94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

MINI REVIEW article

Front. Plant Sci. , 18 June 2019

Sec. Plant Physiology

Volume 10 - 2019 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2019.00790

This article is part of the Research Topic Ethylene Biology and Beyond: Novel Insights in the Ethylene Pathway and its Interactions View all 16 articles

Likai Wang1,2

Likai Wang1,2 Hong Qiao1,2*

Hong Qiao1,2*As any living organisms, plants must respond to a wide variety of environmental stimuli. Plant hormones regulate almost all aspects of plant growth and development. Among all the plant hormones, ethylene is the only gaseous plant hormone that plays pleiotropic roles in plant growth, plant development and stress responses. Transcription regulation is one main mechanism by which a cell orchestrates gene activity. This control allows the cell or organism to respond to a variety of intra- and extracellular signals and thus mount a response. Here we review the progress of transcription regulation in the ethylene response.

Like all living organisms, plants must respond to a wide variety of environmental stimuli. Plant hormones, produced in response to environmental stimuli, regulate almost all aspects of plant growth and development. Ethylene is a gaseous plant hormone that plays pleiotropic roles in plant growth, plant development, and stress responses. Histone acetylation, which is modulated through ethylene-mediated signaling, regulates dynamic changes in chromatin structure that result in transcriptional regulation in responses to ethylene.

Ethylene is perceived by a family of receptors bound to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane (Chang et al., 1993; Bleecker et al., 1998; Hua and Meyerowitz, 1998; Hua et al., 1998; Sakai et al., 1998). Each receptor binds ethylene via a copper cofactor that is provided by the copper transporter RESPONSIVE-TO-ANTAGONIST 1 (RAN1)(Hirayama et al., 1999). In the absence of ethylene, ethylene receptor ETHYLENE RECEPTOR 1 (ETR1) interacts with CONSTITUTIVE TRIPLE RESPONSE 1 (CTR1), a downstream negative regulator of ethylene signaling (Chang et al., 1993; Kieber et al., 1993; Gao et al., 2003; Shakeel et al., 2015). CTR1 is a protein kinase that phosphorylates ETHYLENE INSENSITIVE 2 (EIN2), a key positive regulator of ethylene signaling (Alonso et al., 1999; Ju et al., 2012), preventing the ethylene response. In addition, in the absence of ethylene, EIN2 protein levels are regulated by EIN2 TARGETING PROTEIN 1 and 2 (ETP1/2) via ubiquitin/proteasome-mediated degradation (Qiao et al., 2009).

In the presence of ethylene both ethylene receptors and CTR1 are inactivated, and the C-terminal end of EIN2 is dephosphorylated and cleaved by unknown mechanisms. The cleaved C-terminal end of EIN2 translocates to the nucleus (Qiao et al., 2012; Wen et al., 2012; Ju et al., 2015) where it facilitates the acetylation of histone 3 at K14 and K23 (H3K14 and H3K23, respectively) to regulate ETHYLENE INSENSITIVE 3 (EIN3) and ETHYLENE INSENSITIVE 3 LIKE1 (EIL1) – dependent transcriptional regulation (Zhang et al., 2016). The cleaved EIN2 C-terminal end also translocates into the P-body through associating with 3′UTRs of EIN3 BINDING F-BOX1 (EBF1) and EBF2, further repressing their translation (Guo and Ecker, 2003). EBF1 and EBF2 in turn stabilize EIN3 and EIL1, resulting in activation of EIN3- and EIL1-dependent transcription and the activation of an ethylene response (Li et al., 2015; Merchante et al., 2015).

Both genetic and molecular studies have demonstrated that EIN3 and EIL1 are positive regulators that are necessary and sufficient for the ethylene response (Chao et al., 1997; Guo and Ecker, 2003; Chang et al., 2013). The EIN3 gene encodes a nuclear-localized protein that is essential to the response to ethylene (Chao et al., 1997). In the absence of EIN3, plants are partially insensitive to ethylene both at the morphological and molecular levels (Chao et al., 1997; Guo and Ecker, 2003). The EIN3 binding motif was identified after analysis of the promoters of the genes that are highly up-regulated by ethylene and followed by validation using an electrophoresis mobility shift assay (EMSA) (Ohme-Takagi and Shinshi, 1990; Eyal et al., 1993; Meller et al., 1993; Sessa et al., 1995; Shinshi et al., 1995; Sato et al., 1996; Solano et al., 1998). Using the EMSA assay, EIN3 was shown to form a homodimer in the presence of DNA in vitro (Solano et al., 1998). However, whether the homodimer is formed in vivo and whether the homodimer is required for EIN3 to function in the ethylene signaling are unknown. A number of transcription factors are known to form homodimers or heterodimers, which have different specificities and affinities for certain DNA motifs (Funnell and Crossley, 2012). Finding out whether the dimerization is necessary for EIN3′s function in vivo will be an interesting question in the transcriptional regulation of the ethylene response.

To explore the transcription regulation in response to ethylene, Chang et al characterized the dynamic ethylene transcriptional response by identifying targets of EIN3, the master regulator of the ethylene signaling pathway, using chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing and transcript sequencing during a time course of ethylene treatment (Chang et al., 2013). They found that the number of genes bound by EIN3 does not change significantly in response to ethylene. The amount of EIN3 bound increases upon ethylene treatment, and the expression of most of EIN3-bound genes is up regulated by ethylene, which is consistent with a role of EIN3 as a transcriptional activator. Chang et al. also analyzed the sequences of EIN3-bound regions identified by ChIP-seq (Ohme-Takagi and Shinshi, 1990; Eyal et al., 1993; Meller et al., 1993; Sessa et al., 1995; Shinshi et al., 1995; Sato et al., 1996; Solano et al., 1998). A motif similar to that previously identified in the promoter regions of ethylene up-regulated genes was present in EIN3-bound regions (Ohme-Takagi and Shinshi, 1990; Eyal et al., 1993; Meller et al., 1993; Sessa et al., 1995; Shinshi et al., 1995; Sato et al., 1996; Solano et al., 1998). Intriguingly, Chang et al. also found that ethylene-induced transcription occurs in temporal waves that were regulated by EIN3 with the potentially distinct layers of transcriptional control (Chang et al., 2013). EIN3 binding was found to modulate a multitude of downstream transcriptional cascades, including a major feedback regulatory circuitry of the ethylene signaling pathway, as well as most of the hormone-mediated growth response pathways, which indicates that network-level feedback regulation results in overall system control and homeostasis (Chang et al., 2013). This type of study can be applied to identify novel components in signaling pathways (Rosenfeld et al., 2002; Amit et al., 2007; Tsang et al., 2007; Avraham and Yarden, 2011; Feng et al., 2011; Yosef and Regev, 2011).

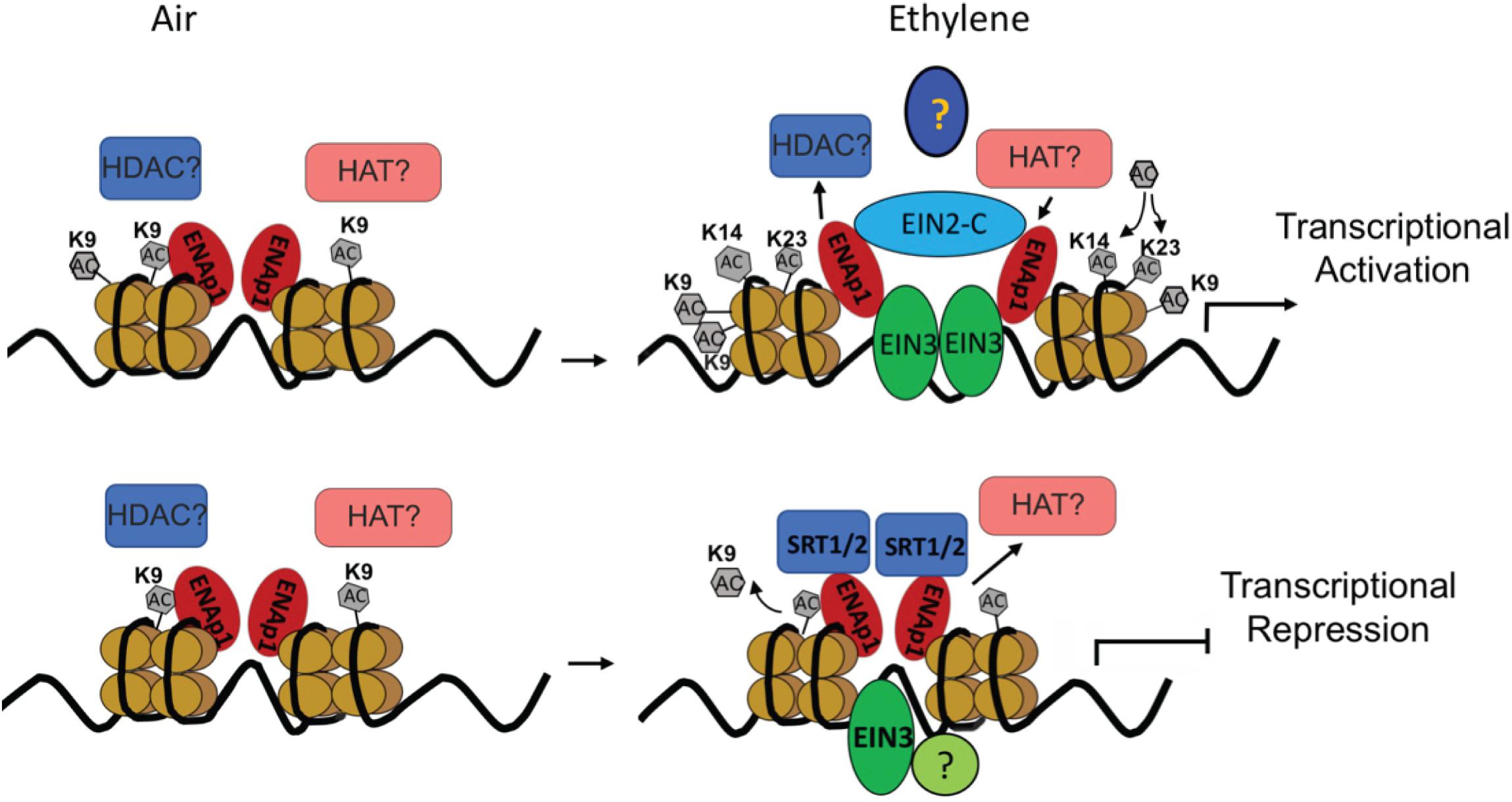

Although the transcriptional activation has been the main focus in the ethylene response, transcriptome analysis in Chang’s study clearly showed that nearly 50% of ethylene-altered genes are down regulated and that a subset of ethylene-repressed genes are bound by EIN3 (Chang et al., 2013). Notably, most of the genes are down regulated by ethylene within 1 h of treatment. This result strongly suggests that transcriptional repression plays a critical role in early ethylene response. Interestingly, a recent study from the Qiao lab showed that transcriptional repression dose plays important roles in ethylene response. We identified two histone deacetylases (HDACs) SIRTUIN 1 and 2 (SRT1 and SRT2) that regulate ethylene-repressed genes (Zhang et al., 2018). Notably the study found that SRT2 binds the target promoter regions to inhibit acetylation of histone 3 at K9 (H3K9Ac), repressing gene expression in response to ethylene (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Diagram to illustrate the transcription regulation in ethylene response. Upper panel: in the absence of ethylene, no ethylene regulated transcription regulation; In the presence of ethylene, accumulated EIN3 interacts with ENAP1 and EIN2 c-terminus, which elevates histone acetylation of H3K14Ac and H3K23Ac through an interaction with unidentified histone acetyltransferases to activate EIN3 dependent transcriptional activation. Lower panel: In the absence of ethylene, ethylene down-regulated genes are transcribed; In the presence of ethylene, histone deacetylase SRT1 and SRT2 are recruited to target genes to keep a low level of H3K9Ac, resulting in the targets for transcriptional repression.

Transcriptional repression by chromatin modification is one of the principal mechanisms employed by eukaryotic active repressors (Thiel et al., 2004; Kagale and Rozwadowski, 2011). The importance of HDACs in transcriptional repression during plant growth and development has been well established (Song et al., 2005; Li et al., 2017). For example, in Arabidopsis, the EAR motif containing class II ETHYLENE RESPONSIVE ELEMENT BINDING FACTORS (ERFs), such as ERF3 and ERF4, which are known to function as active repressors in vitro and in vivo, have been shown to physically interact with AtSAP18, which in turn interacts and forms a repression complex with AtHDA19 (Fujimoto et al., 2000; Ohta et al., 2001; McGrath et al., 2005; Song and Galbraith, 2006). AtERF7, another EAR motif-containing class II ERF protein, is also known to recruit AtHDA19 via a physical interaction with AtSIN3 (Song et al., 2005). In planta, coexpression of AtERF3, AtSAP18, and AtHDA19 or AtERF7, AtSIN3, and AtHDA19 results in greater transcriptional repression of reporter genes as compared to when these proteins are expressed alone suggesting a role for AtSAP18, AtSIN3, and AtHDA19 in ERF-mediated transcriptional repression possibly via histone deacetylation (Song et al., 2005; Song and Galbraith, 2006). Yet, whether EAR containing proteins are also required for SRT1 and SRT2 mediated transcriptional repression in response to ethylene is unknown (Zhang et al., 2018). It also remains unclear whether the ethylene response has a molecular mechanism of transcriptional repression similar to that induced by other plant hormones. Exploring the molecular mechanism of transcriptional repression will provide more insight into ethylene signaling and ethylene response.

In eukaryotes, the binding of transcription factors is mainly determined by chromatin structure, namely the state of the genome’s packaging with specific structural proteins, mainly histones. Chromatin undergoes different dynamics structure changes, further influences transcription factor binding. Among all the regulations, histone acetylation results in a switch between repressive and permissive chromatin. In general, acetylation neutralizes the positive charges of lysine residues and decreases the interaction between histone and DNA, leading to a more relaxed chromatin structure, which is associated with transcriptional activation. In contrast, deacetylation induces a compact chromatin structure, which is associated with transcriptional repression (Fletcher and Hansen, 1996; Steger and Workman, 1996; Luger and Richmond, 1998).

A Number of studies have shown a tight link between histone acetylation and plant hormone responses (Zhu, 2010). In the studies of ethylene signaling, authors found that GENERAL CONTROL NON-REPRESSED PROTEIN 5 (GCN5), which belongs to a family of histone acetyl transferases (HATs), promotes transcriptional activation (Brownell and Allis, 1996; Grant et al., 1997; Bian et al., 2011; Weake and Workman, 2012; Ryu et al., 2014). The Arabidopsis gcn5 mutant shows hypersensitivity to ethylene treatment. In the gcn5 mutant, the histone acetylation at H3K9 and H3K14 in the promoter regions of ethylene response genes is elevated, and the elevation is associated with the up-regulation of gene expression (Poulios and Vlachonasios, 2016). In Arabidopsis, the HAC family, which are the homologs of CREB-binding protein (CBP) and p300, the mammalian family of HAT domain containing transcriptional coactivators, play pleotropic roles in plant growth and development (Pandey et al., 2002; Li et al., 2014). The hac1hac5 double mutant was found to have a constitutive triple response phenotype (Pandey et al., 2002; Li et al., 2014). It was expected that gene expression would be down regulated in the hac1hac5 double mutant due to the reduction of histone acetylation levels; however, similar to that in gcn5 mutant, the downstream ethylene responsive genes are elevated in hac1hac5 double mutant (Li et al., 2014), suggesting an indirect regulation of ethylene responsive genes by HAC1 and HAC5.

Expression of two HDACs, HAD6 and HDA19, are specifically elevated by ethylene treatment. The expression of ethylene responsive gene ERF1 is anti-correlated with the levels of histone H3 acetylation in 35S:HDA19 transgenic plants, showing that HDA19 indirectly influences ERF1 gene expression (Zhou et al., 2005). It is possible that HDA19 induces ERF1 expression by preventing binding of an unknown transcription repressor that regulates ERF1 expression (Zhou et al., 2005). JAZ proteins recruit HDA6 to deacetylate histones and obstruct the chromatin binding of EIN3/EIL1, therefore repressing EIN3/EIL1-dependent transcription and inhibiting jasmonic acid-mediated signaling (Zhu et al., 2011). This provides evidence that histone acetylation regulates EIN3 target genes.

H3K14Ac and H3K23Ac, but not H3K9Ac, H3K18Ac, or H3K27Ac, are elevated by ethylene treatment at the molecular level (Zhang et al., 2016; Yoon et al., 2017). Interestingly, even though the levels of H3K9Ac are not regulated by ethylene, the levels of H3K9Ac in the promoters of ethylene up-regulated genes are higher than that in those ethylene down-regulated genes both with and without ethylene treatments (Zhang et al., 2016; Yoon et al., 2017). Presumably, H3K9Ac is a pre-existing mark that labels genes regulated by ethylene, whereas the elevation of H3K14Ac and H3K23Ac is positively associated with gene activation. Most importantly, the ethylene-induced change of histone acetylation is EIN2 dependent. However, EIN2 is not a histone or a DNA binding protein, and the biochemical function of EIN2-C remains unknown. Yeast two-hybrid screening and ChIP-re-ChIP suggests that EIN2-C is associated with histones at least in part through EIN2 NUCLEAR ASSOCIATED PROTEIN 1 (ENAP1), which has histone binding activity (Figure 1; Zhang et al., 2017). It is possible that EIN2-C is a scaffolding protein that is important for the formation of HAT-containing protein complexes in response to ethylene. Identification of HAT or HDAC that functions in cooperation with EIN2-C would validate this assumption. In contrast to transcriptional activation, histone acetylation of H3K9Ac was found to be involved in the transcriptional repression, and the regulation is partially mediated by histone deacetylase SRT1 and SRT2 (Figure 1).

Taken together, currently available data suggest that in the absence of ethylene ENAP1 binds to histones to keep chromatin in a relaxed state poised for a rapid response to ethylene (Figure 1). In the presence of ethylene, EIN2-C is translocated to the nucleus where it interacts with ENAP1 and potentially HATs resulting in histone acetylation. This causes an uncompacting of chromatin, resulting in more EIN3 binding to target genes and ultimately transcription activation (Figure 1). It is not known how the histone acetylation targets are determined in the presence of ethylene. Zhang et al. showed that EIN3 is partially required for the ethylene-induced elevation of H3K14Ac and H3K23Ac (Pandey et al., 2002), suggesting that EIN3 might mark histone acetylation targets. Multi-protein assemblies have been shown to determine the substrate specificities and targeting of integral HAT subunits. The molecular mechanism of how EIN3, ENAP1, and EIN2-C coordinate to integrate the histone acetylation and transcription regulation remains to be elucidated. Beside histone acetylation regulation in transcriptional activation, histone acetylation has been shown to be involved in transcriptional repression in ethylene response. As mentioned above, SRT1 and SRT2 mediate transcriptional repression that requires a low level of H3K9Ac (Yosef and Regev, 2011). How the H3K9Ac levels are determined in the desired targets in the first place is an interesting and important question that needs to be addressed.

Plants must respond accurately and quickly to hormones, and this necessitates a flexible and rapid way to control gene expression. The acetylation of histone tails by HATs neutralizes positive charges on these proteins that would otherwise interact with negatively charged DNA, facilitating nucleosome unwrapping for rapid transcription activation. How plants utilize a limited number of HATs and HDACs to specifically regulate responses to different hormones is largely unknown. Presumably, the specificity relies on the partners of HATs and HDACs. Identification of the HAT- and HDAC-containing complexes upon ethylene treatment will reveal details of the molecular mechanisms that underlie the ethylene response. Recent studies have clearly shown that different tissues respond to plant hormones differently (Garg et al., 2012; Pattison et al., 2015; Raines et al., 2016). Most available data on histone acetylation induced by plant hormones come from analyses of the whole plant. Studies of histone acetylation in individual tissues and in different cell types will provide more detailed insight into how histone acetylation controls responses to plant hormones. Transcription factor binding in eukaryotes is highly dependent on the context of binding sites on chromatin, but little is known about how EIN3 determines histone acetylation sites in target genes. A more complete understanding of the molecular mechanism of determination of transcriptional activation and transcriptional repression during the ethylene response will facilitate development of methods to improve crop production.

Both authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R01GM115879-01) to HQ.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We thank the members of the Qiao laboratory for critical reading of this manuscript.

Alonso, J. M., Hirayama, T., Roman, G., Nourizadeh, S., and Ecker, J. R. (1999). EIN2, a bifunctional transducer of ethylene and stress responses in Arabidopsis. Science 284, 2148–2152. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5423.2148

Amit, I., Citri, A., Shay, T., Lu, Y., Katz, M., Zhang, F., et al. (2007). A module of negative feedback regulators defines growth factor signaling. Nat. Genet. 39, 503–512. doi: 10.1038/ng1987

Avraham, R., and Yarden, Y. (2011). Feedback regulation of EGFR signalling: decision making by early and delayed loops. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 12, 104–117. doi: 10.1038/nrm3048

Bian, C., Xu, C., Ruan, J., Lee, K. K., Burke, T. L., Tempel, W., et al. (2011). Sgf29 binds histone H3K4me2/3 and is required for SAGA complex recruitment and histone H3 acetylation. EMBO J. 30, 2829–2842. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.193

Bleecker, A. B., Esch, J. J., Hall, A. E., Rodriguez, F. I., and Binder, B. M. (1998). The ethylene-receptor family from Arabidopsis: structure and function. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 353, 1405–1412. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1998.0295

Brownell, J. E., and Allis, C. D. (1996). Special HATs for special occasions: linking histone acetylation to chromatin assembly and gene activation. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 6, 176–184. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(96)80048-7

Chang, C., Kwok, S. F., Bleecker, A. B., and Meyerowitz, E. M. (1993). Arabidopsis ethylene-response gene ETR1: similarity of product to two-component regulators. Science 262, 539–544. doi: 10.1126/science.8211181

Chang, K. N., Zhong, S., Weirauch, M. T., Hon, G., Pelizzola, M., Li, H., et al. (2013). Temporal transcriptional response to ethylene gas drives growth hormone cross-regulation in Arabidopsis. eLife 2:e00675. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00675

Chao, Q. M., Rothenberg, M., Solano, R., Roman, G., Terzaghi, W., Ecker, J. R., et al. (1997). Activation of the ethylene gas response pathway in Arabidopsis by the nuclear protein ETHYLENE-INSENSITIVE3 and related proteins. Cell 89, 1133–1144. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80300-1

Eyal, Y., Meller, Y., Lev-Yadun, S., and Fluhr, R. (1993). A basic-type PR-1 promoter directs ethylene responsiveness, vascular and abscission zone-specific expression. Plant J. 4, 225–234. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1993.04020225.x

Feng, Z., Lin, M., and Wu, R. (2011). The regulation of aging and longevity: a new and complex role of p53. Genes Cancer 2, 443–452. doi: 10.1177/1947601911410223

Fletcher, T. M., and Hansen, J. C. (1996). The nucleosomal array: structure/function relationships. Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr. 6, 149–188. doi: 10.1615/critreveukargeneexpr.v6.i2-3.40

Fujimoto, S. Y., Ohta, M., Usui, A., Shinshi, H., and Ohme-Takagi, M. (2000). Arabidopsis ethylene-responsive element binding factors act as transcriptional activators or repressors of GCC box-mediated gene expression. Plant Cell 12, 393–404. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.3.393

Funnell, A. P., and Crossley, M. (2012). Homo- and heterodimerization in transcriptional regulation. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 747, 105–121. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-3229-6_7

Gao, Z., Chen, Y. F., Randlett, M. D., Zhao, X. C., Findell, J. L., Kieber, J. J., et al. (2003). Localization of the Raf-like kinase CTR1 to the endoplasmic reticulum of Arabidopsis through participation in ethylene receptor signaling complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 34725–34732. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305548200

Garg, R., Tyagi, A. K., and Jain, M. (2012). Microarray analysis reveals overlapping and specific transcriptional responses to different plant hormones in rice. Plant Signal. Behav. 7, 951–956. doi: 10.4161/psb.20910

Grant, P. A., Duggan, L., Côté, J., Roberts, S. M., Brownell, J. E., Candau, R., et al. (1997). Yeast Gcn5 functions in two multisubunit complexes to acetylate nucleosomal histones: characterization of an Ada complex and the SAGA (Spt/Ada) complex. Genes Dev. 11, 1640–1650. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.13.1640

Guo, H. W., and Ecker, J. R. (2003). Plant responses to ethylene gas are mediated by SCF (EBF1/EBF2)-dependent proteolysis of EIN3 transcription factor. Cell 115, 667–677. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00969-3

Hirayama, T., Kieber, J. J., Hirayama, N., Kogan, M., Guzman, P., Nourizadeh, S., et al. (1999). RESPONSIVE-TO-ANTAGONIST1, a Menkes/Wilson disease-related copper transporter, is required for ethylene signaling in Arabidopsis. Cell 97, 383–393. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80747-3

Hua, J., and Meyerowitz, E. M. (1998). Ethylene responses are negatively regulated by a receptor gene family in Arabidopsis thaliana. Cell 94, 261–271. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81425-7

Hua, J., Sakai, H., Nourizadeh, S., Chen, Q. G., Bleecker, A. B., Ecker, J. R., et al. (1998). EIN4 and ERS2 are members of the putative ethylene receptor gene family in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 10, 1321–1332. doi: 10.1105/tpc.10.8.1321

Ju, C., Van de Poel, B., Cooper, E. D., Thierer, J. H., Gibbons, T. R., Delwiche, C. F., et al. (2015). Conservation of ethylene as a plant hormone over 450 million years of evolution. Nat. Plants 1:14004. doi: 10.1038/nplants.2014.4

Ju, C. L., Yoon, G. M., Shemansky, J. M., Lin, D. Y., Ying, Z. I., Chang, J., et al. (2012). CTR1 phosphorylates the central regulator EIN2 to control ethylene hormone signaling from the ER membrane to the nucleus in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 19486–19491. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1214848109

Kagale, S., and Rozwadowski, K. (2011). EAR motif-mediated transcriptional repression in plants: an underlying mechanism for epigenetic regulation of gene expression. Epigenetics 6, 141–146. doi: 10.4161/epi.6.2.13627

Kieber, J. J., Rothenberg, M., Roman, G., Feldmann, K. A., and Ecker, J. R. (1993). Ctr1, a negative regulator of the ethylene response pathway in arabidopsis, encodes a member of the Raf family of protein-kinases. Cell 72, 427–441. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90119-b

Li, C., Xu, J., Li, J., Li, Q., and Yang, H. (2014). Involvement of Arabidopsis HAC family genes in pleiotropic developmental processes. Plant Signal. Behav. 9:e28173. doi: 10.4161/psb.28173

Li, W., Lacey, R. F., Ye, Y., Lu, J., Yeh, K. C., Xiao, Y., et al. (2017). Triplin, a small molecule, reveals copper ion transport in ethylene signaling from ATX1 to RAN1. PLoS Genet. 13:e1006703. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006703

Li, W. Y., Ma, M., Feng, Y., Li, H., Wang, Y., Ma, Y., et al. (2015). EIN2-directed translational regulation of ethylene signaling in arabidopsis. Cell 163, 670–683. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.037

Luger, K., and Richmond, T. J. (1998). The histone tails of the nucleosome. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 8, 140–146.

McGrath, K., Dombrecht, B., Manners, J. M., Schenk, P. M., Edgar, C. I., Maclean, D. J. C., et al. (2005). Repressor- and activator-type ethylene response factors functioning in jasmonate signaling and disease resistance identified via a genome-wide screen of Arabidopsis transcription factor gene expression. Plant Physiol. 139, 949–959. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.068544

Meller, Y., Sessa, G., Eyal, Y., and Fluhr, R. (1993). DNA-protein interactions on a cis-DNA element essential for ethylene regulation. Plant Mol. Biol. 23, 453–463. doi: 10.1007/bf00019294

Merchante, C., Brumos, J., Yun, J., Hu, Q., Spencer, K. R., Enríquez, P., et al. (2015). Gene-specific translation regulation mediated by the hormone-signaling molecule EIN2. Cell 163, 684–697. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.036

Ohme-Takagi, M., and Shinshi, H. (1990). Structure and expression of a tobacco beta-1,3-glucanase gene. Plant Mol. Biol. 15, 941–946. doi: 10.1007/bf00039434

Ohta, M., Matsui, K., Hiratsu, K., Shinshi, H., and Ohme-Takagi, M. (2001). Repression domains of class II ERF transcriptional repressors share an essential motif for active repression. Plant Cell 13, 1959–1968. doi: 10.1105/tpc.13.8.1959

Pandey, R., Müller, A., Napoli, C. A., Selinger, D. A., Pikaard, C. S., Richards, E. J., et al. (2002). Analysis of histone acetyltransferase and histone deacetylase families of Arabidopsis thaliana suggests functional diversification of chromatin modification among multicellular eukaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 5036–5055. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf660

Pattison, R. J., Csukasi, F., Zheng, Y., Fei, Z., van der Knaap, E., Catalá, C., et al. (2015). Comprehensive tissue-specific transcriptome analysis reveals distinct regulatory programs during early tomato fruit development. Plant Physiol. 168, 1684–1701. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.00287

Poulios, S., and Vlachonasios, K. E. (2016). Synergistic action of histone acetyltransferase GCN5 and receptor CLAVATA1 negatively affects ethylene responses in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Bot. 67, 905–918. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erv503

Qiao, H., Chang, K. N., Yazaki, J., and Ecker, J. R. (2009). Interplay between ethylene, ETP1/ETP2 F-box proteins, and degradation of EIN2 triggers ethylene responses in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 23, 512–521. doi: 10.1101/gad.1765709

Qiao, H., Shen, Z., Huang, S. S., Schmitz, R. J., Urich, M. A., Briggs, S. P., et al. (2012). Processing and subcellular trafficking of ER-Tethered EIN2 control response to ethylene gas. Science 338, 390–393. doi: 10.1126/science.1225974

Raines, T., Blakley, I. C., Tsai, Y. C., Worthen, J. M., Franco-Zorrilla, J. M., Solano, R., et al. (2016). Characterization of the cytokinin-responsive transcriptome in rice. BMC Plant Biol. 16:260. doi: 10.1186/s12870-016-0932-z

Rosenfeld, N., Elowitz, M. B., and Alon, U. (2002). Negative autoregulation speeds the response times of transcription networks. J. Mol. Biol. 323, 785–793. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00994-4

Ryu, H., Cho, H., Bae, W., and Hwang, I. (2014). Control of early seedling development by BES1/TPL/HDA19-mediated epigenetic regulation of ABI3. Nat. Commun. 5:4138. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5138

Sakai, H., Hua, J., Chen, Q. G., Chang, C., Medrano, L. J., Bleecker, A. B., et al. (1998). ETR2 is an ETR1-like gene involved in ethylene signaling in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 5812–5817. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.10.5812

Sato, F., Kitajima, S., Koyama, T., and Yamada, Y. (1996). Ethylene-induced gene expression of osmotin-like protein, a neutral isoform of tobacco PR-5, is mediated by the AGCCGCC cis-sequence. Plant Cell Physiol. 37, 249–255. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a028939

Sessa, G., Meller, Y., and Fluhr, R. (1995). A GCC element and a G-box motif participate in ethylene-induced expression of the PRB-1b gene. Plant Mol. Biol. 28, 145–153. doi: 10.1007/bf00042046

Shakeel, S. N., Gao, Z., Amir, M., Chen, Y. F., Rai, M. I., Haq, N. U., et al. (2015). Ethylene regulates levels of ethylene receptor/CTR1 signaling complexes in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 12415–12424. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.652503

Shinshi, H., Usami, S., and Ohme-Takagi, M. (1995). Identification of an ethylene-responsive region in the promoter of a tobacco class I chitinase gene. Plant Mol. Biol. 27, 923–932. doi: 10.1007/bf00037020

Solano, R., Stepanova, A., Chao, Q., and Ecker, J. R. (1998). Nuclear events in ethylene signaling: a transcriptional cascade mediated by ethylene-insensitive3 and ethylene-response-factor1. Genes Dev. 12, 3703–3714. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.23.3703

Song, C. P., Agarwal, M., Ohta, M., Guo, Y., Halfter, U., Wang, P., et al. (2005). Role of an Arabidopsis AP2/EREBP-type transcriptional repressor in abscisic acid and drought stress responses. Plant Cell 17, 2384–2396. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.033043

Song, C. P., and Galbraith, D. W. (2006). AtSAP18, an orthologue of human SAP18, is involved in the regulation of salt stress and mediates transcriptional repression in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol. Biol. 60, 241–257. doi: 10.1007/s11103-005-3880-3889

Steger, D. J., and Workman, J. L. (1996). Remodeling chromatin structures for transcription: what happens to the histones? Bioessays 18, 875–884. doi: 10.1002/bies.950181106

Thiel, G., Lietz, M., and Hohl, M. (2004). How mammalian transcriptional repressors work. Eur. J. Biochem. 271, 2855–2862. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04174.x

Tsang, J., Zhu, J., and van Oudenaarden, A. (2007). MicroRNA-mediated feedback and feedforward loops are recurrent network motifs in mammals. Mol. Cell. 26, 753–767. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.018

Weake, V. M., and Workman, J. L. (2012). SAGA function in tissue-specific gene expression. Trends Cell Biol. 22, 177–184. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.11.005

Wen, X., Zhang, C., Ji, Y., Zhao, Q., He, W., An, F., et al. (2012). Activation of ethylene signaling is mediated by nuclear translocation of the cleaved EIN2 carboxyl terminus. Cell Res. 22, 1613–1616. doi: 10.1038/cr.2012.145

Yoon, K. J., Ringeling, F. R., Vissers, C., Jacob, F., Pokrass, M., Jimenez-Cyrus, D., et al. (2017). Temporal control of mammalian cortical neurogenesis by m(6) a methylation. Cell 171, 877–889.e817. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.003

Yosef, N., and Regev, A. (2011). Impulse control: temporal dynamics in gene transcription. Cell 144, 886–896. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.015

Zhang, F., Qi, B., Wang, L., Zhao, B., Rode, S., Riggan, N. D., et al. (2016). EIN2-dependent regulation of acetylation of histone H3K14 and non-canonical histone H3K23 in ethylene signalling. Nat. Commun. 7:13018. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13018

Zhang, F., Wang, L., Ko, E. E., Shao, K., and Qiao, H. (2018). Histone deacetylases SRT1 and SRT2 interact with ENAP1 to mediate ethylene-induced transcriptional repression. Plant Cell 30, 153–166. doi: 10.1105/tpc.17.00671

Zhang, F., Wang, L., Qi, B., Zhao, B., Ko, E. E., Riggan, N. D., et al. (2017). EIN2 mediates direct regulation of histone acetylation in the ethylene response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 10274–10279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1707937114

Zhou, C., Zhang, L., Duan, J., Miki, B., and Wu, K. (2005). Histone deacetylase19 is involved in jasmonic acid and ethylene signaling of pathogen response in arabidopsis. Plant Cell 17, 1196–1204. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.028514

Zhu, Y. X. (2010). The epigenetic involvement in plant hormone signaling. Chin. Sci. Bull. 55, 2198–2203. doi: 10.1007/s11434-010-3193-2

Keywords: ethylene, transcription regulation, Arabidopsis, histone, hormone

Citation: Wang L and Qiao H (2019) New Insights in Transcriptional Regulation of the Ethylene Response in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 10:790. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.00790

Received: 25 March 2019; Accepted: 31 May 2019;

Published: 18 June 2019.

Edited by:

Caren Chang, University of Maryland, United StatesReviewed by:

Gyeong Mee Yoon, Purdue University, United StatesCopyright © 2019 Wang and Qiao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hong Qiao, aHFpYW9AYXVzdGluLnV0ZXhhcy5lZHU=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.