94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Plant Sci. , 26 February 2020

Sec. Plant Abiotic Stress

Volume 11 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2020.00219

Muhammad Ali1,2

Muhammad Ali1,2 Izhar Muhammad3

Izhar Muhammad3 Saeed ul Haq1

Saeed ul Haq1 Mukhtar Alam4

Mukhtar Alam4 Abdul Mateen Khattak5

Abdul Mateen Khattak5 Kashif Akhtar6

Kashif Akhtar6 Hidayat Ullah4

Hidayat Ullah4 Abid Khan1

Abid Khan1 Gang Lu2*

Gang Lu2* Zhen-Hui Gong1*

Zhen-Hui Gong1*Extreme environmental conditions seriously affect crop growth and development, resulting in substantial reduction in yield and quality. However, chitin-binding proteins (CBP) family member CaChiVI2 plays a crucial role in eliminating the impact of adverse environmental conditions, such as cold and salt stress. Here, for the first time it was discovered that CaChiVI2 (Capana08g001237) gene of pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) had a role in resistance to heat stress and physiological processes. The full-length open-reading frame (ORF) of CaChiVI2 (606-bp, encoding 201-amino acids), was cloned into TRV2:CaChiVI2 vector for silencing. The CaChiVI2 gene carries heat shock elements (HSE, AAAAAATTTC) in the upstream region, and thereby shows sensitivity to heat stress at the transcriptional level. The silencing effect of CaChiVI2 in pepper resulted in increased susceptibility to heat and Phytophthora capsici infection. This was evident from the severe symptoms on leaves, the increase in superoxide (O2–) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) accumulation, higher malondialdehyde (MDA), relative electrolyte leakage (REL) and lower proline contents compared with control plants. Furthermore, the transcript level of other resistance responsive genes was also altered. In addition, the CaChiIV2-overexpression in Arabidopsis thaliana showed mild heat and drought stress symptoms and increased transcript level of a defense-related gene (AtHSA32), indicating its role in the co-regulation network of the plant. The CaChiVI2-overexpressed plants also showed a decrease in MDA contents and an increase in antioxidant enzyme activity and proline accumulation. In conclusion, the results suggest that CaChiVI2 gene plays a decisive role in heat and drought stress tolerance, as well as, provides resistance against P. capsici by reducing the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and modulating the expression of defense-related genes. The outcomes obtained here suggest that further studies should be conducted on plants adaptation mechanisms in variable environments.

In vivo cultivated crops inevitably suffer adverse effects of biotic (pathogens, diseases, etc.) and abiotic (temperature, heavy metals, salinity, and drought) stresses (Zhai et al., 2016; Kilasi et al., 2018). Consequently, there are heavy losses in both quality and quantity with estimated yield decreases up to 50% (Maxmen, 2013; Wang et al., 2013b). Being sessile in nature, plants face a number of unfavorable environmental conditions. Though they have evolved an array of sophisticated mechanisms to combat these stresses, the combination of stresses may adversely affect plant physiology and productivity (Obata et al., 2015). Over the period of time, plants have evolved various pathways to adapt to the changing environmental conditions in order to survive and reproduce. These have been studied extensively with considerable emphasis on individual stresses at the molecular levels (Ramegowda and Senthil-kumar, 2015). Besides, in plants undergoing stress, many proteins are denatured resulting in loss of natural functions causing serious losses in yield and quality (Li et al., 2010; Khurana et al., 2013; Zhai et al., 2017). When plants are in severe stress, they reprogramme a number of biochemical reactions. For example, reduction of proteins that can bind and disassemble the aggregations for re-folding to form native proteins and as a result avoid damages due to aggregations (Shan et al., 2007; Lambert et al., 2011; Ruibal et al., 2013; Personat et al., 2014; Li Z. et al., 2016). Additionally, the mechanism of plant adaptation is initiated by the combined effect of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and stress-induced signaling pathways, which are activated together and provide an immediate response to various external stimuli (Sewelam et al., 2016). Another elegant response to different environmental stimuli, such as high temperature, drought, and pathogen infection, is that accompanied by secondary messenger signaling pathways. These pathways are activated by the imbalance of intracellular concentrations of various molecular compounds (Ranty et al., 2016). Abscisic acid (ABA) is linked with the plants responses to biotic and abiotic stresses through regulation of stomatal apertures and up-regulation of defense-related genes (Lim et al., 2015; Sah et al., 2016). Sets of defense-related genes against heat shock and drought stress, i.e., HSP20, PR-2, and CBP gene families, are reported to have a role in effector-triggered immunity (ETI), relying on intensity and time of the interacting signaling components (Tsuda and Katagiri, 2010; Thomma et al., 2011). Among the defense-related genes, chitin-binding protein genes family contributes significantly in plants adaptability and tolerance (Hejgaard et al., 1992; Ali et al., 2018). There are some CBP-encoded enzymes, which show high response during environmental stresses such as cold and high salt concentration. Furthermore, they play their contributing role in physiological processes of plants, such as ethylene production and embryogenesis (Fukamizo et al., 2003; Hamid et al., 2013). Previously, we identified 16 putative genes of CBP family in pepper plant. The transcriptomic analysis revealed that CaChiVI2 gene had the most remarkable motif “AAAAAATTTC.” It was heat stress responsive protein highly induced by ABA hormone (Ali et al., 2018).

Pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) is a profitable crop extensively used as a green vegetable, as a spice in food, and as an innate source of natural coloring (Wang et al., 2017; Baoling, 2018). Pepper is thermophilic in nature, i.e., its growth and development is susceptible to extreme temperature and water deficiency (Guo et al., 2014). Pepper crop faces a number of challenges during cultivation period, especially in the summer, when water is deficient and temperature is too high. Such conditions favor Phytophthora blight disease, caused by the oomycete Phytophthora capsici. The infection significantly inhibits pollination, fertilization, and seed setting (Erickson and Markhart, 2002; Pagamas and Nawata, 2008). The severity of the P. capsici infection can have a devastating effect on plant morphology and growth. These include symptoms such as damping-off, leaf browning, senescence wilting, and dwarfing that cause plant death ultimately (Hausbeck and Lamour, 2004; Sy et al., 2005; Lamour et al., 2012; Zhang H.-X. et al., 2016).

Thus, it was essential to investigate this issue. Due to lack of conclusive evidence, it was difficult to prove that CaChiVI2 gene was potentially involved in heat tolerance, drought stress, and P. capsici infection. Therefore, we extended our work to characterize CaChiVI2 in pepper plant for the mentioned purpose. The gene is known for its role in regulating stress responses. The purpose of this study was to generate a meaningful background for further research through silencing of the target gene in pepper and over-expressing in Arabidopsis via transgenic approaches. Moreover, we were also interested in the physiological responses and changes induced by heat stress and disease susceptibility or tolerance through inoculation with P. capsici.

Pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) cultivar AA3 maintained in Vegetable Plant Biotechnology and Germplasm Innovation lab, Northwest A&F University-China was studied in the present work. The growth conditions for pepper seedlings were 22/18°C (day/night) temperature with a 16 h photoperiod (i.e., 16 h light and 8 h dark cycle) and 65% relative humidity. Arabidopsis ecotype Columbia-0 (Col-0) was also cultivated at 25/20°C (day/night) temperature and the above-mentioned photoperiod and humidity conditions for overexpression of CaChiVI2-gene.

The protein sequences of the chitin-binding protein family (CBP) were aligned by ClustalW1. The phylogenetic tree was built using iTOL2 (Letunic and Bork, 2016). Cis-regulatory elements (1500-bp upstream region) were searched by PlantCARE online server3 (Lescot et al., 2002). Publicly available transcriptomic data of root and leaf for pepper cultivar “Zunla” were obtained from the online server4, and the genomic database was generated by following Liu Z. et al. (2017) and Yu et al. (2017) method and the data were presented in line-graphs (CaChiVI2 sequence shown in Supplementary Table S1).

The total-RNA was extracted as explained in our recently published papers (Ali et al., 2018; Khan et al., 2018). The first chain was synthesized by the Primer ScriptTM Kit (TaKaRa, Dalian, China). The iQ5.0 Bio-Rad iCycler thermocycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, United States) was used for qRT-PCR, and SYBRR Premix Ex TaqTM II (TaKaRa) was used for the reaction. Pepper ubiquitin-binding gene CaUBI3 (Wan et al., 2011) and Arabidopsis Atactin2 was used as a reference. Relative gene expression levels were calculated according to the comparative threshold (2–ΔΔCT) technique (Schmittgen and Livak, 2008; Muhammad et al., 2018). All primer pairs (Supplementary Table S2) used for qRT-PCR were designed by NCBI Primer-BLAST. The expression levels were normalized and presented the mean and standard deviation (+SD) of data were obtained from three independent biological experiments with three replicates.

The transient transformation technique was performed using Nicotiana benthamiana epidermal cells to detect the protein localization of target gene (Jin et al., 2019; Ma et al., 2019). The ORF fragment (1244-bp) of CaChiVI2 (primers in Supplementary Table S3) was inserted into the pVBG2307 vector regulated by CaMV 35S promoter and then transformed into GV3101 (Agrobacterium tumefaciens). The pVBG2307:GFP vector without the CaChiVI2 gene was used as a control. The Agrobacterium cells were infiltrated into 4-weeks-old tobacco plant leaves (Yu et al., 2017). In a growth chamber, agro-infiltrated plants were transferred for 2–3 days. OLYMPUS BX63 automated fluorescence microscope was used for the determination of epidermal cells (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

The virus induce gene silencing (VIGS) technique was performed for the knock-down of pepper CaChiVI2 gene, following the same approach explained by Liu et al. (2016). While for the construction of TRV2:CaChiVI2 vector, 230-bp CDS fragment using the specific primer pair (Supplementary Table S4) of CaChiVI2 gene with restriction enzymes sites EcoRI and XhoI was amplified through PCR. CaChiVI2 was cloned into the TRV2 vector, while TRV2:00 vector was used as a negative control, whereas the TRV2:CaPDS (phytoene desaturase gene) was used as a positive control. Subsequently, the vector was used to transform into an Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain (GV3101) using the freeze-thaw method (Wang et al., 2013c). Consequently, the TRV2:00, TRV2:CaPDS and TRV2:CaChiVI2 were activated with OD600 = 1.0. Afterward, the suspensions were infiltrated into the fully extended cotyledons leaves of pepper plants by using a 1.0 mL sterilized needleless syringe (Li et al., 2014; Feng et al., 2019). The infiltrated pepper plants were kept at 18–22°C in the growth chamber, maintaining the 16h/8h light/dark photoperiod as mentioned by Wang et al. (2013a). The leaf samples of the control and CaChiVI2-silenced plants were collected after 45 days when the TRV2:CaPDS injected leaves exhibited photo-bleaching phenotype and the silencing efficiency was measured by qRT-PCR. For the precision of results, the experiment was performed with three independent biological replicates.

The full-length of CaChiVI2 ORF fragment was cloned by cutting with restriction enzymes XbaI and KpnI. The amplified product from cDNA was recovered through a gene-specific primer pair (Supplementary Table S5) and further transferred into a pVBG2307 expression vector. For overexpression analysis, recombinant fusion vector was used to transform into Arabidopsis plants (ecotype Columbia-0, Col-0) via Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 (Clough and Bent, 1998; Guo et al., 2014). Positive transgenic lines were selected on MS-medium containing 50 mmol/L kanamycin. The transgenic lines were further grown for homozygosity till T3 generation. The T3 seeds were used for further experimental treatment.

Phytophthora capsici (PC strain) was obtained from our laboratory and the technique used for its inoculation was similar as described in our previous studies (Zhang et al., 2018; Ali et al., 2019). The roots were sampled at different days of interval (0, 1, 2, 4, and 8 dpi), immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C for further study. The authentication of data was checked by a repeat of three times for each treatment.

To examine the transcript pattern of CBP family genes, pepper seedlings (8-weeks-old) at the stage of six to eight true leaves were used for basic thermo-tolerance treatment. Pepper seedlings were incubated at 45°C and samples were collected at 0, 1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 h post-treatment. CaChiVI2-silenced and TRV2:00 (control) plants were used to analyze the functions of CaChiVI2 under heat and P. capsici inoculation. The seedlings were exposed to 45°C for heat stress, and samples were collected at different intervals of 0, 0.5, 1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 h. During stress treatment, seedlings were watered to avoid drought stress. Heat treated pepper plant leaves were collected for the validation of MDA content, total chlorophyll content and relative electrolyte leakage (REL) analysis at 0, 12 and 24 h.

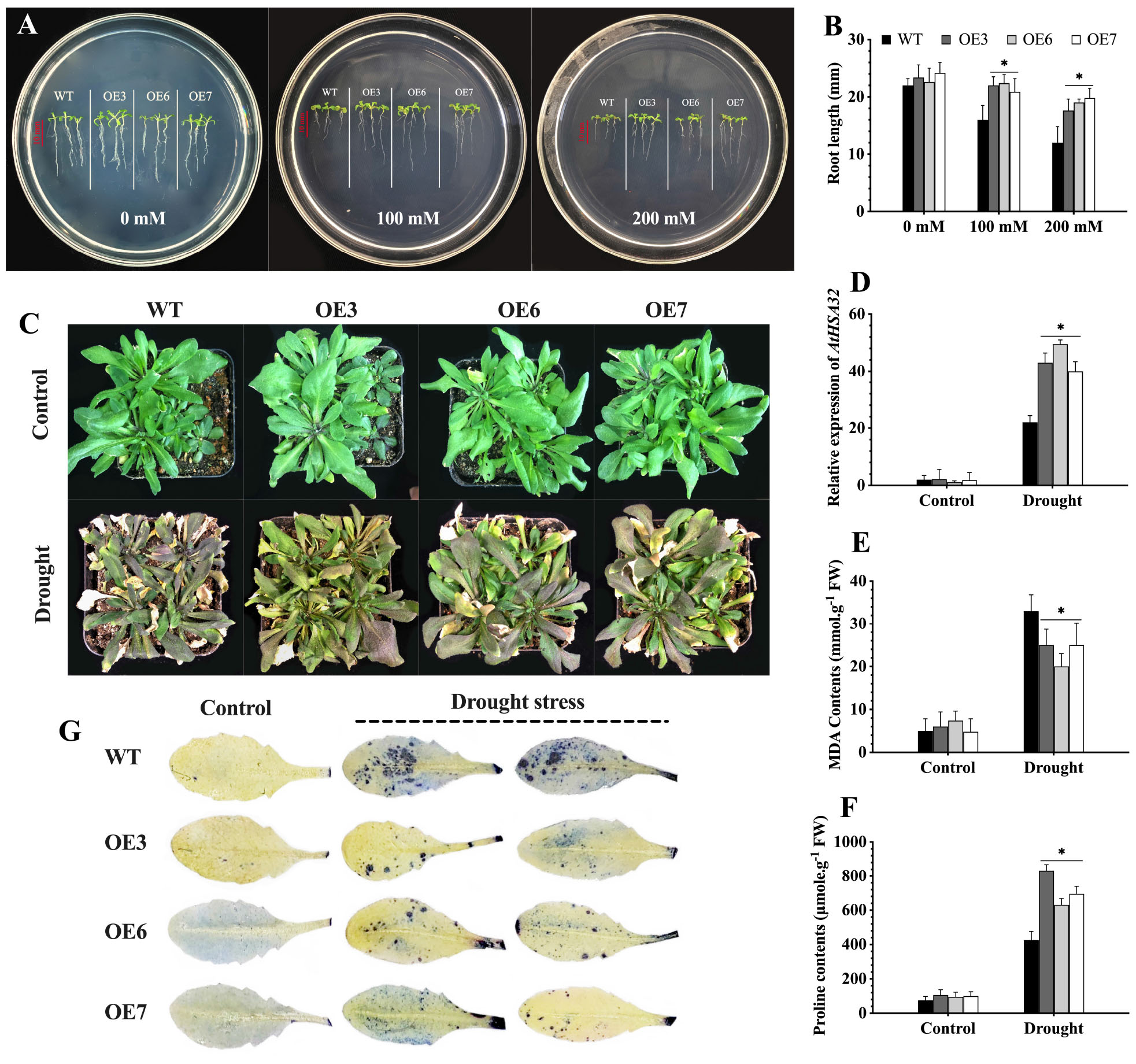

The CaChiVI2-overexpressed Arabidopsis lines (OE2, OE3, OE5, OE6, and OE7) were selected. T3 homozygous lines (8-days old seedlings) grown on MS-media were incubated at 45°C to give heat stress for a period of 2 h. The seedlings were then shifted to growth chamber (22°C) for 7 days to recover and the survival rate was recorded (Guo et al., 2016). For drought stress, seeds were grown on MS-medium containing 0, 100- and 200-mM mannitol and the root length was measured 8 days post sowing. Furthermore, 3-weeks-old CaChiVI2-overexpressed and wild-type Arabidopsis lines grown in soil-media were used for the analysis of heat and drought stress tolerance.

The Arabidopsis plants were incubated for a period of 16 h at 40°C for heat stress treatment. Plants were irrigated frequently during treatment to avoid drought stress. Furthermore, for drought stress, water was withheld from the seedlings for 5-days, while in control treatment, seedlings were provided with standard watering conditions. Leaf samples were collected for MDA, proline, and extraction of RNA. Randomly six separate seedlings were used for sample collection and then instantly frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. The experiment was conducted with three independent biological replicates for the accuracy of data.

To measure the contributing parameters of CaChiVI2-silenced pepper plants and CaChiVI2-overexpressed Arabidopsis plants, samples (0.5 g) were collected and finely grinded in liquid nitrogen. The malondialdehyde (MDA) content was measured through thiobarbituric acid (TBA) reaction method (De Vos et al., 1991). For this, 1.5 mL of the extract supernatant was mixed with 2 mL 0.6% (w/v) TBA solution dissolved in 5% (v/v) trichloroacetic acid (TCA) and heated in boiling water for 10 min. The supernatant was used for determination of MDA at 450 and 532 nm wavelength and subtracted from the absorbance at 600 nm. The activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD) was estimated by the inhibition of nitro-blue tetrazolium (NBT). The supernatant volume was illuminated at 4000 Lux for 20 min, then SOD activity was quantified spectrophotometrically at 560 nm. Control was determined in dark (Stewart and Bewley, 1980). Peroxidase (POD) activity was determined through guaiacol method (Bestwick et al., 1998). The reaction mixture used consisted of 50 mL 0.05 M phosphate buffer (pH7.8), 19 μL 30% H2O2 (v/v) and 28 μL guaiacol. The enzyme extract (0.5 mL) was added and a total of 3.0 mL of the reaction mixture was placed into a cuvette. The increase in absorbance was recorded at 470 nm at 30 s intervals for 3 min. Proline estimation was done according to Bates et al. (1973). A 2 ml of aqueous extract was mixed with 2 ml of glacial acetic acid and 2 ml of acid ninhydrin reagent (1.25 g of ninhydrin, 30 ml of glacial acetic acid, and 20 ml of 6 M orthophosphoric acid) and heated at 100°C for 30 min. After cooling, the reaction mixture was partitioned against toluene (4 ml) and the absorbance of the organic phase was firm at 520 nm. The resulting values were compared with a standard curve constructed using known amounts of proline (Sigma, St Louis, MO, United States).

Histochemical staining’s were performed to detect superoxide radical (O2–) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) in leaves. The leaves were inserted in 0.1% nitro-blue tetrazolium (NBT) with 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.8) for O2– as described by Liu et al. (2012). For H2O2 detection, 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) solution was used in agroinfiltrated leaves. The leaves were incubated in 1.0 mg/mL DAB-HCl solution at room temperature, covered in dark for 12 h. Then de-stained by boiling in 95% ethanol for 5 min until the brown H2O2 spots on the leaves appeared (Thordal-Christensen et al., 1997; Kim et al., 2012). Relative electrolyte leakage (REL) was measured as per Feng et al. (2019), and the electrical conductivity percentage was calculated as REL (%) = C1/C2 × 100. For chlorophyll content, the readings were recorded on spectrophotometer after extracting into 80% (v/v) acetone (Arkus et al., 2005). Spectrophotometer (UV-1201 Shimadzu spectrophotometer, Japan) was used for all measurements.

IBM SPSS Statistics 25, United States were used for the statistical analysis. Significance differences between individual treatments were further analyzed at P ≤ 0.05 through Duncan Multiple Range (DMR) test. The analyzed data were expressed as mean and standard deviation (±SD). Three individual experiments were performed, and the data set for each biological replicate was used separately for analysis. The data were plotted by GraphPad Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, United States).

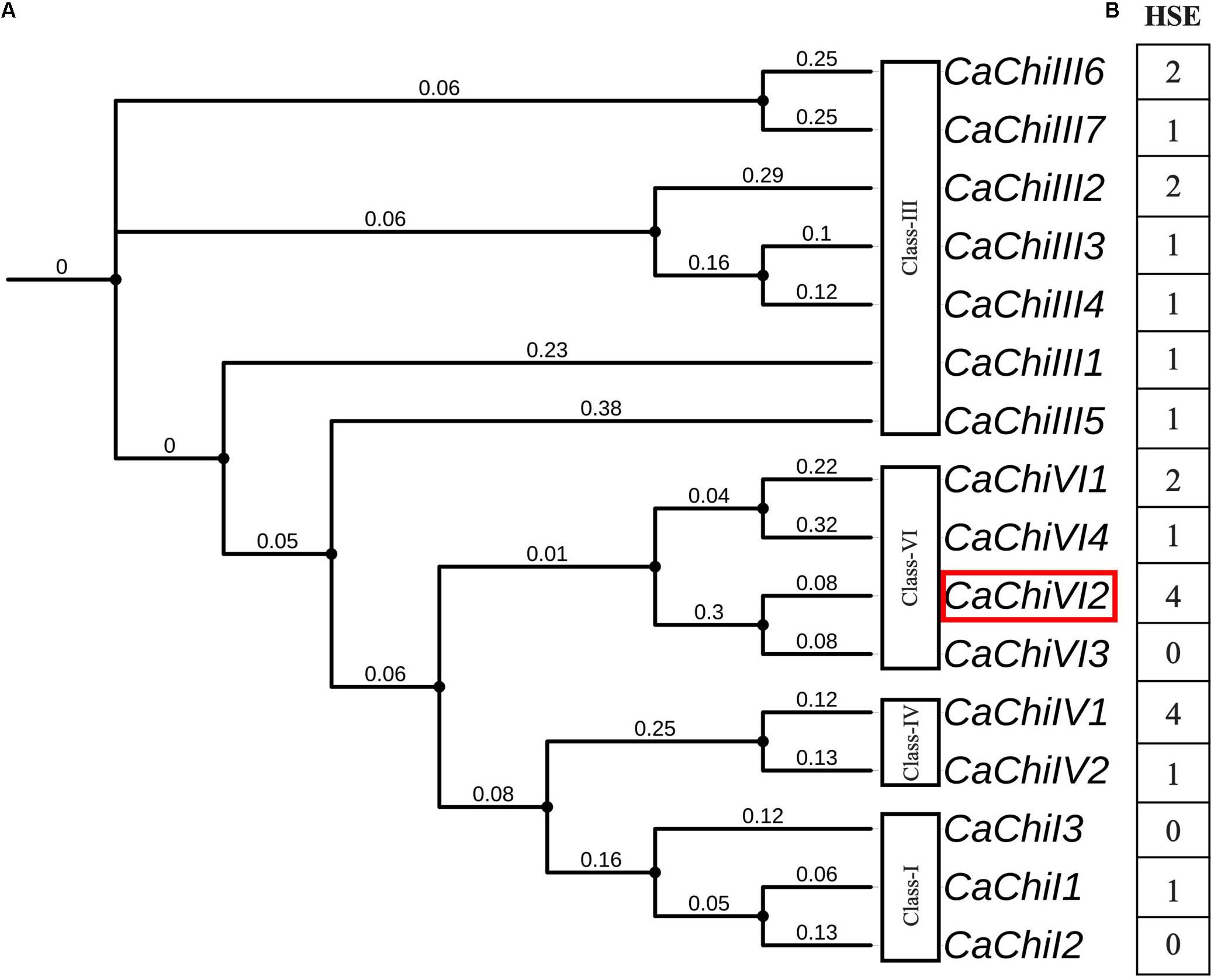

As previously reported, the evolutionary relationship between CaChiVI2 and pepper CBP homologs in other species was based on phylogenetic analysis (Ali et al., 2018). The analysis revealed that pepper CBP could be classified into four main classes with potentially similar functions. Among all the chitin-binding protein (CBP) family genes, we identified a putative gene named CaChiVI2 (Capana08g001237) (Figure 1A), which is re-derived from ‘Zunla’ database. The CaChiVI2 was cloned using cDNA extracted from pepper leaves of AA3 pure-line. The full-length CDS of CaChiVI2 cDNA consists of 606-bp and encodes 201 amino acids, while the genomic sequence contains 1203 nucleotides (Supplementary Table S6), including two exons and one intron (Ali et al., 2018). To investigate the possible cis-acting elements involved in the heat stimulation of defense-related genes, the 1.5 kb upstream region from the start codon (ATG) of all the CBP genes was analyzed with PlantCARE online server. The in silico analysis exhibited that heat stress elements (HSE) were available in the promoter region of 13 out of 16 members (Figure 1B) while the highest number (4) of HSE was found in CaChiIV1 and CaChiVI2.

Figure 1. Phylogenetic relationship and cis-acting elements of CBP family genes in pepper. (A) Phylogeny of pepper CBP genes using iTOL (https://itol.embl.de/). The red color rectangle indicates the target gene (B) Cis-acting elements in the promoter regions of CBP genes inferred from the PlantCARE website (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/). The highest number shows maximum, while the lowest shows minimum number of heat shock elements (HSE).

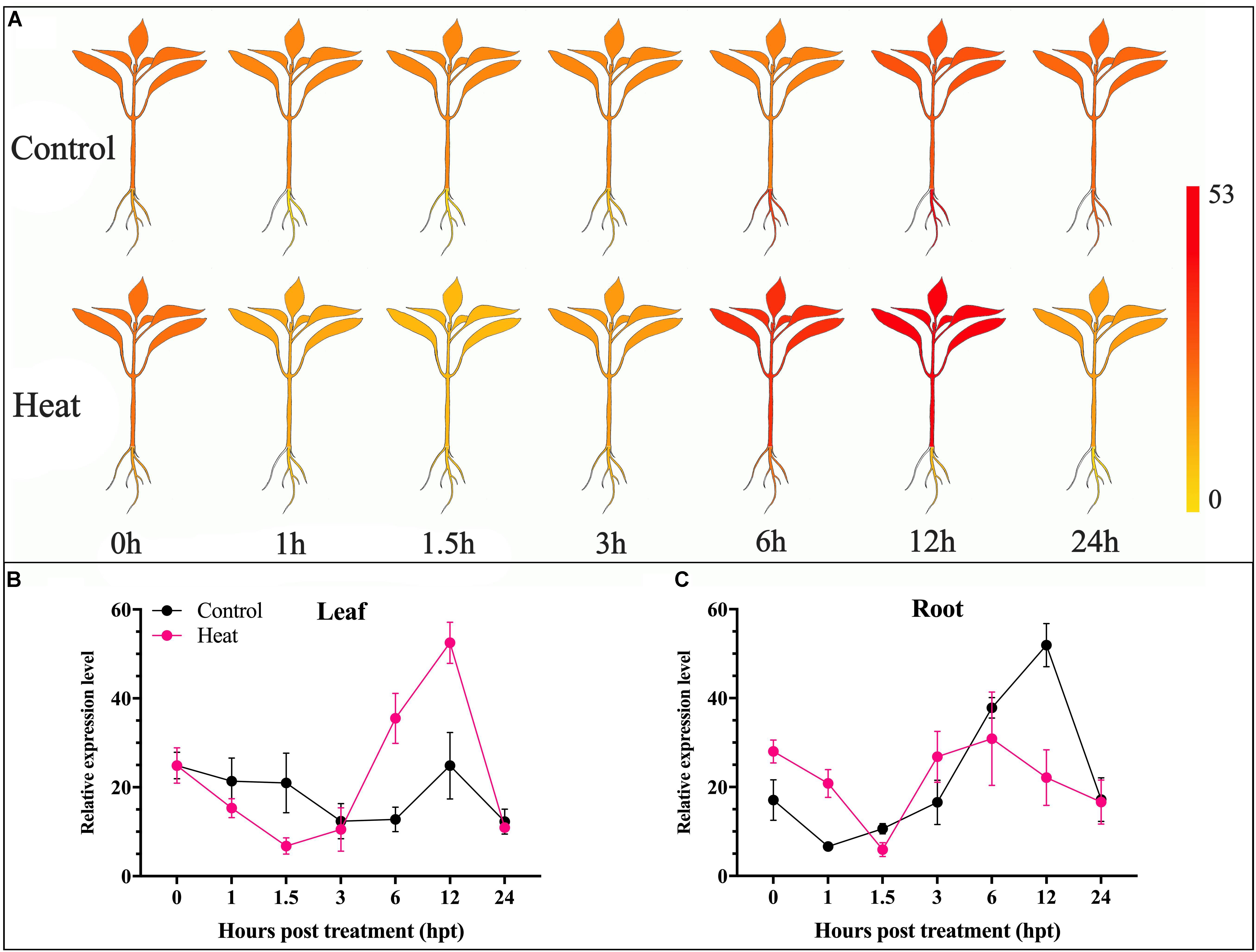

For further insight into the transcriptomic characteristics of CaChiVI2 in pepper roots and leaves under heat stress, we initially practiced in silico analysis from a publicly available transcriptomic database of pepper (Zunla cultivar) (Liu F. et al., 2017). The diagrams display the index of a transcript ranging from yellow to red (Figure 2A). The transcript level of CaChiVI2 in pepper revealed higher variance in distinct parts and at time intervals under heat stress, as demonstrated in Figures 2B,C. Moreover, the highest expression level (52.5) was noted in leaf tissue at 12 h interval followed by 35.5 at 6 h interval. In roots, the highest level (30.9) was recorded at 6 h interval. Overall, the in silico analysis revealed that expression in the leaf tissue was more elevated than the root.

Figure 2. Transcriptomic analysis of CaChiVI2 under heat stress. (A) The predicted expression level of CaChiVI2 at different interval (0, 1.5, 3, 6, 12, and 24 h). Results were presented in heat map; the dark-yellow color represents strong down-regulation, and dark-red color represents strong up-regulation. (B) Transcriptomic results of CaChiVI2 in the leaf of pepper plant under heat stress. (C) Transcriptomic results of CaChiVI2 in the root of pepper plant under heat stress. These results were retrieved from Zunla database (http://pepperhub.hzau.edu.cn).

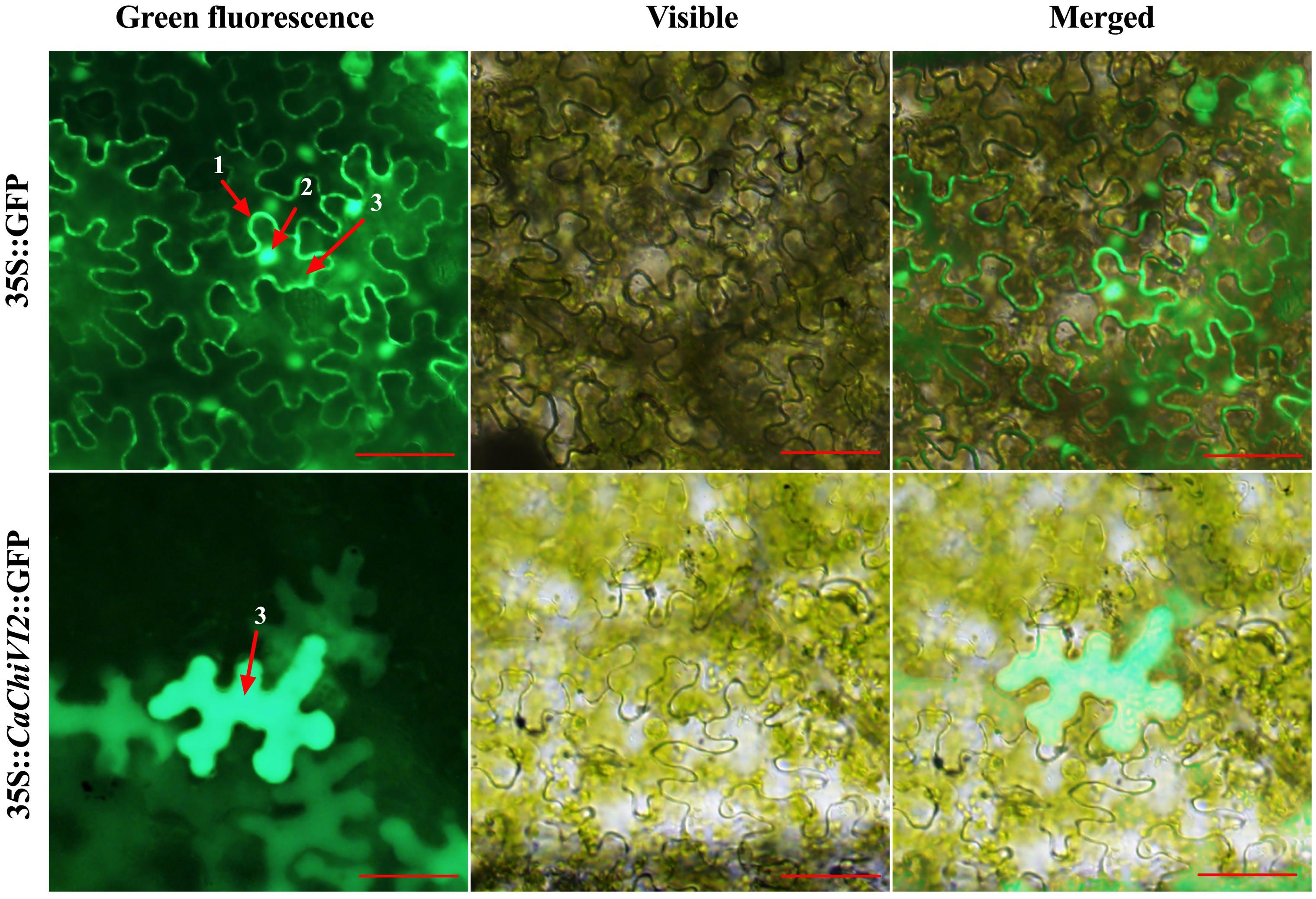

The ORF fragment of CaChiVI2 was recombined with the expression vector pVBG2307 that contained 35S promoter and reporter genes for green fluorescence protein (GFP). The pVBG2307:GFP and pVBG2307:CaChiVI2:GFP fused plasmids were infiltrated into Nicotiana benthamiana plants for CaChiVI2 expression in epidermal tissue (Jin et al., 2019; Ma et al., 2019). The confocal laser micrographs exhibit that 35S:CaChiVI2:GFP fused protein were localized only in the cytoplasm of the cell (Figure 3). On the other side, the pVBG2307:GFP (mock) vector, used as a control, was give signal in three main parts of the cell including cell membrane, cytoplasm and nucleus.

Figure 3. Protein localization of the pVBG2307:CaChiVI2:GFP in epidermal cells of tobacco leaves. pVBG2307:GFP was used as a control. The fluorescence was observed under a bright and fluorescent field. Every digit represents 1-cell membrane, 2-nucleus, and 3-cytoplasm, while red line indicate 100 μm.

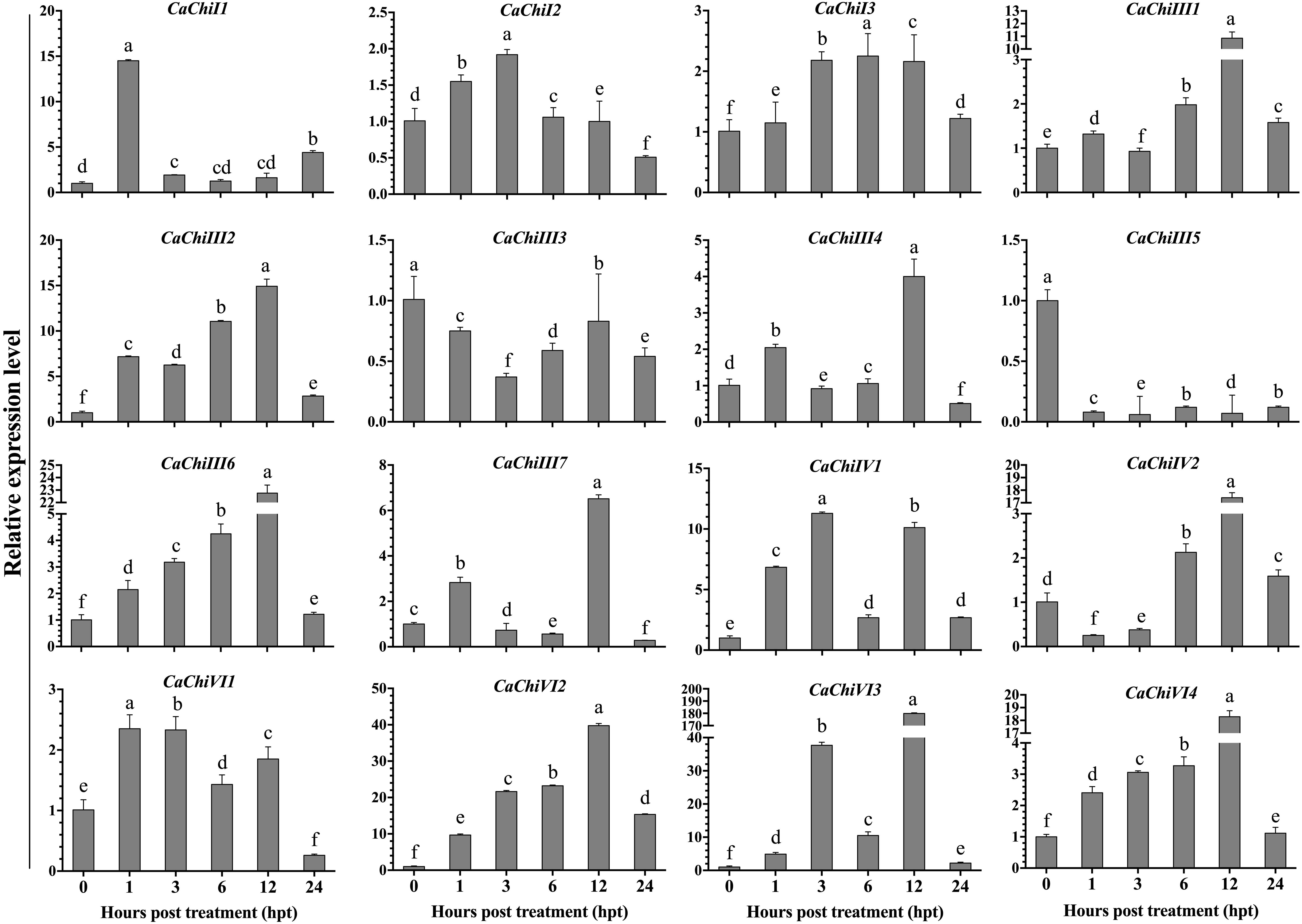

The seedlings of pepper plant were incubated at 45°C for heat stress to examine the transcript levels of CBP genes using qRT-PCR. The investigation revealed that different expression levels were found in different genes (Figure 4). Among all 16 genes, 14 were upregulated, while two genes (CaChiIII3 and CaChiIII5) were downregulated at each time point. The CaChiI1 initially expressed abruptly (14.5) at 1-h post-treatment then downregulated at all time points, whereas CaChiI2, CaChiI3, CaChiIII2, CaChiIII6, CaVhiVI1, CaChiVI2, and CaChiVI4 progressively showed increased expression at each time point, till slight downregulation at 24 hpt. The CaChiVI2 transcript level was the highest (39.76) at 12 hpt. Compared to other genes, its expression was significantly higher at every time point. Some members of CBP (CaChiIII1, CaChiIII4, CaChiIV1, and CaChiVI3) showed higher expression at some time points, though irregular changes were noticed in their expression level (Figure 4). Additionally, two genes (CaChiIII7 and CaChiIV2) exhibited no remarkable changes in transcript levels against heat stress and their expression was not predominantly upregulated at various interval of time.

Figure 4. The transcript level of CBP genes in response to heat stress. The plant tissues were sampled at different time points (0, 1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 h post heat treatment) and were examined by qRT-PCR. The mean values and ± SDs for three replicates are presented. Different letters (a–f) on the bars in each histogram represent significant differences at P ≤ 0.05 using Duncan Multiple Range (DMR) test.

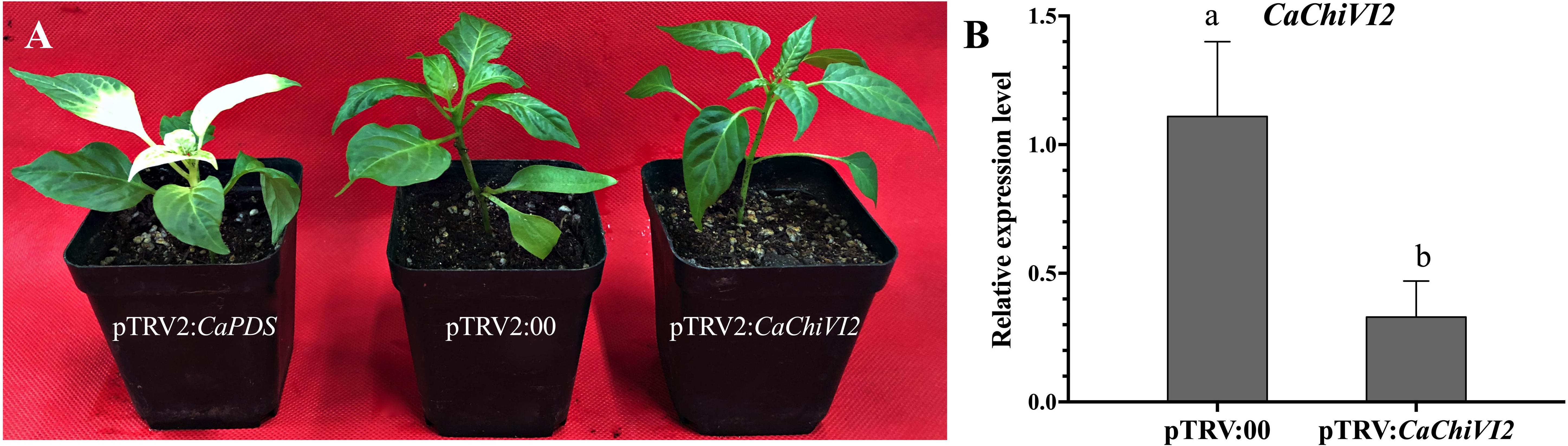

After 6-weeks of inoculation, the leaves of the positively controlled (pTRV2:CaPDS) plants exhibited photo-bleaching phenotype, which demonstrate the success of VIGS (Figure 5A). The silencing efficiency of pTRV2:CaChiVI2 (CaChiVI2-silenced) and pTRV2:00 (control) plants were detected by qRT-PCR. As shown in Figure 5A, there was no visual difference between pTRV2:CaChiVI2 and pTRV2:00 plants which grown in normal conditions and the silencing efficiency was around 71% (Figure 5B). Thus, CaChiVI2-silenced and controlled plants were used for further research.

Figure 5. The phenotypes and silencing efficiency analysis of CaChiVI2 pepper plants. (A) The phenotypes of TRV2:CaPDS, TRV2:00 and TRV2:CaChiVI2. (B) The silencing efficiency of CaChiVI2 in the leaves of CaChiVI2-silenced and empty vector (TRV2:00) pepper plants. The bars show the mean values of three biological replicates and the error bars denote the standard deviation (+SD). Small alphabets (a–b) on the bars represent significant differences at P ≤ 0.05.

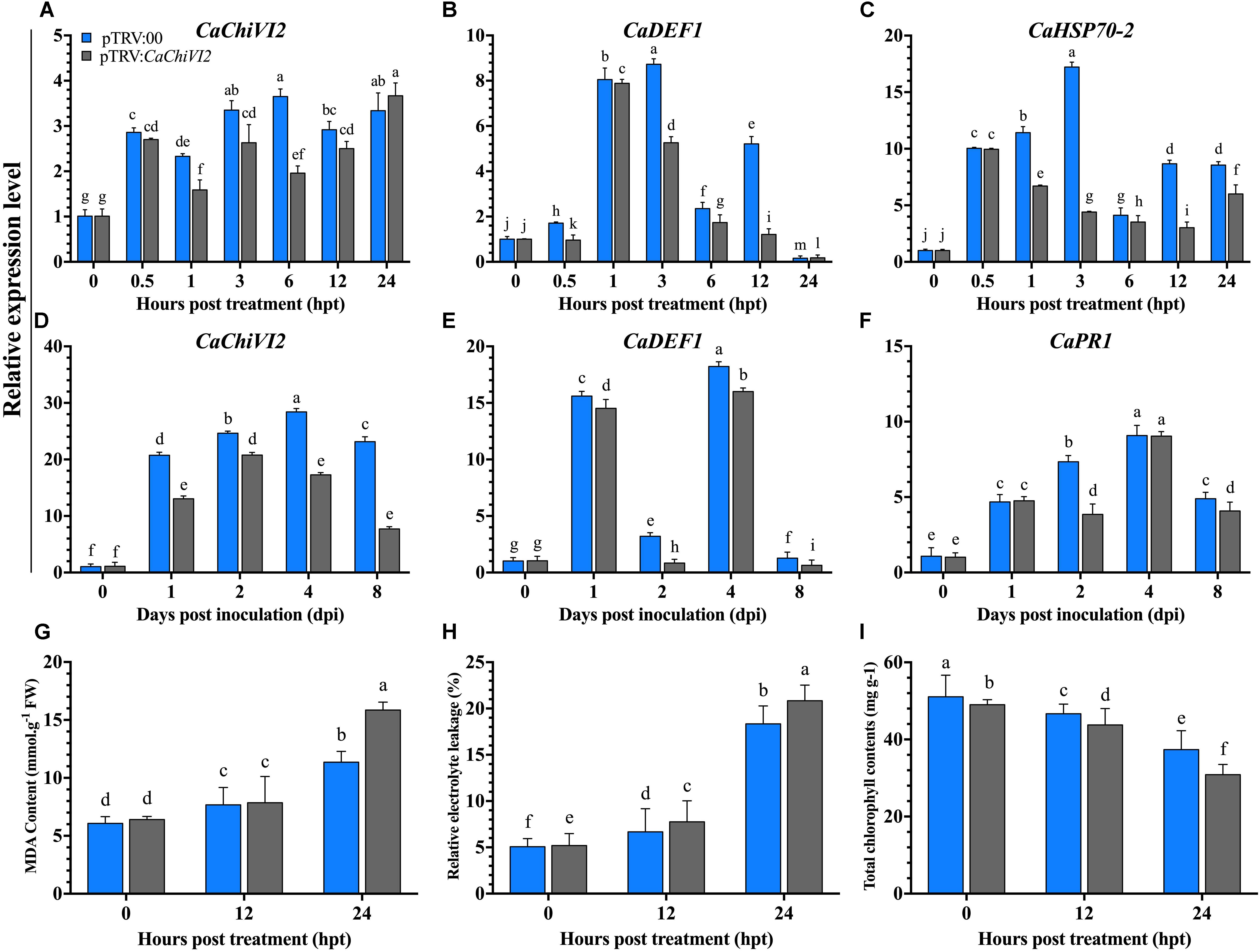

After heat stress treatment, the expression of CaChiVI2 was checked in both pTRV2:CaChiVI2 and pTRV2:00 plants. A remarkable difference was recorded in pTRV2:00 and pTRV2:CaChiVI2 samples at all the time points, which revealed that the expression level of CaChiVI2 was lower in pTRV2:CaChiVI2 compared to pTRV2:00. A huge difference of >50% was found between pTRV2:CaChiVI2 and pTRV2:00 at 6 h post-treatment (hpt) with values of 3.65 and 1.96 respectively (Figure 6A).

Figure 6. The CaChiVI2-silenced pepper plants tolerance to heat and P. capsici infection. (A–C) Transcript level of CaChiVI2, CaDEF1, and CaHSP70-2 under heat stress, (D–F) transcript level of CaChiVI2, CaDEF1, and CaPR1 during P. capsici inoculation. (G) MDA contents, (H) relative electrolyte-leakage, and (I) total chlorophyll content accumulation under heat stress. Mean values ± SDs for three replicates are shown. Different letters (a–m) in each individual histogram denote significant differences at P ≤ 0.05.

The regulation of other defense-related genes after the silencing of CaChiVI2 showed that the transcript levels of resistance responsive genes, such as CaHSP70-2 and CaDEF1 (Do et al., 2004) increased in both CaChiVI2-silenced and control plants. Their transcript was significant lower in CaChiVI2-silenced plants comparatively control (TRV2:00) plants, for all the tested time points (Figures 6B,C). For examination of functional specificity of CaChiVI2 under biotic stress, the TRV2:CaChiVI2 (silenced) and TRV2:00 (controlled) pepper plants were infected with P. capsici. A higher transcript level of CaChiVI2 was detected in control plants compared with CaChiVI2-silenced plants, with CaChiVI2 expressing 66% more in pTRV2:00 plants. As shown in Figure 6D, the silencing of CaChiVI2-gene had a significant tolerance role against P. capsici.

We further explored the expression levels of other stress responsive genes to find the interaction/role of CaChiVI2 with other resistance responsive genes by altering their expression. It was noted that after P. capsici inoculation, CaDEF1 (Do et al., 2004) and CaPR1 gave a positive response. Their transcript level in the pTRV2:00 plants was better than that of the TRV2:CaChiVI2 plants at all tested time points (Figures 6E,F).

After heat stress treatment, the MDA contents and REL in CaChiVI2-silenced plants were significantly higher than control plants (Figures 6G,H). More severe symptoms of wilting and yellowing were observed in CaChiVI2-silenced plants, which indicated that chlorophyll contents degraded more in pTRV2:CaChiVI2 plants (Figure 6I). Moreover, the recovery efficiency was also checked which revealed that pTRV2:00 plants recovered their growth quicker than TRV2:CaChiVI2 plants, when incubated at normal temperature (22°C) (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Phenotypes, heat stress recovery assay of the CaChiVI2-silenced (pTRV2:CaChiVI2) and control (pTRV2:00) plants after 5-days at 22°C.

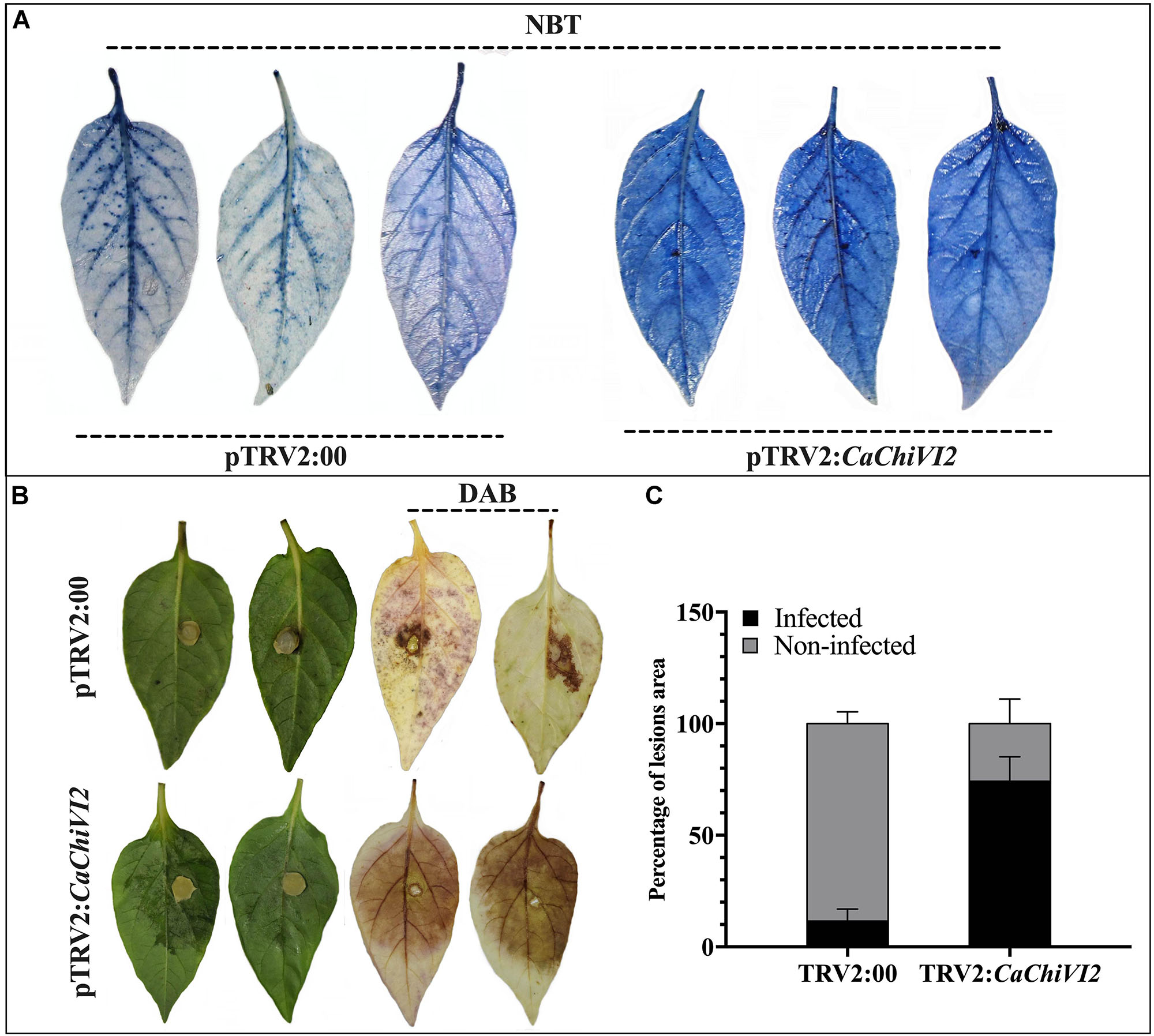

Production of ROS is a typical consequence once plants are in stress condition. We noticed a higher accumulation of superoxide (O2–) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) using NBT and DAB staining respectively. After heat stress, a higher production of O2– was detected in CaChiVI2-silenced plants, leaves (dark-blue color) compared with control plants (light-blue color) (Figure 8A). After 3 days of inculcation, the Phytophthora capsici lesions were detected on the isolated leaves of both TRV2:CaChiVI2 and TRV2:00 pepper plants. However, the infected areas and H2O2 accumulation were more pronounced in silenced plant versus control (Figure 8B). Quantitative analysis exhibited that disease infected area of TRV2:CaChiVI2 plants (>74%) was significantly more expanded than the TRV2:00 plants (11.6%) (Figure 8C).

Figure 8. Detection of O2– and H2O2 concentration in CaChiVI2-silenced and control pepper plants. (A) Heat stress symptoms appearance on detached leaves of TRV2:CaChiVI2 and TRV2:00 pepper plants, NBT staining shows detection of O2– concentration. (B) P. capsici symptoms (lesions) developed on pepper leaves of TRV2:CaChiVI2 and TRV2:00 plants, DAB staining shows detection of H2O2. (C) Percentage of the infected and non-infected areas of pepper leaves after P. capsici infection. The bars represent the means ± SD of three independent biological replicates.

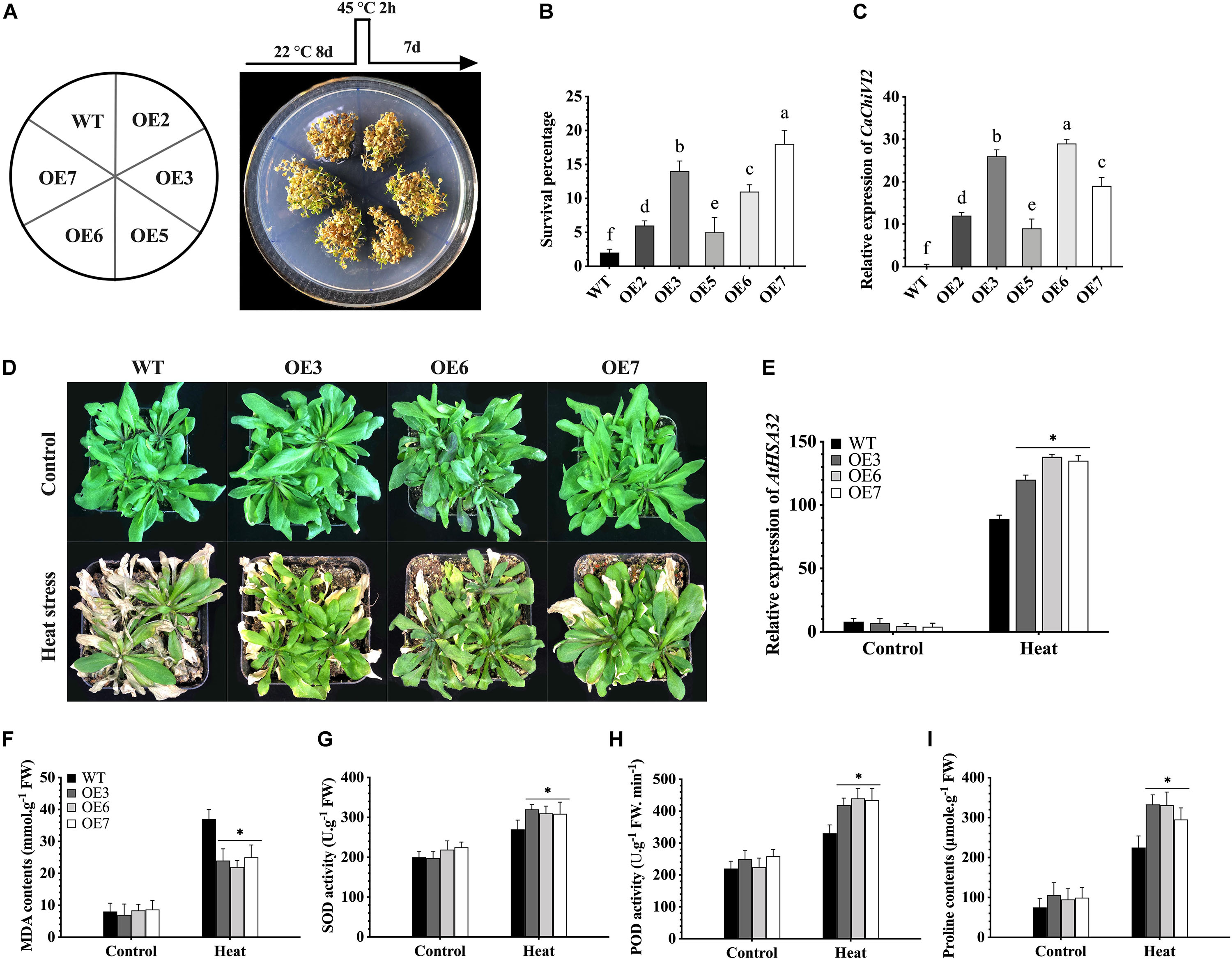

In order to select the best thermo-tolerant homozygous T3 lines for further analysis, wild-type (WT) and five CaChiVI2-overexpressed (OE2, OE3, OE5, OE6, and OE7) Arabidopsis lines were cultured on MS-media and were kept at 45°C (high temperature) for 2h. The CaChiVI2-overexpressed plants were then kept at 22°C for 7-days to recover and their survival rate was measured. The results exhibited that the survival rate of OE3, OE6, and OE7 lines was higher than WT, OE2, and OE5-lines (Figures 9A,B). Besides, some WT and transgenic Arabidopsis lines were grown in normal environmental conditions to detect the transcript levels of CaChiVI2 gene. As presented in Figure 9C, the transcript levels of CaChiVI2 in OE3, OE6, and OE7 lines were significantly higher than the WT seedlings. Thus, the OE3, OE6, and OE7 were selected for further studies.

Figure 9. CaChiVI2-overexpression effect on heat stress tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis lines. (A) CaChiVI2-overexpressed Arabidopsis lines (OE2, OE3, OE5, OE6, and OE7) and WT under heat stress. The different heat stress regimes as schematically shown on the top of petri-dish. (B) Comparison of CaChiVI2-overexpressed Arabidopsis lines (OE2, OE3, OE5, OE6, and OE7) and WT. Survival percentage of 8-day-old seedlings after exposing to 45°C heat stress for 2 h and then keeping at 22°C for 7 days. (C) The relative expression profile of CaChiVI2 under normal condition in CaChiVI2-overexpressed and WT plants. (D-I) Phenotypes, the transcript level of AtHSA32, MDA contents, SOD, POD activity and Proline accumulation measured in transgenic lines (OE3, OE6, and OE7) and WT plants after 40°C heat stress treatment for 16 h. Arabidopsis seedlings grown at 22°C were used as control. The bars indicated the mean values ± SDs for three replicates. The small letters (a–m) and asterisk (*) in corresponding graphs denote significant differences at P ≤ 0.05.

The seedlings were then grown in composite soil and treated with 40°C temperature for 16 h. As a result, the leaves of WT seedlings wilted severely, while mildly in case of CaChiVI2-OE seedlings. Ten days after heat treatment, the WT did not show progressive growth as compared to transgenic lines, as shown in Figure 9D. However, the defense-related gene (AtHSA32) was highly expressed in both WT and transgenic Arabidopsis. Additionally, the expression level of AtHSA32 in transgenic-lines (OE3, OE6, and OE7) was substantially higher than WT plants (see Figure 9E). Moreover, the accumulation of MDA contents in CaChiVI2-overexpressed lines was lower (Figure 9F), while SOD, POD activity and proline contents of CaChiVI2-OE seedlings were higher as compared to WT (Figures 9G–I).

The CaChiVI2 overexpressed transgenic lines were investigated for drought stress tolerance on MS-medium containing 0, 100, and 200 mM mannitol. There were no differences in the germination rates of WT plants and transgenic lines after 5 days. However, the root length of CaChiVI2-OE lines was substantially longer than the WT seedlings (Figures 10A,B). Besides, the WT and transgenic seedlings were grown in soil-media where water was withheld for 5 days. As a result, the WT seedlings dehydrated and displayed severe wilting. In comparison, slight damage was observed in transgenic seedlings and the rate of recovery was also faster than WT plants (Figure 10C). Nevertheless, the drought stress-related gene AtHSA32 was elicited in both transgenic and WT Arabidopsis, however its transcript level was greater in transgenic seedlings compared to wild-type plants (Figure 10D). Besides, the MDA content was substantially lower and proline significantly higher in CaChiVI2-OE seedlings as compared to WT (Figures 10E,F). Additionally, the accumulation of O2– was lower in transgenic seedlings (Figure 10G).

Figure 10. CaChiVI2-overexpression effect on drought stress tolerance of transgenic Arabidopsis. (A) Root growth (length) of CaChiVI2-overexpressed lines (OE3, OE6, and OE7) and WT Arabidopsis seedlings grown for 8-days on MS-medium containing 0, 100, and 200 mM mannitol. (B) Root length of the seedlings. (C–F) Phenotypes, the transcript level of AtHSA32, MDA contents, and proline accumulation of transgenic lines (OE3, OE6, and OE7) and WT plants under 5 days drought stress treatment (control plants were watered regularly). (G) Concentration of O2– (superoxide) in the leaves of transgenic lines (OE3, OE6, and OE7) and WT Arabidopsis plants after drought stress treatment (NBT staining technique was used for O2– detection). Bars in the respective histograms are mean values of three replicates and error bars are ± SDs. Asterisk (*) denotes significant differences at P ≤ 0.05.

The CBP is a stress-responsive multigene family, which regulates resistance against biotic and abiotic stresses (Xu et al., 2007; Ahmed et al., 2012; Su et al., 2015). The specificity of CBP-family regarding various stresses is confirmed in wheat crop (Singh et al., 2007). However, study on the characterization of pepper CBP genes, especially in relation to heat and drought stress is still not conclusive. Therefore, to fill the gap and disclose more CBP functions, CaChiVI2 gene from the Capsicum annuum L. genome database was chosen for further analysis. Likewise other CBP members, CaChiVI2 also had four heat shock elements (HSE’s) in their promoter region (Pastuglia et al., 1997; Ali et al., 2018). To confirm its function, the CaChiVI2 in pepper was successfully knockdown by VIGS, which correspondingly reduced resistance against heat stress and P. capsici infection (Figures 6A,D). Additionally, CaChiVI2 knockdown affect the expression of other stress responsive genes, i.e., CaDEF1 and CaHSP70-2 under heat stress and CaPR1 and CaDEF1 against P. capsici infection, which showed its role in defense mechanism of pepper plant. This statement is supported by Jin et al. (2016) through studying the function of CaPTI1 in pepper plant. The findings indicate that CaChiVI2 has a crucial role in enhancing pepper plants endurance against high temperature and P. capsici infection.

Reactive oxygen species signal components such as H2O2 and O2– play a significant role in plants responses to unfavorable environmental conditions. They perform multiple roles by acting directly in the initial defense. However, the over-accumulation of H2O2 and O2– under stress results in an active damage to the cell structures, photosynthesis and natural intracellular environment (Uzilday et al., 2012; Tuteja et al., 2014; Srivastava et al., 2016; Haq et al., 2019). Therefore, the contents of H2O2 and O2– are often used to find the damage levels of plant cells (Li et al., 2018). The detached leaves assay of CaChiVI2-silenced and control (TRV2:00) plants after the heat and P. capsici treatments were established to assess the ROS activities. As a result, more infection and ROS accumulation were found in the leaves of CaChiVI2-silenced versus control, which exhibited that knockdown of CaChiVI2 increased sensitivity and plants became more prone to stresses (Figures 8A,B). The outcome followed the similar pattern as explained in previous study by Zhang et al. (2018), and our conclusion are also consistent with Su et al. (2015). Contrarily, when CaChiVI2 overexpressed in Arabidopsis, low O2– accumulation was recorded in overexpressed plants as compared to WT under drought stress (Figure 10G). This indicates the role of CaChiVI2 in the defense system of a plant and also suggests that CaChiVI2 confers the plants ability to reduce the H2O2 and O2– concentrations thus evading the injuries caused by ROS under heat, drought and P. capsici infection.

Previously, overexpressed tobacco plants confirmed resistance to high temperature and oxidative stress exhibiting higher physiological indicators than WT plants (Zhang J. et al., 2016; Zang et al., 2018) and higher survival rate and root length was observed under high temperature and NaCl stress (Li J. et al., 2016). CaChiVI2 overexpression showed moderate heat and drought stress symptoms and increased the resistance of Arabidopsis plants (Figures 9D, 10C). The transcriptional activation/up-regulation of CaChiVI2 is necessary for immediate resistance against heat in CaChiVI2-OE lines (Figure 9C), signifying that CaChiVI2 not only responds to heat stress but also participates in drought stress. These facts confirm the earlier conclusions that CBP genes play an important role in environmental stresses (Hamid et al., 2013). Furthermore, resistance to high temperature and drought stress is also regulated by other genes in Arabidopsis, such as acquired thermo-tolerance related gene AtHSA32 is strongly activated by heat stress (Charng et al., 2006; Burke and Chen, 2015; Iurlaro et al., 2016). In our study, the transcript level of AtHSA32 gene was highly provoked by high temperature and drought stress in CaChiVI2-OE Arabidopsis as compared to WT plants (Figure 9E). It suggests that CaChiVI2 may possibly be involved in heat stress endurance by altering the transcript level of stress responsive genes. However, further study is needed to understand the exact mechanism.

Malondialdehyde (MDA) is an important product of membrane lipid peroxidation (LPO), which is considered as a reliable biochemical oxidative stress marker (Del Rio et al., 1996; Koźmińska et al., 2019). Based on our findings, it can be determined that the CaChiVI2-silenced plants exhibited an increase in MDA level, though the CaChiVI2-overexpressed Arabidopsis plants showed a decrease in MDA level (Figures 6G, 9F, 10E). The oxidative stress has shown correlation with MDA level (Gechev et al., 2002; Madhusudhan et al., 2009). It suggests that this might be due to the silencing effect of CaChiVI2 leading to damage in the plasma membrane. Whereas, the CaChiVI2 overexpressed Arabidopsis plants tolerate heat and the plasma membrane damages due to drought stress.

To mitigate the damages of ROS in unfavorable environmental conditions, plants develop special mechanisms to scavenge glut ROS through antioxidant enzymes such as SOD, POD, CAT, and APX and non-enzymatic antioxidants (Vitamin-C and proline content). These antioxidant enzymes and proline reduce oxidative damage caused by stress (Schöffl et al., 1999; Feng et al., 2019). During the scavenging of ROS, the SOD first decomposes O2– to H2O2 and then the H2O2 is scavenged by peroxidase (POD) in the cytosol and the outer cellular space (Gill and Tuteja, 2010; Uzilday et al., 2012). It is also investigated that the CBD having cysteine and the hinge region, which is saturated by proline and glycine. The biosynthesis of proline decreases the injury caused by ROS (Schöffl et al., 1999), while in many plant species proline has been considered one of the most common compatible osmolyte for cellular osmotic adjustment which are conferred by the high salinity, water deficit and other stresses (Szabados and Savoure, 2010; Al Hassan et al., 2017; Kumar et al., 2017). Likewise, in our study, the CaChiVI2-overexpressed Arabidopsis revealed significantly higher SOD, POD activities and proline contents than WT plants under heat stress (Figures 9G–I, 10F). Therefore, the previous findings of Sun et al. (2019), where transgenic Arabidopsis revealed better resistance to high temperature by accumulating more CAT, SOD and POD activity compared to wild-type plants, support our results. Interestingly in our study, the observation of CaChiVI2-OE lines showed higher proline biosynthesis relative to WT plants under heat and drought stress conditions (Figures 9I, 10F). Therefore, it can be concluded that the regulation of CaChiVI2 under CaMV35S promoter is clearly overexpressed and significantly influences the antioxidant enzymes machinery and also proline biosynthesis in response to heat and drought stress. In plants the electron transport chain regulated by mitochondrial second terminal oxidase (alternative oxidase-AOX) is also vital for the defensive machinery of a plant (Dong et al., 2009). Keeping in view this theory, we may conclude that the overexpression of CaChiVI2 upregulates the expression of AOX gene and thereby participates in the scavenging of ROS pathway and improves the overall defense system. Our findings clearly demonstrate that CaChiVI2 may tolerate high temperature and drought condition through the ROS-scavenging pathway. However, before declaring the potential role of CaChiVI2 as a novel stress-responsive gene, it is required to evaluate the exact mechanisms and regulation under heat signaling pathways.

The subcellular localization of CBP members may show their associated functions. Some CBP genes in other plants such as ScChiI1 have been localized in the cytoplasm and the plasma membrane (Su et al., 2015) and ChiIV3 in the plasma membrane (Liu Z. et al., 2017). In Oryza sativa, CBP proteins are located in cytoplasm and mitochondria and are thought to be associated with the thylakoid membrane under heat stress (Xu et al., 2007). The transient expression of CaChiVI2 in N. benthamiana leaves confirmed the localization of CaChiVI2 proteins only in the cytoplasm, indicating a vital role in the cytoplasm of a cell (Figure 3). Our key findings from testing the cloned CaChiVI2 gene are that heat stress and subsequently silencing by VIGS, caused severe damages to plant morphology and physiology. The ectopic expression of CaChiVI2 in Arabidopsis thaliana showed lethal damage due to heat and drought condition by increasing the transcript of resistance responsive genes. In the light of previous studies, we can conclude that CaChiVI2 may be acting as a transcriptional activator and provide an innate response to high temperature and drought condition.

Our results validated that CaChiVI2 knockdown decreased the stress tolerance ability of pepper plants against heat and P. capsici infection; additionally, the physiological and morphological attributes were also altered at certain level. The co-regulatory response of other defensive genes such as CaDEF1, CaPR1, and CaHSA70-2 not only confirmed the functional diversity of CaChiVI2 gene, but also introduce the important role in stress tolerance mechanism. In contrast, CaChiVI2-overexpressed plants showed mild symptoms, decreased heat and drought stress with the elevated transcript levels of the defense-related gene, including AtHSA32. The identified tasks of CaChiVI2 gene may provide some solid proofs for advance study of pepper plant adaptation mechanisms in response to sever environmental conditions.

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material.

The study presented in the manuscript did not involve any experimentation on human or animal subjects.

MHA and Z-HG conceived and designed the research. MKA conducted the experiments and wrote the manuscript. KA and IM analyzed the data. SH and AK performed the in silico analysis. AK, MHA, and HU critically revised the manuscript. Z-HG and GL contributed reagents and funded the project. All the authors read and approved the manuscript.

We highly appreciate the financial support of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. U1603102) and National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2016YFD0101900) for this study.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2020.00219/full#supplementary-material

Ahmed, N. U., Park, J. I., Seo, M. S., Kumar, T. S., Lee, I. H., Park, B. S., et al. (2012). Identification and expression analysis of chitinase genes related to biotic stress resistance in Brassica. Mol. Biol. Rep. 39, 3649–3657. doi: 10.1007/s11033-011-1139-x

Al Hassan, M., Estrelles, E., Soriano, P., López-Gresa, M. P., Bellés, J. M., Boscaiu, M., et al. (2017). Unraveling salt tolerance mechanisms in halophytes: a comparative study on four mediterranean Limonium species with different geographic distribution patterns. Front. Plant Sci. 8:1438. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01438

Ali, M., Luo, D.-X., Khan, A., Haq, S. U., Gai, W.-X., Zhang, H.-X., et al. (2018). Classification and genome-wide analysis of chitin-binding proteins gene family in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) and transcriptional regulation to Phytophthora capsici, abiotic stresses and hormonal applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19:2216. doi: 10.3390/ijms19082216

Ali, M., Xian, W., Abdul, G., Khattak, M., Khan, A., Ul, S., et al. (2019). Knockdown of the chitin-binding protein family gene CaChiIV1 increased sensitivity to Phytophthora capsici and drought stress in pepper plants. Mol. Genet. Genom. 294, 1311–1326. doi: 10.1007/s00438-019-01583-1587

Arkus, K. A. J., Cahoon, E. B., and Jez, J. M. (2005). Mechanistic analysis of wheat chlorophyllase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 438, 146–155. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2005.04.019

Baoling, L. (2018). Genome-wide characterization and expression analysis of GRAS gene family in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). PeerJ 6:e4796. doi: 10.7717/peerj.4796

Bates, L. S., Waldren, R. P., and Teare, I. D. (1973). Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant Soil 39, 205–207. doi: 10.1007/BF00018060

Bestwick, C. S., Brown, I. R., and Mansfield, J. W. (1998). Localized changes in peroxidase activity accompany hydrogen peroxide generation during the development of a nonhost hypersensitive reaction in lettuce. Plant Physiol. 118, 1067–1078. doi: 10.1104/pp.118.3.1067

Burke, J. J., and Chen, J. (2015). Enhancement of reproductive heat tolerance in plants. PLoS One 10:122933. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122933

Charng, Y., Liu, H., Liu, N., Hsu, F., and Ko, S. (2006). Arabidopsis Hsa32, a novel heat shock protein, is essential for acquired thermotolerance during long recovery after acclimation. Plant Physiol. 140, 1297–1305. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.074898.other

Clough, S. J., and Bent, A. F. (1998). Floral dip: a simplified method for agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 16, 735–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1998.00343.x

De Vos, C. H. R., Schat, H., De Waal, M. A. M., Vooijs, R., and Ernst, W. H. O. (1991). Increased resistance to copper-induced damage of the root cell plasmalemma in copper tolerant Silene cucubalus. Physiol. Plant. 82, 523–528. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1991.tb02942.x

Del Rio, L. A., Palma, J. M., Sandalio, L. M., Corpas, F. J., Pastori, G. M., Bueno, P., et al. (1996). Peroxisomes as a source of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide in stressed plants. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 24, 434–438. doi: 10.1042/bst0240434

Do, H. M., Lee, S. C., Jung, H. W., Sohn, K. H., and Hwang, B. K. (2004). Differential expression and in situ localization of a pepper defensin (CADEF1) gene in response to pathogen infection, abiotic elicitors and environmental stresses in Capsicum annuum. Plant Sci. 166, 1297–1305. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2004.01.008

Dong, D.-K., Song, F.-M., Liang, W.-S., Gu, M., Yu, J.-Q., Shi, K., et al. (2009). Systemic induction and role of mitochondrial alternative oxidase and nitric oxide in a compatible Tomato–Tobacco mosaic virus interaction. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 23, 39–48. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-23-1-0039

Erickson, A. N., and Markhart, A. H. (2002). Flower developmental stage and organ sensitivity of bell pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) to elevated temperature. Plant Cell Environ. 25, 123–130. doi: 10.1046/j.0016-8025.2001.00807.x

Feng, X., Zhang, H., Ali, M., Gai, W., Cheng, G., Yu, Q., et al. (2019). Plant Physiology and Biochemistry a small heat shock protein CaHsp25. 9 positively regulates heat, salt, and drought stress tolerance in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Plant Physiol. Biochem. 142, 151–162. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2019.07.001

Fukamizo, T., Sakai, C., and Tamoi, M. (2003). Plant chitinases: structure-function relationships and their physiology. Foods Food Ingred. J. Jpn 208, 631–632.

Gechev, T., Gadjev, I., Van Breusegem, F., Inzé, D., Dukiandjiev, S., Toneva, V., et al. (2002). Hydrogen peroxide protects tobacco from oxidative stress by inducing a set of antioxidant enzymes. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 59, 708–714. doi: 10.1007/s00018-002-8459-x

Gill, S. S., and Tuteja, N. (2010). Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant machinery in abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 48, 909–930. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2010.08.016

Guo, M., Liu, J. H., Ma, X., Zhai, Y. F., Gong, Z. H., and Lu, M. H. (2016). Genome-wide analysis of the Hsp70 family genes in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) and functional identification of CaHsp70-2 involvement in heat stress. Plant Sci. 252, 246–256. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2016.07.001

Guo, W.-L. L., Chen, R.-G. G., Du, X.-H. H., Zhang, Z., Yin, Y.-X. X., Gong, Z.-H. H., et al. (2014). Reduced tolerance to abiotic stress in transgenic arabidopsis overexpressing a Capsicum annuum multiprotein bridging factor 1. BMC Plant Biol. 14:138. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-14-138

Hamid, R., Khan, M. A., Ahmad, M., Ahmad, M. M., Abdin, M. Z., Musarrat, J., et al. (2013). Chitinases: an update. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 5:21. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.106559

Haq, S. U., Khan, A., Ali, M., Gai, W. X., Zhang, H. X., Yu, Q. H., et al. (2019). Knockdown of CaHSP60-6 confers enhanced sensitivity to heat stress in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Planta 250, 2127–2145. doi: 10.1007/s00425-019-03290-4

Hausbeck, M. K., and Lamour, K. H. (2004). Research progress and management challenges Phytophthora capsici on vegetable crops. Plant Dis. 88, 1292–1303. doi: 10.1094/PDIS.2004.88.12.1292

Hejgaard, J., Jacobsen, S., Bjorn, S. E., and Kragh, K. M. (1992). Antifungal activity of chitin-binding PR-4 type proteins from barley grain and stressed leaf. FEBS Lett. 307, 389–392. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80720-2

Iurlaro, A., De Caroli, M., Sabella, E., De Pascali, M., Rampino, P., De Bellis, L., et al. (2016). Drought and heat differentially affect XTH expression and XET activity and action in 3-day-old seedlings of durum wheat cultivars with different stress susceptibility. Front. Plant Sci. 7:1686. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01686

Jin, J., Zhang, H., Ali, M., Wei, A., Luo, D., and Gong, Z. (2019). The CaAP2/ERF064 regulates dual functions in pepper: plant cell death and resistance to Phytophthora capsici. Genes 10:541. doi: 10.3390/genes10070541

Jin, J.-H., Zhang, H.-X., Tan, J.-Y., Yan, M.-J., Li, D.-W., Khan, A., et al. (2016). A new ethylene-responsive factor CaPTI1 gene of pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) Involved in the regulation of defense response to Phytophthora capsici. Front. Plant Sci. 6:1217. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.01217

Khan, A., Li, R.-J., Sun, J.-T., Ma, F., Zhang, H.-X., Jin, J.-H., et al. (2018). Genome-wide analysis of dirigent gene family in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) and characterization of CaDIR7 in biotic and abiotic stresses. Sci. Rep. 8:5500. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-23761-0

Khurana, N., Chauhan, H., and Khurana, P. (2013). Wheat chloroplast targeted sHSP26 promoter confers heat and abiotic stress inducible expression in transgenic arabidopsis plants. PLoS One 8:54418. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054418

Kilasi, N. L., Singh, J., Vallejos, C. E., Ye, C., Jagadish, S. V. K., Kusolwa, P., et al. (2018). Heat stress tolerance in rice (Oryza sativa L.): identification of quantitative trait loci and candidate genes for seedling growth under heat stress. Front. Plant Sci. 9:1578. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01578

Kim, J. M., Woo, D. H., Kim, S. H., Lee, S. Y., Park, H. Y., Seok, H. Y., et al. (2012). Arabidopsis MKKK20 is involved in osmotic stress response via regulation of MPK6 activity. Plant Cell Rep. 31, 217–224. doi: 10.1007/s00299-011-1157-0

Koźmińska, A., Wiszniewska, A., Hanus-Fajerska, E., Boscaiu, M., Al Hassan, M., Halecki, W., et al. (2019). Identification of salt and drought biochemical stress markers in several Silene vulgaris populations. Sustain 11:800. doi: 10.3390/su11030800

Kumar, D., Al Hassan, M., Naranjo, M. A., Agrawal, V., Boscaiu, M., and Vicente, O. (2017). Effects of salinity and drought on growth, ionic relations, compatible solutes and activation of antioxidant systems in oleander (Nerium oleander L.). PLoS One 12:185017. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0185017

Lambert, W., Koeck, P. J. B., Ahrman, E., Purhonen, P., Cheng, K., Elmlund, D., et al. (2011). Subunit arrangement in the dodecameric chloroplast small heat shock protein Hsp21. Protein Sci. 20, 291–301. doi: 10.1002/pro.560

Lamour, K. H., Stam, R., Jupe, J., and Huitema, E. (2012). The oomycete broad-host-range pathogen Phytophthora capsici. Mol. Plant Pathol. 13, 329–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2011.00754.x

Lescot, M., Déhais, P., Thijs, G., Marchal, K., Moreau, Y., Van de Peer, Y., et al. (2002). PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 325–327. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.325

Letunic, I., and Bork, P. (2016). Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v3: an online tool for the display and annotation of phylogenetic and other trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W242–W245. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw290

Li, J., Zhang, J., Jia, H., Li, Y., Xu, X., Wang, L., et al. (2016). The Populus trichocarpa PtHSP17.8 involved in heat and salt stress tolerances. Plant Cell Rep. 35, 1587–1599. doi: 10.1007/s00299-016-1973-3

Li, Z., Long, R., Zhang, T., Yang, Q., and Kang, J. (2016). Molecular cloning and characterization of the MsHSP17.7 gene from Medicago sativa L. Mol. Biol. Rep. 43, 815–826. doi: 10.1007/s11033-016-4008-9

Li, M., Ji, L., Jia, Z., Yang, X., Meng, Q., and Guo, S. (2018). Constitutive expression of CaHSP22.5 enhances chilling tolerance in transgenic tobacco by promoting the activity of antioxidative enzymes. Funct. Plant Biol. 45, 575–585. doi: 10.1071/FP17226

Li, Q., Chen, J., Xiao, Y., Di, P., Zhang, L., and Chen, W. (2014). The dirigent multigene family in Isatis indigotica: gene discovery and differential transcript abundance. BMC Genomics 15:388. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-388

Li, Z., Baldwin, C. M., Hu, Q., Liu, H., and Luo, H. (2010). Heterologous expression of Arabidopsis H+-pyrophosphatase enhances salt tolerance in transgenic creeping bentgrass (Agrostis stolonifera L.). Plant Cell Environ. 33, 272–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.02080.x

Lim, C. W., Baek, W., Jung, J., Kim, J., and Lee, S. C. (2015). Function of ABA in stomatal defense against biotic and drought stresses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 16, 15251–15270. doi: 10.3390/ijms160715251

Liu, F., Yu, H., Deng, Y., Zheng, J., Liu, M., Ou, L., et al. (2017). PepperHub, an informatics hub for the chili pepper research community. Mol. Plant 10, 1129–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2017.03.005

Liu, H., Ouyang, B., Zhang, J., Wang, T., Li, H., Zhang, Y., et al. (2012). Differential modulation of photosynthesis, signaling, and transcriptional regulation between tolerant and sensitive tomato genotypes under cold stress. PLoS One 7:50785. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050785

Liu, Z., Shi, L., Yang, S., Lin, Y., Weng, Y., Li, X., et al. (2017). Functional and promoter analysis of ChiIV3, a Chitinase of pepper plant, in response to Phytophthora capsici infection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18:E1661. doi: 10.3390/ijms18081661

Liu, Z. Q., Liu, Y. Y., Shi, L. P., Yang, S., Shen, L., Yu, H. X., et al. (2016). SGT1 is required in PcINF1/SRC2-1 induced pepper defense response by interacting with SRC2-1. Sci. Rep. 6:21651. doi: 10.1038/srep21651

Ma, X., Gai, W. X., Qiao, Y. M., Ali, M., Wei, A. M., Luo, D. X., et al. (2019). Identification of CBL and CIPK gene families and functional characterization of CaCIPK1 under Phytophthora capsici in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). BMC Genomics 20:775. doi: 10.1186/s12864-019-6125-z

Madhusudhan, K. N., Srikanta, B. M., Shylaja, M. D., Prakash, H. S., and Shetty, H. S. (2009). Changes in antioxidant enzymes, hydrogen peroxide, salicylic acid and oxidative stress in compatible and incompatible host-tobamovirus interaction. J. Plant Interact. 4, 157–166. doi: 10.1080/17429140802419516

Muhammad, I., Jing, X. Q., Shalmani, A., Ali, M., Yi, S., Gan, P. F., et al. (2018). Comparative in silico analysis of ferric reduction oxidase (FRO) genes expression patterns in response to abiotic stresses, metal and hormone applications. Molecules 23, 1–22. doi: 10.3390/molecules23051163

Obata, T. S., Witt, S., Lisec, J., Palacios-Rojas, N., Florez-Sarasa, I., Yousfi, S., et al. (2015). Metabolite profiles of maize leaves in drought, heat and combined stress field trials reveal the relationship between metabolism and grain yield. Plant Physiol. 169, 2665–2683. doi: 10.1007/s10482-019-01235-1

Pagamas, P., and Nawata, E. (2008). Sensitive stages of fruit and seed development of chili pepper (Capsicum annuum L. var. Shishito) exposed to high-temperature stress. Sci. Hortic. 117, 21–25. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2008.03.017

Pastuglia, M., Roby, D., Dumas, C., and Cock, J. M. (1997). Rapid induction by wounding and bacterial infection of an S gene family receptor-like kinase gene in Brassica oleracea. Plant Cell 9, 49–60. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.1.49

Personat, J. M., Tejedor-Cano, J., Prieto-Dapena, P., Almoguera, C., and Jordano, J. (2014). Co-overexpression of two heat shock factors results in enhanced seed longevity and in synergistic effects on seedling tolerance to severe dehydration and oxidative stress. BMC Plant Biol. 14:56. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-14-56

Ramegowda, V., and Senthil-kumar, M. (2015). The interactive effects of simultaneous biotic and abiotic stresses on plants: mechanistic understanding from drought and pathogen combination. J. Plant Physiol. 176, 47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2014.11.008

Ranty, B., Aldon, D., Cotelle, V., Galaud, J., Thuleau, P., and Mazars, C. (2016). Calcium sensors as key hubs in plant responses to biotic and abiotic stresses. Front. Plant Sci. 7:327. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00327

Ruibal, C., Castro, A., Carballo, V., Szabados, L., and Vidal, S. (2013). Recovery from heat, salt and osmotic stress in physcomitrella patens requires a functional small heat shock protein PpHsp16.4. BMC Plant Biol. 13:174. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-13-174

Sah, S. K., Reddy, K. R., and Li, J. (2016). Abscisic acid and abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Front. Plant Sci. 7:571. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00571

Schmittgen, T. D., and Livak, K. J. (2008). Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative CT method. Nat. Protoc. 3, 1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73

Schöffl, F., Prandl, R., and Reindl, A. (1999). Molecular Responses to Cold, Drought, Heat and Salt Stress in Higher Plants. Austin, TX: R.G. Landes Company, 81–98.

Sewelam, N., Kazan, K., and Schenk, P. M. (2016). Global plant stress signaling: reactive oxygen species at the cross-road. Front. Plant Sci. 7:187. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00187

Shan, D. P., Huang, J. G., Yang, Y. T., Guo, Y. H., Wu, C. A., Yang, G. D., et al. (2007). Cotton GhDREB1 increases plant tolerance to low temperature and is negatively regulated by gibberellic acid. New Phytol. 176, 70–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02160.x

Singh, A., Isaac Kirubakaran, S., and Sakthivel, N. (2007). Heterologous expression of new antifungal chitinase from wheat. Protein Expr. Purif. 56, 100–109. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2007.06.013

Srivastava, V. K., Raikwar, S., Tuteja, R., and Tuteja, N. (2016). Ectopic expression of phloem motor protein pea forisome PsSEO-F1 enhances salinity stress tolerance in tobacco. Plant Cell Rep. 35, 1021–1041. doi: 10.1007/s00299-016-1935-9

Stewart, R. R. C., and Bewley, J. D. (1980). Lipid peroxidation associated with accelerated aging of soybean axes. Plant Physiol. 65, 245–248. doi: 10.1104/pp.65.2.245

Su, Y., Xu, L., Wang, S., Wang, Z., Yang, Y., Chen, Y., et al. (2015). Identification, phylogeny, and transcript of chitinase family genes in sugarcane. Sci. Rep. 5:10708. doi: 10.1038/srep10708

Sun, J.-T., Cheng, G.-X., Huang, L.-J., Liu, S., Ali, M., Khan, A., et al. (2019). Modified expression of a heat shock protein gene, CaHSP22.0, results in high sensitivity to heat and salt stress in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Sci. Hortic. 249, 364–373. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2019.02.008

Sy, O., Bosland, P. W., and Steiner, R. (2005). Inheritance of phytophthora stem blight resistance as compared to Phytophthora root rot and Phytophthora foliar blight resistance in Capsicum annuum L. J. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci. 130, 75–78. doi: 10.21273/jashs.130.1.75

Szabados, L., and Savoure, A. (2010). Proline: a multifunctional amino acid. Trends Plant Sci. 15, 89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2009.11.009

Thomma, B. P. H. J., Nürnberger, T., and Joosten, M. H. A. J. (2011). Of PAMPs and effectors: the blurred PTI-ETI dichotomy. Plant Cell 23, 4–15. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.082602

Thordal-Christensen, H., Zhang, Z., Wei, Y., and Collinge, D. B. (1997). Subcellular localization of H2O2 in plants. H2O2 accumulation in papillae and hypersensitive response during the barley-powdery mildew interaction. Plant J. 11, 1187–1194. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1997.11061187.x

Tsuda, K., and Katagiri, F. (2010). Comparing signaling mechanisms engaged in pattern-triggered and effector-triggered immunity. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 13, 459–465. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2010.04.006

Tuteja, N., Banu, M. S. A., Huda, K. M. K., Gill, S. S., Jain, P., Pham, X. H., et al. (2014). Pea p68, a DEAD-box helicase, provides salinity stress tolerance in transgenic tobacco by reducing oxidative stress and improving photosynthesis machinery. PLoS One 9:98287. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098287

Uzilday, B., Turkan, I., Sekmen, A. H., Ozgur, R., and Karakaya, H. C. (2012). Comparison of ROS formation and antioxidant enzymes in Cleome gynandra (C4) and Cleome spinosa (C3) under drought stress. Plant Sci. 182, 59–70. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2011.03.015

Wan, H., Yuan, W., Ruan, M., Ye, Q., Wang, R., Li, Z., et al. (2011). Identification of reference genes for reverse transcription quantitative real-time PCR normalization in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 416, 24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.10.105

Wang, H., Niu, H., Zhai, Y., and Lu, M. (2017). Characterization of BiP genes from pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) and the Role of CaBiP1 in response to endoplasmic reticulum and multiple abiotic stresses. Front. Plant Sci. 8:1122. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01122

Wang, J.-E., Li, D.-W., Gong, Z.-H., and Zhang, Y.-L. (2013a). Optimization of virus-induced gene silencing in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Genet. Mol. Res. 12, 2492–2506. doi: 10.4238/2013.july.24.4

Wang, J.-E., Li, D. W., Zhang, Y. L., Zhao, Q., He, Y. M., and Gong, Z. H. (2013b). Defence responses of pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) infected with incompatible and compatible strains of Phytophthora capsici. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 136, 625–638. doi: 10.1007/s10658-013-0193-8

Wang, J.-E., Liu, K. K., Li, D. W., Zhang, Y. L., Zhao, Q., He, Y. M., et al. (2013c). A novel peroxidase CanPOD gene of pepper is involved in defense responses to Phytophtora capsici infection as well as abiotic stress tolerance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14, 3158–3177. doi: 10.3390/ijms14023158

Xu, F., Fan, C., and He, Y. (2007). Chitinases in Oryza sativa ssp. japonica and Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Genet. Genomics 34, 138–150. doi: 10.1016/S1673-8527(07)60015-0

Yu, C., Zhan, Y., Feng, X., Huang, Z. A., and Sun, C. (2017). Identification and expression profiling of the auxin response factors in Capsicum annuum L. Under abiotic stress and hormone treatments. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18:719. doi: 10.3390/ijms18122719

Zang, X., Geng, X., He, K., Wang, F., Tian, X., Xin, M., et al. (2018). Overexpression of the Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) TaPEPKR2 gene enhances heat and dehydration tolerance in both wheat and arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 9:1710. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01710

Zhai, Y., Guo, M., Wang, H., Lu, J., Liu, J., Zhang, C., et al. (2016). Autophagy, a conserved mechanism for protein degradation, responds to heat, and other abiotic stresses in Capsicum annuum L. Front. Plant Sci. 7:131. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00131

Zhai, Y., Wang, H., Liang, M., and Lu, M. (2017). Both silencing- and over-expression of pepper CaATG8c gene compromise plant tolerance to heat and salt stress. Environ. Exp. Bot. 141, 10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2017.06.009

Zhang, H., Ali, M., Feng, X., Jin, J., Huang, L., Khan, A., et al. (2018). A novel transcription factor CaSBP12 gene negatively regulates the defense response against Phytophthora capsici in pepper (Capsicum annuum L .). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20:E48. doi: 10.3390/ijms20010048

Zhang, H.-X., Jin, J.-H., He, Y.-M., Lu, B.-Y., Li, D.-W., Chai, W.-G., et al. (2016). Genome-wide identification and analysis of the SBP-box family genes under Phytophthora capsici stress in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Front. Plant Sci. 7:504. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00504

Zhang, J., Chen, H., Wang, H., Li, B., Yi, Y., Kong, F., et al. (2016). Constitutive expression of a tomato small heat shock protein gene LeHSP21 improves tolerance to high-temperature stress by enhancing antioxidation capacity in tobacco. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 34, 399–409. doi: 10.1007/s11105-015-0925-3

Keywords: Arabidopsis, CaChiVI2, chitin-binding protein, drought, heat, pepper, resistance

Citation: Ali M, Muhammad I, ul Haq S, Alam M, Khattak AM, Akhtar K, Ullah H, Khan A, Lu G and Gong Z-H (2020) The CaChiVI2 Gene of Capsicum annuum L. Confers Resistance Against Heat Stress and Infection of Phytophthora capsici. Front. Plant Sci. 11:219. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.00219

Received: 27 November 2019; Accepted: 12 February 2020;

Published: 26 February 2020.

Edited by:

Oscar Vicente, Universitat Politècnica de València, SpainReviewed by:

Manuel Martinez-Estevez, Unidad de Bioquímica y Biología Molecular de Plantas, Centro de Investigación Científica de Yucatán, MexicoCopyright © 2020 Ali, Muhammad, ul Haq, Alam, Khattak, Akhtar, Ullah, Khan, Lu and Gong. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gang Lu, Z2x1QHpqdS5lZHUuY24=; Zhen-Hui Gong, emhnb25nQG53c3VhZi5lZHUuY24=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.