95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Plant Sci. , 25 May 2020

Sec. Plant Biotechnology

Volume 11 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2020.00652

This article is part of the Research Topic Biofuels and Bioenergy View all 14 articles

Lignin is a heterogeneous polymer of aromatic subunits derived from phenylalanine. It is polymerized in intimate proximity to the polysaccharide components in plant cell walls and provides additional rigidity and compressive strength for plants. Understanding the regulatory mechanisms of lignin biosynthesis is important for genetic modification of the plant cell wall for agricultural and industrial applications. Over the past 10 years the transcriptional regulatory model of lignin biosynthesis has been established in plants. However, the role of post-transcriptional regulation is still largely unknown. Increasing evidence suggests that lignin biosynthesis pathway genes are also regulated by alternative splicing, microRNA, and long non-coding RNA. In this review, we briefly summarize recent progress on the transcriptional regulation, then we focus on reviewing progress on the post-transcriptional regulation of lignin biosynthesis pathway genes in the woody model plant Populus.

Lignin is one of the most abundant biopolymers, accounting for ∼30% of the organic carbon in the biosphere. As a principal component of secondary cell walls, lignin provides plants with structural integrity and a response mechanism to environmental stimuli, e.g., pathogen attack. In addition, lignin supports transport of water and solutes through the vascular system. The lignin structure varies between plant species, between cell types within a single plant, and between different parts of the wall of a single cell. The lignin polymer is primarily comprised of three major monomers: p-hydroxyphenyl (H), guaiacyl (G), and syringyl (S) monolignols that are synthesized via the phenylpropanoid pathway (Raes et al., 2003). From Arabidopsis genome-wide analysis and mutant/transformation studies, at least 14 structural genes have been characterized and shown to be involved in the monolignol biosynthesis pathway (Goujon et al., 2003a).

Although the regulatory mechanism of lignin biosynthesis has been studied in several plant species (Zhong et al., 2006; Zhong and Ye, 2011; Xie et al., 2018b; Zhang et al., 2018a), many aspects of its regulation remain unresolved. Identification of cis-acting elements in monolignol biosynthetic genes provides an understanding of the transcriptional regulation of lignin biosynthesis. Promoter analysis and electrophoretic mobility shift assay have revealed that the SNBE (Zhong et al., 2010a) and AC elements (Zhong and Ye, 2011) (corresponding to the NAC and MYB transcription factor-binding motif, respectively) are necessary for coordinated monolignol pathway gene activation. However, a comprehensive understanding of the transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation of lignin biosynthesis in woody species is still lacking. In this review, we summarize the current understanding of the regulation of lignin biosynthesis pathway genes at the transcriptional level, then focus on the emerging area of post-transcriptional regulation.

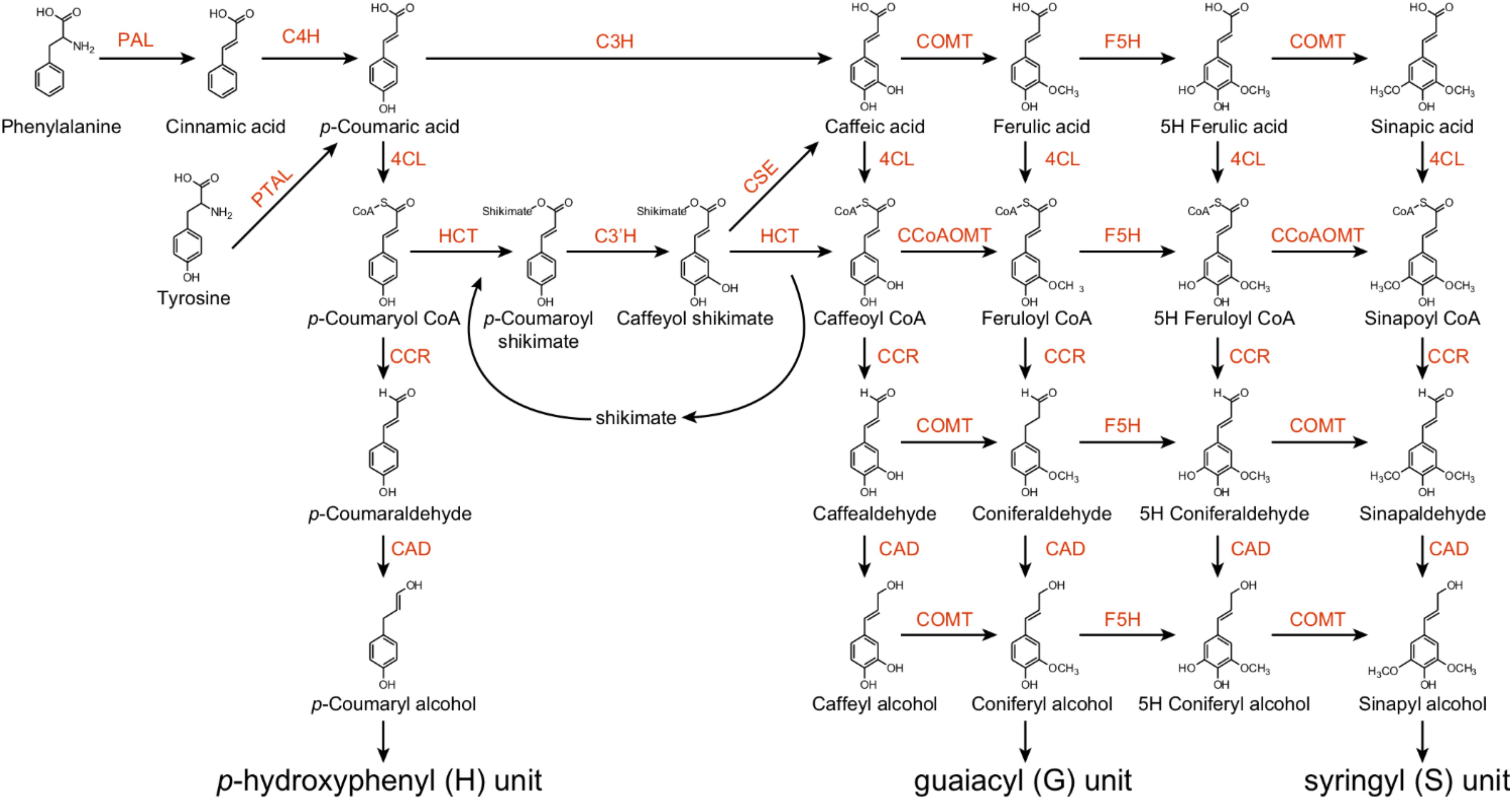

The monolignol biosynthesis pathway has been well studied in several model plant species, such as the model herbaceous species Arabidopsis and the model woody species Populus. Monolignols are synthesized from phenylalanine via the phenylpropanoid pathway, which includes a series of enzymes controlling alternate linear steps, ultimately providing precursors for numerous secondary metabolites (Fraser and Chapple, 2011). Wang et al. (2018) demonstrated the importance of phenylpropanoid biosynthetic enzymes for lignin biosynthesis in Populus using 221 independent transgenic lines derived from 21 lignin biosynthetic genes. These enzymes belong to an assembly of genes and gene families, including phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL), cinnamate 4-hydroxylase (C4H), 4-coumarate:CoA ligase (4CL), p-coumaroyl-shikimate/quinate 3-hydroxylase (C3H), hydroxycinnamoyl-CoA shikimate/quinate hydroxycinnamoyl transferase (HCT), caffeoyl-CoA O-methyltransferase (CCoAOMT), 5-hydroxyconiferyl aldehyde O-methyltransferase (AldOMT), coniferyl aldehyde/ferulate 5-hydroxylase (CAld5H/F5H), cinnamoyl-CoA reductase (CCR), cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase (CAD), caffeoyl shikimate esterase (CSE), and caffeic acid O-methyltransferase (COMT) (Figure 1). PAL, C4H and 4CL play important roles to provide precursors for various downstream metabolites (Figure 1). Down-regulation of PAL, C4H or 4CL can significantly decrease lignin content in both Arabidopsis and Populus (Rohde et al., 2004; Chen and Dixon, 2007; Vanholme et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2018). Recently, a C3H enzyme is identified as a bifunctional peroxidase that oxidizes both ascorbate and 4-coumarate in the model plants Brachypodium distachyon and Arabidopsis by directly catalyzing the 3-hydroxylation of 4-coumarate to caffeate in lignin biosynthesis pathway (Barros et al., 2019).

Figure 1. The monolignol biosynthetic pathway in Populus. PAL, L-phenylalanine ammonia-lyase; PTAL, bifunctional L-phenylalanine/L-tyrosine ammonia-lyase; C4H, cinnamate 4-hydroxylase; C3H, p-coumarate 3-hydroxylase; COMT, caffeate/5-hydroxyferulate 3-O-methyltransferase; F5H, ferulate 5-hydroxylase/coniferaldehyde 5-hydroxylase; 4CL, 4-hydroxycinnamate:CoA ligase; HCT, p-hydroxycinnamoyl CoA:shikimate/quinate hydroxycinnamoyltransferase; C3′H, p-coumaroyl shikimate/quinate 3′-hydroxylase; CSE, caffeoyl shikimate esterase; CCoAOMT, caffeoyl CoA 3-O-methyltransferase; CCR, cinnamoyl CoA reductase; CAD, cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase.

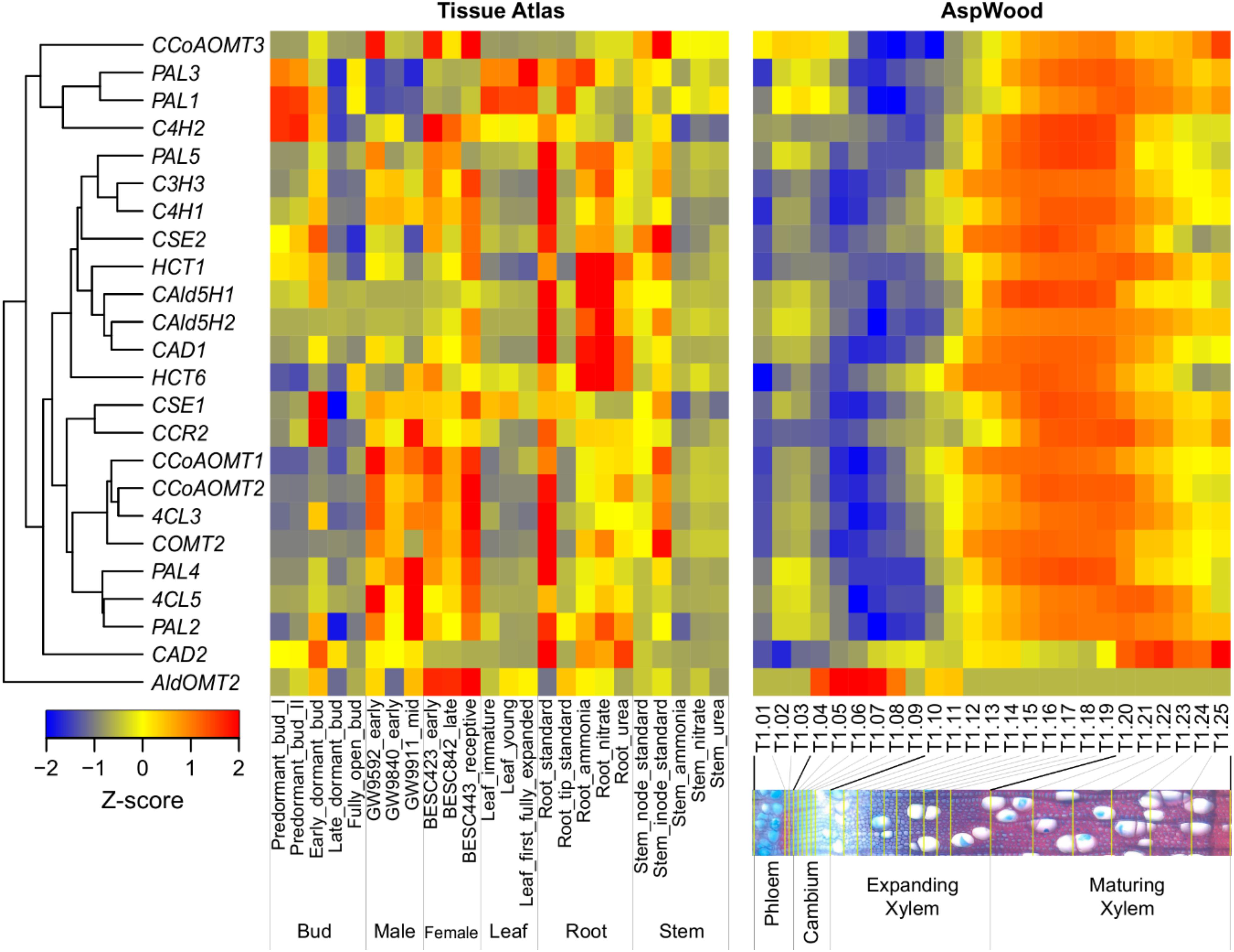

Populus is a promising feedstock for biofuels and other value-added products due to its fast growth and high efficiency of biofuel conversion. In addition, abundant public genomics, and transcriptomics resources of Populus provide the basis for functional study. Here we focus on Populus to explore the transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation of lignin biosynthetic genes. On the basis of findings reported in literature, we build a conceptual network of the enzymes that control monolignol biosynthesis in Populus. As shown in Table 1, the 21 enzymes reported by Wang et al. (2018), and three other enzymes [CSE1, CSE2 (Vanholme et al., 2013) and COMT2 (Marita et al., 2001)], play important roles in monolignol biosynthesis in Populus and Arabidopsis. We analyzed the expression profiles of the structural genes in monolignol biosynthesis pathway across various tissues and during wood formation in Populus based on the Populus Gene Expression Atlas database (different tissues of buds, male catkins, female catkins, leaf, root and stem of P. trichocarpa, 72 RNA-Seq libraries)1 and AspWood database (micro meter-scale profile of P. tremula cambial growth and wood formation, 137 RNA-Seq libraries) (Sundell et al., 2017).

Broad expression evidence from key enzymes in the lignin biosynthetic pathway provides a hypothetical foundation for their functions in various tissues. For example, Kim et al. (2019) performed a series of wood-forming tissue-specific transcriptome analyses from a hybrid poplar and identified critical pathway genes for secondary wall biosynthesis in mature developing xylem. Wood formation is a process of plant secondary growth, which originates from the cambium meristem cells, eventually forming a tree’s main stem or truck. Most of the genes involved in this process are highly expressed in the developing xylem. In contrast, CAD2 and AldOMT2 are highly expressed in maturing xylem and cambium, respectively (Figure 2). In a promoter-GUS histochemistry analysis, the GUS driven by promoter of Eucalyptus gunnii CAD2 is expressed in all lignifying cells including vessel elements, xylem fibers and paratracheal parenchyma cells of the xylem tissues in the transgenic Arabidopsis floral stem and root (Baghdady et al., 2006). The expression pattern and function of AldOMT2 homologs remains unclear.

Figure 2. Hierarchical clustering of the expression profiles of monolignol biosynthetic genes across various tissues (left) and during wood formation (right) in Populus. The expression data of different tissues and wood formation were obtained from Populus Gene Expression Atlas (https://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov/phytomine/aspect.do?name=Expression) and AspWood (http://aspwood.popgenie.org/aspwood-v3.0/), respectively. The tissue atlas dataset includes tissues collected from buds, male catkins, female catkins, leaf, root and stem. The AspWood dataset includes samples collected from phloem, cambium, expanding xylem and maturing xylem. Gene expression was normalized by Z-score. Red and blue represent high and low expression, respectively.

A hierarchical transcriptional regulatory network for lignin biosynthetic genes has been established over the past 10 years (Zhao et al., 2010; Zhong and Ye, 2011; Lin et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2018a; Chen et al., 2019). This network involves members of several transcription factor (TF) families including MYBs and NACs. A recent study identified a novel TF (i.e., PtrEPSP-TF) encoding a homolog of 5-enolpyruvylshikimate 3-phosphate (EPSP) synthase in the shikimate pathway, which possesses a helix-turn-helix motif in the N terminus and can function as a transcriptional repressor to regulate gene expression in the phenylpropanoid pathway in Populus (Xie et al., 2018a). Correspondingly, the expression of lignin-related TFs is affected by several other genes. For example, overexpression of a serine hydroxymethyltransferase (PtSHMT2) decreases the lignin content in transgenic poplar (Zhang et al., 2019a). Overexpression of a prefoldin chaperonin β subunit gene PdPFD2.2 increases lignin S/G ration in poplar (Zhang et al., 2019b). This suggests that the molecular regulation of lignin biosynthesis is not unidirectional and is more complex than that was previously reported.

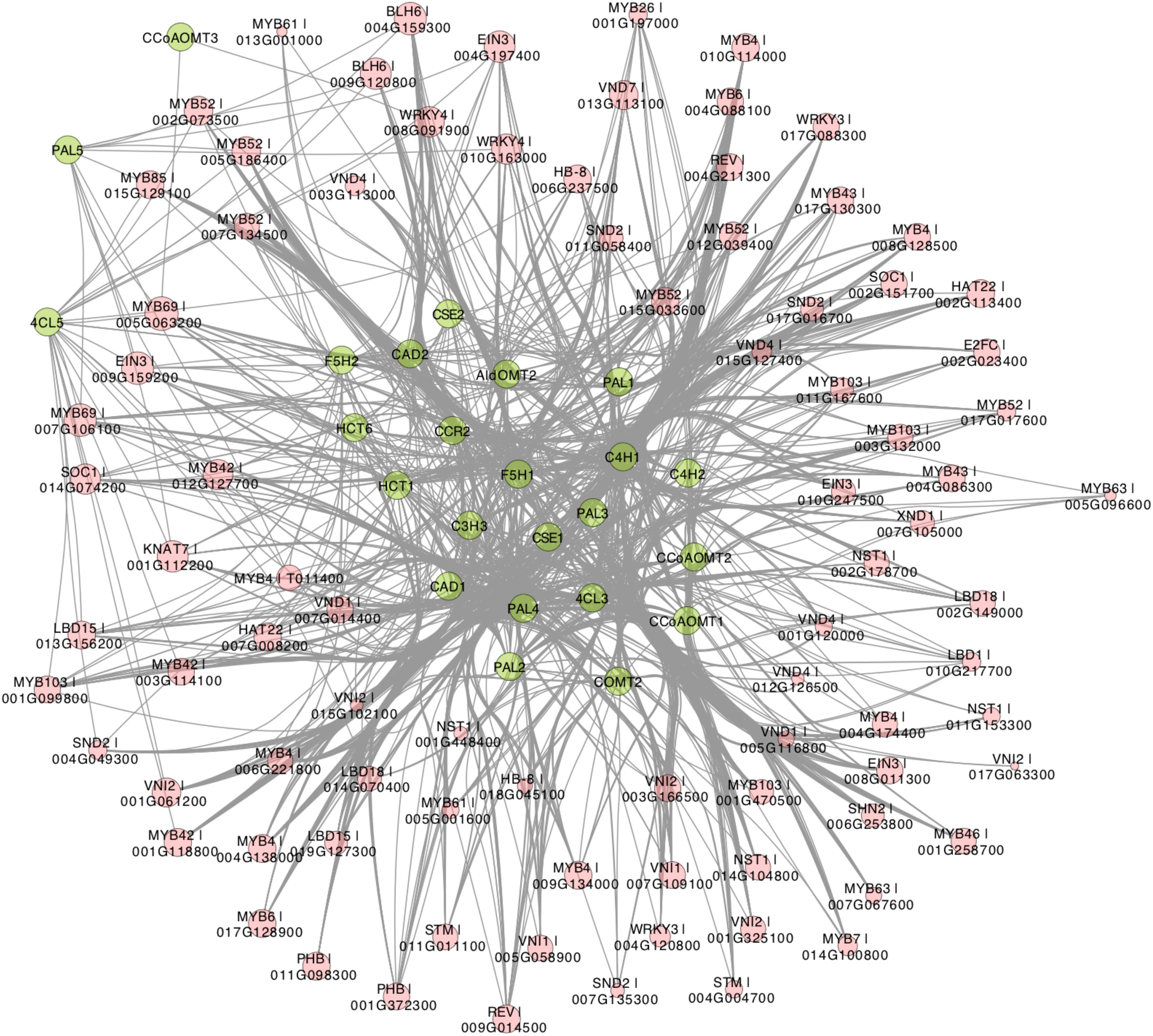

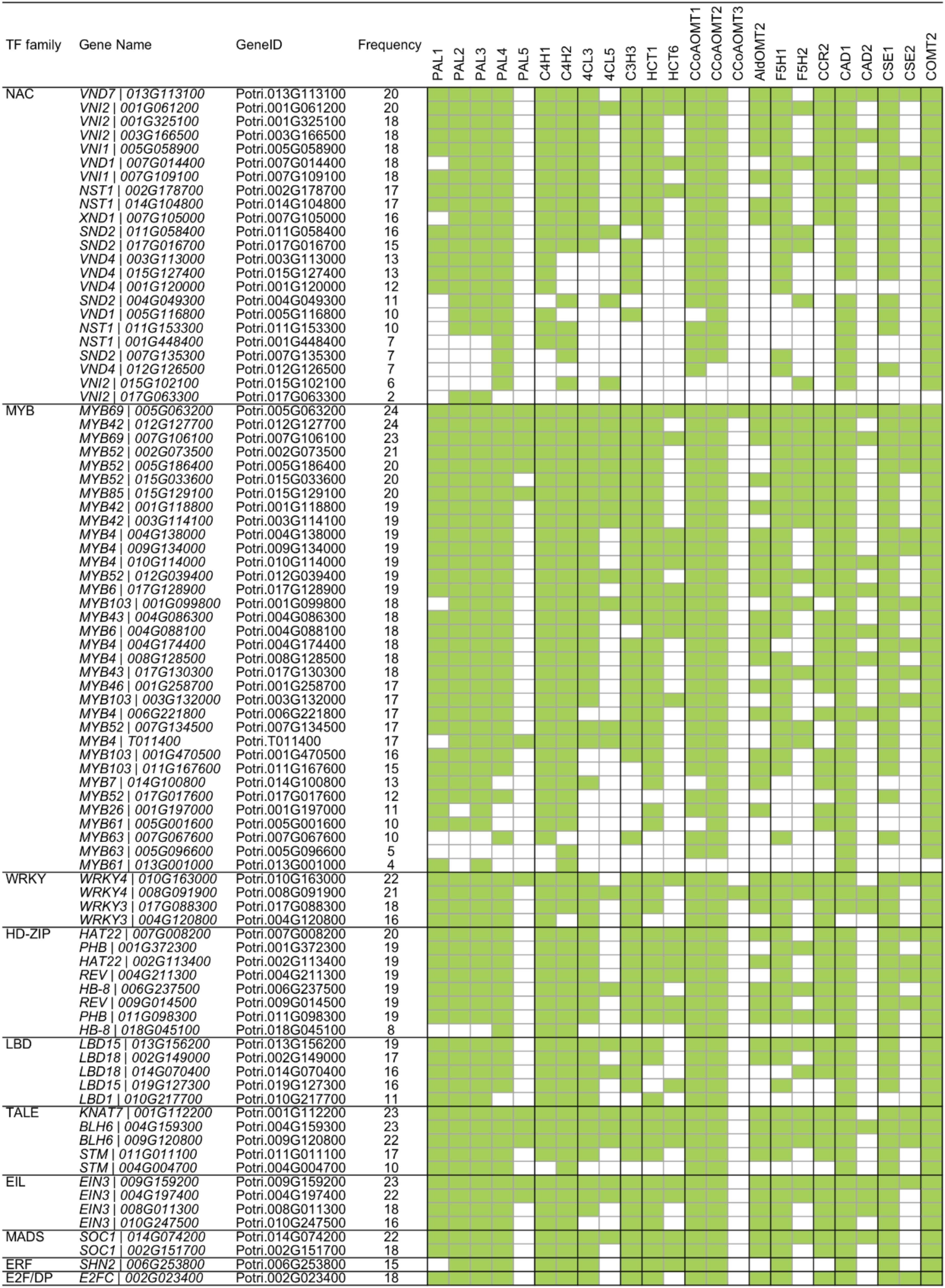

Recently, Gunasekara et al. (2018) developed a novel algorithm called triple-gene mutual interaction (TGMI) for identifying the pathway regulators using high-throughput gene expression data, which calculates the mutual interaction measure for each triple gene grouping (two pathway genes and one TF) and then examines its statistical significance using bootstrap. Implementing this algorithm, Gunasekara et al. (2018) analyzed pathway regulators of lignin biosynthesis using a compendium dataset that comprised 128 microarray samples from Arabidopsis stem tissues under short-day conditions. In this review, we also applied the TGMI algorithm to identify regulators of lignin biosynthesis in Populus based on the tissue-specific Populus Gene Expression Atlas and AspWood datasets (209 RNA-Seq samples in total). As anticipated, a series of known lignin biosynthesis-related TFs (87 TFs from 10 families), such as members in NAC and MYB families, were correlated with the lignin biosynthetic genes (Figures 3, 4). In addition, we identified several novel TFs that were highly correlated with the monolignol biosynthetic genes, expanding our view of the transcriptional regulatory network affecting lignin biosynthesis. Individual classes of these TFs are presented in Figures 3, 4.

Figure 3. Regulatory network generated by triple-gene mutual interaction (TGMI) algorithm for the Populus lignin biosynthesis pathway using the RNA-Seq data from Populus Gene Expression Atlas and AspWood datasets. Green nodes represent monolignol biosynthetic genes. Red nodes are transcription factors (TF) and node size represent frequency of TF. Edges represent regulatory relationships from TGMI algorithm.

Figure 4. Regulatory relationship of transcription factor (TF) and monolignol biosynthetic genes generated by triple-gene mutual interaction (TGMI) algorithm. Green blocks represent statistically significant interactions.

To further understand the transcriptional regulation between TFs and lignin biosynthetic genes, we generated a heatmap to reveal the correlation between lignin biosynthetic genes and known lignin-related TFs (Figure 4). PAL genes showed strong correlation with MYB TFs. During secondary cell wall formation, MYB46 and MYB83 and their orthologs in several plant species, including Arabidopsis, Populus, and Eucalyptus, have been identified as the direct targets of SNDs (SECONDARY WALL-ASSOCIATED NAC DOMAIN PROTEINS) and VNDs (VASCULAR-RELATED NAC DOMAINS) and function as the second-layer master switches (McCarthy et al., 2010; Zhong and Ye, 2011; Kim et al., 2013; Ko et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2018a). Overexpression of MYB46 and MYB83 caused ectopic deposition of secondary cell walls through activation of the lignin, cellulose and xylan biosynthetic genes (Zhong and Ye, 2011). Electrophoretic mobility shift assay and chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis showed that MYB46 directly binds to the promoters of PAL (Kim et al., 2014). Similarly, their orthologs in Populus, PtrMYB3 (Potri.001G267300) and PtrMYB20 (Potri.009G061500), activate the biosynthesis pathways of lignin, cellulose and xylan in both Arabidopsis and Populus, including PAL genes (McCarthy et al., 2010). In Populus tomentosa, PtoMYB216 (GenBank: JQ801749, ortholog of Potri.013G001000), a homolog of Arabidopsis AtMYB61 and AtMYB85, was specifically expressed during secondary wall formation in wood. The expression of PAL4 was induced in the transgenic plants overexpressing PtoMYB216 (Tian et al., 2013). PtoMYB156 (GenBank: KT990214, ortholog of Potri.009G134000) is a homolog of AtMYB4, which functions as phenylpropanoid/lignin biosynthesis repressor. Overexpression of PtoMYB156 in poplar also resulted in downregulation of PtoPAL1 (Yang et al., 2017). Four additional MYB TFs (MYB20, MYB42, MYB43 and MYB85) were recently reported as transcriptional regulators that directly activate lignin biosynthetic genes during secondary wall formation in Arabidopsis. Quadruple mutant myb20/42/43/85 plants exhibited reduced transcript levels of PAL (Geng et al., 2020). From these results, MYB TFs appear to be regulated by a series of master switches during secondary cell wall biosynthesis. The transcriptional regulation of PAL is likely regulated by a hierarchical or more complex pattern, in addition to the direct regulation by these MYB TFs.

As shown in Figure 4, C4H1 was correlated with the TGMI-based expression of 32 MYB TFs. Recently, a transcriptional regulatory network (TRN) of wood formation based on a P. trichocarpa wood-forming cell system with quantitative transcriptomics and chromatin binding assays was constructed (Chen et al., 2019). In the TRN, PtrC4H1 was regulated by PtrWBLH2 (a wood Bel-like homeodomain protein), which is a direct target of PtrMYB021 and PtrMYB074. Comparably, in P. tomentosa, C4H2 is directly activated by PtoMYB216 through AC elements (Tian et al., 2013). In addition, the expression of C4H was repressed by MYB transcriptional repressors. In Arabidopsis, AtMYB4 downregulates the expression of C4H (Jin et al., 2000). Ectopic expression of E. gunnii EgMYB1 in Populus repressed the expression of PtaC4H2 in wood tissue (Legay et al., 2010). Moreover, Arabidopsis WRKY12 is a transcriptional repressor that can directly bind to the promoter of NST2, a master regulator of lignin biosynthesis. Loss-of-function mutants of WRKY12 in Arabidopsis, and its ortholog in Medicago, result in ectopic deposition of lignin, xylan, and cellulose in pith cells (Wang et al., 2010). Its homolog in Populus, PtrWKRY19 (Potri.014G050000), is highly expressed in stems, especially in pith. Finally, PtrWRKY19 can repress the expression of PtoC4H2 through W-box elements (Yang et al., 2016).

4CL is the third step in the phenylpropanoid pathway and it is important for not only monolignol biosynthesis but also the generation of other secondary metabolites (Tsai et al., 2006). Based on the regulatory network, the two 4CL genes (4CL3 and 4CL5) were correlated with multiple NAC and MYB TFs (Figure 4). In Populus, the expression of 4CL5 was upregulated in transgenic plants overexpressing PtrMYB152 (GenBank: XM_002302907, ortholog of Potri.017G130300), a homolog of AtMYB58/63/85 (Li et al., 2014). Similarly, 4CL5 could be activated by another MYB member PtoMYB216 (Tian et al., 2013). The promoters of 4CL genes include AC elements that provide binding sites for secondary cell-wall-related MYB genes. In several plant species, NAC TFs have been reported to regulate the expression of 4CL genes. In support of these observations, EjNAC1 had trans-activation activities on promoter of Ej4CL1 (Xu et al., 2015) and the expression of 4CL was repressed in Medicago nst mutant (Zhao et al., 2010). However, whether 4CL genes are direct targets of NAC TFs in Populus remains unknown.

The regulatory network pattern in Figure 4 reveals that C3H has a similar pattern to the 4CL genes, indicating the transcriptional regulation of C3H might be similar with 4CL genes. As expected, the expression of C3H3 was also activated by PtoMYB216 and PtrMYB152 (Tian et al., 2013; Li et al., 2014). Still, studies of other species revealed that C3H could be regulated by other TF families. Switchgrass PvMYB4 is a transcriptional repressor and binds to the AC elements. The expression of C3H was activated by overexpressing PvMYB4 in transgenic tobacco and switchgrass (Shen et al., 2012). In Medicago nst mutant, the expression of C3H was repressed due to loss-of-function of NST (Zhao et al., 2010). In addition, the expression of C3H was induced by overexpressing GbERF1-like, a Gossypium barbadense ethylene response-related factor, in transgenic cotton and Arabidopsis (Guo et al., 2016). The AC elements provide the binding sites for the direct TF regulation.

HCT is involved in the production of methoxylated monolignols that are precursors to G- and S-unit lignin. HCT-downregulated plants are strikingly enriched in H lignin units, a minor component of lignin (Wagner et al., 2007). In P. trichocarpa, HCT1 and HCT6 display xylem-specific expression, which is regulated by PtrWBLH2 and PtrWBLH1, respectively (Chen et al., 2019). A recent study using genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL)/expression quantitative trait nucleotide (eQTN) studies identified a defense-related HCT2 that was regulated by WRKY TFs (Zhang et al., 2018b), implying that other TF families might be also involved in the transcriptional regulation of HCT gene family under alternate developmental circumstances. Heterologous expressing SbbHLH1, a Sorghum bicolor basic helix-loop-helix gene, reduced the lignin content through repress the expression of HCT in transgenic Arabidopsis (Yan et al., 2013).

As shown in Figure 4, three CCoAOMT genes were highly positively correlated with seven TFs in NAC family. It has been reported that NAC TFs function as master regulators in the lignin biosynthesis pathway. The SECONDARY WALL NACs (SWNs) consists of two types NACs: SECONDARY WALL-ASSOCIATED NAC DOMAIN PROTEIN (SND)/NAC SECONDARY WALL THICKENING PROMOTING FACTOR (NST) and VASCULAR-RELATED NAC DOMAINS (VNDs) (Zhang et al., 2018a). In Arabidopsis, ectopic overexpression of SND1 significantly induced the expression of CCoAOMT (Zhong et al., 2006). In Populus, six SND1 homologs, named PtrWND1-6 (WOOD ASSOCIATED NAC DOMAIN), are highly expressed in the developing xylem. Overexpression of PtrWND2B and PtrWND6B in Arabidopsis causes ectopic deposition of secondary cell wall through activation of the lignin, cellulose and xylan biosynthetic genes (Zhong et al., 2010b). In Populus, the transcript of CCoAOMT1 was induced by overexpressing WND3A (Yang et al., 2019). Zhou et al. (2014) demonstrated that the promoter of CCoAOMT1 is directly activated by Arabidopsis VND1-5. Similar results were also found in Arabidopsis transgenic lines expressing PtrWND6B. A transactivation assay indicates CCoAOMT is direct target of PtrWND6B (Zhong et al., 2010b). In addition, MYB TFs were also involved in transcriptional regulation of CCoAOMT. As direct target of PtrWND2, PtrMYB3 and PtrMYB20 (homologous of Arabidopsis MYB46/83) were able to activate the promoters of PtrCCoAOMT1 through Arabidopsis protoplast transactivation analysis (McCarthy et al., 2010).

F5H is a cytochrome P450 (CYP)-dependent monooxygenase, it is specifically required for S-unit lignin biosynthesis and diverts G-unit into the S-unit pathway (Humphreys et al., 1999). Using P. trichocarpa wood-forming cell system, three TFs (PtrMYB090, PtrMYB161 and PtrWBLH2) were identified as upstream regulator of F5H genes in Populus (Chen et al., 2019). In Medicago, the expression of F5H is directly regulated by the secondary cell wall master switch NST1/SND1 (Zhao et al., 2010). In addition, MYB103 is required for the expression of F5H and S-lignin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. The S-lignin content, as well as transcript level of F5H, are strongly decreased in the myb103 mutants, whereas the G-lignin content was concomitantly increased (Öhman et al., 2013).

CCR and CAD catalyze the final steps of monolignol biosynthesis (Figure 1). In many species, CCR and CAD exhibit similar expression patterns in vascular tissues. The expression of PtrCAD1 was repressed by PtrMYB174 in Populus (Chen et al., 2019). Other studies indicated that CCR2 and CAD were activated by PtoMYB216 and PtrMYB152 (Tian et al., 2013; Li et al., 2014). Using promoter deletion analysis, Rahantamalala et al. (2010) identified an 80-bp region and a 50-bp region in the promoters of E. gunnii EgCAD2 and EgCCR that contains MYB elements, respectively. In addition, heterologous expressing Vitis vinifera VvWRKY2 activate the expression of CCR and CAD in transgenic tobacco (Guillaumie et al., 2010).

CSE is a recently identified novel enzymatic step in the lignin biosynthetic pathway (Vanholme et al., 2013). Similar to other MYB46/83 regulated genes, CSE has M46RE motifs in the promoter region, and its expression is induced by MYB46 (Kim et al., 2014). In Populus, it is directly regulated by PtrWBLH1, a downstream regulator of PtrMYB021 (homolog of Arabidopsis MYB46) (Chen et al., 2019). In addition, the regulatory network indicated that CSE1 is negatively correlated with a WRKY TF in Populus (Figure 4), but whether WRKY directly regulates CSE needs to be confirmed.

COMT is critical for the S-unit lignin biosynthesis (Goujon et al., 2003b). In Arabidopsis, COMT is directly regulated by a lignin-specific MYB AtMYB58 through binding to the AC elements (Zhou et al., 2009). A similar regulatory pattern is also observed in Populus. That is, COMT2 is activated by PtoMYB170, PtrMYB090 and PtrMYB152, but not PtoMYB216 (Tian et al., 2013; Li et al., 2014; Xu et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2019). In addition, the promoter of Arabidopsis COMT could be bound by BP, a knotted1-like homeobox (KNOX) gene (Mele et al., 2003). The TGMI analysis indicated that COMT2 is highly associated with TFs in HD-ZIP and LBD families, in addition to NAC and MYB TFs (Figure 4). However, experimental evidence will be required to verify this regulatory relationship.

Post-transcriptional regulation of lignin biosynthesis pathway genes plays important roles in molecular regulation at the RNA level, including controlling alternative splicing, RNA capping, poly-A tail addition, and mRNA stability (Sullivan and Green, 1993). To date, studies of the post-transcriptional regulation of lignin pathway have been focused on transcriptional regulatory genes. In this section, we summarize recent progress on the post-transcriptional regulation of regulatory genes in lignin pathway.

Alternative splicing, as a post-transcriptional regulation mechanism, allows organisms to increase their proteomic diversity and regulate gene expression. It has been reported that alternative splicing of key regulators and enzymes play a critical role in the lignin biosynthesis pathway. A previous study analyzed the transcriptome of 20 P. trichocarpa individuals and found that ∼40% xylem genes are alternatively spliced, which include cell wall-related genes C2H2 TF and glycosyl transferases (Bao et al., 2013). Xu et al. (2014) compared the inter-species conservation of alternative splicing events in the developing xylem of Populus and Eucalyptus and found that ∼28% of alternative splicing genes were putative orthologs in these two species. Alternative splicing can also affect the expression of downstream genes. For example, retention of intron 2 of Populus PtrWND1B/PtrSND1, by alternative splicing, resulted in loss of DNA binding and transactivation activities (Li et al., 2012). This alternative splicing event appears to regulate secondary cell wall thickening and the expression of the lignin-related gene 4CL1. Similar alternative splicing was also observed in its orthologs in Eucalyptus, but not in Arabidopsis (Zhao et al., 2014). In addition, other members in the VND- and SND-type NAC family are regulated by alternative splicing. For example, retained introns of PtrSND1-A2 and PtrVND6-C1 play reciprocal cross-regulation of the two families during wood formation (Lin et al., 2017).

microRNAs (miRNAs) are a class of small non-coding RNAs with a 21-23 ribonucleotide RNA sequence that play central roles in gene expression regulation through directing mRNA cleavage or translational inhibition. Several miRNAs, such as miRNA397, miRNA408, miRNA857, and miRNA528, have been reported to target laccase (LAC) genes, encoding a class of blue copper oxidase proteins involved in lignin polymerization (Sunkar and Zhu, 2004; Lu et al., 2013). In Populus, the expression of 17 PtrLACs are down-regulated and lignin content is decreased by overexpression of Ptr-miRNA397a (Lu et al., 2013). Arabidopsis LAC4 controls both lignin biosynthesis and seed yield, and its expression is controlled by miRNA397 member At-miRNA397b. Overexpression of At-miRNA397b reduced lignin deposition through repression of the biosynthesis of both S- and G-lignin subunits (Wang et al., 2014). In addition, overexpression a wounding-responsive miRNA828 can enhance lignin deposition and H2O2 accumulation through repressed expression of IbMYB and IbTLD in sweet potato (Lin et al., 2012). Acacia mangium miRNA166 is differentially expressed between phloem and xylem, where it targets HD-ZIP III type TFs to regulate the expression of C4H, CAD, and CCoAOMT (Ong and Wickneswari, 2012). In maize, Zm-miRNA528, induced by excess nitrogen and repressed by nitrogen deficiency, targets LAC3 and LAC5 and regulates the biosynthesis of S-, G-, and H-subunits (Sun et al., 2018). Finally, in Arabidopsis, miRNA858a directly regulates the expression of several MYBs during flavonoid biosynthesis. Overexpression of miRNA858a results in ectopic deposition of lignin in transgenic plants (Sharma et al., 2016). Collectively, these results indicate that miRNAs play important regulatory roles during multiple levels of lignin biosynthesis.

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) refer to transcripts that lack coding potential and are greater than 200 nucleotides (Kapranov et al., 2007). Chen et al. (2015) performed a genome-wide identification of lncRNA in tension wood, opposite wood and normal wood xylem of P. tomentosa and identified 16 genes targeted by lncRNAs that are involved in wood formation processes, including lignin biosynthesis (Chen et al., 2015). In a similar study, the interaction of NEEDED FOR RDR2-INDEPENDENT DNA METHYLATION (NERD) and its regulatory lncRNA NERDL, which is partially located within the promoter region of NERD, is involved in the wood formation processes in Populus (Shi et al., 2017). In cotton, Dt subgenome-specific lncRNAs are enriched in lignin catabolic processes. Wang et al. (2015) suggests that these lncRNAs may regulate lignin biosynthesis by regulating the expression of LAC4 (Wang et al., 2015). Although these studies imply the potential roles of lncRNAs in lignin biosynthesis, the underlying regulatory mechanism remain unverified.

In this review, we provide a comprehensive summary of the current knowledge of the transcriptional regulation of lignin biosynthetic genes and post-transcriptional regulation of regulatory genes in lignin biosynthesis in Populus. Lignin content has been reported as important factor in biomass recalcitrance for bioethanol conversion and production. Although many genes that play a regulatory role in the lignin biosynthesis pathway were captured in TGMI analysis, some previously reported lignin pathway regulators were missing, possibly due to limited data in our analysis. To overcome this issue and to capture other regulatory genes, multiple datasets, pooled from various tissues types during specific rapid developmental processes, should be investigated. In addition, GWAS and eQTL/eQTN analyses may provide further supportive lucidity in discovering novel regulators and regulatory mechanisms in lignin biosynthesis. Revealing the transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulatory mechanisms in lignin biosynthesis will help clarify the parameters of the lignin biosynthesis, ultimately improving the application of lignocellulose in biofuels and bioenergy. Understanding the increasingly complex lignin regulatory network will provide an important theoretical basis for basic plant biology and utilization of plant biomass.

This manuscript has been authored by UT-Battelle, LLC under Contract No. DE-AC05-00OR22725 with the U.S. Department of Energy. The United States Government retains and the publisher, by accepting the article for publication, acknowledges that the United States Government retains a non-exclusive, paid-up, irrevocable, worldwide license to publish or reproduce the published form of this manuscript, or allow others to do so, for United States Government purposes. The Department of Energy will provide public access to these results of federally sponsored research in accordance with the DOE Public Access Plan (http://energy.gov/downloads/doe-public-access-plan).

JZ collected and synthesized the data from literature and wrote the manuscript. GT, TT, WM, and J-GC revised the manuscript.

This research was supported by the Center for Bioenergy Innovation (CBI). CBI is supported by the Office of Biological and Environmental Research (BER) in the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science. Oak Ridge National Laboratory is managed by UT-Battelle, LLC for the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract Number DE-AC05-00OR22725.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Baghdady, A., Blervacq, A. S., Jouanin, L., Grima-Pettenati, J., Sivadon, P., and Hawkins, S. (2006). Eucalyptus gunnii CCR and CAD2 promoters are active in lignifying cells during primary and secondary xylem formation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 44, 674–683. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2006.10.027

Bao, H., Li, E., Mansfield, S. D., Cronk, Q. C., El-Kassaby, Y. A., and Douglas, C. J. (2013). The developing xylem transcriptome and genome-wide analysis of alternative splicing in Populus trichocarpa (black cottonwood) populations. BMC Genomics 14:359. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-359

Barros, J., Escamilla-Trevino, L., Song, L., Rao, X., Serrani-Yarce, J. C., Palacios, M. D., et al. (2019). 4-Coumarate 3-hydroxylase in the lignin biosynthesis pathway is a cytosolic ascorbate peroxidase. Nat. Commun. 10, 1994.

Chen, F., and Dixon, R. A. (2007). Lignin modification improves fermentable sugar yields for biofuel production. Nat. Biotechnol. 25, 759–761. doi: 10.1038/nbt1316

Chen, H., Wang, J. P., Liu, H. Z., Li, H. Y., Lin, Y. C. J., Shi, R., et al. (2019). Hierarchical transcription factor and chromatin binding network for wood formation in black cottonwood (Populus trichocarpa). Plant Cell 31, 602–626. doi: 10.1105/tpc.18.00620

Chen, J., Quan, M., and Zhang, D. (2015). Genome-wide identification of novel long non-coding RNAs in Populus tomentosa tension wood, opposite wood and normal wood xylem by RNA-seq. Planta 241, 125–143. doi: 10.1007/s00425-014-2168-1

Fraser, C. M., and Chapple, C. (2011). The phenylpropanoid pathway in Arabidopsis. Arabidopsis Book 9:e0152. doi: 10.1199/tab.0152

Geng, P., Zhang, S., Liu, J., Zhao, C., Wu, J., Cao, Y., et al. (2020). MYB20, MYB42, MYB43 and MYB85 regulate phenylalanine and lignin biosynthesis during secondary cell wall formation. Plant Physiol. 182, 1272–1283. doi: 10.1104/pp.19.01070

Goujon, T., Sibout, R., Eudes, A., Mackay, J., and Jouanin, L. (2003a). Genes involved in the biosynthesis of lignin precursors in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 41, 677–687. doi: 10.1016/s0981-9428(03)00095-0

Goujon, T., Sibout, R., Pollet, B., Maba, B., Nussaume, L., Bechtold, N., et al. (2003b). A new Arabidopsis thaliana mutant deficient in the expression of O-methyltransferase impacts lignins and sinapoyl esters. Plant Mol. Biol. 51, 973–989.

Guillaumie, S., Mzid, R., Mechin, V., Leon, C., Hichri, I., Destrac-Irvine, A., et al. (2010). The grapevine transcription factor WRKY2 influences the lignin pathway and xylem development in tobacco. Plant Mol. Biol. 72, 215–234. doi: 10.1007/s11103-009-9563-1

Gunasekara, C., Zhang, K., Deng, W., Brown, L., and Wei, H. (2018). TGMI: an efficient algorithm for identifying pathway regulators through evaluation of triple-gene mutual interaction. Nucleic Acids Res. 46:e67. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky210

Guo, W., Jin, L., Miao, Y., He, X., Hu, Q., Guo, K., et al. (2016). An ethylene response-related factor, GbERF1-like, from Gossypium barbadense improves resistance to Verticillium dahliae via activating lignin synthesis. Plant Mol. Biol. 91, 305–318. doi: 10.1007/s11103-016-0467-6

Humphreys, J. M., Hemm, M. R., and Chapple, C. (1999). New routes for lignin biosynthesis defined by biochemical characterization of recombinant ferulate 5-hydroxylase, a multifunctional cytochrome P450-dependent monooxygenase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 10045–10050. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.18.10045

Jin, H. L., Cominelli, E., Bailey, P., Parr, A., Mehrtens, F., Jones, J., et al. (2000). Transcriptional repression by AtMYB4 controls production of UV-protecting sunscreens in Arabidopsis. EMBO J. 19, 6150–6161. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.22.6150

Kapranov, P., Cheng, J., Dike, S., Nix, D. A., Duttagupta, R., Willingham, A. T., et al. (2007). RNA maps reveal new RNA classes and a possible function for pervasive transcription. Science 316, 1484–1488. doi: 10.1126/science.1138341

Kim, M. H., Cho, J. S., Jeon, H. W., Sangsawang, K., Shim, D., Choi, Y. I., et al. (2019). Wood transcriptome profiling identifies critical pathway genes of secondary wall biosynthesis and novel regulators for vascular cambium development in populus. Genes (Basel) 10, E690.

Kim, W. C., Kim, J. Y., Ko, J. H., Kang, H., and Han, K. H. (2014). Identification of direct targets of transcription factor MYB46 provides insights into the transcriptional regulation of secondary wall biosynthesis. Plant Mol. Biol. 85, 589–599. doi: 10.1007/s11103-014-0205-x

Kim, W. C., Ko, J. H., Kim, J. Y., Kim, J., Bae, H. J., and Han, K. H. (2013). MYB46 directly regulates the gene expression of secondary wall-associated cellulose synthases in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 73, 26–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313x.2012.05124.x

Ko, J.-H., Jeon, H.-W., Kim, W.-C., Kim, J.-Y., and Han, K.-H. (2014). The MYB46/MYB83-mediated transcriptional regulatory programme is a gatekeeper of secondary wall biosynthesis. Ann. Bot. 114, 1099–1107. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcu126

Legay, S., Sivadon, P., Blervacq, A. S., Pavy, N., Baghdady, A., Tremblay, L., et al. (2010). EgMYB1, an R2R3 MYB transcription factor from eucalyptus negatively regulates secondary cell wall formation in Arabidopsis and poplar. New Phytol. 188, 774–786. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03432.x

Li, C. F., Wang, X. Q., Lu, W. X., Liu, R., Tian, Q. Y., Sun, Y. M., et al. (2014). A poplar R2R3-MYB transcription factor, PtrMYB152, is involved in regulation of lignin biosynthesis during secondary cell wall formation. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 119, 553–563. doi: 10.1007/s11240-014-0555-8

Li, Q. Z., Lin, Y. C., Sun, Y. H., Song, J., Chen, H., Zhang, X. H., et al. (2012). Splice variant of the SND1 transcription factor is a dominant negative of SND1 members and their regulation in Populus trichocarpa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 14699–14704. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1212977109

Lin, J. S., Lin, C. C., Lin, H. H., Chen, Y. C., and Jeng, S. T. (2012). MicroR828 regulates lignin and H2O2 accumulation in sweet potato on wounding. New Phytol. 196, 427–440. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04277.x

Lin, Y.-C. J., Chen, H., Li, Q., Li, W., Wang, J. P., Shi, R., et al. (2017). Reciprocal cross-regulation of VND and SND multigene TF families for wood formation in Populus trichocarpa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, E9722–E9729.

Lu, S., Li, Q., Wei, H., Chang, M.-J., Tunlaya-Anukit, S., Kim, H., et al. (2013). Ptr-miR397a is a negative regulator of laccase genes affecting lignin content in Populus trichocarpa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 10848–10853. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1308936110

Marita, J. M., Ralph, J., Lapierre, C., Jouanin, L., and Boerjan, W. (2001). NMR characterization of lignins from transgenic poplars with suppressed caffeic acid O-methyltransferase activity. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1, 2939–2945. doi: 10.1039/b107219f

McCarthy, R. L., Zhong, R., Fowler, S., Lyskowski, D., Piyasena, H., Carleton, K., et al. (2010). The poplar MYB transcription factors, PtrMYB3 and PtrMYB20, are involved in the regulation of secondary wall biosynthesis. Plant Cell Physiol. 51, 1084–1090. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcq064

Mele, G., Ori, N., Sato, Y., and Hake, S. (2003). The knotted1-like homeobox gene BREVIPEDICELLUS regulates cell differentiation by modulating metabolic pathways. Genes Dev. 17, 2088–2093. doi: 10.1101/gad.1120003

Öhman, D., Demedts, B., Kumar, M., Gerber, L., Gorzsás, A., Goeminne, G., et al. (2013). MYB103 is required for FERULATE-5-HYDROXYLASE expression and syringyl lignin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis stems. Plant J. 73, 63–76. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12018

Ong, S. S., and Wickneswari, R. (2012). Characterization of microRNAs expressed during secondary wall biosynthesis in Acacia mangium. PLoS ONE 7:e49662. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049662

Raes, J., Rohde, A., Christensen, J. H., Van De Peer, Y., and Boerjan, W. (2003). Genome-wide characterization of the lignification toolbox in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 133, 1051–1071. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.026484

Rahantamalala, A., Rech, P., Martinez, Y., Chaubet-Gigot, N., Grima-Pettenati, J., and Pacquit, V. (2010). Coordinated transcriptional regulation of two key genes in the lignin branch pathway-CAD and CCR-is mediated through MYB-binding sites. BMC Plant Biol. 10:130. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-10-130

Rohde, A., Morreel, K., Ralph, J., Goeminne, G., Hostyn, V., De Rycke, R., et al. (2004). Molecular phenotyping of the pal1 and pal2 mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana reveals far-reaching consequences on phenylpropanoid, amino acid, and carbohydrate metabolism. Plant Cell 16, 2749–2771. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.023705

Sharma, D., Tiwari, M., Pandey, A., Bhatia, C., Sharma, A., and Trivedi, P. K. (2016). MicroRNA858 is a potential regulator of phenylpropanoid pathway and plant development. Plant Physiol. 171, 944–959.

Shen, H., He, X., Poovaiah, C. R., Wuddineh, W. A., Ma, J., Mann, D. G., et al. (2012). Functional characterization of the switchgrass (Panicum virgatum) R2R3-MYB transcription factor PvMYB4 for improvement of lignocellulosic feedstocks. New Phytol. 193, 121–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03922.x

Shi, W., Quan, M., Du, Q., and Zhang, D. (2017). The interactions between the long non-coding RNA NERDL and its target gene affect wood formation in Populus tomentosa. Front. Plant Sci. 8:1035. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01035

Sullivan, M. L., and Green, P. J. (1993). Post-transcriptional regulation of nuclear-encoded genes in higher plants: the roles of mRNA stability and translation. Plant Mol. Biol. 23, 1091–1104. doi: 10.1007/bf00042344

Sun, Q., Liu, X., Yang, J., Liu, W., Du, Q., Wang, H., et al. (2018). MicroRNA528 affects lodging resistance of maize by regulating lignin biosynthesis under nitrogen-luxury conditions. Mol. Plant 11, 806–814. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2018.03.013

Sundell, D., Street, N. R., Kumar, M., Mellerowicz, E. J., Kucukoglu, M., Johnsson, C., et al. (2017). AspWood: high-spatial-resolution transcriptome profiles reveal uncharacterized modularity of wood formation in Populus tremula. Plant Cell 29, 1585–1604. doi: 10.1105/tpc.17.00153

Sunkar, R., and Zhu, J.-K. (2004). Novel and stress-regulated microRNAs and other small RNAs from Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 16, 2001–2019. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.022830

Tian, Q. Y., Wang, X. Q., Li, C. F., Lu, W. X., Yang, L., Jiang, Y. Z., et al. (2013). Functional characterization of the poplar R2R3-MYB transcription factor PtoMYB216 involved in the regulation of lignin biosynthesis during wood formation. PLoS ONE 8:e76369. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076369

Tsai, C. J., Harding, S. A., Tschaplinski, T. J., Lindroth, R. L., and Yuan, Y. N. (2006). Genome-wide analysis of the structural genes regulating defense phenylpropanoid metabolism in Populus. New Phytol. 172, 47–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01798.x

Vanholme, R., Cesarino, I., Rataj, K., Xiao, Y., Sundin, L., Goeminne, G., et al. (2013). Caffeoyl shikimate esterase (CSE) is an enzyme in the lignin biosynthetic pathway in Arabidopsis. Science 341, 1103–1106. doi: 10.1126/science.1241602

Vanholme, R., Morreel, K., Ralph, J., and Boerjan, W. (2008). Lignin engineering. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 11, 278–285.

Wagner, A., Ralph, J., Akiyama, T., Flint, H., Phillips, L., Torr, K., et al. (2007). Exploring lignification in conifers by silencing hydroxycinnamoyl-CoA: shikimate hydroxycinnamoyltransferase in Pinus radiata. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 11856–11861. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701428104

Wang, C. Y., Zhang, S. C., Yu, Y., Luo, Y. C., Liu, Q., Ju, C. L., et al. (2014). MiR397b regulates both lignin content and seed number in Arabidopsis via modulating a laccase involved in lignin biosynthesis. Plant Biotechnol. J. 12, 1132–1142. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12222

Wang, H. Z., Avci, U., Nakashima, J., Hahn, M. G., Chen, F., and Dixon, R. A. (2010). Mutation of WRKY transcription factors initiates pith secondary wall formation and increases stem biomass in dicotyledonous plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 22338–22343. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016436107

Wang, J. P., Matthews, M. L., Williams, C. M., Shi, R., Yang, C. M., Tunlaya-Anukit, S., et al. (2018). Improving wood properties for wood utilization through multi-omics integration in lignin biosynthesis. Nat. Commun. 9:1579.

Wang, M., Yuan, D., Tu, L., Gao, W., He, Y., Hu, H., et al. (2015). Long noncoding RNAs and their proposed functions in fibre development of cotton (Gossypium spp.). New Phytol. 207, 1181–1197. doi: 10.1111/nph.13429

Xie, M., Muchero, W., Bryan, A. C., Yee, K., Guo, H.-B., Zhang, J., et al. (2018a). A 5-enolpyruvylshikimate 3-phosphate synthase functions as a transcriptional repressor in Populus. Plant Cell 30, 1645–1660. doi: 10.1105/tpc.18.00168

Xie, M., Zhang, J., Tschaplinski, T. J., Tuskan, G. A., Chen, J.-G., and Muchero, W. (2018b). Regulation of lignin biosynthesis and its role in growth-defense tradeoffs. Front. Plant Sci. 9:1427. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01427

Xu, C. Z., Fu, X. K., Liu, R., Guo, L., Ran, L. Y., Li, C. F., et al. (2017). PtoMYB170 positively regulates lignin deposition during wood formation in poplar and confers drought tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis. Tree Physiol. 37, 1713–1726. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpx093

Xu, P., Kong, Y., Song, D., Huang, C., Li, X., and Li, L. (2014). Conservation and functional influence of alternative splicing in wood formation of Populus and Eucalyptus. BMC Genomics 15:780. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-780

Xu, Q., Wang, W. Q., Zeng, J. K., Zhang, J., Grierson, D., Li, X., et al. (2015). A NAC transcription factor, EjNAC1, affects lignification of loquat fruit by regulating lignin. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 102, 25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2015.02.002

Yan, L., Xu, C., Kang, Y., Gu, T., Wang, D., Zhao, S., et al. (2013). The heterologous expression in Arabidopsis thaliana of sorghum transcription factor SbbHLH1 downregulates lignin synthesis. J. Exp. Bot. 64, 3021–3032. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert150

Yang, L., Zhao, X., Ran, L. Y., Li, C. F., Fan, D., and Luo, K. M. (2017). PtoMYB156 is involved in negative regulation of phenylpropanoid metabolism and secondary cell wall biosynthesis during wood formation in poplar. Sci. Rep. 7:41209.

Yang, L., Zhao, X., Yang, F., Fan, D., Jiang, Y. Z., and Luo, K. M. (2016). PtrWRKY19, a novel WRKY transcription factor, contributes to the regulation of pith secondary wall formation in Populus trichocarpa. Sci. Rep. 6:18643.

Yang, Y., Yoo, C. G., Rottmann, W., Winkeler, K. A., Collins, C. M., Gunter, L. E., et al. (2019). PdWND3A, a wood-associated NAC domain-containing protein, affects lignin biosynthesis and composition in Populus. BMC Plant Biol. 19:486. doi: 10.1186/s12870-019-2111-5

Zhang, J., Li, M., Bryan, A. C., Yoo, C. G., Rottmann, W., Winkeler, K. A., et al. (2019a). Overexpression of a serine hydroxymethyltransferase increases biomass production and reduces recalcitrance in the bioenergy crop Populus. Sustain. Energy Fuels 3, 195–207. doi: 10.1039/c8se00471d

Zhang, J., Xie, M., Li, M., Ding, J., Pu, Y., Bryan, A. C., et al. (2019b). Overexpression of a Prefoldin β subunit gene reduces biomass recalcitrance in the bioenergy crop Populus. Plant Biotechnol. J. 18, 859–871. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13254

Zhang, J., Xie, M., Tuskan, G. A., Muchero, W., and Chen, J. G. (2018a). Recent advances in the transcriptional regulation of secondary cell wall biosynthesis in the woody plants. Front. Plant Sci. 9:1535. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01535

Zhang, J., Yang, Y., Zheng, K., Xie, M., Feng, K., Jawdy, S. S., et al. (2018b). Genome-wide association studies and expression-based quantitative trait loci analyses reveal roles of HCT2 in caffeoylquinic acid biosynthesis and its regulation by defense-responsive transcription factors in Populus. New Phytol. 220, 502–516. doi: 10.1111/nph.15297

Zhao, Q. A., Wang, H. Z., Yin, Y. B., Xu, Y., Chen, F., and Dixon, R. A. (2010). Syringyl lignin biosynthesis is directly regulated by a secondary cell wall master switch. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 14496–14501. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009170107

Zhao, Y., Sun, J., Xu, P., Zhang, R., and Li, L. (2014). Intron-mediated alternative splicing of wood-associated nac transcription factor1b regulates cell wall thickening during fiber development in Populus species. Plant Physiol. 164, 765–776. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.231134

Zhong, R., Lee, C., and Ye, Z. H. (2010a). Global analysis of direct targets of secondary wall NAC master switches in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant 3, 1087–1103. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssq062

Zhong, R. Q., Lee, C. H., and Ye, Z. H. (2010b). Functional characterization of poplar wood-associated NAC domain transcription factors. Plant Physiol. 152, 1044–1055. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.148270

Zhong, R., and Ye, Z.-H. (2011). MYB46 and MYB83 bind to the SMRE sites and directly activate a suite of transcription factors and secondary wall biosynthetic genes. Plant Cell Physiol. 53, 368–380. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcr185

Zhong, R. Q., Demura, T., and Ye, Z. H. (2006). SND1, a NAC domain transcription factor, is a key regulator of secondary wall synthesis in fibers of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 18, 3158–3170. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.047399

Zhou, J. L., Lee, C. H., Zhong, R. Q., and Ye, Z. H. (2009). MYB58 and MYB63 are transcriptional activators of the lignin biosynthetic pathway during secondary cell wall formation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 21, 248–266. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.063321

Keywords: lignin biosynthesis, plant cell wall, transcriptional regulation, post-transcriptional regulation, transcription factor

Citation: Zhang J, Tuskan GA, Tschaplinski TJ, Muchero W and Chen J-G (2020) Transcriptional and Post-transcriptional Regulation of Lignin Biosynthesis Pathway Genes in Populus. Front. Plant Sci. 11:652. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.00652

Received: 12 February 2020; Accepted: 28 April 2020;

Published: 25 May 2020.

Edited by:

Chandrashekhar Pralhad Joshi, Michigan Technological University, United StatesReviewed by:

Jae-Heung Ko, Kyung Hee University, South KoreaThis work is authored by Jin Zhang, Gerald A. Tuskan, Timothy J. Tschaplinski, Wellington Muchero and Jin-Gui Chen on behalf of the U.S. Government and, as regards Dr. Zhang, Dr. Tuskan, Dr. Tschaplinski, Dr. Muchero and Dr. Chen, and the U.S. Government, is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. Foreign and other copyrights may apply. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jin Zhang, emhhbmdqMUBvcm5sLmdvdg==; Jin-Gui Chen, Y2hlbmpAb3JubC5nb3Y=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.