieved stress in the transgenic plants is due to the presence of additional polysaccharide content.

Figure 7. Schematic diagram of how DoUGP overexpression enhances biomass and promotes stress resistance of D. officinale plants.

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material.

JC, JH, and MT conceived and designed the experiments and provided funding for research work. LW and JC performed most of the experiments. LW, JH, and JC wrote the manuscript. JH, KZ, FL, and MT analyzed and commented on the data and manuscript. HL, XJ, JW, and FL performed some of the experiments. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 31501242 and 3187020624).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2020.533767/full#supplementary-material

Chan, M.-T., Chang, H.-H., Ho, S.-L., Tong, W.-F., and Yu, S.-M. (1993). Agrobacterium-mediated production of transgenic rice plants expressing a chimeric α-amylase promoter/β-glucuronidase gene. Plant Mol. Biol. 22, 491–506. doi: 10.1007/bf00015978

Chen, J., Lu, J., Wang, B., Zhang, X., Huang, Q., Yuan, J., et al. (2018a). Polysaccharides from Dendrobium officinale inhibit bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis via the TGFβ1-Smad2/3 axis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 118, 2163–2175. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.07.056

Chen, J., Wang, L., Chen, J., Huang, J., Liu, F., Guo, R., et al. (2018b). Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation system for the important medicinal plant Dendrobium catenatum Lindl. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. Plant 54, 228–239. doi: 10.1007/s11627-018-9903-4

Coleman, H. D., Ellis, D. D., Gilbert, M., and Mansfield, S. D. (2006). Up-regulation of sucrose synthase and UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase impacts plant growth and metabolism. Plant Biotechnol. J. 4, 87–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2005.00160.x

Correa-Ferreira, M. L., Viudes, E. B., de Magalhaes, P. M., Paixao de Santana Filho, A., Sassaki, G. L., Pacheco, A. C., et al. (2019). Changes in the composition and structure of cell wall polysaccharides from Artemisia annua in response to salt stress. Carbohydr. Res. 483:107753. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2019.107753

Dhugga, K. S., Barreiro, R., Whitten, B., Stecca, K., Hazebroek, J., Randhawa, G. S., et al. (2004). Guar seed ß-mannan synthase is a member of the cellulose synthase super gene family. Science 303, 363–366. doi: 10.1126/science.1090908

Goubet, F., Barton, C. J., Mortimer, J. C., Yu, X., Zhang, Z., Miles, G. P., et al. (2009). Cell wall glucomannan in Arabidopsis is synthesised by CSLA glycosyltransferases, and influences the progression of embryogenesis. Plant J. 60, 527–538. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313x.2009.03977.x

Harriman, N. A. (2010). Flora of China, Chap. 139. Vol. 25. Orchidaceae, eds Z. Wu, P. H. Raven, and D. Hong (Beijing: Science Press & St. Louis), 367–397.

He, C., Zhang, J., Liu, X., Zeng, S., Wu, K., Yu, Z., et al. (2015). Identification of genes involved in biosynthesis of mannan polysaccharides in Dendrobium officinale by RNA-seq analysis. Plant Mol. Biol. 88, 219–231. doi: 10.1007/s11103-015-0316-z

He, L., Yan, X., Liang, J., Li, S., He, H., Xiong, Q., et al. (2018). Comparison of different extraction methods for polysaccharides from Dendrobium officinale stem. Carbohyd. Polym. 198, 101–108. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.06.073

Huang, K., Li, Y., Tao, S., Wei, G., Huang, Y., Chen, D., et al. (2016). Purification, characterization and biological activity of polysaccharides from Dendrobium officinale. Molecules 21:701. doi: 10.3390/molecules21060701

Kleczkowski, L. A. (1994). Glucose activation and metabolism through UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase in plants. Phytochemistry 37, 1507–1515. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(00)89568-0

Kleczkowski, L. A., Geisler, M., Ciereszko, I., and Johansson, H. (2004). UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase. An old protein with new tricks. Plant Physiol. 134, 912–918. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.036053

Li, H., Zhang, Y., Gao, Y., Lan, Y., Yin, X., and Huang, L. (2016). Characterization of UGPase from Aureobasidium pullulans NRRL Y-12974 and application in enhanced pullulan production. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 178, 1141–1153. doi: 10.1007/s12010-015-1934-2

Li, S., Zhang, L., Wang, Y., Xu, F., Liu, M., Lin, P., et al. (2017). Knockdown of a cellulose synthase gene BoiCesA affects the leaf anatomy, cellulose content and salt tolerance in broccoli. Sci. Rep. 7, 1–14.

Lian, L., Ye, B., Chen, R., Xie, H., Zhang, J., and Chen, Y. (2012). Transformation of UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase gene (UGPase) from Saccharum officinarum into Arabidopsis thaliana and analysis of physiological characteristics of transgenic plants. J. Agric. Biotechnol. 20, 481–488.

Liang, J., Chen, S., Chen, J., Lin, J., Xiong, Q., Yang, Y., et al. (2018a). Therapeutic roles of polysaccharides from Dendrobium Officinaleon colitis and its underlying mechanisms. Carbohyd. Polym. 185, 159–168. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.01.013

Liang, J., Chen, S., Hu, Y., Yang, Y., Yuan, J., Wu, Y., et al. (2018b). Protective roles and mechanisms of Dendrobium officinal polysaccharides on secondary liver injury in acute colitis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 107, 2201–2210. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.10.085

Liang, J., Wu, Y., Yuan, H., Yang, Y., Xiong, Q., Liang, C., et al. (2019). Dendrobium officinale polysaccharides attenuate learning and memory disabilities via anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory actions. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 126, 414–426. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.12.230

Liepman, A. H., Wilkerson, C. G., and Keegstra, K. (2005). Expression of cellulose synthase-like (Csl) genes in insect cells reveals that CslA family members encode mannan synthases. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 2221–2226. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409179102

Liu, H., Chen, X., Song, L., Li, K., Zhang, X., Liu, S., et al. (2019). Polysaccharides from Grateloupia filicina enhance tolerance of rice seeds (Oryza sativa L.) under salt stress. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 124, 1197–1204. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.11.270

Livingston, D. P., Hincha, D. K., and Heyer, A. G. (2009). Fructan and its relationship to abiotic stress tolerance in plants. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 66, 2007–2023. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0002-x

Luo, D., Qu, C., Zhang, Z., Xie, J., Xu, L., Yang, H., et al. (2017). Granularity and laxative effect of ultrafine powder of Dendrobium officinale. J. Med.Food 20, 180–188. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2016.3827

Ma, H., Zhang, K., Jiang, Q., Dai, D., Li, H., Bi, W., et al. (2018). Characterization of plant polysaccharides from Dendrobium officinale by multiple chromatographic and mass spectrometric techniques. J. Chromatogr. A 1547, 29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2018.03.006

Meng, L. Z., Lv, G. P., Hu, D. J., Cheong, K. L., Xie, J., Zhao, J., et al. (2013). Effects of polysaccharides from different species of Dendrobium (Shihu) on macrophage function. Molecules 18, 5779–5791. doi: 10.3390/molecules18055779

Murashige, T., and Skoog, F. (1962). A revised medium for rapid growth and bio assays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol. Plant. 15, 473–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1962.tb08052.x

Qian, G., Wang, P., and Guo, F. (2018). The effect of different drying methods on polysaccharide content in the flash extracts of dendrobium officinale fresh product. Chin.Med. Modern Distance Educ. China 16, 101–102.

Qin, Z., Tan, X., Ning, H., Hu, J., Miao, Y., and Zhang, X. (2018). Quantification and characterization of polysaccharides from different aged Dendrobium officinale stems. Shipin Kexue/Food Science 39, 189–193.

Shen, C., Guo, H., Chen, H., Shi, Y., Meng, Y., Lu, J., et al. (2017). Identification and analysis of genes associated with the synthesis of bioactive constituents in Dendrobium officinale using RNA-Seq. Sci. Rep. 7:187.

Suzuki, S., Li, L., Sun, Y.-H., and Chiang, V. L. (2006). The cellulose synthase gene superfamily and biochemical functions of xylem-specific cellulose synthase-like genes in Populus trichocarpa. Plant Physiol. 142, 1233–1245. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.086678

Tavakoli, M., Poustini, K., and Alizadeh, H. (2016). Proline accumulation and related genes in wheat leaves under salinity stress. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 18, 707–716.

Wan, R.-L., Sun, J., He, T., Hu, Y.-D., Zhao, Y., Wu, Y., et al. (2017). Cloning cDNA and functional characterization of UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase in Dendrobium officinale. Biol. Plant. 61, 147–154. doi: 10.1007/s10535-016-0645-z

Wang, K., Li, M. Q., Chang, Y. P., Zhang, B., Zhao, Q. Z., and Zhao, W. L. (2020). The basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor OsBLR1 regulates leaf angle in rice via brassinosteroid signalling. Plant Mol. Biol. 102, 589–602. doi: 10.1007/s11103-020-00965-5

Wang, Q., Zhang, X., Li, F., Hou, Y., Liu, X., and Zhang, X. (2011). Identification of a UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase from cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) involved in cellulose biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Rep. 30, 1303–1312. doi: 10.1007/s00299-011-1042-x

Wei, W., Feng, L., Bao, W.-R., Ma, D.-L., Leung, C.-H., Nie, S.-P., et al. (2016). Structure characterization and immunomodulating effects of polysaccharides isolated from Dendrobium officinale. J. Agric. Food Chem. 64, 881–889. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b05180

Wu, X., Du, M., Weng, Y., Liu, D., and Hu, Z. (2002). UGPase of Astragalus membranaceus: cDNA cloning, analyzing and expressing in Escherichia coli. Acta Bot. Sin. 44, 689–693.

Xia, L., Liu, X., Guo, H., Zhang, H., Zhu, J., and Ren, F. (2012). Partial characterization and immunomodulatory activity of polysaccharides from the stem of Dendrobium officinale (Tiepishihu) in vitro. J. Funct. Foods 4, 294–301. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2011.12.006

Xing, X., Cui, S. W., Nie, S., Phillips, G. O., Goff, H. D., and Wang, Q. (2013). A review of isolation process, structural characteristics, and bioactivities of water-soluble polysaccharides from Dendrobium plants. Bioact. Carbohyd. Dietary Fibre 1, 131–147. doi: 10.1016/j.bcdf.2013.04.001

Yan, L., Wang, X., Liu, H., Tian, Y., Lian, J., Yang, R., et al. (2015). The genome of Dendrobium officinale illuminates the biology of the important traditional Chinese orchid herb. Mol.Plant 8, 922–934. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2014.12.011

Yongsun, C., and Wenhong, L. (2011). Optimal extraction procedure of polysaccharides from candidum dendrobium and effects of polysaccharides on overexpression of NF-κB agent in vascular endothelial cells reduced by high glucose. J. Shanxi Coll. Tradit. Chin. Med. 12, 28–31.

Zhang, G., Qi, J., Xu, J., Niu, X., Zhang, Y., Tao, A., et al. (2013). Overexpression of UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase gene could increase cellulose content in Jute (Corchorus capsularis L.). Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 442, 153–158. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.11.053

Zhang, J., He, C., Wu, K., Teixeira da Silva, J. A., Zeng, S., Zhang, X., et al. (2016). Transcriptome analysis of Dendrobium officinale and its application to the identification of genes associated with polysaccharide synthesis. Front. Plant Sci. 7:5. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00005

Zhang, J.-Y., Guo, Y., Si, J.-P., Sun, X.-B., Sun, G.-B., and Liu, J.-J. (2017a). A polysaccharide of Dendrobium officinale ameliorates H2O2-induced apoptosis in H9c2 cardiomyocytes via PI3K/AKT and MAPK pathways. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 104, 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.05.169

Zhang, K., Wu, Z., Tang, D., Luo, K., Lu, H., Liu, Y., et al. (2017b). Comparative transcriptome analysis reveals critical function of sucrose metabolism related-enzymes in starch accumulation in the storage root of sweet potato. Front. Plant Sci. 8:914. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00914

Zhao, X., Dou, M., Zhang, Z., Zhang, D., and Huang, C. (2017). Protective effect of Dendrobium officinale polysaccharides on H2O2-induced injury in H9c2 cardiomyocytes. Biomed. Pharmacother. 94, 72–78. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.07.096

Zhao, Y., Liu, Y., Lan, X.-M., Xu, G.-L., Sun, Y.-Z., Li, F., et al. (2016). Effect of Dendrobium officinale extraction on gastric carcinogenesis in rats. Evid. Based Comp. Altern. Med. 2016: 1213090.

Zhu, B.-H., Shi, H.-P., Yang, G.-P., Lv, N.-N., Yang, M., and Pan, K.-H. (2016). Silencing UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase gene in Phaeodactylum tricornutum affects carbon allocation. New Biotechnol. 33, 237–244. doi: 10.1016/j.nbt.2015.06.003

Zou, P., Lu, X., Zhao, H., Yuan, Y., Meng, L., Zhang, C., et al. (2019). Polysaccharides derived from the brown algae lessonia nigrescens enhance salt stress tolerance to wheat seedlings by enhancing the antioxidant system, and modulating intracellular ion concentration. Front. Plant Sci. 10:48. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.00048

Keywords: Dendrobium officinale, polysaccharide, DoUGP, biomass, stress resistance

Citation: Chen J, Wang L, Liang H, Jin X, Wan J, Liu F, Zhao K, Huang J and Tian M (2020) Overexpression of DoUGP Enhanced Biomass and Stress Tolerance by Promoting Polysaccharide Accumulation in Dendrobium officinale. Front. Plant Sci. 11:533767. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.533767

Received: 10 February 2020; Accepted: 07 October 2020;

Published: 16 November 2020.

Edited by:

Antonio Ferrante, University of Milan, ItalyReviewed by:

Aaron Liepman, Eastern Michigan University, United StatesCopyright © 2020 Chen, Wang, Liang, Jin, Wan, Liu, Zhao, Huang and Tian. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jin Huang, d3VkZmdAaG90bWFpbC5jb20=; Mengliang Tian, c2Vjb25kYXRAc2ljYXUuZWR1LmNu

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.