94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Plant Sci., 17 March 2020

Sec. Plant Abiotic Stress

Volume 11 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2020.00272

Qun Cheng1†

Qun Cheng1† Zhuoran Gan1†

Zhuoran Gan1† Yanping Wang2†

Yanping Wang2† Sijia Lu1

Sijia Lu1 Zhihong Hou1

Zhihong Hou1 Haiyang Li1

Haiyang Li1 Hongtao Xiang3

Hongtao Xiang3 Baohui Liu1,4*

Baohui Liu1,4* Fanjiang Kong1,4*

Fanjiang Kong1,4* Lidong Dong1*

Lidong Dong1*Soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merr.] is an important crop for oil and protein resources worldwide, and its farming is impacted by increasing soil salinity levels. In Arabidopsis the gene EARLY FLOWERING 3 (ELF3), increased salt tolerance by suppressing salt stress response pathways. J is the ortholog of AtELF3 in soybean, and loss-of-function J-alleles greatly prolong soybean maturity and enhance grain yield. The exact role of J in abiotic stress response in soybean, however, remains unclear. In this study, we showed that J expression was induced by NaCl treatment and that the J protein was located in the nucleus. Compared to NIL-J, tolerance to NaCl was significantly lower in the NIL-j mutant. We also demonstrated that overexpression of J increased NaCl tolerance in transgenic soybean hairy roots. J positively regulated expression of downstream salt stress response genes, including GmWRKY12, GmWRKY27, GmWRKY54, GmNAC, and GmSIN1. Our study disclosed a mechanism in soybean for regulation of the salt stress response. Manipulation of these genes should facilitate improvements in salt tolerance in soybean.

Soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merr.] is classified as a moderately salt-sensitive crop, and salt stress has negatively affected soybean yields (Parker et al., 1983; Ashraf, 1994; Munns and Tester, 2008). With increasing salinity levels, soybean production can be reduced by as much as 40% (Papiernik et al., 2005). Therefore, improving salt tolerance in soybean is essential to ensure future soybean yields. Some natural variations at the seedling stage in soybean have been identified through quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping and genome-wide association studies (Lee et al., 2004; Chen et al., 2008; Hamwieh and Xu, 2008; Hamwieh et al., 2011; Ha et al., 2013; Guan et al., 2014; Patil et al., 2016; Zeng et al., 2017; Do et al., 2018). For instance, a major salt-tolerant QTL located on Chr.3 (linkage group N) has been identified repeatedly using different soybean-mapping populations (Lee et al., 2004; Hamwieh and Xu, 2008; Hamwieh et al., 2011; Ha et al., 2013). This QTL has been cloned with a whole-genome resequencing and map-based cloning approach and found to encode an ion transporter (Guan et al., 2014; Qi et al., 2014; Do et al., 2016). The function of this gene in NaCl tolerance was confirmed by using the transgenic hairy root and B2Y cell overexpression assay (Qi et al., 2014). Moreover, by using reverse genetics, several transcription factor (TF) genes and ion-exchanger genes have been identified to contribute to NaCl stress tolerance in soybean (Chen et al., 2014; Li et al., 2017; Xu et al., 2018). For instance, GmWRKY27 encoded a WRKY TF and improved NaCl tolerance in transgenic soybean hairy roots (Wang et al., 2015). An NAC TF encoded by SALT INDUCED NAC 1 (GmSIN1) and overexpression of GmSIN1 promoted root growth and NaCl tolerance and increased yield under NaCl stress in soybean (Li et al., 2019). Ectopic expression of the GmERF3 gene in transgenic tobacco plants gave tolerance to high salinity (Zhang et al., 2009). In addition, GmCLC1 encoded Cl–/H+ antiporter and overexpression of GmCLC1 enhanced NaCl tolerance in transgenic plants (Wei et al., 2016). However, few of circadian genes have been demonstrated to respond and adapt to high salinity.

EARLY FLOWERING3 (ELF3) functions as one of the core circadian-clock components and was first determined to be a flowering repressor. For example, elf3 mutants flower early in a photoperiod insensitive manner (Zagotta et al., 1996) and ELF3-overexpressing (ELF3-OX) plants bloom very late only under long-day conditions in Arabidopsis (Liu et al., 2001). In addition, ELF3 interacts with other circadian clock components, ELF4 and LUX, called the evening complex (Nusinow et al., 2011). This complex (ELF3-ELF4-LUX) binds to the promoters of PIF4 and PIF5 to repress hypocotyl growth in the evening (Nusinow et al., 2011). A recent report showed that AtELF3-OX plants are tolerant to high NaCl and that elf3 mutants are hypersensitive to high NaCl in Arabidopsis (Sakuraba et al., 2017). Whether or not AtELF3 homologous are involved in NaCl stress responses in soybean plant, however, remains largely unknown.

Our previous research showed that J is a co-ortholog of the Arabidopsis flowering-time gene AtELF3 (Lu et al., 2017). However, whether this gene can respond to NaCl stress and the molecular mechanism, is largely unclear. In the present study, we demonstrated that expression of J was induced by NaCl and J protein was located in the nucleus. Transgenic soybean hairy roots overexpressing the J gene enhanced NaCl tolerance. J positively regulated the transcription levels of NaCl tolerance related genes GmWRKY12, GmWRKY27, GmWRKY54, GmNAC11, and GmSIN1 in soybean, leading to NaCl stress tolerance. These studies allow for the elucidation of J roles in NaCl stress responses.

Seedlings of soybean (NIL-J and NIL-j from Lu et al., 2017) were cultivated in a 8 × 8 cm flowerpot (vermiculite: nutritious soil is 1:3) and grown in a greenhouse under a photoperiod of 16 h light/8 h dark at 25°C and 60% humidity. For NaCl treatment, 12-day-old seedlings were watered with 200 mM sodium chloride (NaCl). For phenotype observations, we treated 12-day-old seedlings for 3 days.

Twelve-day-old NIL-J and NIL-j soybean seedings were watered with 200 mM NaCl treatment 2 days, leaves of NIL-J and NIL-j were harvested and immediately used. Both proline (Pro) and malondialdehyde (MDA) content were measured with the Pro assay kit (Yuanye, Shanghai, China, R30341) and MDA assay kit (Yuanye, R21870) based on the manufacturer’s protocols. All measurements were taken from three biological replicates.

For tissue-specific expression analyses, root, hypocotyl, cotyledon, leaf, stem, shoot apex, were collected from seedlings at first trifoliate (V1) stage, and flowers were collected from seedlings at first flowering (R1) stage. For total RNA extraction, leaf samples was harvested after 0, 1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 h of NaCl treatment, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, United States, catalog number 15596018) and reverse-transcribed the total RNA according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen). cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using a Super Script first-strand cDNA synthesis system (Takara, Dalian, China). Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis was performed to measure J transcription levels on a Roche LightCycler480 system (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) using a real-time PCR (RT-PCR) kit (Roche). Briefly, the cDNA was diluted to 10-fold and used 1 μL of diluted cDNA as the template in a 20 μL qPCR reaction, which was predenatured at 95°C for 5 min, followed by a 40-cycle program (95°C, 10 s; 60°C, 10 s; 72°C, 20 s per cycle). The soybean housekeeping genes GmTUB (Glyma.05G157300) (Cheng et al., 2019) and GmEF1β (Glyma.17G001400) (Jian et al., 2008) were used as an internal reference for normalization. The relative transcription level of the target gene was calculated using the 2–Δ Δ CT method. We used three biological replicates and three technical repeats in all assays.

The coding sequence of J was amplified by RT-PCR using primers J-GFPF and J-GFPR Supplementary Table S1, fused to the N-terminus of green fluorescent protein (GFP) under the control of the constitutive Cauliflower Mosaic Virus 35S (CaMV35S) promoter. The resulting expression vector, p35S:J-GFP, was inserted into A. tumefaciens strain GV3101 cells, and transfected into healthy leaves of 21-d-old Nicotiana benthamiana (N. benthamiana) tobacco leaves by agroinfiltration as described previously (Cheng et al., 2018). The fluorescence signals were imaged using an LSM800 spectral confocal microscope imaging system (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). The p35S-GFP vector was used as a control.

The full-length coding sequence of J from Harosoy was cloned into the pTF101-Gene vector (containing the bar gene for glufosinate resistance), between AvrII and MluI sites downstream of the constitutive CaMV35S promoter. As a negative control, the gene for the GFP was cloned and instead of J using the same vector and promoter. Both constructs (p35S-J and p35S-GFP) were introduced into Agrobacterium rhizogenes strain K599. Soybean hairy root transformation was performed as previously described by Cheng et al. (2018) with some modifications. Surface-sterilized soybean seeds were germinated on a germination medium [3.21 g/L Gamborg Basal salt mixture (Gamborg et al., 1968), 1.0 mg/L 6-BA, 2% sucrose, 0.8% agar, pH 5.8] for 5 days (16 h light/8 h dark). Agrobacterium rhizogenes strain K599 containing the recombinant construct was grown in yeast extract peptone medium containing 50 mg/L kanamycin and 25 mg/L rifampicin at 28°C for 16 h. We then used the construct to infect the cotyledons through scalpel incisions. The cotyledons were co-cultivated with A. rhizogenes on root-inducing medium [4.3 g/L Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium (Murashige and Skoog, 1962), 3% sucrose, 0.6 g/L MES, 250 mg/L cefotaxime and 250 mg/L carbenicillin]. After 2 weeks, cotyledons with roots emerging from the incision sites were transferred to new root-inducing medium with NaCl or medium without NaCl as untreated control. Root mass was weighed about 1 week after treatment and used the soybean plant NIL-j for transformation. The overexpression of the J gene was tested in transgenic hairy roots using qRT-PCR.

NIL-J and NIL-j soybean plants grown for 4 weeks under non-stress conditions were used for transcriptomic analysis. Total RNA was extracted from the samples with three biological replications using the Spectrum Plant Total RNA Kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States, STRN10-1KT). The sequencing libraries were generated using NEB Next Ultra RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, United States) following the manufacturer’s recommendations and added index codes to attribute sequences to each sample. The clustering of the index-coded samples was performed on a cBot Cluster Generation System using TruSeq PE Cluster Kit v4-cBot-HS (Illumia) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After cluster analysis, we sequenced the RNA on an Illumina Hiseq 2500 platform to generate paired-end reads. We mapped the total reads to the soybean genome1 using the Tophat tools software (Trapnell et al., 2009). Read counts for each gene were generated using HTSeq with a union mode. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) among samples were defined by DESeq using two separate models (Anders and Huber, 2010), based on fold change greater than two and a false discovery rate (FDR)–adjusted P value < 0.05. We implemented gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of the DEGs using the GOseq R packages based on Wallenius non-central hypergeometric distribution (Young et al., 2010), which can adjust for gene length bias in DEGs.

For phenotypic evaluation, we analyzed at least 10 NIL-J and NIL-j soybean plants, or GFP-OE and J-OE transgenic hairy roots. The exact numbers of individuals (n) are presented in the figure legends. For expression analyses using qRT-PCR, we pooled at least three individuals per tissue sample and performed at least three qRT–PCR reactions (technical replicates). The exact number of replicates is given in the figure legends. We compared mean values for each measured parameter using one-way analysis of variance from SPSS (version 20, IBM, Chicago, IL, United States) or one-tailed, two-sample Student’s t tests from Microsoft Excel, whenever appropriate. The statistical tests used for each experiment were given in the figure legends.

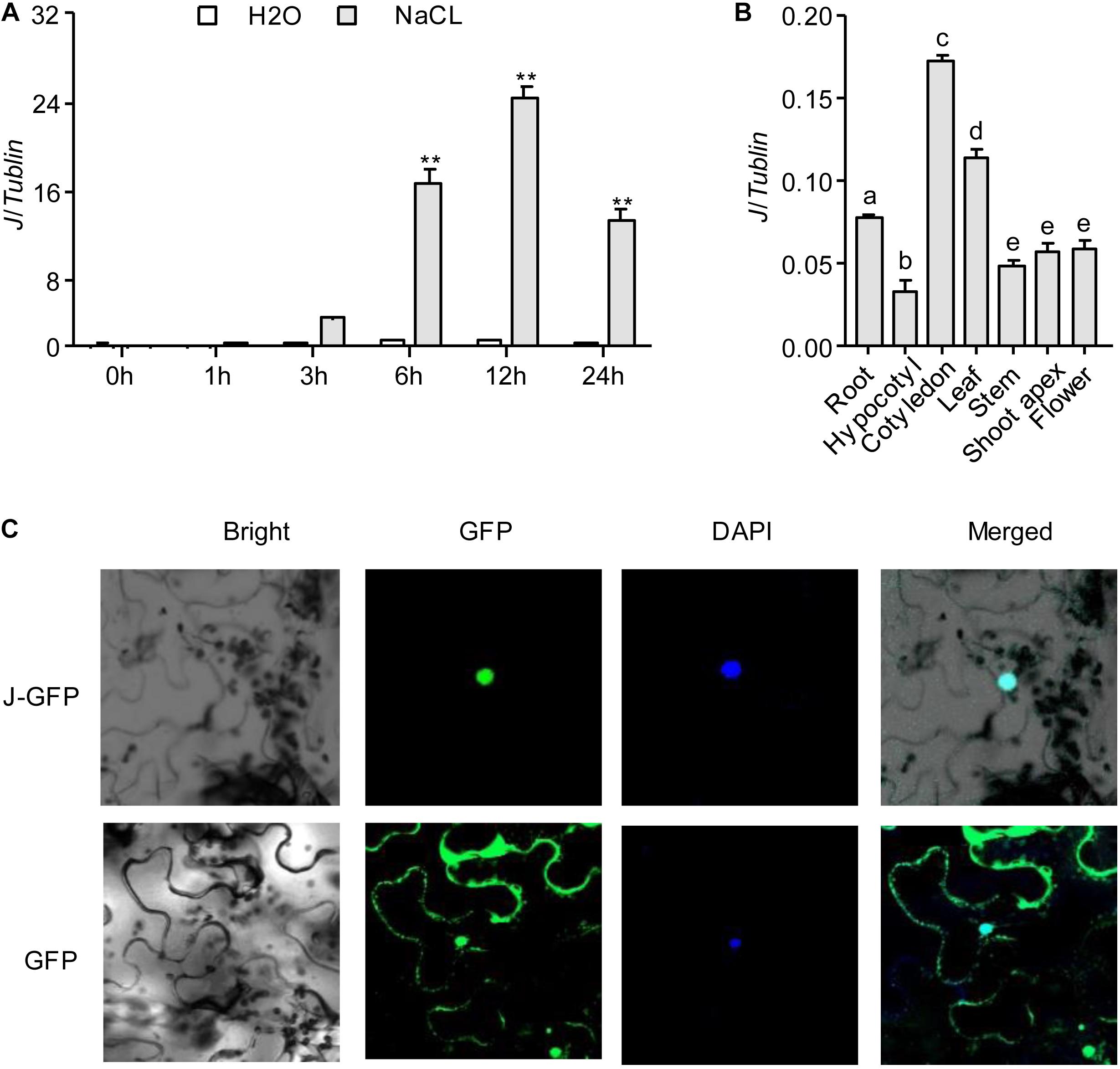

Our previous research showed that J is a co-ortholog of the Arabidopsis flowering-time gene AtELF3. J promotes flowering of soybean by directly repressing the expression of E1 (Lu et al., 2017). To understand whether J was involved in the response to NaCl stress in soybean, we first investigated the expression of J in soybean seedlings exposed for 2 weeks to NaCl (200 mM). The results showed that J expression was significantly induced and reached a peak at 12 h under NaCl exposure (Figure 1A). We next investigated the expression pattern of J by quantifying the relative abundance of the mRNA in different organs. J was constitutively expressed in soybean organs (root, hypocotyl, cotyledon, leaf, stem, shoot apex, flower) and highly expressed in the cotyledons, but it was expressed moderately in leaves and roots (Figure 1B). We further determined the subcellular localization of J. The p35S-J-GFP construct was transiently transformed into N. benthamiana leaf cells. The results show that J is located in the nucleus, and the GFP control is located primarily in the cytoplasm (Figure 1C and Supplementary Figure S1). These results indicate that J is a nuclear protein, and that the expression of J is induced by NaCl treatment.

Figure 1. J gene expression and protein localization. (A) J expression levels in response to NaCl treatment in soybean seedlings as revealed by qRT-PCR analysis. Significant differences were analyzed based on the results of three biological replications (Student’s t test: **P < 0.01). Bars indicate standard error of the mean. The presence of the same lowercase letter above the histogram bars in a–e denotes non-significant differences across the two panels (P > 0.05). (B) J expression in various organs of soybean plants. (C) Subcellular localization of J protein in in tobacco leaf cells. DAPI, fluorescence of 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; Merge, merge of GFP and DAPI.

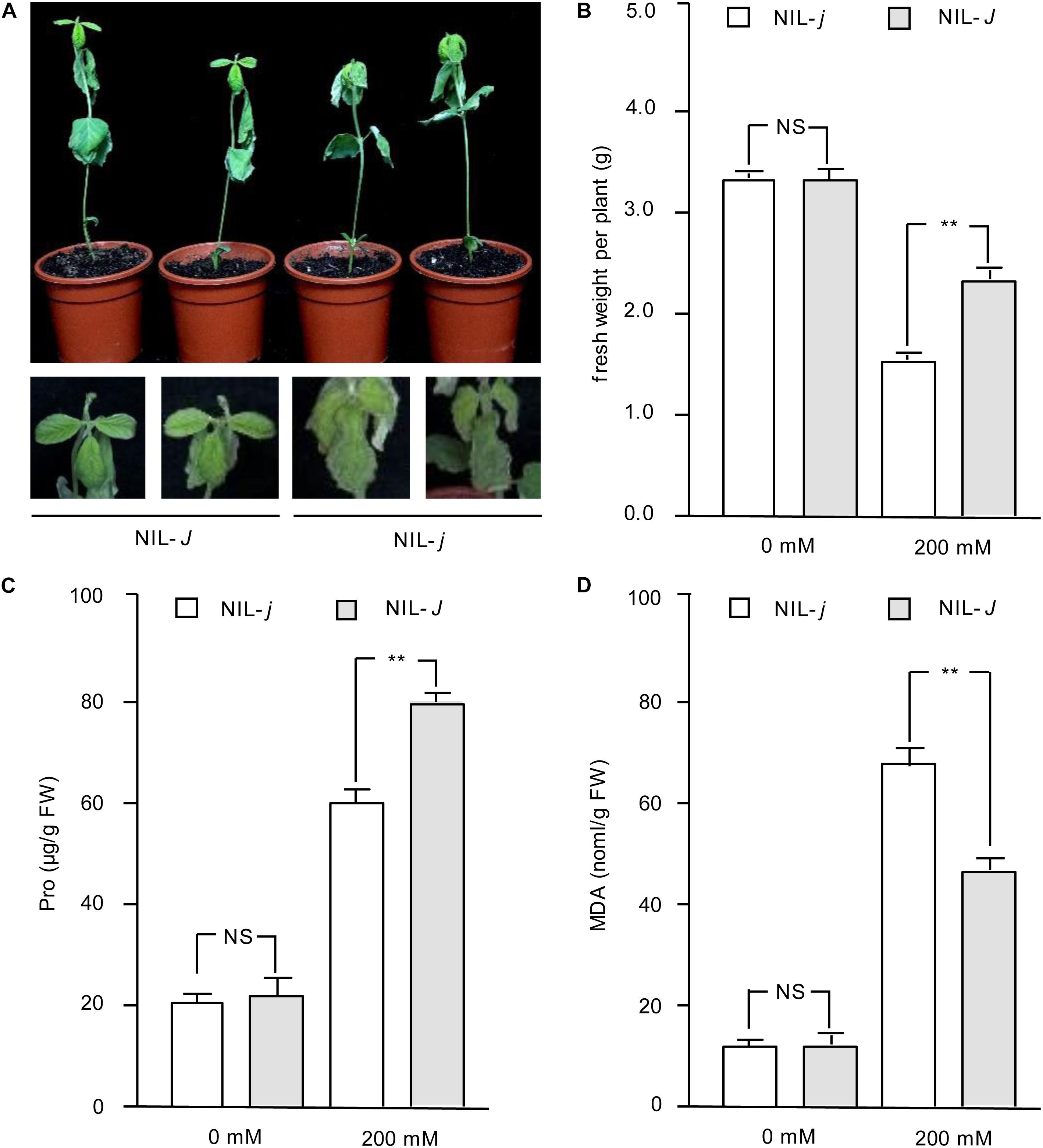

Because the expression of J was induced under NaCl treatment, we hypothesized the J gene may have a role in salt tolerance in soybean. To confirm this potential function, we examined seedlings from near-isogenic lines (NILs) carrying the functional J allele (NIL-J) or the non-functional j allele (NIL-j) (Lu et al., 2017) for their sensitivity to 200 mM NaCl. NIL-j seedlings were severely wilted and almost 99% of the leaves exhibited serious dehydration and drying (Figure 2A). Although old leaves of NIL-J soybean seedlings wilted, new leaves still grew vigorously (Figure 2A). The fresh weight was measured under NaCl treatment, and the results showed that the fresh weight of NIL-J soybean seedlings was significantly higher than that of NIL-j plants (Figure 2B). Next, we measured MDA and Pro content to compare stress impact between NIL-J and NIL-j. The results showed that NIL-J soybean seedlings increased Pro content to a larger extend than the NIL-j lines (Figure 2C), whereas the MDA content was less increased in the NIL-J lines under NaCl stress (Figure 2D). These measurements suggest the impact of the NaCl treatment is lower in the NIL-J lines.

Figure 2. Phenotype identification of J under NaCl treatment in NIL-J and NIL-j soybean plants. (A) Phenotypes of 14 days NIL-J and NIL-j seedings after planting, treated with 200 mM NaCl for 3 days, Bottom photos: second leaves. N = 12. (B) Fresh weight of NIL-J and NIL-j soybean plants with 0 mM or 200 mM NaCl treatment. (C) Proline contents in NIL-J and NIL-j soybean seedlings under 0 mM or 200 mM NaCl treatment. (D) MDA contents in NIL-J and NIL-j soybean seedlings under 0 mM or 200 mM NaCl treatment. Error bars, s.e.m. Data were analyzed using Student’s t test. NS, not significant. **P < 0.01.

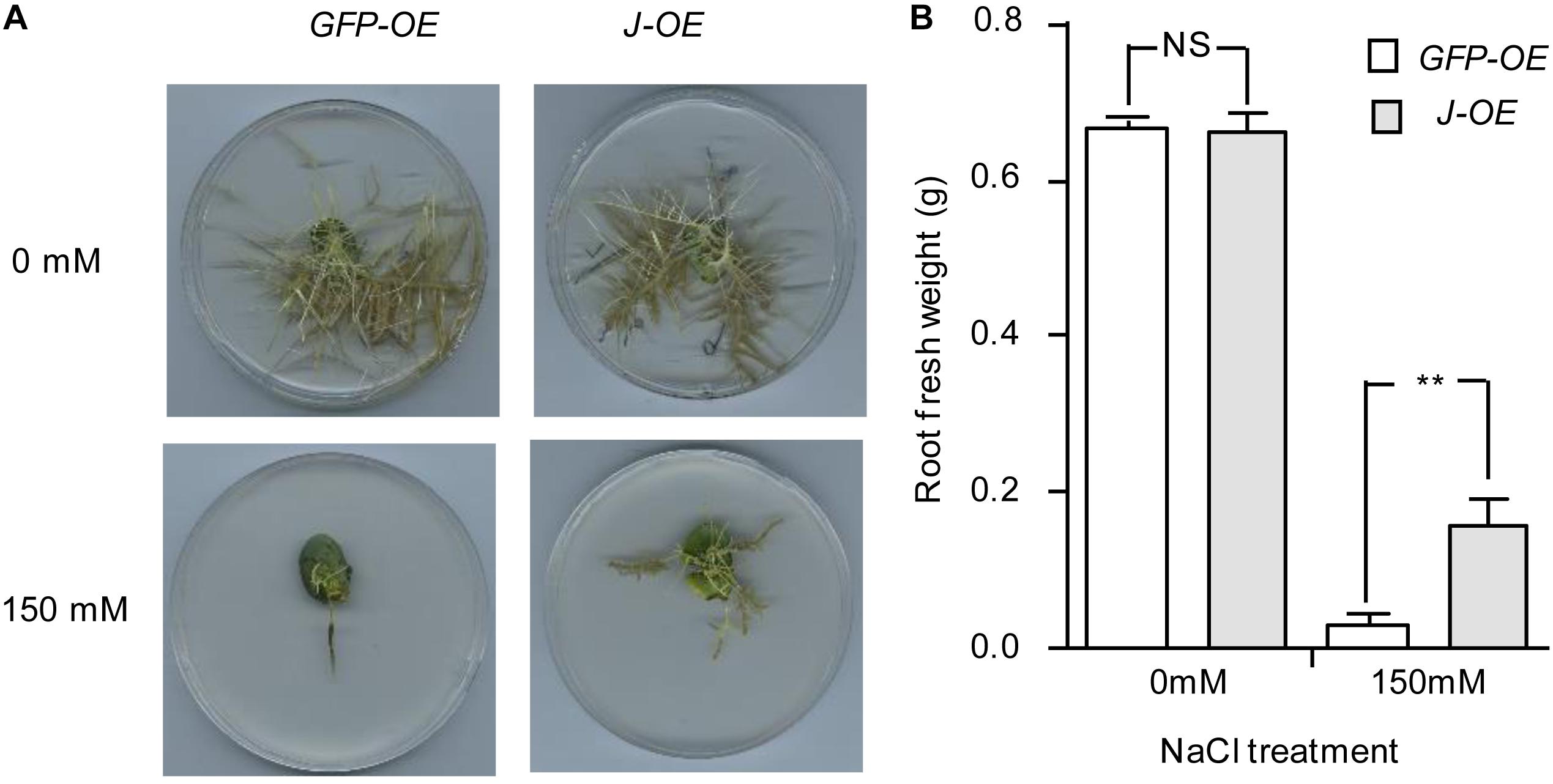

To further evaluate whether J is a NaCl-tolerant gene, a construct for J overexpression (pTF101-J) was generated and transformed into the soybean hairy roots of NIL-j. We confirmed the expression of the transgene by qRT-PCR (Supplementary Figure S1). In the absence of NaCl treatment, both root cultures transformed with either J or green fluorescent protein (GFP; control) gave healthy hairy roots (Figure 3A). When subjected to NaCl treatment, however, roots transformed with J showed significantly higher root fresh weights than the control (Figure 3B). This result support the idea that J could reduce NaCl stress.

Figure 3. Phenotype identification of J under salt treatment in transgenic hairy roots. (A) Phenotypes of transgenic hairy roots expressing either GFP or J with or without NaCl treatment. Photos were taken 2 weeks after treatment. (B) Fresh weight of hairy roots with or without NaCl treatment. N = 12. Error bars, s.e.m. Data were analyzed using Student’s t test. NS, not significant. **P < 0.01.

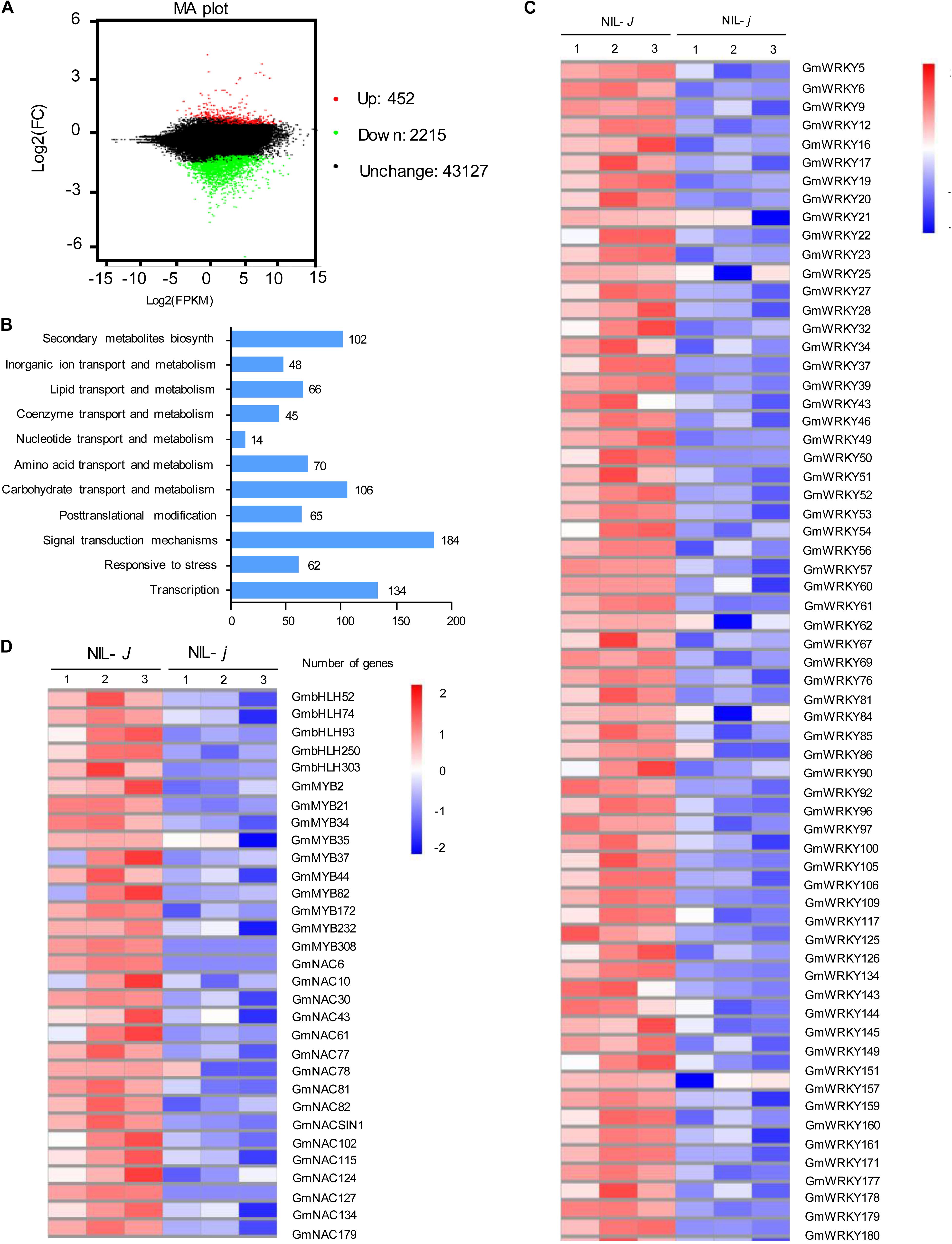

To identify genes possibly related to the J-mediated reduction of NaCl impact, we performed mRNA-sequence (RNA-Seq) analysis of the full transcripts from NIL-J and NIL-j soybean plants. We identified 2567 DEG that were affected more than two-fold in NIL-j compared with NIL-J under non-stress conditions (FDR P < 0.05; Figure 4A and Supplementary Data S1). Among the 2567 DEG, 452 genes were significantly upregulated and 2115 genes were significantly downregulated (Figure 4A and Supplementary Data S1). The GO terms specifically enriched in the downregulated DEGs were primarily genes involved in stress responses, in transcription, in secondary metabolite biosynthesis, in transport of organic ions, and signal transduction (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. Transcriptomic analysis of NIL-J and NIL-j soybean plant. (A) Numbers of genes showing differential expression between NIL-J and NIL-j soybean plant in non-NaCl-stressed seedings. (B) GO terms that were statistically enriched in differentially expressed genes in NIL-J and NIL-j RNA-seq assay. The numbers near the columns indicate the number of differentially expressed genes. (C,D) The heat map of differential expression of WRKY, bHLH, MYB, and NAC family genes in NIL-J and NIL-j. The numerical values for the blue-to-red gradient bar represent log2-fold change relative to the control sample.

Biotechnological and RNA-Seq approaches have identified some TF families, such as WRKY, NAC, MYB, and bHLH proteins, that respond to NaCl stress in soybean. Here, we found that 64 WRKY-family genes, 16 NAC-family genes, 10 MYB-family genes, and 5 bHLH-family genes were significantly downregulated in NIL-j plants in comparison to NIL-J (fold-change > 2, and P > 0.5) under normal conditions (Figures 4C,D). To further explore the effect of J on the transcription of NaCl related genes, we determined, for all of these genes, whether they respond to NaCl stress. As a result, we identified that 24 of 64 WRKY-family genes and 2 of 16 NAC-family genes that could respond to NaCl stress in soybean (Table 1). Therefore, we speculated that J may positively regulate the expression of these genes and contribute to improvements in NaCl tolerance in soybean.

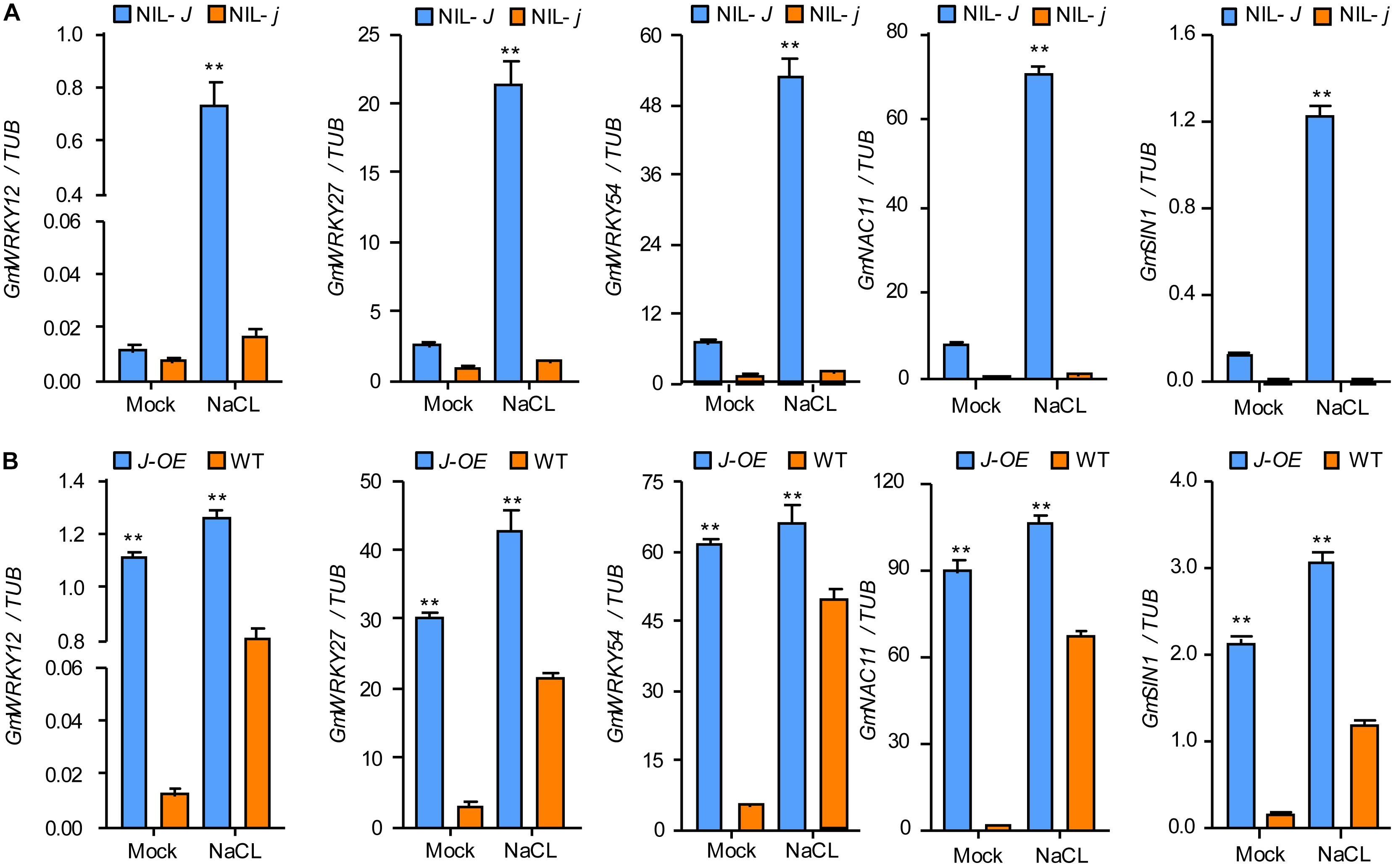

The comparison of the transcriptomes of 12 d old NIL-J and NIL-j soybean seedlings, showed higher expression of GmWRKY12, GmWRKY27, GmWRKY54, GmNAC11, and GmSIN1 in NIL-J lines. To confirm these differential expressions, and simultaneously test expression changes under NaCl treatment, we used qRT-PCR in NIL-J and NIL-j soybean plants and in J-overexpressing (J-OE) soybean hairy roots. These genes were all upregulated in NIL-J soybean plants (Figure 5A and Supplementary Figure S2) and J-OE soybean hairy roots (Figure 5B and Supplementary Figure S2). Additionally, they all showed earlier or higher induction in NIL-J than NIL-j soybean plants or in J-OE hairy roots than in WT plants in response to NaCl (Figures 5A,B and Supplementary Figure S2). These data suggested that J expression regulates to some extend the expression of GmWRKY12, GmWRKY27, GmWRKY54, GmNAC11, and GmSIN1 and can improve NaCl tolerance in soybean.

Figure 5. J positively regulating the expression of salt stress–tolerant genes in soybean. (A) The transcription levels of GmWRKY12, GmWRKY27, GmWRKY54, GmNAC11, and GmSIN1 in 15-day-old seedlings of NIL-J and NIL-j soybean plant exposed to either 0 mM (mock) or 150 mM NaCl for 6 h; data obtained by qRT-PCR. (B) The transcription levels of GmWRKY12, GmWRKY27, GmWRKY54, GmNAC11, and GmSIN1 in J or GFP (Control) overexpressing soybean hairy root and exposed to either 0 mM (mock) or 150 mM NaCl; data obtained by qRT-PCR. Significant differences were analyzed based on the results of three biological replications (Student’s t-test: **P < 0.01). Bars indicate standard error of the mean.

To engineer salt-tolerant soybean varieties, it is crucial to identify key components of the plant salt-tolerance network. Although some salt-tolerance genes have been identified in soybean, knowledge about the mechanisms by which they work is still scarce. In this study we investigated the potential role and mechanism for one such candidate, named J, for which the Arabidopsis-ortholog AtELF3 may be involved in stress responses (Lu et al., 2017). Recently, research showed that AtELF3 enhances the resilience to NaCl stress and plays a key role in the repression of ROS production under NaCl stress in Arabidopsis (Sakuraba et al., 2017). Consistent with these observations, we demonstrated that J improved NaCl tolerance in soybean plants. This finding suggested that the ELF3 homologous gene may have a similar function in response to NaCl stress in other crops.

It has been reported that WRKY family TFs play an important role in response to NaCl stress in soybean (Zhou et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2015; Song et al., 2016; Shi et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2018). Zhou et al. (2008) identified 64 GmWRKY genes before the soybean genome was sequenced and confirmed that GmWRKY13, 21 and 54 genes were involved in NaCl stress. Yu et al. (2016) identified 188 soybean WRKY genes genome-wide, and 66 of the genes have been shown to respond rapidly and transiently to the imposition of NaCl stress. In the latest version of the soybean genome (Wm82.a2v1), 176 GmWRKY TFs were identified and the expression of three GmWRKY genes increased under NaCl treatment (Song et al., 2016). In addition, some NAC TFs have been involved in NaCl stress responses (Hao et al., 2011; Melo et al., 2018; Li et al., 2019). For example, overexpression of GmNAC11 resulted in enhanced tolerance to NaCl stress (Hao et al., 2011). In this study, we found that J upregulated 64 WRKY-family genes and 16 NAC-family genes by transcriptomic analysis. Based on RNA-Seq and bioinformatics methods, we found that 24 WRKY-family genes and two NAC-family genes may have participated in response to NaCl in soybean. We also confirmed that J positively regulated the expression of GmWRKY12, GmWRKY27, GmWRKY54, GmNAC11, and GmSIN1, which encoded a positive effect on NaCl tolerance in soybean (Zhou et al., 2008; Hao et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2015; Shi et al., 2018; Li et al., 2019). AtELF3 participated in the evening (AtELF3-AtELF4-AtLUX) complex of the transcriptional repression of downstream genes (Nusinow et al., 2011). A recent study revealed that AtELF3 indirectly binds to the AtPIF4 promoter and represses the expression of AtPIF4. AtPIF4 directly downregulates the transcription of JUNGBRUNNEN1 (JUB1/ANAC042), encoding a TF that upregulates the expression of NaCl stress–tolerant genes (Sakuraba et al., 2017). Thus, we speculated that J may indirectly regulate the transcription of GmWRKY and GmNAC genes, which positively regulated NaCl stress response pathways in soybean. In future work, we will identify whether or not J directly regulates genes in soybean NaCl stress response pathways.

Overall, our results showed that J transcription was activated under NaCl stress in soybean. and J could positively regulate the expression of salt-responsive genes in soybean. Our findings indicate that J may function in plant survival under high NaCl levels, and may provide a target for genetically designing and breeding of more salt-tolerant soybean.

The datasets generated by this study can be found in the NCBI using accession number PRJNA605480.

LD, FK, and BL designed the experiments and managed the projects. QC, ZG, and YW performed the experiments. SL, ZH, HL, and HX performed the data analysis. LD and QC wrote the manuscript.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31901568, 31725021, 31771815, and 31701445). This work was also funded by the National Key R&D Program of China (2017YFE0111000 and 2016YFD0100400).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We thank LetPub (www.letpub.com) for its linguistic assistance during the preparation of this manuscript. We also thank editor HA for revision of the manuscript.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2020.00272/full#supplementary-material

FIGURE S1 | Expression of transgenes validated by qRT-PCR. (A) Transgenic hairy root expressing of GFP. (B) Transgenic hairy root expressing of J. Significant differences were analyzed based on the results of three biological replications (Student’s t test: **P < 0.01). Bars indicate standard error of the mean. N ≥ 12. Error bars = s.e.m.

FIGURE S2 | J positively regulating the expression of NaCl stress tolerance genes in soybean. (A) The transcript levels of GmWRKY12, GmWRKY27, GmWRKY54, GmNAC11, and GmSIN1 in Fifteen-day-old seedlings of NIL-J and NIL-j soybean plant exposed to either 0 mM (mock) or 150 mM NaCl for 6 h; data obtained by qRT-PCR. (B) The transcript levels of GmWRKY12, GmWRKY27, GmWRKY54, GmNAC11, and GmSIN1 in J or GFP (Control) overexpressed soybean hairy root and exposed to either 0 mM (mock) or 150 mM NaCl; data obtained by qRT-PCR. All data were normalized to levels of amplified soybean EF1β. Significant differences were analyzed based on the results of three biological replications (Student’s t test: **P < 0.01). Bars indicate standard error of the mean.

TABLE S1 | Primers used for this study.

DATA S1 | List of genes with significant expression changes.

Anders, S., and Huber, W. (2010). Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 11:R106. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106

Ashraf, M. (1994). Breeding for salinity tolerance in plants. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 13, 17–42. doi: 10.1080/07352689409701906

Chen, H., Cui, S., Fu, S., Cai, J. Y., and Yu, D. Y. (2008). Identification of quantitative trait loci associated with salt tolerance during seedling growth in soybean (Glycine max L.). Aust. J. Agric. Res. 59, 1086–1091. doi: 10.1071/AR08104

Chen, H. T., Chen, X., Gu, H. P., Wu, B. Y., Zhang, H. M., Yuan, X. X., et al. (2014). GmHKT1;4, a novel soybean gene regulating Na+/K+ ratios in roots enhances salt tolerance in transgenic plants. Plant Growth Regul. 73, 299–308. doi: 10.1007/s10725-014-9890-3

Cheng, Q., Dong, L. D., Gao, T. J., Liu, T. F., Li, N. H., Wang, L., et al. (2018). The bHLH transcription factor GmPIB1 facilitates resistance to Phytophthora sojae in Glycine max. J. Exp. Bot. 69, 2527–2541. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ery103

Cheng, Q., Dong, L. D., Su, T., Li, T. Y., Gan, Z. R., Nan, H. Y., et al. (2019). CRISPR/Cas9-mediated targeted mutagenesis of GmLHY genes alters plant height and internode length in soybean. BMC Plant Biol. 19:562. doi: 10.1186/s12870-019-2145-8

Do, T. D., Chen, H. T., Hien, V. T., Hamwieh, A., Yamada, T., Sato, T., et al. (2016). Ncl synchronously regulates Na+, K+, and Cl- in soybean and greatly increases the grain yield in saline field conditions. Sci. Rep. 6:19147. doi: 10.1038/srep19147

Do, T. D., Vuong, T. D., Dunn, D., Smothers, S., Patil, G., Yungbluth, D. C., et al. (2018). Mapping and confirmation of loci for salt tolerance in a novel soybean germplasm, Fiskeby III. Theor. Appl. Genet. 131, 513–524. doi: 10.1007/s00122-017-3015-0

Gamborg, O. L., Miller, R. A., and Ojima, K. (1968). Nutrient requirement of suspensions cultures of soybean root cells. Exp. Cell Res. 50:151. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(68)90403-5

Guan, R. X., Qu, Y., Guo, Y., Yu, L. L., Liu, Y., Jiang, J. Y., et al. (2014). Salinity tolerance in soybean is modulated by natural variation in GmSALT3. Plant J. 80, 937–950. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12695

Ha, B. K., Vuong, T. D., Velusamy, V., Nguyen, H. T., Shannon, J. G., and Lee, J. D. (2013). Genetic mapping of quantitative trait loci conditioning salt tolerance in wild soybean (Glycine soja) PI 483463. Euphytica 193, 79–88. doi: 10.1007/s10681-013-0944-9

Hamwieh, A., Do, D. D., Cong, H., Benitez, E. R., Takahashi, R., Xu, D. H., et al. (2011). Identification and validation of a major QTL for salt tolerance in soybean. Euphytica 79, 451–459. doi: 10.1007/s10681-011-0347-8

Hamwieh, A., and Xu, D. H. (2008). Conserved salt tolerance quantitative trait locus (QTL) in wild and cultivated soybeans. Breed. Sci. 58, 355–359. doi: 10.1270/jsbbs.58.355

Hao, Y. J., Wei, W., Song, Q. X., Chen, H. W., Zhang, Y. Q., Wang, F., et al. (2011). Soybean NAC transcription factors promote abiotic stress tolerance and lateral root formation in transgenic plants. Plant J. 68, 302–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04687.x

Jian, B., Liu, B., Bi, Y. R., Hou, W. S., Wu, C. X., and Han, T. F. (2008). Validation of internal control for gene expression study in soybean by quantitative real-time PCR. BMC Mol. Biol. 9:59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-9-59

Lee, G. J., Carter, T. E. Jr., Villagarcia, M. R., Li, Z., Zhou, X., Gibbs, M. O., et al. (2004). A major QTL conditioning salt tolerance in S-100 soybean and descendent cultivars. Theor. Appl. Genet. 109, 1610–1619. doi: 10.1007/s00122-004-1783-9

Li, M., Hu, Z., Jiang, Q. Y., Sun, X. J., Guo, Y., Qi, J. C., et al. (2017). GmNAC15 overexpression in hairy roots enhances salt tolerance in soybean. J. Integr. Agr. 16, 60345–60347. doi: 10.1016/S2095-3119(17)61721-0

Li, S., Wang, N., Ji, D. D., Zhang, W. W., Wang, Y., Yu, Y. C., et al. (2019). A GmSIN1/GmNCED3s/GmRbohBs feed-forward loop acts as a signal amplifier that regulates root growth in soybean exposed to salt stress. Plant Cell 31, 2107–2130. doi: 10.1105/tpc.18.00662

Liu, X. L., Covington, M. F., Fankhauser, C., Chory, J., and Wagner, D. R. (2001). ELF3 encodes a circadian clock-regulated nuclear protein that functions in an Arabidopsis PHYB signal transduction pathway. Plant Cell 13, 1293–1304. doi: 10.2307/3871296

Lu, S., Zhao, X., Hu, Y., Liu, S., Nan, H., Li, X., et al. (2017). Natural variation at the soybean j locus improves adaptation to the tropics and enhances yield. Nat.Genet. 49, 773–779. doi: 10.1038/ng.3819

Melo, B. P., Fraga, O. T., Silva, J. C. F., Ferreira, D. O., Brustolini, O. J. B., Carpinetti, P. A., et al. (2018). Revisiting the soybean GmNAC superfamily. Front. Plant Sci. 9:1864. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01864

Munns, R., and Tester, M. (2008). Mechanisms of salinity tolerance. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 59, 651–668. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092911

Murashige, T., and Skoog, F. (1962). A revised medium for rapid growth and bio assays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol. Plant 15:473. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1962.tb08052.x

Nusinow, D. A., Helfer, A., Hamilton, E. E., King, J. J., Imaizumi, T., Schultz, T. F., et al. (2011). The ELF4-ELF3-LUX complex links the circadian clock to diurnal control of hypocotyl growth. Nature 475, 398–402. doi: 10.1038/nature10182

Papiernik, S. K., Grieve, C. M., Lesch, S. M., and Yates, S. R. (2005). Effects of salinity, imazethapyr, and chlorimuron application on soybean growth and yield. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 36, 951–967. doi: 10.1081/CSS-200050280

Parker, M. B., Gascho, G., and Gaines, T. (1983). Chloride toxicity of soybeans grown on Atlantic coast flatwoods soils. Agron. J. 75, 439–443. doi: 10.2134/agronj1983.00021962007500030005x

Patil, G., Do, T., Vuong, T. D., Valliyodan, B., Lee, J. D., Chaudhary, J., et al. (2016). Genomic-assisted haplotype analysis and the development of high-throughput SNP markers for salinity tolerance in soybean. Sci. Rep. 6:19199. doi: 10.1038/srep19199

Qi, X. P., Li, M. W., Xie, M., Liu, X., Ni, M., Shao, G. H., et al. (2014). Identification of a novel salt tolerance gene in wild soybean by whole-genome sequencing. Nat. Commun. 5:4340. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5340

Sakuraba, Y., Bülbül, S., Piao, W. L., Choi, G., and Paek, N. C. (2017). Arabidopsis EARLY FLOWERING3 increases salt tolerance by suppressing salt stress response pathways. Plant J. 92, 1106–1120. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13747

Shi, W. Y., Du, Y. T., Ma, J., Min, D. H., Jin, L. G., Chen, J., et al. (2018). The WRKY transcription factor GmWRKY12 confers drought and salt tolerance in soybean. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19:4087. doi: 10.3390/ijms19124087

Song, H., Wang, P., Hou, L., Zhao, S., Zhao, C., Xia, H., et al. (2016). Global analysis of WRKY genes and their response to dehydration and salt stress in soybean. Front. Plant Sci. 7:9. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00009

Trapnell, C., Pachter, L., and Salzberg, S. L. (2009). TopHat: discovering splice junctions with RNA-seq. Bioinformatics 25, 1105–1111. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp120

Wang, F. F., Chen, H. W., Li, Q. T., Wei, W., Li, W., Zhang, W. K., et al. (2015). GmWRKY27 interacts with GmMYB174 to reduce expression of GmNAC29 for stress tolerance in soybean plants. Plant J. 83, 224–236. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12879

Wei, P. P., Wang, L. C., Liu, A., Yu, B. J., and Lam, H. M. (2016). GmCLC1 confers enhanced salt tolerance through regulating chloride accumulation in soybean. Front. Plant Sci. 7:1082. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01082

Xu, Z., Raza, Q., Xu, L., He, X., Huang, Y., Yi, J., et al. (2018). GmWRKY49, a salt-responsive nuclear protein, improved root length and governed better salinity tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 9:809. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00809

Young, M. D., Wakefield, M. J., Smyth, G. K., and Oshlack, A. (2010). Gene ontology analysis for RNA-seq: accounting for selection bias. Genome Biol. 11:R14. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-2-r14

Yu, Y., Wang, N., Hu, R., and Xiang, F. (2016). Genome-wide identification of soybean WRKY transcription factors in response to salt stress. Springerplus 5:920. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-2647-x

Zagotta, M. T., Hicks, K. A., Jacobs, C. I., Young, J. C., Hangarter, R. P., and Meeks-Wagner, D. R. (1996). The Arabidopsis ELF3 gene regulates vegetative photomorphogenesis and the photoperiodic induction of flowering. Plant J. 10, 691–702. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1996.10040691.x

Zeng, A., Chen, P., Korth, K., Hancock, F., Pereira, A., Brye, K., et al. (2017). Genome-wide association study (GWAS) of salt tolerance in worldwide soybean germplasm lines. Mol. Breed. 37, 1–14. doi: 10.1007/s11032-017-0634-8

Zhang, G. Y., Chen, M., Li, L., Xu, Z., Chen, X., Guo, J., et al. (2009). Overexpression of the soybean GmERF3 gene, an AP2/ERF type transcription factor for increased tolerances to salt, drought, and diseases in transgenic tobacco. J. Exp. Bot. 60, 3781–3796. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp214

Zhou, Q. Y., Tian, A. G., Zou, H. F., Xie, Z. M., Lei, G., Huang, J., et al. (2008). Soybean WRKY-type transcription factor genes, GmWRKY13, GmWRKY21, and GmWRKY54, confer differential tolerance to abiotic stresses in transgenic Arabidopsis plants. Plant Biotechnol. J. 6, 486–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2008.00336.x

Keywords: Soybean, J, transcription factor, hairy roots, salt tolerance, RNA-seq

Citation: Cheng Q, Gan Z, Wang Y, Lu S, Hou Z, Li H, Xiang H, Liu B, Kong F and Dong L (2020) The Soybean Gene J Contributes to Salt Stress Tolerance by Up-Regulating Salt-Responsive Genes. Front. Plant Sci. 11:272. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.00272

Received: 29 September 2019; Accepted: 21 February 2020;

Published: 17 March 2020.

Edited by:

Han Asard, University of Antwerp, BelgiumReviewed by:

Yucheng Wang, Northeast Forestry University, ChinaCopyright © 2020 Cheng, Gan, Wang, Lu, Hou, Li, Xiang, Liu, Kong and Dong. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Baohui Liu, bGl1YmhAaWdhLmFjLmNu; Fanjiang Kong, a29uZ2ZqQGd6aHUuZWR1LmNu; Lidong Dong, ZG9uZ19sZEBnemh1LmVkdS5jbg==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.